Abstract

Molecular hydrogen is the basis of hydrogen energy. It is formed and used in many fields of industry, physics, and chemistry. Molecular hydrogen is the main product formed during the gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane. When studying the mechanism of molecular hydrogen formation during the gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane, we found that the values of adiabatic electron affinity, one of the fundamental characteristics of atoms and molecules, had not yet been experimentally determined for hydrogen and cyclohexane molecules. Theoretical estimates of the adiabatic electron affinity of the hydrogen molecule made by other authors varied widely ([−0.3; −5.771] eV) and could not be compared with experimental values due to the absence of such data. Using DFT calculations at the PBE0/TZVPP level of theory, and a constructed correlation with experimental values of the adiabatic first ionization potential and electron affinity for a number of molecules, neutral radicals, and atoms, we estimated, for the first time, the experimental adiabatic electron affinities of hydrogen (−3.08 eV) and cyclohexane (−2.13 eV) molecules in the gas phase. When an electron is attached to a cyclohexane molecule, a cyclohexane radical anion is formed, a new, highly reactive species that has not been studied before. A new perspective on molecular hydrogen formation during the gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane was introduced and discussed.

1. Introduction

The importance of hydrogen in the structure of the universe, our solar system, and, in particular, the Earth, all living creatures on it, and the organization of organic and inorganic matter cannot be overestimated [1,2,3,4]. Hydrogen is the most common element in the universe, accounting for about 90% of all atoms. It is the main component of stars and interstellar gas. The role of hydrogen on Earth is determined by its abundance: hydrogen atoms make up about 17% of all atoms (second only to oxygen). Therefore, hydrogen plays a crucial role in the chemical processes occurring on Earth. It is a component of almost all organic substances and is present in all living cells, where it accounts for nearly 63% of the total number of atoms. Hydrogen also participates in geochemical processes: it is found in volcanic gases, flows along faults in rifting zones, and is released in some coal deposits.

Most hydrogen is used to produce ammonia, methanol, and hydrogen chloride. In the oil refining industry, hydrogen is used in hydroprocessing to remove sulfur from fuels. High-purity hydrogen is used in semiconductor manufacturing for cleaning wafers, etching, alloying, and growing semiconductor films. In metallurgy, hydrogen is used to extract metals from their ores and as a shielding atmosphere during heat treatment.

In the food industry, hydrogen is used for the hydrogenation of fats and oils; to improve the appearance (glazing) of confectionery products; and as a protective environment for food packaging, which helps prevent oxidation and spoilage, thereby extending shelf life. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of hydrogen allow it to be used in medicine to reduce organ and tissue damage in diseases and conditions associated with oxidative stress.

Liquid hydrogen is used as a fuel in rocket and space technology and also serves as a refrigerant, while gaseous hydrogen acts as a carrier gas in gas chromatography.

The above list shows that, today, humanity primarily focuses on the numerous practical applications of hydrogen.

In many natural reactions and practical applications of hydrogen, single electron transfer (SET) processes occur. Two characteristics of the hydrogen molecule are fundamental to describing the energy physics of such processes: ionization potential (IP) and electron affinity (EA).

The first characteristic has been reliably established through various experimental and theoretical methods, while the second has not yet been experimentally determined, and the available theoretical data are inconsistent.

In this paper, this gap is addressed through a theoretical study aimed at determining the EA of a cyclohexane molecule.

Molecular hydrogen is the main end product of the gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane [5,6,7,8,9]. The EA values of hydrogen and cyclohexane molecules were theoretically determined in order to clarify the energy physics and mechanism of the early stages of gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane, which belong to the SET class of processes.

In this paper, we used data on gamma-60Co radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane [5,6,7,8,9]. Gamma rays from 60Co were represented by equal amounts of rays with energies of 1.1732 and 1.3325 MeV, with an average ray energy of Eav ≈ 1.25 MeV [10].

Upon gamma irradiation of liquid cyclohexane (1), molecular hydrogen (H2) (2), cyclohexene (c-C6H10) (2′), and dicyclohexyl ((c-C6H11)2) (2″) are formed as the main final products (FP) (reactions (1)–(9)) [5,6,7,8,9].

c-C6H12 + γ-rays → k{c-C6H12•+ + e−(E ≈ 20–100 eV)} + l{c-C6H12*(S and T)}

e−(E ≈ 20–100 eV) + m(c-C6H12) → m(c-C6H12•+) + (m + 1)e−(E < IP ≈ 10 eV)

e−(E < IP ≈ 10 eV) → e−(E(kT) ≈ 0.025 eV)

c-C6H12•+ + e−(E(kT) ≈ 0.025 eV) → c-C6H12*(S and T)

c-C6H12*(S) → H2 + c-C6H10

c-C6H12*(T) → H• + c-C6H11•

H• + c-C6H12 → H2 + c-C6H11•

2 c-C6H11• → c-C6H10 + c-C6H12

2 c-C6H11• → (c-C6H11)2

Reactions (1)–(9) are a simplified general scheme of gamma radiolysis 1, which shows how gamma ray energy is absorbed (reaction (1)), distributed (reactions (2) and (3)), and transformed into final products 2 (reactions (4)–(7)), 2′, and 2″ (reactions (6)–(9)) over characteristic times t ≈ 10−15–10−14 s (the physical stage), t ≈ 10−12 s (the physical and chemical stage), and t ≈ 10−10–10−6 s (the chemical stage), respectively.

The absorption of gamma ray energy occurs in portions, which form a set of cyclohexane radical cations (RCs) (c-C6H12•+) and high-energy free electrons (FEs) (e−(E ≈ 20–100 eV)). It is believed that after the energy is spent on the ionization of cyclohexane molecules (reaction (2)) and the electrons reach thermal energy (e−(E(kT) ≈ 0.025 eV)) (reaction (3)), charge recombination occurs (reaction (4)), which forms the main number of or all (then l = 0 in Equation (1)) electron-excited molecules (EEMs) (c-C6H12* (S and T are singlet and triplet EEM, respectively))—precursors of molecular hydrogen (reactions (5)–(7)) [5,6,7,8,9].

The vertical and adiabatic IPs (VIP and AIP) of cyclohexane are 10.3 ± 0.2 eV [11] and 9.88 ± 0.02 eV [11,12], respectively. The same values (10.3 and 9.88 eV) were reported in [13,14], and a more accurate value (79,720 ± 10 cm−1 (9.8840 ± 0.0012 eV)) is reported in [15].

Therefore, in reactions (2) and (3), using the condition E < IP ≈ 10 eV, emphasis is placed on the fact that when the kinetic energy of an FE decreases to less than ≈ 10 eV, ionization of cyclohexane molecules becomes impossible, and other mechanisms of energy absorption must be considered.

More than 85 years ago, a theory was proposed in which, after the formation of an ion pair, the kinetic energy of an FE is continuously reduced to thermal energy (E(kT) ≈ 0.025 eV) due to Coulomb interaction with a complementary cation (radical cation) (reaction (3)) [16]. For illustrative purposes, this theoretical model is still used today [8,17].

According to modern data, instead of continuous energy absorption (reaction (3)), two new channels of partial FE energy absorption should be considered.

First, there is reaction (3′), in which electronically excited molecules c-C6H12*(S and T) are formed. In liquid cyclohexane, electronically excited molecules in the ground electronic states are formed upon the absorption of energy E ≈ 7 eV, since it is known that the wavelength of the absorption edge λ (absorption edge) = 177.5 nm (energy 6.99 eV) [18]. This value of λ (absorption edge) increases to 180 nm (energy 6.89 eV) [19] with an increase in the amount of impurities [20].

Second, this is reaction (3″), in which cyclohexane radical anions (RAs) (c-C6H12•−) are formed, since it is known that cyclohexane molecules, like many other hydrocarbon molecules, have a negative EA [5,6,7,8].

A negative EA means that, in order for an FE to attach to a cyclohexane molecule, energy must be expended (i.e., has a positive value), numerically equal to the EA of the cyclohexane molecule (which has a negative value), taken with the opposite sign (see Section 2 and the graphical abstract). This energy can be provided by an FE with a kinetic energy of E ≈ 10 − 7 = 3 eV (reaction (3″)).

If reactions (3′) and (3″) occur, they replace reaction (3), which ceases to be the main reaction in the general scheme of cyclohexane gamma radiolysis.

This means that in gamma-irradiated cyclohexane, charge recombination (charge neutralization) should occur not according to reaction (4), but according to reaction (4′), in which RCs and RAs of cyclohexane participate.

e−(E < IP ≈ 10 eV) + c-C6H12 → c-C6H12*(S and T)(E ≈ 7 eV) + e−(E ≈ 3 eV)

e−(E ≈ 3 eV) + c-C6H12 → c-C6H12•− + E ≈ 3 eV − (-EA)

c-C6H12•+ + c-C6H12•− → c-C6H12*(S and T) + c-C6H12

For reaction (3″) to occur, the following condition must be met: E = 3 eV − (-EA) ≥ 0, i.e., EA(1) ≥ −3 eV. Only in this case will the kinetic energy of the electron E = 3 eV be sufficient for the FE to attach itself to the cyclohexane molecule.

If we were to rely on the single experimental value EA(1) = −4.11 eV [21], since −4.11 eV < −3 eV, we would conclude that reaction (3″) cannot occur.

For this reason, it was very important to estimate the experimental EA of the cyclohexane molecule in the gas phase as accurately and reliably as possible and to compare it with the experimental value of −4.11 eV [21]. Theoretically and experimentally, this value (−4.11 eV [21]) has not been reverified.

To this end, we performed DFT calculations for a number of chemical structures, correlated them with experimental data (see Section 2), obtained a reliable estimate of the experimental value EA(1) = −2.13 eV > −3 eV, and showed that the value −4.11 eV [21] is an outlier in the established correlation (see Section 3).

Thus, the findings of this paper support the conclusion that reaction (3″) can and should occur during the gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane.

2. Materials and Methods

Orca, an ab initio, DFT, and the semiempirical SCF-MO package, version 3.0.1 was used for all DFT calculations at the PBE0/TZVPP level of theory [22,23]. The TD-DFT method was used for calculations of the first single state of excited molecules [18,19]. The libint2 library for the computation of 2-el integrals [24], the basis Ahlrichs-TZV [25], and the Ahlrichs (2df, 2pd) polarization functions from the TurboMole basis set library [26] were utilized for all our calculations.

Since the IP and EA of molecules, radicals, and atoms represent the energetic cost of transferring one electron from or to the initial structure, respectively, the IP and EA values were calculated based on the energy difference (ΔE) between the formation energies of the initial and final structures, taking into account the sign change of ΔE depending on the direction of electron transfer.

The RHF method was used to calculate structures with closed electron shells (even-electron systems: molecules and ions), while the UHF method was applied to structures with open electron shells (odd-electron systems: radical ions and radicals).

To calculate the adiabatic IP (AIP) and adiabatic EA (AEA) values, full geometry optimization was performed for both the initial and final structures. For these structures, vibrational frequencies were calculated to confirm that the global minimum on the potential energy surface had been found.

To determine the vertical IP (VIP) and vertical EA (VEA) values, the formation energies of the final structures were calculated at the fixed geometries of the optimized initial structures (single-point calculations).

For a theoretical evaluation of the experimental AEA values of hydrogen and cyclohexane molecules, independent of the chosen computational method, a correlation was constructed between the calculated and experimental AIP and AEA values of specially selected molecules, radicals, and atoms.

Since the goal was to calculate the lowest possible values of EA(1) and EA(2), the correlation was based on reference and calculated AIP and AEA values, rather than the typically slightly higher VIP and VEA values.

The ChemCraft 1.7 program was used to create input files and visualize and design the calculation results [27]. All the calculations were carried out on personal computers: I (Intel(R) Core(TM) i7 CPU X 980 Processor, 6 cores to run 12 threads, 3.33 GHz, 24 GB RAM (16 GB available), x64 processor) and II (AMD Ryzen Threadripper 2990WX Processor, 32-cores to run 64 threads, 3.00 GHz, 128 GB RAM, x64 processor).

The calculation results are given in the text of the article and in the “Supplementary Materials” file.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Estimation by DFT of Experimental Values of the Adiabatic Electron Affinity of Hydrogen and Cyclohexane Molecules

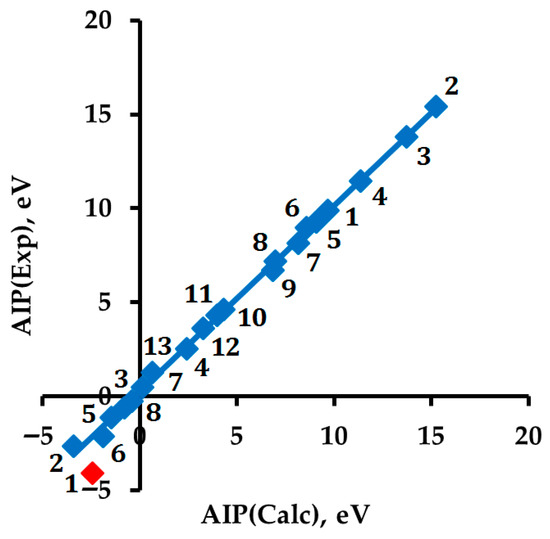

The hydrogen molecule sets the range of experimental characteristics under consideration: AIP(H2) = 15.43 eV and AEA(H2) = −2.66 eV represent the highest and lowest values, respectively (Figure 1, Table 1 and Table 2 [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]). As an experimental value in our work, we used the value AEA(H2) = −2.66 eV, determined by us from the data presented in Figure 1 of the theoretical study [38]. This choice requires additional explanation.

Figure 1.

Correlation between DFT-calculated and experimental values of AIP(Mol or Rad) and AIP(RA or An) = AEA(Mol or Rad): AIP(Exp) = 0.9874·AIP(DFT) + 0.2702, R2 = 0.9984. Different points with the same number refer to different physical characteristics (AIP and AEA) of one substance (see Table 1 and Table 2). The red-marked point (−2.43; −4.11), which refers to RA 1, is an outlier from the correlation.

Table 1.

Experimental and DFT-calculated adiabatic ionization potential (AIP, eV) and DFT calculated energies (E, Eh) of molecules (Mol) or radicals and radical cations (RC) or cations *.

Table 2.

Experimental and DFT calculated adiabatic electron affinities (AEA, eV) and DFT-calculated energies (E, Eh) of molecules (Mol) or radicals and radical anions (RA) or anions *.

To date, the experimental value of AEA(H2) (and VEA(H2) too) has not been determined. Such data are absent in reviews [39,40]. Many studies have noted that the direct experimental determination of AEA(H2) is complicated by the population of excited states of both the H2 molecule and the negative ion H2−• [51,52] in combination with the very short lifetime of H2−• [38,53,54].

Given the importance of estimating the experimental value of AEA(H2), we analyzed the available theoretical data. The theoretical values of AEA(H2), either calculated and reported by the authors or estimated by us from their published potential curves of the ground states of the H2 molecule and the RA H2−•, have a large scatter.

The highest value (−0.3 eV) was reported in [55]. The lowest value (−5.771 eV) was reported in [56]. Other studies reported intermediate values (eV): −0.78, −1.04, −1.82 [57], −1.9 [58], −2.0 [59,60], −2.5 [55], −2.66 [38], −2.79, −3.32, −3.53 [39], −3.26 [61], −3.6 [62]. As a fairly reliable theoretical estimate of the experimental value, we used AEA(H2) = −2.66 eV [38]. Since this value is close to the middle of the range of the above-listed values, this work was published relatively recently, and Figure 1 from that study, which we used for our estimation, has been reproduced in more modern theoretical publications [63,64].

The experimental value of AEA(H2) = −3.08 eV (Table 2) determined by us using the constructed correlation (Figure 1) is closest to the theoretical value of AEA(H2) = −3.26 eV [61] and 0.42 eV less than the theoretical value of −2.66 eV [38], which we initially selected as the theoretical reference for building the correlation.

The values of VEA(H2) calculated by the DFT method are −3.83 eV (DFT) and −3.51 eV (DFT’), respectively, without and taking into account the correlation with experimental data (E(H2•−) = −1.02788541467 Eh (energy of a single point H2•− on the geometry of the H2 molecule), DFT’ = A·DFT+B, A = 0.9874 and B = 0.2702).

The following characteristics were calculated for cyclohexane by the DFT method: VEA(c-C6H12) = −2.11 eV (E(c-C6H12•−) = −235.579469844684 Eh) and AEA(c-C6H12) = −2.43 eV (Table 2). Using the constructed correlation (DFT’ = A·DFT + B, A = 0.9874 and B = 0.2702), we obtain theoretical estimates of experimental values, which are, respectively, equal to VEA(c-C6H12) = −1.81 eV and AEA(c-C6H12) = −2.13 eV (Table 2).

Our correlation (Figure 1) shows that the experimental value of AEA(c-C6H12) = −4.11 eV [21] is an outlier (marked in red) and has about two times less value than our estimate of the experimental value of AEA(c-C6H12) = −2.13 eV.

It is this most reliable and accurate value of AEA(c-C6H12) = −2.13 eV > −3 eV that indicates the possibility of implementing a sequence of reactions (3′), (3″) and (4′) related to the initial stages of gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane.

3.2. The Boundary Orbitals and Chemical Stability of the Cyclohexane Molecule, RA and RC

The composition and energies of the frontier orbitals of the cyclohexane molecule determine the composition and energies of the frontier orbitals, as well as the reactivity, of its radical ions, RC and RA. Due to the presence of a third-order symmetry axis in the cyclohexane molecule (overall D3d symmetry), the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) exhibits twofold degeneracy [65]. According to Koopmans’ theorem, for the cyclohexane molecule, the experimental value of VIP = 10.3 ± 0.2 eV [11], taken with a negative sign, determines the HOMO energy, that is, E(HOMO) = -VIP.

The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the cyclohexane molecule is the Rydberg (3s-C) molecular orbital [66,67,68,69,70]. The LUMO energy determines the VEA value of the cyclohexane molecule (our estimated value is −1.81 eV). Thus, the experimental distance ∆E = |E(HOMO) − E(LUMO)| = 8.49 eV determined by VIP = 10.3 eV and VEA = −1.81 eV for the gas phase is 1 eV lower than the value of 9.5 eV calculated using the DFT method for the cyclohexane molecule.

The experimental distance ∆E = |E(HOMO) – E(LUMO)| = 7.75 eV determined by AIP = 9.88 eV and AEA = −2.13 eV for the gas phase is only 0.76 eV higher than the value of 6.99 eV [18] determined for liquid cyclohexane. If spectral line broadening is taken into account, then in the gas phase, the experimental distance ∆E = |E(HOMO) – E(LUMO)| will decrease further, bringing it closer to the value determined for liquid cyclohexane.

The structures of the cyclohexane molecule, RC and RA, calculated by the DFT method, correspond to the energy minima, since all vibration frequencies have real positive values (provided in the “Supplementary Materials” file).

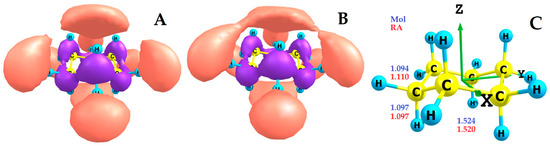

The cyclohexane RA is formed by attaching one unpaired electron to a cyclohexane molecule, which occupies its LUMO. Since this Rydberg (3s-C) type MO (LUMO of molecule, Figure 2A) is non-degenerate and has high symmetry, when it is populated with one unpaired electron (the single occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) of RA, Figure 2B), the symmetry (D3d) of the original molecule and the sequence of energy arrangement of its occupied and vacant MO are preserved, and all geometric changes are distributed evenly over all one type of C-C bonds and two types of C-H bonds (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) LUMO of the c-C6H12 molecule; (B) SOMO of c-C6H12•− RA; (C) Axes and DFT-calculated bond lengths of the cyclohexane molecule and RA.

When the cyclohexane RA is formed, the lengths (1.097 Å) of axial C-H bonds remain unchanged, the lengths of C-C bonds are slightly reduced (by 0.004 Å), and the lengths of equatorial C-H bonds increase significantly (by 0.016 Å) (Figure 2C). This indicates that, in accordance with the type of MO, during the transition from the LUMO of the molecule to the SOMO of the RA of cyclohexane, it is the equatorial C-H bonds that are activated. These bonds are weakened and become more susceptible to further chemical transformations associated with the rupture of C-H bonds.

It is convenient to compare the chemical stability of the cyclohexane RA and its reactivity with respect to the rupture of the activated C-H bond (reactions (10) and (11)) with the same characteristics of the homolytic rupture of the C-H bond of the original cyclohexane molecule (reaction (12)) and the hydrogen molecule (reaction (13)).

c-C6H12•− → c-C6H11• + H−

c-C6H12•− → c-C6H11− + H•

c-C6H12 → c-C6H11• + H•

H2 → H• + H•

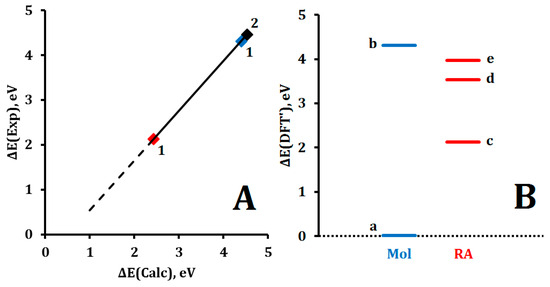

According to experimental data, the energies of homolytic rupture of the C-H bond of cyclohexane and the H-H bond of the hydrogen molecule are 4.31 and 4.46 eV, respectively [69,70] (Figure 3, Table 3). According to our experimental data, the formation of a cyclohexane RA from a cyclohexane molecule requires an energy input of 2.13 eV (reaction (3″), Figure 3, Table 2 and Table 3).

Figure 3.

(A) Correlation between DFT-calculated and experimental values of ∆E parameters of 1 (Blue), 2 (Black) molecules and RA 1 (Red): ∆E(Exp) = 1.167·∆E(Calc) − 0.8258, R2 = 1; (B) DFT-calculated with correction values of ∆E parameters: (a) ∆E(DFT’) = 0 corresponds to E(c-C6H12) = −235.671105366798 Eh, (b) dissociation energy D(C-H) of c-C6H12, (c) relative energy ΔE(c-C6H12•−) of RA 1 formation, (d) and (e) dissociation energy D(C-H) of c-C6H12•− plus ΔE(c-C6H12•−) for reactions (10) and (11), correspondently (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Experimental and DFT-calculated ∆E parameters without and with corrections, eV *.

As described earlier, this energy corresponds to the negative value AEA(1) = −2.13 eV which makes it possible to plot both theoretically calculated and experimental values of AEA and AIP on a single correlation curve (Figure 1 and Figure 3A). At the same time, to compare the dissociation energies of the molecule and the RA of cyclohexane taking into account AEA(1), it is necessary to use the opposite sign value ΔE(c-C6H12•−) = −AEA(1). This reflects a shift from an energy accounting scheme based on the direction of SET to a unified scheme used the formation energy of molecule 1 as a single initial structure (Figure 3B). This adjustment is also necessary because, by definition, positive values of EA and IP correspond to opposite energy effects: energy release and energy absorption, respectively.

The dissociation energy values D(C-H) of c-C6H12•− for reactions (10) and (11) have not been determined experimentally. Using DFT calculations and a correlation with experimental data, we made theoretical estimates (DFT′) of these values (Figure 3, Table 3).

The smallest value (1.68 eV) was obtained for D(C-H) c-C6H12•− in reaction (10). This value is 2.57 times lower than D(C-H) c-C6H12 in reaction (12). If the values AEA = 2.13 eV and D(C-H) = 1.68 eV are used for RA 1, then their total energy E = AEA + D(C-H) = 3.81 eV sets the threshold energy range for FEs: when the kinetic energy of an FE falls within this range, RA 1 can form and remain chemically stable. Specifically, for the formation and stability of RA 1, the FE energy must satisfy the condition: 2.13 eV < E(e−) < 3.81 eV (estimated gas-phase values were used).

This inequality also means that, in the case of reaction (3′), the remaining portion of energy E(e−) = 10 − 7 = 3 eV is sufficient to form RA 1, but not enough to implement reaction (10). In this sense, during the implementation of reaction (3′), we can speak of the chemical stability of RA 1, since it does not possess sufficient excess energy to break even one of its C-H bonds.

If we were interested in the chemical stability of RA 1 in a condensed medium, then instead of considering the monomolecular reaction (10), which pertains to the gas phase, we would calculate the energy effect of a similar but bimolecular reaction (10′).

c-C6H12•− + c-C6H12 → c-C6H11• + c-C6H13−

However, this is not necessary, since the main reaction RA 1 should be the neutralization of charges (reaction (4′)), rather than a 10′ type reaction. This is because the rates of SET reactions in which a lighter particle, a single electron, is transferred, are high and do not require physical contact between the reacting particles. Since reaction (4′) is also the main reaction for consumption of RC 1, in a condensed medium, the lifetimes of RC 1 and RA 1 should be equal or very close.

For energetic reasons, it can be assumed that in this ion pair, the negative ion RA 1 is chemically more stable and has a longer lifetime than the positive ion RC 1. This is because the formation of RC 1 requires five times more energy (E ≈ 10 eV) than the formation of RA 1 (E ≈ 2 eV), meaning the chemical bonds in RC 1 are more strongly activated than in RA 1. Thus, in our opinion, the previously unexplored primary particles of RA 1 exhibit sufficient chemical stability to be included in the general scheme of the gamma radiolysis of cyclohexane.

It is worth recalling that, due to the presence of a third-order symmetry axis in the cyclohexane molecule (general symmetry D3d), the HOMO of the molecule is twofold degenerate. Using the ESR method in combination with the results of theoretical calculations, it was established that with single ionization, the double degeneracy of the HOMO of the cyclohexane molecule was removed and RC 1 was formed in the ground state 2Ag (the D3d symmetry of the original molecule was reduced to C2h) [71].

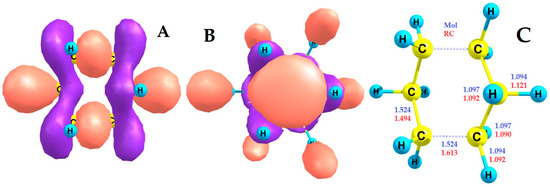

The type of SOMO and LUMO of RC 1 calculated by us using the DFT method in the 2Ag ground state and the geometric changes occurring during single ionization are shown in Figure 4. The SOMO of RC 1 is mainly concentrated on two C-C bonds, which are greatly elongated (by 0.089 Å), and on two codirectional equatorial C-H bonds, which are also greatly elongated (by 0.027Å), become less strong and more reactive (Figure 4A,C). The other four C–C bonds are shortened (by 0.030 Å) and strengthened (Figure 4A,C).

Figure 4.

(A) SOMO of the c-C6H12•+ RC; (B) LUMO of the c-C6H12•+ RC; (C) DFT-calculated bond lengths of the cyclohexane molecule and RC.

With such strong geometric changes (Figure 4C), the same type of LUMO remains in RC 1 (Figure 4B) as in the parent molecule (Figure 2A). Figure 4 shows the characteristics of a cyclohexane RC and molecule when viewed along the “-z” axis (see Figure 2C).

A strong elongation of the C-H bond in RC 1 leads to its significant weakening, which in liquid cyclohexane promotes the ion-molecular reaction (14). One of the products of this reaction is the protonated form of the molecule (c-C6H13+) [72].

c-C6H12•+ + c-C6H12 → c-C6H11• + c-C6H13+

However, it should be noted that reaction (14) is a very fast, assumed (but not experimentally confirmed) reaction. Further studies are needed to assess the contributions of reactions (14) and (10′) to the general mechanism of cyclohexane radiolysis. Depending on the specific research objectives and the accepted model simplifications, these reactions may or may not need to be considered.

In our opinion, the main reaction of cyclohexane radical ions (RC and RA) is the charge neutralization reaction (4′) (electron transfer), which forms EEM. Cyclohexane RC and RA can also participate in reactions (14) and (10′). But in these two reactions, heavier particles are transferred: H+ and H−, respectively. Therefore, reactions (14) and (10′) should be slower compared to reaction (4′). The concentration factor acts in the opposite direction: the concentration of molecules 1 is much higher than the concentrations of RC 1 and RA 1. The definition and comparison of the rates of reactions (4′), (10′) and (14), taking into account the contributions of various factors, is the subject of a separate study.

3.3. The Initial Stage of Gamma Radiolysis of Liquid Cyclohexane, Taking into Account the Formation of RC, EEM, and RA

In the introduction, reactions (1)–(9) were presented, which described the formation of three main end products (2, 2′, 2″) of gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane, all associated with the breaking of C-H bonds. In the introduction, we did not mention the formation of minor products of gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane associated with C-C bond breaks [5,6,7,8]. We also did not describe the photophysical processes responsible for the fluorescence of irradiated systems (cyclohexane without and with additives of special substances) [72,73,74]. Against the background of chemical transformations, such photophysical processes have a very low intensity and manifest themselves at the final stage of radiation-stimulated processes. The quantum yield of fluorescence is characterized by a wavelength λ (maximum) = 201 nm (energy 6.17 eV) [75] and a quantum yield of φ ≈ 10−3–10−2 [74,75].

At the same time, it is known that during gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane, a negligible number of thermalized FEs (0.11 e−/100 eV) is detected [76]. Consequently, thermalized FEs are minor products of gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane, though they are traditionally included in the main reaction scheme (reactions (1)–(9)), particularly in reaction (4).

This approach is based on the long-standing assumption in radiation chemistry that, due to its negative electron affinity (EA), the cyclohexane molecule cannot attach an FE and therefore cannot form RA 1. As a result, the thermalized FE has traditionally been considered the only negative charge participating in the charge neutralization reaction (reaction (4)).

In our study, we demonstrated for the first time that this widely accepted view is incorrect. RA 1 is a chemically active species that can be formed during gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane and has sufficient chemical stability to be included in the general mechanism.

Moreover, considering that the initial number of thermalized FEs is extremely low and that the concentration of cyclohexane molecules is many orders of magnitude greater than the total concentration of all primary, secondary, and final radiolysis products, the formation of RA 1 via reaction (2′) should occur much more rapidly than the neutralization reaction (4).

Therefore, when describing the mechanism of gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane, reaction (3′), rather than reaction (4), should be considered the primary pathway. Furthermore, the energy E ≈ 3 eV used in reactions (3′) and (3″), more precisely the -EA(1), should be defined with greater accuracy. It is worth noting that E ≈ 3 eV is also the arithmetic mean of the previously established range 2.13 eV < E(e−) < 3.81 eV (estimated for the gas-phase), which reflects the energy window required for both the formation and chemical stability of RA 1. Thus, 3 eV represents the center of this energy range.

If we consider the sequence of gamma ray energy absorption reactions—firstly, reaction (1), in which k = 1 and l = 0 (only ion pairs are formed), and, secondary, reactions (2), (3′), and (3″) (the kinetic energy of FE is consumed)—then the initial stage of the gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane can be written as reaction (1′).

c-C6H12 + γ-rays → c-C6H12•+ + c-C6H12*(S and T) + c-C6H12•−

In reaction (1′), charge separation occurs, resulting in the formation of pairs of cyclohexane ions (RC and RA). This means that upon gamma-ray energy absorption, one electron is transferred from one cyclohexane molecule to another.

During gamma radiolysis, the two cyclohexane molecules involved may be adjacent or separated by some distance. In some RC–RA ion pairs, spin correlation may be preserved; in others, it may not. Cyclohexane EEM is formed from a third cyclohexane molecule.

In reaction (1′), the active particles RC:EEM:RA of cyclohexane are formed in a ratio of 1:1:1. To realize the reaction (1′) in liquid cyclohexane, energy expenditure is required: E(1′, liquid) = IP(liquid) + ∆E(liquid) + (-EA(liquid)), where IP(liquid) = 8.43 ± 0.05 eV [77,78,79] (IP(solid) = 8.2 ± 0.1 eV [80]), ∆E(liquid) = |E(HOMO) − E(LUMO)| = 6.99 eV [18].

The experimental value of EA(liquid) for cyclohexane is unknown, as no direct measurements have been performed. However, it can be estimated in two ways.

Before we proceed to their practical discussion, it should be clarified that the experimental papers [77,78,79] reported two close values of IP(liquid 1) without explanation: 8.43 ± 0.05 eV and 8.75 ± 0.1 eV. Earlier, for illustrative purposes, we used the first value, since it is smaller. Here, we will make numerical estimates; therefore, we will use both experimental IP values (liquid 1) for comparison [77,78,79].

The first method is based entirely on experimental data related to reaction (1′).

When 100 eV of gamma ray energy is absorbed by liquid cyclohexane, Σ(H2) = 5.6 hydrogen molecules are formed and the total number of Σ(FP) = 6.4 molecules of all final products (FP) associated with the breaking of C-H bonds (Σ(C-H) = Σ(H2) = 5.6 molecules) and C-C bonds (Σ(C-C) = 0.8 molecules) [1,2,3,4,5].

Thus, the experimental value of E(1′, liquid 1) = 100/5.6 = 17.86 eV. Then the experimental (adiabatic) value EA(liquid 1) = − (E(1′, liquid 1) − ((IP(liquid 1) + ∆E(liquid 1))) = − (17.86 − (8.43 + 6.99)) = −2.44 eV, if IP(liquid 1) = 8.43 eV, and EA(liquid 1) = − (17.86 − (8.75 + 6.99)) = −2.12 eV, if IP(liquid 1) = 8.75 eV.

According to the second method, we assume that EA(liquid 1) = AEA(gas 1) = −2.13 eV (see Table 2).

In the case IP(liquid 1) = 8.43 eV, E(1′, liquid 1) = 8.43 + 6.99 + (−(−2.13)) = 17.58 eV. Therefore, per 100 eV of absorbed gamma ray energy, Σ(PAP) = 100/17.58 = 5.69 PAP is formed, where Σ(PAP) is the total number of primary active particles (PAP) (Σ(PAP) = RC + EEM + RA), which lead to the formation of hydrogen molecules.

In the case IP(liquid 1) = 8.75 eV, E(1′, liquid 1) = 8.75 + 6.99 + (–(−2.13)) = 17.87 eV. Therefore, per 100 eV of absorbed gamma ray energy, Σ(PAP) = 100/17.87 = 5.60 PAP is formed, which coincides with the experimental value Σ(H2) = 5.6 molecules/100 eV.

Thus, both values of IP(liquid 1) yield similar results, but in the case of IP(liquid 1) = 8.75 eV, both methods of estimating EA(liquid 1) give virtually identical results. Therefore, it can be assumed that during gamma radiolysis of liquid cyclohexane, an ionization channel corresponding to molecules with IP(liquid 1) = 8.75 eV is realized.

In this case, all the experimental data related to the 1′ (liquid) reaction agree well with each other: Σ(H2) = 5.6 molecules/100 eV, the ratio RC:EEM:RA = 1:1:1, IP(liquid 1) = 8.75 eV, ∆E(liquid 1) = 6.99 eV, EA(liquid 1) = −2.13 eV.

The result also implies that during the transition from the gas to the liquid phase, IP(1) decreases from IP(gas 1) ≈ 10 eV to IP(liquid 1) ≈ 9 eV, while the value of EA(1) remains unchanged: EA(gas 1) = AEA(liquid 1) ≈ −2 eV. This finding is new and requires further interpretation, clarification, and investigation into the reasons behind it.

During the transition from the gas to the liquid and solid phases, the IP of cyclohexane decreases: 9.88 eV [12], 8.43–8.75 eV [77,78,79], and 8.2 eV [80], respectively. This effect is usually associated with the structuring of liquids and solids within the framework of band theory and ideas about the polarization of molecules in condensed media [77,78,79,80]. Within the framework of this approach, attention could be drawn to the fact that during the transition from gaseous to condensed media, the FE does not go to the zero-vacuum level E(e−) = 0 eV ≈ 0.025 eV (E(kT)), but remains in an ionized condensed medium (E(e−) ≈ 2 eV (-AEA of gas and liquid 1, with work)). This implies the accession of FE to LUMO 1. This important point has not been previously addressed in the literature.

The main FP of gamma radiolysis of cyclohexane were determined for the gas, liquid, and solid phases [5,6,7,8,9]. Even at a gas density of 0.0047 g/cm3, the absorption of 100 eV of gamma ray energy leads to the formation of 5.3 H2 molecules [6,81]. This value, defined for a gas (5.3 H2 molecules), is close to the value defined for a liquid (5.6 H2 molecules [5,6,82]). In other experiments, the formation of identical amounts of molecular hydrogen was measured for the gas and solid phases: 4.7 molecules [6,83] and 4.73 molecules, respectively, [6,84]. These facts indicate that the total reaction (1′) of the formation of PAP has a more universal meaning and applies to all three states of aggregation of cyclohexane: gas, liquid and solid.

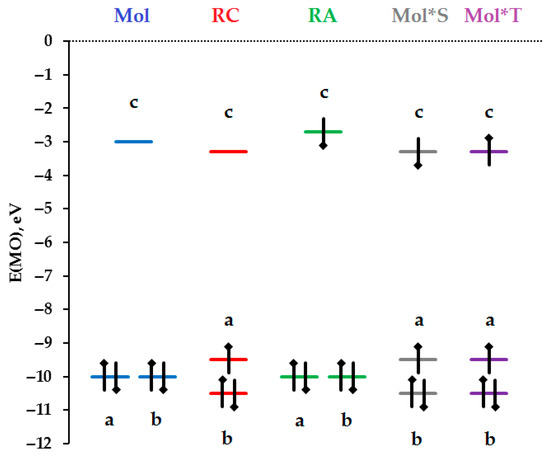

3.4. Relative Energy Location of the Boundary Orbitals of the Cyclohexane Molecule and Its Primary Active Particles of Gamma Radiolysis

Figure 5 shows the relative energy location of the boundary MOs of the cyclohexane molecule: the doubly degenerate HOMO (MOs a and b) and the Rydberg (3s-C) type LUMO (MO c), as well as all the PAP discussed in the article: RC, RA and EEM in electronic states S and T. The distances between MOs were chosen not from the results of our DFT calculations, but based on experimental data, known general trends, and the convenience of conveying the main ideas in graphical form.

Figure 5.

The energy arrangement of the boundary molecular orbitals a, b (HOMO and SOMO) and c (LUMO and SOMO) of the ground electronic states of the molecule (Mol), radical cation (RC) and radical anion (RA) of cyclohexane, as well as the first singlet (Mol*S) and triplet (Mol*T) electronically excited states of the same molecule.

The HOMO energy of a cyclohexane molecule is equal to the first vertical potential, taken with the opposite sign, E(HOMO) = −VIP. In Figure 5, the value E(HOMO) = −10 eV is used instead of the experimental value VIP = 10.3 ± 0.2 eV [11]. The distance between the HOMO and LUMO of the cyclohexane molecule is chosen to be 7 eV [18]—the minimum energy of light quanta at which a cyclohexane molecule begins to absorb ultraviolet light in the liquid phase. For the convenience of conveying the main ideas in graphical form, another simplification has been made in Figure 5, namely, MOs a and b of RC and EEM are separated by a distance of 1 eV, which is actually unknown.

When one electron is removed from the HOMO Mol 1, RC 1 is formed, in which, due to the removal of double degeneracy of MOs a and b and large structural changes, the distance between the boundary MOs—a (HOMO RC 1) and c (LUMO RC 1)—decreases due to reducing binding in MO a (MO energy increases) and reducing loosening in MO c (MO energy decreases).

In the case of RC 1, geometric changes (see Figure 4C) are specified by a change in the population of MO a from double (in the molecule) to single (in the RC). If we trace how the geometric changes that occurred during single ionization of the cyclohexane molecule affect the effects of binding and loosening in MO c, it becomes clear that binding in two C-C bonds decreases, and in four C-C bonds increases. In this case, the loosening will decrease in two activated C-H bonds, and in other C-H bonds, it will remain approximately the same as in the original molecule. Therefore, we assume that MO c in RC 1 will decrease in energy somewhat relative to its position in the initial molecule (see Figure 5).

In the case of RA 1, single electron occupancy of MO c produces the expected geometric changes: a slight shortening and strengthening of all C-C bonds and a significantly greater lengthening and weakening of all equatorial C-H bonds (see Figure 2C). The effect of increased loosening in C-H bonds is stronger than the effect of increasing binding in C-C bonds. Therefore, we assume that MO c in RA 1 increases in energy somewhat relative to its position in the original molecule (see Figure 5).

In this regard, it should be noted that, although MO c is a non-binding Rydberg (3s-C) type MO, it has one nodal surface, which is located between carbon atoms and hydrogen atoms (see Figure 2A (Mol), 4B (RC) and 2B (RA)). According to the type of MO c in it, the binding between all carbon atoms is compensated by loosening in all C-H bonds.

It is important that MO c occupied by one electron in RA 1 is located somewhat higher in energy than the free (vacant) MO c in RC 1. This is an additional favorable energy factor that promotes the occurrence of reaction (4′)—the transfer of one electron from RA 1 to RC 1 with the participation of the same type and symmetry of MO c.

Figure 5 shows a spin-correlated pair of RC 1 and RA 1, from which, according to reaction (4′), the cyclohexane EEM is formed in the singlet (S) state (Mol*S = c-C6H12*(S)) (see Figure 5 and reactions (1),(4),(5),(1′),(3′),(4′)). If the spin of electron, occupied MO c in RA 1, is changed to the opposite spin, then a pair of RC 1 and RA 1 will be obtained, which, by reaction (4′), will lead to the formation of EEM in the triplet (T) state (Mol*T = c-C6H12*(T)) (see Figure 5 and reactions (1),(4),(6),(1′),(3′),(4′)).

4. Conclusions

- Using DFT calculations and the constructed correlation with experimental data, it was found that the experimental values of the adiabatic electron affinity (AEA) of cyclohexane (1) and hydrogen (2) molecules in the gas phase are −2.13 eV (AEA(gas 1)) and −3.08 eV (AEA(gas 2)), respectively.

- Using independent experimental data related to the liquid phase, it was found that the experimental value of the adiabatic electron affinity of the cyclohexane molecule in the liquid phase is −2.12 eV (EA(liquid 1)).

- Thus, for the first time, it was found that EA(liquid 1) = AEA(gas 1) ≈ −2 eV.

- Upon gamma irradiation of liquid cyclohexane, all molecular hydrogen is formed at the final stage of the transformation of the energy of 60Co gamma rays (E ≈ 1.25 MeV) into the energy of three primary particles—a radical cation (E ≈ 9 eV (liquid)), an electronically excited molecule (E ≈ 7 eV (liquid)) and a radical anion (E = -AE(liquid) ≈ 2 eV)—at a ratio of 1:1:1, with total energy ΣE ≈ 18 eV (liquid).

- Using DFT calculations and the literature to date, it is shown that the cyclohexane radical anion has sufficient chemical stability to be included in the general scheme of gamma radiolysis of gaseous, liquid and solid cyclohexane.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hydrogen6040115/s1, Table S1: The Charge, Spin state, Energy and XYZ coordinates of all atoms of all structures optimized by the DFT method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Y.S.; methodology, I.Y.S.; software, I.Y.S.; validation, A.I.N. and I.Y.S.; formal analysis, A.I.N. and I.Y.S.; investigation (DFT calculations), I.Y.S.; resources, A.I.N. and I.Y.S.; data curation, A.I.N. and I.Y.S.; writing, original draft preparation, I.Y.S.; writing, review and editing, A.I.N. and I.Y.S.; visualization, I.Y.S.; supervision, A.I.N. and I.Y.S.; project administration, A.I.N. and I.Y.S.; funding acquisition, A.I.N. and I.Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to F. Neese and members of his team for creating the free package of quantum-chemical programs “Orca,—an ab initio, DFT, and the semiempirical SCF-MO package—version 3.0.1” and detailed instructions for its use [22,23], thanks to which this work and the previous one [85] became possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AIP | Adiabatic Ionization Potential |

| AEA | Adiabatic Electron Affinity |

| An | Anion (−) |

| Cat | Cation (+) |

| C-H | Carbon-Hydrogen bond |

| C-C | Carbon- Carbon bond |

| c-C6H10 | Cyclohexene molecule (2′) |

| c-C6H11• | Cyclohexyl radical |

| c-C6H12 | Cyclohexane molecule (1) |

| (c-C6H11)2 | Dicyclohexyl (2″) |

| D | Dissociation energy |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| E | Energy |

| EA | Electron Affinity |

| EEM | Electronically Excited Molecule (*) |

| FE | Free Electron (e−) |

| FP | Final Product |

| GGA | Generalized Gradient Approximation |

| H• | Hydrogen radical (atom) |

| H2 | Hydrogen Molecule (2) |

| HOMO | Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital |

| IP | Ionization Potential |

| LUMO | Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital |

| MO | Molecular Orbital |

| Mol | Molecule |

| NFR | Neutral Free Radical |

| PAP | Primary Active Particle |

| PBE0 | One-parameter hybrid version of PBE |

| PBE | Perdew-Burke-Erzerhoff GGA functional |

| PP | Three sets of first polarization functions on all atoms |

| RA | Radical Anion (•−) |

| Rad | Radical (•) |

| RC | Radical Cation (•+) |

| RHF | Restricted Hartree-Fock |

| S | Singlet |

| SCF-MO | Self-Consistent Field-Molecular Orbital |

| SET | Single Electron Transfer |

| SOMO | Single Occupied Molecular Orbital |

| T | Triplet |

| TZV | Ahlrichs Triple-Zeta Valence basis set |

| TZVPP | TZV + PP |

| UHF | Unrestricted Hartree-Fock |

| VEA | Vertical Electron Affinity |

| VIP | Vertical Ionization Potentials |

References

- Ishaq, H.; Dincer, I.; Crawford, C. A review on hydrogen production and utilization: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 26238–26264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, B.S.; Ker, P.J.; Mohamed, H.; Ong, H.C.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Nghiem, L.D.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Recent advancement and assessment of green hydrogen production technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189 Pt A, 113941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose, M.P.; Kannaiyan, S.; Huang, S.-J. Hydrogen carriers for hydrogen transport and storage (hydrogen Storage): A review. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 345, 131252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serik, A.; Kuspanov, Z.; Daulbayev, C. Cost-effective strategies and technologies for green hydrogen production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226 Pt A, 116242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.K.; Freeman, G.R. Radiolysis of Cyclohexane. V. Purified Liquid Cyclohexane and Solutions of Additives. J. Phys. Chem. 1964, 68, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földiak, G. (Ed.) Radiation Chemistry of Hydrocarbons; Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- LaVerne, J.A.; Pimblott, S.M.; Wojnarovits, L. Diffusion−kinetic modeling of the γ-radiolysis of liquid cycloalkanes. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnárovits, L. Radiation Chemistry. In Handbook of Nuclear Chemistry 3; Vértes, A., Nagy, S., Klencsár, Z., Lovas, R.G., Rösch, F., Eds.; Chemical Applications of Nuclear Reactions and Radiations; Springer Science + Business Media B.V: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Chapter 23; pp. 1263–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchapin, I.Y.; Makhnach, O.V.; Klochikhin, V.L.; Nekhaev, A.I. Radiolysis products of the cyclohexane–bicyclic diene binary system. Pet. Chem. 2017, 57, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikaev, A.K. Modern Radiation Chemistry: Main Regularities, Experimental Technique and Methods; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1985; p. 375. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ikuta, S.; Yoshihara, K.; Shiokawa, T.; Jinno, M.; Yokoyama, Y.; Ikeda, S. Photoelectron spectroscopy of cyclohexane, cyclopentane, and related compounds. Chem. Lett. 1973, 2, 1237–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K. Ionization potentials of some molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1957, 26, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, P.; Hashmall, J.A.; Heilbronner, E.; Hornung, V. Photoelektronspektroskopische Bestimmung der Wechselwirkung zwischen nicht-konjugierten Doppelbindungen [1]. Vorläufige Mitteilung. Helv. Chim. Acta 1969, 52, 1745–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, G.; Burger, F.; Heilbronner, E.; Maier, J.P. Valence ionization energies of hydrocarbons. Helv. Chim. Acta 1977, 60, 2213–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymonda, J.W. Rydberg states in cyclic alkanes. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 3912–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Initial Recombination of Ions. Phys. Rev. 1938, 54, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G. Charge carrier generation and recombination in cyclohexane solutions excited by VUV light. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 124, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostafin, A.E.; Lipsky, S. The fluorescence action spectra of some saturated hydrocarbon liquids for excitation energies above and below their ionization thresholds. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5408–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costner, E.A.; Long, B.K.; Navar, C.; Jockusch, S.; Lei, X.; Zimmerman, P.; Campion, A.; Turro, N.J.; Willson, C.G. Fundamental optical properties of linear and cyclic alkanes: VUV absorbance and index of refraction. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 9337–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.T.; Askew, D.; Lipsky, S. A note on the G value for the production of the lowest excited singlet state of cyclohexane. Radiat. Phys. Chem. (1977) 1982, 19, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.E.; Staley, S.W. Negative Ion States of Three- and Four-Membered Ring Hydrocarbons: Studied by Electron Transmission Spectroscopy. In Resonances; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; Volume 263, pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. ORCA–An Ab Initio, DFT and Semiempirical SCF-MO Package, version 3.0.1; Max-Plank-Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion: Ruhr, Germany, 2013. Available online: https://orcaforum.kofo.mpg.de/ (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Valeev, E. Libint: High-Performance Library for Computing Gaussian Integrals in Quantum Mechanics. Available online: http://libint.valeyev.net (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Schaefer, A.; Horn, H.; Ahlrichs, R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Turbomole Basis Set Library. Available online: http://ftp.chemie.uni-karlsruhe.de/pub/bases (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Chemcraft—Graphical Software for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Glab, W.L.; Hessler, J.P. Multiphoton excitation of high singlet np Rydberg states of molecular hydrogen: Spectroscopy and dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 1987, 35, 2102–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, E.; Gilligan, J.M.; Cornaggia, C.; Eyler, E.E. Measurement of high Rydberg states and the ionization potential of H2. Phys. Rev. A. 1989, 39, 2260(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Reutt, J.E.; Lee, Y.T.; Shirley, D.A. High resolution UV photoelectron spectroscopy of CO+2, COS+, and CS+2 using supersonic molecular beams. J. Electr. Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1988, 47, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yencha, A.J.; Hopkirk, A.; Hiraya, A.; Donovan, R.J.; Goode, J.G.; Maier, R.R.J.; King, G.C.; Kvaran, A. Threshold photoelectron spectroscopy of Cl2 and Br2 up to 35 eV. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 7231–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewter, L.A.; Sander, M.; Müller-Dethlefs, K.; Schlag, E.W. High resolution zero kinetic energy photoelectron spectroscopy of benzene and determination of the ionization potential. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 4737–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, G.I.; Selzle, H.L.; Schlag, E.W. Magnetic ZEKE experiments with mass analysis. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 215, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Katsumata, S.; Achiba, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Iwata, S. Ionization Energies, Ab Initio Assignments, and Valence Electronic Structure for 200 Molecules. In Handbook of HeI Photoelectron Spectra of Fundamental Organic Compounds; Japan Scientific Soc. Press: Tokyo, Japan; Halsted Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Houle, F.A.; Beauchamp, J.L. Detection and investigation of allyl and benzyl radicals by photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 3290–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, F.A.; Beauchamp, J.L. Thermal decomposition pathways of alkyl radicals by photoelectron spectroscopy. Application to cyclopentyl and cyclohexyl radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1981, 85, 3456–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishima, I.; Yoshikawa, K.; Yonezawa, T.; Matsumoto, H. Photoelectron spectral studies of organic free radicals. The nitroxide radical. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1972, 16, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cízek, M.; Horácek, J.; Domcke, W. Nuclear dynamics of the H2− collision complex beyond the local approximation: Associative detachment and dissociative attachment to rotationally and vibrationally excited molecules. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1998, 31, 2571–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, G.J. Resonances in electron impact on diatomic molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1973, 45, 423–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienstra-Kiracofe, J.C.; Tschumper, G.S.; Schaefer, H.F., III; Nandi, S.; Barney Ellison, G. Atomic and molecular electron affinities: Photoelectron experiments and theoretical computations. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 231–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A.; Echt, O.; Kreisle, D.; Mark, T.D.; Recknagel, E. Formation of long-lived CO2–, N2O– and their dimer anions, by electron attachment to van der Waals clusters. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 126, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, K.H.; Liesegang, G.W.; Sanders, R.A.; Herschbach, D.W. Electron attachment to molecular clusters by collisional charge transfer. J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 87, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanche, L.; Schulz, G.J. Electron transmission spectroscopy: Resonances in triatomic molecules and hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 1973, 58, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modelli, A.; Jones, D.; Distefano, G. ETS study of the negative ion states of t-butyl and trimethylsilyl derivatives of ethylene and benzene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1982, 86, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrow, P.D.; Michejda, J.A.; Jordan, K.D. Electron transmission study of the temporary negative ion states of selected benzenoid and conjugated aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenthold, P.G.; Polak, M.L.; Lineberger, W.C. Photoelectron spectroscopy of the allyl and 2-methylallyl anions. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 6920–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerboom, R.A.L.; Rademaker, G.J.; de Koning, L.J.; Nibbering, N.M.M. Stabilization of cycloalkyl carbanions in the gas phase. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1992, 6, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.J.; Wang, H.; Pradhan, K.; Koirala, P.; Kandalam, A.K.; Bowen, K.H.; Jena, P. Superhalogen properties of CumCln clusters: Theory and experiment. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 135, 244312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainham, R.; Fletcher, G.D.; Larson, D.J. One- and two-photon detachment of the negative chlorine ion. J. Phys. B 1987, 20, L777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, D.G.; Ho, J.; Lineberger, W.C. Photoelectron spectroscopy of mass–selected metal cluster anions. I. Cu−n, n = 1–10. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordon-Thaden, B.; Kreckel, H.; Golser, R.; Schwalm, D.; Berg, M.H.; Buhr, H.; Gnaser, H.; Grieser, M.; Heber, O.; Lange, M.; et al. Structure and stability of the negative hydrogen molecular ion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 193003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreckel, H.; Herwig, P.; Schwalm, D.; Čížek, M.; Golser, R.; Heber, O.; Jordon-Thaden, B.; Wolf, A. Metastable states of diatomic hydrogen anions. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 488, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golser, R.; Gnaser, H.; Kutschera, W.; Priller, A.; Steier, P.; Wallner, A.; Čížek, M.; Horáček, J.; Domcke, W. Experimental and theoretical evidence for long-lived molecular hydrogen anions H2− and D2−. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 223003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heber, O.; Golser, R.; Gnaser, H.; Berkovits, D.; Toker, Y.; Eritt, M.; Rappaport, M.L.; Zajfman, D. Lifetimes of the negative molecular hydrogen ions: H2−, D2−, and HD−. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 73, 060501(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Hjalmars, I. Theoretical investigation of the negative hydrogen molecule ion. J. Chem. Phys. 1959, 30, 1099–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.-G.; Nichols, J.A.; Dixon, D.A. Ionization potential, electron affinity, electronegativity, hardness, and electron excitation energy: Molecular properties from density functional theory orbital energies. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 4184–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, M.; Quirke, N.; Binesti, D. The calculation of the electron affinity of atoms and molecules. Mol. Simul. 1999, 23, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWeeny, R. The electron affinity of H2: A valence bond study. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 1992, 261, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, T.E. Potential-energy curves for molecular hydrogen and its ions. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 1971, 2, 119–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, F.; Schmidt, H. Rotational and vibrational excitation of H2 by slow electron impact. Z. Naturforsch. A 1971, 26, 1603–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bruna, P.J.; Lushington, G.H.; Grein, F. Electron-spin g-factors of H2−. An ab initio study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 258, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseiwitsch, B.L. Electron Affinities of Atoms and Molecules. Adv. At. Mol. Phys. 1965, 1, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, P.; Pijper, E.; Barredo, D.; Laurent, G.; Olsen, R.A.; Baerends, E.-J.; Kroes, G.-J.; Farías, D. Reactive and nonreactive scattering of H2 from a metal surface is electronically adiabatic. Science 2006, 312, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroes, G.-J.; Díaz, C. Quantum and classical dynamics of reactive scattering of H2 from metal surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 45, 3658–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, M.S.; Delhalle, J. Outer-valence green’s function study of cycloalkane and cycloalkyl−alkane compounds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 6695–6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.M. On the photoionisation of liquid cyclohexane, 2,2,4 trimethylpentane and tetramethylsilane. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 380, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.M.; Gress, H. Single-photon absorption of liquid cyclohexane, 2,2,4 trimethylpentane and tetramethylsilane in the vacuum ultraviolet. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 377, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.Y.; Bernstein, E.R. (σ3s) Rydberg states of cyclohexane, bicyclo[2.2.2]octane, and adamantane. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 100, 8625–8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tian, Z.; Fattahi, A.; Lis, L.; Kass, S.R. Cycloalkane and Cycloalkene C-H Bond Dissociation Energies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 17087–17092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölsch, N.; Beyer, M.; Salumbides, E.J.; Eikema, K.S.E.; Ubachs, W.; Jungen, C.; Merkt, F. Benchmarking theory with an improved measurement of the ionization and dissociation energies of H2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 103002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Toriyama, K.; Nunome, K. Electron spin resonance studies of structures and reactions of radical cations of a series of cycloalkanes in low-temperature matrices. Faraday Disc. Chem. Soc. 1984, 78, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnárovits, L. Energy transfer from excited cyclohexane aromatic solutes. J. Photochem. 1984, 24, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarovits, L. Photochemistry and Radiation Chemistry of Liquid Alkanes: Formation and Decay of Low-Energy Excited States. In Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter: Chemical, Physicochemical, and Biological Consequences with Applications; Mozumder, A., Hatano, Y., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Chapter 13; pp. 365–402. ISBN 0-8247-4623-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ausloos, P.; Rebbert, R.E.; Schwarz, F.P.; Lias, S.G. Pulse- and gamma ray-radiolysis of cyclohexane: Ion recombination mechanisms. Radiat. Phys. Chem. (1977) 1983, 21, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, F.; Lipsky, S. Fluorescence of saturated hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 1969, 51, 3616–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, P.H.; Freeman, G.R. Dependence of radiation-induced conductance of liquid hydrocarbons on molecular structure. J. Chem. Phys. 1968, 49, 4394–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.F. Electrons in nonpolar dielectric liquids. IEEE Transact. Electr. Insul. 1991, 26, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.F.; Illenberger, E. Low energy electrons in non-polar liquids. Nukleonika 2003, 48, 75–82. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=ru&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=78.%09Schmidt%2C+W.F.%3B+Illenberger%2C+E.+Low+energy+electrons+in+non-polar+liquids.+Nukleonika+2003%2C+48%2C+75%E2%88%9282.&btnG= (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Casanovas, J.; Grob, R.; Delacroix, D.; Guelfucci, J.P.; Blanc, D. Photoconductivity studies in some nonpolar liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 75, 4661–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, K.; Inokuchi, H. The ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy of aliphatic hydrocarbons and tetramethylsilane in the solid state. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1983, 56, 2212–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachford, J.; Dyne, P.J. Vapor-phase radiolysis of cyclohexane and mixtures of benzene and cyclohexane. Can. J. Chem. 1964, 42, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnárovits, L.; Földiak, G. Influence of cyclic structure on the radiolysis of hydrocarbons. II. Radiolysis of alkylcyclopentanes and alkylcyclohexanes. Acta Chim. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1974, 82, 285–303. Available online: https://inis.iaea.org/records/1yrck-cjb36 (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Theard, L.M. Effects of Additives on the Radiolysis of Cyclohexane Vapor at 100°. J. Phys. Chem. 1965, 69, 3292–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillot, M.S. Sur la radiolyse du cyclohexane en phase solide. Int. J. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1970, 2, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchapin, I.Y.; Nekhaev, A.I. The boundary between two modes of gas evolution: Oscillatory (H2 and O2) and conventional redox (O2 only), in the hydrocarbon/H2O2/Cu(II)/CH3CN system. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 74–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).