Abstract

In this paper, we report the effects of cold rolling, ball milling, and cold pressing on the first hydrogenation behavior of Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 alloy synthesized by gas atomization and exposed to the air for an extended period. It was found that cold pressing led to a higher hydrogen absorption capacity of 1.9 wt.%, while ball milling significantly improved the kinetics, achieving an incubation time of only 7 min. The cold-rolled sample (5 passes) showed a hydrogen absorption capacity similar to the ball-milled sample (1.5 wt.%) but with a slower hydrogenation rate. To further optimize the cold rolling process, the influence of the rolling atmosphere and the number of passes was systematically examined. In both air and argon, increasing the number of cold rolling passes resulted in longer incubation times. However, samples rolled under argon showed shorter incubation times compared to those rolled in the air. The difference between the two atmospheres became more pronounced after 20 rolling passes; the sample rolled in argon showed an incubation time of 55 min, whereas the sample rolled in air failed to absorb hydrogen even after 24 h.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen storage using metal hydrides is recognized as a safe and cost-effective method, providing high volumetric hydrogen density at moderate temperatures and pressures [1,2,3]. Among the reversible metal hydrides, FeTi-based alloys are interesting due to their ability to undergo reversible hydrogen absorption at conditions close to room temperature and atmospheric pressure, as well as the abundance and accessibility of their constituent elements [4,5,6,7].

FeTi hydrogen storage alloys suffer from sluggish hydrogen uptake, primarily due to the formation of stable oxide layers on the surface [8,9,10]. Activation of the TiFe alloys synthesized through conventional methods such as arc melting requires repeated heating cycles at approximately 400 °C under vacuum, followed by exposure to high hydrogen pressures (up to 6.5 MPa) to initiate hydrogen absorption [11]. This necessity for high-temperature and high-pressure activation represents an additional cost and a significant barrier to their commercial application.

Various strategies have been proposed to enhance the absorption kinetics of these materials. One common approach is partial substitution of Fe by transition metals such as Mn [12,13,14,15,16], Cr [17,18], and Ni [19,20]. Modi et al. reported that the reactivation of the TiFe0.85Mn0.15 alloy, which had been deactivated due to surface oxidation from air exposure, was significantly improved by applying a single heat treatment cycle (without the need for multiple heat treatments) at temperatures up to a maximum of 300 °C under hydrogen pressure [14]. Chung and Lee observed that partially substituting Fe with Mn promoted activation, which was attributed to the formation of secondary phases [21]. Fruchart et al. also reported that Mn addition increases the unit cell volume, which facilitates the hydrogen absorption at lower pressures [22].

Furthermore, the addition of a small amount of Zr to TiFe often leads to the formation of a secondary phase which acts as a gateway for hydrogen diffusion [23,24,25,26,27,28]. Manna et al. found that as-cast TiFe + 4 wt.% Zr absorbed 1.5 wt.% hydrogen after 45 min of incubation time [24]. Jain et al. demonstrated that the addition of zirconium, either in its pure form or as an alloy, enabled the activation of TiFe after arc melting, without requiring any prior treatment [28].

Mechanical treatments such as cold rolling (CR) [24,29,30,31], ball milling (BM) [32,33,34,35], and high-pressure torsion (HPT) [36,37] are also promising methods for improving the activation behavior of TiFe alloys. These techniques can introduce defects, reduce particle size, and create fresh surfaces that enhance hydrogen uptake kinetics [24,29,38]. Abe et al. found that TiFe alloys synthesized via mechanical alloying followed by annealing could absorb hydrogen at room temperature. They observed that the first hydrogenation behavior of mechanically alloyed TiFe was significantly improved compared to conventional TiFe alloys produced by induction melting [34]. Chiang et al. prepared TiFe by arc melting and subjected the alloy to ball milling under hydrogen [39]. Their findings indicated that ball milling in hydrogen atmosphere enabled TiFe to absorb hydrogen without requiring an activation treatment. Vega et al. reported that TiFe processed by arc melting and subsequently subjected to 20 or 40 cold rolling passes under an inert atmosphere could absorb hydrogen rapidly at room temperature without the need for thermal activation, reaching a hydrogen absorption capacity of 1.4 wt% [30]. Gómez et al. found that nanostructured TiFe synthesized by the high-pressure torsion (HPT) method could absorb hydrogen at room temperature with fast kinetics after an activation treatment by a single-cycle evacuation at 673 K for 2 h [37]. Manna et al. studied TiFe + 4 wt% Zr + 2 wt% Mn alloy produced by the induction melting method and reported that after seven days of air exposure, the first hydrogenation kinetics were slow, with a long incubation time [24]. After 30 days of air exposure, no hydrogen absorption was observed. However, they showed that the air-exposed alloy could still be hydrogenated after ball milling or cold rolling, although with reduced capacity and slower kinetics. Similarly, Ulate-Kolitsky et al. investigated the same TiFe + 4 wt% Zr + 2 wt% Mn alloy produced by gas atomization, a method capable of directly producing metallic powders with high cooling rates, resulting in refined microstructures [29]. They demonstrated that gas-atomized alloy exhibited finer microstructures compared to induction-melted alloy, and cold rolling was more effective in recovering the hydrogenation performance of the atomized alloy compared to induction-melted samples. These results indicate that the effectiveness of cold rolling strongly depends on the alloy’s microstructure. Patel et al. investigated the effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and hydrogenation performance of TiFe + 4 wt.% Zr alloy and found that higher cooling rate led to a finer microstructure, which significantly improved hydrogen absorption kinetics [40]. These studies suggest that gas atomization could be a promising method for the production of metal hydride alloys with refined microstructures.

Despite these advancements, most studies on TiFe-based alloys have focused on samples produced by conventional casting methods, while investigations on gas-atomized alloys remain scarce. Moreover, most existing works focus on a single mechanical processing technique (such as cold rolling or ball milling), whereas comparative evaluations of different treatments are limited. In this work, we address this gap by investigating the first hydrogenation behavior of Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 alloy synthesized by gas atomization and stored in air for more than two years. Three mechanical treatments, cold rolling, ball milling, and cold pressing, were systematically compared. In addition, the effects of rolling atmosphere and number of passes on the first hydrogenation are reported. This approach provides new insights into how different processing routes influence the activation of gas-atomized TiFe-based alloys.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 alloy in powder form was provided by GKN Hoeganaes (Cinnaminson, NJ, USA). The powder was produced via gas atomization under an argon atmosphere. After production, the samples were stored in the air for over 2 years.

2.2. Morphology and Crystal Structure

The microstructure and morphology of the powder were investigated using a Hitachi SU1510 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi High-Tech Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada). Elemental composition was determined through Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) with an Oxford Instrument X-Max system (Abingdon, UK), ensuring high analytical resolution.

The phase composition and crystal structure of the samples were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker D8 Focus powder diffractometer (Madison, WI, USA) with Cu Kα radiation. The resulting XRD patterns were evaluated using the Rietveld refinement software TOPAS V6.

2.3. Alloy Processing

High-energy ball milling was performed using a SPEX 8000M high-energy ball mill (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA). The powder-to-ball mass ratio was 1:10, and milling was carried out for 10 min using a 55 cc stainless steel crucible. The vibration frequency was 1060 cycles per minute. All the loading and unloading of the powder were performed inside an argon-filled glove box to prevent contamination.

Cold pressing was carried out using a hydraulic press manufactured by Research & Industrial Instruments Company (London, UK). A die with a diameter of 14 mm was used to compact the powder under uniaxial pressure. The sample was subjected to a force of 12 tons for 2 min. After cold pressing, the obtained pellet was manually crushed into powder using a hardened steel mortar and pestle in the air.

Cold rolling in the air was conducted using a modified Durston DRM 130 model (Durston Tools, High Wycombe, UK), with powder being rolled vertically between two 0.5 mm-thick 316 stainless steel plates to avoid contamination. For cold rolling in argon, an International Rolling Mills (Pawtucket, RI, USA) was placed inside an argon-filled glove box. Rolling speed was 20 rpm for both air and argon atmospheres. The roller gap was set to 1.1 mm; considering the combined thickness of the two steel plates (1.0 mm), the effective rolling space available for the powder was approximately 0.1 mm.

2.4. Hydrogenation Properties

The first hydrogenation tests were carried out at room temperature (25 °C) under a hydrogen pressure of 2000 kPa using a homemade Sievert-type apparatus. For each first hydrogenation test, one gram of powder was placed in the sample holder and evacuated for 15 min before the measurement.

3. Results and Discussion

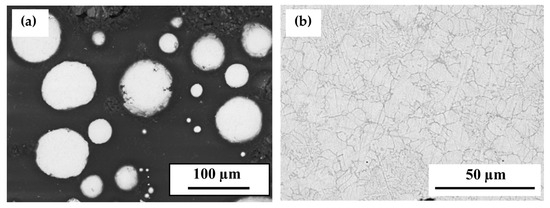

Figure 1 presents the microstructure of the atomized Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 powder, revealing two distinct regions: a grey matrix and a darker grey filamentous region.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the microstructure of the gas-atomized powder at magnifications of (a) 300× and (b) 1000×.

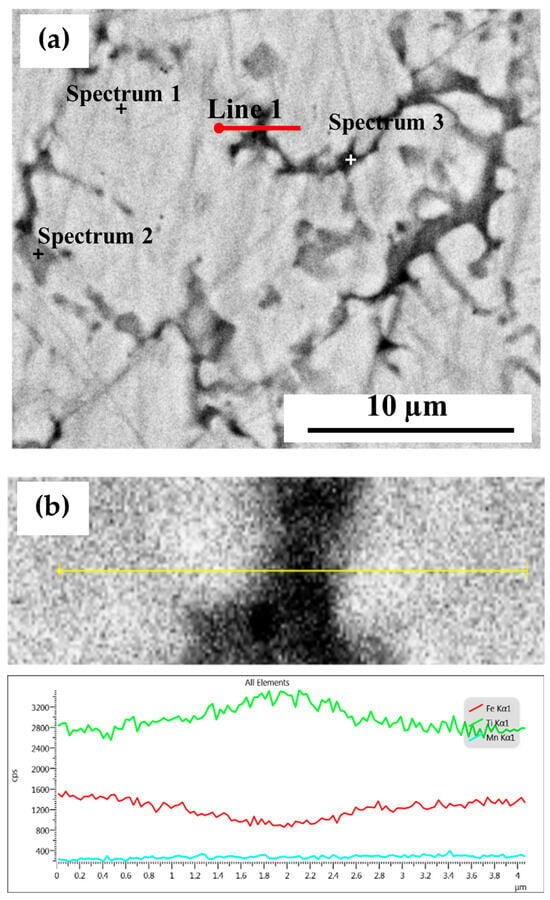

Figure 2a shows a higher-magnification backscattered electrons micrograph. At this magnification, three regions are visible. The main region (matrix) is light grey. Two secondary regions are seen: a darker grey region (Spectrum 2) and a much smaller black region (Spectrum 3). The chemical composition of the bulk material, matrix, and secondary phases, as determined by EDS, is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

(a) High-magnification backscattered electron image of the EDS-analyzed regions of the atomized powder, (b) line analysis.

Table 1.

Elemental composition in atomic percent (at. %) from EDX analysis of the gas-atomized powder. Error on the last significant digit is in parentheses.

Based on bulk composition measurement, the Ti, Fe, and Mn concentrations are near the nominal composition. The elemental concentrations of the matrix are close to TiFe, with Mn seemingly substituting on both Ti and Fe sites. Both the black and darker grey regions are rich in Ti and have a Mn concentration slightly higher than that of the matrix. For both regions, the composition is close to Ti2Fe.

The interface of the matrix and second phase was investigated by line analysis (Figure 2b). The abundance of Ti slowly increases from the edge toward the center of the secondary region while Fe abundance decreases. Mn concentration is almost constant in both the matrix and the secondary phase. There is no indication of segregation at the edge.

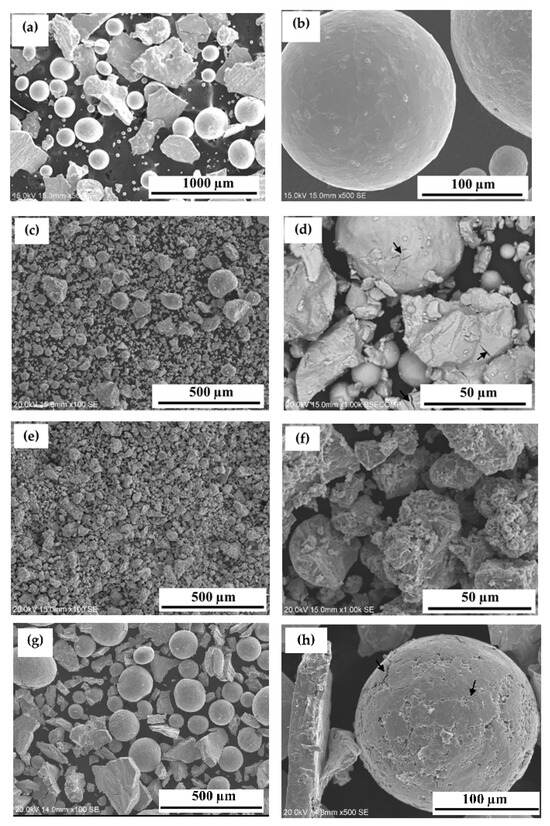

The atomized Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 alloy was exposed to hydrogen at room temperature under a pressure of 2000 kPa for 24 h. However, no hydrogen absorption was observed. Surface oxides are easily formed on TiFe alloys, which can hinder hydrogen absorption [25,38,41]. Therefore, this lack of hydrogen absorption is likely attributed to the long air exposure before hydrogenation. Previous studies have demonstrated that mechanical processing techniques, such as ball milling and cold rolling, could improve activation kinetics after air exposure by introducing cracks and generating fresh surfaces [24,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. To address the activation issue, various mechanical processing methods were applied and compared to the activation of gas-atomized Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 alloy. These included cold rolling (5 passes), ball milling (10 min), and cold pressing. Figure 3 illustrates the morphology of the atomized and mechanically processed powders. Figure 3a,b show that the atomized powder consists of a mixture of spherical and irregularly shaped particles. The spherical particles range in size from less than 20 µm to 300 µm, while the irregularly shaped particles measure between 100 µm and 400 µm.

Figure 3.

Morphology of gas-atomized powder (a,b); mechanically processed powders after 5 passes of cold rolling (c,d), 10 min of ball milling (e,f), and cold pressing (g,h).

After five passes of cold rolling, the average particle size decreased significantly due to the fragmentation of larger particles under mechanical deformation (Figure 3c). Most of the particles were very small, with sizes below 20 µm. However, some larger particles, approximately 100 µm in size, could still be observed, indicating that the fragmentation process is not entirely uniform. Figure 3d further highlights the formation of cracks and highly fragmented particles, which become more evident at higher magnification. The cracks are marked with arrows.

Ball milling also resulted in the breakdown of particles into finer, irregularly shaped particles (Figure 3e,f). In contrast, cold pressing did not significantly reduce the average particle size (Figure 3g). However, a higher-magnification image (Figure 3h) reveals the presence of numerous cracks on both spherical and irregular particles.

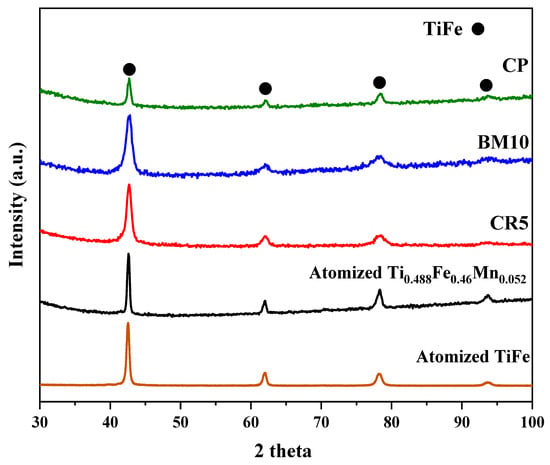

The XRD patterns of atomized Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 and mechanically processed samples before hydrogenation are presented in Figure 4. In addition, the XRD pattern of atomized TiFe is shown as reference sample. In all cases, only the TiFe phase is seen with no indication of other phases. As shown in Figure 1, the secondary regions exhibit a thin, filamentous structure and are present in a relatively small quantity compared to the matrix. Due to its limited volume and morphology, the diffraction intensity of these secondary phases was weak. Similarly, surface oxides typically form only a very thin layer (often just a few nanometers thick) on the powder surface. Because they are so thin and not very abundant, their XRD Bragg’s peaks are very weak and broad, making them hard to distinguish from the background.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of gas-atomized powder and mechanically processed powders (5CR-10BM-CP) before hydrogenation.

Table 2 summarizes the Rietveld refinement results based on the XRD patterns of Figure 4. As the TiFe pattern was taken on a different diffractometer, we could not perform Rietveld’s refinement on this one using the fundamental parameters. However, the lattice parameter of TiFe phase in reference TiFe alloys was 2.97971 (6) Å. Substituting Mn by Fe led to increase in lattice parameter to 2.9828 (4). The lattice parameters remained nearly constant across atomized Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 and mechanically processed samples. However, a reduction in crystallite size and an increase in microstrains were observed after mechanical processing, which can be attributed to the introduction of defects and dislocations in the crystal lattice. Among the samples, the ball-milled powder displayed the smallest crystallite size and the highest microstrain, whereas the cold-pressed sample exhibited the largest crystallite size and the lowest microstrain.

Table 2.

Rietveld’s refinement of TiFe phase. The error on the last significant digit is shown in parentheses.

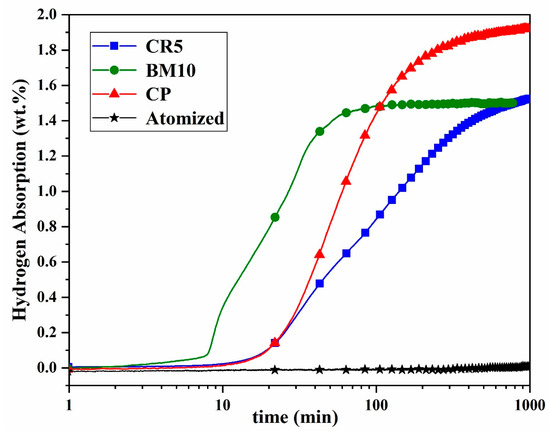

Figure 5 shows the hydrogenation curves for all samples at room temperature and hydrogen pressure of 2000 kPa. Unlike the as-received (gas-atomized) Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 sample, which did not absorb hydrogen, all mechanically processed samples successfully absorbed hydrogen. It is worth mentioning that pure TiFe alloy could not absorb hydrogen at room temperature and hydrogen pressure of 2000 kPa, even after mechanical processing, whereas the Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 alloy readily absorbed hydrogen following mechanical processing.

Figure 5.

Hydrogenation curves at room temperature under 2000 kPa hydrogen pressure for as-received and mechanically processed powders.

The cold-pressed sample exhibited the highest hydrogen absorption capacity of 1.9 wt.%, and cold-rolled and ball-milled samples both reached 1.5 wt.% after 24 h. In terms of kinetics, the BM10 sample demonstrated the fastest hydrogenation, with an incubation time of about 7 min, while both cold-rolled and cold-pressed samples had a longer incubation time of approximately 15 min.

Remarkably, despite the atomized powder being exposed to air for more than two years, each type of mechanical processing was able to activate the alloy and achieve good hydrogenation kinetics. For comparison, Modi et al. investigated the hydrogenation behavior of a TiFe0.85Mn0.15 alloy produced by arc melting [14]. After arc melting the alloy was subjected to ball milling for 30 min. Ball-milled alloy exhibited good kinetics and absorbed 1.2 wt.% hydrogen with no incubation time. However, after exposure to air for just 2 h, the alloy became oxidized and lost its hydrogen absorption capability. By heating to 300 °C under hydrogen pressure, reactivation was achieved, but with a prolonged incubation time of 40 min and a reduced capacity of 0.9 wt.%. In the present work, all mechanical treatments activated the alloy with shorter incubation times and higher hydrogen capacities compared to Modi et al., which can be attributed to microstructural differences between gas-atomized and arc-melted alloys.

Dematteis et al. further studied TiFe-alloys with partial substitution of Fe by Ti and Mn [16]. Samples with different compositions in the range from 48.8 at% to 54.1 at% Ti, and from 0 to 5.3 at% Mn were prepared by induction melting and subsequent annealing at 1000 °C for one week. Their results showed that activation generally required 5 MPa of hydrogen pressure and heating up to 400 °C. Only Ti-rich compositions could be activated under milder conditions (room temperature and 2500 kPa H2). Although the alloy studied here is not Ti-rich, it was activated at room temperature and moderate pressure, which can be attributed to the finer microstructure of the gas-atomized material compared to induction-melted alloys.

The improvement in hydrogenation behavior after mechanical processing can be attributed to the refinement of the crystalline structure and the introduction of defects during deformation. As observed in Figure 3, mechanical processing induced cracks in the particles, likely facilitating hydrogen diffusion. The mechanical processing also introduces structural defects, such as vacancies and dislocations, which further enhance hydrogen transport within the material [42]. Rietveld refinement analysis revealed a decrease in crystallite size after mechanical processing, which corresponded to an increase in grain boundary density. These grain boundaries could serve as pathways that facilitate hydrogen diffusion [24,32,43]. Consequently, the hydrogenation kinetics improve after mechanical processing due to the combined effects of particle fragmentation, reduction in crystallite size, and the formation of grain boundaries.

As previously mentioned, the ball-milled sample not only exhibited the shortest incubation time but also demonstrated the fastest hydrogenation kinetics. As shown in Table 2, the BM10 sample had the smallest crystallite size, which implies a higher grain boundary density. Grain boundaries can facilitate hydrogen diffusion and act as nucleation sites for hydride formation [44]. In the study of Emami et al., it was reported that ball milling leads to the formation of nanograins, and the nanograin boundaries act as effective pathways for hydrogen diffusion [32].

Beyond the kinetics, differences in hydrogen storage capacity among the samples indicate the influence of mechanical processing on hydrogen storage behavior. As shown in Figure 5, the cold-pressed sample exhibited the highest capacity of 1.9 wt.% ± 0.1 wt.%. This value agrees with the nominal hydrogen capacity of TiFe alloy (1.86 wt.%).

According to the hydrogenation curves in Figure 5, after 1000 min, the cold-rolled sample continues to absorb hydrogen at a very slow rate, while the ball-milled sample has already reached its maximum capacity (1.5 wt.%). This indicates that the ball-milled sample had a lower overall capacity compared to the cold-pressed one. The reduced capacity of the ball-milled sample may be attributed to the crystallite size. As previously discussed, the BM10 sample had the smallest crystallite size, resulting in a higher density of grain boundaries. Lv et al. found that as ball milling time increased and crystallite size decreased, the hydrogen storage capacity decreased [43]. They proposed that although grain boundaries facilitate hydrogen diffusion, they do not store hydrogen themselves. This may explain the lower overall capacity of the ball-milled sample, despite its faster kinetics and shorter incubation time.

Regarding the cold-rolled sample, the loss of capacity may be explained by the formation of oxides as the cold rolling was performed in the air. To verify this hypothesis, cold rolling was performed under both air and argon atmospheres for 5, 10, and 20 passes to compare the influence of rolling atmosphere on the hydrogenation behavior.

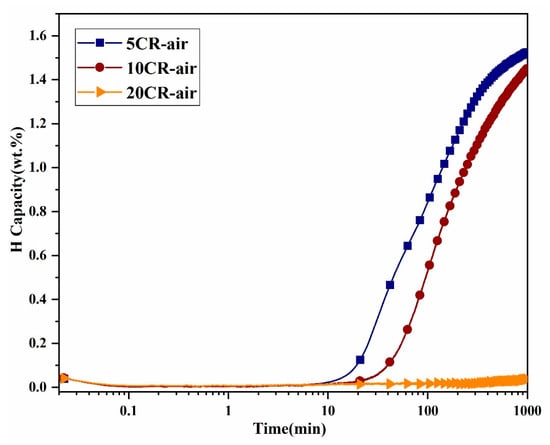

Figure 6 shows hydrogenation curves at room temperature and hydrogen pressure of 2000 kPa for cold-rolled samples in the air. After 5 CR in the air, absorption started after 15 min of incubation time. With 10 CR in air incubation time was increased to 35 min. After 20 CR in the air, the sample was not activated in 24 h. The difference in incubation time could be related to the surface condition of the materials. Increasing cold rolling passes in the air may lead to surface oxidation that can act as barriers to hydrogen absorption. Sleiman et al. similarly reported that while the as-cast Ti1V0.9Cr1.1 alloy could not be activated, a single cold rolling pass enabled immediate activation [45]. However, when the number of passes increased to six, the incubation time rose to about 10 min, the activation kinetics slowed, and the absorption capacity decreased.

Figure 6.

Activation curves of 5, 10, and 20 passes cold-rolled powders in air at RT/2000 kPa.

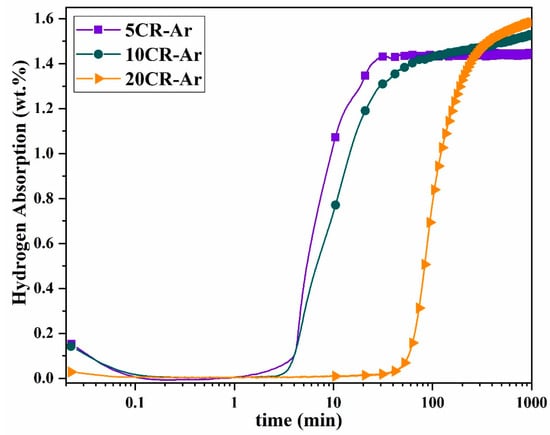

Figure 7 shows the first hydrogenation of samples cold rolled in argon. Compared to rolling in the air, the incubation time is shorter. After 5 and 10 rolling passes, the incubation times were only 3 and 4 min, respectively. The hydrogen absorption capacity after 24 h was about 1.5 wt.%, which is like the samples rolled in the air. The most notable difference appeared after 20 passes; while the 20CR-air sample showed no activation within 24 h, the 20CR-argon sample began absorbing hydrogen after 55 min and reached a capacity of 1.6 wt.% after 24 h. Even under argon atmosphere, increasing the number of cold rolling passes to 20 resulted in a longer incubation time (55 min), similar to what was observed for cold-rolled samples in the air. This suggests that, regardless of oxidation, excessive deformation may hinder the first hydrogenation. This could be attributed to the excessive plastic deformation induced by multiple passes. As the number of passes increases, the material accumulates a higher density of dislocations, defects, and internal stresses, which can disrupt hydrogen diffusion.

Figure 7.

Activation curves of 5, 10, and 20 passes cold-rolled powders in argon at RT/2000 kPa.

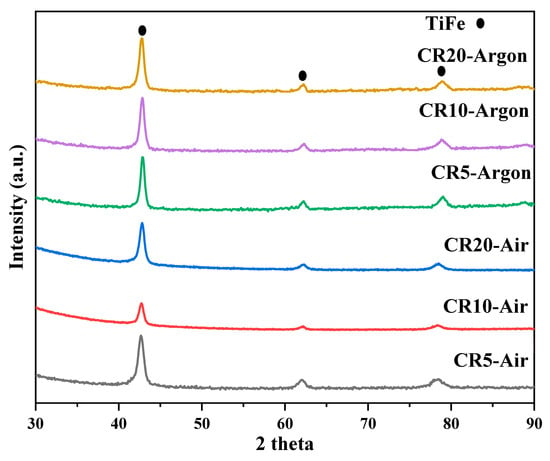

The crystal structure of cold rolled samples in the air and argon was investigated by X-ray diffraction, and the patterns are shown in Figure 8. The corresponding Rietveld refinement data are summarized in Table 3. We see that increasing the number of rolling passes led to a reduction in crystallite size and increasing microstrain. The effect was the same for the samples rolled in argon compared to the ones rolled in the air. In fact, the crystal parameters were essentially the same for the air and argon cases. Therefore, the difference in incubation time between air and argon rolling atmosphere could not be attributed to a different crystal structure. It should be due to some surface effect that could not be seen by X-ray diffraction due to the large penetration depth of the oxides. The possible Ti, Fe and TiFe oxides have penetration depth between 2 and 10 microns. Considering that the surface oxide should have a thickness of nm, it is understandable that the presence of oxides could not be seen by X-ray diffraction. We are planning to perform XPS to obtain a better understanding of the surface composition.

Figure 8.

XRD patterns of cold rolled samples in air and argon before hydrogenation.

Table 3.

Rietveld’s refinement of TiFe phase in cold rolled samples in air and argon. The error on the last significant digit is shown in parentheses.

4. Conclusions

The effects of cold rolling, ball milling, and cold pressing on the microstructure and hydrogen storage properties of Ti0.488Fe0.460Mn0.052 alloy were investigated. Cold pressing resulted in the highest hydrogen absorption capacity among the three methods, while ball milling significantly improved the first hydrogenation kinetics compared to cold rolling and cold pressing. Increasing the number of cold rolling passes in the air reduced hydrogen absorption kinetics, probably because of surface oxidation. Cold rolling under argon atmosphere produced a fast first hydrogenation. However, a higher number of passes in argon led to longer incubation times, suggesting that excessive deformation may hinder the first hydrogenation. These results suggest that combining different mechanical treatments could be explored in future studies to optimize both capacity and hydrogenation rate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and J.H.; validation, S.H. and J.H.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H., C.S. and J.H.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, J.H. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MITACS Project IT Number: IT28247/Canadian Academic Institution: UQTR/Canadian Academic Supervisor: Jacques Huot/Partner Organization: GKN (Hoeganaes Corporation).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Seyedehfaranak Hosseinigourajoubi acknowledges GKN Hoeganaes Innovation Centre and Advanced Materials and MITACS for the fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

Author, Chris Schade, is employed by GKN Company, which provided funding and supplied the samples for this study. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CR | Cold Rolling |

| BM | Ball Milling |

| CP | Cold Pressing |

| HPT | High-Pressure Torsion |

References

- Bernauer, O.; Halene, C. Properties of metal hydrides for use in industrial applications. J. Less Common Met. 1987, 131, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakintuna, B.; Lamari-Darkrim, F.; Hirscher, M. Metal hydride materials for solid hydrogen storage: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlapbach, L.; Züttel, A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature 2001, 414, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.D. Reactivation behaviour of TiFe hydride. J. Alloys Compd. 1994, 215, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraki, T.; Oishi, K.; Uchida, H.; Miyamoto, Y.; Abe, M.; Kokaji, T.; Uchida, S. Properties of hydrogen absorption by nano-structured FeTi alloys. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 99, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanyin, S.; Fangjie, L.; Deyou, B. An advanced TiFe series hydrogen storage material with high hydrogen capacity and easily activated properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1990, 15, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadorozhnyy, V.; Klyamkin, S.; Zadorozhnyy, M.; Bermesheva, O.; Kaloshkin, S. Hydrogen storage nanocrystalline TiFe intermetallic compound: Synthesis by mechanical alloying and compacting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 17131–17136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, T. On the activation of FeTi for hydrogen storage. J. Less Common Met. 1983, 89, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bläsius, A.; Gonster, U. Mössbauer surface studies on Tife hydrogen storage material. Appl. Phys. 1980, 22, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jai-Young, L.; Park, C.N.; Pyun, S.M. The activation processes and hydriding kinetics of FeTi. J. Less Common Met. 1983, 89, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J.; Wiswall, R.H. Formation and properties of iron titanium hydride. Inorg. Chem. 1974, 13, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, E.; Berti, N.; Cuevas, F.; Latroche, M.; Baricco, M. Substitutional effects in TiFe for hydrogen storage: A comprehensive review. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 2524–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhee, S.P.; Roy, A.; Pati, S. Role of Mn-substitution towards the enhanced hydrogen storage performance in FeTi. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9357–9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, P.; Aguey-Zinsou, K.-F. Titanium-iron-manganese (TiFe0.85Mn0.15) alloy for hydrogen storage: Reactivation upon oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 16757–16764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.-M.; Qi, Z.; Zhai, T.-T.; Wang, H.-Z.; Wang, H.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-H. Effects of La substitution on microstructure and hydrogen storage properties of Ti–Fe–Mn-based alloy prepared through melt spinning. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, E.M.; Dreistadt, D.M.; Capurso, G.; Jepsen, J.; Cuevas, F.; Latroche, M. Fundamental hydrogen storage properties of TiFe-alloy with partial substitution of Fe by Ti and Mn. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 874, 159925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lee, S.-I.; Faisal, M.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.-S.; Suh, J.-Y.; Shim, J.-H.; Huh, J.-Y.; Cho, Y.W. Effect of Cr addition on room temperature hydrogenation of TiFe alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 19478–19485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.B.; Ko, W.-S.; Fadonougbo, J.O.; Na, T.-W.; Im, H.-T.; Park, J.-Y.; Kang, J.-W.; Kang, H.-S.; Park, C.-S.; Park, H.-K. Effect of Fe substitution by Mn and Cr on first hydrogenation kinetics of air-exposed TiFe-based hydrogen storage alloy. Mater. Charact. 2021, 178, 111246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komedera, K.; Michalik, J.; Sworst, K.; Gondek, Ł. Structure, Microstructure and Hyperfine Interactions in Hf- and Ni-Substituted TiFe Alloy for Hydrogen Storage. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2024, 146, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yan, Z.; Han, Z.; Li, J.; Zhai, T.; Yuan, Z.; Li, T.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y. Hydrogen storage properties of TiFe-based composite with Ni addition. Heliyon 2024, 10, e41022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Effect of partial substitution of Mn and Ni for Fe in FeTi on hydriding kinetics. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1986, 11, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruchart, D.; Commandré, M.; Sauvage, D.; Rouault, A.; Tellgren, R. Structural and activation process studies of Fe Ti-like hydride compounds. J. Less Common Met. 1980, 74, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Liu, Z.; Dixit, V. Improved hydrogen storage properties of TiFe alloy by doping (Zr+2V) additive and using mechanical deformation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 27843–27852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, J.; Tougas, B.; Huot, J. Mechanical activation of air exposed TiFe + 4 wt% Zr alloy for hydrogenation by cold rolling and ball milling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 20795–20800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, X.; Liu, B.; Wei, X.; Zhang, W.; Lan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Z. Effects of Zr doping on activation capability and hydrogen storage performances of TiFe-based alloy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 2256–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Sharma, P.; Huot, J. Effect of annealing on microstructure and hydrogenation properties of TiFe + X wt% Zr (X = 4, 8). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 6238–6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Huot, J.; Sharma, P. Hydrogen storage properties of TiFe + X wt.% Zr, V (X = 0, 4) alloys. In Proceedings of the 2016 Canadian Association of Physicists (CAP) Congress, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 13–17 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Gosselin, C.; Huot, J. Effect of Zr, Ni and Zr7Ni10 alloy on hydrogen storage characteristics of TiFe alloy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 16921–16927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulate-Kolitsky, E.; Tougas, B.; Neumann, B.; Schade, C.; Huot, J. First hydrogenation of mechanically processed TiFe-based alloy synthesized by gas atomization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 7381–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.; Leiva, D.; Neto, R.L.; Silva, W.; Silva, R.; Ishikawa, T.; Kiminami, C.; Botta, W. Mechanical activation of TiFe for hydrogen storage by cold rolling under inert atmosphere. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 2913–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.B.; Beatrice, C.A.G.; Leal, R.M.; Silva, W.B.; Pessan, L.A.; Botta, W.J.; Leiva, D.R. Hydrogen absorption/desorption behavior of a cold-rolled TiFe intermetallic compound. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20210204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, H.; Edalati, K.; Matsuda, J.; Akiba, E.; Horita, Z. Hydrogen storage performance of TiFe after processing by ball milling. Acta Mater. 2015, 88, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.E.R.; Leiva, D.R.; Leal Neto, R.M.; Silva, W.B.; Silva, R.A.; Ishikawa, T.T.; Kiminami, C.S.; Botta, W.J. Improved ball milling method for the synthesis of nanocrystalline TiFe compound ready to absorb hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 2084–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Kuji, T. Hydrogen absorption of TiFe alloy synthesized by ball milling and post-annealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 446–447, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, I.; Abe, M.; Uchida, H.; Hattori, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Haraki, T. Hydrogen sorption kinetics of FeTi alloy with nano-structured surface layers. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 580, S33–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edalati, K.; Matsuda, J.; Arita, M.; Daio, T.; Akiba, E.; Horita, Z. Mechanism of activation of TiFe intermetallics for hydrogen storage by severe plastic deformation using high-pressure torsion. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 143902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E.I.L.; Edalati, K.; Antiqueira, F.J.; Coimbrão, D.D.; Zepon, G.; Leiva, D.R.; Ishikawa, T.T.; Cubero-Sesin, J.M.; Botta, W.J. Synthesis of Nanostructured TiFe Hydrogen Storage Material by Mechanical Alloying via High-Pressure Torsion. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 2000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Hu, D.; Yang, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Activation, modification and application of TiFe-based hydrogen storage alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 274–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.H.; Chin, Z.H.; Perng, T.P. Hydrogenation of TiFe by high-energy ball milling. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 307, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Tougas, B.; Sharma, P.; Huot, J. Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and hydrogen storage properties of TiFe with 4 wt% Zr as an additive. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 5623–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Ha, T.; Suh, J.-Y.; Kim, D.-I.; Lee, Y.-S.; Shim, J.-H. Orientation relationship between TiFeH and TiFe phases in AB-type Ti–Fe–V–Ce hydrogen storage alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 983, 173943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edalati, K.; Matsuo, M.; Emami, H.; Itano, S.; Alhamidi, A.; Staykov, A.; Smith, D.J.; Orimo, S.-I.; Akiba, E.; Horita, Z. Impact of severe plastic deformation on microstructure and hydrogen storage of titanium-iron-manganese intermetallics. Scr. Mater. 2016, 124, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Guzik, M.N.; Sartori, S.; Huot, J. Effect of ball milling and cryomilling on the microstructure and first hydrogenation properties of TiFe+4wt.% Zr alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 1828–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubicza, J. (Ed.) Chapter 11—Relationship Between Microstructure and Hydrogen Storage Properties of Nanomaterials. In Defect Structure and Properties of Nanomaterials, 2nd ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, S.; Aliouat, A.; Huot, J. Enhancement of First Hydrogenation of Ti1V0.9Cr1.1 BCC Alloy by Cold Rolling and Ball Milling. Materials 2020, 13, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).