Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells for Aircraft Applications: A Comprehensive Review of Key Challenges and Development Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Hydrogen Power Technologies and Their Feasibility for Applications in the Aviation Field

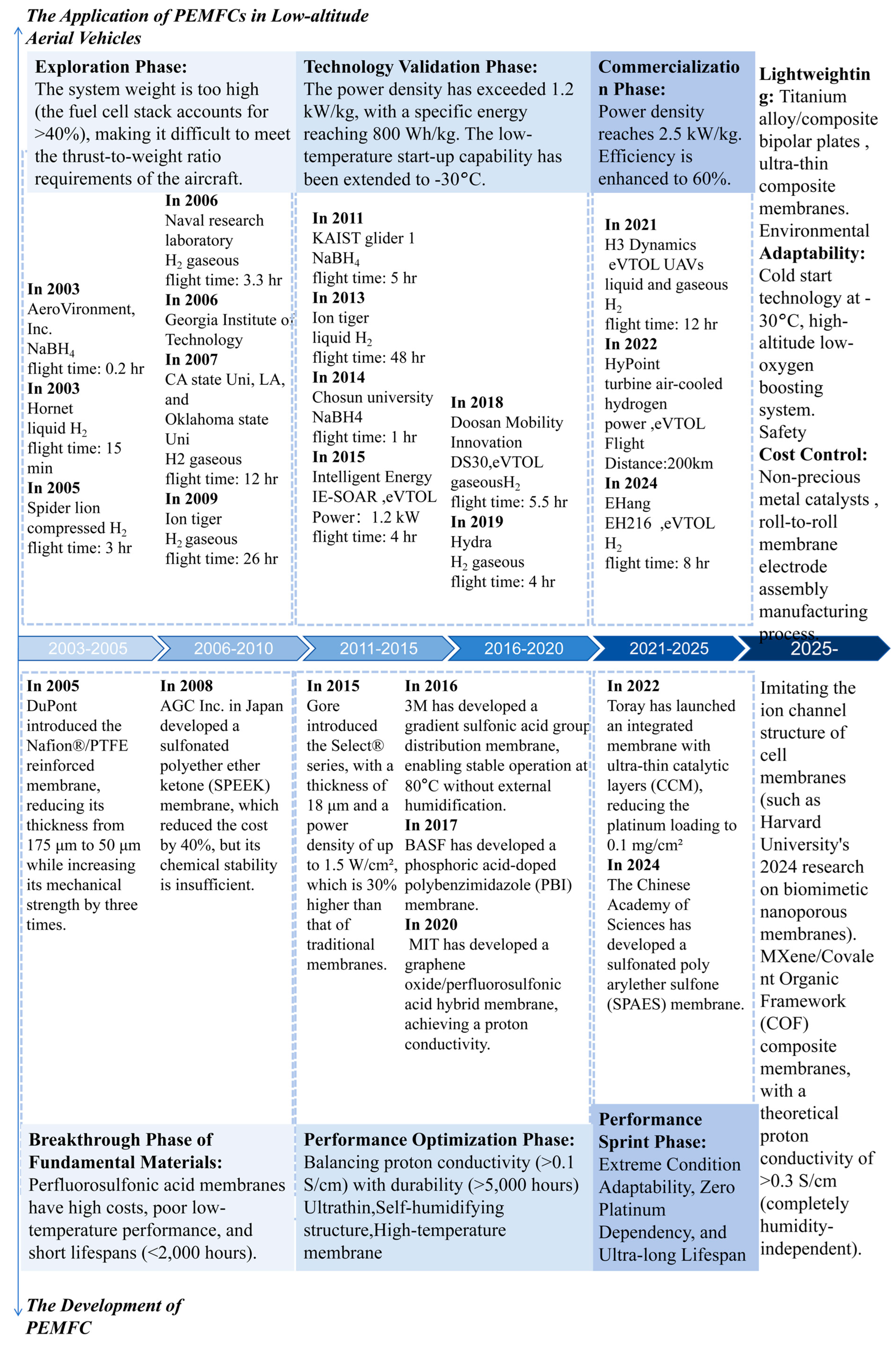

3. Current Status of PEMFC Research in Low-Altitude Aircraft

3.1. Commercial Aircraft

3.2. Electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing Aircraft

4. Challenges in the Technological Development of PEMFCs for Low-Altitude Aircraft

4.1. Hydrogen Storage and Spatial Constraints

4.2. Thermal Management and System Integration Optimization

4.3. Cost and Durability Issues in Aviation Applications

4.4. Performance of Hybrid Power Systems

4.5. Environmental Adaptability

5. Development Trends of PEMFC Applications in Low-Altitude Aircraft

5.1. General Development Trends

5.2. Hydrogen Fuel Cell as Main Power Supply

5.3. Hydrogen-Electric Hybrid Power System

5.4. Hydrogen Fuel Cell as Auxiliary Power

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eVTOL | electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing |

| PEMFCs | Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| ICCT | International Council on Clean Transportation |

| CAGR | The compound annual growth rate |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| AFC | Alkaline Fuel Cells |

| APUs | Auxiliary Power Units |

| UAVs | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engines |

| CAJU | Clean Aviation Joint Undertaking |

| HEROPS | Hydrogen-Electric Zero-Emission Propulsion System |

| HEPS | Hybrid-Electric Propulsion System |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| GI | weight index |

References

- Bahari, M.; Rostami, M.; Entezari, A.; Ghahremani, S.; Etminan, M. Performance evaluation and multi-objective optimization of a novel UAV propulsion system based on PEM fuel cell. Fuel 2022, 311, 122554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B. CO2 Emissions from Commercial Aviation: 2013, 2018, and 2019 Analysis, International Council on Clean Transportation. United States of America. 2020. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/62jb1j (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Bergero, C.; Gosnell, G.; Gielen, D.; Kang, S.; Bazilian, M.; Davis, S.J. Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.; Bisht, A.; Witherspoon, B.; Essehli, R.; Amin, R.; Duncan, A.; Hines, J.; Kweon, C.-B.M.; Belharouak, I. Battery Electrolyte Design for Electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing (eVTOL) Platforms. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2400772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, N.; Self, E.C.; Dixit, M.; Du, Z.; Essehli, R.; Amin, R.; Nanda, J.; Belharouak, I. Next generation cobalt free cathodes a prospective solution to the battery industry’s cobalt problem. Transit. Met. Oxides Electrochem. Energy Storage 2022, 12, 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Toghyani, S.; Cistjakov, W.; Baakes, F.; Krewer, U. Conceptual design of solid-state Li-battery for urban air mobility. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ding, S. Overview and Research on Airworthiness and Safety of Electrical Propulsion and Battery Technologies in eVTOL; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, D.; Lim, D.; Yee, K.J. A refined sizing method of fuel cell-battery hybrid system for eVTOL aircraft. Appl. Energy 2022, 328, 120160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.H.; Kwon, D.Y.; Jeon, K.S.; Tyan, M.; Lee, J.W. Advanced sizing methodology for a multi-mode EVTOL UAV powered by a hydrogen fuel cell and battery. Aerospace 2022, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, E.J.; Martins, J.R.R.A. Hydrogen-powered aircraft: Fundamental concepts, key technologies, and environmental impacts. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2023, 141, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, A.; Verstraete, D. Fuel cell propulsion in small fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicles: Current status and research needs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 21311–21333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, J.A.; Sehra, A.K.; Colantonio, R.O. NASA aeropropulsion research: Looking forward. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Symposium on Airbreathing Engines, Bangalore, India, 2–7 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Timlon, J. ZeroAvia: Building a Green Business at Scale to Accelerate Sustainable Aviation; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Verde, A. Competition Dynamics and Market Power: Analysis of the Duopoly Between Airbus and Boeing in the Civil Aircraft Manufacturing Industry. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qasem, N.A.A.; Abdulrahman, G.A.Q. A recent comprehensive review of fuel cells: History, types, and applications. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 7271748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijing, G.; Shufan, H.; Lihong, Y.; Jun, C. Heat Transfer Performance of Flat Heat Pipes for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Chem. Eng. 2024, 52, 41–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Jian, Q.; Huang, B.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Cao, S. Experimental study on temperature characteristics of an air-cooled proton exchange membrane fuel cell stack. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, F.; Wu, X. Analysis and review on air-cooled open cathode proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Bibliometric, environmental adaptation and prospect. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 197, 114408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yang, S.; Deng, C.W. A review on temperature control of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Processes 2021, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.Q.; Ding, Q.; Xu, J.H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.M.; Wan, Z.-M.; Wang, X.-D. Dynamic performance for a kW-grade air-cooled proton exchange membrane fuel cell stack. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 35398–35411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, A.T.; Orhan, M.F.; Kannan, A.M. Alkaline fuel cells: Status and prospects. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 6396–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, M.; Qaq, Z.; Orhan, M. Design and analysis of an alkaline fuel cell. J. Therm. Eng. 2023, 9, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, G.E.; Osipov, B.M.; Titov, A.V.; Akhmetshin, A.R. Gas turbine operating as part of a thermal power plant with hydrogen storages. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 33393–33400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A. Towards hydrogen gas turbine engines aviation: A review of production, infrastructure, storage, aircraft design and combustion technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 88, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarakhanova, R.Y.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Zharkov, M.A.; Udovichenko, A.V. Starter-generator system of a hydrogen-fueled aircraft. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 99, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, H. Optimization of combustion and performance parameters by intake-charge conditions in a small-scale air-cooled hydrogen fuelled SI engine suitable for use in piston-prop aircraft. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2021, 93, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depcik, C.; Cassady, T.; Collicott, B.; Burugupally, S.P.; Li, X.; Alam, S.S.; Arandia, J.R.; Hobeck, J. Comparison of lithium ion Batteries, hydrogen fueled combustion Engines, and a hydrogen fuel cell in powering a small Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 207, 112514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, E.B.; Ampah, J.D.; Wilberforce, T.; Afrane, S.; Nutakor, C. Research progress, trends, and current state of development on PEMFC-new insights from a bibliometric analysis and characteristics of two decades of research output. Membranes 2022, 12, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, P.C.; Wit, A.; van Benthem, R.C. Development of a Liquid Hydrogen-Based Fuel Cell System for the HYDRA-2 Drone; AIAA SciTech 2022 Forum; Netherlands Aerospace Centre NLR: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; p. 443. [Google Scholar]

- Sparano, M.; Sorrentino, M.; Troiano, G.; Cerino, G.; Piscopo, G.; Basaglia, M.; Pianese, C. The future technological potential of hydrogen fuel cell systems for aviation and preliminary co-design of a hybrid regional aircraft powertrain through a mathematical tool. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 281, 116822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ji, Y. Analysis and Prospects of Key Technologies for Hydrogen-Electric Regional Aircraft. In Proceedings of the 6th China Aeronautical Science and Technology Conference, Wuzhen, China, 26–27 September 2023; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhaya, J. Performance Analysis of Fuel Cell Retrofit Aircraft; ICCT White Paper; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Thipphavong, D.P.; Apaza, R.; Barmore, B.; Battiste, V.; Belcastro, C.; Burian, B.; Dao, A.-Q.V.; Feary, M.; Go, S.; Goodrich, K.H.; et al. Urban air mobility airspace integration concepts and considerations. In Proceedings of the 2018 Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–29 June 2018; p. 3676. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, Engineering. Advancing Aerial Mobility: A National Blueprint; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Joby Aviation Generates First Revenue, Takes Key Step towards Certifying Aircraft. Available online: https://www.jobyaviation.com/news/joby-aviation-generates-first-revenue-takes-key-step-towards-certifying-aircraft/ (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Baroutaji, A.; Wilberforce, T.; Ramadan, M.; Olabi, A.G. Comprehensive investigation on hydrogen and fuel cell technology in the aviation and aerospace sectors. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 106, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobariz, K.N.; Youssef, A.M.; Abdel-Rahman, M. Long endurance hybrid fuel cell-battery powered UAV. World J. Model. Simul. 2015, 11, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Özbek, E.; Yalin, G.; Ekici, S.; Karakoc, H.T. Evaluation of design methodology, limitations, and iterations of a hydrogen fuelled hybrid fuel cell mini UAV. Energy 2020, 213, 118757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider-Lyons, K.; Stroman, R.O.; Schuette, M.; Mackrell, J.; Page, G.; Rodgers, J.A. Hydrogen fule cell propulsion for long endurance small UVAs. In Proceedings of the AIAA Centennial of Naval Aviation Forum “100 Years of Achievement and Progress”, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 21–22 September 2011; p. 6975. [Google Scholar]

- Velev, O. Summary of fuel cell projects: AeroVironment 1997–2007. In National Hydrogen Association Fall 2007; Topical Forum Columbia: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, V.P. Military UAVs claiming the skies with fuel cell power. Fuel Cells Bull. 2007, 2007, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroman, R.; Kellogg, J.C.; Swider-Lyons, K. Testing of a PEM fuel cell system for small UAV propulsion. Power 2000, 60. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264543086_Testing_of_a_PEM_fuel_cell_system_for_small_UAV_propulsion (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Bradley, T.H.; Moffitt, B.A.; Mavris, D.N.; Parekh, D.E. Development and experimental characterization of a fuel cell powered aircraft. J. Power Sources 2007, 171, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, K.M.; Martin, C.A. Investigation of Potential Fuel Cell Use in Aircraft, Institute for Defense Analyses; Institute for Defense Analyses: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Kim, T.; Lee, K.; Kwon, S. Fuel cell system with sodium borohydride as hydrogen source for unmanned aerial vehicles. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 9069–9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.E.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, Y.; Shin, S.J.; Kim, D.M.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. Portable ammonia-borane based H2 power-pack for unmanned aerial vehicles. J. Power Sources 2014, 254, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, J.; Foch, R.J. Unmanned Aircraft Systems Innovation at the Naval Research Laboratory, Aerospace Research Central; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. NaBH4 (sodium borohydride) hydrogen generator with a volume-exchange fuel tank for small unmanned aerial vehicles powered by a PEM (proton exchange membrane) fuel cell. Energy 2014, 69, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H3 Dynamic. Dreaming Big the Future of Aviation is Hydrogen-Electric, Autonomous, and Digital. 2023. Available online: https://www.h3dynamics.com/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Dziwulski, E.; Ribeiro, W.F.; Basilio, F.L. Avançando Para o Azul: Viabilidade e Impactos Dos Aviões Zeroe da Airbus Movidos a Hidrogênio: Moving Towards the Blue: Feasibility and Impacts of Airbus Zeroe Hydrogen-Powered Aircraft. Rev. Bras. Aviação Civ. Ciências Aeronáuticas 2025, 5, 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, N.; Reddy, S.R.P.; RajaShekara, K.; Haran, K.S. Flying cars and eVTOLs—Technology advancements, powertrain architectures, and design. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 4105–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mus, J.; Mylle, S.; Schotte, S.; Fevery, S.; Latré, S.K.; Buysschaert, F. CFD Modelling and Simulation of PEMFCs in STAR-CCM+. In Proceedings of the 2022 11th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Application (ICRERA), Istanbul, Turkey, 18–21 September 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Scanff, R.; Cauville, B.; Néron, D.; Ladevèze, P. Reduced-order models for aeronautics based on the LATIN-PGD method within non-linear industrial Simcenter Samcef software. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciences (EUCASS-3AF 2022), Lille, France, 27 June–1 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K. Hydrogen: Coming to an aircraft near you. Aerosp. Am. 2022, 60, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Jausseme, C.; Huang, Z.; Yang, T. Hydrogen-Powered Aircraft: Hydrogen–electric hybrid propulsion for aviation. IEEE Electrif. Mag. 2022, 10, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.A. A recent overview of proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Fundamentals, applications, and advances. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 252, 123746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuster, P.; Alekseev, A.; Wasserscheid, P. Hydrogen storage technologies for future energy systems. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2017, 8, 445–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, X.; Liu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Nan, Z.; Teng, L.; Peng, W.; Bian, J. Safety of hydrogen storage and transportation: An overview on mechanisms, techniques, and challenges. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 6258–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.C.; Biga, R.; Kolisnichenko, A.; Marocco, P.; Monteverde, A.H.A.; Santarelli, M. Potential and technical challenges of on-board hydrogen storage technologies coupled with fuel cell systems for aircraft electrification. J. Power Sources 2023, 555, 232397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Xin, Y. A review of thermal management of proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2023, 15, 012703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Z.; Gao, Y. Design and optimization of thermal strategy to improve the thermal management of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 222, 119880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Zhang, X.; Yin, C.; Luo, Y.Q.; Tang, H. Improving a fuel cell system’s thermal management by optimizing thermal control with the particle swarm optimization algorithm and an artificial neural network. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Nik-Ghazali, N.-N.; Ali, M.A.H.; Chong, W.T.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H. A review on thermal management in proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Temperature distribution and control. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madheswaran, D.K.; Vengatesan, S.; Varuvel, E.G.; Praveenkumar, T.; Jegadheeswaran, S.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Arulmozhivarman, J. Nanofluids as a coolant for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells: Recent trends, challenges, and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 424, 138763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, C.; Lei, F. A Review of Thermal Management for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Power Systems. Automot. Dig. 2023, 15, 02-271. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dirkes, S.; Leidig, J.; Fisch, P.; Pischinger, S. Prescriptive Lifetime Management for PEM fuel cell systems in transportation applications, Part I: State of the art and conceptual design. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 277, 116598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimoto, Y.; Wulf, C.; Schonhoff, A.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Life cycle costing approaches of fuel cell and hydrogen systems: A literature review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Long, Y.; Fu, P.; Guo, C.; Tang, Y.; Huang, H. A novel multi-stack fuel cell hybrid system energy management strategy for improving the fuel cell durability of the hydrogen electric Multiple Units. Int. J. Green Energy 2024, 21, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, K.A.; Palaia, G.; Quarta, A.A. Review of hybrid-electric aircraft technologies and designs: Critical analysis and novel solutions. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2023, 141, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hince, S.B.; Ansell, P.J. Hybrid H2 Powertrain Characterization for Aircraft Design and Integration. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation Forum and Ascend 2024, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 July–2 August 2024; p. 3965. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D. Double-layer fuzzy adaptive NMPC coordinated control method of energy management and trajectory tracking for hybrid electric fixed wing UAVs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 39239–39254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 9, 413–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, T.L.; Pasupuleti, J.; Kiong, T.S.; Koh, S.P.J.; Yusaf, T. Energy management strategies, control systems, and artificial intelligence-based algorithms development for hydrogen fuel cell-powered vehicles: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 1380–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Cai, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, D.; Pan, Z.; Kang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Fabrication methods, structure design and durability analysis of advanced sealing materials in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 139995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, L.M.; Petrone, G.; De Rosa, S.; Franco, F.; Greco, C.S. Review of the recent developments about the hybrid propelled aircraft. Aerotec. Missili Spaz. 2024, 103, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, O.K.; Hakyemez, I.; Bagriyanik, M.; Kalenderli, O. A Study on Power System Retrofit for Cessna-172S Aircraft by Using Hydrogen Fuel Cell and Battery Hybrid. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 6089–6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, J. Unsettled Issues Concerning the Opportunities and Challenges of eVTOL Applications During a Global Pandemic; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020; Volume 2, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Farajijalal, M.; Eslamiat, H.; Avineni, V.; Hettel, E.; Lindsay, C. Safety Systems for Emergency Landing of Civilian Unmanned Aerial Vehicles—A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2025, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yao, Z. Recent development of fuel cell core components and key materials: A review. Energies 2023, 16, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Dawood, F.; Kaur, A.; Arif, M.T.; Pugazhendhi, R.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Ahmed, S.F. Fuelling the future: An in-depth review of recent trends, challenges and opportunities of hydrogen fuel cell for a sustainable hydrogen economy. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 2103–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | PEMFC (Air-Cooled) | PEMFC (Water-Cooled) | AFC | Hydrogen Turbine Generator | Hydrogen Piston Internal Combustion Engine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel | High-purity H2 | H2 (purity ≥ 99.97%) | Pure H2 + pure O2 | Hydrogen/kerosene blend | H2 (methane blending) |

| Electrolyte/Structure | Perfluorosulfonic acid membrane | Thin-layer Perfluorosulfonic acid membrane | 30% KOH solution | Combustion chamber + turbine assembly + generator | Internal combustion engine + generator |

| Operating Temperature | 45–75 °C | 60–85 °C | 60–120 °C | Turbine inlet temperature > 1000 °C | In-cylinder combustion temperature > 200 °C |

| Single Module Power Range | 0.3–5 kW | 5 kW–1 MW | 0.3–20 kW | 2–30 MW | 250–450 kW |

| Efficiency | 40–50% | 50–60% | 60–70% | 35–45% | 25–40% |

| Power Density | 0.5–1.0 kW/kg | 1.2–2.0 kW/kg | 0.3–0.8 kW/kg | 3–5 kW/kg | 0.8–1.5 kW/kg |

| Low-Temperature (−30 °C~−20 °C) Start-up Time | 30~60 s | 30 s~7 min | The electrolyte exhibits high activity at low temperatures. | Preheating time of 5–15 min is required. | A wide flammability limit facilitates cold-start times of less than 10 s. |

| Room-Temperature Start-up Time | <30 s | <30 s | <15 s | 2~5 min | <1 s |

| Fault Tolerance | Moderate (dependent on ambient temperature) | High (requires precise thermal management) | Very high (tolerant to impurities) | Low (requires flashback prevention) | Moderate (requires pre-ignition prevention) |

| References | [16,17,18] | [19,20] | [18,21,22] | [23,24,25] | [26,27] |

| Architecture | Multi-Rotor | Composite Wing | Tiltrotor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption characteristics of hydrogen-electric hybrid vehicles | The vertical takeoff and landing phase relies on multiple rotors working simultaneously, requiring high instantaneous power demand. Hydrogen fuel cells must work in conjunction with lithium batteries to provide peak power support. | Vertical takeoff and landing is powered by independent rotors, while cruise flight is driven by fixed wings and horizontal propellers, allowing hydrogen fuel cells to focus on supplying power during cruise flight. | Tilting rotors or wings require dynamic adjustment of power output direction, placing extremely high demands on fuel cell power density and dynamic response. |

| Supply side characteristics of hydrogen-electric hybrid power | Hydrogen fuel cells are mainly used to supplement range, with lithium batteries still being the primary source of power. | Focus on the synergy between hydrogen energy and batteries to balance load capacity and range. | High-energy-density liquid hydrogen storage systems and high-power fuel cells are required to meet the long-range requirements of the cruise phase. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Yue, H.; Zheng, H.; Tan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F. Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells for Aircraft Applications: A Comprehensive Review of Key Challenges and Development Trends. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040116

Zhang X, Yue H, Zheng H, Tan L, Zhang Z, Li F. Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells for Aircraft Applications: A Comprehensive Review of Key Challenges and Development Trends. Hydrogen. 2025; 6(4):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040116

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xinfeng, Han Yue, Hui Zheng, Lixing Tan, Zhiming Zhang, and Feng Li. 2025. "Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells for Aircraft Applications: A Comprehensive Review of Key Challenges and Development Trends" Hydrogen 6, no. 4: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040116

APA StyleZhang, X., Yue, H., Zheng, H., Tan, L., Zhang, Z., & Li, F. (2025). Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells for Aircraft Applications: A Comprehensive Review of Key Challenges and Development Trends. Hydrogen, 6(4), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040116