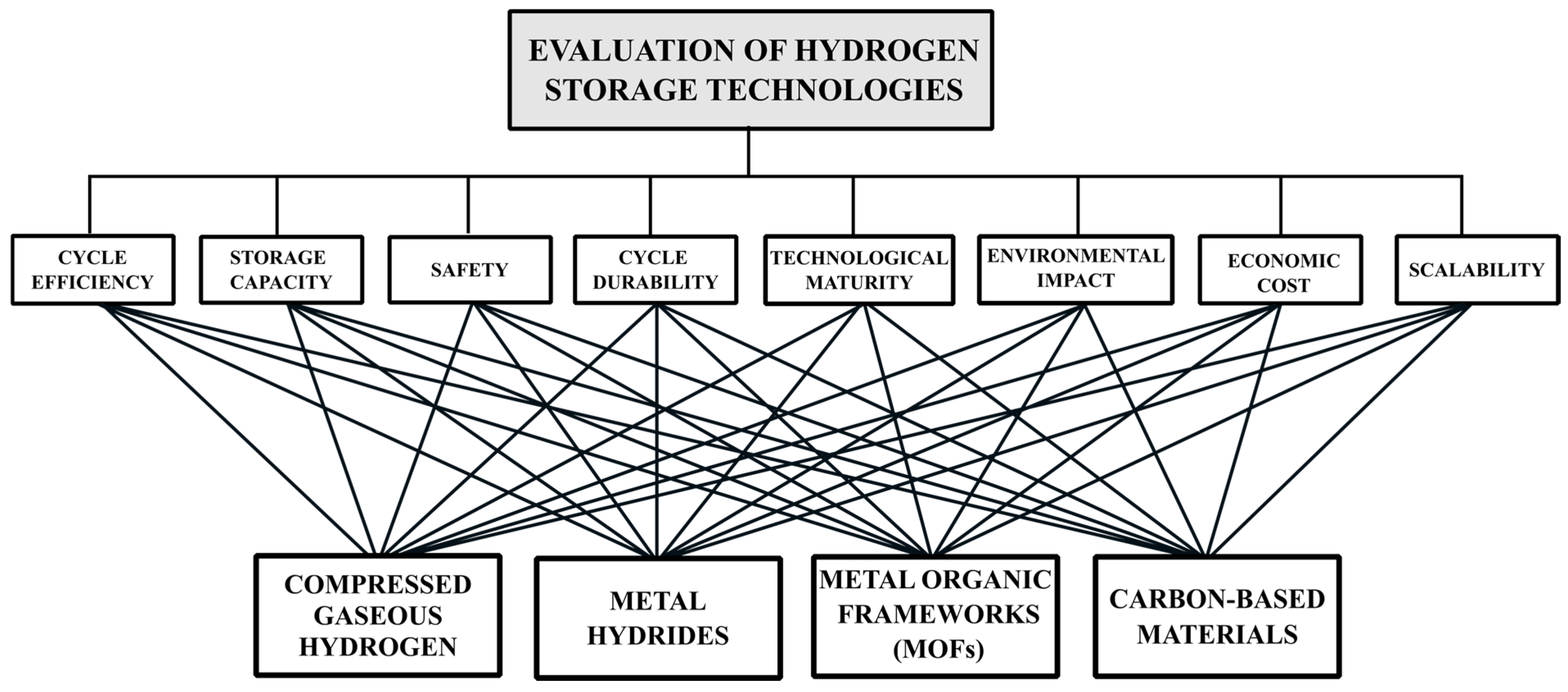

Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Hydrogen Storage Technologies Using AHP and TOPSIS Methodologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Selection of Alternatives

2.1. Compressed Gaseous Hydrogen

2.2. Metal Hydrides

2.3. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

2.4. Carbon-Based Materials

3. Selection of Criteria

3.1. Storage Capacity

3.2. Cycle Durability

3.3. Safety

3.4. Technological Maturity

3.5. Environmental Impact

3.6. Economic Cost

3.7. Cycle Efficiency

3.8. Scalability

3.9. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methodologies

3.9.1. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

3.9.2. Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS)

4. Results and Discussion

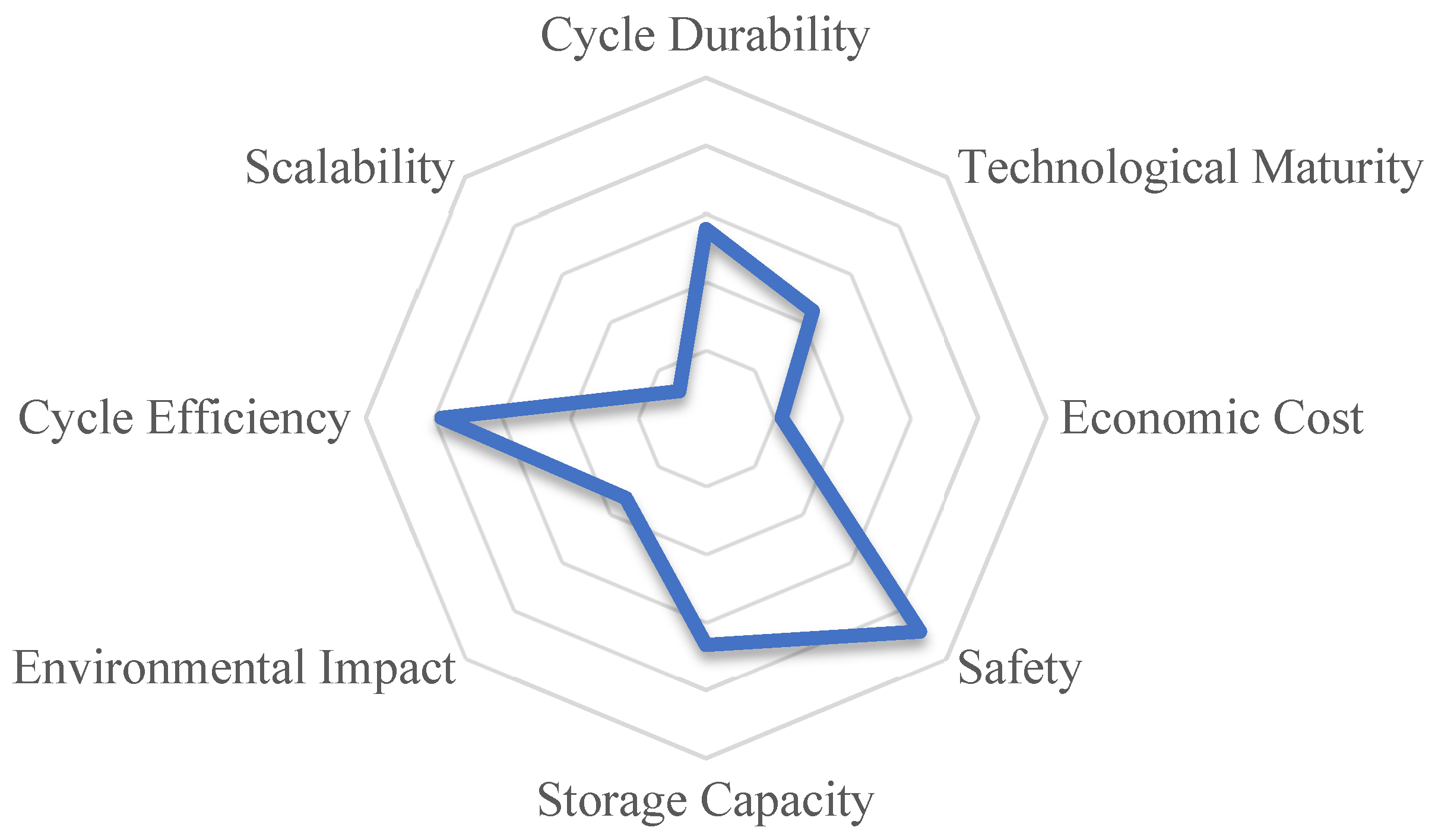

4.1. AHP

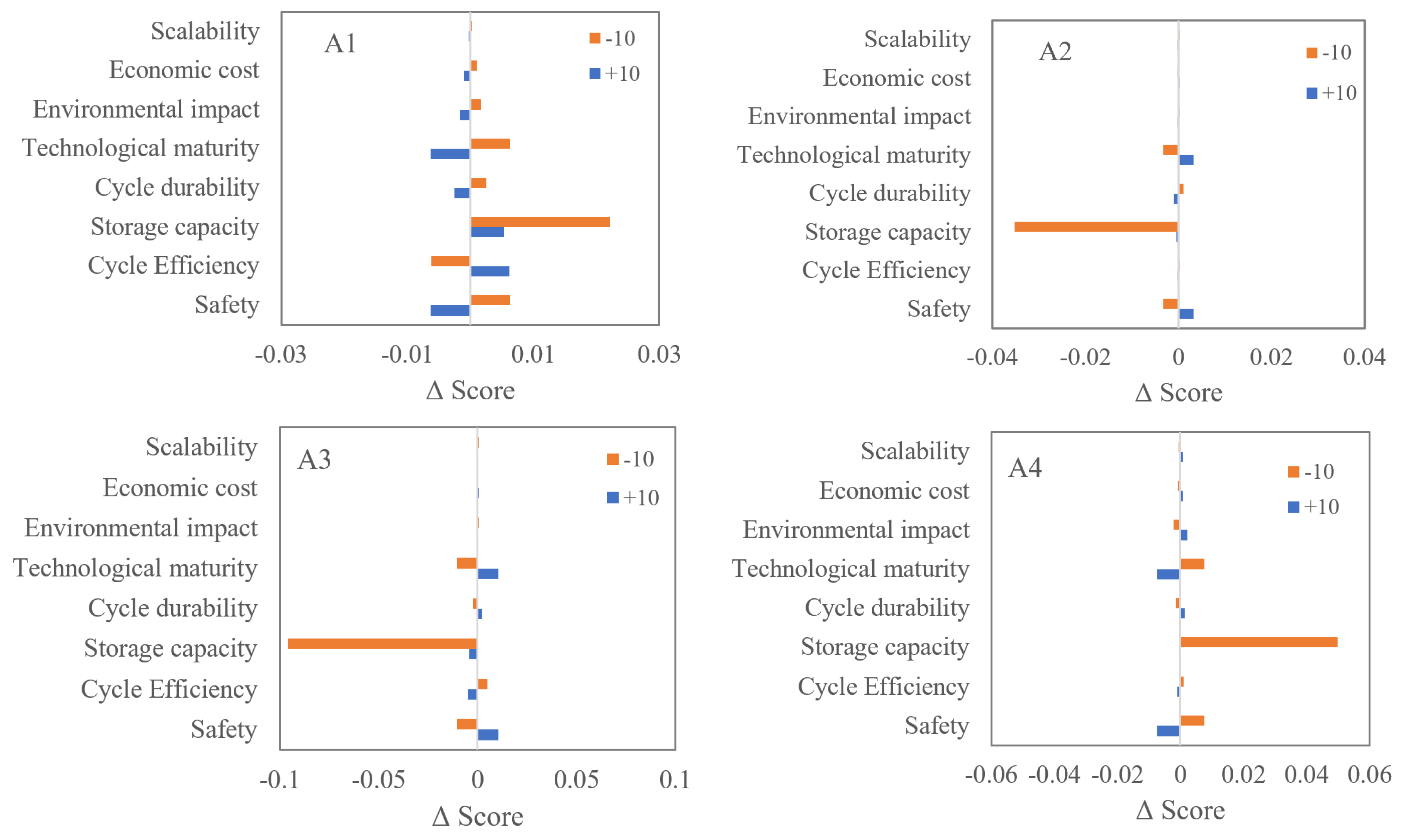

Sensitivity Analysis

4.2. TOPSIS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zainal, B.S.; Ker, P.J.; Mohamed, H.; Ong, H.C.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Nghiem, L.D.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Recent advancement and assessment of green hydrogen production technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado Molina, R.; Casteleiro Roca, J.L.; Jove Pérez, E.; Zayas Gato, F.; Quintián Pardo, H.; Calvo Rolle, J.L. Hidrógeno y su Almacenamiento: El Futuro de la Energía Eléctrica; Universidade da Coruña: A Coruña, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulky, L.; Srivastava, S.; Lakshmi, T.; Sandadi, E.R.; Gour, S.; Thomas, N.A.; Shanmuga Priya, S.; Sudhakar, K. An overview of hydrogen storage technologies—Key challenges and opportunities. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 325, 129710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, N.T.; Clarizia, L.; Ganguly, P. Advancing hydrogen storage: Critical insights to potentials, challenges, and pathways to sustainability. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2025, 48, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; D’Accadia, M.D.; Santarelli, M.; Lanzini, A.; Ferrero, D. Solar Hydrogen Production: Processes, Systems and Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Yang, H.; Tong, L.; Wang, L. Research progress of cryogenic materials for storage and transportation of liquid hydrogen. Metals 2021, 11, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Nasr, M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Hosny, M.; Farghali, M.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Rooney, D.W.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M. Advances in hydrogen storage materials: Harnessing innovative technology, from machine learning to computational chemistry, for energy storage solutions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 67, 1270–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malleswararao, K.; Dutta, P.; Murthy, S.S. Applications of metal hydride based thermal systems: A review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 215, 118816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oner, O.; Khalilpour, K. Evaluation of green hydrogen carriers: A multi-criteria decision analysis tool. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rizeiqi, N.; Azzouz, A.; Liew, P.Y. Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Large-Scale Hydrogen Storage Technologies in Oman using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 106, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilavachi, P.A.; Chatzipanagi, A.I.; Spyropoulou, A.I. Evaluation of hydrogen production methods using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 5294–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, B.; Taiwo, M.; Syidanova, A.; Uzun Ozsahin, D. The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS). In Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in Environmental and Civil Engineering; Professional Practice in Earth Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, B.; Kim, J.W. Multi-criteria evaluation of hydrogen storage systems for automobiles in Korea using the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 7852–7858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, X.; Zhang, R.; Hu, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, X. A multi-criteria decision-making approach for energy storage technology selection based on demand. Energies 2021, 14, 6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, I.M. A new approach for spherical fuzzy TOPSIS and spherical fuzzy VIKOR applied to the evaluation of hydrogen storage systems. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 4403–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haktanır, E.; Kahraman, C. Integrated AHP & TOPSIS methodology using intuitionistic Z-numbers: An application on hydrogen storage technology selection. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 239, 122382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, C.; Haktanır, E.; Tekin Temur, G.; Beskese, A. Sustainable stationary hydrogen storage application selection with interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy AHP. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inal, O.B.; Dere, C.; Deniz, C. Onboard Hydrogen Storage for Ships: An Overview. In Proceedings of the 5th International Hydrogen Technologies Congress, Niğde, Turkey, 26–28 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alobaid, A.; Kamil, M.; Abdelrazek Khalil, K. Metal hydrides for solid hydrogen storage: Experimental insights, suitability evaluation, and innovative technical considerations for stationary and mobile applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 128, 432–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talagañis, B.A.; Meyer, G.O.; Aguirre, P.A. Modeling and simulation of absorption-desorption cyclic processes for hydrogen storage-compression using metal hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 13621–13631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopčič, N.; Grimmer, I.; Winkler, F.; Sartory, M.; Trattner, A. A review on metal hydride materials for hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Ayati, A.; Farrokhi, M.; Khadempir, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Farghali, M.; Krivoshapkin, P.; Tanhaei, B.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.S. Innovations in hydrogen storage materials: Synthesis, applications, and prospects. J. Energy Storage 2024, 95, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariharan, A.; Viswanathan, B.; Nandhakumar, V. Nitrogen-incorporated carbon nanotube derived from polystyrene and polypyrrole as hydrogen storage material. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 5077–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdanghi, G.; Canevesi, R.L.S.; Celzard, A.; Thommes, M.; Fierro, V. Characterization of Carbon Materials for Hydrogen Storage and Compression. C 2020, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskan, S.N.; Abdulkadir, B.A.; Setiabudi, H.D. Materials on the frontier: A review on groundbreaking solutions for hydrogen storage applications. Chem. Phys. Impact 2025, 10, 100862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Xu, H.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.Q. A review on the research progress and application of compressed hydrogen in the marine hydrogen fuel cell power system. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnin, A.S.; Wacławiak, K.; Humayun, M.; Zhang, S.; Ullah, H. Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elberry, A.M.; Thakur, J.; Santasalo-Aarnio, A.; Larmi, M. Large-scale compressed hydrogen storage as part of renewable electricity storage systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 15671–15690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, B.J.; Gamble, S.N. Material analysis of metal hydrides for bulk hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 62, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, L.A.M.; Rowlandson, J.L.; Fermin, D.J.; Ting, V.P.; Nayak, S. Porous carbons: A class of nanomaterials for efficient adsorption-based hydrogen storage. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2025, 2, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enasel, E.; Dumitrascu, G. Storage solutions for renewable energy: A review. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, P.; Liu, N.; Wang, L.; Yue, B.; Liu, Y. Review on reliability assessment of energy storage systems. IET Smart Grid 2024, 7, 695–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züttel, A. Materials for hydrogen storage. Mater. Today 2003, 6, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memetova, A.; Tyagi, I.; Karri, R.R.; Kumar, V.; Tyagi, K.; Suhas; Memetov, N.; Zelenin, A.; Pasko, T.; Gerasimova, A.; et al. Porous carbon-based material as a sustainable alternative for the storage of natural gas (methane) and biogas (biomethane): A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Oko, E.; Kuang, B.; Bello, A.; Onwualu, A.P.; Oyagha, S.; Whidborne, J. The prospects of hydrogen in achieving net zero emissions by 2050: A critical review. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2023, 2, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Jin, Q.; Su, G.; Lu, W. A Review of Hydrogen Storage and Transportation: Progresses and Challenges. Energies 2024, 17, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannenberg, L.J.; Heere, M.; Benzidi, H.; Montero, J.; Dematteis, E.M.; Suwarno, S.; Jaroń, T.; Winny, M.; Orłowski, P.A.; Wegner, W.; et al. Metal (boro-) hydrides for high energy density storage and relevant emerging technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 33687–33730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.L.; Mardel, J.I.; Hill, M.R. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) as Hydrogen Storage Materials at Near-Ambient Temperature. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Z. Advanced Carbon Architectures for Hydrogen Storage: From Synthesis to Performance Enhancement. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavankar, S.; Suh, S.; Keller, A.A. The Role of Scale and Technology Maturity in Life Cycle Assessment of Emerging Technologies: A Case Study on Carbon Nanotubes. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohra Zeggai, F.; Ait-Touchente, Z.; Bachari, K.; Elaissari, A. Investigation of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Synthesis, Properties, and Applications—An In-Depth Review. Chem. Phys. Impact 2025, 10, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakoulaki, D.; Karangelis, F. Multi-criteria decision analysis and cost–benefit analysis of alternative scenarios for the power generation sector in Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shu, X.; Zhang, G.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Wu, P.; Ding, Z. Rare-Earth Metal-Based Materials for Hydrogen Storage: Progress, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, K.P.; Vo, D.V.N.; Gnana Prakash, D.; Adithya Joseph, A.; Viswanathan, S.; Arun, J. Environmental applications of carbon-based materials: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi Avargani, V.; Zendehboudi, S.; Duan, X.; Abdlla Maarof, H. Advancements in non-renewable and hybrid hydrogen production: Technological innovations for efficiency and carbon reduction. Fuel 2025, 395, 135065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.; Ciraolo, L. A multicriteria approach to evaluate wind energy plants on an Italian island. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, S.; McCay, M.H. Different reactor and heat exchanger configurations for metal hydride hydrogen storage systems—A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 9462–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Yurdusen, A.; Mouchaham, G.; Nouar, F.; Serre, C. Large-Scale Production of Metal–Organic Frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 34, 2309089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, K.; Panwar, N.L.; Lanjekar, P.R. Emergence of carbonaceous material for hydrogen storage: An overview. Clean. Energy 2024, 8, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Li, J.C.; Park, K.; Jang, S.J.; Kwon, J.T. An analysis on the compressed hydrogen storage system for the fast-filling process of hydrogen gas at the pressure of 82 mpa. Energies 2021, 14, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkapalli, V.K.; Kim, S.; Thomas, S.A. Thermal Management Techniques in Metal Hydrides for Hydrogen Storage Applications: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Giovannini, C. Hydrogen Gas Compression for Efficient Storage: Balancing Energy and Increasing Density. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, Z.A.; Raza, M.A.; Awwad, N.S.; Ibrahium, H.A.; Farwa, U.; Ashraf, S.; Dildar, A.; Fatima, E.; Ashraf, S.; Ali, F. Metal-organic frameworks for next-generation energy storage devices; a systematic review. Mater. Adv. 2023, 5, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Deshmukh, R.G.; Khalid, H.M.; Said, Z.; Raza, A.; Muyeen, S.M.; Nizami, A.S.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Saidur, R.; Sopian, K. Energy storage technologies: An integrated survey of developments, global economical/environmental effects, optimal scheduling model, and sustainable adaption policies. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhumal, P.; Bhadane, P.; Ibrahim, B.; Chakraborty, S. Evaluating the path to sustainability: SWOT analysis of safe and sustainable by design approaches for metal–organic frameworks. Green. Chem. 2025, 27, 3815–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawiah, B.; Ofori, E.A.; Chen, D.; Ming, Y.; Hou, Y.; Jia, H.; Fei, B. Carbon-Based Thermal Management Solutions and Innovations for Improved Battery Safety: A Review. Batteries 2025, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangon, J.; Darekar, A. Advancements in hydrogen energy systems: A review of levelized costs, financial incentives and technological innovations. Innov. Green. Dev. 2024, 3, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Pamucar, D.; Goswami, S.S. A Review of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Applications to Solve Energy Management Problems From 2010-2025: Current State and Future Research. Spectr. Decis. Mak. Appl. 2025, 2, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha Aljburi, M.; Albahri, A.S.; Albahri, O.S.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Mahdi Mohammed, S.; Deveci, M.; Tomášková, H. Exploring decision-making techniques for evaluation and benchmarking of energy system integration frameworks for achieving a sustainable energy future. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 51, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosouli, S.; Hassani, R.A. Application of multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) model for solar plant location selection. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohekar, S.D.; Ramachandran, M. Application of multi-criteria decision making to sustainable energy planning—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2004, 8, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z. A review of thermal coupling system of fuel cell-metal hydride tank: Classification, control strategies, and prospect in distributed energy system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, R.W. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation (Decision Making Series). In Mathematical Modelling; McGraw-Hill International Book Co.: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Nantes, E.A. El método Analytic Hierarchy Process par la toma de decisiones. Repaso de la metodología y aplicaciones. In Investigación Operativa; Universidad Nacional del Sur: Bahía Blanca, Argentina, 2019; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.-L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attributes Decision Making Methods and Applications, Multiple Attribute Decision Making; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, E.; Fathi, M.R.; Sobhani, S.M. A Modification of Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) through Fuzzy Similarity Method (A Numerical Example of the Personnel Selection). J. Appl. Res. Ind. Eng. 2023, 10, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, J.; Tang, G.; Sun, T.; Jia, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, L.; Xu, W. Evaluating the Application Potential of Acid-Modified Cotton Straw Biochars in Alkaline Soils Based on Entropy Weight TOPSIS. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulewicz, R.; Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A. Sustainable Vehicle Design Considering Quality Level and Life Cycle Environmental Assessment (LCA). Energies 2023, 16, 8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ccatamayo-Barrios, J.H.; Huamán-Romaní, Y.L.; Seminario-Morales, M.V.; Flores-Castillo, M.M.; Gutiérrez-Gómez, E.; Carrillo-De la Cruz, L.K.; de la Cruz-Girón, K.A. Comparative Analysis of AHP and TOPSIS Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods for Mining Method Selection. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 2023, 10, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xue, X.; Lin, Q. Metal-Organic Frameworks Promoted Hydrogen Storage Properties of Magnesium Hydride for In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) on Mars. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 766288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Compressed Hydrogen | Metal Hydrides | MOFs | Carbon-Based Materials | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Safety | L | M | M | H |

| C2 | Cycle Efficiency | M | H | M | L |

| C3 | Storage Capacity | M | H | M | L |

| C4 | Cycle Durability | M | M | L | H |

| C5 | Technological Maturity | H | M | L | M |

| C6 | Environmental Impact | D | M-H | H | M |

| C7 | Economic Cost | M | H | H | H |

| C8 | Scalability | M | L | L | L |

| Criterion | Weight | |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Safety | 0.222 |

| C2 | Cycle Efficiency | 0.194 |

| C3 | Storage Capacity | 0.167 |

| C4 | Cycle Durability | 0.139 |

| C5 | Technological Maturity | 0.110 |

| C6 | Environmental Impact | 0.083 |

| C7 | Economic Cost | 0.056 |

| C8 | Scalability | 0.028 |

| Criteria | A | cij | wi | CR | RI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.049 | 5.5 | |||

| C2 | 0.039 | 4.3 | |||

| C3 | 0.060 | 6.7 | |||

| C4 | 0.014 | 1.6 | |||

| C5 | 0.042 | 4.7 | |||

| C6 | 0.07 | 0.8 | |||

| C7 | 0.003 | 0.4 | |||

| C8 | 0.017 | 1.9 |

| Alternative | Final AHP Score | Ranking | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Metal hydrides | 0.313 | 1 |

| A2 | Metal–organic frameworks | 0.125 | 4 |

| A3 | Carbon materials | 0.255 | 3 |

| A4 | Compressed hydrogen | 0.307 | 2 |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.076 | 0.149 | 0.124 | 0.060 | 0.071 | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.014 |

| A2 | 0.114 | 0.064 | 0.055 | 0.036 | 0.009 | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.007 |

| A3 | 0.171 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.085 | 0.027 | 0.041 | 0.029 | 0.010 |

| A4 | 0.038 | 0.106 | 0.096 | 0.085 | 0.080 | 0.057 | 0.036 | 0.021 |

| PIS | 0.171 | 0.149 | 0.124 | 0.085 | 0.080 | 0.057 | 0.036 | 0.021 |

| NIS | 0.038 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.036 | 0.009 | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.007 |

| Alternative | Ci | Ranking | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Metal Hydrides | 0.103 | 0.185 | 0.643 | 1 |

| A2 | Metal–organic frameworks | 0.154 | 0.096 | 0.385 | 4 |

| A3 | Carbon Materials | 0.178 | 0.143 | 0.446 | 3 |

| A4 | Compressed Hydrogen | 0.142 | 0.150 | 0.513 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maceiras, R.; Alfonsin, V.; Feijoo, J.; Perez-Rial, L.; Lopez-Granados, A. Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Hydrogen Storage Technologies Using AHP and TOPSIS Methodologies. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040111

Maceiras R, Alfonsin V, Feijoo J, Perez-Rial L, Lopez-Granados A. Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Hydrogen Storage Technologies Using AHP and TOPSIS Methodologies. Hydrogen. 2025; 6(4):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040111

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaceiras, Rocio, Victor Alfonsin, Jorge Feijoo, Leticia Perez-Rial, and Adrian Lopez-Granados. 2025. "Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Hydrogen Storage Technologies Using AHP and TOPSIS Methodologies" Hydrogen 6, no. 4: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040111

APA StyleMaceiras, R., Alfonsin, V., Feijoo, J., Perez-Rial, L., & Lopez-Granados, A. (2025). Multi-Criteria Evaluation of Hydrogen Storage Technologies Using AHP and TOPSIS Methodologies. Hydrogen, 6(4), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040111