Abstract

Worldwide, large volumes of industrial residues, such as water treatment sludge (WTS), biomass ash (BA), iron slag (IS), and quarry fines (QF), are generated with limited reuse. This study evaluates their potential as additives for two soils, using two types of soils as matrices. A comprehensive laboratory program (particle size distribution, Proctor compaction, Atterberg limits, falling-head permeability, oedometer consolidation, consolidated undrained triaxial tests, and scanning electron microscopy) was performed on soil–residue mixtures across practical dosages. Optimal mixes balanced strength and transport properties: 15% WTS lowered hydraulic conductivity (k) into the 10−9 m/s range while reducing plasticity; 20% BA rendered the soil non-plastic but increased k into the 10−8–10−7 m/s range; 50% IS increased friction angle while maintaining k ~10−8 m/s; and QF produced modest changes while preserving k ~10−9 m/s. These findings support the sustainable reuse of these industrial wastes for soft soil stabilization, also contributing to the circular economy in the industrial and construction sectors, and are aligned with the United Nations’ sustainable development goals 6, 9, 11, 12, and 15.

1. Introduction

Waste disposal has been a major worldwide concern due to the potential contamination of water, soil, and the atmosphere. Although several policies are currently in place in many countries, ref. [1] points out that these investments and treatment policies have not kept pace with the increasing population, particularly in developing countries, causing socio-economic impacts. Residues are usually disposed of in landfills, consuming significant land areas. Additionally, not reusing waste implies the continued exploration of raw and natural materials that do not return to nature, thus depleting non-renewable resources. Given current demands for a greener future, research and development have been directed towards the valorization and reuse of industrial waste. Construction activities consume 32% of the world’s resources, including 12% of water, 40% of energy, and 40% of all raw materials extracted from the earth [2], and are responsible for 25% of solid waste generated in the world [3]. This data highlights the necessity of developing new methods for the reuse of industrial waste in this sector, which already employs construction debris.

Soft soils are known to have undesirable characteristics for geotechnical designs, including low shear strength, high compressibility associated with considerable settlements, and high water absorption–retention capacity. Commonly used stabilization techniques include employing geosynthetics, column grouting, and rigid inclusions [4]. These methods, though effective, may be high-cost and not sustainable due to the emissions associated with the production of synthetic and manufactured materials. Thus, waste materials emerge as potential additives to enhance soil properties. On the other hand, waste materials can be added to soils with good geotechnical behavior to provide a beneficial destination for the residues. In this case, waste addition should be as high as possible without impairing the soil properties. Key sectors around the world, such as water treatment, energy production, metallurgical industry, and stone quarrying activities, produce by-products that are largely available and are currently being investigated for varied applications.

Water treatment sludge (WTS) is a by-product of water treatment, generated during the sedimentation and filtration stages. It is mainly composed of water and mineral and organic solids that were suspended in the raw water, accumulated during seepage through the ground [5]. WTS composition varies based on the raw water composition and treatment processes in the Water Treatment Plant (WTP), and is generally rich in silicium, aluminum, calcium, and iron [6,7]. Although each WTS batch differs, several studies have shown the feasibility of the geotechnical applications of various types of WTS [6,8,9,10].

Biomass ash (BA) is generated mainly in thermoelectric facilities for energy production. BA results from the incineration of leaves, wood, and other organic materials, often associated with coal co-combustion [11]. Different types of biomass ashes, including bottom, filter, and fly ashes, are classified based on their granulometry and production temperature, which affect their structure and mineralogy [12]. As noted by Studart et al. (2022) [13] and Studart et al. (2024) [14], the by-product differs significantly from the original biomass, making it difficult to trace exact transformation patterns. Research has shown that biomass ashes can improve soil properties, reduce plasticity, and enhance mechanical resistance [15,16]. They are generally light, fine materials with high silica content, which seem to boost soils with low mechanical properties and high plasticity, although their leachability must be evaluated due to the potential presence of heavy metals.

Quarry fines (QF) are a residue produced in large quantities worldwide, up to 25 billion tons per year [17], and are mainly composed of water, the mined mineral, and accessory products used in beneficiation and extraction [18]. Quarry fines and tailings are normally disposed of in storage dams, which may pose significant environmental risks if not properly managed, generating large amounts of waste [2]. Studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using some types of QF to stabilize weak soils [19,20], since they exhibited high friction angles and low cohesion, behaving like a granular material.

Iron slag (IS) is a residue with some economic value due to its high iron content. Iron is one of the most abundant ores globally and has numerous applications [21]. It is predominantly generated in the metallurgical industries during steel-making processes. The residue is a dense, iron-based material with a complex and varied structure and granular granulometry [22,23]. Its generation is large-scale worldwide, even in highly developed countries [24]: in the US, production reaches up to 20 million tons annually, and 40 million tons in Japan [23].

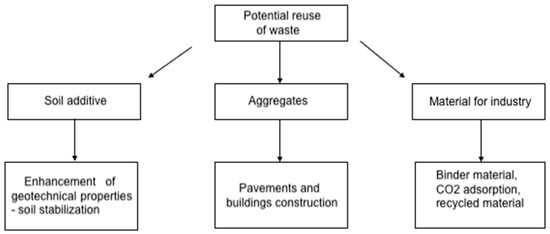

Figure 1 summarizes the potential of reusing wastes in geotechnical applications within the scope of the circular economy.

Figure 1.

Possible reuse of industrial wastes.

Most prior studies assess single waste streams under non-uniform test conditions, offering limited comparability [10,15,17,25], while mechanistic links between particle-scale traits (e.g., specific surface area, morphology, and mineralogy) and macro responses (e.g., permeability, plasticity, shear strength, and compressibility) remain underexplored [26,27,28,29]. Systematic dosage optimization across soil types and compaction/moisture/stress paths is rare [16,30]. Environmental safety and durability (e.g., leaching, pH evolution, and microstructural stability) are often outside scope, despite recurring concerns in the slag/ash literature [8,17,23], leaving the field without a generalizable, decision-oriented framework for selecting and designing waste-amended soils.

This research evaluates four industrial by-products in parallel for the stabilization of two soils, all materials originating from a determined geographical region. It supports the following sustainable development goals (SDGs) of the UN: SDG 6 (Clean water and sanitation), SDG 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure), SDG 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production), and SDG 15 (Life on land). The approach of selecting readily available types of waste and providing a comprehensive geomechanical assessment of waste addition to local soils to support decisions on sustainable infrastructure construction is the novel contribution of this paper.

This investigation is part of ongoing research aimed at evaluating the potential of the reuse of these residues in geotechnical earthworks. The goal of this research is to assess the geomechanical properties of four residues (WTS, BA, IS, and QF) and of mixtures composed of these wastes and two soils. The tested percentages were 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% for WTS and BA, and 25% and 50% for IS and QF.

The evaluated geomechanical characteristics and properties included granulometry, Atterberg limits, specific gravity of the solids, standard Proctor compaction, permeability, compressibility in oedometric consolidation tests, and shear strength evaluated by consolidated undrained (CU) triaxial shear tests; additionally, mineralogic composition and microscopic structure were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2. Materials and Methods

The investigated soil, derived from granitic schists typical of Castelo Branco in Central Portugal, was collected during the excavation of a construction site. Due to changes in the residual soil with depth, the collected samples were classified as two distinct soils. Soil O2 was excavated from the upper 5 m thick layer and Soil CB is a mixture of soil excavated from 5 to 25 m depth in a different location in the same construction site. Both soils derive from schists, which occur widely around the world and specifically in Portugal, in the Trás-os-Montes and Beiras regions, associated with regional metamorphisms and tectonism activity. Different formation and weathering processes can produce soils with different mechanical and chemical properties and impact anisotropy [31]. The Castelo Branco region is mainly constituted by metamorphic rocks containing quartz; usual clay minerals associated with this type of formation are kaolinite and illite [32].

These soils have been used for landfilling, as subbase in pavements, and as fill material for trenches, among others. In this research, geotechnical tests were carried out to study whether residues may be incorporated without worsening the soils’ properties. The criterium for selecting the optimal mixture for each waste type is achieving the highest possible mass of added waste without impairing the good geotechnical qualities of the natural soils.

The residues BA and QF were retrieved from local companies in Castelo Branco, a thermoelectric plant and a quarry, respectively. IS was collected from a metallurgical company in Lisbon, and the WTS was obtained from a WTP in Guarda, all located in Portugal. The residues and mixtures were oven-dried at 60–65 °C for 24 h prior to the geotechnical tests.

Soil O2 was mixed with WTS, whereas soil CB received the addition of QF, BA, and IS (separately). The percentages (on dry mass) were based on published research to provide a comparative background [8,14,25,29,30]. Intervals of 5% increments were employed for WTS and CB, as initial assessments indicated that even minor changes in waste content resulted in significant alterations in the mixture consistency. Conversely, mixtures were not sensitive to varying QF and IS contents; therefore, only two levels were examined. The investigated mixtures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mixtures compositions.

The analysis of the mechanical properties of WTS and BA was based on a previously published work [33], while for the remaining materials the following parameters were determined: particle size distribution (from 4 mm to 0.075 mm), specific gravity of the solids (GS), liquid limit (wL), plastic limit (wP), plasticity index (PI), and optimum water content (wopt) and maximum dry density (ρd, max) under Proctor compaction energy. The following standards were used: ISO 17892-Part 1 (2014) [34], ISO 17892-Part 2 (2014) [35], ISO 17892-Part 4 (2016) [36] and ISO 17892-Part 12 (2018) [37].

Confined compression tests were conducted with specimens compacted at the optimum water content and maximum dry density determined under normal Proctor energy. The tests were performed using an automatic LCR transducer strain gauge, with an MPE featuring a maximum strain of 25.8 mm and a precision of 0.001 mm, connected to an MPX3000 data logger produced by VJ Technology (Mira-Bhayandar, India). A logarithmic time scale was used with a load scale of 1-30-150-300-600-1200 k kPa and an unload scale of 1200-300-1 kPa.

The falling-head permeability tests were performed in duplicate for each material, with hydraulic gradients (i) of 50 and 100, according to ISO 17892-Part 11 (2019) [38]. Three consolidated undrained (CU) triaxial compression tests were conducted for each material with confining pressures of 100, 200, and 300 kPa up to 22% axial strain in a GDSLab equipment (GDS Instruments, Hook, UK). Saturation was considered complete when the B-parameter reached 0.95. Free expansibility tests were performed based on D4829-19 (ASTM, 2021) [39].

SEM images were obtained by using a TESCAN VEGA equipment (TESCAN ORSAY HOLDING, Brno, Czech Republic) with a 2 k× to 5 k× magnification. Samples were then passed through a #200-mesh sieve, air-dried, and covered in gold.

The specific surface (relation between the surface area of a material divided by the volume of that same material) was calculated according to Equation (1) [40].

where

- SS: specific surface (cm2/kg)

- Vi: relative volume by particle size class di (cm2)

- Gs: density of the material (kg/cm3).

- D50: mean diameter of particle distribution (mm).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification and Physical Characteristics

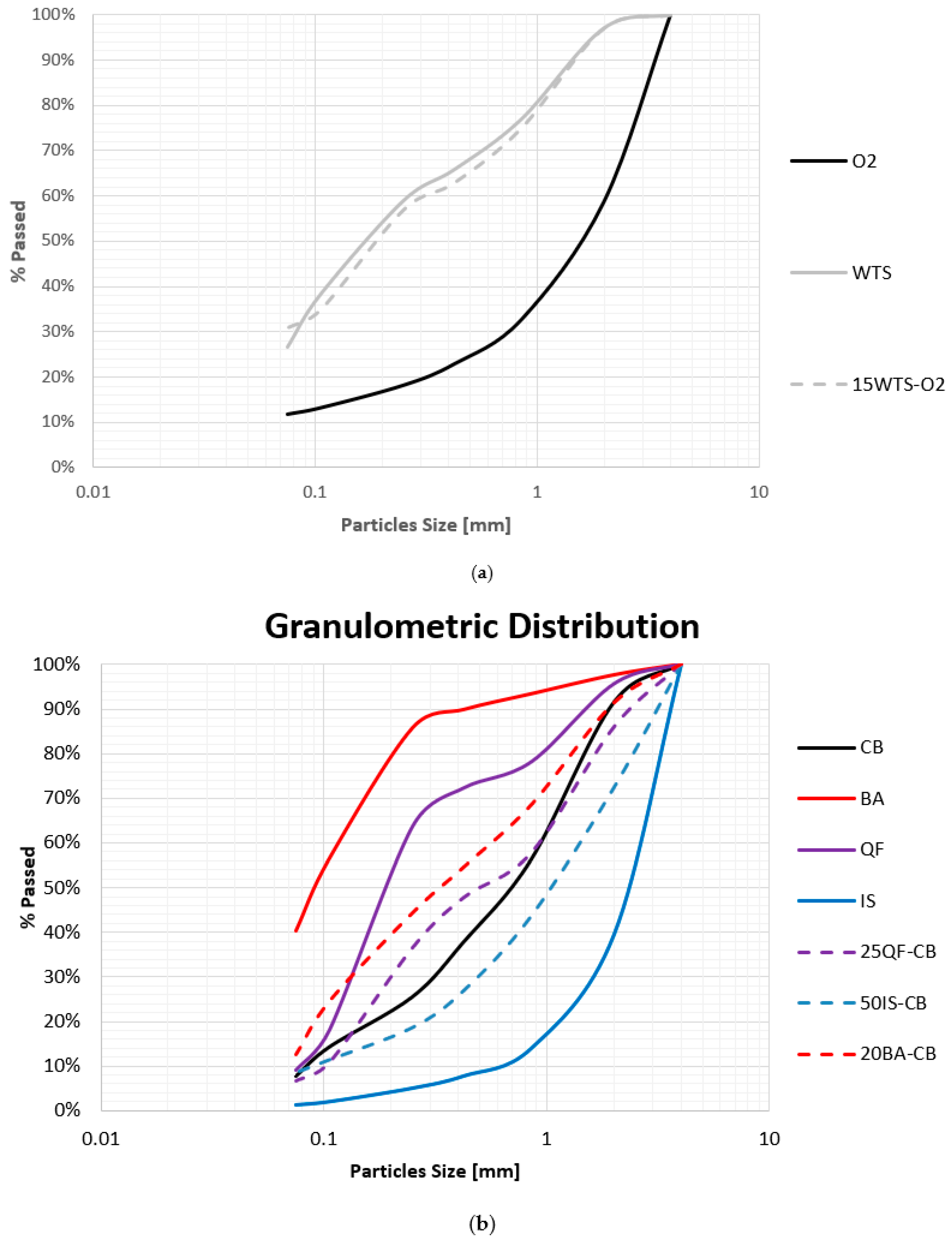

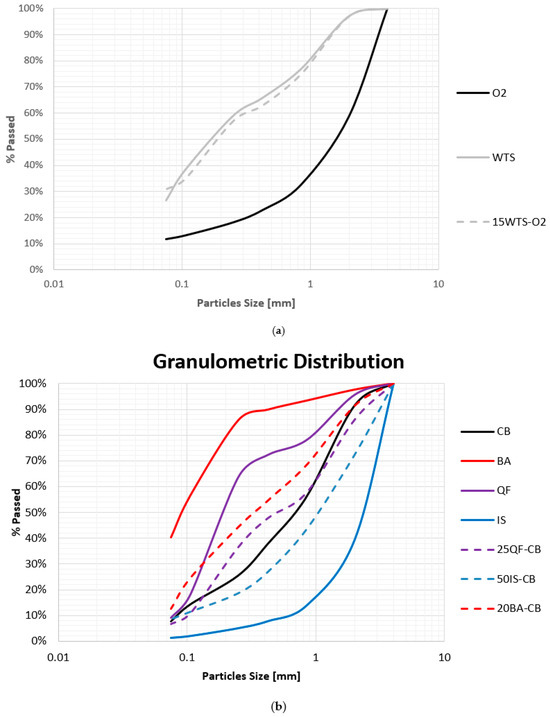

Figure 2 and Table 2 provide key insights into the particle size distribution of the natural soils and residues used in this study. The natural soils, Soil O2 and Soil CB, display distinct grading characteristics. Soil O2 is identified as a poorly graded sand with 12% non-plastic fines, while Soil CB is a well-graded sand with only 8% plastic fines. These differences directly influence their mechanical properties, such as permeability, compressibility, and shear strength. Granulometry analysis is usually the first step to evaluate the potential reuse of residues in geotechnical design [6,8,33,41].

Figure 2.

Granulometric distribution of analyzed materials: (a) Soil O2, WTS, and 15WTS-O2 mixture; (b) Soil CB, BA, IS, QF, and mixtures 20BA-CB, 50IS-CB, and 15QF-CB.

Table 2.

Characterization parameters.

The residues WTS and BA are finer than the natural soils, as evidenced by their lower D50 values (0.17 mm and 0.09 mm, respectively) and significantly higher specific surface areas (SS) (18.161 m2/kg and 28.761 m2/kg, respectively). Such an increase in SS typically enhances water absorption and can modify the plasticity of the soil by increasing cohesion among particles, although the fines may remain inert (Pennell, 2018 [27]). In contrast, IS presents a much coarser distribution, with a D50 of 2.27 mm and an SS of only 0.742 m2/kg. The coarser granulometry indicates that incorporating IS into soil CB enhances the GS and results in a denser, more granular soil structure. QF falls between these extremes, being a poorly graded clayey sand with 12% fines and a moderate SS of 11.961 m2/kg.

The granulometric curves in Figure 2 illustrate that the addition of finer residues (WTS and BA) shifts the overall particle size distribution of the mixtures towards smaller diameters. For example, the 15WTS-O2 mixture exhibits a lower D50 and a substantially increased SS compared to the natural soil O2. This finer matrix leads to a reduction in permeability, as the finer particles fill the voids between the larger soil grains. The measured permeability of soil O2 decreased by approximately 80% (from 5 × 10−10 m/s to 1 × 10−10 m/s) when the WTS content reached 10% or higher, which is consistent with the notion that a larger volume of very fine pores tends to lower overall permeability [26]. Conversely, when coarser materials such as IS are incorporated into soil CB, the overall structure becomes more granular.

The 50IS-CB mixture exhibits an increased GS and D50 and a reduced SS, which in turn increases permeability by approximately 150% (from 4 × 10−10 to 2 × 10−9 m/s) compared to CB.

Overall, the results indicate that the particle size distribution significantly affects the geomechanical properties of soil–residue mixtures. The addition of fine residues like WTS reduces permeability, even allowing, in the case of WTS, the use of these mixtures in the construction of bottom liners for waste disposal sites. In contrast, the use of coarser residues such as IS tends to increase permeability, which may be advantageous in certain applications. These findings are in line with previous studies that have emphasized the influence of granulometry in soil behavior [26,27,28]. However, granulometry is not the only intervening factor in permeability; the fine residue BA, for example, increased the permeability of soil CB up to 10−8 m/s. This suggests that CB created a more open pore network that facilitates drainage, a desirable characteristic for applications such as pavement foundations, where high permeability is required.

Table 3 shows the main results for plasticity and compaction parameters. Looking at Table 2 and Table 3, it can be noted that soil O2 has GS = 2.77, PI = 6%, and SS = 2.407 m2/kg. WTS, on the other hand, has GS = 1.95 and is not plastic, despite its high SS = 18.100 m2/kg. As WTS is added to soil O2, GS decreases, SS increases, and PI decreases. In the mixture with the highest WTS content (20%), PI = 1%, SS = 4.687% m2/kg (practically twice that of the natural soil), and GS = 2.56. The permeability coefficient, 5 × 10−10 m/s, decreases to 3 × 10−10 m/s with 5% WTS e 1 × 10−10 m/s for WTS contents equal to or higher than 10%.

Table 3.

Plasticity and compaction parameters.

Soil CB has GS = 2.70, PI = 8%, and SS = 3.175 m2/kg. BA, QF, and IS have GS equal to 2.32, 2.64, and 3.56, respectively. SS for these materials is 28.700, 11.961, and 0.742 m2/kg, respectively. The addition of BA to soil CB decreases GS (2.61 for 20% BA), increases SS (71.83 for 20% BA), decreases PI (non-plastic for 10% BA), and increases permeability (4 × 10−10 m/s for the natural soil to 1 × 10−8 m/s for 20% BA). At the optimum compaction conditions, CB has a void ratio of 0.43 and, with 20% BA, 0.64.

The addition of QF to soil CB slightly decreases GS (2.64 for 50% QF), slightly increases SS (5.980 cm2/g for 50% QF), slightly increases PI (13% for 50% QF), and practically does not change permeability (5 × 10−10 m/s). QF is the residue most like the natural soil. The addition of IS to soil CB considerably increases GS (2.98 for 50% IS), decreases SS (1.830 m2/Kg for 50% IS) and PI (0% for 50% IS), and increases permeability (2 × 10−9 m/s). IS is the most granular residue.

The results show that the addition of residues reduces the plasticity of the soils, except for QF, possibly due to muscovite in the clay fraction. Nevertheless, both natural soils showed low plasticity. Additionally, the SS increased with waste addition, except for the introduction of IS, a coarser material, into soil CB. This suggests that the overall structure is becoming finer, as smaller particles imply a higher number of particles and a larger surface area [27,28]. Despite the fineness, these particles do not appear to be active, as indicated by the decreasing plasticity with increased waste content, corroborating results from other investigations [8].

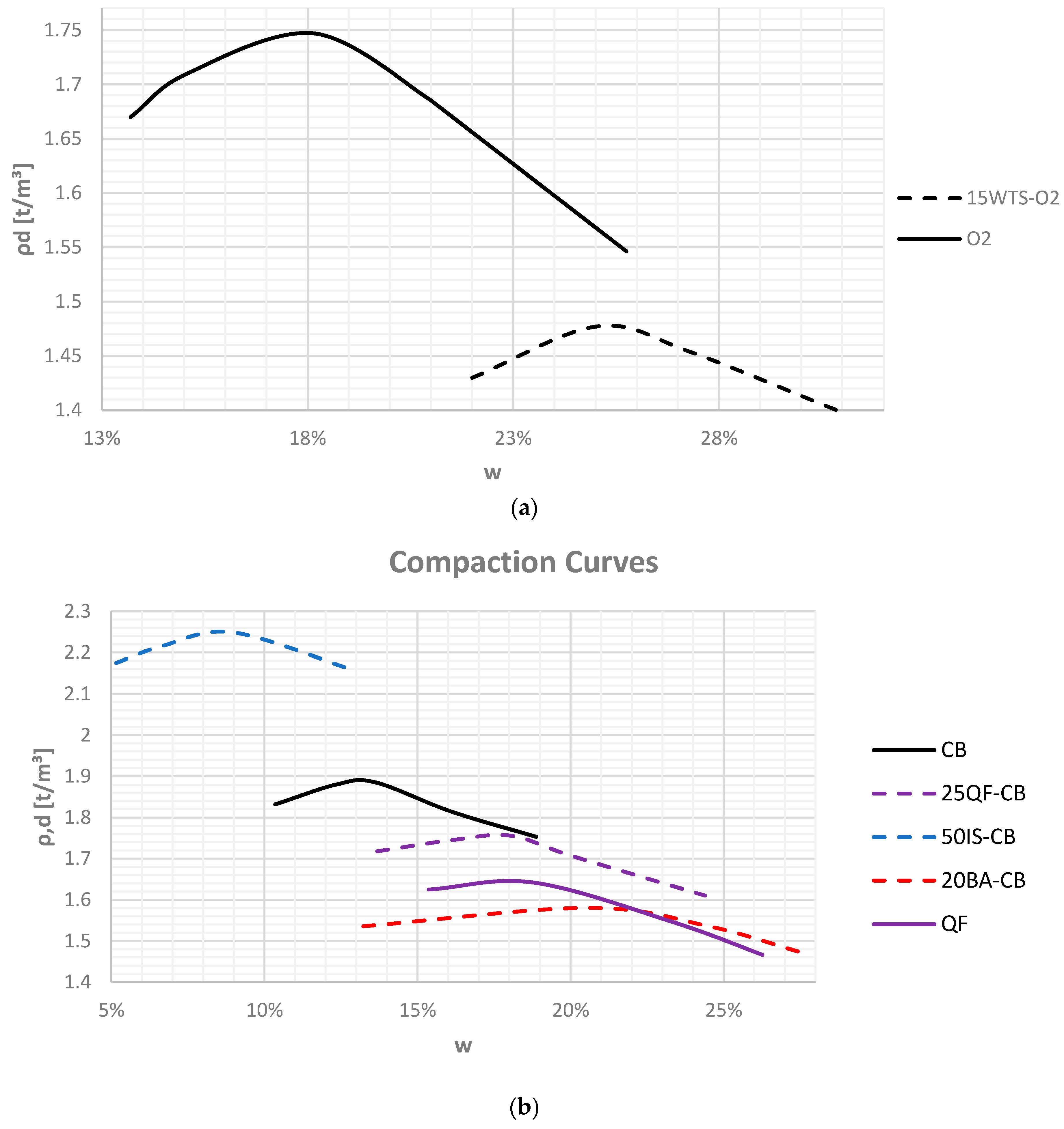

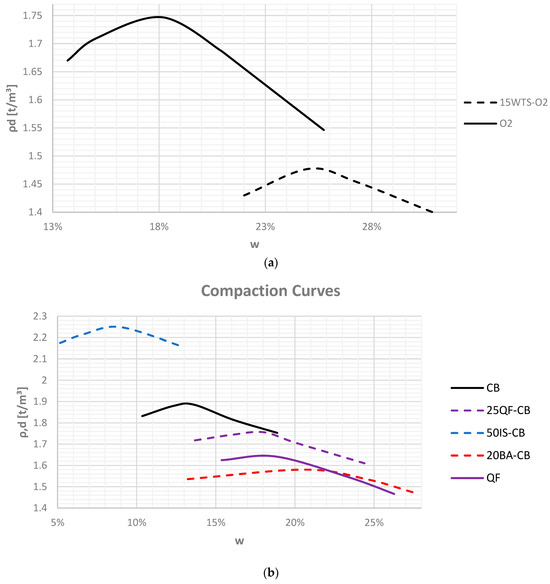

In addition to affecting permeability and plasticity, the gradation curves and particle size parameters (D10, D50, D90) play a critical role in governing the compaction behavior of soils and soil–residue mixtures. According to Terzaghi et al. (1996) [26], a well-graded soil, which exhibits a broad range of particle sizes, tends to achieve denser packing because the smaller particles fill the voids between the larger ones. This results in a lower void ratio and a higher maximum dry density. In contrast, poorly graded soils—lacking sufficient variation in particle sizes—often have a higher void ratio and are more compressible. Soil O2 is a poorly graded sand with a higher void ratio, while Soil CB is well graded and exhibits better compaction characteristics. Thus, analyzing the particle size distribution using D10, D50, and D90 parameters is essential not only for predicting permeability but also for optimizing compaction and overall geomechanical performance. Such detailed characterization helps in designing mixtures that achieve a balance between improved strength and acceptable deformability, which is crucial for applications such as embankments and retaining walls.

The specific gravity of the solids was reduced with the addition of WTS and BA, suggesting their potential as mass-saving materials in the mixtures. The lower GS results in a lower apparent density, also affecting the optimum dry density of the mixtures. The reduction in optimum dry density may also be due to a change in the soil structure, so that waste particles create more voids within the structure instead of void-filling. QF introduction did not considerably affect the soil’s specific gravity. Conversely, IS caused an increase in GS, indicating a denser and more granular structure that can contribute to improved mechanical properties.

Figure 3 presents the compaction curve for the best soil–residue mixtures.

Figure 3.

Compaction curves for the best soil–residue mixtures: (a) Soil O2 and 15WTS-O2. (b) Soil CB, QF, 25QF-CB, 50IS-CB and 20BA-CB.

3.2. Permeability Analysis

Permeability tests were conducted with hydraulic gradients of 50 and 100. The average hydraulic conductivity (k) was found to be in the order of 10−10 m/s for the soils, (4 × 10−10 m/s for CB and 5 × 10−10 m/s for O2), WTS (6 × 10−10 m/s), WTS mixtures (1 to 3 × 10−10 m/s), and QF mixtures (5 × 10−10 m/s). Despite different specific gravity of the solids, consistency limits, and grading curves, 20% WTS in mass may be added to soil O2 and 50% QF in mass may be added to soil CB without impacting their permeability.

The residues with higher finer fractions tend to provide a more entangled structure to the soils, resulting in lower permeability. The addition of 20% WTS to soil O2, despite decreasing the maximum dry density (1.75 to 1.44 g/cm3) and increasing the void ratio at the optimum point of standard energy (from 0.58 to 0.78), caused a decrease in the hydraulic conductivity, from 5 × 10−10 to 1 × 10−10 m/s. This is probably due to a rearrangement in the soil structure: a larger volume of very fine pores may be less conductive than a smaller volume of large and interconnected pores.

The permeability of IS and BA mixtures increased with higher waste contents, opposite to the trend for WTS mixtures. BA mixtures were the most permeable, with k ranging between 3 × 10−9 m/s and 1 × 10−8 m/s. BA is a low-density and non-plastic ash, with a higher fines fraction compared to soil CB. However, the addition of 25% and 50% of BA provoked the opening of visible fissures, creating preferential paths which may explain the 10- to 25-fold increase in the permeability of soil CB. For IS mixtures k ranged between 8 × 10−10 and 2 × 10−9 m/s. IS, which is a granular residue, increased permeability as higher ratios were introduced.

Desired permeability values depend on design requirements. For example, liners for waste disposal sites require very low permeability values, with a maximum allowable value of 10−9 m/s, to prevent subsoil contamination by leachate. In contrast, for engineering designs such as pavement roads and granular beds, more permeable granular materials are preferred for easier and faster drainage. The permeability factor significantly impacts design and cost, as it also affects inherent construction processes like compaction and consolidation [26].

Terzaghi et al. (1969) [26] report the interval of 10−7 to 10−5 m/s for the permeability of sands, sands with fines and silty sands, and 10−9–10−7 m/s for silts and silty clays. Pinto (2000) [42] reports typical values of 10−9–10−6 m/s for silts, 10−7 m/s for clayey sands, 10−5 m/s for fine sands, and 10−4 m/s for medium sands. The values obtained in this study, however, refer to sands with fines compacted in optimum conditions, and therefore with k-values much lower than the minimum values suggested by these authors.

3.3. Mechanical Analysis

Confined compression tests were carried out to compare the compressibility of soils and mixtures. The overall compressibility behavior of the soils was not deeply impacted.

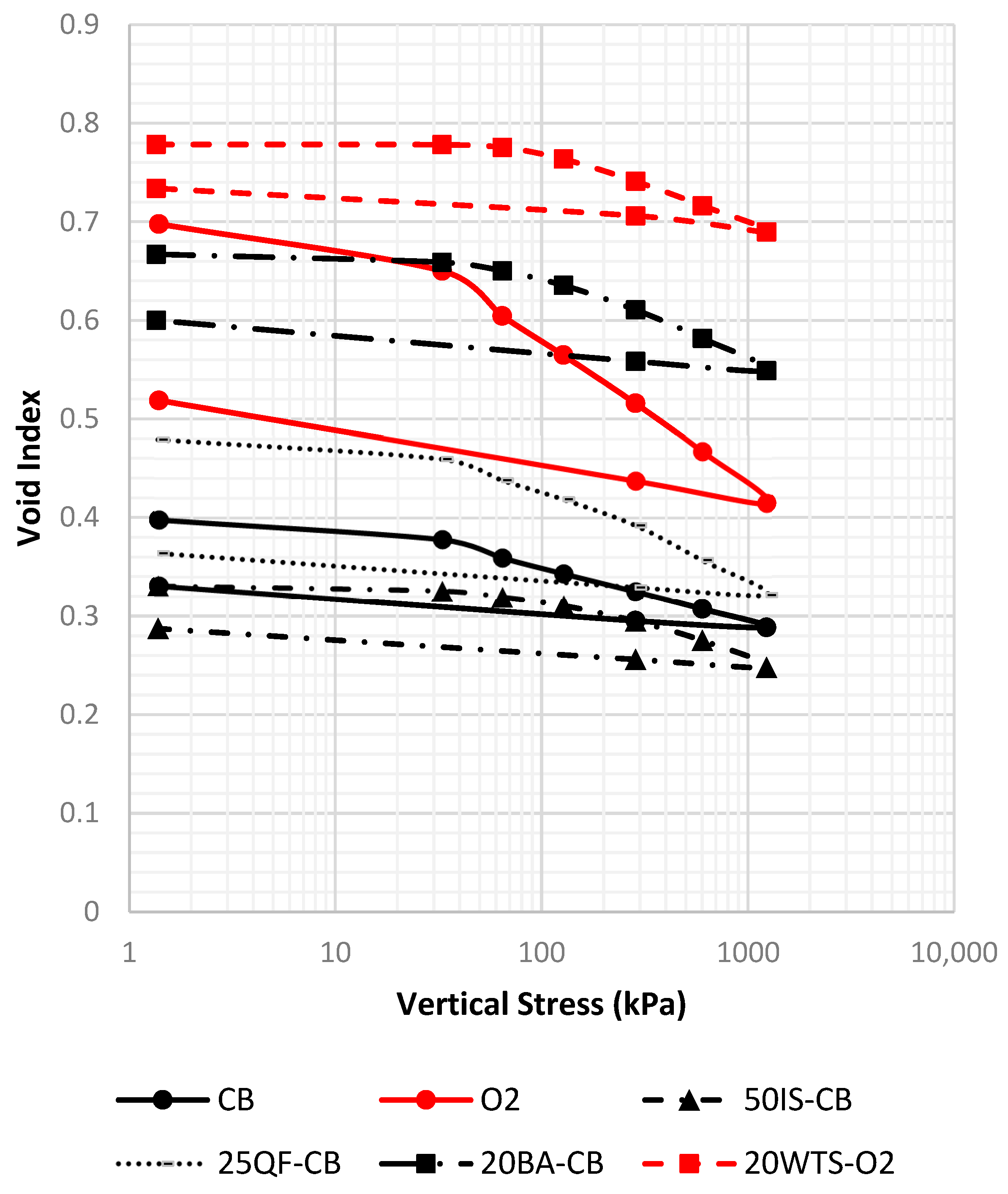

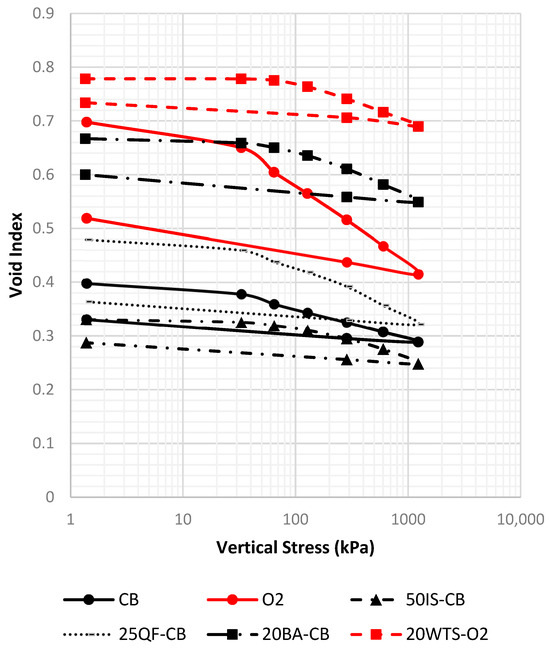

Void ratio as a function of effective stress curves for the best soil–residue mixtures are presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Figure 4 shows that the total variation in void ratio as a function of effective vertical stress did not remarkably differ between each soil and correspondent best soil–residue mixtures, but the initial void ratios for soils and mixtures were very different, as shown in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Confined compression tests—void ratio as a function of effective vertical stress for the soils and best soil–residue mixtures.

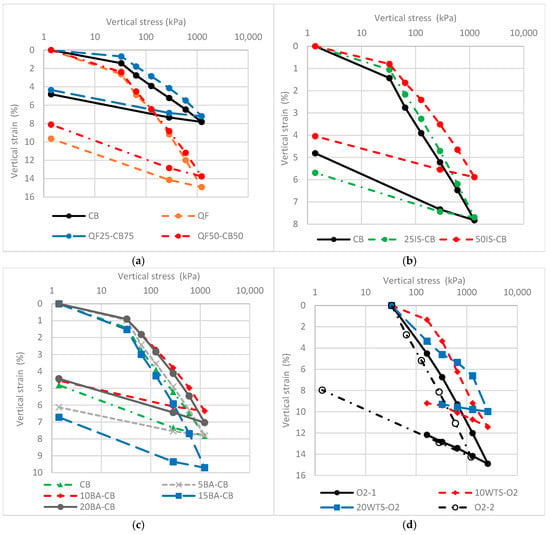

Figure 5.

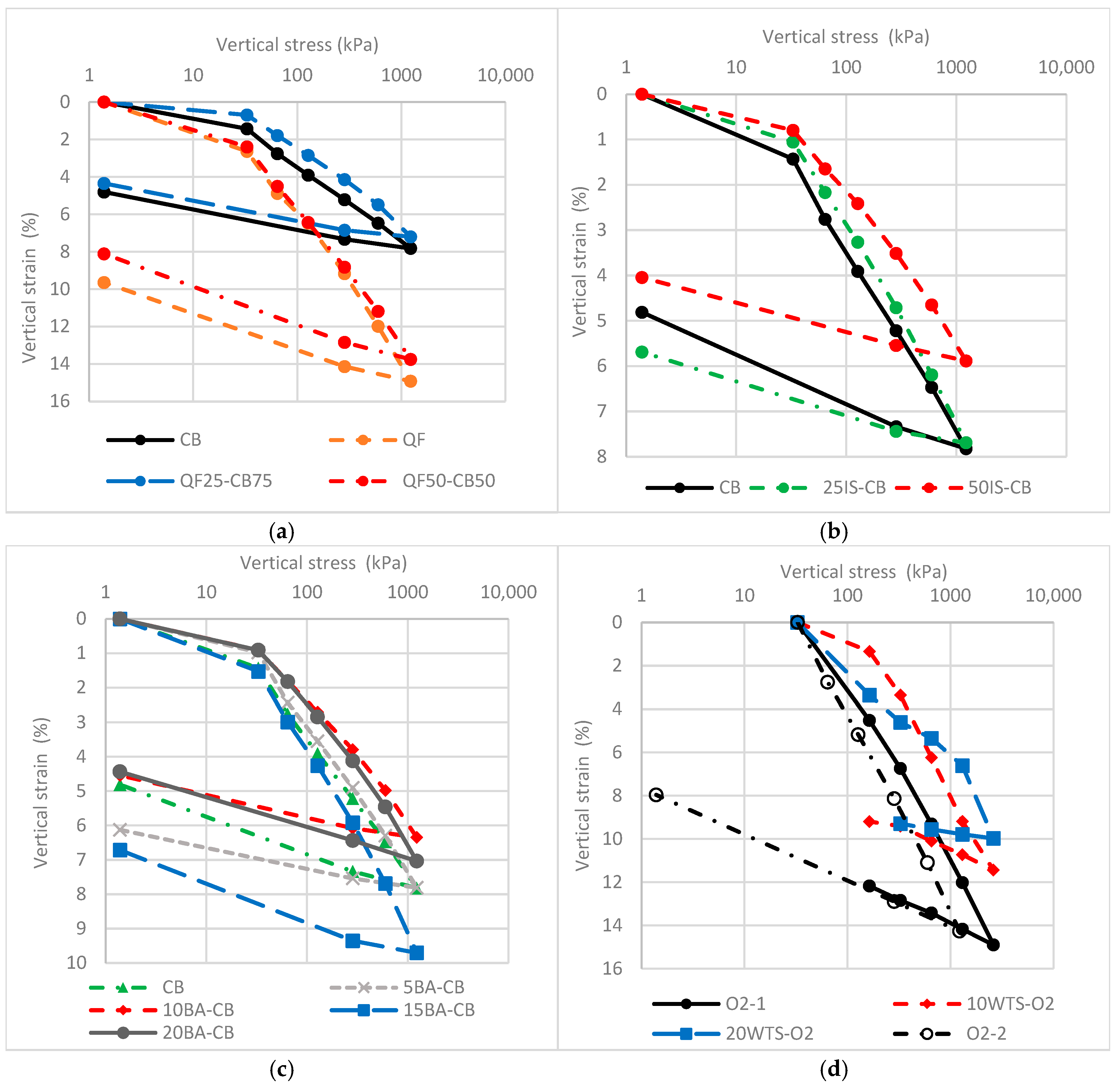

Confined compression tests—vertical strain as function of effective vertical strain: (a) soil CB and mixtures with QF; (b) soil CB and mixtures with IS; (c) soil CB and mixtures with BA; (d) soil O2 and mixtures with WTS.

The curves of vertical deformation (vertical displacement divided by the initial specimen height) as a function of vertical stress in Figure 5 allow a more detailed view of the deformation behavior of the materials and a comparison among materials. QF is more compressible than soil CB; however, 25% of QF addition does not increase the soil compressibility. On the other hand, 50% addition leads to a duplication of the vertical deformation for the range of applied vertical stresses. The addition of 25% IS does not change the soil compressibility, whereas 50% of IS creates a more rigid material.

The differences between the curves of soil CB and BA-CB mixtures may be inside the range of experimental variation: the 5BA-CB curve is practically coincident with that of soil CB, and 10% and 20% BA mixtures were slightly less compressible than the soil; however, the mixture with 15% BA reached almost 10% vertical deformation for the applied vertical stress.

Soil O2 is more compressible than soil CB (15% vertical deformation compared to 8% at maximum vertical stress), and the addition of dried WTS had a positive effect on soil deformability. WTS is a very difficult material to work with and to use to obtain homogeneous mixtures, but its addition decreased the permeability and deformability of soil O2, which are desirable results for compacted liners for waste landfills.

Confined compression data for various compacted materials were reviewed from the existing literature. Although these data are not consistently standardized as Cc, Cr, or as vertical strain to vertical stress ratio, comparisons indicated that the results from oedometer consolidation tests on compacted soils and mixtures aligned well with those typically used for liners and embankments [26,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

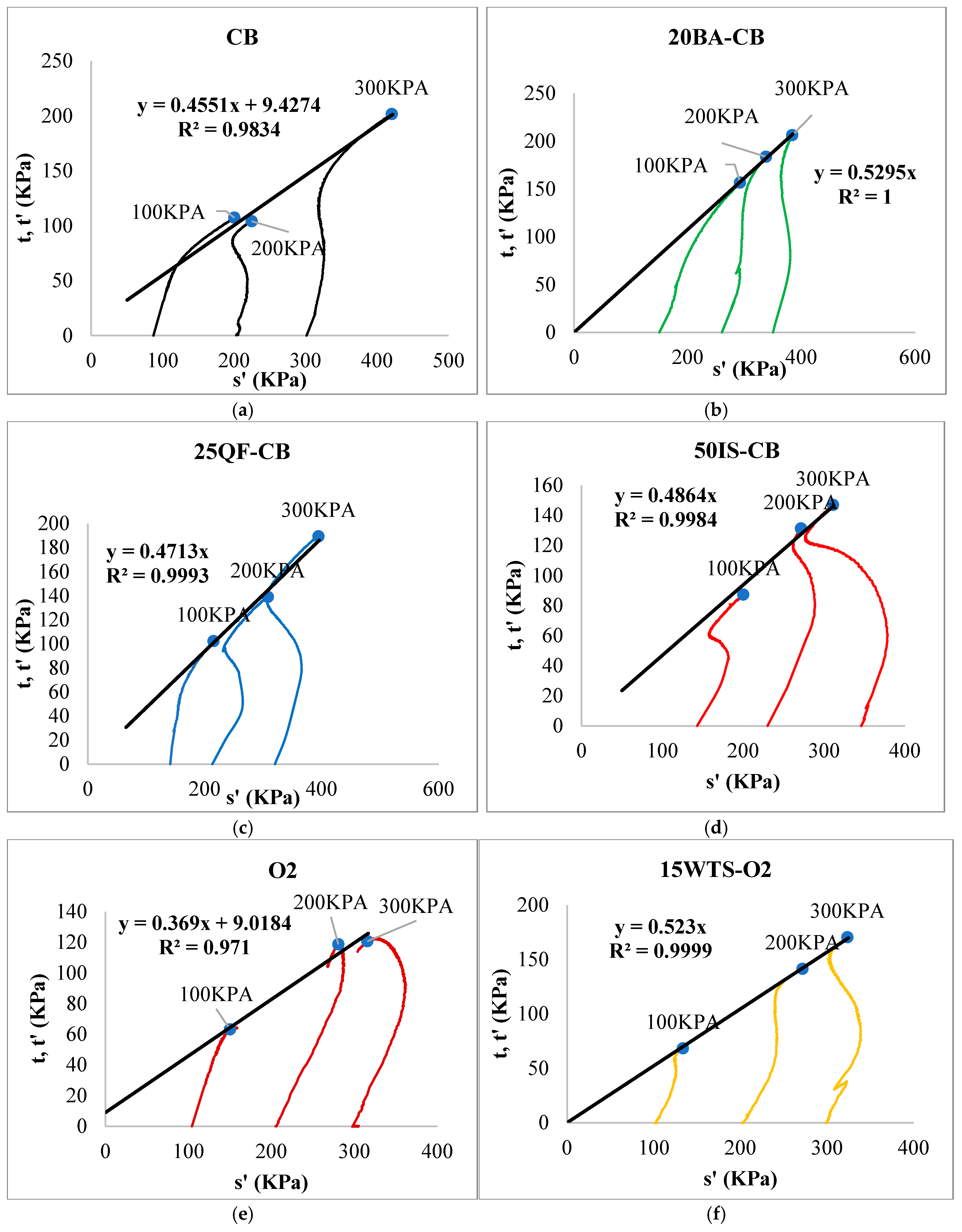

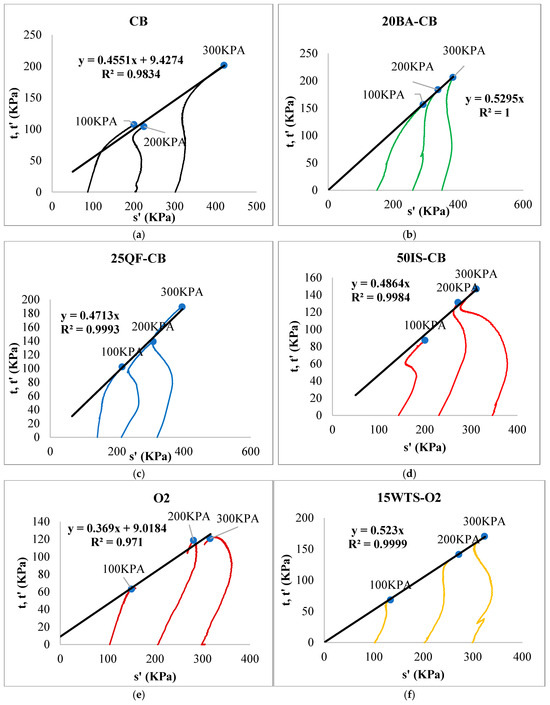

Stress paths from the CIU triaxial tests are presented in Figure 6. Soil CB presented cohesion of 11 kPa and friction angle of 27°, whereas these values for soil O2 were 10 kPa and 22°, respectively. Despite being classified as granular soils, both CB and O2 exhibited relatively low friction angles, probably due to the presence of silt and clay particles. Terzaghi et al. (1996) [26] indicated that friction angle values can be as low as 24° for coarse-grained soils containing silt. Altum et al. (2011) [45] particle shape has a limited effect on the friction angle of sands in comparison to grain size distribution.

Figure 6.

Stress curves for the different materials: (a) soil CB; (b) soil CB with 20% of BA; (c) soil CB with 25% of QF; (d) soil CB with 50% of IS; (e) soil O2; (f) soil O2 with 15% of WTS.

Cohesion and friction angle of the mixtures, on the other hand, approached the typical behavior of granular materials: little to no cohesion and a friction angle of between 27° and 50° [42]. Several studies have reported that residues have high friction angles and the capacity to improve soil properties. Hu et al. (2016) [20] reported quarry fines with friction angles above 32°, while Vekli et al. (2016) [21] documented gains in mechanical strength using water treatment sludge and iron slags, respectively.

Table 4 exposes the mechanical parameters for all analyzed materials. The results show that the residues enhance friction angle and reduce cohesion.

Table 4.

Mechanical parameters.

The best mixtures, therefore, provided non-cohesive materials with friction angles between 27° and 32°, i.e., higher than those of the natural soils, and low compressibility and low permeability, very similar to those of the natural soils. Furthermore, the mixtures allowed the reuse of significant residues contents.

Therefore, from a mechanical perspective, the following ratios were considered optimal for each soil–residue mixture, demonstrating enhanced strength while maintaining acceptable deformability: WTS at 15%, BA at 20%, QF at 25%, and IS at 50%. Granular materials with a high friction angle and mechanically stable materials might be suitable for use as embankment layers, reinforcement pavement layers, backfill in retaining walls, trench backfilling, and geosynthetics-reinforced soil walls, among others.

The chosen optimal percentages reflect a balance between enhancing mechanical strength (via increased friction angle and reduced plasticity) and maintaining acceptable permeability and workability. These percentages were determined by systematically analyzing the changes in soil parameters with varying residue contents, as detailed in Table 2 and Table 3 and illustrated by Figure 2 and Figure 3. The interplay between particle size distribution, void ratio, and specific surface area—guided by the principles outlined by Terzaghi et al. (1996) [26] and further supported by studies such as [27,28]—justifies the selection of 15% WTS, 20% BA, 25% QF, and 50% IS as the optimal dosages.

As an integrated analysis of results, it seems that granulometric characteristics of the soils and residues significantly influence the geomechanical behavior of the mixtures, as evidenced by the compaction, permeability, and triaxial test results. Variations in particle size distribution, as quantified by parameters such as D10, D50, and D90, directly affect the packing density and interparticle contact, which in turn govern both the compaction behavior and the mechanical strength of the mixtures. For instance, the optimal mixture containing 20% biomass ash (20BA-CB) exhibited a notable increase in permeability. This increase can be primarily attributed to the formation of fissures within the compacted matrix. The fine particles in BA, which have a high specific surface area, tend to disrupt the continuity of the soil skeleton, resulting in a more heterogeneous pore structure that promotes the creation of preferential flow paths. Consequently, while these fines can enhance bonding and reduce plasticity, excessive incorporation may also lead to the development of discontinuities that compromise the overall density of the mixture.

Conversely, the addition of IS to soil CB resulted in a significant improvement in the friction angle. This waste, being a coarser residue with a lower fines content, contributes to a denser and more granular structure. This enhanced granularity promotes effective void filling and improved interparticle friction, leading to a denser packing arrangement and a higher friction angle. These effects are consistent with the classical geotechnical principles described in [26], where well-graded mixtures generally achieve a lower void ratio and higher maximum dry density, thus improving load-bearing capacity and shear strength. Microstructural analysis reveals voids between particles, which could influence densification behavior under load, akin to findings in mine tailings where micro-voids impact settlement and strength [20].

Overall, these results underscore the importance of carefully tailoring the particle size distribution within soil–residue mixtures to achieve a balance between improved strength and acceptable permeability. A detailed analysis of the gradation curves and corresponding mechanical test results not only validates the potential of these residues for soil stabilization but also provides critical insights for optimizing mixture design in practical geotechnical applications.

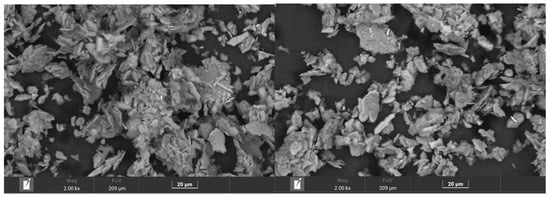

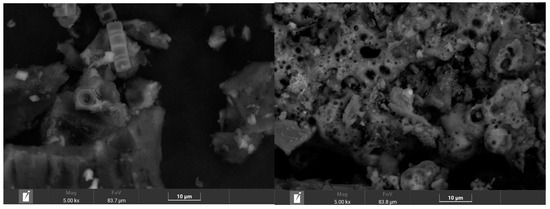

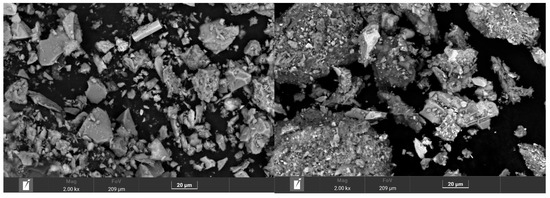

3.4. Microscopy Images Analysis

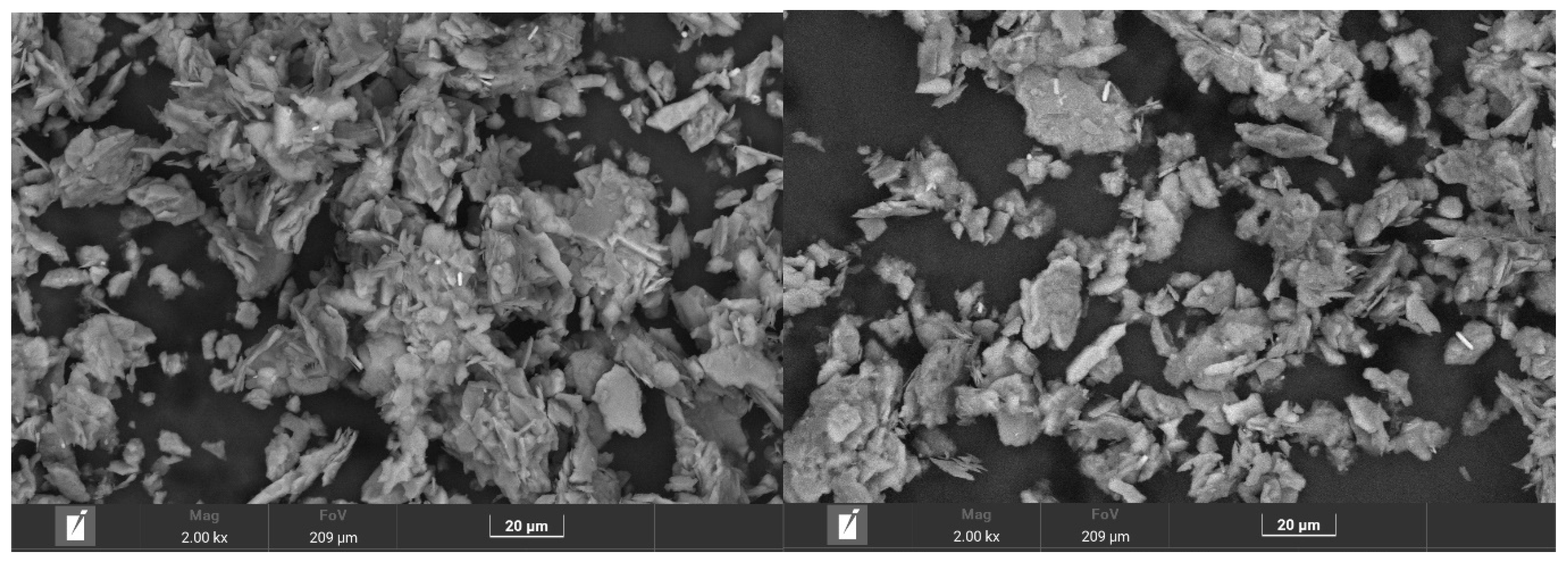

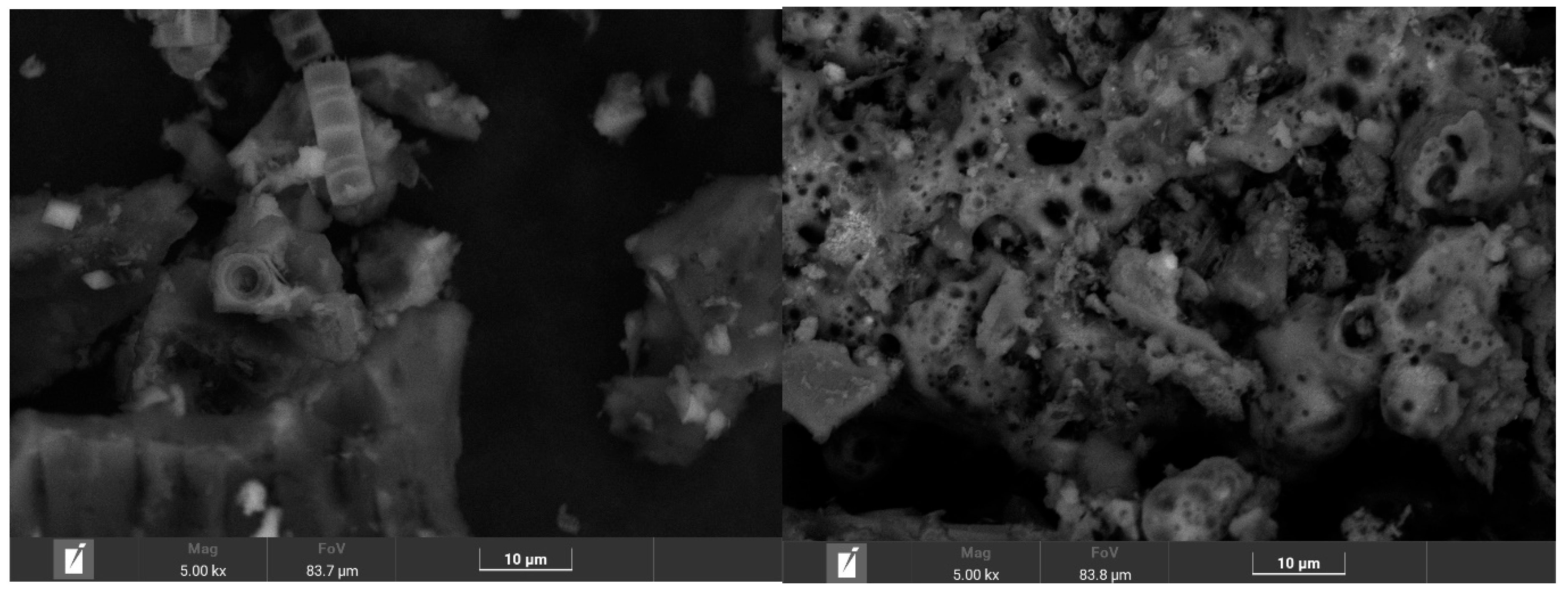

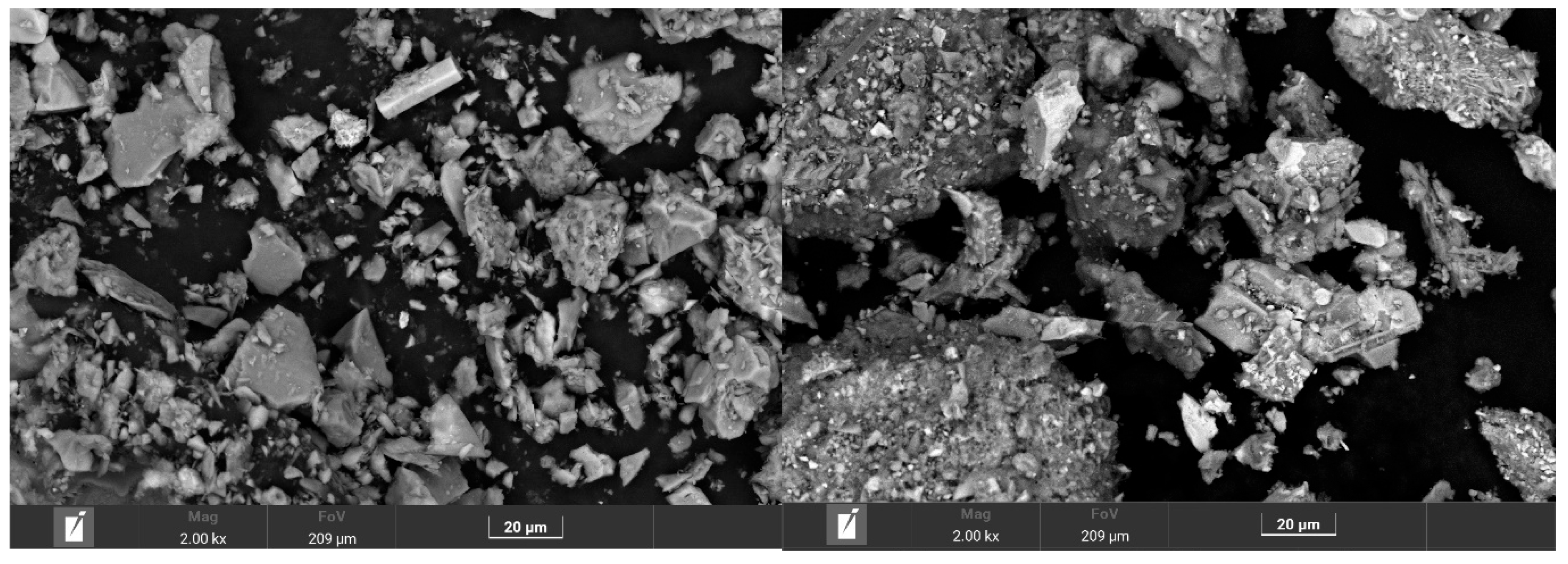

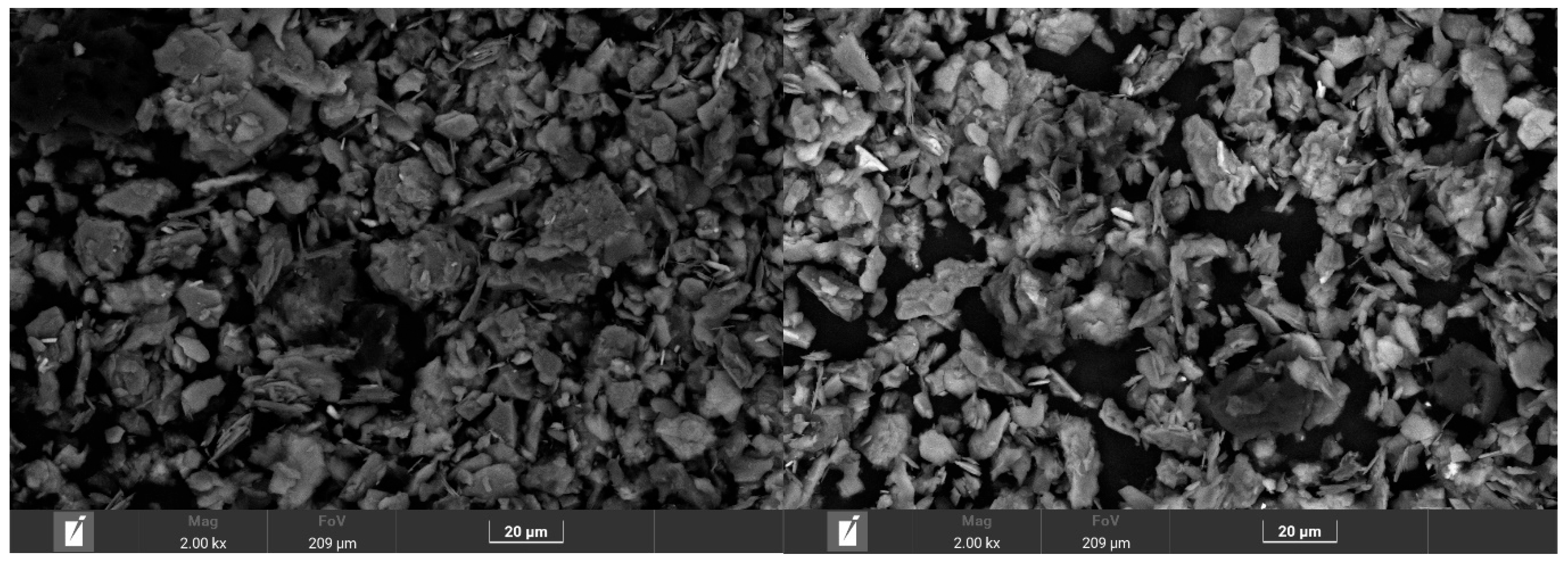

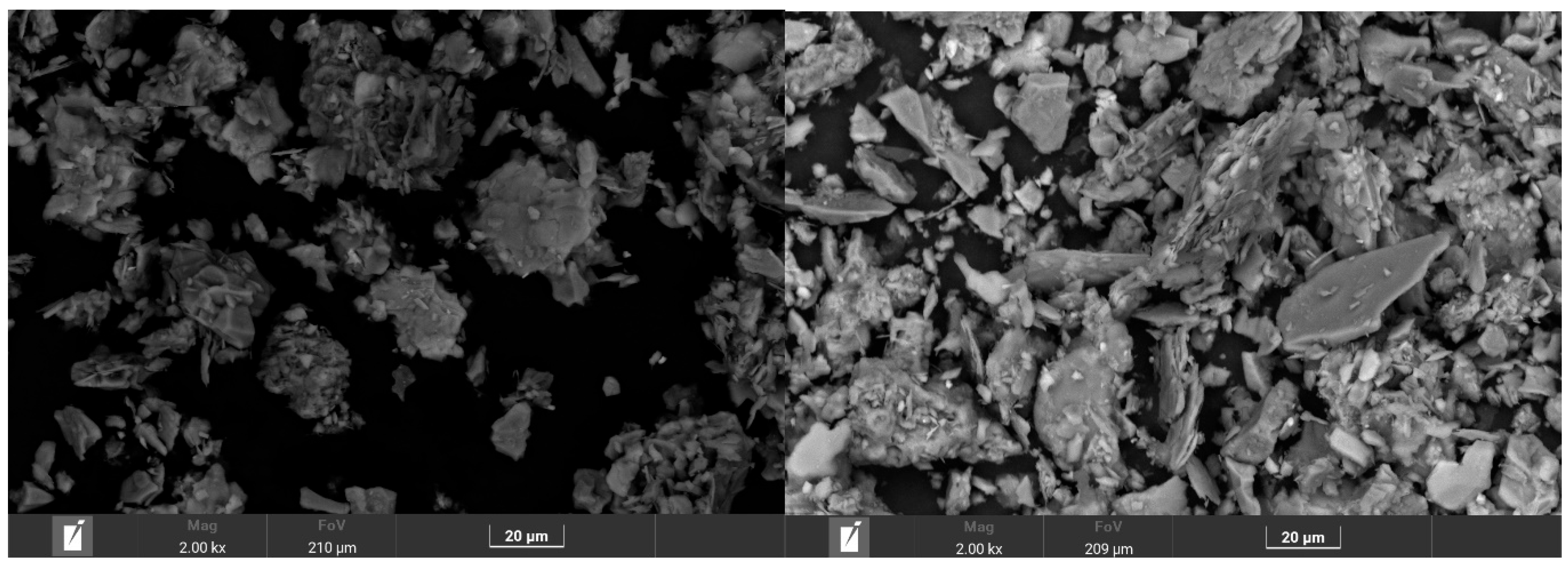

Microscopy images of the soils, residues, and optimal soil–residue mixtures are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, with magnifications ranging from 2 k× to 5 k×. These images provide a visual insight into the microstructural characteristics of the materials, complementing the granulometry and mineralogy analyses. The SEM observations reveal how the incorporation of residues alters the microstructure of the soils, which in turn governs their mechanical behavior.

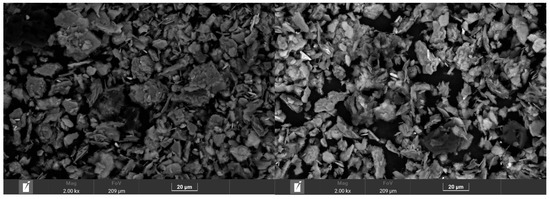

Figure 7.

Images of SEM for O2 (left) and CB (right), 2 k× magnification.

Figure 8.

Images of SEM for WTS (left, 5 k× magnification) and BA (right, 5 k× magnification).

Figure 9.

Images of SEM for QF (left, 2 k× magnification) and IS (right, 2 k× magnification).

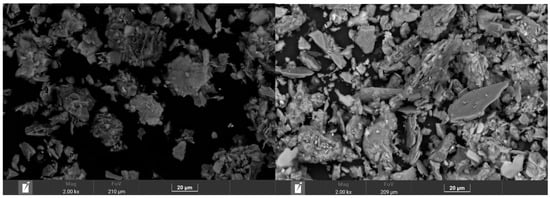

Figure 10.

Images of SEM for WTS15:85% (left) and BA20:80% (right), 2 k× magnification.

Figure 11.

Images of SEM for QF25:75% (left) and IS50:50 (right), 2 k× magnification.

The images of soils O2 (Figure 7, left) and CB (Figure 7, right) highlight their intrinsic granular structure, characterized by irregular and sharp quartz-based particles typical of schist-derived soils. Soil O2 exhibits a relatively loose, poorly graded matrix with sparse fine particles, consistent with its higher permeability and lower maximum dry density. In contrast, soil CB displays a more uniformly distributed particle structure with fewer fines, aligning with its observed lower permeability and higher compaction density. These observations are consistent with the granulometric data presented in Table 2.

The residues WTS, BA, QF, and IS exhibit distinct microstructural features that influence their integration into the soil matrices. WTS (Figure 8, left) shows a dense, fine matrix with an extensive network of micro-pores, corresponding to its high SS (18.100 cm2/kg). This finer structure likely contributes to the reduction in permeability observed when WTS is added to soil O2, as the fine particles fill the voids between coarser soil grains, leading to denser packing and a reduced void ratio [33]. However, the formation of a continuous, finely distributed phase may also increase water retention and compressibility if not optimally dosed.

BA (Figure 8, right) exhibits a sponge-like structure composed of cavities, significantly increasing its specific surface area (SS = 28.700 cm2/kg). This fine, porous morphology disrupts the continuity of the soil skeleton, creating preferential flow paths that explain the increased permeability observed in BA mixtures. According to the literature, this waste may provoke pozzolanic reactions which may enhance cohesion and reduce plasticity [29]. However, the presence of amorphous gels coating soil particles was not detected in the SEM images. On the other hand, excessive BA content can lead to fissure formation, compromising the overall density of the mixture.

The SEM observations of QF (Figure 9, left) show an intermediate texture, with a mix of fine and coarse particles. Its moderately fine microstructure aligns with the permeability measurements, where QF mixtures showed only slight changes compared to the natural soil. The balance in particle sizes contributes to a more homogeneous pore structure, supporting moderate compressibility while maintaining soil strength [19,20].

Conversely, IS (Figure 9, right) reveals a coarse and angular morphology, with a clearly defined granular structure. The irregular and angular particles of IS create a skeletal framework that enhances interparticle friction, leading to a denser and more stable structure [23]. Similar microstructural features have been observed in iron and copper tailings, where particle roughness and pore spaces influence geomechanical behavior [20]. The coarser character supports the mechanical results and analysis, where IS incorporation into soil CB resulted in an increased GS and improved friction angle. This granularity supports the mechanical improvements observed in IS mixtures, such as increased friction angles and reduced compressibility. The microstructural variations in IS particles, ranging from amorphous to fine-crystalline, may reflect differing cooling rates during solidification, as noted in previous studies on iron and steel slag [46].

The images of the soil–residue mixtures (Figure 10 and Figure 11) illustrate how the incorporation of residues alters the microstructure. For example, the 15WTS-O2 mixture (Figure 10, left) exhibits a finer, more compact structure, visually supporting the recorded decrease in permeability and changes in compaction behavior [33]. Similarly, the 20BA-CB mixture (Figure 10, right) reveals a sponge-like, porous structure with visible cavities, which likely contribute to the observed fissure formation and increased permeability [29]. In contrast, the 50IS-CB mixture (Figure 11, right) displays a distinctly granular and coarser texture, reinforcing the mechanical improvements and higher friction angle measured during the triaxial tests [23].

Overall, the SEM images confirm the granulometric distributions and particle size parameters obtained from sieve analysis, while providing evidence of how these microstructural differences translate into variations in mechanical properties. Fine residues like WTS improve soil cohesion and reduce permeability by filling interparticle voids, while coarser residues like IS enhance load-bearing capacity through increased friction and denser packing [26,27]. These observations underscore the importance of tailoring particle size distribution to achieve a balance between improved strength and acceptable permeability in soil–residue mixtures. However, a comprehensive geotechnical assessment is important to detect other influencing factors on the geomechanical properties, as is the case of BA addition resulting in permeability increase.

In addition to the geomechanical properties, the microstructural features also raise questions about environmental and durability considerations. The high surface area of some residues, while beneficial for reducing permeability, could raise leachability concerns (as suggested by [6] and [8]), though this was not evaluated in the current study. Similarly, the angular morphology of IS particles, though enhancing friction angles, may lead to particle breakdown over time, potentially affecting long-term durability [23].

Further chemical analysis and long-term field studies are needed to evaluate these aspects and ensure the safe and sustainable reuse of industrial residues in geotechnical applications. The evaluation of heavy metals, organics, soluble salts, and carbonate contents, and mineralogical (through X-ray diffraction (XRD)) and elemental (through Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS)) composition, among others, is essential for analysis of the environmental safety, geotechnical performance, and long-term durability of the materials when reused in construction or geotechnical applications.

Conversely, residues with high levels of heavy metals or soluble salts could pose environmental risks or adversely affect the soil’s structure by inducing expansive reactions. Residues such as BA and QF may contain trace heavy metals, organic compounds, and salts that could leach into the surrounding soil and groundwater over time, posing potential contamination risks. It is essential to assess the leaching potential and solubility of chemicals to ensure that the reuse of these materials does not inadvertently introduce contaminants into the environment. Leaching tests simulate dynamic environmental conditions to evaluate contaminant mobility, whereas solubility tests determine the maximum concentration of a substance that can dissolve under equilibrium conditions.

In addition to the mechanical properties, the chemical characteristics of the residues and mixtures are being evaluated, as this research is ongoing. This includes analyzing leachate levels and regulatory limits, as well as assessing their origins through mineralogical analysis, to gain a broader understanding of the materials and their potential contamination risks.

4. Conclusions

Within a unified comparative framework, four industrial residues showed distinct, dosage-dependent effects on two sands with fines. Fine residues (WTS, BA) generally reduced plasticity. WTS also lowered k to ~10−10 m/s, whereas BA at higher contents raised k to 10−9–10−8 m/s. Coarser residue (IS) increased φ′ (~29°) with k ~10−9 m/s; QF yielded moderate changes and preserved k ~10−10 m/s, with gains at 25% but not at 50%. Across the tested ranges, 15% WTS, 20% BA, 25% QF, and 50% IS provided the best balance between strength (higher φ′/lower PI) and transport behavior for the specific soils studied. The findings support the application-specific selection of residues (e.g., WTS for low-k barriers, and IS for strength/drainage layers), while underscoring the need to validate environmental safety (e.g., leaching) and long-term durability before field deployment and to extend verification to other soil types and stress paths. The environmental safety of the proposed mixtures, assessed by laboratory tests, is the subject of a companion paper. This study demonstrates that such industrial residues can be reused to enhance soil properties, offering a sustainable alternative to traditional stabilization methods and contributing to the circular economy in the industrial and construction sectors. Moreover, by quantifying the mechanical–hydraulic impacts across several residue–soil combinations, the work provides practical guidelines for residue-based stabilization, highlighting the broader potential of industrial wastes to support the circular economy in civil and geotechnical engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and A.A.; methodology, A.S. and M.E.B.; validation, M.E.B., V.C. and A.A.; formal analysis, A.S., M.E.B. and A.A.; investigation, A.S.; resources, V.C. and A.A.; data curation, A.S. and M.E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.E.B., V.C. and A.A.; supervision, M.E.B., V.C. and A.A.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, V.C. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the GeoBioTec Research Unit, through the strategic projects UIDB/04035/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04035/2020, accessed on 25 September 2025) and UIDP/04035/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04035/2020, accessed on 25 September 2025), funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP/MCTES (Portugal) through national funds (PIDDAC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The researchers acknowledge the involved companies for the soils and waste materials supply, as well as Ana Paula Gomes from the Optical Center, University Beira Interior (UBI), University of Aveiro (UA) for supporting the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sato, T.; Qadir, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Endo, T.; Zahoor, A. Global, regional, and country level need for data on wastewater generation, treatment, and use. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 130, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeheyis, M.; Hewage, K.; Alam, M.S.; Eskicioglu, C.; Sadiq, R. An overview of construction and demolition waste management in Canada: A lifecycle analysis approach to sustainability. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2013, 15, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benachio, G.; Freitas, M.; Tavares, S. Circular economy in the construction industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polańska, B.; Rainer, J. Rigid inclusion ground improvements as an alternative to pile foundation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 869, 052080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalize, P.; Albuquerque, A.; Di Bernardo, L. Impact of Alum Water Treatment Residues on the Methanogenic Activity in the Digestion of Primary Domestic Wastewater Sludge. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, L.; Studart, A.; Albuquerque, A.; Pais, L.A.; Boscov, M.E.; Cavaleiro, V. Mechanical and Chemical Behaviour of Water Treatment Sludge and Soft Soil Mixtures for Liner Production. Open Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 16, e187414952211101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalize, P.; Souza, L.; Albuquerque, A. Reuse of alum sludge for reducing flocculant addition in water treatment plants. Environ. Prot. Eng. 2019, 45, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvan, E. Geotechnical Properties of Mixtures of Water Treatment Sludge and Residual Lateritic Soils from the State of São Paulo. Ph.D. Thesis, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/3/3145/tde-08032021-094316/publico/EdyLeninTejedaMontalvanCorr21.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Roque, A.; Carvalho, M. Possibility of using the drinking water sludge as geotechnical material. In Proceedings of the 5th ICEG Environmental Geotechnics, Cardiff, UK, 26–30 June 2006; pp. 1535–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Mahmood, Z.; Nisar, A.; Aamir, M.; Farid, A.; Waseem, M. Compaction performance analysis of alum sludge waste modified soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 116953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.; Vassilev, C. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, S.; Koppejan, J. The Handbook of Biomass Combustion and Co-Firing. Earthscan; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Studart, A.; Marchiori, L.; Vitoria, M.; Albuquerque, A.; Almeida, P.; Cavaleiro, V. Chemical and Mineralogical Characterization of Biomass Ashes for Soil Reinforcement and Liner Material. KnE Mater. Sci. 2022, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studart, A.; Marchiori, L.; Albuquerque, A.; Cavaleiro, V.; Pais, L.; Boscov, M.; Strozberg, I. Residue’s physical identification for soil-waste materials. In Proceedings of the XVIII European Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (XVIII ECSMGE 2024), Lisbon, Portugal, 26–30 August 2024; ISBN 978-1-032-54816-6. 6p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, A.; Eberemu, A.; Osinubi, K. Strength Consideration in the Use of Lateritic Soil Stabilized with Fly Ash As Liners and Covers in Waste Landfills. In Proceedings of the GeoCongress 2012, Oakland, CA, USA, 25–29 March 2012; ASCE. pp. 3835–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, L.; Studart, A.; Morais, M.; Alburquerque, A.; Cavaleiro, V. Geotechnical characterization of vegetal biomass ashes based materials for liner production. In RILEM Bookseries, Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Testing and Experimentation in Civil Engineering (TEST&E 2022), Caparica, Portugal, 21–23 June 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 41, pp. 67–82. ISBN 978-3-031-29191-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Ribeiro, A.; Silva, A.; Faria, P. Overview of mining residues incorporation in construction materials and barriers for full-scale application. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starý, J.; Jirásek, J.; Pticen, F.; Zahradník, J.; Sivek, M. Review of production, reserves, and processing of clays (including bentonite) in the Czech Republic. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 205, 106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, M.; Taha, Y.; Kchikach, A.; Benzaazoua, M.; Hakkou, R. Valorization of Phosphate Mine Waste Rocks as Materials for Road Construction. Minerals 2019, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Wen, Q. Geotechnical Properties of Mine Tailings. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 29, 04016220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekli, M.; Çadır, C.; Şahinkaya, F. Effects of iron and chrome slag on the index compaction and strength parameters of clayey soils. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.; Fanijo, E. A Review of the Influence of Steel Furnace Slag Type on the Properties of Cementitious Composites. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatak, N.; Seal, R.R., II; Hoppe, D.; Green, C.; Buszka, P. Geochemical Characterization of Iron and Steel Slag and Its Potential to Remove Phosphate and Neutralize Acid. Minerals 2019, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mymrin, V.; Ponte, H.; Ponte, M.; Maul, A. Structure formation of slag-soil construction materials. Mater. Struct. 2005, 38, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalabi, F.; Asi, I.; Qasrawi, H. Effect of by-product steel slag on the engineering properties of clay soils. J. King Saud Univ. -Eng. Sci. 2017, 29, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzaghi, K.; Peck, R.; Mesri, G. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 1996; p. 664. [Google Scholar]

- Pennell, K. Specific Surface Area. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 4: Physical Methods; Dane, J.H., Topp, G.C., Eds.; SSSA Book Series; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, T. Specific Surface Area. In Powder Technology Handbook, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastelli, M.; Cambi, C.; Zucchini, A.; Sassi, P.; Pandolfi Balbi, E.; Pioppi, L.; Cotana, F.; Cavalaglio, G.; Comodi, P. Use of Biomass Ash in Reinforced Clayey Soil: A Multiscale Analysis of Solid-State Reactions. Recycling 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baǧrıaçık, B.; Güner, E. An Experimental Investigation of Reinforcement Thickness of Improved Clay Soil with Drinking Water Treatment Sludge as an Additive. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 3619–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.; Oliveira, D.; Varum, H.; Alves, C.; Camões, A. Experimental characterization of physical and mechanical properties of schist from Portugal. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, P. Evolução Tertiary Tectono-Sedimentary of the Sarzedas Region (Portugal). Comun. Dos Serviços Geológicos De Port. 1987, 73, 67–84. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Studart, A.; Albuquerque, A.; Cavaleiro, V.; Boscov, M.; Rocha, F.; Silva, E. Geotechnical comparison of water treatment sludge and biomass ashes for soft soils’ application: A greener approach analysis. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on Environmental Geotechnics (9ICEG), Chania, Greece, 25–28 June 2023; pp. 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17892; Part 1: Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Determination of Water Content. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2014; 10p.

- ISO 17892; Part 2: Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Determination of Bulk Density. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2014; 14p.

- ISO 17892; Part 4: Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Determination of Particle Size Distribution. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2016; 31p.

- ISO 17892; Part 12: Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Determination of Liquid and Plastic Limits. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2018; 27p.

- ISO 17892; Part 11: Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Permeability Tests. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2019; 20p.

- ASTM D4829; Standard Test Method for Expansion Index of Soils. American Society for Testing and Material: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021; 7p.

- Gómez-Tena, M.; Gilabert, J.; Machí, C.; Zumaquero, E.; Toledo, J. Relationship between the specific surface area parameters determined using different analytical techniques. In Proceedings of the XIV Foro Global Del Recubrimiento Cerámico (Qualicer 2014), Castellón, Spain, 17–18 February 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, P.; Kalla, P.; Nagar, R.; Agrawal, R.; Jethoo, A. Laboratory investigations on hot mix asphalt containing mining waste as aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 168, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C. Curso Básico de Mecânica dos Solos, 2nd ed.; Oficina de Textos: São Paulo, Brazil, 2000; 247p, ISBN 85-86238-12-0. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.; Bentley, S. Correlations of Soil Properties; Pentech Press: London, UK, 1991; 135p. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Qi, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, K.; Zang, X. Experimental study on consolidation characteristics of deep clayey soil in a typical subsidence area of the North China Plain. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1084286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altum, S.; Goktepe, B.; Sezer, A. Relationships between Shape Characteristics and Shear Strength of Sands. Soils Found. 2011, 51, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouwenaars, R.; Zamora, R. Microscopic Analysis of Iron and Steel Slag Used as a Source of Cationic Precipitation Agents in Water Treatment. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Materials Chemistry and Environmental Protection, Sanya, China, 23–25 November 2018; pp. 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, P.T. 100 Barragens Brasileiras: Casos Históricos, Materiais de Construção, Projetos; Oficina de Textos: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996; 648p. [Google Scholar]

- Boscov, M.; Soares, V.; Vasconcelos, F.; Ferrari, A. Geotechnical properties of a silt-bentonite mixture for liner construction. In Proceedings of the 17 ICSMGE—XVII International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, Alexandria, Egypt, 5–9 October 2009; Volume 1, pp. 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, R.; Boscov, M.; Costa, M. Collapse potential of a lateritic clay liner by contact with the liquid phase of red mud. In Proceedings of the 6ICEG—6th International Congress on Environmental Geotechnics, New Delhi, India, 8–12 November 2010; Volume 1, pp. 368–373. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).