Abstract

The increasingly stringent environmental requirements, as well as the tendency to achieve significant savings of energy products in HMA production processes, prompted researchers to investigate the possibility of reducing the moisture of the stone aggregate which is used in production of hot asphalt mixtures. The goal of this paper is to determine the effect of various drying parameters on the aggregate moisture loss. The parameters which were analyzed and observed in various combinations were selected on the basis of the production process of an asphalt plant, and they are as follows: the air flow speed (3.86 m/s, 4.53 m/s and 5.94 m/s), the drying temperature (basic temperatures 33.1 °C, 50.4 °C and 71.7 °C) and the time of exposure of the aggregate to drying (30, 45 and 60 s). In order to research the effect of reduction in moisture of the stone material, a laboratory model of a belt dryer (chamber with a cover) was conceived and made with a drying device that can control the air flow speed from 3.86 m/s to 6.32 m/s and the temperature, ranging from 33 °C to 110 °C. Tests were carried out in order to determine the moisture loss of different aggregate fractions, namely 0/2, 2/4, 4/8, 8/11, from the total (natural) moisture of fractions that are used as aggregate in the production of hot mix asphalt (HMA). In all, there were 162 samples of aggregate prepared and tested. Results showed that for different aggregate fractions, the ranges of the value of the moisture loss are considerably different and that they depend on the parameters of drying and the natural moisture of the aggregate. It was noticed that there was less moisture loss in fractions at a lower air flow speed (3.86 m/s) than there was at higher speeds, while the highest aggregate moisture loss was noticed at an air flow speed of 5.94 m/s. For all duration times of drying, regardless of the drying temperature or speed, it is noticed that, with the prolongation of the drying time, the aggregate moisture loss becomes more intense. The drying temperature directly affects the reduction in the aggregate moisture; the higher the air flow temperature is, the more significant the moisture loss is during drying of the aggregate. The results of the linear regression and the coefficient of determination R2 indicate a very firm connection between the loss of the aggregate moisture and the duration of the drying time. From the obtained equations, it is possible to calculate the reduction in the aggregate moisture for different lengths of drying duration and different drying temperatures.

1. Introduction

Hot-mix asphalt mixtures (Hot Mix Asphalt—HMA) are mineral mixtures consisting of stone chippings, sand, filler and bitumen, produced by the hot procedure in asphalt plants at temperatures from 135 °C to 170 °C. Sometimes additives such as adhesion agents, modifiers or fibers are incorporated to improve their performance. Hot-mix asphalt mixtures are quality mixtures, dominant in the production of asphalt mixtures and they are installed in base, binding and wearing courses of the pavement of roads for all groups of traffic loads. During the production of hot-mix asphalt, energy products are used, such as fossil fuels, heating oil, natural gas or electricity, for various purposes: to heat bitumen, to dry and heat the stone material, to operate the dust removal fan, to drive the plant and to operate the control room. At the same time, due to the operation of the asphalt plant, significant quantities of thermal energy are released into the surrounding air in the form of exhaust gases which, in addition to water vapor, also contain chemical compounds such as carbon dioxide CO2 and monoxide CO and the sulfur compounds SO2 and SO3. During production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures, there is a considerable consumption of thermal energy, as well as an adverse impact on the environment. For that reason, the tendencies to rationalize energy consumption, as well as to reduce the harmful effects of the production on the environment, occur in the field of production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures.

The energy consumption in the process of drying and heating of an asphalt mixture ranges from 70 to 100 kWh per ton produced and 5–8 kWh in their transport and storage, whereas during the production process, from 18.65 (light oil) to 33.73 (brown coal) kg of CO2 is released depending on the type of fuel used [1,2]. In research carried out during the production and in the laboratory, Ang et al. (1993) [3] proved that the aggregate moisture has a decisive impact on the energy consumption in the production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures. According to the same research, it was indicated that the 3% reduction in moisture in a stone mixture results in 55–60% savings in the energy consumption.

Today’s operation of existing asphalt plants implies insufficient utilization of the possible production capacities, a considerable consumption of energy caused by the intermittent production of asphalt mixtures, and the use of stone fractions that are daily exposed to the effects of the weather. The process of production of asphalt mixtures in asphalt plants is mainly carried out throughout most of the year, even in periods with unfavorable weather. By using the exhaust gases that come into the atmosphere from flue pipes and by redirecting and reusing them, it is possible to impact the consumption of energy during production of asphalt mixtures, and indirectly, the reduction in the quantities of CO2 released into the atmosphere. The exhaust gases, along with cooling water, can be used to preheat the raw material in industrial processes in a liquid or solid aggregate state. Thermal energy contained in the exhaust gas vapor consists of latent and sensible heat. Latent heat is transferred to the environment by vapor, while sensible heat contained in the resulting condensate remains unused [4]. In the case of an asphalt plant, the condensate is released into the environment through the chimney.

This paper will describe the research into the possibility of reducing the moisture of the aggregate by exploiting the thermal potential of exhaust gases. The thermal capacity of exhaust gas, which is discharged into the environment through flue pipes, can be used by returning it into the technological process of pre-drying the aggregate used in the production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures. The process of pre-drying would be carried out on a belt dryer which is located before the rotary drum for drying the aggregate, to which the hot exhaust gas would be brought by supply pipes and air flow speed regulators. The purpose of a belt dryer is to keep the aggregate in it as long as possible in order to enable the reduction in the moisture content to the greatest possible extent. For the needs of this research, a laboratory model of a dryer was designed and made, and tests were carried out on different aggregate fractions: 0/2, 2/4, 4/8 and 8/11. The effect on the reduction in the aggregate moisture, of the basic parameters for drying (namely air flow speed, temperature and time) during the process of the production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures, was studied. During the study, different combinations of the mentioned parameters were analyzed.

By reusing the exhaust gases, the temperature energy is not lost but is reused in the rapid pre-drying process of the aggregate. The objective of the research is to show that, even at low exhaust gas temperatures, it is possible to achieve a reduction in aggregate moisture. As a large amount of energy is required for the process of drying aggregates, any decrease in the original moisture content of the aggregates significantly contributes to reducing the energy required for drying and heating aggregates, which directly reduces CO2.

2. Existing Research Studies into the Possibility of Saving Energy in the Production of Hot-Mix Asphalt Mixtures

The way of producing hot-mix asphalt mixtures has remained unchanged conceptually, however, efforts to find a possibility of reducing the costs of production, increasing the efficiency of asphalt plants and reducing the harmful effect on the environment are continuously being made. Research studies were carried out in several different directions: (1) into the possibility of reducing the aggregate moisture, (2) the possibility of improvements in the technological process of the production of asphalt mixtures, and (3) the possibility of reducing the temperature of asphalt mixtures. The manufacturers of asphalt plants were looking for possible solutions for more efficient production by increasing the dimensions of the drying drum, making bigger burners and developing complex combustion solutions [4]. Some of the more important research studies and the results achieved are highlighted below in this paper.

The authors Atmaja et al. (2021) [5] state that the change in the temperature of production and the length of time of production of HMA affect the consumption of diesel fuel. With a longer time of production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures and varying the temperature for heating of the aggregate in the drying drum, increased quantities of fuel are used. For each ton of hot asphalt mixture produced, the consumption of diesel fuel amounts to 11.31 L, whilst, to increase the temperature of production by 1 °C, an additional 8.09 L of diesel fuel are necessary, which is equivalent to a consumption of energy of 290.16 MJ.

The authors Jullien et al. (2010) [6] point out that as much as 97% of the energy of the asphalt plant in operation is used to heat and dry the aggregate. According to Young (2008) [7], discontinued production leads to a greater consumption of the propellant by 20–35%. Such an operation causes an insufficient utilization of work resources, an increased energy consumption for heating the cold and moist stone mixture, and for heating and maintaining the necessary operating temperature of stored bitumen. The authors Grabowski and Janowski (2010) [8] state that for the drying of 1 t of a mineral mixture with a moisture content of 6%, 4 L of fuel (heating oil) is necessary, while for heating a dry mixture to 150 °C, an additional 3 L of fuel are necessary. In their research study, Grabowski et al. (2013) [9] indicate that the production manager has a direct impact on the level of production, as well as the energy consumption in the production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures. Jenny (2009) [10] points out that the reduction in moisture in a stone mixture by 2% results in savings in the fuel consumption in the amount of 1.5 kg/t of the asphalt mixture. Sivilevicius (2011) [11] states in his paper that the energy consumption in production of HMA does not depend only on the design temperature of the asphalt mixture, the moisture content, the temperature of the mineral mixture, the quality of fuel or the actions of the operator, but also on the construction of the burner, of the drying drum and the system for storage of bitumen. According to the authors Peinado et al. (2011) [12], the thermal energy necessary to raise the temperature of the asphalt mixture by 10 °C is about 2.62 kWh and the need to eliminate 1% of the moisture requires an additional need for energy in the amount of 8.21 kWh. The production of asphalt mixtures in different seasons results in variable energy consumption. According to the authors Androjić et al. (2020) [13], it is evident that the decrease in the moisture content in the mineral mixture results in the reduction in energy consumption by 36.3% (winter period) to 38.5% (summer period).

The authors Androjić and Dolaček-Alduk (2016) [14] researched different factors that impact the energy consumption in the rotary drum: the content of the mineral mixture moisture, a delay in the daily production, the hourly capacity of production and the temperature of the produced hot asphalt mixture. The final result of this research was to create a regression model of correlation between the energy consumption and the asphalt mixture temperature and the hourly capacity and the moisture content in the mineral aggregate. In the conducted research studies of the author Androjić (2013) [15], it was ascertained that by removing 1% of the moisture content in the mineral mixture, savings in heating the material of 15.11% and 4.2% are realized (depending on the input temperature of the mineral mixture), and thereby also a reduction in the need for its heating.

The experience also indicates that by the correct execution of the covered and shielded landfills of the stone material, significant savings of energy products necessary for drying and preheating the stone material can be achieved [16]. Namely, if the base of the storage site of stone fractions is not arranged (concreted and executed with an adequate longitudinal/transversal inclination) or covered, owing to large quantities of precipitation, a reduced capacity of operation of the asphalt plant occurs. In that case, it is necessary to prolong the time of drying due to an increase in the quantity of water in the content of the stone aggregate, whereby the fractions of the stone aggregate with the granulation of 0/2 and 0/4 mm keep water in their composition much longer and have a smaller tendency of water seepage compared to larger fractions.

Research studies of possible preheating of the stone aggregate were carried out, by which it would be possible to reduce the expenses and the time of heating and drying in the rotary drum. The preheating of the aggregate in special containers by accumulation of thermal energy of solar radiation was researched by the authors Androjić and Kaluđer (2016) [17] and Androjić et al. (2018) [18]. The models of solar containers were constructed with the primary goal of achieving the greatest possible accumulation of thermal energy obtained by solar radiation during the period of the exposure of the aggregate. The models of the container with an equal volume were made with a variable thickness of the thermal insulation on the walls of 2, 5 and 10 cm, and a glass ceiling surface that enables the entry of solar radiation into the interior of the container. In the period from May to November 2015, measuring of the temperature of the aggregate deposited in solar containers exposed to external conditions of the environment was carried out. The obtained results point to the fact that, over time, the accumulation of heat of the aggregate occurs, i.e., preheating, which results in savings of energy during the heating and drying of the mineral mixture in the rotary drum.

The research of the potential of gases that are released into the atmosphere at the end of the production process in asphalt plants to reduce the aggregate moisture, was reported by the authors Cimbola and Dolaček-Alduk (2018) [19]. By using the exhaust gases from flue pipes and their redirecting and reusing, the expense of the energy consumption in production of asphalt mixtures would be reduced, and thereby also the quantity of CO2 released into the atmosphere. The temperature of the exhaust gases ranges from 105 to 220 °C in the production of a standard hot asphalt mixture, while the temperature of the exhaust gases can reach as high as 250 °C in production of the mixture with recycled asphalt. The temperature also depends on the execution of the asphalt plant and the length of the path passed by gas before the release into the environment. The highest values of the temperature were ascertained exactly at the connection of the output duct with the rotary drum. The paper mentioned the idea about the execution of a belt dryer in which the stone material would lose a part of the moisture in a specific time frame while moving on a conveyor belt.

Grabowski et al. (2013) [9] researched to what extent the organization of the technological process and elements of automatic control could have an impact on the reduction in the energy loss during the process of production of asphalt mixtures. The results showed that even the quantity of the deposited aggregate has an impact on the cost of the production process. During long and intense precipitation, if a smaller quantity of the aggregate is deposited, only that quantity will be moist and energy will be used for drying that smaller quantity of the aggregate (and not for the total necessary quantity). The delivery of the aggregate fractions of 0/2 and 0/4 mm (fractions that absorb more water than larger fractions) was carefully planned immediately before the beginning of production of asphalt mixtures, so that no additional moisture in fractions would arise due to precipitation and those fractions were deposited under shelters. Larger aggregate fractions were also delivered before the beginning of production, and they were deposited on an open storage site. The described organizational changes enabled savings in the energy consumption during the production of asphalt mixtures by as much as 50%. Beside those basic factors that impact the energy consumption in the drum for drying the aggregate (the temperature of the aggregate and the content of moisture), Huang et al. (2019) [20] also analyzed the air flow during combustion and the pressure in the drying drum. The optimum air flow during combustion can reduce the energy consumption. A greater air flow during combustion results in a greater loss of the heat, while a smaller air flow during combustion can lead to insufficient combustion. The pressure in the drum has an adverse impact on the energy consumption; the reduction in the pressure results in negative pressure and an increase in the rate of air passage in the drying drum, leading to an increase in the excess air coefficient during combustion and an increase in the heat loss.

A worldwide indicator of tendencies to realize a reduced consumption of thermal energy and lower emissions of the exhaust gases is the use of warm-mix asphalt mixtures (warm-mix asphalt—WMA) which are produced at the temperatures from 100 °C to 135 °C (Choudhary and Julaganti, 2014; Rubio et al. 2012; Vaitikus et al. 2009; D’Angelo et al. 2008; Sukhija and Saboo, 2021) [21,22,23,24,25]. Research studies on warm-mix asphalt mixtures are carried out in different directions: from the research of the impact of the aggregate moisture and the possibility of saving energy (Yang et al. 2018) [26], the quantity of the exhaust gas emissions and the quantity of CO2 (Thives and Ghisi 2017; Sharma and Lee 2017; Autelitano et al. 2017; Li, K. et al. 2023) [27,28,29,30], the improvements of the technologies of execution (Kheradmand et al. 2014; Davidson 2008; Prowell et al. 2007, Nithinchary et al. 2024) [31,32,33,34], the research studies of different additives to mixtures (Abed et al. 2019; Guo et al. 2017; Dinis-Almeida and Afonso 2015; Oliveira et al. 2013; Caputo et al. 2020; Phan et al. 2024; de Sousa et al. 2023) [35,36,37,38,39,40,41] to the comparison of the characteristics and quality of warm-mix asphalt mixtures with hot mixtures (Capitao et al. 2012, Sol-Sánchez et al. 2016, Milad et al. 2022) [42,43,44] and the environmental and economic perspective of warm-mix asphalt mixtures (Rubio et al. 2013; Hassan 2009; Mazumder et al. 2016, Belc et al. 2021; Sukhija et al. 2022) [45,46,47,48,49]. Jenny (2009) [10] states that the reduction in the temperature of mixing during the production of an asphalt mixture from 180 °C to 115 °C leads to a reduction in the consumption of fuel by 1.5 kg per produced ton of the asphalt mixture. The temperature of the produced asphalt mixture is also significantly dependent on the distance of transport from the place of production to the place of installation, as well as the conditions of the base on which the same is installed. The load-bearing base with a higher moisture content in its composition on which the asphalt mixture is installed leads to a reduction in the temperature of the asphalt mixture which results in achieving an insufficient quality of the executed asphalt layer. Middleton (2008) [50] shows that during the production of warm-mix asphalt mixtures, savings of 24.20% are realized compared to the production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures. According to Zeumanis (2010) [51], savings due to production of warm-mix asphalt mixtures compared to the necessary used energy for production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures range from 5 to 18%. The authors You et al. (2008) [52] and Khandhal (2010) [53] point out the reduction in the energy consumption as being the most important advantage of warm-mix asphalt mixtures and state that the savings range in the amounts of 20 to 30%. According to the same authors, the application of warm-mix asphalt mixtures reduces the visible and invisible emissions in a similar amount, up to 30%, which is directly reflected on the air quality. Rubio et al. (2013) [45] compared the quantity of the exhaust gases and particles during the production of warm and hot-mix asphalt mixtures in the asphalt plant and during the execution and compacting of layers of asphalt mixtures. The results of the research showed that the production and installation of warm-mix asphalt mixtures is more environmentally friendly due to a considerable reduction in the content of CO2, by as much as 58% compared to the hot asphalt mixture.

The authors Costa and Benta (2015) [54] believe that the technologies of warm-mix asphalt mixtures are far from their full potential, mostly due to the costs of additives. In the study, they assess the potential economic and environmental advantages of the application of warm-mix asphalt mixtures. The results confirm that adequate warm-mix asphalt mixtures are economically more favorable and enable a considerable reduction in the energy consumption and, consequently, the reduction in the emissions of CO2. The comparison of the conditions of compacting of warm- and hot-mix asphalt mixtures was covered by the authors Kamarudin et al. (2018) [55]. They researched hot-mix asphalt mixtures and warm-mix asphalt mixtures, with the maximum grain size of the aggregate of 14 mm. The additive in the warm asphalt mixture was oil-based. During construction, the temperatures and density were measured, and the cooling speed and compactness level were analyzed. The results of the research showed that a warm asphalt mixture has a lower cooling rate, where the temperature of the mixture is reduced slowly but continuously. Also, it was demonstrated that a higher level of compactness is achieved in the case of warm-mix asphalt mixtures.

The authors Thives and Ghisi (2017) [27] presented a review of the literature concerning the energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions for the production of all types of road pavements. They pointed out that the use of warm mix technologies can reduce the energy consumption compared to hot asphalt mixes, mainly due to the reduction in the temperature of the mix production and placement, and the emissions are reduced as well. Warm-mix asphalt mixtures also impact the working conditions and offer a possibility of prolonging the construction season because, in colder months, the additives to a warm asphalt mixture facilitate compacting of the mixture, while the mixture itself cools down more slowly. The reduction in the temperature of the asphalt mixture production leads to better working conditions because of the smaller quantity of the exhaust gases and dust, which is particularly important on building sites such as tunnels where the ventilation conditions are worse.

Research studies of the ways of improving the equipment in asphalt plants were also conducted, all with the goal of reducing energy consumption and finding a more efficient production of asphalt mixtures. Thus, the authors Lin et al. (2022) [56] ascertained that the rotation speed of the drying drum affects the distribution of aggregate wrapping and the pressure in the drum, which consequently affects the stability of the flame in the drum. By reducing the drum rotation speed, a more even distribution of aggregate wrapping occurs, and thereby also an increase in the utilization of heat. The research found that, during the aggregate dryer performance of 80 t/h and a rotation speed of 6.2 rpm, the drying temperature of the aggregate is the highest, and the thermal efficiency of the aggregate drying drum is the best. In the paper by the authors Cimbola et al. (2016) [57], the current situation in Croatian asphalt plants was analyzed, and it was found that the segments of energy conversion and use still do not use the technical and the technological innovations in the field. The content of the aggregate moisture and the lack of regulated and covered storage sites executed with a minimum inclination is a problem in almost all asphalt plants in Croatia.

3. Experimental Research Studies

As was already pointed out in the introductory part of the paper, for the reduction in the aggregate moisture in the production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures, the thermal potential of the exhaust gases can be used. The process of pre-drying the aggregate using the hot exhaust gases would be carried out on a belt dryer which would be situated before the rotary drum for drying the aggregate. In the dryer itself, pre-drying of the aggregate in a specific time, at a specific temperature and specific air flow speed would be enabled at several levels. To determine the effect of different temperatures and air flow speeds, and different drying times on the reduction in the moisture, a laboratory model of a dryer was conceived and made. Tests of the moisture loss of different aggregate fractions 0/2, 2/4, 4/8, 8/11 from the total (natural) moisture of the aggregate were carried out, specifically for different combinations of the drying parameters. The tests were carried out on the premises of the laboratory Motičnjak (Varaždin) of the company COLAS Hrvatska d.d. The samples of stone materials were taken at the uncovered storage site of the asphalt plant Motičnjak, of the company COLAS Hrvatska d.d. (Figure 1). Stone materials of fraction sizes 0/2, 2/4, 4/8 and 8/11 were sampled. The origin of the stone aggregate is the quarry Špica (dolomite stone) and Hruškovec (eruptive stone) of the company Kaming d.d. All the aggregates were sampled on the same day. The samples of the stone material fractions sampled from the storage site of the asphalt plant were delivered to the laboratory with the natural moisture existing at the moment of sampling (3.07% for fraction 0/2, 3.31% for fraction 2/4, 2.1% for fraction 4/8 and 1.03% for fraction 8/11).

Figure 1.

Storage sites of stone materials (asphalt plant Motičnjak, COLAS Hrvatska d.d.).

3.1. Methodology

Within this research, laboratory tests were carried out with the aim of determining the percentage of the reduction in moisture of different aggregate fractions compared to the initial moisture of the fractions that are used as the raw material in the production of asphalt mixtures. Determining the moisture of a material is defined by the standard HRN EN 1097-5:2008 Tests for the mechanical and physical properties of aggregates—Part 5: Determination of the water content by drying in a ventilated oven (EN 1097-5:2008) [58], according to which the water content is determined by drying the stone materials at a controlled temperature of 110 °C for a duration of 24 h and the possibility of drying up to the constant mass, which designates the change in the mass in the time of one hour which does not differ by more than 0.1%. The aggregate moisture removed by drying (in the percentage of the total mass) is calculated according to Equation (1):

where

w = (M1 − M2)/M2 × 100 [%]

- w is material moisture [%],

- M1 is moist material mass [kg],

- M2 is dry material mass [kg].

3.2. Sampling and Preparation of Samples

The samples of particular fractions of the stone aggregate (0/2, 2/4, 4/8, 8/11), with approximately the same mass, were taken from different places at different levels, distributed throughout the whole storage site. During the selection of the sites and the number of particular samples, the way of forming a storage site, its shape and the segregation possibility were considered. In order to enable sampling from the interior of the storage site, a loader was used by which a storage site for sampling was formed by a specific number of interventions, after which particular samples were taken by a shovel from randomly selected places throughout the whole newly formed storage site according to HRN EN 932-1:2003 Tests for general properties of aggregates—Part 1: Methods for sampling (EN 932-1:1996) [59]. The material used in fractions 0/2, 4/8, 8/11 is of sedimentary origin and carbonate composition, declared according to simplified petrographic composition (HRN EN 932-3:2022 Tests for general properties of aggregates—Part 3: Procedure and terminology for simplified petrographic description (EN 932-3:2022) [60]) as dolomitic limestone. The density of fraction 0/2 saturated surface dry was ρssd = 2.69 Mg/m3, and water absorption was 0.8%. The density of fraction 4/8 saturated surface dry was ρssd = 2.70 Mg/m3, and water absorption was 0.6%. The density of fraction 8/11 saturated surface dry was ρssd = 2.71 Mg/m3, and water absorption was 0.6%. Fraction 2/4 is of eruptive origin and magmatic composition, declared according to simplified petrographic composition as diabase. The density of fraction 2/4 saturated surface dry was ρssd = 2.81 Mg/m3, and the water absorption was 1.3%.

3.3. Determining the Mass of Test Samples

The mass of the test samples was selected on the basis of the actual passages of the stone material on the inclined conveyor belt by which the material is delivered to the rotary drum. Figure 2 shows the inclined conveyor belt by which the stone material is delivered to the rotary drum.

Figure 2.

An inclined conveyor belt with the material (source: the authors).

The cross section of the inclined conveyor belt is open with an oval shape with a width of 70 cm and height of 8 cm. During the maximum operating capacity of the asphalt plant, the belt bears the load of the material in the width of approx. 50 cm and a thickness of 6 cm. To calculate the mass of the samples, the average value of the belt width of 50 cm and the average thickness of the poured layer of the stone material fractions of 3 cm were taken. In that case, the surface of the layer for a linear meter amount to 50 m2, and the volume to 0.015 m3. Since the pouring density of the stone material fraction with the size 0/4 mm amounts to approx. 1.7 t/m3, we obtain the corresponding mass of 25.5 kg of fraction 0/4. The pouring density of the stone material fraction with the size 4/8 mm amounts to approx. 1.4 t/m3, which gives the mass of 21.0 kg of the sample. In the same way, the mass of the sample for fraction 8/11 can also be determined. Based on the recipe for the asphalt mixture of the wearing course AC 11 surf with the ratio of fractions 0/4—40% and 4/8 and 8/11, 30% each, it arises that approx. 45.6 kg of the stone mixture comes on 1 m2 of the belt.

The laboratory sample formed in the dish has the dimensions 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.03 m, so it can be concluded that the laboratory sample will have a volume of 0.003 m3, i.e., 510 g. The mass of the fraction samples which are present in the recipe for the mixing of an asphalt mixture in a smaller percentage was reduced to 400 g. Since the thickness of the layer has a considerable impact during the drying of the aggregate, for the needs of model testing (in a dryer), the thickness of the stone material layer of 3 cm was defined.

3.4. Laboratory Equipment and Resources

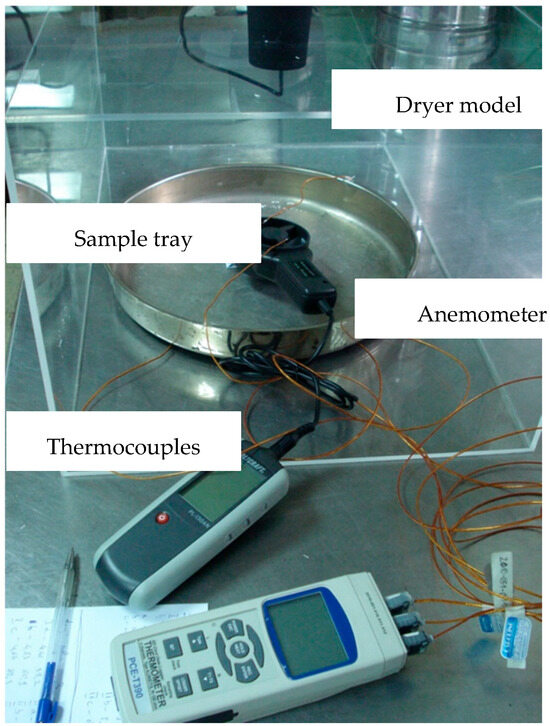

For the purpose of researching the reduction in moisture of the stone material, a laboratory model of a belt dryer (chamber with a cover) was conceived and made (Figure 3). For carrying out the tests, the following basic equipment was used:

- -

- a laboratory model of a dryer (chamber with a cover made of plexiglass with the dimensions of 40 × 50 × 60 cm; one side has a door at which the samples are placed; at the top, there is an opening with the diameter of 6.5 cm to which the drying device is connected);

- -

- a drying device which can control the air flow speed from 3.86 m/s to 6.32 m/s and the temperature ranging from 33 °C to 110 °C;

- -

- a stopwatch with the possibility of measuring from 0 to 86,400 s, with a resolution of 0.001 s and a measurement uncertainty of 0.15 s;

- -

- a ventilating dryer with temperature ranges from 20 °C to 200 °C;

- -

- the scales, with an accuracy of 0.1 g and a measurement uncertainty of 0.10 g;

- -

- a moisture measuring device;

- -

- the thermocouples, with a resolution of 0.1 °C and measurement uncertainty of 0.1 °C;

- -

- an anemometer with a resolution of 0.01 m/s, whose accuracy is 0.2 m/s.

Figure 3.

A laboratory model of a dryer (source: the authors).

3.5. Drying of Samples

The samples are placed in the laboratory model of a dryer to which the drying device is connected (Figure 3). The concept of the drying device is such that three basic temperatures (33.1 °C, 50.4 °C and 71.7 °C) and three basic air flow speeds (3.86 m/s, 4.53 m/s and 5.94 m/s) can be controlled (Table 1). The basic temperatures are taken from the usual regime of operation in an asphalt plant in the production of a bitumen mixture where the temperature of 33.1 °C is taken as the minimum possible, while others are based on the possibilities of the laboratory model. During the preparation of the test equipment, the following ranges of input parameters of temperatures and air flow speeds were determined.

Table 1.

The input parameters of the laboratory model of a dryer.

The test was carried out using the following steps:

- For each separate sample of stone material with a specific fraction and with natural moisture, the mass was determined by weighing before testing (Figure 4).

- After weighing, the sample was placed into the laboratory model of a dryer (Figure 5).

- The drying device was connected to the chamber cover and set to the specific air flow speed and temperature. The sample was exposed to the temperature and air flow speed for a duration of 30 s.

- After the expiry of 30 s, the device was turned off, and the sample was placed on the scales and its mass was read.

- The next sample with the same fraction is taken and its mass is determined before weighing; it is examined under the same conditions of air flow speed and the corresponding temperature but the time of the sample exposure is 45 s, and subsequently, the mass of the sample is determined again.

- Another sample with the same fraction is examined under the same conditions of air flow speed and the corresponding temperature, but the time of the sample exposure is 60 s.

- The percentage of the reduction in the moisture is calculated according to the expression (1).

Figure 4.

Determining the mass of the sample before testing by weighing.

Figure 5.

The sample in the chamber.

4. Results

For the defined temperatures and durations of drying and different air flow speeds, the results of the losses of moisture of particular aggregate fractions were obtained. The reduced moisture values were compared with the natural moisture of the corresponding aggregate fractions. The aggregate natural moisture was different depending on the aggregate fraction and it ranged from 1.03 to 3.31% (Table 2). The results of the moisture loss of the aggregate due to different parameters of drying (the duration and the drying temperature, the air flow speed) for the aggregate fractions 0/2, 2/4, 4/8 and 8/11 are shown in Table 2. The declared density of the fractions and water absorption is determined according to HRN EN 1097-6:2013 Tests for mechanical and physical properties of aggregates—Part 6: Determination of particle density and water absorption (EN 1097-6:2013 [61]).

Table 2.

The results of the moisture loss of different aggregate fractions.

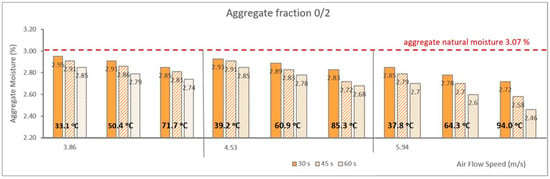

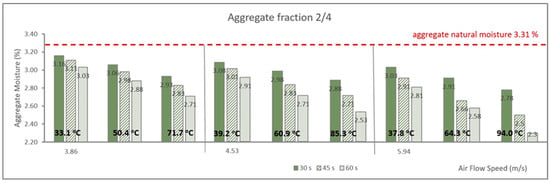

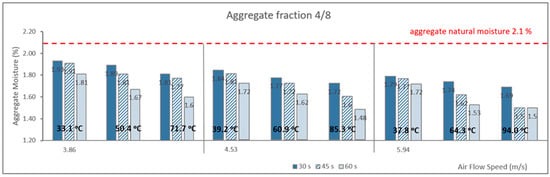

It is evident from Table 2. that, for different aggregate fractions, the ranges of the value of moisture loss are considerably different and that they depend on the parameters of drying (the temperature and the duration of drying, the air flow speed) and the aggregate natural moisture. The moisture of the aggregate fractions remaining after drying is shown in diagrams in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 6.

The reduced aggregate moisture values of fraction 0/2 for different temperatures and drying times and different air flow speeds.

Figure 7.

The reduction in the aggregate moisture of fraction 2/4 for different temperatures and times of drying and different air flow speeds.

Figure 8.

The reduction in the aggregate moisture of fraction 4/8 for different temperatures and times of drying and different air flow speeds.

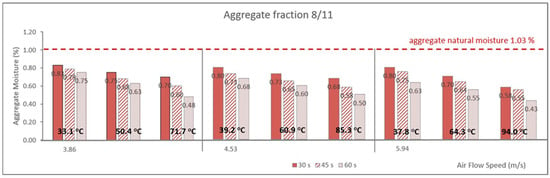

Figure 9.

The reduced moisture values of the aggregate fraction 8/11 for different temperatures and times of drying and different air flow speeds.

In the diagram in Figure 6, the results of the aggregate moisture of fraction 0/2 after drying are shown, for different temperatures and times of drying and different air flow speeds. For each air flow speed, the results of different temperatures are shown, from the lowest to the highest (e.g., for the speed of 3.86 m/s, three sets of data are shown, arranged from left to right, in order from the lowest temperature of 33.1 °C to the highest of 71.7 °C). From the results shown, it is clearly seen that the aggregate moisture after drying compared to its natural moisture depends on several factors: on the air flow speed, on the temperature and the duration of drying. The greater the air flow speeds and temperatures are, as well as the time of drying of an aggregate fraction, the lower the aggregate moisture.

The moisture loss of fraction 0/2 is lower for a lower air flow speed (3.86 m/s) than it is for higher speeds, while the greatest aggregate moisture loss was noticed for the air flow speed of 5.94 m/s. The moisture of fraction 0/2 thus ranges from 2.74% to 2.95% for the speed of 3.86 m/s, 2.68% to 2.93% for the speed of 4.53 m/s and 2.46% to 2.85% for the speed of 5.94%. As expected, the same trend of behavior is noticed for all the times of duration of drying, from 30 to 60 s, regardless of the temperature or speed of drying—with the prolongation of the drying time, the moisture loss is more intense. If the obtained results for the speed of 3.86 m/s and the temperature of 33.1 °C are analyzed, it can be seen that the percentage of the moisture reduction compared to the natural moisture is greater for the time of 45 s (−5.2%), and 60 s (−7.1%) compared to the time of 30 s (−3.9%). The results of the percentage of the moisture reduction for all the analyzed speeds and temperatures of drying are similar. The overall results of the percentage of the moisture reduction compared to the natural moisture of all the aggregate fractions are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences in % of the moisture reduction compared to the aggregate natural moisture.

With an increase in the drying temperature, the aggregate moisture loss is more intense. The highest percentage of moisture reduction in fraction 0/2 compared to the natural moisture is noticed for the drying temperature of 94 °C, and it ranges from −11.4 to −19.8%. In comparison with that, for the lowest drying temperature of 33.1 °C, the percentage of the moisture reduction ranges from −3.9 to −7.1%. For all the results and analyzed parameters of fraction 0/2, the trend of behavior is evident in the diagram in Figure 6 above, and the percentage of the moisture reduction compared to the aggregate natural moisture in Table 3.

Figure 7 shows the results of the reduced aggregate moisture of fraction 2/4 for different temperatures and times of drying and different air flow speeds. The natural moisture of fraction 2/4 amounted to 3.31%.

In the diagram in Figure 7, the same trend of behavior of the aggregate moisture is noticed; the higher the air flow speeds and temperatures are and the longer the drying time of the aggregate fraction is, the lower the aggregate moisture is. With an increase in the air flow speed (the speeds of 3.86 m/s, 4.53 m/s, 5.94 m/s), the moisture loss is greater. Thus, the reduced moisture of fraction 2/4 ranges from 2.71% to 3.16% for the speed of 3.86 m/s; 2.53% to 3.08% for the speed of 4.53 m/s and 2.30% to 3.03% for the air flow speed of 5.94 m/s. The aggregate moisture loss is more intense with the prolongation of the drying time (30 s, 45 s, 60 s), and it is particularly noticed for the highest drying temperature of 94 °C where the reduced moisture of fraction 2/4 ranges from 2.3% to 2.78%, and the percentage of the moisture reduction compared to the natural moisture ranges from −16% to −30.5% (Table 3).

Figure 8 shows the results of the reduced aggregate moisture of fraction 4/8, the natural moisture of which was 2.10%. With an increase in the air flow speed, the moisture loss is greater; thus, the reduced moisture of fraction 4/8 ranges from 1.60% to 1.93% for the speeds of 3.86 m/s; from 1.48% to 1.84% for the speeds of 4.53 m/s and from 1.50% to 1.79% for the air flow speeds of 5.94 m/s. The prolongation of the drying time (30 s, 45 s, 60 s) will intensify the aggregate moisture loss so that, for example, for the speed of 3.86 m/s and the temperature of 33.1 °C, the reduced moisture values are 1.93% (for 30 s), 1.91% (45 s) and 1.81% (60 s). For the same air flow speed and the temperature of 50.4 °C, the reduced moisture values range from 1.89% (for 30 s), 1.81% (45 s) and 1.67% (60 s), and for the temperature of 71.7 °C, they range from 1.81% (for 30 s), 1.77% (45 s) and 1.6% (60 s). The higher the air flow temperature is, the greater the moisture loss is during the drying of the aggregate. Thus, it can be seen from Table 4 that the percentages of the moisture reduction compared to the aggregate natural moisture are the greatest for the highest temperature (94.0 °C) and range from −19.5 to −28.5%.

Table 4.

The correlation of the relationship of the moisture loss and the drying time.

Figure 9 shows the results of the reduced aggregate moisture of fraction 8/11, the natural moisture of which amounted to 1.03% for different speeds of drying, temperature and duration of drying.

The reduced moisture of fraction 8/11 ranges from 0.48% to 0.83% for the speeds of 3.86 m/s; from 0.50% to 0.80% for the speeds of 4.53 m/s and from 0.43% to 0.80% for the speeds of drying of 5.94 m/s. A more significant aggregate moisture loss during drying is noticed for higher drying temperatures, and the differences in the percentage of the moisture reduction compared to the natural moisture (Table 4) show that the percentages of the reduction range from −43.6 to −58.2% (for 94.0 °C), from −33.9 to 51.4% (for 85.3 °C) and from −32.0 to −53.3% (for 71.7 °C).

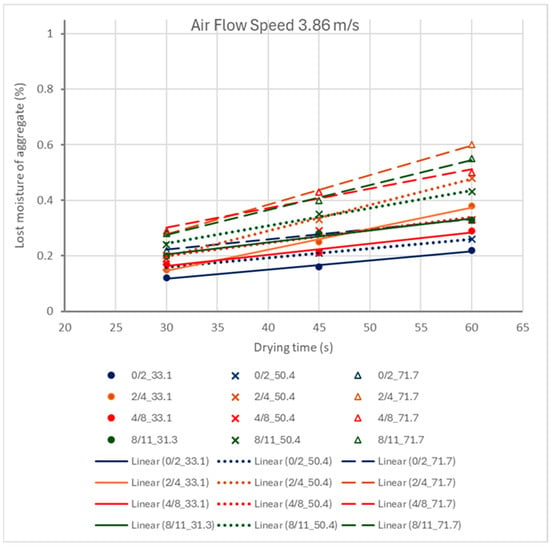

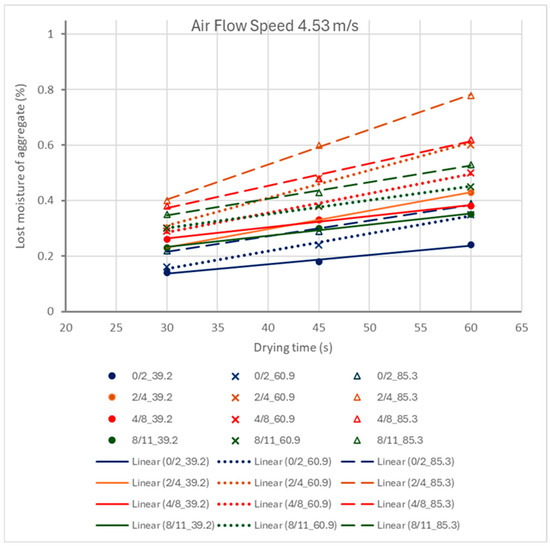

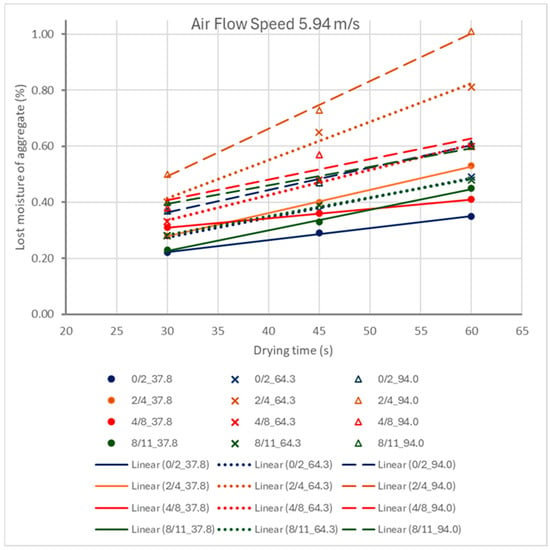

In order to see the relationship of the moisture loss and the drying time of particular aggregate fractions as clearly as possible, for all the speeds of aggregate drying, diagrams were made, from which the mentioned relationships are evident (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12) and the associated linear regression. Along with each linear regression, i.e., the result of the moisture loss, the designation of the aggregate fraction and the temperature of drying is placed. Thus, for example, the designation 0/2_33.1 represents the result of the finest observed fraction 0/2 for the drying temperature of 33.1 °C, for different air flow speeds.

Figure 10.

The relationship of the aggregate moisture loss and the drying time for the air flow speed of 3.86 m/s.

Figure 11.

The relationship of the aggregate moisture loss and the drying time for the air flow speed of 4.53 m/s.

Figure 12.

The relationship of the aggregate moisture loss and the drying time for the air flow speed of 5.94 m/s.

If all the three diagrams are compared, an ascending trend of the moisture loss at the same temperature is noticed, and a specific behavior of the moisture loss with an increase in the temperature, for different aggregate fractions. For the air flow speed of 3.86 m/s, that loss is somewhat slower than it is noticeable for the speed of 4.53 m/s, and particularly for the speed of 5.94 m/s, when the moisture loss for different drying times is expressed in large values.

By the analysis of the results, particular behavior is noticed during drying of the aggregate fraction 2/4 compared to other fractions, for which the moisture loss is the greatest, regardless of what air flow speed was in question.

The relationship of the aggregate moisture loss and the drying time of a particular aggregate fraction was observed by a linear model:

y = ax + b

The results of the linear regression and the coefficient of determination R2 are evident in Table 4, and they indicate a very strong connection between the aggregate moisture loss and the duration of the drying time. The coefficients of determination move in the range from R2 = 0.96 to R2 = 1.0. The only exception, i.e., lower value than the stated range of the coefficient of determination values was noticed for fraction 4/8 and the drying temperature of 94.0 °C and it is R2 = 0.8501.

The relationship between aggregate moisture loss and drying time described by the equations in Table 4 can be confirmed by numerical simulation and compared with the results obtained from experimental research presented in Table 3. For example, for fraction 0/2, air flow speed of 3.86 m/s, and drying temperature of 33.1 °C for a drying time of 30 s, the moisture loss according to the expression y = 0.0033x + 0.0167 is 0.1157% (experimental value is 0.12%). For the same fraction, the same air flow speed, drying temperature of 50.4 °C, and drying time of 30 s the moisture loss according to the expression y = 0.0033x + 0.06 is 0.159% (experimental value is 0,16%). For the same fraction, the same air flow speed, drying temperature of 71.7 °C, and drying time of 30 s the moisture loss according to the expression y = 0.0037x + 0.1117 is 0.2227% (experimental value is 0.22%).

The research on aggregate pre-drying in hot-mix asphalt production is framed within environmental, material, operational, and energy-related context. Environmental factors such as climate, stockpile exposure, and seasonal moisture determine initial drying requirements, while aggregate characteristics including mineralogy, porosity, gradation, and moisture retention govern heat transfer and drying process behavior. These factors interact with the operational context of the asphalt plant, including pre-dryer design, burner efficiency, airflow patterns and stockpile management practices. Energy consumption and emission regulations shape the boundaries of feasible drying strategies. The framework links technical and environmental conditions with economic and sustainability outcomes, providing a holistic basis for evaluating and improving aggregate pre-drying processes.

5. Conclusions

In this research, the intention was to determine the impact of different drying parameters on the moisture loss of the aggregate which is used in production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures. The parameters of drying which were analyzed and observed in different combinations are: the air flow speed, the drying temperature and the drying time of the aggregate. On the basis of the results obtained, it is possible to conclude the following:

- (1)

- The air flow speed was 3.86 m/s, 4.53 m/s and 5.94 m/s. It was noticed that there was a smaller moisture loss of fractions for a lower air flow speed (3.86 m/s) than there was for higher speeds, while the highest aggregate moisture loss was noticed for the air flow speed of 5.94 m/s. During the tests, an unwanted effect was also noticed on the smallest fraction 0/2, during high air flow speeds, the lifting of small particles occurs (a part of the stone dust within the fraction) and consequently, the loss of the mass. For that reason, it is important to control the air flow speed.

- (2)

- The drying temperature is the next important factor which directly affects the reduction in the aggregate moisture; the higher the air flow temperature is, the more significant is the moisture loss during drying of the aggregate. The aggregate that comes from the belt dryer from pre-drying, besides having a reduced moisture, is already heated to an adequate temperature, and a shorter time of drying and heating of the aggregate in the rotary drum will be necessary. By doing that, the expenses of energy products for powering the rotary drum can be reduced because it should not be forgotten that the temperature of the aggregate coming into the process of production is one of the factors affecting the reduction in energy during production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures.

- (3)

- The time of drying in the research was 30, 45 and 60 s. For all the times of the duration of drying, regardless of the drying temperature or speed, it is noticed that, with the prolongation of the drying time, the aggregate moisture loss becomes more intense. The time of drying can always be prolonged, which could ultimately, by the results shown from the tests carried out, prove that the moisture loss can be further accelerated and increased. The prolongation of the drying time could be realized in the belt dryer, which would have several levels, in which the aggregate would “travel” on the conveyor belt longer.

- (4)

- The relationship of the moisture loss and of the drying time of a particular aggregate fraction was observed by the linear model y = ax + b. The results of the linear regression and the coefficient of determination R2 indicate a very firm connection between the loss of the aggregate moisture and the duration of the drying time. The coefficients of determination range from R2 = 0.96 to R2 = 1.0. From the obtained equations, it is possible to calculate the reduction in the aggregate moisture for different lengths of drying duration and different drying temperatures.

The increasingly stringent environmental requirements, as well as the tendency to realize significant savings of energy products in production processes prompted a deeper analysis of the existing situation of production in stationary asphalt plants. Numerous researchers conducted research studies of possible preheating of the stone aggregate and the reduction in its moisture in the process of production of hot-mix asphalt mixtures, by which it is possible to reduce the expenses of energy products for heating and drying of the aggregate in the rotary drum.

Laboratory dryers, ovens, and heating systems often cannot fully replicate the thermal conditions of industrial asphalt plants. Temperature uniformity, heat transfer rate, and aggregate flow conditions differ substantially. Experimental findings may not scale up accurately to real production conditions. Control measurements of the adhesion of aggregates and bitumen should be carried out to determine whether exhaust gases have a noticeable effect on the bonding of bitumen to the aggregate. The measurements should also include possible variations that occur in real operating conditions of the asphalt base, such as changes in exhaust gas composition, temperature fluctuations or variations in particle concentration.

The research presented in this paper aimed to determine the influence of moisture reduction parameters for different aggregate fractions used in the production of hot asphalt mixtures, using a laboratory model of a dryer. This research represents the initial step in establishing the starting conditions for further studies to be conducted under real conditions at an asphalt plant. To conduct such research, it is necessary to modify the asphalt plant by installing a belt dryer before the rotary drum used for drying aggregates. The input parameters for designing such a belt dryer require prior model testing, some of which are described in this paper. The test methods used are standardized and conducted in the laboratory on the asphalt plant itself. As the objective was to develop guidelines for constructing a full-scale belt dryer, the methods commonly used in practice were applied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. Z.D.-A. and S.D.; methodology. Z.C.; software. S.D. and Z.C.; validation. Z.D.-A. and T.R.; formal analysis. S.D.; investigation. Z.C.; resources. Z.C.; data curation. Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation. Z.D.-A. and S.D.; writing—review and editing. T.R.; visualization. Z.D.-A. and S.D.; supervision. T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zdravko Cimbola was employed by COLAS Hrvatska d.d. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Environmental Guidelines on Best Available Techniques (BAT) for the Production of Asphalt Paving Mixes, European Asphalt Pavement Association, EAPA. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Environmental-Guidelines-on-Best-Available-(-BAT-)/7701ef8c7f55da75e9a73774b303747b876d4c20 (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- Chappat, M.; Bilal, J. The Environmental Road of the Future: Life Cycle Analysis, Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Colas Group. 2003. Available online: https://fr.scribd.com/document/347273608/Route-Futur (accessed on 12 May 2017).

- Ang, B.; Fwa, T.; Ng, T. Analysis of process energy use of asphalt-mixing plants. Energy 1993, 18, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budin, R.; Mihelić-Bogdanić, A. Izvori i Gospodarenje Energijom u Industriji; Element d.o.o.: Zagreb, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atmaja, A.S.; Setyawan, A.; Pranolo, S.H. Djumari, The Use of Energy in The Production Process of Hot Mix Asphalt in Asphalt Mixing Plant (AMP). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1912, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullien, A.; Gaudefroy, V.; Ventura, A.; de la Roche, C.; Paranhos, R.; Monéron, P. Airborne Emissions Assessment of Hot Asphalt Mixing—Methods and Limitations. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2010, 11, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.J. Energy Conservation at the Plant Makes Sense and Saves, Hot Mix Asphalt Technology. 2008. Available online: https://www.hotmixproduction.com/objects/Energy%20conservation%20at%20the%20plant.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Grabowski, W.; Janowski, L. Issues of Energy Consumption during Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) Production. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference “Modern Building Materials, Structures and Techniques”: Selected Papers, Vilnius, Lithuania, 19–21 May 2010; Technika: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2010; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, W.; Janowski, L.; Wilanowicz, J. Problems of energy reduction during the hot-mix asphalt production. Balt. J. Road Bridg. Eng. 2013, 8, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, R. CO2 Reduction on Asphalt Mixing Plants Potential and Practical Solutions; Amman-Group: Langenthal, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sivilevicius, H. Application of Expert Evaluation Method to Determine the Importance of Operating Asphalt Mixing Plant Quality Criteria and Rank Correlation. Balt. J. Road Bridg. Eng. 2011, 6, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, D.; de Vega, M.; García-Hernando, N.; Marugán-Cruz, C. Energy and exergy analysis in an asphalt plant’s rotary dryer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androjić, I.; Dolaček-Alduk, Z.; Dimter, S.; Rukavina, T. Analysis of impact of aggregate moisture content on energy demand during the production of hot mix asphalt (HMA). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androjić, I.; Dolaček-Alduk, Z. Analysis of energy consumption in the production of hot mix asphalt (batch mix plant). Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 43, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androjić, I. Model Optimalizacije Utroška Energenata u Procesu Proizvodnje Vrućih Asfaltnih Mješavina na Asfaltnim Postrojenjima Cikličnog Tipa. Ph.D. Theis, Faculty of Civil Engineering Osijek, Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Osijek, Croatia; 244p. (In Croatian).

- Simons, Technical Paper T-129: Stockpiles, Astec Industries. pp. 1–18. Available online: https://cdn.base.parameter1.com/files/base/acbm/mixequipmentmag/document/2020/01/T_129_Stockpiles.5e335df975959.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Androjić, I.; Kaluđer, G. Usage of solar aggregate stockpiles in the production of hot mix asphalt. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 108, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androjić, I.; Marović, I.; Kaluđer, G.; Androjić, J. Application of solar aggregate stockpiles in the process of storing recycled materials. Int. J. Energy Res. 2018, 57, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbola, Z.; Dolaček-Alduk, Z. Managing Thermal Energy of Exhaust Gases in the Production of Asphalt Mixtures. Teh. Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 2018, 25, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, J.; Fang, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, H.; Lv, N. Energy Consumption Analysis and Prediction of Hot Mix Asphalt. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 490, 032029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Julaganti, A. Warm mix asphalt: Paves way for energy saving. Recent Res. Sci. Technol. 2014, 6, 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, M.C.; Martínez, G.; Baena, L.; Moreno, F. Warm mix asphalt: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkus, A.; Čygas, D.; Laurinavičius, A.; Perveneckas, Z. Analysis and evaluation of possibilities for the use of warm mix asphalt in Lithuania. Balt. J. Road Bridg. Eng. 2009, 4, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, J.; Harm, E.; Bartoszek, J.; Baumgardner, G.; Corrigan, M.; Cowsert, J.; Harman, T.; Jamshidi, M.; Jones, W.; Newcomb, D.; et al. Warm-Mix Asphalt: European Practice. Technical Report No. FHWA-PL-08-007; Office of International Programs, Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: https://international.fhwa.dot.gov/pubs/pl08007/pl08007.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Sukhija, M.; Saboo, N. A comprehensive review of warm mix asphalt mixtures-laboratory to field. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 274, 121781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-H.; Rachman, F.; Susanto, H.A. Effect of moisture in aggregate on adhesive properties of warm-mix asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thives, L.P.; Ghisi, E. Asphalt mixtures emission and energy consumption: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lee, B.-K. Energy savings and reduction of CO2 emission using Ca(OH)2 incorporated zeolite as an additive for warm and hot mix asphalt production. Energy 2017, 136, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autelitano, F.; Bianchi, F.; Giuliani, F. Airborne emissions of asphalt/wax blends for warm mix asphalt production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yan, X.; Pu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fang, K.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y. Quantitative evaluation on the energy saving and emission reduction characteristics of warm mix asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 407, 133465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheradmand, B.; Muniandy, R.; Hua, L.T.; Yunus, R.; Solouki, A. An overview of the emerging warm mix asphalt technology. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2013, 15, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.K. Warm asphalt mix technology, an overview of the process in Canada. In Proceedings of the 2008 Annual Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada, 21–24 September 2008; Polyscience Publications Inc.: Laval, QC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prowell, B.D.; Hurley, G.C.; Crews, E. Field performance of warm-mix asphalt at national center for asphalt technology test track. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2007, 1998, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithinchary, J.; Dhandapani, B.P.; Mullapudi, R.S. Application of warm mix technology—Design and performance characteristics: Review and way forward. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 414, 134915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Thom, N.; Grenfell, J. A novel approach for rational determination of warm mix asphalt production temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 200, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; You, Z.; Tan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Performance evaluation of warm mix asphalt containing reclaimed asphalt mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2017, 18, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis-Almeida, M.; Afonso, M.L. Warm Mix Recycled Asphalt e a sustainable solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.R.M.; Silva, H.M.R.D.; Abreu, L.P.F.; Fernades, S.R.M. Use of a warm mix asphalt additive to reduce the production temperatures to improve the performance of asphalt rubber mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, P.; Abe, A.A.; Loise, V.; Porto, M.; Calandra, P.; Angelico, R.; Oliviero Rossi, C. The Role of Additives in Warm Mix Asphalt Technology: An Insight into Their Mechanisms of Improving an Emerging Technology. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.M.; Choi, Y.S.; Youn, S.H.; Park, D.W. Effect of synthesized warm mix additive and rejuvenator on performance of recycled warm asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 421, 135772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, T.M.; de Medeiros Melo Neto, O.; de Figueiredo Lopes Lucena, A.E.; Nóbrega, E.R. Enhancing workability and sustainability of asphalt mixtures: Investigating the performance of beeswax as a novel additive for warm mix asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 405, 133306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitao, S.D.; Picado-Santos, L.G.; Martinho, F. Pavement engineering materials: Review on the use of warm-mix asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol-Sánchez, M.; Moreno-Navarro, F.; García-Travé, G.; Rubio-Gámez, M.C. Analyzing industrial manufacturing in-plant and in-service performance of asphalt mixtures cleaner technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, A.; Babalghaith, A.M.; Al-Sabaeei, A.M.; Dulaimi, A.; Ali, A.; Reddy, S.S.; Bilema, M.; Yusoff, N.I.M. A Comparative Review of Hot and Warm Mix Asphalt Technologies from Environmental and Economic Perspectives: Towards a Sustainable Asphalt Pavement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.C.; Moreno, F.; Martinez-Echevarria, M.J.; Vazquez, J.M. Comparative analysis of emissions from manufacture and use of hot and half-warm mix asphalt. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. Life-cycle assessment of warm-mix asphalt: An environmental and economic perspective. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 88th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 January 2009; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, M.; Sriraman, V.; Kim, H.H.; Lee, S.J. Quantifying the environmental burdens of the hot mix asphalt (HMA) pavements and the production of warm mix asphalt (WMA). Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2016, 9, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belc, A.L.; Ciutina, A.; Buzatu, R.; Belc, F.; Costescu, C. Environmental Impact Assessment of Different Warm Mix Asphalts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhija, M.; Saboo, N.; Pani, A. Economic and environmental aspects of warm mix asphalt mixtures: A comparative analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 109, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, B.; Forfylow, B. An evaluation of warm mix asphalt produced with double barrel green process. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Managing Pavement Assets, Calgary, AB, Canada, 23–28 June 2008; Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/680665292/Asphalt-Pavement (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Zaumanis, M. Warm Mix Asphalt Investigation. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257528321_WARM_MIX_ASPHALT_INVESTIGATION#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- You, Z.; Goh, S. Laboratory Evaluation of Warm Mix Asphalt: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2008, 1, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Khandhal, P.S. Warm Mix Asphalt Technologies: An Overview. J. Indian Road Congr. 2010, 71, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.; Benta, A. Economic and environmental impact study of warm mix asphalt compared to hot mix asphalt. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 112, 2308–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, S.N.N.; Hainin, M.R.; Satar, M.K.I.M.; bin Mohd Warid, M.N. Comparison of Performance between Hot and Warm Mix Asphalt as Related to Compaction Design. IOP Conf. Ser. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1049, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Bao, M.; Li, H.; Yang, J. Characteristic simulation and working parameter optimization of the aggregate dryer. Dry. Technol. 2022, 4, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbola, Z.; Dolaček-Alduk, Z.; Dimter, S. Possibilities of energy savings in hot-mix asphalt production. In Road and Rail Infrastructure IV; Lakušić, S., Ed.; Department of Transportation, Faculty of Civil Engineering, University of Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016; pp. 667–673. [Google Scholar]

- HRN EN 1097-5:2008; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 5: Determination of the Water Content by Drying in a Ventilated Oven. Croatian Standards Institute (HZN): Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- HRN EN 932-1:2003; Tests for General Properties of Aggregates—Part 1: Methods for Samplin. Croatian Standards Institute (HZN): Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- HRN EN 932-3:2022; Tests for General Properties of Aggregates—Part 3: Procedure and Terminology for Simplified Petrographic Description. Croatian Standards Institute (HZN): Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- HRN EN 1097-6:2013; Tests for Mechanical And physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. Croatian Standards Institute (HZN): Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.