Abstract

Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) are gaining interest as environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional organic solvents in the functional food sector. Their low volatility, biodegradability, and tunable polarity, combined with high affinity for phenolics, carotenoids, and other phytochemicals, make them particularly relevant for developing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory ingredients at a time of rising diet-related chronic disease burden. This review critically analyses the role of NADES along the functional food chain. We summarize their composition, preparation, and key physicochemical properties, and then examine the NADES-based extraction of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds from plants and food by-products in comparison with traditional solvent systems. The influence of NADES on the stability and biological activity of recovered compounds is discussed, together with their use in the formulation, stabilization, and delivery strategies for functional foods. Emerging data indicate that NADES often enhance extraction yields and may protect labile bioactives, leading to stronger antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses in vitro compared with ethanol or water extracts when normalized to phenolic content. At the same time, large-scale implementation is limited by challenges related to safety assessment, regulatory acceptance, viscosity, and recovery issues, and incomplete techno-economic data. This review highlights these constraints, identifies key knowledge gaps, and outlines research priorities required to translate NADES-based processes into scalable, safe, and health-promoting functional food applications.

1. Introduction

Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) are a class of green liquid media formed when naturally occurring primary metabolites, such as organic acids, sugars, amino acids, and choline derivatives, are mixed in specific molar ratios that promote extensive hydrogen bonding and eutectic behavior [1,2]. Over the past decade, NADES have become increasingly relevant in food science and functional food research due to their non-volatility, low toxicity, biodegradability, and suitability as alternatives to hydroalcoholic or conventional organic solvents. These attributes position NADES as promising tools for the sustainable recovery of bioactive compounds from edible plants and agro-food residues [3,4,5]. Numerous studies now document the successful extraction of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, carotenoids, alkaloids, and other health-promoting metabolites from spent coffee grounds, fruit and vegetable by-products, cereal brans, and medicinal or aromatic plants [6,7,8,9]. In many cases, NADES not only increase extraction efficiency but also enhance selectivity toward target compounds, often outperforming ethanol- or water-based solvent systems.

Beyond acting as efficient extraction media, NADES also exhibit functional roles as stabilizing agents and carriers for bioactive molecules. An increasing evidence base shows that NADES can protect labile antioxidants, pigments, and other sensitive phytochemicals from degradation during processing and storage. This stabilization contributes to an enhancement of measured antioxidant capacity and, in some cases, the anti-inflammatory activity of the resulting extracts. Such improvements arise both from the preservation of unstable constituents and from the intrinsic antioxidant or synergistic effects of certain NADES matrices themselves [10,11,12]. As a consequence, NADES are now regarded not only as green extraction solvents but also as functional formulation components capable of supporting the integrity and activity of bioactives in complex food systems.

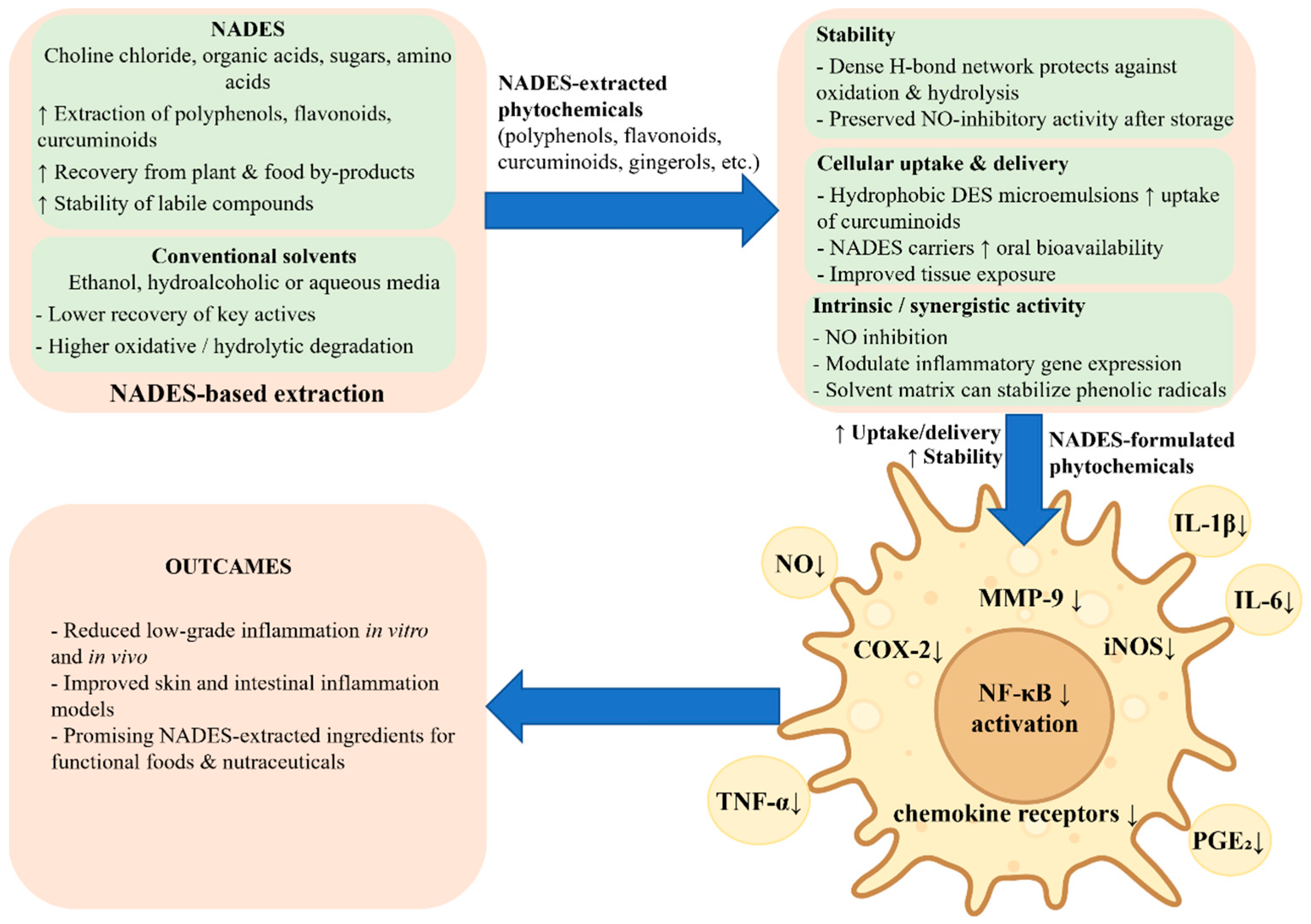

The rising prominence of NADES in the scientific community is reflected in global publication trends, as illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1a shows a marked and continuous increase in research output on both deep eutectic solvents (DES) and NADES from 2010 to 2025, with NADES gaining particular momentum in the last five years. This growth demonstrates the expanding recognition of NADES as versatile, sustainable tools across multiple research fields. Figure 1b highlights the geographical distribution of NADES research, revealing strong leadership by China and steadily increasing contributions from Europe, India, the United States, and other regions. This broad global engagement emphasizes the widespread relevance of NADES, both scientifically and industrially. Figure 1c illustrates the interdisciplinary nature of NADES research, with chemistry and chemical engineering dominating early developments and a growing presence in biotechnology, medicine, pharmacology, and environmental applications. Finally, Figure 1d presents a word cloud of recurring keywords in NADES publications, where terms such as “deep eutectic”, “solvent”, “extraction”, “green”, and “choline chloride” underscore the technology’s alignment with sustainable extraction, analytical science, and functional food development.

Figure 1.

Global research trends and scientific landscape of DES and NADES. (a) Annual number of publications on DES and NADES from 2010 to 2025, illustrating rapid growth in scientific interest, especially in the past decade. Data retrieved from Scopus (search terms: “natural deep eutectic solvent”; document types: articles and reviews; and search date: December 2025). (b) Leading countries contributing to NADES research, highlighting strong activity in China and growing participation across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. (c) Distribution of publications by field of knowledge, showing the dominance of chemistry and chemical engineering, with emerging relevance in food science, biotechnology, medicine, and environmental science. (d) Word cloud of research keywords associated with NADES, emphasizing core themes such as “deep eutectic”, “solvent”, “extraction”, “green”, and “choline chloride”, which reflect key application areas in green extraction and functional food science.

These trends are highly relevant for functional foods targeting oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation. Chronic inflammation and oxidative imbalance contribute to the progression of metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases, driving consumer and scientific interest in antioxidant- and anti-inflammatory-rich food ingredients. NADES enable the efficient valorization of plant materials and food processing by-products into extracts enriched in such health-promoting compounds, while their low environmental impact aligns with the principles of green and circular food production [3,6,7,8,9].

Although several recent reviews provide broad overviews of NADES composition, preparation, toxicity, and general applications for extracting or analyzing food bioactives [3,4,7,8], a dedicated synthesis focused on how NADES influence the bioactivity, and particularly the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, of the recovered compounds remains limited. Furthermore, the translation of NADES-based extracts into functional foods requires a deeper understanding of formulation strategies, safety considerations, and scale-up challenges.

This review aims to address these gaps with a specific emphasis on functional food applications. Section 2 discusses the use of NADES in the extraction of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory bioactives from plants and food by-products. Section 3 examines how NADES influence the resulting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities in comparison to conventional solvents. Section 4 analyses safety, regulatory considerations, scale-up issues, and industrial prospects. Section 5 identifies key challenges, unresolved questions, and future research directions for the integration of NADES into functional foods targeting oxidative stress and inflammation. Finally, Section 6 presents the conclusions of the review.

2. NADES in the Extraction of Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Bioactive Compounds

2.1. Extraction Efficiency and Mechanistic Advantages

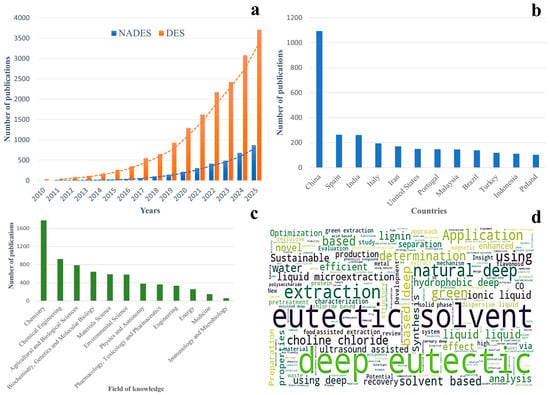

Extensive hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions appear in these mixtures. The melting point of the mixture becomes significantly lower than the melting points of the individual components, resulting in a liquid phase with high solvation capacity, tunable polarity, low volatility, and good thermal and chemical stability [5,8]. The design flexibility of NADES arises from the wide range of available hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs) and hydrogen bond donors (HBDs). Figure 2 illustrates this concept, showing typical HBA compounds, such as quaternary ammonium salts, choline chloride, acetylcholine, and betaine, alongside several classes of HBDs, including amino acids, amines, sugars, polyols, diols, and organic acids. Different combinations and molar ratios of these building blocks enable the fine-tuning of viscosity, polarity, acidity, and hydrogen bonding strength. This tuning allows for the selective solubilization and extraction of diverse phytochemicals from natural matrices [2,8,13].

Figure 2.

Representative HBAs and HBDs for the design of natural deep eutectic solvents. Schematic overview of typical hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), including quaternary ammonium cations, choline chloride, acetylcholine and betaine, and common hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) such as amino acids, amines, sugars, polyols, diols, and organic acids. By selecting and combining specific HBAs and HBDs, the physicochemical properties of NADES, including polarity, viscosity, and solvation capacity, can be tuned for targeted extraction of food-related bioactive compounds.

NADES efficiently extract many classes of phytochemicals, including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and carotenoids [7,14,15]. Their components form extensive hydrogen bonding networks together with additional π interactions and acid–base contacts. These interactions create a dense yet flexible microenvironment that stabilizes hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amino groups, while also interacting with hydrophobic aromatic rings [15,16].

This solvent structure facilitates the disruption of plant cell walls, thereby enhancing mass transfer. NADES penetrate polysaccharide and lignin-rich domains and promote swelling of the matrix. Microscopy and extraction studies on herbs, coffee by-products, and microalgae report partial disintegration of cell walls, higher leaching rates, and shorter optimal extraction times compared with aqueous ethanol or water [6,17,18].

NADES also provide strong solute–solvent interactions, broadening the solubility window. Choline chloride and sugar or polyol-based systems increase the solubility of many flavonoids and other poorly water-soluble phytochemicals by several orders of magnitude (Figure 2) [6,15]. The addition of controlled amounts of water adjusts viscosity, polarity, and conductivity and can improve mass transfer while preserving the hydrogen bonding network. These effects account for the frequent observation of higher extraction yields and stronger antioxidant capacity in NADES extracts compared to hydroalcoholic or purely organic solvents [14,16].

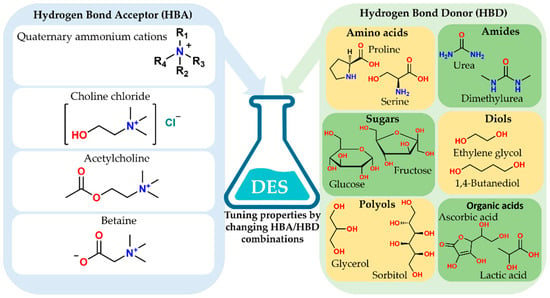

Selective extraction follows from the rational tuning of NADES composition. Variation in the HBA and HBD properties, as well as the water content, enables control over polarity, acidity, and viscosity (Figure 3). Systematic screening studies show that acidic NADES based on choline chloride with organic acids enrich phenolic acids and anthocyanins from plant tissues and food by-products and outperform ethanol or methanol mixtures in both total phenolic yield and antioxidant activity (Figure 3) [16,18,19]. Sugar and polyol-based NADES, including glucose with glycerol, show a high affinity for flavonoids and carotenoids, and support efficient recovery of pigments from fruit and vegetable by-products and from microalgae [7,20,21].

Figure 3.

Structural diversity of NADES: combinations of HBAs with HBD classes and their extraction applications. Schematic overview of common NADES systems formed by pairing different hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs) with representative hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), including sugars, polyols, organic acids, diols, fatty acids, betaine, and menthol. The figure highlights how specific HBA–HBD combinations determine solvent properties and extraction selectivity toward pigments, polyphenols, proteins, and fatty acids.

Comparative extraction studies confirm these mechanistic advantages across many matrices. A choline chloride with lactic acid NADES increased the total phenolic yield from hazelnut skin by about thirty-nine percent relative to an optimized conventional organic solvent system and gave higher individual phenolic acid and flavonoid concentrations [19]. The extraction of polyphenols from spent coffee grounds with choline chloride-based NADES produced higher levels of chlorogenic acids, stronger radical scavenging activity, and enhanced antimicrobial effects compared with hot water or aqueous ethanol [6]. The ultrasound-assisted NADES extraction of bioactives from date seeds and various fruit and vegetable by-products exhibits similar trends, consistently yielding higher total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity compared to conventional solvent extraction [7,16,18].

Hydrophilic and hydrophobic NADES also extend the accessible range of target molecules. Hydrophobic NADES based on fatty acids facilitate the efficient extraction and stabilization of carotenoids, such as beta-carotene, from pumpkin and other orange plant tissues, achieving high pigment recovery with good storage stability [20]. Glucose- and glycerol-based NADES recover phycocyanin, chlorophylls, and carotenoids from Spirulina with higher pigment yields, and preserve bioactivity compared to water extraction [21,22]. These examples illustrate the broad mechanistic space of NADES and support their use as highly efficient and tunable extraction media for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory bioactives.

2.2. Extraction from Plant Sources and Food By-Products

NADES are now used for extraction from various plant matrices relevant to functional foods. Studies report efficient recovery of phenolics, flavonoids, anthocyanins, stilbenes, carotenoids, and terpenoids from berries, citrus fruits, grapes, pomegranate, olives, leafy vegetables, spices, and medicinal herbs using choline chloride, organic acids, sugars, and polyols as NADES components [8,14,17,23,24].

Berries represent one of the most thoroughly investigated plant groups for NADES-based extraction. Blueberry peel, pomace, and leaves show particularly high recoveries of anthocyanins and other polyphenols when treated with NADES, especially in combination with ultrasound- or microwave-assisted techniques [25,26,27,28]. Comparable results have been reported for other pigment-rich fruits, including cranberry and pomegranate, where NADES facilitate the efficient extraction of anthocyanins and hydrolysable tannins under mild conditions [29,30,31].

A major field of application is the valorization of food processing by-products. Citrus peel and orange processing residues are rich in flavanones and polymethoxylated flavones. Deep eutectic and natural deep eutectic solvents efficiently recover these compounds from orange peel and related by-products, supporting integrated biorefinery schemes [32,33,34]. Grape pomace is another key matrix. Choline chloride–organic acid NADES provide high anthocyanin and phenolic contents from grape pomace and wine lees, and can be scaled up to at least several hundred milliliters in continuous or intensified processes [35,36].

Vegetable and leaf by-products also benefit from NADES extraction. NADES based on choline chloride and polyols or organic acids efficiently recover hydroxytyrosol, oleuropein, and flavonoids from olive leaves [37,38]. Ultrasound-assisted NADES extraction from tomato processing waste enables the simultaneous recovery of carotenoids and tocopherols, supporting the direct incorporation of the extract into formulations [39]. Spent coffee grounds and other beverage by-products supply additional polyphenol-rich streams, where betaine- or choline-based NADES match or exceed hydroalcoholic systems in extraction efficiency and bioactivity [6,40].

Cereal bran and other fibrous residues are emerging targets. Solid-state fermentation, followed by NADES extraction, increases the phenolic content in corn bran and improves the recovery of antioxidant phenolic acids from the fermented material [41]. Similar concepts apply to oat bran, rice bran, and nut shells, when fermentation or pretreatments open the cell wall network before NADES’ extraction. These approaches support circular economy strategies and reduce reliance on volatile organic solvents, while generating extracts rich in polyphenols, flavonols, anthocyanins, carotenoids, stilbenes, and terpenoids, which contribute both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions in prospective functional food applications [6,42,43].

2.3. Influence on Antioxidant Activity

Extracts obtained with NADES frequently exhibit high antioxidant capacity, as demonstrated by commonly applied in vitro assays, including 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC), and reducing power tests. These effects have been reported across a wide range of plant matrices and agri-food by-products, such as medicinal leaves, seeds, fruit pomaces, and berries [14,44,45,46]. In systems based on Pluchea indica leaves, Toona sinensis seeds, and blackthorn pomace, choline chloride-based NADES yielded extracts characterized by elevated total phenolic and flavonoid contents together with strong radical scavenging activity under optimized extraction conditions [44,45,46].

A consistent observation across many studies is the positive correlation between total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant capacity in NADES extracts. This relationship has been reported for diverse matrices, including Pluchea indica leaves, Toona sinensis seeds, blackthorn pomace, and various berries and aromatic plants [14,44,45,46,47]. In these systems, NADES enhance the solubility of phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavanols, often leading to more chemically diverse phenolic profiles. The broader recovery of redox-active compounds contributes substantially to the high DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and ORAC values frequently reported for NADES extracts.

Beyond extraction efficiency, the stabilization of labile antioxidant compounds during and after extraction represents an important contributor to overall antioxidant performance. Hydrophilic NADES composed of organic acids, sugars, or polyols can protect oxidation-sensitive molecules such as ascorbic acid, anthocyanins, and carotenoids during storage. Studies on orange peel extracts show that choline chloride-based NADES preserve phenolic compounds, ascorbic acid, and antioxidant capacity over extended storage periods [48]. Similar stabilization effects have been reported for carotenoid-rich matrices, including pumpkin and other vegetables, where NADES maintain pigment integrity over several months [14,49]. In the case of blueberry anthocyanins, multiple NADES formulations have been shown to sustain anthocyanin content and color stability during refrigerated storage [25,50]. This protective capacity helps conserve the native antioxidant potential of plant-derived extracts.

A further factor influencing antioxidant activity is the intrinsic and synergistic contribution of the NADES matrix itself. Certain NADES components, such as organic acids, amino acids, or polyols, possess reducing or radical scavenging properties that can contribute directly to the overall antioxidant response. Measurements performed on blank NADES systems and on phenolic compounds dissolved in NADES indicate that the solvent matrix may enhance antioxidant signals beyond simple additive effects [12,46,51]. In extracts derived from grape and coffee by-products, NADES formulations based on betaine or choline chloride display strong antioxidant activity even when phenolic contents are comparable, suggesting a role for solvent–solute interactions and matrix effects in modulating redox behavior [6,48].

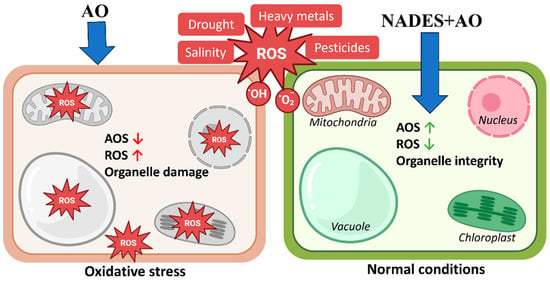

The mechanistic implications of these observations are summarized in Figure 4. NADES-based antioxidant formulations can modulate intracellular redox homeostasis at the organelle level. Under abiotic stress conditions, cells accumulate reactive oxygen species and exhibit reduced antioxidant system activity, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, vacuolar instability, chloroplast damage, and nuclear stress. Treatment with NADES-formulated antioxidants enhances cellular antioxidant defenses and limits ROS accumulation, thereby preserving the structural integrity and functionality of mitochondria, chloroplasts, vacuoles, and the nucleus. This organelle-level stabilization provides a mechanistic basis for the high antioxidant activity measured in vitro and for the ability of NADES extracts to maintain native phytochemical profiles.

Figure 4.

Protective action of NADES-formulated antioxidants against ROS-induced organelle dysfunction. Schematic representation of the effects of oxidative stress and NADES-based antioxidant formulations (NADES + AO) on cellular organelles. Under abiotic stress conditions, including drought, salinity, heavy metal exposure, and pesticide pressure, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulate, and endogenous antioxidant systems (AOS) are reduced, which results in elevated ROS levels and structural damage to mitochondria, chloroplasts, vacuoles, and the nucleus (left panel). Treatment with NADES-formulated antioxidants increases antioxidant system activity (AOS↑), decreases intracellular ROS accumulation (ROS↓) and preserves the structural integrity and functional stability of major organelles (right panel). This organelle-level protection supports the enhanced antioxidant capacity observed for NADES-based extracts.

Finally, NADES often preserve the qualitative composition of antioxidant compounds and, in some cases, maintain profiles close to those of the original plant matrix. HPLC and LC–MS analyses of extracts from blueberry, orange peel, grape pomace, and Ugni molinae fruits show that NADES retain the characteristic distribution of anthocyanins, flavonols, and phenolic acids [11,25,47,48,50]. This compositional fidelity supports the functional antioxidant performance of NADES extracts and highlights their suitability for applications where the preservation of native phytochemical complexity is desirable.

2.4. Influence on Anti-Inflammatory Activity

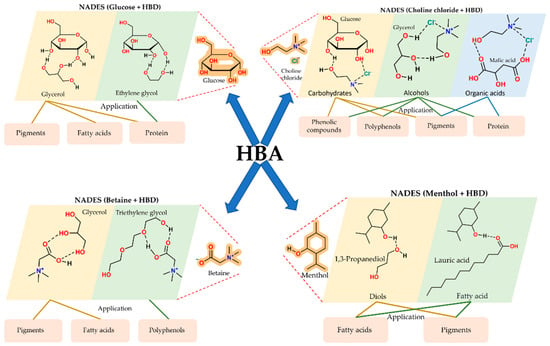

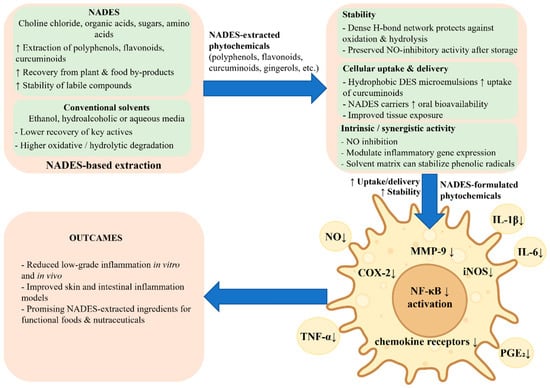

Evidence from cell and animal models indicates that phytochemicals extracted using NADES or DES often exhibit marked anti-inflammatory effects. These effects are usually evaluated in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated murine RAW 264.7 macrophages, human monocyte-derived macrophages, or skin and intestinal inflammation models (Figure 5). Typical readouts include nitric oxide (NO) production, prostaglandin synthesis, and the expression or secretion of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, together with the assessment of key inflammatory transcription factors and enzymes, including NF-κB, COX-2, and iNOS [52,53,54].

Figure 5.

NADES-based extracts and formulations enhance anti-inflammatory responses in macrophages. NADES improve the extraction, stability, and cellular delivery of polyphenols, flavonoids, and other bioactives. In LPS-stimulated macrophages and epithelial cells, NADES-formulated phytochemicals inhibit NF-κB activation and downregulate COX-2, iNOS, MMP-9, and chemokine receptors, leading to reduced production of NO, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and PGE2 and attenuation of low-grade inflammation.

NADES-based extracts frequently induce stronger inhibition of pro-inflammatory mediators than extracts prepared with conventional organic solvents at comparable concentrations of total phenolics. Polyphenol-rich extracts of Thunbergia laurifolia obtained with choline chloride- or proline-based NADES suppressed LPS-induced NO production in RAW 264.7 cells more efficiently than 95% ethanol extracts, and also reduced the expression of inflammatory genes, including iNOS and COX-2 [55]. A DES ultrasound-assisted flavonoid extract of Baihao Yinzhen white tea decreased TNF-α and IL-6 secretion in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages more strongly than a water extract, in line with its higher flavonoid yield [54]. Honey-based NADES formulations of Eurycoma longifolia preserved NO inhibitory activity after prolonged storage, and the non-sugar honey fraction showed intrinsic anti-inflammatory effects in the same model [56].

Mechanistic studies indicate that many NADES-derived extracts act upstream of cytokine release, at the level of inflammatory signaling pathways (Figure 5). Apple pomace polyphenols extracted with a choline chloride-based DES attenuated LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells and human monocyte-derived macrophages through the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression, coupled with the inhibition of NF-κB activation and the downregulation of COX-2 [52]. A curated review of DES systems for anti-inflammatory bioactives highlights similar findings for a range of phenolic and flavonoid compounds, including curcumin, rosmarinic acid, and rutin, where DES extraction increases recovery of active molecules that act on NF-κB-dependent pathways and eicosanoid biosynthesis [9]. Additional work with NADES-based ginger and resveratrol formulations shows inhibition of NF-κB and related inflammatory targets, such as MMP-9 and chemokine receptors, in cancer and endothelial cell models, which supports a broader role for NADES in modulating inflammation-related signaling [57].

Several studies suggest that the solvent matrix can enhance cellular uptake and the stability of bioactives, which contributes to the observed anti-inflammatory effects. A hydrophobic DES-based microemulsion containing curcuminoids and aromatic turmerone from Curcuma longa increased curcumin stability, delivered curcumin into murine macrophages, and achieved more than an 100-fold improvement in NO inhibitory potency compared with curcumin dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, while simultaneously lowering TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels [53]. Natural DES-based carriers also improve oral or dermal delivery. A glucose–choline chloride NADES increased the oral bioavailability of hydroxysafflor yellow A by more than three-fold and produced stronger metabolic and anti-obesity effects in high-fat-diet-fed rats [58]. Amino acid- or choline-based DES systems embedded in hydrogels or topical formulations support the efficient skin delivery of flavonoids such as kaempferol and reduce psoriasis-like skin inflammation, which indicates improved tissue exposure of the active compound [57,59].

In some cases, the DES or NADES matrix itself contributes to anti-inflammatory activity and synergy with the solute. Proline-based NADES used for Thunbergia extraction exhibited beneficial effects on inflammatory gene expression even in the absence of plant polyphenols [55]. Hydrophobic DES microemulsions showed NO inhibition before loading with Curcuma constituents, and honey-based NADES displayed measurable anti-inflammatory activity that added to the effect of Eurycoma metabolites [53,56]. These observations support the view that NADES can act as functional co-ingredients that stabilize labile phytochemicals, enhance their cellular delivery, and sometimes participate directly in the modulation of inflammatory pathways. As a result, NADES-extracted fractions from plant materials and food by-products, such as spent coffee grounds and apple pomace, emerge as promising functional ingredients for targeting low-grade inflammation in food and nutraceutical applications, provided that formulation optimization and safety assessment are carefully addressed [6,34,52].

2.5. Integration with Emerging Green Extraction Technologies

NADES show broad compatibility with modern green extraction technologies and support energy-efficient processing. Their use with ultrasound-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction, and pulsed electric fields improves mass transfer and promotes rapid cell disruption. Reviews on agro-food by-products confirm that these assisted processes with NADES result in higher yields of phenolic compounds and lower specific energy demand than conventional solvent extraction [60].

Ultrasound-assisted extraction with NADES increases the recovery of polyphenols, flavonoids, and ellagic acid from herbal and food matrices. Cavitation events open plant tissues and decrease boundary layers, so the diffusion of solutes into the viscous NADES phase becomes faster [60,61]. Microwave-assisted extraction in NADES further shortens the extraction time and often reaches similar or higher phenolic yields at lower solvent-to-solid ratios in agrifood residues [62,63]. Pressurized liquid extraction with aqueous NADES mixtures enables operation at elevated temperatures and pressures with green solvents and has resulted in the high recovery rate of grape pomace polyphenols [64,65]. These combinations support high extraction yields, shorter processing times, and reduced solvent consumption.

Enzyme-assisted extraction in NADES media enhances the release and biotransformation of bound phytochemicals. Cellulolytic and β-glucosidase enzymes retain high activity in selected biocompatible NADES and promote conversion of glycosides to more bioactive aglycones with improved extractability, for example, for Pueraria mirifica isoflavones [66,67]. Pulsed electric field treatment used together with deep eutectic solvents increases membrane permeabilization and improves recovery of flavonoids and polyphenols from fruit pomaces, kernels, and cocoa bean shells, while preserving antioxidant activity [68,69,70]. In these hybrid processes, NADES often show good thermal stability and protect thermolabile constituents due to their shorter exposure to high temperature and the presence of stabilizing hydrogen bond networks. Overall, coupling NADES with advanced extraction technologies positions these solvents as key components of future sustainable extraction strategies for food and nutraceutical ingredients.

2.6. Relevance to Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals

NADES-extracted bioactives exhibit properties highly relevant to functional foods and nutraceuticals. They often display improved solubility in aqueous or semi-aqueous systems, enhanced chemical stability during processing and storage, and preserved or increased antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities compared with ethanol or other organic solvents [3,10]. These features support their use as ingredients in beverages, fermented dairy products, bakery items, cereal-based products, plant-based meat and dairy analogs, and powdered nutraceutical formulations [71,72].

NADES are composed of dietary metabolites, including organic acids, sugars, amino acids, and choline derivatives. This composition is compatible with the concept of clean label, and aligns with current consumer demand for minimally processed products that use green technologies and food-grade auxiliaries [3,73]. When NADES remain in the final formulation, they can also act as co-stabilizers, humectants, or mild texturizing agents, which may reduce the need for additional additives in certain product categories [10,71].

Table 1 summarizes representative plant sources and food by-products that have been extracted with choline chloride- or betaine-based NADES, or related natural deep eutectic systems. The table links matrix type, typical NADES compositions, and dominant bioactive compounds, and reported antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities together with representative references. These examples illustrate the breadth of food-relevant sources that can be valorized through NADES’ extraction and demonstrate the potential for integrating NADES-based ingredients into functional foods and nutraceuticals [72,74,75].

Table 1.

Representative plant sources, NADES compositions, extracted compounds, and associated antioxidant or anti-inflammatory bioactivities relevant for functional foods.

3. Effect of NADES on Bioactivity Compared to Conventional Solvents

NADES often produce extracts with higher antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity than water or ethanol. This effect is attributed to the higher extraction yields of phenolics and flavonoids, as well as the preservation of labile compounds during processing and storage [50,94,95,96]. Comparative studies with berries, grape pomace, and herbal matrices report that NADES extracts frequently show stronger activity even when data are normalized to total phenolics or dry extract [25,94,97].

NADES enhance the stability of antioxidants, including anthocyanins, catechins, and curcuminoids. Dense hydrogen bonding, low volatility, and often reduced water activity limit oxidation and hydrolysis, as well as slow diffusion-controlled degradation. Anthocyanin-rich extracts in choline chloride-based NADES retain higher pigment content and color, and retain antiproliferative effects during storage compared to acidified ethanol extracts [25,50,98]. Similar behavior appears for NADES “ready-to-use” extracts from food by-products and herbal materials in which long-term antioxidant activity is preserved [95,99].

NADES exhibit a broad solubilization capacity for polar and moderately nonpolar phytochemicals. Strong hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, and dispersion forces support the dissolution of phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and carotenoids, which exhibit limited solubility in aqueous ethanol [2,7,100,101]. Extraction in NADES often yields more complex phytochemical profiles with a higher recovery rate of minor constituents that remain under-represented in ethanol extracts [94,96]. Such profiles can support synergistic interactions among compounds.

In antioxidant assays such as DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and ORAC, NADES extracts typically exhibit equal or higher activity compared to ethanol extracts. Studies using bilberry fruit, bilberry leaves, and green tea have shown higher total phenolics and higher DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP values for NADES systems compared to ethanol or water (Table 2). Blueberry peel, grape pomace, and several fruit by-products extracted with choline chloride-based or organic acid-based NADES display higher radical scavenging and reduced power compared to conventional extracts, and retain activity during storage [25,95,97,102]. Ready-to-use NADES extracts often retain high antioxidant capacity without further purification [95,96].

Anti-inflammatory assays also indicate performance advantages for NADES extracts. Flavonoid and polyphenol-rich NADES extracts from medicinal plants and food matrices show stronger inhibition of nitric oxide production and greater reduction in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 than ethanol extracts at comparable phenolic levels [97,99,103,104]. Some studies report stronger suppression of COX-2 and iNOS expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages for NADES extracts than for hydroalcoholic extracts, especially when ellagitannins, catechins, or curcuminoids are abundant [53,85,86,99,103]. A review of the DES-based extraction of anti-inflammatory compounds confirms that choline chloride- and natural metabolite-based systems often provide extracts with higher in vitro anti-inflammatory activity than ethanol [9,53,55,56,103].

The synergistic or modulatory effects of NADES components may contribute to these observations. NADES consist of metabolites such as organic acids, sugars, amino acids, and choline derivatives that can stabilize radical intermediates and affect redox cycling. Several studies show that the same plant extract dissolved in NADES produces higher antioxidant responses than in buffered aqueous media at equal phenolic contents [11,47,105]. Reviews on NADES’ bioavailability highlight the improved in vitro bioaccessibility and cellular uptake of polyphenols, noting that the solvent matrix can modulate transport and metabolism [96,106].

Overall, current evidence indicates that NADES extracts typically exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities comparable to or superior to those of ethanol extracts. The effect arises from the higher extraction yields, improved solubility of diverse phytochemicals, enhanced stability of labile molecules, and possible functional contributions of the solvent matrix. These features support the use of NADES in functional foods and nutraceuticals, which rely on preservation and optimization of biological activity.

Table 2.

Comparison of bioactivities of NADES extracts vs. ethanol (or other conventional) extracts.

Table 2.

Comparison of bioactivities of NADES extracts vs. ethanol (or other conventional) extracts.

| Plant Source/Bioactive Class | NADES Composition * | Compared Solvent | Antioxidant Activity | Anti-Inflammatory/Another Bioactivity | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thinned young kiwifruit (polyphenols) | Choline chloride:Glycerol (1:2) | Conventional ethanol extract and ultrasound-assisted ethanol extract | Significantly higher total phenolic content; NADES extract showed much higher FRAP, ABTS, DPPH, and·OH-scavenging activities than ethanol extracts. | Markedly stronger inhibition of NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells with maintained cell viability; overall higher anti-inflammatory activity. | Wu et al. 2023 [107] |

| Apple pomace (polyphenols) | Choline chloride:Glycerol (1:2), Choline chloride:Lactic acid (1:3), and Choline chloride:Citric acid (1:1) | Conventional hydroalcoholic solvent extraction (70% ethanol) | NADES produced higher total phenolic and flavonoid contents, lipid peroxidation inhibition, and overall antioxidant potential than the optimized conventional solvent. | Not reported. | Rashid et al. 2023 [49] |

| Citrus peel (Citrus sinensis, phenolics + ascorbic acid) | Choline chloride-based NADES with organic acids or polyols (e.g., Choline chloride:Malic acid (1:1)) | Water and aqueous ethanol | NADES markedly improved extraction of phenolic compounds and ascorbic acid and resulted in higher antioxidant capacity of the peel extracts compared with conventional solvents. | Not reported. | Gómez-Urios et al. 2023 [48] |

| Onion peel (quercetin-rich phenolics) | Choline chloride:Sucrose (4:1), Choline chloride:Urea (1:2), and Choline chloride:Sorbitol (3:1) | 60% ethanol and water | Selected NADES produced higher total phenolics and stronger DPPH/ABTS radical-scavenging capacity than 60% ethanol, and improved quercetin extraction efficiency. | Not reported. | Pal and Jadeja, 2018 [108] |

| Orange peel (polyphenolic antioxidants) | Choline chloride:Ethylene glycol (1:4) | Ethanol and methanol | Acidic NADES yielded more total phenolics and higher antioxidant capacity than conventional organic solvents, especially in DPPH and FRAP tests. | Not reported. | Ozturk et al. 2018 [32] |

| Paederia scandens aerial parts (polyphenols) | Choline chloride:Ethylene glycol (1:2) | Ethanol and water | Optimized NADES yielded higher phenolic yield and stronger DPPH/ABTS/FRAP activity than ethanol and water extracts. | Antimicrobial activities were compared. | Liu et al. 2022 [109] |

| Paris polyphylla rhizome (steroid saponins) | Choline chloride-based NADES with organic acid HBD | 80% ethanol | NADES system significantly increased extraction of total saponins and produced extracts with higher DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities than ethanol. | Antiproliferative properties. | Liu et al. 2022 [110] |

| Curcuma aromatica rhizome (curcuminoids) | Lactic acid:Fructose (5:1) and Lactic acid:Glucose (5:1) | 50 and 95% ethanol | NADES extracts showed higher curcuminoid content and stronger DPPH/ABTS/ORAC antioxidant capacity than ethanol extracts. | NADES systems produced the strongest inhibition of NO production and downregulation of inflammatory mediators in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells compared with ethanol extracts. | Sainakham et al. 2023 [111] |

* NADES composition is given as a representative example for each study; several works screened multiple hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and hydrogen bond donor (HBD) combinations and ratios, as detailed in the cited articles. ABTS = 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); DPPH = 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; FRAP = ferric reducing antioxidant power; and ORAC = oxygen radical absorbance capacity.

4. Safety, Regulatory Considerations, Scale-Up, and Industrial Applicability of NADES

The transfer of NADES from laboratory studies to functional food production needs evidence of safety, regulatory acceptability, and technical feasibility. NADES support sustainability, biodegradability, and efficient extraction. However, their use in commercial foods must meet toxicological, technological, and economic criteria that are acceptable to regulators and industry [3,6,112]. The most important safety and regulatory points are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Critical points for safety and regulation of NADES intended for foods.

Most food-oriented NADES are prepared from natural metabolites such as sugars, amino acids, organic acids, polyols, and choline derivatives. Many of these constituents are already used in foods. This supports their potential use in food systems. However, toxicity cannot be concluded from the individual components only. Eutectic formation changes hydrogen bonding, polarity, and viscosity. These changes can affect membrane interactions and uptake. Available in vitro studies often report low to moderate cytotoxicity for many food-grade combinations at relevant concentrations, while some formulations show higher effects at high doses [113,114,115]. In vivo evidence is still limited. Future studies should address digestion behavior, tissue distribution, excretion, chronic exposure, effects on the gut microbiota, and interactions with co-ingested nutrients. These data are needed for robust risk assessment.

Regulatory acceptance depends on the status of each constituent and on the technological function in the final product. In the United States, several common NADES constituents are listed in Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations as substances generally recognized as safe for use under good manufacturing practice [116]. Examples include choline chloride (21 CFR 182.8252), glycerin (21 CFR 182.1320), citric acid (21 CFR 184.1033), lactic acid (21 CFR 184.1061), malic acid (21 CFR 184.1069), tartaric acid (21 CFR 184.1099), and sorbitol (21 CFR 184.1835) (Table 4).

In the European Union, additives are regulated through the Union lists under Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008, and their specifications are laid down in Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 [117,118]. Many NADES constituents are authorized as food additives with E numbers. Examples include citric acid (E 330), lactic acid (E 270), malic acid (E 296), tartaric acid (E 334), sorbitol (E 420), and glycerol (E 422) (Table 4). In practice, manufacturers still need product-specific justification. They should define whether NADES act as a processing aid, an extraction solvent with residues, or a formulation ingredient. They should provide composition, specifications, stability, residual levels, and realistic exposure estimates.

Table 4.

Examples of NADES constituents with existing US GRAS affirmation and EU food additive authorization [116,119].

Table 4.

Examples of NADES constituents with existing US GRAS affirmation and EU food additive authorization [116,119].

| Constituent Used in NADES | United States, Example Legal Basis | European Union, Example Authorization, or Specification Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Choline chloride | 21 CFR 182.8252 | Used as an authorized additive-related substance in EU food additive context, subject to product specific assessment under EU food law. |

| Citric acid | 21 CFR 184.1033 | E 330 in EU database, with Union list basis in Reg 1333/2008. |

| Lactic acid | 21 CFR 184.1061 | E 270 in EU database, included in Union lists. |

| Malic acid | 21 CFR 184.1069 | E 296 in EU database, included in Union lists. |

| Tartaric acid | 21 CFR 184.1099 | E 334 in EU database, included in Union lists. |

| Glycerol | 21 CFR 182.1320 | E 422 specifications in Reg 231/2012. |

| Sorbitol | 21 CFR 184.1835 | E 420 specifications in Reg 231/2012. |

Scaling up raises technical challenges that relate mainly to viscosity, heat transfer, mass transfer, and solvent reuse. Many NADES are viscous at room temperature. This can increase pumping and mixing loads, and slow diffusion. Moderate heating and controlled water addition can reduce viscosity. Ultrasound-, microwave-, and pressure-assisted extraction can also improve mass transfer [4,18,62,120]. Solvent recovery is difficult because many NADES are non-volatile. Distillation is often not suitable. Alternative approaches include membrane separation, adsorption, and antisolvent precipitation, but these routes require optimization for industrial throughput and solvent recycling efficiency [4,121].

Economic viability depends on constituent costs and on process integration. Bulk components such as common organic acids, sugars, glycerol, and sorbitol are widely available. Some amino acids and speciality polyols are more expensive and may limit use in low margin products [3,120]. Costs can be reduced when NADES allow fewer purification steps and enable direct valorisation of low-cost by-products [3,73,120]. Pilot-scale work suggests that conventional extraction equipment can be used when flow behavior and cleaning protocols are adjusted [4,18,62,120]. Industrial implementation also requires sensory evaluation when NADES remain in the final formulation. In this case, NADES can act as carriers or stabilizers and can change flavor, texture, and clarity. Product-specific testing is therefore essential [3,4,73].

5. Challenges, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Research Directions

The use of natural deep eutectic solvents in functional foods that target antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects remains constrained by several unresolved issues in toxicology, process engineering, regulation, and economics. Current evidence confirms attractive extraction performance and promising bioactivity; however, data on long-term safety, large-scale operation, and product quality remain fragmentary. These gaps must be addressed before NADES can transition from laboratory studies to routine use in industrial food manufacturing.

A major challenge is the limited toxicological and metabolic characterization of complete NADES formulations. Many individual components, such as organic acids, sugars, amino acids, polyols, and choline derivatives, are food-grade. However, eutectic mixing modifies hydrogen bonding patterns, viscosity, polarity, and solvation behavior, which can change membrane interactions and bioavailability. Existing cytotoxicity and biodegradability studies on choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents report low-to-moderate toxicity in mammalian and microbial models at relevant concentrations but also identify more hazardous combinations at higher doses or with specific HBDs [122,123]. Systematic in vivo studies on digestion behavior, tissue distribution, excretion, and chronic exposure are still scarce. Future work should also clarify potential interactions of NADES with gut microbiota and intestinal barrier function, and should assess mixture-specific no-observed adverse effect levels for food applications.

Viscosity-related limitations remain a second key barrier. Many NADES exhibit very high viscosities at room temperature, which restricts diffusion, slows down extraction kinetics, and increases the demand for pumping and mixing energy. The addition of water, moderate heating, and the use of ultrasound or microwave assistance reduce viscosity and improve mass transfer; however, optimal conditions are strongly system dependent. Reviews of food analyses and food processing emphasize that high viscosity complicates scale-up and makes accurate process control more difficult, especially in continuous equipment [4,73]. There is a need for rational design rules that relate composition, water content, and temperature to viscosity, enabling the formulation of lower-viscosity NADES while maintaining the solubility and stability of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds.

Solvent recovery and recyclability represent a third technological challenge. The non-volatile character of NADES is advantageous for worker safety and for clean label applications but limits the use of distillation-based solvent removal. In many food applications, the solvent remains in the final product; however, this approach is not always acceptable due to sensory, regulatory, or formulation constraints. Recent work on DES and NADES in biomass processing and food analysis proposes membrane separations, adsorption, antisolvent precipitation, and switchable systems as routes to partial solvent recovery. However, these strategies are still at early developmental stages for food-grade systems and often lack detailed techno-economic assessment. Research should focus on low-energy, modular recovery schemes that allow multiple reuse cycles without significant loss of solvent performance.

Regulatory uncertainty also slows industrial adoption. Although most NADES components can be approved as food additives, nutrients, or processing aids, regulators typically evaluate the safety of complete formulations as a whole. Currently, there is no dedicated regulatory category for NADES in the food industry. Regulatory science discussions on deep eutectic solvents underscore the need for a case-by-case evaluation that encompasses migration, residues, exposure calculations, and mixture-specific toxicity, with potential analogies to flavoring solvents, enzyme preparations, and other processing aids [4]. Clear guidance regarding acceptable use levels, labeling requirements, and specifications for NADES that remain in the final product is still missing. Collaboration between academia, industry, and authorities will be essential to define risk assessment frameworks and to harmonize terminology across DES, NADES, and DES-like systems.

Knowledge gaps persist in understanding how NADES interact with complex food matrices and impact product quality. Most studies focus on extraction yields and in vitro antioxidant or anti-inflammatory tests. Fewer reports examine the effects on the sensory attributes, microstructure, phase behavior, or storage stability of the final foods. Available data suggest that carefully selected NADES can be incorporated into beverages, emulsions, bakery products, and edible coatings without negative taste or texture when used at appropriate levels. They may even enhance color and antioxidant stability in some fruit-based systems [73]. However, information on protein gelation, starch retrogradation, lipid oxidation, and biopolymer film properties in the presence of NADES is limited. Product-specific studies are needed to understand how NADES influence rheology, water activity, crystallization, and shelf life, and to determine matrix-dependent limits for acceptable sensory impact.

Economic and supply chain considerations provide an additional layer of complexity. Many NADES can be prepared from inexpensive and widely available components such as choline chloride, lactic or citric acid, glucose, fructose, and glycerol. Other systems rely on higher-cost amino acids or specialty polyols. Reviews of NADES in agri-food applications and functional ingredient production highlight that solvent cost, preparation energy, and the possibility of reuse must be considered in conjunction with process intensification benefits, such as shorter extraction times, higher yields, and fewer purification steps [3,124]. Comprehensive techno-economic analyses and life cycle assessments are still rare. These tools are necessary to identify application niches where NADES outperform aqueous ethanol, glycerol, supercritical fluids, or enzyme-assisted extraction in terms of both cost and environmental impact.

Finally, the mechanistic basis of NADES-enhanced bioactivity is still poorly understood. Many studies report higher antioxidant or anti-inflammatory effects of NADES extracts compared to conventional solvent extracts, even after normalization to total phenolics or target marker compounds. Proposed explanations include the better preservation of labile constituents, co-extraction of synergistic minor metabolites, and direct contributions of NADES components to redox activity or cell permeation. Recent work in pharmaceutical and food systems suggests that NADES can modify the solute microenvironment, stabilize radical intermediates, and influence membrane transport; however, a clear molecular-level picture is lacking. Greater use of spectroscopy, molecular dynamics simulations, and mechanistic cell-based assays could clarify how specific NADES compositions affect solute speciation, aggregation, and interaction with cellular targets.

Future research priorities can be summarized as follows:

- -

- Develop systematic toxicological and metabolic studies on food-grade NADES, including digestion, microbiota interactions, and chronic exposure.

- -

- Establish composition–structure–property relationships for viscosity, polarity, and water activity, which guide the formulation of low-viscosity yet highly solvating NADES.

- -

- Design scalable, low-energy solvent recovery and recycling strategies that are compatible with food regulations and maintain solvent integrity.

- -

- Create regulatory frameworks and guidance documents that define NADES categories, data requirements, and labeling rules for food use.

- -

- Investigate NADES’ effects on sensory quality, microstructure, and shelf life in real functional food products, not only in model systems.

- -

- Perform comparative techno-economic and life cycle assessments for NADES-based processes versus established green extraction technologies.

- -

- Elucidate the mechanistic contributions of NADES to enhanced antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity and use this knowledge to design function-oriented solvent systems.

By addressing these challenges in a coordinated manner, NADES can transition from a promising laboratory concept to a robust platform technology for the development of sustainable, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory functional foods.

6. Conclusions

NADES are a promising platform for the extraction, stabilization, and delivery of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory bioactives in functional foods. They are composed of food-related metabolites and exhibit tunable polarity and a strong hydrogen-bonding capacity. These properties enable the efficient recovery of polyphenols and other phytochemicals from plant materials and food by-products. Ultrasound-, microwave-, and pressure-assisted extraction methods can further enhance yields while reducing energy demand and solvent consumption. Across diverse matrices, NADES-based extracts often match or exceed the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory performance of ethanol or water extracts when normalized to total phenolic content. This effect primarily reflects improved recovery of active compounds and enhanced protection of labile molecules, although contributions from the solvent matrix itself may occur in certain systems. Mechanistic studies indicate the modulation of inflammatory signaling pathways, including NF-κB, accompanied by changes in mediators such as COX-2, iNOS, nitric oxide, and pro-inflammatory cytokines. NADES can also improve cellular uptake and in vivo exposure of bioactives, supporting their use as carriers for functional ingredients. Beyond bioactivity enhancement, NADES also enable the valorization of plant residues and agro-industrial side streams into high-value ingredients. However, scale-up remains challenging due to their high viscosity, low volatility, and limited solvent recovery options. Effective process design must therefore address rheology, mass and heat transfer, solvent recycling, and equipment compatibility. Although techno-economic and life cycle data remain limited, the available evidence indicates a strong potential for high-value applications, particularly when NADES remain in the final formulation and replace separate carrier systems. Safety and regulatory aspects are critical considerations. While many individual constituents are approved for food use, complete mixtures require further evaluation. Key knowledge gaps include digestion behavior, microbiota interactions, and thresholds for chronic exposure. Future work should focus on developing lower-viscosity, food-grade NADES, improving sensory properties, enabling low-energy solvent reuse, and expanding in vivo and comparative assessments.

Author Contributions

V.H. and O.B.: Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, and supervision. V.H.: visualization. E.K.: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic, the Institutional project number MZE-RO0425 and by METROFOOD-CZ project MEYS, Grant No: LM2023064.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azinobis (3-ethylBenzoThiazoline-6-Sulfonic acid) |

| AOS | Antioxidant Systems |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| DES | Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| DPPH | 2,2-DiPhenyl-1-PicrylHydrazyl |

| FRAP | Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| HBA | Hydrogen Bond Acceptor |

| HBD | Hydrogen Bond Donor |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IL-1β | InterLeukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | InterLeukin-6 |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| LC–MS | Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| LPS | LipoPolySaccharide |

| NADES | Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| ORAC | Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

References

- Choi, Y.H.; van Spronsen, J.; Dai, Y.; Verberne, M.C.; Hollmann, F.; Arends, I.W.; Witkamp, G.; Verpoorte, R. Are Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents the Missing Link in Understanding Cellular Metabolism and Physiology? Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1701–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; van Spronsen, J.; Witkamp, G.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as New Potential Media for Green Technology. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 766, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Laredo, R.F.; Sayago-Monreal, V.I.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Landeros-Macías, L.F.; Rosales-Castro, M. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) as an Emerging Technology for the Valorization of Natural Products and Agro-Food Residues: A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 6660–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavacciuolo, C.; Pagliari, S.; Frigerio, J.; Giustra, C.M.; Labra, M.; Campone, L. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADESs) Combined with Sustainable Extraction Techniques: A Review of the Green Chemistry Approach in Food Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owczarek, K.; Szczepańska, N.; Plotka-Wasylka, J.; Rutkowska, M.; Shyshchak, O.; Bratychak, M.; Namieśnik, J. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in Extraction Process. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2016, 10, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Roldán, A.; Piriou, L.; Jauregi, P. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as a Green Extraction of Polyphenols from Spent Coffee Ground with Enhanced Bioactivities. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1072592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, F.d.S.; Koblitz, M.G.B. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Agro-Industrial By-Products Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Green and Advanced Techniques. Separations 2025, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.M.; Yiin, C.L.; Mun Lock, S.S.; Fui Chin, B.L.; Othman, I.; binti Ahmad Zauzi, N.S.; Chan, Y.H. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) for Sustainable Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 425, 127202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, B.; Sangüesa, E.; Zuriaga, E.; Culleré, L.; Lomba, L. Deep Eutectic Solvent Systems as Media for the Selective Extraction of Anti-Inflammatory Bioactive Agents. Molecules 2025, 30, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacci, S.; Di Gioia, M.L.; Costanzo, P.; Maiuolo, L.; Tallarico, S.; Nardi, M. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent as Extraction Media for the Main Phenolic Compounds from Olive Oil Processing Wastes. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, L.; Xavier, L.; Zecchi, B. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds with Antioxidant Activity from Olive Pomace Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: Modelling and Optimization by Response Surface Methodology. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ortega, L.A.; Kumar-Patra, J.; Kerry, R.G.; Das, G.; Mota-Morales, J.D.; Heredia, J.B. Synergistic Antioxidant Activity in Deep Eutectic Solvents: Extracting and Enhancing Natural Products. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 2776–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rente, D.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R. The Role of Hydrogen Bond Donor on the Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Natural Matrices Using Deep Eutectic Systems. Molecules 2021, 26, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikmawanti, N.P.E.; Ramadon, D.; Jantan, I.; Mun’im, A. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES): Phytochemical Extraction Performance Enhancer for Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Product Development. Plants 2021, 10, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Friesen, J.B.; McAlpine, J.B.; Lankin, D.C.; Chen, S.N.; Pauli, G.F. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: Properties, Applications, and Perspectives. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristivojević, P.; Krstić Ristivojević, M.; Stanković, D.; Cvijetić, I. Advances in Extracting Bioactive Compounds from Food and Agricultural Waste and By-Products Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Circular Economy Perspective. Molecules 2024, 29, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregi, P.; Esnal-Yeregi, L.; Labidi, J. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) for the Extraction of Bioactives: Emerging Opportunities in Biorefinery Applications. PeerJ Anal. Chem. 2024, 6, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamede Airouyuwa, J.; Mostafa, H.; Riaz, A.; Maqsood, S. Utilization of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction as Green Extraction Technique for the Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Seeds: An Investigation into Optimization of Process Parameters. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 91, 106233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, C.; Gallo, V.; Della Posta, S.; Dugo, L.; Mazzeo, L.; Cocchi, M.; Piemonte, V.; De Gara, L. Choline Chloride–Lactic Acid-Based NADES As an Extraction Medium in a Response Surface Methodology-Optimized Method for the Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Hazelnut Skin. Molecules 2021, 26, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, A.; Šeregelj, V.; Ribeiro, B.D.; Pezo, L.; Cvetanović, A.; Mišan, A.; Marrucho, I. Recovery of β-Carotene from Pumpkin using Switchable Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Mouro, C.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J.; Gouveia, I. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction of Bioactive Pigments from Spirulina platensis and Electrospinning Ability Assessment. Polymers 2023, 15, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.; Mouro, C.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J.; Gouveia, I. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Pigments from Spirulina platensis in Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2023, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Abrosca, B.; DellaGreca, M.; Fiorentino, A.; Monaco, P.; Zarrelli, A. Low Molecular Weight Phenols from the Bioactive Aqueous Fraction of Cestrum parqui. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4101–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Vázquez, J.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Boczkaj, G.; Castro-Muñoz, R. Latest Insights on Novel Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) for Sustainable Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Natural Sources. Molecules 2021, 26, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, G.; Gunjević, V.; Radošević, K.; Redovniković, I.R.; Cravotto, G. Deep Eutectic Solvents and Nonconventional Technologies for Blueberry-Peel Extraction: Kinetics, Anthocyanin Stability, and Antiproliferative Activity. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchera, F.; Ginepro, M.; Giacalone, G. Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) of bioactive compounds from blueberry by-products using a sugar-based NADES: A novelty in green chemistry. LWT 2024, 192, 115642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, D.; Belwal, T.; Xie, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, L.; Zou, L.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Z. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Enhanced Pulse-ultrasonication Assisted Extraction as a Multi-stability Protective and Efficient Green Strategy to Extract Anthocyanin from Blueberry Pomace. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 144, 111220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Martín, M.; Cubero-Cardoso, J.; González-Domínguez, R.; Cortés-Triviño, E.; Sayago, A.; Urbano, J.; Fernández-Recamales, Á. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Blueberry Leaves Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) for the Valorization of Agrifood Wastes. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 175, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajha, H.N.; Mhanna, T.; El Kantar, S.; El Khoury, A.; Louka, N.; Maroun, R.G. Innovative Process of Polyphenol Recovery from Pomegranate Peels by Combining Green Deep Eutectic Solvents and a New Infrared Technology. LWT 2019, 111, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.L.D.; Domínguez-Rodríguez, G.; Montero, L.; Viganó, J.; Cifuentes, A.; Rostagno, M.A.; Ibáñez, E. Advanced Extraction Techniques Combined with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Extracting Phenolic Compounds from Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Peels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrugaibah, M.; Yagiz, Y.; Gu, L. Use Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as Efficient Green Reagents to Extract Procyanidins and Anthocyanins from Cranberry Pomace and Predictive Modeling by RSM and Artificial Neural Networking. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 255, 117720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.; Parkinson, C.M.; González-Miquel, M. Extraction of Polyphenolic Antioxidants from Orange Peel Waste Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 206, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, M.; Andlar, M.; Tišma, M.; Rezić, T.; Šibalić, D.; Cvjetko Bubalo, M.; Radojčić Redovniković, I. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent as a Unique Solvent for Valorisation of Orange Peel Waste by the Integrated Biorefinery Approach. Waste Manag. 2020, 120, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Fakayode, O.A.; Li, H. Green Extraction of Polyphenols via Deep Eutectic Solvents and Assisted Technologies from Agri-Food By-Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, M.; Gunjević, V.; Cravotto, G.; Radojčić Redovniković, I. Enabling Technologies for the Extraction of Grape-Pomace Anthocyanins Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in Up-To-Half-Litre Batches Extraction of Grape-Pomace Anthocyanins Using NADES. Food Chem. 2019, 300, 125185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosiljkov, T.; Dujmić, F.; Bubalo, M.C.; Hribar, J.; Vidrih, R.; Brnčić, M.; Zlatić, E.; Redovniković, I.R.; Jokić, S. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents and Ultrasound-assisted Extraction: Green Approaches for Extraction of Wine Lees Anthocyanins. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Pontes, P.V.; Ayumi Shiwaku, I.; Maximo, G.J.; Caldas Batista, E.A. Choline Chloride-based Deep Eutectic Solvents as Potential Solvent for Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Olive Leaves: Extraction Optimization and Solvent Characterization. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Granados, M.; Saurina, J.; Sentellas, S. Green Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from Olive Tree Leaves Based on Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badea, G.I.; Gatea, F.; Litescu-Filipescu, S.C.; Alecu, A.; Chira, A.; Damian, C.M.; Radu, G.L. Optimization of Green Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Carotenoids and Tocopherol from Tomato Waste Using NADESs. Molecules 2025, 30, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanali, C.; Della Posta, S.; Dugo, L.; Gentili, A.; Mondello, L.; De Gara, L. Choline-chloride and Betaine-based Deep Eutectic Solvents for Green Extraction of Nutraceutical Compounds from Spent Coffee Ground. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 189, 113421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Gómez-Urios, C.; Razavi, S.H.; Khodaiyan, F.; Blesa, J.; Esteve, M.J. Optimization of Solid-state Fermentation Conditions to Improve Phenolic Content in Corn Bran, Followed by Extraction of Bioactive Compounds Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 93, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urios, C.; Viñas-Ospino, A.; Puchades-Colera, P.; López-Malo, D.; Frígola, A.; Esteve, M.J.; Blesa, J. Sustainable Development and Storage Stability of Orange By-Products Extract Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Foods 2022, 11, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.T.; Rodrigues, R.F.; Machado, N.M.; Maurer, L.H.; Ferreira, L.F.; Somacal, S.; da Veiga, M.L.; Rocha, M.I.; Vizzotto, M.; Rodrigues, E.; et al. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES)-based Blueberry Extracts Protect Against Ethanol-induced Gastric Ulcer in Rats. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putu Ermi Hikmawanti, N.; Chany Saputri, F.; Yanuar, A.; Jantan, I.; Asmana Ningrum, R.; Betha Juanssilfero, A.; Mun’im, A. Choline Chloride-Urea-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent for Highly Efficient Extraction of Polyphenolic Antioxidants from Pluchea indica L. Leaves. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 17, 105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Z.; Tao, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W. Effects of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent on the Extraction Efficiency and Antioxidant Activities of Toona sinensis Seed Polyphenols: Composition and Mechanism. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourani, S.; Vukosavljević, J.; Teslić, N.; Ždero Pavlović, R.; Popović, B.M.; Pavlić, B. Optimization of Green Extraction of Antioxidant Compounds from Blackthorn Pomace (Prunus spinosa L.) Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES). Processes 2025, 13, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antileo-Laurie, J.; Olate-Olave, V.; Fehrmann-Riquelme, V.; Anabalón-Alvarez, C.; Cid-Carrillo, L.; Campanini-Salinas, J.; Fernández-Galleguillos, C.; Quesada-Romero, L. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NaDES) Extraction, HPLC-DAD Analysis, and Antioxidant Activity of Chilean Ugni molinae Turcz. Fruits. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Urios, C.; Viñas-Ospino, A.; Puchades-Colera, P.; Blesa, J.; López-Malo, D.; Frígola, A.; Esteve, M.J. Choline Chloride-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction and Stability of Phenolic Compounds, Ascorbic Acid, and Antioxidant Capacity from Citrus sinensis Peel. LWT 2023, 177, 114595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Mohd Wani, S.; Manzoor, S.; Masoodi, F.A.; Masarat Dar, M. Green Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Apple Pomace by Ultrasound Assisted Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction: Optimisation, Comparison and Bioactivity. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivisiol da Silva, D.; Pauletto, R.; da Silva Cavalheiro, S.; Caetano Bochi, V.; Rodrigues, E.; Weber, J.; de Bona da Silva, C.; Dal Pont Morisso, F.; Teixeira Barcia, M.; Emanuelli, T. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as a Biocompatible Tool for the Extraction of Blueberry Anthocyanins. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 89, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urios, C.; Siroli, L.; Grassi, S.; Patrignani, F.; Blesa, J.; Lanciotti, R.; Frígola, A.; Iametti, S.; Esteve, M.J.; Di Nunzio, M. Sustainable Valorization of Citrus by-Products: Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Bioactive Extraction and Biological Applications of Citrus sinensis Peel. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 1965–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, J.; Yu, L.; Fitter, S.; Kumorkiewicz-Jamro, A.; Vandyke, K.; Bulone, V.; Zannettino, A.C. Apple Pomace Polyphenols Extracted by Deep Eutectic Solvent Ameliorate Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation in RAW264.7 Murine Macrophages and Human Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supaweera, N.; Chulrik, W.; Jansakun, C.; Bhoopong, P.; Yusakul, G.; Chunglok, W. Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Microemulsion Enhances Anti-Inflammatory Efficacy of Curcuminoids and Aromatic-Turmerone Extracted from Curcuma longa L. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 25912–25922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chu, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, H.; Hong, S.; Kong, D.; Du, L. Total Flavonoid Extraction from Baihao Yinzhen Utilizing Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent: Optimization of Conditions, Anti-Inflammatory, and Molecular Docking Analysis. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimawong, C.; Torkaew, P.; Putalun, W. Polyphenol-Enriched Extraction from Thunbergia laurifolia using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Enhanced Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22086–22096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthisak, C.; Jomrit, J.; Chunglok, W.; Putalun, W.; Kanchanapoom, T.; Juengwatanatrakul, T.; Yusakul, G. Effect of Honey, as a Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent, on the Phytochemical Stability and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Eurycoma longifolia Jack. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 5252–5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.B.; Concha, J.; Culleré, L.; Lomba, L.; Sangüesa, E.; Ribate, M.P. Has the Toxicity of Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Systems Been Assessed? Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhou, H.; Yue, S.; Feng, L.; Guo, D.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, L.; Tang, Y. Oral Bioavailability-Enhancing and Anti-obesity Effects of Hydroxysafflor Yellow A in Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 19225–19234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, X.; Meng, L. Development of a Deep Eutectic Solvent-Assisted Kaempferol Hydrogel: A Promising Therapeutic Approach for Psoriasis-like Skin Inflammation. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 6319–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Adeyanju, A.; Nwonuma, C.; Inyinbor, A.; Alejolowo, O.; Al-Hamayda, A.; Akinsemolu, A.; Onyeaka, H.; Olaniran, A. Physical field-assisted deep eutectic solvent processing: A Green and Water-saving Extraction and Separation Technology. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 8248–8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yue, S.-J.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, D.-Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.-J.; Tang, Y.-P. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent-Ultrasound Assisted Extraction: A Green Approach for Ellagic Acid Extraction from Geum japonzicum. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1079767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Quirós, P.; Granados, M.; Sentellas, S.; Saurina, J. Microwave-Assisted Extraction with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Polyphenol Recovery from Agrifood Waste: Mature for Scaling-up? Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaisan, S.; Makkliang, F.; Putalun, W.; Sakamoto, S.; Yusakul, G. Development of a Colorless Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. Extract Using a Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES) and Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) Optimized by Response Surface Methodology. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 8741–8750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, T.O.; Portugal, I.; Kodel, H.D.; Fathi, A.; Fathi, F.; Oliveira, M.B.; Dariva, C.; Souto, E.B. Pressurized Liquid Extraction as an Innovative High-Yield Greener Technique for Phenolic Compounds Recovery from Grape Pomace. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 40, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loarce, L.; Oliver-Simancas, R.; Marchante, L.; Díaz-Maroto, M.C.; Alañón, M.E. Implementation of Subcritical Water Extraction with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Sustainable Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Winemaking by-Products. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkliang, F.; Siriwarin, B.; Yusakul, G.; Phaisan, S.; Sakdamas, A.; Chuphol, N.; Putalun, W.; Sakamoto, S. Biocompatible Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Extraction and Cellulolytic Enzyme-Mediated Transformation of Pueraria mirifica Isoflavones: A Sustainable Approach for Increasing Health-Bioactive Constituents. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.-B.; Zhang, L.-W. Highly Efficient Enzymatic Preparation of Daidzein in Deep Eutectic Solvents. Molecules 2017, 22, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, W.; Niu, D.; Wang, R.; Xu, F.; Chen, B.; Lin, J.; Tang, Z.; Zeng, X. Efficient and Green Strategy Based on Pulsed Electric Field Coupled with Deep Eutectic Solvents for Recovering Flavonoids and Preparing Flavonoid Aglycones from Noni-processing Wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrygiannis, I.; Athanasiadis, V.; Bozinou, E.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Makris, D.P.; Lalas, S.I. Combined Effects of Deep Eutectic Solvents and Pulsed Electric Field Improve Polyphenol-Rich Extracts from Apricot Kernel Biomass. Biomass 2023, 3, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]