Abstract

Semiconductor manufacturing is a resource and energy-intensive industry with a substantial environmental footprint. To address the footprint, we present a methodology for quantifying the environmental impact of semiconductor unit processes using the Environmental Footprint 3.1 Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) framework, focusing on identifying improvement opportunities in process steps with less sensitivity to defects. We apply this methodology to backside wet cleaning by proposing an alternative single-wafer process that adopts ozonated chemistries. The assessment used primary data from imec’s 300 mm pilot line. Results show that the proposed process reduces the total environmental footprint by 55% compared to the baseline Spin Cleaning with Repetitive use of Ozonated water and Diluted HF process. Key reductions include 67% less electricity for cleaning, 59% less HF use, and a 31% reduction in ultrapure water consumption. When scaled to a facility producing N28 Logic wafers at 50,000 wafer starts per month, with 46 backside clean steps per processed wafer, the process achieves annual savings of approximately 4 million kWh of electricity and 28 million liters (28,000 m3) of tap water per year. A sensitivity analysis revealed that replacing fossil-based electricity with hydroelectric power further reduces total environmental impacts by up to 63%, emphasizing the benefit of combining process innovation with renewable energy sourcing.

1. Introduction

The escalating environmental crisis, most visibly by climate change, presents one of humanity’s most pressing challenges. Anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, primarily from the combustion of fossil fuels, have driven global temperatures to record highs; 2024 was officially the warmest year on record, with average global temperatures surpassing 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels [1]. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), limiting warming to this threshold is crucial to avoid irreversible ecological tipping points [2]. Yet climate change is only one facet of a broader environmental crisis, including overconsumption of water resources, leading to disruptions in the water cycle, increased acidification, and long-term ecological degradation, many of which will take centuries or longer to reverse. In this context, every effort to reduce human impact on the environment, regardless of scale, becomes crucial.

At the core of modern digital infrastructure, the semiconductor industry is a rapidly growing contributor to this environmental footprint. Global semiconductor sales increased by 18.8% in Q1 2025 compared to the same period in 2024 [3], driven by surging demand for AI accelerators, edge computing devices, and advanced technologies across sectors such as automotive, cloud services, and healthcare [4]. With national and regional investments accelerating the localization of semiconductor supply chains, the construction of new fabrication facilities (fabs) is at an all-time high. However, this exponential growth comes with a steep environmental cost.

Semiconductor fabs are resource-intensive by design. They operate 24/7, consuming vast amounts of electricity, ultrapure water (UPW), and specialty chemicals, many of which have high global warming potential (GWP) or persist in the environment [5,6,7]. For example, fabs require tens of millions of liters of UPW per day for wafer cleaning and cooling and produce significant emissions using fluorinated greenhouse gases and process chemicals [8]. According to TechInsights, semiconductor-related GHG emissions are projected to rise from 168 million metric tons CO2 equivalent in 2020 to 277 million metric tons CO2 equivalent by 2030 [9]. As semiconductor technology advances to support advanced computing performance, so does the environmental burden associated with the manufacturing process [10].

This makes the integration of sustainable process design in both new and existing fabs an ethical obligation and a strategic imperative. While new fabs offer an opportunity to design and implement lower-impact processes from the ground up, retrofitting existing high-volume manufacturing (HVM) facilities remains a substantial challenge. Process qualification requirements are stringent, and fabs are understandably reluctant to modify mature process flows that could jeopardize yield or reliability. As a result, the industry has historically resisted adopting new technologies or methodologies unless they offer clear performance or cost advantages.

While the sustainability challenge in semiconductor manufacturing is recognized, the published literature primarily focuses on macro-level strategies like renewable energy [11], facility-level water management [12], or theoretical modeling of environmental burdens [13]. These studies are essential for setting industry targets but often lack the granularity required for direct process-level implementation. There is a significant gap in data-driven case studies that demonstrate the successful retrofitting of sustainable, alternative chemistries into existing high-volume manufacturing processes.

To overcome this barrier, a pragmatic and phased approach is necessary. Rather than immediately changing core process steps critical to device yield and defectivity, sustainability efforts can begin with non-critical process steps, such as wafer backside cleaning. These steps are typically considered peripheral to device performance, but they are still resource-intensive. Demonstrating successful improvements in such areas can serve as proof-of-concept, paving the way for broader adoption of sustainable practices across more yield-critical process modules in the future.

This work directly addresses a knowledge gap by providing an industrially relevant blueprint for introducing a resource-efficient wet cleaning process validated on an active 300 mm pilot line. By focusing on wafer backside cleaning and employing a life cycle assessment based on primary data, this paper shows the specific, implementable evidence that is currently missing in the academic discourse on semiconductor sustainability.

This paper proposes a single-wafer wet cleaning process that replaces conventional repetitive hydrofluoric acid (HF)-based steps known as ‘Spin Cleaning with Repetitive use of Ozonated water and Diluted HF’ (SCROD) [14]. This cleaning procedure relies on the sequential oxidation and etching of the silicon wafer surface. In the first step, a thin silicon oxide layer is formed by ozonated water. The second step includes dispensing diluted HF, leading to the complete etching of SiO2. Our alternative process proposal reduces hazardous chemicals, lowers ultrapure water and energy consumption, and simplifies the process flow by minimizing the number of steps. Life cycle assessment (LCA) is employed to quantify the environmental impact using primary data from imec’s 300 mm pilot line, which operates on state-of-the-art processing tools representative of HVM. Using primary, fab-level data adds high realism and industrial relevance to the analysis.

An initial full technology flow impact assessment is carried out using imec.netzero, a dedicated and industry-recognized LCA platform for semiconductor manufacturing [15]. Hotspot analysis is used to identify environmentally intensive process steps, followed by a scenario-based comparison between traditional and alternative process flows. The study also includes a sensitivity analysis of the carbon intensity of electricity sources. The methodology, experimental set-up, and environmental modeling are described in detail, followed by the presentation of results and a discussion of their implications for both new fab design and the retrofitting of existing lines. This work offers a practical blueprint for initiating sustainability transitions in an industry typically constrained by stringent process change limitations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Goal and Scope Definition

This study aims to achieve two primary goals within the context of high-volume semiconductor manufacturing. The first goal is to quantify the overall environmental impact of a complete process flow for representative logic technology nodes (N90–A14). The initial assessment will identify significant environmental hotspots within the process and establish a baseline for subsequent comparisons.

The scope of the overall environmental impact analysis is confined to process steps associated with the fabrication of logic devices in high-volume semiconductor manufacturing facilities. This focus is motivated by market trends reported in SEMI industry forecasts [16], indicating a continued exponential rise in demand for compute performance. The environmental hotspot assessment in this work focuses on three indicators: total water consumption, total chemical consumption, and total global warming potential over 100 years (GWP100). These indicators were selected based on data availability and significance within the semiconductor sector’s sustainability strategies, including net-zero emissions commitments and water reduction targets [12,17].

The second goal is to conduct a full Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) comparing two alternative wet cleaning process solutions for processing 28 nm logic node wafers. Among mature technology nodes, the 28 nm node has emerged as a particularly relevant case due to its optimal balance of cost, performance, and availability. Despite the attention often given to leading-edge nodes, 28 nm technology remains a cornerstone of the semiconductor industry [18], supported by its widespread adoption and versatility across diverse application domains. Consequently, this study adopts the 28 nm logic technology node as a representative case study. The comparative assessment aims to quantify the effect on the annual environmental impact of implementing alternative wet cleaning process solutions.

The scope of the LCA comparing two scenarios of wafer wet cleaning comprises all process steps, starting from the onsite deionized water (DIW) and nitrogen gas production to the wet clean processing, and the drain water neutralization. It includes all 16 LCIA indicators defined under the Environmental Footprint (EF) 3.1 methodology, developed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission. Individual indicator results were subjected to normalization and weighting to facilitate a comparative evaluation, culminating in a single aggregated score for each scenario.

2.2. Environmental Assessment Methodology

2.2.1. Complete Process Flow Assessment

The initial environmental assessments of full flow logic technology nodes used a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) tool developed by imec called imec.netzero version 5.1.2. It uses a bottom-up approach, starting with process flows, recipes, and tool data to build the inventory of a virtual high-volume semiconductor manufacturing fab. It calculates the cradle-to-gate environmental impact of processing various generic semiconductor technology nodes. The full methodology behind this tool can be found on imec.netzero public website [15]. The data was calculated using imec.netzero version 5.1.2 for logic technologies N90 to A14.

The functional unit selected for the initial assessment is the processing of a single full wafer, based on default parameter settings defined in the imec.netzero modeling framework. This choice reflects the objective of the initial analysis, which is to identify environmental hotspots within the fabrication process of logic technology nodes. By expressing impacts on a per-wafer basis, the assessment emphasizes the operational function of the manufacturing facility (fab) rather than the performance characteristics of the final semiconductor product.

To identify environmental hotspots, the manufacturing process was divided into process classes. The classes used in this study are chemical mechanical polishing (CMP), deposition, dry etch, implantation, lithography, logistics, metallization, metrology, and wet processes. A class is a group of process areas, e.g., the deposition class consists of three process areas: chemical vapor deposition (CVD), epitaxy, and diffusion. See imec.netzero methodology documentation for more information on subgroup definitions [15].

The indicators for the initial environmental assessment are GWP, water consumption, and chemical consumption. The total GWP impact calculated using the imec.netzero tool represents the cradle-to-gate impact on climate change resulting from fab operation. The GWP impact is expressed in kilograms of CO2 equivalent per wafer.

For the initial assessment, ultra-pure water (UPW) consumption is used as an indicator of the environmental impact of water consumption, where high UPW consumption in the fab negatively impacts water availability in the region. UPW is produced onsite in an HVM fab and is consumed by processing equipment. UPW production is not a single process but rather a series of cleaning processes that include various filters, UV treatments, and temperature control.

The third indicator quantifies the total chemical consumption, representing the total amount of each liquid-state chemical used in the processing. Wet chemicals are often associated with human health-related impact in addition to environmental impact during their life cycle [19,20]. Therefore, this study assumes that low chemical consumption, acknowledged here as a purely quantitative indicator that does not capture chemical-specific characteristics such as toxicity, represents a more sustainable practice in semiconductor processing than higher chemical consumption.

2.2.2. Scenario Analysis of Wet Solutions

After the initial environmental assessment, the wet process class was selected for environmental optimization, and experimental work was conducted at imec’s research facility in Leuven, Belgium, to develop an alternative low-impact processing solution. A detailed LCA for the baseline and low-impact scenarios was developed. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) data were collected onsite at imec via a mass and energy balance surrounding the experimental system, described in Section 3.2.2. All other flows related to the operation of the clean room or facilities are not considered in the scope of analysis, as they are considered to be equivalent for both scenarios. This functional unit allows the quantification of the potential environmental impact reduction in the alternative wet cleaning solution compared to the baseline.

2.3. Experimental Set-Up

To compare the standard SCROD [14] process (baseline) and an alternative low-impact single wafer backside clean process, state-of-the-art 300 mm tools were used in the cleanroom environment (pilot line at imec). All experiments were performed using 300 mm standard, both-sides-polished silicon wafers with an average thickness of 775 μm.

The tool used for wet processing experiments was a 4-chamber tool from the DVPRIME series (Lam Research, Villach, Austria), where wafer cleaning is performed in parallel in all chambers. It is equivalent to the tools used in HVM. An advanced monitoring system (Levitronix ultrasonic flow meters, Zurich, Switzerland) allows for precise measurement of consumed chemical volumes. Energy consumption used during processing is calculated based on the actual performance of the components (heaters, pumps, generators) and their nominal power. In this study, we do not consider chemicals, UPW, and energy used by the tool apart from processing, which is also known as an idle state of the tool.

Wafer roughness was measured using an automated AFM tool from the NX3DM series (Park Systems, Suwon, Korea). The automated TXRF tool (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure the metal traces on the wafer surface. All wafers were measured before and after the wet clean treatment.

For the metal removal evaluation, aluminum (Al), calcium (Ca), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), potassium (K), molybdenum (Mo), sodium (Na), nickel (Ni), titanium (Ti), tungsten (W), and zinc (Zn) solutions were spin-coated onto wafers. The ICP MS standards for each metal solution were deployed for this purpose.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Environmental Assessment of Full Flow Technologies

The results in Section 3.1 for the various impact categories are provided per class, which is a subgroup defined for the foreground processes. These processes are indicative of HVM semiconductor manufacturing, but are based on a generalized virtual fab model, rather than any specific company of production fabs.

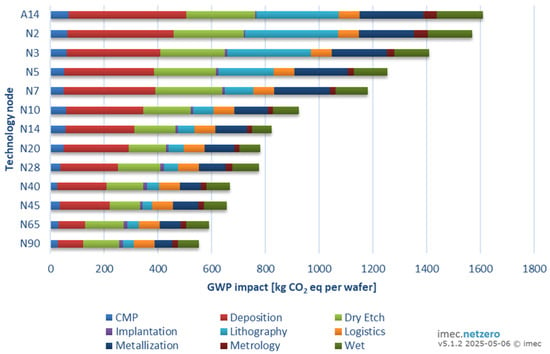

3.1.1. Total GWP Impact

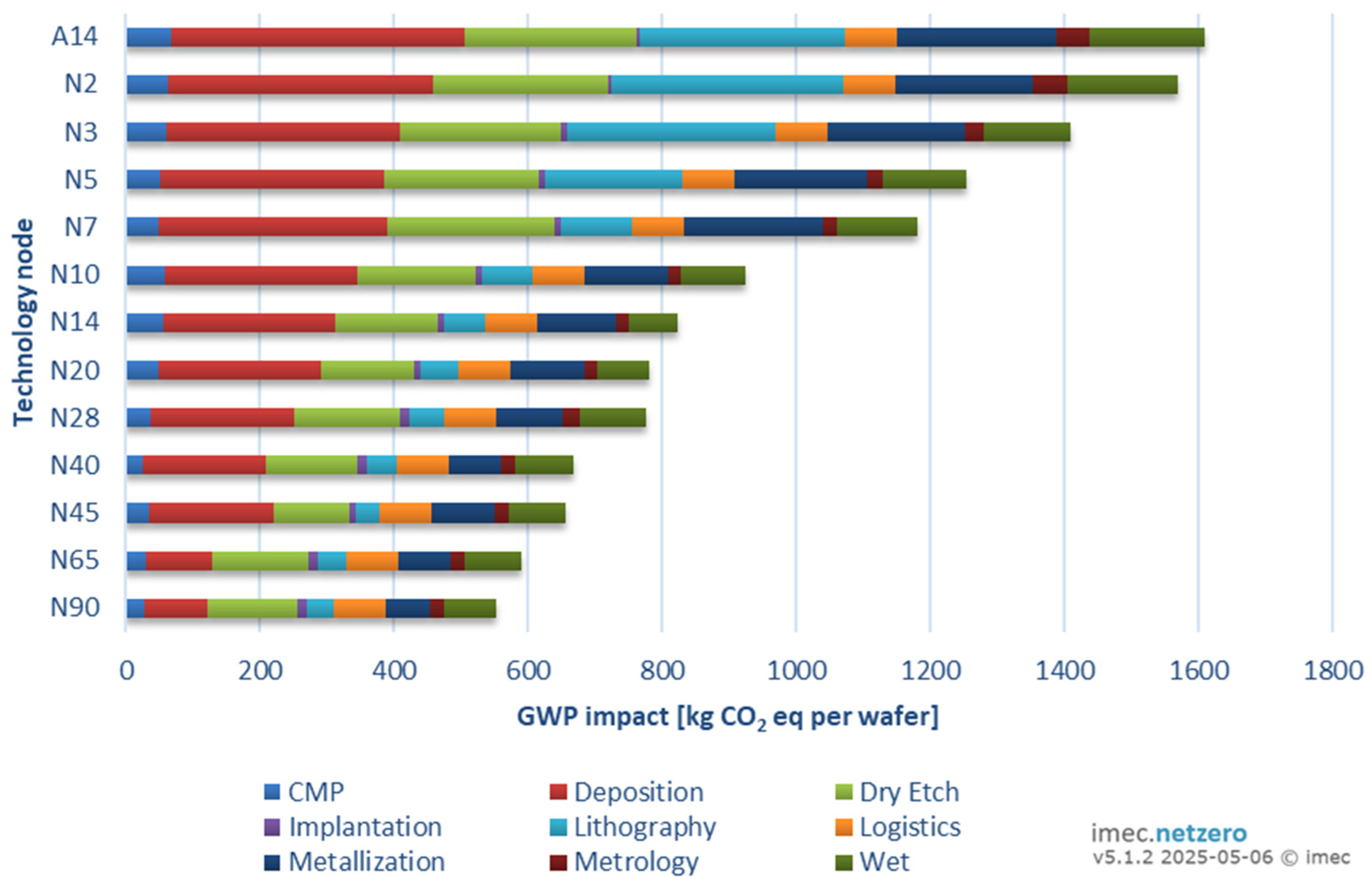

Figure 1 shows a clear trend of increasing environmental impact per wafer as semiconductor technologies advance (N90 to A14), primarily due to the adoption of more energy-intensive equipment and longer, more complex integration flows. This is reflected in both the absolute and relative contributions to the total global warming potential (GWP) across technology nodes. Figure 1 shows the total emissions per technology per class [15]. In nodes ranging from N90 to N10, the four process classes with the highest relative GWP contributions are deposition (up to 31%), dry etch (24%), metallization (18%), and wet (14%). From N90 through N7, lithography contributes a stable 5–9% of total GWP impact per wafer. However, beginning at N5, this contribution rises sharply, reaching 16% at N5 and ~22% at N3/N2, corresponding to the introduction of EUV lithography and indicating its dominant impact at advanced nodes.

Figure 1.

Total GWP impact results for Logic technology nodes N90–A14 per process area using industry average upstream electricity assumptions (CMP = Chemical Mechanical Polishing).

Sustainability efforts are currently underway in several of these critical process areas. For example, work is ongoing to reduce energy consumption and harmful chemical use in EUV lithography through system-level optimization and alternative resist strategies [21,22]. Similarly, deposition and dry etch processes are the focus of research efforts targeting plasma power optimization, chamber redesign, and material substitution to reduce emissions, as described in [23,24,25]. However, the findings from the efforts made so far highlight the complexity and yield-critical nature of these modules, making them more challenging to modify without extensive validation and a risk to device performance [23]. Our work focuses on the class called “Wet”, where process areas such as wet etch, clean, and wet strip can be distinguished.

Wet etching is a chemical process that uses liquid etchants to isotropically remove material from a semiconductor wafer, creating specific patterns and features. Advantages of wet etching processes are as follows: high etch rate—wet etching offers significantly higher etch rates compared to dry etching; high selectivity—wet etchants can be highly selective, allowing precise removal of specific materials without damaging others; cost-effectiveness—wet etching typically requires simpler equipment and lower operating costs compared to dry etching, especially for large-scale production, making it efficient for bulk material removal [26]. Typical materials for applying wet etching processes are silicon, germanium, silicon oxide, silicon nitride, metals, and metal oxides.

Cleaning is essential in semiconductor manufacturing as it removes contaminants and particles from the wafer surface [27]. Cleaning steps ensure that subsequent processes, such as deposition, can be performed accurately and reliably, leading to higher-quality devices with improved performance. This process is used repeatedly during semiconductor device manufacturing and is critical for product yield. Typical cleaning solutions include SC-1 Clean, a mixture of ammonium hydroxide, hydrogen peroxide, and deionized water to remove organic contaminants and particles. SC-2 Clean: A mixture of hydrochloric acid, hydrogen peroxide, and deionized water removes metal contaminants. HF Clean: A dilute hydrofluoric acid solution removes a thin layer of native oxide from the silicon surface. Organic Solvents: For example, isopropanol is used to remove organic residues.

Wet stripping is a chemical process that removes photoresist material from a semiconductor wafer after patterning or rework. This is typically performed using a mixture of strong acids (for example, H2SO4) or organic solvents (for example, N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP).

Wet clean processes, particularly those used for wafer backside cleaning and post-pattern cleans, are often positioned outside the most defect-sensitive process steps [28]. This makes them an ideal target for early sustainability interventions.

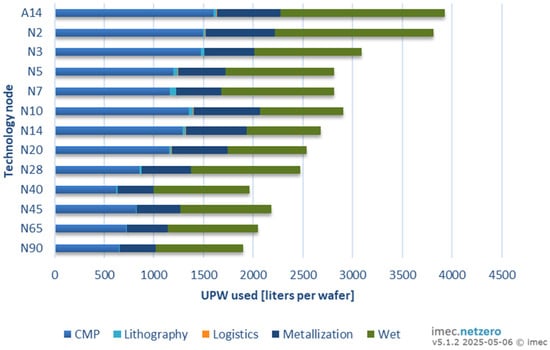

3.1.2. UPW Consumption

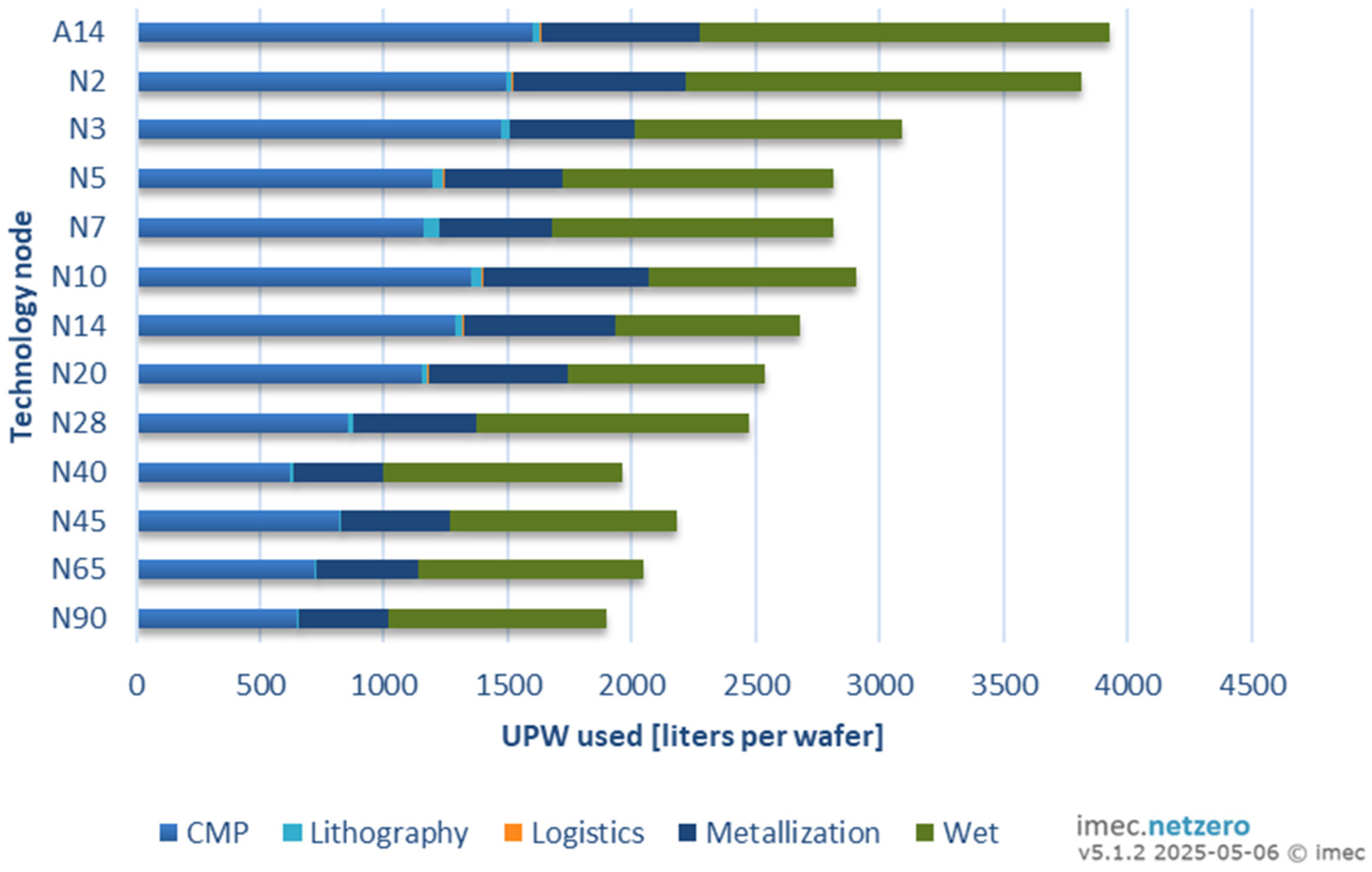

Figure 2 shows the UPW consumption for logic technology nodes N90–A14 for the different process classes in the fab.

Figure 2.

Total UPW consumption for Logic technology nodes N90–A14 per process class (CMP = Chemical Mechanical Polishing).

The top two process classes for UPW consumption are CMP and wet, with ranges between 31 and 48% and 28–49% of total UPW consumption, respectively. Metallization is the third largest contributor to UPW consumption, with a range between 16 and 23. Water consumption in these areas seems to be the most critical initiative for environmental sustainability.

Significant efforts have been directed toward recycling wastewater generated during CMP and wet processes, including the increasing use of segregated drain lines based on contaminant profiles to enable stream-specific treatment and recovery. While such strategies enhance the efficiency of wastewater recycling, emerging research emphasizes the importance of process innovations that inherently require lower volumes of ultrapure water (UPW) without compromising process performance [29,30]. In this regard, this paper presents a single-wafer backside cleaning approach, which reduces UPW use by >50% compared to the conventional method.

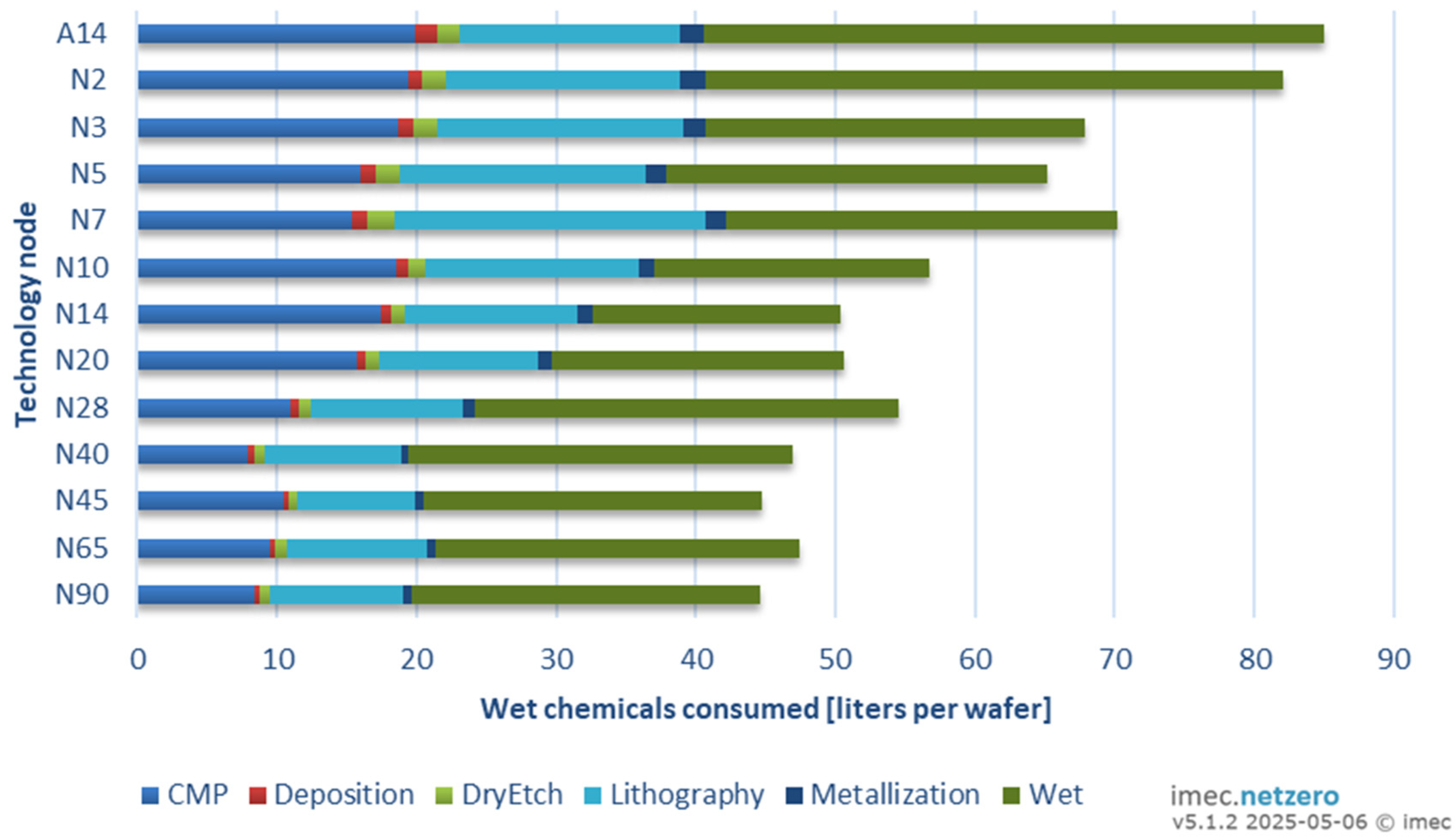

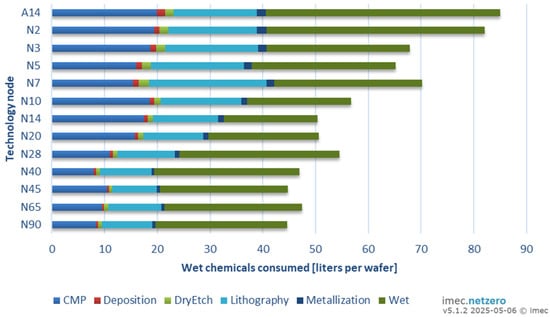

3.1.3. Chemical Consumption

Figure 3 shows that the wet class is the dominant contributor to chemical consumption, accounting for 35–59% of the total chemical consumption of a full flow of a technology node. The second largest consumers of chemicals are CMP and lithography, each ranging from approximately 17–35% and 18–32%, respectively. These three classes, therefore, constitute clean chemical use hotspots within semiconductor manufacturing. Among them, wet processing remains the most critical focus area due to its consistently high absolute contribution, exceeding 50% at several mature nodes (e.g., N90, N65, N40) and remaining a major consumer even at advanced nodes. Given its scale and persistence across node generations, reductions in chemical consumption within wet processing have the greatest potential to yield substantial environmental and resource-efficiency benefits.

Figure 3.

Total chemical consumption for Logic technology nodes N90–A14 per process area (CMP = Chemical Mechanical Polishing).

3.2. Scenario Analysis for Low-Impact Process Solution

One of the primary challenges in advancing sustainable semiconductor manufacturing lies in the rigidity of established process flows, particularly for mature technologies in HVM. Once a process is operational and yields are optimized, fabs are understandably hesitant to modify it due to the high risk of negatively impacting device performance or yield. For this reason, sustainable interventions for existing fabs should initially target process steps that are less critical to electrical performance or defectivity. As mentioned in Section 3.1.1, wet cleaning of the wafer’s backside presents a compelling opportunity. Targeting backside wet cleans enables the implementation of low-impact solutions with minimal risk, making it more likely that fabs will adopt and scale such changes. Once proven in lower-risk modules, similar approaches can later be extended to more sensitive and yield-critical areas through technology development and validation. This strategy allows for a gradual and risk-managed path toward comprehensive sustainability adoption across the manufacturing line.

This study focuses on the single-wafer spin cleaning process traditionally used for backside cleaning, commonly called SCROD [14]. SCROD serves as the baseline in our environmental impact assessment. It operates through a cyclic sequence of oxidation using ozonated water, followed by etching with diluted HF. As a low-impact scenario, we investigate the Hydrofluoric Ozonated Mixture (FOM) [31,32] process, simplifying the cleaning by reducing the required steps while maintaining equivalent cleaning efficiency. The FOM process presents significant novelty in its application as a replacement for the SCROD cycle in single-wafer processing. This transition is challenging in the context of single-wafer spin cleaning due to extremely short chemical contact times. Our study uniquely demonstrates that FOM can achieve equivalent cleaning performance, leading to significant reductions in UPW and chemical consumption. This validates our alternative proposal not only as a greener chemistry but as a pragmatic, low-risk, and quantifiable single-wafer process substitution ideal for retrofitting existing HVM facilities, bringing industrial relevance. Table 1 compares the two single-wafer cleaning processes.

Table 1.

Comparison table of single-wafer cleaning processes: SCROD vs. FOM.

A series of experiments was set up in imec’s fab to compare the technical performance of these two scenarios as a first step of the inventory analysis.

3.2.1. Performance

The SCROD clean has been commonly used as the single-wafer cleaning method since the 90s, when Hattori introduced it at the SONY manufacturing plant [14]. It was a replacement proposal for the most prevalent method: a hydrogen peroxide-based method, namely, the RCA standard cleaning [27]. At that time, SCROD was presented as a significant step towards sustainable processing, reducing HF and UPW consumption. Almost 30 years later, there is a need for a new approach that provides an alternative to SCROD cleaning with the potential to be adopted by HVM fabs. Metal impurity removal efficiency and wafer surface roughness control are essential parameters expected from the backside clean [33,34,35,36,37]. This section compares the performance of SCROD and FOM cleaning processes regarding these parameters.

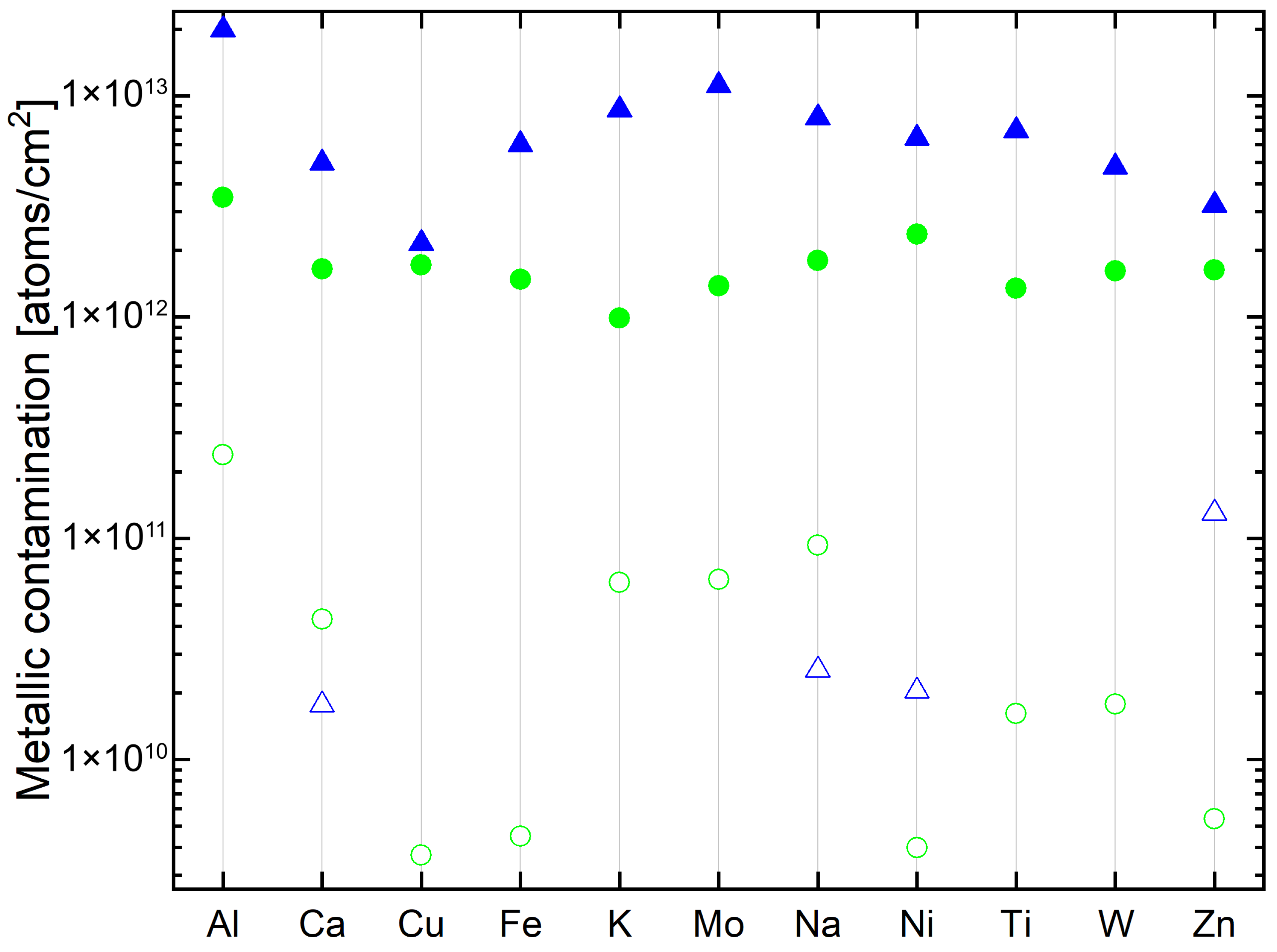

Metal Impurities

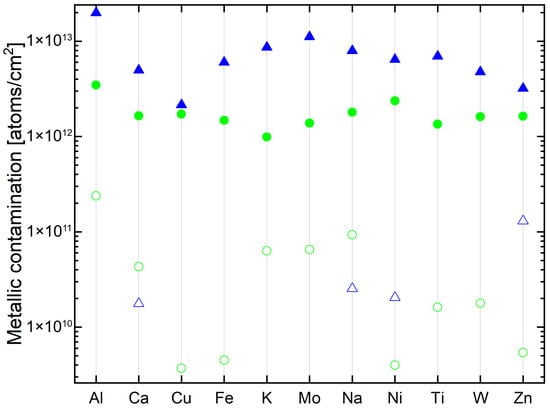

The contaminated wafers (see Section 2.3) containing metal impurities within a range of 1012 to 1013 atoms/cm2 were cleaned using the SCROD and FOM methods. Figure 4 shows the metallic contamination value in atoms per cm2 for the wafers before and after the cleaning process. The wafers with higher contamination levels for each metal were selected for the FOM test (blue triangles in Figure 4). Both cleans show significant cleaning efficiency, reducing concentrations of metals by at least one order of magnitude. The missing points (Al, Cu, Fe, K, Mo, Ti, W) in Figure 4 that represent metallic contamination after FOM clean (empty blue triangles) correspond to a level lower than the limit of detection of the TXRF tool (Al—2.4 × 1011, Cu—3.7 × 109, Fe—4.5 × 109, K—6.3 × 1010, Mo—6.5 × 1010, Ti—1.6 × 1010, W—1.8 × 1010). While overall metal removal efficiency is similar or higher using FOM, SCROD shows better removal efficiency for zinc.

Figure 4.

Efficiency of metallic contaminant removal. Blue triangles (filled): Contamination level of wafers prepared for FOM clean. Green circles (filled): Contamination level of wafers prepared for SCROD clean. Blue triangles (empty): Contamination level of wafers after FOM clean. Green circles (empty): Contamination level of wafers after SCROD clean.

Roughness

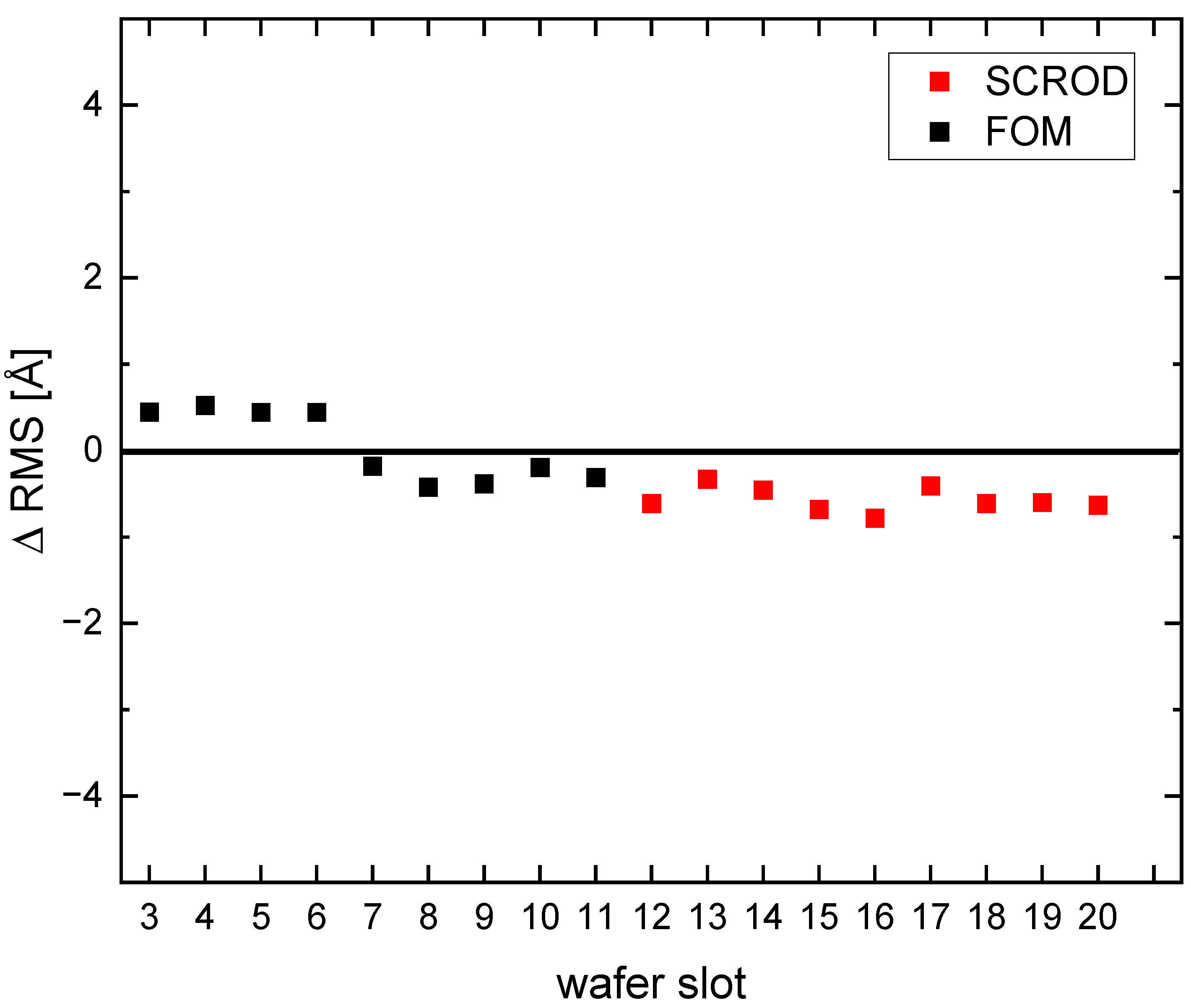

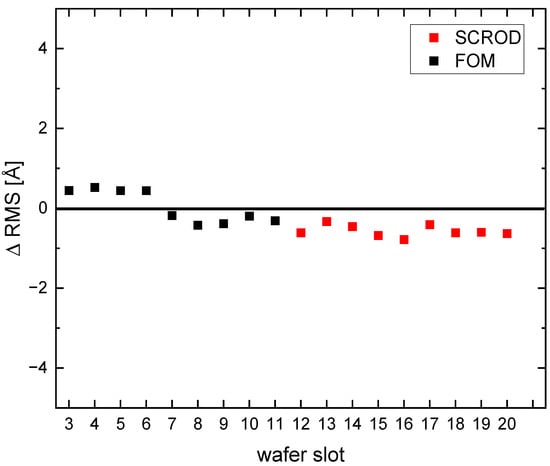

The backside roughness of silicon wafers is important in semiconductor manufacturing, as it impacts both the manufacturing process and the final devices’ performance. In lithography, the backside roughness can affect wafer flatness during chucking, impacting the depth of focus and pattern placement, possibly leading to malfunctioning devices [38]. The roughness can be the source of voids and weak bond strength in the bonding area [39]. The wafer’s surface condition also impacts the adhesion of the metal layers in the backside metallization step [40]. To investigate the impact of the considered cleans (SCROD and FOM), the surface roughness of 18 wafers was measured, of which 9 were then cleaned with SCROD and 9 with FOM. Figure 5 shows the delta between Root Mean Square (RMS) measurements of the 18 wafers in angstroms (Å). Results show that all wafers treated with SCROD (slots 12–20) and five wafers treated with FOM (slots 7–11) experienced reductions from their initial roughness. For the wafers in slots 3, 4, 5, and 6, FOM increased the roughness by around 0.5 angstrom, which is within an acceptable range (0–5 Å) for wafer-to-wafer bonding [41]. Overall, the data obtained show that SCROD and FOM perform equally well as cleaning procedures.

Figure 5.

The delta Root Mean Square (RMS) value is used to quantify the wafer surface roughness of the wafer. Surface roughness was measured before and after the cleaning process (SCROD or FOM).

3.2.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

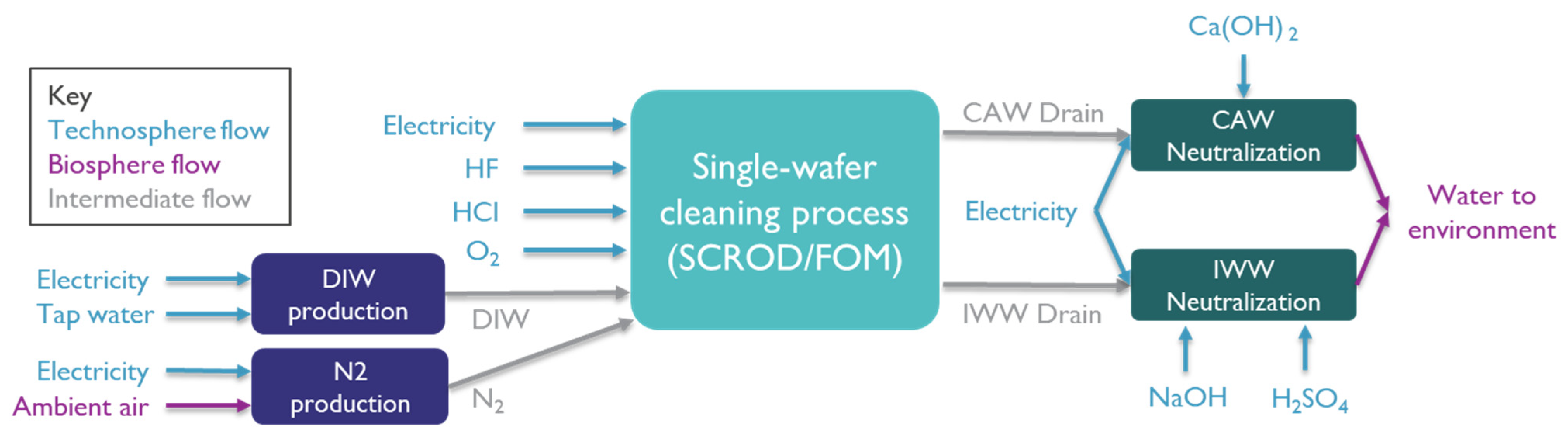

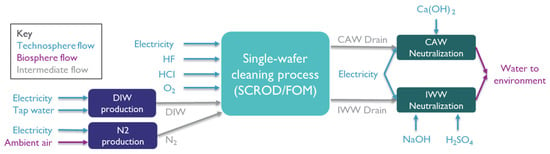

The second goal of this study is to conduct a full LCIA comparing SCROD and FOM cleaning solutions for processing 28 nm logic node wafers. To achieve this goal, an LCI analysis was conducted for the considered cleaning processes. Figure 6 shows the material and energy balance surrounding the single-wafer cleaning process of one wafer. The rectangular processes in Figure 6 occur onsite to either produce a material flow consumed in the single-wafer clean process or treat the output flows that exit the process. The technosphere flows signify materials crossing the system boundary from the technosphere and thus are human-made materials. Biosphere flows move to/from the natural environment. Intermediate flows move between processes within the system boundaries.

Figure 6.

Life cycle system boundaries for single-wafer cleaning process (SCROD/FOM). Technosphere, biosphere, and intermediate flows surrounding the foreground system, which is considered onsite operation. HF: hydrofluoric acid, HCl: hydrochloric acid, O2: oxygen gas, DIW: deionised water, N2: nitrogen gas, CAW: contaminated acid waste, IWW: industrial wastewater, Ca(OH)2: calcium hydroxide, NaOH: sodium hydroxide, H2SO4: sulfuric acid.

Deionized water (DIW) is produced onsite using tap water and electricity as inputs. To generate one liter of DIW, 1.6 L of tap water [12] and 0.009 kWh [42] are required. Nitrogen gas (N2) is separated from the ambient air and purified onsite using 0.25 kWh/m3 electricity [42]. The other inputs of the SCROD and FOM processes are electricity, HF (49%), HCl (35%), and oxygen. The input material flows for the LCI were measured onsite at imec during the experimental phase of the study (see Section 2.3).

There are two output flows from the single-wafer cleaning process: contaminated acid waste (CAW) drain and industrial wastewater (IWW) drain, which are neutralized onsite separately. The CAW drain is treated with 21 kg/m3 of 30% calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2), and the IWW drain is treated with 0.134 L/m3 of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and 0.075 L/m3 sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Both neutralization processes consume 1.78 kWh/m3 of electricity to operate the pumps. The treated water is tested against the local environmental regulations and released to the environment.

The key improvements in the life cycle inventory between the FOM scenario and the baseline SCROD are highlighted in Table 2. Notably, the electricity for the single-wafer cleaning process is reduced by 67% in the FOM scenario. The consumption of HF and HCl is reduced by 59% and 77%, respectively. Tap water consumption is reduced by 31% in the FOM process. When scaled to high-volume manufacturing, where we assume a fab producing N28 Logic wafers at 50,000 wafer starts per month, with 46 backside clean steps per processed wafer, these savings correspond to approximately 4 million kWh of electricity and 28 million liters (28,000 m3) of tap water per year.

Table 2.

Life cycle inventory for technosphere flows provided in amounts per wafer for a single-wafer clean process. The percentage difference is defined by the change in value with respect to the baseline scenario (SCROD).

The FOM scenario produces 775 mL/wafer of CAW compared to 396 mL/wafer in the SCROD scenario, leading to a 96% increase in Ca(OH)2, which is used for CAW neutralization. However, in the FOM scenario, the volume of IWW is significantly reduced, resulting in an overall reduction in wastewater of more than 30%.

3.2.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The technosphere flows in Figure 6 were characterized by mapping a market process from an LCA database (Ecoinvent 3.11). The unit processes selected from the Ecoinvent database were RER, meaning they are regionalized to Europe. This was representative as the imec fab is situated in Belgium. This mapping ensures that all cradle-to-gate impacts associated with the material or energy flow supply are accounted for in the LCIA analysis. Table 3 shows the mapping used in this analysis. SCROD and FOM perform equally as cleaning procedures (Section 3.2.1) and hence can be compared on a functional basis in the following LCA.

Table 3.

Mapping of technosphere flows to an upstream unit process from the LCA database (Ecoinvent v3.11) for characterization.

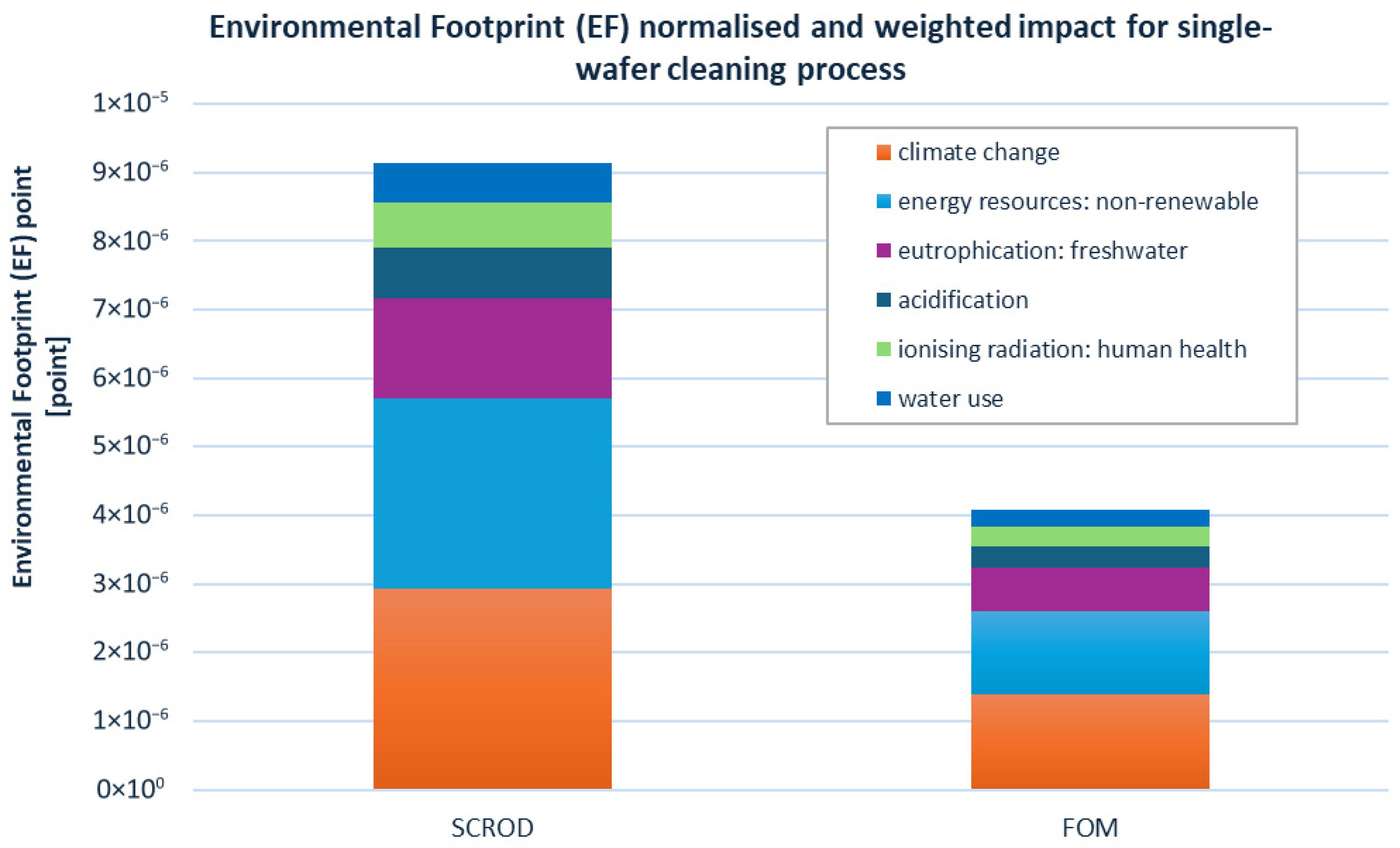

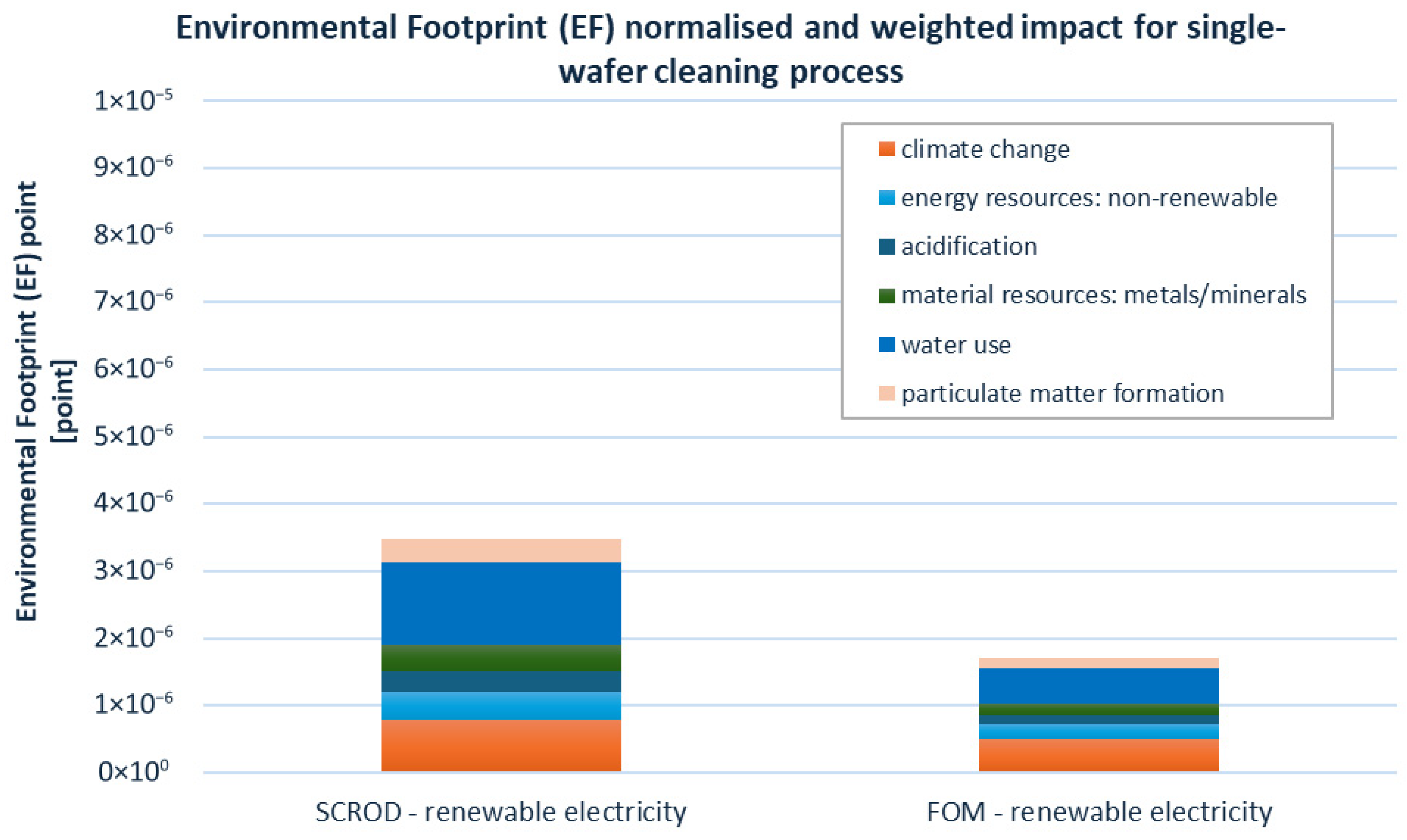

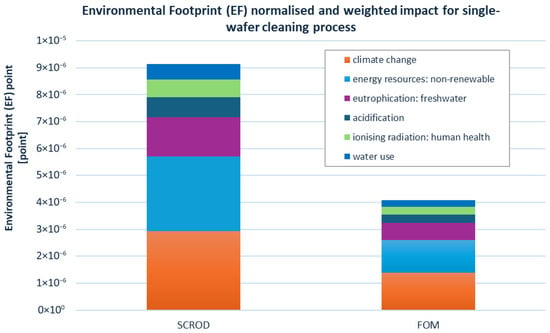

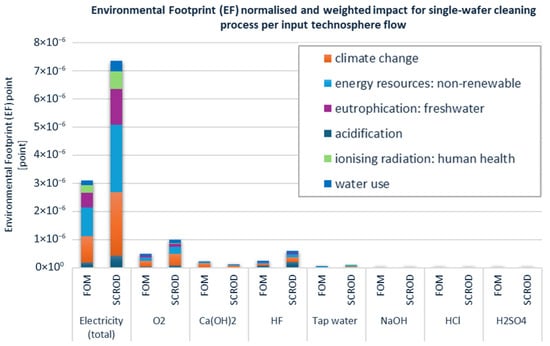

The results in Figure 7 illustrate the impact of the considered single-wafer clean process step for one wafer. The impact is expressed in environmental footprint (EF) points, which aggregate the normalized and weighted scores of 16 impact categories outlined in the EF3.1 LCIA methodology [43]. Figure 7 only displays the six impact categories that constitute 80% of the total impact.

Figure 7.

Normalized and weighted environmental footprint (EF) point for single-wafer cleaning process (per wafer) following the EF3.1 LCIA methodology. Individual contributions of each impact category to the single score are observed using the legend for the impact categories that constitute >80% of the total impact.

The SCROD cleaning process results in a total (sum of all 16 impact categories) annual impact of 1.1 × 10−5 EF points, whereas the FOM cleaning process results in a total impact of 4.9 × 10−6 EF points, demonstrating a 55% impact reduction compared to the baseline. The impact categories ‘climate change’, ‘energy resources: non-renewable’, ‘eutrophication: freshwater’, ‘acidification’, ‘ionising radiation: human health’, and ‘water use’ constitute 83% of the total EF point for both scenarios (9.1 × 10−6 points and 4.1 × 10−6 points for SCROD and FOM, respectively). The respective EF 3.1 proposed weighting of these impact categories is 21%, 8%, 3%, 6%, 5%, 9%, whereby equal weighting of the 16 impact categories results in a factor of 6.25%. This indicates that the impact category ‘eutrophication: freshwater’ is particularly important for this process, as it results in the third most significant impact category, despite its relatively small weighting factor.

The electricity supply constitutes 87% of the impact in the impact category ‘eutrophication: freshwater’, which can be correlated with the fraction of fossil-based electricity in the ‘market group for electricity, medium voltage’ process in the Ecoinvent database. Fossil fuel mining and combustion significantly contribute to eutrophication, a process where excessive nutrients in water bodies lead to algal blooms and oxygen depletion, harming aquatic life. Mining activities release pollutants like nitrogen and phosphorus, while combustion of fossil fuels produces nitrogen oxides that contribute to acid rain and the deposition of nutrients in water.

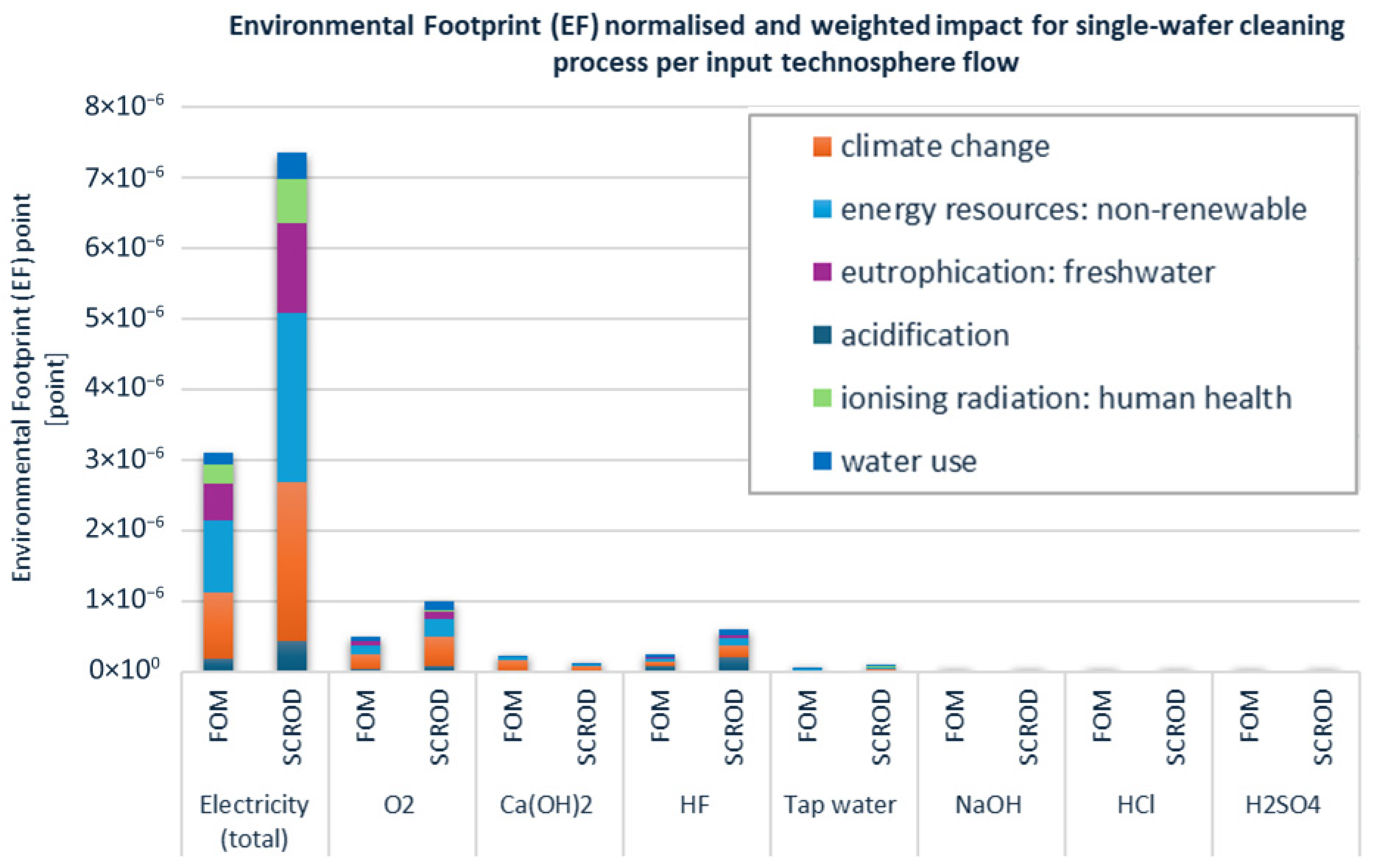

Figure 8 shows that electricity supply is the primary contributor to the environmental impact categories of ‘climate change’, ‘energy resources: non-renewable’, ‘eutrophication: freshwater’, ‘ionising radiation: human health’, and ‘water use’. The single-wafer cleaning process accounts for the majority of electricity consumption, 62% for SCROD and 49% for FOM. This is primarily due to pump operation and ozone generation. Since SCROD is a longer process, it consumes a larger proportion of total electricity demand compared to FOM per wafer cleaned. The second major source of electricity consumption is nitrogen production. Additional significant upstream contributors to environmental impact are the supply of oxygen gas, Ca(OH)2, and HF. In contrast, the impact associated with the supply of tap water, NaOH, HCl, and H2SO4 is minimal, their combined impact accounting for less than 2% of the total impact. FOM shows a reduction in all contributing processes apart from the supply of Ca(OH)2, which corresponds to the increased inventory shown in Table 2.

Figure 8.

The top six impact categories are broken into the contributing upstream processes for the supply of technosphere flows. Results are expressed in EF points per wafer.

Table 2 shows that the electricity consumed during the single-wafer clean process is at least twofold larger than the electricity consumed to supply nitrogen gas and approximately tenfold larger than the electricity demand for the DIW supply. Therefore, to achieve significant environmental improvements, the electricity consumption during this single-wafer clean processing step should be reduced or sourced from a non-fossil-based source. In addition, process timing plays a crucial role in the total environmental impact. The FOM process is faster than SCROD, which increases the wafer throughput. Since both processes operate on the same equipment platform, a higher throughput means that the static electricity and resource consumption of the tool are spread over a greater number of wafers. This results in a lower environmental burden per wafer cleaned. Furthermore, higher throughput not only reduces per-wafer impacts but also brings economic benefits through improved return on investment (RoI) and reduced equipment footprint on the fab floor. However, this increased efficiency may also give rise to rebound effects whereby greater process efficiency and throughput could lead to increased total production, ultimately driving up overall resource consumption and offsetting some of the environmental gains.

3.2.4. Sensitivity Analysis

Given that the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) identified electricity supply as the dominant contributor to overall environmental impacts, both in aggregate and across several individual impact categories, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the influence of sourcing electricity from renewable sources. The objective was to evaluate how the adoption of non-fossil-based electricity would alter the distribution and magnitude of environmental impacts and determine how this shift would affect the relative importance of each impact category.

For this analysis, the Ecoinvent dataset “RER: market for electricity, medium voltage, renewable energy products” was used as a substitute for the original “market group for electricity, medium voltage” applied in Section 3.2.3. The selected dataset represents the Swiss electricity mix derived from renewable sources, of which over 85% is hydroelectric power.

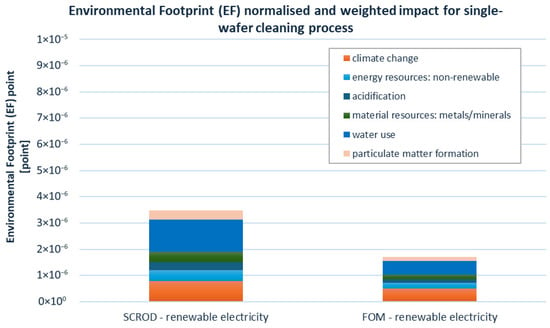

The sensitivity analysis results indicate a substantial reduction in total environmental impact when renewable electricity is adopted (Figure 9). Specifically, the SCROD–renewable electricity scenario exhibited a 63% reduction in total environmental impact (points) compared to the baseline SCROD scenario. Additionally, the FOM–renewable electricity scenario achieved a further 19% reduction relative to the baseline, resulting in a final impact of 2 × 10−6 EF points. The scale of the y-axis in Figure 9 is equal to that of Figure 7 to illustrate this reduction.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of renewable energy results. Normalized and weighted environmental footprint (EF) point for single-wafer cleaning process following the EF3.1 LCIA methodology. Individual contributions of each impact category to the single score are observed using the legend for the impact categories that constitute >80% of the total impact.

Figure 9 presents the environmental impacts, expressed in Environmental Footprint (EF) points, for both renewable electricity scenarios, limited to impact categories contributing more than 80% to the total EF score. These six categories—’climate change’, ‘energy resources: non-renewable’, ‘acidification’, ‘material resources: metals/minerals’, ‘particulate matter formation’, and ‘water use’—jointly account for 86% of the total impact in both scenarios. This varies in comparison to Figure 7, in that the impact categories ‘ionising radiation: human health’ and ‘eutrophication: freshwater’ are no longer significant impact categories for this renewable energy scenario.

The results reveal a shift in the impact profile where fossil-based electricity is replaced with predominantly hydroelectric power. Under the renewable scenarios, water use emerges as the most significant impact category, surpassing climate change, which was previously dominant. The majority of this impact on water use is associated with the hydroelectric supply. This change reflects trade-offs introduced by the upstream environmental profile of renewable electricity sources, where reductions in certain impact categories are offset by increases in others, such as water use. Despite this shift, the overall environmental impact of the electricity supply has substantially reduced—by approximately 83%—when transitioning to a renewable supply.

When extrapolated to HVM, assuming a production scale of 50,000 wafers per month and 46 backside clean steps per wafer, the transition from SCROD to the FOM—renewable energy scenario could result in an estimated reduction of approximately 2400 metric tons of CO2-equivalent emissions per year in the climate change impact category alone. This highlights the synergistic environmental benefit of combining process innovation with renewable energy sourcing. The analysis underscores that, beyond process-level efficiency gains, aligning manufacturing with renewable electricity amplifies emissions reductions and supports broader industry goals toward climate neutrality.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the potential for environmental impact reduction in semiconductor manufacturing by targeting process steps, specifically, backside cleaning, for sustainable innovation. Backside wafer cleaning is a process area within the wet class, which was identified in the initial environmental assessment of full-flow technologies as a hotspot for UPW and chemical consumption, with contributions of up to 59% of total chemical use across multiple technology nodes. By focusing on a process area with lower defectivity sensitivity, the proposed backside cleaning process (FOM) enables the introduction of environmentally improved alternatives to the conventional process (SCROD) without compromising device performance or yield.

LCA based on primary fab-level data from imec’s 300 mm pilot line shows that replacing the conventional SCROD process with FOM reduces total environmental footprint by 55%. This reduction is driven primarily by decreased electricity demand (−67% for single-wafer cleaning), lower use of hazardous chemicals (−59% HF, −77% HCl), and a 31% reduction in ultrapure water consumption. The proposed alternative process (FOM) demonstrates a significant environmental impact reduction and provides a low-risk, high-value solution applicable across a range of semiconductor device manufacturing processes, particularly where a clean wafer backside is critical for advanced lithography, wafer bonding, optimized thermal management, and metrology.

Extrapolated to a high-volume manufacturing facility producing N28 Logic wafers operating at 50,000 wafer starts per month, and assuming 46 backside cleaning steps per processed wafer, implementation of the FOM process could reduce annual tap water consumption by approximately 28 million liters (28,000 m3) and electricity use by 4 million kWh. These resource savings scale significantly when applied to industry-wide production volumes, underscoring the broader sustainability benefits of process substitution in HVM environments.

The sensitivity analysis further revealed that transitioning to a renewable electricity supply—dominated by low-carbon sources such as hydroelectric power—can reduce the total environmental impact of the single-wafer cleaning process by up to 63%. While this shift results in a redistribution of impact categories, with water use becoming more predominant, the net environmental benefit remains substantial. These findings suggest that combining process innovation with renewable energy sourcing could be a highly effective strategy for reducing the environmental footprint of high-volume semiconductor manufacturing. They also emphasize the need for comprehensive life cycle assessments to maximize sustainability gains across all impact categories.

Despite these advantages, the applicability of the FOM single-wafer wet cleaning process is not universal. This study is limited to the silicon surface and further research is required to qualify FOM cleaning process for other material surfaces (e.g., SiN or SiO2). Furthermore, high-throughput HVM lines with tightly optimized cycle times may require more engineering to incorporate FOM without affecting bottleneck modules. These limitations indicate that while FOM represents a promising alternative for many process flows, broader deployment will require device-specific validation and alignment with fab-level integration and throughput requirements.

5. Conclusions

Our study successfully demonstrated a pragmatic, data-driven methodology for advancing sustainable transitions within high-volume semiconductor manufacturing. Focusing on the wafer backside cleaning module, we evaluated the novel single-wafer process, namely FOM, as a direct substitute for the conventional multi-step SCROD process.

Using primary, fab-level data from imec’s 300 mm pilot line, our life cycle inventory analysis quantified the specific environmental advantages of the FOM process:

A 67% reduction in electricity consumption required for the cleaning step, a 59% reduction in Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) use, and a 31% reduction in ultrapure water (UPW) consumption. These benefits result in a total reduction in environmental footprint (EF) points by 55% compared to the conventional SCROD clean. These improvements surpass the performance of existing single-wafer backside-clean approaches and establish a new benchmark for environmentally optimized cleaning processes.

This work provides an HVM-validated blueprint for implementing a low-risk, high-impact process retrofit in a production-relevant environment. The results show that FOM achieves cleaning efficiencies comparable to the conventional SCROD process. Both methods remove metallic impurities by at least one order of magnitude, with FOM frequently lowering contamination below TXRF detection limits (109–1011 atoms/cm2). Backside roughness control is also preserved, with FOM-induced variations remaining within ~0.5 Å, a range acceptable for advanced manufacturing. These findings confirm that the substitution does not introduce measurable performance penalties while enabling meaningful reductions in resource intensity.

By demonstrating equivalent cleaning performance (the same order of magnitude for metal removal efficiency and comparable delta RMS) alongside substantial, quantified resource savings, we provide the concrete, implementable evidence needed to overcome industry hesitancy to change processes and accelerate the adoption of sustainable manufacturing practices globally.

Future implications extend to broader process modules within the wet class and to other cleaning or etching steps where environmental hotspots have been identified. While the FOM method may require adaptation for processes involving sensitive materials or stringent integration constraints, the demonstrated reductions highlight the potential for targeted, data-driven process redesign to accelerate sustainability transitions across the semiconductor industry. Continued work should focus on extending the methodology to additional device architectures, validating long-term tool-level reliability, and assessing compatibility with high-throughput HVM infrastructures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and L.B.; methodology, M.G. and L.B.; validation, H.S., J.V.C., C.R. and S.D.G.; formal analysis, M.G. and L.B.; investigation, M.G., L.B., R.C. and T.V.; data curation, M.G., L.B., R.C. and T.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and L.B.; writing—review and editing, H.S., R.C., T.V., J.V.C., C.R. and S.D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EU Horizon Europe Digital, Industry and Space programme, KDT Joint Undertaking, under grant agreement no. 101096772 (project 14ACMOS) and from the partner funding authority VLAIO.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCIA | Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| UPW | Ultrapure water |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| HVM | High volume production |

| SCROD | Spin cleaning with repetitive use of ozonated water |

| DIW | Deionised water |

| EF | Environmental Footprint |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| CMP | Chemical mechanical polishing |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| TXRF | Total X-Ray fluorescence |

| ICP MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry |

| EUV | Extreme ultraviolet lithography |

| NMP | N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone |

| FOM | Hydrofluoric Ozonated Mixture |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| IWW | Industrial wastewater |

| CAW | Contaminated acid waste |

| ROI | Return on investment |

References

- Copernicus Climate Change Service and World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2025. European State of the Climate 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.24381/14j9-s541 (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- IPCC. Summary for Policy Makers in Climate Change, Synthesis Report: Climate Change. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Global Semiconductor Sales Increase 18.8% in Q1 2025 Compared to Q1 2024; March 2025 Sales up 1.8% Month-to-Month, Semiconductor Industry Association. Available online: https://www.semiconductors.org/global-semiconductor-sales-increase-18-8-in-q1-2025-compared-to-q1-2024-march-2025-sales-up-1-8-month-to-month/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Semiconductor%20Industry%20Association%20(SIA)%2C,year-to-year%20sales%20in%20March**%20*%20Americas%20(45.3%25) (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- George, A.S.; George, A.S.H.; Baskar, T. Edge Computing and the Future of Cloud Computing: A Survey of Industry Perspectives and Predictions. Partn. Univers. Int. Res. J. 2023, 2, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.C.; Kuo, C.Y.; Chen, L.W. Assessing environmental impacts of nanoscale semiconductor manufacturing from the life cycle assessment perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberti, M. Environmental performance and trends of the world’s semiconductor foundry industry. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 1183–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirson, T.; Delhaye, T.P.; Pip, A.G.; le Brun, G.; Raskin, J.P.; Bol, D. The Environmental Footprint of IC Production: Review, Analysis, and Lessons from Historical Trends. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2022, 36, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, N.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Cai, H.; Wu, Y. Environmental data and facts in the semiconductor manufacturing industry: An unexpected high water and energy consumption situation. Water Cycle 2023, 4, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semiconductor Sustainability: Predictions for 2025. Available online: https://www.techinsights.com/blog/semiconductor-sustainability-predictions-2025?utm_source=direct&utm_medium=website (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Boakes, L.; Bardon, M.G.; Schellekens, V.; Liu, I.Y.; Vanhouche, B.; Mirabelli, G.; Sebaai, F.; Winckel, L.; Gallagher, E.; Rolin, C.; et al. Cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment of CMOS Logic Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TSMC. Sustainability Report 2024. Available online: https://esg.tsmc.com/en-US/file/public/2024-TSMC-Sustainability-Report-e.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Wang, Q.; Huang, N.; Cai, H.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y. Water strategies and practices for sustainable development in the semiconductor industry. Water Cycle 2023, 4, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yang, Y. Sustainable Transition of the Global Semiconductor Industry: Challenges, Strategies, and Future Directions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaka, T. Single-Wafer Spin Cleaning with Repetitive Use of Ozonated Water and Dilute HF (“SCROD”). In Cleaning Technology in Semiconductor Device Manufacturing VII; Ruzyllo, J., Hattori, T., Opile, R.L., Novak, R.E., Eds.; The Electrochemical Society: Pennington, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 3–14. Available online: https://www.electrochem.org/semiconductor_cleaning/pv_2001_26.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Methodology-Imec. Netzero. 2025. Available online: https://netzero.imec-int.com/methodology (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Braving the Storm: Navigating an Uncertain Future State of Semiconductors, SEMI, & Kearney PerLab, 2025. Available online: https://www.kearney.com/service/product-excellence-and-renewal-lab/state-of-semiconductors-2025 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Transparency, Ambition, and Collaboration, Semiconductor Climate Consortium, & BCG. 2023. Available online: https://discover.semi.org/transparency-ambition-and-collaboration-white-paper-download-registration.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Dieseldorff, C.G.; Liu, C.-W. World Fab Forecast, SEMI, 2024. Available online: https://www.semi.org/en/products-services/market-data/world-fab-forecast (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Yoon, C.; Kim, S.; Park, D.; Choi, Y.; Jo, J.; Lee, K. Chemical Use and Associated Health Concerns in the Semiconductor Manufacturing Industry. Saf. Health Work 2022, 11, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GIGAFAB® Facilities-Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. Available online: https://www.tsmc.com/english/dedicatedFoundry/manufacturing/gigafab (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Gallagher, E.; Bezard, P.; Boakes, L.; Firrincieli, A.; Rolin, C.; Ragnarsson, L.-Å. Sustainable semiconductor manufacturing: Lessons for lithography and etch. In Proceedings of the Advanced Etch Technology and Process Integration for Nanopatterning XII Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 25–28 February 2023; Volume 12499, p. 124990F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.; Ragnarsson, L.-Å.; Rolin, C. Sustainable Semiconductor Manufacturing: The Role of Lithography. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2024, 37, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehrlein, G.S.; Brandstadter, S.M.; Bruce, R.L.; Chang, J.P.; DeMott, J.C.; Donnelly, V.M.; Dussart, R.; Fischer, A.; Gottscho, R.A.; Hamaguchi, S.; et al. Future of plasma etching for microelectronics: Challenges and opportunities. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2024, 42, 41501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.Y.; Park, J.; Koh, T.; Kim, D.; Woo, J.; Jung, J.; Park, S.J.; Lee, C.; Choi, C. Achievement of Green and Sustainable CVD Through Process, Equipment and Systematic Optimization in Semiconductor Fabrication. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2024, 11, 1295–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Tan, K.; Li, Y. Implementation Principles of Optimal Control Technology for the Reduction of Greenhouse Gases in Semiconductor Industry. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 394, 01031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, L.M.; Tipton, C.M. Chemical Etching of Thermally Oxidized Silicon Nitride: Comparison of Wet and Dry Etching Methods. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1991, 138, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, W.; Puotinen, D.A. RCA Review. 1970. Available online: https://bdt.semi.ac.cn/download/0.46712061542913463.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Li, A. 6 Crucial Steps in Semiconductor Manufacturing, ASML. Available online: https://www.asml.com/en/news/stories/2021/semiconductor-manufacturing-process-steps (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Jeong, H. Approaches to Sustainability in Chemical Mechanical Polishing (CMP): A Review. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2022, 9, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.-C.; Ho, H.-J.; Iizuka, A. Total resource circulation in chemical mechanical polishing wastewater treatment from semiconductor manufacturing industry: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 72, 107619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, C.; Hanich, R.; Honeit, F.; Lißner, A.; Stapf, A.; Kroke, E. Etching Silicon with Aqueous Acidic Ozone Solutions: Reactivity Studies and Surface Investigations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 22349–22357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukazawa, Y.; Miyazaki, H.; Ogawa, Y. Direct replacement cleaning technology based on ozonated water using a single processing tank. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Cleaning Technology in Semiconductor Device Manufacturing, Reno, NV, USA, 3–8 May 1998; pp. 264–271. Available online: https://www.electrochem.org/semiconductor_cleaning/pv_97_35.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Chou, W.-Y.; Tsui, B.-Y.; Kuo, C.-W.; Kang, T.-K. Optimization of Back Side Cleaning Process to Eliminate Copper Contamination. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, G131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balu, E.; Tseng, W.-T.; Jayez, D.; Mody, J.; Donegan, K. Wafer backside cleaning for defect reduction and litho hot spots mitigation: DI: Defect inspection and reduction. In Proceedings of the SEMI Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference (ASMC), Saratoga Springs, NY, USA, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Zanders, W.; Caron, E.; Harumoto, M.; Vandereyken, J.; Hermans, J.; Truffert, V.; Halder, S.; Otten, R.; van Dijk, L.; et al. Track integrated backside cleaning solution: Impact of backside contamination on printing distortions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Patterning Materials and Processes XL Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 26 February–2 March 2023; p. 1249809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussous, L.; Besson, P.; Frank, M.M.; Bourgeat, D. Single Backside Cleaning on Silicon, Silicon Nitride and Silicon Oxide. Solid State Phenom. 2005, 103–104, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, P.; Roure, M.C.; Kachtouli, R.; Jourdan, M.; Gabette, L.; Royer, A.; Loup, V. Backside and Bevel Contamination Removal. Solid State Phenom. 2014, 219, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandereyken, J.; D’havé, K.; Suh, H.S.; Caron, E.; Zanders, W.; Baek, S.; Santos, A.; Satoshi, S.; Harumoto, M. Overlay distortion caused by backside defects: Needs for improved track integrated backside cleaning towards high-NA EUV. In Proceedings of the Advances in Patterning Materials and Processes XLII Conference, part of SPIE Advanced Lithography + Patterning, San Jose, CA, USA, 23–28 February 2025; Volume 13428, p. 134280R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C. The effect of surface roughness on direct wafer bonding. J. Appl. Phys. 1999, 85, 7448–7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.M.; Ler, H.M. Effect of wafer back metal thickness and surface roughness towards backend assembly processes. In Proceedings of the International Electronics Manufacturing Technology Conference (IEMT), Penang, Malaysia, 5–7 December 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Miki, N.; Spearing, S.M. Effect of nanoscale surface roughness on the bonding energy of direct-bonded silicon wafers. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 94, 6800–6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEMI. Guide for Energy; Utilities, and Materials Use Efficiency of Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment, SEMI S23-1021, 2021. Available online: https://store-us.semi.org/products/s02300-semi-s23-guide-for-conservation-of-energy-utilities-and-materials-used-by-semiconductor-manufacturing-equipment (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Bassi, S.A.; Biganzoli, F.; Ferrara, N.; Amadei, A.; Valente, A.; Sala, S.; Ardente, F.; European Commission Joint Research Centre. Updated Characterisation and Normalisation Factors for the Environmental Footprint 3.1 Method; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.