Abstract

Amid growing concerns over fossil fuel depletion and environmental degradation, developing alternative energy sources is imperative. While MoS2-based catalysts are known for their syngas conversion activity, their selectivity toward alcohols remains limited. This study addresses this gap by developing Cu-promoted MoS2 catalysts to enhance alcohol synthesis. The results indicated that the introduction of copper significantly modulates the catalytic performance of MoS2. We demonstrate that incorporating Cu significantly modulates the catalytic properties of MoS2. The optimized catalyst with 9 wt% Cu loading exhibited a CO conversion of 17.9% and a markedly improved total alcohol selectivity of 46.4%, with a space-time yield of 67.6 mg·g−1·h−1. Although Cu addition slightly reduced CO conversion, it markedly improved alcohol selectivity by facilitating active site dispersion, suppressing Fischer-Tropsch side reactions, and stabilizing heteroatomic active phases. Finally, a catalytic mechanism for the synthesis of low-carbon alcohols from syngas on MoS2-based catalysts was proposed based on the catalyst analysis and reaction results.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global energy structure has been constantly adjusting, and the demand for clean energy has been increasing [1]. With the depletion of fossil fuels and the deteriorating atmospheric environment, it has become crucial to find new energy sources that can replace fossil fuels [2]. Against this backdrop, syngas—a key chemical intermediate—has garnered significant attention for its efficient conversion and high-value utilization. In particular, the production of higher alcohols from syngas obtained through coal gasification can not only enhance the utilization efficiency of coal resources but also reduce dependence on imported oil and gas, holding strategic importance for ensuring national energy security [3,4].

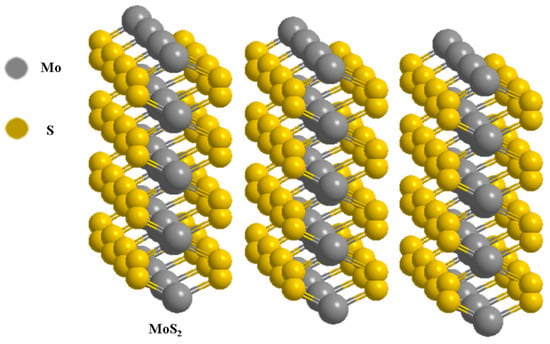

Therefore, the synthesis of higher alcohols from syngas provided a green technological pathway for the coal chemical industry and plays a positive role in promoting the upgrade of the methanol industry and diversifying the energy structure. However, the process still faces technical challenges such as low CO conversion, unsatisfactory selectivity toward target products, and low yield of higher alcohols, which hinder its large-scale industrial application. Thus, designing and developing catalysts with higher activity and selectivity remain key research priorities and challenges in the field of higher alcohol synthesis. Current common catalytic systems mainly include modified methanol catalysts, Fischer-Tropsch synthesis catalysts, noble metal Rh-based catalysts, and molybdenum disulfide-based catalysts, among others. Among them, MoS2, known as an effective catalyst for hydrodesulfurization (HDS) and hydrodenitrogenation (HDN), is widely used in the petroleum industry [5]. MoS2 crystals exhibit a layered structure where Mo atoms are sandwiched between two layers of S atoms via strong covalent bonds, while S-Mo-S layers interact through van der Waals forces (Figure 1). This unique layered structure enables its broad application in catalysis and electrochemistry [6,7,8].

Figure 1.

MoS2-catalyzed syngas conversion to low-carbon alcohol [9].

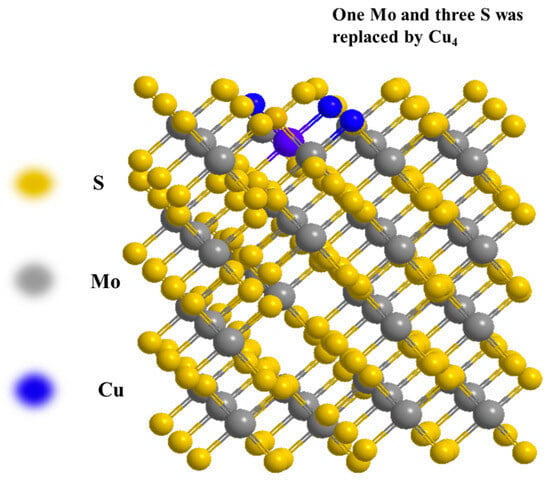

However, the development of monometallic catalysts is constrained by issues such as insufficient active sites, difficulty in forming adjacent dual centers, and challenges in regulating the surface M0/Mn+ ratio [10]. In contrast, bimetallic catalysts have gained broader research and application, primarily due to their synergistic effects, which enable the effective integration of functionally distinct active sites within the same catalytic system. Copper, as a common transition metal, exhibits high activity in syngas conversion reactions [11,12]. Malte Behrens et al. [13] discovered that nano-Cu surfaces modified with ZnOX exhibit high catalytic activity in the synthesis gas-to-methanol reaction. Chen et al. [12] investigated the ethanol formation mechanism over Cu4/MoS2 catalysts compared to pure Cu and MoS2 catalysts. They discovered that one Mo atom and three S atoms in a monolayer of MoS2 could be replaced by a Cu4 cluster, forming a stable Cu4-modified MoS2 catalyst. After modification with Cu4, the original structure of MoS2 was altered, leading to improved catalytic activity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Replacement of MoS2 by Cu clusters to catalyze syngas conversion to low carbon alcohols.

To address the issues of high operating pressure, low product yield, and low selectivity in the current process of syngas conversion to higher alcohols, this study investigated the effects of Cu-modified MoS2 catalysts on the products of syngas-derived higher alcohol synthesis. By combining catalyst characterization data with performance evaluation in a fixed-bed reactor, a catalyst with superior performance was identified. Based on these findings, a catalytic mechanism for syngas conversion to higher alcohols over MoS2-based catalysts was proposed. This study provides a theoretical foundation for future research on both the process and catalysts for syngas conversion to higher alcohols.

2. Experimental

2.1. Catalyst Preparation

Preparation of single-phase Cu-x-MoS2 precursors with different Cu contents by co-precipitation method. We added (NH4)6Mo7O24∙4H2O to 138 mL of ammonia water, while different masses (0, 4.46, 8.34, 11.32, 15.80, 20.76 g) of Cu(NO3)2∙3H2O were added. After the mixture dissolved completely, we slowly added (NH4)2S solution dropwise while stirring, maintaining a molar ratio of molybdenum to sulfur of 1:4. The chemicals used in the experiment are listed in Table 1. The mixture was heated and stirred in a 70 °C water bath until precipitation occurred, after which stirring was stopped. After naturally cooling to room temperature, the resulting precursor precipitates were washed, filtered, and vacuum-dried at 60 °C to obtain the Cu-x-MoS2 precursors with varying Cu contents. Based on the extent of substitution, the as-prepared precursors were designated as Cu-0-MoS2, Cu-5-MoS2, Cu-9-MoS2, Cu-12-MoS2, Cu-16-MoS2, and Cu-20-MoS2, respectively (where 0, 5, 9, 12, 16, and 20 represented the mass fraction of elemental Cu in the catalyst as 0, 5, 9, 12, 16, and 20 wt.%).

Table 1.

Experimental Materials.

2.2. Catalyst Characterization Methods

2.2.1. Low-Temperature Nitrogen Physical Adsorption–Desorption (BET)

Low-temperature N2 adsorption–desorption experiments were employed to analyze changes in pore structure before and after solid acid loading. The experiments were conducted on an ASAP 2020 automated physical adsorption instrument (Micromeritics Instrument Co., Norcross, GA, USA). By integrating pore size distribution curves with adsorption–desorption isotherms, the Brunner−Emmet−Teller specific surface area, micropore volume, pore size, and pore volume of the catalyst were calculated using the t-plot method.

2.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was employed to determine the crystal structure and surface phases of the samples via continuous scanning on a D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer (Bruker Co., Billerica, MA, USA). Using Cu Kα radiation as the source with an incident wavelength λ = 0.15418 nm, the 2θ range was set from 5 to 80°, with a scanning rate of 10°/min. XRD patterns were collected under conditions of 45 kV and 40 mA.

2.2.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis was conducted using a JEM-2100 (JEOL Co., Tokyo, Japan) transmission electron microscope to examine the crystalline structure of the catalyst via electron diffraction. Samples were first dispersed in anhydrous ethanol, homogenised by ultrasonication, and then applied onto a 3 mm copper mesh carbon film. After drying at room temperature, measurements were performed at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV.

2.2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG)

Thermogravimetric analysis (TG) was conducted using a TGA-DSC thermogravimetric analyzer (Mettler-Toledo Co., Greifensee, Switzerland) to assess thermal stability. During analysis, approximately 17 mg of sample was weighed, with nitrogen (N2) serving as the carrier gas (40 mL/min). The temperature reached 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

2.2.5. CO Temperature-Programmed Desorption Analysis (CO-TPD)

CO temperature-programmed desorption analysis (CO-TPD) was conducted on an AutoChem 2920 chemical adsorption instrument (Micromeritics Instrument Co., Norcross, GA, USA). The experiment was carried out in a CO/He atmosphere with a desorption temperature range of 50 to 500 °C. Baseline measurements were acquired under He atmosphere to obtain CO-TPD spectra. Surface active sites were characterized by analyzing the CO adsorption capacity of the catalyst at different temperatures.

2.2.6. H2 Temperature-Programmed Desorption (H2-TPD)

H2 temperature-programmed desorption analysis (H2-TPD) was conducted on an AutoChem 2920 chemical adsorption instrument (Micromeritics Instrument Co., Norcross, GA, USA). The experiment was carried out in a H2/Ar atmosphere with a desorption temperature range of 50 to 500 °C. Baseline measurements were acquired under Ar atmosphere to obtain H2-TPD spectra. Surface active sites were characterized by analyzing hydrogen adsorption capacities on the catalyst surface at different temperatures.

2.2.7. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed using an ESCALAB 250 photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Nexsa Co., Waltham, MA, USA), with spectra acquired under A1 Kα radiation. By subjecting the catalyst samples to XPS analysis, we were able to precisely identify and quantify the chemical states and electronic configurations of elements, thereby gaining a deeper understanding of the chemical composition and electronic properties at the catalyst surface.

2.2.8. H2-Temperature-Programmed Reduction (H2-TPR)

H2-temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) analysis was conducted using an AutoChem chemisorption characterized instrument (Micromeritics Instrument Co., Norcross, GA, USA). Pre-treatment was conducted under an argon atmosphere (30 mL/min), followed by switching to a hydrogen/argon mixture (10% hydrogen). The sample was heated at a rate of 10 °C/min to 800 °C, with data collected throughout the heating process. This enabled investigation of the interfacial interactions between the active component, additives, and the support.

2.3. Catalytic Reaction Test

2.3.1. Experimental Procedure

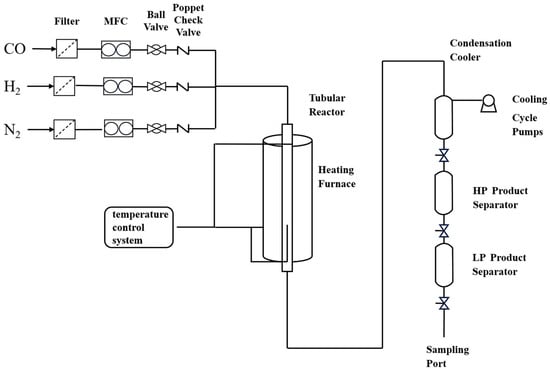

The catalytic performance for syngas conversion to low-carbon alcohols was evaluated using a micro high-pressure fixed-bed reactor. The catalyst precursor was loaded into the center of the reaction tube and pretreated at 400 °C under a H2 atmosphere (50 mL/min) for 8 h [14]. The activity test was conducted by introducing syngas (H2/CO = 2:1) at 350 °C and 6.0 MPa, with a gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 750 milliliters per gram of catalyst per hour. The gas exiting the reactor is cooled via the 0 °C and high-pressure separator, where gas–liquid phase separation occurs. The gaseous products are collected in a gas bag and analyzed by gas chromatography, while the liquid products undergo offline analysis using a gas-chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system and a gas chromatograph (GC). A schematic flow diagram of the experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow of experimental setup for synthesis gas to low-carbon alcohol.

2.3.2. Data Analysis and Performance Evaluation

The mass of both gaseous and liquid reaction products is determined by weighing on a balance, ensuring the entire reaction process complies with the law of conservation of mass. In this paper, the conversion rate of CO and the selectivity of ethanol were used as performance evaluation indicators for the catalyst, and the material was balanced by carbon conservation. The gaseous phase and liquid phase can be analyzed by chromatography to determine the content of each component, and the calculation method is as follows [15]:

- (1)

- CO conversion ratewhere Xi—conversion of component i; ni,in—molar amount of i in feed gas; ni,out—molar amount of i in products.

- (2)

- Total alcohol selectivitywhere Si—selectivity of component i; Nc,i—carbon number of component i; ni,out—molar amount of component i in the products.

- (3)

- Space-Time Yieldwhere STYi—space-time yield of product i; GHSV—gas hourly space velocity; V% (CO)—volume percentage of CO; XCO—CO conversion; Si—selectivity of product i; Mi—molar mass of product i; i—number of carbon atoms in product i.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Catalyst Characterization

3.1.1. BET Characterization

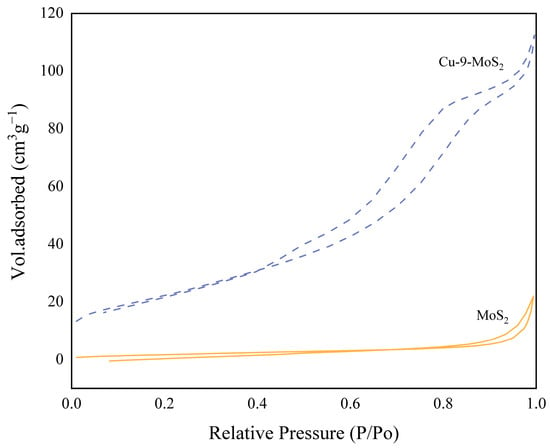

As shown in Figure 4, the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of MoS2-based catalysts reveal that the modified Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst exhibits a Type IV isotherm characteristic, as classified by IUPAC. The presence of a saturation adsorption plateau, inferred from the shape of the hysteresis loop, indicated a well-developed mesoporous structure.

Figure 4.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms for MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts.

Table 2 summarizes the specific surface area, pore volume, and average pore size of the reference MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts. It was found that Cu-9-MoS2 possessed smaller particle sizes and a larger surface area, which led to an increased number of exposed defect sites and the formation of a porous structure. This porous structure facilitated the uniform dispersion of active metal particles [16], enhanced the synergistic effects among various components, and significantly improved the diffusion efficiency of products. Consequently, the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst exhibited higher ethanol selectivity.

Table 2.

Particle size and textural properties of MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts.

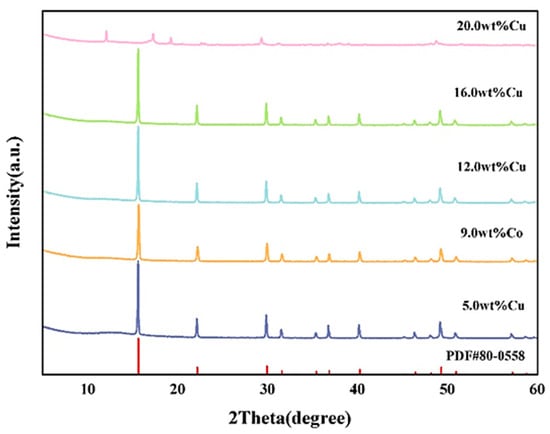

3.1.2. XRD Characterization

Figure 5 showed the XRD patterns of Cu-x-MoS2 precursors with varying Cu loadings compared with the reference pattern of PDF#80-0558 ((NH4)Cu1.07Mo0.93S4). The comparison revealed that when the Cu loading falls within a specific range, the synthesized precursors possessed the standard crystalline structure of (NH4)Cu1.07Mo0.93S4. Furthermore, when the Cu loading is 9.0 wt%, the peak intensities most closely matched those of the standard reference card.

Figure 5.

XRD spectra of Cu-x-MoS2 precursors with different Cu loadings vs. PDF#80-0558.

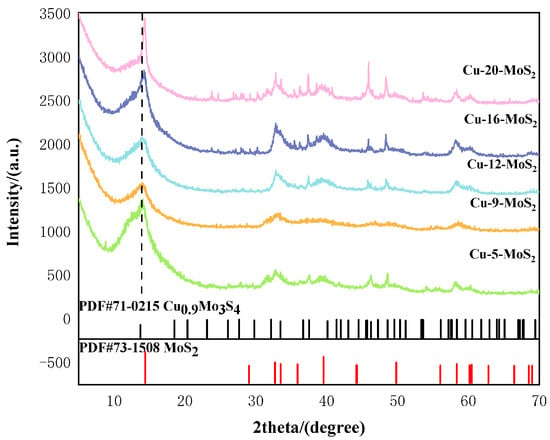

Figure 6 showed the XRD patterns of Cu-x-MoS2 with different Cu loading contents compared with PDF#71-0215 (Cu0.9Mo3S4) and PDF#73-1508 (MoS2). It can be seen from the figure that as the loading content increases, the characteristic peaks of Cu-x-MoS2 exhibited a certain degree of shift. This indicates that the addition of Cu alters the crystal morphology of the original MoS2.

Figure 6.

XRD spectra of Cu-x-MoS2 with different Cu loadings.

No standard diffraction peaks for metallic Cu were observed in the figure, confirming that the nanocrystals of Cu were extremely small. Among them, the three strongest diffraction peaks of Cu-9-MoS2 were located at approximately 2θ = 14.3°, 33.5°, and 58.3°, which closely matched the most intense peaks of the standard reference patterns PDF#71-0215 (Cu0.9Mo3S4) and PDF#73-1508 (MoS2). This indicated the coexistence of both phases in the sample, which were well-crystallized and structurally stable. The construction of these two catalytic active components provided crucial reaction sites, theoretically enabling the occurrence of a synergistic catalytic mechanism.

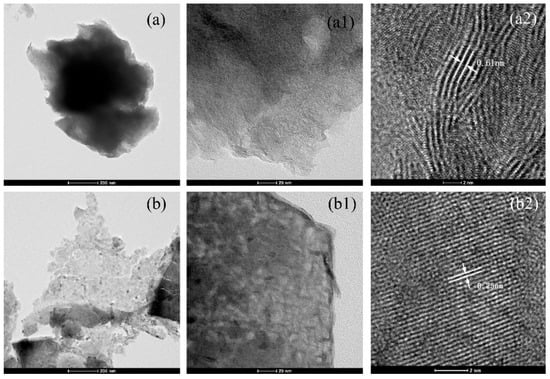

3.1.3. TEM Characterization

Figure 7 shows TEM and HRTEM images of MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts.

Figure 7.

TEM images of the MoS2 (a) and Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst (b) at different resolutions: (a1) 20 nm, (a2) 2 nm; (b1) 20 nm, (b2) 2 nm.

As shown in Figure 7(a1,b1), the original MoS2 exhibited an amorphous structure. The introduction of Cu led to a significant restructuring of the catalyst’s crystal morphology. The Cu-9-MoS2 formed a layered structure comprising 4–6 layers. Its lattice spacing relaxed from 0.61 nm (corresponding to the (002) plane of MoS2) to 0.25 nm (corresponding to the (102) plane of MoS2). This structural reorganization reduced stacking along the 002 direction and diminished the exposure of edge sites [17], while preferentially exposing the active sites of the (102) plane.

These structural modifications were closely linked to the catalytic performance. The markedly different selectivities of MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 toward CH3OH and C2H5OH originated from the aforementioned structural modifications. The unmodified MoS2 catalyst exposed the (002) plane, which favored the formation of methane and methanol [18,19]. In contrast, Cu-9-MoS2 preferentially exposed active sites on the (102) plane (or related interfaces). In combination with liquid product distribution analysis, these structural modifications were found to significantly enhance the selectivity toward higher alcohols.

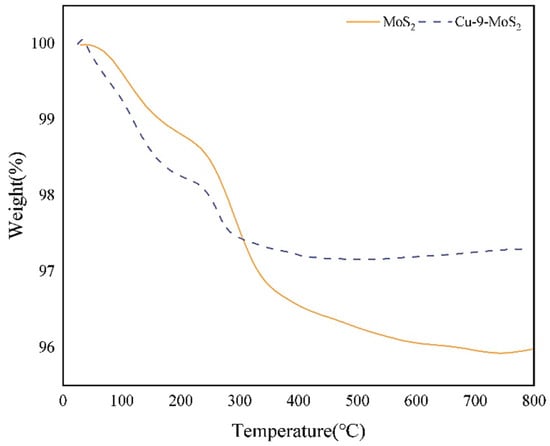

3.1.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

Figure 8 showed the TG curves of MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2. The decomposition trends of both catalysts were broadly similar. No significant weight loss was observed after 300 °C, indicating the high thermal stability of the catalyst material. The weight loss before 200 °C was primarily due to the removal of crystalline water in the catalyst. When the temperature exceeded 250 °C, a distinct secondary weight loss step appeared in the sample, which could be attributed to the thermal decomposition reaction of sulfur-containing groups such as sulfur hydroxyl (-SOH) or sulfhydryl (-SH), generating volatile products such as H2O or H2S. When the temperature reached 350 °C, no sulfur loss was detected, as the S edges served as the main active centers for dissociating and adsorbing hydrogen. This stability likely contributed to suppressing copper sintering and helped maintain the catalyst’s selectivity toward higher alcohols during prolonged reactions.

Figure 8.

TG curves for the decomposition of the MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts.

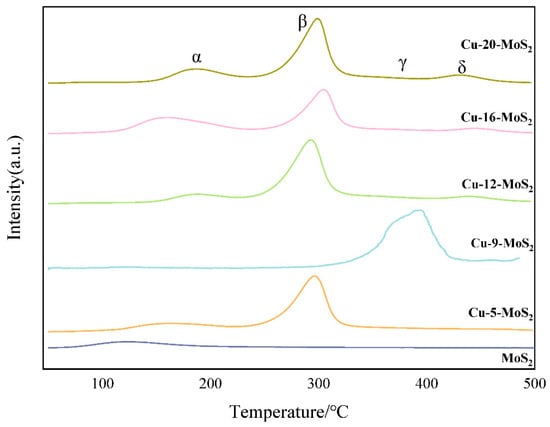

3.1.5. CO-TPD Characterization

As can be seen from Figure 9, four peaks appeared near190 °C (α peak), 300 °C (β peak), 395 °C (γ peak), and 450 °C (δ peak), respectively. Among them, the α peak at 190 °C was a weak physical adsorption CO desorption peak on the catalyst surface; The β peak at 300 °C corresponded to the non-dissociated adsorption-CO desorption peak, which is a medium-intensity adsorption; The γ peak at 395 °C and the δ peak at 450 °C belonged to the dissociation adsorption CO desorption peak [20], which is a strong adsorption. It was observed that the CO-TPD profile of the MoS2 catalyst showed no CO desorption peaks, indicating that the CO adsorption capacity of the MoS2 catalyst is weak, which is unfavorable for CO activation. In contrast, the Cu-x-MoS2 catalysts exhibited characteristic CO desorption peaks across multiple temperature ranges. This indicated the introduction of Cu significantly enhanced the adsorption diversity on the catalyst surface. This phenomenon was primarily attributed to the multi-scale active centers constructed jointly by the unique defect structure at the edges and corners of Cu nanocrystals and the synergistic heteroatomic effect at the heterogeneous interfaces. Among the catalysts, Cu-5-MoS2, Cu-12-MoS2, Cu-16-MoS2, and Cu-20-MoS2 showed relatively prominent β peaks, suggesting that CO adsorption on these catalysts is predominantly non-dissociative. Conversely, Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst exhibited a distinct γ peak, indicating that CO adsorption on this catalyst was predominantly dissociative and relatively strong [21]. Combining this with the mechanism of lower alcohol formation, the stronger adsorption centers on the catalyst were key determinants of the CO conversion rate and selectivity towards higher alcohols [22]. Thus, catalysts exhibiting more dissociative CO adsorption theoretically promote the possibility of methane and methanol formation, yet this pathway is also essential for ethanol production. Consequently, the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst should exhibit higher selectivity towards C2+ alcohols.

Figure 9.

CO-TPD profiles of MoS2 and Cu-x-MoS2 with different Cu loading.

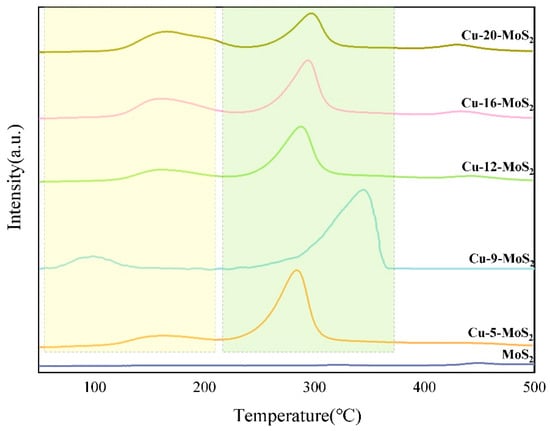

3.1.6. H2-TPD Characterization

Figure 10 shows the H2-TPD spectra of Cu-x-MoS2 catalysts with different Cu contents. Each Cu-x-MoS2 catalyst showed two H2 desorption peaks at 100–400 °C, and the MoS2 catalyst had the smallest area of hydrogen desorption peak. The low-temperature peaks at around 60–230 °C are associated with physical adsorption or weak chemical adsorption of hydrogen, and the high-temperature peaks at around 250–380 °C correspond to enhanced chemical adsorption sites.

Figure 10.

H2-TPD profiles of MoS2 and Cu-x-MoS2 with different Cu loading.

As shown in Figure 10, with the increase in Cu content, the low-temperature peak area of the catalyst gradually increases. The order of peak areas follows: Cu-20-MoS2 > Cu-16-MoS2 > Cu-12-MoS2 > Cu-9-MoS2 > Cu-5-MoS2 > MoS2. Among the high-temperature peaks, the hydrogen desorption of the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst was the highest and the desorption peak area was the largest. The observed decrease in Mo 3d binding energy revealed by XPS characterization, combined with theoretical analysis, indicates that the formation of the Cu0.67Mo6S9.15 active phase induces a significant electron transfer effect: valence electrons from Cu species spill over into Mo orbitals, leading to a reduction in the Mulliken charge density on the Cu surface. This electron reconfiguration enhances the chemical adsorption capacity of Cu sites for hydrogen, providing a theoretical basis for the increase in desorption temperature. Among them, Cu-9-MoS2 presented a single high-intensity desorption peak near 340 °C, indicating the formation of a more uniform hydrogenation active site on its surface, which is highly consistent with the strong interaction structure characteristics of Cu-Mo revealed by XRD and TEM.

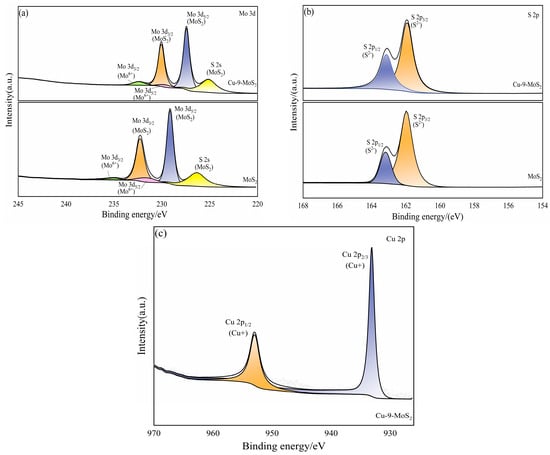

3.1.7. XPS Characterization

As shown in Figure 11a, the Mo existed in both MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts in both Mo4+ and Mo6+ valence states. Cu doping induced the binding energies of Mo6+ and Mo4+ to redshift from 229.12 eV and 231.54 eV to 229.08 eV and 231.54 eV, respectively, indicating an increase in the electron cloud density of Mo sites. Combined with the data in Table 3, the addition of Cu significantly increased the relative content of Mo4+ by facilitating electron transfer. A similar shift was observed for S2−, whose binding energy decreased from 161.96 eV in MoS2 to 161.93 eV in Cu-9-MoS2. The Cu 2p3/2 peak was located at 932.5 eV and the Cu 2p1/2 peak at 952.5 eV, with no satellite peaks present. This conformed to the typical signal for Cu+. Therefore, the predominant active Cu species in Cu-9-MoS2 was electron-deficient Cu+, thereby maintaining charge balance (Figure 11c). From Table 3, it was also evident that the addition of the Cu promoter modulated the relative content of low- and high-valence Mo species, favoring the formation of Mo4+. The ethanol synthesis pathway required a dynamic balance of two types of active sites: Mo6+ was used to dissociate CO to form the *CHX intermediate, while Mo4+ or Cu-deficient sites promoted the adsorption of CO molecules to form the *CO species [9].

Figure 11.

XPS spectra and decomposed XPS spectra of Mo 3d (a), S 2p (b) and Cu 2p (c) of MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts.

Table 3.

Decomposed XPS data of Mo 3d for MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 catalysts.

The synergistic ratio of Mo4+ and Mo6+ in Cu-9-MoS2 optimized the proportion of bifunctional sites, thereby driving the reaction pathway from hydrocarbons to alcohol compounds. Thus, the formation of the Cu0.67Mo6S9.15 active phase was key to improving the alcohol selectivity. Excess Cu introduction led to partial coverage of active sites by inactive Cu complexes, as the CO desorption area (Figure 9) and H2 adsorption capacity (Figure 10) decreased with the increase in Cu loading.

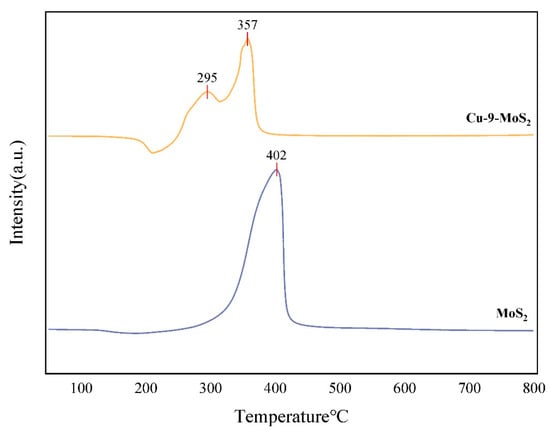

3.1.8. H2-TPR Characterization

Figure 12 showed the H2-TPR spectra of the catalysts MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2. The MoS2 catalyst showed a reduction peak at 400 °C. The Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst showed two reduction peaks at 295 °C and 357 °C. The reduction peak at 357 °C was attributed to Mo, and the reduction peak at 295 °C was attributed to Cu [23,24]. The occurrence of all reduction peaks below 400 °C indicated that both catalysts could be fully activated under the reduction conditions used. The introduction of Cu notably lowered the reduction temperature of Mo, suggesting enhanced reducibility. During reduction, Cu acted as an electron donor and facilitated the dissociative adsorption of H2, leading to a hydrogen spillover effect. This spillover accelerated the reduction in Mo sites and promoted the formation of a synergistic Cu–Mo–S interfacial structure. By precisely regulating the Cu/Mo atomic ratio (Cu0.67Mo6S9.15), a lattice parameter-matched heterostructure was formed. This structure effectively weakened the Mo–S bond strength and provided a more favorable electronic environment for catalytic reactions [25,26].

Figure 12.

H2-TPR profiles of MoS2 and Cu-9-MoS2 with different Cu loading.

3.2. Catalytic Reaction Result

In this test, Cu-x-MoS2 catalysts were prepared by the co-precipitation method with Cu addition. The effects of Cu doping on the physicochemical and catalytic properties in syngas conversion to low-carbon alcohols were investigated. The catalytic evaluation was carried out under fixed conditions: temperature of 350 °C, pressure of 6.0 MPa, gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 750 mL·g−1·h−1, and V(CO)/V(H2) = 2.

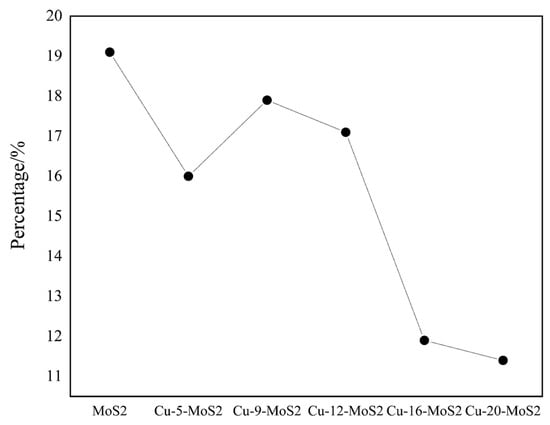

Figure 13 showed the CO conversion rate versus Cu loading. An appropriate amount of Cu formed a stable Cu0.67Mo6S9.15 active phase, which promoted the activation of CO and H2 and enhanced the conversion rate. However, excessive Cu inhibited the growth of the MoS2 (002) crystal plane, reduced the number of active S sites on the surface, weakened the H2 activation capability, and led to a decrease in the conversion rate.

Figure 13.

CO conversion curve of Cu-x-MoS2 catalyst with Cu loading (T = 350 °C, P = 6.0 MPa, GHSV = 750 h−1).

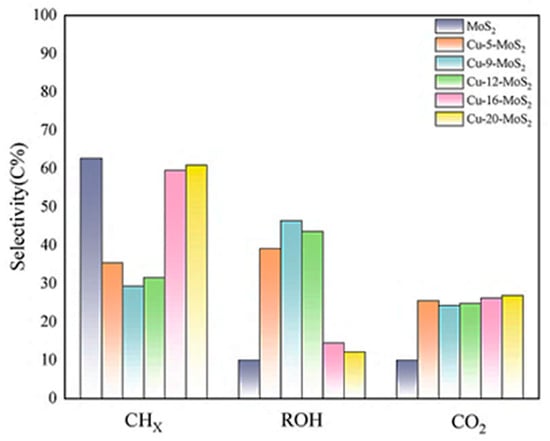

Figure 14 presented a bar chart of the product distribution for Cu-x-MoS2. It revealed that Cu-9-MoS2 and Cu-12-MoS2 catalysts exhibited high total alcohol selectivity. This trend indicated that Cu incorporation increased the catalyst’s specific surface area, promoted highly dispersed component distribution, and facilitated the formation of strong intercomponent interactions [27]. Thereby significantly enhancing the catalyst’s adsorption capacity for both CO and H2.

Figure 14.

Major product distribution of Cu-x-MoS2 catalysts.

As shown in Table 4, although MoS2 catalyst exhibited high CO conversion rates, their products were primarily hydrocarbons. Following the introduction of Cu as a co-catalyst, the CO conversion rate decreased, yet the overall alcohol selectivity markedly improved. The overall alcohol space-time yield exhibited a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with increasing Cu loading. Comprehensive analysis indicated that the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst exhibited the highest total alcohol selectivity and an optimal space-time yield (STY) of 67.6 mg·g−1·h−1, demonstrating the best overall catalytic performance.

Table 4.

Performance evaluation results of MoS2 and Cu-x-MoS2 under different copper loading.

- Reaction condition: T = 350 °C, V(CO)/V(H2) = 2, GHSV = 750 mL·g−1·h−1.

- STY: Space time yield.

- CHX: Hydrocarbons.

- ROH: Alcohols.

- MeOH: Methanol.

- EtOH: Ethanol.

- C3+OH: Alcohols with carbon numbers of more than two.

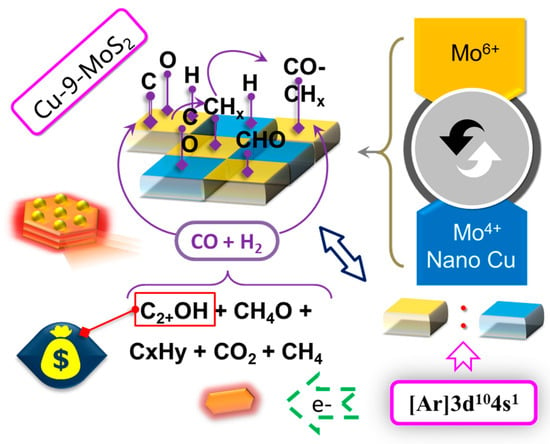

3.3. Catalytic Mechanism of Syngas to Low-Carbon Alcohols

Based on the characterization and activity evaluation results of the above catalysts, the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst was selected. By analyzing the evaluation results of Cu-9-MoS2 catalyzing syngas to produce low-carbon alcohols, the surface reaction mechanism was inferred, and the synergistic effect of Cu0.67Mo6S9.15 active interface on the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst was explored.

Zhang et al. [28] investigated a Cu/β-Mo2C model system using density functional theory (DFT), which revealed the interfacial catalytic mechanism promoting the formation of C2 oxygenates during syngas conversion. Theoretical calculations demonstrated that interfacial active sites of the Cu-Mo2C interface, as well as the pure Mo2C surface, could generate the *CHO intermediate, while the Cu surface only stabilized the *CO species. The enriched reactive electrons at the Cu-Mo interface significantly enhanced the electron occupation of the CO antibonding orbitals, promoting the dissociative adsorption of CO and reducing the activation energy for *CHO formation. Dynamic reaction path analysis indicated that *CHO at the interface tended to rapidly cleave into *C and surface hydroxyl groups, followed by hydrogenation to form *CH; whereas *CHO migrating to the Cu surface underwent stepwise hydrogenation to *CH2O or *CHOH, eventually converting to methanol. The catalytic advantage of the interface then became apparent: Notably, the *CH generated at the interfacial region faced high energy barriers for subsequent conversion to *CH2, *CH3, and *CH4 (reaching 120.8, 124.8, and 285.4 kJ/mol, respectively), significantly suppressing the methanation pathway. Instead, it preferentially coupled with undissociated *CHO to form *CHCHO (Ea = 51.2 kJ/mol), making *CHCHO a key intermediate for ethanol synthesis. Furthermore, *CH2 generated on the Mo2C surface could couple with *CO adsorbed on Cu sites to form *CH2CO, thereby opening an additional pathway for C2 oxygenate formation. Comparing the activation energies for methanol formation (132, 123.5, and 376.7 kJ/mol for Cu (111), Mo2C, and the Cu-Mo interface, respectively) and *CH3 formation (145.6, 117.7, 124.8 kJ/mol) revealed that non-interfacial elemental Cu and Mo2C favored the production of methanol or hydrocarbons. These calculation results corresponded well with the evaluation results for Cu-MoS2 in Table 4, leading to the inference that the catalytic mechanism of Cu-MoS2 was similar to that of Cu/β-Mo2C.Therefore, the reaction mechanism for the catalytic conversion of syngas to higher alcohols over the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst primarily involved the following three aspects: initial CO activation, generation of *CHX (x = 1–3), and coupling of CHO/CO with *CHX.

Based on the intrinsic reaction pathways of MoS2 and following the principle of minimum energy barrier, CO and H2 initially formed *CHO, which was sequentially hydrogenated to *CH2OH. This then cleaved into *CH2 and a surface hydroxyl group (Ea = 91.2 kJ/mol), followed by continuous hydrogenation forming the byproduct CH4. Only a small amount of *CH2OH underwent hydrogenation via a higher energy barrier (Ea = 120.9 kJ/mol) to generate methanol. Consequently, pure MoS2 catalyst was unsuitable for syngas conversion to higher alcohols, which was also confirmed by the evaluation results (Table 4). In contrast, the Cu-modified Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst significantly enhanced ethanol selectivity, indicating a strong synergistic effect between Cu and Mo. A charge-enriched region formed at the Cu0.67Mo6S9.15 active interface promoted C–O bond cleavage to form *CHX, enabling rapid coupling of *CO and *CHO with them to form CHXCHO/CHXCO ethanol intermediates. Figure 15 shows a schematic diagram of the proposed surface reaction mechanism for higher alcohol formation from syngas over the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst, where one type of active site catalyzed the dissociative adsorption of CO to generate the key CHX intermediates, while another type of weak active site adsorbed molecular CO; their synergistic action promoted the formation of higher alcohols, especially ethanol. This study provided a scientific basis for the subsequent modified design and optimization of the Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst for syngas conversion to C2 oxygenates.

Figure 15.

Reaction mechanism of generating low carbon alcohols from syngas over Cu-9-MoS2 catalyst.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the performance of Cu-x-MoS2 catalysts with different Cu loadings in a high-pressure fixed-bed micro-reactor, using a CO/H2 mixture as feedstock, under conditions of 350 °C, 6.0 MPa, and 750 h−1 for the synthesis of low-carbon alcohols from synthesis gas. The results showed that the catalyst performance was optimal when the Cu loading was 9 wt%, with a CO conversion rate of 17.9%, a total alcohol selectivity of 46.4%, and a liquid phase yield of 67.6 mg·g−1·h−1. Systematic characterization revealed that the introduction of the second co-catalyst Cu formed a stable heteroatom active phase, effectively promoting catalyst component dispersion, inhibiting F-T synthesis, significantly increasing specific surface area and pore volume, and providing more active sites for the reaction. Compared with the reference catalyst MoS2, the addition of an appropriate amount of Cu co-catalyst slightly reduced the CO conversion rate but significantly improved the total alcohol selectivity and increased the yield of the target product. Finally, based on catalyst analysis and reaction results, a catalytic mechanism for the conversion of synthesis gas to low-carbon alcohols using a MoS2 catalyst was proposed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. and J.Z.; Methodology, P.S., J.Z. and R.T.; Validation, P.S. and Y.T.; formal analysis, Z.S.; Investigation, P.S., L.W. and L.H.; Resources, R.T., Y.T. and J.Z.; Data curation, L.W. and P.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, R.T. and P.S.; Writing—review and editing, R.T., Z.S. and J.Z.; Visualization, R.T., P.S. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

CNPC Innovation Found (No. 2022DQ02-0402), Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (No. 2024JC-YBMS-085), State Key Laboratory of Heavy Oil Processing (No. SKLHOP202403001). and the Graduate Student Innovation and Practical Ability Training Program of Xi’an Shiyou University (No. YCX2412026).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lingying Wang was employed by the China Petroleum Engineering & Construction Corp, North China Company, and the author declares that there are no competitive financial interests. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, H.J.; Liu, J.; Yan, B.B.; Yao, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, G. ZnO–ZrO2 coupling nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube bifunctional catalyst for co-production of diesel fuel and low carbon alcohol from syngas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 63, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.X. Preparation of Loaded Molybdenum Carbide Catalysts for Syngas to Low Carbon Alcohols and Its Reaction Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Henan University of Technology, Jiaozuo, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.B.; Luan, C.H.; Cui, Y.; Deng, X.; Huang, W. Effect of Fe on the synthesis of low carbon alcohols over CuZnAl catalysts by complete liquid phase method. Nat. Gas Chem. Ind. 2016, 41, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.M.; Zheng, C.Z.; Li, Y.F.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, A.; Wang, Y. Preparation of Ni-modified Cu-Fe-based catalysts and their performance in CO hydrogenation to low-carbon alcohols. Mod. Chem. Ind. 2018, 38, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, X.Y.; Zeng, F.; Cao, H.T.; Cannilla, C.; Bisswanger, T.; de Graaf, S.; Pei, Y.; Frusteri, F.; Stampfer, C.; Palkovits, R.; et al. Enhanced C3+ alcohol synthesis from syngas using KCoMoSX catalysts: Effect of the Co-Mo ratio on catalyst performance. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 272, 118950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Meng, X.C.; Zhang, Z.S. Recent development on MoS2-based photocatalysis: A review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2018, 35, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.B.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Y. Surfactant-assisted preparation of Mo-Co-K sulfide catalysts for the synthesis of low-carbon alcohols via CO2 hydrogenation. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 10, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.X.; Mosallanezhad, A.; Sun, D.; Lei, X.; Pei, X.L.; Wang, G.; Qian, Y. Applications of MoS2 in Li–O2 Batteries: Development and challenges. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 5613–5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, M.; Pham, G.; Sunarso, J.; Tade, M.O.; Liu, S. Active Centers of Catalysts for Higher Alcohol Synthesis from Syngas: A Review. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7025–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.X.; Weng, Y.J.; Yang, S.C.; Meng, S.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Y. Research progress of catalysts for synthesis of low-carbon alcohols from synthesis gas. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 6163–6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, M.B.; Goswami, A.; Felpin, F.X.; Asefa, T.; Huang, X.; Silva, R.; Zou, X.; Zboril, R.; Varma, R.S. Cu and Cu-based nanoparticles: Synthesis and applications in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3722–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhao, J.; Ling, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, B. The active site of ethanol formation from syngas over Cu4 cluster modified MoS2 catalyst: A theoretical investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 540, 148301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.; Studt, F.; Kasatkin, I.; Kühl, S.; Hävecker, M.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Zander, S.; Girgsdies, F.; Kurr, P.; Kniep, B.L.; et al. The Active Site of Methanol Synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 Industrial Catalysts. Science 2012, 336, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, W.; Shen, Z.; Li, G.; Kang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G.-C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Carbon nanotube-supported bimetallic Cu-Fe catalysts for syngas conversion to higher alcohols. Mol. Catal. 2019, 479, 110610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.H.; Pfeifer, P.; Dittmeyer, R. One-stage syngas-to-fuel in a micro-structured reactor: Investigation of integration pattern and operating conditions on the selectivity and productivity of liquid fuels. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.N.; Mu, X.L.; Zhao, L.; Fang, K. Effect of KCoMoS2 catalyst structures on the catalytic performance of higher alcohols synthesis via CO hydrogenation. Catalysts 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Xi, X.Y.; Cao, H.T.; Pei, Y.; Jan Heeres, H.; Palkovits, R. Synthesis of mixed alcohols with enhanced C3+ alcohol production by CO hydrogenation over potassium promoted molybdenum sulfide. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 246, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, J.L.; Hu, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, H.; Gu, X. Enhanced catalytic performance and promotional effect of molybdenum sulfide cluster-derived catalysts for higher alcohols synthesis from syngas. Catal. Today 2018, 316, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, C.K.; Ong, S.W.D.; Du, Y.H.; Kamata, H.; Choong, K.S.C.; Chang, J.; Izumi, Y.; Nariai, K.; Mizukami, N.; Chen, L.; et al. Direct methanation with supported MoS2 nano-flakes: Relationship between structure and activity. Catal. Today 2020, 342, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.S.; Guo, Q.S.; Yu, J.; Han, L.; Lu, G. Effect of Ce addition on the performance of Cu-Fe/SiO2 catalyzed syngas to low-carbon alcohols. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2011, 27, 2639–2645. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.H.; Hao, S.H.; Li, S.S.; Huang, W. The effect of pH value on the catalytic synthesis of C(2+) alcohols in the preparation process of CuZnAl-type hydrotalcite. Acta Pet. Sin. Pet. Process. Sect. 2018, 34, 716–722. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Che, Y.; Zhang, H. The effect of Co-modified Mn/Cu/MgO catalyst on the synthesis of mixed alcohols from synthesis gas. Chem. React. Eng. Technol. 2016, 32, 504–512. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, H.Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Gao, F.; Dong, L.; Chen, Y. Influence of CO pretreatment on the activities of CuO/γ-Al2O3 catalysts in CO+O2 reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 79, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.J.; Lou, H.; Chen, M. Selective hydrogenation of furfural to tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol over Ni/CNTs and bimetallic CuNi/CNTs catalysts. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 14721–14731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoosuk, B.; Kim, J.H.; Song, C.S.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C.; Prasassarakich, P. Highly active MoS2, CoMoS2 and NiMoS2 unsupported catalysts prepared by hydrothermal synthesis for hydrodesulfurization of 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene. Catal. Today 2008, 130, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, L.; Chai, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C. Essential role of promoter Co on the MoS2 catalyst in selective hydrodesulfurization of FCC gasoline. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2018, 46, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Q.; Wang, S.C.; Xie, H.; Gao, J.; Tian, S.; Han, Y.; Tan, Y. Influence of Cu on the K-LaZrO2 Catalyst for isobutanol synthesis. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2015, 31, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.G.; Wei, C.; Guo, W.S.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Ling, L.; Li, D. Syngas conversion to C2 oxygenates over Cu/β-Mo2C catalyst: Probing into the effect of the interface between Cu and β-Mo2C on catalytic performance. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 21022–21030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).