Changes in the Operating Conditions of Distribution Gas Networks as a Function of Altitude Conditions and the Proportion of Hydrogen in Transported Natural Gas

Abstract

1. Introduction

- There is a difference between the density of the distributed medium and the density of the surrounding air;

- There is an elevation difference between the entry point and the offtake point.

2. Materials and Methods

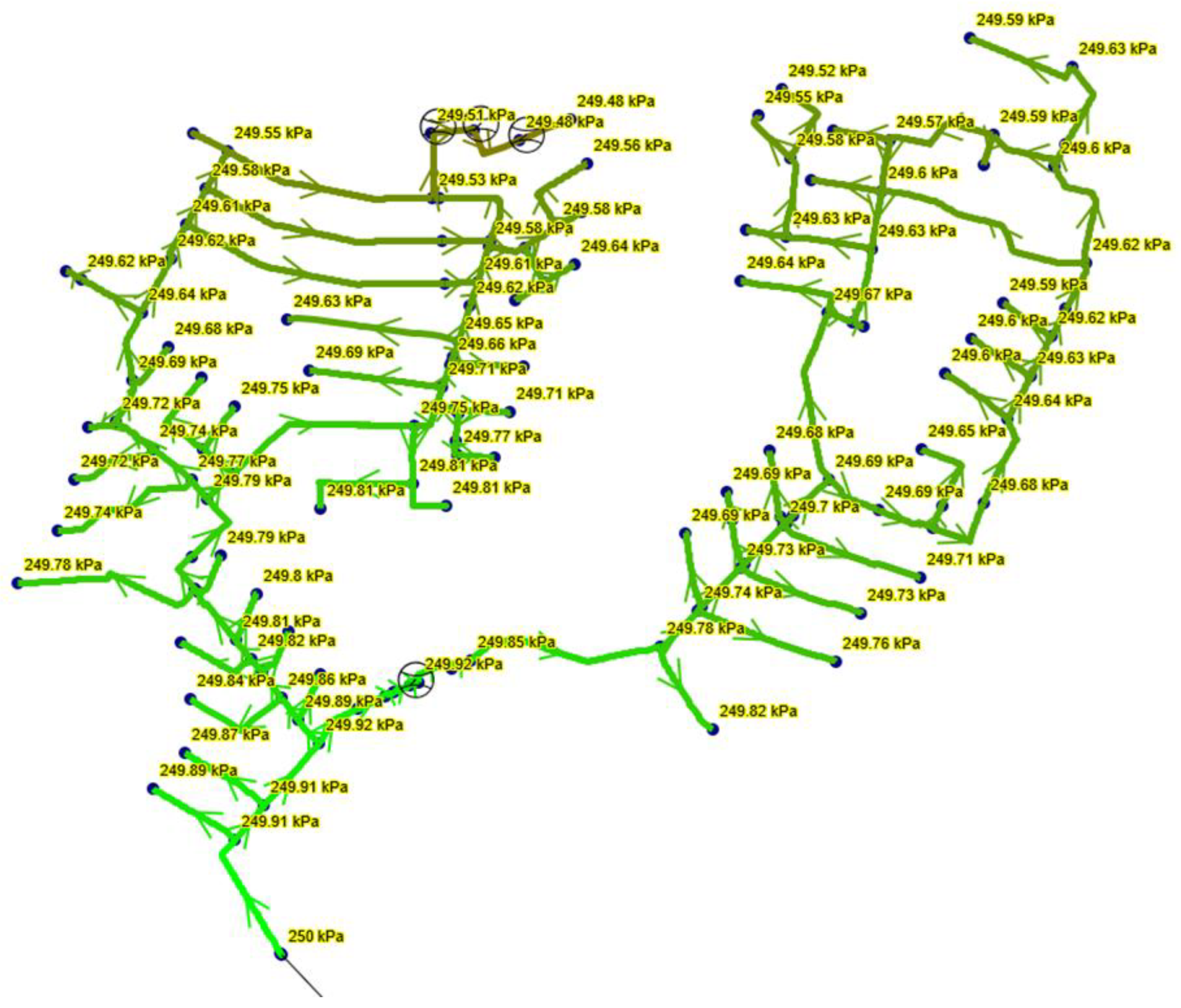

2.1. Low-Pressure Distribution Network

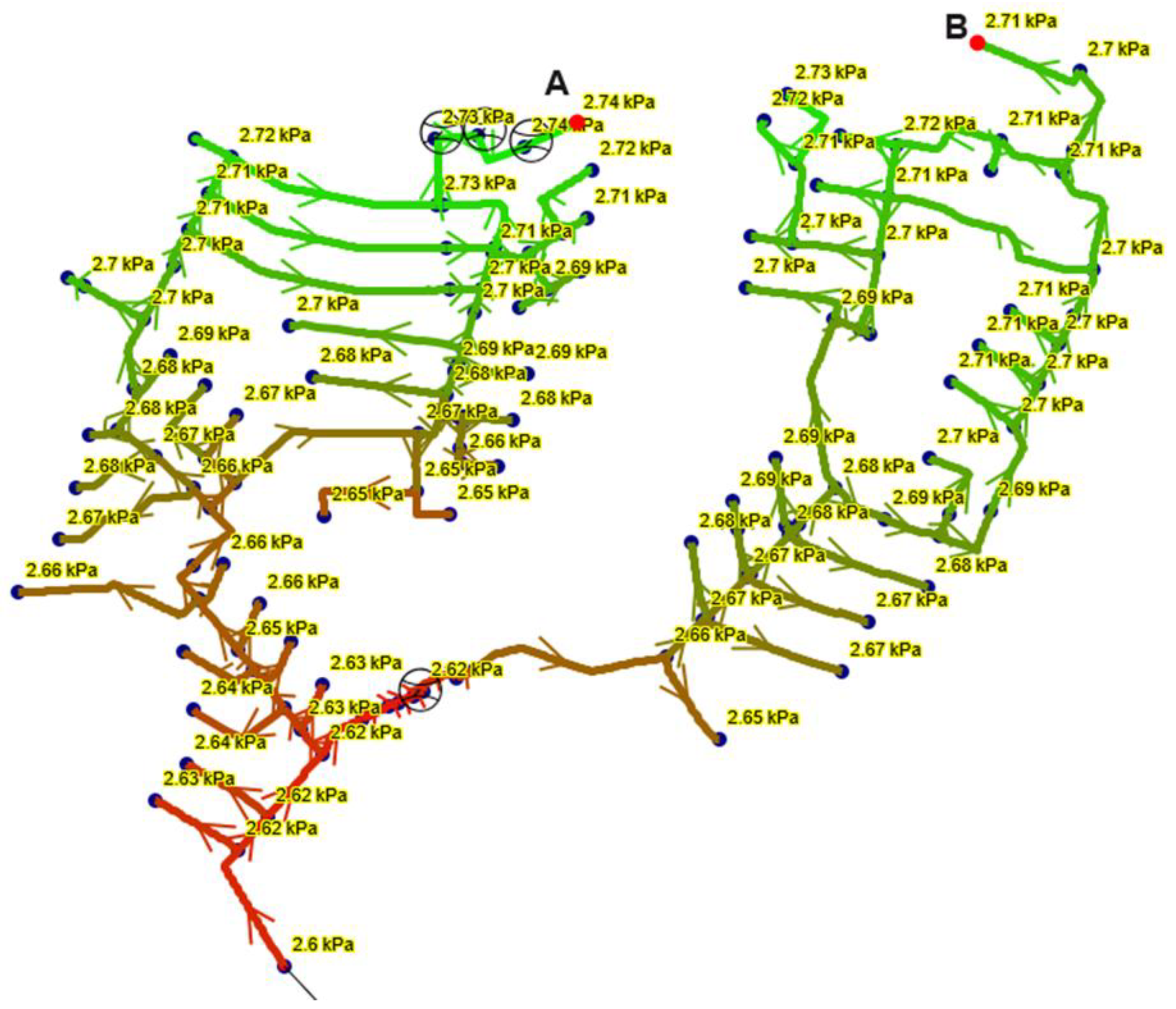

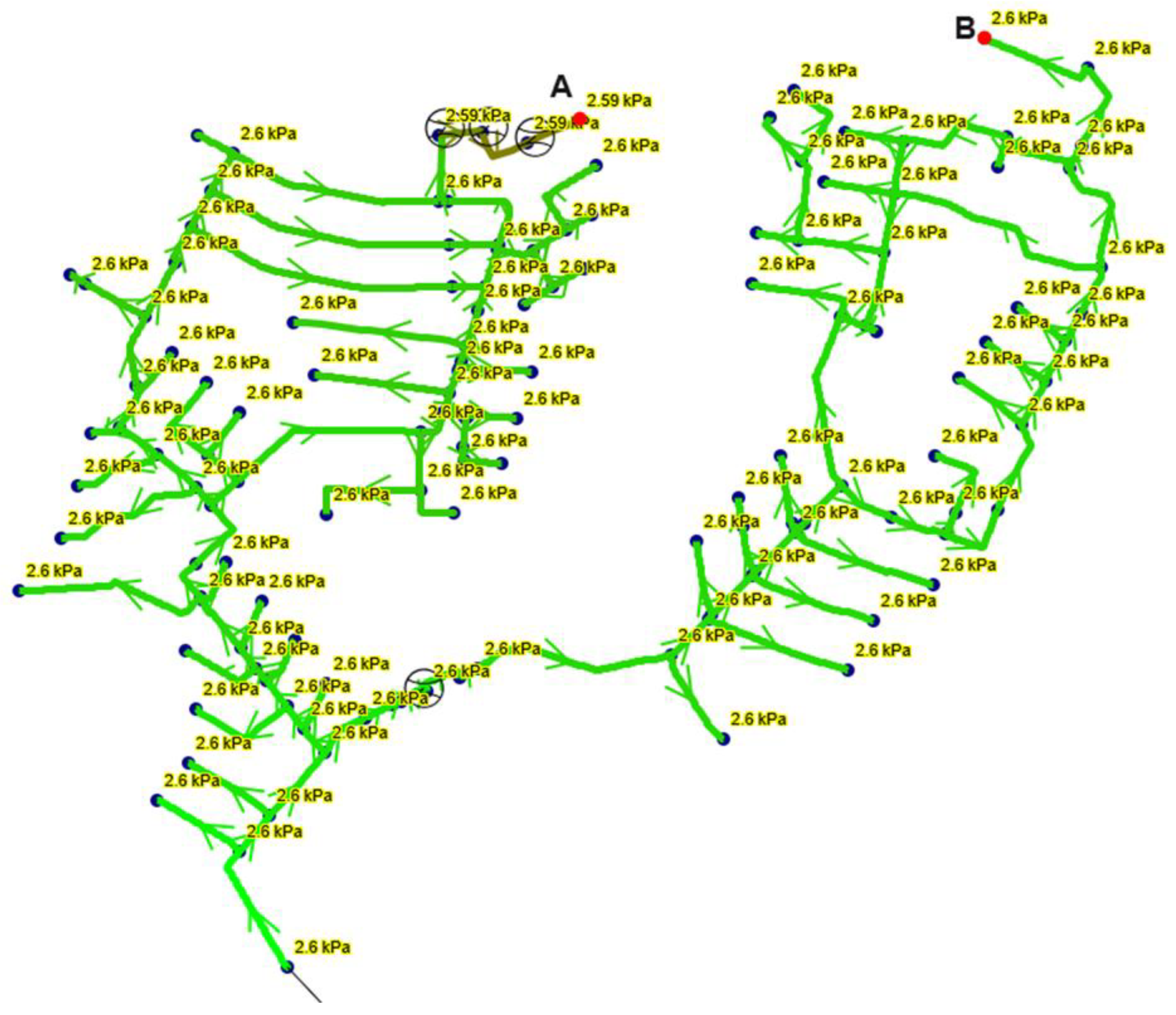

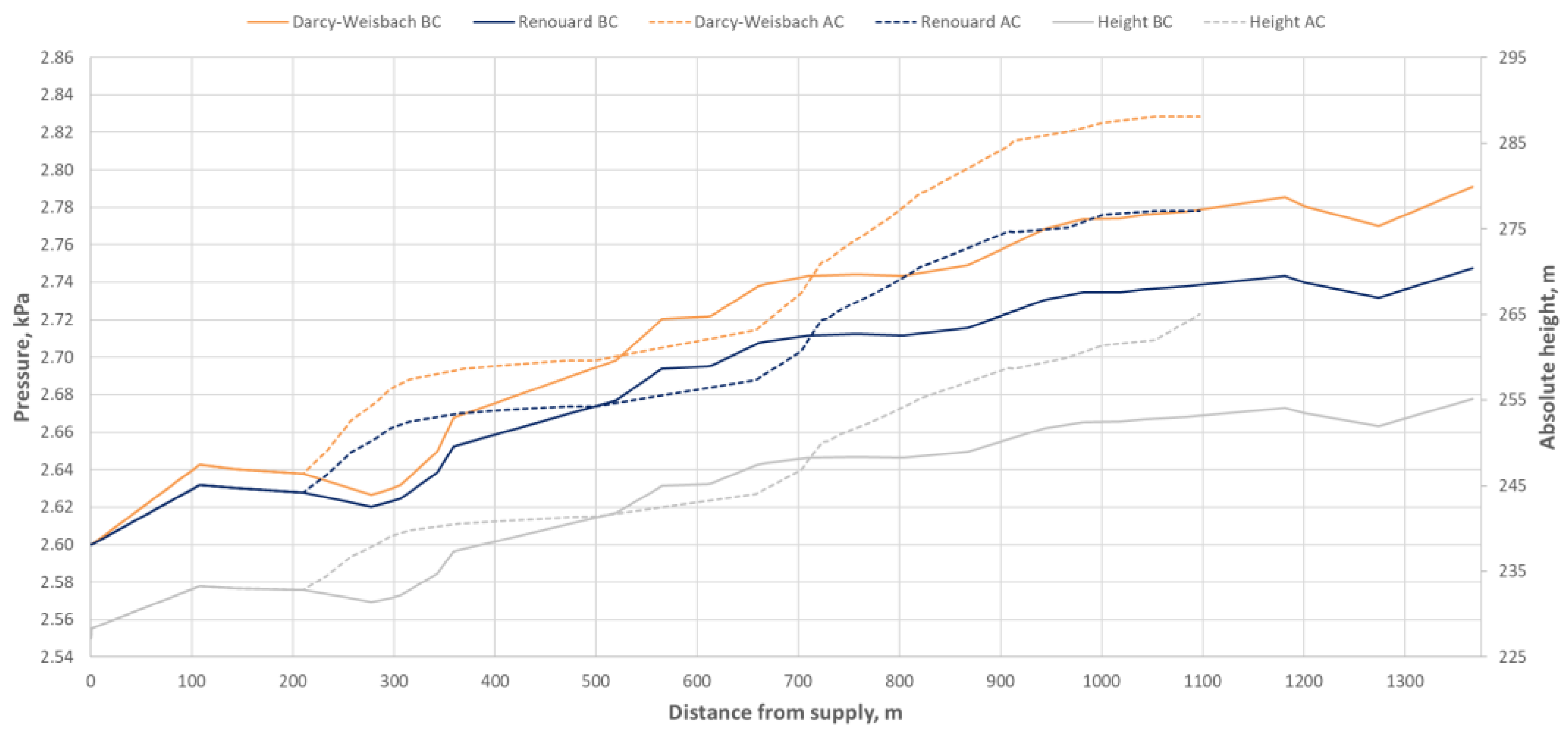

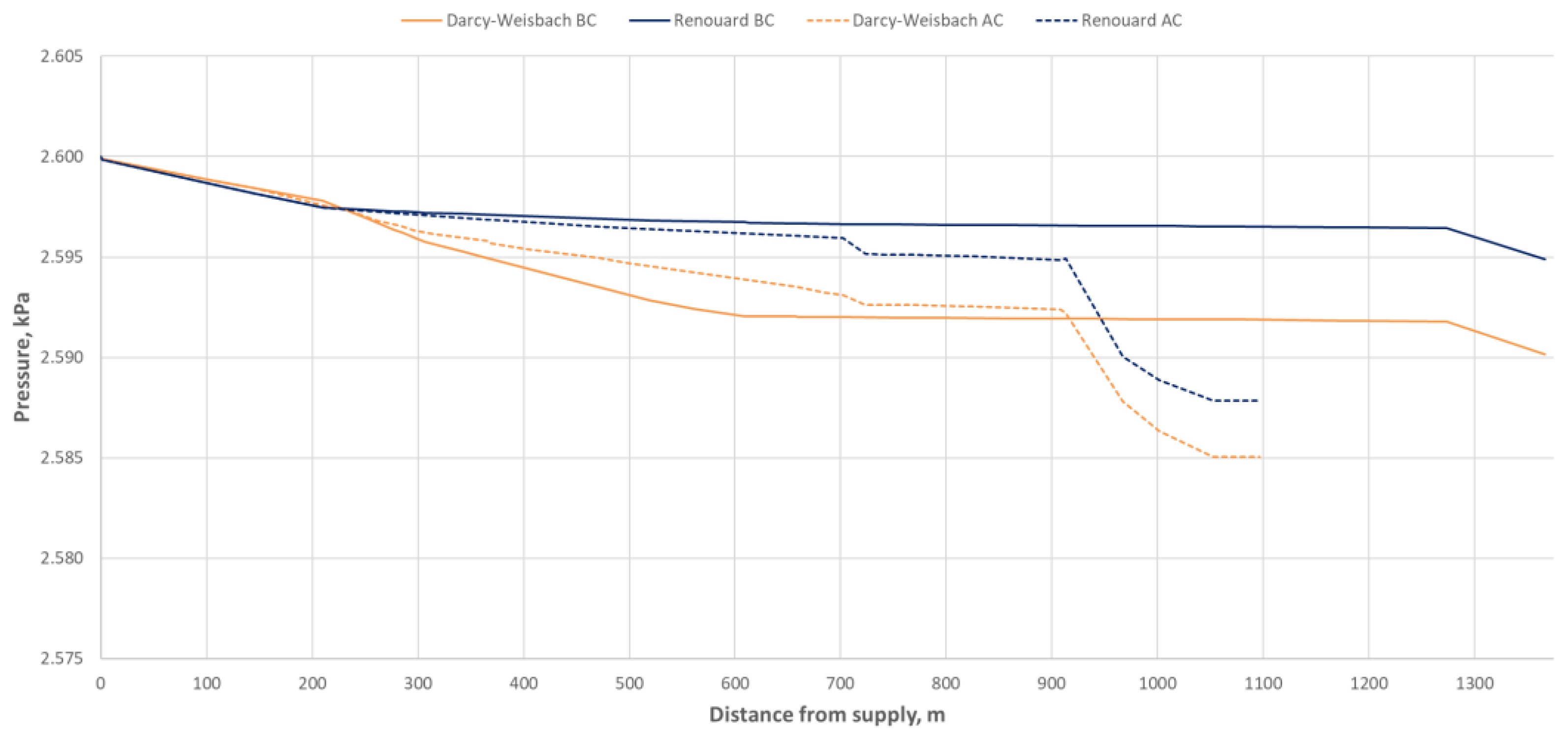

- Point A—the point with the highest elevation difference relative to the pressure source, located at 265.0 m above sea level, resulting in a height difference of 38.0 m. This point is approximately 1100 m away from the gas station along the gas flow path.

- Point B—the most distant consumption point from the pressure source, located at an elevation of 255.0 m and approximately 1400 m from the gas station.

2.2. Pressure Recovery Calculation

- turbulent conditions:

- laminar conditions:

- The Darcy–Weisbach equation:

- The Renouard equation:

2.3. Physicochemical Properties of Pure Natural Gas and Natural Gas–Hydrogen Blends

- additive parameters: density, gross/net calorific value, summation coefficient (the symbol K denotes one of the listed parameters):

- Wobbe index:

- summation coefficient (used in the calculation of the compressibility factor z):

- compressibility factor (calculated based on the summation coefficient):

- dynamic viscosity:

- kinematic viscosity:

3. Results

- calculations for actual flow distributions in the real-world network, taking elevation into account,

- calculations for actual flow distributions in a flat model of the network (neglecting elevation),

- calculations analyzing the effect of hydrogen admixture in natural gas, for both the elevation-aware network model and the flat model.

3.1. Actual Measurement Data

3.2. Simulation Calculations

3.2.1. SimNet

3.2.2. SONET/GASNET

3.2.3. STANET

3.3. Calculations Using Empirical Equations

- Point A: 2.829 kPa (Darcy-Weisbach), 2.778 kPa (Renouard);

- Point B: 2.791 kPa (Darcy-Weisbach), 2.747 kPa (Renouard).

- Point A: 2.585 kPa (Darcy-Weisbach), 2.588 kPa (Renouard);

- Point B: 2.590 kPa (Darcy-Weisbach), 2.595 kPa (Renouard).

4. Discussion

4.1. Low-Pressure Network

4.2. Medium-Pressure Network

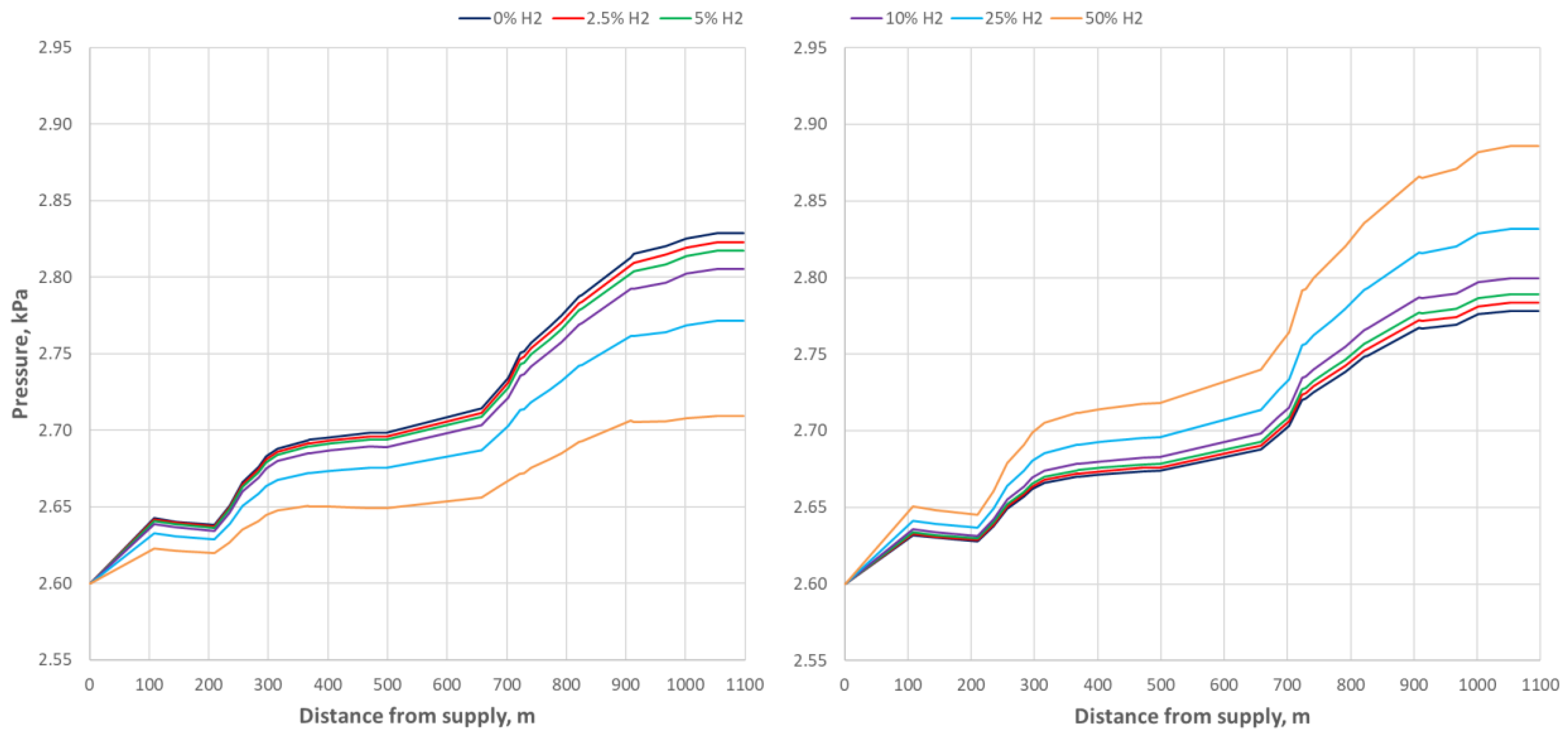

4.3. Mixture of Natural Gas with Hydrogen

5. Conclusions

- In low-pressure networks, pressure recovery does occur. Under conditions of low linear pressure losses resulting from gas flow, this can lead to increased pressure in sections of the network located farther from the supply node. A necessary condition is an appropriate network configuration, specifically an increase in node elevation with increasing distance from the supply point.

- In medium-pressure networks, pressure recovery does not occur, even when node elevations increase significantly. Moreover, comparing results from the flat model and the elevation-aware model reveals that pressure drops are noticeably greater in the elevation model. This is due to the much higher actual gas density under typical operating conditions in medium-pressure networks, where the gas becomes heavier than the surrounding air. As a result, one of the key conditions for pressure recovery is no longer met.

- Blending hydrogen with natural gas further reduces the density of the gas mixture, which enhances pressure recovery in low-pressure networks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| d | absolute gas density, – |

| D | pipe diameter, mm |

| g | gravitational acceleration, 9.81 m/s2 |

| h | geodetic elevation of the node, m |

| H | heating value (calorific value), MJ/m3 |

| K | value of a parameter for a mixture of n components, – |

| L | section length, m |

| M | molar mass, kg/kmol |

| p | pressure, bar, kPa |

| pn | pressure under normal conditions, 1.01325 bar |

| Q | volumetric gas flow rate, m3/h |

| T | gas temperature, K |

| Tn | temperature under normal conditions, 273.15 K |

| x | molar fraction, – |

| w | linear gas velocity, m/s |

| W | Wobbe index, MJ/m3 |

| Δh | elevation difference, m |

| Δp | pressure recovery, m |

| z | compressibility factor, – |

| summation coefficient | |

| λ | coefficient of linear pressure losses, – |

| ζ | local pressure losses, – |

| μ | dynamic viscosity, μPa·s |

| ν | kinematic viscosity, μm2/s |

| ϱ | absolute gas density, kg/m3 |

| Subscripts: | |

| 1 | beginning of the section |

| 2 | end of the section |

| a | proportionality coefficient |

| b | proportionality coefficient |

| i | i-th component of gas |

| kr | critical conditions |

| n | normal conditions |

| p | air |

References

- Bąkowski, K. Sieci i Instalacje Gazowe (Gas Networks and Installations); Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zajda, R. Schematy Obliczeniowe Gazociągów (Gas Pipeline Calculation Schemes); Centrum Szkolenia Gazownictwa: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Medvedeva, O.N.; Perevalov, S.D. Method of Hydraulic Calculation of Gas Distribution Networks. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Construction, Architecture and Technosphere Safety, ICCATS 2022, Sochi, Russia, 4–10 September 2022; Radionov, A.A., Ulrikh, D.V., Timofeeva, S.S., Alekhin, V.N., Gasiyarov, V.R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 308, pp. 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Wei, C.; Han, Y.; Wei, Q.; Ouyang, Z. Pipeline Network Simulation Calculation Based on Improved Newton Jacobian Iterative Method. In Proceedings of the AICS 2019, Wuhan, China, 12–13 July 2019; pp. 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajda, R. Metoda obliczeń sieci gazowych z uwzględnieniem zakładanych wielkości granicznych (The method calculation gas networks from advantage making value limitary). Nafta-Gaz 2004, 60, 242–256. [Google Scholar]

- Łaciak, M. Ocena niepewności wyników statycznej symulacji sieci gazowych (Uncertainty assessment of static gas network simulation results). Wiertnictwo Nafta Gaz 2009, 26, 661–669. [Google Scholar]

- Osiadacz, A.J. Method of steady-state simulation of gas network. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1988, 19, 2395–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczyński, A. Selection of the accumulation capacity of the gas installation supplying large consumers. Gaz Woda i Technika Sanitarna 2025, 4, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajda, R.; Tymiński, B. Instalacje i Urządzenia Gazowe. Projektowanie, Wykonywanie, Odbiór i Eksploatacja (Gas Installations and Equipment. Design, Construction, Commissioning and Operation); Centrum Szkolenia Gazownictwa PGNiG: Warszawa, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zajda, R.; Gebhardt, Z. Instalacje Gazowe Oraz Lokalne Sieci Gazów Płynnych. Projektowanie—Wykonywanie—Eksploatacja (Gas Installations and Local Liquid Gas Networks. Design—Construction—Operation); COBO-Profil: Warszawa, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Topolski, K.; Reznicek, E.P.; Erdener, B.C.; San Marchi, C.W.; Ronevich, J.A.; Fring, L.; Simmons, K.; Fernandez, O.J.G.; Hodge, B.M.; Chung, M. Hydrogen Blending into Natural Gas Pipeline Infrastructure: Review of the State of Technology; NREL/TP5400-81704; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Osiadacz, A.J.; Chaczykowski, M. Modelling and Simulation of Gas Distribution Networks in a Multienergy System Environment. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 1580–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, M.; Wu, J.; Jenkins, N.; Rees, M. Steady state analysis of gas networks with distributed injection of alternative gas. Appl. Energy 2016, 164, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhunaizi, F.A.A.; Prudhvi, M.S.; Mohamed, A. Bahrain LNG Import Terminal (BLNGIT) Project: 1st LNG Commissioning Cargo and Integration of Imported Regasified LNG (RLNG) with Domestic Khuff Gas in the Existing Distribution Network. In Proceedings of the Middle East Oil, Gas and Geosciences Show, Manama, Bahrain, 19–21 February 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piani, A.; Rigotti, S. Natural Gas Distribution Network Powered by Regasified LNG as Development of the Distribution System in Italy: Technical Scenarios and Tariff Rates. In Proceedings of the Offshore Mediterranean Conference and Exhibition, Ravenna, Italy, 27–29 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszel, M.; Szurlej, A.; Włodek, T.; Zamasz, K. Analiza znaczenia dostaw LNG dla zbilansowania popytu na gaz ziemny w Polsce. (Analysis of the importance of LNG supply for balancing the demand for natural gas: The case of Poland). Gospod. Surowcami Min. 2025, 41, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheli, L.; Guzzo, G.; Adolfo, D.; Carcasci, C. Steady-state analysis of a natural gas distribution network with hydrogen injection to absorb excess renewable electricity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 25562–25577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D.D.; Holbeach, J.; Golczynski, D.; Morrissy, S.A. The Importance of Tracking Hydrogen H2 in Complex Natural Gas Networks. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 2–5 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaciak, M. Wpływ zmian wysokości położenia na wyniki obliczeń hydraulicznych gazociągów (Effect of elevation changes on the hydraulic calculation results of gas pipelines). Wiertnictwo Nafta Gaz 2009, 26, 547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Kogut, K.; Bytnar, K. Obliczanie Sieci Gazowych. T. 1, Omówienie Parametrów Wymaganych do Obliczeń (Calculation of Gas Networks. Pt. 1, Discussion of Requirements to Calculate Parameters); AGH Uczelniane Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Dydaktyczne: Kraków, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska-Bernat, A.; Desideri, U. Opportunities of Power-to-Gas Technology in Different Energy Systems Architectures. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska-Bernat, A.; Desideri, U. Opportunities of Power-to-Gas Technology. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 4569–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PGNiG, Zasady Kwalifikacji Odbiorców do Grup Taryfowych. (Rules for the Qualification of Customers into Tariff Groups). Available online: https://pgnig.pl/dla-domu/zasady-kwalifikacji-odbiorcow-do-grup-taryfowych (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- SimNet SSGas 7, Podręcznik Użytkownika (SimNet SSGas 7. User Manual); Fluid Systems Sp. z o.o.: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- Sonet, D.E. Instrukcja Użytkownika, wersja 3.8 (Sonet DE. User Manual, Version 3.8); Sygnity S.A.: Warszawa, Poland, 2011.

- Obliczenia Sieciowe. Instrukcja Użytkownika Modułu, wersja dokumentacji 1.9 (Network Calculation. Module User Manual, Documentation version 1.9); Sygnity S.A.: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- Dobór Średnic i Symulacja Sieci Gazociągowych. Opis Programu GASNET Wersja 3 (Diameter Selection and Simulation of Gas Networks. Description of GASNET Version 3). Available online: http://www.uktn.com/gasnet_opis/gasnet_opis.html (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- PN-M-34034; Rurociągi—Zasady Obliczeń Strat Ciśnienia (Piping—Principles of Pressure Loss Calculations). PKN: Warszawa, Poland, 1976.

- Kogut, K. STANET. Nafta Gaz Biznes 2000, nr11, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kogut, K.; Bytnar, K. Obliczanie Sieci Gazowych. T. 2, Przegląd Programów Komputerowych (Calculation of Gas Networks. Pt. 2, Review of Computer Programs); AGH Uczelniane Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Dydaktyczne: Kraków, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- STANET—Obliczanie Sieci. Instrukcja Obsługi (STANET—Network Calculations. User Manual); Engineer Büro Fischer-Uhrig: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczyński, S.; Łaciak, M.; Olijnyk, A.; Szurlej, A.; Włodek, T. Thermodynamic and Technical Issues of Hydrogen and Methane-Hydrogen Mixtures Pipeline Transmission. Energies 2019, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaz-System, System Wymiany Informacji Gaz-System S.A. (Information Exchange System Gaz-System S.A.). Available online: https://swi.gaz-system.pl/swi/public/#!/gas/quality/4/point/monthly?lang=pl (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- EN ISO 12213-2; Natural Gas—Calculation of Compression Factor—Part 2: Calculation Using Molar-Composition Analysis. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Schley, P.; Nguyen, T.T.G.; Span, R.; Hielscher, A.; Kleppek, G.; van der Grinten, J.; Schmidt, R.; Sarge, S.M. Calculation of Compression Factors and Gas Law Deviation Factors Using the Modified SGERG-Equation SGERG-mod-H2; Technical Report PK 1-5-3; DVGW: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Gospodarki z Dnia 2 Lipca 2010 r. w Sprawie Szczegółowych Warunków Funkcjonowania Systemu Gazowego (The Regulation of the Minister of Economy of July 2, 2010 on Detailed Conditions for the Operation of the Gas System). Dz.U. 2010 nr 133 poz. 891 z Późniejszymi Zmianami (as Amended). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20101330891 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Gaz-System, Instrukcja Ruchu i Eksploatacji Sieci Przesyłowej. Wersja 29 (NTS Transmission Network Code. Version 29). OGP GAZ-SYSTEM S.A. Available online: https://www.gaz-system.pl/pl/dla-klientow/uslugi-w-ksp/iriesp-ksp.html (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- PN-EN-04752; Gaz Ziemny—Jakość Gazu w Sieci Przesyłowej (Natural Gas—Gas Quality in the Transmission Network). PKN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011.

- PN-EN-04753; Gaz Ziemny—Jakość Gazu Dostarczanego Odbiorcom z Sieci Dystrybucyjnej (Natural Gas—Quality of Gas Supplied to Customers from the Distribution Network). PKN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011.

- Wojtowicz, R. Zagadnienia wymienności paliw gazowych, wymagania prawne odnośnie jakości gazów rozprowadzanych w Polsce oraz możliwe kierunki dywersyfikacji (Interchangeability of gaseous fuels, the legal requirements for the quality of gases distributed in Poland and possible diversification directions). Nafta-Gaz 2012, 68, 359–367. [Google Scholar]

| Tariff Group | Contracted Power b 1 [kWh/h] | Annual Contract Volume a [m3/year] |

|---|---|---|

| W-1 (1.1, 1.2, 1.12T) | b ≤ 110 | a ≤ 300 |

| W-2 (2.1, 2.2, 2.12T) | b ≤ 110 | 300 < a ≤ 1 200 |

| W-3 (3.6, 3.9, 3.12T) | b ≤ 110 | 1 200 < a ≤ 8 000 |

| Elements | Input Gas | Hydrogen Content in the Exit Gas | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 5.0% | 10.0% | 25.0% | 50.0% | ||||

| Component | methane | % mol. | 97.8780 | 95.4311 | 92.9841 | 88.0902 | 73.4085 | 48.9390 |

| ethane | % mol. | 0.9100 | 0.8873 | 0.8645 | 0.8190 | 0.6825 | 0.4550 | |

| propane | % mol. | 0.1670 | 0.1628 | 0.1587 | 0.1530 | 0.1253 | 0.0835 | |

| i-butane | % mol. | 0.0430 | 0.0419 | 0.0409 | 0.0387 | 0.0323 | 0.0215 | |

| n-butane | % mol. | 0.0280 | 0.0273 | 0.0266 | 0.0252 | 0.0210 | 0.0140 | |

| i-pentane | % mol. | 0.0180 | 0.0176 | 0.0171 | 0.0162 | 0.0135 | 0.0090 | |

| n-pentane | % mol. | 0.0060 | 0.0059 | 0.0057 | 0.0054 | 0.0045 | 0.0030 | |

| heavier hydrocarbons | % mol. | 0.0170 | 0.0166 | 0.0162 | 0.0153 | 0.0128 | 0.0085 | |

| nitrogen | % mol. | 0.6800 | 0.6630 | 0.6460 | 0.6120 | 0.5100 | 0.3400 | |

| carbon dioxide | % mol. | 0.2530 | 0.2467 | 0.2404 | 0.2277 | 0.1898 | 0.1265 | |

| hydrogen | % mol. | 0.0000 | 2.5000 | 5.0000 | 10.0000 | 25.0000 | 50.0000 | |

| Parameters | absolute density | kg/m3 | 0.7350 | 0.7188 | 0.7027 | 0.6704 | 0.5737 | 0.4124 |

| relative density | — | 0.5684 | 0.5559 | 0.5435 | 0.5185 | 0.4437 | 0.3189 | |

| gross caloric value | kWh/m3 | 11.102 | 10.913 | 10.724 | 10.345 | 9.211 | 7.321 | |

| MJ/m3 | 39.97 | 39.29 | 38.605 | 37.244 | 33.160 | 26.356 | ||

| net caloric value | kWh/m3 | 10.009 | 9.834 | 9.658 | 9.308 | 8.256 | 6.502 | |

| MJ/m3 | 36.03 | 35.402 | 34.77 | 33.508 | 29.722 | 23.407 | ||

| higher Wobbe index | kWh/m3 | 14.73 | 14.64 | 14.55 | 14.367 | 13.829 | 12.963 | |

| MJ/m3 | 53.01 | 52.69 | 52.37 | 51.722 | 49.784 | 46.666 | ||

| lower Wobbe index | kWh/m3 | 13.28 | 13.19 | 13.10 | 12.926 | 12.394 | 11.513 | |

| MJ/m3 | 47.79 | 47.48 | 47.17 | 46.534 | 44.618 | 41.447 | ||

| dynamic viscosity | μPa·s | 10.523 | 10.500 | 10.476 | 10.426 | 10.286 | 9.874 | |

| kinematic viscosity | μm2/s | 14.318 | 14.607 | 14.909 | 15.551 | 17.878 | 23.944 | |

| summation coefficient | – | 0.0497 | 0.0486 | 0.0474 | 0.0452 | 0.0383 | 0.0269 | |

| compressibility factor | – | 0.9975 | 0.9976 | 0.9977 | 0.9980 | 0.9985 | 0.9993 | |

| Measurement Point | Supply Pressure [kPa] | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS-44 | Measured pressure [kPa] | 2.97 ± 0.12 | 2.99 ± 0.12 | 3.00 ± 0.12 |

| NS-17C | 3.18 ± 0.10 | 3.21 ± 0.12 | 3.20 ± 0.12 | |

| NS-10B | 2.84 ± 0.17 | 2.92 ± 0.13 | 2.89 ± 0.16 |

| Calculation | Supply Node | Flat Model | Elevation Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | A | B | A | B | |

| Darcy-Weisbach | 2.600 | 2.585 | 2.590 | 2.829 | 2.791 |

| Renouard | 2.600 | 2.588 | 2.595 | 2.778 | 2.747 |

| STANET | 2.600 | 2.589 | 2.595 | 2.788 | 2.735 |

| SimNet | 2.600 | 2.590 | 2.600 | 2.740 | 2.710 |

| SONET | 2.600 | 2.587 | 2.594 | 2.740 | 2.720 |

| Measurement | 2.600 | — | — | 2.788 | — |

| Calculation | Supply Node | Flat Model | Elevation Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | A | B | A | B | |

| STANET | 250.000 | 249.997 | 249.999 | 249.538 | 249.660 |

| SimNet | 250.000 | 249.991 | 249.996 | 249.478 | 249.589 |

| Darcy-Weisbach | 250.000 | 249.989 | 249.993 | 249.559 | 249.619 |

| Renouard | 250.000 | 249.970 | 249.987 | 249.523 | 249.574 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kogut, K.; Narloch, P.; Kapusta, K.; Zięba, E. Changes in the Operating Conditions of Distribution Gas Networks as a Function of Altitude Conditions and the Proportion of Hydrogen in Transported Natural Gas. Fuels 2025, 6, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040082

Kogut K, Narloch P, Kapusta K, Zięba E. Changes in the Operating Conditions of Distribution Gas Networks as a Function of Altitude Conditions and the Proportion of Hydrogen in Transported Natural Gas. Fuels. 2025; 6(4):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040082

Chicago/Turabian StyleKogut, Krzysztof, Piotr Narloch, Katarzyna Kapusta, and Ewa Zięba. 2025. "Changes in the Operating Conditions of Distribution Gas Networks as a Function of Altitude Conditions and the Proportion of Hydrogen in Transported Natural Gas" Fuels 6, no. 4: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040082

APA StyleKogut, K., Narloch, P., Kapusta, K., & Zięba, E. (2025). Changes in the Operating Conditions of Distribution Gas Networks as a Function of Altitude Conditions and the Proportion of Hydrogen in Transported Natural Gas. Fuels, 6(4), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040082