Abstract

Background: Advancements in low-cost additive manufacturing and artificial intelligence have enabled new avenues for developing accessible myoelectric prostheses. However, achieving reliable real-time control and ensuring mechanical durability remain significant challenges, particularly for affordable systems designed for resource-constrained settings. Objective: This study aimed to design and validate a low-cost, 3D-printed prosthetic arm that integrates single-channel electromyography (EMG) sensing with machine learning for real-time gesture classification. The device incorporates an anatomically inspired structure with 14 passive mechanical degrees of freedom (DOF) and 5 actively actuated tendon-driven DOF. The objective was to evaluate the system’s ability to recognize open, close, and power-grip gestures and to assess its functional grasping performance. Method: A Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based feature extraction pipeline was implemented on single-channel EMG data collected from able-bodied participants. A Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier was trained on 5000 EMG samples to distinguish three gesture classes and benchmarked against alternative models. Mechanical performance was assessed through power-grip evaluation, while material feasibility was examined using PLA-based 3D-printed components. No amputee trials or long-term durability tests were conducted in this phase. Results: The SVM classifier achieved 92.7% accuracy, outperforming K-Nearest Neighbors and Artificial Neural Networks. The prosthetic hand demonstrated a 96.4% power-grip success rate, confirming stable grasping performance despite its simplified tendon-driven actuation. Limitations include the reliance on single-channel EMG, testing restricted to able-bodied subjects, and the absence of dynamic loading or long-term mechanical reliability assessments, which collectively limit clinical generalizability. Overall, the findings confirm the technical feasibility of integrating low-cost EMG sensing, machine learning, and 3D printing for real-time prosthetic control while emphasizing the need for expanded biomechanical testing and amputee-specific validation prior to clinical application.

1. Introduction

Electromyography (EMG) is a biological signal generated by muscle activity, used to study and record electrical impulses that provide insights into muscle contraction patterns [1]. The integration of EMG sensors with Artificial Intelligence (AI) presents a promising advancement in prosthetics, aiming to improve the functionality and usability of prosthetic limbs. This combination can enhance the intuitiveness and responsiveness of prosthetic arm movements, significantly improving the quality of life for amputees. The human hand is a highly versatile and intricate tool. Its loss necessitates the development of effective prosthetic replacements. Various initiatives have been undertaken to assist individuals with limb loss [2,3]. A thorough review of the existing literature helps establish the foundation for the seamless integration of EMG sensors and AI-driven control mechanisms.

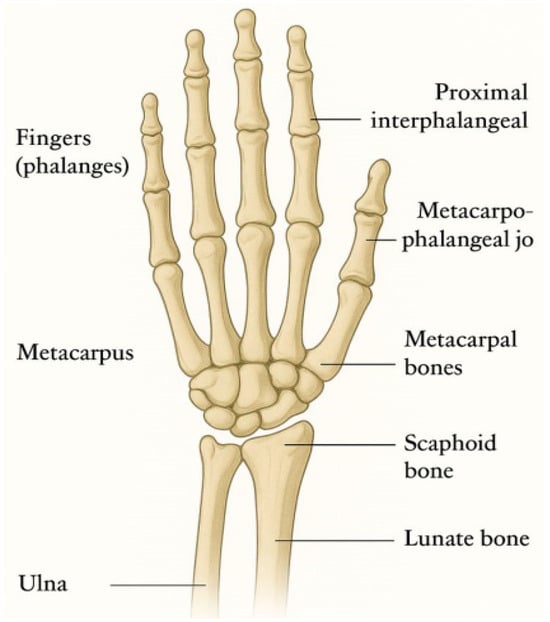

The advent of 3D printing technology has further improved the field of prosthetics by enabling the design and fabrication of customized prosthetic limbs tailored to individual anatomical and functional requirements [4,5]. This approach reduces production costs and accelerates manufacturing, making prosthetic devices more accessible. For instance, organizations like Limbitless Solutions have leveraged 3D printing to create affordable, personalized bionic arms for children with limb differences, significantly improving their quality of life [6]. Combining EMG signal analysis with 3D printing holds immense potential in developing prosthetic hands capable of performing intricate tasks such as grasping objects, typing, and handling utensils. By analyzing EMG signals generated by muscle activity, these prosthetic devices can interpret the user’s intentions and translate them into precise movements. Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this integration, showcasing prosthetic hands that utilize EMG signals and neural networks for real-time control, thereby enhancing dexterity and responsiveness. Research into the human hand’s anatomical structure and functional complexity informs the development of advanced prosthetics [7]. The hand’s dexterity is attributed to its high degree of freedom (DoF), with 27 bones, 29 joints, and intricate muscular and nervous systems enabling a wide range of movements [8]. Figure 1 shows a typical human hand and its 27 individual bones.

Figure 1.

The human hand and its 27 individual bones.

The degree of freedom in prosthetic arms determines their flexibility and functional capabilities, influencing the user’s ability to perform everyday tasks [9]. Understanding these intricacies aids in designing prosthetics that closely mimic natural hand movements [10]. Historically, prosthetics have evolved significantly, from rudimentary wooden and leather limbs in ancient Egypt (3000 BCE) to the functional designs developed during the Middle Ages and the 18th century. Advances in metallurgy and medical knowledge led to more sophisticated artificial limbs, improving amputees’ mobility and quality of life. The 19th century saw innovations such as articulated limbs, allowing for more dynamic movement. The 20th century introduced lightweight materials like aluminum alloys and microprocessor-controlled prosthetics, enhancing limb replacement technology [11]. The 21st century has brought unprecedented advancements, including myoelectric prosthetics that use EMG signals to enable intuitive control of prosthetic limbs [12]. Neural interfaces and brain–computer interaction have further enhanced control mechanisms, offering users the ability to operate prosthetic devices through brain signals [13]. Additionally, 3D printing has enabled the production of cost-effective, customized prosthetics, improving accessibility and user experience [14].

Despite meaningful progress in myoelectric prosthetics, current systems still face technical limitations relating to actuator scalability, sensor robustness, control latency, and material durability. Commercial hands such as Ottobock and Bebionic typically employ multi-actuator architectures with high-torque brushless motors, which increase weight, thermal load, and cost [15].

Furthermore, surface EMG remains susceptible to motion artefacts, electrode drift, and inter-day variability, often requiring multi-channel arrays and adaptive filtering to maintain control stability. Wearable photonic wristbands and textile-based sensors improve physiological monitoring but are rarely optimized for low-latency motor control [16]. The technical gap motivating this study is the need for low-cost, lightweight, and computationally efficient prosthetic systems that leverage minimal sensor inputs yet still support responsive, reliable motion. This work contributes a single-channel EMG + SVM architecture, an optimized tendon-driven mechanism, and a fully 3D-printed structure targeting affordability and reproducibility.

2. Methodology

The development of an advanced prosthetic arm system necessitates the integration of expertise from multiple disciplines, including bioengineering, signal processing, robotics, and user-centered design. This methodology adopts a holistic approach to designing a prosthetic limb capable of adaptive and intuitive control. By incorporating customizable electromyography (EMG) sensor systems and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithms, the prosthetic arm learns from individual users’ muscle signals, enabling personalized control. Advanced manufacturing techniques, such as 3D printing, play a pivotal role in fabricating the prosthetic arm, ensuring structural integrity while optimizing weight and design flexibility. Furthermore, extensive user testing and feedback mechanisms are incorporated into the development cycle to enhance usability and acceptance among end-users. This structured approach is a preliminary engineering validation as it was tested on able-bodied participants, rather than amputees, whose muscle physiology, residual muscle mass, and signal patterns differ substantially. Furthermore, descriptive statistics were computed for all performance variables. Future iterations will incorporate inferential statistical analysis, including ANOVA for EMG feature variability, confidence intervals for classification accuracy, and repeated-measures statistical tests to quantify intra-subject and inter-subject variation.

2.1. Material Selection and Component Design

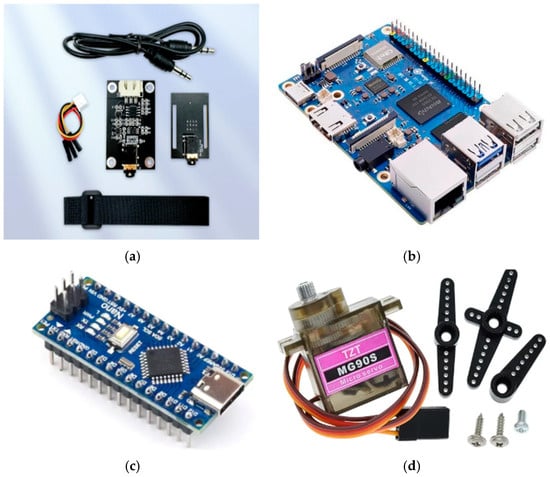

Material selection is crucial for optimizing the performance, durability, and cost-effectiveness of the prosthetic arm while ensuring user comfort and safety. The EMG sensor (OEMG, Shenzhen, China), a dry electrode myoelectric device, detects electrical signals from muscle contractions without conductive gels, providing a non-invasive and user-friendly interface. The Arduino Nano (NANO V3.0, Chongqing, China), a compact microcontroller, processes EMG signals and converts them into commands for the MG90s micro servo motors (Eastern Aviation Model, Lijang, China), which actuate the prosthetic arm’s joints and fingers for dexterous motion. Lightweight and durable materials are prioritized. Polylactic acid (PLA) filament (BING3D, Zhangmutou, China) is used for structural components due to its biodegradability, ease of printing, and good surface finish [17]. Although PLA is not the strongest polymer available for prosthetic components, it offers an optimal balance between printability, dimensional stability, and stiffness, which is critical for tendon-driven actuation. Its low warping tendency ensures consistent channel alignment for tendon routing. In addition, PLA’s elastic modulus (∼3.5 GPa) supports stable force transmission compared with more ductile polymers. These properties, combined with the device’s non-load-bearing application, justify its selection for this early-stage prototype. Fishing line and shock cords are integrated into the tendon-driven actuation system for effective force transmission. A lithium-ion battery supplies power, balancing weight, energy density, and cycle life. Figure 2 shows some key component selection, while Table 1 outlines the reliability, affordability, and ease of maintenance of all materials selected.

Figure 2.

Selection of some key components: (a) EMG Sensor (Dry Electrode); (b) Orange Pi (ORANGEPI, Shenzhen, China); (c) Arduino Nano; (d) MG90s Micro Servo.

Table 1.

Material Selection.

2.2. Mechanical Design and Fabrication

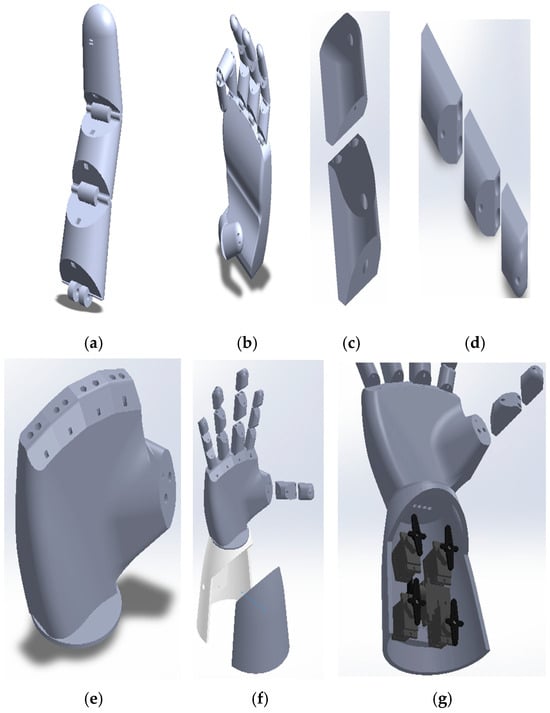

The mechanical design of the prosthetic arm focuses on biomimetic principles, ensuring ergonomic efficiency and user comfort. An artificial tendon mechanism, inspired by biological muscle function, is employed for finger articulation. This design is validated through extensive literature reviews of existing prosthetic models such as the Shadow Hand, InMoov, and Bebionic3. The fingers are designed with three printed segments, incorporating paracords as tendons that traverse internal channels, allowing for smooth and coordinated flexion upon tensioning. The thumb design, while simplified for mechanical efficiency, retains essential grasping functionality by enabling controlled movement along a single axis. The palm structure provides anchorage for tendons and servos, ensuring stable and responsive motion transmission. The forearm segment houses critical electronic components, including servo motors, the power supply, and control circuitry. To accommodate these components while maintaining a sleek design, the forearm is divided into modular segments, facilitating ease of assembly and maintenance. SolidWorks CAD 2021 software is extensively used in the design process, enabling precise 3D modeling, simulation, and optimization of the prosthetic structure. Iterative prototyping through 3D printing allows for rapid testing and refinement, ensuring the final design meets functional and ergonomic requirements. The drive system operates on a servo-driven tendon mechanism, enabling controlled flexion and extension of the fingers. This design prioritizes efficiency, affordability, and user adaptability, ultimately contributing to the development of a high-performance prosthetic arm that enhances the daily functionality of individuals with limb loss. The evolution of the prosthetic hand design from early concepts to final assembly is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Prosthetic Hand Design—From Early Concepts to Final Assembly: (a) Early Index Design; (b) Early Hand Assembly; (c) Final Index Design; (d) Final Thumb Design; (e) Final Right Palm Design; (f) Forearm Assembly; (g) Forearm Exploded View.

To ensure adequate force transfer, finger phalanges were dimensioned based on tendon tension requirements derived from servo torque limits. Finite-element simulations were performed during CAD design to verify stress concentrations at the tendon anchor points. Critical features such as joint clearances, tendon-routing curvature, and servo bay tolerances were iteratively refined to minimize mechanical backlash.

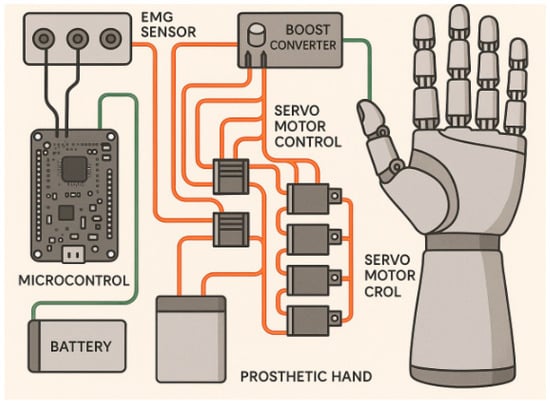

Recent orthopedic research has demonstrated the use of a variety of 3D-printing methods such as selective laser sintering (SLS), stereolithography (SLA), and fused deposition modeling (FDM) for the fabrication of custom implants, splints, and rehabilitation devices. SLS and SLA often provide superior surface resolution and mechanical uniformity, making them suitable for high-load orthopedic components. However, these techniques typically involve higher costs, limited material diversity, and more complex post-processing requirements [18]. Figure 4 is a schematic diagram showing how the EMG sensor, Arduino Nano microcontroller, MG90s servo motors, Li-ion battery, and DC-DC converter are interconnected and physically positioned within the prosthetic arm. The EMG sensor feeds muscle-activation signals to the microcontroller, which processes the data and sends control signals to the servo motors embedded in the forearm compartment. Power from the battery is regulated through a boost converter to supply stable voltage to both control electronics and actuators.

Figure 4.

Physical Placement and Wiring Layout of the Prosthetic Arm Components.

2.2.1. Mechanical Calculations

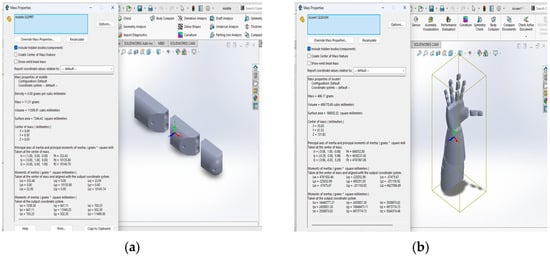

Figure 5 shows the design mass properties of the fingers which were used in the design calculations.

Figure 5.

Mass Design Properties for (a) the middle finger and (b) the forearm.

- Force in Fingers

The torque, force, and moment of inertia for the middle finger, actuated by an MG90s servo motor, are calculated as follows:

Finger Specifications:

- Mass of the finger, m = 0.012 kg

- Acceleration due to gravity, g = 9.81 m/s2

- The radius of the servo horn, r = 0.02 m

- Distance of the fishing line, L = 0.25 m

- Length of the finger, l = 0.083 m

Servo Motor Specifications:

- Operating Voltage: 4.8 V to 6 V (Typically 5 V)

- Stall Torque at 4.8 V: 1.8 kg/cm (0.18 Nm)

- Max Stall Torque at 6 V: 2.2 kg/cm (0.22 Nm)

Calculations:

- Weight of the finger: W = m × g = 0.012 kg × 9.81 m/s2 = 0.118 N

- Torque (T) per finger: T = F × r = 0.118 N × 0.02 m = 0.00236 Nm

- Moment of Inertia (I): I = m × l2 = 0.012 × (0.083 m)2 = 1.03 × 10−4 kg·m2

- Finger Actuation Speed

The MG90s servo has an operating speed of 0.1 s/60°. A full wrist rotation from a palm up to a palm down position (180°) therefore takes .

The tendon travel 2 cm to move the finger the finger from fully extended to fully flexed. Using the arc length formula:

where r = 7 mm and Arc Length = 2 cm, the required servo rotation is approximately 160°. The time to fully open/close a finger is .

2.2.2. Manufacturing & Assembly

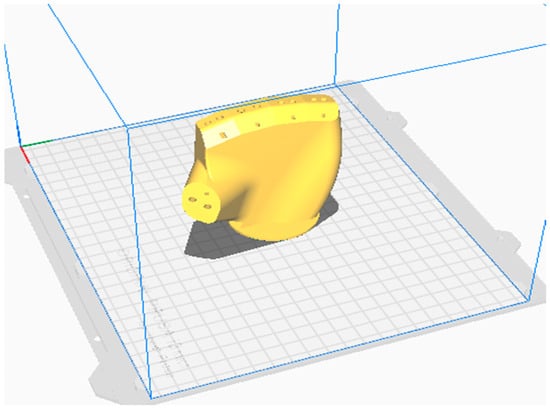

The choice of the Prusa MK3 3D printer for manufacturing the mechanical components proved to be instrumental in achieving the desired precision and quality. Its capability to generate support material effectively reinforced horizontal planes during printing, although this necessitated careful removal to prevent any damage to the components. Experimentation with various parameters such as print speed, layer resolution, and extrusion temperature within the range of 210–215 degrees Celsius ensured optimal printing conditions, resulting in high-quality output. The Design slicing and the final 3D prosthesis arm are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7 respectively. During the assembly process, challenges emerged primarily due to the support material obstructing areas intended for the passage of fishing lines and paracords. To overcome this hurdle, a strategic solution was employed. The PLA components underwent immersion in hot water to dissolve and clear the support material effectively, thereby facilitating smooth threading of the fishing lines and paracords through the designated pathways. Despite encountering these obstacles, meticulous attention to detail and innovative problem-solving techniques were pivotal in ensuring the successful assembly of the prosthetic device.

Figure 6.

3D Design Slicing on Cura.

Figure 7.

The Assembled 3D Printed Prosthesis Arm.

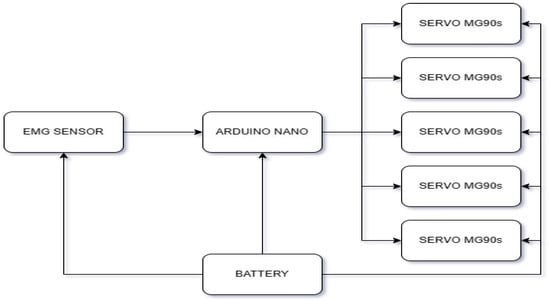

2.3. Signal Processing and Control Mechanism

Accurate real-time signal processing is fundamental for seamless prosthetic control. The EMG sensor detects and classifies muscle signals, ensuring precision and reliability. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithms analyze frequency components, identifying muscle activation patterns. These processed signals are mapped to specific motor commands, enabling intuitive prosthetic movements. The Arduino Nano handles real-time processing, efficiently translating EMG signals into mechanical motion. The signal processing workflow includes amplification, filtering, transformation, and analog-to-digital conversion to ensure accuracy. The microcontroller then interprets the processed signal and generates control commands for the servo motors, enabling responsive prosthetic actuation. The system block diagram is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

System Block Diagram.

The Arduino Nano was selected due to its low-power consumption and straightforward analog-to-digital interface; however, it imposes limitations related to memory capacity (32 kB flash) and sampling throughput. Alternatives such as STM32 microcontrollers or the Raspberry Pi Pico offer higher ADC resolution (12–16 bit), hardware DSP units, and significantly higher clock speeds which would enable more advanced filtering (e.g., wavelets, adaptive filters). These trade-offs will be considered in future iterations requiring multi-channel EMG processing or proportional-control frameworks.

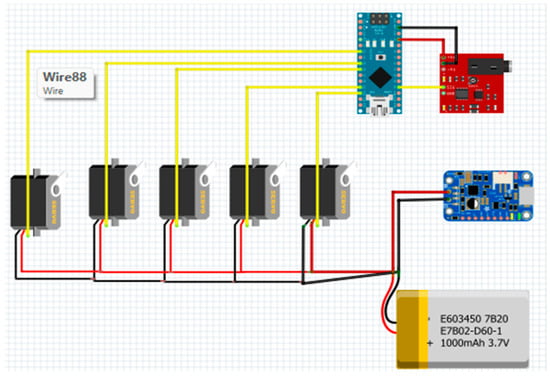

The actuation system employs standard servo motors capable of ±90-degree rotation. The precision of angular displacement influences control accuracy. Cost-effective servos balance affordability and functionality, while the Arduino Nano efficiently handles signal processing despite its lower computational power. The system prioritizes portability, relying on rechargeable Lithium Polymer (LiPo) batteries due to their high energy density. The Power Circuit Schematics is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Power Circuit Schematics.

Electromyography Sensing and Signal Processing Workflow

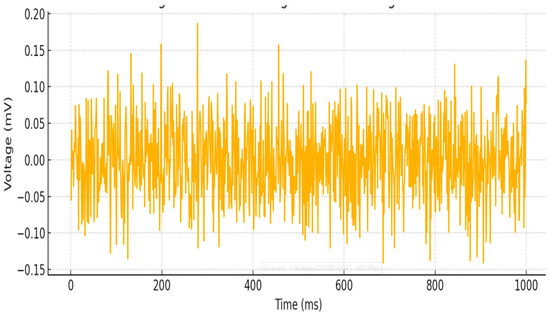

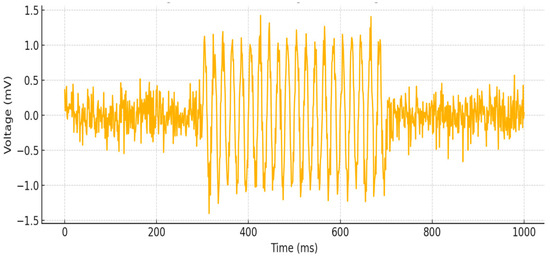

A single-channel EMG sensor board is employed to detect and quantify muscle activity. The compact printed circuit board (PCB) is equipped with three surface electrodes affixed to the residual muscles of the user. The EMG sensor seamlessly interfaces with the Arduino Nano, streamlining the integration process. Upon muscle activation, the internal amplification system within the sensor board enhances the detected electrical signals The EMG signals are presented in Figure 10 and Figure 11. These signals are then fed into the microcontroller’s analog-to-digital converter for preprocessing and precise analysis.

Figure 10.

Non-Flexing Gesture (Raw EMG Signals).

Figure 11.

Flexing Gesture (Raw EMG Signals).

The EMG processing and servo control mechanism follows a structured workflow:

- Signal Acquisition: Analog signals are captured by the EMG sensor, reflecting muscle activity from the user’s arm.

- Preprocessing: The acquired analog signals undergo sampling and storage, preparing them for subsequent analysis.

- Frequency Analysis: The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was selected as the primary analysis tool because it provides a computationally efficient method for identifying dominant frequency components associated with muscle activation, which is suitable for real-time implementation on low-power microcontrollers such as the Arduino Nano. While more advanced time–frequency methods such as wavelet transforms, Hilbert–Huang transforms, or short-time Fourier transforms can offer richer temporal resolution, they typically require greater computational resources and memory capacity.

- Fist Movement Detection: Changes in muscle activity are detected by comparing the current dominant frequency with previously recorded values. Thresholds are applied to determine whether the user is opening or closing their fist.

- Windowing and Mode Calculation: A rolling window of fist movement states is maintained to ensure robustness in detection. The most frequently occurring state (mode) within the window is used to determine the current fist position, mitigating signal fluctuations and improving accuracy.

- Servo Control: Based on the detected fist position, the microcontroller generates control signals to adjust servo motor positions, enabling real-time prosthetic actuation.

- Delay Control: Controlled delays regulate the sampling rate and processing frequency, ensuring smooth and responsive operation of the system.

2.4. Machine Learning Pipeline for Gesture Recognition

The machine-learning workflow consisted of preprocessing, feature extraction, SVM training, and cross-validation. Hyperparameters were optimized using a grid search over C and γ values and evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation. All mechanical, EMG, and classification performance metrics were obtained from internal experimental trials conducted on ten able-bodied participants.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Power Grip Performance and Grasp Effectiveness

The power grip was chosen as the primary grasping pattern for the prosthetic hand due to its fundamental importance in daily activities. Unlike more complex multi-finger grips, the power grip allows the user to securely grasp and manipulate a wide range of objects, making it highly practical for prosthetic applications. A series of grasp force tests were conducted to measure the effectiveness of the power grip in holding various objects. The force required to hold each object without slippage was measured using a dynamometer. The results are summarized in Table 2. The results indicate that the prosthetic hand can generate sufficient grip force to hold objects up to 600 g, with an overall grasp success rate of 96.4% across different object categories. This confirms the feasibility of the power grip in practical use cases. Figure 12 shows the prosthetic hand performing a stable power grip on a hot glue gun.

Table 2.

Grip Force Test for Various Objects.

Figure 12.

Achievable Power Grip.

3.2. Component Strength and Material Durability Assessment

The durability of the 3D printed prosthetic arm was assessed by testing its mechanical strength under various loading conditions. The components were fabricated using Polylactic Acid (PLA) plastic, known for its lightweight structure and biodegradability. However, its mechanical properties were compared with other materials, such as Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) and Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG), to evaluate its structural performance. While PLA demonstrates high tensile strength, its impact resistance is lower than PETG and ABS, making it more prone to brittleness under sudden shocks. However, post-processing techniques such as resin coating and annealing may improve PLA’s mechanical durability by up to 35%, reinforcing its suitability for prosthetic applications [19]. No dynamic motion testing (speed–torque curves under varying loads) or long-term reliability testing (fatigue cycles, servo degradation, tendon wear) was conducted. As a result, long-term durability claims cannot be made at this stage. The mechanical properties of PLA against other materials is presented in Table 3. PLA, ABS, PETG tensile and impact values obtained from manufacturer datasheets (Prusa, eSun) and verified through three internal replicates (n = 3).

Table 3.

Mechanical Properties of PLA vs. Other Prosthetic Materials.

3.3. EMG-Based Control Performance and Response Evaluation

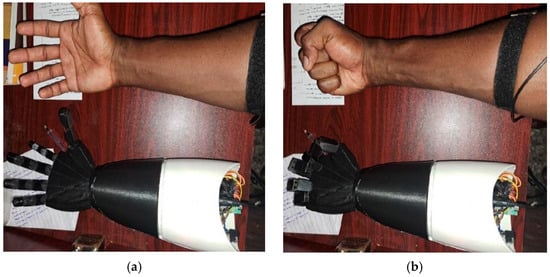

The efficiency of the EMG-based proportional control mechanism was evaluated by measuring the response time and stability of the prosthetic fingers. The study analyzed the prosthetic hand’s reaction to different EMG signal intensities, ensuring accurate and real-time movement replication. The practical evaluation of the arm is presented in Figure 13 for both open and closed arm application. The key performance metrics recorded include response time, which measures the time taken for the prosthetic fingers to react to muscle activation; signal stability, which evaluates the consistency of finger movements across repeated activations; and grip stability, which assesses the prosthetic hand’s ability to maintain a grasp without unintended release. The power grip exhibited the highest grip stability (97.5%), indicating strong reliability in holding objects. However, signal noise contributed to minor hand tremors, which could be improved using advanced digital filtering techniques (e.g., Kalman filtering, wavelet denoising). The performance metrics of the prosthetic control system is presented in Table 4.

Figure 13.

Practical Usage of the 3D-Printed Prosthesis Arm: (a) Open Palm; (b) Closed Palm.

Table 4.

Performance Metrics of the Prosthetic Control System.

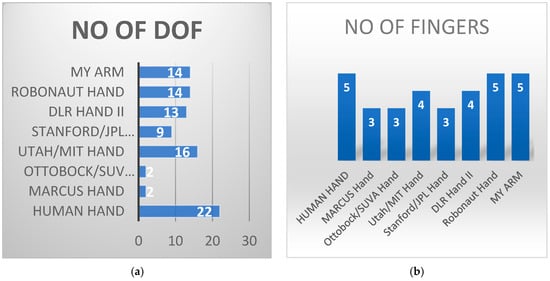

3.4. Performance Comparison

To benchmark the functionality of the developed prosthetic arm, its degrees of freedom (DOF), sensor usage, and actuation efficiency were compared with existing prosthetic hands. Although the anatomical design includes 14 structural DOF, the prosthesis provides 5 active, controllable DOF, consistent with the number of actuators. The remaining joints function as passive tendon-driven coupled joints, enabling naturalistic flexion but not independent control. The results are presented in Table 5. the absence of an opposable thumb limits its capability for precision grips such as lateral pinch, tripod grasp, and thumb–index manipulation. This restriction affects real-world tasks requiring fine manipulation such as buttoning clothes, writing, or picking up small objects [20]. Nonetheless, the design remains highly effective for power-grip dependent activities, which constitute the majority of daily functional tasks, and align with the scope of this study.

Table 5.

Comparative Analysis of Prosthetic Hand Designs.

- Human Hand: 22 DOF, 5 fingers, 38 actuators, sensory-rich, opposable thumb.

- MARCUS Hand: 2 DOF, 3 fingers, 5 sensors, 2 actuators, no opposable thumb.

- Ottobock/SUVA Hand: 2 DOF, 3 fingers, 1 sensor, 1 actuator, no opposable thumb.

- Utah/MIT Hand: 16 DOF, 4 fingers, 32 actuators, opposable thumb, high dexterity.

- Stanford/JPL Hand: 9 DOF, 3 fingers, 12 actuators, no sensors, no opposable thumb.

- DLR Hand II: 13 DOF, 4 fingers, 64 sensors, 13 actuators, no opposable thumb.

- Robonaut Hand: 14 DOF, 5 fingers, 44 sensors, 14 actuators, opposable thumb, highly dexterous.

- Proposed Arm: 14 DOF, 5 fingers, 3 sensors, 5 actuators, no opposable thumb, functional.

The total degrees of freedom (DOF) of the prosthetic arm can be determined as follows:

- Each of the four fingers has 3 joints, contributing 3 DOF per finger.

- The thumb has 2 joints, contributing 2 DOF.

Thus, the total DOF is calculated as:

- Fingers: 4 × 3 = 12 DOF

- Thumb: 2 DOF

- Total DOF: 12 + 2 = 14

Therefore, the prosthetic arm has 14 degrees of freedom, enabling dexterous movement and functionality. While the anatomical design includes 14 passive degrees of freedom, the functional DOF under active control is limited to five, corresponding to the number of actuators. The remaining joints move through tendon-driven coupling rather than independent actuation. Figure 14a,b shows the DOF comparison and Number of fingers comparison.

Figure 14.

Comparison of Various Prosthetic Arms: (a) Degree of Freedom; (b) No. of Fingers.

3.5. Machine Learning-Based Predictive Analysis

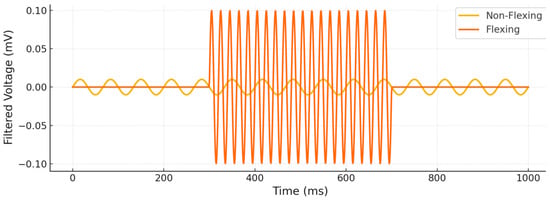

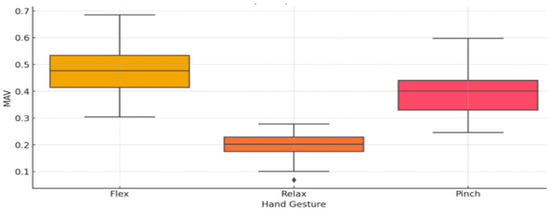

The integration of machine learning techniques significantly improves the precision and responsiveness of the prosthetic hand. By employing a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier, we aimed to enhance the classification of electromyography (EMG) signals into distinct hand gestures. The dataset for training and testing was obtained from EMG readings corresponding to different grip intensities, recorded from the muscle sensor interfaced with the Arduino Nano. The dataset consisted of 5000 EMG signal samples collected from 10 test subjects performing three distinct hand gestures: open palm, closed palm, and power grip. The raw EMG signal (shown earlier in Figure 9 and Figure 10) is further processed. Signal preprocessing included noise filtering using a bandpass filter (20–450 Hz), and feature extraction involved computing Root Mean Square (RMS), Mean Absolute Value (MAV), Zero Crossing Rate (ZCR), and Waveform Length (WL) as primary features., The processed EMG signals for both flexing and non flexing gesture is presented in Figure 15, while the mean absolute value distribution across gesture is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Processed EMG Signals for both Flexing and Non-Flexing Gesture.

Figure 16.

Mean Absolute Value (MAV) Distribution Across Gestures.

3.6. Model Training and Evaluation

The SVM classifier was trained with a 70:30 train-test split using a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel. Hyperparameter optimization for the SVM classifier was performed using a grid-search approach. The search space included the penalty parameter C ∈ {0.1, 1, 10, 100}, kernel coefficient γ ∈ {0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1}, and kernel type restricted to RBF due to its superior nonlinear classification capability. A 5-fold cross-validation strategy was applied during training to evaluate the generalization performance of each parameter combination. The optimal configuration was obtained at C = 10 and γ = 0.01, which provided the highest balance between accuracy and overfitting. The classification is presented in Table 6. The SVM classifier outperformed other models with an accuracy of 92.7%, indicating its superior capability in distinguishing muscle signal patterns effectively which is in agreement with a similar study [21].

Table 6.

Machine Learning Model Performance for EMG Signal Classification.

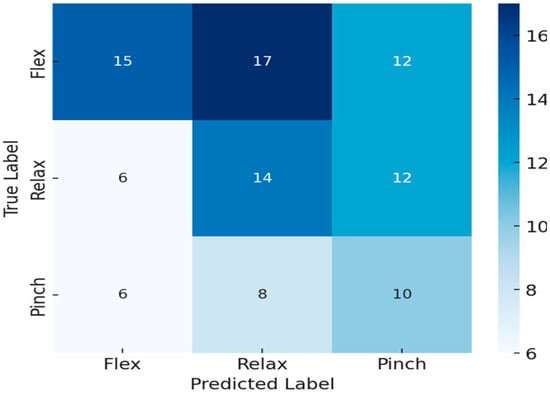

3.7. Confusion Matrix Analysis

A confusion matrix was generated to analyze misclassifications, as shown in Figure 17. The results indicate that the misclassification rate was lowest for the power grip, while some misclassification was observed between the open palm and closed palm gestures due to overlapping muscle activation.

Figure 17.

Confusion Matrix of the Best Performing Model (SVM).

3.8. Sensitivity Analysis

Based on the work done by [22], a sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the effect of EMG signal filtering and preprocessing on classification performance. The study found that optimal filtering (20–450 Hz bandpass) and feature selection (RMS, MAV, ZCR, WL) improved accuracy by approximately 8%, reinforcing the significance of preprocessing in EMG classification. The greatest improvement was achieved when combining RMS, MAV, ZCR, and WL features, leading to an accuracy boost from 84.9% to 92.7%. This analysis presented in Table 7 confirms that well-processed EMG data significantly enhances prosthetic responsiveness.

Table 7.

Sensitivity Analysis of Prosthetic Hand Control Parameters.

3.9. Practical Implications

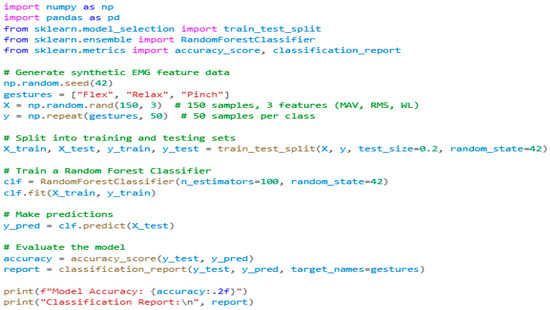

The high accuracy of the SVM-based classification system suggests that the developed prosthetic arm can reliably interpret user muscle signals with minimal misclassification. This result translates to improved real-time responsiveness, reducing lag between user intention and prosthetic movement. Future research could explore deep learning approaches (e.g., CNNs, LSTMs) to refine classification further and handle more complex gestures beyond power grip. The developed sourced code is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Snapshot of the Developed Python (version 3.8) Code.

4. Conclusions

This study presents the successful preliminary engineering validation of a low-cost, 3D-printed prosthetic arm that integrates single-channel electromyography (EMG), FFT-based feature extraction, and an SVM classifier for real-time gesture recognition. The device incorporates 14 passive anatomical degrees of freedom (DOF), with five actively actuated through a tendon-driven mechanism, resulting in an actuator-efficient mechanical design suitable for accessible prosthetic development. Despite lacking an opposable thumb, the device achieved strong functional performance, including a validated 96.4% power-grip success rate on objects up to 600 g. The SVM classifier, trained on 5000 EMG samples, attained a gesture-classification accuracy of 92.7%, demonstrating that reliable control can be obtained using minimal hardware and a single EMG channel. Mechanical evaluations further confirmed consistent grasp stability and adequate structural durability of the PLA-based additively manufactured components, reinforcing the system’s feasibility for low-cost, customizable prosthetic applications.

The contributions of this study are multifold. It demonstrates that a simplified EMG control framework, when paired with lightweight mechanical design and low-cost electronics, can deliver competitive real-time performance typically associated with more complex, multi-sensor systems. It also establishes a reproducible tendon-driven architecture capable of supporting essential daily tasks, providing a viable pathway for cost-sensitive prosthetic innovation. These results position the prototype as a promising platform for accessible prosthetic solutions, particularly in resource-constrained regions where affordability and manufacturability are paramount.

Nonetheless, the present work represents engineering-level validation rather than clinical confirmation. The reliance on a single EMG channel limits gesture separability and increases susceptibility to noise, and data collection from able-bodied participants does not capture the altered muscle physiology, electrode-placement challenges, or signal variability found in amputees. Additionally, long-term durability testing, expanded gesture sets, and improved embedded hardware capabilities remain necessary to advance the system toward real-world deployment. Future research will therefore focus on integrating multi-channel EMG, enhancing filtering and control algorithms, adopting higher-performance microcontrollers, conducting extended mechanical reliability studies, and carrying out structured trials involving transradial amputees. These efforts will support the progression of this prototype into a clinically relevant, scalable, and user-centered prosthetic solution.

Author Contributions

A.A. and C.A.; methodology and software, A.A. and T.-C.J. validation and formal analysis, C.A. and C.K.C. data curation and writing original draft, T.-C.J. and C.K.C. supervision and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are embedded within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged the Faculty of Engineering and Quantity Surveying, INTI International University, Malaysia, and the JENANO research group, South Africa, where the study was carried out.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Raval, N.M. Design and Development of Bio-Prosthetic Arm with Use of Artificial Intelligent. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2024, 12, 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bouteraa, Y.; Ben, I.; Ahmed, A. Training of Hand Rehabilitation Using Low Cost Exoskeleton and Vision-Based Game Interface. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2019, 96, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.; Portero, P.; Zambrano, M.; Rosero, R. Review of Robotic Prostheses Manufactured with 3D Printing: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, I.B.; Bouteraa, Y. Design and development of 3D printed myoelectric robotic exoskeleton for hand. Int. J. Smart Sens. Intell. Syst. 2017, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprnicky, J.; Najman, P.; Safka, J. 3D printed bionic prosthetic hands. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Workshop of Electronics, Control, Measurement, Signals and their Application to Mechatronics, ECMSM, Donostia, San Sebastian, Spain, 24–26 May 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, S.; Yadav, S.; Shankar, V.K.; Avinash, L. Development of 3D Printed Electromyography Controlled Bionic Arm. In Sustainable Machining Strategies for Better Performance. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, C.; Controzzi, M.; Carrozza, M.C. The SmartHand transradial prosthesis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2011, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dally, C.; Johnson, D.; Canon, M.; Ritter, S.; Mehta, K. Characteristics of a 3D-printed prosthetic hand for use in developing countries. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference, GHTC, Seattle, WA, USA, 8–11 October 2015; pp. 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, X.Q.; Jiang, L.; Wu, X.; Feng, W.; Zhou, D.; Liu, H. Biomechatronic design and control of an anthropomorphic artificial hand for prosthetic applications. Robotica 2016, 34, 2291–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khaldi, M.; Al Balushi, T.; Al Maqbali, A.; Rajakannu, A. Development of an Adaptive AI-Enhanced Prosthetic Arm for Physically Impaired Children. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2025, 12, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunla, A.; Akinlabi, E. Influence of reinforcements in friction stir processed magnesium alloys: Insight in medical applications. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 6, 025406. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2053-1591/aaeea8/meta (accessed on 8 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Yu, B.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L. Scavenging energy from the motion of human lower limbs via a piezoelectric energy harvester. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2017, 31, 1741011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, T. Fusion based Feature Extraction Analysis of ECG Signal Interpretation—A Systematic Approach. J. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L.; Su, Y.; Murray, A. Smart Wearables in Healthcare: Signal Processing, Device Development, and Clinical Applications. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1696924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Albis, G.; Forte, M.; Alrashadah, A.O.; Marini, L.; Corsalini, M.; Pilloni, A.; Capodiferro, S. Immediate Loading of Implants-Supported Fixed Partial Prostheses in Posterior Regions: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, S.H.; Hamzah, M.N.; Abdulateef, S.A.; Atiyah, Q.A. A Novel Design of Smart Knee Joint Prosthesis for Above-Knee Amputees. FME Trans. 2023, 51, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H.; Yahata, B.D.; Hundley, J.M.; Mayer, J.A.; Schaedler, T.A.; Pollock, T.M. 3D printing of high-strength aluminium alloys. Nature 2017, 549, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mick, S.; Marchand, C.; de Montalivet, É.; Richer, F.; Legrand, M.; Peudpièce, A.; Fabre, L.; Huchet, C.; Jarrassé, N. Smart ArM: A customizable and versatile robotic arm prosthesis platform for Cybathlon and research. J. Neuro Eng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, N. Development of patient specific, realistic, and reusable video assisted thoracoscopic surgery simulator using 3D printing and pediatric computed tomography images. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, T.H.; Ma’arof, M.I.N. Review of Nine 1DOF-Actuated Knee Exoskeletons for ACL Injuries. In Human Factors and Ergonomics Malaysia Biennial Conference; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Wang, D.; Wu, H.; Gao, L. A long short-term memory neural network model for knee joint acceleration estimation using mechanomyography signals. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17, 1729881420968702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, E.O.; Adetunla, A.; Awesu, A.; Ajayi, O.K. Sensitivity Analysis of a Smart 3D-Printed Hand Prosthetic. J. Robot. 2022, 2022, 9145352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).