The Technological and Psychological Aspects of Upper Limb Prostheses Abandonment: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

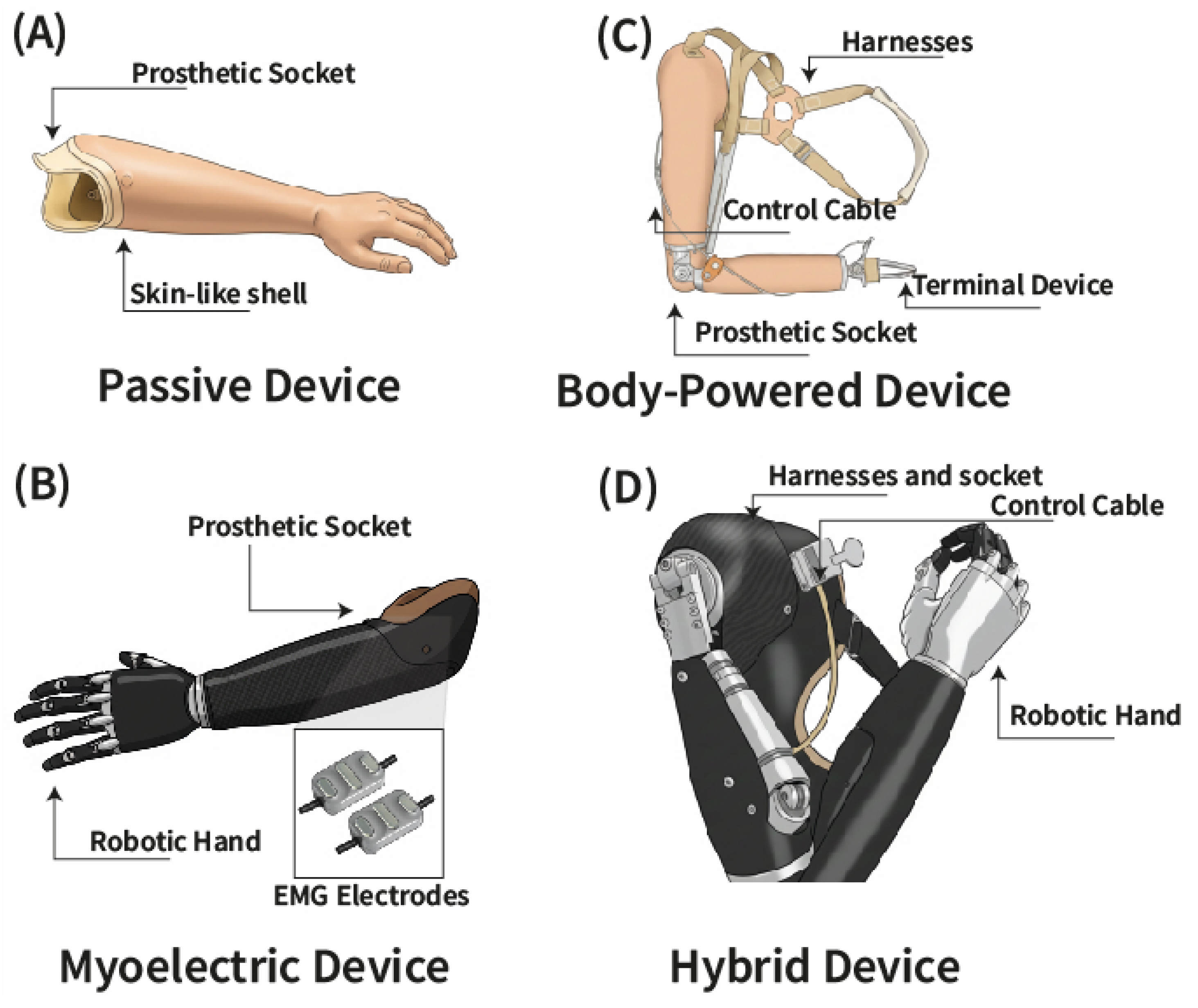

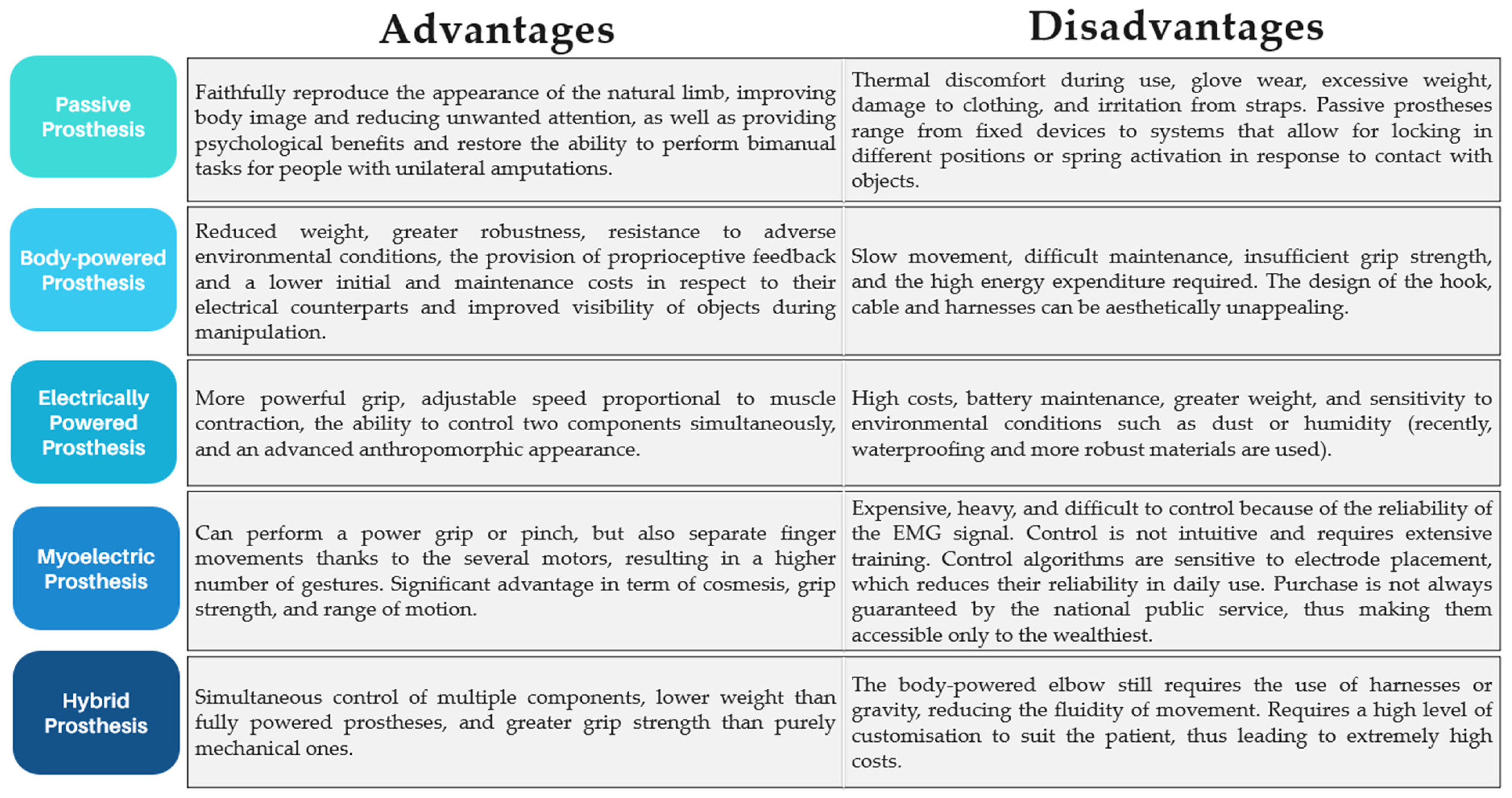

2. Technological Challenges: Upper Limb Prosthetic Devices

2.1. Passive Prostheses

2.2. Body-Powered Prostheses

2.3. Electrically Powered Prostheses

2.4. Myoelectric Prostheses

2.5. Hybrid Prostheses

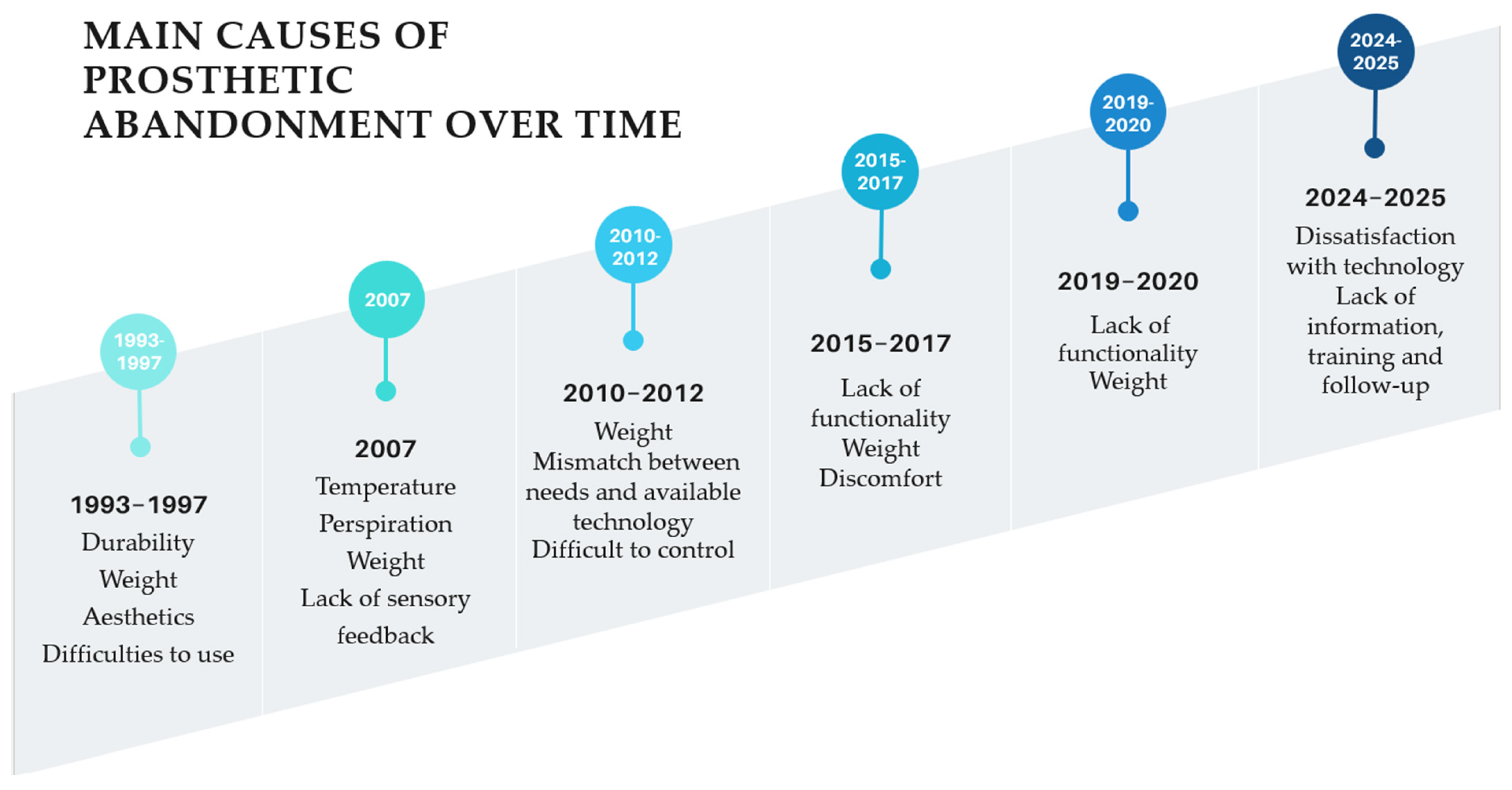

3. Prosthesis Abandonment: Main Factors

Psychological and Social Implications of Wearing a Prosthesis

4. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | Body-Powered |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| sEMG | Surface Electromyography |

| TD | Terminal Device |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| PLP | Phantom Limb Pain |

| RHI | Rubber Hand Illusion |

| LD | Linear Dichroism |

| SER | Sport, Exercise, Recreation |

References

- Pezzin, L.E.; Dillingham, T.R.; Mackenzie, E.J. Rehabilitation and the Long-Term Outcomes of Persons with Trauma-Related Amputations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, C.L.; Westcott-Mccoy, S.; Weaver, M.R.; Haagsma, J.; Kartin, D. Global Prevalence of Traumatic Non-Fatal Limb Amputation. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2021, 45, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumbaširević, M.; Lesic, A.; Palibrk, T.; Milovanovic, D.; Zoka, M.; Kravić-Stevović, T.; Raspopovic, S.S. The Current State of Bionic Limbs from the Surgeon’s Viewpoint. EFORT Open Rev. 2020, 5, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, J.A.; Churovich, K.; Anderson, A.B.; Potter, B.K. Estimating Recent US Limb Loss Prevalence and Updating Future Projections. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2024, 6, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler-Graham, K.; MacKenzie, E.J.; Ephraim, P.L.; Travison, T.G.; Brookmeyer, R. Estimating the Prevalence of Limb Loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, D.; Romero, E.; Abarca, V.E.; Elias, D.A. Upper Limb Prostheses by the Level of Amputation: A Systematic Review. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, R.; Sidhu, S.; Romine, L.; Meyer, M.S.; Duncan, S.F.M. Interscapulothoracic (Forequarter) Amputation for Malignant Tumors Involving the Upper Extremity: Surgical Technique and Case Series. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2014, 23, e127–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC). Amputations of Upper and Lower Extremities, Active and Reserve Components Approved, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2011. MSMR 2012, 19, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cancio, L.C.; Jimenez-Reyna, J.F.; Barillo, D.J.; Walker, S.C.; McManus, A.T.; Vaughan, G.M. One Hundred Ninety-Five Cases of High-Voltage Electric Injury. J. Burn. Care Rehabil. 2005, 26, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.L.; Hayda, R.; Chen, A.T.; Carlini, A.R.; Ficke, J.R.; Mackenzie, E.J. The Military Extremity Trauma Amputation/Limb Salvage (METALS) Study: Outcomes of Amputation Compared with Limb Salvage Following Major Upper-Extremity Trauma. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2019, 101, 1470–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, P.; Stineman, M.G.; Dillingham, T.R. Epidemiology of Limb Loss. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeland, A.E.; Psonak, R. Traumatic Below-Elbow Amputations. Orthopedics 2007, 30, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dillingham, T.R.; Pezzin, L.E.; MacKenzie, E.J. Limb Amputation and Limb Deficiency: Epidemiology and Recent Trends in the United States. South Med. J. 2002, 95, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinn, S.R.; Goodman, G. Effective Assessments to Identify Overuse Injuries in Unaffected Limbs of Persons with Unilateral Upper Limb Amputations. J. Hand Ther. 2021, 34, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das De, S.; Liang, Z.C.; Cheah, A.E.J.; Puhaindran, M.E.; Lee, E.Y.; Lim, A.Y.T.; Chong, A.K.S. Emergency Hand and Reconstructive Microsurgery in the COVID-19–Positive Patient. J. Hand Surg. 2020, 45, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, L.; Ekerholm, S.; Borgia, M.; Clark, M.A. A National Study of Veterans with Major Upper Limb Amputation: Survey Methods, Participants, and Summary Findings. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raspopovic, S.; Valle, G.; Petrini, F.M. Sensory Feedback for Limb Prostheses in Amputees. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, S.L.H. Care of the Combat Amputee; Pasquina, P.F., Cooper, R.A., Eds.; Office of The Surgeon General Department of the Army: Houston, TX, USA; United States of America and US Army Medical Department Center: San Antonio, TX, USA; School Fort Sam Houston: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2009; Volume XLI, pp. 597–605.

- INAIL. Sanità Solo Il 5 Di Amputazioni è Legata a Infortuni Sul Lavoro. Available online: https://www.inail.it/cs/internet/comunicazione/news-ed-eventi/news/p1780018061_sanita_solo_il_5_di_amputazi.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Atroshi, I.; Rosberg, H.E. Epidemiology of Amputations and Severe Injuries of the Hand. Hand Clin. 2001, 17, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, L.; Borgia, M.; Clark, M. Function and Quality of Life of Unilateral Major Upper Limb Amputees: Effect of Prosthesis Use and Type. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintle, S.M.; Baechler, M.F.; Nanos, G.P.; Forsberg, J.A.; Potter, B.K. Traumatic and Trauma-Related Amputations: Part II: Upper Extremity and Future Directions. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2010, 92, 2934–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddiss, E.A.; Chau, T.T. Multivariate Prediction of Upper Limb Prosthesis Acceptance or Rejection. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2008, 3, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apagüeño, B.; Munkwitz, S.E.; Mata, N.V.; Alessia, C.; Nayak, V.V.; Coelho, P.G.; Fullerton, N. Optimal Sites for Upper Extremity Amputation: Comparison Between Surgeons and Prosthetists. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddiss, E.; Chau, T. Upper Limb Prosthesis Use and Abandonment: A Survey of the Last 25 Years. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2007, 31, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, T.W.; Hagen, A.D.; Wood, M.B. Prosthetic Usage in Major Upper Extremity Amputations. J. Hand Surg. 1995, 20, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsook, D.; Becerra, L. Emotional Pain without Sensory Pain-Dream on? Neuron 2009, 61, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotigă, A.C.; Zivari, M.; Cursaru, A.; Aliuş, C.; Ivan, C. Amputation, Psychological Consequences, and Quality of Life among Romanian Patients. Rom. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2020, 3, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.-H.; Kang, S.-H.; Seo, W.-S.; Koo, B.-H.; Kim, H.-G.; Yun, S.-H. Psychiatric Understanding and Treatment of Patients with Amputations. Yeungnam Univ. J. Med. 2021, 38, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Z.B.; De’Ath, H.D.; Sharp, G.; Tai, N.R.M. Factors Affecting Outcome after Traumatic Limb Amputation. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, H. Phantom-Limb Pain: Characteristics, Causes, and Treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2002, 1, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, O.; MacLachlan, M. Psychosocial Adjustment to Lower-Limb Amputation: A Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2004, 26, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Ripley, D.; Pentland, B.; Todd, I.; Hunter, J.; Hutton, L.; Philip, A. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms after Lower Limb Amputation: The Rise and Fall. Clin. Rehabil. 2009, 23, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckechnie, P.S.; John, A. Anxiety and Depression Following Traumatic Limb Amputation: A Systematic Review. Injury 2014, 45, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, S.L.; Lura, D.J.; Highsmith, M.J. Differences in Myoelectric and Body-Powered Upper-Limb Prostheses: Systematic Literature Review. JPO J. Prosthet. Orthot. 2017, 29, P4–P16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, D.M.; MacLachlan, M. Coping Strategies as Predictors of Psychosocial Adaptation in a Sample of Elderly Veterans with Acquired Lower Limb Amputations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaine, W.J.; Smart, C.; Bransby-Zachary, M. Upper Limb Traumatic Amputees Review of Prosthetic Use. J. Hand Surg. 1997, 22, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senra, H.; Oliveira, R.A.; Leal, I.; Vieira, C. Beyond the Body Image: A Qualitative Study on How Adults Experience Lower Limb Amputation. Clin. Rehabil. 2012, 26, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roșca, A.C.; Baciu, C.C.; Burtăverde, V.; Mateizer, A. Psychological Consequences in Patients with Amputation of a Limb. An Interpretative-Phenomenological Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 537493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Emery, G. Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective; Basic Books/Hachette Book Group, Ed.; Basic Books/Hachette Book Group: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond; The Guilford Press (A Division of Guilford Publications, Inc.): New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Esquenazi, A. Amputation Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Restoration. From Surgery to Community Reintegration. Disabil. Rehabil. 2004, 26, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, D.; Beghi, M.; Bigoni, M.; Diotti, S.; Perin, C.; Peroni, F.; Turati, M.; Zanchi, N.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Maria Cornaggia, C. Prosthesis Rejection in Individuals with Limb Amputation: A Narrative Review with Respect to Rehabilitation. Riv. Psichiatr. 2021, 56, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Salminger, S.; Stino, H.; Pichler, L.H.; Gstoettner, C.; Sturma, A.; Mayer, J.A.; Szivak, M.; Aszmann, O.C. Current Rates of Prosthetic Usage in Upper-Limb Amputees–Have Innovations Had an Impact on Device Acceptance? Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 3708–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.A.; Paul, R.; Forthofer, M.; Wurdeman, S.R. Impact of Time to Receipt of Prosthesis on Total Healthcare Costs 12 Months Postamputation. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddiss, E.; McKeever, P.; Lindsay, S.; Chau, T. Implications of Prosthesis Funding Structures on the Use of Prostheses: Experiences of Individuals with Upper Limb Absence. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2011, 35, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henao, S.C.; Cuartas-Escobar, S.; Salazar-Salgado, S.; Posada-Borrero, A.M. Upper-Limb Prosthetic Requirements from the Healthcare Providers, End-Users and Relatives’ Perspectives. J. Hand Ther. 2025; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Chung, K.C.; Sterbenz, J.; Shauver, M.J.; Tanaka, H.; Nakamura, T.; Oba, J.; Chin, T.; Hirata, H. Cross-Sectional International Multicenter Study on Quality of Life and Reasons for Abandonment of Upper Limb Prostheses. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, E2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linde, H.; Hofstad, C.J.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Postema, K.; Van Limbeek, J. From Satisfaction to Expectation: The Patient’s Perspective in Lower Limb Prosthetic Care. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, E.C.; Schrier, E.; DIjkstra, P.U.; Geertzen, J.H.B. Prosthesis Satisfaction in Lower Limb Amputees: A Systematic Review of Associated Factors and Questionnaires. Medicine 2018, 97, e12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazpour, M.; Mardani, M.A.; Bani, M.A.; Zarezadeh, F.; Hutchins, S.W. Design and Fabrication of a Finger Prosthesis Based on a New Method of Suspension. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2013, 37, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, L.; Intintoli, M.; Prigge, P.; Bollinger, C.; Walters, L.S.; Conyers, D.; Miguelez, J.; Ryan, T. A Narrative Review: Current Upper Limb Prosthetic Options and Design. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 15, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistenberg, R.S. Prosthetic Choices for People with Leg and Arm Amputations. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 25, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, J.; Vincent, C.; Dith Boulianne, É.; Lajoie, S.; Mercier, C. Interactions Between the Phantom Limb Sensations, Prosthesis Use, and Rehabilitation as Seen by Amputees and Health Professionals. JPO J. Prosthet. Orthot. 2012, 24, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Catalan, M.; Zbinden, J.; Millenaar, J.; D’aCcolti, D.; Controzzi, M.; Clemente, F.; Cappello, L.; Earley, E.J.; Mastinu, E.; Kolankowska, J.; et al. A Highly Integrated Bionic Hand with Neural Control and Feedback for Use in Daily Life. Sci. Robot. 2023, 8, eadf7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, A.E.; Kuiken, T.A. Neural Interfaces for Control of Upper Limb Prostheses: The State of the Art and Future Possibilities. PM&R 2011, 3, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Wang, B.; Alas, H.; Jones, Q.; Clark, C.; Lazar, S.; Malik, S.; Graham, J.; Talaat, Y.; Shin, C.; et al. Prosthesis Embodiment in Lower Extremity Limb Loss: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smail, L.C.; Neal, C.; Wilkins, C.; Packham, T.L. Comfort and Function Remain Key Factors in Upper Limb Prosthetic Abandonment: Findings of a Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 16, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeringer, J.A.; Hogan, N. Performance of Above Elbow Body-Powered Prostheses in Visually Guided Unconstrained Motion Tasks. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1995, 42, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, L.; Borgia, M.; Silver, B.; Cancio, J. Systematic Review of Measures of Impairment and Activity Limitation for Persons with Upper Limb Trauma and Amputation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 1863–1892.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belter, J.T.; Segil, J.L.; Dollar, A.M.; Weir, R.F. Mechanical Design and Performance Specifications of Anthropomorphic Prosthetic Hands: A Review. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2013, 50, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyberd, P.J.; Hill, W. Survey of Upper Limb Prosthesis Users in Sweden, the United Kingdom and Canada. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2011, 35, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.M.; Lock, B.A.; Stubblefield, K.A. Patient Training for Functional Use of Pattern Recognition-Controlled Prostheses. J. Prosthet. Orthot. 2012, 24, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, R.F.F. Design of artificial arms and hands for prosthetic applications. In Standard Handbook of Biomedical Engineering and Design; The McGraw-Hill Companies: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dimante, D.; Logina, I.; Sinisi, M.; Krūmiņa, A. Sensory Feedback in Upper Limb Prostheses. Proc. Latv. Acad. Sci. Sect. B Nat. Exact Appl. Sci. 2020, 74, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mablekos-Alexiou, A.; Bertos, G.A.; Papadopoulos, E. A biomechatronic Extended Physiological Proprioception (EPP) controller for upper-limb prostheses. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Engdahl, S.M.; Meehan, S.K.; Gates, D.H. Differential Experiences of Embodiment between Body-Powered and Myoelectric Prosthesis Users. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muilenburg, A.L.; Leblanc, M.A. Body-Powered Upper-Limb Components. In Comprehensive Management of the Upper-Limb Amputee; Atkins, D.J., Meier, R.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc, M.A.M.E. Innovation and Improvement of Body-Powered Arm Prostheses: A First Step. Clin. Prosthet. Orthot. 1985, 9, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraja, V.H.; Bergmann, J.H.M.; Sen, D.; Thompson, M.S. Examining the Needs of Affordable Upper Limb Prosthetic Users in India: A Questionnairebased Survey. Technol. Disabil. 2016, 28, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcfarland, L.V.; Winkler, S.L.H.; Heinemann, A.W.; Jones, M.; Esquenazi, A. Unilateral Upper-Limb Loss: Satisfaction and Prosthetic-Device Use in Veterans and Servicemembers from Vietnam and OIF/OEF Conflicts. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2010, 47, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddiss, E.; Beaton, D.; Chau, T. Consumer Design Priorities for Upper Limb Prosthetics. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2007, 2, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Jabban, L.; Sui, X.; Zhang, D. Motion Intention Prediction and Joint Trajectories Generation Toward Lower Limb Prostheses Using EMG and IMU Signals. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 10719–10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D.; Kunz, T.S.; Gardner, D.; Shelley, M.K.; Davis, A.J.; Gillespie, R.B. An Empirical Evaluation of Force Feedback in Body-Powered Prostheses. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujaklija, I.; Farina, D.; Aszmann, O.C. New Developments in Prosthetic Arm Systems. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2016, 8, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Yánez, A.; Benalcázar, M.E.; Mena-Maldonado, E. Real-Time Hand Gesture Recognition Using Surface Electromyography and Machine Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.-J.; Shiu, J.-R.; Cheng, C.-K.; Lai, J.-S.; Tsao, H.-W.; Kuo, T.-S. The Application of Cepstral Coefficients and Maximum Likelihood Method in EMG Pattern Recognition. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1995, 42, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, A.B.; Weir, R.F. Muscle Synergies as a Predictive Framework for the EMG Patterns of New Hand Postures. J. Neural Eng. 2009, 6, 036004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.H.; Hargrove, L.J. Comparison of SURFACE and Intramuscular EMG Pattern Recognition for Simultaneous Wrist/Hand Motion Classification. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Osaka, Japan, 3–7 July 2013; IEEE: Osaka, Japan, 2013. ISBN 9781457702167. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, R.F.; Troyk, P.R.; DeMichele, G.A.; Kerns, D.A.; Schorsch, J.F.; Maas, H. Implantable Myoelectric Sensors (IMESs) for Intramuscular Electromyogram Recording. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 56, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastinu, E.; Clemente, F.; Sassu, P.; Aszmann, O.; Brånemark, R.; Håkansson, B.; Controzzi, M.; Cipriani, C.; Ortiz-Catalan, M. Grip Control and Motor Coordination with Implanted and Surface Electrodes While Grasping with an Osseointegrated Prosthetic Hand. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Catalan, M.; Brånemark, R.; Håkansson, B. Direct Neural Sensory Feedback and Control via Osseointegration. In Proceedings of the XVI World Congress of the International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics (ISPO), Cape Town, South Africa, 8–11 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Earley, E.J.; Kristoffersen, M.B.; Ortiz-Catalan, M. Comparing Implantable Epimysial and Intramuscular Electrodes for Prosthetic Control. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1568212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Catalan, M.; Mastinu, E.; Sassu, P.; Aszmann, O.; Brånemark, R. Self-Contained Neuromusculoskeletal Arm Prostheses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Catalan, M.; Håkansson, B.; Brånemark, R. An Osseointegrated Human-Machine Gateway for Long-Term Sensory Feedback and Motor Control of Artificial Limbs. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 257re6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbinden, J.; Sassu, P.; Mastinu, E.; Earley, E.J.; Munoz-Novoa, M.; Brånemark, R.; Ortiz-Catalan, M. Improved Control of a Prosthetic Limb by Surgically Creating Electro-Neuromuscular Constructs with Implanted Electrodes. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabq3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schone, H.R.; Udeozor, M.; Moninghoff, M.; Rispoli, B.; Vandersea, J.; Lock, B.; Hargrove, L.; Makin, T.R.; Baker, C.I. Should Bionic Limb Control Mimic the Human Body? Impact of Control Strategy on Bionic Hand Skill Learning. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Schultz, A.E.; Kuiken, T.A. Quantifying Pattern Recognition- Based Myoelectric Control of Multifunctional Transradial Prostheses. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2010, 18, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwell, A.; Kenney, L.; Thies, S.; Galpin, A.; Head, J. The Reality of Myoelectric Prostheses: Understanding What Makes These Devices Difficult for Some Users to Control. Front. Neurorobot. 2016, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widehammar, C.; Lidström Holmqvist, K.; Hermansson, L. Training for Users of Myoelectric Multigrip Hand Prostheses: A Scoping Review. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2021, 45, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livneh, H.; Richard, F.; Antonak, E.D.; John, G. Multidimensional Investigation of the Structure of Coping Among People with Amputations. Psychosomatics 2020, 41, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brack, R.; Amalu, E.H. A Review of Technology, Materials and R&D Challenges of Upper Limb Prosthesis for Improved User Suitability. J. Orthop. 2021, 23, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreenivasan, N.; Ulloa Gutierrez, D.F.; Bifulco, P.; Cesarelli, M.; Gunawardana, U.; Gargiulo, G.D. Towards Ultra Low-Cost Myoactivated Prostheses. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9634184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.; D’cRuz, K.; Ross, P.; Anderson, S. Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators to Community Reintegration for Adults Following Traumatic Upper Limb Amputation: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabban, L.; Metcalfe, B.W.; Raines, J.; Zhang, D.; Ainsworth, B. Experience of Adults with Upper-Limb Difference and Their Views on Sensory Feedback for Prostheses: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddiss, E.; Chau, T. Upper-Limb Prosthetics: Critical Factors in Device Abandonment. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 86, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, F.; Ciancio, A.L.; Sacchetti, R.; Davalli, A.; Cutti, A.G.; Guglielmelli, E.; Zollo, L. Literature Review on Needs of Upper Limb Prosthesis Users. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kejlaa, G.H. Consumer Concerns and the Functional Value of Prostheses to Upper Limb Amputees. Prosthetics Orthot. Int. 1993, 17, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silcox, D.H., 3rd; Rook, M.D.; Vogel, R.R.; Fleming, L.L. Myoelectric Prostheses. A Long-Term Follow-up and a Study of the Use of Alternate Prostheses. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1993, 75, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, D.J.; Heard, D.; Donovan, W.H. Epidemiologic Overview of individuals with Upper-Limb Loss and Their Reported Research Priorities. JPO J. Prosthet. Orthot. 1996, 8, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østlie, K.; Lesjø, I.M.; Franklin, R.J.; Garfelt, B.; Skjeldal, O.H.; Magnus, P. Prosthesis Rejection in Acquired Major Upper-Limb Amputees: A Population-Based Survey. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2012, 7, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Owaidi, N.; Mora, M.C.; Ventura, S. Analysis on the Rejection and Device Passivity Problems with Myoelectric Prosthetic Hand Control. In Proceedings of the World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, WMSCI, Virtual, 10–13 September 2024; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, L.J.; Borgia, M.; Clark, M.A.; Ni, P. Out-of-Pocket Costs and Affordability of Upper Limb Prostheses. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2024, 48, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffalitzky, E.; Ni Mhurchadha, S.; Gallagher, P.; Hofkamp, S.; MacLachlan, M.; Wegener, S.T. Identifying the Values and Preferences of Prosthetic Users: A Case Study Series Using the Repertory Grid Technique. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2009, 33, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.F. Upper Extremity Amputation and Prosthetics. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2001, 38, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Saradjian, A.; Thompson, A.R.; Datta, D. The Experience of Men Using an Upper Limb Prosthesis Following Amputation: Positive Coping and Minimizing Feeling Different. Disabil. Rehabil. 2008, 30, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, I.C.; Jape, V.S. Retrospective study of 14,400 civilian disabled (new) treated over 25 years at an Artificial Limb Centre. Prosthetics Orthot. Int. 1982, 6, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, L.; Benz, H.; Borgia, M.; Clark, M.A. Patient Perspectives on Benefits and Risks of Implantable Interfaces for Upper Limb Prostheses: A National Survey. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 2019, 16, 515–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylatiuk, C.; Schulz, S.; Döderlein, L. Results of an Internet Survey of Myoelectric Prosthetic Hand Users. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2007, 31, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, R.H.; Choppa, A.J.; Johnson, C.B. The Person with Amputation and Their Life Care Plan. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 24, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millstein, S.G.; Heger, H.; Hunter, G.A. Prosthetic Use in Adult Upper Limb Amputees: A Comparison of the Body Powered and Electrically Powered Prostheses. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 1986, 10, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engeberg, E.D.; Meek, S. Enhanced Visual Feedback for Slip Prevention with a Prosthetic Hand. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2012, 36, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, S.; Wiggins, S.; Sanford, A. Perceptions of Cosmesis and Function in Adults with Upper Limb Prostheses: A Systematic Literature Review. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2011, 35, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.J.; Krusienski, D.J.; Sarnacki, W.A.; Wolpaw, J.R. Emulation of Computer Mouse Control with a Noninvasive Brain-Computer Interface. J. Neural Eng. 2008, 5, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Qin, S. An Interdisciplinary Approach and Advanced Techniques for Enhanced 3D-Printed Upper Limb Prosthetic Socket Design: A Literature Review. Actuators 2023, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carro, R.M.; Costales, F.G.; Ortigosa, A. Serious Games for Training Myoelectric Prostheses through Multi-Contact Devices. Children 2022, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.S.; Mansfield, E. Prosthetic Training: Upper Limb. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 25, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, J.; Earley, E.J.; Potter, B.K.; Grover, P.; Thomas, P.; Stark, G.; White, A. Innovations in Amputee Care in the United States: Access, Ethics, and Equity. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannenberg, A.; Seidinger, S. Health Economics in the Field of Prosthetics and Orthotics: A Global Perspective. Can. Prosthet. Orthot. J. 2021, 4, 35298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, C.D.; Brenner, J.K. The Use of Preparatory/Evaluation/Training Prostheses in Developing Evidenced-Based Practice in Upper Limb Prosthetics. JPO J. Prosthet. Orthot. 2008, 20, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, G.; Zürich, E.; Tayeb, Z.; Iberite, F.; Ienca, M.; Valeriani, D.; Santoro, F. The Present and Future of Neural Interfaces. Front. Neurorobot. 2020, 16, 953968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.D. Neuron Devices: Emerging Prospects in Neural Interfaces and Recognition. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2022, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddiss, E.; Chau, T. The Roles of Predisposing Characteristics, Established Need, and Enabling Resources on Upper Extremity Prosthesis Use and Abandonment. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2007, 2, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, X.; Krueger, T.B.; Lago, N.; Micera, S.; Stieglitz, T.; Dario, P. A Critical Review of Interfaces with the Peripheral Nervous System for the Control of Neuroprostheses and Hybrid Bionic Systems. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2005, 10, 229–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, D.K.; Durand, D.M. Chronic Measurement of the Stimulation Selectivity of the Flat Interface Nerve Electrode. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 51, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.M.; Dhillon, G.S.; Horch, K.W. Fabrication and Characteristics of an Implantable, Polymer-Based, Intrafascicular Electrode. J. Neurosci. Methods 2003, 131, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.J.; Shenoy, P.; Chalodhorn, R.; Rao, R.P.N. Control of a Humanoid Robot by a Noninvasive Brain-Computer Interface in Humans. J. Neural Eng. 2008, 5, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturrate, I.; Antelis, J.M.; Kübler, A.; Minguez, J. A Noninvasive Brain-Actuated Wheelchair Based on a P300 Neurophysiological Protocol and Automated Navigation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collu, R.; Earley, E.J.; Barbaro, M.; Ortiz-Catalan, M. Non-Rectangular Neurostimulation Waveforms Elicit Varied Sensation Quality and Perceptive Fields on the Hand. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Anna, E.; Petrini, F.M.; Artoni, F.; Popovic, I.; Simanić, I.; Raspopovic, S.; Micera, S. A Somatotopic Bidirectional Hand Prosthesis with Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Based Sensory Feedback. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, L.E.; Dragomir, A.; Betthauser, J.L.; Hunt, C.L.; Nguyen, H.H.; Kaliki, R.R.; Thakor, N.V. Prosthesis with Neuromorphic Multilayered E-Dermis Perceives Touch and Pain. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3, eaat3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Accolti, D.; Dejanovic, K.; Cappello, L.; Mastinu, E.; Ortiz-Catalan, M.; Cipriani, C. Decoding of Multiple Wrist and Hand Movements Using a Transient EMG Classifier. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, G.K.; Dosen, S.; Castellini, C.; Farina, D. Multichannel Electrotactile Feedback for Simultaneous and Proportional Myoelectric Control. J. Neural Eng. 2016, 13, 056015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, T.G.; Greenspon, C.M.; Verbaarschot, C.; Valle, G.; Hughes, C.L.; Boninger, M.L.; Bensmaia, S.J.; Gaunt, R.A. Biomimetic Stimulation Patterns Drive Natural Artificial Touch Percepts Using Intracortical Microstimulation in Humans. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 036014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, T.; Fukuma, R.; Seymour, B.; Tanaka, M.; Hosomi, K.; Yamashita, O.; Kishima, H.; Kamitani, Y.; Saitoh, Y. BCI Training to Move a Virtual Hand Reduces Phantom Limb Pain: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Neurology 2020, 95, E417–E426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engdahl, S.M.; Chestek, C.A.; Kelly, B.; Davis, A.; Gates, D.H. Factors Associated with Interest in Novel Interfaces for Upper Limb Prosthesis Control. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engdahl, S.M.; Christie, B.P.; Kelly, B.; Davis, A.; Chestek, C.A.; Gates, D.H. Surveying the Interest of Individuals with Upper Limb Loss in Novel Prosthetic Control Techniques. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2015, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Kalpakjian, C.; Larrága-Martínez, M.; Chestek, C.A.; Gates, D.H. Priorities for the Design and Control of Upper Limb Prostheses: A Focus Group Study. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.; Valle, G.; Controzzi, M.; Strauss, I.; Iberite, F.; Stieglitz, T.; Granata, G.; Rossini, P.M.; Petrini, F.; Micera, S.; et al. Intraneural Sensory Feedback Restores Grip Force Control and Motor Coordination While Using a Prosthetic Hand. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 026034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopf, R.; Polito, V.; Moore, J. Revisiting the Link between Body and Agency: Visual Movement Congruency Enhances Intentional Binding but Is Not Body-Specifics. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.R.; Schüür, F.; Kammers, M.P.M.; Tsakiris, M.; Haggard, P. What Is Embodiment? A Psychometric Approach. Cognition 2008, 107, 978–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synofzik, M.; Vosgerau, G.; Newen, A. I Move, Therefore I Am: A New Theoretical Framework to Investigate Agency and Ownership. Conscious. Cogn. 2008, 17, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsakiris, M. My Body in the Brain: A Neurocognitive Model of Body-Ownership. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marasco, P.D.; Hebert, J.S.; Sensinger, J.W.; Beckler, D.T.; Thumser, Z.C.; Shehata, A.W.; Williams, H.E.; Wilson, K.R. Neurorobotic Fusion of Prosthetic Touch, Kinesthesia, and Movement in Bionic Upper Limbs Promotes Intrinsic Brain Behaviors. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabf3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graczyk, E.L.; Gill, A.; Tyler, D.J.; Resnik, L.J. The Benefits of Sensation on the Experience of a Hand: A Qualitative Case Series. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R.S.; Westling, G. Roles of Glabrous Skin Receptors and Sensorimotor Memory in Automatic Control of Precision Grip When Lifting Rougher or More Slippery Objects. Exp. Brain Res. 1984, 56, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanke, O. Multisensory Brain Mechanisms of Bodily Self-Consciousness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, B.W.; Datta, D.; Howitt, J. A Pilot Study Comparing the Cognitive Demand of Walking for Transfemoral Amputees Using the Intelligent Prosthesis with That Using Conventionally Damped Knees. Clin. Rehabil. 2000, 14, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, T.R.; De Vignemont, F.; Faisal, A.A. Neurocognitive Barriers to the Embodiment of Technology. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, F.M.; Valle, G.; Strauss, I.; Granata, G.; Di Iorio, R.; D’Anna, E.; Čvančara, P.; Mueller, M.; Carpaneto, J.; Clemente, F.; et al. Six-Month Assessment of a Hand Prosthesis with Intraneural Tactile Feedback. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graczyk, E.L.; Resnik, L.; Schiefer, M.A.; Schmitt, M.S.; Tyler, D.J. Home Use of a Neural-Connected Sensory Prosthesis Provides the Functional and Psychosocial Experience of Having a Hand Again. Sci. Rep. 2018, 88, 9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybarczyk, B.D.; Nyenhuis, D.L.; Nicholas, J.J.; Schulz, R.; Alioto, R.J.; Blair, C. Social Discomfort and Depression in a Sample of Adults with Leg Amputations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1992, 73, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer, D.G.; Kessler, R.C.; Mcgonagle, K.A.; Swartz, M.S. The Prevalence and Distribution of Major Depression in a National Community Sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, W.W. Epidemiologic Evidence on the Comorbidity of Depression and Diabetes. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cansever, A. Depression in Men with Traumatic Part Amputation: A Comparison to Men with Surgical Part Amputation. Mil. Med. 2003, 168, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, K.; Brånemark, R. Consequences of Non-Vascular Trans-Femoral Amputation: A Survey of Quality of Life, Prosthetic Use and Problems. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2001, 25, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzin, L.E.; Dillingham, T.R.; MacKenzie, E.J.; Ephraim, P.; Rossbach, P. Use and Satisfaction with Prosthetic Limb Devices and Related Services. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybarczyk, B.; Nyenhuis, D.L.; Nicholas, J.J.; Cash, S.M.; Kaiser, J. Body Image, Perceived Social Stigma, and the Prediction of Psychosocial Adjustment to Leg Amputation. Rehabil. Psychol. 1995, 40, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livneh, H. Psychosocial Adaptation to Chronic Illness and Disability: A Conceptual Framework. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2001, 44, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, I.Z.; Crook, J.; Meloche, G.R.; Berkowitz, J.; Milner, R.; Zuberbier, O.A.; Meloche, W. Psychosocial Factors Predictive of Occupational Low Back Disability: Towards Development of a Return-to-Work Model. Pain 2004, 107, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradway, J.K.; Malone, J.M.; Racy, J.; Leal, J.M.; Jana Poole, C. Psychological Adaptation to Amputation: An Overview. Orthot. Prosthet. 1984, 38, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Livneh, H.; Antonak, R.F.; Gerhardt, J. Psychosocial Adaptation to Amputation: The Role of Sociodemographic Variables, Disability-Related Factors and Coping Strategies. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 1999, 22, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohenewa, E.; Yendork, J.S.; Amponsah, B.; Owusu-Ansah, F.E. “After Cutting It, Things Have Never Remained the Same”: A Qualitative Study of the Perspectives of Amputees and Their Caregivers. Health Expect. 2025, 28, e70148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergo, M.F.d.C.; Prebianchi, H.B. Emotional Aspects Present in the Lives of Amputees: A Literature Review. Psicol. Teor. Prática 2018, 20, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwerier, E. Coping with Chronic Pain: Problem Solving and Acceptance; Universiteit Gent: Ghent, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan, B.; Condie, E.; Johnston, M. Using the Common Sense Self-Regulation Model to Determine Psychological Predictors of Prosthetic Use and Activity Limitations in Lower Limb Amputees. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2008, 32, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.G.; Krebs, M.J.S. Coping with Amputation. Sage J. Vasc. Surg. 1983, 17, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, D.S. Well-Being Following Amputation: Salutary Effects of Positive Meaning, Optimism, and Control. Rehabil. Psychol. 1996, 41, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.; Niven, C.A.; Knussen, C. The Role of Coping in Adjustment to Phantom Limb Pain. Pain 1995, 62, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Á.M.; Fyfe, N. A Comparison of the Effect of the Aesthetics of Digital Cosmetic Prostheses on Body Image and Well-Being. JPO J. Prosthet. Orthot. 2004, 16, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.P.; Mitchell, C.; Repayo, K.; Tillitt, M.; Weber, C.; Chien, L.C.; Doerger, C. Patient Engagement in Cosmetic Designing of Prostheses: Current Practice and Potential Outcome Benefits. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2022, 46, E335–E340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laferrier, J.Z.; Parente, M.; Felmlee, D. Return to Sport, Exercise, and Recreation (SER) Following Amputation. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2024, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, E.J.; Zbinden, J.; Munoz-Novoa, M.; Mastinu, E.; Smiles, A.; Ortiz-Catalan, M. Competitive Motivation Increased Home Use and Improved Prosthesis Self-Perception after Cybathlon 2020 for Neuromusculoskeletal Prosthesis User. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragaru, M.; Dekker, R.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Dijkstra, P.U. Amputees and Sports A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, N.A.; Abd Razak, N.A.; Abu Osman, N.A.; Gholizadeh, H. Improvement on Upper Limb Body-Powered Prostheses (1921–2016): A Systematic Review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 2018, 232, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendelken, S.; Page, D.M.; Davis, T.; Wark, H.A.C.; Kluger, D.T.; Duncan, C.; Warren, D.J.; Hutchinson, D.T.; Clark, G.A. Restoration of Motor Control and Proprioceptive and Cutaneous Sensation in Humans with Prior Upper-Limb Amputation via Multiple Utah Slanted Electrode Arrays (USEAs) Implanted in Residual Peripheral Arm Nerves. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwell, A.; Kenney, L.; Thies, S.; Head, J.; Galpin, A.; Baker, R. Addressing Unpredictability May Be the Key to Improving Performance with Current Clinically Prescribed Myoelectric Prostheses. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J. The Effect of Socket Movement and Electrode Contact on Myoelectric Prosthesis Control During Daily Living Activities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Salford, Salford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schone, H.R.; Udeozor, M.; Moninghoff, M.; Rispoli, B.; Vandersea, J.; Lock, B.; Hargrove, L.; Makin, T.R.; Baker, C.I. Biomimetic versus Arbitrary Motor Control Strategies for Bionic Hand Skill Learning. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 1108–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwell, A.; Prince, M.; Head, J.; Galpin, A.; Thies, S.; Kenney, L. Why Does My Prosthetic Hand Not Always Do What It Is Told? Front. Young Minds 2022, 10, 786663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuttaford, S.A.; Dyson, M.; Nazarpour, K.; Dupan, S.S.G. Reducing Motor Variability Enhances Myoelectric Control Robustness Across Untrained Limb Positions. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2024, 32, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesin, L.; Joubert, M.; Hanekom, T.; Merletti, R.; Farina, D. A Finite Element Model for Describing the Effect of Muscle Shortening on Surface EMG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 53, 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, S.; Tessier, A.; Arefi, M.; Zhang, A.; Williams, C.; Ameri, S.K. Reusable Free-Standing Hydrogel Electronic Tattoo Sensors with Superior Performance. Npj Flex. Electron. 2024, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.M.; Sudha, S.; Tarantino, S.; Esposti, R.; Bolzoni, F.; Cavallari, P.; Cipriani, C.; Mattoli, V.; Greco, F. Ultraconformable Temporary Tattoo Electrodes for Electrophysiology. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascia, A.; Collu, R.; Spanu, A.; Fraschini, M.; Barbaro, M.; Cosseddu, P. Wearable System Based on Ultra-Thin Parylene C Tattoo Electrodes for EEG Recording. Sensors 2023, 23, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascia, A.; Collu, R.; Makni, N.; Concas, M.; Barbaro, M.; Cosseddu, P. Impedance Characterization and Modeling of Gold, Silver, and PEDOT:PSS Ultra-Thin Tattoo Electrodes for Wearable Bioelectronics. Sensors 2025, 25, 4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonello, M.; Riccardo, C.; Roberto, P.; Andrea, D.; Francesca, C.; Loredana, Z.; Massimo, B.; Piero, C. Ultra-Conformable Tattoo Electrodes for Providing Sensory Feedback via Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, R.A. Super- and Ultrathin Organic Field-Effect Transistors: From Flexibility to Super- and Ultraflexibility. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1906908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, R.A.; Jin, H.; Lee, S.; Yokota, T.; Sekino, M.; Someya, T. Self-Adhesive and Ultra-Conformable, Sub-300 Nm Dry Thin-Film Electrodes for Surface Monitoring of Biopotentials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1803279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, G.; Maat, B.; Plettenburg, D.; Breedveld, P. A self-grasping hand prosthesis. In Proceedings of the Myoelectric Controls and Upper Limb, Prosthetics Symposium, Fredericton, NB, Canada, 15 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, L.; Montesano, E.; Chadwell, A.; Kenney, L.; Smit, G. Real-World Testing of the Self Grasping Hand, a Novel Adjustable Passive Prosthesis: A Single Group Pilot Study. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwell, A.; Chinn, N.; Kenney, L.; Karthaus, Z.J.; Mos, D.; Smit, G. An Evaluation of Contralateral Hand Involvement in the Operation of the Delft Self-Grasping Hand, an Adjustable Passive Prosthesis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plettenburg, D.H. Basic Requirements For Upper Extremity Prostheses: The Wilmer Approach. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Biomedical Engineering Towards the Year 2000 and Beyond. (Cat. No.98CH36286), Hong Kong, China, 1 November 1998; Volume 20, pp. 2276–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraja, V.H.; Moulic, S.G.; D’Souza, J.V.; Limesh, M.; Walters, P.; Bergmann, J.H.M. A Novel Respiratory Control and Actuation System for Upper-Limb Prosthesis Users: Clinical Evaluation Study. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 128764–128778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, V.H.; da Ponte Lopes, J.; Bergmann, J.H.M. Reimagining Prosthetic Control: A Novel Body-Powered Prosthetic System for Simultaneous Control and Actuation. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Asbrock, F. Disabled or Cyborg? How Bionics Affect Stereotypes toward People with Physical Disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schofield, J.S.; Shell, C.E.; Beckler, D.T.; Thumser, Z.C.; Marasco, P.D. Long-Term Home-Use of Sensory-Motor-Integrated Bidirectional Bionic Prosthetic Arms Promotes Functional, Perceptual, and Cognitive Changes. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tereshenko, V.; Giorgino, R.; Eberlin, K.R.; Valerio, I.L.; Souza, J.M.; Alessandri-Bonetti, M.; Peretti, G.M.; Aszmann, O.C. Emerging Value of Osseointegration for Intuitive Prosthetic Control after Transhumeral Amputations: A Systematic Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, E5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.W.; Schiefer, M.A.; Keith, M.W.; Anderson, J.R.; Tyler, D.J. Stability and Selectivity of a Chronic, Multi-Contact Cuff Electrode for Sensory Stimulation in Human Amputees. J. Neural Eng. 2015, 12, 026002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, S.R.; Lambrecht, J.M.; Dsouza, K.T.; Dunning, J.L.; Anderson, J.R.; Malone, K.J.; Chepla, K.J.; Graczyk, E.L.; Tyler, D.J. First-in-Human Implementation of a Bidirectional Somatosensory Neuroprosthetic System with Wireless Communication. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2025, 22, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, E.; Cerqueira, R.; Preziuso, C.; Angelini, L.; Guachi, R.; Controzzi, M.; Cipriani, C.; Mastinu, E. LimbMATE: A Versatile Platform for Closed-Loop Research in Prosthetics. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2025, 33, 2112–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, R.; Collu, R.; Tullio, L.; Demofonti, A.; Scarpelli, A.; Cordella, F.; Barbaro, M.; Zollo, L. Wearable Stimulator for Upper and Lower Limb Somatotopic Sensory Feedback Restoration. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collu, R.; Paolini, R.; Bilotta, M.; Demofonti, A.; Cordella, F.; Zollo, L.; Barbaro, M. Wearable High Voltage Compliant Current Stimulator for Restoring Sensory Feedback. Micromachines 2023, 14, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graczyk, E.; Hutchison, B.; Valle, G.; Bjanes, D.; Gates, D.; Raspopovic, S.; Gaunt, R. Clinical Applications and Future Translation of Somatosensory Neuroprostheses. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e1237242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.D.; Fox, J. Body Image and Prosthesis Satisfaction in the Lower Limb Amputee. Disabil. Rehabil. 2002, 24, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimsek, N.; Öztürk, G.K.; Nahya, Z.N. The Mental Health of Individuals with Post-Traumatic Lower Limb Amputation: A Qualitative Study. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffalitzky, E.; Gallagher, P.; MacLachlan, M.; Wegener, S.T. Developing Consensus on Important Factors Associated with Lower Limb Prosthetic Prescription and Use. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaulding, S.E.; Yamane, A.; McDonald, C.L.; Spaulding, S.A. A Conceptual Framework for Orthotic and Prosthetic Education. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2019, 43, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaulding, S.E.; Kheng, S.; Kapp, S.; Harte, C. Education in Prosthetic and Orthotic Training: Looking Back 50 Years and Moving Forward. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2020, 44, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunaurd, I.; Spaulding, S.E.; Amtmann, D.; Salem, R.; Gailey, R.; Morgan, S.J.; Hafner, B.J. Use of and Confidence in Administering Outcome Measures among Clinical Prosthetists: Results from a National Survey and Mixed-Methods Training Program. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2015, 39, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.; Parker, D.; Williams, A. An Exploratory Qualitative Study of Health Professional Perspectives on Clinical Outcomes in UK Orthotic Practice. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2020, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.J.; Rowe, K.; Fitting, C.C.; Gaunaurd, I.A.; Kristal, A.; Balkman, G.S.; Salem, R.; Bamer, A.M.; Hafner, B.J. Use of Standardized Outcome Measures for People With Lower Limb Amputation: A Survey of Prosthetic Practitioners in the United States. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1786–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostler, C.; Dickinson, A.; Metcalf, C.; Donovan-Hall, M. Exploring the Patient Experience and Perspectives of Taking Part in Outcome Measurement during Lower Limb Prosthetic Rehabilitation: A Qualitative Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 5640–5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Fatone, S. You’ve Heard about Outcome Measures, so How Do You Use Them? Integrating Clinically Relevant Outcome Measures in Orthotic Management of Stroke. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2013, 37, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, F.; Pichette, M.; Swaine, B.; Auger, C.; Zidarov, D. Consensus-Based Recommendations for Comprehensive Clinical Assessment in Prosthetic Care: A Delphi Study. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwell, A.; Kenney, L.; Granat, M.; Thies, S.; Head, J.S.; Galpin, A. Visualisation of Upper Limb Activity Using Spirals: A New Approach to the Assessment of Daily Prosthesis Usage. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2018, 42, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Date | Country of Study | Main Aim of the Study | Data Collection | Participant Demographics | Type of Prosthetic Device | Critical Issues and Reasons for Abandonment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kejlaa [98] (1993) | Denmark | To assess users’ concerns about their prostheses and whether these have contributed to prosthesis abandonment | Cross-sectional survey study | 66 Subjects (Mean age 45.1 yr. Range 4–86 yr.) | Passive Body-powered Myoelectric | -Skin irritation -Damaged clothing -Not durable -Aesthetics -Difficult to use -Slow response time -Difficult to control -Prosthetic device failure -Weight -Temperature |

| Silcox et al. [99] (1993) | USA | To examine the acceptance and use of prosthetics by those who own both myoelectric and other types of prosthetics | Cross-sectional survey study | 44 Subjects (Mean age 38 yr. Range 6–69 yr.) | Myoelectric | -Weight -Slow to respond and use -Durability -Discomfort |

| Wright et al. [26] (1995) | USA | To evaluate patterns of upper limb prosthesis use | Medical record review and cross-sectional survey study | 135 Subjects (Mean age 36 yr. Range 2–76 yr.) | Unspecified | -Limited functional benefit -Weight -Socket Discomfort |

| Atkins [100] (1996) | USA | Users’ perceptions of devices in terms of cost, maintenance and improvements in body-powered and electric devices | Multiple surveys (postal) | 1575 Subjects (Mean age 45 yr. 890 Adults, 685 < 18 yr.) | Body-powered Electric | -Wrist motion -Increased reliance on visual attention -Harness comfort -Durability -Reliability |

| Biddis et al. [72] (2007) | Canada | To measure user’s satisfaction with upper limb prosthesis | Cross-sectional study | 242 Subjects (Mean age 30 yr. Range 1–80 yr. from Different Countries) | Passive Body-powered Myoelectric | -Temperature -Perspiration -Durability -Harness comfort -Lack of sensory feedback -Poor dexterity -Weight -Perspiration |

| Biddiss and Chau [96] (2007) | Canada | To investigate the needs and resources required that lead to the use and/or abandonment of prostheses. | Cross-sectional survey study | 242 Subjects (Mean age 30 yr. Range 1–80 yr. from Different Countries) | Unspecified | -Personal factors -Discomfort -Weight -Temperature -Perspiration -Lack of sensory feedback -Dissatisfaction with technology -Lack of functionality |

| Biddiss and Chau [25] (2007) | Canada | Review of upper limb prosthesis use and abandonment | Literature review | Literature review (1–80 yr. from Different Countries) | Unspecified | -Lack of established need given their lifestyle -Lack of information, training and follow-up -Personal factors |

| McFarland et al. [71] (2010) | USA | To investigate prosthetic use and satisfaction in veterans with unilateral upper limb loss | Cross-sectional survey study | 97 Veterans from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts (Mean age 45 yr.) | Passive Body-powered Myoelectric | -Lack of functionality -Weight -Pain -Poor fit -Durability -Difficult to control -Discomfort |

| Østlie et al. [101] (2012) | Norway | To estimate prosthesis rejection rates and describe the most frequent causes, as well as the contextual factors influencing prosthetic rejection. | Cross-sectional survey study | 224 Subjects (Mean age 53.7 yr.) | Myoelectric Unspecified | -Weight -Socket fit -Perspiration -Skin irritation -Functionality -Weak grip -Wrist motion -Slow response speed -Difficult to use -Mismatch between needs and available technology -Insufficient training and information |

| Carey at al. [35] (2017) | USA | Review to determine the differences between myoelectric and body-powered prostheses, to inform clinical practice in user training. | Literature review | Adults, Mean age 43.3 yr. Different Countries and population | Body-powered Myoelectric | -Slower movement -Poor grasp force -Increased mass and energy expense for operation -Temperature, -Durability -Reliability -Increased reliance on visual attention -Lack of functionality -Weight -Discomfort |

| Resnik et al. [16] (2019) | USA | To provide data on the function, needs, preferences, and satisfaction of veterans with upper limb amputations | Cross-sectional survey study | 808 War Veterans (Mean age 63.3 yr.) | Body-powered Hybrid Myoelectric | -Weight -General discomfort -Poor fit -Lack of functionality -Difficult to use -Durability -Aesthetics |

| Al-Owaidi et al. [102] (2024) | Spain | To highlight control issues related to myoelectric prosthetic hands. | Cross-sectional survey study | Literature review Age Not Specified | Myoelectric | -Dissatisfaction with technology -Socket discomfort and skin irritation -Cost -Lack of information, training and follow-up -Lack of psychological support |

| Resnik et al. [103] (2024) | USA | Compare rates of out-of-pocket prosthesis-related payments and evaluate the impact of affordability on prosthesis non-use. | Telephone survey | 727 Subjects; 76% Veterans and 24% non-Veterans | Unspecified | -Excessive cost of the device and its maintenance |

| Henao et al. [47] (2025) | USA | To define the design requirements of prosthetics from the perspective of healthcare professionals, end-users and close relatives | Semi structured interviews | 11 healthcare providers 10 users with unilateral upper limb amputation 10 close relatives (Adults > 20 yr.) | Unspecified | -Dissatisfaction with technology -Lack of information, training and follow-up |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Collu, R.; Ferrazzano, E.; Murgia, V.; Salis, C.; Barbaro, M. The Technological and Psychological Aspects of Upper Limb Prostheses Abandonment: A Narrative Review. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060167

Collu R, Ferrazzano E, Murgia V, Salis C, Barbaro M. The Technological and Psychological Aspects of Upper Limb Prostheses Abandonment: A Narrative Review. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(6):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060167

Chicago/Turabian StyleCollu, Riccardo, Elena Ferrazzano, Verdiana Murgia, Cinzia Salis, and Massimo Barbaro. 2025. "The Technological and Psychological Aspects of Upper Limb Prostheses Abandonment: A Narrative Review" Prosthesis 7, no. 6: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060167

APA StyleCollu, R., Ferrazzano, E., Murgia, V., Salis, C., & Barbaro, M. (2025). The Technological and Psychological Aspects of Upper Limb Prostheses Abandonment: A Narrative Review. Prosthesis, 7(6), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060167