A Scoping Review of Advances in Active Below-Knee Prosthetics: Integrating Biomechanical Design, Energy Efficiency, and Neuromuscular Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Mechanical outcomes—joint kinematics, joint kinetics, centre of mass behaviour, and mechanical power generation or absorption;

- Energetic outcomes—metabolic cost, mechanical work, and walking efficiency;

- Neuromuscular outcomes—electromyographic activity, muscle coordination patterns, and compensatory control strategies.

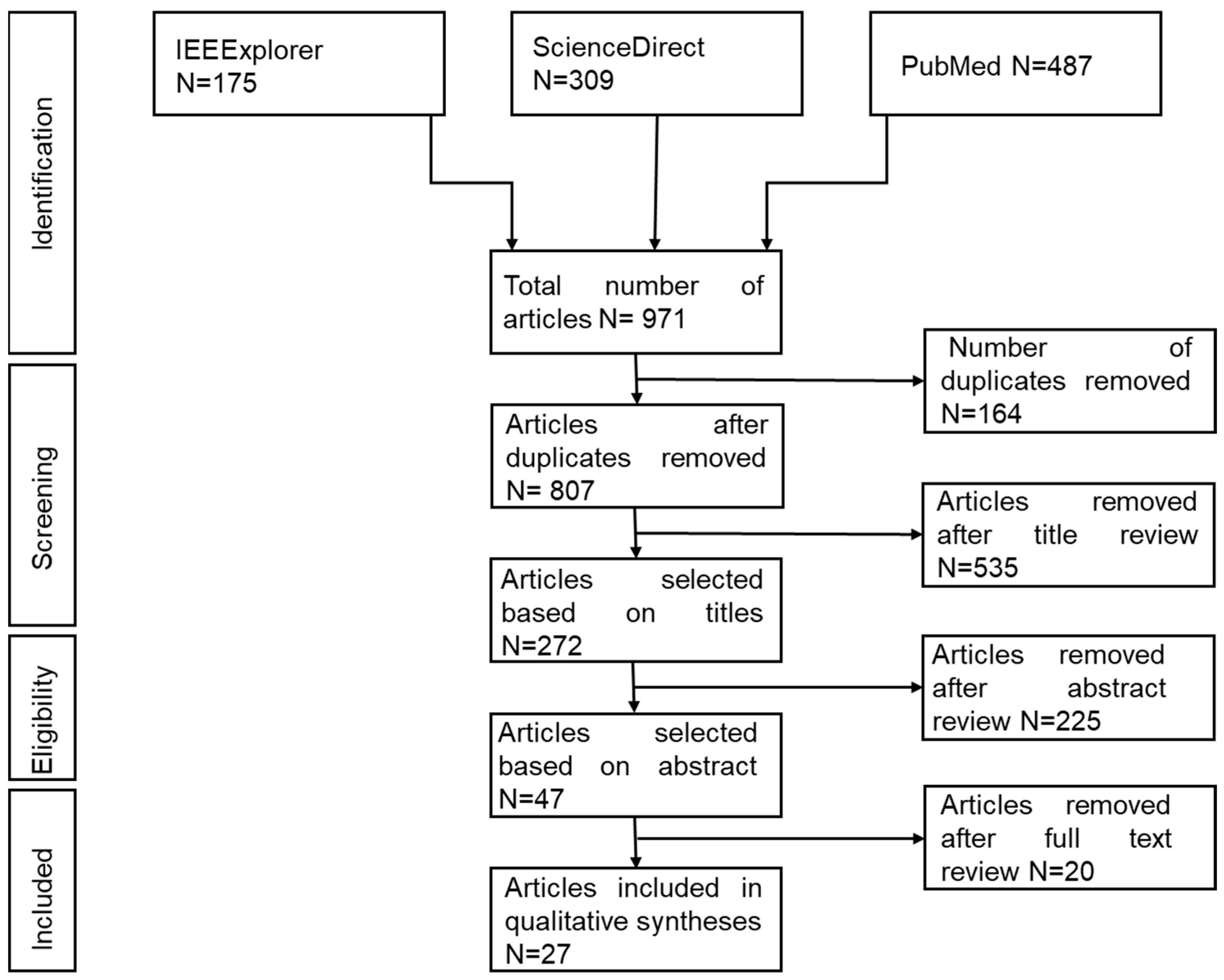

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

- PubMed: (Active OR Powered OR bionic) AND Prosthe* AND (ankle OR foot);

- Sciencedirect: “Powered” AND (Prostheses OR Prosthesis OR Prosthetic) AND (Ankle OR Foot) AND “Below knee”;

- IEEExplorer: (“transtibial amputee*” OR “below-knee amputee*” OR “lower limb amputation”) AND (“active prosthe*” OR “powered ankle–foot” OR “bionic prosthesis”).

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies involving human participants with unilateral transtibial amputation.

- Investigations examining active, semi-active, or powered ankle–foot prostheses.

- Experimental studies evaluating gait biomechanics, energy cost of walking, or muscle activity.

- Research conducted on level ground walking at self-selected or controlled speeds.

- Studies focusing exclusively on passive or energy-storing and returning prostheses without actuation.

- Research involving transfemoral or through-knee amputations.

- Participants with pre-existing osteoarthritis or other lower-limb pathologies affecting gait.

- Studies analysing gait on stairs or uneven terrain where confounding biomechanical factors are introduced.

2.4. Data Charting

2.5. Screening and Selection Process

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics and Experimental Context

3.2. Gait Kinematics

3.3. Gait Kinetics

3.4. Energy Expenditure

3.5. Muscle Activation and Neuromuscular Adaptation

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Key Findings

4.2. Integration of Biomechanical Theory

4.3. Design Innovations and Mechanical Control

4.4. Neuromuscular and Energetic Implications

4.5. Clinical and Translational Implications

- Variations in residual limb length, muscle strength, and balance necessitate custom calibration of prosthetic stiffness and torque output.

- Effective integration of powered devices requires prolonged acclimation and guided physiotherapy to promote neuromuscular adaptation.

- Future designs should account for real-world terrains and activities, ensuring robustness across uneven and compliant surfaces.

- Addressing the significant underrepresentation of female participants is essential for developing gender-responsive prosthetic systems that account for anatomical and biomechanical differences.

4.6. Limitations of Current Research

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications for Prosthetic Design

5.2. Clinical and Rehabilitation Perspectives

5.3. Research Priorities and Methodological Recommendations

- Most current evidence is derived from short-term laboratory trials; long-term studies are needed to capture adaptation trajectories, fatigue effects, and sustained biomechanical changes.

- Future trials should recruit representative populations, including adequate female participation, older adults, and users from low-resource settings, to enhance external validity.

- Adoption of unified biomechanical metrics, such as joint power normalisation, symmetry indices, and metabolic cost per stride, will facilitate cross-study comparisons and meta-analytical synthesis.

- Combining EMG, motion capture, and metabolic data can provide a holistic understanding of how mechanical and neural factors co-adapt during powered prosthesis use.

- Effective innovation requires cooperation between biomedical engineers, physiotherapists, and clinicians to ensure that technological development aligns with user needs and clinical feasibility.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AK | Above Knee |

| BKA | Below-Knee Amputation |

| COM | Centre of Mass |

| COT | Cost of Transport |

| DIC | Digital Image Correlation |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| ESAR | Energy Storage and Return (foot) |

| GRF | Ground Reaction Force |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| KE | Kinetic Energy |

| KI | Kinetic Index |

| K | Kinematics |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses–Scoping Review Extension |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

| VIA | Variable Impedance Actuator |

Appendix A. Study Groupings

| Study (Reference) | Participants (TTA) | Key Intervention/Prosthesis Type | Primary Outcome Focus | Key Findings Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2 | Lightweight Polycentric (Powered) | Biomechanics & Design | Torque profile resembled biological ankle; design may reduce electrical energy use. |

| [2] | 10 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Gait Kinetics | Enhanced ankle power, trailing limb work, and step symmetry vs. passive foot. |

| [3] | 6 | AMPfoot 4.0 (Powered Prototype) | Gait Kinematics | Improved lower-limb kinematics but increased compensatory trunk movement. |

| [4] | 1 | Pneumatic Actuation (Prototype) | Biomechanics & Comfort | Prototype generated sufficient torque and was perceived as more natural and comfortable. |

| [6] | 10 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Joint Kinetics | Reduced sound-limb ground reaction forces and knee flexion moment at faster speeds. |

| [7] | 12 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Energy Expenditure | No significant group-level metabolic cost difference; high individual variability. |

| [10] | 15 | Ossur Variflex (ESAR) | Biomechanics & Muscle Activity | Increased trunk/pelvic motion, sound-limb loading, and muscle co-contraction. |

| [12] | 5 | Ottobock Empower (Powered) | Gait Kinetics | Increased prosthetic ankle work did not reduce collision work on the intact limb. |

| [13] | 10 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Muscle Activity & Metabolism | Increased gluteus medius and vastus medialis activity with powered use; variable metabolic cost changes. |

| [15] | 2 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Gait Kinetics | Reduced the kinetic burden placed on the leading intact leg. |

| [18] | 1 | Walk-Run Ankle (Powered) | Gait Kinematics & Symmetry | Powered mode improved ankle ROM, power, and gait symmetry vs. passive mode. |

| [19] | 3 | Hybrid EMG Control (Powered) | Sensorimotor Learning | Amputees could scale push-off with EMG but showed reduced adaptation vs. controls. |

| [20] | 10 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Energy Expenditure | Amputees may need ankle work above biological normal to reduce metabolic cost. |

| [21] | 10 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Energy Expenditure | No significant group-level change in metabolic cost or preferred walking speed. |

| [22] | 6 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Energy Expenditure & Work | 16% lower metabolic rate and 63% greater trailing limb work vs. passive foot. |

| [23] | 45 | Proprio-foot® (MPA) | Energy Expenditure & Balance | No statistical difference in VO2; significant improvement in balance and quality of life scores. |

| [24] | 8 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Whole-Body Dynamics | Powered prosthesis increased trunk angular momentum, potentially aiding performance. |

| [25] | 1 | PANTOE II (Ankle+Toe) | Design & Energy Use | Toe joint consumed half the energy of previous model; improved comfort. |

| [26] | 5 | Myoelectric Control (Prototype) | Muscle Control & Ankle Power | Real-time visual feedback of EMG signals enabled users to increase ankle power. |

| [27] | 1 | Active Alignment (Prototype) | Socket Interface & Gait | Reduced socket pressure (>10%) and improved gait symmetry via active alignment. |

| [28] | 6 | Tethered Emulator Systems | Energy Expenditure | No link found between prosthetic push-off work and user’s metabolic rate. |

| [29] | 1 | Myoelectric Control (Prototype) | Control Systems | Feasible to use residual muscle signals for proportional control of walking. |

| [30] | 7 | Adaptive Ankle (Semi-active) | User Interface & Comfort | Users could identify and select their preferred prosthetic ankle stiffness. |

| [31] | 8 | BiOM T2 Ankle (Powered) | Whole-Body Dynamics | Reduced sagittal-plane angular momentum range at certain speeds vs. passive foot. |

| [34] | 1 | Vanderbilt Ankle (Powered) | Biomechanics | Reproduced biological ankle angle, torque, and power profiles across speeds. |

| [35] | 1 | Custom Powered (Spring) | Technical Performance | Prosthesis torque was close to required biological torque. |

| [37] | 6 | AMP-Foot 4.0 (Quasi-passive) | User Satisfaction | Higher perceived exertion, but users recognized the technology’s value. |

References

- Gabert, L.; Hood, S.; Tran, M.; Cempini, M.; Lenzi, T. A compact, lightweight robotic ankle-foot prosthesis: Featuring a powered polycentric design. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2020, 27, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.J.; Pruziner, A.L.D. Use of a Powered Versus a Passive Prosthetic System for a Person with Bilateral Amputations during Level-Ground Walking. 2014. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/jpojournal (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- De Pauw, K.; Serrien, B.; Baeyens, J.-P.; Cherelle, P.; De Bock, S.; Ghillebert, J.; Bailey, S.P.; Lefeber, D.; Roelands, B.; Vanderborght, B.; et al. Prosthetic gait of unilateral lower-limb amputees with current and novel prostheses: A pilot study. Clin. Biomech. 2020, 71, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Shen, X. Design and control of a pneumatically actuated transtibial prosthesis. J. Bionic Eng. 2015, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sup, F.; Bohara, A.; Goldfarb, M. Design and Control of a Powered Knee and Ankle Prosthesis. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Roma, Italy, 10–14 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, E.R.; Wilken, J.M. Biomechanical risk factors for knee osteoarthritis when using passive and powered ankle-foot prostheses. Clin. Biomech. 2014, 29, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Wensman, J.; Colabianchi, N.; Gates, D.H. The influence of powered prostheses on user perspectives, metabolics, and activity: A randomized crossover trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, P.G.; Kuo, A.D. Mechanisms of gait asymmetry due to push-off deficiency in unilateral amputees. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2015, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norvell, D.C.; Czerniecki, J.M.; Reiber, G.E.; Maynard, C.; Pecoraro, J.A.; Weiss, N.S. The prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis among veteran traumatic amputees and nonamputees. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marchis, C.; Ranaldi, S.; Varrecchia, T.; Serrao, M.; Castiglia, S.F.; Tatarelli, A.; Ranavolo, A.; Draicchio, F.; Lacquaniti, F.; Conforto, S. Characterizing the Gait of People With Different Types of Amputation and Prosthetic Components Through Multimodal Measurements: A Methodological Perspective. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, L.; McGuigan, M.P.; McKay, C.; Bilzon, J.; Seminati, E. Biomechanical risk factors for knee osteoarthritis and lower back pain in lower limb amputees: Protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.M.; Childers, W.L.; Chang, Y.-H. Altering the tuning parameter settings of a commercial powered prosthetic foot to increase power during push-off may not reduce collisional work in the intact limb during gait. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2021, 45, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Gardinier, E.S.; Vempala, V.; Gates, D.H. The effect of powered ankle prostheses on muscle activity during walking. J. Biomech. 2021, 124, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyf, P.A.; van Heugten, C.M.; Hitters, M.W.; Smeets, R.J. The Prevalence of Osteoarthritis of the Intact Hip and Knee Among Traumatic Leg Amputees. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.; Herr, H. Effects of a Powered Ankle-Foot Prosthesis on Kinetic Loading of the Contralateral Limb: A Case Series. 2015. Available online: https://www.ossur.com (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Winter, D.A.; Sienko, S.E. Biomechanics of Below-Knee Amputee Gait. J. Biomech. 1988, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Holgate, M.; Holgate, R.; Boehler, A.; Ward, J.; Hollander, K.; Sugar, T.; Seyfarth, A. A powered prosthetic ankle joint for walking and running. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Kannape, O.A.; Herr, H.M. Proportional EMG Control of Ankle Plantar Flexion in a Powered Transtibial Prosthesis. 2013. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24187210/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Ingraham, K.A.; Choi, H.; Gardinier, E.S.; Remy, C.D.; Gates, D.H. Choosing appropriate prosthetic ankle work to reduce the metabolic cost of individuals with transtibial amputation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardinier, E.S.; Kelly, B.M.; Wensman, J.; Gates, D.H. A controlled clinical trial of a clinically-tuned powered ankle prosthesis in people with transtibial amputation. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, E.R.; Whitehead, J.M.A.; Wilken, J.M. Step-to-step transition work during level and inclined walking using passive and powered ankle-foot prostheses. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2016, 40, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colas-Ribas, C.; Martinet, N.; Audat, G.; Bruneau, A.; Paysant, J.; Abraham, P. Effects of a microprocessor-controlled ankle-foot unit on energy expenditure, quality of life, and postural stability in persons with transtibial amputation: An unblinded, randomized, controlled, cross-over study. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2022, 46, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickle, N.T.; Silverman, A.K.; Wilken, J.M.; Fey, N.P. Statistical analysis of timeseries data reveals changes in 3D segmental coordination of balance in response to prosthetic ankle power on ramps. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; She, T.; Huang, Q. PANTOE II: Improved Version of a Powered Transtibial Prosthesis with Ankle and toe Joints. 2018. Available online: http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/BIOMED/proceedings-pdf/DMD2018/40789/V001T03A015/2788197/v001t03a015-dmd2018-6942.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Huang, S.; Wensman, J.P.; Ferris, D.P. Locomotor Adaptation by Transtibial Amputees Walking with an Experimental Powered Prosthesis under Continuous Myoelectric Control. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2016, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPrè, A.K.; Umberger, B.R.; Sup, F.C. A Robotic Ankle–Foot Prosthesis With Active Alignment. J. Med. Device 2016, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, R.E.; Caputo, J.M.; Collins, S.H. Increasing ankle push-off work with a powered prosthesis does not necessarily reduce metabolic rate for transtibial amputees. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wensman, J.P.; Ferris, D.P. An experimental powered lower limb prosthesis using proportional myoelectric control. J. Med. Devices Trans. ASME 2014, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clites, T.R.; Shepherd, M.K.; Ingraham, K.A.; Wontorcik, L.; Rouse, E.J. Understanding patient preference in prosthetic ankle stiffness. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowski, A.M.; D’andrea, S. Effects of a powered ankle-foot prosthesis on kinetic loading of the unaffected leg during level-ground walking. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2013, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papegaaij, S.; Steenbrink, F. Clinical Gait Analysis: Treadmill-Based vs Overground; Motek Medical: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Semaan, M.B.; Wallard, L.; Ruiz, V.; Gillet, C.; Leteneur, S.; Simoneau-Buessinger, E. Is treadmill walking biomechanically comparable to overground walking? A systematic review. Gait Posture 2022, 92, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shultz, A.H.; Mitchell, J.E.; Truex, D.; Lawson, B.E.; Ledoux, E.; Goldfarb, M. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–30 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Liu, Y.; Liao, W.-H. A new powered ankle-foot prosthesis with compact parallel spring mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics, ROBIO 2016, Qingdao, China, 3–7 December 2016; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sup, F. 2nd IEEE RAS and EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics; IEEE: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw, K.; Cherelle, P.; Roelands, B.; Lefeber, D.; Meeusen, R. The efficacy of the Ankle Mimicking Prosthetic Foot prototype 4.0 during walking: Physiological determinants. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2018, 42, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windrich, M.; Grimmer, M.; Christ, O.; Rinderknecht, S.; Beckerle, P. Active lower limb prosthetics: A systematic review of design issues and solutions. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, S.K.; Weber, J.; Herr, H. Powered ankle-foot prosthesis improves walking metabolic economy. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, J.D.; Klute, G.K.; Neptune, R.R. The effect of prosthetic ankle energy storage and return properties on muscle activity in below-knee amputee walking. Gait Posture 2011, 33, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Amputee Rehabilitation. Evidence Based Clinical Guidelines for the Physiotherapy Management of Adults with Lower Limb Prostheses. 2020. Available online: https://www.bacpar.org/Data/Resource_Downloads/2020bacparprostheticguidelinesprocessdoc.pdf?date=27/11/2023%2010:54:17 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Demirdel, S.; Yılmaz, R.; Küçük, S.; Söyler, O. The association between cognitive function and physical performance in established users of a lower limb prosthesis. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 194, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, R.; D’aMico, S.; Caramma, S.; Grasso, G.; Pirrone, S.; Ronsisvalle, M.G.; Bonfiglio, M. The Effectiveness of Goal-Oriented Dual Task Proprioceptive Training in Subacute Stroke: A Retrospective Observational Study. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 48, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, A.M.; Fey, N.P.; Ingraham, K.A.; Young, A.J.; Hargrove, L.J. Powered prosthesis control during walking, sitting, standing, and non-weight bearing activities using neural and mechanical inputs. In Proceedings of the 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), San Diego, CA, USA, 6–8 November 2013; pp. 1174–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, E.; Beauchamp, M.K.; Wilson, J.A. Age and sex differences in normative gait patterns. Gait Posture 2021, 88, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eidmann, A.; Kamawal, Y.; Luedemann, M.; Raab, P.; Rudert, M.; Stratos, I. Demographics and Etiology for Lower Extremity Amputations—Experiences of an University Orthopaedic Center in Germany. Medicina 2023, 59, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population | Intervention | Biological Comparator | Prosthetic Comparator | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People with transtibial amputation | Actuated below-knee prostheses | Sound limb | Energy-storage-and-return foot | Gait pattern |

| Individuals with lower-limb loss | Active prosthetic systems | Non-amputee controls | Passive prosthetic foot | Walking pattern |

| Transtibial prosthesis users | Powered prostheses | Typical gait | Solid Ankle Cushion Heel (SACH) | Ambulation |

| Persons with transtibial limb loss | Bionic prosthetic devices | Normal limb function | — | Walking behaviour |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Godlimpi, Z.; Pandelani, T. A Scoping Review of Advances in Active Below-Knee Prosthetics: Integrating Biomechanical Design, Energy Efficiency, and Neuromuscular Adaptation. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060165

Godlimpi Z, Pandelani T. A Scoping Review of Advances in Active Below-Knee Prosthetics: Integrating Biomechanical Design, Energy Efficiency, and Neuromuscular Adaptation. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(6):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060165

Chicago/Turabian StyleGodlimpi, Zanodumo, and Thanyani Pandelani. 2025. "A Scoping Review of Advances in Active Below-Knee Prosthetics: Integrating Biomechanical Design, Energy Efficiency, and Neuromuscular Adaptation" Prosthesis 7, no. 6: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060165

APA StyleGodlimpi, Z., & Pandelani, T. (2025). A Scoping Review of Advances in Active Below-Knee Prosthetics: Integrating Biomechanical Design, Energy Efficiency, and Neuromuscular Adaptation. Prosthesis, 7(6), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060165