Abstract

Traditional low-cost DC drives, such as Buck converter-fed DC drives, do not take into consideration the power quality requirements regarding the total harmonic distortion (THD) and the input power factor (PF). This paper proposes a high-performance one-quadrant DC drive based on the ultra-sparse matrix rectifier (USMR). The scheme is suitable for single-quadrant applications such as DC pumping systems. The proposed system leverages the advantages of the USMR, such as the accomplishment of the IEEE standards requirements related to harmonic limits and distortions of the AC currents and operation at (or near) unity PF. Two pulse width modulation (PWM) techniques were investigated: the hysteresis current controller with a tolerance band and the triangular carrier-based PWM modulator. The system was studied under different operating conditions. The obtained results demonstrate the high performance of the USMR system with both types of PWM techniques. A comparative study with the one-quadrant Buck converter-based DC drive was conducted. The USMR-based DC drive outperforms the conventional scheme in power quality issues. The quantitative assessment proves the validity and suitability of the USMR for developing high-performance DC drives for single-quadrant applications.

1. Introduction

DC drives have been used in a wide range of applications for a long time [1], exceeding four decades, due to their precise control and excellent dynamic performance [2]. Although AC drives, especially induction motor drives, are replacing DC drives in modern industrial applications [3], DC drives still have considerable importance and are preferred and widely used in many applications such as conveyors, robotics, servo systems, CNC machines, and pumping systems [4,5,6]. Recently, extensive efforts and intensive studies have been carried out to improve the performance of DC drives [1,2,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

The authors in [1] proposed an adaptive speed control method for DC motors based on inverse optimal control. The technique integrated integral action and a disturbance observer for real-time load torque estimation, ensuring stability and robustness and demonstrating superior performance compared to conventional cascaded PI controllers. Ref. [2] presents a non-linear PI controller scheme where a nonlinear exponential PI controller is introduced for DC motor drives, whose control achieved fast speed tracking and satisfactory load disturbance rejection compared with a conventional controller. In [5], a sliding mode control is employed to control the speed of a DC motor. The sliding mode controller ensures robustness against parameter variations and disturbances. Simulation results show superior transient response, reduced overshoot, and improved stability. Moreover, ref. [6] introduced an adaptive backstepping integral sliding mode controller that enhanced robustness and reduced the settling time of the DC motor under parametric uncertainties and load disturbances. The authors in ref. [7] employed the dandelion optimization technique to tune the parameters of the PID controller utilized in the speed control of a DC motor drive for EV applications. The method yielded the lowest errors and demonstrated superior disturbance rejection compared with other evolutionary search algorithms. Ref. [8] investigated a fuzzy self-tuning PID controller for speed regulation of a DC motor drive. The tuning and dynamic adjustment of the PID’s gains improved system robustness against parameter variations and external disturbances. Enhanced transient response and reduced overshoot were achieved. The authors in [9] proposed a robust control strategy for a multi-in-multi-out DC motor system. The method combined PI loops with a sliding mode controller, ensuring resilience against disturbances and parameter uncertainties.

In [10], an advanced DC motor drive using a multilevel DC–DC buck converter is presented. The proposed system enhances voltage regulation, reduces current ripple, and improves efficiency compared with conventional single-level converters. The results demonstrate the superior dynamic performance of the proposed DC drive scheme. Ref. [11] investigated the nonlinear speed control of a DC motor drive. A feedback linearizing controller was optimized using the gray wolf algorithm. Stability and robustness under disturbances were analyzed. The experimental validation indicated the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed control system. Ref. [12] presents a comprehensive identification and linear control of DC motors. It includes experimental measurements and system identification, where parameters are extracted and validated. Moreover, the controllers are implemented on an Arduino microcontroller. A novel multilevel DC–DC buck converter topology for DC motor drives is proposed in [13]. The presented scheme aims to reduce torque and current ripples, mechanical vibrations, and acoustic noise caused by traditional DC–DC converters. The results verify the enhanced performance of the DC motor drive with the proposed DC–DC converter topology. Recently, the authors in [14] proposed an Internet-distributed energy management strategy for connected plug-in hybrid EVs. A top-layer cloud module predicted future driving conditions; a bottom-layer vehicle-side module executed real-time optimization. The scheme provides near-global optimization of the fuel-electric power allocation for real-time EV operation. In addition, Ref. [15] presents a novel Multi-U-Style micro-channel design for battery liquid-cooling plates that matches coolant flow distribution to non-uniform battery heat generation. The proposed scheme enhances temperature uniformity and improves the overall thermal management performance for high-power battery systems that can be employed in EVs.

On the other hand, old-fashioned industrial DC drives were based on AC–DC phase-controlled rectifiers, which resulted in poor power quality and injected undesired low-order harmonics into the electric grid. Recently, poor power quality and harmonic restrictions have not been allowed with the new harmonic standards [16,17,18]. Thus, the obsolete phase-controlled rectifiers can exist in some industrial DC drives for high ratings, provided that modern active power filters or well-designed passive filters are employed to improve the power quality to meet the related standards [16,17,18], which increases the overall cost of the DC drive. Even the modern DC drives that are based on the well-known buck converter, or full bridge converter, assume ideal DC sources [1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. When they are fed from the AC grid through single-phase or three-phase uncontrolled rectifiers (diode bridge) to form the DC link side, they also deteriorate the power quality in terms of high total harmonic distortion of the input currents, have a low-input power factor (PF), draw pulse currents due to the parallel connected DC capacitors (which are utilized to smooth the DC link voltage), and inject undesired low-order harmonics into the grid.

One of the effective solutions is to utilize three-phase PWM rectifiers [19,20,21,22,23,24,25] to regulate the DC link voltage and control the current drawn from the AC grid to be near sinusoidal with low total harmonic distortion [25,26,27,28]. With PWM rectifiers, the input PF can be adjusted to the desired value, which in most cases has the unity value. Since the three-phase PWM rectifier operates at a high DC link voltage, it cannot control the operation of the DC motor for the entire speed range. Consequently, an additional DC buck chopper is required to adjust the DC voltage feeding the motor for the entire speed range, which increases the overall cost of the DC drive.

Recently, a few research efforts [29,30,31,32] have introduced the ultra-sparse matrix rectifier (USMR) topology to provide a high-performance unidirectional AC–DC rectifier with improved power quality in terms of operation near unity PF and limited total harmonic distortion of the input currents. In [29], the authors presented a unity PF battery charger system using the USMR involving fuzzy logic control. The obtained experimental results demonstrated a successful battery charging profile during the constant current charging phase and the constant voltage charging phase. Moreover, ref. [30] introduced a battery charger system using USMR topology, including maximum power point tracking (MPPT), for a wind turbine. The experimental results indicated the effectiveness of the USMR to develop an economic battery charging system while maintaining unity PF operation. Also, the authors of [31] employed the USMR scheme for battery charging under constant-current/constant-voltage schemes. The obtained simulation results demonstrated the capability of the USMR to control the charging current and voltage to the set points; meanwhile, the input current was near sinusoidal. In [32], the model predictive control (MPC) technique was employed to control the operation of the USMR. The system was studied under an inductive load. The goal function of the MPC algorithm was to minimize the error between the reference and actual values of the AC supply current components defined in the stationary reference frame.

In fact, the USMR topology is derived from the sparse matrix converter topologies proposed in [33,34] and employed as a front rectifier stage of the ultra-sparse matrix converter (USMC) topology in references [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

According to the conducted literature review about the applications and utilization of USMR topology, most applications are concentrated in battery charging systems.

This paper proposes the utilization of the USMR topology (which is a one-quadrant converter) to develop a high-performance one-quadrant DC motor drive fed from a three-phase AC supply, comprising high power quality, including near-sinusoidal input currents (low THD) and unity PF operation. Meanwhile, the overall cost of the proposed DC drive scheme is reduced due to the reduction in switch count (only three power transistors as controllable switches). Also, the unsophisticated control system permits system implementation using a wide range of low-cost data acquisition cards. Such a DC drive scheme is convenient to many industrial and rural pumping applications where reverse power flow (regenerative braking) is not needed and the unidirectional current flow satisfies the operation of the DC motor pump set.

The proposed control unit is based on hysteresis ON–OFF current controllers to control and regulate the currents drawn from the three-phase AC source to the corresponding reference values. Moreover, an additional modulation technique was investigated to assess the capability of the USMR to operate under different control techniques and to seek better or enhanced performance in terms of fixed switching frequency. The second modulation technique is a triangular carrier-based PWM modulation. It is commonly used in the control of voltage source inverters and active power filters.

Performance analysis of the investigated schemes, including qualitative and quantitative assessments, is presented. In addition, an economic comparison between the USMR scheme and the conventional Buck converter scheme is carried out to determine to what degree the proposed scheme is feasible and applicable for one-quadrant applications such as pumping systems.

2. Principles of Operation of USMR

2.1. Converter Power Circuit and Switching States

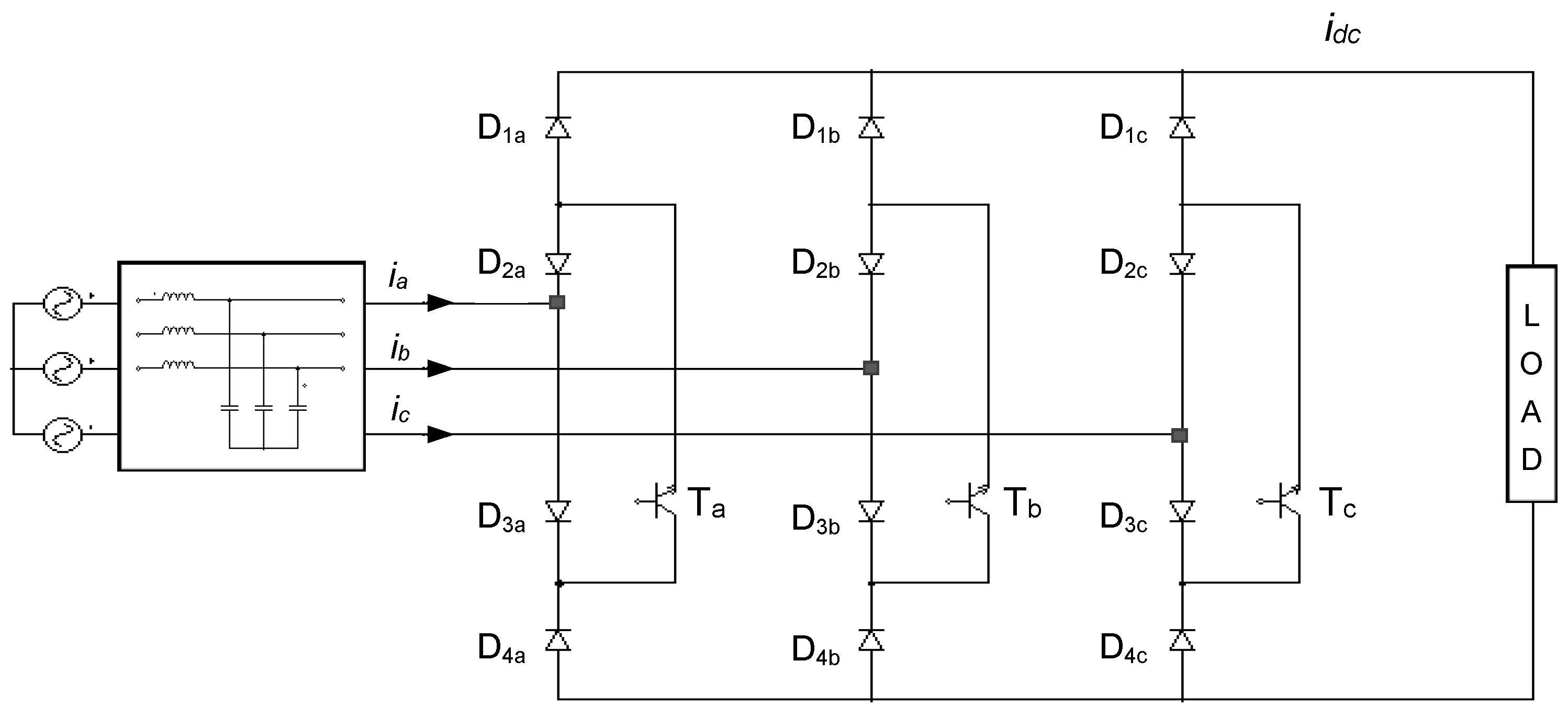

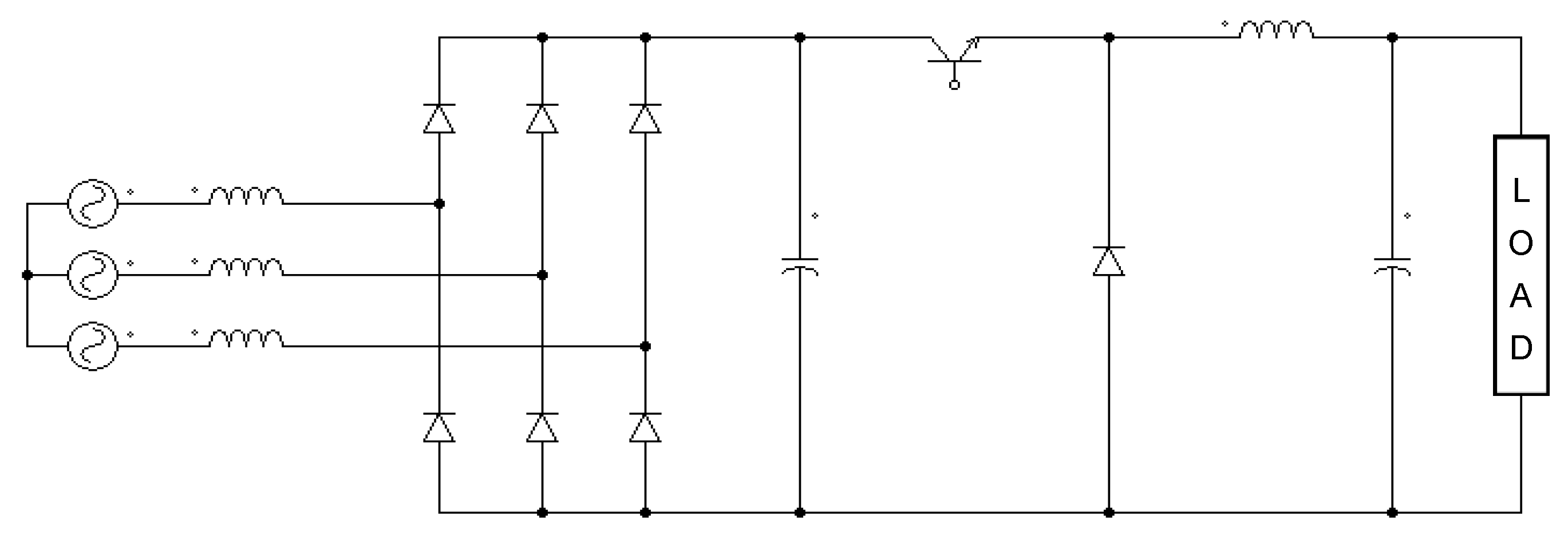

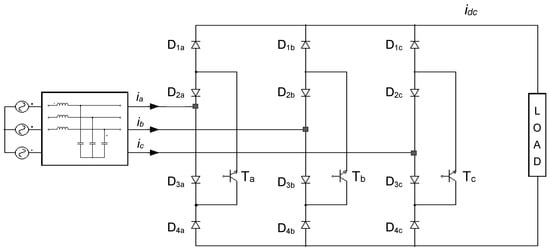

The power circuit of the USMR is composed of three identical branches. Each branch has four power diodes and one power transistor, as illustrated in Figure 1. The power flow is unidirectional, from the AC sources to the load through distinct paths formed by two transistors and four diodes. E.g., the positive AC current ia flows through (D3a, Ta, D1a), while the negative AC current ia flows through (D4a, Ta, D2a). Similarly, the other currents, ib and ic, flow through the corresponding branches. One of the advantages of the ultra-sparse matrix rectifier (USMR) topology lies in its inherent immunity to shoot-through faults, as no short circuits can occur within the same branch. Consequently, there is no requirement for a dead-time (blanking-time) circuit, which is essential in VSI bridge inverters and PWM rectifier configurations addressed in references [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Figure 1.

Power circuit of the ultra-sparse matrix rectifier (USMR).

The input LC filter is inserted between the AC grid and the input terminals of the USMR converter to attenuate the high-frequency components of the AC input currents (due to the high switching frequency of the converter) and prevent them from being injected into the grid. Also, it avoids overvoltages at the input side of the converter.

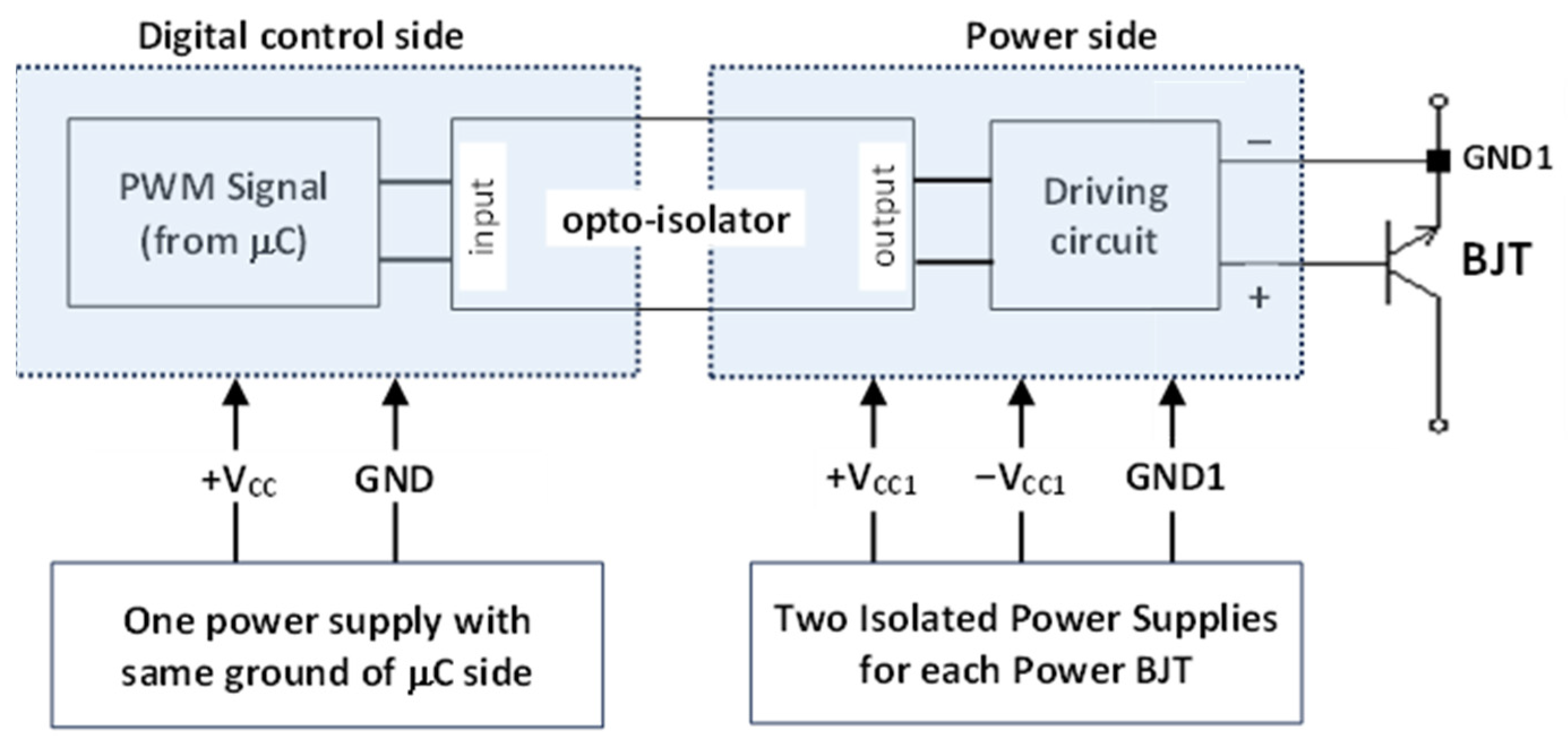

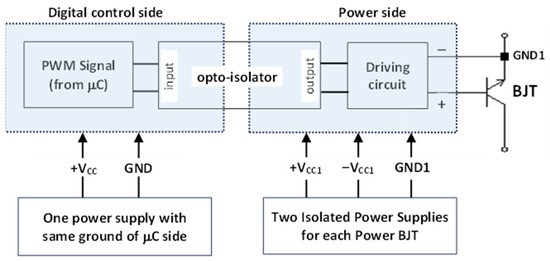

The generated control signals (from microcontroller board or even from logic gates) of power transistors are not connected directly between the base and emitter of the power BJTs. Instead, they are firstly galvanically isolated (using opto-isolators). Galvanic isolation is essential as the emitter terminals do not have the same reference voltage. As indicated in Figure 2, the isolated signals are amplified using a driving circuit incorporated with isolated power supplies, guaranteeing separation of grounds between the low-power side (control side) and the high-power side (base-emitter terminals of the power BJTs).

Figure 2.

Connection of base-emitter terminals of power BJT with the digital control unit.

Since the USMR has three power transistors, eight possible switching states exist. The utilized switching states are summarized in Table 1. According to Table 1, the possible switching states are divided into two main groups: (1) three active states, where two switches are ON simultaneously, and (2) three zero states, where only one switch is ON at a time. When the active states are applied instantaneously, the output voltage is a segment of the line-to-line voltages. Meanwhile, when zero vectors are applied, the output voltage is zero. In this case, the load current freewheels through one of the branches where a unique single switch is turned ON during that moment. The average load voltage is controlled by adjusting the time durations of the active states during the switching period (duty ratios), where the remaining portion of the switching period (difference between the switching period and active states on time) is assigned to the zero states.

Table 1.

USMR switching states and the resultant output DC voltage.

The USMR topology has two unusable states: (Sa Sb Sc = 111), when all switches are ON simultaneously, and (Sa Sb Sc = 000), when all switches are OFF simultaneously. When all switches are ON, the USMR acts as a three-phase uncontrolled rectifier without any pulse width modulation. Meanwhile, when all switches are turned OFF, no current flows from the AC mains to the load. In this case, the USMR is considered OFF.

2.2. Transient Model of USMR Converter System

The three-phase USMR system can be described by a set of differential equations, including the input LC filter, while the USMR can be loaded with a resistive, inductive, or dynamic load (DC motor). The transient model is based on the following assumptions:

- The three-phase grid voltages are a balanced star-connected system.

- The series inductor Ls of the LC filter has a per-phase equivalent resistance Rs.

- The power diodes and transistors are ideal.

Thus, owing to Figure 1, the KVL can be applied as follows:

where k can take a, b, or c representing the three-phase system; is the grid phase-neutral voltage; is the inductor current of phase k; and is the capacitor voltage of phase k.

Also, the KCL can be applied as follows:

where is the grid current of phase k (it also equals the inductor current); is the capacitor current of phase k; and is the converter input current of phase k. Accordingly, the following differential equations are achieved:

The USMR input current is a function of the USMR output current as follows:

where are the switching functions of the available switching states of the USMR presented in Table 1, and sign ( is the sign of the grid phase-neutral voltage.

The instantaneous value of the converter output voltage is a segment (envelope) of line–line voltages or or , based on which switching state is applied and which line–line voltage is the most instantaneously positive. Thus, the DC link voltage can be described by the following equation:

where ,, and are the grid line-to-line voltages, and , , and are switching functions that can take values of 1 or 0 depending on which power transistor is instantaneously conducting, as indicated in Table 1. When the USMR is loaded with a DC motor, the instantaneous value of the DC output voltage is given by the following equation:

where is the DC load voltage (motor terminal voltage); is the DC load current (armature current ); and is the motor back emf of the armature circuit.

2.3. Computation of USMR Global Output Average Voltage

The global average value of the USMR output voltage (load voltage) over the grid frequency cycle is determined using Equations (8)–(13) as follows:

By assuming that the USMR converter is ideal (no power losses), the input active power equals the output DC power .

- Accordingly:

Let

For unity PF operation,

where is the average value of the output voltage; m is considered the current modulation index; Vs max is the maximum value of the input phase voltage; Is max is the peak value of the input phase current; and is the angle between the input phase voltage and current.

2.4. Computation of Output Average Voltage over a Switching Period

Under the space vector PWM, the average DC voltage over the switching period is computed as follows: Assume the balanced three-phase input voltages are described by the following relations:

Since the three-phase AC supply is balanced:

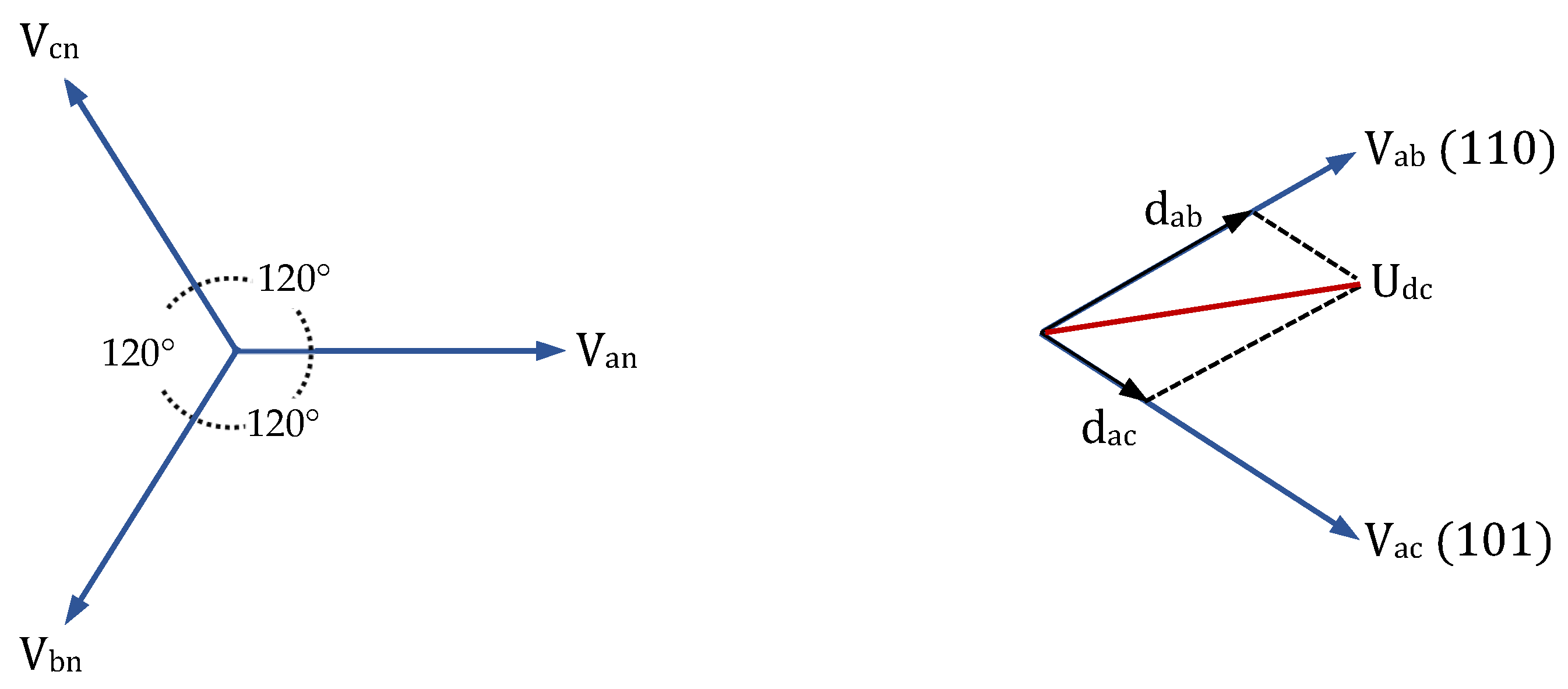

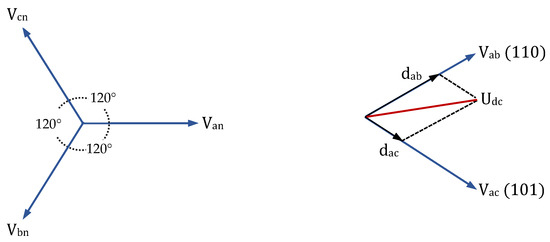

In sector 1, where the angle , the converter switching states (110) and (101) can be applied during the PWM switching. In this case, transistor Ta is considered the pivot switch, which conducts mutually with the other switches Tb and Tc, resulting in instantaneous output voltages of Vab and Vac, respectively.

With the aid of the phasor diagram (shown in Figure 3), the duty cycles dab and dac of the two adjacent effective vectors along the axis Vab and Vac are computed using the following relations:

Figure 3.

Space vector representation of DC voltage of USMR in sector 1 .

Hence, the average value of the rectifier output voltage over the switching period can be determined using the following vector relation:

Therefore, the average value of the rectifier output voltage through the switching period of the space vector pulse width modulation (SV-PWM) is

where .

In addition, the average DC voltage for the entire 60° interval (whole sector) can be calculated with the aid of the following mathematical relations:

Thus, the average value of the output DC link voltage of the USMR over a complete sector of 60° is approximately .

3. Description of the Investigated DC Drive System

3.1. System Block Diagram

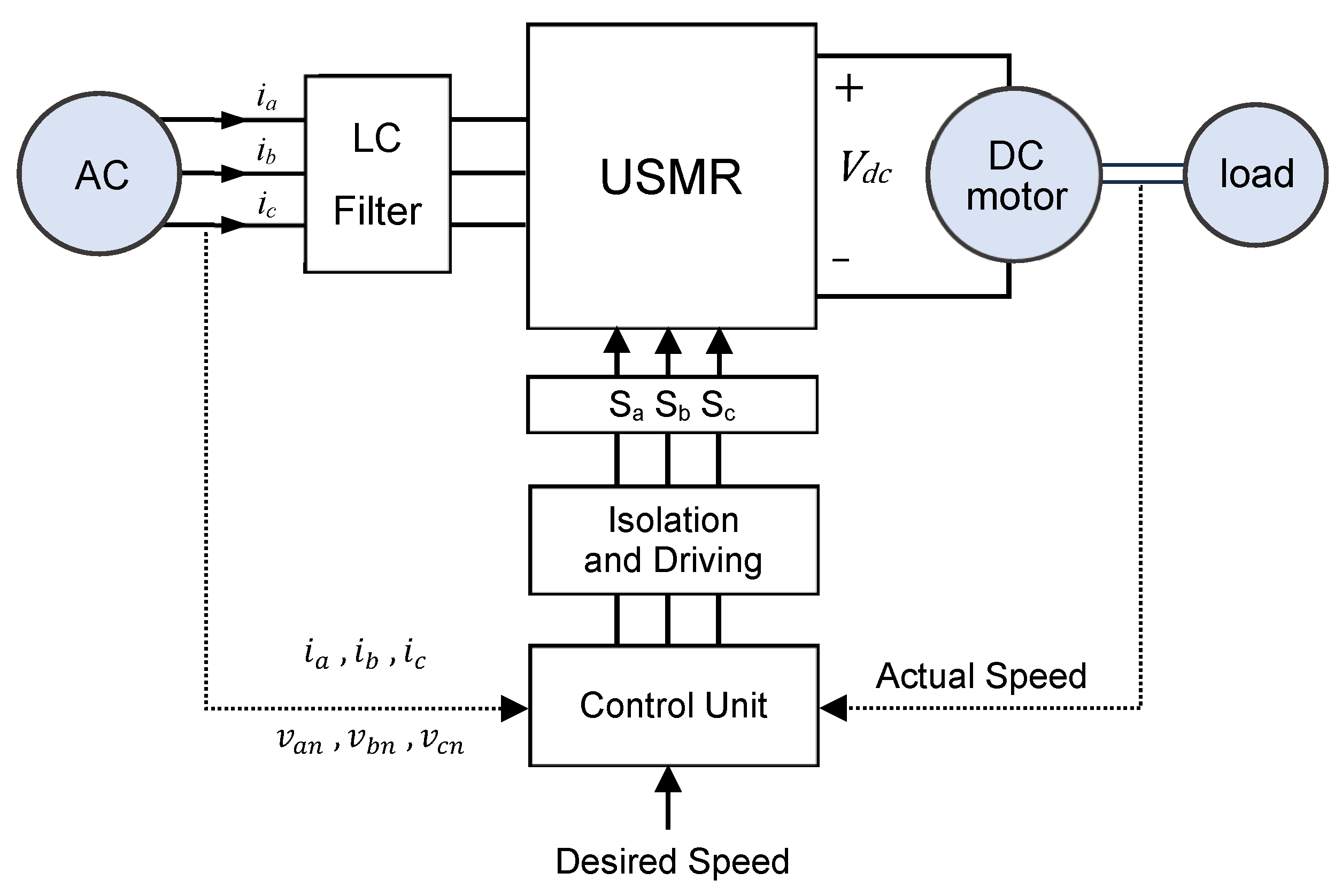

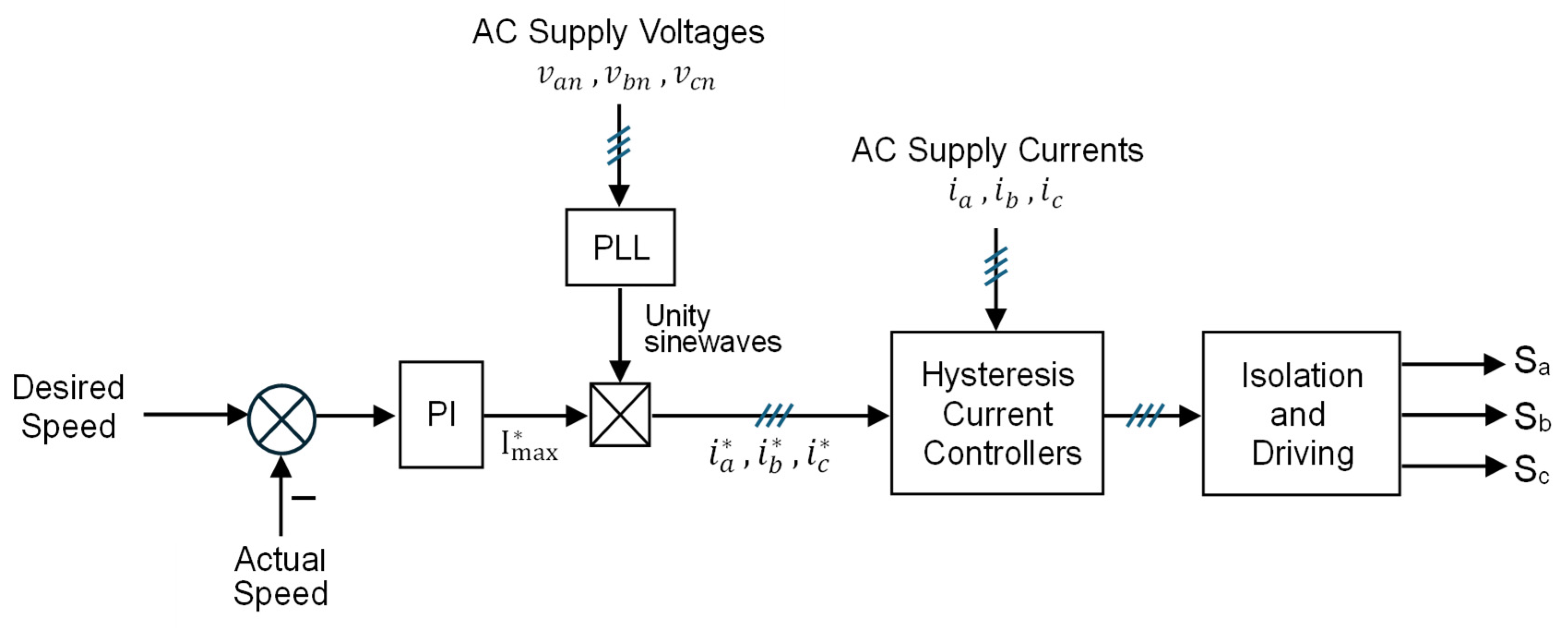

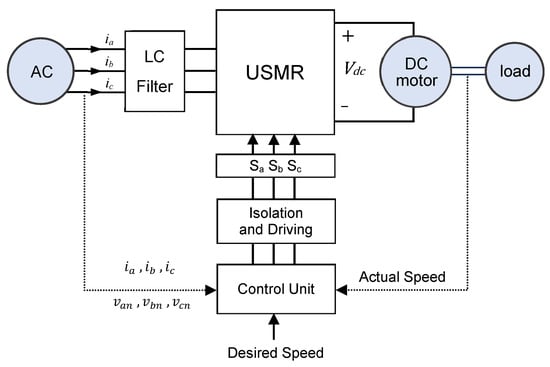

The block diagram of the investigated system is illustrated in Figure 4, where the DC motor is fed from the USMR. The control unit of the USMR-DC motor system is composed of three main parts:

Figure 4.

Block diagram of the investigated USMR-fed DC motor drive system.

- (1)

- Outer closed loop speed control loop using a PI controller, where its output represents the peak desired (reference) value of the AC current to be drawn from the AC supply.

- (2)

- Inner current control loop using three hysteresis ON–OFF current controllers to regulate the AC input currents to the corresponding reference values.

- (3)

- Reference the current generation unit that generates three-phase sinusoidal signals (with unity amplitude) synchronized with the AC supply using a phase-locked loop (PLL).

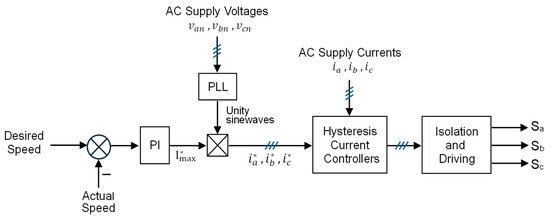

The unity amplitude 3-Φ sinusoidal signals are multiplied by the peak desired value of the AC current, which is considered the output of the speed controller. The detailed block diagram of the control unit is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Detailed block diagram of the USMR control unit.

3.2. Design of Speed Controller

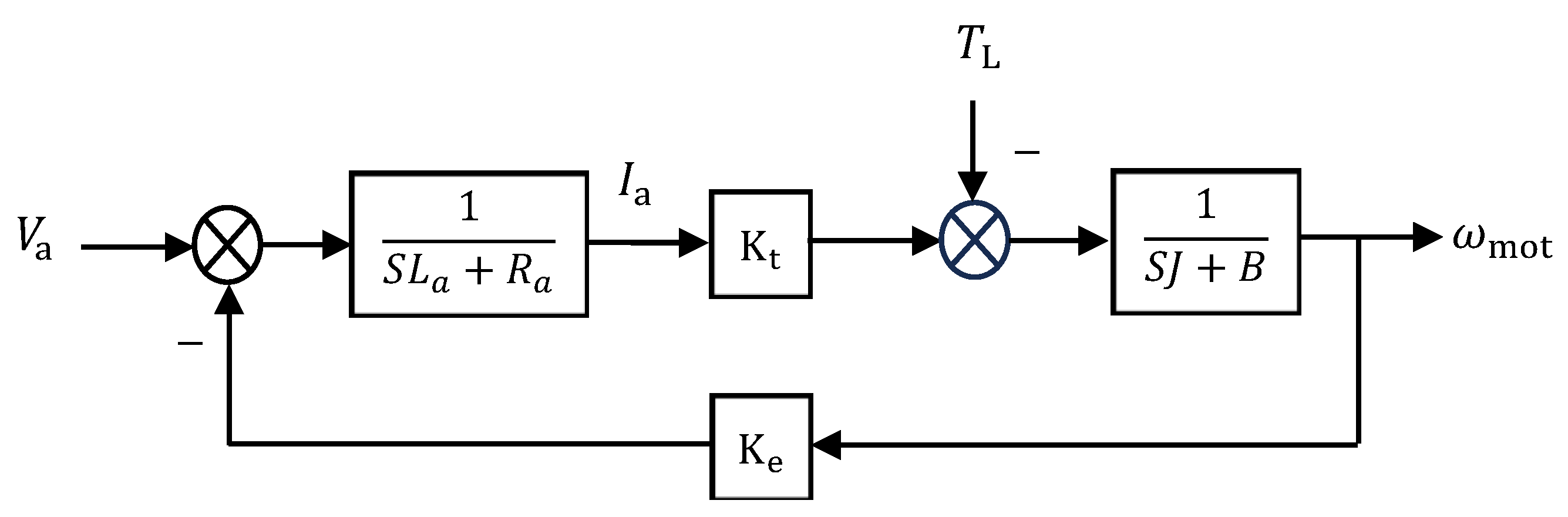

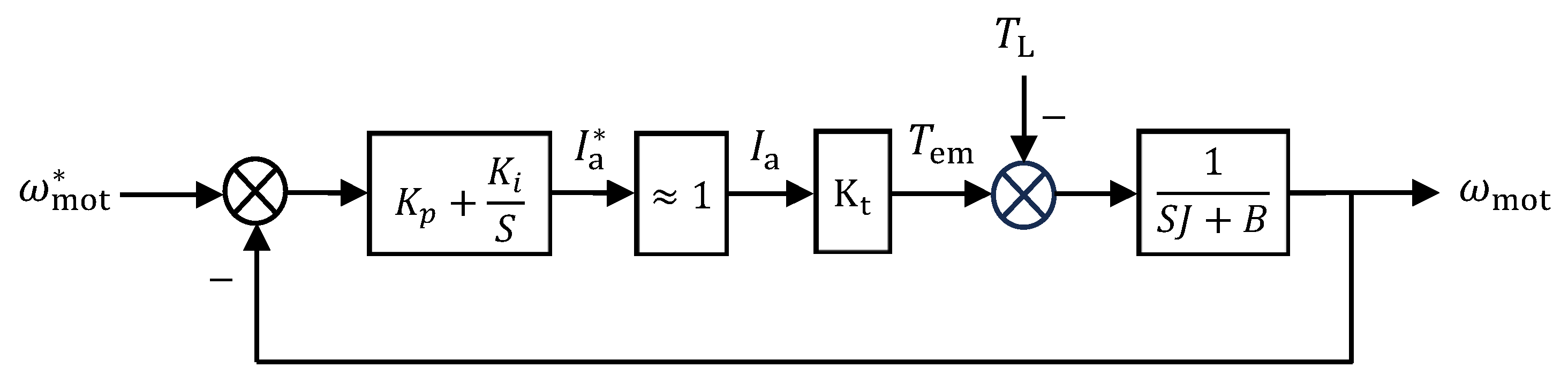

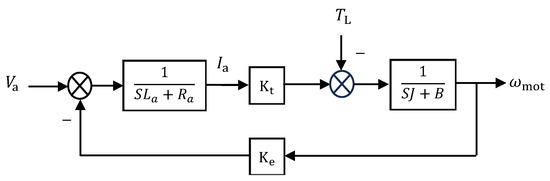

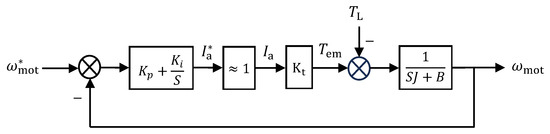

The block diagram of the second-order model of the DC motor is shown in Figure 6. Since the USMR operates at a high switching frequency, the AC currents (, , and ) are well controlled to the reference values (almost equal to their reference values) (, , and , respectively). Consequently, the reference armature current equals approximately the actual armature current . Therefore, the closed-loop transfer function of the USMR is unity. In addition, as the mechanical time constant of the DC motor is much bigger than the electrical time constant of the armature circuit, the armature current settles down faster than the mechanical speed. In other words, the speed loop (outer loop) is slower than the armature current loop (inner loop). Thus, the armature transfer function can be considered unity, as an accepted approximation. The resultant simplified speed control loop of the investigated DC drive system is depicted in Figure 7. A PI controller with limited output was chosen as a speed controller in the investigated DC drive.

Figure 6.

Block diagram of separately excited DC motor.

Figure 7.

Simplified speed control loop of the DC motor drive.

The transfer function of the PI speed controller is given by Equation (32):

The open-loop gain function is given by Equation (33), as follows:

Thus, the general form of the closed-loop transfer function of the speed control loop is given by Equation (34), as follows:

where H(S) is 1 for unity feedback. Accordingly, the closed-loop transfer function will have the following formula:

The gains Kp and Ki can be computed by comparing the characteristic equation of with the standard form given by Equation (36) and solving for the proper values of and . The standard form of the characteristic equation is given by the following:

Accordingly, the characteristic equation is:

Hence, the following relations are obtained:

Thus, the PI gains can be determined as follows:

The damping ratio was chosen to be 0.7 because it gives a good compromise between a satisfactorily fast response and acceptable low peak overshoot. Meanwhile, the natural frequency was selected based on the required settling time , as follows:

If is chosen to be 0.5 s, then will be 11.42 rad/s. Hence, the gains and will be 1.13 and 10.25, respectively. In fact, the previous method of determining (computing) the gains of the PI speed controller is considered a good initial estimate and has led to satisfactory speed response. Extra improvement can be achieved by fine-tuning the gains either by applying any evolutionary search algorithms to achieve a satisfactory transient response or by autotuning in Simulink/Matlab®R2017.a. The overall USMR system has been studied using the PSIM® 9.1 simulation tool, which is customized to simulate power electronics and motor drive systems. The simulation parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters.

4. Results

Some simulation results of the investigated USMR-fed DC motor drive system are presented in this section. The system was studied with two types of PWM techniques: an ON–OFF hysteresis controller and a triangular carrier-based PI controller. The system was investigated under different operating conditions as follows: steady-state and transient AC current control mode, closed loop DC voltage control mode, and closed loop speed control mode. Besides the qualitative analysis of the obtained results, the study also included a quantitative analysis. A comparison with the conventional one-quadrant DC drive operated from a DC Buck chopper was conducted as well.

4.1. USMR Performance with ON–OFF Hysteresis Current Controllers

This section presents some simulation results of the USMR system driven by an ON-OFF hysteresis current controller.

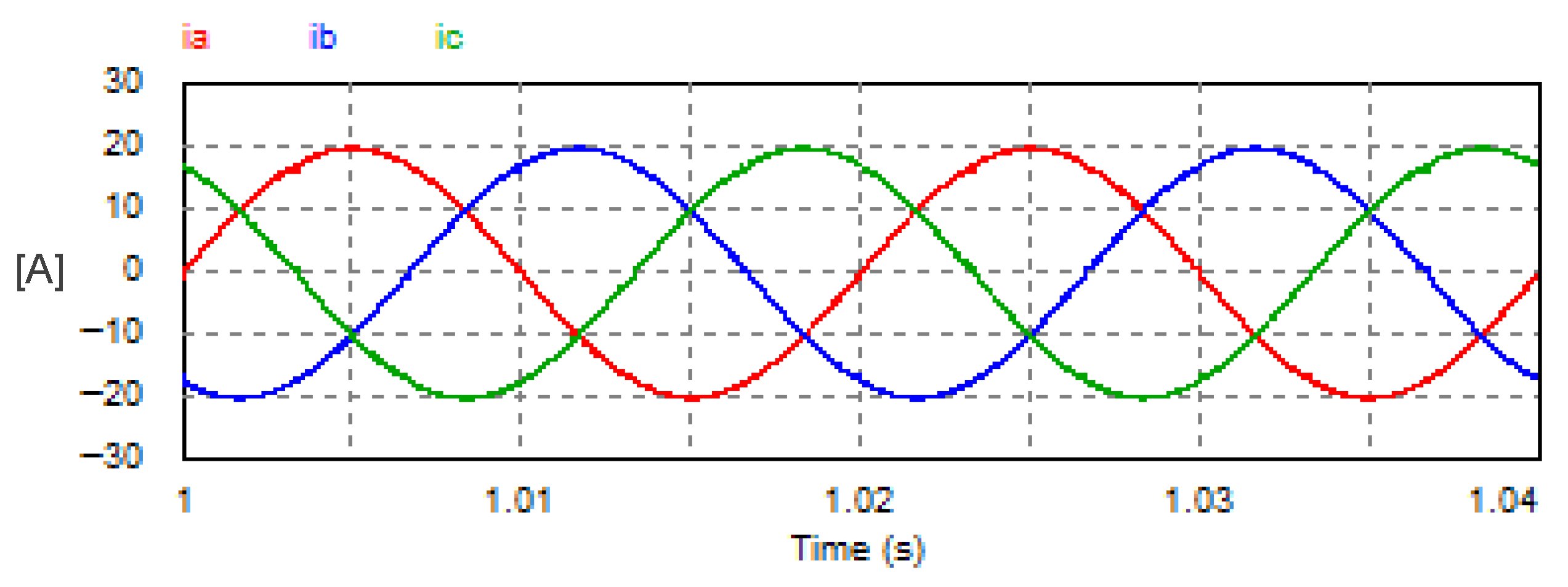

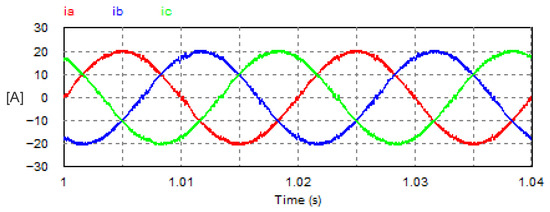

4.1.1. Steady-State AC Current Control Mode

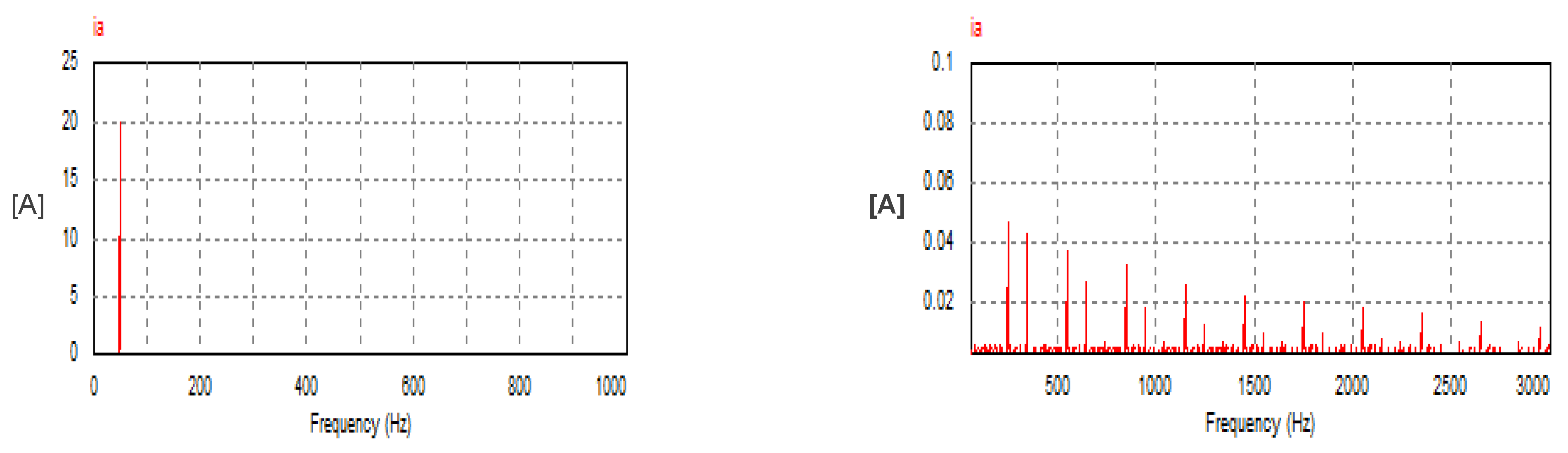

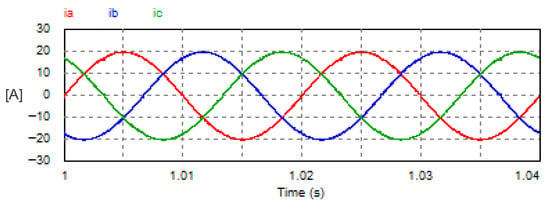

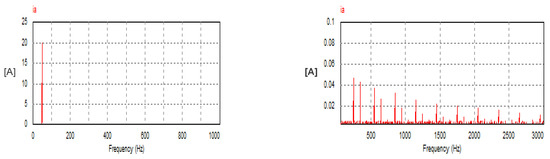

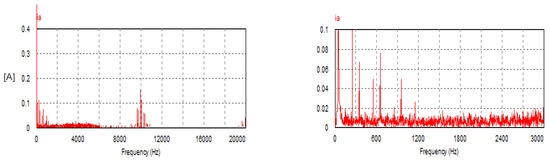

In this mode, the USMR operates under ON–OFF current control of the AC currents. The AC grid currents are controlled to the desired peak value (20 A). The actual grid currents and the resultant load voltage are plotted at a steady state. The corresponding harmonic spectra are presented as well. Owing to the results, the grid currents are well controlled to the desired value, as illustrated in Figure 8. The THD of the AC current is 1.07%, which meets the standards. The harmonic spectrum of the AC current (ia) is presented in Figure 9. The spectrum contains the 1st harmonic at 50 Hz with an amplitude of 20 A (see LHS graph of Figure 9). The spectrum contains odd harmonic orders (5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 25, etc.) with relatively small amplitudes of less than 0.25% of the fundamental component) (see RHS graph of Figure 9). Moreover, the input PF is 0.999.

Figure 8.

Steady-state AC currents with USMR under ON–OFF current control.

Figure 9.

Harmonic spectrum of AC current with USMR under ON–OFF current control.

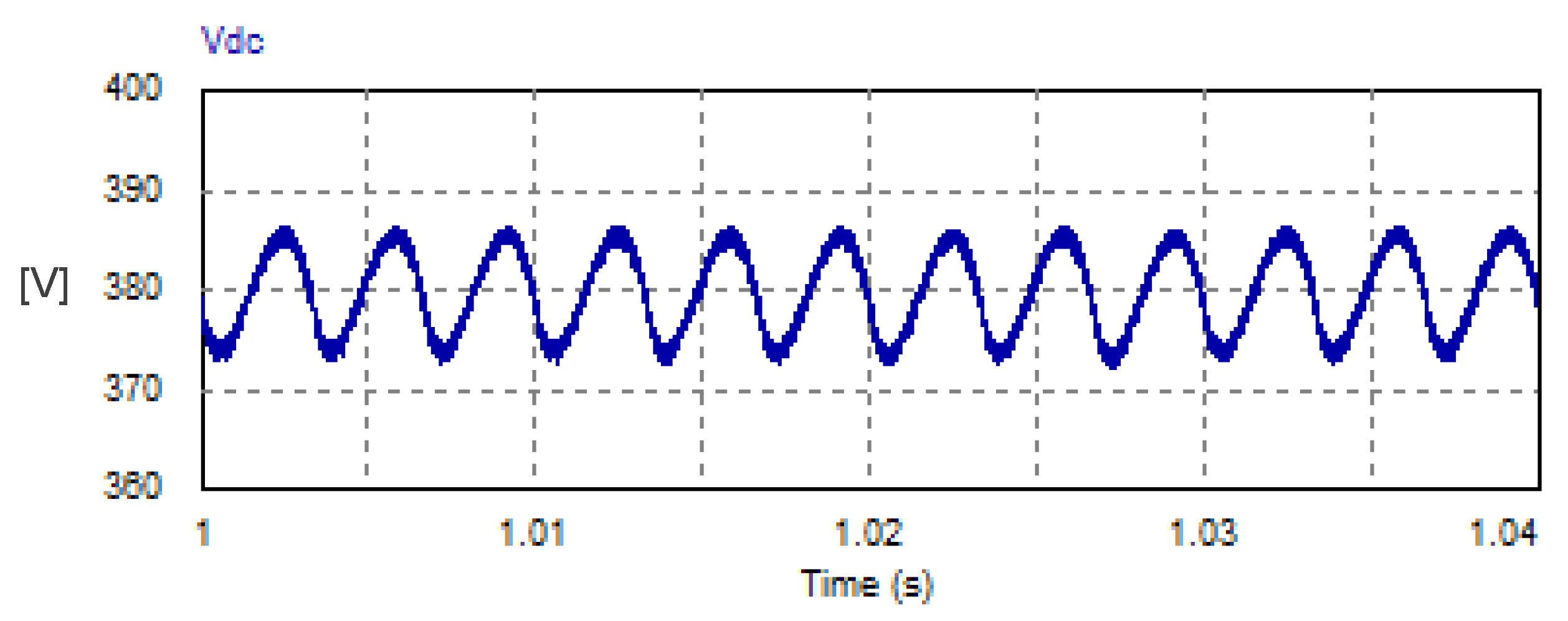

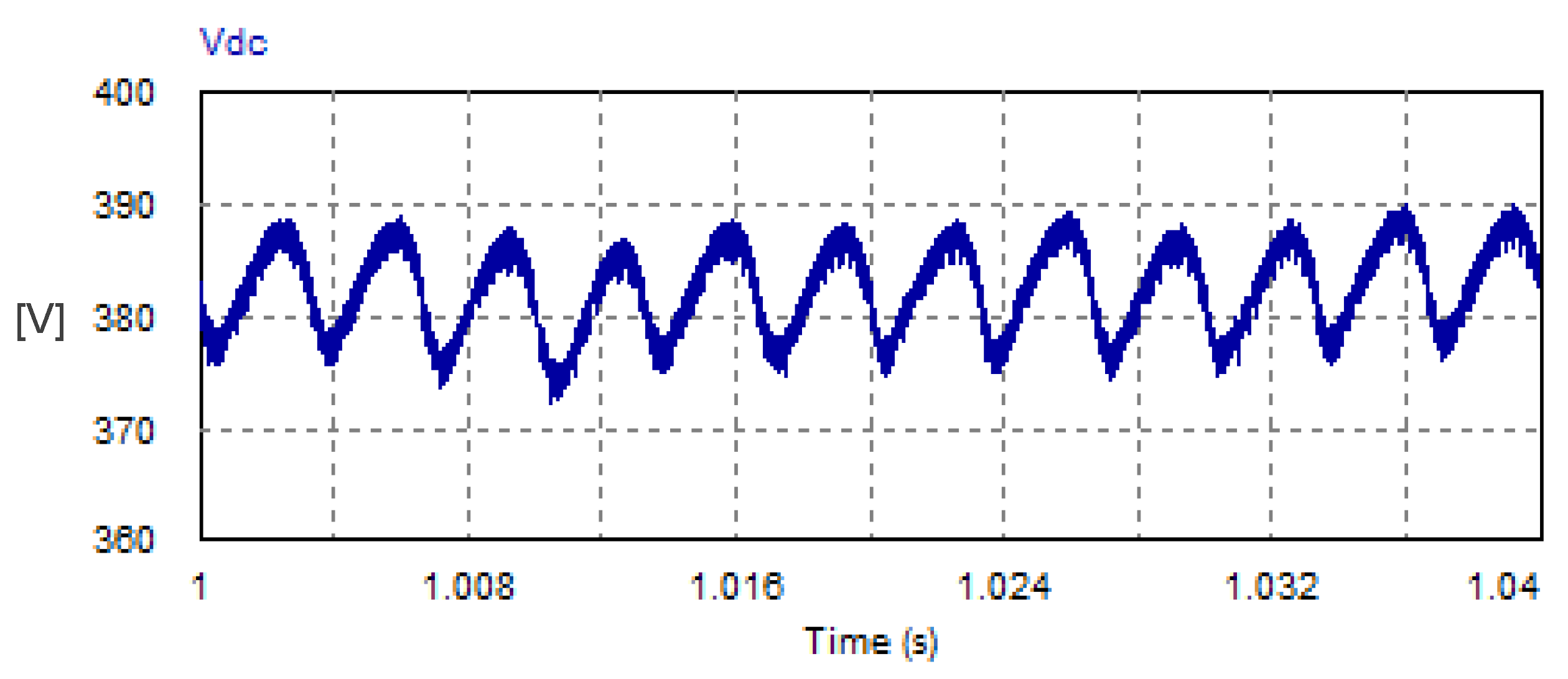

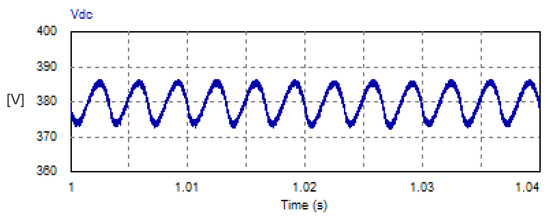

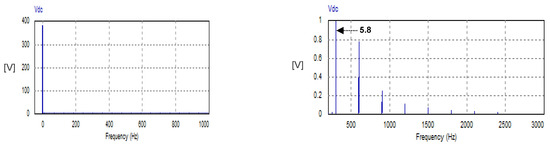

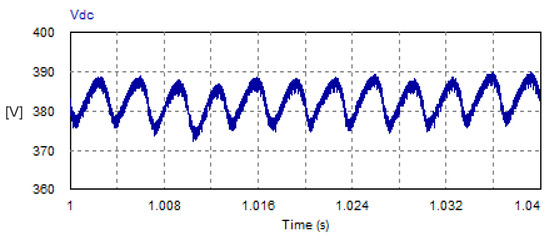

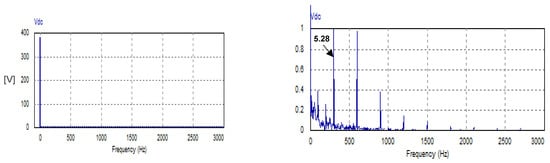

The corresponding waveform of the DC link voltage is illustrated in Figure 10, where the reference AC current was adjusted to a peak value of 20 A, and the resistance of the load is 20 W. The DC link voltage has an average value of 380.31 V. The peak–peak ripple voltage is 14 V, which is 3.68% of the average load voltage. The harmonic spectrum of the DC link voltage is depicted in Figure 11. Owing to the obtained results, the DC link component is 380.31 V (see LHS graph of Figure 11). The low-order harmonic is the sixth component, with an amplitude of 5.8 V, which is 1.54% of the average value of the DC link voltage (see RHS of Figure 11). The harmonic spectrum does not contain triple harmonics. It contains even harmonics of orders 6, 10, 18, 24, and 30 with relatively negligible magnitudes (see RHS graph of Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Steady-state DC load voltage with USMR under ON–OFF current control.

Figure 11.

Harmonic spectrum of DC load voltage with USMR under ON–OFF current control.

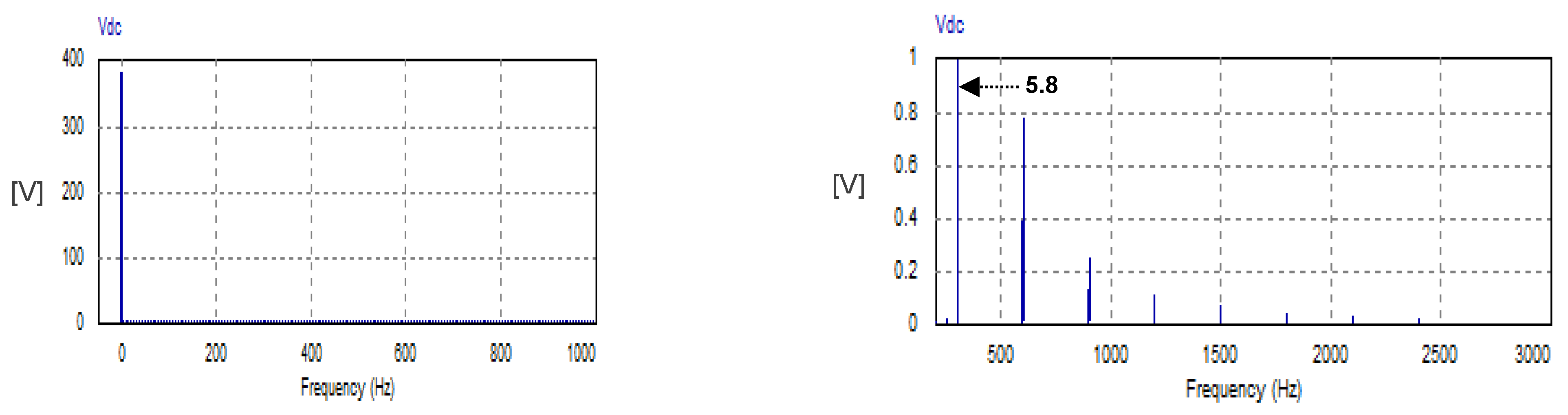

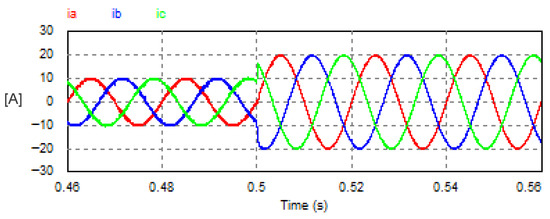

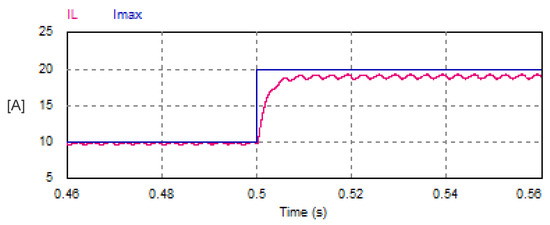

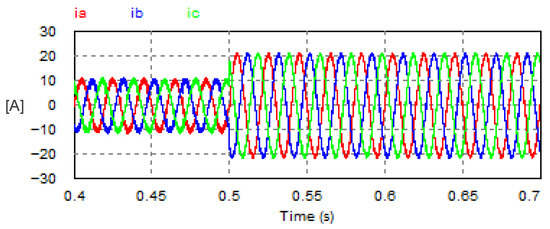

4.1.2. Transient AC Current Control Mode

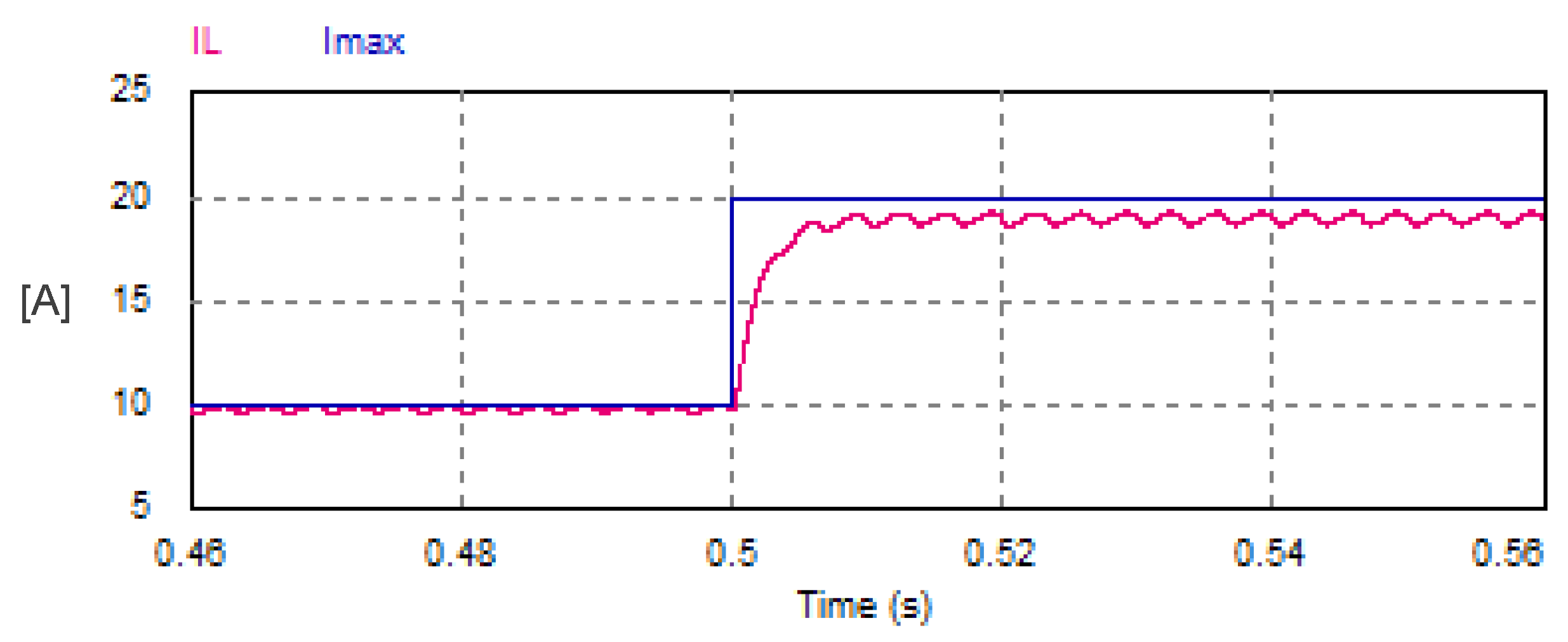

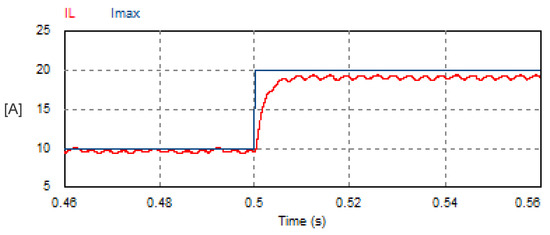

The USMR system was studied under a step change of reference AC currents from 10 A to 20 A. The AC grid currents were well controlled to the desired peak values (10 A, then 20 A), as shown in Figure 12. The reference amplitude (peak value) of the AC currents and the actual DC link current are plotted in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Transient response of the AC currents with USMR under ON–OFF current control.

Figure 13.

Transient response of the reference peak AC currents and the corresponding DC link current with USMR under ON–OFF current control.

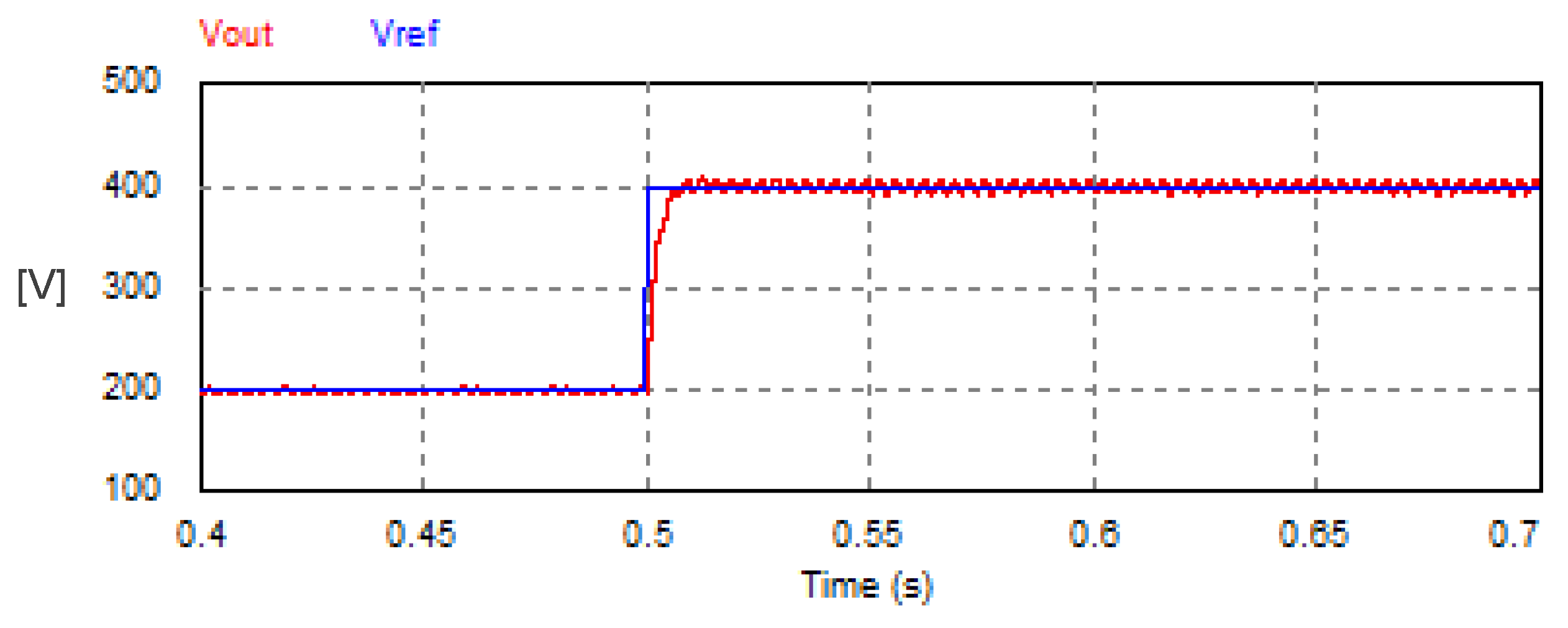

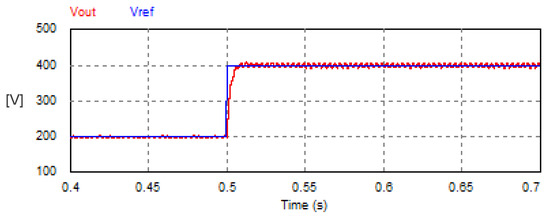

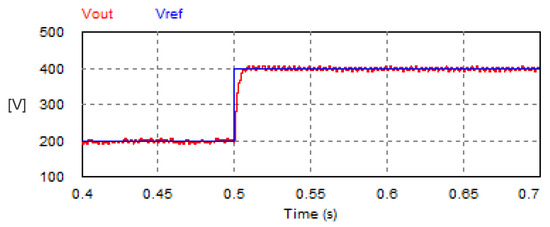

4.1.3. Closed-Loop DC Voltage Control Mode

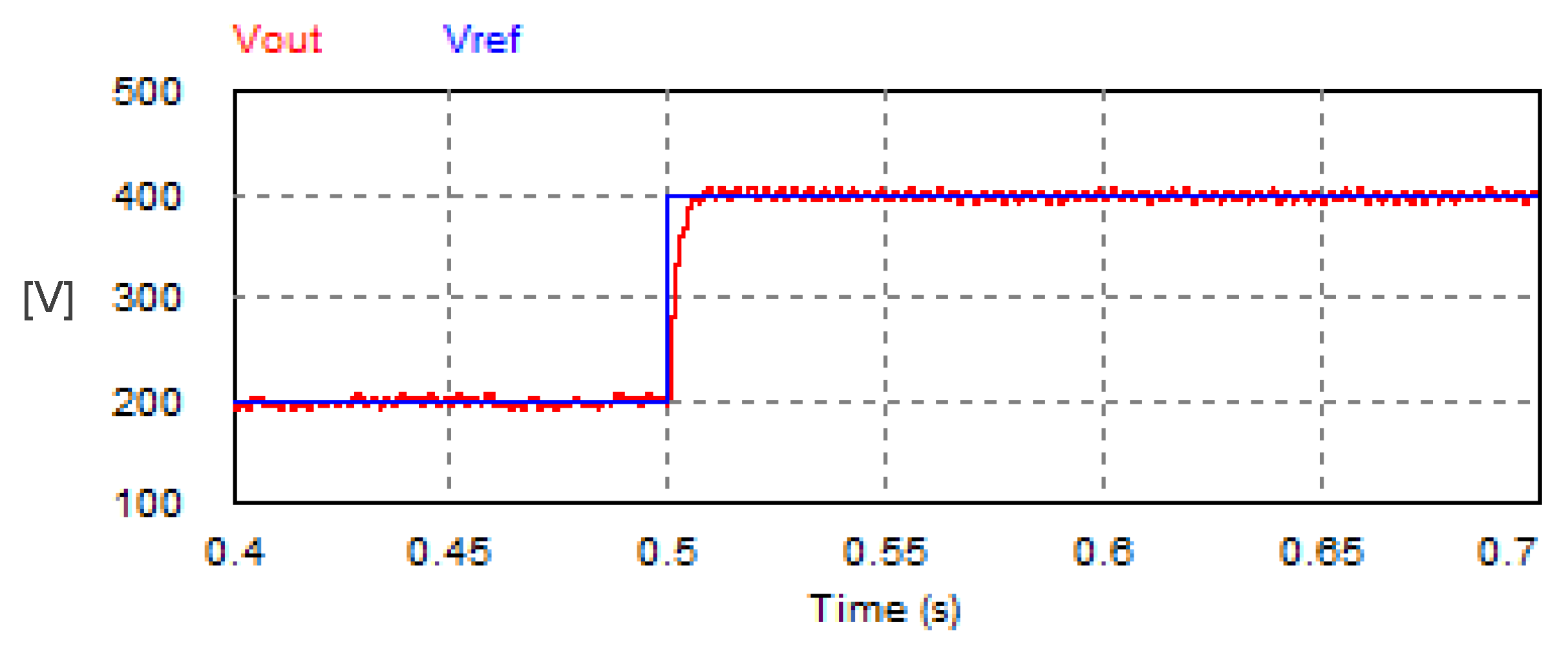

The DC load voltage of the USMR system is regulated with a closed-loop feedback system based on a PI voltage controller. The system was investigated under a step change of the reference DC voltage as illustrated in Figure 14. The set point of the output DC voltage changed from 200 V to 400 V. The settling time of the load voltage response is 0.0082 s. The amplitude of the AC current changed from 10.55 A to 21.18 A, as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 14.

Step response of the DC link voltage of USMR with voltage closed-loop control.

Figure 15.

Corresponding AC currents with USMR under closed-loop control of DC voltage.

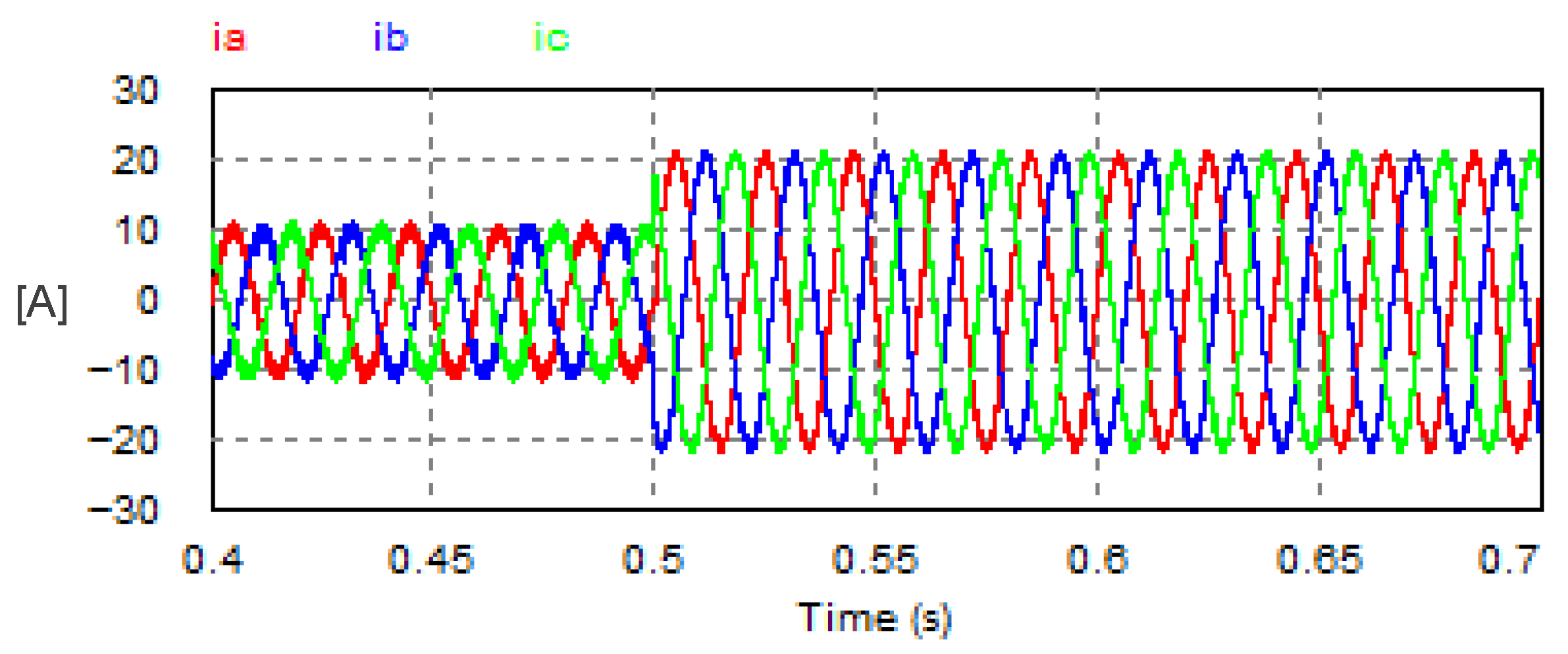

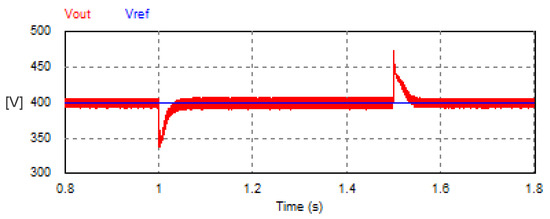

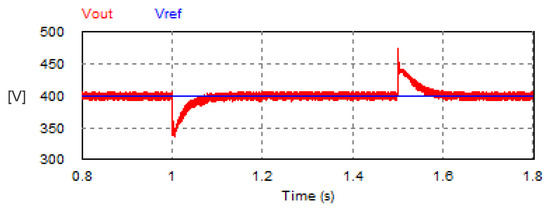

In addition, the transient response of the DC load voltage of the USMR was studied under a sudden change in the load. The load was changed suddenly from 20 W to 16.67 W at time t = 1 s. Then, the additional load was removed suddenly at time t = 1.5 s. The resultant waveform of the DC load voltage is depicted in Figure 16. The results indicate that the DC voltage control loop succeeded in returning the DC load voltage to the reference value within 0.078 s when the load increased. The worst transient dip in load voltage did not exceed 16% of the average load voltage. Also, when the additional load was removed, the transient jump in the DC voltage did not exceed 14% of the average load voltage. The DC voltage control loop succeeded again in returning the DC load voltage to the set point within approximately 0.08 s.

Figure 16.

Transient response of the DC link voltage with ON–OFF hysteresis controller under sudden load variation.

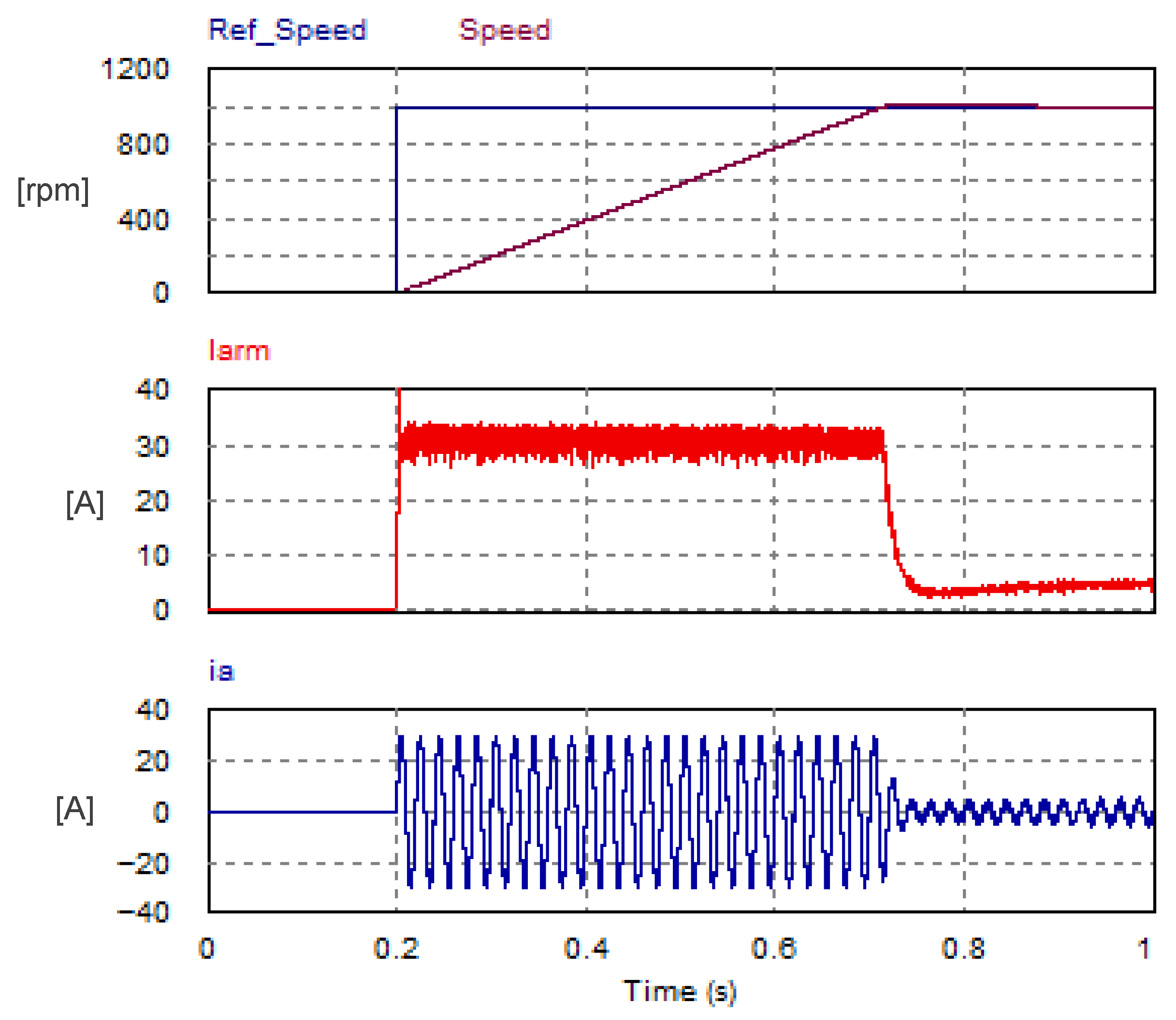

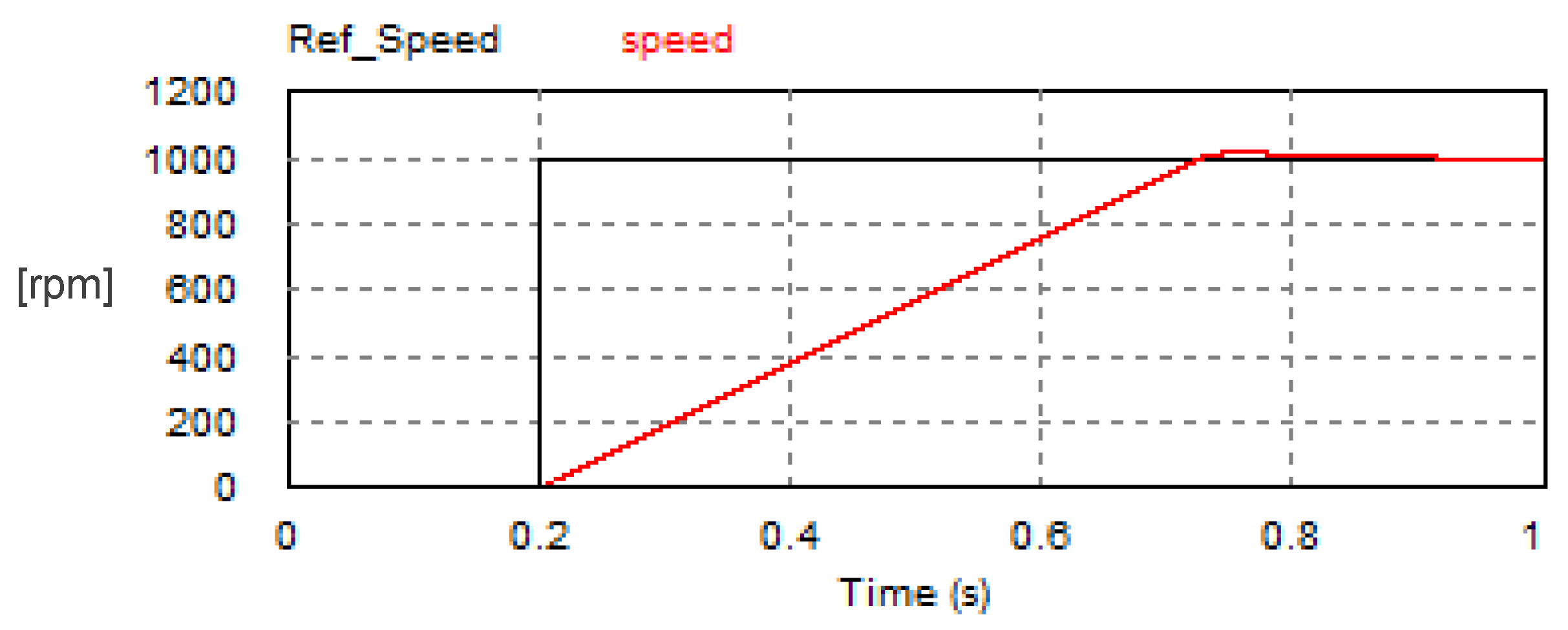

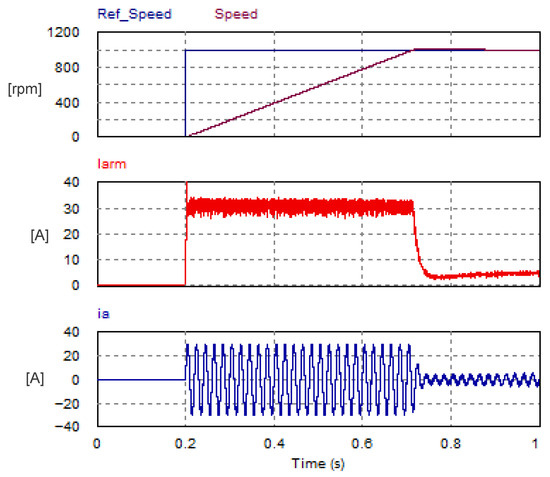

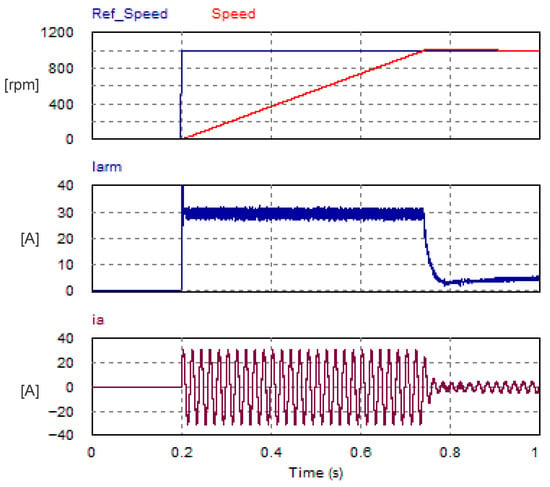

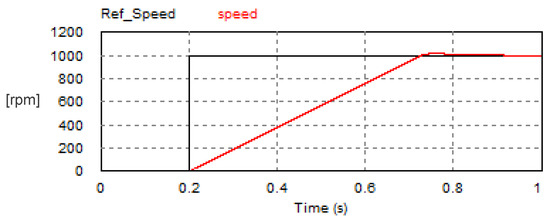

4.1.4. Closed-Loop Motor Speed Control

The USMR scheme with hysteresis current controller was investigated when the load was a separately excited DC motor whose parameters are given in Table 2. The motor speed was regulated in a closed loop using a PI speed controller. The step response of the mechanical speed is plotted in Figure 17. The motor was loaded with a fixed torque of 2 N.m. The set point was changed from 0 rpm to 1000 rpm. It is observed that the speed response had a small peak overshoot of 22.8 rpm (2.28% of the set point), while the settling time was 0.589 s. The corresponding armature current (Iarm) and AC grid current of phase a (ia) are plotted in Figure 17 as well.

Figure 17.

Step response of mechanical speed and the corresponding armature and AC currents under ON–OFF hysteresis current controller.

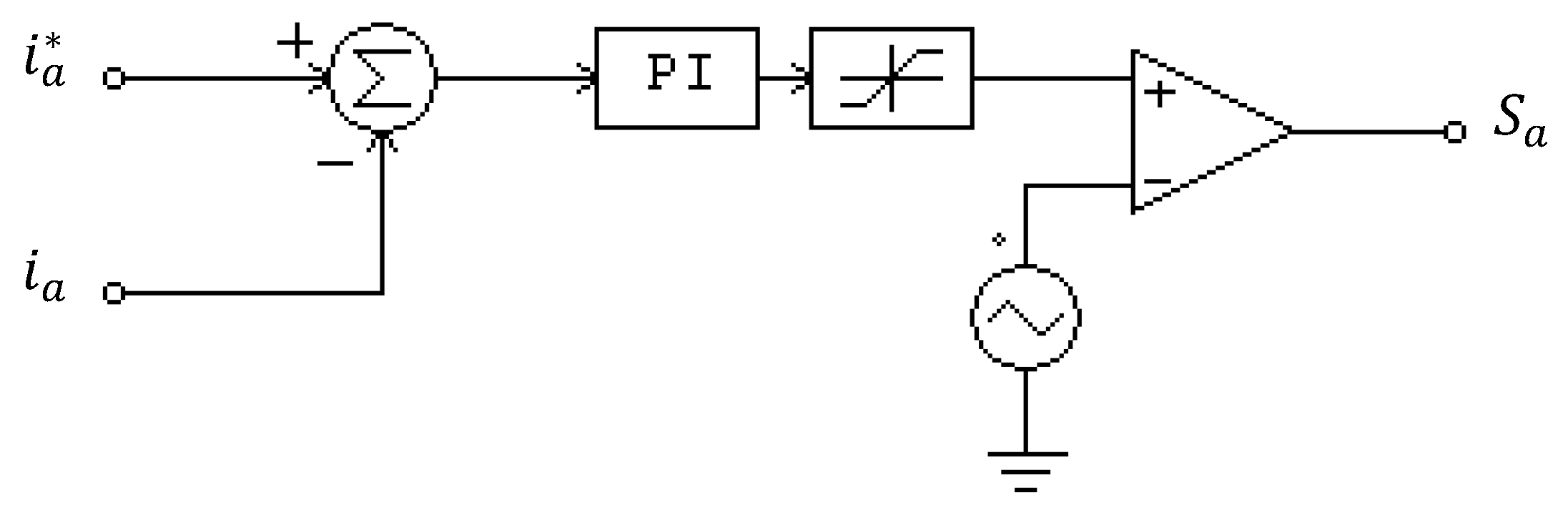

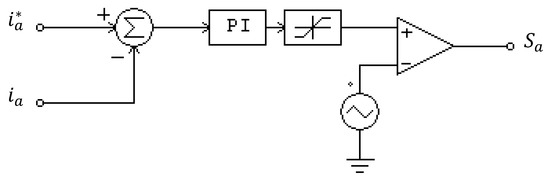

4.2. Performance of USMR with Triangular Carrier-Based PWM Modulation

Another PWM modulation technique for the USMR system was studied. The investigated PWM technique was a triangular carrier-based PI current controller. The technique operates at a fixed switching frequency, unlike the ON–OFF hysteresis current controller, which results in unpredictable and variable switching frequency. The PWM modulator, illustrated in Figure 18, is composed of a subtractor (to compute the difference between reference and actual AC grid current); PI current controller with an upper limiter; and high-frequency triangular signal. The output of the PI controller was compared with the triangular waveform to produce a PWM signal with a constant switching frequency. This PWM technique is commonly applied in current-controlled voltage source inverters and active power filter schemes [44]. The overall USMR control unit was composed of identical PI controllers (one controller for each phase).

Figure 18.

Carrier-based PWM modulator (for phase a).

The transfer function of the PI current controller is given by Equation (43):

The gains and are determined by applying the following empirical formulae presented in reference [44]:

where is triangular carrier frequency; is the total input series inductance (including grid and filter); and is the average value of the DC link voltage. The carrier frequency is set to 10 kHz to produce high-quality waveforms of the AC grid currents.

The simulation results of the USMR system under triangular carrier-based PWM modulation are presented below for steady-state AC current control, transient AC current control, closed-loop control of the DC voltage, and closed-loop speed control of the DC motor.

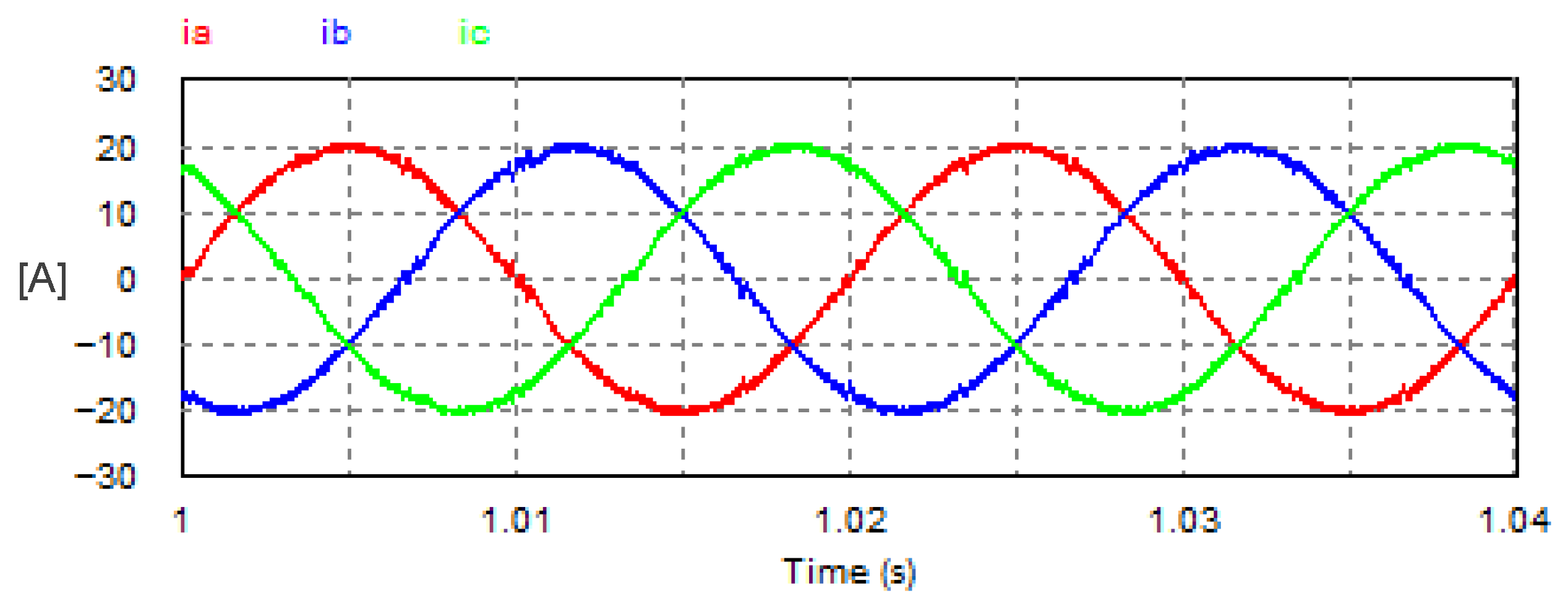

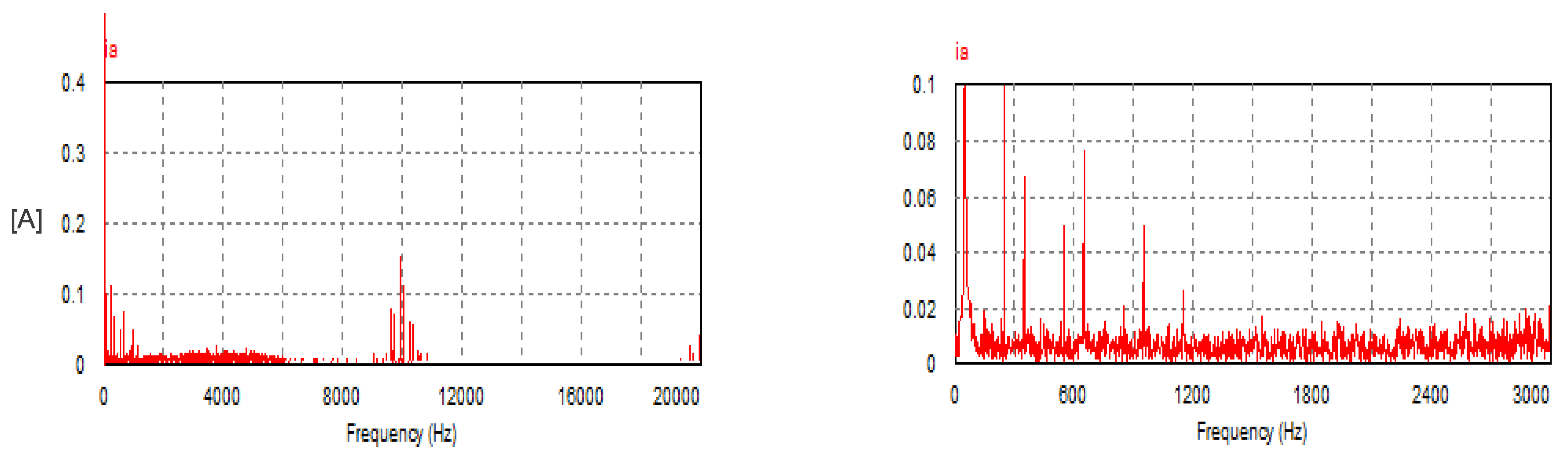

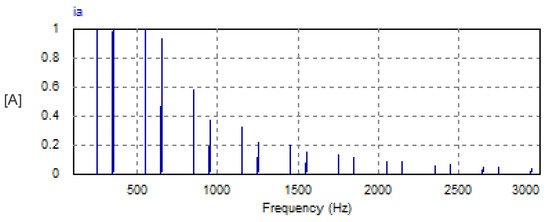

4.2.1. Steady-State AC Current Control Mode

The USMR operates under a triangular carrier-based PWM. The carrier frequency is set at 10 kHz. AC grid currents are controlled to the desired peak value (20 A). Owing to the results, the grid currents are well controlled to the desired value as illustrated in Figure 19. The THD of the AC current is 2.74%. Moreover, the corresponding harmonic spectrum of the AC current (ia) is presented in Figure 20. The spectrum contains the 1st harmonic at 50 Hz with an amplitude of 20 A. The spectrum contains odd harmonics of orders with relatively small amplitudes but higher than that of the hysteresis band. Moreover, the spectrum contains side band components around the switching frequency (10 kHz).

Figure 19.

Steady-state AC currents with USMR under triangular carrier-based PWM.

Figure 20.

Harmonic spectrum of AC current with USMR under triangular carrier-based PWM.

The steady-state waveform of the DC link voltage is illustrated in Figure 21. The average DC load voltage is 383.14 V, While the peak–peak ripple voltage is 17.81 V, which is 4.65% of the average load voltage.

Figure 21.

Steady-state DC load voltage with USMR under triangular carrier-based PWM.

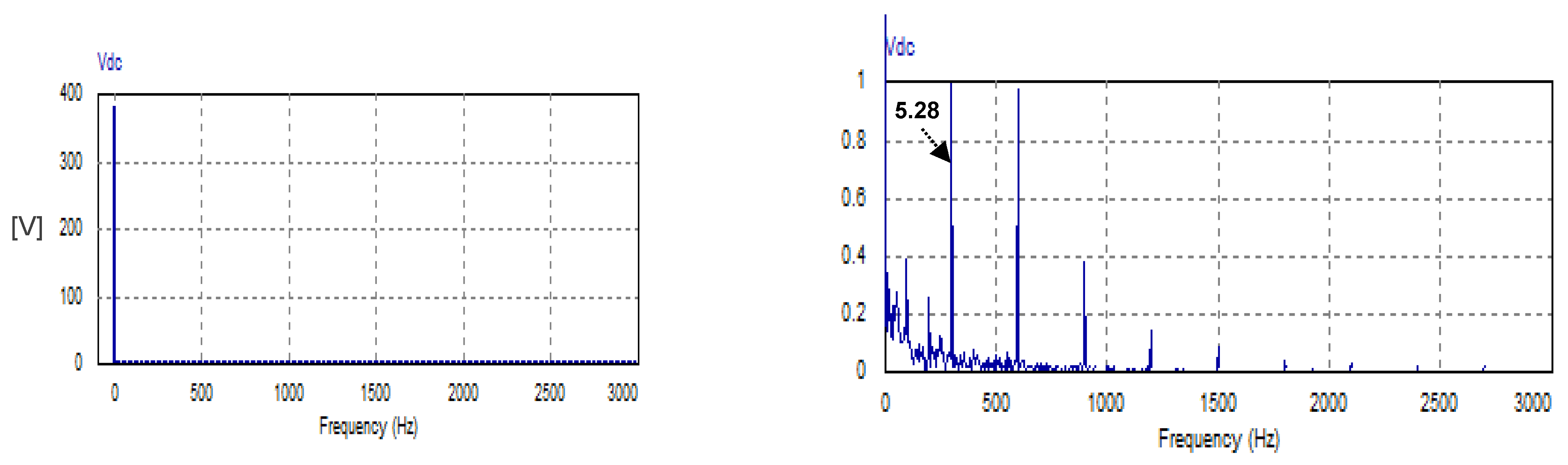

The harmonic spectrum of the DC link voltage is depicted in Figure 22. The low-order harmonic is the 6th component (pulsates at 300 Hz), with an amplitude of 5.28 V, which is 1.37% of the average value of the DC link voltage (see RHS of Figure 22). The harmonic spectrum does not contain triple harmonics. It contains even harmonics of orders 6, 10, 18, 24, and 30 with relatively negligible magnitudes but slightly greater than those achieved by the ON–OFF hysteresis controller.

Figure 22.

Harmonic spectrum of DC load voltage with USMR under triangular carrier-based PWM.

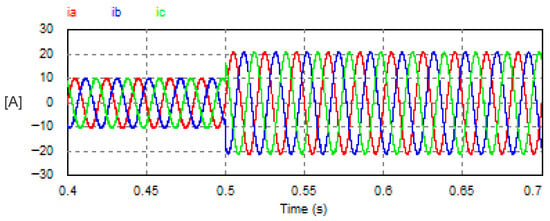

4.2.2. Transient AC Current Control Mode

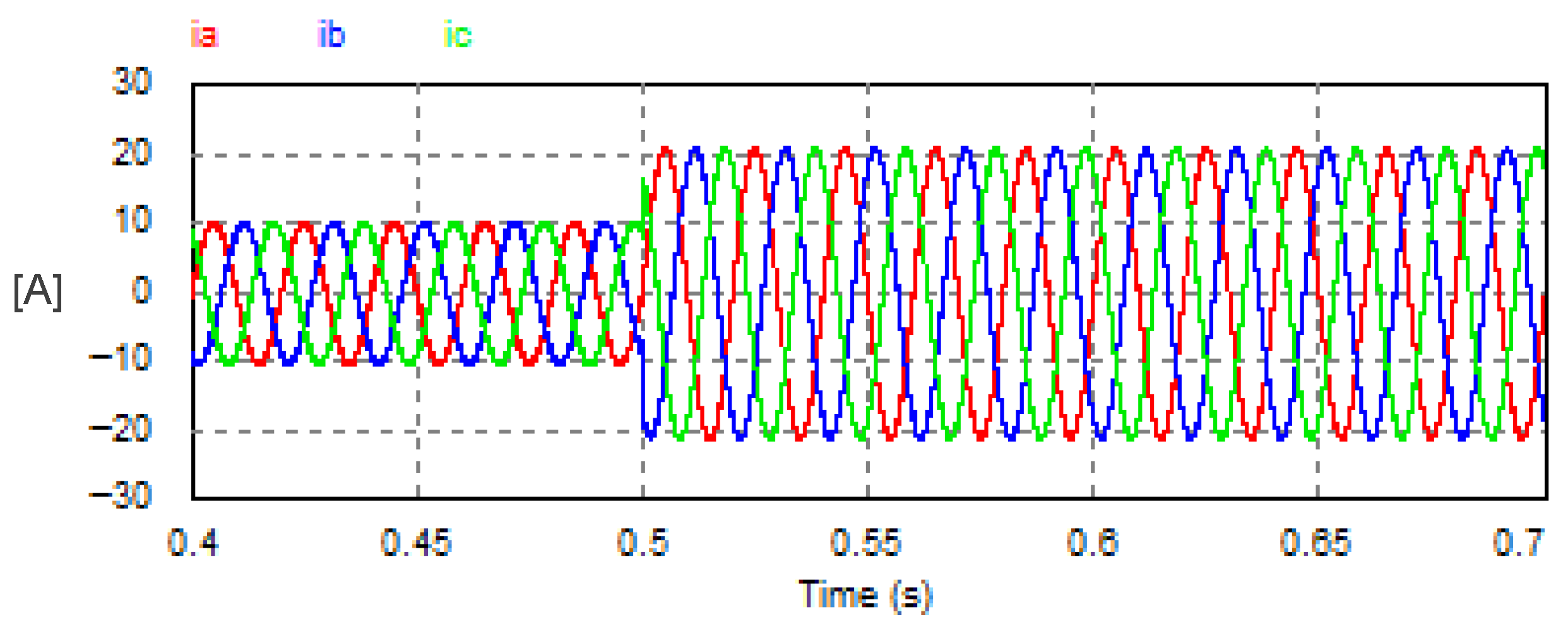

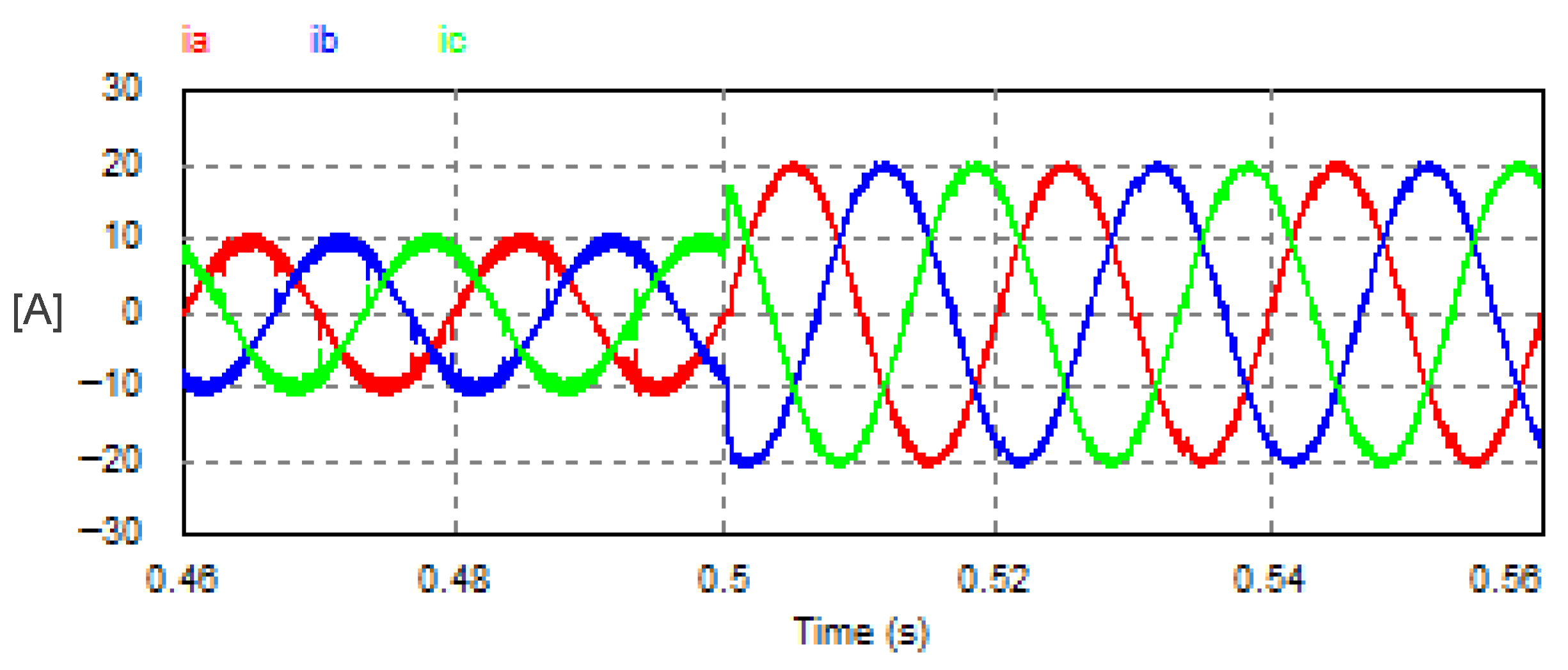

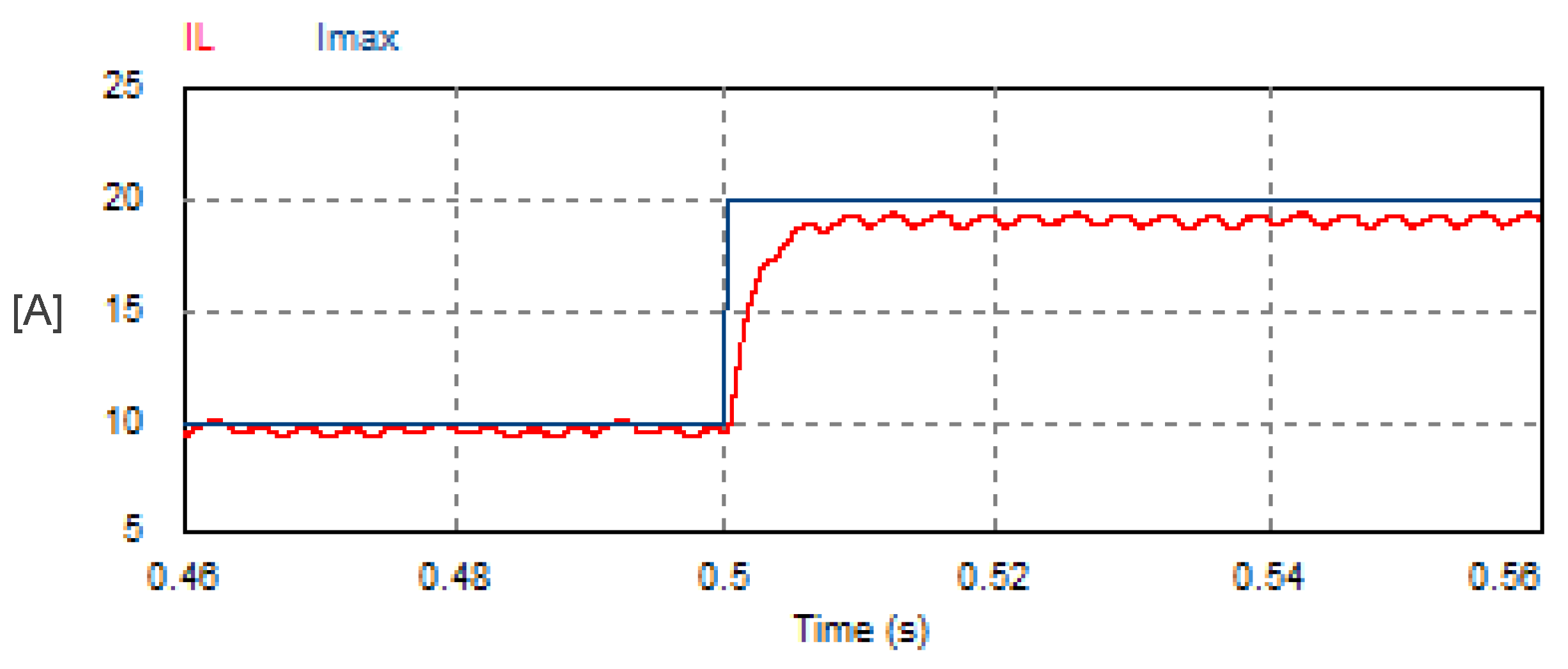

The USMR system, controlled by a triangular carrier-based PWM, was studied under a step change of reference AC currents from 10 A to 20 A. The carrier frequency was set at 10 kHz. The AC grid currents were well controlled to the desired peak values (10 A, then 20 A) as shown in Figure 23.

Figure 23.

Transient response of the AC currents with USMR under triangular carrier-based PWM.

The reference amplitude (peak value) of the AC currents and the corresponding actual DC link current are plotted in Figure 24. It is obvious that the DC link current responds to the step changes in the AC grid current.

Figure 24.

Transient response of the reference peak value of the AC currents and the corresponding DC link current of USMR with the triangular carrier-based PWM technique.

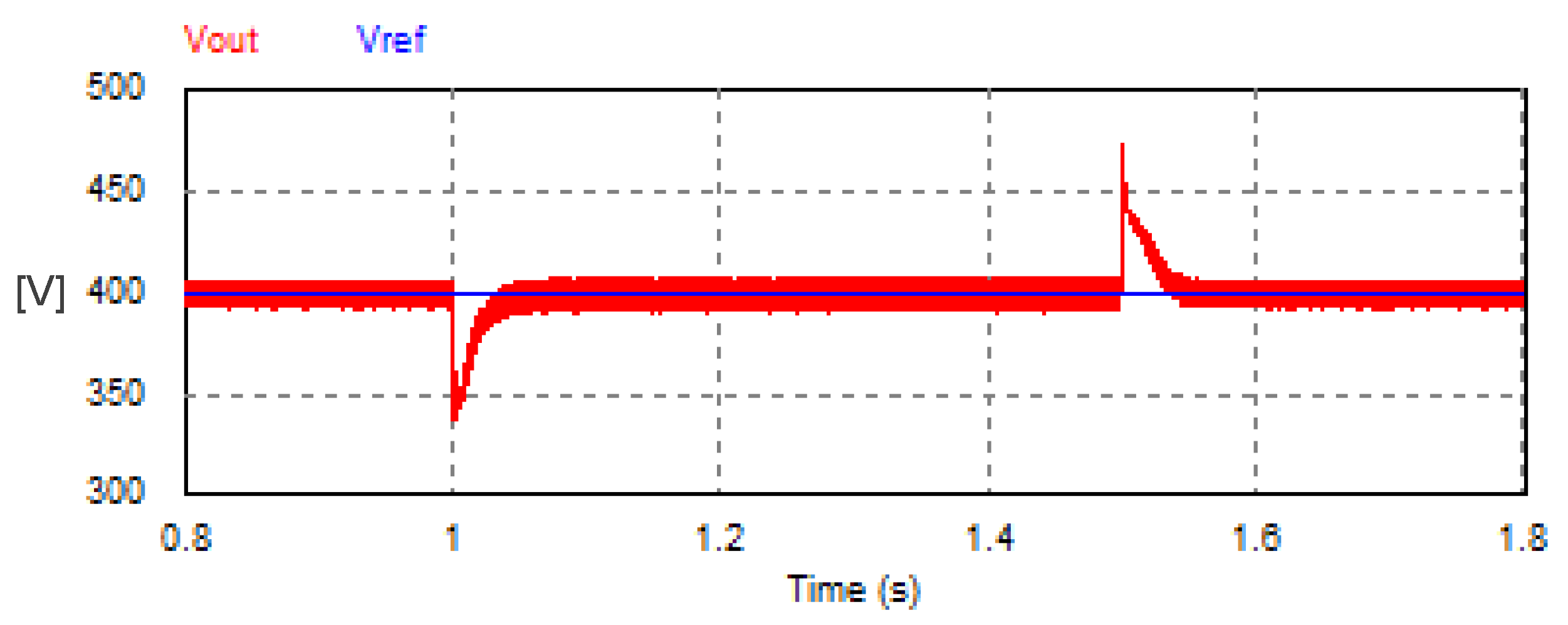

4.2.3. Closed-Loop DC Voltage Control Mode

The closed-loop control of the DC load voltage was elaborated with the USMR driven by the triangular carrier-based PWM modulation. Figure 25 demonstrates the transient step response when the set point of the load voltage changed from 200 V to 400 V. The settling time of the load voltage response was approximately 0.0082 s, similar to that obtained by the hysteresis current controller. The corresponding three-phase AC grid currents are plotted in Figure 26.

Figure 25.

Step response of the DC link voltage of USMR with triangular carrier-based PWM technique.

Figure 26.

Corresponding AC currents with USMR under triangular carrier-based PWM technique.

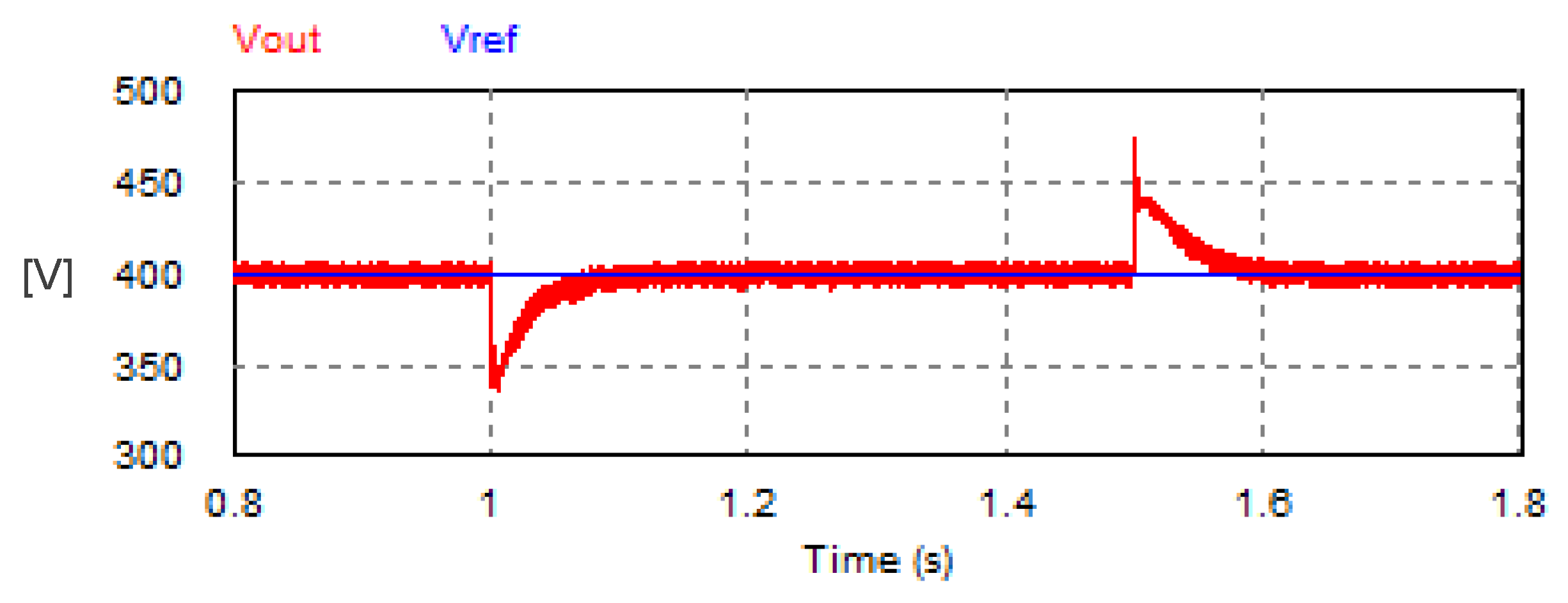

The transient response of the DC load voltage under a sudden change in the load was investigated. The load changed suddenly from 20 W to 16.67 W at time t = 1 s. Then, the additional load was removed suddenly at time t = 1.5 s. The resultant waveform of the DC load voltage is plotted in Figure 27. The results indicate that the DC voltage control loop succeeded in returning the DC load voltage to the reference value within 0.078 s, when the load increased. The worst transient dip in load voltage was 15.75% of the average load voltage. When the additional load was removed, the transient jump in the DC voltage was 18.5% of the average load voltage. The DC voltage control loop succeeded again in returning the DC load voltage to the set point within approximately 0.08 s, similar to that obtained by the hysteresis current controller.

Figure 27.

Transient response of the DC link voltage with triangular carrier-based PWM technique under sudden load variation.

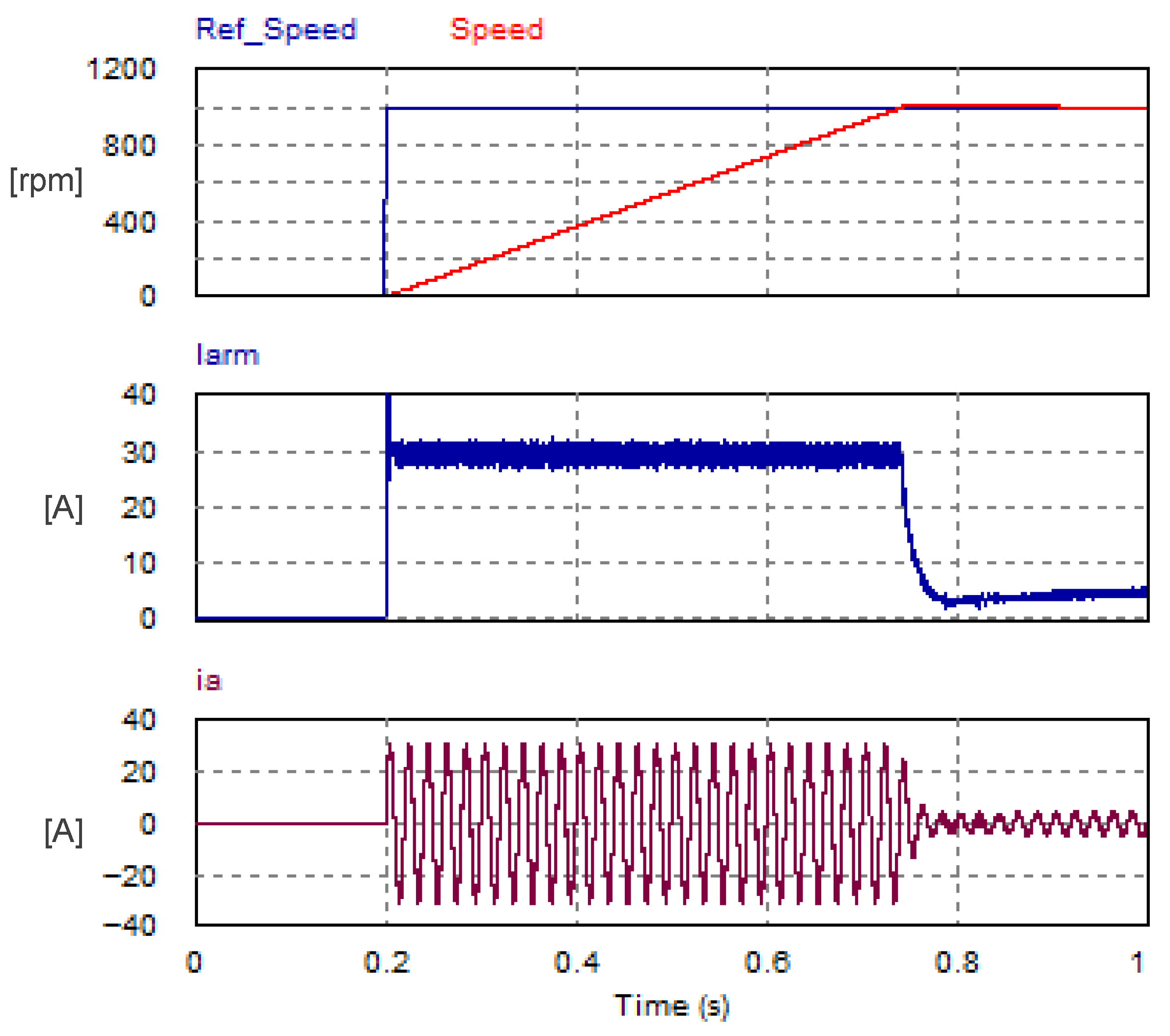

4.2.4. Closed-Loop Motor Speed Control

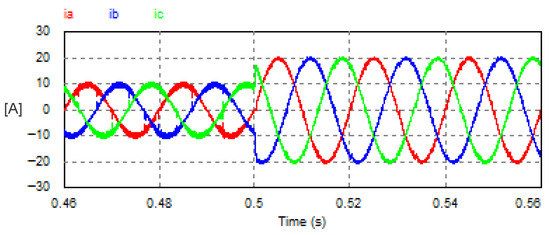

The USMR scheme with triangular carrier-based PWM control strategy was employed to control the speed of the separately excited DC motor. The step response of the mechanical speed is plotted in Figure 28. The motor was loaded with a fixed torque of 2 N.m. The set point was changed from 0 rpm to 1000 rpm. The speed settling time was approximately 0.59 s, while the peak overshoot was 18.6 rpm (1.86% of the set point). The corresponding armature current (Iarm) and AC grid current of phase a (ia) are also plotted in Figure 28.

Figure 28.

Step response of mechanical speed and the corresponding armature and ac currents with triangular carrier-based PWM technique.

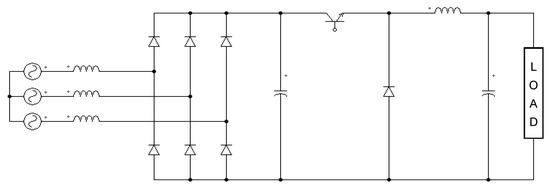

4.3. Comparison with the Conventional Buck Converter Scheme

Since the USMR is a unidirectional converter and permits operation in one quadrant only, the proposed USMR-based DC drive was compared with the conventional Buck chopper counterpart, which is also a one-quadrant DC drive and commonly used on a large scale due to simplicity and ease of control. The investigated conventional scheme is illustrated in Figure 29. To make a fair comparison between both systems, the buck chopper system was operated at the same operating conditions and under the ON–OFF current control mode, similar to the employed control scheme of the USMR system.

Figure 29.

Power circuit of the one-quadrant Buck converter.

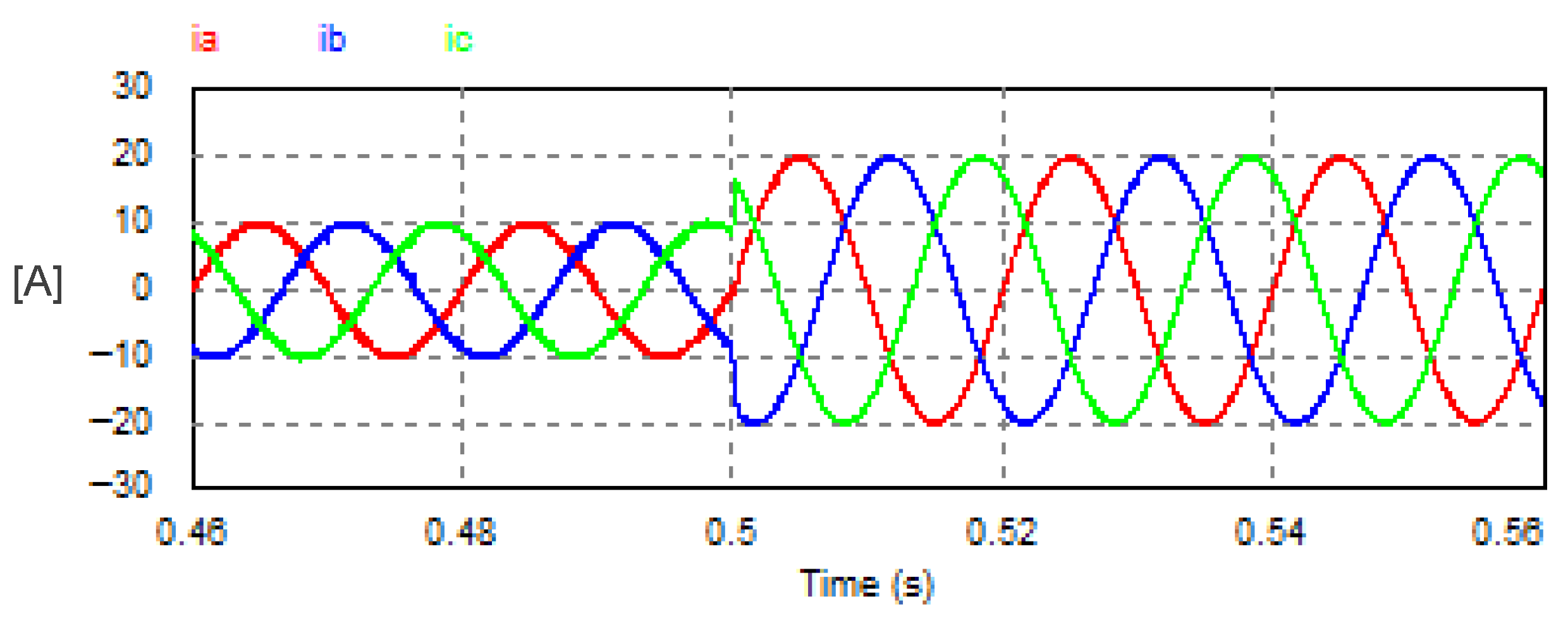

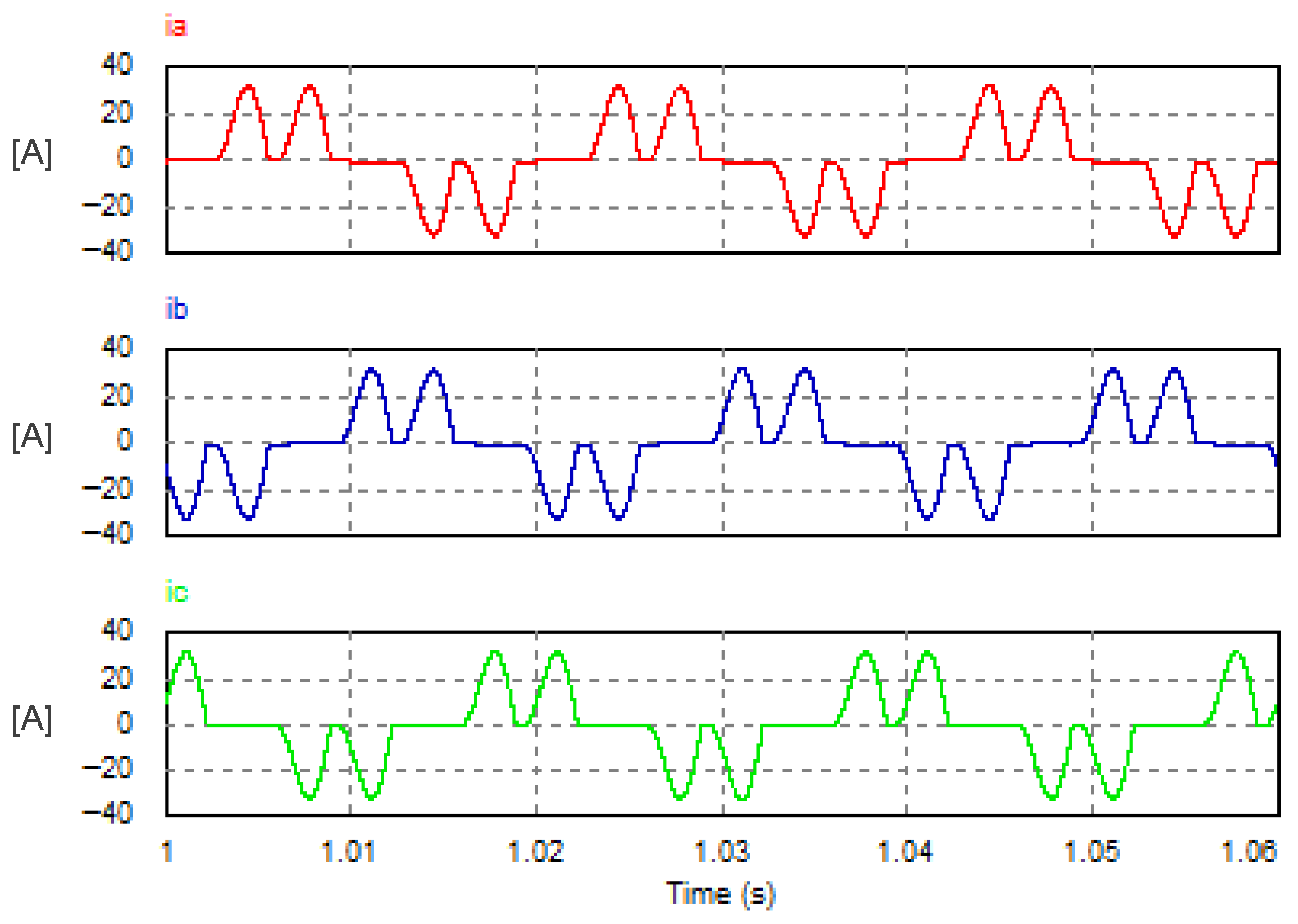

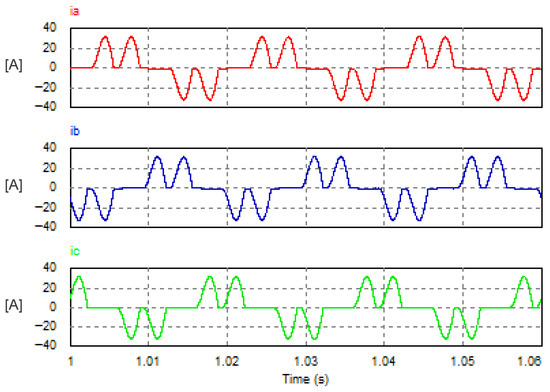

Although the operation and control of the Buck converter is simpler than the USMR, the power quality (in terms of PF and THD of the AC grid current) was worse than that achieved by the USMR. This is because the buck converter does not have any control over the current drawn from the AC mains. The AC currents with the Buck converter were pulsating and highly distorted, as illustrated in Figure 30. The resultant THD was high (79.6%).

Figure 30.

AC grid currents with Buck converter.

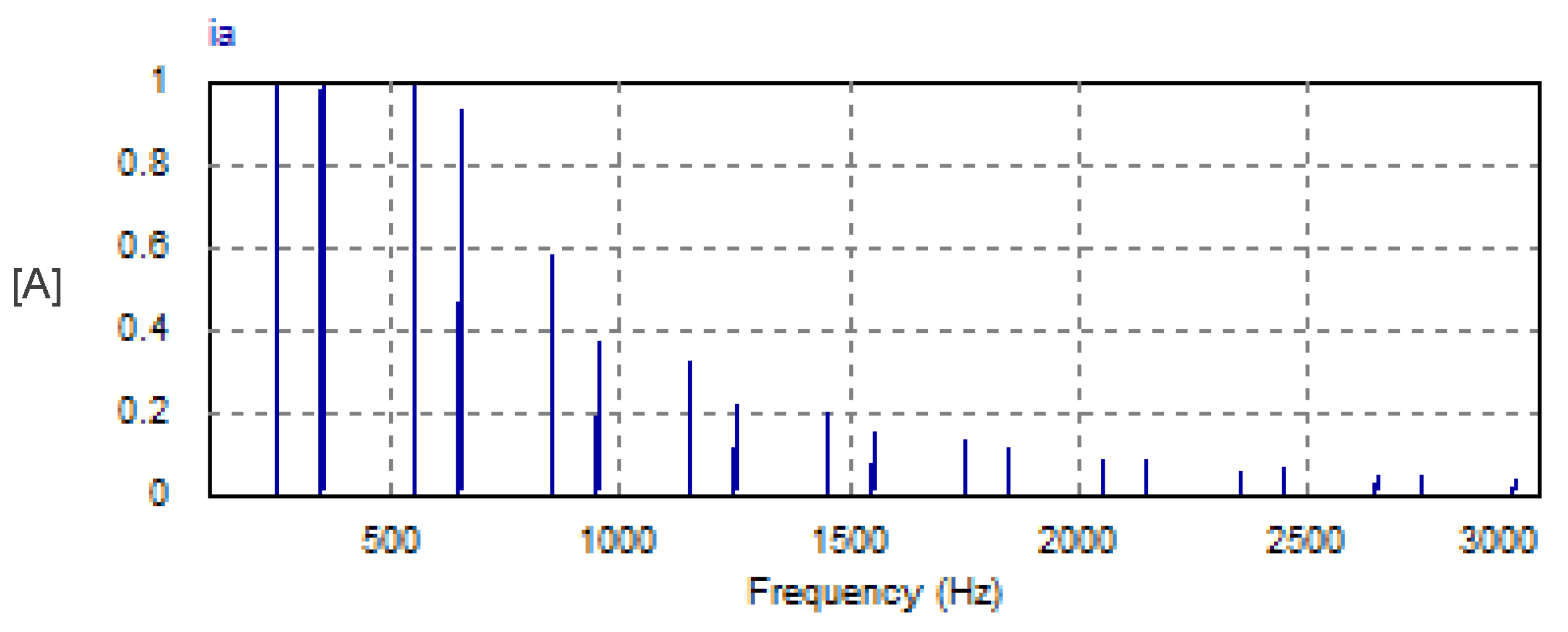

The corresponding harmonic spectrum of the AC phase current (ia) is depicted in Figure 31. The harmonic spectrum contains odd harmonics of order 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, etc., with relatively high amplitudes compared with that produced by the USMR converter under either an ON-OFF hysteresis current controller or triangular carrier-based PWM technique.

Figure 31.

Harmonic spectrum of AC current with Buck converter (zoomed to demonstrate the harmonic content).

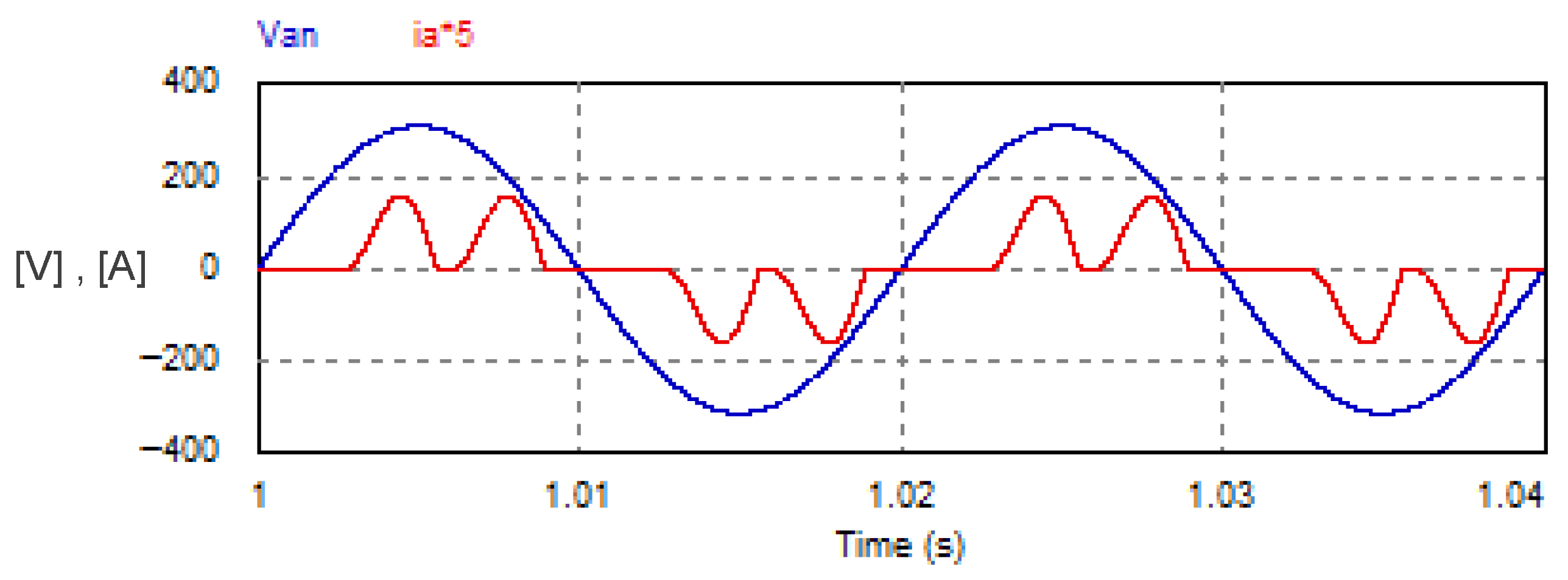

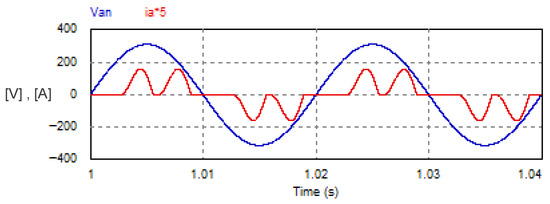

Moreover, the input PF was low because the AC currents (ia, ib, ic) were not precisely in phase with the corresponding AC phase voltages (van, vbn, vcn), as indicated in Figure 32, and also due to the high distortion factor of the AC currents. At these operating conditions, the measured PF was 0.742. The deteriorated power quality with the Buck converter system can be improved by adding a shunt active power filter scheme (SAPF) [45,46,47], which imposes a considerable additional cost on the overall cost of the DC drive.

Figure 32.

AC supply voltage van and AC supply current ia with Buck converter.

The step response of the motor mechanical speed with the Buck converter is plotted in Figure 33. Similar to the previously investigated methods with the USMR scheme, the speed set point was changed from 0 rpm to 1000 rpm. The speed response had a peak overshoot (22.2 rpm, which is 2.22% of the set point). The peak overshoot was almost equal to that achieved with the USMR converter driven by a hysteresis current controller. The speed settling time was 0.687 s, which is slightly higher than that achieved with the USMR converter.

Figure 33.

Step response of motor mechanical speed with Buck converter under closed-loop control of motor speed (set point was changed from 0 rpm to 1000 rpm).

The summary of the quantitative comparison between both systems is presented in Table 3. The performance of the proposed USMR DC drive system outperformed the conventional scheme of the Buck converter in many aspects and parameters.

Table 3.

Quantitative assessment of both systems: USMR and Buck converter.

5. Discussion

USMR is a single-quadrant AC–DC converter that permits the flow of power in only one direction from the AC mains to the DC load. It is characterized by the inherent immunity to shoot through. In addition, it permits operation at unity PF and can result in near-sinusoidal input currents.

Therefore, this paper aimed to employ the USMR converter topology to achieve a high-performance one-quadrant DC drive suitable for pumping applications.

The control of USMR was elaborated using two switching strategies; the first technique was the hysteresis current control with a tolerance band to control the AC grid current, while the second technique was the triangular carrier-based PWM technique that operates at a well-defined carrier frequency (10 kHz). The obtained results demonstrated that both switching strategies are efficient and result in a high-performance DC drive.

Moreover, both schemes resulted in a near-unity input PF (0.999). The resultant AC currents drawn from the mains were near-sinusoidal, with satisfactory values of the THD (less than 2.75%). The transient responses with both schemes resulted in a peak overshoot of motor mechanical speed that did not exceed 2.5% in the worst case. Under a step change of the motor speed from zero rpm to 1000 rpm, the settling time was less than 0.6 s.

The obtained results are slightly in favor of the hysteresis current control, as shown in Table 3. However, the major drawback of the hysteresis current control method is the inability to operate at a constant switching frequency. In addition, the actual switching frequency is unpredictable, which complicates the design of the EMI filter. Conversely, the triangular carrier-based PWM technique leads to a constant and well-defined switching frequency, which is the frequency of the triangular carrier signal. Therefore, the design of the EMI filter is easier with the triangular carrier-based PWM technique.

Compared with the conventional Buck converter-based DC drive, which is also a single-quadrant DC drive, the resultant AC currents with the Buck converter are highly distorted, and the THD is high (79.6%). The harmonic spectrum contains odd harmonics of orders 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, etc., with relatively high amplitudes compared with the USMR converter. Also, the input PF is low (0.742) compared with that achieved by the USMR topology (0.999).

The simulation study was carried out using PSIM 9.1 software, which is considered one of the most confident and reliable tools for modeling and simulation of power electronics converters and systems. The author aims to verify the simulation results by experimental prototyping as a future work.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposed a high-performance one-quadrant DC drive based on a USMR converter topology. The USMR topology is convenient in some applications, such as EV battery chargers and pumping systems, where the power flow can be unidirectional.

The salient advantages of the proposed scheme are the operation at unity PF, low THD of the AC currents, and ease of control.

Two switching techniques were investigated in this paper. The first switching method was ON–OFF hysteresis current control with a tolerance band, while the second method was a triangular carrier-based PWM technique.

The obtained results with both switching strategies demonstrated their effectiveness in operating the USMR system successfully at different operating conditions. A high-performance DC drive was achieved under both PWM switching methods.

Owing to the obtained results, both controllers achieved similar results with slight differences. In other words, the employed switching controllers did not lead to huge differences in system performance indices, either those related to power quality issues (THD, harmonic content of AC currents, and PF) or those related to DC drive dynamic performance (peak overshoot or settling time and speed regulation). However, the main difference between the hysteresis current controller and the triangular carrier-based PWM controller was the resultant switching frequency.

In the case of a hysteresis current controller, the switching frequency is variable and not directly predictable. While in the case of the triangular carrier-based PWM method, the PWM modulator operates at a well-defined switching frequency, which is the frequency of the carrier signal. Thus, the EMI filter is easier to design in the case of a carrier-based PWM modulator.

The qualitative and quantitative assessments demonstrate that the USMR is a competitive and convenient topology for various single-quadrant applications where the power reversal to the AC mains is not needed.

The proposed USMR scheme outperformed the conventional Buck converter-based scheme (which is also a one-quadrant DC drive) in power quality issues such as operation at unity PF, low THD of the AC currents, and drawing near sinusoidal input currents.

The application area of the proposed scheme was not limited to single-quadrant DC drives, but it was extended to involve EV battery chargers. USMR can serve as a front-end rectifier in unidirectional On-Board Chargers (OBCs) used in EVs. Such chargers can be used for wall-mounted home charging; commercial EV chargers; and fleet charging for buses, trucks, and some industrial EVs.

Based on the key findings of the conducted study, the author aims to develop an experimental prototype, relying on a hardware-in-the-loop data acquisition card (HIL), as a potential future work.

The experimental test rig shall include the following essential parts:

- The USMR converter power circuit will be built based on IGBT power transistors and fast recovery power diodes.

- During the prototyping and testing phase, the commonly used dSPACE card (DS1104 controller boards) will be utilized for real-time simulation as a powerful HIL tool.

- For the final stage, as a candidate commercial product, the core of the control unit will be based on the ESP32 microcontroller card.

- Hall-effect current and voltage transducers will be needed to measure the AC grid currents, AC phase voltages, and the DC load voltage.

- An integrated protection scheme and automatic shut-down will be included to protect the USMR converter against overcurrent, overvoltage, and different faults.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| APF | Active power filter |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| DC | Direct current |

| DO | Dandelion optimization |

| FCS-MPC | Finite control set model predictive control |

| BJT | Bipolar junction transistor |

| IGBT | Insulated gate bipolar transistor |

| THD | Total harmonic distortion |

| MOSFET | Metal oxide field effect transistor |

| PF | Power factor |

| PWM | Pulse width modulation |

| PID | Proportional-integral-derivative |

| PI | Proportional-integral |

| SV | Space vector |

| SVM | Space vector modulation |

| MC | Matrix Converter |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| USMC | Ultra sparse matrix converter |

| USMR | Ultra-sparse matrix rectifier |

| List of Symbols | |

| Reference values of AC supply currents | |

| Instantaneous values of the actual AC supply currents | |

| Peak value of the reference supply current | |

| Average value of the DC link current (USMR output current) | |

| Instantaneous values of the 3-Φ AC supply phase voltages | |

| Instantaneous values of the 3-Φ AC supply line–line voltages | |

| Maximum value of the supply phase voltage | |

| RMS value of the supply phase voltage | |

| Global average value of USMR output voltage | |

| Average DC voltage over the switching period of the PWM | |

| Average DC voltage over the entire sector of 60° | |

| Sa, Sb, Sc | Switching signals of the transistors Ta, Tb, and Tc, respectively |

| Cs | Capacitance of the input LC filter |

| Ls | Inductance of the input LC filter |

| Ra | Armature winding resistance |

| La | Armature winding inductance |

| Rf | Field winding resistance |

| Lf | Field winding inductance |

| J | Motor moment of inertia |

| Motor torque constant | |

| Phase angle between input voltage and current in rad | |

| Electrical angle of the AC supply voltage in rad | |

| dab | Duty cycle of the effective vector along the axis vab |

| dac | Duty cycle of the effective vector along the axis vac |

| Transfer functions of the PI controller | |

| Closed-loop transfer function of the speed control loop | |

| Proportional-term gain of the PI speed controller | |

| Integral-term gain of the PI speed controller | |

| Damping ratio of the desired 2nd-order closed-loop system | |

| Natural frequency of the desired 2nd-order closed-loop system |

References

- Montoya-Acevedo, D.; Gil-González, W.; Montoya, O.D.; Restrepo, C.; González-Castaño, C. Adaptive Speed Control for a DC Motor Using DC/DC Converters: An Inverse Optimal Control Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 154503–154513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, E.; Bal, G.; Öztürk, N.; Bekiroglu, E.; Houssein, E.H.; Ocak, C.; Sharma, G. Improving speed control characteristics of PMDC motor drives using nonlinear PI control. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 9113–9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, M. A Review of Recent Trends in High-Efficiency Induction Motor Drives. Vehicles 2025, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Santana, E.; Iturralde Carrera, L.A.; Álvarez-Alvarado, J.M.; Aviles, M.; Rodríguez-Resendiz, J. Modeling and Control of a Permanent Magnet DC Motor: A Case Study for a Bidirectional Conveyor Belt’s Application. Eng 2025, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatullah, R.; Ak, A.; Serteller, N.F.O. SMC Controller Design for DC Motor Speed Control Applications and Performance Comparison with FLC, PID and PI Controllers. In Intelligent Sustainable Systems; Nagar, A.K., Singh Jat, D., Mishra, D.K., Joshi, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Afifa, R.; Ali, S.; Pervaiz, M.; Iqbal, J. Adaptive Backstepping Integral Sliding Mode Control of a MIMO Separately Excited DC Motor. Robotics 2023, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidya, D.; Dhopte, S.; Bhattacharjee, M. Sensing System Assisted Novel PID Controller for Efficient Speed Control of DC Motors in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2023, 7, 6000604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, N.L.; İnanç, N.; Lüy, M. Control and Performance Analyses of a DC Motor Using Optimized PIDs and Fuzzy Logic Controller. Results Control Optim. 2023, 13, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Chávez, R.E.; Silva-Ortigoza, R.; Hernández-Guzmán, V.M.; Marciano-Melchor, M.; Orta-Quintana, A.A.; García-Sánchez, J.R.; Taud, H. A Robust Sliding Mode and PI-Based Tracking Control for the MIMO “DC/DC Buck Converter–Inverter–DC Motor” System. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 119396–119408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Muñoz, H.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; Hoyos, F.E.; Rincón, A. Speed Regulation of a Permanent Magnet DC Motor with Sliding Mode Control Based on Washout Filter. Symmetry 2022, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesović, M.; Jovanović, R.; Trišović, N. Control of a DC motor using feedback linearization and the gray wolf optimization algorithm. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 16878132221085324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczmann, M. Review of DC Motor Modeling and Linear Control: Theory with Laboratory Tests. Electronics 2024, 13, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.A.A.; Elnady, A. Advanced Drive System for DC Motor Using Multilevel DC/DC Buck Converter Circuit. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 54167–54178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Shong, Y.; Qi, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Miao, Y.; Kong, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, B.; et al. Real-Time Global Optimal Energy Management Strategy for Connected Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Traffic Flow Information. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 20032–20042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Lan, P.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Peng, F.; Hong, J. Multi-U-Style Micro-Channel in Liquid Cooling Plate for Thermal Management of Power Batteries. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 256, 123984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std. 519-2022 (Revision of IEEE Standard 519-2014); IEEE Standard for Harmonic Control in Electric Power Systems. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–31. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std. 1459-2010; IEEE Standard Definitions for the Measurement of Electric Power Quantities Under Sinusoidal, Non-Sinusoidal, Balanced, or Unbalanced Conditions. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–40.

- IEEE Std. 1531-2020 (Revision of IEEE Std 1531-2003); IEEE Guide for the Application and Specification of Harmonic Filters. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–71. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, J.; Zhao, M. Grid-Voltage Sensorless Predictive Current Control of Three-Phase PWM Rectifier with Fast Dynamic Response and High Accuracy. CPSS Trans. Power Electron. Appl. 2023, 8, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhu, X.; Shan, J.; Kong, Z. Power Model Free Voltage Ripple Suppression Method of Three-Phase PWM Rectifier under Unbalanced Grid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 13799–13807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Si, T.; Sun, L.; Liu, B.; Li, Z. Linear Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Three-Phase Voltage-Source PWM Rectifier. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 45050–45060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, J.; Liu, J. Grid-Voltage Sensorless Model Predictive Control of Three-Phase PWM Rectifier under Unbalanced and Distorted Grid Voltages. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 8663–8672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, R.-J.; Yang, Y. Design of Backstepping Direct Power Control for Three-Phase PWM Rectifier. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 3160–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, X.; Hoang, T.T.G.; Wang, Z.; Tian, L. DC-Link Voltage Disturbance Rejection Strategy of PWM Rectifiers Based on Reduced-Order LESO. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 103693–103705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Shi, J.; Tan, L.; Zhang, C.; Hu, K. Study on PWM Rectifier without Grid Voltage Sensor Based on Virtual Flux Delay Compensation Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wu, Y.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. An Improved Precise Power Control of Voltage Sensorless-MPC for PWM Rectifiers. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 220058–220068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkia, H.A.; Adabi, J.; Zare, F. Elimination of Circulating Current in a Parallel PWM Rectifier Using an Interface Circuit. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z.; Xie, L.; Shuai, Z. Wideband dq-Frame Impedance Modeling of Load-Side Virtual Synchronous Machine and Its Stability Analysis in Comparison with Conventional PWM Rectifier in Weak Grid. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 9, 2440–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metidji, R.; Metidji, B.; Mendil, B. Design and Implementation of a Unity Power Factor Fuzzy Battery Charger Using an Ultrasparse Matrix Rectifier. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metidji, B.; Metidji, R. Unity Power Factor Standalone Wind Battery Charger. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Birmingham, UK, 20–23 November 2016; pp. 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Atia, Y.; Mahgoub, O. Ultra Sparse Matrix Rectifier for Battery Charging Application. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Advanced Control Circuits Systems (ACCS), Alexandria, Egypt, 5–8 November 2017; pp. 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, S.A.; Albalawi, H. Application of Model Predictive Control to Ultra Sparse Matrix Rectifier. Int. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2018, 13, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, J.W.; Baumann, M.; Schafmeister, F.; Ertl, H. Novel Three-Phase AC–DC–AC Sparse Matrix Converter—Part I: Derivation, Basic Principle of Operation, Space Vector Modulation, Dimensioning. In Proceedings of the Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, 2002. APEC 2002. Seventeenth Annual IEEE, Dallas, TX, USA, 10–14 March 2002; pp. 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, J.W.; Schafmeister, F.; Round, S.D.; Ertl, H. Novel Three-Phase AC–AC Sparse Matrix Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2007, 22, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Loh, P.C.; Blaabjerg, F. A Compact Three-Phase Single-Input/Dual-Output Matrix Converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 59, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Li, S.; Yan, Y.; Shi, T. Research on Linear Output Voltage Transfer Ratio for Ultra-Sparse Matrix Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 1811–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, W.; Yan, Y.; Shi, T.; Xia, C. A Multimode Space Vector Overmodulation Strategy for Ultrasparse Matrix Converter with Improved Fundamental Voltage Transfer Ratio. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 6782–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wu, L.; Yan, Y.; Xia, C. Harmonic Spectrum of Output Voltage for Space Vector Pulse Width Modulated Ultra Sparse Matrix Converter. Energies 2018, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, M.; Chauhan, A.K.; Singh, S.K. Extended Range of Ultra Sparse Matrix Converter Using Integrated Switched Capacitor Network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 5406–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, V.; Raghuram, M.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.K.; Siwakoti, Y.P. Switching Strategy to Reduce Inductor Current Ripple and Common Mode Voltage in Quasi Z-Source Ultra Sparse Matrix Converter. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2023, 4, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Zhang, X.; An, S.; Yan, Y.; Xia, C. Harmonic Suppression Modulation Strategy for Ultra-Sparse Matrix Converter. IET Power Electron. 2016, 9, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xia, C.; Yan, Y.; Shi, T. Space-Vector Overmodulation Strategy for Ultrasparse Matrix Converter Based on the Maximum Output Voltage Vector. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 5388–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, E.; Farasat, M.; Trzynadlowski, A.M. Matrix Converter with a Series Z-Source. In Proceedings of the IECON 2012—38th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 October 2012; pp. 6093–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Tepper, S.; Moran, L. Practical Evaluation of Different Modulation Techniques for Current-Controlled Voltage Source Inverters. IEE Proc.—Electr. Power Appl. 1996, 143, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buła, D.; Michalak, J.; Zygmanowski, M.; Adrikowski, T.; Jarek, G.; Jeleń, M. Control Strategy of 1 kV Hybrid Active Power Filter for Mining Applications. Energies 2021, 14, 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, M. Low-Cost Active Power Filter Using Four-Switch Three-Phase Inverter Scheme. Electricity 2025, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi Jafrodi, S.; Ghanbari, M.; Mahmoudian, M.; Najafi, A.M.G.; Rodrigues, E.; Pouresmaeil, E. A Novel Control Strategy to Active Power Filter with Load Voltage Support Considering Current Harmonic Compensation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).