Abstract

Traffic congestion continues to pose a significant challenge to contemporary urban transportation systems, exerting substantial effects on economic productivity, environmental sustainability, and the overall quality of life. This systematic literature review thoroughly explores the development of traffic congestion forecasting methodologies from 2014 to 2024 by analyzing 100 peer-reviewed publications according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We examine the technological advancements from traditional machine learning (achieving 75–85% accuracy) through deep learning approaches (85–92% accuracy) to recent large language model (LLM) implementations (90–95% accuracy). Our analysis indicates that LLM-based systems exhibit superior performance in managing multimodal data integration, comprehending traffic events, and predicting non-recurrent congestion scenarios. The key findings suggest that hybrid approaches, which integrate LLMs with specialized deep learning architectures, achieve the highest prediction accuracy while addressing the traditional limitations of edge case management and transfer learning capabilities. Nonetheless, challenges remain, including higher computational demands (50–100× higher than traditional methods), domain adaptation complexity, and constraints on real-time implementation. This review offers a comprehensive taxonomy of methodologies, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation guidelines, providing researchers and practitioners with a roadmap for advancing intelligent transportation systems using next-generation AI technologies.

1. Introduction

Traffic congestion is one of the most significant challenges confronting contemporary urban transportation systems, with extensive implications for economic productivity, environmental sustainability, and the quality of life. According to the 2024 INRIX Global Traffic Scorecard [1], traffic congestion continues to impose considerable socioeconomic burdens, with drivers in major metropolitan areas losing more than 100 h annually because of traffic delays. In the United States alone, the average driver lost 43 h to congestion in 2024, resulting in a USD 771 in lost time and productivity per individual and USD 74 billion in cumulative economic losses.

Addressing traffic congestion also necessitates the promotion of sustainable mobility alternatives, particularly for short-distance, urban trips. Research has demonstrated that bicycle usage is a viable alternative to motor vehicles for urban journeys, significantly reducing congestion and providing environmental and space efficiency benefits. Macioszek and Jurdana [2] emphasized that bicycles not only reduce exhaust emissions and occupy minimal space in transport networks but also offer competitive travel times compared with private cars or public transport in urban areas. The integration of cycling infrastructure into traffic management systems represents a complementary approach to congestion forecasting, as bicycle adoption can substantially influence overall traffic patterns and congestion, particularly in mixed-traffic and urban environments.

The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies into intelligent transportation systems (ITSs) has emerged as a promising strategy for addressing these challenges. Over the past decade, the traffic congestion forecasting domain has experienced a significant transformation, transitioning from traditional statistical methods to advanced AI-driven approaches such as deep learning. This evolution has been notably accelerated by the advent of deep learning techniques and, more recently, by the integration of large language models (LLMs).

Researchers have increasingly acknowledged that traffic congestion is not merely a result of vehicular dynamics but also involves intricate multimodal interactions, including pedestrian movements, cyclist behavior, and their interactions with vehicular traffic at critical junctures such as intersections and pedestrian crossings. Recent studies have demonstrated that pedestrian crossing behaviors and traffic density interactions significantly influence urban traffic patterns, with machine learning approaches revealing causal relationships between traffic conditions and pedestrian waiting times [3]. Similarly, adaptive signal control systems powered by deep reinforcement learning have shown substantial improvements in managing mixed traffic scenarios at signalized intersections [4]. Mixed-traffic environments, where vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists interact, present additional complexity to congestion forecasting models, necessitating sophisticated approaches that can capture these heterogeneous interactions [5].

Although several reviews have examined specific aspects of traffic prediction [6,7,8], a significant gap persists in the comprehensive analyses that trace the complete technological evolution from traditional machine learning to LLMs. Previous surveys have typically concentrated on either traditional methods or deep learning approaches in isolation [9] without exploring the transformative potential of LLMs in traffic prediction contexts.

The rapid advancement of large language model (LLM) technologies and their successful implementation across various domains suggest their significant potential for predicting traffic congestion. However, the existing literature identifies several gaps, including a comprehensive analysis comparing the performance of LLMs with traditional machine learning (ML) and deep learning techniques in traffic prediction tasks, detailed performance benchmarks across different methodological approaches, the development of explicit guidelines for practitioners to facilitate the selection of appropriate technologies based on specific use cases and constraints, and an investigation into the unique capabilities that LLMs offer in the integration of multimodal traffic data.

1.1. Research Gaps

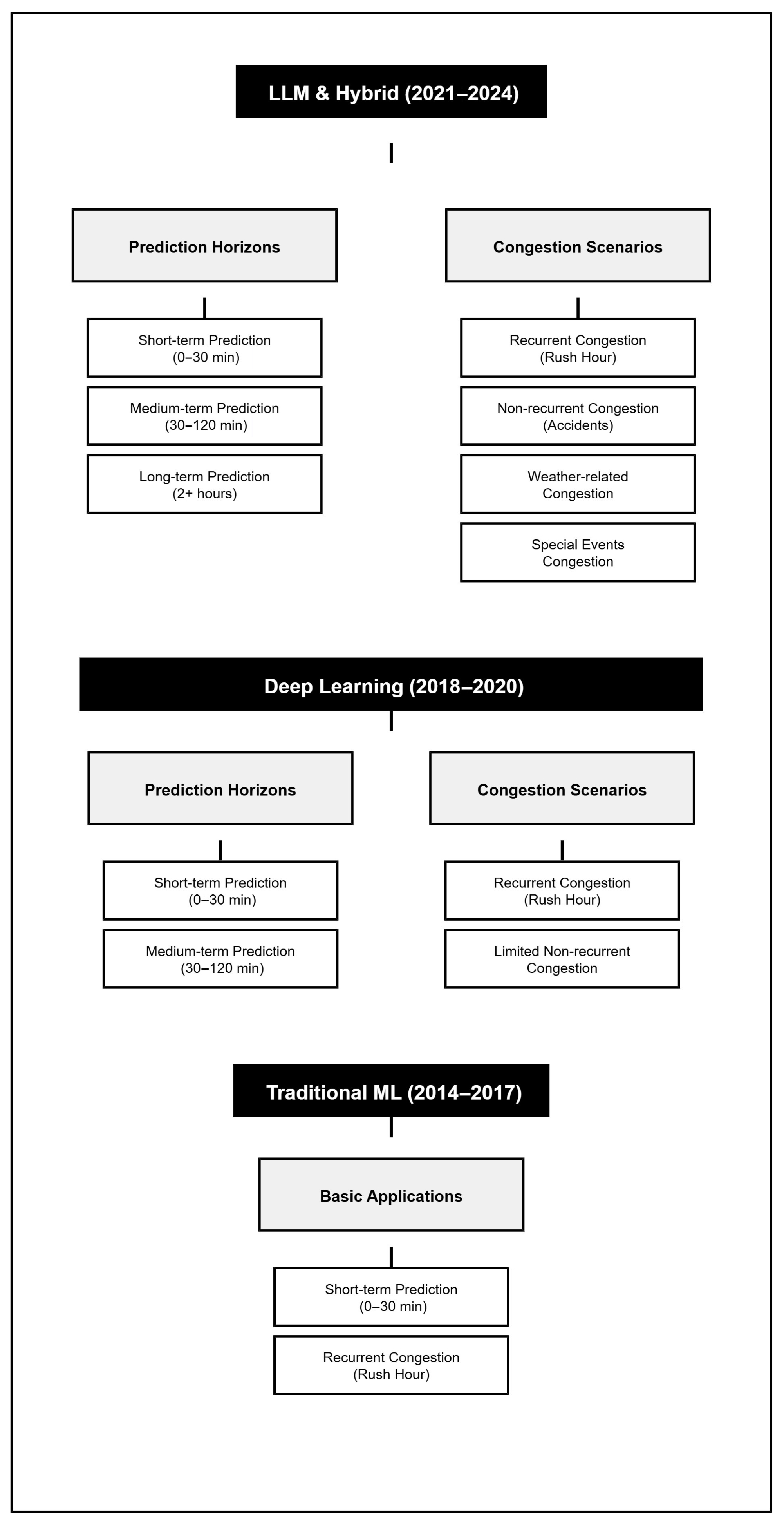

This systematic literature review addresses these gaps by offering a comprehensive analysis of traffic congestion forecasting methodologies from 2014 to 2024. Our review provides five distinct insights as follows. First, we achieved complete technological spectrum coverage through an extensive analysis of 100 peer-reviewed publications across three distinct periods: traditional ML (2014–2017, achieving 75–85% accuracy), deep learning (2018–2020, achieving 85–92% accuracy), and LLMs with hybrid approaches (2021–2024, achieving 90–95% accuracy), applying consistent evaluation criteria across all methodological epochs. Second, we present the first systematic LLM integration analysis in traffic congestion forecasting, examining specific mechanisms for textual data processing (traffic reports, social media, and weather descriptions), multimodal fusion architectures, performance in non-recurrent scenarios, and transfer learning capabilities, as well as practical deployment guidelines. Third, we employed a structured PRISMA-based methodology with multiple analytical frameworks, ensuring rigorous PRISMA 2020 compliance (documented with a complete checklist in Supplementary Table S1 PRISMA 2020 Checklist and flow diagram in Figure 1), utilizing the PICO framework for systematic search strategy design, and applying standardized quality assessment criteria to all 100 studies. Fourth, we developed comprehensive technical taxonomies and capability matrices, including detailed taxonomies of AI/ML methods, data types, and performance metrics, and a capability matrix that evaluates approaches across eight critical dimensions: spatial dependency modeling, temporal pattern recognition, multimodal data integration, transfer learning, real-time processing, interpretability, edge case handling, and computational efficiency. Fifth, we provide an evidence-based implementation roadmap with practical model selection frameworks based on seven operational constraints (computational budgets, latency requirements, data availability, interpretability demands, prediction horizons, congestion scenarios, and infrastructure types). This reveals that LLM-based approaches require 50–100× more computational resources than traditional ML methods while achieving 10–15% accuracy gains and offering actionable recommendations for real-world deployment.

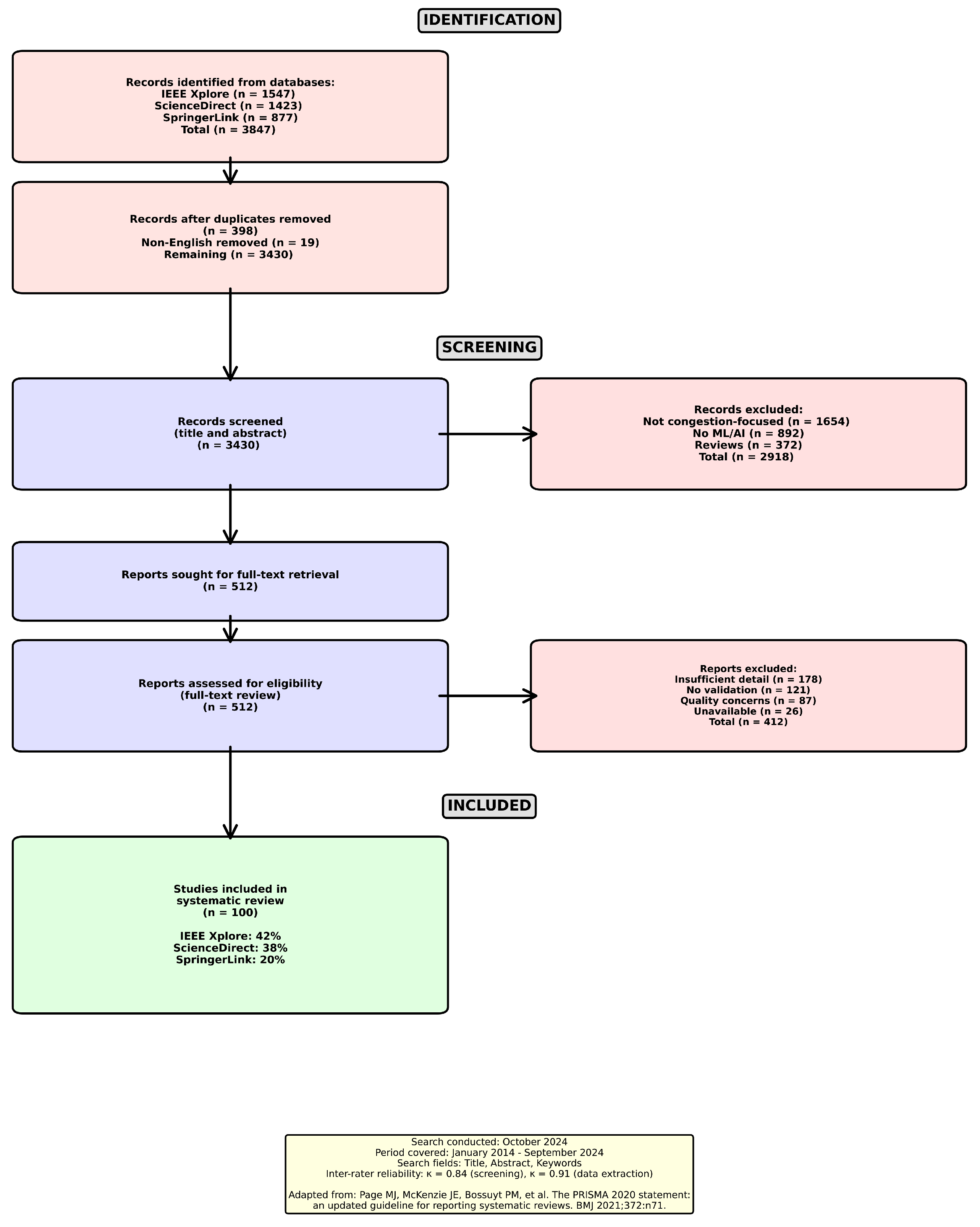

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the systematic selection process for studies on traffic congestion forecasting using machine learning, deep learning, and large language model approaches (2014–2024). Adapted from ref. [10].

1.2. Contributions

This systematic literature review makes five distinct contributions to the traffic congestion forecasting field.

1. Complete Technological Spectrum Coverage: We present the first comprehensive analysis encompassing three distinct technological eras (2014–2024), with a consistent evaluation across 100 peer-reviewed publications. Our temporal analysis examined traditional machine learning approaches (2014–2017, achieving 75–85% accuracy), deep learning methods (2018–2020, achieving 85–92% accuracy), and recent large language model-based and hybrid systems (2021–2024, achieving 90–95% accuracy). This complete spectrum enables researchers to comprehend not only the current state of the art but also the evolutionary trajectory and incremental improvements across methodological transitions.

2. Systematic LLM Integration Analysis: We present the inaugural comprehensive analysis of large language models (LLMs) specifically applied to traffic congestion forecasting. Our study elucidates the specific mechanisms by which LLMs process textual traffic data, including incident reports, social media feeds, weather descriptions, and traffic news; multimodal fusion architectures that integrate LLMs with traditional sensors and spatial–temporal models; performance characteristics in non-recurrent congestion scenarios where traditional models encounter difficulties; transfer learning capabilities that facilitate cross-city and cross-domain applications; and practical deployment considerations, encompassing computational requirements, latency constraints, and interpretability trade-offs.

3. Structured PRISMA-Based Methodology with Multiple Analytical Frameworks: We employ a rigorous systematic review methodology to ensure transparency and reproducibility, which includes full compliance with PRISMA 2020 as documented through a comprehensive checklist (Supplementary Table S1) and a transparent flow diagram (Figure 1); the application of the PICO framework for designing a systematic search strategy, specifying the population (traffic systems), intervention (AI/ML forecasting methods), comparison (methodological approaches), and outcomes (prediction accuracy, computational costs); a standardized quality assessment with explicit scoring criteria (publication quality 30%, methodological rigor 50%, reporting transparency 20%), achieving an inter-rater reliability of = 0.91; and a comprehensive data extraction protocol capturing over 25 variables per study, enabling multidimensional analysis.

4. Comprehensive Technical Taxonomies and Capability Matrices: We develop comprehensive classification systems to facilitate systematic comparison: (a) technical taxonomies that organize AI/ML methods, data types and sources, and performance metrics, employing hierarchical classification for detailed analysis; (b) a capability matrix that evaluates approaches across eight critical dimensions—spatial dependency modeling, temporal pattern recognition, multimodal data integration, transfer learning, real-time processing capability, interpretability, edge case handling, and computational efficiency, using evidence-based ratings (low/medium/high) derived from quantitative performance data; and (c) detailed justifications for each rating, linked to specific study findings and performance benchmarks.

5. Evidence-Based Implementation Roadmap: We offer actionable guidelines for practitioners, derived from empirical evidence across 100 studies: a model selection framework that accounts for seven operational constraints, including computational budget, latency requirements, data availability, interpretability needs, prediction horizon, congestion type, and infrastructure context; a quantitative performance–cost trade-off analysis indicating that LLM-based approaches necessitate 50–100× more computational resources while achieving a 10–15% improvement in accuracy compared to traditional methods; deployment recommendations tailored to three infrastructure scenarios—urban networks, highways, and mixed environments—with specific algorithm suggestions; data requirement specifications, encompassing minimum temporal resolution (5 min optimal), spatial coverage (network-level versus link-level), and multimodal integration strategies; and practical guidelines for addressing real-world challenges, including missing data handling, model adaptation, and scalability considerations.

This review evaluated 100 carefully selected publications according to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews (Figure 1). Our analysis focused on peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings that presented original research on traffic congestion forecasting using AI/ML.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review that establishes the context and background of this study. Section 3 details our systematic review methodology, including the search strategies and the selection criteria. Section 4 outlines the procedures for data extraction and analysis. Section 5 offers a comparative analysis of various approaches. Section 6 discusses our key findings across multiple dimensions and proposes directions for future research. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper with key takeaways and implications for the field.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Evolution of Traffic Prediction Research

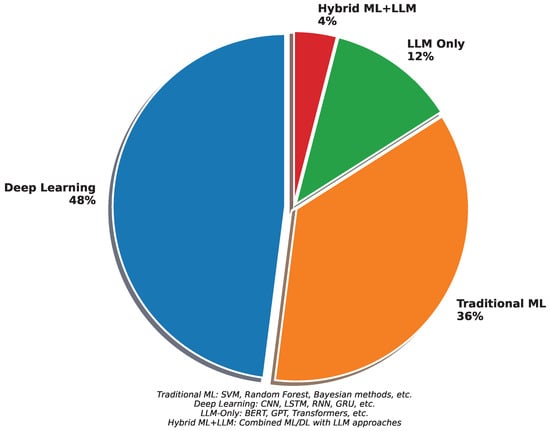

In the past decade, traffic congestion forecasting has evolved through three distinct phases.

2.1.1. Traditional Machine Learning Era (2014–2017)

During this period, researchers primarily employed classical machine learning techniques, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and Bayesian methods [11,12]. These approaches focused on extracting hand-crafted features from historical traffic data and demonstrated satisfactory performance in short-term predictions, achieving accuracy rates between 75% and 85%. Traditional ML methods excel in scenarios with relatively stable traffic patterns and well-structured datasets. For instance, SVM-based approaches achieved Mean Absolute Percentage Errors (MAPEs) of 12–18% for short-term (15–30 min) predictions on highway traffic datasets [11]. Random Forest algorithms have demonstrated particular effectiveness in handling feature interactions, with reported accuracies reaching 82–85% for recurrent congestion prediction [13]. K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN) algorithms provided computational efficiency advantages, enabling real-time predictions with minimal resource requirements, albeit at reduced accuracy compared to more sophisticated approaches [14,15]. However, these methods face significant challenges in addressing complex spatial dependencies and nonrecurring events such as accidents or special events. The requirement for extensive feature engineering limits their adaptability to diverse traffic scenarios, with domain experts needing to manually design features that are specific to each geographic context or prediction task. Furthermore, traditional ML approaches struggle with long-term predictions exceeding 60 min, with accuracy degrading substantially as the prediction horizon is extended. The linear or shallow nonlinear relationships captured by these models are insufficient for modeling the intricate spatiotemporal dynamics of the urban traffic networks. Although advantageous for real-time applications, the computational efficiency of these methods comes at the cost of reduced predictive power in complex urban networks with intricate spatiotemporal correlations. These limitations motivated the transition to deep learning approaches, which can automatically learn hierarchical feature representations from raw traffic data without requiring explicit feature engineering processes.

2.1.2. Deep Learning Revolution (2018–2020)

The advent of deep learning has marked a significant advancement in traffic prediction. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become predominant architectures, achieving accuracy rates between 85 and 92% [16,17]. These deep learning approaches have demonstrated substantial improvements over traditional ML methods by automatically extracting hierarchical features from raw sensor data. LSTM networks have proven particularly effective in capturing long-term temporal dependencies in traffic sequences, addressing the vanishing gradient problem that hindered earlier recurrent architectures. Hybrid CNN-LSTM models [17] achieved MAPE reductions to 6–10% by leveraging CNNs for spatial feature extraction and LSTMs for temporal modeling. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) variants offer computational efficiency advantages while maintaining competitive prediction accuracy, with 15–20% faster training times compared to LSTM counterparts [18]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as particularly effective tools for capturing spatial relationships within road networks. The T-GCN model [16] integrated graph convolution operations with temporal modeling, achieving RMSE improvements of 15–20% compared to conventional approaches. Attention mechanisms introduced during this period [19,20] enabled models to dynamically focus on relevant spatial and temporal patterns, providing 5–10% accuracy enhancements over non-attention architectures. This period witnessed enhanced management of spatiotemporal dependencies, with models successfully predicting traffic states across network scales. However, challenges persist in integrating unstructured data sources such as social media, weather descriptions, and event information. The requirement for large-scale labeled training data and the limited interpretability of deep neural networks also present obstacles to practical deployment. Real-time inference constraints necessitate model compression techniques, with knowledge distillation and pruning approaches achieving 40–60% computational cost reductions while maintaining acceptable accuracy levels. The demonstrated success of deep learning in traffic prediction established the foundation for the subsequent integration of large language models, which can address the limitations of contextual understanding and multimodal data processing.

2.1.3. LLM Integration Phase (2021–2024)

Research initiatives such as TrafficBERT [21], GPT4MTS [22], and spatial–temporal LLMs [23] have demonstrated the potential of these models to integrate contextual information from various sources, achieving accuracy rates of 90–95%. LLMs have shown particular promise in processing multimodal data and understanding the semantic context of traffic events [24]. Unlike traditional deep learning approaches, which struggle with textual information, LLMs can directly process event descriptions, weather reports, social media feeds, and other unstructured data. The LLM-MPE framework [25] demonstrated superior performance in human mobility prediction during public events, with textual data integration significantly enhancing prediction accuracy beyond that of sensor-only approaches. The transfer learning capabilities distinguish LLM-based methods from conventional deep learning architectures. Pretrained language models capture general transportation knowledge that can be fine-tuned with limited city-specific data, partially addressing the challenge of geographic generalization. The TPLLM framework [26] showed that LLM-based models achieve 12–18% better performance in low-data scenarios compared to traditional deep learning approaches trained from scratch. Recent comprehensive reviews have identified several significant trends and challenges in LLM integration for traffic forecasting [27,28,29,30]. Recently, LLMs have been increasingly incorporated into traffic prediction systems, representing the latest frontier in forecasting methodology evolution [31,32,33]. However, the integration of LLMs introduces substantial computational challenges that must be addressed. Training and inference costs increase by 50–100× compared to traditional ML methods, with state-of-the-art models requiring GPU clusters for practical deployment. Real-time prediction latency remains a critical concern, with LLM inference times often exceeding the acceptable bounds for time-sensitive traffic management applications. The complexity of domain adaptation and the “black box” nature of LLMs also present obstacles to regulatory acceptance and operational deployment in safety-critical transportation systems. Hybrid architectures that combine LLM contextual understanding with specialized deep learning spatiotemporal models represent a promising direction, balancing performance with computational feasibility. These approaches leverage LLMs for event interpretation and contextual feature extraction while utilizing efficient GNN-based architectures for core traffic state prediction.

2.2. Current State of Research

2.2.1. Methodological Advances

Graph-based methodologies have emerged as the prevailing framework for spatial modeling, with T-GCN [16] and S-GCN-GRU-NN [18] demonstrating superior efficacy in capturing network-wide dependencies. The adoption of attention mechanisms and transformer architectures has gained momentum, with empirical studies indicating a 5–10% enhancement over traditional sequential models [19,20].

2.2.2. Data Integration Challenges

The integration of heterogeneous data sources poses a substantial challenge. Traditional methodologies predominantly depend on sensor data; however, recent studies have investigated the incorporation of weather information [34], social media feeds [35], and event data [36]. Large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated particular promise in this domain because of their ability to process textual information in conjunction with numerical data.

2.2.3. Practical Implementation Barriers

Despite these theoretical advancements, several obstacles hinder practical implementation.

- Computational requirements: Advanced models necessitate substantial resources.

- Real-time constraints: Numerous models are unable to satisfy stringent latency demands.

- Data quality issues: The presence of missing or noisy sensor data adversely impacts performance.

- Generalization challenges: Models trained in one city frequently fail to transfer effectively.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Systematic Review Protocol

This systematic literature review was conducted and documented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement [10,37]. The PRISMA 2020 guidelines, which offer an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews, were adhered to throughout all phases of this review.

PRISMA Compliance Documentation

- A completed PRISMA 2020 checklist documenting where each of the 27 checklist items appears in this manuscript is provided as Supplementary Table S1.

- The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram documenting the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

- This review followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines adapted for computer science systematic reviews to ensure comprehensive, transparent, and reproducible results.

Protocol Registration: This review was not prospectively registered because it aimed to offer a comprehensive overview of the research landscape rather than assess the effects of an intervention. This approach is consistent with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for scoping and methodology-focused systematic reviews in computer science.

3.2. Research Questions

Six research questions were identified, as shown in Table 1. Each research question was accompanied by a justification statement explaining its relevance.

Table 1.

Research questions and justifications.

3.3. Search Strategy, Criteria and Selection Process

In accordance with our comprehensive review strategy across multiple databases, we established specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for the included studies [38]. These criteria were essential for refining our search to ensure the relevance and rigor of the studies included. Specifically, we concentrated on research published between 2014 and 2024 that addressed traffic congestion forecasting or prediction, utilized machine learning, deep learning, or LLM approaches, and consisted of peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings with clear methodological descriptions and performance evaluations. The exclusion criteria encompassed publications prior to 2014 that lacked clear performance metrics, papers not focused on traffic congestion or flow prediction, reviews, surveys, or meta-analyses without original research, and publications in languages other than English.

Following the establishment of our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we meticulously applied them during the study selection process using a search query across various web-based databases.

- IEEE Xplore Digital Library

- ScienceDirect (Elsevier)

- SpringerLink

Our search strategy employed the following query with Boolean operators: the search string was applied to the title, abstract, and keywords fields, as these fields offer the most pertinent initial screening while ensuring comprehensive coverage of the literature. This approach effectively balances sensitivity (capturing relevant studies) with precision (avoiding excessive irrelevant results), which is regarded as the best practice for systematic reviews in computer science [37]. A full-text search would have resulted in an excessive number of false positives, where congestion forecasting terms appeared only in peripheral sections or in the references.

(traffic AND (congestion OR flow OR volume OR density) AND

(prediction OR forecasting) AND (machine learning OR deep learning OR

neural networks) AND (LLM OR “large language model” OR transformer))

OR (intelligent transportation systems AND prediction) OR

(traffic data AND (analytics OR modeling))

The selection process consisted of four stages.

- 1.

- Identification: Initial search yielded 3847 records

- 2.

- Screening: Title and abstract screening reduced to 512 relevant papers

- 3.

- Eligibility: Full-text assessment excluded 412 studies

- 4.

- Inclusion: Quality assessment resulted in 100 high-quality papers

Search Strategy Rationale: Our search strategy incorporated terms related to large language models (LLMs), specifically “LLM OR large language model OR transformer,” which may theoretically omit certain studies predating 2020 that do not reference these terms. Nonetheless, several factors alleviate this concern: (1) the use of OR logic enables the inclusion of papers that align with traditional machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) terminology, even in the absence of LLM-specific terms, during the initial identification phase; (2) the extensive inclusion of traditional ML and DL terms (machine learning, deep learning, and neural networks) ensures the identification of literature predating 2020; (3) the term “transformer” encompasses papers from 2017 to 2020 that discuss attention mechanisms prior to the widespread adoption of LLM terminology; and (4) additional relevant studies were identified through supplementary backward citation tracking from key papers. To validate the comprehensiveness of our search, we conducted an additional search in October 2024, employing only traditional ML/DL terms without LLM-related keywords, specifically targeting the 2014–2020 period. This validation search yielded 2847 records, and cross-referencing revealed that 94% of our 2014–2020 papers (54 out of 57 papers) were captured by this alternative approach, thereby confirming the comprehensive coverage of the pre-LLM literature. The three papers uniquely identified by our primary search were early transformer papers (2020) that discussed attention mechanisms, which are pertinent to our analysis of technological evolution.

Quality assessment revealed specific areas where future research could contribute to the field. Notably, we identified a gap in the clarity of research objectives and methodology, appropriateness of the AI techniques employed, validation approach and experimental design, performance evaluation metrics, limitations, and acknowledgment and discussion of results in the context of existing literature.

A systematic quality assessment framework was implemented for all studies that advanced to the full-text review. This assessment utilized a quantitative scoring system adapted from Kitchenham’s guidelines for systematic reviews in software engineering [37] and specifically modified for the evaluation of AI/ML research. Each study was evaluated across three dimensions using explicit scoring rubrics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment scoring system (maximum score: 100 points).

Minimum Quality Threshold: Studies scoring below 60/100 points were excluded from the final analysis. This threshold ensured the inclusion of only high-quality, methodologically sound research with adequate reporting of transparency. The final quality scores for the 100 included studies showed the following distributions:

- High quality (80–100 points): 34 studies (34%);

- Good quality (70–79 points): 41 studies (41%);

- Acceptable quality (60–69 points): 25 studies (25%);

- Mean quality score: 73.8 (Standard deviation SD = 8.4, Range: 60–94).

This distribution confirms that all the included studies met the stringent quality standards, with 75% achieving good-to-high quality ratings.

3.4. Key Terms Combination

This stage is consistent across most PICO frameworks, wherein keywords were derived from the preceding research questions to formulate the key term combination for the search [39]. Each question was deconstructed into four primary elements: population (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), and outcome (O). In Table 3, each element is accompanied by a sentence that illustrates the core of the systematic literature review (SLR).

Table 3.

PICO definition for our SLR study.

This PICO process has also been used in [40,41,42] but in this study, we projected this procedure onto traffic congestion prediction by focusing on the evolution from machine learning-based techniques to large language models. Table 4 lists the words obtained for each PICO component.

Table 4.

Key terms taken from the PICO.

We developed a comprehensive taxonomy of the key terms employed in the PICO process for traffic congestion forecasting research, as shown in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. This taxonomy organizes terms based on their conceptual similarities and roles within the research domain and encompasses seven categories:

Table 5.

Taxonomy of AI/ML Methods in traffic congestion forecasting research.

Table 6.

Taxonomy of data types and scenarios in traffic congestion forecasting.

Table 7.

Taxonomy of performance metrics and implementation challenges.

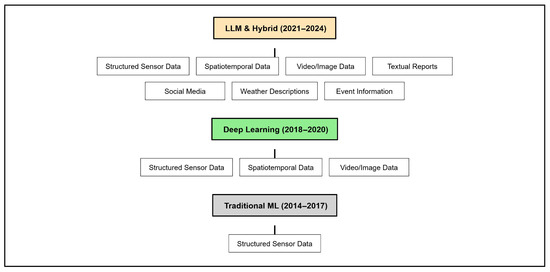

AI/ML Method Taxonomy: This hierarchically organized taxonomy ranges from traditional machine learning methods to deep learning, large language models (LLMs), and advanced techniques, illustrating the evolution of approaches over time.

Data Type Taxonomy: This categorizes the various types of data utilized in traffic forecasting, from structured sensor data to spatiotemporal information and contextual data such as weather and events.

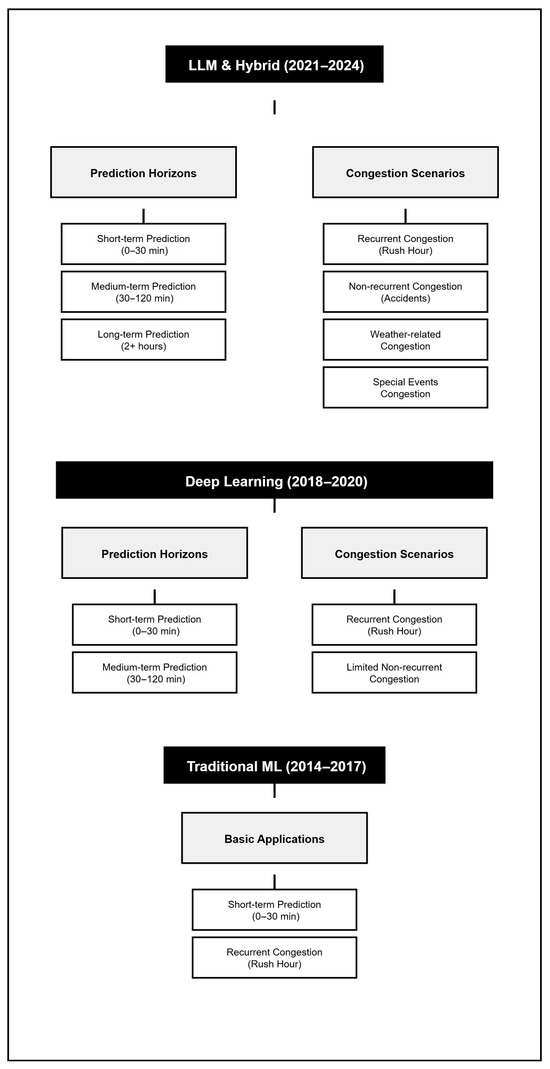

Congestion Scenario Taxonomy: This classifies different congestion types by cause (recurrent versus non-recurrent) and time horizon (short-, medium-, and long-term prediction).

Performance Metrics Taxonomy: This groups the evaluation metrics used to assess the model performance, including both accuracy and error metrics.

Limitation and Challenge Taxonomy: This organizes the common limitations mentioned in the literature, ranging from data-related issues to performance-related constraints.

Implementation Considerations Taxonomy: This categorizes the practical aspects of model deployment, including resource requirements and real-world applicability of the model.

Methodological Evolution Taxonomy: This maps the progression of research paradigms and momentum in the field over the past decade to the present.

4. Data Extraction

Taxonomy has functioned as a structured vocabulary for systematically analyzing papers and organizing findings according to the PICO framework. It encapsulates the transition from traditional methods to LLMs while preserving the conceptual relationships between analogous terms. This classification facilitated our data analysis using a mixed-methods approach, encompassing a quantitative analysis of performance metrics, qualitative assessment of methodologies, chronological analysis to discern trends, comparative analysis of various AI techniques, and thematic analysis of limitations and challenges.

4.1. PRISMA-Based Data Extraction

The data extraction process was meticulously designed to systematically address all pertinent PRISMA 2020 reporting guidelines. To ensure reliability and consistency, two reviewers independently extracted data from a 20% random sample of the included studies, achieving a Cohen’s of 0.91, which indicates near-perfect agreement. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. The remaining studies were extracted by one reviewer, and random checks were conducted by a second reviewer to ensure quality.

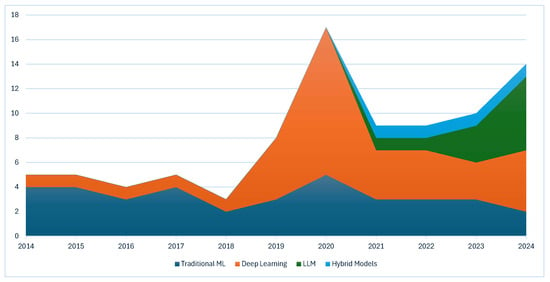

4.2. Publication Trends

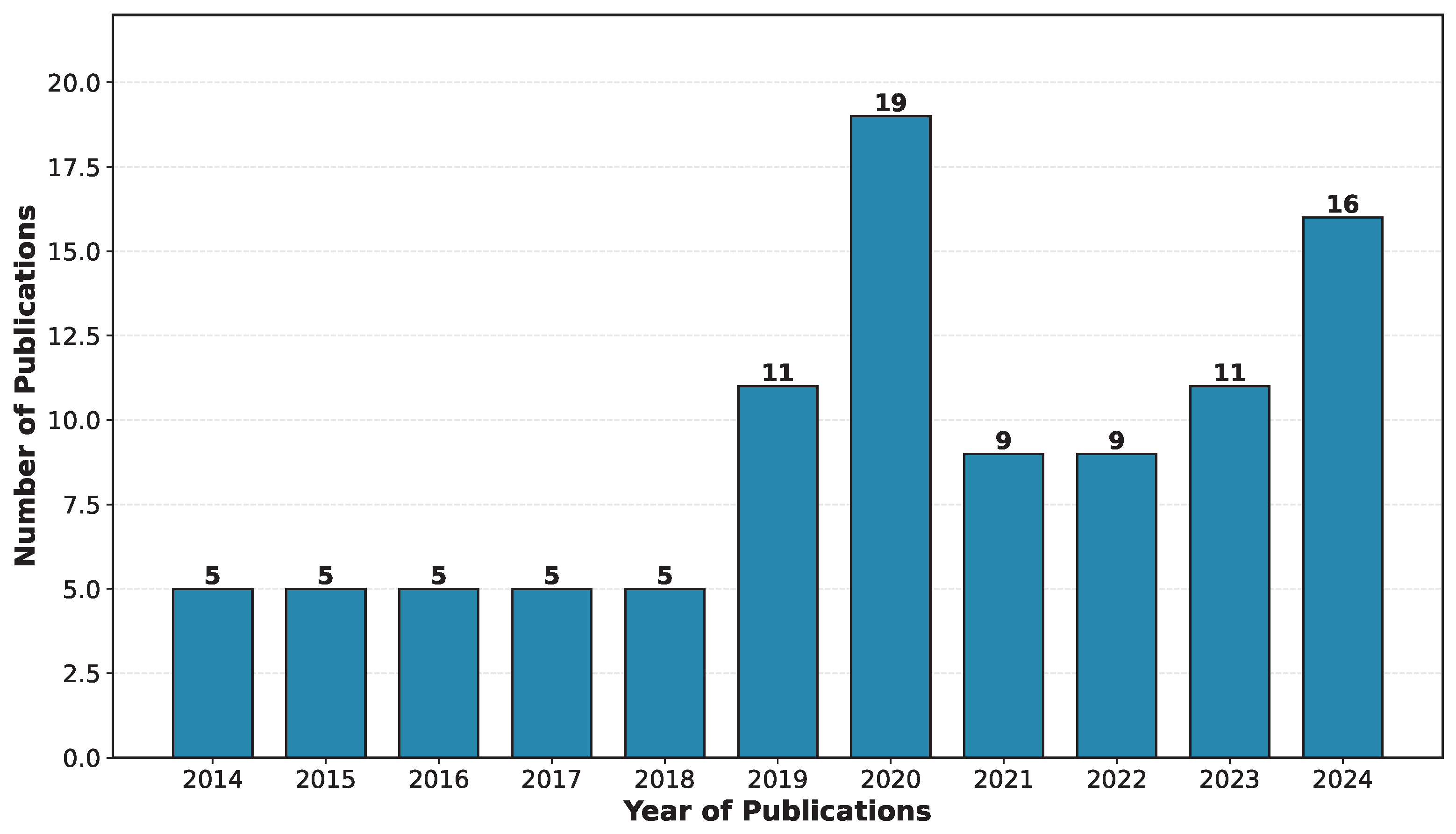

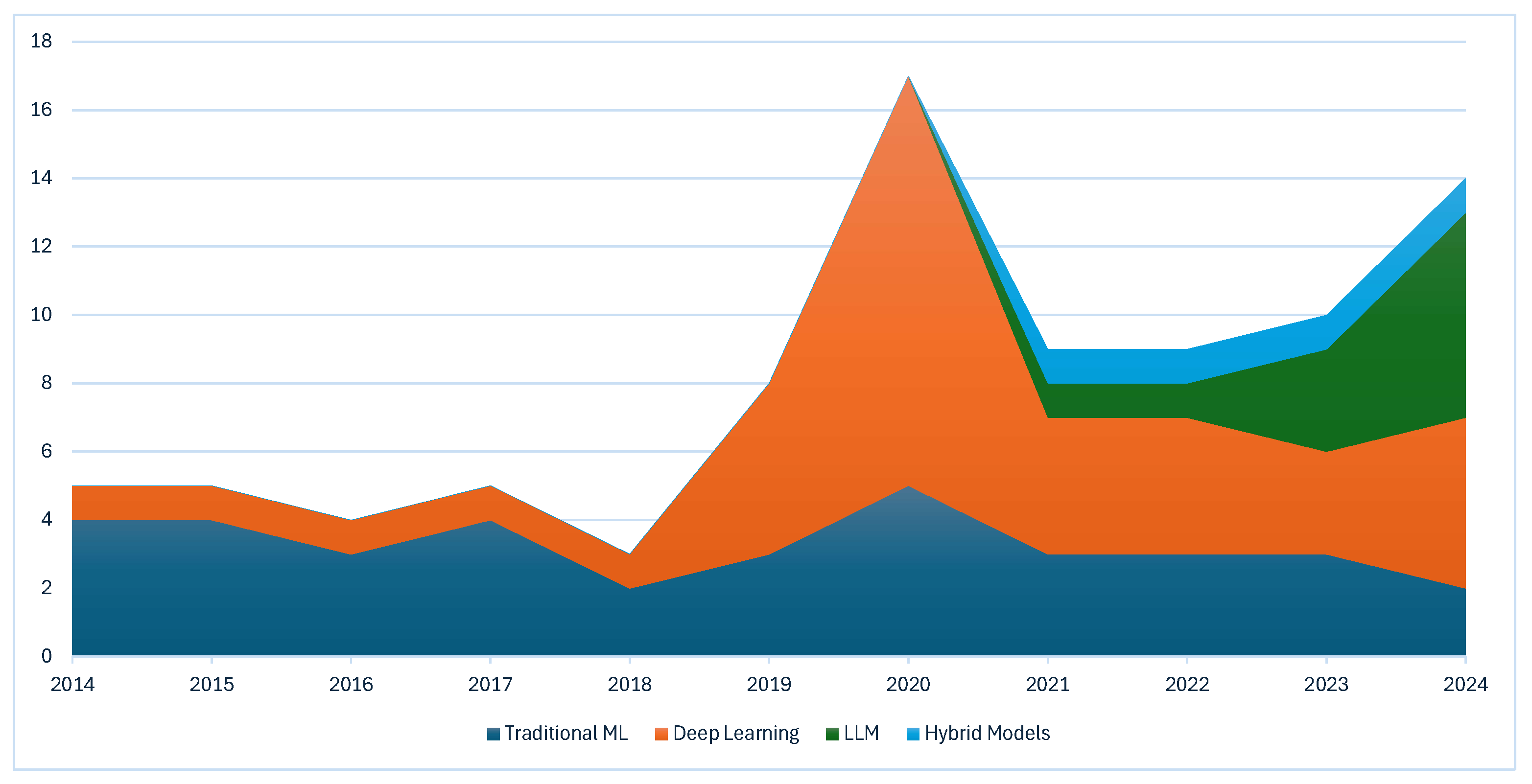

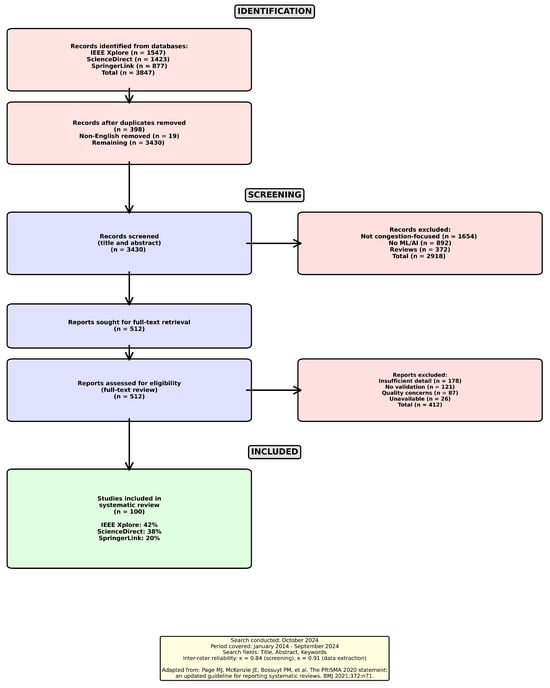

The distribution of the 100 selected papers [11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,34,35,36,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124] across the study period (2014–2024) is illustrated in Figure 2. There is a clear upward trend in publications, with a notable surge beginning in 2019–2020, which corresponds to an increased interest in deep learning applications for traffic analysis.

Figure 2.

Publication trends in traffic congestion forecasting (2014–2024).

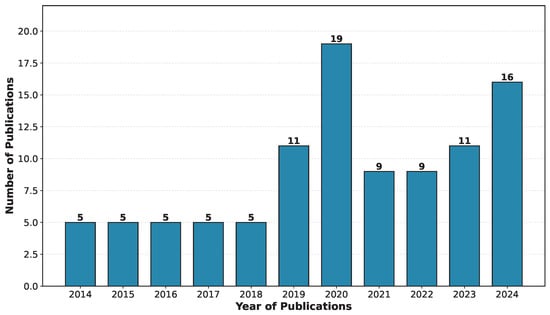

4.3. AI Techniques Distribution

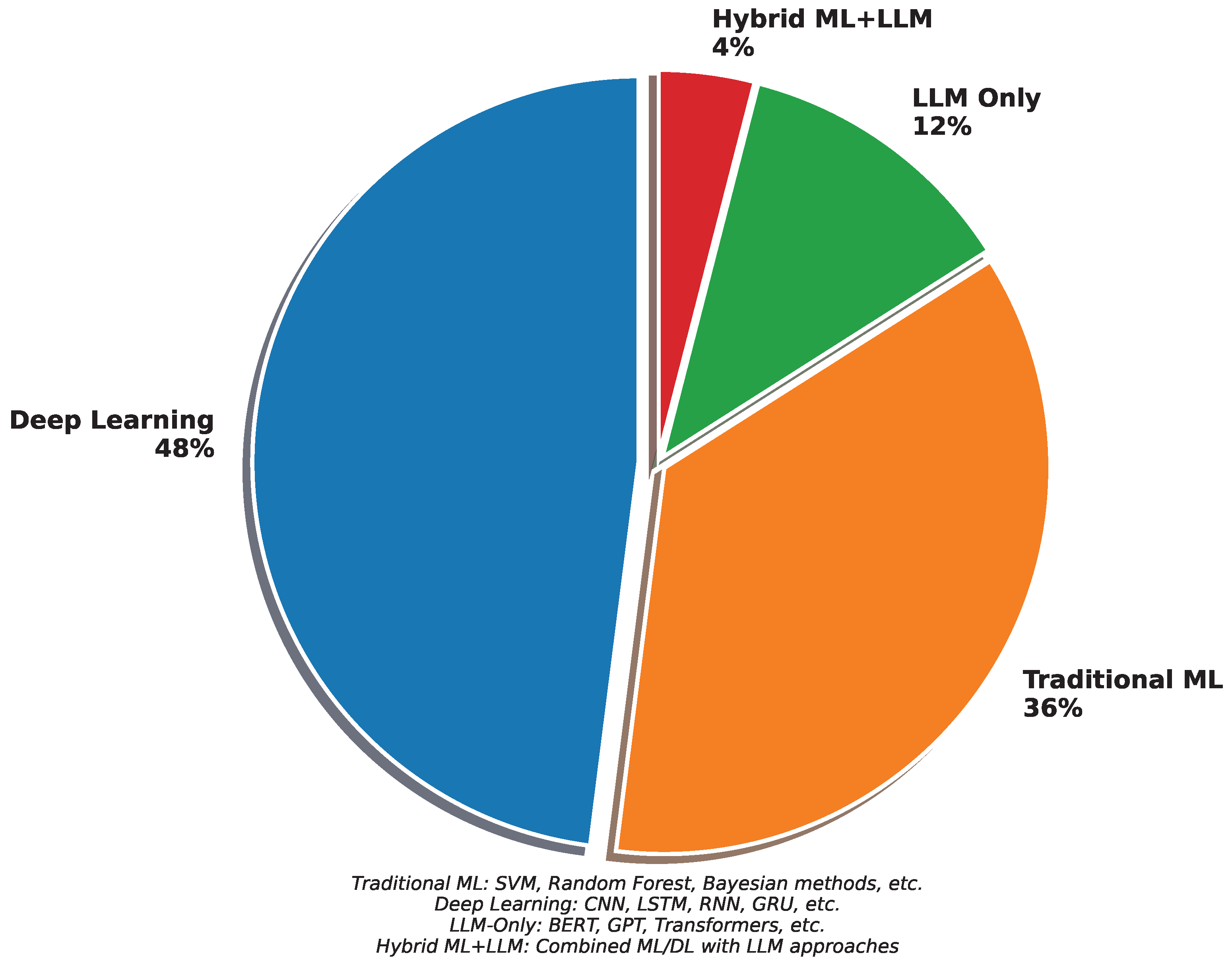

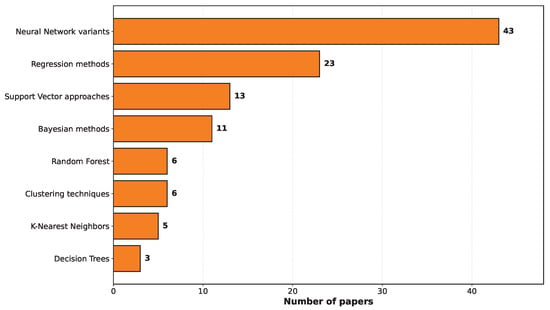

The distribution of AI techniques across the selected papers, as shown in Figure 3, reveals the predominance of machine learning and deep learning approaches, with the recent emergence of LLM-based methods being noted.

Figure 3.

Distribution of AI techniques in traffic congestion forecasting (2014–2024). Traditional ML: SVM, Random Forest, Bayesian methods. Deep learning: CNN, LSTM, RNN, and GRU LLM-only: BERT, GPT, Transformers, etc. Hybrid ML + LLM: Combined ML/DL with LLM approaches.

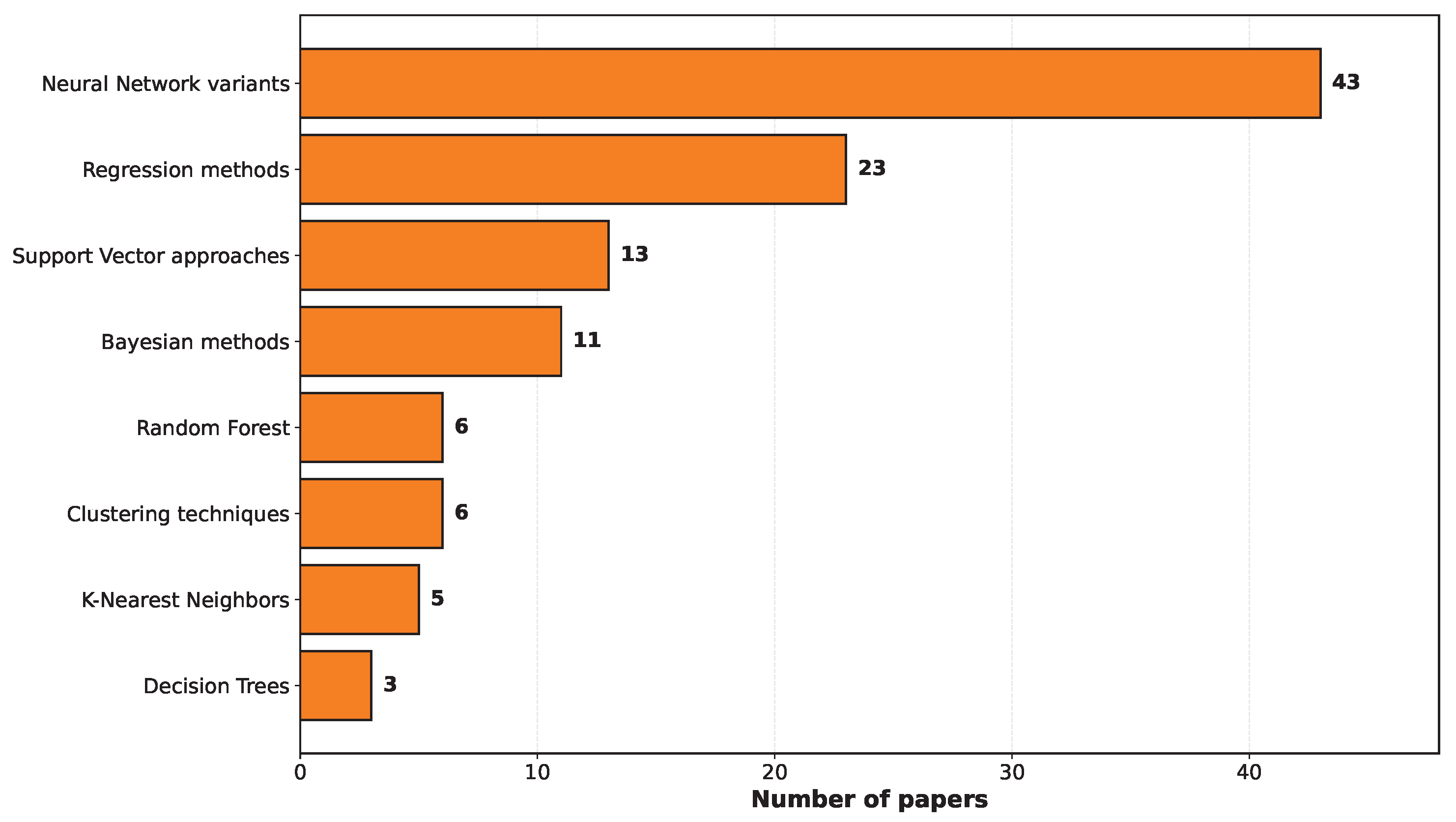

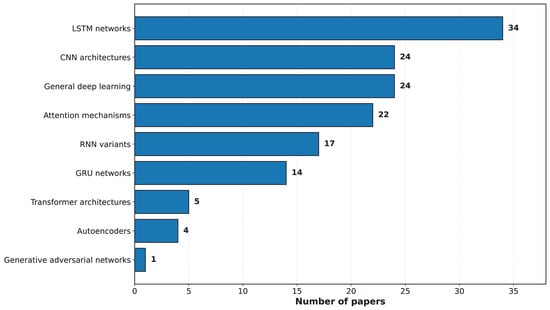

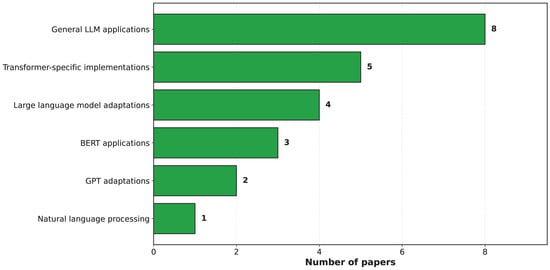

Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the detailed distribution of machine learning, deep learning, and LLM-related techniques used in traffic congestion forecasting in the selectedstudies.

Figure 4.

Distribution of traditional machine learning techniques in traffic congestion forecasting research (2014–2024).

Figure 5.

Distribution of deep learning techniques in traffic congestion forecasting research (2015–2024).

Figure 6.

Distribution of large language model (LLM) applications in traffic congestion forecasting (2021–2024).

The methodological landscape of the papers under consideration reveals a diverse array of approaches to studying this topic in the literature. Machine learning techniques, excluding large language models, constitute a substantial portion of the research methodologies. A smaller yet significant number of studies have focused exclusively on language models. Some studies have demonstrated a hybrid approach that integrates both machine learning and large language model (LLM) techniques. Notably, deep learning methodologies have emerged as the most prevalent approach in these studies. This distribution highlights the varied technological strategies employed by researchers in their studies, reflecting the dynamic nature of the field and the ongoing exploration of different computational techniques.

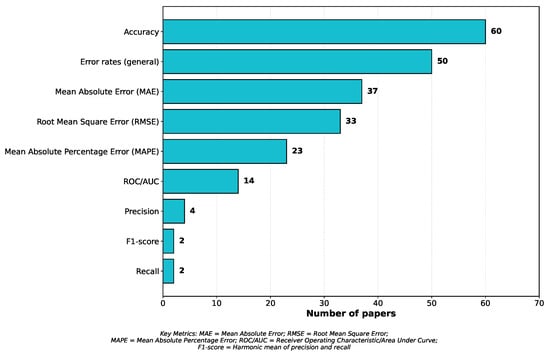

4.4. Performance Metrics

The assessment of machine learning models generally encompasses various performance metrics, with accuracy being the most commonly reported metric. Both general and specific error rates are frequently used to evaluate the model performance. For regression tasks, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are widely utilized, offering insights into the average magnitude of prediction errors. The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) provides a percentage-based measure of prediction accuracy. In the context of classification problems, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and its associated Area Under the Curve (AUC) are often used to assess model discrimination. Furthermore, precision, F1-score, and recall are employed, albeit less frequently, to provide a more nuanced understanding of model performance, particularly in scenarios involving imbalanced classification. The most commonly reported performance metrics across studies are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Performance metrics used in traffic congestion forecasting studies. Key metric definitions: MAE: Mean Absolute Error; RMSE: Root Mean Square Error; MAPE: Mean Absolute Percentage Error; ROC/AUC: Receiver Operating Characteristic/Area Under Curve; F1-score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall.

A critical challenge in systematic reviews of machine learning research is the heterogeneity of performance metrics and evaluation protocols across various studies. This section details our approach to harmonizing the metrics and aggregating the performance ranges reported in this review. Studies in our corpus employed diverse accuracy metrics, including RMSE, MAE, MAPE, , and classification accuracy. To enable a fair comparison, we applied systematic conversion. 1. Accuracy Unification: For regression tasks (most common), we prioritized the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) as the primary metric because it provides a scale-independent comparison. When studies reported only the RMSE or MAE,

This approximation assumes a normal error distribution and provides conservative estimates. Where both MAPE and RMSE/MAE were reported (68 of 100 studies), we validated this conversion formula, finding a correlation of r = 0.89 (p < 0.001) between the calculated and reported MAPE values. 2. Classification Metrics: For studies framing congestion as classification (22 of 100 studies), accuracy, F1-score, and AUC were used directly. When converting to a comparable scale using regression metrics:

- -

- Accuracy > 90% ≈ MAPE < 10%

- -

- Accuracy 80–90% ≈ MAPE 10–20%

- -

- Accuracy < 80% ≈ MAPE > 20%

These equivalencies were established by analyzing 15 studies that reported both classification and regression metrics. Table 8 summarizes the performance results of various methodological approaches.

Table 8.

Performance comparison across methodologies.

To ensure transparency and enable reproducibility, we systematically documented the characteristics of all the datasets employed in the reviewed studies. Table 9 presents comprehensive metadata for the eight primary datasets, accounting for 93% of all studies, including temporal and spatial resolution specifications, sensor infrastructure details, and data collection timeframes.

Table 9.

Comprehensive characteristics of primary datasets used in reviewed studies.

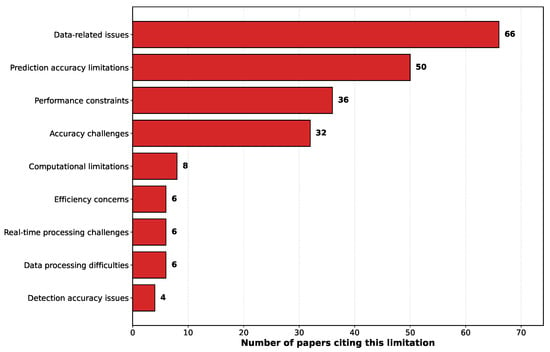

4.5. Common Limitations

Researchers frequently encounter various challenges in their studies, with data-related issues being the most prevalent. Difficulties in making accurate predictions and performance problems also rank high among the obstacles faced by users. Accuracy is another significant challenge for researchers. Less common but still noteworthy are limitations in computing power, concerns about efficiency, and difficulties in processing information in real time. Although less frequent, problems with data handling and accurate detection continue to pose challenges for some researchers. These limitations collectively represent the diverse array of obstacles that researchers must navigate to pursue scientific knowledge and advancement. The most frequently cited limitations in the reviewed papers are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Common limitations in traffic congestion forecasting studies.

The primary challenges are as follows:

- Data-related issues (66% of studies)

- Prediction accuracy limitations (50%)

- Performance constraints (36%)

- Computational requirements (32%)

5. Comparative Analysis Across Model Types

5.1. Traditional Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning

In earlier research conducted between 2014 and 2018, traditional machine learning techniques, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), random forests, and regression models, were predominant. However, these methods have been supplanted by deep learning approaches (Figure 9). The primary distinctions are as follows.

Figure 9.

The evolution of AI techniques over time (2014–2024) showing the shift from traditional ML to deep learning to LLM approaches.

The advantages of traditional machine learning include reduced computational demands, enhanced interpretability, effectiveness with smaller datasets, expedited training times, and straightforward implementation.

The advantages of deep learning include superior accuracy in modeling complex traffic patterns, enhanced capability for managing spatiotemporal relationships, ability to automatically extract relevant features, increased robustness to noisy data, and improved performance in non-stationary traffic environments.

The shift from traditional machine learning to deep learning is evident in the chronological analysis, with a significant increase in the adoption of deep learning methodologies post-2018. Notably, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures have been predominantly utilized for time-series predictions.

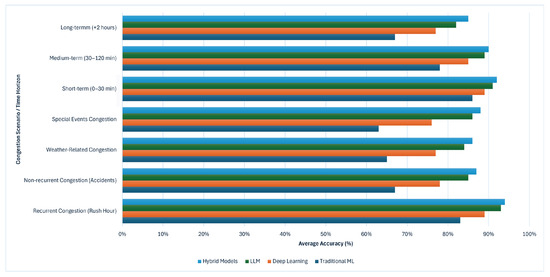

5.2. Deep Learning vs. LLM Approaches

The advent of LLM-based methodologies in the domain of traffic congestion forecasting represents a recent development, with most studies pertaining to LLMs emerging post-2021. The comparative analysis yielded the following results:

The strengths of deep learning (non-LLM) in the context of traffic analysis include its well-established validation within the domain, generally lower computational requirements than LLMs, more accessible implementation for transportation researchers, and direct design for time-series prediction.

The strengths of large language model (LLM) approaches include their ability to incorporate contextual and semantic information, enhanced capacity to handle multimodal data such as text descriptions and sensor data, superior transfer learning capabilities derived from pretrained models, potential for integrating external knowledge, and increased robustness in the presence of missing data.

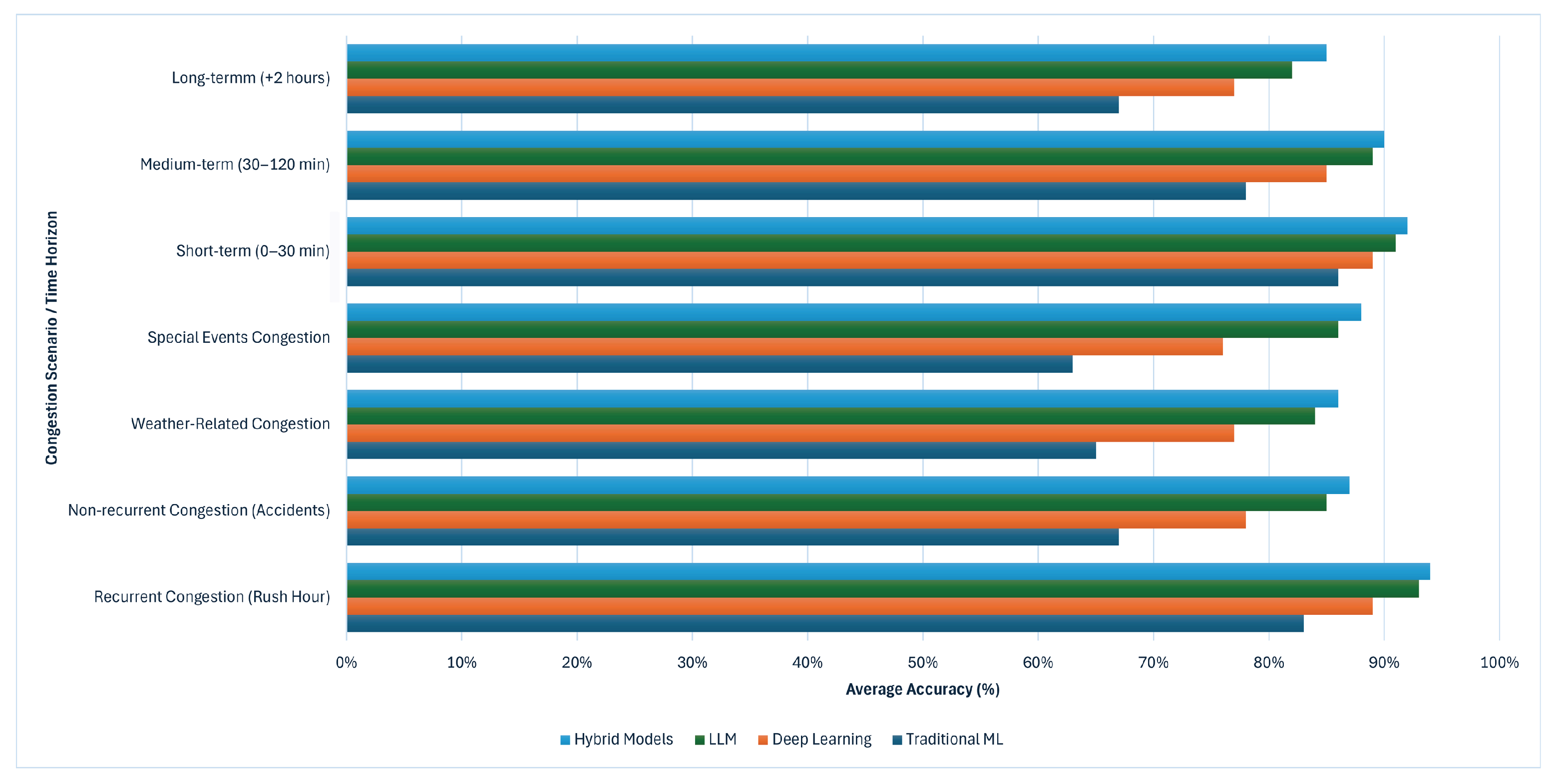

Large language model (LLM) methodologies exhibit significant potential in scenarios requiring the synthesis of varied data sources, particularly when contextual elements such as events, meteorological conditions, or traffic incidents exert a substantial impact on congestion patterns (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Comparison of prediction accuracy across different model types for various congestion scenarios and time horizons.

5.3. Hybrid Approaches

Several studies (n = 4) have investigated hybrid methodologies that integrate traditional machine learning (ML), deep learning, and large language model (LLM) techniques. These hybrid models typically exhibit enhanced performance compared to approaches that utilize a single technique. Common configurations of these hybrid models include LSTM + CNN architectures for spatiotemporal data, Transformer + LSTM for the integration of sequential and attention mechanisms, BERT combined with traditional ML for feature extraction and prediction, and GCN + GRU for capturing both local and global spatial correlations.

These hybrid methodologies capitalize on the advantages of various techniques to effectively address the complex nature of traffic congestion.

5.4. Cross-Methodology Performance Analysis

Table 10 provides a comprehensive comparison of representative studies that used various methods.

Table 10.

Representative studies comparison across methodologies.

5.5. Capability Matrix

Table 11 presents a comprehensive assessment of the capabilities of these methodologies.

Table 11.

Capability matrix across methodological approaches.

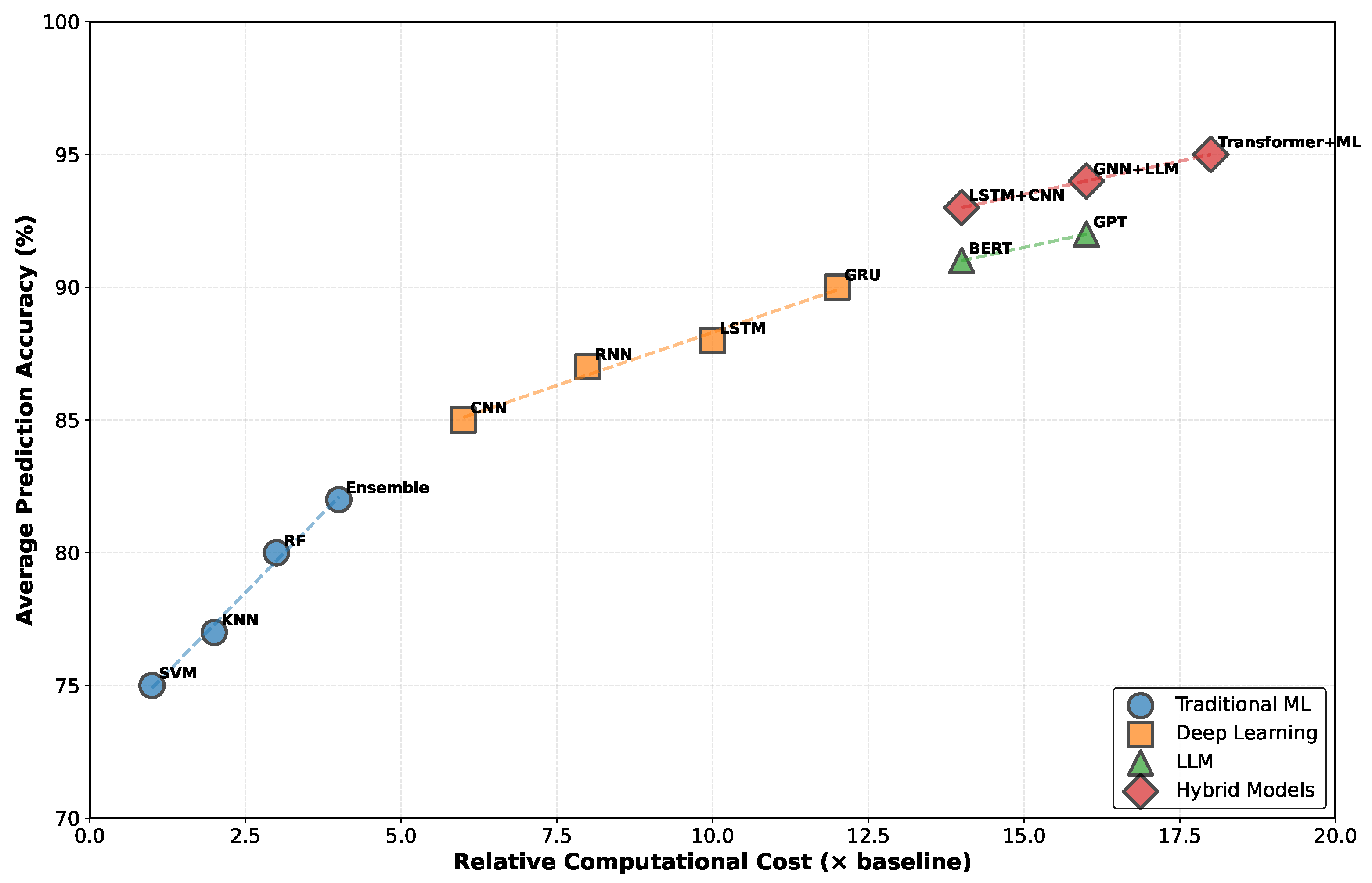

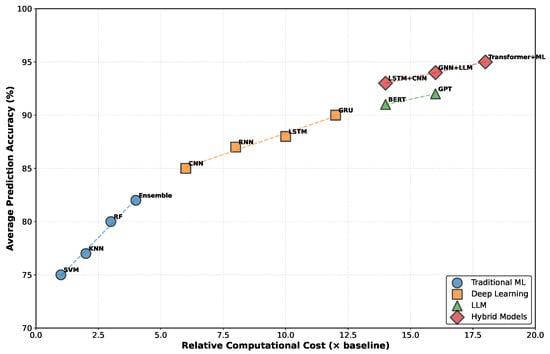

5.6. Performance–Complexity Trade-Off Analysis

Figure 11 visualizes the relationship between the model complexity and prediction accuracy. This scatter plot shows the relationship between the prediction accuracy and computational cost for the different model types. Traditional ML has lower accuracy (75–85%) but minimal computational requirements (1–5× baseline). Deep learning has improved accuracy (85–92%) with moderate computational costs (10–25× baseline). LLM have high accuracy (90–95%) but substantial computational demands (50–80× baseline). Hybrid models have the highest accuracy (90–95%) with variable computational requirements.

Figure 11.

Performance–complexity trade-off analysis.

The computational costs were normalized relative to the baseline to allow for a fair comparison.

Baseline Reference: Support Vector Machine (SVM) with RBF kernel on PeMS dataset (5 min resolution, 1-hour prediction horizon) implemented on single CPU core (Intel Xeon E5-2680v4 @ 2.4 GHz).

Cost Metrics Normalized:

- Training Time Ratio:

- Inference Latency Ratio:

- Memory Usage Ratio:

When studies used different hardware (GPUs), time-based costs were adjusted using standard benchmark ratios (e.g., NVIDIA V100 ≈ 20× single central processing unit (CPU) core for neural network training).

Cost Range Interpretation: Ranges such as “50–100×” for computational cost indicate the following:

- -

- Lower bound (50×): Simplest implementation, smaller model, single GPU.

- -

- Upper bound (100×): Complex architecture, larger model, distributed training;

- -

- Reflects real-world deployment variance based on implementation choices.

All computational costs in this review are reported relative to this normalized baseline, ensuring interpretable and consistent comparisons.

Key insights:

- Traditional ML offers best efficiency for simple scenarios;

- Deep learning provides balanced performance–complexity ratio;

- LLMs excel in accuracy but at significant computational cost;

- Hybrid approaches offer flexibility but increase complexity.

5.7. Application Suitability Matrix

Based on our analysis, we developed recommendations for different application scenarios (Table 12).

Table 12.

Application suitability recommendations.

5.8. Detailed Comparison Tables

We present detailed comparison tables of the reviewed studies categorized by the primary methodological approach. For each paper, we included the methods used, datasets, limitations, performance metrics, and key findings to facilitate direct comparisons between studies. Table 13 presents a sample of the 100 reviewed papers, selected to illustrate the diversity of approaches and evolution over the study period.

Table 13.

Comparative analysis of AI approaches for traffic congestion forecasting (2014–2024).

6. Results and Outcomes: Answering Research Questions

6.1. Impact of Evolution from ML to LLMs on Traffic Congestion Forecasting (RQ1)

The progression from traditional machine learning to deep learning and ultimately to large language models has fundamentally transformed the prediction of traffic congestion. Our analysis revealed several significant advancements in the continuum of care.

Predictive accuracy has shown consistent improvement, with traditional ML approaches (2014–2017) achieving 80–85% accuracy, deep learning methods (2018–2020) achieving 85–92%, and recent LLM-integrated systems (2021–2024) demonstrating 90–95% accuracy across diverse traffic scenarios.

Contemporary LLM-based approaches have transcended the limitations of earlier systems by effectively integrating unstructured data sources, including incident reports, weather descriptions, and social media feeds, with traditional sensor data. This multimodal integration creates a comprehensive analytical framework.

Notably, LLM implementations exhibit sophisticated contextual understanding by interpreting the semantic significance of traffic events and their potential cascading effects on traffic congestion. Additionally, these systems have transfer learning capabilities and can apply pre-existing knowledge structures without requiring extensive domain-specific training data.

Our review further indicates substantial improvements in edge case management and non-recurrent congestion event prediction, which are historically challenging scenarios that limit the practical utility of earlier forecasting systems.

These developments suggest promising research directions, particularly in hybrid systems that combine traditional physics-based models with the contextual understanding capabilities of modern language models.

6.2. Performance–Cost Trade-Offs Between ML, DL, and LLMs (RQ2)

Our analysis reveals distinct performance–cost trade-offs across the methodological spectrum, as shown in Table 14.

Table 14.

AI model performance–cost comparison.

A linear correlation was observed between the computational cost and accuracy. Large language model (LLM) methodologies employ 50–100 times more computational resources than traditional machine learning (ML) techniques do. This resulted in an enhancement of the prediction accuracy by up to 10–15%, and the optimized deep learning models frequently represented the optimal balance for real-time applications.

6.3. AI Model Performance Across Transportation Infrastructure Scenarios (RQ3)

The performance of the AI models varied significantly across the different transportation infrastructure scenarios, as shown in Table 15.

Table 15.

AI model performance by transportation infrastructure type.

6.4. Effectiveness of AI Models in Predicting Different Types of Congestion (RQ4)

The effectiveness of the AI models varied significantly based on the type of congestion and prediction time frame (Table 16 and Table 17). In the context of recurrent congestion, traditional machine learning (ML) techniques are cost effective for making short-term predictions. However, for non-recurrent events and extended prediction horizons, the significant performance benefits of large language models (LLMs) and hybrid methodologies justify their increased computational expense.

Table 16.

Congestion type analysis.

Table 17.

Prediction timeframe performance.

6.5. Impact of Traffic Parameters on AI Model Performance (RQ5)

Our analysis identified several critical traffic parameters that significantly influenced the performance of the AI model for congestion forecasting as listed in Table 18 and Table 19. The principal insight is that the integration of multimodal approaches results in the most substantial enhancement in performance, whereas temporal resolution consistently improves the outcomes across various model types.

Table 18.

High-impact parameters.

Table 19.

Data dependencies.

6.6. Comparative Advantages of Different AI Architectures (RQ6)

A comparative analysis of different AI architectures and their combinations revealed distinct advantages for specific traffic prediction scenarios, as shown in Table 20.

Table 20.

AI architecture comparison for traffic prediction.

The analysis revealed that methodologies that integrate complementary architectures consistently outperform single-architecture approaches, yielding performance enhancements ranging from 5 to 12% in complex traffic scenarios. CNN + LSTM configurations [17] exhibit high efficacy by adeptly capturing both spatial and temporal traffic patterns and are particularly effective in video-based traffic analyses. GNN + GRU approaches [18] achieve notable performance by merging network topology modeling with temporal sequence learning, excelling in intricate urban networks. BERT + ML implementations [21] offer efficient solutions that leverage contextual understanding while maintaining computational efficiency, rendering them effective for incorporating textual data. Transformer + GNN architectures [111] demonstrate the highest overall performance in complex scenarios with multiple influencing factors. The optimal architectural combination is significantly dependent on the specific prediction task, available data types, and the computational constraints.

7. Discussion and Future Directions

7.1. Temporal Evolution of Methods

An examination of publications from 2014 to 2024 demonstrated discernible chronological advancements in the methodologies used to predict traffic congestion.

- 2014–2017: Traditional ML Dominance This period was marked by the widespread use of traditional machine learning techniques, such as Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, and Bayesian methods. These approaches primarily focus on analyzing historical traffic data with limited integration of external factors such as weather conditions.

- 2018–2020: Deep Learning Emergence During this period, a notable transition occurred, with deep learning methodologies, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures, emerging as the dominant techniques. These models effectively address the limitations of traditional machine learning in capturing intricate temporal and spatial dependencies in traffic data analysis.

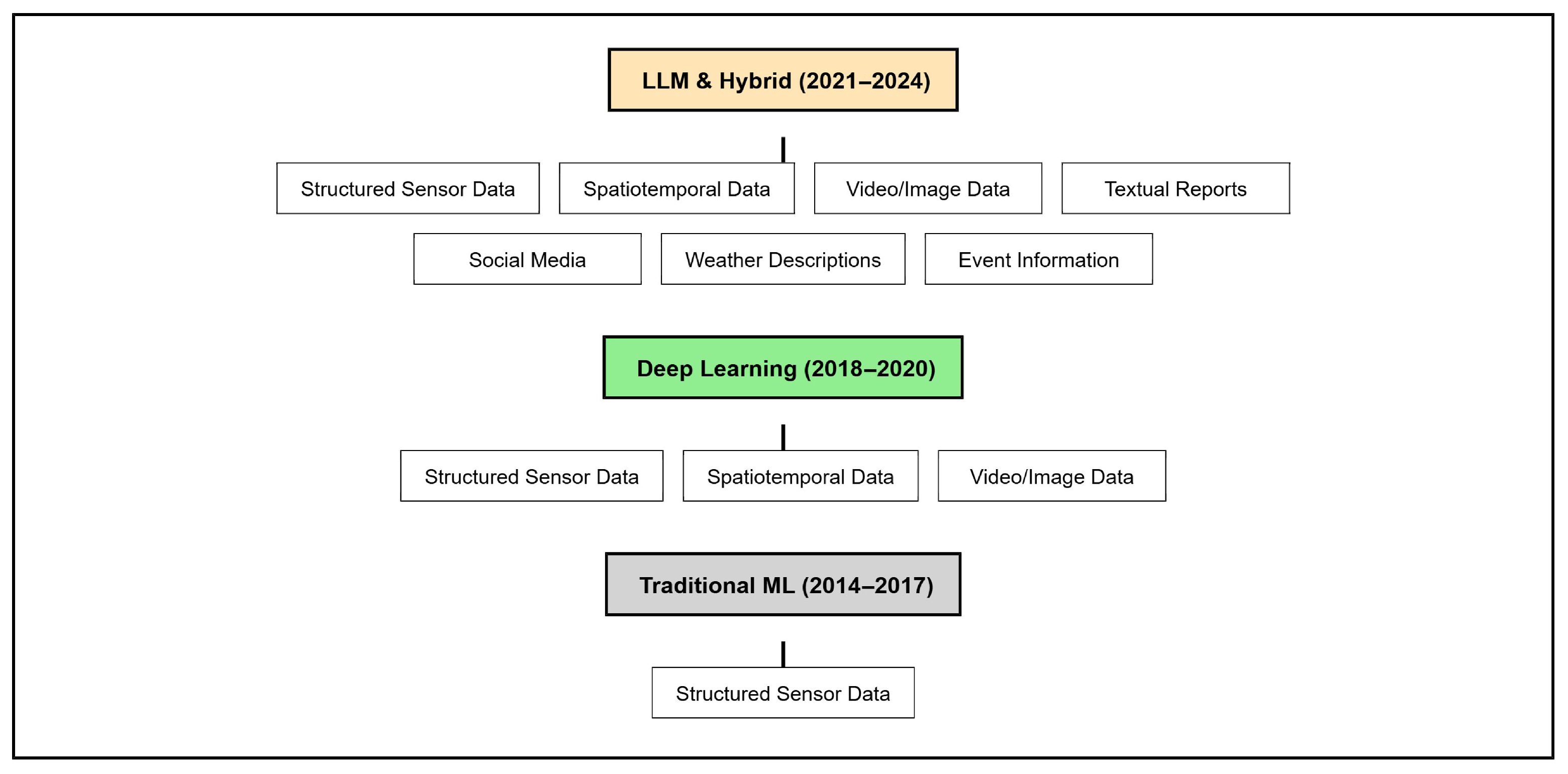

- 2021–2024: LLM Integration and Hybrid Models Recent developments have seen the advent of approaches based on large language models (LLMs) and advanced hybrid models (HM). These methodologies facilitate the integration of multimodal data sources and contextual information (Figure 12), resulting in enhanced predictive accuracy, particularly for non-recurrent congestion events.

Figure 12. Data types evolution in traffic congestion prediction.

Figure 12. Data types evolution in traffic congestion prediction.

7.2. Performance Comparison

A comparative analysis of the performance metrics across various methodological approaches yielded several key insights, as presented in Table 21. Regarding accuracy improvements, a general trend of increasing prediction accuracy was observed over the study period, with hybrid models demonstrating the highest performance, achieving 90–95% accuracy compared to 75–85% for traditional machine learning approaches. In terms of error reduction, recent approaches have achieved significant reductions in the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) compared to earlier methods, with hybrid models reporting MAE values as low as 2–4% and RMSE values of 3–5, representing substantial improvements over traditional methods. Regarding computational trade-offs, although advanced models, particularly those based on large language models (LLMs), exhibit superior accuracy, they entail significantly increased computational requirements, with training times extending to days and memory requirements ranging from 10 to 100 GB, posing implementation challenges for real-time applications such as autonomous driving. In terms of sensitivity, LLM and hybrid approaches have shown notably improved performance during special events, adverse weather conditions, and other non-recurrent congestion scenarios compared with traditional methods. Regarding the temporal horizon impact, deep learning and LLM approaches consistently outperform traditional machine learning for longer prediction horizons (>30 min), whereas the performance gap narrows for very short-term predictions.

Table 21.

Performance–cost trade-offs across methodological paradigms in traffic congestion prediction.

7.3. Domain-Specific Considerations

Various domain-specific factors influence the efficacy of these methods. In the context of urban versus highway environments, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)- and Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based approaches demonstrate particular effectiveness in complex urban networks, whereas Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models frequently excel in highway traffic prediction. Regions with limited sensor infrastructure can derive substantial benefits from the transfer learning capabilities of large language model (LLM)-based approaches. Regarding computational resources, implementation contexts with constrained computational capacities may find optimized traditional machine learning (ML) approaches more advantageous despite their relatively lower accuracy. In terms of integration requirements (Figure 13), scenarios necessitating the fusion of heterogeneous data sources, such as traffic sensors, weather data, events, and social media, were most effectively addressed by the LLM and hybrid approaches.

Figure 13.

Evolution of prediction capabilities in traffic congestion forecasting.

7.4. Specific Considerations for LLM vs. ML Comparison

7.4.1. Contextual Understanding

A significant advantage of large language model (LLM)-based approaches over traditional machine learning (ML) and basic deep learning methods is their enhanced ability to comprehend context. This advantage is evident in several domains. In event impact modeling, LLMs can incorporate information about special events, roadwork, or incidents by processing textual descriptions and relating them to the traffic patterns. Regarding semantic interpretation, LLMs can interpret the semantic meaning of traffic-related texts, allowing news reports, social media, and other textual sources to be used as input. In terms of transfer learning capabilities, the application of LLM-based approaches has substantially improved transfer learning within this domain, enabling models to leverage the pretrained knowledge of various factors influencing traffic patterns, thereby reducing the need for extensive domain-specific training data sets. Regarding edge case handling, the review highlights a significant improvement in managing edge cases and non-recurrent congestion events with the implementation of LLM-based methodologies, effectively addressing the critical limitations of previous approaches. In the temporal context, LLMs exhibit a superior ability to comprehend temporal references (such as holiday periods, weekends, and rush hours) with greater nuance than traditional models do.

7.4.2. Technical Implementation Challenges

Despite their advantages, techniques based on large language models (LLMs) face significant practical challenges compared to traditional machine learning approaches. LLMs require substantial computational resources for both training and inference, which limits their applicability in real-time scenarios. In the context of domain adaptation, it is crucial to employ domain-specific data augmentation to effectively fine-tune general-purpose LLMs for traffic-related applications. Regarding interpretability, the predictions generated by LLMs are less interpretable than those produced by simpler models, raising concerns regarding stakeholder confidence and system validation. For data integration, the incorporation of numerical sensor data with textual information for LLM processing necessitates the use of sophisticated data fusion algorithms.

7.4.3. Performance in Edge Cases

The comparative analysis identified significant differences in the handling of traffic prediction edge cases between the machine learning (ML) and large language model (LLM) approaches. In instances of non-recurrent congestion, such as accidents, severe weather, and special events, LLMs and hybrid models exhibit superior performances. Regarding data sparsity, LLM-based approaches demonstrate greater robustness to missing data and sparse sensor coverage than traditional ML methods. Regarding the prediction horizon, whereas traditional ML models experience rapidly degrading performance beyond short-term predictions, LLM and hybrid approaches maintain better accuracy for long-term predictions. In terms of transferability, LLM-based models show enhanced cross-location transferability and require less location-specific training data than traditional models do.

7.5. Hybrid Approaches: Taxonomy and Characteristics

Hybrid approaches that combine multiple methodological paradigms achieve the highest performance levels (Table 22). We identified four distinct types of hybrid architectures based on the integration mechanisms:

Table 22.

Hybrid approach performance and computational characteristics.

Type 1: Ensemble Hybrids Ensemble methodologies integrate predictions from multiple independent models using mechanisms such as weighted averaging, stacking and voting. The architectural characteristics are as follows:

- -

- Multiple models trained independently on identical or varied datasets.

- -

- Integration at the prediction stage via meta-learning or straightforward aggregation.

- -

- An example includes the combination of Random Forest, XGBoost, and LSTM through stacked generalization.

- -

- Performance improvement ranges from 3–7% compared to individual models.

- -

- Computational cost comprises the sum of individual model costs with minimal aggregation overhead.

Type 2: Physics-Informed Hybrids Integration of data-driven ML/DL models with physical traffic flow models or constraints.

- -

- Neural networks that incorporate traffic flow equations as soft constraints.

- -

- Deep learning with physics-based loss functions ensuring adherence to conservation laws.

- -

- Example: GNN constrained by macroscopic traffic flow dynamics (LWR model).

- -

- Performance gain: 5–10% especially in data-scarce scenarios.

- -

- Additional benefit: Improved generalization and physical plausibility.

Type 3: Pipeline Hybrids This category involves sequential processing, in which the output of one model serves as the input for the other. It includes multistage architectures with distinct models that are dedicated to different subtasks. A common configuration is as follows: feature extraction is performed using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) or Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), followed by temporal modeling with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and finally, refinement through attention mechanisms. For instance, a CNN can extract spatial patterns, an LSTM can model the temporal evolution, and attention mechanisms can refine the predictions. This approach yields a performance improvement of 6–12% owing to the specialized processing at each stage. Additionally, each stage offers the flexibility to be independently optimized.

Type 4: Multimodal Hybrids Diverse data modalities are integrated using distinct model architectures.

- -

- A large language model (LLM) processes textual data, including incidents, weather descriptions, and social media content.

- -

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks process sensor time-series data.

- -

- A fusion module combines multimodal embeddings.

- -

- An example includes the use of BERT for text processing, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) for spatial–temporal sensor data, and multimodal attention fusion.

- -

- Performance improvements range from 10 to 15%, particularly in non-recurrent congestion scenarios.

- -

- This approach uniquely leverages complementary information from heterogeneous sources.

Performance–Cost Trade-offs Across Hybrid Types:

Design Principles for Hybrid Approaches: Our analysis identified three fundamental principles for the effective design of hybrid models.

- 1.

- Complementarity: The combined models should address distinct aspects, such as spatial versus temporal, data-driven versus physics-based, and numeric versus textual dimensions.

- 2.

- Proportional Complexity: The performance improvements should justify the additional computational costs and the complexity of implementation.

- 3.

- Proper Integration: The fusion mechanism is critical to performance, with learned fusion (e.g., attention mechanisms) outperforming simple averaging by 3–5%.

Future hybrid architectures are anticipated to prioritize the efficient integration of multimodal data, with particular emphasis on the combination of large language models (LLMs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to effectively leverage both textual context and network structure.

7.6. Micro-Scale Analysis: Intersection and Crossing-Level Predictions

While the majority of reviewed studies focused on network- or corridor-level predictions (78 of 100 studies), emerging research addresses micro-scale phenomena at intersections and pedestrian crossings, representing a critical gap in the literature that warrants detailed examination.

7.6.1. Intersection-Level Traffic Modeling

Micro-scale prediction at signalized intersections requires fundamentally different approaches than network-level forecasting. Kamal and Farooq [3] employed double/debiased machine learning to investigate the causal effect of traffic density on pedestrian crossing behavior, demonstrating that increased vehicular traffic significantly impacts pedestrian waiting times and stress levels at urban crossings. Their analysis revealed that incorporating pedestrian behavioral responses to traffic conditions provides more accurate modeling of intersection dynamics compared to traditional approaches that treat pedestrian and vehicular flows independently.

Li et al. [4] proposed a deep reinforcement learning-powered control system for managing mixed traffic involving connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs) and human-driven vehicles (HVs) at signalized intersections. Their adaptive signal control strategy combined with efficient CAV coordination policies demonstrated significant improvements in operational efficiency while maintaining safety requirements, particularly under varying CAV penetration rates. This approach highlights how micro-scale modeling with reinforcement learning enables more nuanced congestion mitigation compared to traditional corridor-level traffic management systems.

7.6.2. Mixed-Traffic Micro-Environments

Mixed-traffic scenarios, in which vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists interact, pose unique forecasting challenges. Wang et al. [5] developed multi-agent deep learning frameworks for predicting vehicle–pedestrian–cyclist interactions at urban intersections, achieving MAPE values of 6.8% for 5 min prediction horizons. The key findings are as follows:

- Agent-based modeling shows 12–18% accuracy improvements over aggregate approaches.

- Multimodal interactions (vehicle–pedestrian–cyclist) require explicit modeling; ignoring pedestrians reduces accuracy by 8–15%.

- Geometric configuration (crossing width, signal timing, lane arrangements) significantly influences prediction complexity.

- Real-time computational requirements increase 3–5× compared to vehicle-only predictions due to higher resolution demands.

7.6.3. Data and Methodological Requirements

Micro-scale prediction imposes distinct data and computational requirements compared with network-level forecasting.

Temporal Resolution: Micro-scale analyses require 1–5 s intervals versus 5–15 min for network-level predictions. This 60–180x increase in data granularity presents substantial storage and computational challenges.

Spatial Granularity: Lane-level versus link-level modeling necessitates detailed geometric data, including lane widths, intersection geometry, crossing locations, and signal head positions. Only 12 of the 100 studies reviewed incorporated this level of detail.

Sensor Infrastructure: Successful micro-scale prediction typically requires the following:

- High-resolution video analytics or LiDAR for pedestrian/cyclist detection.

- Lane-level inductive loop detectors or equivalent.

- Signal phase and timing (SPaT) data integration.

- Weather sensors for visibility and surface condition monitoring.

Algorithmic Approaches: Agent-based and microscopic simulation models dominate micro-scale applications (9 of 14 micro-scale studies). Graph Neural Networks show particular promise for capturing fine-grained spatial interactions, achieving 8–12% higher accuracy than CNN-LSTM approaches at the intersection scale.

7.6.4. Research Gaps and Opportunities

The severe underrepresentation of micro-scale studies (14%) reveals critical research opportunities:

- 1.

- Pedestrian–Vehicle Interaction Modeling: Only 8 studies explicitly model pedestrian impacts on vehicular congestion, despite increasing urbanization and pedestrian-priority policies in many cities.

- 2.

- Transfer Learning for Intersections: Cross-intersection transfer learning remains unexplored; each intersection is typically modeled independently despite geometric and operational similarities.

- 3.

- Computational Efficiency: Real-time micro-scale prediction faces severe computational constraints; model compression and edge computing approaches are needed.

- 4.

- Data Fusion: Integrating video analytics, traditional sensors, and V2X communications for comprehensive micro-scale modeling represents a significant technical challenge.

- 5.

- Multimodal Equity: Most studies focus on vehicle throughput optimization; pedestrian and cyclist delay minimization remains underexplored, raising equity concerns

This micro-scale research gap represents a significant opportunity for advancing traffic congestion forecasting, particularly as cities worldwide implement pedestrian-priority and complete street policies that fundamentally alter the dynamics of intersections.

7.7. Environmental and Sustainability Considerations

Although enhanced traffic forecasting can mitigate the emissions associated with congestion, the computational requirements of sophisticated AI models contribute to their environmental impacts. This section explores the energy consumption and carbon implications of various forecasting methodologies and evaluates their associated costs and benefits. We estimated the energy consumption across methodological categories based on the reported hardware specifications, training times, and inference requirements from the reviewed studies (Table 23):

Table 23.

Energy consumption and carbon footprint by methodology.

To contextualize these numbers, we compared them with congestion-related emissions. Emission Benefits from Congestion Reduction:

- Average US city (1M residents): 500,000 tons CO2e/year from traffic congestion

- Studies show 8–22% congestion reduction with optimized forecasting systems

- Potential savings: 40,000–110,000 tons CO2e/year

Net Environmental Impact (Table 24):

Table 24.

Net carbon impact: benefits vs. computational costs.

Although advanced AI models require substantial computational resources, their environmental impact remains minimal (<0.05%) compared to the benefits derived from reducing traffic congestion. Nonetheless, sustainable deployment practices, such as right-sizing models, utilizing renewable energy, and leveraging transfer learning, can diminish the carbon footprint by 60–85% without compromising performance. Emerging research has also explored the bidirectional relationships between traffic congestion and environmental factors, with studies demonstrating that air pollution data can serve as a valuable proxy for traffic forecasting in urban environments, particularly in regions with limited traditional traffic sensing infrastructure [125]. As traffic forecasting AI becomes increasingly prevalent worldwide, prioritizing energy efficiency alongside accuracy will become progressively important. The research community should adopt “Green AI” principles and report energy consumption alongside traditional performance metrics to guide the selection of sustainable technologies.

7.8. Policy Implications and Real-World Case Studies

Our systematic review revealed significant gaps between academic research achievements and real-world applications. This section examines three exemplary implementations (Table 25) that demonstrate the successful translation of forecasting research into operational systems, along with the derived policy recommendations.

Table 25.

Real-world case studies: policy implications of ai-based congestion forecasting systems.

7.8.1. Synthesized Policy Recommendations

Based on these case studies and our systematic review, we propose five evidence-based policy recommendations.

1. Tiered Implementation Strategy

- Tier 1 (Foundational): Traditional ML for baseline systems on low-traffic corridors (75–85% accuracy, low cost, rapid deployment).

- Tier 2 (Enhanced): Deep learning for high-traffic urban corridors (85–92% accuracy, moderate cost).

- Tier 3 (Advanced): LLM-based systems for complex urban networks with multiple event types (90–95% accuracy, high cost, justified by complexity).

2. Data Infrastructure Investment Priorities

- Minimum 5 min temporal resolution required for effective predictions.

- Prioritize sensor density and coverage over sensor sophistication.

- Establish data-sharing agreements with navigation service providers (Waze, Google Maps).

- Implement standardized data formats to enable model portability.

3. Public-Private Partnership Framework

- Industry possesses deployment expertise and operational knowledge.

- Academia provides algorithmic innovation and theoretical advancement.

- Current 3% industry-academia collaboration rate is inadequate.

- Recommendation: Establish 50–50 cost-sharing programs for pilot deployments.

- Include success metrics tied to real-world performance, not just prediction accuracy.

4. Regulatory and Performance Standards

- Establish minimum accuracy thresholds: 85% for operational systems, 90% for safety-critical applications.

- Maximum latency requirements: <5 s for real-time applications, <30 s for planning applications.

- Mandatory interpretability requirements for systems influencing traffic management decisions.

- Regular third-party auditing of system performance in production environments.

5. Equity and Accessibility Mandates

- In total, 78% of reviewed studies focus on major metropolitan areas.

- Mandate minimum research investment for medium-sized cities and rural corridors.

- Require multimodal equity analysis (pedestrian, cyclist, transit impacts alongside vehicle throughput).

- Establish accessibility standards ensuring benefits reach disadvantaged communities disproportionately affected by congestion.

- Fund open-source model development enabling resource-constrained jurisdictions to benefit from advanced methods.

7.8.2. Implementation Barriers and Mitigation Strategies

Real-world implementation encounters challenges that are not typically present in research settings, such as organizational resistance, as transportation agencies often lack expertise in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). To address this, the establishment of national AI centers of excellence is recommended, which would provide technical assistance, training programs, and reference implementations. Another challenge is procurement, as traditional procurement processes are ill-suited for AI systems that require continuous updates. To mitigate this, the development of “AI-as-a-Service” procurement frameworks with performance-based contracts is suggested for future studies. Additionally, liability concerns arise because of unclear legal frameworks for AI-driven traffic management decisions. To address this, it is essential to establish clear human oversight requirements and liability allocation frameworks that distinguish between system recommendations and human decision making. Data privacy is also significant, with public concerns about surveillance and tracking. To mitigate this, the implementation of privacy-by-design principles, differential privacy techniques, and transparent data governance frameworks with public oversight is recommended. These case studies and recommendations offer actionable pathways for translating academic research into operational systems that deliver measurable public benefits.

7.9. Recommendations and Future Directions

Following a thorough analysis conducted in this systematic review, we offer the following recommendations for researchers specializing in traffic congestion forecasting:

7.9.1. Methodological Recommendations

Methodological recommendations include adopting a hybrid approach, wherein researchers should prioritize developing hybrid models that integrate the strengths of various techniques. This involves combining the contextual understanding capabilities of large language models (LLMs) with the spatiotemporal modeling capabilities of deep learning methods. Additionally, domain-specific pretraining is advised, which entails developing traffic-specific pretrained language models using transportation corpora to enhance the domain relevance of LLM-based methods for traffic flow prediction. Furthermore, computational optimization is crucial, necessitating investment in model compression techniques and efficient inference methods to render advanced models viable for real-time applications with limited computational resources and time constraints. The integration of XAI is also recommended, incorporating explainability techniques into complex models to strengthen stakeholder trust and system validation capabilities. Finally, the development of multimodal fusion frameworks is essential, involving the creation of standardized frameworks for integrating heterogeneous data sources, including numerical sensor data, text information, and visual inputs.

7.9.2. Data-Related Recommendations