Automation in the Shellfish Aquaculture Sector to Ensure Sustainability and Food Security

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Shellfish Aquaculture Species, Production, and Availability

1.2. The Need for Automation in the Shellfish Sector

2. Automation in Production Stage

2.1. Hatchery and Spat Collection Automation

2.2. Farm Monitoring and Husbandry Automation

3. Automation in the Harvest Stage

4. Automation in the Processing Stage

4.1. Automated Grading Systems

4.2. Automated Depuration and Purification

4.3. Image and Sensor-Based Technologies for Quality

4.4. Robotic and Intelligent Handling Systems

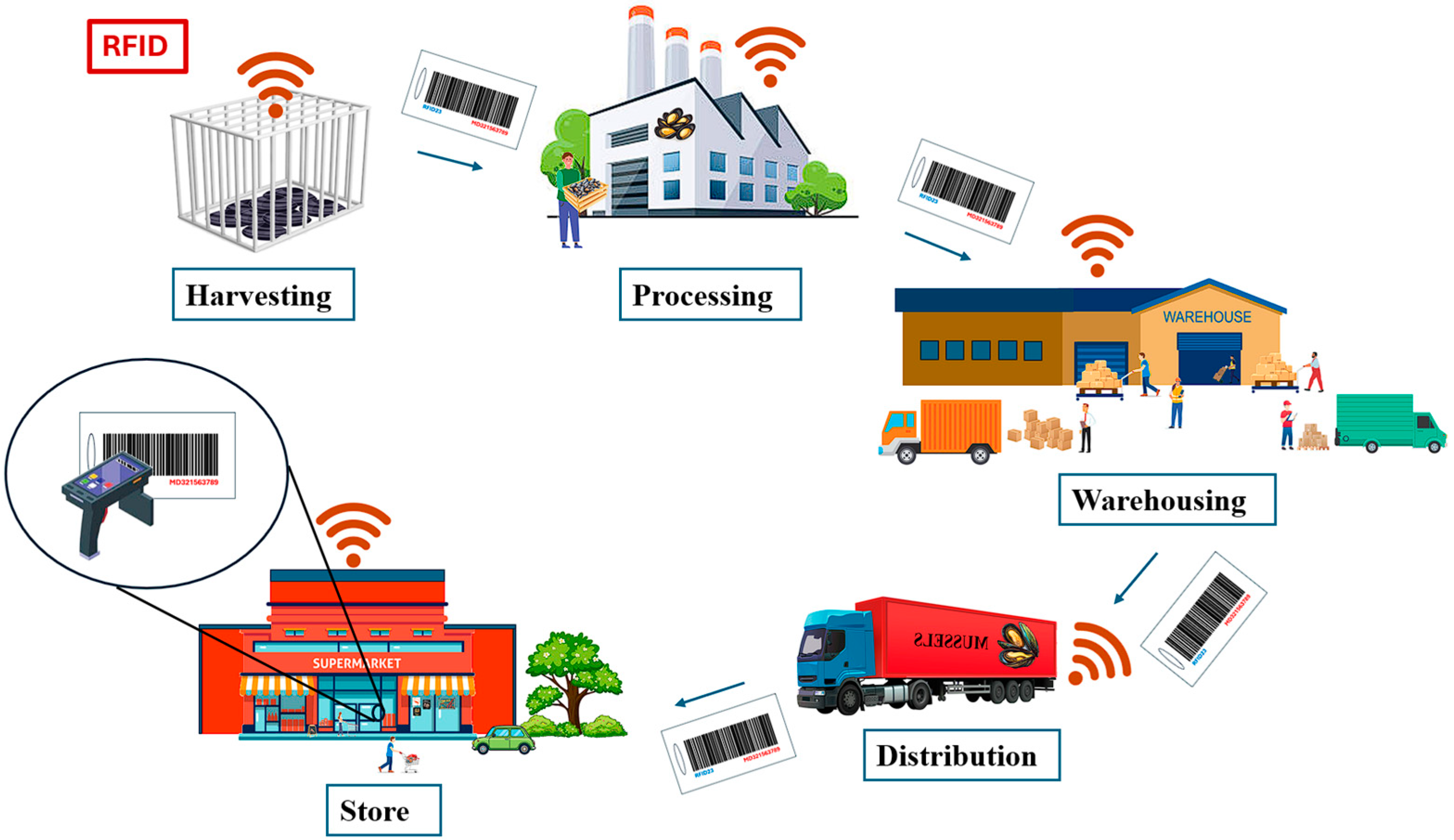

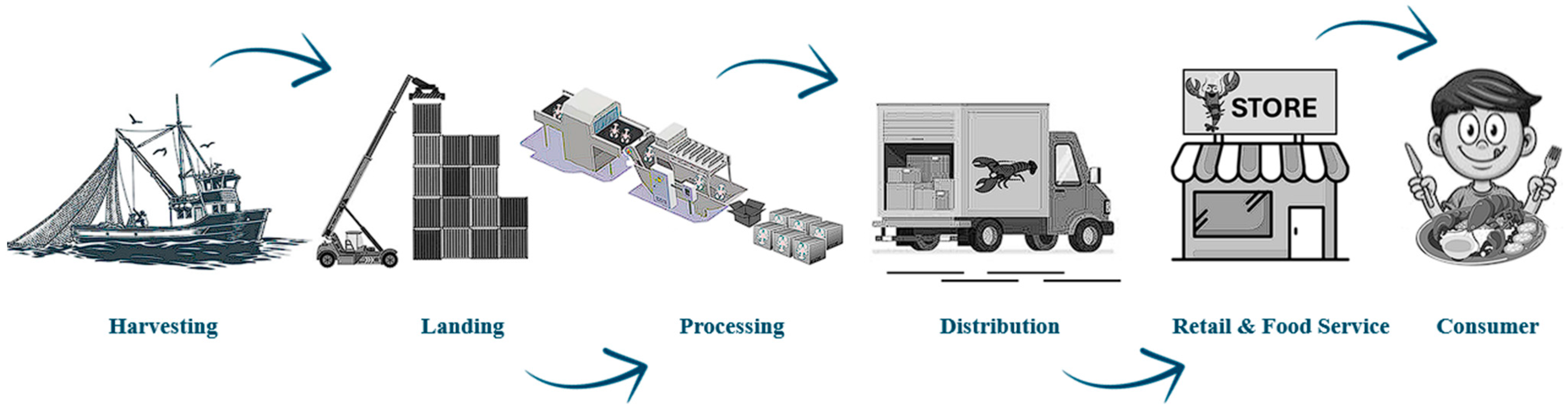

5. Automation in Traceability, Logistics, and Transportation

5.1. Shellfish Supply Chain and Traceability

| S.No. | Technology | Role | Main Applications in Shellfish | Advantages | Disadvantages | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Blockchain | Distributed ledger ensuring traceability and data integrity | 1. Verification of oyster and mussels 2. Fraud prevention in lobster and crab exports 3. Evaluation of frozen shellfish quality 4. Traceability of shrimps | 1. Aids in traceability 2. Builds trust in consumers | 1. High energy demand 2. Adoptable in small-scale | [52,57,58,59,60,61] |

| 2. | RFID tags | Radio-frequency chips for real-time tracking | Monitoring oyster crates, mussel sacks, and lobster consignments in the cold chain | 1. Accuracy 2. Automated tracking 3. Reduces manual errors | 1. Fail in saline and wet conditions 2. Higher cost | [54] |

| 3. | QR codes | Scannable labels for product information | 1. Consumer accessible data on shrimp and prawn handling 2. Oyster freshness | 1. Low cost 2. Easy to adopt 3. Linkable to blockchain | 1. Static in nature 2. Prone to tampering 3. Doesn’t monitor real-time 4. Prone to wet conditions | [61] |

| 4. | IoT | Networked sensors transmitting environmental data | 1. pH, DO (mg/L), and CO2-based sensors in prawn tanks 2. Salinity (PSU) and temperature (°C) loggers for lobsters 3. Real-time monitoring in crab farms 4. Water quality monitoring for crab larvae | Continuous real-time monitoring | 1. Internet connectivity issues in remote areas 2. Battery life | [61] |

| 5. | Cloud computing | Centralized storage and analytics for logistics | 1. Shellfish distribution dashboards 2. Real-time alerts for mussel desiccation 3. Crab overheating monitoring | 1. Scalability 2. Integrative 3. Remotely accessible | 1. Data security concerns 2. Internet dependency | [61] |

| 6. | Artificial Intelligence | Algorithms for pattern recognition and prediction | 1. Survival prediction in shrimp overcrowding 2. Loster stress recognition 3. Automated breeding system for crabs | 1. High prediction accuracy 2. Decision automation | 1. Requires large datasets 2. Training complexity | [62] |

| 7. | Big data | Large-scale collection and processing of logistics data | 1. Market demand forecasting for oysters 2. Mortality analysis in crayfish transportation | Supports optimization of supply chains | Data heterogeneity and integration challenges | [59] |

| 8. | GPS | Satellite-based geolocation | 1. Route optimization for long-distance lobsters and crab exports 2. Live location tracking of the mussel | 1. Enhances logistics transparency 2. Reduces delays | Signal dropouts in containers or ports | [62] |

| 9. | NFC | Short-range wireless for simulation | Consumer-level shellfish freshness validation at retail points | 1. Easy customer interaction 2. Secure data transfer | 1. Very short range 2. Requires NFC-enabled devices | [62] |

| 10. | Digital Twin | Virtual model of logistics system for simulation | Simulation of the oyster and mussel cold chain to predict survival under different routes | Aids in proactive risk management | 1. High implementation costs 2. Expertise required | [59] |

| 11. | Biosensors | Analytical sensors for biological signals | 1. Mortality and stress detection in shrimps 2. Ammonia buildup in dense prawn consignments | 1. Non-destructive 2. Real-time monitoring 3. High sensitivity | Calibration and Fouling issues in seawater | [63] |

| 12. | Smart Packaging | Packaging embedded with sensors or indicators | 1. Colorimetric freshness labels for oysters 2. Humidity control liners for mussels | 1. Enhances consumer trust 2. Reduces waste | 1. Additional cost 2. Disposable challenges | [64,65] |

5.2. Advanced Automation Methods in Shellfish Traceability

5.2.1. QR Code

5.2.2. RFID Technology

5.2.3. Blockchain

5.2.4. IoT

5.3. Automated Environmental Monitoring and Control in Transportation

5.4. Automation for Survival, Quality, and Welfare Monitoring

5.5. Automation in Logistics

| Stage | Automation Focus | Technologies | Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hatchery & Spat Transfer | Automated feeding, grading, and spat attachment | GPS-guided feeders, ANN-based shrimp feeders, and an automated oyster spat insertion device | Reduced labor, uniform growth, and efficient stocking | [8,15,18] |

| Farm Monitoring & Husbandry | Real-time environmental and stock monitoring | IoT sensor networks, underwater drones (BlueROV2), computer-vision “Oystamaran” | Precision aquaculture, early warning of stress events | [19,20,21,22,23,24] |

| Harvesting | Mechanized lifting, automated grading, and sorting | Hydraulic winches, automated graders, and vision-based oyster sorters | Faster harvest, improved product quality, reduced labor needs | [29,30,31,32] |

| Processing | Depuration, non-destructive quality inspection, robotic handling | Automated depuration systems, hyperspectral or CT imaging, Coboshell robot, and delta-robot pickers | Enhanced food safety, higher accuracy, and less waste | [36,37,38,45,46] |

| Traceability & Logistics | Smart supply-chain tracking and live-transport control | QR codes, RFID, blockchain, IoT-enabled cold chain | Transparency, regulatory compliance, survival & welfare monitoring | [47,48,49,79,81] |

| Application | Species | Automation | Measured Parameters | Efficiency (%) | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic oyster grading | Crassostrea gigas | Machine-vision system (YOLOv8) | Classification accuracy | 100% accuracy in size and shape grading | Eliminated manual sorting errors and improved uniformity | [38] |

| Shrimp freshness detection | Litopenaeus vannamei | E-nose and SVM classification | VOC analysis | 96.29% accuracy for freshness prediction | Real-time spoilage assessment through a non-destructive method | [48] |

| Crab sex identification | Portunus trituberculatus | Deep learning through YOLOv8 segmentation | Image classification | 100% identification accuracy | Automated sorting under variable lighting | [51] |

| Automated crab meat picking | Portunus trituberculatus | Robotic arm and vision feedback | Extraction efficiency | 97.67% picking precision | Reduced meat loss and improved yield | [51] |

| Smart feeding control | Crassostrea gigas and Mytilus edulis | IoT sensor network and AI feed optimization | Feed conversion ratio (FCR) | 20–30% feed savings | Reduced waste and improved growth efficiency | [9] |

| Water-quality monitoring (LoRaWAN) | Coastal bivalve farms | LoRaWAN and edge gateway | pH, DO, temperature | Continuous 99% uptime in data transfer | Low-power, real-time monitoring for remote sites | [11] |

| Blockchain traceability | Shellfish in the supply chain | Blockchain and QR integration | Product traceability time | Reduction from 24 h to less than 1 h | Enhanced transparency and data integrity | [13] |

| Automated bag flipping (Oystamaran) | Crassostrea gigas | Vision-guided robotic system | Labor hour | More than 70% reduction in manual flipping time | Reduced labor exposure and ensured operational safety | [24] |

| Automated seeding device | Crassostrea gigas | Spat insertion robotic system | Throughput improvement | 2.5× faster than manual threading, reduced 4.71% spat damage, and 92.08% fixation rate | Enhanced hatchery-to-farm efficiency | [21,22] |

6. Challenges in Automation and Future Trends in the Shellfish Sector

6.1. Structural Constraints in a Fragmented Industry

6.2. Human Capital and Technical Skills Gap

6.3. Research to Deployment Gap in Sensing and Analytics

6.4. Financing Barriers and Cost of Adoption

6.5. Towards Interoperable, Explainable, and Sensor Rich Systems

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HACCP | Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ISFET | Ion-Sensitive Field Effect Transistor |

| LoRaWAN | Long Range Wide Area Network |

| NFC | Near Field Communication |

| QR | Quick Response |

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identification |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TTI | Time–Temperature Indicator |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 (SOFIA). In Key Figures for 2022 Totals and the Aquaculture-Surpasses-Capture Milestone; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Azra, M.N.; Okomoda, V.T.; Tabatabaei, M.; Hassan, M.; Ikhwanuddin, M. The contributions of shellfish aquaculture to global food security: Assessing its characteristics from a future food perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 654897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fishstatj—Software for Fishery and Aquaculture Statistical Time Series; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA Fisheries. Aquaculture Supports a Sustainable Earth. 2020. Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/aquaculture-supports-sustainable-earth (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Institute for Systems Research. Using Underwater Robots to Detect and Count Oysters. 2021. Available online: https://isr.umd.edu/news/story/using-underwater-robots-to-detect-and-count-oysters (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Thornburg, J. Feed the fish: A review of aquaculture feeders and their strategic implementation. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2025, 56, E70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunde, V.V.Y.; Kamble, M.T.; Chavan, B.R.; Palekar, G.K.R.; Tayade, S.H.; Ponpornpisit, A.; Thompson, K.D.; Medhe, S.V.; Pirarat, N. Effects of climate change-induced temperature rise on crustacean aquaculture: A comprehensive review. Aquac. Fish. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, W.C.; Barros, H.P.; Moraes-Valenti, P.; Bueno, G.W.; Cavalli, R.O. Aquaculture in Brazil: Past, present and future. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 19, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Jiang, T.; Shen, J. Design and Experimental Optimization of an Automated Longline-Suspended Oyster Spat Insertion Device. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, F.R. Traditional marine resource management in Vanuatu: Acknowledging, supporting and strengthening indigenous management systems. SPC Tradit. Mar. Resour. Manag. Knowl. Inf. Bull. 2006, 20, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Precision Tools for Farming Mussels and Oysters More Sustainably. News. CORDIS. 2024. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/434357-precision-tools-for-farming-mussels-and-oysters-more-sustainably (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- MIT News. Meet the Oystamaran; MIT News: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://news.mit.edu/2021/oystamaran-shellfish-aquaculture-1208 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Avdelas, L.; Avdic-Mravlje, E.; Marques, A.C.B.; Cano, S.; Capelle, J.J.; Carvalho, N.; Cozzolino, M.; Dennis, J.; Ellis, T.; Polanco, J.M.F.; et al. The decline of mussel aquaculture in the European Union: Causes, economic impacts and opportunities. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fish Site. New IoT Sensor Sheds Light on Shellfish Growers’ Farm Conditions. 2022. Available online: https://thefishsite.com/articles/new-iot-sensor-sheds-light-on-shellfish-growers-farm-conditions-s2aquacolab-wisar-lab (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Waryanto, W.; Zulkarnain, R. Automation Design of Kentongan Sound for The Feeding Process of Vaname Shrimp Farming in Pond. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chellapandi, P. Development of top-dressing automation technology for sustainable shrimp aquaculture in India. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Wang, W. Fish tracking, counting, and behaviour analysis in digital aquaculture: A comprehensive survey. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, E13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmadha, R.; Suryakanth, R.; Vikash, S.; Marimuthu, P. An Imaging In-Flow System for Automated Analysis of Quantifying postlarvae (Shrimp). In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Intelligent Information Systems (ICUIS), Gobichettipalayam, India, 12–13 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, F.; Zhang, H.; Du, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H. Effects of different aquaculture patterns on growth, survival and yield of diploid and triploid Portuguese oysters (Crassostrea angulata). Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, H.; Pierce, M.; Benter, A. Real-time environmental monitoring for aquaculture using a lorawan-based iot sensor network. Sensors 2021, 21, 7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donncha, F.; Akhriev, A.; Fragoso, B.; Icely, J. Forecasting closures on shellfish farms using machine learning. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 5603–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassetti, A.N.; Galdelli, A.; Mancini, A.; Punzo, E.; Bolognini, L. Underwater mussel culture grounds: Precision technologies for management purposes. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for the Sea; Learning to Measure Sea Health Parameters (MetroSea), Milazzo, Italy, 3–5 October 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sadrfaridpour, B.; Aloimonos, Y.; Yu, M.; Tao, Y.; Webster, D. Detecting and counting oysters. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Klahn, D.A. Design and Implementation of Control and Perception Subsystems for an Autonomous Surface Vehicle for Aquaculture. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, C.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Research Advances in Marine Aquaculture Net-Cleaning Robots. Sensors 2024, 24, 7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; Ahirwar, S.B.; Kanojia, S.; Rai, S.; Vidhya, C.S.; Gupta, S.; Nautiyal, C.T.; Nautiyal, P. Robot-assisted Aquaculture and Sustainable Seafood Production for Enhanced Food Security. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, B.; Pacheco, O.; Rocha, R.J.; Correia, P.L. Image-Based Shrimp Aquaculture Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Florida Blogs. New Technologies May Help Oyster Farmers Increase Their Harvests, Reduce Labor. 2024. Available online: https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/news/2024/08/28/new-technologies-may-help-oyster-farmers-increase-their-harvests-reduce-labor/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Cao, S.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, D.; Hong, J.; Ruan, C. Research on Automatic Bait Casting System for Crab Farming. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Electromechanical Control Technology and Transportation (ICECTT), Nanchang, China, 15–17 May 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pitakphongmetha, J.; Suntiamorntut, W.; Charoenpanyasak, S. Internet of things for aquaculture in smart crab farming. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1834, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokesbury, K.D.; Baker, E.P.; Harris, B.P.; Rheault, R.B. Environmental impacts related to mechanical harvest of cultured shellfish. In Shellfish Aquaculture and the Environment; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, C.; Heasman, K.; Smaal, A.; Jiang, Z. Mussel aquaculture. In Molluscan Shellfish Aquaculture: A Practical Guide; CABI GB: Wallingford, UK, 2021; pp. 107–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vidya, R.; Jenni, B.; Alloycious, P.S.; Venkatesan, V.; Sajikumar, K.K.; Jestin Joy, K.M.; Sheela, P.P.; Mohamed, K.S. Oyster Farming Techniques. 2020. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/103319335/The_20Blue_20Bonanza_2020.pdf#page=89 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Leavitt, D. The Oysterbot: Developing a Ropeless Bottom Cage Retrieval System for Nearshore Oyster Farms. 2023. Available online: https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/fne22-018/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Bellingham, J. How Are Marine Robots Shaping Our Future? JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, C.H.; Jeong, M.; Suh, J.H.; Lee, J. Development and Performance Evaluation of a Vision-Based Automated Oyster Size Classification System. Inventions 2025, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.N.; Lee, D.; Lee, H.J.; Huh, J.H. Grading Single Oyster based on Their Features Using AI Technologies. Korea Inst. Inf. Commun. Eng. 2025, 16, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Efficient and Non-Invasive Grading of Chinese Mitten Crab Based on Fatness Estimated by Combing Machine Vision and Deep Learning. Foods 2025, 14, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.-T.; Nguyen, T.-H.; Pham, M.-K. Towards Automatic Internal Quality Grading of Mud Crabs: A Preliminary Study on Spectrometric Analysis; Springer Nature: Can Tho, Vietnam; Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Huang, S.-T. Monitoring coastal aquaculture devices in Taiwan with the radio frequency identification combination system. GIScience Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, C.; Lees, D.; Hay, B. Depuration and relaying: A review on potential removal of norovirus from oysters. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syah, S.A.A.; Suryo, Y.A. Automatic Depuration System for Green Mussels (Perna viridis) to Support Food Safety. Jambura J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2025, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galosi, L.; Jacob, R.; Roberts, M.; Kluger, L.; Maurin, P.; Cornette, F.; Foucher, E.; Milani, A.; Le Grand, J.; Schaal, B. Evaluation of Mud Worm (Polydora spp.) Infestation in Cupped (Crassostrea gigas) and Flat Oyster (Ostrea edulis) Broodstocks: Comparison between Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography. Animals 2024, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramendia, J.; Navarro, A.; Garcia, M.; Etxabe, I.; Fernandez, J.; Arrese, A. Evidence of internalized microplastics in mussel tissues detected by volumetric Raman imaging. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; He, Y. Real-time monitoring of the quality changes in shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) with hyperspectral imaging technology during hot air drying. Foods 2022, 11, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Chen, G.; Kutsanedzie, F.Y.H.; Ahmad, W.; Khan, M.Z.H.; Awad, A.M.; Ali, M.M. Rapid noninvasive monitoring of freshness variation in frozen shrimp using multidimensional fluorescence imaging coupled with chemometrics. Talanta 2021, 224, 121871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, B.; Yang, W.; Hu, M.; Xie, Z.; Liu, J. Freshness identification of oysters based on colorimetric sensor array combined with image processing and visible near-infrared spectroscopy. Sensors 2022, 22, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, P.; Annamalai, J.; Anbalagan, S.; Ramachandran, D. Development of electronic nose (Shrimp-Nose) for the determination of perishable quality and shelf-life of cultured Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 317, 128192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, L.M.; Novamizanti, L.; Wijaya, D.R. Crab Quality Detection with Gas Sensors Using a Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things and Intelligence Systems (IOTAIS), Bali, Indonesia, 28–30 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhal, O.; Bouraoui, I.; Abdelhedi, R.; Ellouze, M. Coboshell Robot for Automatic Scallop Shelling Process: Concepts and Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), Seattle, WA, USA, 28–30 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz, J.S.; Lara-Padilla, H.; Rojas, T. Optimizing the Weighing Process in Frozen Shrimp Production for Export. In International Conference on Science, Technology and Innovation for Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shenghu, Z.; Yuting, W.; Yongjin, J. Mechanized Transformation in Shellfish Aquaculture: Practical Challenges and Intelligentization-Driven Breakthrough Pathways. Glob. Acad. Front. 2025, 3, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Regattieri, A.; Gamberi, M.; Manzini, R. Traceability of food products: General framework and experimental evidence. J. Food Eng. 2007, 81, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, D.P.; Getchis, T. Shellfish farming: Regulations, spatial planning, best practices, and certification. In Molluscan Shellfish Aquaculture: A Practical Guide; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2021; pp. 459–478. [Google Scholar]

- Johann, H.; Nysen, E.; Walker, J.; Brown, D. Regulatory Frameworks for Seafood Authenticity and Traceability. In Seafood Authenticity and Traceability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 9780128015926. [Google Scholar]

- Borit, M.; Olsen, P. Seafood Traceability Systems: Gap Analysis of Inconsistencies in Standards and Norms; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schrobback, P.; Pascoe, S.; Coglan, L. Challenges and opportunities of aquaculture supply chains: Case study of oysters in Australia. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 215, 105966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna García, M.; Ruiz-García, L.; López-Santamaría, E.; Pérez, A. Blockchain-based approach to the challenges of EU’s environmental policy compliance in aquaculture: From traceability to fraud prevention. In Marine Policy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; p. 105892. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Wen, G.; Chenxuan, C. Oyster cold chain logistics monitoring system based on RFID and cloud platforms. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Signal Processing and Computer Science (SPCS 2023), Guilin, China, 21 December 2023; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Gawai, A.; Asioli, D.; Nocella, G. US Consumer Valuation of Blockchain-Certified Traceability for Shrimp: Does Information Matter? In Proceedings of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, 2024 Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28–30 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gawai, A.S. On the Blockchain Adoption in Fisheries and Aquaculture Supply Chains: An Empirical Study on Indian Stakeholders’ Perceptions and the US Consumer Preferences for Blockchain-Enabled Shrimp Supply Chain. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Romdhane, S.F.; Zhang, K.; De Santa-Eulalia, L.A. Towards Efficient and Fine-Grained Traceability for a Live Lobster Supply Chain using Blockchain Technology. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 253, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriany, N.R.; Dewi, P.; Hartati, S.; Lestari, M. The effect of packaging process and price on the purchase decision of live lobster on consumers pt. Permata ningrat. Adv. Transp. Logist. Res. 2021, 4, 312–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schrobback, P.; Rust, S.; Ugalde, S.; Rolfe, J. Describing and Analysing the Pacific Oyster Supply Chain in Australia; Final Research Report; Central Queensland University: Rockhampton, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malingoen, V.; Sukcharoenpong, S. Development of Applications for Pacific White Shrimp and Giant Freshwater Prawn Farming. In Proceedings of the 14th NPRU National Academic Conference, Nakhon Pathom Rajabhat University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, 7 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Messer, K.D. To scan or not to scan. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2019, 44, 311–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kadhafi, D.; Surianto, M.A. Customer Satisfaction on the Use of QR Codes For Frozen Shrimp Products at PT. Kelola Mina Laut Based on the Theory of Stimulus Organism Response. Indones. Vocat. Res. J. 2022, 1, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, B.; Jacobson, R.B.; Roberts, M. Understanding the Role of Sediment Stability and Hydraulics of Mussel Habitat in a Dynamic Flow Regime. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts; Harvard University: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, A.; Ghosh, S.K. Rapid seafood fraud detection powered by multiple technologies: Food authenticity using DNA-QR codes. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 131, 106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, P.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, Z. Automatic monitoring of relevant behaviors for crustacean production in aquaculture: A review. Animals 2021, 11, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.A.; Farajzadeh, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Simic, M.; Hafeez, M.; Kim, J. Flexible tag design for semi-continuous wireless data acquisition from marine animals. Flex. Print. Electron. 2019, 4, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, R.; Fielke, S. Blockchain for trustworthy provenances: A case study in the Australian aquaculture industry. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, W.; Yahaya, S.Z.; Mohamad, N.; Nasir, M.; Rosman, M. Development of Smart Aquaculture Quality Monitoring (AQM) System with Internet of Things (IOT); IEEE: Perak, Malaysia, 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Syversen, T.; Vollstad, J. Application of radio frequency identification tags for marking of fish gillnets and crab pots: Trials in the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea, Norway. Fish. Res. 2023, 259, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveri, N. Progettazione e Sviluppo di un Sistema per la Valutazione in Tempo Reale Della Crescita di Mitili in Scenari di Acquacoltura di Precisione/Design and Development of a System for Real-Time Assessment of Mussel Growth in Precision Aquaculture Scenarios. Master’s Thesis, Polytechnic University of Marche, Ancona City, Italy, 16 February 2024. Available online: https://tesi.univpm.it/handle/20.500.12075/16586 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Khan, M.A.; Rahman, M.; Islam, M.R.; Rashed, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Rahman, M.S. Shrimpchain: A blockchain-based transparent and traceable framework to enhance the export potentiality of Bangladeshi shrimp. Smart Agric. Technol. 2022, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar]

- Schrobback, P.; Rolfe, J. Describing, Analysing and Comparing Edible Oyster Supply Chains in Australia. 2020. Available online: https://www.ruraleconomies.org.au/media/1295/oyster-supply-chain_final-report_recoe-schrobback-rolfe.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Miller, A.; Heggelund, D.; Mcdermott, T. Digital Traceability for Oyster Supply Chains: Implementation and Results of a Pilot; Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission: Ocean Springs, MS, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De, S.K.; Bhattacharya, K. The oyster collection algorithms. Evol. Intell. 2024, 17, 3985–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, P.; Cawthorn, D. Queensland Department of Primary Industries, 2025, Investigation and Improvement of Live Blue Swimmer Crab Handling in NSW, Brisbane. February 2025. Available online: https://era.dpi.qld.gov.au/id/eprint/14842/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Limpianchob, C.; Sasabe, M.; Kasahara, S. A multi-objective optimisation model for production and transportation planning in a marine shrimp farming supply chain network. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 45, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omobepade, B.P.; Adeyemi, O.; Adetunji, C.; Oladipo, A.; Akinyemi, O. Assessing transportation logistics for white shrimp (Nematopalaemon hastatus) marketing using arcgis network analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 655, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Rahman, T.; Hossain, M.; Islam, N.; Akter, S.; Hasan, M.M. Smart aquaculture analytics: Enhancing shrimp farming in Bangladesh through real-time iot monitoring and predictive machine learning analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eso, R.; Sari, D.; Putra, A.; Setiawan, R.; Dewi, N. Water quality monitoring system based on the Internet of Things (IOT) for vannamei shrimp farming. Comtech. Comput. Math. Eng. Appl. 2024, 15, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satriananda, S.; Arifin, R.; Hidayat, A.; Maulana, F.; Rahmawati, D. Monitoring and Controlling Overfeeding Ammonia in Smart Lobster Ponds based on Internet of Things Technology. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer and Information Technology (ICEECIT), Jember, Indonesia, 22–23 November 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Gao, Y. Modeling and evaluation on WSN-enabled and knowledge-based HACCP quality control for frozen shellfish cold chain. Food Control 2019, 98, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokaine, L.; Region, K.; Palm, O. Transportation and Packaging Aspects of Blue Mussel Farmed in the Baltic Sea; Interreg Europe: Lille, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Love, D.C.; Fry, J.P.; Milli, M.C.; Neff, R.A. Performance and conduct of supply chains for United States farmed oysters. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, S.; Exley, P. Improving Survival and Quality of Crabs and Lobsters in Transportation from First Point of Sale to Market; FRDC: Deakin, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, R.A.; Tapella, F.; Romero, M.C. Transportation methods for Southern king crab: From fishing to transient storage and long-haul packaging. Fish. Res. 2020, 223, 105441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnayake, R.L.; Silva, T.; Kumara, A.; Perera, M. Food Logistics: A Study on Lobster Fisheries, Sri Lanka. Res. Transp. Logist. Ind. 2022, 7, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; You, H. Delivery of Chinese mitten crab during peak season: Logistics dilemma for micro-e-businesses. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2018, 29, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, A.E.; Coronado, E.S.; Coronado, C.E. ITS and Smart Grid Networks for Increasing Live Shellfish Value. In Proceedings of the 10th ITS European Congress, Helsinki, Finland, 16–19 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Q. A new artificial intelligent approach to buoy detection for mussel farming. J. R. Soc. New Zealand 2023, 53, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnadurai, S.; Vijayakumar, S.; Sivakumar, S.; Kannan, R.; Raj, R. Development of a depuration protocol for commercially important edible bivalve molluscs of India: Ensuring microbiological safety. Food Microbiol. 2023, 110, 104172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, G.; Sharma, V.; Singh, R.; Jain, N.; Patel, D. Precision Aquaculture Framework for Remote Mussel Growth Monitoring with iot Blockchain and Cloud Integration. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for the Sea; Learning to Measure Sea Health Parameters (Metrosea), Portorose, Slovenia, 14–16 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W. Intelligent evaluation and dynamic prediction of oysters freshness with electronic nose non-destructive monitoring and machine learning. Biosensors 2024, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, L.; He, J. Rgo-PDMS Flexible Sensors Enabled Survival Decision System for Live Oysters. Sensors 2023, 23, 1308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, P.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Luo, Y. Flexible bioimpedance-based dynamic monitoring of stress levels in live oysters. Aquaculture 2023, 577, 739957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzza, L.; Riera, R.; Lopes, C.; Reis, D.B.; Valente, L.M.; Lemos, M.F.L. Preventing illegal seafood trade using machine-learning assisted microbiome analysis. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, Z. An explainable machine learning for geographical origin traceability of mussels Mytilus edulis based on stable isotope ratio and compositions of C, N, O and H. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 123, 105508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Tang, Q. Deep learning-based oyster packaging system. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, P.; Yang, F. Applications of colorimetric sensors for non-destructive predicting total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) content of Fujian oyster (Crassostrea angulata). Food Control. 2023, 153, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.F.; Almeida, C.M.; Gomes, T.; Lopes, J.; Santos, R. Can copper isotope composition in oysters improve marine biomonitoring and seafood traceability? J. Sea Res. 2023, 191, 102334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Senthilkumar, T.; Panigrahi, S.S.; Thirugnanam, N.; Kaushik Raja, B.K.R. Automation in the Shellfish Aquaculture Sector to Ensure Sustainability and Food Security. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110387

Senthilkumar T, Panigrahi SS, Thirugnanam N, Kaushik Raja BKR. Automation in the Shellfish Aquaculture Sector to Ensure Sustainability and Food Security. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(11):387. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110387

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenthilkumar, T., Shubham Subrot Panigrahi, Nikashini Thirugnanam, and B. K. R. Kaushik Raja. 2025. "Automation in the Shellfish Aquaculture Sector to Ensure Sustainability and Food Security" AgriEngineering 7, no. 11: 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110387

APA StyleSenthilkumar, T., Panigrahi, S. S., Thirugnanam, N., & Kaushik Raja, B. K. R. (2025). Automation in the Shellfish Aquaculture Sector to Ensure Sustainability and Food Security. AgriEngineering, 7(11), 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7110387