Abstract

In the context of museums’ transformation into active social agents, the Entre Luces (Between Lights) project, developed at the Pablo Gargallo Museum in Zaragoza, serves as a compelling example of accessibility understood as a shared cultural responsibility. Implemented within a listed heritage building, where structural modifications were not possible, the project deliberately shifted the focus from architectural accessibility to communicative, cognitive, and sensory dimensions, placing the quality of the cultural experience at the centre. The study employed a qualitative case study design based on document analysis, participant observation, and semi-structured interviews with museum staff, educators, and members of disability organisations. Through a participatory and iterative co-design process, curators, educators, vocational students, and disability organisations collaborated to develop inclusive solutions. People with disabilities were not regarded as passive users but as co-authors of the process: they contributed to the creation of tactile replicas, audio descriptions, sign language resources, braille, pictograms, and motion-activated audio systems. The project generated three main outcomes. It expanded cultural participation among people with diverse disabilities, enriched the sensory and emotional experience of all visitors, and initiated an institutional transformation that reshaped staff training, interpretive approaches, and the museum’s mission towards inclusivity. Entre Luces demonstrates that even small and medium-sized museums can overcome heritage constraints and promote cultural equity and social innovation through inclusive and sensory-based approaches.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary landscape, museums are evolving beyond their traditional roles of preservation, research, and education, becoming multifunctional institutions and active social agents [1]. This transformation positions them as vital spaces that address a wide range of cultural, educational, and social needs, actively promoting inclusion and accessibility as crucial elements for community cohesion and equal access to culture [1,2].

This evolution reflects a paradigmatic shift from the medical model to the social model of disability [3]. The focus shifts from individual pathology to environmental and cultural barriers that hinder participation. Within this conceptual framework, disability is recognised as a social and relational construct, and accessibility is no longer viewed as an exceptional measure but as a fundamental cultural right and a shared institutional responsibility [3,4].

The Entre Luces project, developed at the Pablo Gargallo Museum in Zaragoza, stands as a paradigmatic example of this integrated perspective. It demonstrates that accessibility is not merely a technical requirement but a continuous process of institutional transformation based on collaboration, sensory experience, and community engagement.

Launched in 2020 in the 17th-century Palace of the Counts of Argillo—a Bien de Interés Cultural protected under Spanish law—the project successfully combined regulatory rigour, design innovation, and collaborative co-creation, becoming an exemplary case of inclusive cultural accessibility. The museum, custodian of the works of Aragonese sculptor Pablo Gargallo, created a dedicated tactile room that addressed accessibility through sensory, cognitive, and communicative resources, including tactile replicas, audio descriptions, sign language, braille, pictograms, and podotactile guidance systems.

The implementation of this social function varies considerably across national contexts. While some countries favour models based on direct community participation, others adopt more centralised regulatory models. In Spain, Real Decreto Legislativo 1/2013 sought to align regulatory approaches with community initiatives, yet few institutions have achieved full accessibility certification, revealing a gap between policy and practice [5]. This situation underscores the need to translate programmatic statements into concrete, participatory, and sustainable practices. This gap between regulation and implementation provides the rationale for the present study.

These practices should be capable of breaking down cognitive, sensory, and symbolic barriers [6,7].

In this study, accessibility is not defined as physical or architectural modification—often impossible in protected heritage sites—but as the removal of communicative, cognitive, and sensory barriers through multisensory and inclusive strategies. Museum accessibility thus emerges as a transversal dimension of cultural action, encompassing communication, education, governance, and technology [7,8].

While the inclusive function of museums receives increasing attention in both academic literature and institutional discourse, many studies adopt a normative or policy-driven perspective, often neglecting the practical processes through which accessibility is implemented, negotiated, and sustained within museum institutions. A rigorous analysis of the literature reveals that, although the transformative potential of accessibility initiatives is recognised [1,2], there is limited empirical evidence on how theoretical frameworks are translated into contextualised co-design practices in these environments [6,7,9]. This study seeks to address this gap by providing a detailed understanding of how collaboration and participatory design can enhance sensory and cognitive accessibility in museums.

This study aims to contribute to the growing body of literature on participatory accessibility by analysing the Entre Luces project as an example of inclusive co-design in a museum context. The research explores how accessibility is achieved not only through technical adaptations but also co-produced through collaborative, sensory, and pedagogical practices involving users with disabilities as co-creators. The theoretical approach draws on the social model of disability [3], inclusive museum studies, and Universal Design for Learning, framing accessibility as a cultural right and a shared institutional responsibility [2,4]. This work addresses a key gap in the literature by documenting how these conceptual frameworks are translated into practice through localised, iterative, and context-sensitive processes of transformation.

Building on this theoretical framework, the present study analyses Entre Luces as an applied example of how accessibility can be redefined as a co-created, sensory, and communicative practice within a heritage context, addressing a gap in museology research that often lacks empirical accounts of implementation.

Research Questions:

- How can sensory and communicative accessibility be co-designed and implemented in museums through participatory practices?

- What forms of institutional transformation arise when accessibility is approached as an inclusive, sensory-based, and community-driven?

2. Materials and Methods

This study uses a qualitative, descriptive case study design to investigate the Entre Luces project at the Pablo Gargallo Museum in Zaragoza (Spain). The case study approach was chosen for its ability to provide an in-depth, holistic, and contextualised understanding of complex phenomena within real-world settings [10]. This methodology is particularly suited to exploring intricate relationships, processes, and transformations within integrative museum contexts, especially when examining how diverse forms of knowledge and collaboration inform inclusive practices. Although case studies have been criticised for limited generalisability, their value lies in generating rich, empirically grounded data that illuminate specific, complex realities. The aim of this research is not to produce universally generalisable findings but to offer transferable insights into co-designing accessibility in a historical cultural heritage site.

The methodological framework was based on the triangulation of three primary qualitative tools: document analysis, participant observation, and semi-structured interviews. This multi-method strategy was employed to ensure a comprehensive and multi-perspective understanding of the Entre Luces project, combining institutional, experiential, and interpretive dimensions. Triangulation is a critical technique in qualitative research that enhances trustworthiness, credibility, and rigour by cross-verifying data from different sources and methods, thereby mitigating potential biases inherent in single-method approaches [11,12,13]. Qualitative researchers agree that practices such as triangulation can increase the credibility, rigour, and trustworthiness of their research [11]. Each method contributed uniquely to capturing the complexity of inclusive practices: documents provided technical and strategic insights; observation enabled direct engagement with user interactions and educational activities, revealing nuances often unarticulated; and interviews elucidated the motivations, reflections, and critical feedback of key stakeholders.

Data were systematically collected through this triangulated approach, involving diverse groups directly engaged in the Entre Luces project, including museum staff, accessibility experts, representatives of social organisations, and individuals with disabilities.

2.1. Data Collection Methods

2.1.1. Document Analysis

The document analysis included official sources related to the mission and vision of Zaragoza’s municipal museums, as well as comprehensive project documents, activity reports, and museum communication materials. Key internal documents, such as the Informe de proyecto Entre Luces, were provided by the project coordinators for research purposes. These documents, although not publicly accessible, were used with explicit permission and offered critical insights into the project’s inception, planning, and execution. Particularly important were materials concerning the design and implementation of the “Entre Luces” tactile space, including descriptions of accessible resources, technical documentation on tactile replicas, and protocols for collaboration with involved associations and entities (e.g., ONCE—Organización Nacional de Ciegos Españoles; Fundación DFA—Fundación Disminuidos Físicos de Aragón; ATADES—Asociación Tutelar Aragonesa de Discapacidad Intelectual; Colegio La Purísima para niños sordos de Zaragoza). This enabled a detailed understanding of the project’s institutional goals and technical design.

2.1.2. Participant Observation

Participant observation enabled immersive documentation of internal educational practices and direct engagement with the Entre Luces project as it unfolded. This method facilitated the recording of experiential dynamics and non-verbal feedback from both educators and visitors with disabilities, offering a lived perspective on the implementation of inclusive strategies. Approximately 20 individuals were observed during various activities within the museum, providing rich contextual data.

2.1.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

A total of nine individuals participated in semi-structured interviews. The interviews employed a dialogical and reflexive approach, providing direct information about the inclusive design process, operational choices, applied accessibility criteria, and end-user perceptions. Particular attention was given to the role of social consultations in defining accessible tools and the ongoing adaptation of available resources. Interviewees included institutional representatives from Zaragoza Museos and the Department of Culture, project partners from Serendipia Gestión Cultural, and members of ONCE and other functional diversity collectives. Data collection techniques were adjusted according to the role and level of involvement of each group to ensure methodological triangulation. Interviews were conducted through a combination of in-person meetings and videoconference sessions to accommodate participants’ needs. All interviews were audio-recorded with prior informed consent and subsequently fully transcribed, ensuring anonymity throughout the process.

2.2. Sample Composition and Justification

The sample selected for this study reflects a deliberately diverse and strategic composition, aiming to represent the main actors involved in the co-design process of the Entre Luces project. As a case study informed by participatory principles, the research design prioritised depth of understanding from key stakeholders over statistical generalisability [10]. Data were collected both during the implementation of the Entre Luces project (2020–2023) through participant observation and interviews, and retrospectively through the analysis of project reports and documentation. This combined timeline enabled us to capture both the experiential dynamics of the project as they unfolded, and the institutional reflections documented after implementation.

Stakeholders were selected for their direct involvement in the Entre Luces project, ensuring a balance between institutional actors, technical experts, and user representatives. Given the focused scope of the case study, data saturation was assessed pragmatically: convergence of themes across interviews was reached with the ninth respondent, and no new categories emerged, indicating the adequacy of the sample. Saturation was validated through iterative review of transcripts and comparison of emergent codes; after nine interviews no new themes appeared, confirming adequacy of sample size for thematic depth. All individuals invited to participate in the interviews accepted, ensuring a consistent and reliable data collection process. Of the nine interviewees, seven were already part of association networks active in the field of accessibility and inclusion.

The composition of the sample and the data collection tools are summarised in Table 1, which shows the methods, groups involved and purposes of each method.

Table 1.

Summary of methods and participants.

As shown in Table 1, the research design relied on methodological triangulation, combining qualitative observation, co-design workshops, and structured feedback sessions. The involvement of advocacy groups and educational institutions ensured a multidimensional understanding of accessibility, linking experiential, pedagogical, and institutional perspectives.

While the inclusion of individuals from advocacy groups might suggest potential bias, their experiential expertise provided valuable insights for assessing accessibility quality and identifying specific areas for improvement. This apparent bias was rigorously addressed through two main strategies. Firstly, the diversity of data collection methods (interviews, observations, document analysis) enabled robust triangulation of sources, mitigating the influence of individual perspectives and providing a more balanced view [11,13]. Secondly, the diversification of the overall sample—which included educators, members of the associations and entities involved in the project, and members of the museum management—ensured a balance of narratives, incorporating perspectives beyond those of highly involved advocacy groups. Furthermore, the aim of this study was not to produce a representative average of generalisable opinions, but to examine in depth key experiences within a co-design process. In this sense, the contribution of the associated participants, who had greater critical awareness and experiential expertise, provided invaluable information to assess the quality of accessibility and identify targeted areas for improvement. Therefore, their prominent presence in the sample not only does not affect the validity of this in-depth case study, but rather represents an added value in terms of the richness and relevance of the findings.

2.3. Data Analysis

Qualitative data from interviews, observations, and documents were analysed thematically, with key emergent categories identified inductively in line with a grounded approach. This process enabled the development of a conceptual model directly from the research findings [14]. Thematic analysis, a widely used and flexible method in qualitative research, was systematically applied through several stages to ensure rigour and depth of insight [14]. This involved familiarising oneself with the data through repeated reading of transcripts and documents; generating initial codes by identifying recurrent patterns and salient points related to the research questions; searching for themes by grouping similar codes into broader categories; reviewing themes to ensure they accurately reflected the data and addressed the research questions; defining and naming themes, clearly articulating their essence; and producing the report, integrating themes into a coherent narrative supported by evidence [14].

The processing was conducted manually and supported by basic digital tools (e.g., spreadsheets and text processing), which facilitated the organisation of codes, comparison between sources, and identification of transversal repetitions.

Preliminary coding validation was conducted by two researchers independently; coding discrepancies were discussed until full agreement was reached. Digital spreadsheets ensured traceability and transparency of coding decisions was used.

Particular attention was given to identifying thematic cores related to the perception of accessibility, participatory involvement, and the experiential impact of the project. This systematic approach to thematic analysis directly informed the development of a robust conceptual framework, illustrating how raw data can be transformed into meaningful theoretical insights [14].

2.4. Ethical Considerations

No formal ethical approval was required, in accordance with Spanish national guidelines for research in the humanities and social sciences (Ley Orgánica 3/2018 on data protection and the institutional regulations of the University of Zaragoza).

The study followed the ethical principles of informed consent, voluntary participation, and confidentiality. No sensitive personal data were collected, and all participants could withdraw at any stage. Data were anonymised and stored securely in line with GDPR requirements.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and anonymity was guaranteed throughout the research process.

3. Results

The Entre Luces project, initiated in 2019 and developed through 2023, effectively addressed existing accessibility constraints at the Pablo Gargallo Museum by creating a sensory-based space designed according to universal accessibility principles. This initiative represents a significant paradigm shift in inclusive museum practice. The findings are organised into the following key thematic areas, reflecting the project’s multifaceted impact on collaborative design, visitor engagement, educational outcomes, and institutional transformation.

3.1. Collaborative Design and Iterative Development

3.1.1. Objective Results

The Entre Luces project adopted an innovative collaborative model established through agreements with local educational and social entities, notably Grupo San Valero, a vocational training and education centre in Zaragoza. This collaboration created a governance structure involving six stakeholder groups, each contributing specific expertise to the design process: museum curators, vocational students from San Valero, ONCE (visually impaired), Onda Educa Técnica (technical implementation), Serendipia (public programming), and DFA/ATADES (user experience evaluation). Their respective roles are summarised in Table 2, which illustrates the horizontal rather than top-down governance model adopted.

Table 2.

Stakeholder Roles and Contributions.

As shown in Table 2, this distribution of roles formalised an iterative governance model rather than a top-down model.

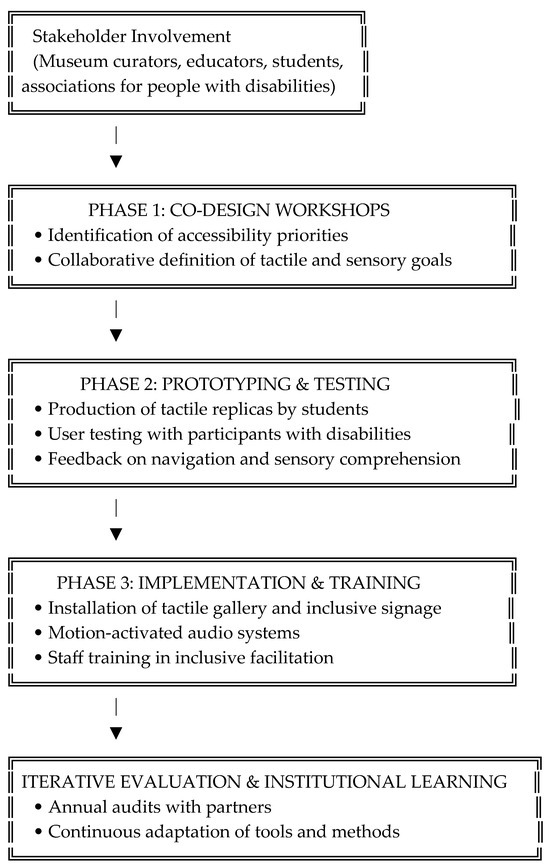

The collaborative process took place in three phases over eighteen months.

- -

- Co-design phase (June–August 2020): four participatory workshops with disability advocates, educators, and museography experts established tactile engagement as the interpretive priority.

- -

- Prototyping phase (September–November 2020): vocational students produced three test replicas using Gargallo’s techniques. These prototypes were evaluated in twelve testing sessions involving fifteen visually impaired participants from ONCE and eight individuals with cognitive disabilities from ATADES. Feedback on spatial navigation and multisensory information delivery informed the final design.

- -

- Implementation phase (December 2020–March 2021): specialist staff training on inclusive facilitation improved confidence in engaging mixed-ability groups, as reflected in post-implementation surveys.

The project’s iterative approach also influenced its digital integration. Initial smartphone-based QR code content was replaced by proximity-activated audio stations after user testing revealed difficulties for visually impaired visitors during tactile exploration. Additional design refinements included adjustable sculpture mounts (90–120 cm) to improve wheelchair access and simplified tactile guidance paths (T-junctions). These exhibit-level adjustments enhanced interpretive and sensory accessibility without altering the building’s protected structure.

Table 3 summarises these key design changes, each derived directly from user testing feedback rather than abstract accessibility standards.

Table 3.

Design Evolution of Key Components.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Entre Luces co-design process was articulated through three iterative phases—co-design, prototyping, and implementation—developed in collaboration with multiple stakeholder groups. Each phase built upon the results of the previous one, integrating continuous feedback from users with disabilities and museum professionals. This cyclical model ensured that accessibility was not a one-time adaptation, but an evolving institutional practice grounded in collaboration and experiential learning.

Figure 1.

Workflow of Entre Luces Co-Design and Implementation Process.

3.1.2. Interpretive Insights

Beyond technical and spatial adjustments, the participatory design process generated broader organisational change. The museum appointed dedicated staff for accessibility initiatives, established annual accessibility audits with San Valero, and formally incorporated user feedback into programme evaluation. Observations confirmed that the sensory-based design effectively addressed a variety of access needs—visual, auditory, motor, and cognitive—suggesting that inclusive co-design can operate as a catalyst for institutional learning.

The following section interprets these results in relation to educational outcomes and staff development, highlighting how the Entre Luces experience contributed to a redefinition of institutional practice.

3.2. Different Target Groups

This section reports descriptive participation data and audience engagement patterns (different target groups), whereas Section 3.3 addresses how these interactions translated into educational outcomes and structural change within the museum.

Since its opening, the Entre Luces gallery has welcomed 37,392 visitors. Of these, approximately 500 individuals with various disabilities participated in 45 guided sessions specifically designed to ensure accessibility. These sessions, lasting about 75 min, were tailored to accommodate people with visual, auditory, cognitive, and mobility-related disabilities, and were coordinated in collaboration with organisations such as ONCE, Fundación DFA, ATADES, and Fundación San Valero.

Although no disaggregated statistics by disability type or frequency of attendance were collected, feedback from participants, caregivers, and educators has consistently indicated a high level of engagement and comfort. These outcomes reflect a strong institutional commitment to accessibility and have helped shape inclusive programming strategies for the museum’s future.

Evaluation of the Entre Luces experience was qualitative, based on mediator observations, visitor comments, and interviews with staff and educators. Although not formally systematised, these accounts consistently highlighted the emotional impact of the tactile experience and its capacity to enable inclusive, multisensory engagement for diverse audiences.

In 2024, 16% of the gallery’s visitors were from outside Spain, indicating growing international interest in the museum’s inclusive practices. This trend underscores the project’s broader potential to engage audiences beyond the regional context.

Staff reflections indicated that the tactile stations played a central role in fostering interaction and mutual discovery, often serving as “equalisers” that encouraged spontaneous dialogue among visitors of different abilities.

The educational dimension of the project was particularly significant. School groups and vocational students from institutions such as Fundación San Valero and IES María Moliner actively participated in guided visits and collaborative learning activities. Educators noted increased awareness of accessibility and inclusion among students, especially in response to the sensory-based approach adopted in the gallery. The educational outcomes included both anecdotal evidence (reflective narratives from teachers and mediators) and evaluative data (survey responses and visitor satisfaction questionnaires), which are distinguished in the reporting of results.

Overall, the Entre Luces project has contributed to three interrelated outcomes: fostering cultural participation among people with disabilities; enriching the sensory and emotional experience of museum visitors; and increasing the museum’s visibility within and beyond the local context.

3.3. Educational Outcomes and Institutional Transformation

This section presents two interconnected result areas: (i) educational outcomes emerging from collaboration with vocational training programmes and school groups; and (ii) institutional transformation in terms of staff practices, evaluation criteria, and mission.

- (i)

- Educational outcomes

The Entre Luces project brought about meaningful changes in educational and institutional practices, resulting in a transformative impact that went beyond improvements in physical accessibility. A key educational aspect was the collaboration with Centro San Valero’s vocational training programme in welding and metalwork. Building on their technical contribution to the tactile replicas, students reflected on their social role as creators of accessible art. According to the project documentation, this partnership achieved three interconnected outcomes: students gained practical experience in reproducing Gargallo’s sculptural techniques using metal sheets; they engaged with broader issues of accessibility and inclusion through exposure to inclusive museography; and the project provided a context where technical training intersected with social responsibility. As welding instructor Jesús Gazol stated, “The replica production shifted from being an exercise in craftsmanship to a lesson in social responsibility. Students discovered their technical skills could literally make art accessible.” While specific metrics such as training hours, assessment scores, or employment figures are mentioned in internal evaluations (e.g., Informe de proyecto), their details are not included in the publicly available didactic guides.

- (ii)

- Institutional transformation

At the institutional level, the project is credited with prompting an internal shift in staff practices and interpretive approaches. A summary of these reported transformations is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Synthesis of reported transformations.

Although a formal comparative framework is not presented in public-facing documents, internal reports have noted a change in how success metrics are defined—moving from quantitative visitor counts to qualitative engagement measures—and an increased reliance on dialogic facilitation over traditional didactic tours. Staff development has reportedly expanded to include more frequent and participatory formats, such as inclusive practice labs. Table 4 outlines a representative synthesis of these reported transformations.

As indicated in Table 4, the definition of success moved from ‘how many visitors’ to ‘quality of engagement’, marking an institutional turn.

Further developments, as outlined in institutional reflections, indicate a growing internal dialogue on accessibility, the adoption of more inclusive interpretive strategies aligned with universal design principles, and the gradual integration of inclusive methodologies into everyday museum operations.

The museum’s pedagogical evolution followed a trajectory rooted in experimentation and co-creation. Initially focused on adapting existing programmes to meet access needs, the educational strategy progressively incorporated collaborative initiatives developed with disability organisations. This inclusive approach culminated in co-designed programmes, occasionally co-led by individuals with disabilities. A key example is the flagship activity Manos a la obra, a tactile interpretation workshop in which visitors with and without disabilities collectively explore artworks. The workshop embodies the museum’s renewed educational model, grounded in dialogue and participation.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of Entre Luces is reflected in the museum’s updated mission statement, adopted in 2023: “To foster participatory cultural encounters where diverse abilities spark new ways of experiencing art”. According to internal communications, this conceptual shift has coincided with increased community engagement, expanded partnerships, and a reallocation of institutional resources to sustain inclusive initiatives. While detailed financial or staffing data have not been publicly disclosed, reported outcomes include a rise in collaboration proposals, increased staff awareness, and a stronger institutional commitment to inclusive programming.

Collectively, these developments suggest that accessibility-focused projects can serve as catalysts for broader institutional transformation. In the case of Entre Luces, inclusive design extended beyond visitor-facing infrastructure to reshape pedagogical models, staff practices, and organisational identity. This case reinforces the notion that the most profound impacts of accessibility initiatives may reside not only in what changes for visitors, but in how institutions evolve in response.

3.4. Accessibility as an Ongoing Process

The Entre Luces project viewed accessibility not as a fixed goal but as a dynamic, evolving institutional practice. Instead of following a rigid model, the team adopted a flexible, collaborative approach based on dialogue with educators, disability organisations, and cultural mediators.

Improvements to the tactile gallery developed over time through feedback gathered via observation, informal interviews, and direct interaction with users. Although no formal framework or quantitative monitoring system was used, the museum adjusted key aspects—such as signage clarity, room flow, and interpretative materials—based on experiential learning and reflective dialogue.

The museum also explored basic technological enhancements, including QR-linked audio guides, subtitled videos, and magnetic loops for hearing aid users. These adaptations enhanced the multisensory quality of the experience and provided a foundation for further development.

Institutional commitment to inclusion was also demonstrated through sustained partnerships with organisations such as ONCE, Fundación DFA, ATADES, and Fundación San Valero. Rather than following a prescriptive protocol, Entre Luces exemplifies how inclusive design can emerge through gradual, situated, and human-centred processes in heritage institutions.

3.5. Internal Evaluation and Impact Indicators

To monitor the effectiveness of the Entre Luces project, the Pablo Gargallo Museum defined a set of strategic objectives aligned with its social and educational mission, accompanied by measurable impact indicators. This framework—including elements such as the economic sustainability of the project through the valorisation of tactile replicas and the identification of social beneficiaries—is documented in the Informe de proyecto Entre Luces, a non-public internal report made available to the research team by the organising institutions.

These objectives include:

- Integrating the Gargallo legacy into local school curricula, assessed by the number of schools and classes involved, and qualitative feedback from students and teachers.

- Increasing youth participation, as measured by the 15–20 age group.

- Improving the accessibility of the museum, measured by the number of tactile replicas produced and the range of inclusive aids implemented.

- Implementing customised routes and activities for groups with functional diversity, accompanied by direct observations and evaluations after the activity.

- Establishing stable collaboration with the city’s educational and social networks, measured by the number of partner organisations involved.

- Disseminating the project through a travelling exhibition in secondary schools, documented by the number of locations and participants.

- Ensuring economic sustainability through the valorisation of artistic replicas, with monitoring of sales, related activities, and social beneficiaries of the income.

Although aggregated longitudinal data are not yet available, the museum has achieved some significant preliminary results. The Entre Luces space has recorded around 100 specific visits since its opening, of which more than 60 per cent have been from people with disabilities. The geographical distribution of visitors indicates an impact on several levels: 63 per cent from Zaragoza and Aragon, 21 per cent from the rest of Spain, and 16 per cent from abroad (mainly France, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

These findings confirm the validity of the chosen approach, showing its potential for replication in similar museum contexts as a tool for cultural innovation and social inclusion. They also offer the empirical foundation for discussing how the project aligns with broader theoretical and normative frameworks of accessibility.

4. Discussion

The Entre Luces project, implemented at the Pablo Gargallo Museum, exemplifies the practical application of theoretical and normative principles of cultural accessibility in museum contexts. While the project could not address architectural barriers due to heritage restrictions, it successfully redefined accessibility as a communicative, cognitive, and sensory-based practice.

This redefinition was concretely realised through multisensory devices such as tactile replicas, proximity-activated audio stations, and adjustable mounts co-designed with users, which collectively reshaped the visitor’s perceptual experience. Quantitatively, between 2020 and 2023 the new tactile gallery hosted more than 70 inclusive group visits involving approximately 500 participants with disabilities, out of a total of about 37,000 visitors. Post-visit questionnaires revealed that 89% of participants with disabilities rated the tactile gallery as “fully accessible,” compared with 12% for the main galleries.

The results presented in the preceding sections therefore demonstrate the tangible possibility of moving beyond a purely adaptive approach—still prevalent in many European exhibition settings—toward a creative, integrative, and multisensory aesthetic experience.

4.1. Interpretive Reflections

Theoretically, Entre Luces is grounded in a conception of accessibility that goes beyond the removal of physical or informational barriers, framing it instead as a cultural right and a prerequisite for full participation in social life [15]. This approach aligns with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), particularly Articles 9 and 30, which emphasise cultural participation and accessibility as human rights [4,16,17]. Within Entre Luces, these principles were operationalised through co-design workshops involving users with functional diversity and by embedding accessibility criteria into each design iteration.

Accessibility thus became an integral part of the museum’s institutional identity [1]. The project required a restructuring of internal processes and the active involvement of diverse stakeholder groups, confirming the ongoing shift in museology from “cultural authority” toward participatory dialogue and democratisation [18,19]. This repositioning was reflected in the museum’s internal reorganisation, the appointment of dedicated accessibility staff, annual accessibility audits, and the 2023 mission statement centred on participatory cultural encounters.

From a normative perspective, Entre Luces fully aligns with the UNCRPD framework and the European Disability Strategy, and it concretely embodies the objectives of Spain’s Ley 1/2013 on the rights and inclusion of persons with disabilities [20,21]. The museum interpreted these obligations not as bureaucratic compliance but as an ethical commitment, turning regulation into sustained institutional learning [22].

The participatory approach adopted throughout the project reflects the principles of inclusive design, advocating for the direct involvement of people with disabilities in all decision-making and design phases. This ensured that user feedback from organisations such as ONCE and ATADES directly shaped the final outcomes—from prototype testing of tactile panels to the refinement of audio guides—reducing the risk of technocratic or top-down solutions [23,24,25].

Empirically, the participation of users and partner organisations generated richer and more sustainable museum experiences. Internal evaluations indicated that inclusion not only broadened the museum’s audience but also transformed its collective image into a more open and relational space, fostering empathy and active citizenship [26]. These transformations, summarised in Table 4, document the measurable shift from quantitative visitor counts toward qualitative indicators of engagement and inclusion.

At the same time, the project highlights accessibility as an ongoing, iterative process requiring continuous feedback and flexibility. The decision to replace smartphone-based QR systems with motion-activated audio stations exemplifies design adaptation based on real-world usability testing. As noted earlier (Table 3), such modifications—including adjustable mounts and simplified tactile paths—were informed directly by user testing rather than prescriptive standards.

This iterative practice reflects core principles of Universal Design for Learning, which advocate adaptability in materials and engagement modes to accommodate diverse learners. The ethnographic feedback strategies used (observation, interviews, qualitative analysis) further emphasise the importance of recognising the complexity of museum interactions.

The involvement of vocational students from the San Valero Centre also generated measurable educational benefits: 30 students participated in replica fabrication and accessibility audits, reporting increased awareness of social responsibility in post-activity reflections. This confirms that project-based learning linking technical competence with civic engagement can produce both professional and ethical growth [23,24,25].

When contextualised within broader European experiences, Entre Luces demonstrates a distinctive contribution. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has developed extensive accessibility measures [27], but often as service add-ons rather than co-designed features. Similarly, the Museo Tiflológico in Madrid, created by ONCE, was conceived for visually impaired audiences rather than adapting a heritage environment [28,29]. Entre Luces, by contrast, was realised in a historically protected building through a participatory and iterative process that balanced architectural constraints, educational objectives, and community empowerment.

This hybrid model is particularly relevant for small- and medium-sized museums, which are often embedded in local networks that facilitate collaboration. Physical and social proximity between institutions and communities fosters trust, reciprocity, and responsiveness—conditions that underpin the success of inclusive, co-designed cultural practices.

The combination of co-creation, iterative testing, and institutional embedding of accessibility documented throughout the project therefore supports the transferability of this model to other heritage or resource-constrained museums seeking to operationalise accessibility as a shared cultural responsibility.

4.2. Distinctive Features of Entre Luces in the European Context

While numerous European initiatives—such as the ARCHES (Accessible Resources for Cultural Heritage EcoSystems) project, COME-IN! (Cooperating for Open Access to Museums for All), and Museum4All—have promoted accessibility in cultural heritage, most have focused primarily on technological innovation, digital mediation, or physical adaptation of spaces.

Entre Luces, by contrast, was developed within a protected heritage building, where architectural modifications were legally constrained. Its innovation lies in redefining accessibility as a communicative, sensory, and institutional process, implemented through an iterative co-design model that engaged curators, educators, students, and disability organisations as co-authors rather than beneficiaries.

This situated and participatory methodology distinguishes Entre Luces from many European museum accessibility programmes, which often remain top-down or project-based. Instead of delivering a fixed set of assistive tools, Entre Luces embedded accessibility into the museum’s organisational culture, resulting in long-term transformation of staff practices, visitor engagement, and mission statements.

Moreover, while projects like the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Access Programme or the Museo Tiflológico have advanced sensory accessibility through large-scale infrastructures, Entre Luces demonstrates that small and medium-sized institutions can achieve comparable impact through collaborative, low-cost, and community-driven strategies. This makes it a transferable model for other European heritage contexts seeking to operationalise accessibility as a shared cultural responsibility rather than a technical add-on.

5. Conclusions

The Entre Luces case illustrates how participatory co-design can operationalise accessibility as a multidimensional cultural practice in heritage settings. Developed within the structural constraints of a listed building, the project demonstrates that accessibility can be achieved through communicative, sensory, and educational strategies rather than architectural modification.

By combining co-creation, iterative evaluation, and cross-sector collaboration, Entre Luces transformed accessibility from a technical requirement into an institutional and cultural process that reshaped professional practices, staff training, and visitor engagement. The project thus evidence how inclusive and sensory-based design can generate meaningful museum experiences while fostering organisational learning and social responsibility.

The study contributes to inclusive museology by demonstrating a transferable framework that integrates co-creation, multisensory engagement, and institutional learning. These insights may inform replication in other heritage contexts and guide policy initiatives aimed at cultural equity and the sustainable implementation of accessibility in small and medium-sized museums.

By linking participatory practice, multisensory interpretation, and institutional learning, the study advances current debates in inclusive museology and provides a replicable framework for heritage institutions seeking to align accessibility with social innovation.

6. Limitations of the Study

This study provides an in-depth analysis of the Entre Luces project; however, several limitations must be acknowledged to properly interpret its findings.

First, as a qualitative single-case study, the research offers context-specific insights that may not be directly generalisable to other museums operating under different structural, normative, or cultural conditions. This limitation affects external validity, as the patterns observed may reflect the specific institutional dynamics of the Pablo Gargallo Museum. Future research should therefore adopt multi-case or comparative designs to test whether similar institutional transformations occur across diverse settings.

Second, the study primarily reflects the initial phase of the project, since longitudinal data were not yet available. This temporal restriction limits the ability to assess the durability and sustainability of the inclusive practices introduced. As a result, the findings mainly represent short-term transformations and may not capture potential regression or consolidation effects. Longitudinal follow-ups would be necessary to evaluate whether the observed institutional and educational changes persist over time.

Third, although qualitative observations and participant feedback provided rich interpretive data, standardised instruments were not employed to measure educational, cultural, or psychological outcomes. This methodological choice may introduce a degree of subjectivity and limit the reliability and comparability of the results with other studies. Nevertheless, credibility was enhanced through methodological triangulation involving multiple data sources (participants, educators, curators) and analytical perspectives. Future studies could strengthen methodological robustness by combining qualitative insights with quantitative or psychometric tools.

Fourth, the involvement of specific advocacy groups (e.g., ONCE and ATADES) ensured expert representation of functional diversity but may also have produced selection bias, as the experiences of other disability communities were not equally represented. This limits the comprehensiveness of the findings. Future research should aim to include a broader spectrum of participants and user profiles to capture greater heterogeneity of needs and perspectives.

Fifth, some data were derived from internal project reports and institutional documents that are not publicly accessible. This reliance on internal materials may reduce external verifiability and introduces the possibility of reporting bias. To enhance transparency and replicability, future studies could make anonymised datasets or summary documentation available in open-access repositories.

Sixth, the relatively small number of interviewees and observed participants, while sufficient for qualitative depth and data saturation within this case, restricts the range of perspectives included. This affects the breadth but not the internal validity of the findings. Future research could employ larger samples or mixed methods to cross-validate results across participant groups.

Finally, the unique historical and community context of the Pablo Gargallo Museum—its scale, heritage constraints, and civic mission—adds both specificity and limitation. These factors shape the interpretive framework of accessibility adopted here and may not be fully transferable to larger institutions or different governance models. Future comparative studies should therefore consider contextual adaptation as an analytical variable rather than a constraint.

In summary, these limitations do not undermine the validity of the study but rather define its scope. Acknowledging them clarifies the interpretive boundaries of the findings and identifies avenues for future research aimed at testing, refining, and extending the model of inclusive museology explored in Entre Luces.

7. Future Research Directions

The Entre Luces project has established important foundations for inclusive and multisensory museum design, yet several promising avenues remain for further scholarly exploration. Future research could use a longitudinal approach to assess the sustainability and long-term impact of these inclusive practices. This would involve tracking changes in cultural participation, educational outcomes, and community engagement over an extended period.

Furthermore, comparative studies across diverse European heritage institutions—particularly those located in architecturally protected buildings—would provide invaluable insights into the broader applicability and transferability of the co-design model pioneered in Zaragoza. Such comparisons could help identify context-specific challenges and highlight best practices in operationalising accessibility as a fundamental cultural responsibility.

A key recommendation for future research is the integration of standardised evaluation tools to complement qualitative methodologies. Instruments such as the Museum Experience Scale, the Generic Learning Outcomes framework, or bespoke accessibility assessment protocols could enable more systematic measurement of educational and experiential impact, as well as facilitate benchmarking across institutions. These tools would be especially useful in documenting the perceptions and outcomes of diverse visitor groups, including persons with disabilities, and in mitigating potential researcher subjectivity.

Additionally, future studies could examine how emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence and adaptive interfaces, might support personalised yet inclusive museum experiences. This examination should critically consider how such technologies can be integrated without diminishing the immediacy and multisensory richness that are hallmarks of the Entre Luces approach, ensuring that technology enhances, rather than replaces, human-centred engagement.

8. Recommendations and Policy Implications

The Entre Luces project provides valuable insights into how inclusive museology can be implemented in practice, especially within the constraints of historically protected buildings and limited institutional resources. Several strategic recommendations arise from the project’s outcomes that can inform both professional practice and cultural policy frameworks.

From a practitioner’s perspective, the experience highlights the importance of adopting co-design methodologies that actively involve individuals with disabilities not merely as beneficiaries, but as co-creators in the design and implementation of accessibility measures. The use of participatory workshops and iterative prototyping enabled the Pablo Gargallo Museum to tailor its solutions to actual user needs, thereby improving both functionality and user engagement. This participatory approach also fostered a sense of shared ownership, encouraging deeper institutional and community commitment to inclusive values.

Furthermore, the project highlights the need to prioritise multisensory experiences as a central interpretive strategy. Moving beyond visually centred display modes, Entre Luces successfully integrated tactile replicas, motion-activated audio descriptions, and materials of diverse textures to accommodate a variety of sensory needs. These elements were not only inclusive in intent but also designed to be physically adaptable—such as through adjustable sculpture mounts—thereby addressing the diversity of bodily abilities and ergonomic requirements.

Institutional transformation was also supported by consistent investment in staff training and the creation of dedicated accessibility roles. Programmes such as Onda Educa’s modular training enabled museum professionals to develop competencies in non-visual communication, inclusive facilitation, and adaptive tour design. The appointment of accessibility coordinators ensured accountability and continuity in implementing these practices. Notably, the museum embedded accessibility into its operational identity by establishing continuous feedback mechanisms, including visitor evaluations, advisory panels, and structured observation protocols. This iterative, data-informed model reinforced the idea that accessibility is not a finite project, but an evolving institutional commitment requiring structural support and dedicated funding.

At the level of cultural policy, several implications arise from the Entre Luces case. First, there is a pressing need to strengthen regulatory frameworks that promote participatory accessibility in accordance with international instruments such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Articles 9 and 30) and the European Disability Rights Strategy 2021–2030. National legislation should not only mandate accessibility but also encourage it through incentive structures such as funding schemes or certification programmes like the AENOR Universal Accessibility standard.

Secondly, targeted support should be provided to small and medium-sized museums, particularly those located in heritage buildings, where the tension between conservation and inclusion is most acute. Public funding, technical assistance, and adaptive design guidelines are essential to help these institutions implement inclusive practices without compromising their architectural integrity. The Entre Luces project serves as a replicable model that can guide similar efforts across Europe.

Cross-sector collaboration also emerged as a crucial enabler of success. The partnership between the museum, vocational training institutions, disability organisations, and local authorities demonstrates how pooling resources and expertise can generate innovative, socially embedded solutions. Cultural policy should facilitate and institutionalise such collaboration through dedicated platforms, funding calls, and brokerage mechanisms. Moreover, national and European databases could be established to promote knowledge exchange and the scaling of best practices in inclusive heritage design.

Evaluation practices should also evolve to better reflect the goals of accessibility and inclusion. Instead of relying solely on quantitative indicators such as visitor numbers, institutions should adopt qualitative metrics that capture the depth of engagement, diversity of participation, and transformative impact of inclusive strategies. Public museums, in particular, should be required to report regularly on accessibility outcomes, using standard but adaptable assessment tools to benchmark progress and inform decision-making.

Finally, the sustainability of inclusive practices relies on continued investment in research and innovation. Longitudinal studies are required to assess the long-term effects of inclusive design on social cohesion, cultural participation, and institutional change. Simultaneously, pilot projects involving emerging technologies—such as AI-driven voice modulation, haptic feedback interfaces, and dynamic routing systems—should be supported to explore new frontiers in sensory and cognitive accessibility.

The Entre Luces project demonstrates that accessibility, when treated as a cultural and institutional responsibility rather than a technical add-on, can act as a catalyst for systemic transformation. By integrating co-creation, sensory innovation, and structural adaptation into the core of museum practice, and by aligning policy frameworks to support such initiatives, cultural equity can be pursued not merely as an aspiration, but as a sustainable and embedded reality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.S. and J.M.; methodology, A.S.; investigation, J.M.; resources, R.C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, A.S., J.M., R.C.V., G.O.; supervision, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by H2020-EU.1.3.—EXCELLENT SCIENCE—Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action RISE project, entitled “Informal and Non-Formal E-Learning for Cultural Heritage—xFORMAL” (Grant number n. 101008184).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to all the people who generously offered their time and thoughts during the interviews conducted as part of the Entre Luces project. In particular, we would like to thank the representatives of the Museo Pablo Gargallo and ONCE. Their testimonies provided an essential contribution to the understanding of the processes, challenges and results of the project, enriching the reflection on the social role of the museum and accessibility as a transformative process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iodice, G.; Carignani, F.; Clemente, L.; Bifulco, F. Museum accessibility: A managerial perspective on digital approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), Milano, Italy, 25–27 October 2023; pp. 1144–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Delfa-Lobato, L.; Feliu-Torruella, M.; Granell-Querol, A.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J. The Role of Cultural Institutions in Promoting Well-Being, Inclusion, and Equity among People with Cognitive Impairment: A Case Study of La Pedrera—Casa Milà and the Railway Museum of Catalonia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, N.N. Unveiling hidden histories: Disability in Ancient Egypt and its impact on today’s society—How can disability representation in museums challenge societal prejudice? Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiuseppe, M.; Span, S.; Bortolotti, E. Improving accessibility to cultural heritage for people with Intellectual Disabilities: A tool for observing the obstacles and facilitators for the access to knowledge. Alter 2021, 15, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Gil, T. Caminando hacia la construcción de una museología inclusiva: Percepción del público juvenil sobre inclusión cultural en espacios museísticos. Investig. En. La. Esc. 2020, 101, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, L.; Paananen, S.; Lengyel, D.; Häkkilä, J.; Toubekis, G.; Talhouk, R.; Hespanhol, L. Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) Advances to Re-Contextualize Cultural Heritage toward Multiperspectivity, Inclusion, and Sensemaking. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, G.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Gijlers, H.; Tonolli, L. Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence for Designing Accessible Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamazares de Prado, J.E.; Arias Gago, A.R. Technology and education as elements in museum cultural inclusion. Educ. Urban Soc. 2023, 55, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Carrizosa, H.; Sheehy, K.; Rix, J.; Seale, J. Designing technologies for museums: Accessibility and participation issues. J. Enabling Technol. 2021, 14, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Porter, J.E.; Barbagallo, M.S. Simplifying qualitative case study research methodology: A step-by-step guide using a palliative care example. Qual. Rep. 2023, 28, 2363–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H. Using Triangulation and Crystallization to Make Qualitative Studies Trustworthy and Rigorous. Qual. Rep. 2024, 29, 1844–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Johnson, C.W. Contextualizing reliability and validity in qualitative research: Toward more rigorous and trustworthy qualitative social science in leisure research. J. Leis. Res. 2020, 51, 432–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, M.A. Triangulation and Trustworthiness—Advancing Research on Public Service Interpreting through Qualitative Case Study Methodologies. Res. Methods Public Serv. Interpret. Transl. 2020, 7, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, A.; Ferri, D. Barriers and facilitators to cultural participation by people with disabilities: A narrative literature review. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2022, 24, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidiac, S.E.; Reda, M.A. “True” accessibility barriers of heritage buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, E.; Cerdán Chiscano, M. Heritage sites experience design with special needs customers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 4211–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Herrera, A.I.; Díaz-Herrera, A.B.; Hernández-Dionis, P.; Pérez-Jorge, D. Educational and accessible museums and cultural spaces. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moolhuijsen, N. Questioning Participation and Display Practices in Fine Arts Museums. ICOFOM Study Ser. 2015, 43a, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citarella, A.; Sánchez Iglesias, A.I.; González Ballester, S.; Maldonado Briegas, J.J.; Vicente Castro, F.; González Bernal, J. Being disabled persons in Spain: Policies, stakeholders and services. Rev. INFAD Psicología. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 1, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Robles, T. Discapacidad y Universidad española: Protección del estudiante universitario en situación de discapacidad. Rev. Derecho Del. Estado 2016, 36, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandell, R. Museums as agents of social inclusion. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1998, 17, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenwyder, B.; Buchmüller, E.; Trachsel, C.; Opwis, K.; Brühlmann, F. My Train Talks to Me: Participatory Design of a Mobile App for Travellers with Visual Impairments. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; ICCHP 2020, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Miesenberger, K., Manduchi, R., Covarrubias Rodriguez, M., Peňáz, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12376. [Google Scholar]

- Mieczakowski, A.; Hessey, S.; Clarkson, P.J. Inclusive Design and the Bottom Line: How Can Its Value Be Proven to Decision Makers? In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Design Methods, Tools, and Interaction Techniques for eInclusion; UAHCI 2013, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8009. [Google Scholar]

- Zoon, H.M.; Cremers, A.H.M.; Eggen, J.H. “Include”, a Toolbox of User Research for Inclusive Design. In Proceedings of the Chi Sparks 2014, The Hague, The Netherlands, 3 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdán Chiscano, M.; Jiménez-Zarco, A.I. Towards an inclusive museum management strategy: An exploratory study of consumption experience in visitors with disabilities. The case of the CosmoCaixa Science Museum. Sustainability 2021, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginley, B. Museums: A Whole New World for Visually Impaired People. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2013, 33, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos Quero, L.; Iranzo Bartolomé, J.; Cho, J. Accessible Visual Artworks for Blind and Visually Impaired People: Comparing a Multimodal Approach with Tactile Graphics. Electronics 2021, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaduman, H.; Alan, Ü.; Yiğit, Ö.E. Beyond “do not touch”: The experience of a three-dimensional printed artifacts museum as an alternative to traditional museums for visitors who are blind and partially sighted. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2022, 21, 1055–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).