Giant Choroidal Nevus—A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Patient History

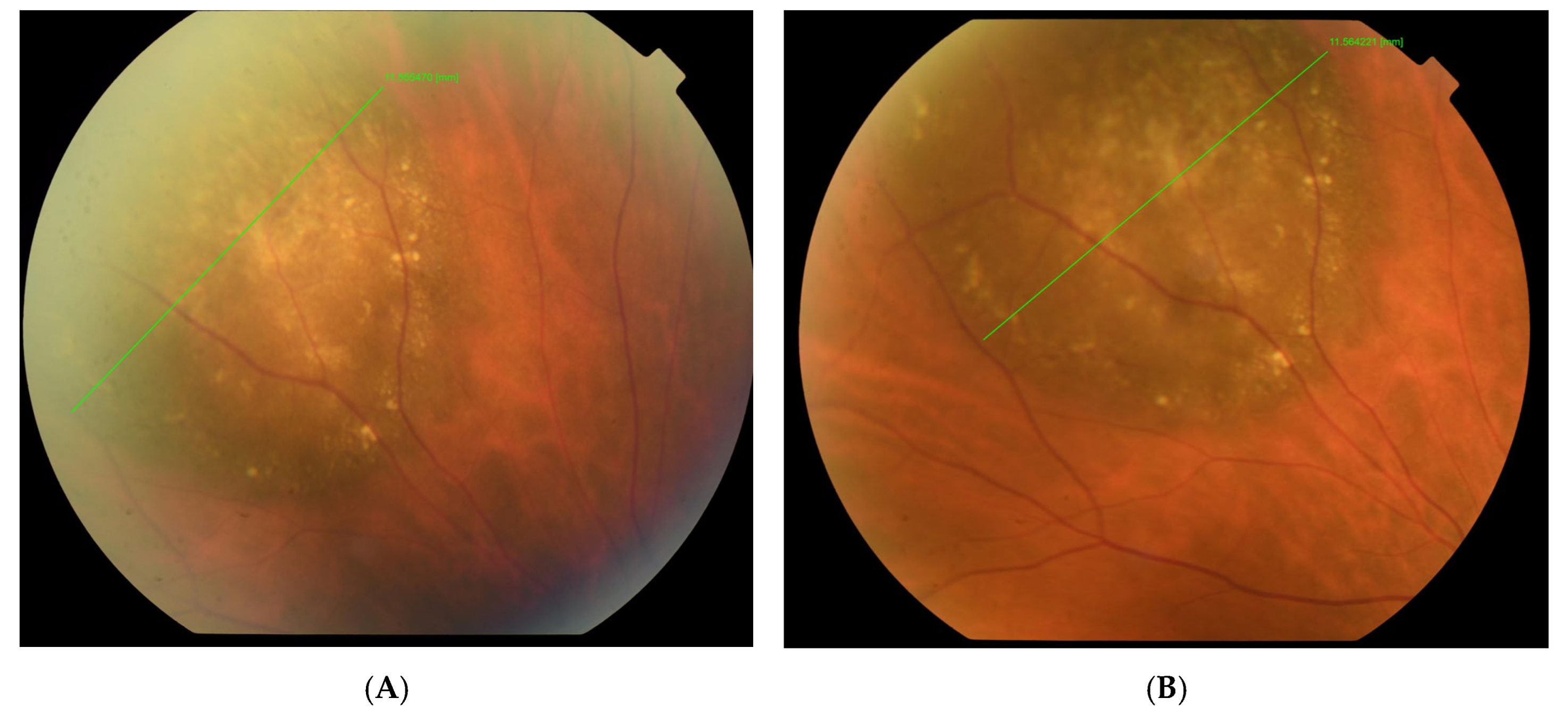

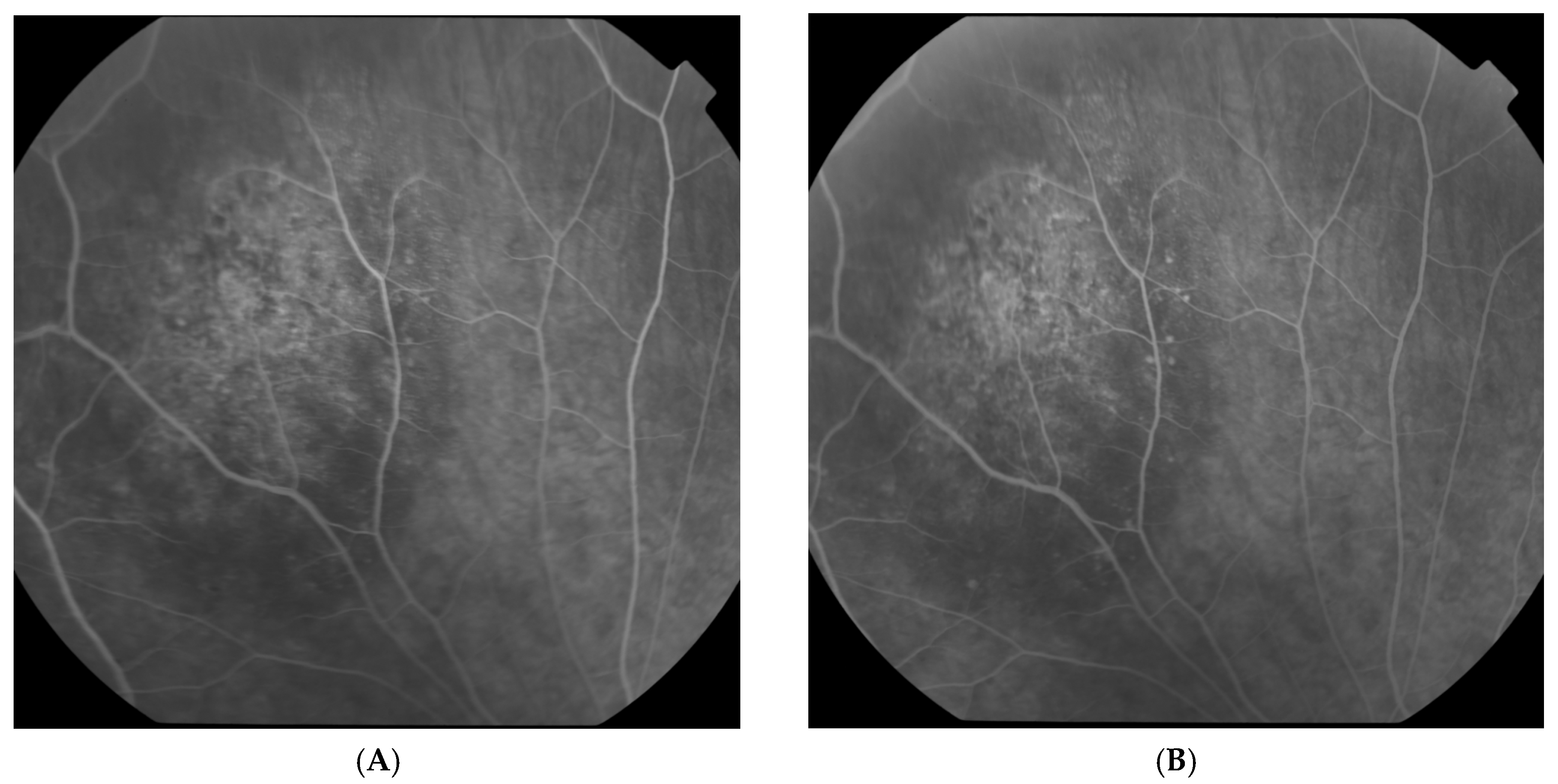

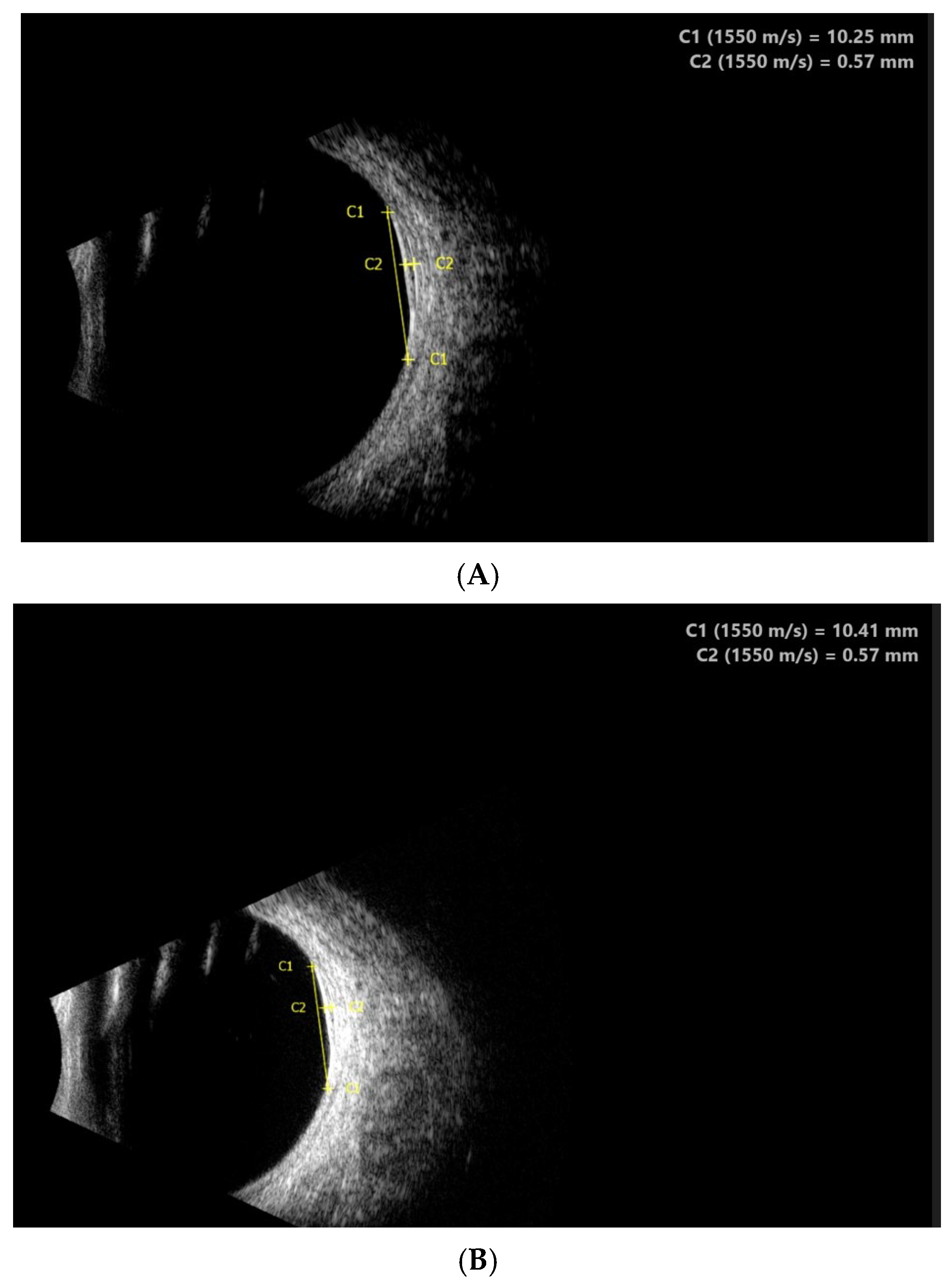

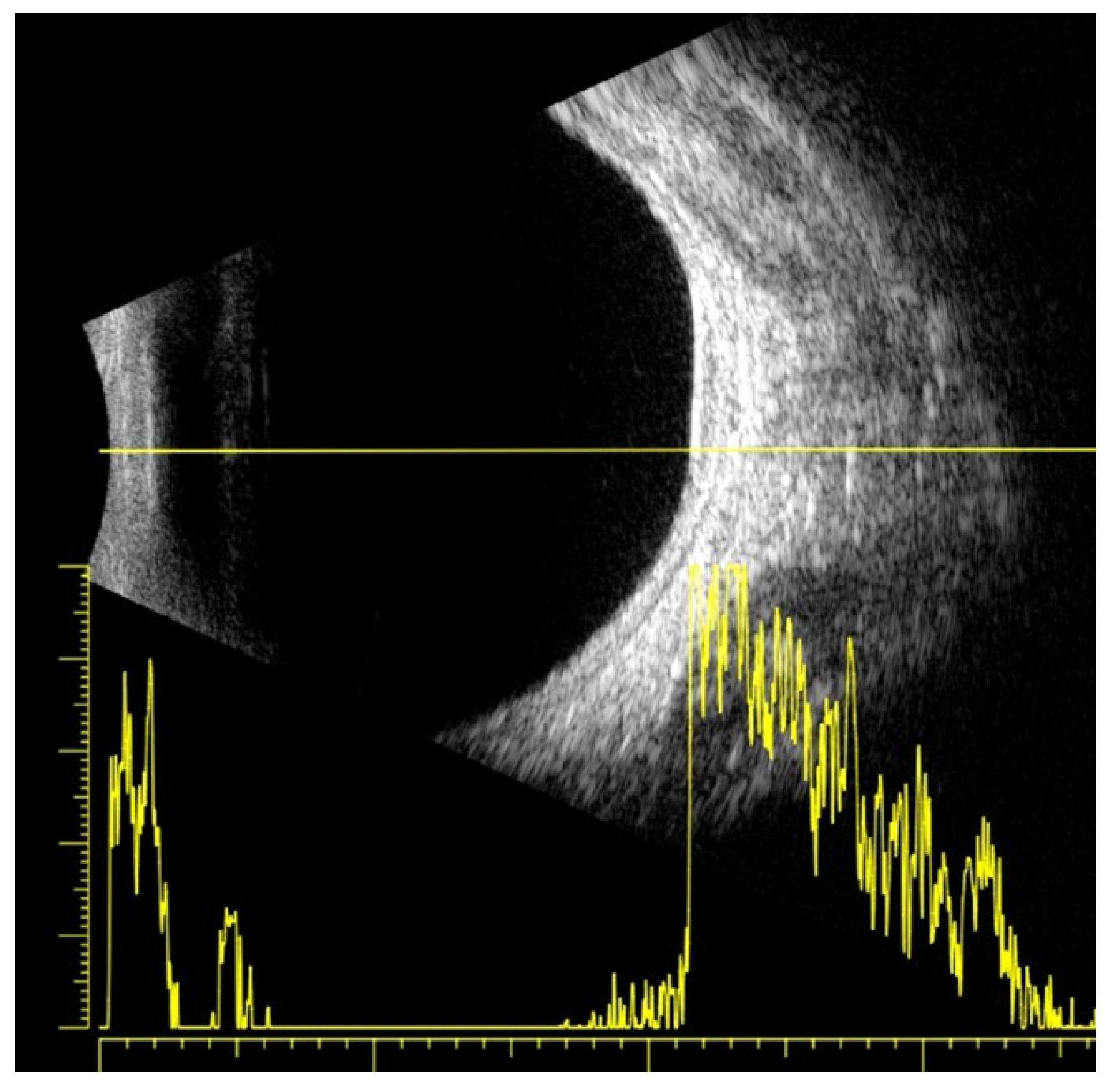

2.2. Clinical Findings

2.3. Diagnostic Assessment

2.4. Therapeutic Interventions

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Desjardins, L. Choroidal nevi. J. Fr. Ophthalmol. 2010, 33, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Shields, C.L. Choroidal nevus in the United States adult population: Racial disparities and associated factors in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2071–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumich, P.; Mitchell, P.; Wang, J.J. Choroidal nevi in a white population: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1998, 116, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; You, Q.S.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.X. Choroidal nevi in adult Chinese. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1102–11102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.H.; Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P.; Islam, F.M.A.; Wong, T.Y. Prevalence and characteristics of choroidal nevi in an Asian vs. white population. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2009, 127, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenstein, M.B.; Myers, C.E.; Meuer, S.M.; Klein, B.E.; Cotch, M.F.; Wong, T.Y.; Klein, R. Prevalence and characteristics of choroidal nevi: The multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 2468–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangia, V.; Jonas, J.B.; Agarwal, S.; Khare, A.; Lambat, S.; Panda-Jonas, S. Choroidal nevi in adult Indians: The central India eye and medical study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 96, 1443–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Shields, C.L. Relationship between female reproductive factors and choroidal nevus in US women: Analysis of data from the 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth, R.M.; Qiu, M.; Shields, C.L. Sex differences in the relationship between obesity and choroidal nevus in US adults. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 7489–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shields, C.L.; Furuta, M.; Mashayekhi, A.; Berman, E.L.; Zahler, J.D.; Hoberman, D.M.; Dinh, D.H.; Shields, J.A. Clinical spectrum of choroidal nevi based on age at presentation in 3422 consecutive eyes. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.K.; Shields, C.L.; Mashayekhi, A.; Randolph, J.D.; Bailey, T.; Burnbaum, J.; Shields, J.A. Giant choroidal nevus clinical features and natural course in 322 cases. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyukhina, A.S. OCT classification of choroidal nevi. Vestn. Ophthalmol. 2023, 139, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, J.L.; Sioufi, K.; Surakiatchanukul, T.; Shields, J.A.; Shields, C.L. Choroidal nevus: A review of prevalence, features, genetics, risks, and outcomes. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 28, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, C.L.; Cater, J.; Shields, J.A.; Singh, A.D.; Santos, M.C.M.; Carvalho, C. Combination of clinical factors predictive of growth of small choroidal melanocytic tumor. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.L.; Furuta, M.; Mashayekhi, A.; Berman, E.L.; Zahler, J.D.; Hoberman, D.M.; Dinh, D.H.; Shields, J.A. Visual acuity in 3422 consecutive eyes with choroidal nevus. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2007, 125, 1501–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamler, E.; Maumenee, A.E. A clinical study of choroidal nevi. AMA Arch. Ophthalmol. 1959, 62, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flindall, R.J.; Drance, S.M. Visual field studies of benign choroidal melanomata. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1969, 81, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.W.; Correa, Z.M.; Say, E.A.; Borges, F.P.; Siqueira, R.C.; Cardillo, J.A.; Jorge, R. Photoreceptor arrangement changes secondary to choroidal nevus. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besada, E.; Shechtman, D.; Barr, R.D. Melanocytoma inducing compressive optic neuropathy: The ocular morbidity potential of an otherwise invariably benign lesion. Optometry 2002, 73, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Diener-West, M.; Hawkins, B.S.; Markowitz, J.A.; Schachat, A.P. A review of mortality from choroidal melanoma. II. A meta-analysis of 5-year mortality rates following enucleation, 1966 through 1988. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1992, 110, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.L.; Shields, J.A.; Kiratli, H.; De Potter, P.; Cater, J.R. Risk factors for growth and metastasis of small choroidal melanocytic lesions. Ophthalmology 1995, 102, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shields, J.A. Treating some small melanocytic choroidal lesions without waiting for growth. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2006, 124, 1344–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoyanova, N.S.; Atanassov, M.; Mitkova-Hristova, V.T.; Basheva-Kraeva, Y.; Kraeva, M. Giant Choroidal Nevus—A Case Report. Reports 2025, 8, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020041

Stoyanova NS, Atanassov M, Mitkova-Hristova VT, Basheva-Kraeva Y, Kraeva M. Giant Choroidal Nevus—A Case Report. Reports. 2025; 8(2):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020041

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoyanova, Nina Staneva, Marin Atanassov, Vesela Todorova Mitkova-Hristova, Yordanka Basheva-Kraeva, and Maria Kraeva. 2025. "Giant Choroidal Nevus—A Case Report" Reports 8, no. 2: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020041

APA StyleStoyanova, N. S., Atanassov, M., Mitkova-Hristova, V. T., Basheva-Kraeva, Y., & Kraeva, M. (2025). Giant Choroidal Nevus—A Case Report. Reports, 8(2), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020041