Visual Navigation Using Depth Estimation Based on Hybrid Deep Learning in Sparsely Connected Path Networks for Robustness and Low Complexity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Robot Navigation Methods Based on VT&R

2.2. Depth Estimation Methods

2.2.1. Depth Estimation Methods Based on RGB Images

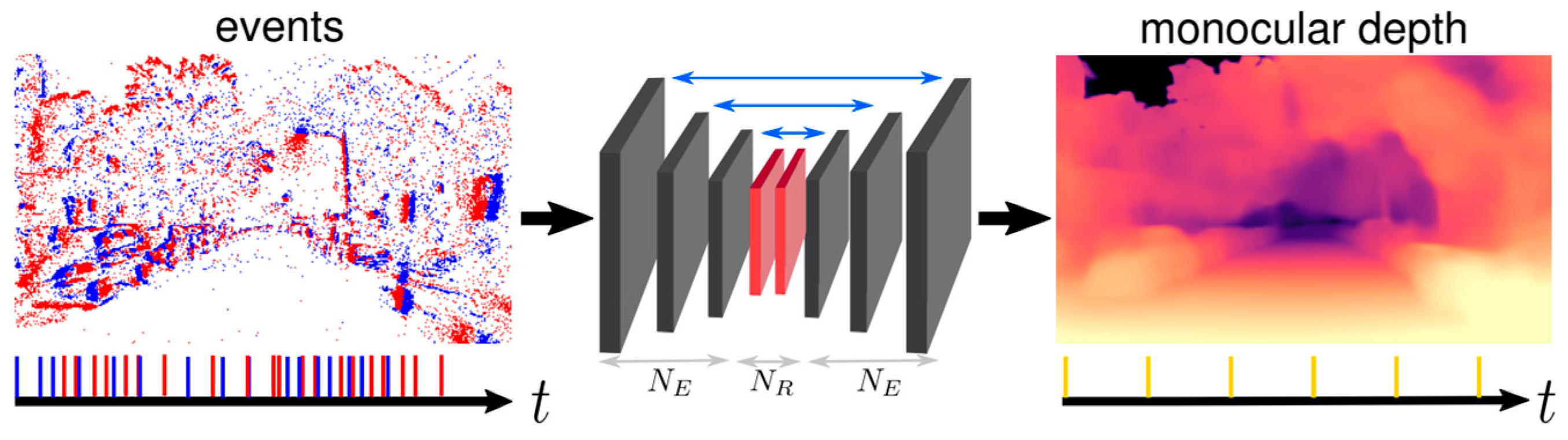

2.2.2. Depth Estimation Methods Based on Event Images

3. Proposed Method

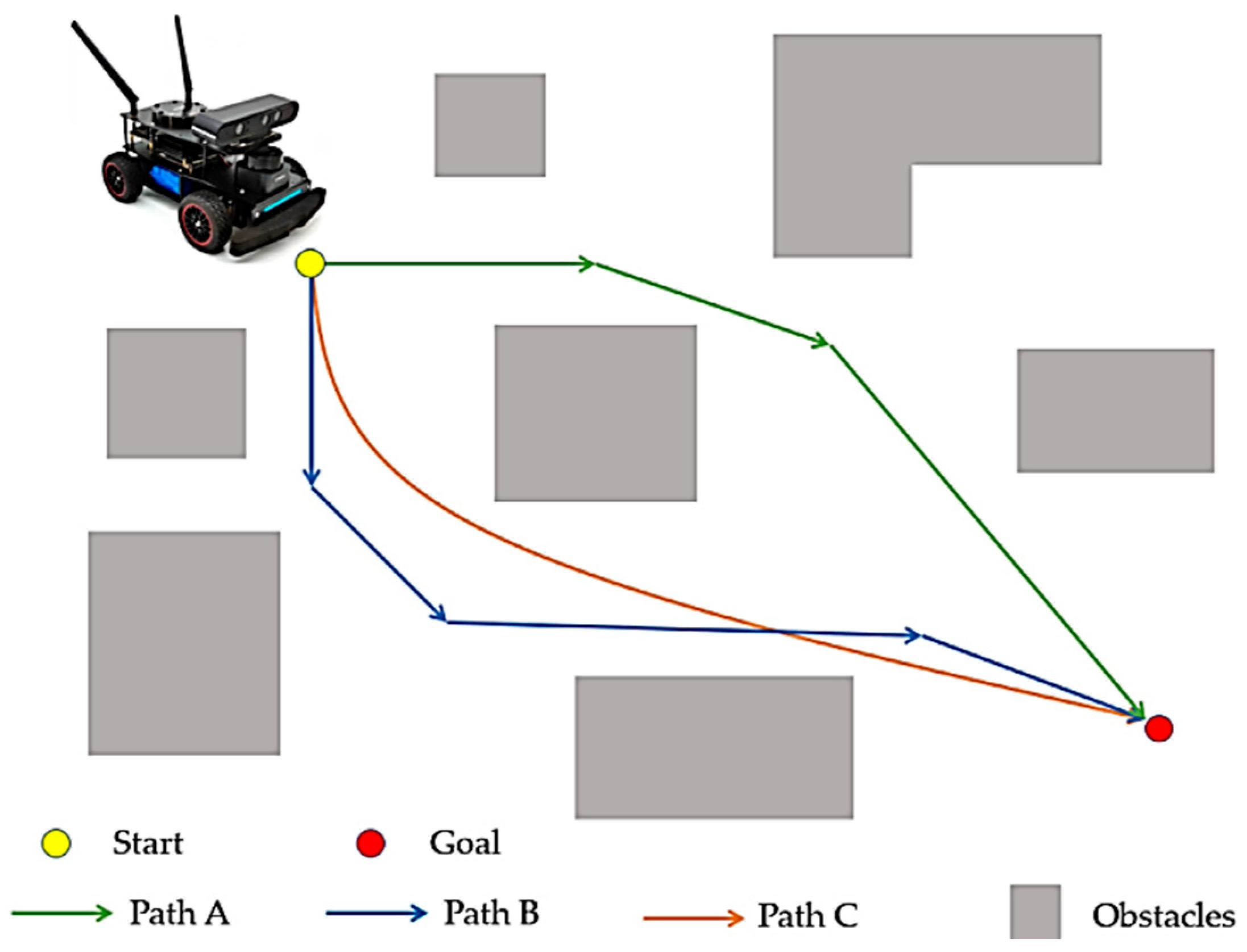

3.1. Definition of the Problem

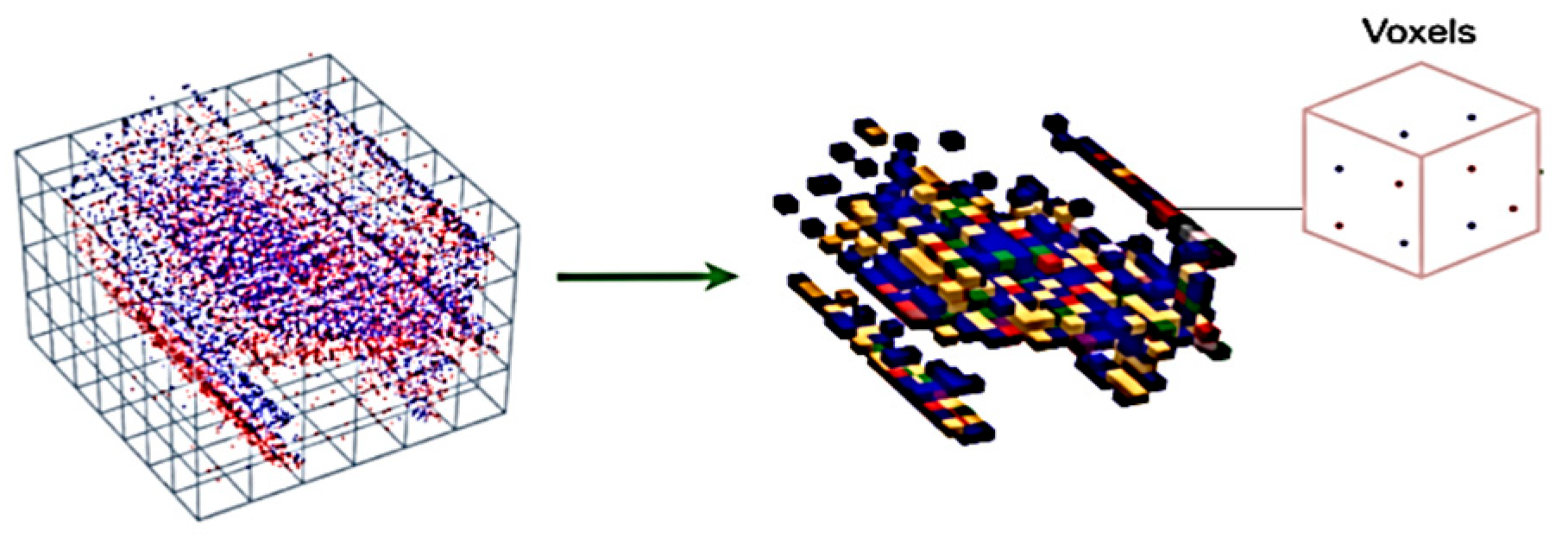

3.2. Event Stream

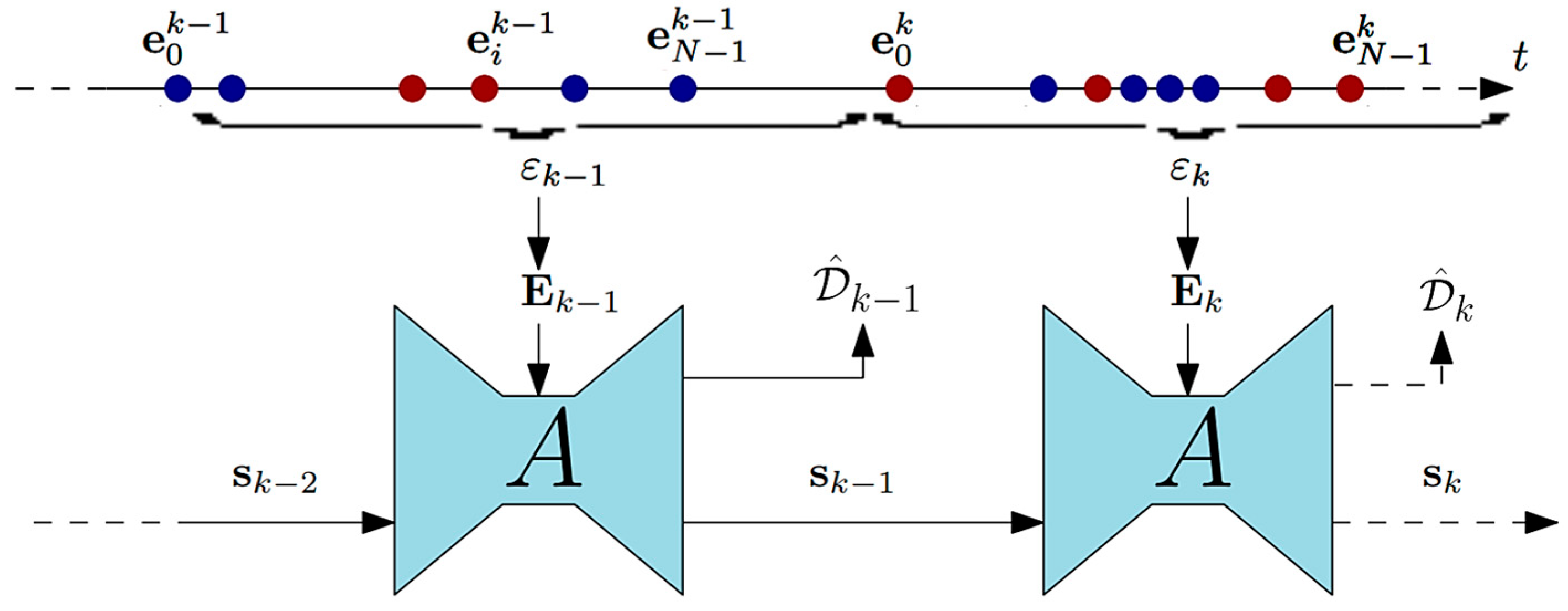

3.3. Deep Network 1 (UNET)

3.4. Routing Based on VT&R Method

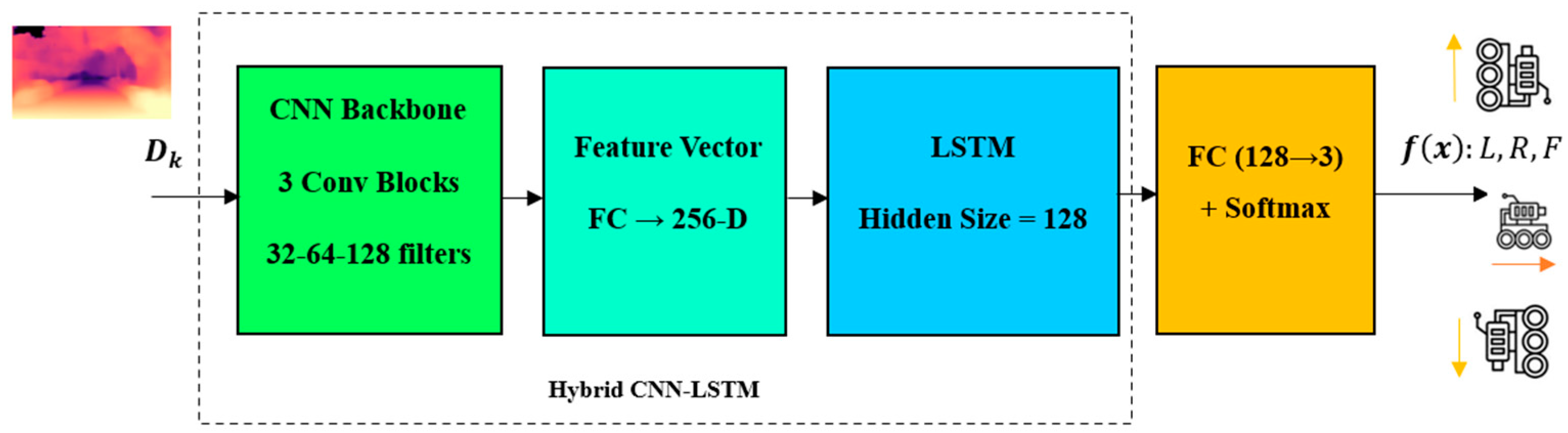

3.5. Deep Network 2 (Hybrid CNN-LSTM)

- Input data: The network receives a sequence of estimated depth images as input. Let us assume the input sequence has a length of T, and each depth image is denoted by ;

- CNN Backbone: The initial step involves passing each depth image through a CNN backbone to extract meaningful features. This process is denoted by CNN(), yielding the feature map for the depth image;

- Feature Encoding: The feature maps derived from the CNN backbone need to be encoded into a representation with fixed dimensions. This encoding facilitates the retention of timing information across the sequence. A commonly employed method for this task is to utilize an LSTM network.

- LSTM input: The input to the LSTM at time t is denoted as and can be computed as follows:

- LSTM hidden state update: The LSTM retains a hidden state , capturing temporal dependencies within input sequences. The hidden state at time , denoted by , can be updated utilizing the input and the previous hidden state as follows:

- LSTM output: The LSTM output at time , denoted by , represents the encoded representation of the feature map at that specific time step.

- VT&R Algorithm: The encoded representations obtained from the LSTM can now be employed within the VT&R algorithm for robot navigation. The features of this algorithm are contingent upon the particular approach utilized.

- VT&R Loss: In the VT&R algorithm, the usual procedure entails comparing the robot’s current observations with previously observed sequences. The loss for VT&R can be defined based on the coded representations and the desired target sequence:

- Training: The entire network, comprising the CNN, LSTM, and VT&R modules, can undergo end-to-end training. Network parameters can be updated utilizing gradient-based optimization techniques, such as backpropagation.

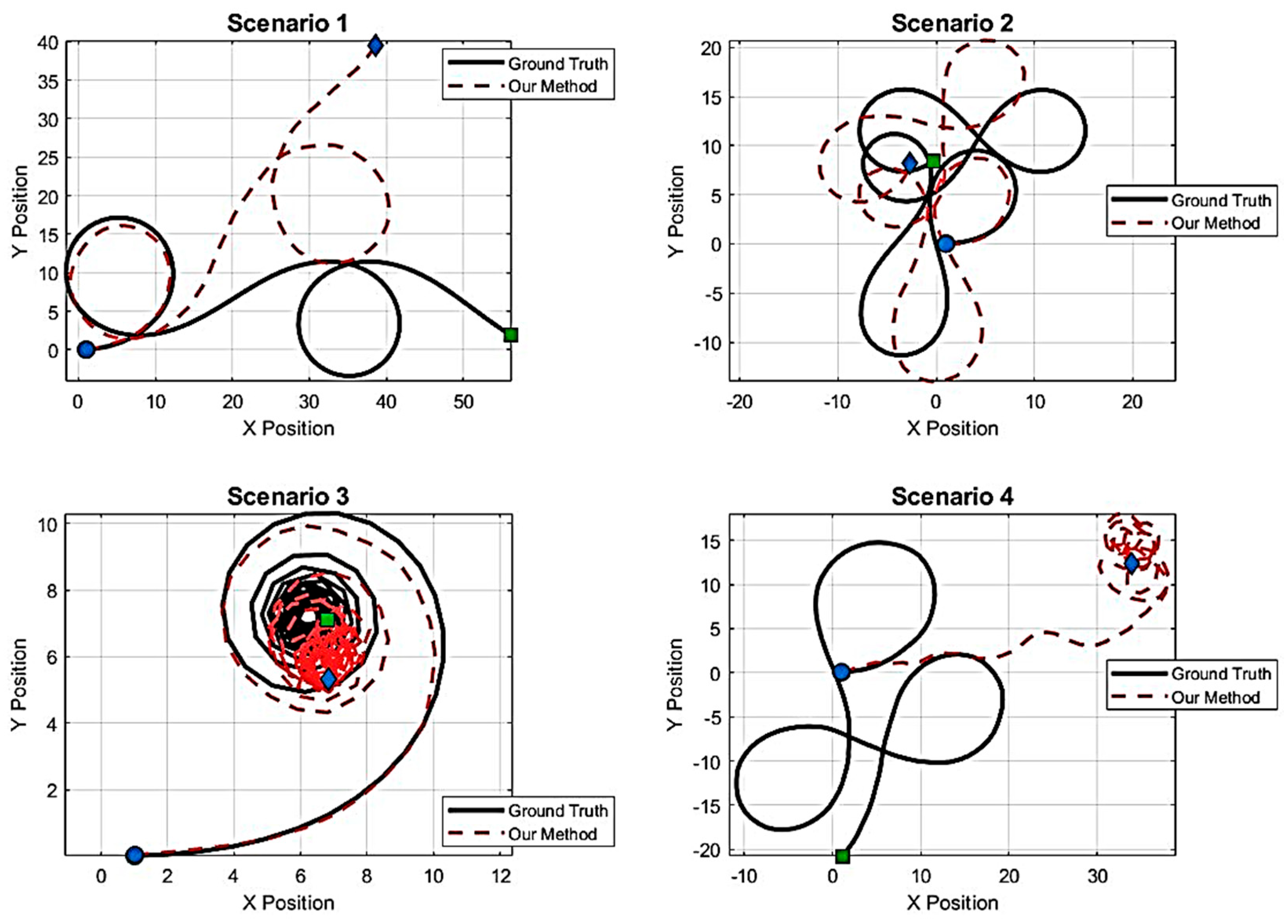

4. Simulation of the Proposed Method

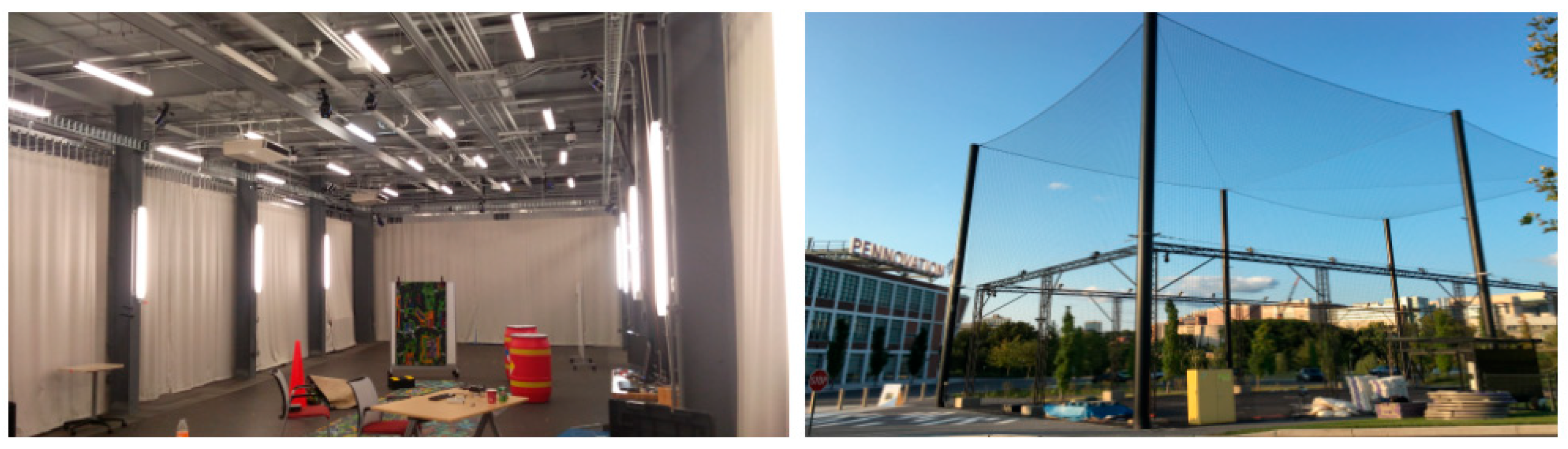

4.1. Simulation Dataset

- The MVSEC dataset comprises two sets of features: Indoor Vicon and Outdoor Qualisys;

- Indoor Vicon:

- -

- The Indoor Vicon setup covers a space measuring 88 × 22 × 15 ft, enabling the tracking system to capture movements within this area;

- -

- It employs 20 Vicon Vantage VP-16 cameras to track the movement of objects or individuals within the designated area;

- -

- The dataset offers pose updates at a frequency of 100 Hz, indicating that the position and orientation of objects are recorded 100 times per second;

- Outdoor Qualisys:

- -

- The outdoor setup of the Qualisys system covers a larger area, which is 100 × 50 × 50 ft. This allows for tracking movements in a more extensive outdoor environment;

- -

- It deploys 34 Qualisys Opus 700 cameras to capture the movements and positions of objects in the designated outdoor area;

- -

- Like the Indoor Vicon system, the Outdoor Qualisys system provides pose updates at a frequency of 100 Hz, meaning that the position and orientation of objects are recorded 100 times per second.

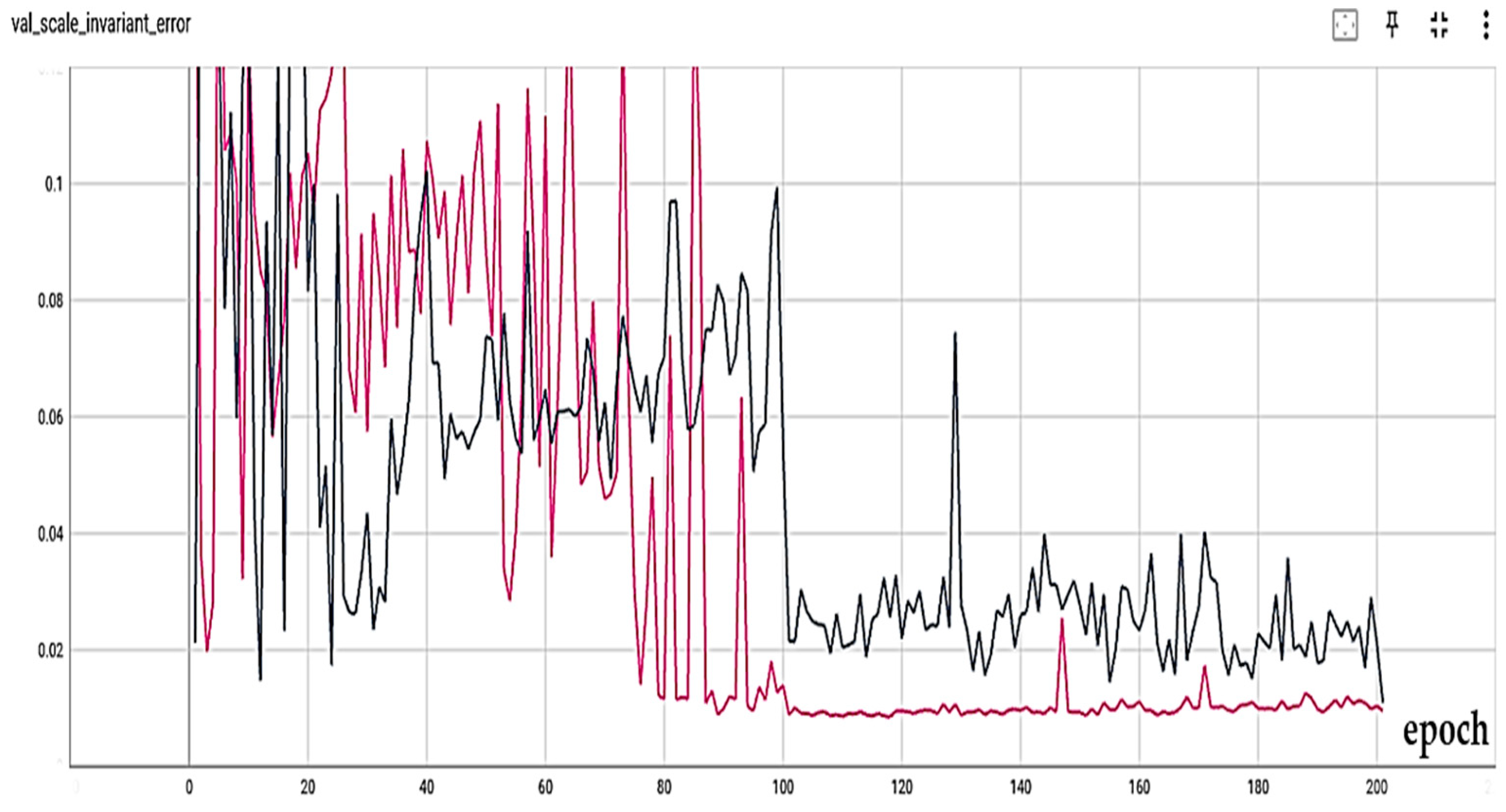

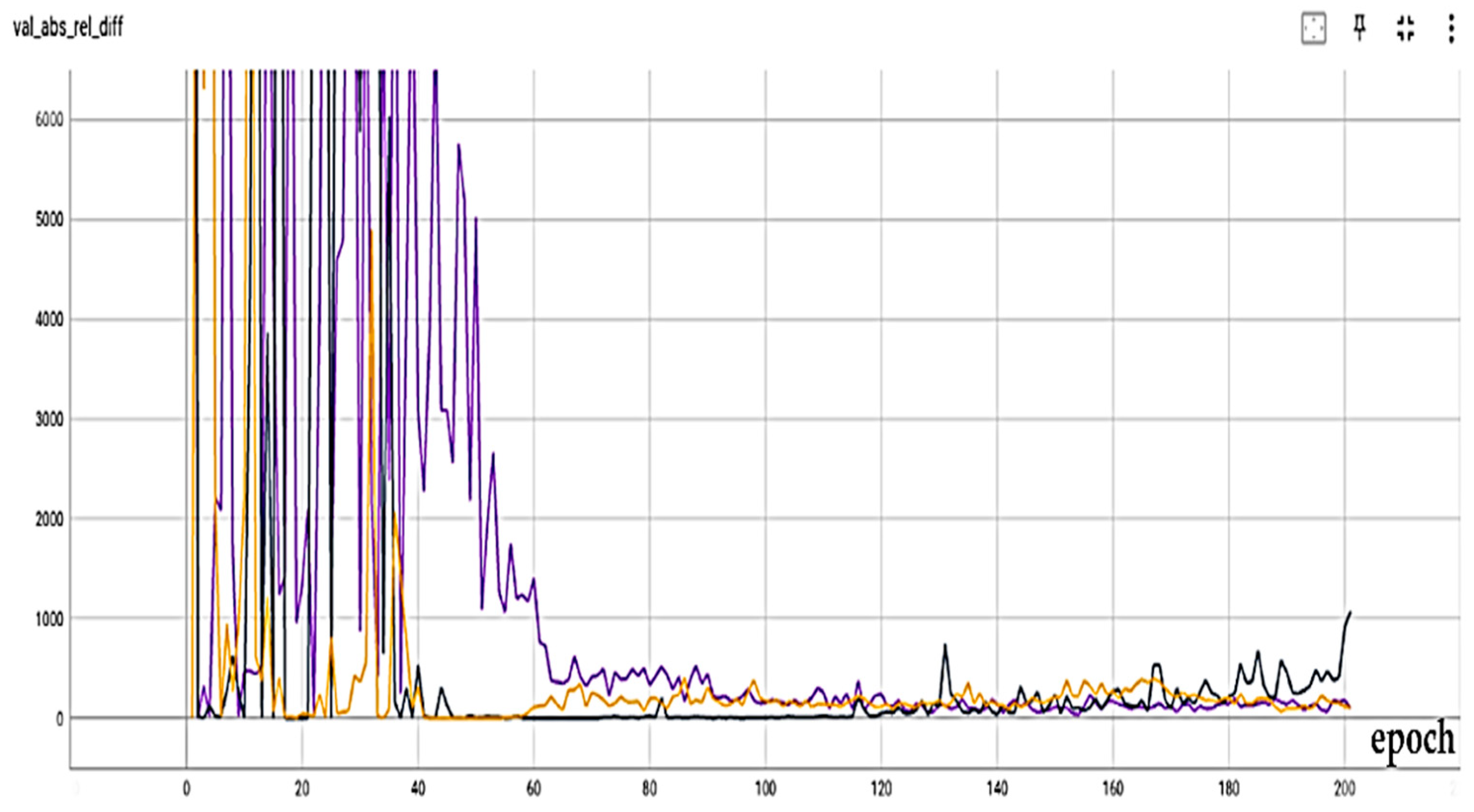

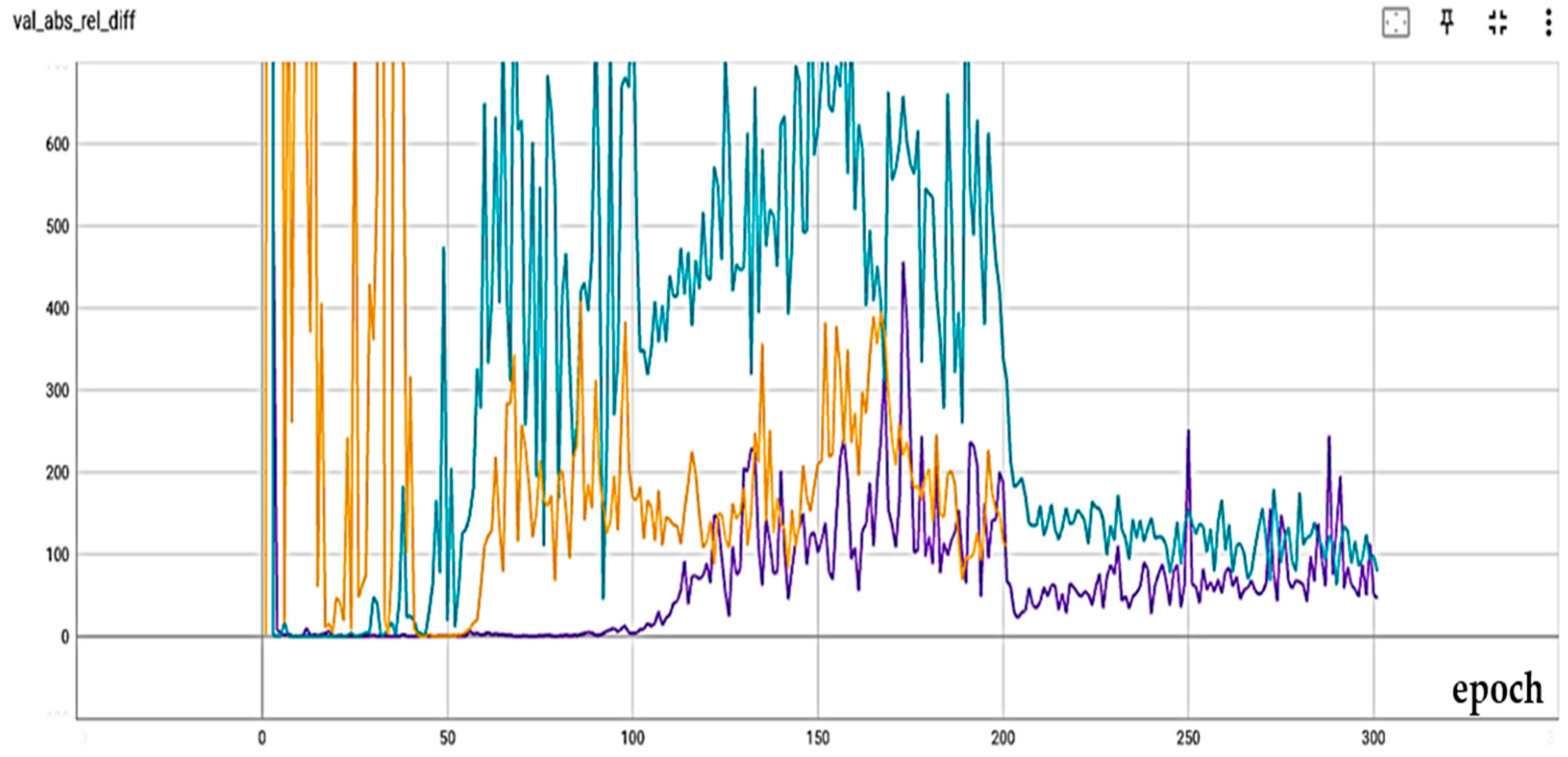

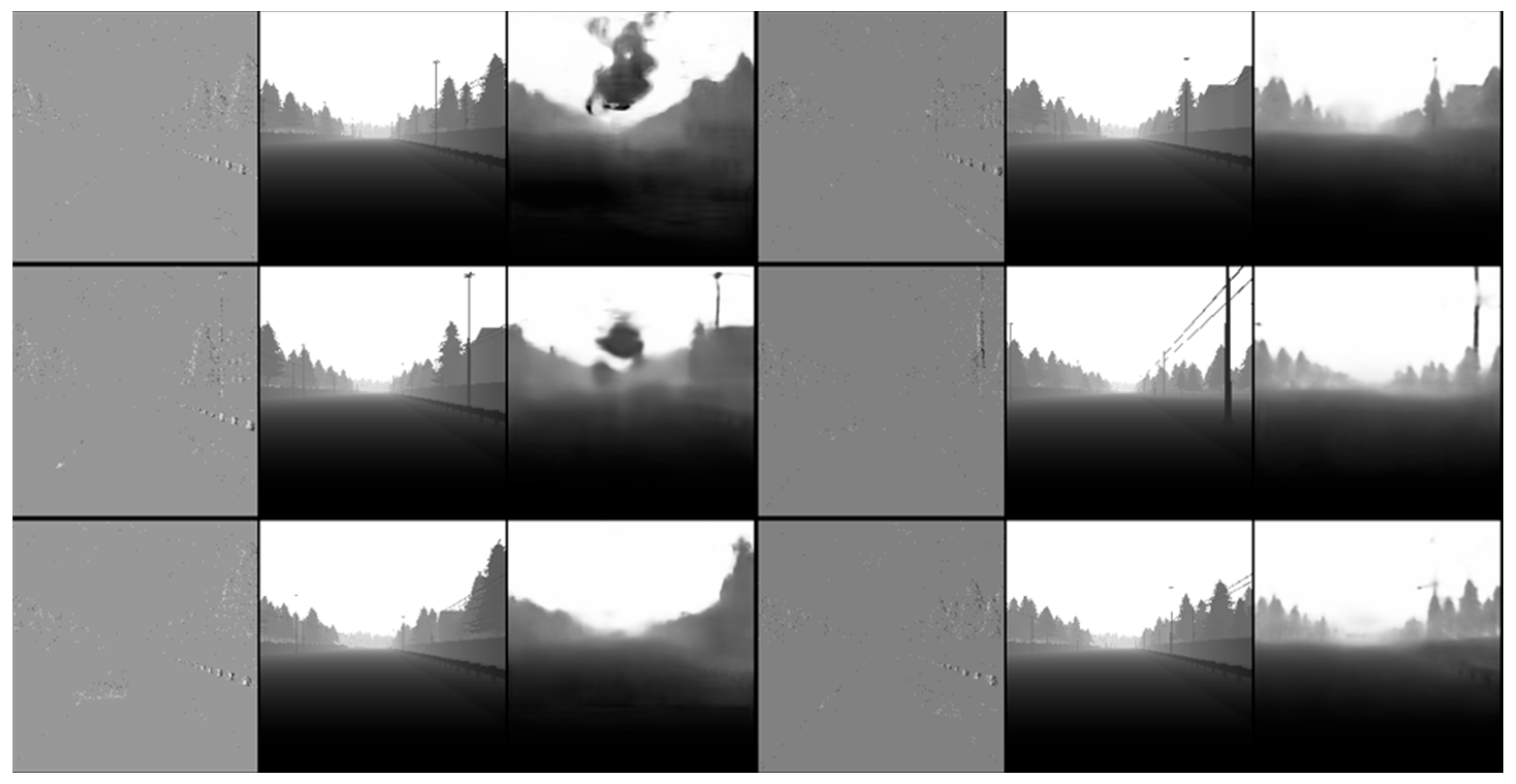

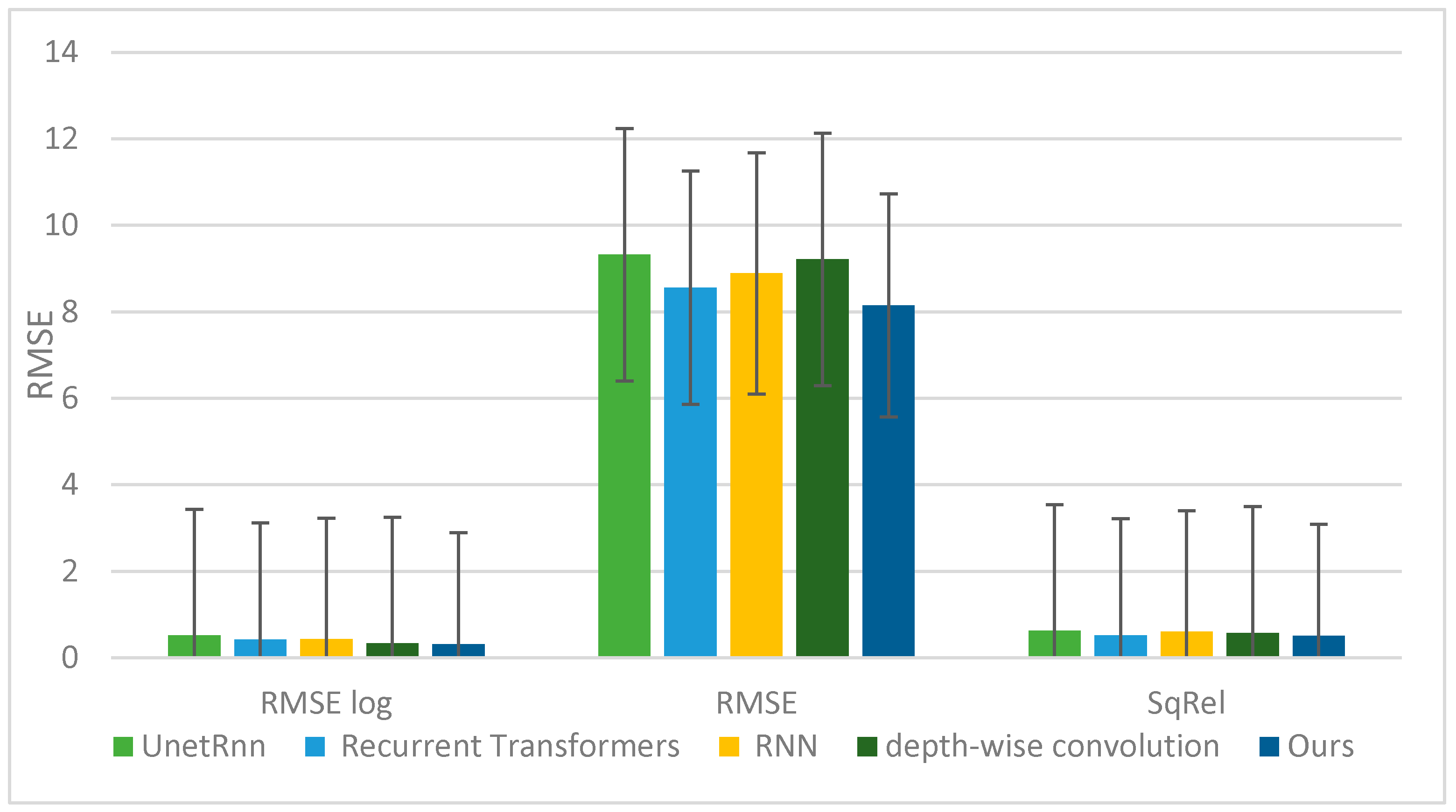

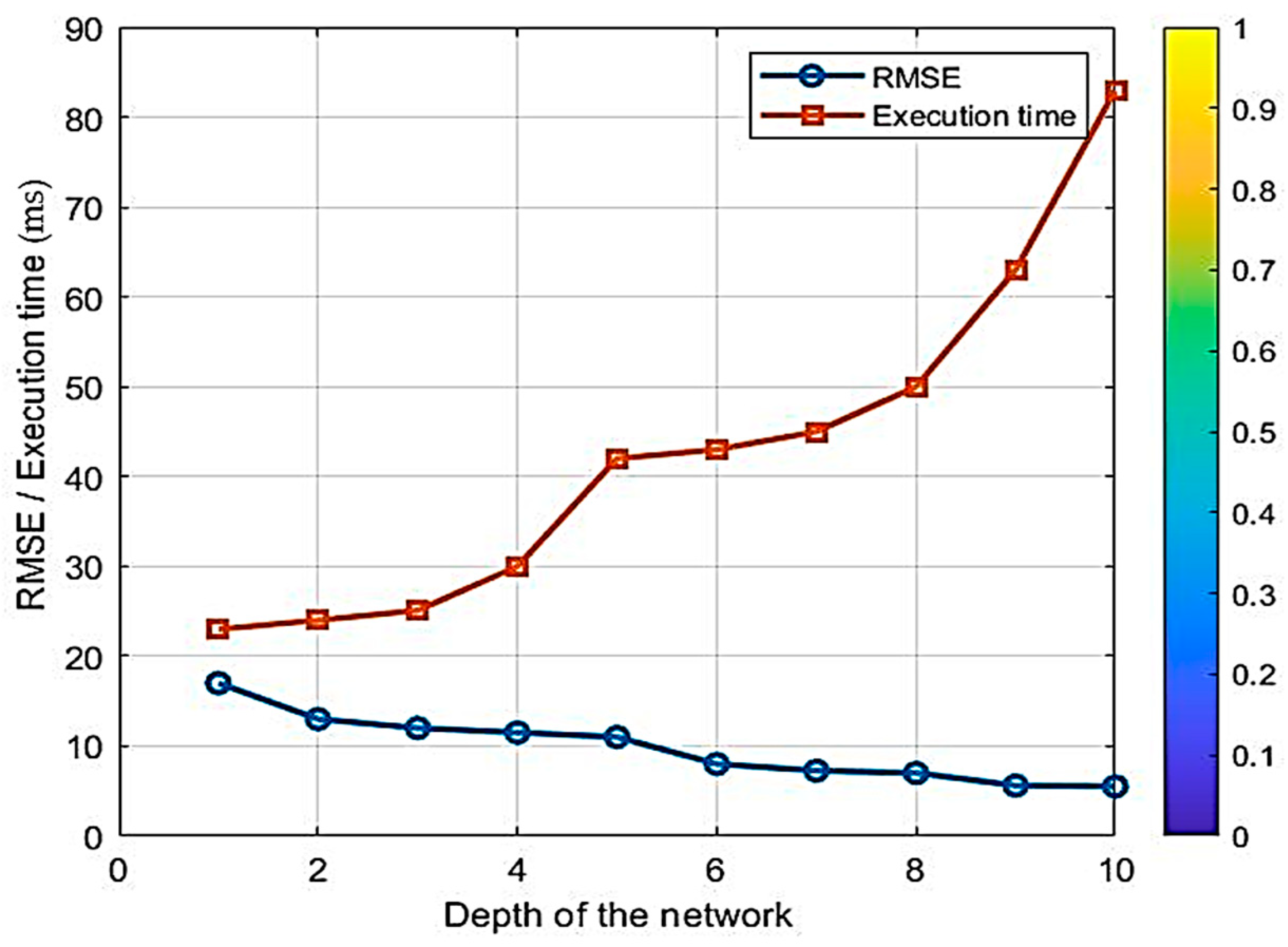

4.2. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, Y.; Zakaria, M.A.; Younas, M. Path planning trends for autonomous mobile robot navigation: A review. Sensors 2025, 25, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Chowdhury, C. A survey of machine learning techniques for indoor localization and navigation systems. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 101, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y.D.; Martins, L.E.G.; Cappabianco, F.A. Autonomous visual navigation for mobile robots: A systematic literature review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, S.; Huang, J.; Cheng, H. NaviDiffusor: Cost-Guided Diffusion Model for Visual Navigation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.10003. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Wahab, M.N.; Nefti-Meziani, S.; Atyabi, A. A comparative review on mobile robot path planning: Classical or meta-heuristic methods? Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluvia, I.; Lazkano, E.; Ansuategi, A. Active mapping and robot exploration: A survey. Sensors 2021, 21, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waga, A.; Benhlima, S.; Bekri, A.; Abdouni, J. A novel approach for end-to-end navigation for real mobile robots using a deep hybrid model. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2025, 18, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandi, S.; Alizadehsani, R.; Nahavandi, D.; Mohamed, S.; Mohajer, N.; Rokonuzzaman, M.; Hossain, I. A comprehensive review on autonomous navigation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lu, J.; Shi, Z. Research on path planning of mobile robot based on improved theta* algorithm. Algorithms 2022, 15, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zghair, N.A.K.; Al-Araji, A.S. A one decade survey of autonomous mobile robot systems. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2021, 11, 4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Chen, W.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H. FLAF: Focal Line and Feature-Constrained Active View Planning for Visual Teach and Repeat. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–23 May 2025; pp. 5259–5265. [Google Scholar]

- Yarovoi, A.; Cho, Y.K. Review of simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) for construction robotics applications. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwitta, C.; Rains, G.C. The integration of GPS and visual navigation for autonomous navigation of an Ackerman steering mobile robot in cotton fields. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11, 1359887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raivi, A.M.; Moh, S. Vision-Based Navigation for Urban Air Mobility: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Smart Media and Applications (SMA 2023), Taichung, Taiwan, 13–16 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nourizadeh, P.; Milford, M.; Fischer, T. Teach and repeat navigation: A robust control approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 2909–2916. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavian, M.; Yin, K.; Chen, M. Robust visual teach and repeat for ugvs using 3d semantic maps. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 8590–8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N. Towards Long-Term Vision-Based Localization in Support of Monocular Visual Teach and Repeat; University of Toronto (Canada): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Taher, M.; Wild, C.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Majer, F.; Yan, Z.; Krajník, T.; Prescott, T.; Duckett, T. Robust and long-term monocular teach and repeat navigation using a single-experience map. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 2635–2642. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Gallego, G. Event-based stereo depth estimation: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 9130–9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patle, B.; Pandey, A.; Parhi, D.; Jagadeesh, A. A review: On path planning strategies for navigation of mobile robot. Def. Technol. 2019, 15, 582–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Ferrari, S. Information-driven sensor path planning by approximate cell decomposition. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B (Cybern.) 2009, 39, 672–689. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, L.; Kumar, S.; Patchaikani, P.K.; Nair, R.R.; Dutta, S. Intelligent Control of Robotic Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Tian, X.; Gao, M. An improved ant colony algorithm for robot path planning. Soft Comput. 2017, 21, 5829–5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustris, G.P.; Tzafestas, S.G. Switching fuzzy tracking control for mobile robots under curvature constraints. Control Eng. Pract. 2011, 19, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrinidis, S.; Zacharia, P. An ANFIS-based strategy for autonomous robot collision-free navigation in dynamic environments. Preprints.org 2024, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.-j. Mobile robot SLAM method based on multi-agent particle swarm optimized particle filter. J. China Univ. Posts Telecommun. 2014, 21, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Paniagua, A.; Vega-Rodríguez, M.A.; Ferruz, J.; Pavón, N. Solving the multi-objective path planning problem in mobile robotics with a firefly-based approach. Soft Comput. 2017, 21, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Tian, C.; Sun, B.; Luo, C. Complete coverage path planning of autonomous underwater vehicle based on GBNN algorithm. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2019, 94, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwubueze, O.E.; Ifeanyichukwu, E.I.; Chigozie, E.P. Improving the Control of Autonomous Navigation of a Robot with Artificial Neural Network for Optimum Performance. Eng. Sci. 2024, 9, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Ferdiansyah, J.; Ariessanti, H.D. Integrating artificial intelligence for autonomous navigation in robotics. Int. Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 3, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palossi, D.; Conti, F.; Benini, L. An open source and open hardware deep learning-powered visual navigation engine for autonomous nano-uavs. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS), Santorini, Greece, 29–31 May 2019; pp. 604–611. [Google Scholar]

- Symeonidis, C.; Kakaletsis, E.; Mademlis, I.; Nikolaidis, N.; Tefas, A.; Pitas, I. Vision-based UAV safe landing exploiting lightweight deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Image and Graphics Processing, Sanya, China, 1–3 January 2021; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, L.; Krajník, T.; Duckett, T.; Yan, Z. Monocular teach-and-repeat navigation using a deep steering network with scale estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 2613–2619. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish, T.; Raskar, R. Deep visual teach and repeat on path networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1533–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F.; Wang, C.; Ge, S.S. A survey on visual navigation for artificial agents with deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 135426–135442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Q.; Zheng, W.X.; Du, W.; Qian, F.; Kurths, J. Perception and navigation in autonomous systems in the era of learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 9604–9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Abbatematteo, B.; Hu, J.; Chandra, R.; Martín-Martín, R.; Stone, P. Deep reinforcement learning for robotics: A survey of real-world successes. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February –4 March 2025; pp. 28694–28698. [Google Scholar]

- Arnez, F.; Espinoza, H.; Radermacher, A.; Terrier, F. Improving robustness of deep neural networks for aerial navigation by incorporating input uncertainty. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security, York, UK, 8–10 September 2021; pp. 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowski, P.; Pascanu, R.; Viola, F.; Soyer, H.; Ballard, A.J.; Banino, A.; Denil, M.; Goroshin, R.; Sifre, L.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Learning to navigate in complex environments. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.03673. [Google Scholar]

- Kulhánek, J.; Derner, E.; Babuška, R. Visual navigation in real-world indoor environments using end-to-end deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4345–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambarde, P.; Dudhane, A.; Murala, S. Single image depth estimation using deep adversarial training. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 989–993. [Google Scholar]

- Truhlařík, V.; Pivoňka, T.; Kasarda, M.; Přeučil, L. Multi-Platform Teach-and-Repeat Navigation by Visual Place Recognition Based on Deep-Learned Local Features. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13090. [Google Scholar]

- Boxan, M.; Krawciw, A.; Barfoot, T.D.; Pomerleau, F. Toward teach and repeat across seasonal deep snow accumulation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.01339. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Lira, D.-C.; Córdova-Esparza, D.-M.; Terven, J.; Romero-González, J.-A.; Alvarez-Alvarado, J.M.; González-Barbosa, J.-J.; Ramírez-Pedraza, A. Recent Developments in Image-Based 3D Reconstruction Using Deep Learning: Methodologies and Applications. Electronics 2025, 14, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Tang, S.; Fu, H.; Li, P.; Wu, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Boosting RGB-D saliency detection by leveraging unlabeled RGB images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertan, A.; Duff, D.J.; Unal, G. Single image depth estimation: An overview. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 123, 103441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Carrió, J.; Gehrig, D.; Scaramuzza, D. Learning monocular dense depth from events. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Fukuoka, Japan, 25–28 November 2020; pp. 534–542. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A.Z.; Yuan, L.; Chaney, K.; Daniilidis, K. Unsupervised event-based learning of optical flow, depth, and egomotion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 989–997. [Google Scholar]

- Françani, A.O.; Maximo, M.R. Transformer-based model for monocular visual odometry: A video understanding approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13959–13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, Z.; Gao, N. Transformer-based monocular depth estimation with hybrid attention fusion and progressive regression. Neurocomputing 2025, 620, 129268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, M.; Aarents, W.; Gehrig, D.; Scaramuzza, D. Dsec: A stereo event camera dataset for driving scenarios. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4947–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, J.; Fan, X.; Tian, Y. Event-based monocular dense depth estimation with recurrent transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.02791. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Peng, J.; Qiu, J.; Ju, X.; Lo, F.P.W.; Lo, B. Even: An event-based framework for monocular depth estimation at adverse night conditions. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Koh Samui, Thailand, 4–9 December 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, C.; Gan, H. Trap attention: Monocular depth estimation with manual traps. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 5033–5043. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Huang, K. Dense depth-map estimation based on fusion of event camera and sparse LiDAR. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 7500111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozsypálek, Z.; Broughton, G.; Linder, P.; Rouček, T.; Blaha, J.; Mentzl, L.; Kusumam, K.; Krajník, T. Contrastive learning for image registration in visual teach and repeat navigation. Sensors 2022, 22, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, T.; Alj, Y. Offline Deep Model Predictive Control (MPC) for Visual Navigation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics, Computer Vision and Intelligent Systems, Rome, Italy, 25–27 February 2024; pp. 134–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fisker, D.; Krawciw, A.; Lilge, S.; Greeff, M.; Barfoot, T.D. UAV See, UGV Do: Aerial Imagery and Virtual Teach Enabling Zero-Shot Ground Vehicle Repeat. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.16912. [Google Scholar]

| Specifications | Depth Estimation Stage | Visual Navigation Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Input | Event stream | Depth Map |

| Output | Depth Map | Navigation of Robot |

| Model | UNET | CNN-LSTM |

| 5 | |

| NE | 3 |

| NR | 2 |

| Nb | 32 |

| L | 40 |

| Component of Hybrid Network | Specification |

|---|---|

| Input | , sequence length (T) |

| CNN Backbone (3 Convolutional Blocks) | Conv Layer 1: 3 × 3 kernel, 32 filters, BatchNorm, ReLU Conv Layer 2: 3 × 3 kernel, 64 filters, BatchNorm, ReLU Conv Layer 3: 3 × 3 kernel, 128 filters, BatchNorm, ReLU Output flattened to Feature Vector (FC → 256D) |

| LSTM | Input: 256D Feature Vector Hidden State: 128 Captures temporal dependencies between frames Output: Encoded feature representation () |

| Fully Connected + Softmax | FC Layer: 128 → 3 Softmax activation for navigation command selection |

| Loss Function | Categorical Cross-Entropy–Spatio-temporal difference |

| Training | End-to-end training with backpropagation (30–70%) |

| Output Classes | 3 classes: Left, Right, Forward |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Institute of Knowledge Innovation and Invention. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al-Saedi, H.; Salehpour, P.; Aghdasi, S.H. Visual Navigation Using Depth Estimation Based on Hybrid Deep Learning in Sparsely Connected Path Networks for Robustness and Low Complexity. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2026, 9, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi9020029

Al-Saedi H, Salehpour P, Aghdasi SH. Visual Navigation Using Depth Estimation Based on Hybrid Deep Learning in Sparsely Connected Path Networks for Robustness and Low Complexity. Applied System Innovation. 2026; 9(2):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi9020029

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Saedi, Huda, Pedram Salehpour, and Seyyed Hadi Aghdasi. 2026. "Visual Navigation Using Depth Estimation Based on Hybrid Deep Learning in Sparsely Connected Path Networks for Robustness and Low Complexity" Applied System Innovation 9, no. 2: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi9020029

APA StyleAl-Saedi, H., Salehpour, P., & Aghdasi, S. H. (2026). Visual Navigation Using Depth Estimation Based on Hybrid Deep Learning in Sparsely Connected Path Networks for Robustness and Low Complexity. Applied System Innovation, 9(2), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi9020029