Abstract

Triple-cation perovskite solar cells, such as Cs0.05(FA0.83MA0.17)0.95Pb(I0.83Br0.17)3 (hereinafter referred to as CsFAMA) have high efficiency (>26%), but their stability is limited by phase segregation and defects at grain boundaries. In this work, the effect of formic acid (HCOOH) on suppressing the degradation of perovskite films is investigated. It is shown that the addition of HCOOH to the precursor solution reduces the size of colloidal particles by 90%, which contributes to the formation of highly homogeneous films with a photoluminescence intensity deviation of ≤3%. Structural analysis and dynamic light scattering measurements confirmed that HCOOH suppresses iodide oxidation and cation deprotonation, reducing the defect density. Aging tests (ISOS-D) demonstrated an increase in the T80 lifetime (time to 80% efficiency decline) from 158 to 320 days for the modified cells under ambient conditions at room temperature and 40% relative humidity. The obtained results indicate a key role of HCOOH in stabilizing CsFAMA perovskite by controlling colloidal dynamics and defect passivation, which opens up prospects for the creation of commercially viable PSCs.

1. Introduction

In recent years, halide perovskites have attracted much attention from researchers in the fields of optoelectronics and photovoltaics. Perovskite materials have a number of special properties, such as high absorption coefficient in the visible spectrum [1], tolerance to defects [2], large diffusion length of charge carriers [3], and the ability to tune the band gap by varying the chemical composition [4]. These features allow perovskites to be used in a wide range of devices, such as solar cells, photodetectors, lasers, and light-emitting diodes [5]. Currently, the efficiency of perovskite-based solar cells reaches 26.7% [6]. However, stability issues significantly limit their use in solar batteries. The general chemical formula of perovskite materials is ABX3, where X is an anion, A, B are cations. Typically, A is a monovalent cation (organic methylammonium (CH3NH3+, MA+), formamidinium (HC(NH2)2+, FA+) or inorganic Cs+), B is a divalent metal cation (Pb2+, Sb2+ Sn2+), and X is a halide ion (I−, Br−, Cl−) [7]. It is also possible to create hybrid perovskites with a mixed cation and halide, which allows for obtaining materials with new properties. Of considerable interest are perovskites with a triple cation of the FAxMAyCs1−x−y (CsFAMA) type. They have increased temperature stability compared to the most common perovskite material MAPbI3. Moreover, CsFAMA perovskites are not subject to phase transitions to the non-perovskite orthorhombic δ-phase, which is typical for FAPbI3 and CsPbI3 compositions at room temperature [8]. Solar cells with an efficiency exceeding 26% were obtained based on CsFAMA perovskites [9].

Mixed cation perovskites are the most stable and have high efficiency, but their complex composition has a significant drawback. During crystallization of CsFAMA films, phase segregation can occur with the formation of secondary phases (formation of individual FA or MA regions) [10]. These regions negatively affect the charge transfer process in the perovskite structure, increasing the contribution of recombination at grain boundaries in polycrystalline films [11]. There are various methods for suppressing phase segregation. For example, encapsulating perovskite grains or the entire active layer in a protective matrix (e.g., polymer or ceramic) can effectively isolate the material from moisture, oxygen, and heat, slowing ion migration and phase separation [12]. Another promising direction is the profound modification of the chemical composition of the perovskite itself or the creation of heterostructures at its boundaries to suppress defect formation and block degradation pathways [13]. However, such methods can complicate the technological process or require the use of expensive materials. In this regard, the search for simple and effective modifications of the precursor solution that can improve morphology and suppress degradation at the film formation stage remains a pressing task.

One of the effective methods for suppressing phase segregation is to regulate the size of colloidal particles in a solution of perovskite precursors. The perovskite precursor solution is not a true solution but rather a dispersion containing colloidal particles of complexes formed by halides and solvents [14]. The decomposition of these complexes, which releases the ions necessary for perovskite crystallization, can be induced by increasing the acidity of the solution [15]. Various acids can be used for this purpose. Literature describes the use of hydrohalic acids (HI, HBr, HCl) as an additive in the fabrication of perovskite solar cells [16]. Their use stimulates the crystallization of the perovskite film, but aqueous solutions of acids can provoke the degradation of perovskite due to the introduction of moisture. Formic acid HCOOH can be used to reduce the size of colloids. It is one of the decomposition products of dimethylformamide used in the preparation of the precursor solution. The works [15,17] provide examples of the use of formic acid HCOOH for growing perovskite crystals, the works [18,19] describe the creation of perovskite films based on MA+ and FA+; however, the creation of perovskite films with a triple cation using HCOOH remains a lesser-studied topic.

2. Materials and Methods

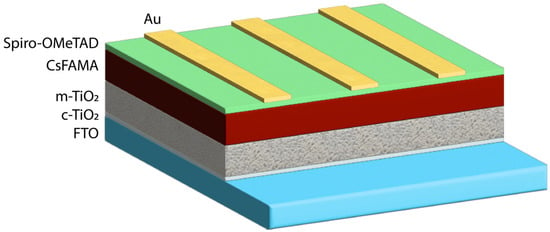

Samples of regular n-i-p mesoporous structures based on the hybrid perovskite Cs0.05(FA0.83MA0.17)0.95Pb(I0.83Br0.17)3 were fabricated. Figure 1 represents the layer arrangement FTO/c-TiO2/m-TiO2/CsFAMA/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au, which is a standard architecture for mesoscopic n-i-p perovskite solar cells. The order of the layers is dictated by the energy level alignment as well as processing constraints.

Figure 1.

Structure of the created perovskite solar cells.

The substrates coated with a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) layer were successively ultrasonic cleaned with an aqueous solution of sodium laureth sulfate, acetone and isopropanol at 50 °C for 15 min. They were then rinsed with distilled water and dried with compressed air. Before proceeding to the next step, the substrate surfaces were treated with UV radiation for 15 min to improve adhesion.

To create the electron transport layer, 0.1 mL of titanium isopropoxide solution was spin-coated on the substrate at 3000 rpm for 10 s. After that, the sample was annealed at 300 °C for 3 h. Then, to form the mesoporous layer, two solutions were prepared. In the first, 1.5 mL of titanium isopropoxide was added to 6 mL of ethanol, and in the second, 0.45 g of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was mixed with 7.5 mL of ethanol. The solutions were stirred for 30 min, then combined and stirred for 1 h, after which the resulting solution was spin-coated at a rotation speed of 1000 rpm. The samples were hot-dried at 120 °C for 30 min and then annealed at 620 °C for 1 h. The required parameters for obtaining a porous structure with a given crystallinity and grain size were determined in accordance with the results of the study in [20]. After cooling, the substrates were also UV treated for 5 min.

To create the perovskite layer, a precursor solution was prepared consisting of 0.95 mol formamidine iodide (FAI), 1.1 mol lead iodide PbI2, 0.19 mol methylammonium bromide (MABr), 0.2 mol lead bromide (PbBr2) and 0.06 mol cesium iodide (CsI). A mixture of dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in a ratio of 4:1 was used as a solvent. The precursor solution was deposited by spin-coating at 3000 rpm. Five seconds before the end of spin-coating, the samples were treated with an antisolvent–anhydrous chlorobenzene. After applying the precursor, the samples were annealed at 110 °C for 10 min.

To prevent the phase segregation of perovskite, formic acid (HCOOH) was added to the precursor solution, which effectively minimizes iodide oxidation and cation deprotonation [17]. Also, HCOOH is easily soluble in the solution and has the required redox potential to reduce only I2 molecules and I3− ions without affecting other chemicals in the precursor solution. Moreover, its reaction product is CO2, which escapes the solution without any contamination.

The hole transport layer was deposited on the annealed perovskite layer by the spin-coating method. For this purpose, a solution of Spiro-OMeTAD in chlorobenzene (20 mg/mL) with the addition of regular dopants tBP and Li-TFSI was prepared. The solution was deposited on the samples at a rotation speed of 1500 rpm. After that, the samples were annealed at 100 °C for 60 min. After 12 h of storage in a dry box at a relative humidity of less than 10%, gold contacts were deposited on the samples by vacuum thermal evaporation.

3. Results and Discussion

The effect of formic acid on the uniformity of the created CsFAMA perovskite films was investigated. By adding different volumes of HCOOH to the precursor solution, the optimal formic acid concentration was established. The uniformity of the samples was determined from photoluminescence maps. The results of the photoluminescence studies are presented in Table 1. The Pmin and Pmax parameters in Table 1 represent the minimum and maximum integrated photoluminescence intensity values, which are proportional to the total radiant power. These values were calculated by integrating the full photoluminescence spectrum (area under the spectrum curve) at each of 64 measurement points on the film surface. All measurements were performed under identical conditions (excitation source, laser power, experimental geometry). For each batch in Table 1, the minimum, average and maximum integrated intensity values were determined and averaged over five samples.

Table 1.

Photoluminescence parameters of the created samples.

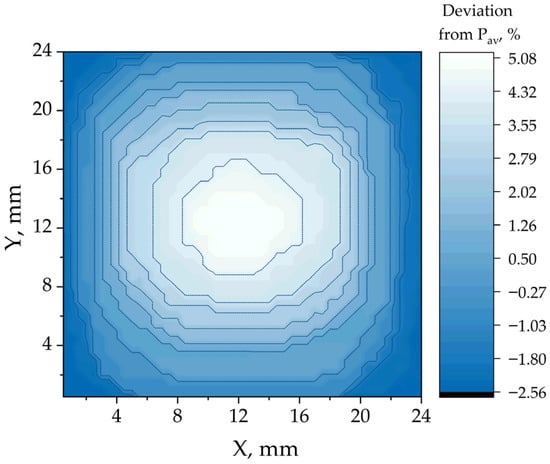

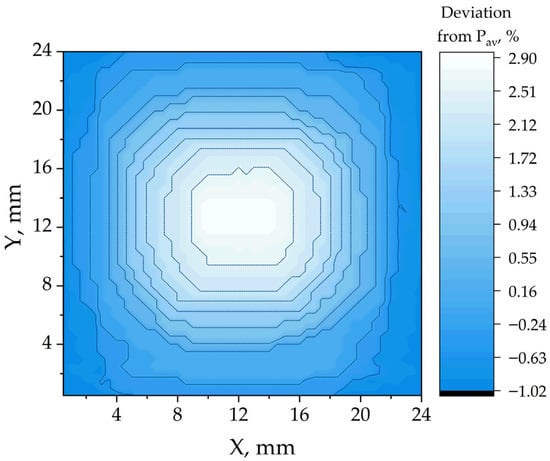

Figure 2 and Figure 3 demonstrate the photoluminescence maps (color represents the relative deviation of photoluminescence intensity from the median) of the CsFAMA perovskite film without the addition of formic acid and with 20 μL of HCOOH per 1 mL of solution, respectively. The maps were averaged for a batch of 5 samples and a lesser deviation of the photoluminescence power from the average value was obtained for perovskite films using formic acid, which indicates greater uniformity of the layer.

Figure 2.

Photoluminescence map of the CsFAMA film.

Figure 3.

Photoluminescence map of the CsFAMA + HCOOH film (20 μL/mL).

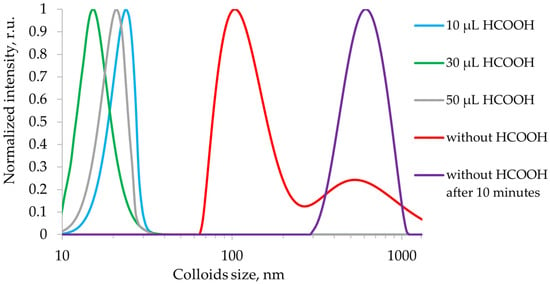

The size of the colloids in the solution was determined based on dynamic light scattering measurements. The colloid size distribution is shown in Figure 4. When HCOOH is introduced into the perovskite precursor solution, the colloidal particle size decreases by an order of magnitude (from 100 nm to 10 nm). The colloidal aggregates break up into smaller particles, which leads to faster precipitation and crystallization to form a continuous film. As the HCOOH concentration increases above 20 μL, the colloids become less stable and tend to aggregate into larger particles, which leads to decreased nucleation and deterioration of the film quality.

Figure 4.

Distribution of colloid sizes.

Addition of formic acid reduces the size of colloidal particles in the precursor solution, which increases the uniformity of the resulting perovskite film with a lower defect density [19]. Defects at the boundaries of crystalline grains can form deep levels in the band gap. These levels are nonradiative recombination centers, and their formation significantly affects the efficiency of the solar cell. In addition, the presence of structural defects accelerates the degradation of the perovskite film. The highest efficiency is achieved at 20 μL/mL HCOOH. Exceeding this concentration (50 μL/mL) leads to aggregation of colloids due to excessive protonation and disruption of the solution stoichiometry. This emphasizes the importance of precise acidity control.

Experimental data showed that the addition of formic acid to the precursor solution leads to a decrease in the size of colloidal particles from ~100 nm to ~10 nm. This effect can be explained by acid-base interactions and crystallization control. Strong acids (e.g., HI, HBr) can cause excessive protonation and disrupt the solution stoichiometry, leading to uncontrolled reactions and accelerated decomposition. The advantage of HCOOH, as a weak acid, is that it provides a mild and controlled acidic effect. It is strong enough to protonate the surface groups of PbI2-DMF/DMSO colloidal complexes, reducing their aggregation stability, but not so strong as to cause massive decomposition of the perovskite or its precursors. Formic acid promotes the disintegration of large aggregates into smaller clusters, which is confirmed by dynamic light scattering. It is also worth noting that the position of the peak and the shape of the curve in Figure 4 for the modified solution with the addition of formic acid do not change over time. The smaller size of the colloids accelerates nucleation and forms more homogeneous crystallization nuclei. As a result, dense films with a reduced grain boundary density are obtained, which is consistent with the photoluminescence data (Table 1, deviation ≤ 3% for 20 μL/mL HCOOH).

Hybrid perovskites CsFAMA are prone to segregation of cations (FA+/MA+) and halides (I−/Br−), which leads to local changes in the band gap and increased recombination. The addition of HCOOH solves this problem through stabilization of iodides and passivation of grain boundaries. HCOOH acts as a reducing agent, suppressing the oxidation of I− to I2 and the formation of iodine vacancies, which are centers of nonradiative recombination. The reaction proceeds according to the equation

The carboxyl group (–COOH) can coordinate with unreacted Pb2+ ions at the grain surface, reducing the density of deep traps. This is confirmed by the increase in the carrier lifetime and the homogeneity of the photoluminescence.

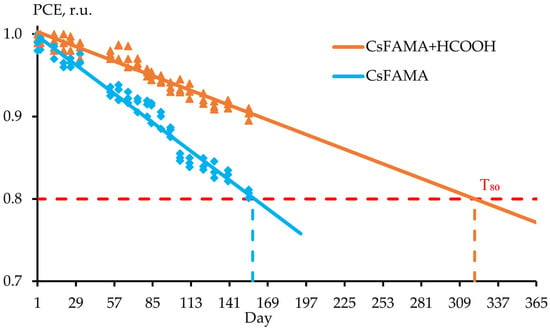

The degradation studies were performed using the ISOS-D test protocol, which included storing the samples in a dark place, at room temperature and humidity of no more than 40%. Figure 5 demonstrates a noticeable decrease in the degradation rate of the created solar cells based on the hybrid perovskite CsFAMA with the addition of formic acid for more than 100 days. Each point on the graph (Figure 5) corresponds to the average efficiency value of a batch of 5 samples. The Y-axis shows PCE values normalized to the maximum value measured on day 1 for each type of structure. Also shown in Figure 5 is the T80 level, a parameter used in ISOS protocols showing the time during which the solar cell efficiency decreases to 80% of the initial level [21]. Based on the data obtained, a linear approximation was performed and the expected time of reaching the T80 level was determined.

Figure 5.

Dependence of efficiency on storage time in days of a solar cell based on hybrid perovskite CsFAMA: 1—with the addition of formic acid and 2—without HCOOH. PCE values are normalized to the day 1 maximum for each type of structure. Each point on the graph corresponds to the average efficiency value for a batch of 5 samples. The dashed lines indicate the T80 (time to reach 80% of the initial efficiency).

It is worth noting that the addition of formic acid reduces the PSCs degradation rate by more than 2 times compared to the control batch. This conclusion was made based on the experimental data obtained on the 158th day of measurements. The degradation rate means the relative change in the efficiency of the created PSCs over a certain time. The linear approximation in Figure 5 was given for clarity of the results obtained.

Calculations show that HCOOH-treated samples achieve a T80 of 320 days under ISOS-D testing conditions. In contrast, similar n-i-p mesoscopic CsFAMA-based PSCs typically reach the T80 level in 50–100 days [22,23,24]. The enhanced stability is attributed to the role of formic acid in reducing the perovskite layer’s hygroscopicity and inhibiting halide ion migration. Additionally, unlike hydrohalic acids (e.g., HI, HBr), formic acid does not introduce water into the perovskite system during processing, minimizing the hydrolytic degradation of perovskite.

4. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that the addition of formic acid to the precursor solution is an effective strategy for improving the morphological uniformity and operational stability of CsFAMA perovskite solar cells. The obtained results underscore the key role of HCOOH in stabilizing triple-cation perovskites through colloidal control and defect passivation. The colloidal size in the initial solution plays an important role in the crystallization process, which in turn determines the growth rate and quality of the perovskite film. Therefore, suppression of defects by adding formic acid can increase the efficiency and stability of perovskite solar cells. Thus, the work opens the way to the creation of perovskite solar cells with high stability and extended lifetime without the use of expensive passivating additives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.; methodology, A.D. and A.T.; software, M.D. and D.T.; validation, A.D., A.T., M.D. and M.P.; formal analysis, A.D., A.T., M.D. and M.P.; investigation, A.D., A.T., M.D., M.P., N.K., Y.L., I.M. and D.T.; resources, I.L. and S.T.; data curation, A.D., A.T., M.D. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., A.T., M.D., N.K., Y.L. and I.M.; writing—review and editing, A.D., A.T. and M.D.; visualization, A.T. and M.D.; supervision, A.D., I.L. and S.T.; project administration, A.D., A.T. and S.T.; funding acquisition, I.L. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by project No. FSEE-2025-0013, which was carried out as part of the state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CsFAMA | Cs0.05(FA0.83MA0.17)0.95Pb(I0.83Br0.17)3 |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| HCOOH | Formic acid |

| ISOS-D | International Summit on Organic PV stability–dark-storage/shelf-life |

| PSC | Perovskite solar cells |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

References

- Yue, L.; Yan, B.; Attridge, M.; Wang, Z. Light absorption in perovskite solar cell: Fundamentals and plasmonic enhancement of infrared band absorption. Sol. Energy 2016, 124, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, D.; Park, T. Beyond Imperfections: Exploring Defects for Breakthroughs in Perovskite Solar Cell Research. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2302659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Baek, S.; Hou, Y.; Aydin, E.; Bastiani, M.; Scheffel, B.; Proppe, A.; Huang, Z.; Wei, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Enhanced optical path and electron diffusion length enable high-efficiency perovskite tandems. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albero, J.; Asiri, A.M.; García, H. Influence of the composition of hybrid perovskites on their performance in solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 4353–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Ran, C.; Gao, W.; Li, M.; Xia, Y.; Huang, W. Metal Halide Perovskite for next-generation optoelectronics: Progresses and prospects. eLight 2023, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart [Electronic resource]. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Suresh, N.; Chandra, K. A review on perovskite solar cells (PSCs), materials and applications. J. Mater. 2021, 7, 940–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.-W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Marco, N.; Lee, J.-W.; Lin, O.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y. The Emergence of the Mixed Perovskites and Their Applications as Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Bian, L.; Li, L. Perovskite solar cells with high-efficiency exceeding 25%: A review. Energy Mater. Devices 2024, 2, 9370018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lu, J.; Wang, H.; Cui, Z.; Giorgi, G.; Bai, Y.; Chen, Q. A-site phase segregation in mixed cation perovskite. Mater. Rep. Energy 2021, 1, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Dong, Q.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wei, H.; Wang, M.; Gruverman, A.; et al. Grain boundary dominated ion migration in polycrystalline organic–inorganic halide perovskite films. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1752–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luévano-Hipólito, E.; Quintero-Lizárraga, O.L.; Torres-Martínez, L.M. CO2 photoreduction using encapsulated potassium bismuth iodide (K3Bi2I9) perovskite in porous supports. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 50876–50883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Aguirre, A.A.; Kharisov, B.I.; Torres-Martínez, L.M.; Luévano-Hipólito, E. Synthesis of mixed bismuth halide perovskites M3Bi2I6Br3 (M = Cs, K) encapsulated in floating substrates with high efficiencies for visible-light-driven CO2 and H2O conversion. Sol. Energy 2025, 288, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Long, M.; Zhang, T.; Wei, Z.; Chen, H.; Yang, S.; Xu, J. Hybrid Halide Perovskite Solar Cell Precursors: Colloidal Chemistry and Coordination Engineering behind Device Processing for High Efficiency. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4460–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, P.K.; Moore, D.T.; Wenger, B.; Nayak, S.; Haghighirad, A.A.; Fineberg, A.; Noel, N.K.; Reid, O.G.; Rumbles, G.; Kukura, P.; et al. Mechanism for rapid growth of organic–inorganic halide perovskite crystals. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Ren, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, W.; Ye, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Dai, S. Identification and characterization of a new intermediate to obtain high quality perovskite films with hydrogen halides as additives. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Z.; Ke, W.; Feng, J.; Ren, X.; Zhao, K.; Liu, M.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; et al. Inch-sized high-quality perovskite single crystals by suppressing phase segregation for light-powered integrated circuits. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, N.K.; Congiu, M.; Ramadan, A.J.; Fearn, S.; McMeekin, D.P.; Patel, J.B.; Johnston, M.B.; Wenger, B.; Snaith, H.J. Unveiling the Influence of pH on the Crystallization of Hybrid Perovskites, Delivering Low Voltage Loss Photovoltaics. Joule 2017, 1, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wei, Q.; Yang, Z.; Yang, D.; Feng, J.; Ren, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. Improved perovskite solar cell efficiency by tuning the colloidal size and free ion concentration in precursor solution using formic acid additive. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 41, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Granados, A.; Corpus-Mendoza, A.N.; Moreno-Romero, P.M.; Rodríguez-Castañeda, C.A.; Pascoe-Sussoni, J.E.; Castelo-González, O.A.; Menchaca-Campos, E.C.; Escorcia-García, J.; Hu, H. Optically uniform thin films of mesoporous TiO2 for perovskite solar cell applications. Opt. Mater. 2019, 88, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khenkin, M.V.; Katz, E.A.; Abate, A.; Bardizza, G.; Berry, J.J.; Brabec, C.; Brunetti, F.; Bulović, V.; Burlingame, Q.; Carlo, A.D.; et al. Consensus statement for stability assessment and reporting for perovskite photovoltaics based on ISOS procedures. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanipour, M.; Behjat, A.; Shabani, A.M.H.; Haddad, M.A. Toward Desirable 2D/3D Hybrid Perovskite Films for Solar Cell Application with Additive Engineering Approach. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 12953–12964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, F.L.; Stefanelli, M.; Agresti, A.; Pescetelli, S.; Di Vito, A.; Der Maur, M.A.; Vesce, L.; Nogueira, A.F.; Di Carlo, A. Empowering Perovskite Modules for Solar and Indoor Lighting Applications by 1,8-Diiodooctane/Phenethylammonium Iodide 2D Perovskite Passivation Strategy. Nano Energy 2025, 142, 111279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Usulor, C.E.; Khampa, W.; Musikpan, W.; Passatorntaschakorn, W.; Tipparak, P.; Seriwattanachai, C.; Nakajima, H.; Ngamjarurojana, A.; Gardchareon, A.; et al. Facile Ethylvanillin Passivation for High-Performance CsFA Perovskite Solar Cells in Variable Lighting Environments. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 7616–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).