Abstract

The formation of mixed adsorption layers of amyloid fibrils of a plant protein, oat globulin (OG), and a strong polyelectrolyte, sodium polystyrene sulfonate (PSS), at the liquid–gas interface was studied by measurements of the kinetic dependencies of surface tension, dynamic surface elasticity, and ellipsometric angle. The micromorphology of the layers was determined by atomic force microscopy. A strong increase in the surface elasticity was discovered when both components had similar concentrations and formed a network of threadlike aggregates at the interface, thereby explaining the high foam stability in this concentration range. The sequential adsorption of PSS and OG resulted in the formation of thick mixed multilayers and the surface elasticity increased with the number of duplex layers.

1. Introduction

The interaction of amyloid fibrils with polyelectrolytes has attracted attention for many years in connection with the problem of neurological disorders. While some polyelectrolytes can promote the growth of proteinaceous deposits in the tissues of patients with amyloid diseases, the other charged polymers can be employed for the destruction of amyloids in the human body [1,2,3,4]. More recently, the application of amyloid fibrils for the creation of new materials in various branches of industry and medicine has led to a problem of modulating their properties by various additives, in particular by polyelectrolytes. It has been shown that the addition of charged polysaccharides to the films of fibril-based bioplastics increases their tensile strength and water resistance [5], while the addition of natural polyelectrolytes to amyloid fibril hydrogels and aerogels can improve their microstructure and, thus, their mechanical properties, enhancing, in particular, their resistance to compression [6,7]. Yuan and Solin have recently shown that aerogels containing protein fibrils and an electrically conductive polyelectrolyte can be used as piezoresistive pressure sensors [8]. Delivery systems of bioactive substances are a new application of the complexes of protein fibrils with polyelectrolytes [9,10].

Fibrils in most of the applications of the fibril/polyelectrolyte complexes mentioned above are produced from plant proteins [5,7,9,10]. The exchange of animal-based proteins for their plant-derived counterparts in various technologies is a sustainable development, and it is a consequence of the abundance and the ease of access of plant proteins [11,12]. Moreover, their production is less harmful to the environment compared to animal proteins. At the same time, the intensive investigation of fibrils of plant proteins has only recently started, and their properties, the mechanism of their formation, and the properties of their dispersions remain poorly studied [13,14]. Although it has been shown recently that the surface dilational elasticity of fibril dispersions can exceed the values for native protein solutions [15,16,17], and protein fibrils can be effective stabilizers of foams and emulsions [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], any information on the surface properties of the fibril dispersions is rather scarce and relates mainly to fibrils of animal proteins [16,17,29]. Only a few studies have been devoted to the interactions between fibrils and polyelectrolytes at liquid–fluid interfaces. Peydayesh et al. showed that the interactions of β-lactoglobulin (BLG) with hyaluronic acid led to the formation of an asymmetric and highly ordered structure in the surface layer [30]. Very recently, our group discovered a significant increase in the dilational dynamic surface elasticity of BLG fibril dispersions under the influence of small additions of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) and studied the formation of mixed multilayers of PSS and BLG fibrils at the water–air surface [31]. In spite of the peculiar properties of the dispersions of plant protein fibrils, their strong interactions with polyelectrolytes in bulk phases [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,9,10], and the effective application of these fibrils for the stabilization of foams [11,14,15,27,28], the mixed adsorption layers of plant protein fibrils and strong polyelectrolytes have not been investigated yet, to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, this work is devoted to mixed adsorption layers of a typical synthetic polyelectrolyte, PSS, and fibrils of a plant protein—oat globulin (OG)—at the liquid–air interface. This protein forms typical fibres at elevated temperatures and pH 2, and the properties of their dispersions have been studied by some authors [13,32,33,34]. One of the aims of this work is to evaluate the peculiarities of the mixed OG/PSS adsorption layers and to determine the conditions required for the development of high dynamic surface elasticity of the mixed dispersions. Another aim consists of the preparation of multilayers at the water–air interface containing fibrils of a plant protein.

2. Materials and Methods

OG was extracted from defatted and ground oat groats according to the procedure described by Zhou et al. [32]. PSS (Mw ≈ 70,000 Da, Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was used as received. Protein fibrils were prepared from freeze-dried OG after purification by dialysis. The protein was dissolved in triply distilled water at pH 2 and heated up to 90 °C for 18 h with stirring. After that, the prepared dispersion of mature OG fibrils was centrifuged (12,000× g) for 4.5 h to obtain purified fibrils (pFOGs). Protein stock solutions and fibril dispersions were stored in a refrigerator for no longer than 2 days and 1 month, respectively. The solutions of native OG and fibril dispersions of given concentrations were prepared by dilution of the stock solutions and dispersions and mixed a few minutes before measurements at 22 °C. The final fibril concentration of the stock aqueous dispersion was estimated gravimetrically. The fibril concentration of all investigated systems was 20 mg/L, while the PSS concentration varied from 0.2 mg/L to 2 g/L. The pH of the investigated solutions and dispersions was reduced to 3 by HCl additions. This pH was low enough to ensure the solubility of the fibrils in water.

2.1. Surface Tension and Dynamic Surface Elasticity

The surface tension was measured by the Wilhelmy plate method using a ground platinum plate. The accuracy of the measurements was approximately ±0.2 mN/m.

The dynamic dilatational surface elasticity was determined by the oscillating barrier method using the ISR instrument KSV NIMA (Helsinki, Finland), as previously described [29,35]. The oscillations of two barriers in the Langmuir trough with the frequency and amplitude of 0.03 Hz and 4%, respectively, led to oscillations of the surface area and thus of the surface tension.

The real εre and imaginary εim components of the complex dilatational dynamic surface elasticity ε were calculated according to the following relation:

where δγ and δlnA are the increments (amplitude of oscillations) of the surface tension and relative surface area, respectively. The experimental errors of the oscillating barrier method are mainly determined by the errors of the surface tension measurements and were approximately ±5%. The imaginary component of the surface elasticity is significantly smaller than the real component, so only the latter one will be discussed further below.

2.2. Ellipsometry

A null ellipsometer NTEGRA Prima instrument (Optrel-GBR, Berlin, Germany) with a laser wavelength of 623.8 nm was applied to estimate the changes in the surface concentration in the course of adsorption. The ellipsometric angle Δ is expected to be proportional to the surface concentration [36]. The measurements were taken at an angle close to the Brewster angle.

2.3. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

To estimate the micromorphology of the adsorption layer, it was transferred from the liquid surface onto a freshly cleaved mica plate using the Langmuir–Schaeffer method, and the plate with the layer was dried in a desiccator for more than 24 h. After that, the layer on the plate was investigated by the atomic force microscope (NTEGRA Prima instrument, NT-MDT, Moscow, Russia) in a semi-contact mode. The cantilever has an approximate curvature radius of 10 nm.

2.4. Dynamic Light Scattering

The size of the protein particles and their ζ-potential in the bulk phase were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer ZS Nano analyzer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The measurements were carried out at a scattering angle of 173°. The Smoluchowski equation was used in the course of calculating the ζ-potential.

3. Results and Discussion

OG forms relatively rigid fibrils with lengths of up to a few microns, similar to those of BLG and lysozyme fibrils [29], but strongly different from curly fibrils of bovine serum albumin [37]. AFM images of a dispersion drop dried on a mica surface show aggregates of different diameters from 2 up to 6 nm (see Figure S1 of the Supporting Information). The thinnest aggregates are presumably single protofilaments, while the thicker ones consist of a few tightly packed protofilaments.

The dynamic light scattering shows that at low PSS concentrations (<2 mg/L), the size distribution of the aggregates in dispersions of mixed OG/PSS fibrils is bimodal and similar to that of pure OG fibril dispersions (see Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). The main peak of the scattered intensity close to 400 nm presumably corresponds to long fibrils and the smaller peak close to 50 nm can correspond to the admixture of peptides of lower molecular weight. A further increase in PSS concentration leads to a more complex size distribution. The main peak shifts in the direction of larger particle sizes, and at PSS concentrations higher than approximately 5 mg/L, the number of peaks increases, indicating a strongly polydisperse system of mixed aggregates with a possible contribution of free PSS molecules or their aggregates. The largest aggregates corresponding to the main peak at 700 nm appear at a concentration of 20 mg/L.

The increase in the PSS concentration is accompanied by significant changes in the ζ-potential of the aggregates from positive values (~40 mV for pure OG fibrils) to negative ones (~−60 mV at the PSS concentration of 20 mg/L) (Table 1). The change in the sign of the ζ-potential and the subsequent strong increase in its absolute values in this case reflect the effective binding of the negatively charged polyelectrolyte by OG fibrils. The formation of stable large aggregates leads to a decrease in their diffusion coefficients.

Table 1.

ζ-potential of the complexes of OG fibrils and PSS.

The growth of the aggregates with high absolute values of ζ-potential leads to an increase in the electrostatic barrier in the course of adsorption and decelerates the formation of adsorption layers.

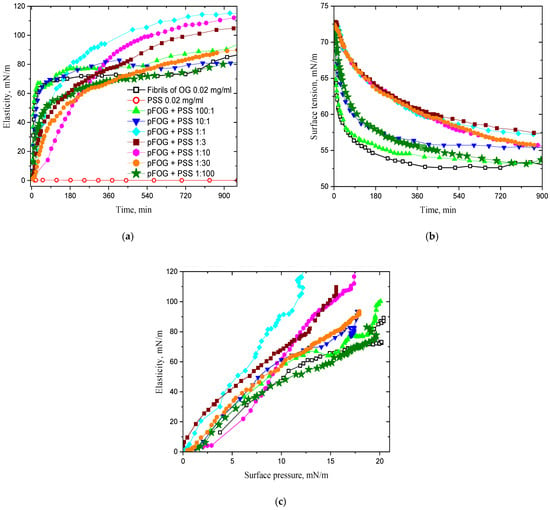

The kinetic dependencies of surface tension and dynamic surface elasticity of the dispersions of the complexes of OG fibrils and PSS at low PSS concentrations (≤20 mg/L) coincide with the results for pure fibril dispersions without the polyelectrolyte (Figure 1). In this case, the PSS molecules are almost not adsorbed at the water surface due to their low surface activity [38], and the adsorption layer is formed mainly at the expense of the fibril transition from the bulk phase to the surface of the dispersion.

Figure 1.

Kinetic dependencies of the dynamic surface elasticity (a), dynamic surface tension (b); dependencies of the dynamic surface elasticity on surface pressure for OG fibrils/PSS dispersions (c) at a fixed OG fibril concentration of 20 mg/L and OG/PSS molar ratios 100:1 (light green triangles), 10:1 (blue triangles), 1:1 (cyan diamonds), 1:3 (wine squares), 1:10 (magenta hexagons), 1:30 (orange circles), and 1:100 (olive asterisks) at pH 3. Open black squares correspond to pure OG dispersions and open red circles to 20 mg/L PSS solutions.

The increase in the PSS concentration leads to significant changes in the adsorption layer structure and surface properties. The formation of complexes of high surface activity from PSS molecules and OG fibrils results in a compaction of the layer structure and an increased dynamic surface elasticity. Noticeable changes in the surface properties occur in the PSS concentration range of 5–100 mg/L, where the steady-state values of the dynamic surface elasticity can be almost two times the values of pure fibril dispersions (Figure 1). The surface elasticity decreases with a further increase in the PSS concentration and reaches almost the values of pure fibril dispersions without any additions. Although PSS starts to decrease the surface tension of water at concentrations higher than approximately 1 g/L, the PSS adsorption is insufficient to explain the changes in the surface properties of the mixed dispersions at PSS concentrations higher than 200 mg/L. Even at the polyelectrolyte concentration of 2 g/L the surface elasticity and the surface pressure of mixed fibrils/PSS dispersions are higher than those of pure PSS solutions (Figures S1 and S3 of the Supporting Information). This means that PSS does not displace fibrils entirely from the interface even if its mass concentration exceeds 100 times that of the fibrils, and some fibrils/PSS complexes are still preserved in the proximal region of the surface layer.

The increase in the PSS concentration from approximately 5 mg/L leads also to the deceleration of the changes in surface properties (Figure 1a,b). This effect can be explained partly by an increase in the electrostatic adsorption barrier when the negative charge of the complexes increases at the expense of the increase in the number of PSS molecules in the complex. In addition, the increase in the size of fibrils/PSS aggregates in the dispersion (cf. Figure S2 of the Supporting Information) is accompanied by a decrease in the diffusion coefficient of the complexes and, thereby, by a deceleration of the mass exchange between the bulk phase and the surface layer. The observed effect is especially significant in the PSS concentration range 5–100 mg/L corresponding to the existence of large fibrils/PSS aggregates.

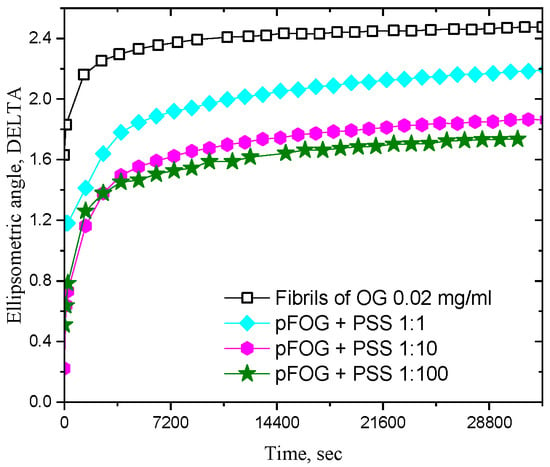

Figure 2 shows the kinetic dependencies of the difference in the ellipsometric angle ∆ of the dispersion and its value for pure water Δ0. This difference decreases with increasing PSS concentration, especially at concentrations above 20 mg/L, and the observed effect corroborates an increase in the polyelectrolyte concentration in the surface layer and the concomitant decrease in the relative fibril surface concentration. Note that the refractive index of the surface layer of PSS solutions is much less than that of the layer of protein solutions at the same concentrations [31]. The adsorbed fibrils/PSS complexes contain a larger amount of PSS molecules at increased polyelectrolyte concentrations and the ellipsometric angle decreases. Simultaneously, the ellipsometric angle increases much more slowly, with the surface age indicating a decrease in the diffusion coefficient of the kinetic units in the bulk phase as a result of aggregate growth.

Figure 2.

Kinetic dependencies of the ellipsometric angle DELTA for pFOG/PSS adsorption layers at a fixed OG fibril concentration of 20 mg/L and OG/PSS molar ratios 1:1 (cyan diamonds), 1:10 (magenta hexagons), and 1:100 (olive asterisks) at pH 3. Open black squares correspond to pure OG dispersions.

AFM images of the mixed adsorption layers of fibrils/PSS dispersions are similar to those of pure layers of protein fibrils. With the increased PSS concentration, the number of visible separate fibrils in the layer decreases strongly and one can observe mainly a heterogeneous layer without the possibility to distinguish separate aggregates and to estimate their shape (see Figure S4 of the Supporting Information).

The opposite signs of the charges of OG fibrils and PSS molecules at pH 3 allow us to assume that mixed fibrils/PSS multilayers form if the polyelectrolyte molecules and fibrils are adsorbed sequentially at the liquid–gas interface. Multilayers are really formed in the case of a consecutive adsorption of an animal protein, BLG, and the polyelectrolyte PSS [31]. Although PSS is characterized by a relatively weak surface activity, it forms monolayers at the surface of aqueous solutions at a concentration of ~10 g/L. Its adsorption is almost irreversible and the replacement of PSS solution below the adsorption layer by pure water did not lead to noticeable changes in the surface properties. The subsequent replacement of water with a dilute dispersion of BLG fibrils resulted in the formation of a fibril layer at the interface, leading to noticeable changes in the surface properties. This procedure can be repeated a few times, leading to the formation of a relatively thick mixed layer at the interface [31].

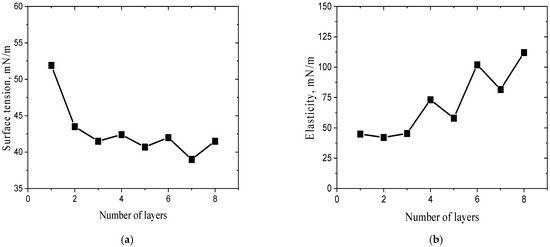

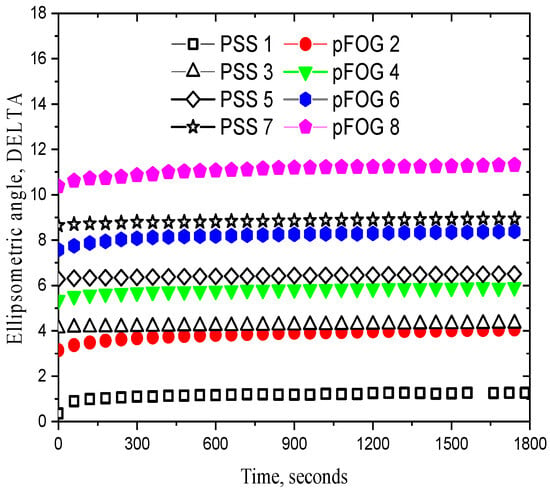

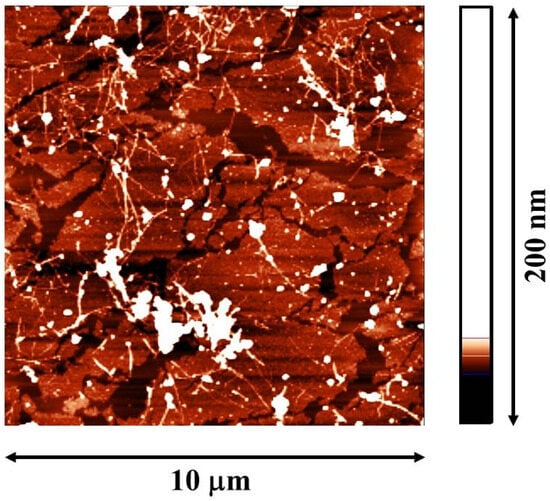

Approximately the same procedure was used in this study to prepare a mixed layer of the fibrils of a plant protein, OG, and PSS. The polyelectrolyte adsorption from a 10 g/L solution led to a drop in the surface tension to ~52 mN/m and an increase in the dynamic surface elasticity up to ~45 mN/m (Figure 3a,b). Simultaneously, the ellipsometric angle Δ increased by approximately 1 degree (Figure 4). The subsequent exchange in the PSS solution by water and after that by a 170 mg/L dispersion of OG fibrils resulted in insignificant changes in the surface elasticity and a further drop in the surface tension to ~43 mN/m (Figure 3). The relative changes in the angle Δ were much higher due to the OG fibril adsorption, which was accompanied by a strong increase in the refractive index of the adsorption layer (Figure 4). The subsequent processes of the replacement of the fibril dispersion by PSS solutions and the replacement of these solutions by the fibril dispersions again and so on led to almost periodical changes in the surface properties (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Presumably, this procedure made it possible to obtain a structure of alternating layers of PSS and OG fibrils, as in the case of the mixed heterogeneous adsorption layers of PSS and BLG fibrils showing an alternating layer structure [31] (Figure 5). The surface tension decreases significantly only during the adsorption of the first fibril layer, while the adsorption of the subsequent layers leads only to slighter changes. This peculiarity indicates that the surface tension is determined mainly by the concentration of amphiphilic substances in the first monolayer at the interface. On the contrary, the dynamic surface elasticity shows very little change in the course of the formation of the first three layers, as a result of the relatively loose structure of these layers, unlike stronger changes during the formation of the subsequent denser duplex layers [31,39]. These findings are in agreement with the results of the preceding studies on the dependence of the surface elasticity on the thickness of the interfacial layer [39,40,41] and the inhomogeneity of the first PSS adsorption layer [38]. Unlike the dynamic surface elasticity and surface tension, the ellipsometric angle is an approximately linear function of the number of duplex layers (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Dependencies of surface tension (a) and dynamic surface elasticity (b) as a function of the number of monolayers of OG fibrils and PSS in the adsorption multilayer. The pH of subphase was 3.

Figure 4.

Kinetic dependencies of the ellipsometric angle Δ of mixed multilayers formed by the consecutive adsorption of PSS (black open symbols) and OG fibrils (closed coloured symbols): 1 (squares), 2 (circles), 3 (triangles up), 4 (triangles down), 5 (diamonds), 6 (hexagons), 7 (asterisks), and 8 (pentagons) layers. The pH of the subphase was 3.

Figure 5.

The AFM image of 8 OG fibrils/PSS layers. The multilayer was transferred from the water–air surface on the surface of mica.

The obtained results show that the fibrils of plant proteins can also form thick mixed layers with strong polyelectrolytes at liquid–fluid interfaces, like the fibrils of animal proteins [31]. There are only a few not very significant quantitative differences between the dependencies of the surface properties of the multilayers on the number of adsorption cycles for OG fibrils/PSS and BLG fibrils/PSS systems. In the latter case, for example, the dynamic surface elasticity is somewhat higher, ~185 mN/m against 115 mN/m in the latter case. This difference in the surface elasticity can lead to the higher stability of foams for BLG fibrils/PSS dispersions, but it is difficult to anticipate a significant difference in the foam stability because both values are high—much higher than the surface elasticity of the corresponding native protein solutions.

4. Conclusions

The influence of a polyelectrolyte on the surface properties of dispersions of plant protein fibrils has been studied for the first time, to the best of our knowledge. Although the surface activity of PSS is low, it starts to change the surface properties of the dispersions of OG fibrils at concentrations much less than those corresponding to a noticeable decrease in the surface tension of water, thereby indicating the formation of fibrils/PSS complexes in the surface layer. If the mass concentrations of OG fibrils and PSS are comparable, the surface properties change significantly and the dynamic surface elasticity of the mixed dispersions can exceed twice the values of pure fibril dispersions. This effect can indicate a strong impact of polyelectrolytes on the properties of foams and emulsions stabilized by plant proteins. A further increase in PSS concentration does not lead to the complete displacement of the protein from the interface, and the complexes are still present in the surface layer. The consecutive adsorption of protein and polyelectrolyte at the dispersion–air interface results in the formation of thick fibrils/PSS multilayers with a high dynamic surface elasticity (>100 mN/m), if the number of cycles of fibril and polyelectrolyte adsorption is sufficiently high. Although these values are somewhat lower than in the case of multilayers of an animal protein (BLG) and PSS, they can result in peculiar properties of the corresponding dispersion systems. If the number of adsorbed layers is less than about three, the dynamic elasticity is almost close to that of a monolayer, presumably due to a loose and heterogeneous surface structure in this case.

Supplementary Materials

The following Supporting Information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/colloids9060089/s1, Figure S1: AFM image of OG unpurified fibrils; Figure S2: DLS results for the dispersions of OG fibrils (A) and OG fibrils/PSS at an OG/PSS molar ratio of 10:1 (B); Figure S3: Kinetic dependencies of the dynamic surface elasticity (A), dynamic surface tension (B); dependencies of the dynamic surface elasticity on surface pressure for PSS solutions (C). Filled black squares correspond to 20 mg/L PSS solutions, open magenta circles to 2 g/L PSS solutions; Figure S4: AFM images of mixed adsorption layers of OG fibrils/PSS complexes at various OG/PSS molar ratios: 100:1 (A), 10:1 (B), 1:1 (C), 1:10 (D).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.B. and B.A.N.; methodology, A.G.B.; software, G.L.; validation, E.A.T. and R.M.; formal analysis, E.A.T.; investigation, E.A.L. and A.G.B.; data curation, A.D.K. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.N. and A.D.K.; writing—review and editing, R.M., G.L. and B.A.N.; supervision, B.A.N., A.G.B. and E.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge Saint-Petersburg State University for providing funding (research project Pure ID: 131065423).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The use of the equipment of the Resource Centre for Diagnostics of Functional Materials for Medicine, Pharmacology and Nanoelectronics; the Chemical Analysis and Materials Research Centre; the Centre for Diagnostics of Functional Materials for Medicine, Pharmacology and Nanoelectronics; the Interdisciplinary Resource Centre for Nanotechnology; and the Resource Centre for Molecular and Cell Technologies of SPbU is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Calamai, M.; Kumita, J.R.; Mifsud, J.; Parrini, C.; Ramazzotti, M.; Ramponi, G.; Taddei, N.; Chiti, F.; Dobson, C.M. Nature and Significance of the Interactions between Amyloid Fibrils and Biological Polyelectrolytes. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 12806–12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenyuk, P.; Kurochkina, L.; Barinova, K.; Muronetz, V. Alpha-Synuclein Amyloid Aggregation Is Inhibited by Sulfated Aromatic Polymers and Pyridinium Polycation. Polymers 2020, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Argueta, E.; Wojcikiewicz, E.P.; Du, D. Effects of Charged Polyelectrolytes on Amyloid Fibril Formation of a Tau Fragment. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 3034–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makshakova, O.; Bogdanova, L.; Faizullin, D.; Khaibrakhmanova, D.; Ziganshina, S.; Ermakova, E.; Zuev, Y.; Sedov, I. The Ability of Some Polysaccharides to Disaggregate Lysozyme Amyloid Fibrils and Renature the Protein. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nian, Y.; Shi, Q.; Hu, B. Protein Fibrillation and Hybridization with Polysaccharides Enhance Strength, Toughness, and Gas Selectivity of Bioplastic Packaging. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 9884–9901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuelli, M.; Germerdonk, T.; Cao, Y.; Peydayesh, M.; Bagnani, M.; Handschin, S.; Nyström, G.; Mezzenga, R. Polysaccharide-Reinforced Amyloid Fibril Hydrogels and Aerogels. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 12534–12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-H.; Li, X.-Y.; Huang, C.-L.; Liu, P.; Zeng, Q.-Z.; Yang, X.-Q.; Yuan, Y. Development and Mechanical Properties of Soy Protein Isolate-Chitin Nanofibers Complex Gel: The Role of High-Pressure Homogenization. Lebensm.-Wiss. Technol. 2021, 150, 112090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Solin, N. Protein-Based Flexible Conductive Aerogels for Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 3360–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Yu, X.-H.; Zhang, J.-W.; Jiang, Y.-X.; Chen, H.-Q. The Complex of Arachin Amyloid-like Fibrils Formed with Ultrasound Treatment and Chitosan: A Potential Vehicle for Betanin and Curcumin with Improved Chemical Stability and Slow Release In Vitro. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 166, 111272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, M.; Xu, Z.; Dong, X.; Ding, X.; Zhou, X.; Cui, P. Novel Fava Bean 11S Nanofiber Gels for Sustained Ergothioneine Delivery: A Calcium Ion and κ-Carrageenan Approach. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 169, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhou, J.; Peydayesh, M.; Yao, Y.; Bagnani, M.; Kutzli, I.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Mezzenga, R. Plant Protein Amyloid Fibrils for Multifunctional Sustainable Materials. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2023, 7, 2200414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peydayesh, M.; Bagnani, M.; Soon, W.L.; Mezzenga, R. Turning Food Protein Waste into Sustainable Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2112–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Tang, M.; Wang, D.; Xie, Q.; Xu, X. Exploring the Self-Assembly Journey of Oat Globulin Fibrils: From Structural Evolution to Modified Functionality. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; He, B.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J. Plant-Based Protein Amyloid Fibrils: Origins, Formation, Extraction, Applications, and Safety. Food Chem. 2025, 469, 142559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Z.; Yang, X.; Sagis, L.M.C. Nonlinear Surface Dilatational Rheology and Foaming Behavior of Protein and Protein Fibrillar Aggregates in the Presence of Natural Surfactant. Langmuir 2016, 32, 3679–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noskov, B.; Loglio, G.; Miller, R.; Milyaeva, O.; Panaeva, M.; Bykov, A. Dynamic Surface Properties of α-Lactalbumin Fibril Dispersions. Polymers 2023, 15, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyaeva, O.Y.; Akentiev, A.V.; Bykov, A.G.; Loglio, G.; Miller, R.; Portnaya, I.; Rafikova, A.R.; Noskov, B.A. Dynamic Properties of Adsorption Layers of κ-Casein Fibrils. Langmuir 2023, 39, 15268–15274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboroceanu, D.; Wang, L.; Magner, E.; Auty, M.A.E. Fibrillization of Whey Proteins Improves Foaming Capacity and Foam Stability at Low Protein Concentrations. J. Food Eng. 2014, 121, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Simon, J.R.; Venema, P.; van der Linden, E. Protein Fibrils Induce Emulsion Stabilization. Langmuir 2016, 32, 2164–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, S.M.; Anema, S.G.; Singh, H. β-Lactoglobulin Nanofibrils: The Long and the Short of it. Int. Dairy J. 2017, 67, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Tang, C.; Li, B. Foams Stabilized by β-Lactoglobulin Amyloid Fibrils: Effect of PH. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10658–10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, R.A.; de Figueiredo Furtado, G.; Netto, F.M.; Cunha, R.L. Assessing the Potential of Whey Protein Fibril as Emulsifier. J. Food Eng. 2018, 223, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Nishinari, K.; Phillips, G.O.; Fang, Y. Comparative Study on Foaming and Emulsifying Properties of Different Beta-Lactoglobulin Aggregates. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 5922–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Pan, Y.; Peng, D.; Huang, W.; Shen, W.; Jin, W.; Huang, Q. Tunable Self-Assemblies of Whey Protein Isolate Fibrils for Pickering Emulsions Structure Regulation. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhu, L.; Karrar, E.; Qi, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, G. Pickering Foams Stabilized by Protein-Based Particles: A Review of Characterization, Stabilization, and Application. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyst, A.M.R.; Van der Meeren, P.; Housmans, J.A.J.; Monge-Morera, M.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.; Delcour, J.A. Improved Coalescence and Creaming Stability of Structured Oil-in-Water Emulsions and Emulsion Gels Containing Ovalbumin Amyloid-like Fibrils Produced by Heat and Enzymatic Treatments. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 145, 109142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Xu, T.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; Wang, Z.; Tong, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Exploring the Interfacial Behavior and Foam Characteristics of Various Soy Protein Aggregates: Insights of Morphology and Conformational Flexibility. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 166, 111362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, C.; Yu, X.; Fu, L.; Tang, X.; Feng, X. Enhance Quinoa Protein Foaming Properties through Amyloid-like Fibrillation and 2S Albumin Blending. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 164, 111154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskov, B.A.; Akentiev, A.V.; Bykov, A.G.; Loglio, G.; Miller, R.; Milyaeva, O.Y. Spread and Adsorbed Layers of Protein Fibrils at Water –Air Interface. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 220, 112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peydayesh, M.; Kistler, S.; Zhou, J.; Lutz-Bueno, V.; Victorelli, F.D.; Meneguin, A.B.; Spósito, L.; Bauab, T.M.; Chorilli, M.; Mezzenga, R. Amyloid-Polysaccharide Interfacial Coacervates as Therapeutic Materials. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykov, A.G.; Loglio, G.; Miller, R.; Tsyganov, E.A.; Wan, Z.; Noskov, B.A. Mixed Adsorption Mono- and Multilayers of ß-Lactoglobulin Fibrils and Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate. Colloids Interfaces 2024, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, T.; Peydayesh, M.; Usuelli, M.; Lutz-Bueno, V.; Teng, J.; Wang, L.; Mezzenga, R. Oat Plant Amyloids for Sustainable Functional Materials. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khrebina, A.D.; Akentiev, A.V.; Wan, Z.; Noskov, B.A. Dynamic Surface Properties of Oat Protein Dispersions. Mendeleev Commun. 2025, 35, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tang, M.; Xu, X. Effect of Ultrasound Pretreatment on the Fibrillization of Oat Globulins: Aggregation Kinetics, Structural Evolution, and Core Composition. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 165, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskov, B.A.; Krycki, M.M. Formation of Protein/Surfactant Adsorption Layer as Studied by Dilational Surface Rheology. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 247, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motschmann, H.; Teppner, R. Ellipsometry in Interface Science. In Novel Methods to Study Interfacial Layers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 11, pp. 2–42. [Google Scholar]

- Akentiev, A.; Lin, S.-Y.; Loglio, G.; Miller, R.; Noskov, B. Surface Properties of Aqueous Dispersions of Bovine Serum Albumin Fibrils. Colloids Interfaces 2023, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noskov, B.A.; Nuzhnov, S.N.; Loglio, G.; Miller, R. Dynamic Surface Properties of Sodium Poly(Styrenesulfonate) Solutions. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 2519–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivard, S.; Jacomine, L.; Kratz, F.S.; Foussat, C.; Lamps, J.-P.; Legros, M.; Boulmedais, F.; Kierfeld, J.; Schosseler, F.; Drenckhan, W. Interfacial Rheology of Linearly Growing Polyelectrolyte Multilayers at the Water–Air Interface: From Liquid to Solid Viscoelasticity. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safouane, M.; Miller, R.; Möhwald, H. Surface Viscoelastic Properties of Floating Polyelectrolyte Multilayers Films: A Capillary Wave Study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 292, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, A.D.; Dong, W.-F.; Benbow, N.L.; Webber, J.L.; Krasowska, M.; Beattie, D.A.; Ferri, J.K. The Influence of Polyanion Molecular Weight on Polyelectrolyte Multilayers at Surfaces: Elasticity and Susceptibility to Saloplasticity of Strongly Dissociated Synthetic Polymers at Fluid–Fluid Interfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 23781–23789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).