Abstract

This study explores the potential of integrating thermoplastic surfaces into fiber-reinforced plastics (FRPs) to eliminate the need for extensive surface preparation prior to bonding. Traditional bonding techniques for FRPs, especially in aerospace applications, demand meticulous surface preparation to ensure adequate adhesion. As a potential alternative to conventional methods for generating adhesion, the formation of an interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) by diffusion of the epoxy monomers into a thermoplastic surface layer is investigated. The research involved manufacturing CFRP panels with thermoplastic surfaces, polyether sulfone (PES), and polyetherimide (PEI), followed by a bonding process with and without conventional surface preparation. The performance of the joints was tested by tensile shear and Mode-I fracture toughness tests and compared to reference samples without thermoplastic surfaces. The formation and characteristics of the IPNs were analyzed using optical microscopy, laser scanning microscopy, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. The results demonstrate that PES surfaces, even without surface treatment, can provide high mechanical performance with shear strengths ranging from 18 MPa to 23 MPa. PEI surfaces led to a shear strength from 10 MPa up to 14 MPa, correlating to a less extensive IPN formation compared to PES. However, both thermoplastics significantly improved the bonding process performance without surface preparation.

1. Introduction

In the field of aerospace engineering, the performance optimization mission leads to continuous innovation in the design and materials used. Among these, the use of FRPs represents a significant advancement due to their high strength-to-weight ratios, corrosion resistance, and flexibility in design. However, the assembly of these materials to load-bearing structures remains a critical challenge, especially in the civil aerospace sector, where reliability and safety are crucial. Structural bonding, as opposed to mechanical fastening, offers a promising solution owing to its potential for lightweight construction and its ability to distribute stresses more evenly. Bonding also aligns with the ongoing shift towards more integrated and efficient designs, as it enables dustless assembly.

1.1. Challenges in Structural Bonding

Despite the advantages, the application of bonding technology, especially for structural components made of FRPs, has been limited in large passenger aircrafts. One significant hurdle is the necessity for the meticulous surface preparation of the components to be bonded [1,2,3]. Common methods are not only cost-intensive but also introduce the risk of inadequately preparing the surface. The verification of surface conditions prior to bonding presents additional challenges, especially outside controlled laboratory environments, complicating the assurance of the bond quality and integrity.

1.2. The Role of Surface Treatment

The need for the surface treatment of FRPs for structural bonding arises from the inherent characteristics of commonly used materials and manufacturing processes, where surface layers with no effective adhesion mechanisms are built [4,5,6,7]. Adhesion mechanisms, which are crucial for the successful application of adhesives, involve physical and chemical interactions at the interface between the adhesive and the substrate. Recent reviews and articles [8,9,10,11] summarize common pretreatment strategies for adhesive bonded joints, including the use of peel ply, grinding/blasting, plasma treatment, laser treatment, and chemical functionalization, and state that the surface energy, topography, and chemistry are the main factors affecting joint performance. Practical issues, however, are still being caused by variations in the process and contamination risks (e.g., a weak boundary layer). Based on adhesion fundamentals (mechanical interlocking, adsorption/chemical bonding, diffusion, and electrostatics), current reviews emphasize that no single mechanism exists and that the effectiveness of treatments is often proven only phenomenologically. Diffusion in the boundary layer is considered as a fundamental theory and mechanism, yet no research involving diffusion as an adhesion mechanism has been presented or discussed.

In the manufacturing of semifinished products and components from FRPs, on the other hand, the solubility of thermoplastic polymers in the monomers of thermoset systems is well known and has been in commercial use for decades, for example, in the toughness modification of epoxy resin systems with thermoplastics like PES [12,13,14]. Numerous other applications involving interdiffusion and the formation of an IPN between amorphous thermoplastics and thermosetting matrices have been investigated [15]. These include the use of hybrid interlayers for fusion bonding [16], the combined prepreg and infusion technology [17], and the co-curing of thermoplastic films to thermosetting substrates [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Therefore, it seems logical and reasonable to extend and test the application of diffusion-driven IPN formation to adhesive bonding.

1.3. Diffusion-Based Adhesion

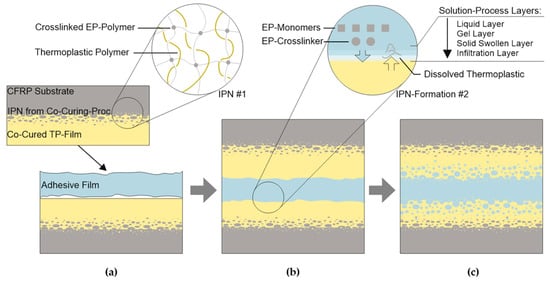

This study investigates whether thermoplastic surfaces can provide inherent and robust adhesion, thereby simplifying subsequent joining processes in aerospace applications. It is also based on the hypothesis that a diffusion-driven formation of an IPN effectively dissolves the boundary layer between the adhesive and the substrate. Drawing parallels to fusion bonding processes, as documented in studies by [16,24] this could significantly reduce the impact of remaining surface contaminations on the mechanical properties of bonded joints. Figure 1 shows the proposed joining process schematically. Two surface-modified adherends, coated with amorphous thermoplastics, are bonded using a film adhesive. The thermoplastic surface films already contain an initial IPN, more specifically called a semi-IPN [25], on the substrate side, typically with a reaction-induced phase separation. During the bonding process (b), as the temperature rises, the viscosity of the adhesive film decreases and the thermoplastic surfaces become sufficiently wetted. If the adhesive and thermoplastic are compatible, interdiffusion and mixing of the materials are possible. The dissolution process is influenced by intrinsic factors such as the constituents and composition of the thermoset systems, molecular weight and distribution, moisture content, synthesis, and the composition of the thermoplastic polymer (e.g., the number of hydroxyl groups) [26]. Examples of extrinsic factors in the bonding process include temperature, pressure, and the increasing crosslinking of the adhesive during the curing process. As miscibility decreases, e.g., due to a higher degree of cure, various types of phase separation can occur. The classifications and general mechanisms are explained in [25,27,28], and specifically for thermoplastic-modified epoxy resins in [29]. A typical sequence of the solution process for thermoplastics like PES in thermosets is shown in the detail of Figure 1b in the form of layers [26,27]. Within the infiltration layer, the dissolving polymer only fills the free volume between the thermoplastic polymer’s molecular chains. As the concentration increases, the mobility of the molecular chains rises (solid swollen area), continuing until the mixture’s glass transition temperature is exceeded (gel layer). Diffusion and movement of the dissolved molecular chains are only possible in the liquid layer. The dissolution and phase separation processes, and the resulting properties, have so far been investigated primarily phenomenologically [21,22,23,30]. Simulations of material and process characteristics require complex modeling, detailed knowledge of the composition, and access to the specific constituents of thermosetting systems for the measurement of specific parameters [31,32,33,34,35]. Current research on bonded joints without interdiffusion and IPN formation covers comprehensive molecular dynamic models to calculate structure–property relationships, and aims to provide the mechanical properties of joints and their failure modes [36,37]. A much broader workflow would be needed for thermoplastic–thermoset interdiffusion joints, where at least the diffusion and dissolution of the adherends surfaces, as well as the formation of micro- and macroscopic morphologies, need to be added. Current research only covers parts of this, like research on the relationship between morphology and tensile strength and toughness [38], the phase separation of small isotropic volumes of epoxy–PES blends [32], or the residual stresses and deformation of toughened and phase-separated matrices [39]. For commercial adhesive systems, such as the FM300 used here, the exact formulation and constituent components are unknown. Accordingly, this study investigates the applicability of the approach with selected parameters from known reference processes and provides an initial characterization of the resulting interfaces and interpenetrating polymer networks (IPNs).

Figure 1.

Proposed bonding process. Starting with two adherends covered with a thermoplastic film connected by an IPN (a); solution of the thermoplastic film and prior surface by the EP adhesive during curing (b); developing a second IPN, leading to adhesive strength independent from surface preparation (c).

The formation of an IPN was studied using reflected light microscopy, height measurements of etched microsections with a laser scanning microscope (LSM), and spectroscopy via energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX). The mechanical performance and quality of the bonds were investigated using tensile shear and mode-1 energy release rates. For this purpose, carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) samples with potentially suitable thermoplastic surfaces, PES and PEI, as well as a series of reference samples without a thermoplastic surface were produced. Before bonding the samples, various surface pretreatments were applied, ranging from nearly no preparation (only dry wiping of the cooling water during sample cutting) to a standard method (wet grinding). In addition, a further series of tensile shear specimens were hot-/wet-conditioned and tested.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Materials and Method for Surface Modification

As outlined before, thermosetting CFRPs with a thermoplastic surface had to be manufactured and bonded. In principle, the thermoplastic surface layer can be applied in a co-curing process [40]. The thermoplastic film can be placed as the first or last remaining layer on the dry (infusion process) or pre-impregnated fibers (prepreg process) and consolidated with these [17,18,41,42]. Another method, albeit more complex, is the use of a hybrid interlayer, partially impregnated over the thickness with a thermoplastic polymer [16]. A hybrid interlayer connects the two materials, the thermoplastic film and the thermosetting matrix, mechanically via the joint impregnation of one layer, e.g., a woven fabric. More common is the connection via the formation of an interphase region, the very mechanism that is to be investigated here for the interface of the adhesive to the substrates. However, surface treatment can also be used. The authors of [42] and [43] used films made of PVDF, which were treated with an atmospheric pressure plasma and that produced very good mechanical characteristics. The film can be applied either locally to certain parts of the surface [42,43] or globally across the entire surface. In this study, the components were covered globally.

The selection of thermoplastic materials was guided by the current understanding of their potential suitability for the use case and their ability to form interphases with epoxy thermosetting resins. PES is known for its excellent mechanical properties, high solubility, strong adhesion capabilities, and a long history of research in the context of epoxy toughening [12,22,26,31,35,44,45]. For this study, PES (Lite S) and PEI (Lite I) films (Waidhofen an der Ybbs, Austria), both with a thickness of 50 µm and supplied by Lite GmbH, were used. Another thermoplastic material was also used: a PEI powder supplied by Goodfellow. The powder was sieved to the main delivered gradation, a particle size between 250 µm and 355 µm. Both thermoplastic materials have strong mechanical properties and high-temperature applicability, but can also absorb certain media such as isopropanol, kerosene, hydraulic oil, or water, and are, in this respect, less performant than semi-crystalline high-performance polymers such as PEEK. However, the materials are only present here as a thin, embedded film, enclosed and partially penetrated by a highly resistant epoxy matrix. Bruckbauer [46] studied the properties of CFRP/TP-Film/CFRP specimens that used both PES and PEI as a film material. He found that the energy release rates (G1C) of specimens after 1000 h of storage increased significantly, mainly due to the higher ductility of the conditioned thermoplastics. The tensile shear strengths were only slightly reduced.

The test specimens for the tensile shear and mode-1 peel tests were manufactured using the unidirectional Prepreg M21E(Stamford, CT, USA) from Hexcel. FM300K (Syensqo, Brussels, Belgium) adhesive was used for the bonding process. The HexFlow RTM6(Stamford, CT, USA) from Hexcel was used as a further thermosetting resin system together with PEI as film material. Test specimens made from this material pairing were used as a reference in the investigations on the formation of interphases between the adhesive system and the thermoplastic.

2.2. Procedures for Inspection of Interphase Formation

Besides the initial compatibility of the resin systems, the parameters of the curing process of the thermosetting resin system play a key role in the development of an interphase. Bruckbauer [46] provides detailed descriptions for PEI and PES with the epoxy resin-based matrix systems Hexcel M18/1 and Hex Flow RTM6. No descriptions of interphase formation are known for the material pairing of structurally adhesive and amorphous thermoplastics. The experiments conducted are therefore initially aimed at providing evidence and a preliminary analysis of the size of an interphase. Thermoplastic films with a size of 25.4 mm × 25.4 mm were cut as samples for the investigation of the interphase. These samples were covered on both sides with one layer of film adhesive. Reference sample PEI films were placed in preheated (80 °C) RTM6. All samples were then cured using a constant heating rate of 3 K/min up to 180 °C. They were held at this temperature for 60 min and then cooled at a rate of 3 K/min.

Microsections of the symmetrical interface were prepared for inspection. An initial analysis was conducted using an optical microscope VHX-1000 (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Some of the polished samples were treated (etched) with dichloromethane (DCM) for 3 s. This solvent dissolves the thermoplastic parts of the surface and the structures of the interphase become visible. The thermoset matrix is largely resistant to DCM. The intensity of local material loss is seen as a measure of the soluble, local thermoplastic volume content. To analyze the material removal, height profiles of the sample surfaces were measured using a laser scanning microscope VK-X 1000 (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). For further quantitative investigation of the propagation of the interphase formation, specimens from parts of the tensile shear test series were coated with 4.5 nm platinum and analyzed with SEM and EDX (see the “Evaluation of Shear Strength” section for the production and pretreatment of the test specimens). For both analyses a dual-beam Helios G4 CX (Hillsboro, OR, USA) system from FEI with an acceleration voltage of 15 kV was used.

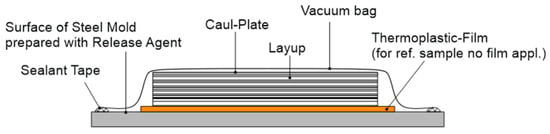

2.3. Sample Preparation and Procedures for SLS

SLS tests were conducted to provide an initial assessment of the static mechanical performance of the proposed method. The test specimens were manufactured and tested in accordance with the ASTM D 5868 standard [47] on a universal testing machine, the “Zwick 1484” (ZwickRoell GmbH, Ulm, Germany). Three CFRP panels were produced from 9 plies, , of unidirectional Hexcel M21/35%/268/T800S prepreg. The film adhesive FM300K with an areal weight of 244 g/m2 was used for bonding. The CFRP sheets were manufactured with a prepreg open-mold process on a freshly prepared steel mold. The 2-stage Zywax Waterworks system (Chem-Trend L.P., Howell, MI, USA) was used as release agent. Each specimen consists of two adherends with a length of 130 mm, a width of 25.4 mm, and bonded with a 25.4 mm overlap. The samples with a thermoplastic surface were manufactured as illustrated in Figure 2; no TP film was used for the reference samples. Table 1 lists the ‘surface modification’, ‘surface preparation’, and ‘conditioning’ factors, along with the levels at which they were tested. A total of 18 combinations were tested.

Figure 2.

Manufacturing setup of SLS specimens.

Table 1.

Factors and levels of shear strength test campaign, with a total of 18 different series.

The surface preparations were performed as follows:

- Dry wiping: Before bonding, the sample batches of a set had to be cut out of a larger panel using a water-cooled circular saw. During sawing, the samples became wet due to the cooling water. The samples were simply dried with a cotton wipe; no further cleaning took place.

- Wet wiping with isopropyl alcohol: Before bonding, the samples were first dried with a cotton wipe. The samples were then wiped twice over their entire surface with a wipe soaked in isopropyl alcohol

- Surface roughening by sanding: The samples were first wiped dry and then wiped with isopropyl alcohol. The surfaces were then manually sanded with an abrasive fleece (scotch brite red/very fine) and cleaned with de-ionized water, and finally wiped dry.

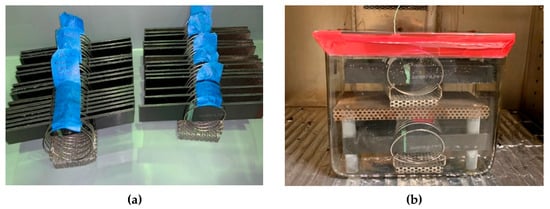

After the specific surface preparation, each set was bonded with two layers of FM300K. Curing in a press was performed at 6 bars, heated with 3 K/min to 175 °C, and held for 1 h. After cooling, the specimens were cut from the panels using a water-cooled circular saw. The samples were then conditioned (see Figure 3). Each of the 18 different sets consists of at least three specimens. The sets without immersion in water have a batch size of 4.

Figure 3.

(a) Dry- and (b) wet-conditioning of SLS specimens.

2.4. Sample Preparation and Procedures for Mode-I Fracture Toughness Testing

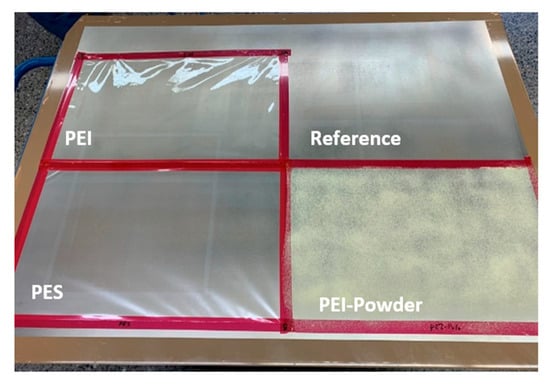

The tests were performed in accordance with DIN EN 6033 [48]. The specimens were made from unidirectional, 11-ply laminates () of M21E/34%/UD134/IMA-12K, using the same open-mold autoclave process as for the SLS specimens, and bonded with a single layer of FM300K weighing 244 g/m2. They had a final length of 250 mm and a width of 25 mm. The tests were performed using a Zwick Z005(ZwickRoell GmbH, Ulm, Germany) universal testing machine with a loading rate of 10 mm/min and a pre-crack length of between 10 and 15 mm. The surfaces were modified as previously, with 50 µm of PEI and PES films, as well as a reference without thermoplastic surface. The films were placed as the first ply on the mold side. It can therefore be assumed that the surfaces were contaminated with release agent residues, although these were not quantified in the study. From the manufacturing perspective, especially for coupon elements, the release would not be necessary. However, the industrial production of larger components was anticipated here. In these processes, contamination from prepared mold tool surfaces would be very likely occur without additional surface pretreatment. In addition, another panel was manufactured with a sieved powder of PEI. The powder was spread manually over a defined area as evenly as possible, with the overall applied mass corresponding to a film with a thickness of 75 µm. The powder was used as a test for a simplified application of the thermoplastic surface. Figure 4 shows the mold before placing the CF plies, with a reference surface at the top right.

Figure 4.

Surface modifications on the mold prior to laying the CF plies.

The CFRP panels were trimmed using a water-cooled circular saw, which caused the surfaces to become partially wetted with water and cut particles from the matrix and fibers. As before, all samples were at least dried using a cotton cloth before bonding. The two factors “surface modification” and “surface preparation”, along with the tested levels, are summarized in Table 2. Each of the 8 different series consists of 5 specimens.

Table 2.

Factors and levels of the mode-1 fracture tests; full factorial testing with 5 specimens for each of the 8 sets.

The surface preparations were performed as follows:

- Dry wiping: All samples were dried with a cotton cloth following the same procedure as for the SLS tests; no further cleaning was performed.

- Surface roughening by sanding: The sanding process was more complex compared to the SLS tests. A three-stage wet-sanding process was carried out with 120, 150, and 240 grit sandpaper, followed by cleaning with de-ionized water and isopropyl alcohol. The surface condition was checked with a water break test and the panels were re-dried at 100 °C for 1 h.

After surface preparation, the panels were bonded in a press with a heating rate of 3.6 K/min to 180 °C and a holding time of 1 h. The initial delamination was introduced via a layer of release film. The specimens were cut using a water-cooled circular saw.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interphase Formation

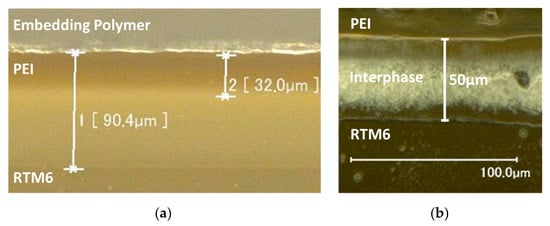

For the reference material pairing PEI/RTM6, the formation of an interphase could be detected by reflected light microscopy for both untreated and etched (DCM) microsections (see Figure 5). The remaining width of the neat film is less than 30 µm. The expected diffusion zone has a width of at least 50 µm. This is particularly evident in the etched sample. The morphology is very continuous (see height map in Figure 6a).

Figure 5.

PEI/RTM6 reference sample for interphase formation and inspection: (a) polished microsection in reflected light microscopy; (b) etched microsection with reflected light microscopy from (a) highlights the interphase between PEI and RTM6.

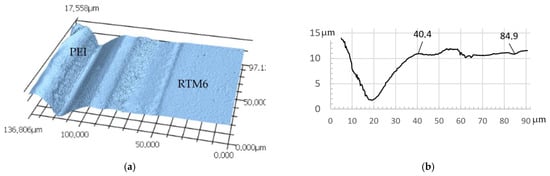

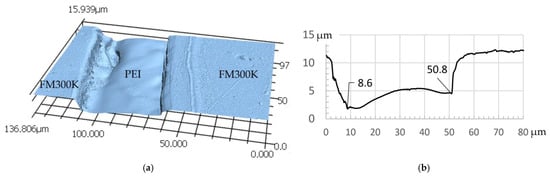

Figure 6.

Reference sample cured with 5 K/min: (a) height map of etched sample measured by LSM, with PEI on the left side and RTM6 on the right side; (b) height profile section of etched PEI/RTM6 sample.

From the height map, a section can be plotted in a diagram (see Figure 6b). The film used had a thickness of 50 µm, but most of the material removal was limited to a width of roughly 20 µm. Some removal can also be observed over a zone of 80–85 µm, thus far beyond the TP film used. In addition to the intensity of the dissolution, the distance of the removal is therefore also considered an indication of interphase formation. Two effects can be observed here:

- The diffused thermoset can partially fixate the thermoplastic polymer, i.e., make dissolution in DCM more difficult;

- Thermoplastic phases can be found and also dissolved by DCM beyond the previously placed film. The phase separation that occurs during curing is thought to have a significant influence on this.

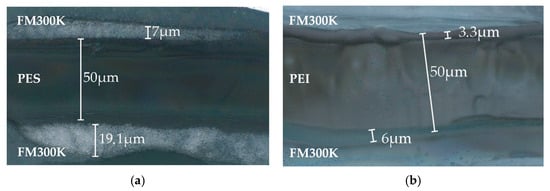

The same method as for the reference sample has been applied to symmetrical samples made of FM300K/PES/FM300K and FM300K/PEI/FM300K. For PES, the interphase formation was clearly visible in the etched sample with reflected light microscopy, though the morphology is less continuous as in the reference sample. For PEI, the boundary regions were very small compared to the former samples. No comparable morphology is visible in either (see Figure 7a,b).

Figure 7.

Reflected light microscopy of etched samples, both cured with 3 K/min: (a) FM300K/PES/FM300K and (b) FM300K/PEI/FM300K.

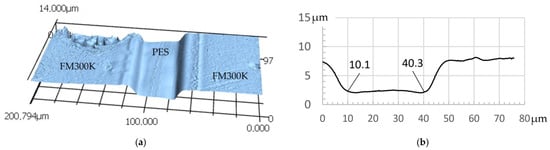

The measurement data for the height profile measurements confirm the expectations regarding the formation of interphases between PES/FM300K and PEI/FM300K. For PES, the material removal by the solvent is constant over a width of approx. 30 µm and decreases again over a range of 10 µm towards the edges. It is therefore assumed that the width of the interphase is at least 10 µm (see Figure 8). These effects cannot be clearly observed in the PEI samples. The flanks or edges of the TP film fall off much more steeply compared to the other two samples. The area with approximately uniform removal has a width of at least 40 µm. It is therefore assumed that the diffusion zone is significantly smaller (see Figure 9a,b).

Figure 8.

Symmetrical sample FM300K/PES/FM300K cured with 3 K/min: (a) height map of etched sample measured by LSM; (b) height profile section with an approximately 30 µm wide etched “valley”, likely consisting of pure PES film.

Figure 9.

Symmetrical sample FM300K/PEI/FM300K cured with 3 K/min: (a) height map of etched sample measured by LSM; (b) height profile section with an at least 40 µm wide etched “valley”, likely consisting of pure PEI film.

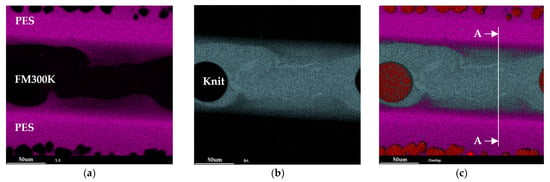

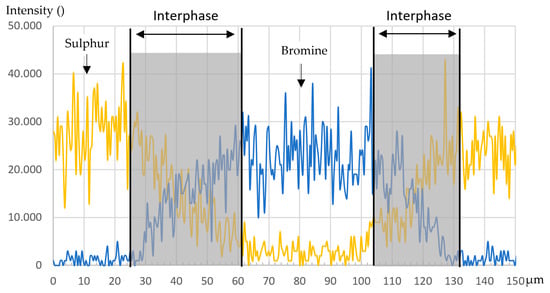

Further analyses regarding the presence and characteristics of interphases were carried out using SEM and EDX. Because samples from the SLS test campaign were used, the structure of the samples differs from the previous structure. Here, the adhesive film is surrounded by two thermoplastic films (PEI and PES). Previously, one thermoplastic film was surrounded by two adhesive films.

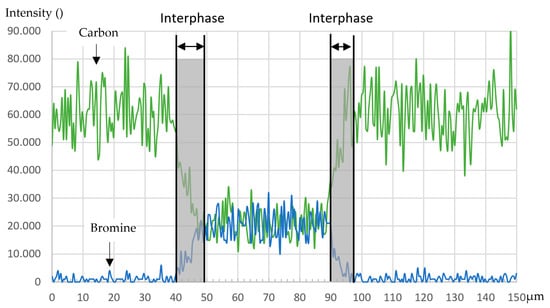

For the material pairing of PES/FM300K/PES, see Figure 10. The diffusion of sulfur, which can be used as exclusive marker for PES, into the adhesive is not uniform but rather largely continuous. The distribution of bromine, on the other hand, is more constant in the PES-dominated areas. With regard to the adhesive, the non-uniform structure must be mentioned. The knit material present, which can be seen as a round black spot in Figure 10, certainly changes the local parameters in the curing and dissolution process. Furthermore, bromine does not appear to be evenly distributed in the adhesive. Regions with higher and lower concentrations are clearly visible. In Figure 11, the intensity of sulfur and bromine in cross-section A-A is shown. The transition between the two materials is smooth and there is a pronounced diffusion zone with a width of 30 to 35 µm. The indications from the light microscopy and the measurement of samples treated with DCM can be confirmed, even if the diffusion zone is much larger than expected.

Figure 10.

EDX analysis of a polished, non-etched cross-section of a PES/FM300K/PES sample showing the intensity map: (a) sulfur, (b) bromine, and (c) an overall view of sulfur, bromine, and carbon.

Figure 11.

Intensity distribution of sulfur and bromine in cross-section A-A.

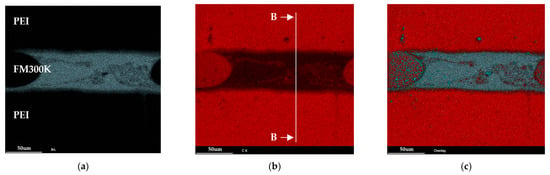

No exclusive marker is available for the thermoplastic in the PEI/FM300K sample. Instead, the carbon content can be used as a marker for the PEI and bromine for the adhesive (see Figure 12). The transition between the two materials is significantly smaller compared to the reference sample with RTM6 and the PES/FM300K sample. Therefore, the indications from the optical microscopy and etched samples measured in the LSM can be confirmed. The EDX results indicate a minimal interphase with an extension of between 5 µm and 10 µm (see Figure 13). As with the PES/FM300K sample, the bromine distribution in the edge regions is continuous.

Figure 12.

EDX analysis of a polished, non-etched cross-section of a PEI/FM300K/PEI sample showing the intensity map: (a) bromine, (b) carbon, and (c) an overall view of bromine, carbon, and oxygen.

Figure 13.

Intensity distribution of carbon and bromine in cross-section B-B.

3.2. Shear Strength

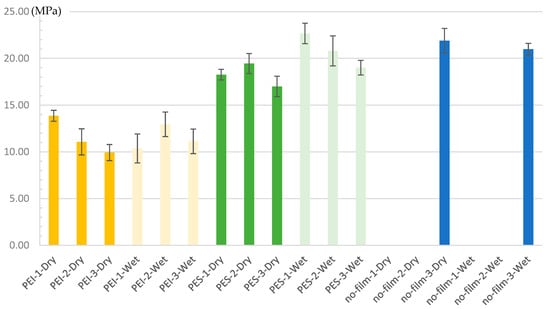

As explained in Section 2.2, 18 series were tested, with a batch size of four (dry) and three (hot–wet) samples, see Figure 14 for the results. Although the series for the reference samples were manufactured, they did not provide any results for surface preparation levels “1” and “2” (dry and wet wiping). The panels fell apart either upon removal from the press or when cut with a circular saw. No adhesion was found between a standard matrix material and a standard adhesive without the usual surface preparation (see Figure 15e). The characteristic values for the ‘sanding’ treatment, on the other hand, are at the expected performance level.

Figure 14.

Single-lap shear strength with standard deviation; Set-Name = “Surface Modification”—“Surface Preparation”—“Conditioning”.

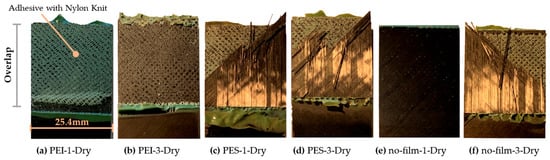

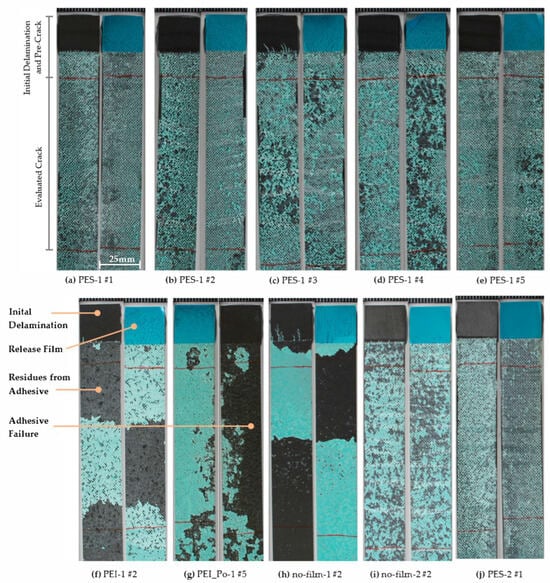

Figure 15.

Selected fracture surfaces of the SLS tests from specimens with surface preparation “1” (dry wiping) and specimens with surface preparation “3” (sanding); all samples’ widths are 25.4 mm.

Remarkably, significant shear strength was demonstrated in all specimens with modified surfaces. The PEI series are at a minimum of approximately 50% of the reference samples with sanding. The drop in PEI strength with increasing ‘quality’ of surface pretreatment is unclear, particularly given that the PEI wet samples show a different trend. A greater statistical influence is assumed due to the small number of samples. Regarding the conditioning, a reduction in strength values due to immersion in water was assumed (see [46]). One hypothesis for the observed increase, at least in the case of PES, is that the storage period was insufficient. Consequently, the outer regions in particular may have absorbed moisture, becoming more ductile and reducing the impact of typical stress peaks. PES series exhibit a higher level of shear strength, especially compared to PEI. This correlates with the characteristics of the interphases and is therefore in line with current expectations. It is also interesting that the almost untreated samples show the lowest variance in the sets for both PEI and PES, although this is not exactly ‘significant’ given the number of samples. In summary, the results clearly motivate further investigation.

The fracture surfaces (see Figure 15) show a quite surprising qualitative difference between the modification with PES and PEI. In all samples of PES and sanded CFRP, failure occurred in the substrate, presumably triggered quite early by the 45–first-ply. In contrast, the PEI samples exhibited a fracture in the adhesive near the interface with the substrate, with some residues on both surfaces. The reference sample (CFRP) without surface preparation (Figure 15e) resulted in the complete failure of the adhesive bond, as can be clearly seen from the black surface without adhesive residues. The G1C test series was then carried out to specifically investigate adhesion and the consistency of failure.

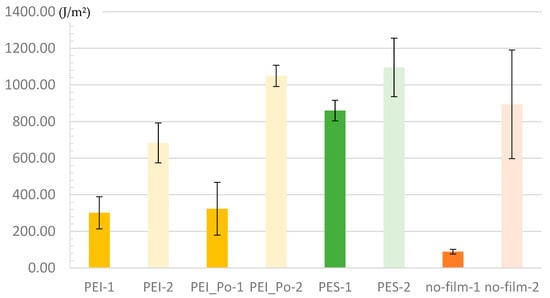

3.3. Fracture Toughness

As expected, the reference series (‘no-film-1’) shows that poor bond quality is caused by a lack of adhesion mechanism on untreated surfaces that are presumably contaminated with a release agent (see Figure 16 and Figure 17). The failure of the samples is clearly adhesive, with nearly no adhesive residue left on the surfaces after the peel. Unlike the samples from the shear strength tests, the test specimens could still be tested and did not fall apart. The main difference between the two sets is the resin systems used: M21 for SLS and M21E for G1C. From a technical point of view, however, the G1C values measured are irrelevant. A typical performance was achieved for properly surface-treated reference samples, albeit with a fairly high degree of variance. The preparation process was carried out manually. Automated surface processes, e.g., plasma treatment, should be considered for further tests.

Figure 16.

Results of mode-1 fracture toughness tests with standard deviation; Set-Name = “Surface Modification”—“Surface Preparation”.

Figure 17.

Fracture surfaces of mode-1 test specimens. Upper row: all specimens in corresponding pairs of the PES-1 series with minimal surface preparation and predominantly cohesive failure. Lower row: selected samples in corresponding pairs representative of the remaining series. All samples’ widths are 25 mm.

The results of the thermoplastic-coated samples indicate a correlation between the strength and the interphase characteristics; see also the PEI and PES shear strength tests. Tests of the untreated PES specimens show the lowest variance and lead to a slightly lower characteristic value than the treated CFRP specimens. In [49], fracture toughness values in mode-1 were determined for bonded samples containing various contaminants, including the controlled application of release agents to the surface. The G1C values for release agents dropped by more than 50%. Methods and results from several comprehensive studies on the influence of contamination are presented in [2]. Samples contaminated with release agents were first cleaned and sanded, and then contaminated by immersion in a silicone-containing solution of Frekote 700 NC in heptane. As the contamination increased, the G1C values also fell to approximately 60% of the reference value. However, at low concentrations of 3.2–5.1% Si on the surface, an average fracture toughness of 80% of that of the reference could still be achieved, albeit with significant variance. Furthermore, all contaminated samples exhibited adhesive failure. By contrast, it should be noted that the variance of the PES sets is small in the results presented here, and the fracture toughness of the unprepared surface is, on average, 96% of that of the reference sample. Significant improvements were observed in all thermoplastic surfaces when surface preparation (sanding) was carried out.

Finally, the fracture surfaces of the test specimens can be used to evaluate the failure (see Figure 17). The green-colored adhesive can be clearly distinguished from the black CFRP. As can be seen here, PES consistently leads to cohesive failure in the adhesive. In contrast, almost untreated PEI and PEI-Po samples show a predominantly adhesive, partially cohesive failure, which changes to a cohesive failure with surface pretreatment. In summary, this confirms the trend that, at least for the adhesive FM300K, PES is the more suitable candidate for modifying the surface.

4. Conclusions

This study explores the potential of using thermoplastic surfaces in FRPs to improve structural bonding by eliminating the need for extensive surface preparation—until now, a critical requirement for state-of-the-art bonding processes in aerospace applications. The experimental results demonstrate that PES surfaces provide high mechanical performance and the preferred failure mode, even without surface treatment. PEI surfaces showed lower performance levels. However, compared to the non-prepared reference samples, there is still a huge advantage with thermoplastic surfaces. The investigation of the interphase formation between thermoplastic surfaces and epoxy adhesives revealed that PES/FM300 forms a consistent and wide interphase. This indicates a strong connection to the adhesive, which might be the main reason for its superior performance.

The findings imply that thermoplastic surfaces, such as PES, could simplify the bonding process and potentially reduce production costs and risks associated with surface preparation. However, there are still many challenges to overcome. The influence of untreated surfaces and potential contamination, although less pronounced than reported in the literature, still needs to be investigated. Future studies should focus on type and quantity of contamination and explore aging mechanisms to ensure the durability and reliability of these joints. They should also consider the short- and long-term environmental effects and exposure to certain media depending on the type of application.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Omid Zarmandili for conducting numerous experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Da Silva, L.F.M.; Öchsner, A.; Adams, R. (Eds.) Handbook of Adhesion Technology, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9783319554105. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti, W.L.; Brune, K.; Noeske, M.; Tserpes, K.; Ostachowicz, W.M.; Schlag, M. (Eds.) Adhesive Bonding of Aircraft Composite Structures: Non-Destructive Testing and Quality Assurance Concepts; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-319-92809-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid Fuertes, T.A.; Kruse, T.; Körwien, T.; Geistbeck, M. Bonding of CFRP primary aerospace structures–discussion of the certification boundary conditions and related technology fields addressing the needs for development. Compos. Interfaces 2015, 22, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blass, D.; Dilger, K. CFRP-Part Quality as the Result of Release Agent Application–Demoldability, Contamination Level, Bondability. Procedia CIRP 2017, 66, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.M.; Waghorne, R.M. Surface pretreatment of carbon fibre-reinforced composites for adhesive bonding. Composites 1982, 13, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, N.; Oakley, B.R.; Belcher, M.A.; Blohowiak, K.Y.; Dillingham, R.G.; Abenojar, J.; Martínez, M.A. Surface modification of aircraft used composites for adhesive bonding. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2014, 50, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Sinke, J.; Benedictus, R. Surface modification of PEEK by UV irradiation for direct co-curing with carbon fibre reinforced epoxy prepregs. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 73, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudhanto, A.; Alfano, M.; Lubineau, G. Surface preparation strategies in secondary bonded thermoset-based composite materials: A review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 147, 106443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Jin, X.; Luo, Q.; Li, Q.; Sun, G. Adhesively bonded joints–A review on design, manufacturing, experiments, modeling and challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 276, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xue, Y.; Dong, X.; Fan, Y.; Hao, H.; Wang, X. Review of the surface treatment process for the adhesive matrix of composite materials. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2023, 126, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatappagari, S.; Mutra, R.R.; Mallikarjuna Reddy, D. State-of-the-art in adhesive joint technology: A comprehensive review of recent progress. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 2593–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaranpillai, J.; Hameed, N.; Pionteck, J.; Woo, E.M. (Eds.) Handbook of Epoxy Blends; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 9783319400419. [Google Scholar]

- Solvay Specialty Polymers. Virantage PESU: Tougheners for Thermoset Matrix Systems. 2016. Available online: https://www.solvay.com/sites/g/files/srpend616/files/2018-07/virantage-pesu-tougheners-for-thermoset-matrix-systems-en.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Paris, C. Étude et Modélisation de la Polymérisation Dynamique de Composites à Matrice Thermodurcissable. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse, Toulouse, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Djukic, L.; Paton, R.; Ye, L. Thermoplastic–epoxy interactions and their potential applications in joining composite structures–A review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 68, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageorges, C.; Ye, L. Fusion Bonding of Polymer Composites; Springer: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-4471-1087-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaps, R. Kombinierte Prepreg- und Infusionstechnologie für Integrale Faserverbundstrukturen; Zugl.: Braunschweig, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckbauer, P. MAIfo-Entwicklung Einer Prozesskette zur Herstellung von Teilfolierten Faserverbundbauteilen: Abschlussbericht: Berichtszeitraum: 01.05.2013–30.04.2016; TUM-Lehrstuhl für Carbon Composites: Garching, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, I.F.; van Moorleghem, R. Ultrasonic welding of carbon/epoxy and carbon/PEEK composites through a PEI thermoplastic coupling layer. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 109, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauner, C.; Nakouzi, S.; Zweifel, L.; Tresch, J. Co-curing behaviour of thermoset composites with a thermoplastic boundary layer for welding purposes. Adv. Compos. Lett. 2020, 29, 2633366X2090277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandi, L.-J. Understanding the Co-Cured Epoxy/Thermoplastic Interface in Thermoset Composite Welding (TCW). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taubert, M.; Diez, J.G.; Musil, B.; Höfer, P. Comparing interphase formation in different thermoplastics combined with RTM6/M18 epoxy systems. Adv. Manuf. Polym. Compos. Sci. 2025, 11, 2482280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, M. Mechanical Properties of Thermoplastic/Thermoset Interphases. Masterarbeit; Katholische Universität Louvain: Louvain, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meer, T.; Geistbeck, M. Automatisiertes Schweißen von thermoplastischen Verbindungselementen auf CFK. Light. Des. 2017, 10, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, L.H. Interpenetrating Polymer Networks: An Overview. In Interpenetrating Polymer Networks; Klempner, D., Sperling, L.H., Utracki, L.A., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 3–38. ISBN 9780841225282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.L.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z.Y.; Zhu, S.; Yu, M.H. Dissolution behaviour of polyethersulfone in diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A epoxy resins. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 213, 12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueberreiter, K. The solution process. In Diffusion in Polymers; Academic Press: London, UK, 1968; pp. 220–257. [Google Scholar]

- Robeson, L.M. Polymer Blends: A Comprehensive Review, 1st ed.; Hanser: Munich, Germany, 2007; ISBN 9783446436503. [Google Scholar]

- Tercjak, A. Phase separation and morphology development in thermoplastic-modified thermosets. In Thermosets; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 147–171. ISBN 9780081010211. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckbauer, P. Polyetherimid-Epoxidharz Interphasen zur Anbindung von Funktionsschichten auf Faserverbundwerkstoffen. Z. Für Kunststofftechnik 2017, 1, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dumont, D.; Seveno, D.; de Coninck, J.; Bailly, C.; Devaux, J.; Daoust, D. Interdiffusion of thermoplastics and epoxy resin precursors: Investigations using experimental and molecular dynamics methods. Polym. Int. 2012, 61, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J.; Oh, C.-B.; Won, J.S.; Lee, H.I.; Lee, M.Y.; Kwon, S.H.; Lee, S.G.; Park, H.; Seong, D.G.; Jeong, J.; et al. Development of high-toughness aerospace composites through polyethersulfone composition optimization and mass production applicability evaluation. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 189, 108590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.H.; Kang, H.; Kim, B.-J.; Lee, H.I.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.G. Addressing diffusion behavior and impact in an epoxy-amine cure system using molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, I.; Sugizaki, T.; Akasaka, S.; Asai, S. Quantitative analysis of the phase-separated structure and mechanical properties of acrylic copolymer/epoxy thermosetting resin composites. Polym. J. 2015, 47, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosetti, Y.; Alcouffe, P.; Pascault, J.-P.; Gérard, J.-F.; Lortie, F. Polyether Sulfone-Based Epoxy Toughening: From Micro- to Nano-Phase Separation via PES End-Chain Modification and Process Engineering. Materials 2018, 11, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, J.; Meißner, R.H.; Bitzek, E.; Zahn, D. A Molecular Simulation Approach to Bond Reorganization in Epoxy Resins: From Curing to Deformation and Fracture. ACS Polym. Au 2021, 1, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dötschel, V.; Richter, E.M.; Possart, G.; Steinmann, P.; Ries, M. Reactive coarse-grained MD models to capture interphase formation in epoxy-based structural adhesive joints. Eur. J. Mech. -A/Solids 2025, 116, 105801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wu, Q.; Morgan, S.E.; Wiggins, J.S. Morphologies and mechanical properties of polyethersulfone modified epoxy blends through multifunctional epoxy composition. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinugawa, Y.; Kawagoe, Y.; Shirasu, K.; Ryuzono, K.; Okabe, T. Multiscale modeling of residual deformation in CFRP with reaction-induced phase separation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 306, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutis, C.; Hodzic, A.; Beaumont, P.W.R. (Eds.) Structural Integrity and Durability of Advanced Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9780081001370. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, M. Thermoplastic Adhesive for Thermosetting Composites. MSF 2012, 706–709, 2968–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbel, T. The Hybrid Bondline: A Novel Disbond-Stopping Design for Adhesively Bonded Composite Joints. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schollerer, M.J. Steigerung der Robustheit von Strukturellen Verklebungen in der Luftfahrt Mittels Lokaler Oberflächenzähmodifikation. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Tusiime, R.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhang, H. Simultaneously improving mode I and mode II fracture toughness of the carbon fiber/epoxy composite laminates via interleaved with uniformly aligned PES fiber webs. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 129, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Velthem, P.; Ballout, W.; Daoust, D.; Sclavons, M.; Cordenier, F.; Henry, E.; Dumont, D.; Destoop, V.; Pardoen, T.; Bailly, C. Influence of thermoplastic diffusion on morphology gradient and on delamination toughness of RTM-manufactured composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 72, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckbauer, P. Struktur-Eingenschafts-Beziehungen von Interphasen zwischen Epoxidharz und thermoplastischen Funktionsschichten für Faserverbundwerkstoffe; Verlag Dr. Hut: München, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9783843938945. [Google Scholar]

- D14 Committee. Test Method for Lap Shear Adhesion for Fiber Reinforced Plastic (FRP) Bonding; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN 6033:2016-02; Luft- und Raumfahrt_-Kohlenstofffaserverstärkte Kunststoffe_-Prüfverfahren_-Bestimmung der Interlaminaren Energiefreisetzungsrate_-Mode_I_- GIC. Deutsche und Englische Fassung EN_6033:2015. DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany.

- Markatos, D.N.; Tserpes, K.I.; Rau, E.; Markus, S.; Ehrhart, B.; Pantelakis, S. The effects of manufacturing-induced and in-service related bonding quality reduction on the mode-I fracture toughness of composite bonded joints for aeronautical use. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 45, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).