Abstract

The study proposes a methodology that combines digital image correlation (DIC) with cluster analysis (CA) to investigate the damage evolution and localization behavior of basalt fiber foam concrete (BFFC) under tensile loading. This method can simultaneously conduct quantitative analysis of both the process of damage accumulation and the process of damage localization. Quasi-static tensile tests were performed on specimens with different matrix densities and basalt fiber content. The full-field and full-process deformation images of the specimens were recorded by a high-resolution CCD. Cluster analysis was performed on the precise deformation data obtained from the DIC method, and damage extent factors and damage localization coefficients were defined. Statistical analysis indicates that the incorporation of basalt fibers not only effectively delays the progression of damage in foam concrete materials but also significantly enhances their initial damage threshold load and inhibits the phenomenon of damage localization in foam concrete. Compared to specimens without basalt fibers, those incorporating basalt fibers exhibited increases in the damage localization coefficients at tensile failure of 0.4, 0.33 and 0.18, respectively, under three different matrix density conditions. Therefore, the proposed DIC-CA method, in conjunction with the defined damage extent factor and damage localization coefficient, can effectively and quantitatively capture the two key dimensions of damage (accumulation extent and spatial distribution characteristics) in fiber-reinforced foam concrete under tensile loading. This provides an efficient, intuitive, quantitative analysis method for characterizing the initiation, development and localization processes of damage in similar materials.

1. Introduction

As a new type of building material, foam concrete (FC) has good thermal and acoustic insulation properties due to its high porous structure [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In addition, foam concrete demonstrates excellent controllability of strength, which is achieved by precisely regulating its density. This direct correlation between strength and density enhances the flexibility of material design and ensures the best possible mechanical properties and structural stability in different application scenarios [8,9,10,11]. This enables FC to adapt flexibly to diverse environmental conditions and working demands. However, despite the many advantages of FC, its low compressive strength and significant brittleness characteristics have limited its application and widespread use [12,13,14,15,16].

FC is a typical brittle material that exhibits difficulty in undergoing significant plastic deformation when subjected to force. Its stress–strain curve typically experiences a rapid decline after reaching the peak, indicating low energy dissipation capacity. Domestic and international scholars have found that the study of the physical and mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced concrete materials under different environmental conditions has become a popular research topic. Fernandes et al. [17] studied the microstructure of thermally damaged concrete from real-scale reinforced concrete columns using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and x-ray diffraction (XRD). Manica et al. [18] studied the influence of age and internal moisture on the performance of reinforced concrete walls at high temperatures. In FC, fibers can act as crack bridges and prevent further crack propagation [19]. Consequently, fiber reinforcement is frequently employed to enhance foam concrete’s tensile properties [20]. It was reported that the addition of steel fibers improved the compressive and flexural strengths, and increased the ductility of lightweight concrete [21]. The addition of polypropylene (PP) fibers has been shown to increase the splitting tensile and flexural strength of foam concrete by 44% and 40%, respectively [22]. Amran et al. [23] also found that the inclusion of polypropylene fiber and silica fume enhanced the strengths of foamed concrete to levels 20–50% greater than those of the corresponding reference concrete at the specified volume of foam. Meanwhile, an increase in the tensile strength was seen at increased compressive strength. In addition to polypropylene (PP) fibers, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers also enhance the tensile behavior of foam concrete. This improvement can be attributed to their high modulus and strength, cost-effectiveness [24], and strong adhesion to the cement matrix [25]. These factors collectively confirm the advantages of incorporating PVA fibers in foam concrete applications. It has been reported that adding 0.3% (by volume) of PVA fibers can increase the splitting and bending strength of foam concrete by 27% and 76%, respectively [26]. The numerous studies mentioned above practiced the use of various supplementary cementing materials (SCM) and fibers in foam concrete. Above studies demonstrate that the incorporation of an appropriate number of fibers (such as polypropylene, steel, glass, and carbon fibers) into foam concrete can significantly enhance its mechanical properties. Fibers function as ‘microtendons’ during the hardening process, bridging pores and microcracks, which establishes an effective mechanism for bridging and pull-out [27]. This action delays crack propagation and improves the material’s ductility and toughness. Nevertheless, studies have shown that fiber-reinforced foam concrete incorporating natural fibers, steel fibers, or polymer-based fibers is susceptible to durability issues [28], low corrosion resistance [29], and inadequate heat resistance [30]. In contrast, artificially produced ceramic fibers, such as basalt fibers, exhibit superior corrosion and temperature resistance compared to their steel, polymer-based, and natural counterparts. Osman et al. [31] found that the incorporation of basalt fibers significantly influenced the pore network of the fiber slurry, thereby enhancing its strength. Notably, the flexural strength increased by approximately 88% when the basalt fiber content was raised from 0% to 3%. The high strength and excellent thermal stability of basalt fibers have contributed to their growing application in engineering.

Although the incorporation of fibers can form a bridging link at the crack surface, which effectively delays crack propagation and improves the post-peak bearing capacity of the material, the bridging effect often exhibits spatial inhomogeneity in practical engineering applications. When fiber strength is insufficient or their distribution is non-uniform, localized fibers rupture or pull-out may occur, accelerating microcrack propagation and leading to microcrack cluster formation. FC typically comprises a substantial number of both closed-cell and open-cell structures. These pores are susceptible to becoming zones of stress concentration when subjected to external loading, which can subsequently result in the formation of microcracks. Due to the randomness of pore distribution, damage inside the structure tends to be localized rather than uniformly distributed. Additionally, the heterogeneous spatial distribution of cement paste, pores, admixtures, and fibers results in a multi-scale, multiphase discontinuous internal structure. This inherent material heterogeneity increases the susceptibility of certain regions to premature failure under load, thereby promoting damage localization. In the study of damage localization in fiber-reinforced foamed concrete, quantifying the damage and localization behavior is crucial for understanding the damage mechanism and optimizing the design. Regarding the issues, relevant literature has investigated strain localization in fiber-reinforced composites using digital Image correlation and acoustic emission techniques, a description of carbon fiber reinforced polymers (CFRP) compression damaging scenario from first micro-damages to final failure of the material and potential effect of matrix (resin) on compressive mechanical properties and the damaging scenario is given by Khalil et al. [32]. Hafiz et al. [33] focuses on the failure analysis of woven fabric carbon-reinforced polymeric composites under tensile and flexural loading. To conduct a detailed investigation acoustic emission is used to attain damage evolution under flexural loading conditions.

This paper presents an effective integration of the digital image correlation technique and cluster analysis to enable quantitative evaluation of tensile damage localization in fiber-reinforced foam concrete. DIC enables high-precision, non-contact acquisition of full-field strain data, while the clustering algorithm performs automated segmentation and damage identification within complex strain fields. This combined approach significantly enhances the accuracy of damage localization and quantification. Moreover, it accommodates the material’s inherent heterogeneity and features intelligence, visualization, and a data-driven framework, thereby providing an effective tool for quantitatively tracking and intelligently assessing the damage evolution in fiber-reinforced foam concrete.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Specimen Preparation

This study used Ningxia Yinchuan Saima ordinary portland cement, which has a 28-day compressive strength of 51 MPa. The basalt fibers were sourced from Liaoning JinShi Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenyang, China), were 6 mm long, as shown in Figure 1. The primary mechanical property indices of the basalt fibers are detailed in Table 1. The blowing agent used was a commercially available animal protein blowing agent, and the mixing water was tap water from the laboratory. The specific preparation process for the test sample is as follows: (1) A foaming liquid is created by mixing the blowing agent and water in a quality ratio of 1:40. The weighed foaming liquid is injected into the foaming equipment (see Figure 2), where stable and uniform bubbles are generated by controlling the airflow rate; (2) Cement and water are mixed to form a cement slurry with a water-to-cement ratio of 1:2. The mixture is stirred for two minutes; (3) The weighed basalt fiber is uniformly mixed into the cement paste and stirred for an additional 2 min; (4) Air bubbles are introduced into the homogeneous fiber cement paste, with the foam dosage adjusted to control the density of the foam concrete. A low-speed mixing is performed for 1 min to achieve a uniform basalt fiber foam concrete slurry; (5) The basalt fiber foam concrete slurry is poured into a dumbbell-type test mold and allowed to stand at room temperature for 24 h; (6) The specimens are demolded and cured in a curing box (China Academy of Building Research, Beijing, China) for 28 days, with the temperature maintained at 20 °C and the relative humidity at 95%.

Figure 1.

Basalt fiber physical picture.

Table 1.

Main properties of basalt fiber.

Figure 2.

Foaming machine physical picture.

2.2. Design of Tensile Specimens

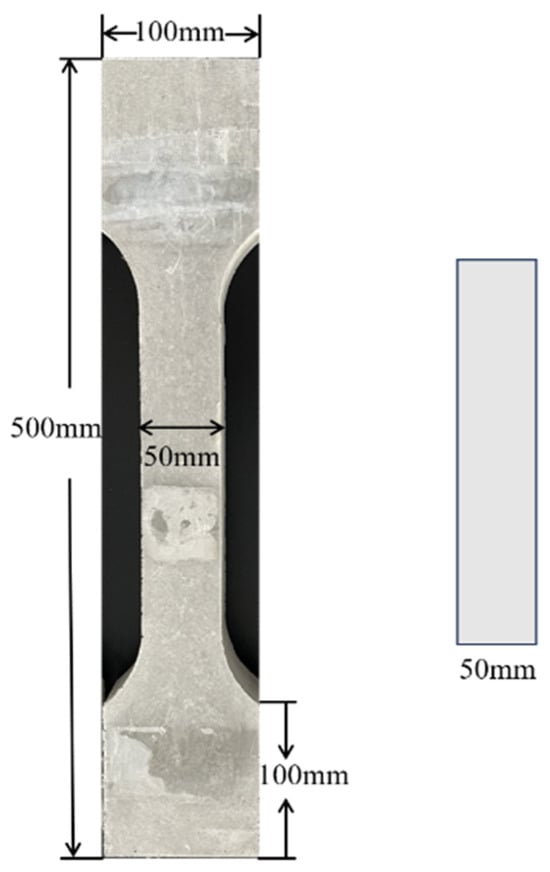

Three groups of uniaxial quasi-static tensile specimens with different matrix densities were designed for testing. The tensile specimens were dumbbell-shaped (see Figure 3 for detailed dimensions), with each group containing six specimens with different fiber content but the same matrix density. This resulted in a total of 18 quasi-static tensile specimens. Two test variables were considered: foam concrete density and basalt fiber volume dosing. The designed densities of foam concrete were 900 kg/m3, 1050 kg/m3, and 1200 kg/m3, while the basalt fiber volume dosages were 0%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.3%, 0.4%, and 0.5%. The length of the basalt fiber was 6 mm, and the physical drawings of a set of specimens are provided in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Dimensions of quasi-static tensile specimens.

Figure 4.

Physical drawing of quasi-static tensile specimen and speckle.

2.3. Uniaxial Quasi-Static Tensile Test

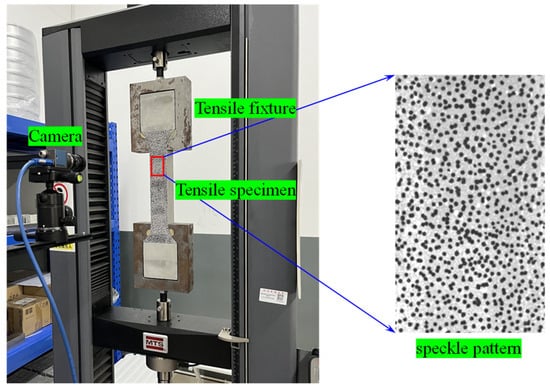

The quasi-static tensile test was performed using an MTS Exceed E44.304 microcomputer-controlled electronic universal materials testing machine (MTS, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) (see Figure 3). Due to the brittle nature of foam concrete, the experiment used displacement loading control and applied a relatively low loading rate of 0.2 mm/min. This study integrates the digital image correlation method with cluster analysis to quantitatively assess tensile damage localization in fiber-reinforced foam concrete. To facilitate this, a CCD camera (China Daheng (Group) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was positioned in front of the tensile specimen to capture real-time surface images under varying loading conditions. The CCD image acquisition device has a resolution of 3088 × 2064 pixels, with an imaging area of 420 mm × 280 mm. When analyzing the experimental results, the size of the speckles on the specimen surface has a significant influence on the measurement accuracy of the DIC method. The size and uniformity of the speckles produced by different fabrication techniques can vary considerably. According to references [34,35,36], the ideal speckle size is between 4 and 6 pixels. Considering the specimen size in this experiment, we used a method of randomly applying spots with a black marker to create speckles, thereby ensuring randomness and uniformity in their distribution (see Figure 5). In the DIC calculation process of this article, the size of the displacement calculation subset is 31 × 31, and the calculation step size is 10.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the testing system and speckle pattern of the specimen surface.

2.4. DBSCAN Clustering Method

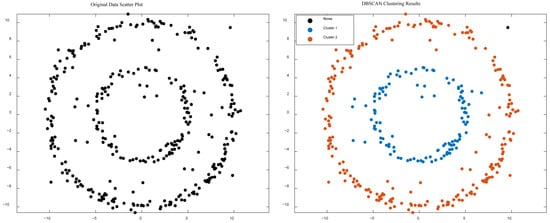

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) is a very popular and powerful unsupervised machine learning algorithm that is primarily used to discover clusters in data [37]. Unlike other clustering algorithms such as K-means, DBSCAN does not require the number of clusters to be pre-specified and is capable of recognizing clusters of arbitrary shapes, as well as marking data points that are considered noisy. The core concept of DBSCAN is to define clusters based on density. The core principle relies on two important parameters: (1) Epsilon (): defines the distance threshold from a given point to another point. If the distance between two points is less than or equal to , they are considered “neighboring”. (2) MinPts (): Indicates the minimum number of neighboring points (including the point itself) required for a point to be considered as a core point. For more details, refer to reference [38,39]. An example plot of the DBSCAN clustering method is given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

DBSCAN clustering example graph (left: original data scatter plot, right: DBSCAN clustering results).

In this study, a substantial amount of strain data acquired through the digital image correlation method will be systematically analyzed utilizing the cluster analysis technique. By performing cluster analysis on the strain field, key feature regions in the damage evolution process will be identified, facilitating the quantitative identification and assessment of damage localization behavior in basalt fiber foam concrete under uniaxial tensile loading. Additionally, this research aims to investigate the effect of basalt fiber incorporation on damage localization behavior. By comparing the clustering results of specimens with varying fiber volume fractions, the role of basalt fibers in delaying damage progression, dispersing strain concentration, and enhancing overall structural crack resistance will be analyzed.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Tensile Damage Analysis

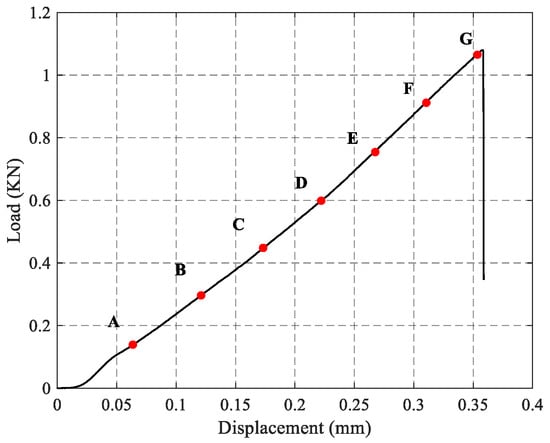

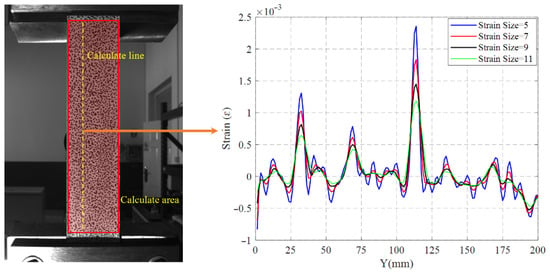

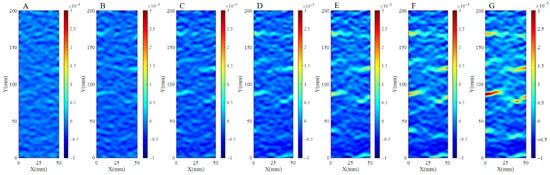

The tests were performed using the DIC method to obtain full-time and full-field displacement and strain information from the specimen surface during the loading process. Under tensile loading, the tensile strain in the vertical direction plays a decisive role in the tensile damage process. Therefore, vertical strain () was selected as the analysis factor, and seven characteristic points (A–G, Figure 7) were chosen from the displacement-load curve to analyze the tensile damage process of BFFC. It is important to note that the size of the strain calculation window significantly influences the results of strain field calculations using DIC. This study reflects the localization of damage (strain localization) in the material under tensile loading by accurately calculating strains. Figure 8 illustrates the strain results obtained from different strain windows along the yellow dashed line on the specimen surface. It demonstrates that a smaller strain window is more sensitive to significant strain regions and can accurately reflect their deformation. In contrast, a larger strain window tends to over-smooth the displacement data, leading to distorted strain information. Consequently, this paper uses a strain calculation window size of 5 × 5. Figure 9 shows the distribution of strain evolution in the vertical direction at each characteristic point (A–G, with loads gradually increasing) of the BFFC-900 specimen without basalt fiber. Comparative analyses indicate that the tensile damage process of the BFFC can be categorized into three distinct stages: the microcrack initiation stage, the microcrack synergy stage, and the main crack development stage. Microcrack initiation stage (B–C): The overall vertical tensile strain level of the specimen is low at this stage. However, a more obvious strain concentration area has appeared in the local area at the edge of the specimen, indicating that microcracks have begun to emerge there. Microcrack synergistic stage (C–E): In this stage, with the increase in load, multiple microcracks form and develop synergistically in the specimen. Significant strain concentration occurs in the local area (especially in the main crack formation area), which is much higher than in other areas. In the latter part of this stage, main cracks gradually form. Main crack development stage (E–G): The main crack forms in the middle of the specimen near the left edge. The vertical tensile strain at this position is significantly higher than that in other areas. With the continuous load increase, this strain difference expands dramatically, which ultimately leads to specimen fracture at the main crack.

Figure 7.

The displacement-load diagram of the BFFC-900 specimen without basalt fiber.

Figure 8.

The strain results calculated under different strain windows along the yellow dotted line on the specimen surface.

Figure 9.

The vertical strain evolution at each characteristic point ((A–G) load increasing gradually) of BFFC-900 specimen without basalt fiber reinforcement.

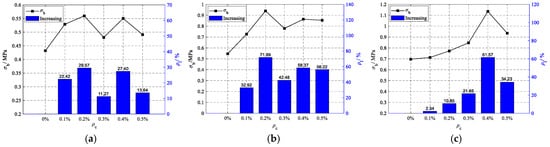

3.2. Ultimate Tensile Strength

The ultimate tensile strength of all specimens was determined by performing quasi-static tensile tests. Figure 10 shows the ultimate tensile strength of BFFCs and the percentage increase in ultimate tensile strength compared to specimens without basalt fiber reinforcement. The results demonstrate that the addition of basalt fibers significantly enhances the ultimate tensile strength of BFFCs with different matrix densities. However, the enhancement patterns for BFFCs with different matrix densities are not entirely consistent. For BFFC-900 and BFFC-1050, which have relatively low matrix densities, the tensile strength does not increase with the addition of basalt fibers. For BFFC-900, the tensile strength reaches its maximum value at a basalt fiber content of 0.2%, reflecting a 29.57% increase compared to the ultimate tensile strength of foam concrete without basalt fiber. Conversely, when the basalt fiber content increases to 0.3%, the tensile strength rises by only 11.27%. Similarly, the tensile strength of BFFC-1050 also peaks at a basalt fiber content of 0.2%, showing a 71.89% increase compared to foam concrete without basalt fiber. However, at a basalt fiber content of 0.3%, the increase in tensile strength diminishes to 42.48%. The above phenomena can be analyzed from two perspectives. Firstly, it is challenging to control the density of foam concrete precisely during the sample preparation process, leading to fluctuations in the actual density of the prepared foam concrete relative to the designed density within a certain range. Since the strength of foam concrete is closely related to its density, this discrepancy can significantly impact the material’s performance. Secondly, for foam concrete with a relatively low density and high porosity, fibers cannot bond effectively with the matrix. This means that the bridging effect of fibers is not fully utilized, thus diminishing the correlation between strength and fiber content. Conversely, for BFFC-1200, which has a relatively high matrix density, there is a positive correlation between ultimate tensile strength and fiber content. As the fiber content increases, tensile strength also increases, reaching a maximum value at 0.4% fiber content, which is 61.57% higher than that of foam concrete without basalt fiber. However, when the basalt fiber content reaches 0.5%, the increase in tensile strength diminishes. These results suggest that the optimal basalt fiber content is not fixed, but depends on the matrix density of the foam concrete. In the experiments conducted in this study, the optimal basalt fiber content for the three matrix densities ranged from 0.2% to 0.4%.

Figure 10.

Variation in ultimate tensile strength. (a) BFFC-900, (b) BFFC-1050, (c) BFFC-1200.

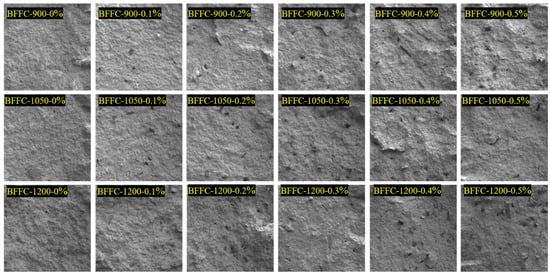

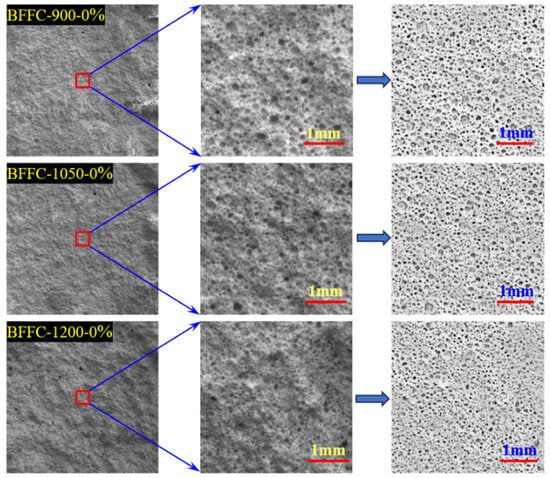

As illustrated in Figure 11, the optical images of the fracture surfaces of all the specimens after fracturing are presented. It has been observed that, as the content of basalt fibers increases, the corresponding fracture surfaces become increasingly irregular. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the process of fiber pull-out requires the expenditure of additional energy to overcome interfacial friction and adhesion forces. During this process, the fibers are pulled out of the matrix, leaving pits (where the fibers were pulled out) and protrusions (fiber tips remaining in the matrix) on the fracture surface. The numerous fiber pull-out marks are the primary cause of the rough and uneven fracture surface. Additionally, due to factors such as the strength distribution of the fibers themselves, differences in their orientation within the matrix, varying local stress states, and the presence of micro-defects, the fracture location for different fibers does not typically occur on the same plane. This significantly increases the irregularity of the fracture. Figure 12 shows a magnified image of the fracture surface of three samples with different matrix densities without basalt fiber reinforcement. Through appropriate image processing, it can be seen that, under the same preparation process, the main difference between foam concrete with different matrix densities is the size of the foam particles. The higher the matrix density, the smaller the corresponding foam particle size.

Figure 11.

Optical image of the fracture surface of all specimens.

Figure 12.

Local magnified images of fracture surfaces of specimens with different matrix densities without basalt fiber addition.

3.3. Statistical Analysis of the Strain Field Based on DBSCAN

To quantify the damage accumulation and damage localization of basalt fiber foam concrete under uniaxial tensile loading, cluster analysis was performed on a large amount of strain data obtained from digital image correlation (DIC) using the DBSCAN method. Specifically, for each load level shown in Figure 9, the top 181 strain points (3% of all calculated points) in the vertical direction were subjected to DBSCAN clustering analysis. The evolution of the top 181 strain points effectively reflects the strain localization process in the specimen. The distribution of these vertical tensile strain points also reflects the damage evolution process of the specimen [40,41]. Therefore, statistical analysis of the strain of the top 181 points was conducted to quantify the damage evolution process of the specimen as the load increases, as well as the damage extent and localization extent of the specimen at different load levels. For this purpose, two indicators (the damage extent factor and the damage localization factor) were defined to characterize the damage of the specimen:

The damage extent factors () is used to characterize the increment of vertical tensile strain in BFFCs, and is defined as follows:

where is the difference between the average vertical strain of the top M (In this article, M = N*0.03) points and the average vertical strain of all the points in the analysis area; N is the number of points in the analysis area; is the vertical strain of point j; is the maximum of .

The damage localization factor () is used to characterize the centralization of the distribution of BFFCs in the vertical direction, and is defined as follows:

where is the y-coordinate in the nth cluster of the top M points; is the y-coordinate of cluster center in the nth cluster; is the number of points contained in the top M points in the nth cluster; is the number of clusters; is the maximum of .

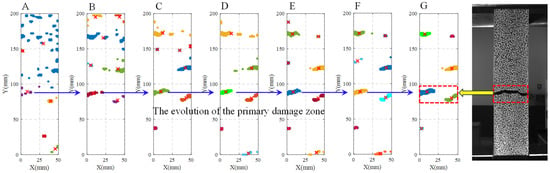

Section 2.4 of this paper states that the core principle of DBSCAN relies on two important parameters: Epsilon () and MinPts (). According to the strain data characteristics in this paper, take = 10, = 3. Figure 13 shows the DBSCAN clustering results for the top 181 tensile strain points in the vertical direction at each load level corresponding to Figure 9. In each figure, different colored regions represent different strain classes and red crosses indicate the cluster centers corresponding to the same color class. Under the initial loading condition, it can be seen that the high tensile strain points on the specimen surface exhibit a discrete distribution, indicating that no obvious damage regions have yet formed at this stage. As the load increases (stages B to E), the high tensile strain points begin to aggregate and evolve in localized regions, clearly showing the emergence and continuous development of multi-regional damage. In the later loading stage (stages E to G), the main damage zone gradually forms and dominates the damage evolution process, while the development of other secondary damage zones tends to slow down or stagnate. Ultimately, the specimen fractures and fails in the main damage zone.

Figure 13.

The DBSCAN clustering results of the vertical stretching strain points under each load level corresponding to Figure 9.

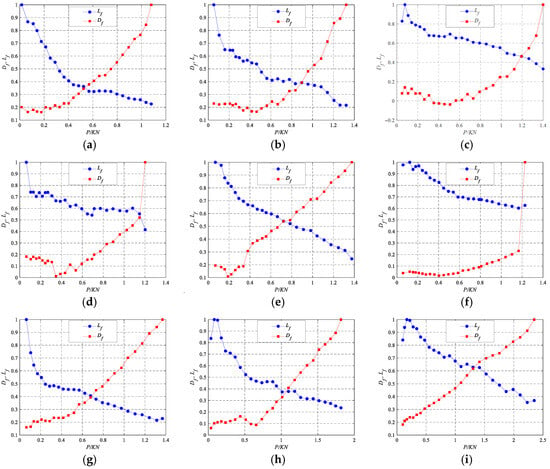

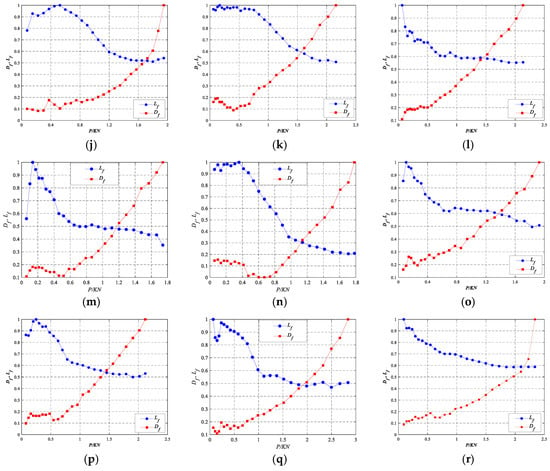

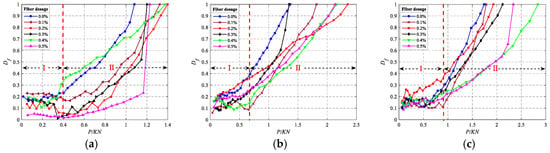

Figure 14 shows the load-dependent curves of and under different matrix densities and basalt fiber content. The results indicate that, despite differences in matrix density and fiber content, the load-dependent curves of and in all specimens exhibit similar trends. For : it can be divided into two stages. Stage I (low-value fluctuation stage): remains at a relatively low level overall, fluctuating within a certain numerical range. This indicates that the specimen has not yet undergone significant macroscopic damage at this load stage. Stage II (rapid growth stage): significantly increases and exhibits a rapid growth trend with increasing load. This indicates that the specimen has entered a distinct stage of damage development, with damage continuing to accumulate and intensify. For : it is also divided into two stages. Stage I (rapid decline stage): decreases significantly with increasing load. This change characteristic indicates that strain localization phenomena have occurred in the specimen during this stage, and the strain localization regions exhibit a multi-point concurrent trend. Stage II (slow decline stage): has decreased to a relatively low level, with a significantly slowed decline rate. This marks the significant development of damage localization, primarily due to the formation and continued development of the dominant damage zone, while the development of secondary damage zones has significantly slowed or even stagnated.

Figure 14.

Variation of and with increment of load for all specimens. (a) BFFC-900-0%, (b) BFFC-900-0.1%, (c) BFFC-900-0.2%, (d) BFFC-900-0.3%, (e) BFFC-900-0.4%, (f) BFFC-900-0.5%, (g) BFFC-1050-0%, (h) BFFC-1050-0.1%, (i) BFFC-1050-0.2%, (j) BFFC-1050-0.3%, (k) BFFC-1050-0.4%, (l) BFFC-1050-0.5%, (m) BFFC-1200-0%, (n) BFFC-1200-0.1%, (o) BFFC-1200-0.2%, (p) BFFC-1200-0.3%, (q) BFFC-1200-0.4%, (r) BFFC-1200-0.5%.

3.3.1. Effect of Basalt Fibers on the

Figure 15 shows a comparison of the damage-load curves of specimens with varying basalt fiber content. The damage development process (damage extent-load curve) of basalt fiber foam concrete with different matrix densities can be divided into two stages. In stage I: the damage extent-load curves of specimens with different basalt fiber content all exhibit a gradual upward trend and have similar shapes. During this stage, the damage extent of basalt fiber foam concrete with different matrix densities are all below 0.4, indicating a low level and suggesting that the fibers have a very limited inhibitory effect on material damage evolution. Stage II: As the load increases, the rate of increase in the damage extent-load curves of specimens with different basalt fiber content accelerates significantly. At this point, the differentiated effects of fiber content on damage control become evident. The same basic pattern is observed under three different matrix densities: at the same load level, the higher the fiber content, the smaller the corresponding damage variable, indicating a lower degree of material damage. Conversely, a decrease in fiber content results in an increase in the damage variable and a faster growth rate of the damage. Consequently, the incorporation of basalt fibers not only significantly delays the material’s damage progression but also effectively increases its initial damage threshold load.

Figure 15.

Comparison chart for variation of with increment of load. (a) BFFC-900, (b) BFFC-1050, (c) BFFC-1200.

3.3.2. Effect of Basalt Fibers on the

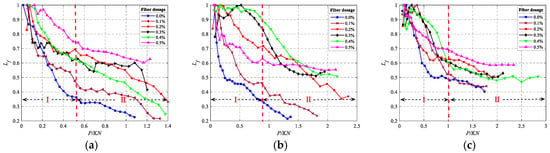

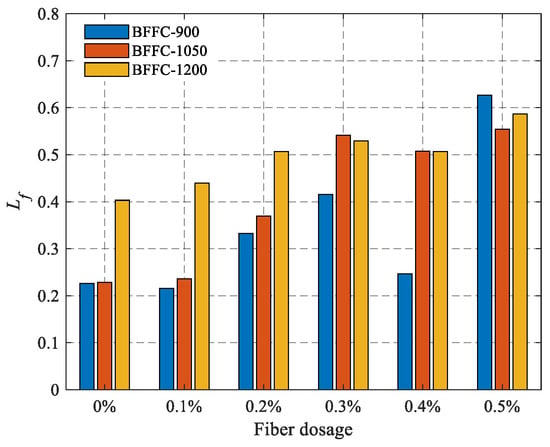

Figure 16 shows the variation curve of the localization coefficient with load. Similar to the pattern described in Section 3.3.1, this curve can also be divided into two distinct stages: Stage I: During this stage, the discretely distributed high tensile strain points gradually converge toward the local region of the specimen, forming a potential damage concentration zone. In this stage, the incorporation of fibers effectively suppresses the localization of strain. At the same load level, the localization coefficient increases with the increase in fiber content, indicating that fibers disperse stress and promote a more uniform stress distribution. Stage II: After entering this stage, the rate of decrease in the localization coefficient with increasing load significantly slows down. The main reason is that the primary damage zone (the primary crack zone) has essentially formed in this stage. Further increases in load primarily lead to the continued expansion of the main damage zone, while other secondary damage zones stabilize as stress is released. It is worth noting that fibers also have a certain inhibitory effect on the development of damage in the main damage zone during this stage. Figure 16 also shows that, at this stage, the higher the fiber content, the larger the corresponding localization coefficient, reflecting that higher fiber content can more effectively inhibit the rapid expansion of the main damage zone. Additionally, Figure 17 presents bar charts showing how the localization coefficient varies with fiber content for three different matrix density specimens at the moment of failure. This figure visually compares the influence of fiber content on damage localization at the moment of failure under different matrix densities.

Figure 16.

Comparison chart for variation of with increment of load. (a) BFFC-900, (b) BFFC-1050, (c) BFFC-1200.

Figure 17.

Bar chart of at tensile failure.

4. Conclusions

This study innovatively combines the DIC method with CA to propose a damage localization quantification analysis method named DIC-CA. This method is applied to systematically investigate the damage evolution process of basalt fiber foam concrete under quasi-static tensile loading conditions. Based on the clustering analysis results of the DIC full-field deformation data, two key damage characterization parameters were defined: the damage degree factor and the damage localization coefficient. These parameters are used to quantify the overall damage accumulation state of the material and the non-uniform spatial concentration of damage, respectively. By analyzing the evolution patterns of these parameters during the tensile process, the following main conclusions were drawn:

- (1)

- The experimental results of this study indicate that the addition of basalt fiber significantly enhances the ultimate tensile strength of basalt fiber foam concrete. The experiments demonstrate that, under three different matrix densities, the maximum tensile strength of specimens containing basalt fiber increased by 29.57%, 71.89%, and 61.57%, respectively, compared to the control group without fiber addition. It is worth noting that the experimental conclusions indicate that the optimal addition ratio of basalt fibers is not a fixed value but is closely related to the matrix density of the foam concrete. Under the three matrix density conditions studied in this research, the optimal addition ratio range of basalt fibers is 0.2–0.4%.

- (2)

- The statistical analysis results of this experiment show that the addition of basalt fibers not only effectively delays the damage process of the material but also increases the initial damage threshold load of the material. At the same time, the fibers disperse stress through their bridging action, promoting a more uniform stress distribution and effectively inhibiting the localization and concentration of damage (especially the rapid development of the main damage zone).

- (3)

- The damage degree factor and damage localization coefficient defined by the DIC-CA method in this paper can synchronously and quantitatively characterize two key dimensions of material damage: the former objectively reflects the overall damage accumulation of the material, while the latter precisely quantifies the degree of non-uniform spatial concentration of damage.

- (4)

- Although the DIC-CA method proposed in this paper demonstrates certain advantages in the quantitative analysis of material damage extent and strain localization, it also exhibits certain limitations. These limitations lie in the statistical analysis results being relatively sensitive to the two parameters of the DBSCAN clustering method, and to some extent also being influenced by the DIC computational parameters. The optimization of parameter combinations requires further research and exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y.; methodology, H.Y.; software, C.L. and Y.A., validation, C.L. and Y.L.; formal analysis, H.Y.; resources, R.M.; data curation, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.; writing—review and editing, H.Y.; visualization; Y.A. and Y.L.; supervision, Y.A.; funding acquisition, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Ningxia (Project No. 2026A1459) and the Young and Middle-aged Key Personnel Project of North Minzu University (Project No. 2025BG265).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BFFC | Basalt Fiber Foam Concrete |

| FC | Foam Concrete |

| DIC | Digital Image Correlation |

| CA | Cluster Analysis |

References

- Hou, L.; Li, J.; Lu, Z. Influence of foaming agent on cement and foam concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, M. Experimental research on the preparation and properties of foamed concrete using recycled waste concrete powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 407, 133370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhasindrakrishna, K.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Pasupathy, K. Collapse of fresh foam concrete: Mechanisms and influencing parameters. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2021, 5, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C. Effect of superabsorbent polymer on the foam-stability of foamed concrete. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2022, 127, 104398. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, S.; Mydin, M.; Bahrami, A. Development of ultra-lightweight foamed concrete modified with silicon dioxide (SiO2) nanoparticles: Appraisal of transport, mechanical, thermal, and microstructural properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 3308–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydin, M.; Abdullah, M.; Sor, N. Thermal conductivity, microstructure and hardened characteristics of foamed concrete composite reinforced with raffia fiber. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydin, M.; Jagadesh, P.; Bahrami, A. Use of calcium carbonate nanoparticles in production of nano-engineered foamed concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Cao, K.; Sun, L. Review on the durability of polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6652077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, H.; Latifi, M.; Jamshidi, M. Hybrid short fiber reinforcement system in concrete: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 142, 280e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambichik, M.; Abdul Samad, A.; Mohamad, N.; Mohd Ali, A.; Othuman Mydin, M.; Mohd Bosro, M. Effect of combining palm oil fuel ash (POFA) and rice husk ash (RHA) as partial cement replacement to the compressive strength of concrete. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2018, 10, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, H.; Mydin, M.; Roslan, A. Effects of fibre on drying shrinkage, compressive and flexural strength of lightweight foamed concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 587, 144e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, A.; Tunc, U.; Bahrami, A. Use of waste glass powder toward more sustainable geopolymer concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 8533–8546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, C. Properties of foamed concrete with Ca(OH)2 as foam stabilizer. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2021, 118, 103985. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, M. Laboratory investigation of foamed concrete prepared by recycled waste concrete powder and ground granulated blast furnace slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Qu, N.; Li, J. Development and functional characteristics of novel foam concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 324, 126666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falliano, D.; Restuccia, L.; Gugliandolo, E. A simple optimized foam generator and a study on peculiar aspects concerning foams and foamed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 268, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Gil, A.M.; Bolina, F.L.; Tutikian, B.F. Thermal damage evaluation of full scale concrete columns exposed to high temperatures using scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. DYNA 2018, 85, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manica, G.C.; Bolina, F.L.; Tutikian, B.F.; Oliveira, M.; Moreir, M.A. Influence of curing time on the fire performance of solid reinforced concrete plates. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2506–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Zou, X. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Basalt Fiber Concrete after Cryogenic Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Polymers 2023, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymski, F.; Musiał, M.; Trapko, T. Mechanical properties of fiber reinforced concrete with recycled fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 198, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Tayeh, B.; Aisheh Abu, Y.; Salih, M. Exploring the performance of steel fiber reinforced lightweight concrete: A case study review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaini, Z.; Rum, R.; Boon, K. Strength and fracture energy of foamed concrete incorporating rice husk ash and polypropylene mega-mesh 55. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 248, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugahed Amran, Y.; Alyousef, R.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Khudhair, M.; Hejazi, F.; Alaskar, A.; Alrshoudi, F.; Siddika, A. Performance properties of structural fibred foamed concrete. Results Eng. 2020, 5, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhu, J.; Sun, T.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Yin, W.; Han, J. Multiple effects of nanoCaCO3 and modified polyvinyl alcohol fiber on flexure-tension-resistant performance of engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 303, 124426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, H.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Synthetic fibers for cementitious composites: A critical and in-depth review of recent advances. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 491–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, B.; Sathyan, D.; Madhavan, M.; Raj, A. Mechanical and durability properties of hybrid fiber reinforced foam concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 245, 118373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, A.; Fox, B.; Nikzad, M.; Eisenbart, B.; Chai, B.X.; Blanchard, P. Evaluation of the failure mechanism in polyamide nanofiber veil toughened hybrid carbon/glass fiber composites. Materials 2022, 15, 8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Choi, H.; Park, M. A review: Natural fiber composites selection in view of mechanical, light weight, and economic properties. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2015, 300, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazao, C.; Barros, J.; Camoes, A.; Alves, A.; Rocha, L. Corrosion effects on pullout behavior of hooked steel fibers in self-compacting concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 79, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihada, S. Effect of polypropylene fibers on concrete fire resistance. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2021, 17, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Kim, T. Unveiling the underlying mechanisms of tensile behavior enhancement in fiber reinforced foam concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 398, 132509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, K.; Moreau, G.; Aboura, Z. Digital image correlation, acoustic emission and in-situ microscopy in order to understand composite compression damage behavior. Compos. Struct. 2020, 258, 113424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.Q.; Tabrizi, I.E.; Khan, R.M.A.; Tufani, A.; Yildiz, M. Microscopic analysis of failure in woven carbon fabric laminates coupled with digital image correlation and acoustic emission. Compos. Struct. 2019, 230, 111515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P. Subpixel displacement and deformation gradient measurement using digital image/speckle correlation (DISC). Opt. Eng. 2001, 40, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Guo, R.; Xia, H. Application of the mean intensity of the second derivative in evaluating the speckle patterns in digital image correlation. Opt. Laser Eng. 2014, 60, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Lu, Z.; Xie, H. Mean intensity gradient: An effective global parameter for quality assessment of the speckle patterns used in digital image correlation. Opt. Laser Eng. 2010, 48, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ester, M. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. Proc. Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min. 1996, 96, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Luchi, D.; Rodrigues, A.L.; Varejão, F.M. Sampling approaches for applying DBSCAN to large datasets. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 2019, 117, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Seo, S.; Tran, H.; Khol, S. A novel method for acoustic emission source location in CFRP-concrete debonding using ΔT mapping and DBSCAN algorithm. Measurement 2024, 236, 115097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Lei, Z. Study on bending damage and failure of basalt fiber reinforced concrete under freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 163, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, G.; Song, H. Experimental characterization of strain localization in rock. Geophys. J. Int. 2013, 194, 1554–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).