Abstract

Copper has become more important owing to its eco-friendliness and persistent efficacy against infections. Furthermore, copper has benefits such as safety in use and durability. This study aimed to develop and assess the antibacterial efficacy of stainless steel coated with a composite layer, which is nanostructured and incorporates copper, to create antibacterial surfaces with good adherence and good corrosion resistance. The composite coating was produced using anodic oxidation, with an external copper layer applied via pulse electroplating. The homogenous cauliflower-like covering showed important characteristics, like increased surface roughness, boosted surface free energy, reduced contact angle, and higher hardness. Additionally, the adherence between the composite covering and the substrate was exceptional. Electrochemical experiments indicated aggressive corrosion behavior in chloride-containing settings. Antibacterial tests were conducted on four prevalent bacterial strains: Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhimurium—microorganisms often linked to healthcare and environmental pollution. The coating exhibited enhanced antibacterial efficacy relative to untreated steel and anodized steel. Results indicated that the composite coating is an effective and possibly cost-efficient method for controlling the surface proliferation of the mentioned pathogens.

1. Introduction

For decades, steel has been extensively utilized in industrial sectors (including petrochemistry, ultra-supercritical power, transportation, nuclear power plants, aerospace, and certain niche industries) and biomedical applications owing to its affordability (with a significant price advantage compared to other metallic biomaterials), commercial viability, fracture toughness, exceptional wear resistance, corrosion resistance, and superior mechanical strength [1,2,3]. Additionally, its remarkable combination of strength and ductility, along with the capacity for processing it into intricate shapes, renders steel a significant category of materials from both scientific and commercial perspectives. The inherent characteristics of steel have made it a crucial component in technological progress during the past century, with its annual use increasing at a rate surpassing that of other materials [2]. For steel, these qualities depend on its chemical composition and microstructure. Carbon controls the martensitic transformation’s hardness, strength, hardenability, and start and finish temperatures. Chrome improves hardenability, wear, edge durability, and corrosion resistance. Vanadium refines main grains, improving toughness, wear, edge retention, and heat resistance. Tungsten carbides improve heat and high-temperature wear resistance. Cobalt stops grain growth at high temperatures [4]. K455 steel was chosen in this study due to its widespread use in industrial components. It is characterized by high toughness, good machinability and polishability, high compressive strength, and good dimensional stability. It offers a simple heat treatment process with low hardening temperatures and single tempering [5]. It is used in both industrial tools (e.g., cutting components, shafts, dies) and specialized biomedical or dental devices due to its surface hardenability and excellent response to surface treatments.

An additional significant attribute of steel is its compatibility with surface engineering techniques, including anodization and electrodeposition, rendering it an optimal substrate for the creation of multifunctional coatings [6,7,8]. Surface coating, sol–gel, EDTA and electrolysis are steel surface modification methods. A layer of suitable material is applied to the steel surface during surface coating [9].

Many of these steel products can carry and spread harmful microbes. Live bacteria can form biofilms, which are less sensitive to antimicrobial treatments like disinfectants and surfactants, due to their easy adhesion to surfaces [10]. For example, hospital-acquired illnesses impact around 4.1 million people in Europe annually, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [11]. Anodization—an electrochemical process that modifies surface properties—can enhance surface reactivity and may contribute to antimicrobial performance by increasing roughness or altering the surface chemistry. At the same time, the use of copper-based surface treatments has gained increasing attention in recent years due to their strong antibacterial potential. Copper acts through a multifaceted mechanism, releasing ions that generate oxidative stress, damage bacterial membranes, and interfere with key cellular functions [12,13].

Nanoscale surface topography on metal alloys including aluminum, titanium, and steel is gaining interest as an eco-friendly alternative for antipathogenic activities and bacterial adhesion control [1]. Anodization forms a nanostructured passive oxide layer on the metal anode, particularly in oxygen-rich environments. This uniform, insulating layer inhibits ionic conductivity and corrosion [14]. It is a cheap and straightforward nanomodification method for Ti alloys, tantalum, zinc, and steel [15]. The anodic oxide film formed on the steel substrate is considered for use in surface protective films, photocatalysts, water-splitting devices, supercapacitors, gas sensors, solar cells, antibacterial surfaces, and cell-affinity surfaces [16]. The anodization of nanostructures on steel surfaces was studied for its impact on surface characteristics, cellular functions, and bacterial colonization. These nano-feature surfaces increased ALP activity and calcium mineral deposition. Anti-fouling action was shown against Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative P. aeruginosa colony development and biofilm formation [6].

Drug resistance makes antibiotics and other antimicrobials ineffective, making infection treatment harder or impossible. In this setting, designing antimicrobials without synthetic antibiotics is crucial, and several studies have examined other strategies [17]. Cu and Ag are known antibacterial elements that can be added to metals to improve their antibacterial capabilities. Due to the expensive cost and restricted solubility of Ag in some steels, Cu is now used for its broad-spectrum antibacterial properties [18,19]. Copper is biologically compatible [20]. Copper and copper-based materials are attracting increasing scientific attention due to their intrinsic and broad-spectrum antibacterial characteristics, long-standing medicinal and industrial application, and low resistance development [21]. Copper-based nanomaterials suppress pathogenic microorganisms and stimulate fibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation and migration, boosting angiogenesis, collagen formation, and wound healing [20]. Currently, antimicrobial steel is primarily developed through copper bulk alloying and surface modification techniques to confer bactericidal properties [22]. Various Cu-containing steel alloys have demonstrated consistent antibacterial efficacy against prevalent microorganisms [23]. The submicron and microscale topographies of Cu-bearing stainless steel influence bacterial adhesion and interactions, playing a key role in initiating contact-mediated toxicity [24]. The selective laser melting of Cu-alloyed steel has shown that increased Cu content and post-heat treatment enhance antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, while sustained Cu ion release contributes to efficacy against Escherichia coli [25]. Copper also inactivates viruses including Influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and HCoV-229E, and pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica, and Campylobacter jejuni, according to other studies [26,27]. However, the corrosion resistance of Cu-alloyed steel remains limited, as Cu-rich precipitates formed during aging can compromise the passive film. Researchers are attempting to enhance steel biomaterials’ bacterial activity by changing surface chemistry with antimicrobial compounds in organic or inorganic coatings. Although these techniques have led to advancements, they are complicated and have significant limitations [28]. Additionally, copper coating on steel is hindered by poor adhesion, surface contamination, chromium oxide presence, and low tribological resistance to micron-sized particles [22]. Despite their antibacterial properties, these coatings are prone to corrosion due to microstructural defects that allow electrolyte ingress. To improve substrate adhesion and enhance mechanical and corrosion resistance in Al-based Cu coatings, an anodic oxidation process followed by Cu electroplating has been proposed. This method yields coatings with improved mechanical stability and sustained antibacterial performance [29]. For this coatings, the surface concentration of copper is essential for antibacterial effectiveness, while greater coating thickness and reduced porosity are key factors in enhancing corrosion and wear resistance [30].

Pulsed electrodeposition offers a promising method for producing copper coatings on steel, utilizing intermittent current or voltage to control metal ion reduction. The alternating ‘on’ and ‘off’ cycles enhance coating microstructure, morphology, and overall properties [31]. However, experimental results indicate that effective antibacterial activity requires copper precipitates of a critical size. While extensive Cu precipitation enhances antibacterial properties, it does not improve the material’s mechanical strength [32].

In conclusion, balancing antibacterial performance with corrosion resistance thus remains a critical challenge [19]. Copper has multiple antimicrobial processes, including ROS production, membrane depolarization, protein malfunction, nucleic acid destruction, and biofilm suppression. Copper works through many overlapping processes, unlike antibiotics, which typically target a single biological pathway. The multimodal action considerably minimizes the risk of developing resistance [21]. In this context, our goal was to develop a silver-free, and antibiotic-free coating based on copper and anodized nanostructure strategies. The present study investigates the antibacterial effectiveness of steel samples subjected to different treatments: untreated (control), anodized, and anodized followed by copper functionalization using 100 electrical pulses. The samples were tested in a liquid environment against four common bacterial strains: Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhimurium—organisms frequently associated with healthcare and environmental contamination.

This work’s novelty lies in the innovative fabrication of a nanostructured copper-containing a composite coating on stainless steel that combines strong antibacterial properties with excellent adherence and corrosion resistance. Unlike previous approaches, which have explored anodization or copper coating separately, the presented method uses anodic oxidation followed by pulse electroplating to achieve a unique nanostructure that significantly improves steel properties. This synergy results in a durable, antibacterial surface that is scalable, and compatible with industrial steel alloys, which has the potential to be used as protection against common pathogens associated with healthcare and other industrial settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Steel Anodization

The experimental work was carried out on K455 steel samples (designated OL), provided by Böhler, with the following nominal chemical composition (wt%): C 0.60%, Si 0.69%, Mn 0.34%, Cr 1.19%, V 0.18%, W 2.00%, P 0.015%, S 0.012%, and Fe 94.97%. Round samples with a surface area of 9.6 cm2 and 2 mm thickness were used in this study.

Step 1 in surface modification was surface pretreatment. The surfaces of the specimens underwent chemical etching in sulfuric acid (H2SO4) for 5 min to remove surface oxides and contaminants. This was followed by a sequential mechanical polishing procedure using silicon carbide abrasive papers (CarbiMet, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA), starting with P320 grit and progressing to P1200 grit, to obtain a uniform and smooth surface finish. Residual surface impurities were subsequently removed via ultrasonic cleaning in ethanol. The sample was named OL control.

Step 2 in surface modification was anodization. The anodization was performed through electrolysis in a conventional three-electrode electrochemical cell at 1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl, 3M KCl). Etched, polished, and ultrasonicated K455 steel samples (OL control) were employed as the working electrodes, while an Ag/AgCl (3M KCl) electrode served as the reference electrode, and a platinum plate was used as the counter electrode. Electrochemical measurements and potential control were performed using a PGSTAT 102N potentiostat/galvanostat (Metrohm Autolab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands). Various studies on anodization conditions were conducted under differing experimental parameters, including variations in applied voltage and electrolyte composition. For clarity and conciseness, only the optimized conditions are presented here—those which resulted in the formation of a uniform, nanostructured oxide coating devoid of exfoliation. The anodization process was carried out in a 50% NaOH aqueous electrolyte at a constant temperature of 70 °C, maintained using a UC152 hotplate, for a duration of 30 min. Following anodization, the samples were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water and subjected to thermal treatment (calcination) in a LabTech furnace (Daihan Labtech Co., Namyangju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea). The calcination was conducted at 500 °C for 30 min, after which the samples were removed from the furnace and allowed to cool naturally to room temperature under ambient conditions. These samples were named OL nano.

2.2. Copper Plating

Step 3 was cooper plating. The anodized K455 steel sample (OL nano), previously treated at 1.5 V, was subsequently subjected to pulsed copper electrodeposition. This process was conducted in a two-electrode electrochemical cell, with the anodized steel specimen serving as the working electrode and a copper electrode as the counter electrode. The optimization of copper electrodeposition parameters, such as applied voltage and number of deposition cycles, was previously investigated [33]. In the present study, the parameters that yielded a uniform deposition—characterized by homogeneous small grain size, absence of irregularities, and lack of significant porosity—were selected for use. Electrodeposition was performed at 50 °C using an alkaline electrolyte solution composed of 60 g/L CuCN and 30 g/L KCN. A PGSTAT 302N potentiostat/galvanostat (Metrohm Autolab, Utrecht, The Netherlands) was employed to control the electrochemical parameters. The applied potential waveform consisted of an initial nucleation step at −2 V held for 2 s, followed by 100 pulses alternating between an open circuit potential step of 5 s and a deposition step at −1 V for 5 s. These samples were named OL nano Cu. Although cyanide-based baths are widely used in controlled industrial plating processes, their toxicity requires careful handling and limits their environmental acceptability. Our choice of this cyanide electrolyte was also motivated by earlier findings showing that this electrodeposition achieved excellent adhesion [33]. Future research will therefore focus on more sustainable chemistry for copper deposition. Several cyanide-free electrolytes have been reported in the literature, including: solutions containing copper sulfate, glycine as a complexing agent, and sodium hydroxide for pH control [34], copper sulfate combined with the complexing agent monosodium glutamate (C5H8NO4Na) and potassium hydroxide for pH adjustment [35] and mixtures of copper sulfate, sodium gluconate, sodium hydroxide, and various additives [36]. However, despite their promise, none of these electrolyte systems have yet been adopted for industrial-scale applications

2.3. Samples Characterizations

SEM analyses are crucial for elucidating surface morphology changes that directly influence antibacterial effectiveness. The surface morphology was examined using a Nova NanoSEM 630 scanning electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analyzer.

Contact angle measurements are very important for determining surface wettability and calculating surface energy components, both of which critically affect bacterial adhesion and thus the antibacterial performance of a material. Contact angle values were recorded in at least three spots on each sample surface. The sessile drop technique was used for these tests with a Hamilton glass syringe having an elongated blunt needle. A drop of about 3–5 μL was used for measurements. To be able to calculate surface energy according to Owens–Wendt model using the equations and parameters described in a previous work [37,38], contact angle values were recorded with three different liquids with different polarities: distilled water, ethylene glycol (Sigma Aldrich, EG), and dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma Aldrich, DMSO). All presented values are the average values of at least three measurements, and all calculations regarding average, standard deviation and surface energy were performed using Excel software.

AFM was used here to characterize representative surface regions rather than to provide a full statistical mapping of roughness over the entire macroscopic surface. Assessments were conducted in contact mode utilizing an A.P.E. Research A100-SGS atomic force microscope (AFM). Data capture and image processing were conducted with Gwyddion software., Version 2.70. AFM measurements were performed on three images acquired from three different locations for each sample, with a scan area of 10 × 10 µm2. The regions were selected within the central part of the films, avoiding edges and visible defects, and were chosen without any a priori preference for smoother or rougher zones. The arithmetic mean roughness calculated over the whole scanned area was Ra, based on these three measurements. Similar Ra values and surface morphology were obtained for all probed regions.

Hardness measurements were made with a Wilson Tukon 1102 hardness system (Buehler business) using a weight of 1 kg for a duration exceeding 10 s. Three indentations were created on each type specimen, one in each quadrant, equidistant from the center. The data were recorded after the removal of the penetrator to mitigate the impact of elastic recovery. The hardness obtained in this study must be regarded with precaution because the penetration depths are larger than the thickness of the deposited layer, so the contribution of the substrate to the measured hardness is important.

Antibacterial layers must have strong coating adherence to avoid delamination and inhibit bacterial colonization. Testing Method B—Cross-Cut Tape Test, a common ASTM D3359 standard [39] for coating adherence to substrates under dry circumstances, was used to evaluate coated surfaces. This approach is ideal for coatings under 125 µm in thickness. To execute the cross-cut test, a specialized cutting instrument with a razor blade (with a cutting-edge angle between 15° and 30°) made a grid of parallel and perpendicular incisions. This instrument maintained cut spacing and depth, which is essential for repeatability and precision. According to ASTM requirements, the lattice pattern included 6 or 11 cuts per direction, depending on coating thickness and substrate hardness. After creating the grid, ASTM-specified pressure-sensitive adhesive tape was placed firmly across the cross-hatched region to ensure complete surface contact. To test coating integrity, the tape was quickly removed at 180°. To assure reproducibility, each sample was processed twice. After tape removal, the tested portions were examined under optical magnification for coating delamination, peeling, or flaking along the cuts or grid squares. The ASTM D3359 adhesion classification scale was used to qualitatively and quantitatively rate each sample’s coating detachment:

- 5B—The edges of the cuts are completely smooth with no detachment of coating; the lattice remains fully intact. This rating indicates excellent adhesion.

- 4B—Small flakes of the coating are detached at the intersections of the cuts; the affected area is less than 5%. This denotes very good adhesion with minimal failure.

- 3B—Noticeable flaking of the coating occurs along the edges and intersections of the cuts; 5% to 15% of the area is affected. This is considered acceptable adhesion, though some localized failure is present.

- 2B—Partial detachment of the coating is observed along the edges and within several squares; 15% to 35% of the grid area shows failure. This indicates moderate adhesion.

- 1B—Significant flaking occurs along the cut lines, and entire squares of the coating may be removed; 35% to 65% of the area is affected. This represents poor adhesion.

- 0B—Extensive delamination and coating removal, with more than 65% of the lattice affected. This reflects complete adhesion failure.

The classification provides a standardized means of comparing coating adhesion across different materials, surface treatments, or environmental conditions. All tests were conducted at ambient laboratory temperature and relative humidity, following the recommended conditioning and handling protocols outlined in the ASTM D3359 standard.

Electrochemical measurements were conducted using an Autolab PGSTAT 302N potentiostat/galvanostat (Metrohm Autolab, B.V.) in NaCl 0.9% as electrolyte. Potentiodynamic polarization techniques were employed to determine the corrosion rate. A custom-made plexiglass electrochemical cell equipped with an O-ring was used to expose a defined surface area of 0.5 cm2 of the sample to the corrosive medium.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves (Tafel plots) were recorded at a scan rate of 2 mV/s over a potential range of ±300 mV relative to the open circuit potential. Data were analyzed with Nova 1.11 software to obtain corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion current (Icorr) and corrosion rate. Also, using corrosion current, protection efficiency (E) was determined using the following equation from the literature [40]:

where Icorr and Icorr0 represent the corrosion current for modified steel as well as the corrosion current for the OL control.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed at the open circuit potential with an AC perturbation amplitude of 10 mV, over a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 105 Hz. All data acquisition and analysis were carried out using Nova 1.11 software.

Mott–Schottky measurements were performed over a potential range from −0.6 V to 0.85 V, with an incremental step of 50 mV. The measurements were carried out at a fixed frequency of 1000 Hz. The Mott–Schottky relationship provides insight into the potential-dependent behavior of the space-charge layer capacitance, as described by well-established equations in the literature [41,42]:

in this context, e denotes the elementary charge (1.6 × 10−19 C), ε0 is the vacuum permittivity (8.85 × 10−14 F cm−1), and εr represents the relative dielectric constant of iron oxide (assumed to be 15.6) [43,44]. NA and ND correspond to the acceptor and donor densities, respectively. E denotes the applied potential, φfb is the flat-band potential, k is the Boltzmann constant (1.38 × 10−23 J K−1), and T is the absolute temperature. The values of NA and ND can be determined from the slope of the linear region in the Mott–Schottky plot (C2 vs. E).

All electrochemical tests were performed in triplicate on fresh prepared samples, and the presented values are the average values.

Grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GI-XRD) studies were conducted utilizing a 9 kW Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer, which is equipped with a CuKα1 source that emits a monochromatic beam with a wavelength of λ = 0.1504 nm. The data were obtained in grazing-incidence mode, maintaining a constant incidence angle of 0.5°, while the detector traversed from 10 to 95° at a scan speed of 5°/min.

A Thermo Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer utilizing monochromatic Al Kα X-rays (1486.6 eV) at a 90° take-off angle was employed for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Survey spectra were obtained at a resolution of 200 eV, whereas high-resolution spectra were acquired at 20 eV. A background reduction for Shirley was performed beforehand using a mixed Gaussian–Lorentzian function for the deconvolution of core-level spectra.

Standard laboratory strains of S. aureus ATCC BAA 1026, E. coli ATCC 8738, P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442, and S. typhimurium ATCC 14028 were cultivated in liquid Luria–Bertani (LB) media at 37 °C for 18–24 h. To evaluate the antibacterial performance of the tested materials, a quantitative assay based on bacterial growth inhibition in liquid medium was employed. Antibacterial activity was evaluated using the OD600 method, as it offers a quantitative, sensitive, very fast, cheap, easy, nondisruptive, high-throughput, and reproducible assessment of bacterial growth inhibition in liquid media [45]. This method was preferred over the agar diffusion-based ZOI assay, which is qualitative and less precise [46], particularly in this study, where the large size and weight of the coated samples made it impractical—samples could not remain adhered to the agar surface and would detach upon plate inversion. Prior to testing, all sample surfaces were sterilized under UV light to prevent any contamination. For the antibacterial tests sterile samples were incubated for 24 h. Each tube contained 5 mL of LB medium inoculated with 1% (v/v) of an overnight bacterial culture with a density of 0.86 × 105 CFU/mL (i.e., 50 µL culture added to 5 mL medium). Incubation was carried out in a Laboshake Gerhardt orbital shaker at 37 °C and 200 rpm. The optical density (OD600) of each sample and the corresponding control (bacterial suspension without material) was measured using a Jenway UV-VIS spectrophotometer. Antibacterial efficacy was quantified by calculating the growth inhibition percentage (I%), based on the difference in turbidity between the treated and untreated cultures [47].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The antibacterial inhibition data were statistically evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether the observed differences between treatments (OL, OL nano and OL nano Cu) were significant. For each bacterial strain, the experiments were performed in triplicate to estimate variability, and the results were assumed to follow a normal distribution with homogeneous variance. The statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel’s Data Analysis Toolpak. Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was subsequently applied to identify pairwise differences among treatments, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Composite Sample Preparation and Surface Characterizations

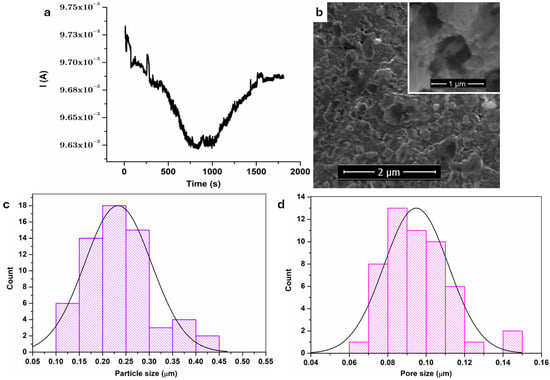

The current time graph acquired during anodization is presented in Figure 1a. In the first part, between 0 and about 800 s, the current decreased rapidly. This could be due to the creation of an oxide layer on the steel surface [6]. This was followed by a second zone, from 800 s to about 1500 s, where the current flowing through the system intensified. The oxide layer commenced dissolving, leading to the development of nanostructures [6].

Figure 1.

(a) Current-time curve recorded during steel anodization; (b) SEM images of anodized steel; (c) particle size; (d) pore size.

In the SEM image from Figure 1b, a uniform, nanostructured, porous oxide layer can be observed, with a 3D structure. The layer contains spherical platelets of varying sizes, characterized by pores and microcracks, as can be seen in the inset from Figure 1b.

Using Image J program, version 1.54p, we determined the particles’ and pores’ diameters, and the results are shown in Figure 1c,d. At least 50 measurements were performed for each parameter. The average particle size was 0.23 ± 0.07 μm, and the average pore diameter was 0.09 ± 0.02 μm.

The porous surface is designed to increase the surface area and facilitate the improved diffusion of reactants and products in the electrolyte onto electro-active surfaces [48]. Although different SEM magnifications were used to better illustrate specific morphological features, surface roughness comparisons were quantitatively addressed using AFM analysis.

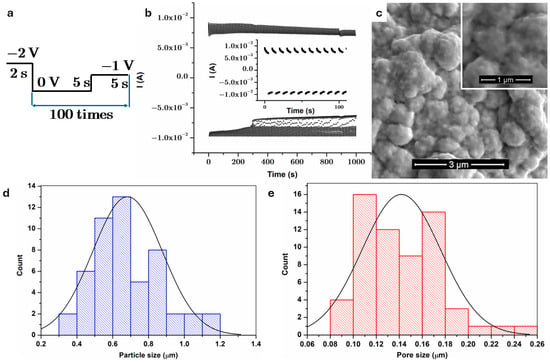

Figure 2a shows the diagram of the pulse method used for copper electrodeposition on anodized and thermal treated steel. The potential was initially set to −2 V for 2 s to start copper nucleation at the sample surface by the reduction of Cu2+ ions. Second potential, 0 V, was the open circuit potential. This brief period in which the potential is at open circuit is used for stress relief, the reorganization of copper crystals, and texture development. Additionally, the homogeneous diffusion of Cu2+ towards the sample surface take place during this period without current, as mentioned in other studies [49].

Figure 2.

(a) Diagram of the pulse method used to deposit copper on anodized steel; (b) current time curve recorded during copper electrodeposition; (c) SEM images of composite coating on steel; measurements with image j: (d) particle size; (e) pore size.

The electrodeposition of copper from cyanide electrolytes was selected, as this facilitates the formation of a coating on steel with excellent adherence. The direct electrochemical deposition of copper onto steel using commonly employed acid electrolytes results in coatings with inadequate adherence to the steel substrate due to the occurrence of the contact exchange process [50]. While the current method is not immediately environmentally scalable, it serves as a conceptual platform for optimizing multifunctional coatings. Transitioning to safer, cyanide-free electrolytes (e.g., sulfate-, citrate-, or pyrophosphate-based compounds) will be essential for future practical implementation.

A homogeneous cauliflower-like coating with decreased porosity and granular textures is evident on top of the anodic oxide film visible in Figure 2c. The uneven particles are uniformly dispersed, resulting in uniform covering of the substrate. According to the literature [51], the cauliflower growth morphology often arises from the development of high index planes coupled with an accelerated growth rate at elevated current densities. The presence of many deposition growth sites at elevated current density results in non-directional grain development, leading to the observed structure in the coating morphology [51].

ImageJ (version 1.54p) software was used to estimate the sizes of particles and pores, with the findings illustrated in Figure 2d,e. A minimum of 50 measurements were performed for each parameter. The mean particle size was 0.68 ± 0.19 μm, whereas the mean pore diameter was 0.14 ± 0.03 μm.

EDX spectra are presented in Figure S1. Spectra showed O, Fe, and Na peaks for OL nano. For OL nano Cu, there are peaks for O and Cu.

Contact angle values and calculated surface energy were presented in Table 1. All samples were hydrophilic, with water contact angles lower than 90°. The values corresponding to nanostructured OL were more hydrophilic compared to the OL control (4° and 20° compared to 78° for the control). The water contact angle for OL control is in great agreement with values reported in the literature [1,6,24,52]. For the anodized sample, some studies report an increased contact angle in the case of anodization in the ethylene glycol monobutyl ether solution containing perchloric acid [6] and a decrease in contact angle value after anodization in NaOH, such as we used [53]. For Cu-coated samples, the literature notes a decreased water contact angle, as occurred in our case [11].

Table 1.

Contact angle values and surface energy for steel samples.

Surface free energy is another important parameter. The values obtained are presented in Table 1. It was reported that cell adhesion is limited on materials with a surface energy ranging from 20 to 30 mJ/m2. Materials exhibiting a surface free energy over 30 mJ/m2 significantly improve cell–material interaction. In our case, the OL control is close to 30 mJ/m2. For the anodized (OL nano) and composite samples (OL nano Cu), the surface free energy is very high.

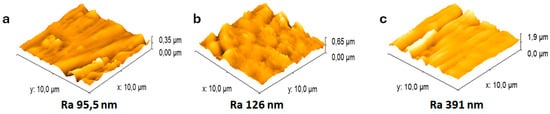

AFM 3D images and Ra values are shown in Figure 3. For the anodized sample, the roughness increases together with the decrease in contact angle. A higher roughness is observed for the Ol nano Cu sample. A comparable trend has been reported in the literature, wherein a reduction in surface roughness (Ol control: 95 nm) is associated with a significant increase in hydrophobicity, as evidenced by a contact angle of 78° [24].

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional AFM images corresponding to (a) control sample, (b) OL nano, and (c) OL nano Cu.

According to the literature [11] the efficiency of antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus pathogens depends on the characteristics of the Cu coatings, including increased surface roughness, enhanced surface free energy, minimal contact angle, and other material characteristics. For the composite coating (OL nano Cu) prepared in this study, these characteristics were met, so we expected good results for their antibacterial activity.

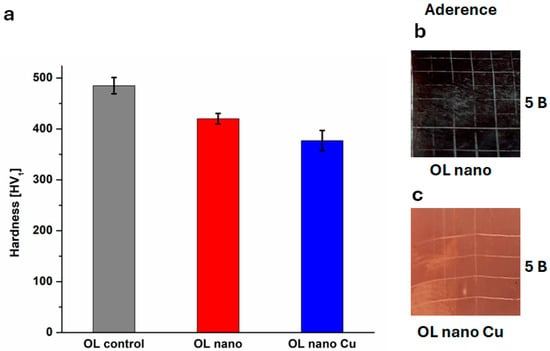

The Vickers Hardness values (HV1) can be seen in Figure 4a. It is acknowledged that HV1 testing may be influenced by substrate effects, especially in thin film systems. Therefore, the reported values should be considered indicative only. Future studies will employ nanoindentation and cross-sectional hardness profiling to better characterize the mechanical response of the composite coating.

Figure 4.

(a) Vickers Hardness for OL control and modified samples; images from adherence test for (b) OL nano and (c) OL nano Cu.

The values for all samples are close, indicating that the techniques used for OL surface modification do not substantially affect the hardness. Ol anodization slightly decreased the hardness from 485 ± 16 HV1 for the OL control to 420 ± 10 HV1 for OL nano. When adding copper layer, the hardness decreases even more, to 377 ± 10 HV1, as copper is a relatively soft metal. These values are comparable with reported values in the literature for anodized steel [54] and the elevated hardness of the composite nanostructured layer is enough to safeguard the surface of steel.

Adhesion test images and results are presented in Figure 4b,c. In earlier work, pulsed copper plating on an OL substrate deposited under comparable conditions demonstrated excellent adhesion (5B) [33]. In this study, for OL nano (sample prior to copper electrodeposition) and OL nano Cu (sample after copper electrodeposition) we obtained excellent adhesion (5B). the adhesion mechanisms between coatings and substrates are categorized into three primary types: mechanical interlocking, chemical bonding, and physical bonding [22]. The substrate roughness and morphology data indicate that a higher roughness value is associated with an increased number of interlocking sites [22], which are also valid for our study, in which the roughness increased after anodization. These results highlight that the predominant adhesion mechanism is mechanical interlocking, facilitated by the increased surface roughness and enhanced morphological features introduced by the anodization process.

3.2. Electrochemical Characterizations

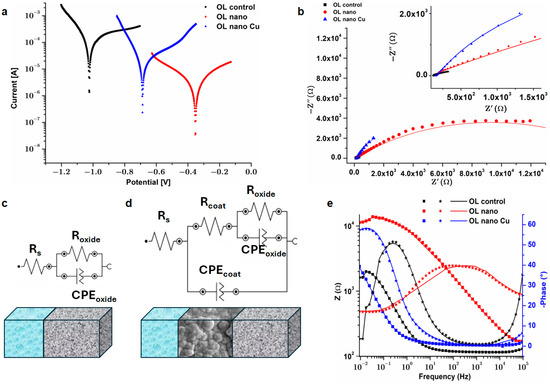

All current values, presented in Figure 5a, correspond to a defined surface area of 0.5 cm2 of the sample exposed to a corrosive environment. The parameters derived from Tafel plots are shown in Table 2. When determining these parameters with Nova 1.11 software, the following data were used: equivalent weight, density and geometric surface area (0.5 cm2). The OL control sample has the highest corrosion rate of 1.35 mm/year, attributable to its most electronegative corrosion potential. The existence of nanostructures on the surface (OL nano) leads to an elevation of the corrosion potential to higher electropositive values, signifying cathodic activity. The corrosion current is an order of magnitude lower than that of the OL control. This results in corrosion prevention efficiency ~95%. These findings align with data from prior investigations [14] indicating that the anodization process of steel forms a corrosion-resistant barrier on the exposed surface of the substrate, attributable to the dense structure of the oxide layer.

Figure 5.

(a) Tafel plot for OL control and modified samples; (b) EIS Nyquist plot; equivalent circuit used to fit EIS data for (c) OL control and (d) OL nano and OL nano Cu; (e) Bode diagram for all tested samples.

Table 2.

Parameters from Tafel plots.

Incorporating a highly conductive copper layer over nanostructures somewhat reduces the corrosion rate and protection efficacy, although to a limited extent. Protection efficiency remains high (~82%), which agrees with observations made in other studies [55] that the inclusion of CuO nanoparticles on the surface of steel enhances corrosion resistance.

Figure 5b provides normalized Nyquist plots for OL control and modified samples, obtained at open circuit potential (OCP). The Nyquist plot has a semicircular shape, which indicates the presence of non-ideal, distorted loops instead of perfect circles, a discrepancy often attributed to the heterogeneous composition and surface roughness of the samples [56]. This indicates the existence of capacitive behavior. The corrosion resistance of a material is generally recognized to increase in proportion to the size of its capacitive loop. Figure 6b indicates that the minimal capacitive loop was seen for the OL control, indicating it had the lowest corrosion resistance. All modified samples have higher capacitive loop compared to the OL control, indicating a better corrosion resistance, in line with the observations from the Tafel plot.

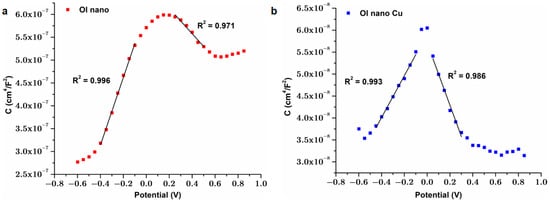

Figure 6.

Mott–Schottky diagrams corresponding to (a) OL nano; (b) OL nano Cu.

The analogous circuit utilized to fit the data is represented in Figure 5c (for OL control) and Figure 5d (for OL nano and OL nano Cu). The circuit used to fit the data was a modified Randles circuit. The right number of time constants for an analogous circuit model was determined using Bode diagrams of impedance spectra (Figure 5e). One-time constant electrical equivalent circuit systems (Figure 5c) worked well for the freshly cleaned steel surface (black symbols and lines in Figure 5e), which showed an asymmetric time constant in the medium-frequency region. The classical Randles circuit model did not fit the anodized samples well. OL nano exhibited an asymmetric curve with a maximum at −50°, indicating two overlapping time constants. To model the impedances of OL nano Cu, at least two time constants are needed (Figure 5d), as indicated by changes in the slope of log10|Z|/log10Frequency in Figure 5e. This indicates a sophisticated protective system comprising various electrochemical reactions [57]. The resistance Rs accounts for the resistance from a 0.9% NaCl corrosive environment (solution resistance between the reference electrode and the working electrode), and it is derived from the impedance assessed in the low-frequency domain of the EIS spectrum. The solution resistance has values around 100 ohms for all samples. For all samples, a resistance (Roxide), in tandem with a constant phase element (CPEoxide), was included to account for the inherent porous oxide layer (inner barrier layers of coating) found on all metal surfaces immediately after immersion in electrolyte and the charge transfer process. It is formed by oxygen reduction and iron oxidation and may be related to the porous nature of the oxide layers [58]. The phase angle for OL control at medium frequency attains 50° and subsequently diminishes to 0° at low frequencies. This suggests that the natural oxide layer is thin [59]. For Ol nano and OL nano Cu, a resistance (Rcoat) was used in parallel with a constant phase element (CPEcoat), to represent the charge transfer through the oxide layer formed during anodization and the oxide coated with Cu, as seen in the SEM pictures (Figure 1b and Figure 2c). The CPEcoat element represents the constant phase associated with oxide film capacitance (adsorbed species and iron oxides–hydroxides), while the Rcoat element represents oxide film resistance and electrolyte inside flaws and pores. This more modified Randles circuit was also used in other studies for steel and modified steel surfaces [1,30].

The electrical parameters obtained by the Nova program are shown in Table 3. The saline solution (NaCl 0.9%) and testing circumstances are consistent (room temperature and light), resulting in an estimated solution resistance of around 100 Ω for all assessed samples.

Table 3.

Parameters from EIS data.

Incorporating CPE can mitigate the irregularities and heterogeneity of the working electrode’s surface [60]. Constants Y0 and N, representing the admittance of an ideal capacitance and an empirical constant, respectively, characterize the Constant Phase Element (CPE). The empirical constants Noxide and Ncoat vary from 0 to 1. The divergence from theoretical capacitance is denoted by the exponential factor N in the CPE equation. When Y0 is equal to R, the CPE exhibits characteristics like those of a pure resistor when N equals 0. Conversely, the CPE functions as an ideal capacitor when N = 1. An elevated ‘N’ number typically signifies an increase in surface irregularity, whereas a reduced ‘N’ value denotes a smoother surface [56]. N = 0.5 is linked to Warburg impedance, indicating diffusion-controlled processes [61]. Given the Noxide, which mostly ranges from close to 0.75 to 0.99, it is reasonable to conclude that the oxide layer for all examined samples exhibits a pseudocapacitive nature. For Ncoat, the value corresponding to the OL nano is close to 0.5, lower compared to the value for OL nano Cu. The CPE magnitude (Ycoat and Yoxide) reflects the structural properties of the adsorbed surface layer, with reduced Y values indicating a denser and more compact layer [61]. It can be seen that all Y values are lower for the OL nano sample compared to OL nano Cu.

Based on EIS measurements, the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) for the coatings was 1.50 μF/cm2 for OL nano and 7160 μF/cm2 for OL nano Cu, suggesting that the latter sample has a higher density of exposed active sites, thereby promoting more efficient electrochemical reactions. The capacitance values were normalized to the geometric area exposed to the electrolyte. The significantly higher capacitance observed for OL nano Cu can be attributed to its increased surface roughness and a larger electroactive surface area resulting from copper incorporation, which enhances charge accumulation at the interface. Comparable Cdl values for copper-coated samples have been reported in other studies, consistent with our findings [62].

The χ2 values, which measure the disagreement between the experimental and fitted data, were on the order of 10−3, indicating an acceptable fit for the circuit.

As was also seen from Tafel, the resistance (Rcoat + Roxide) is higher for OL nano compared to OL nano Cu.

The phase angle in Bode diagram can be ascribed to the correlation of a capacitive time constant associated with dielectric characteristics. An incomplete arc in the Nyquist diagram correlates with the phase angle-log frequency in the Bode diagram at lower frequencies, which is associated with mass transport [63]. Bode plots, impedance modulus vs. frequency (Figure 5e), show, for all frequencies, an increase in impedance after anodization (for OL nano) compared to the OL control. The OL control had the lowest impedance, indicating very limited or effective surface protection. For OL nano Cu, the impedance modulus vs. frequency values are lower compared to OL nano but higher compared to OL, so the copper layers influence is visible in the Bode diagram and agrees with the Tafel plot.

The observed shift in corrosion potential (Ecorr) values reflects the nature of the surface layers. The anodized OL nano sample displayed the most positive potential, consistent with the formation of a protective passive film. In contrast, OL nano Cu also outperformed the control but displayed a slightly more negative Ecorr. This shift is attributed to the nano–copper particles, which enhance long-term corrosion protection by isolating the electrolyte and providing strong barrier properties, as demonstrated by their 81% barrier efficiency. Importantly, this potential shift does not indicate long-term galvanic corrosion. Additional long-duration testing will be conducted in future work.

Although the steel substrate is not explicitly represented in the equivalent circuit, it functions as an electron conductor with a negligible impedance contribution. Therefore, the circuit focuses on modeling the electrochemical behavior of the passive and composite surface layers.

In Figure 6, Mott–Schottky diagrams for modified steel are presented. As can be seen in Figure 6a,b, all plots exhibited, as expected, two distinct regions indicative of space-charge behavior. These characteristics are consistent with those previously reported for passive films formed on iron, stainless steel, and Alloy 600 [43]. The semiconducting behavior is commonly attributed to the duplex structure of the surface oxide layers, comprising an inner region primarily composed of Cr2O3 (and FeO) and an outer region predominantly consisting of Fe2O3. The three-dimensional distribution of these oxide phases significantly influences the electrical properties of the passive film. In the more anodic potential region, the observed positive slope in the Mott–Schottky plot is characteristic of n-type semiconducting behavior, typically associated with Fe2O3. Conversely, the negative slope reflects p-type semiconducting behavior, which is attributed to the presence of Cr2O3 in the inner layer [43,64]. The following values were obtained from the Mott–Schottky analysis: for OL nano ND = 1.22·1019 cm−3, NA = 3.26·1019 cm−3 and for OL nano Cu: ND = 1.89·1018 cm−3, NA = 1.27·1018 cm−3. These values are similar with the ones mentioned in the literature [64]. The physicochemical characteristics of the passive film may be primarily influenced by point defects, including oxygen vacancies, metal interstitials, and metal vacancies, present in high densities (typically 1019–1028 cm−3), which facilitate mass transfer for oxide development [65].

The ND for the OL nano Cu sample showed a donor density exceeding that of OL nano by approximately one order of magnitude; a similar tendency was described in other studies [65], indicating that the concentration of oxygen vacancies in the passive films is augmented by the addition of copper.

The Mott–Schottky analysis revealed important differences in semiconductor behavior between the samples. Notably, the OL nano Cu coating showed that donor density increased by an order of magnitude (ND = 1.89·1019 cm−3) compared to OL nano (ND = 1.22·1018 cm−3). This suggests a higher concentration of oxygen vacancies and electronic carriers in the oxide layer, which may influence both copper ion mobility and redox processes occurring at the surface. Such features can enhance the antibacterial efficacy by promoting ion release and oxidative stress mechanisms. In parallel, they also support corrosion resistance by contributing to passive film formation and electronic stabilization. Therefore, the semiconducting nature of oxide films is likely to play a synergistic role in both corrosion protection and antimicrobial performance.

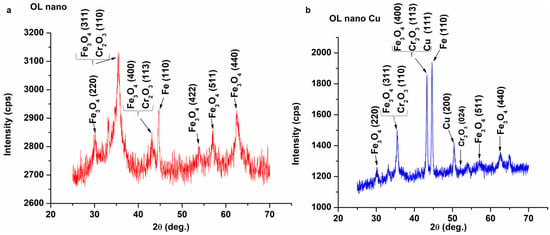

3.3. Surface Characterization Using XRD and XPS

X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed to describe the crystalline structure of the anodized and copper-plated samples. The diffraction patterns of the samples are shown in Figure 7, together with the distinct characteristic peaks in magnetite, chromium oxide, iron, and copper. The peak observed at 45 degrees on both samples corresponds to the (110) reflection of cubic metallic iron from the K 455 steel substrate (ICDD 00−001−1262) [66]. The diffraction peak corresponding to the (110) planes of the hematite (α-Fe2O3) phase, identified at 35 degrees [67], was detected in both samples. Simultaneously, peaks corresponding to the (220), (311), (400), (440), and (511) planes of the magnetite (Fe3O4) phase [67] are depicted in Figure 7a,b. For OL nano sample, (422) planes of the magnetite (Fe3O4) phase are also present. The diffraction peaks at 2θ = 35° and 43° can also be attributed to (1 1 0) and (1 1 3) reticular planes of Cr2O3 [68,69,70], but their overlap with Fe-oxide reflections and the low intensity of chromium oxide signals make XRD identification difficult. This is consistent with either (i) a very low Cr oxide content or (ii) the formation of an amorphous or nanocrystalline Cr-rich passive layer, which would also remain weak or undetectable in XRD.

Figure 7.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns comparing the crystalline phases of: (a) nanoporous iron oxide (OL nano) and (b) copper-coated OL nano–Cu samples.

In the OL nano Cu sample (Figure 7b), diffraction peaks indicative of the (111) and (200) planes of the face-centered cubic (fcc) phase were detected at 2θ = 43.3° and 50.4°, respectively, as was also presented in the literature [27].

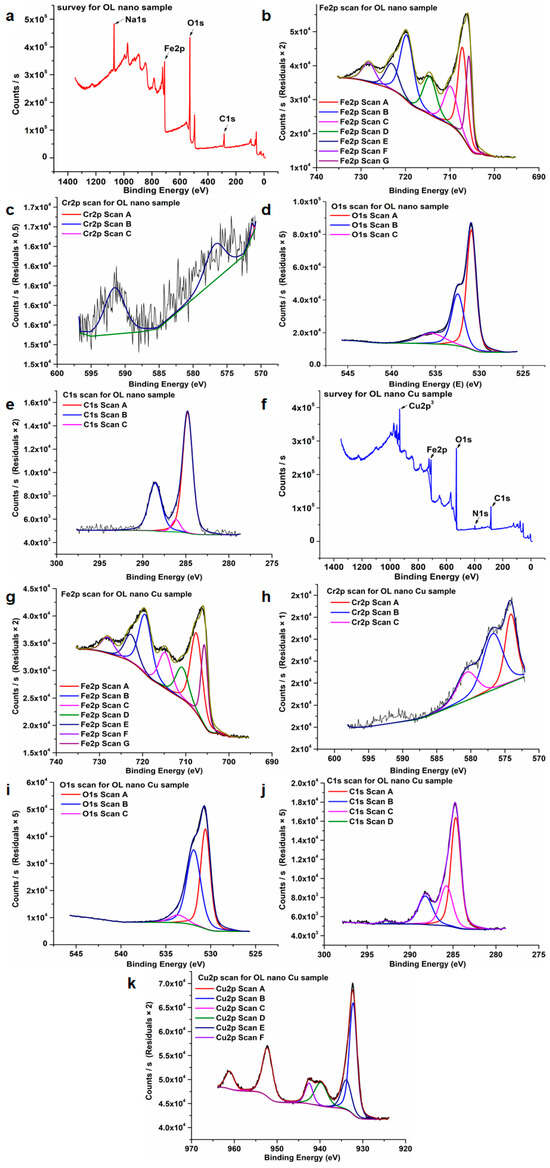

The high-resolution XPS spectra of OL nano and OL nano Cu are presented in Figure 8. For both samples, Fe, Cr, O, and C are shown. For OL nano Cu, the Cu spectrum is also presented. The survey XPS spectrum of the anodized OL nano (Figure 8a) sample exhibited distinct peaks corresponding to Na 1s, Fe 2p, O 1s, and C 1s. The detection of sodium is ascribed to residual Na species originating from the NaOH electrolyte employed during the anodization process. For OL nano Cu (Figure 8f), the survey spectra show peaks corresponding to Cu 2p3, Fe 2p, O 1s, N 1s, and C 1s. N is from the electrolyte solution used for copper plating. Chromium (Cr) was absent from the survey spectra of all samples. The pronounced noise in the Cr spectra (Figure 8c,h) is attributed to the very low chromium content at the surface, combined with the limited probing depth of XPS (~10 nm), which primarily analyzes the outermost nanolayers of the coatings. The pronounced noise in the Cr high-resolution spectra further supports that any surface Cr species are below the detection limit, likely due to their presence as ultrathin, highly dispersed oxides incorporated into the passive layer. Such behavior is well-documented for stainless and low-alloy steels where Cr oxidizes preferentially but forms layers that are too thin or too discontinuous for reliable XPS detection.

Figure 8.

(a,f) Survey spectrum of XPS corresponding to OL nano and OL nano Cu samples. High-resolution spectra for: (b,g) Fe 2p; (c,h) Cr 2p; (d,i) O 1s; (e,j) C 1s, and (k) Cu 2p. Black line represents background.

In the Fe area, the peak at 723 eV is attributed to Fe(III)2p1/2, whereas the peak at 714 eV (Figure 8b) or 711 eV (Figure 8g) corresponds to Fe(III)2p3/2, accompanied by a satellite peak at 719 eV. These peaks are indicative of hematite, α-Fe2O3 or Fe2O3 [66,71]. Because the satellite position is at ~719 eV, this denotes the Fe3+ oxidation state [72]. The peak at the binding energy of 709 eV (Figure 8b) or 708 eV (Figure 8g) corresponds to metallic iron, Fe0 [71].

The XPS spectra of the O 1s region exhibit peaks at approximately 530 and 531 eV (Figure 8i) and at 532 eV (Figure 8d). These peaks correspond to oxygen species in different chemical states, including lattice oxygen (O2−) associated with iron oxides such as α-Fe2O3 or Fe2O3, as well as oxygen in chromium oxides (Cr2O3) and metal-bound hydroxide groups (M–OH) [1,52,66].

A peak appears in the C 1s spectra at roughly 285 eV (Figure 8e,j), signifying the presence of carbon–carbon (C–C) and carbon–hydrogen (C–H) bonds. A peak at 288.9 eV is found, perhaps corresponding to O=C–O and/or CO3 bonds [52].

The presence of metallic Cu on the Ol nano Cu surface (Figure 8k) is shown by the core level Cu 2p3 XPS peak at a binding energy of 932 eV [73]. The signal at 934 eV and 954 eV is presumably ascribed to copper compounds (Cu2+ species), including CuO [74].

The XPS and XRD findings are consistent with the Mott–Schottky behavior and confirm the anodic formation of iron and chromium oxides. The deposition of copper on the surface of the anodized sample is also confirmed.

3.4. Antibacterial Activity

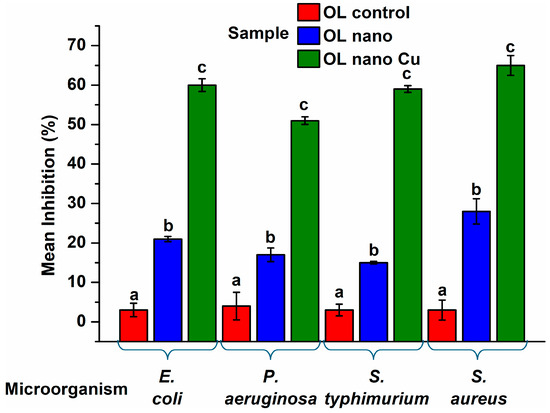

The copper-functionalized anodized surface (OL nano Cu) exhibited a clear and consistent antibacterial effect (see Figure 9) against all tested bacterial strains, with inhibition levels between 51% and 65% after 24 h exposure in liquid medium. This outcome reflects a notable reduction in bacterial viability, emphasizing the potential of copper-modified anodized surfaces in providing broad-spectrum antimicrobial protection. Among the four strains evaluated, Staphylococcus aureus showed the highest sensitivity, with a 65% inhibition rate. This observation aligns with prior studies reporting the heightened vulnerability of Gram-positive bacteria to copper-induced toxicity because of copper ion release [75,76]. The effectiveness may be explained by the structural characteristics of S. aureus, such as the absence of an outer membrane, allowing copper ions to easily disrupt membrane functions. There are studies reporting higher antibacterial efficiency for anodized steel against E. coli and S. aureus (approximately 78 and 92%), but they used non-thermal plasma treatment [52] which is a method involving higher operation costs [77].

Figure 9.

Antibacterial inhibition of the tested surfaces (OL control, OL nano, and OL nano Cu) against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, and Staphylococcus aureus after 24 h exposure in liquid medium. Bars represent mean inhibition percentages ± standard deviation. Statistical significance between treatments was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05); different letters indicate significant differences.

In contrast, Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibited the lowest inhibition (51%). Although this value remains biologically significant, it likely reflects the innate resistance mechanisms of this pathogen. Known for its thick outer membrane, robust efflux systems, and adaptive stress responses, P. aeruginosa can often withstand various antimicrobial strategies, including metal exposure [78]. However, Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, both Gram-negative enteric bacteria, demonstrated intermediate inhibition levels (60% and 59%, respectively). Literature studies showed that Gram-negative bacteria have increased resistance to a wide range of damaging agents, such as antibiotics, digestive enzymes, detergents, heavy metals, and various pigments. Their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) layer acts as a protective barrier that helps capture and neutralize these substances [76]. Although the 24 h inhibition assay indicated a ~60% reduction in bacterial growth, the corresponding CFU decrease remained below 1-log, which is consistent with early-stage copper-based surface screenings that primarily reflect growth inhibition rather than full bactericidal activity during short exposure periods. Other studies have reported antibacterial efficiencies comparable to our findings for copper coatings deposited via Ionized Jet Deposition. In those reports, the most pronounced effect was observed for Cu–W coatings against S. aureus, showing a 50% reduction in growth relative to the control, followed by P. aeruginosa and E. faecalis, with 43–45% inhibition, and E. coli, with 36% inhibition. For Cu–P coatings, the strongest antibacterial effect was noted against P. aeruginosa, with a 54% growth suppression rate [79]. Also, the antibacterial efficacy of copper coatings produced via micro-arc oxidation on pure magnesium (Cu-0.5 and Cu-1) was comparable, suppressing the development of S. aureus by up to 50% [80].

The anodized surface without copper (OL nano) also showed moderate antibacterial activity, particularly against S. aureus (28%) and E. coli (21%). These effects suggest that the topographical changes induced through anodization may alter bacterial adhesion and viability to some extent. However, the observed inhibition was considerably lower than that of the copper-functionalized surfaces. The OL control surfaces had minimal impact, with inhibition rates between 2 and 4%, reinforcing the need for active surface modification to achieve measurable antimicrobial effects.

This trend was further supported by SEM imaging. The OL nano surface revealed a moderately porous, granular topography consistent with the formation of an oxide layer. These features increase the surface area and may marginally affect bacterial attachment, though without antimicrobial additives, like copper, their impact remains limited [81,82]. On the other hand, the OL nano Cu surface displayed a more heterogeneous texture, with localized clusters, pits, and protrusions. These characteristics are likely to result from copper deposition through pulsed treatment and contribute to increased roughness, improved ion release, and amplified bactericidal activity [83,84]. Such structural complexity may also enhance mechanical stress on bacterial cells, further aiding their inactivation.

The quantitative findings were statistically confirmed through one-way ANOVA, which indicated significant differences among the three surface types for each microorganism (p < 0.001). Tukey’s HSD post hoc test identified distinct groupings for all treatment pairs. Composite sample OL nano Cu consistently outperformed both untreated and anodized-only variants, with average inhibition gains of over 55% relative to OL control and at least 30–40% over OL nano surfaces. These outcomes were consistent across both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains, affirming the central role of copper in enhancing antimicrobial performance.

The bar chart (Figure 9) provided illustrates these differences in inhibition rates across the tested bacterial strains. Mean values and standard deviations are shown for each treatment group, with statistical significance denoted through lettering (a, b, c) as per Tukey’s test. This visual representation reinforces the experimental conclusions, underscoring the effectiveness of combining anodization with copper functionalization in designing antimicrobial surfaces.

One-way ANOVA showed highly significant differences among the three surface treatments for all tested microorganisms (E. coli: F(2,6) = 1981.05, p < 0.001; P. aeruginosa: F(2,6) = 715.83, p < 0.001; S. typhimurium: F(2,6) = 1144.85, p < 0.001; S. aureus: F(2,6) = 411.47, p < 0.001). Tukey’s HSD test confirmed pairwise significance (p < 0.05). For each bacterium, the one-way ANOVA included three treatments (df_between = 2) and triplicate measurements per treatment (df_within = 6). ANOVA results (F values and degrees of freedom) are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

4. Conclusions

A composite coating was developed and characterized with respect to its microstructure, surface morphology, and electrochemical behavior. The steel substrate was initially anodized in a concentrated sodium hydroxide (NaOH) electrolyte to form a nanostructured surface layer, thereby increasing the number of interlocking sites and enhancing the adhesion of the subsequently applied copper coating. EDX results showed that the nanoporous anodic oxidation layer formed on the steel surface mostly included iron oxides. SEM and EDX analyses indicate that the copper coating deposited via pulsed electrodeposition uniformly covered the nanoporous layer. The Cu-coated steel exhibited a reduced water contact angle and notably high surface free energy, consistent with findings reported in other studies. This composite coating, characterized by enhanced roughness and improved hardness, sufficiently protects the steel surface in a corrosive environment (NaCl 0.9%). Mott–Schottky, XRD, and XPS revealed that the oxides formed on the surface during anodization are iron and chromium oxides. XRD and XPS confirmed copper electrodeposition.

Moreover, the semiconducting behavior of the coatings, especially the increased donor density in OL nano Cu, appears to support both antibacterial activity and corrosion resistance. In vitro experiments demonstrated that steel coated with nanostructured anodic oxide-copper could effectively kill Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhimurium.

The proposed approach offers a novel route to engineer multifunctional surfaces, with both protective and antimicrobial features, using industrially compatible methods.

Although further investigations are necessary, these preliminary results suggest that the proposed steel coating method holds promise as a cost-effective solution in the ongoing effort to prevent the proliferation and transmission of pathogens. While the current method is not immediately environmentally scalable, it serves as a conceptual platform for optimizing multifunctional coatings. Transitioning to safer, cyanide-free electrolytes is essential for practical implementation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcs10010023/s1, Figure S1: EDX spectrum [85]; Table S1: Summary of one-way ANOVA results for inhibition percentages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.C., C.P. and C.D.; methodology, C.A.C. and C.D.; validation, C.A.C., C.U., C.P. and C.D.; investigation, C.A.C., C.U., O.B., E.I.B., C.P. and C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.C., C.U. and C.D.; writing—review and editing, visualization, C.A.C., C.U., C.P. and C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Units |

| CPE | Constant phase element |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| EG | Ethylene glycol |

| HSD | Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference |

| NA | Acceptor density |

| ND | Donor density |

| OL | Steel |

| P. aeruginosa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| S. typhimurium | Salmonella typhimurium |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

References

- Herath, I.; Davies, J.; Will, G.; Tran, P.A.; Velic, A.; Sarvghad, M.; Islam, M.; Paritala, P.K.; Jaggessar, A.; Schuetz, M.; et al. Anodization of medical grade stainless steel for improved corrosion resistance and nanostructure formation targeting biomedical applications. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 416, 140274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Schino, A. Manufacturing and Applications of Stainless Steels. Metals 2020, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.B.; Wang, Z.B.; Zhang, B.; Luo, Z.P.; Lu, J.; Lu, K. Enhanced mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of 316L stainless steel by pre-forming a gradient nanostructured surface layer and annealing. Acta Mater. 2021, 208, 116773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, L. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Properties of Tool Steel. ACTA Mater. Transylvanica (EN) 2023, 6, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BÖHLER. Available online: https://www.bohler-edelstahl.com/en/products/k455-2/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Erdogan, Y.K.; Ercan, B. Anodized Nanostructured 316L Stainless Steel Enhances Osteoblast Functions and Exhibits Anti-Fouling Properties. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelkemeier, K.; Mücke, C.; Hoyer, K.P.; Schaper, M. Anodizing of electrolytically galvanized steel surfaces for improved interface properties in fiber metal laminates. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2019, 2, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, N.; Abdulkareem, M.; Anoon, I.; Al-Amiery, A. Improvement of corrosion resistance of 316L stainless steel substrate with a composite coating of biopolymer produced by electrophoretic deposition. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2023, 12, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Ge, Y.; Zheng, Z. Mussel adhesive protein inspired functionalization of steel fibers for better performance of steel fibers reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 436, 136887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacotich, N.; Din, R.U.; Sloth, J.J.; Møller, P.; Gram, L. An electroplated copper–silver alloy as antibacterial coating on stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 345, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadishettar, N.; Bhat K, U.; Bhat Panemangalore, D. Coating Technologies for Copper Based Antimicrobial Active Surfaces: A Perspective Review. Metals 2021, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, N.; Ashengroph, M.; Sharifi, A.; Zorab, M.M. Eco-friendly synthesis of copper nanoparticles by using Ralstonia sp. and their antibacterial, anti-biofilm, and antivirulence activities. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 42, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhao, W.; Lan, X. Revealing the antibacterial mechanism of copper surfaces with controllable microstructures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 395, 125911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobi, A.; Sattar, N.; Jaber, N. A study on stainless steel 316l utilizing single- step anodization and a dc sputtering plasma of silver coating to improve corrosion resistance. Acad. J. Manuf. Eng. 2023, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, Y.K.; Mutlu, P.; Ercan, B. Nanostructured 316L Stainless Steel Stent Surfaces Improve Corrosion Resistance, and Enhance Endothelization and Hemocompatibility. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, 2400968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshima, S.; Yanagishita, T. Preparation of Large-Area Anodic Oxide Films with Regularly Arranged Pores by Two-Step Anodization of Stainless Steel Substrates and Application to Superhydrophobic and Superoleophobic Surfaces. Langmuir 2025, 41, 9072–9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaglia, S.; Morellá-Aucejo, Á.; Ruiz-Rico, M.; Sancenón, F.; Villaescusa, L.A.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Marcos, M.D.; Bernardos, A. Antimicrobial Surfaces: Stainless Steel Functionalized with the Essential Oil Component Vanillin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Liang, T.; Jin, S.; Song, Z.; Dan, X.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wang, M.; Du, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Exceptional strength and antibacterial durability in hierarchically structured Cu-bearing 316L stainless steel through additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 5273–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.; Kanematsu, H.; Nakamoto, M.; Miyabayashi, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Tanaka, T. Corrosion and antibacterial performance of 316L stainless steel with copper patterns by super-spread wetting of liquid copper. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 462, 129496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, P.; Gui, H.; Wei, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Copper-based nanomaterials for the treatment of bacteria-infected wounds: Material classification, strategies and mechanisms. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 522, 216205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, T.; Mao, F.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, X.; Zhai, C.; Zhang, H. Engineering copper and copper-based materials for a post-antibiotic era. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1644362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadishettar, N.; Udaya Bhat, K. Effect of acid pickling treatment of stainless steel substrate on adhesion strength of electrodeposited copper coatings using non-cyanide electrolyte. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2023, 127, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Ren, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, X.; Yang, K.; Dai, K. Antibacterial effect of a copper-containing titanium alloy against implant-associated infection induced by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Biomater. 2021, 119, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Xi, T.; Zhao, J.; Yang, K. Surface Roughness of Cu-Bearing Stainless Steel Affects Its Contact-Killing Efficiency by Mediating the Interfacial Interaction with Bacteria. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, L.; Wang, I.L.; Tam, L.M.; Lo, K.H.; Li, R.; Chan, C.W.; Cristino, V.A.M.; Kwok, C.T. In-situ surface modification and bulk alloying of anti-bacterial Cu-bearing stainless steel using selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2025, 254, 114110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Elguindi, J.; Rensing, C.; Ravishankar, S. Antimicrobial activity of different copper alloy surfaces against copper resistant and sensitive Salmonella enterica. Food Microbiol. 2012, 30, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aissou, T.; Jann, J.; Faucheux, N.; Fortier, L.-C.; Braidy, N.; Veilleux, J. Suspension plasma sprayed copper-graphene coatings for improved antibacterial properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 639, 158204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, M.; Benčina, M.; Levičnik, E.; Rawat, N.; Iglič, A.; Junkar, I. Strategies for Improving Antimicrobial Properties of Stainless Steel. Materials 2020, 13, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Hodgson, M.; Gao, W. Antibacterial anodic aluminium oxide-copper coatings on aluminium alloys: Preparation and long-term antibacterial performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 141873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.S.; Cinca, N.; Dosta, S.; Cano, I.G.; Guilemany, J.M.; Caires, C.S.A.; Lima, A.R.; Silva, C.M.; Oliveira, S.L.; Caires, A.R.L.; et al. Corrosion resistance and antibacterial properties of copper coating deposited by cold gas spray. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 361, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Hu, J.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; Xue, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Hou, G.; Wu, B.; Tang, Y.; et al. Effect of pulse electrodeposition process on the microstructure and properties of electrolytic copper foil as anode current collectors. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 528, 146278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, L.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y.-G.; Zheng, D.-L.; Feng, Y. Antimicrobial Properties of Metal Nanoparticles and Their Oxide Materials and Their Applications in Oral Biology. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 2063265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, C.-A.; Dumitriu, C.; Vizireanu, S.; Bita, B.; Nicola, I.-M.; Dinescu, G.; Pirvu, C. Influence of Carbon Nanowalls Interlayer on Copper Deposition. Coatings 2021, 11, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Mendon, R.R.; Soven, S.; Das, S.; Mallik, A. Copper Electrodeposition from a Non-cyanide Glycinate Alkaline Bath under Varying Potential, Bath Concentration, and Temperature: An Impedance Analysis. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 27961–27976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pary, P.; Bengoa, L.N.; Seré, P.R.; Egli, W.A. New Cyanide-Free Alkaline Electrolyte for the Electrodeposition of Cu-Zn Alloys Using Glutamate as Complexing Agent. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, D52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, R. Synergistic effect of additives on electrodeposition of copper from cyanide-free electrolytes and its structural and morphological characteristics. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, C.; Dumitriu, C.; Popescu, S.; Enculescu, M.; Tofan, V.; Popescu, M.; Pirvu, C. Enhancing antimicrobial activity of TiO2/Ti by torularhodin bioinspired surface modification. Bioelectrochemistry 2016, 107, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, C.; Ungureanu, C.; Popescu, S.; Tofan, V.; Popescu, M.; Pirvu, C. Ti surface modification with a natural antioxidant and antimicrobial agent. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 276, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3359-23; Standard Test Methods for Rating Adhesion by Tape Test. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Duta, M.; Ionita, D.; Prodana, M. Protection Efficiency of a New Complex Hybrid Coating on Ti, Having Titania Nanotubes, Carbon Nanotubes and Hydroxyapatite. Univ. Politeh. Buchar. Sci. Bull. Ser. B-Chem. Mater. Sci. 2016, 78, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.A.; Cheng, Y.F. Micro-electrochemical characterization and Mott–Schottky analysis of corrosion of welded X70 pipeline steel in carbonate/bicarbonate solution. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 55, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lan, A.; Jin, X.; Yang, H.; Qiao, J. Comparison of electrochemical behaviour between La-free and La-containing CrMnFeNi HEA by Mott–Schottky analysis and EIS measurements. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveira, L.V.; Montemor, M.F.; Da Cunha Belo, M.; Ferreira, M.G.; Dick, L.F.P. Influence of incorporated Mo and Nb on the Mott–Schottky behaviour of anodic films formed on AISI 304L. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2813–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Yang, C.; Shen, M.; Zhang, X.; Xi, T.; Yin, L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; et al. Corrosion resistance of Cu-bearing 316L stainless steel tuned by various passivation potentials. Surf. Interface Anal. 2021, 53, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, J.; Farny, N.G.; Haddock-Angelli, T.; Selvarajah, V.; Baldwin, G.S.; Buckley-Taylor, R.; Gershater, M.; Kiga, D.; Marken, J.; Sanchania, V.; et al. Robust estimation of bacterial cell count from optical density. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, T.J. Methods for screening and evaluation of antimicrobial activity: A review of protocols, advantages, and limitations. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 14, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Duffy, B.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Stobie, N.; McHale, P. Enhancement of the antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles using β-cyclodextrin as a capping agent. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2010, 36, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Zhang, X.; Wu, A.; Sheng, K.; Lin, H. Controlling the thickness and composition of stainless steel surface oxide film for anodic sulfide removal. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 136076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Kirubasankar, B.; Mathew, A.M.; Narayanasamy, M.; Yan, C.; Angaiah, S. Influence of pulse reverse current parameters on electrodeposition of copper-graphene nanocomposite coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 5, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivshin, Y.V.; Shaikhutdinova, F.N.; Sysoev, V.A. Electrodeposition of Copper on Mild Steel: Peculiarities of the Process. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2018, 54, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Sengupta, S.; Das, S.; Saha, P.; Das, K. Synthesis and characterization of MWCNT reinforced nano-crystalline copper coating from a highly basic bath through pulsed electrodeposition. Surf. Interfaces 2017, 9, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benčina, M.; Rawat, N.; Paul, D.; Kovač, J.; Iglič, A.; Junkar, I. Surface Modification of Stainless Steel for Enhanced Antibacterial Activity. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 13361–13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, W.; Liao, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, G.; Chen, J. Constructing nanostructured functional film on EH40 steel surface for anti-adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, P.-C.; Chen, C.-W.; Tsai, F.-T.; Lin, C.-K.; Chen, C.-C. Hard Anodization Film on Carbon Steel Surface by Thermal Spray and Anodization Methods. Materials 2021, 14, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut, G.; Beköz Üllen, N.; Karakuş, S.; Toruntay, C. Enhancing antibacterial and anticorrosive properties of 316L stainless steel with nanocoating of copper oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 308, 128265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, S.; Shalabi, K.; Yousef, T.A.; Alsulaim, G.M.; Alaasar, M.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Al-Janabi, A.S.M. Novel organoselenides as efficient corrosion inhibitors for N80 steel in a 3.5 wt% sodium chloride solution. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 172, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevani, A.; Lamprou, E.; Mavropoulos, A.; Stergioudi, F.; Michailidis, N.; Tsoulfaidis, I. Modeling and Analysis of Corrosion of Aluminium Alloy 6060 Using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). Alloys 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, L.H.; Anastasiou, E.; Virtanen, S. Corrosion behavior of anodic self-ordered porous oxide layers on stainless steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 021507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrescu, I.; Dumitriu, C.; Totea, G.; Nica, C.I.; Dinischiotu, A.; Ionita, D. Zwitterionic Cysteine Drug Coating Influence in Functionalization of Implantable Ti50Zr Alloy for Antibacterial, Biocompatibility and Stability Properties. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, M.; Saxena, A.; Kaur, J. Application of expired Febuxostat drug as an effective corrosion inhibitor for steel in acidic medium: Experimental and theoretical studies. Chem. Data Collect. 2024, 52, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, M.A.; Musa, A.; Muhammad, Z.; Haruna, K.; Saleh, T.A. Assessment of inhibition performance of expired chloroquine phosphate on 304 L stainless steel corrosion in hydrochloric acid solution: An experimental and computational study. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 10, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Lang, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; Zou, J.; Li, Q.; Hu, W.; Lin, H. Construction of a reversible-cycling bifunctional electrocatalyst CoP2@Co(CO3)0.5OH/Cu/NF with Mott–Schottky structure for overall water splitting. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 4654–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikani, N.; Pu, J.H.; Cooke, K. Analytical modelling and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to evaluate influence of corrosion product on solution resistance. Powder Technol. 2024, 433, 119252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, X.; Du, C. Properties of passive film formed on 316L/2205 stainless steel by Mott-Schottky theory and constant current polarization method. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2009, 54, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]