1. Introduction

Traditional construction materials, particularly ordinary Portland cement (OPC), are associated with high CO

2 emissions that raise significant environmental concerns. Concrete is the second most utilized substance globally after water, with annual consumption exceeding 30 billion tons. The production of OPC emits approximately 630–800 kg of CO

2 per ton, depending on the fuel source and the decarbonation of limestone required to form clinker phases such as C

3S and C

2S [

1]. Consequently, the search for alternative binders that avoid the energy-intensive clinkerization process has become a major research focus [

2].

Fly ash-based geopolymers have emerged as one of the most promising alternatives, using industrial by-products such as fly ash to reduce energy demand and minimize carbon footprints. These aluminosilicate binders are formed by alkaline activation, producing three-dimensional inorganic polymer networks [

3]. Geopolymers are valued for their high mechanical strength, low shrinkage, thermal stability, and fire resistance [

4]. More recently, they have also gained attention as specialized binders for 3D printing, due to their rapid setting and early strength development [

5]. However, widespread implementation has been hindered by the reliance on commercial alkaline activators, most notably sodium silicate (SSC). These activators are not only costly but also associated with additional CO

2 emissions that offset some of the sustainability benefits of geopolymers.

Rapid geopolymerization reactions take place when natural or artificial alumino-silicate precursors such as Fly ash, Ground Granulated blast Furnace Slag (GGBS), red mud, volcanic ash, calcined clays, etc., react with alkaline solutions such as NaOH (sodium hydroxide), KOH (potassium hydroxide), or a mixture of these hydroxide solutions and their corresponding silicate solutions [

6]. Hydroxide activators promote crystallinity in geopolymers by dissolving aluminosilicate precursors, thereby increasing the availability of aluminum and silicon ions necessary for the formation of crystalline structures [

7,

8]. Geopolymers activated with NaOH demonstrate enhanced resistance to acids and sulfates and improved thermal stability and mechanical strength [

9]. Silicate-based activators, such as sodium silicate (Na

2SiO

3) and potassium silicate (K

2SiO

3), introduce additional silicate species that create a more cross-linked amorphous network, leading to higher ductility and improved chemical resistance [

10]. Binary combinations of hydroxides and silicates balance these effects, yielding denser and more homogeneous microstructures [

11]. Sodium-based activators are generally more effective than potassium-based ones, producing higher compressive strength and a refined pore structure [

12]. However, sodium silicate—the most widely used activator—has critical drawbacks.

Alkaline activators for geopolymers are commonly classified as hydroxide- or silicate-based systems using sodium or potassium cations. Hydroxide activators promote rapid precursor dissolution but often lead to lower polymerization and strength, whereas silicate-based activators provide additional reactive silica, resulting in more cross-linked gel networks and improved mechanical performance. Sodium-based activators generally outperform potassium-based systems due to their smaller ionic radius and more efficient gel formation. However, commercial sodium silicate is energy-intensive and costly to produce, motivating the development of waste-derived alternatives such as silica fume-derived sodium silicate. In the conventional fusion process, sodium carbonate (Na

2CO

3) and quartz (SiO

2) are calcined at 1400–1500 °C [

13,

14], then dissolved in water and filtered to form the product [

15]. Hydrothermal synthesis requires lower temperatures (225–245 °C) but involves high-pressure autoclaves (27–32 bar), reducing overall energy efficiency [

16]. Both methods result in significant embodied energy and CO

2 emissions, undermining the sustainability of sodium silicate-activated systems. Recent cost assessments of alkali-activated concretes (AACs) suggest large variability, with costs ranging from 70.67 to 114.78 CAD/m

3, in some cases even higher than OPC-based concrete [

17]. Thus, replacing or reducing commercial sodium silicate in geopolymers is essential for advancing economic and environmental viability.

In response, researchers have explored alternative sources of reactive silica to synthesize sodium silicate or sodium silicate alternatives (SSA). Rice husk ash (RHA) and silica fume (SF), both abundant industrial by-products, have shown promise. Tong et al. [

14] used RHA to synthesize sodium silicate for alkali-activated binders. Sun et al. [

18] evaluated slag activated with SF-derived sodium silicate, reporting improved rheology due to the “ball-bearing” effect of undissolved particles. Cheng et al. [

19] demonstrated that silica fume–derived activators reduced production costs and CO

2 emissions when used in fly ash binders. Similarly, Billong et al. [

6,

20], Oti et al. [

21] and Adeleke et al. [

22] confirmed that RHA- and SF-derived sodium silicate can achieve comparable or superior strength and durability relative to commercial sodium silicate. These findings suggest that SSA can reduce reliance on conventional SSC, but systematic evaluations integrating mechanical performance, microstructural analysis, and sustainability metrics remain limited.

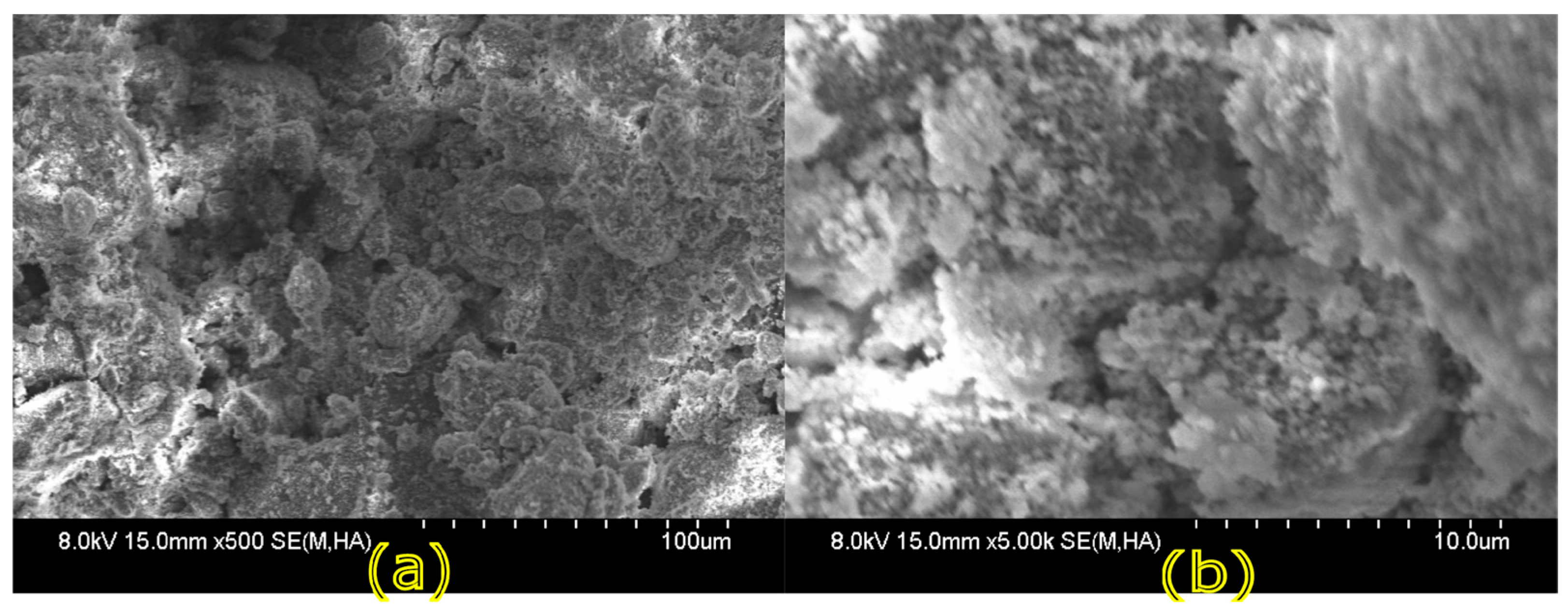

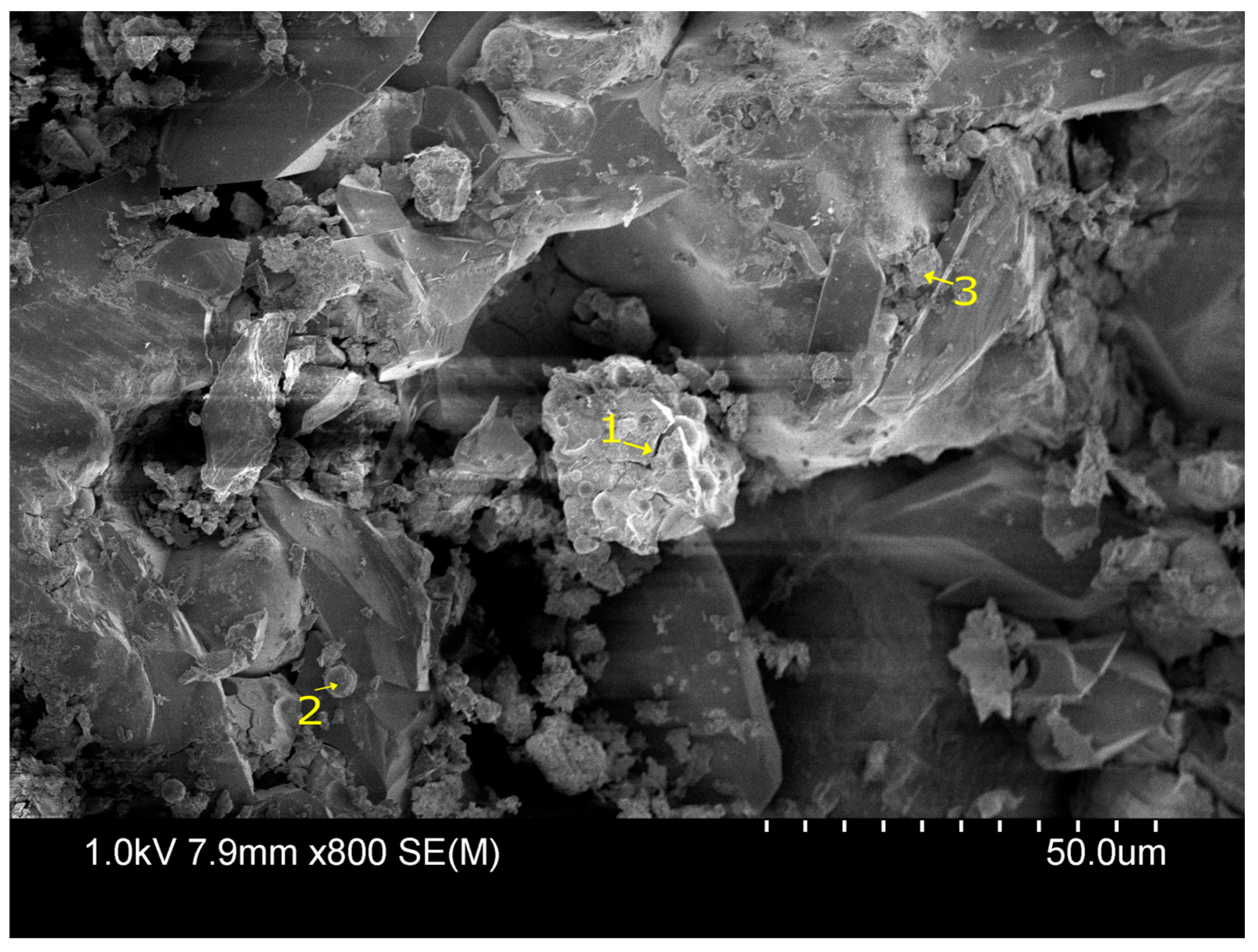

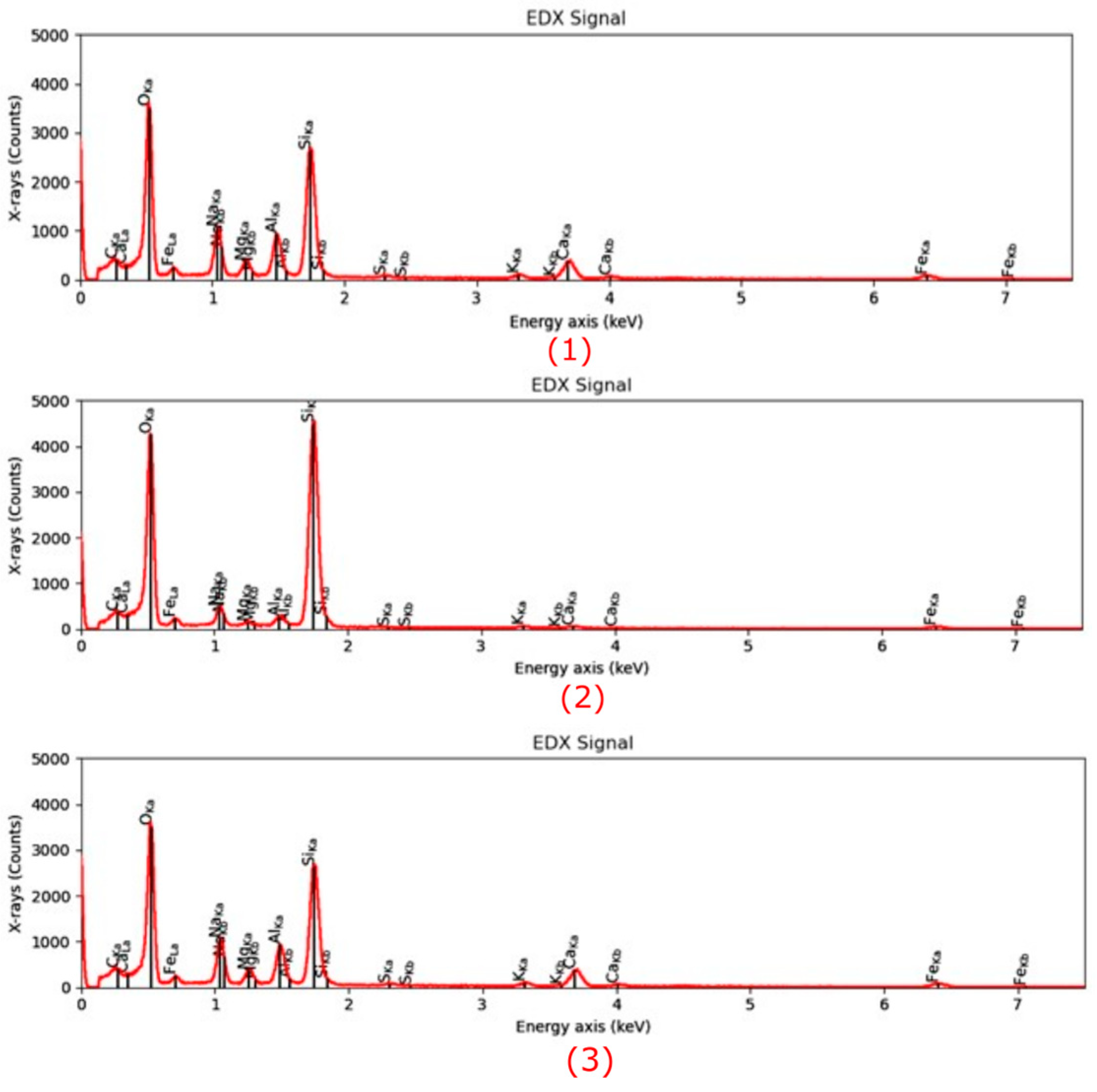

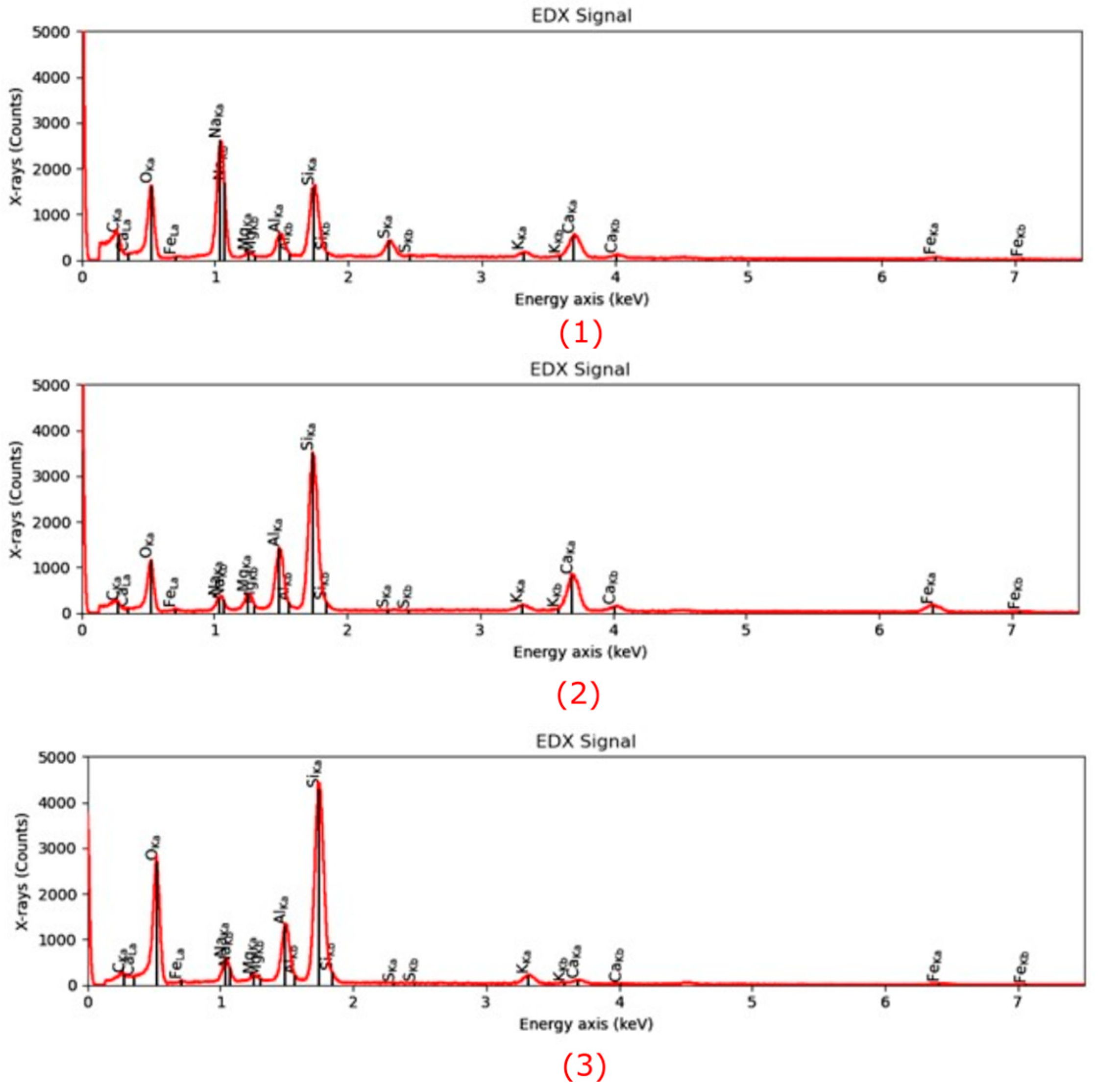

Microstructural characterization is critical for understanding geopolymer performance and durability. Techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) reveal features such as gel morphology, unreacted particles, porosity, and elemental distributions [

23]. Studies have shown that dense matrices with sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) and calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) gels correlate with enhanced strength and reduced permeability [

24]. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) also provides insights into reaction mechanisms, with characteristic band shifts linked to polycondensation and network formation [

25]. By correlating these microstructural features with mechanical and sustainability outcomes, the practicality of SSA-based binders can be better established.

Recent studies have explored diverse activation strategies for low-carbon binders, including nano-silica-enhanced alkali activation, calcined clay activation, and waste-derived silicates. Sodium-based activators remain the most effective due to their high dissolution capacity, whereas potassium-based activators often exhibit rapid viscosity increase and less efficient gel formation [

26]. Commercial sodium silicate, while effective, is energy-intensive to produce. Silica fume-derived sodium silicate offers a low-cost, low-emission alternative with high reactive SiO

2 availability. Previous research has shown that nano-silica and natural pozzolans can significantly enhance geopolymerization [

27]. While prior studies have synthesized sodium silicate alternatives (SSA) from RHA, SF, and other by-products, most have examined either mechanical performance or chemical reactivity in isolation. Few have provided an integrated evaluation of mechanical properties, microstructural development, and sustainability. In this study, fly ash-based geopolymer mortars were activated with silica fume-derived sodium silicate (SSA) combined with NaOH, and their performance was benchmarked against commercial sodium silicate (SSC). To provide broader context, potassium-based activators (CK and AK) were also included, as KOH is locally used in some regions due to cost, availability, and lower hygroscopicity. Although these mixes underperformed, they offer useful contrasts that inform the selection of activators. The scope of this work includes mechanical testing, fresh property assessment, and sustainability analysis supported by new benchmarking indices for cost (Ic) and CO

2 efficiency (Efc). Microstructural and chemical transformations were examined using SEM, EDX, and ATR-FTIR to establish links between binder chemistry, strength development, and environmental impact. Together, these contributions aim to demonstrate SSA’s potential as a sustainable, cost-effective, and technically reliable alternative to SSC for construction applications.

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrates the effectiveness of silica fume-derived sodium silicate alternative (SSA) as an activator for fly ash-based geopolymer mortar through mechanical testing and microstructural analysis using SEM, EDX, and ATR-FTIR. Comprehensive mechanical testing, microstructural characterization, and cost analysis confirmed SSA as a viable, cost-effective, and sustainable alternative for geopolymer applications.

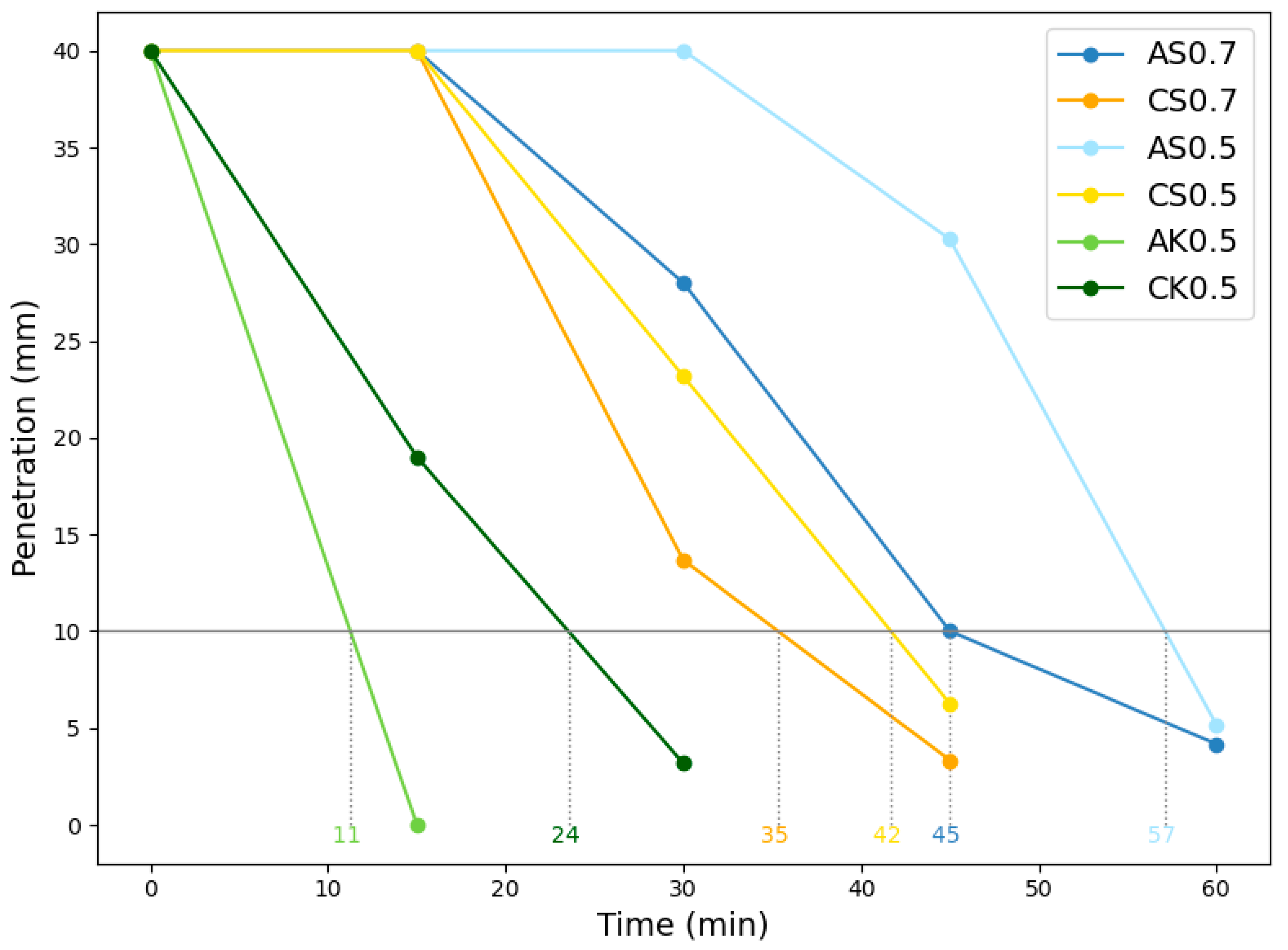

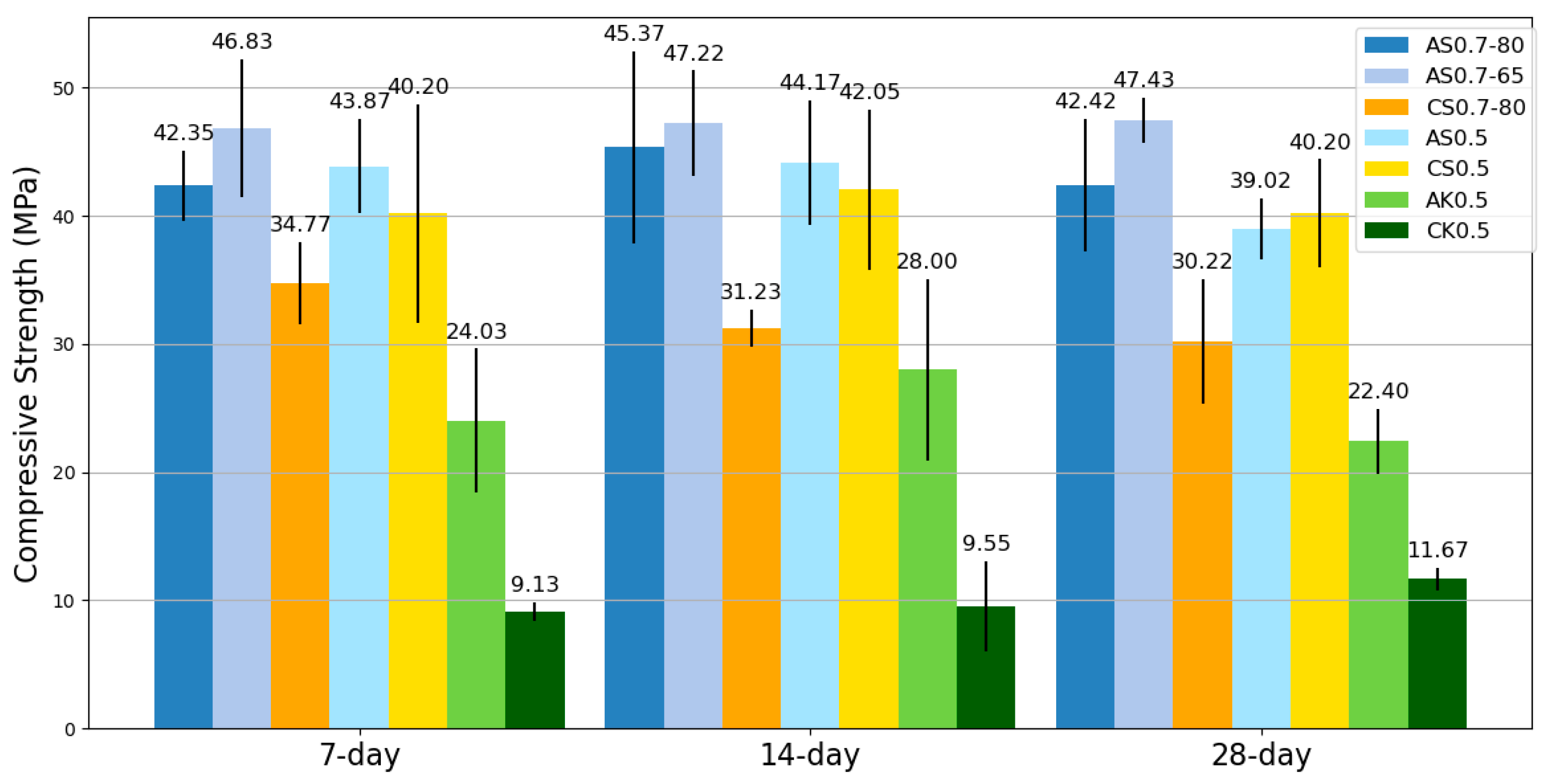

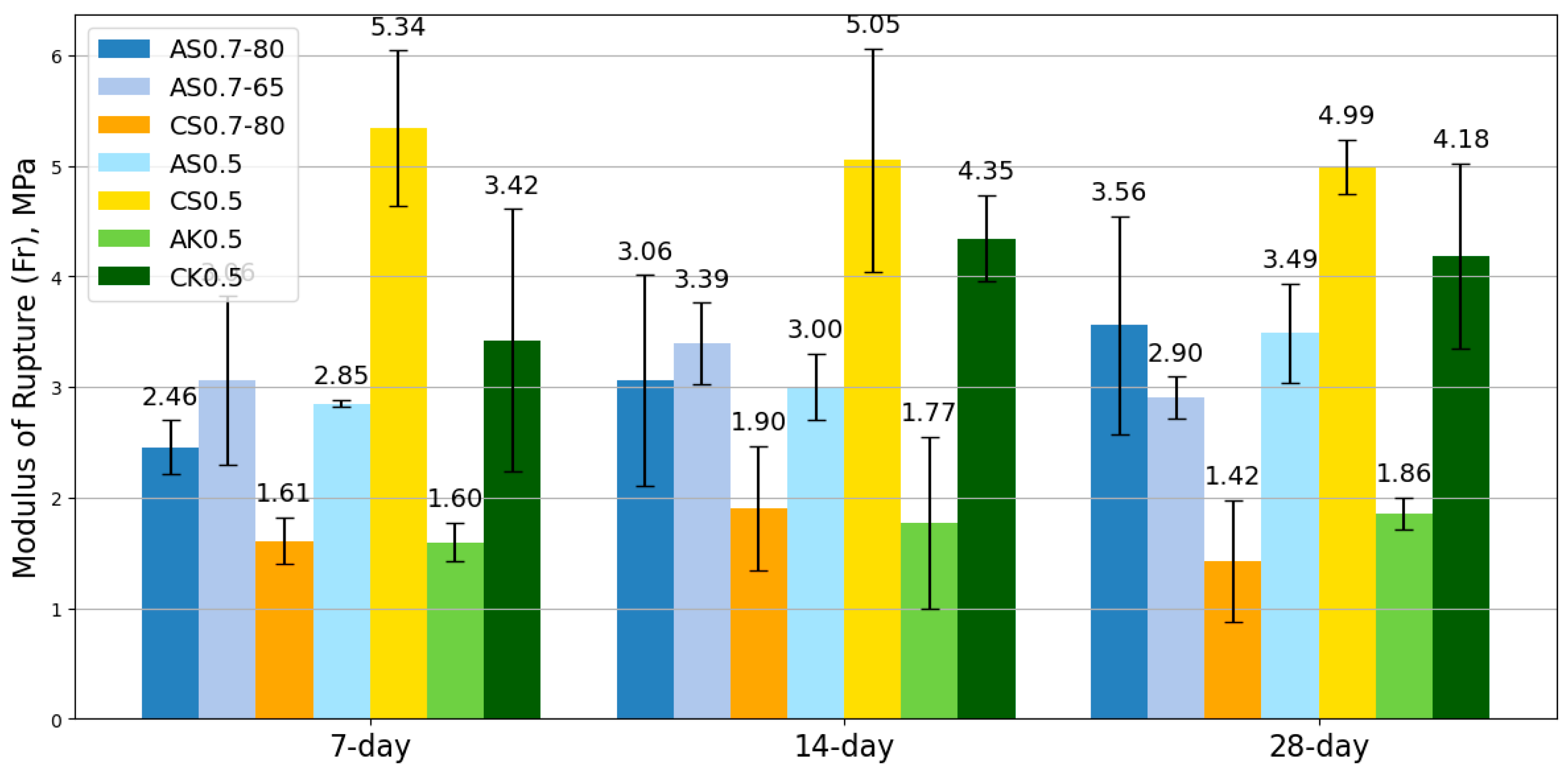

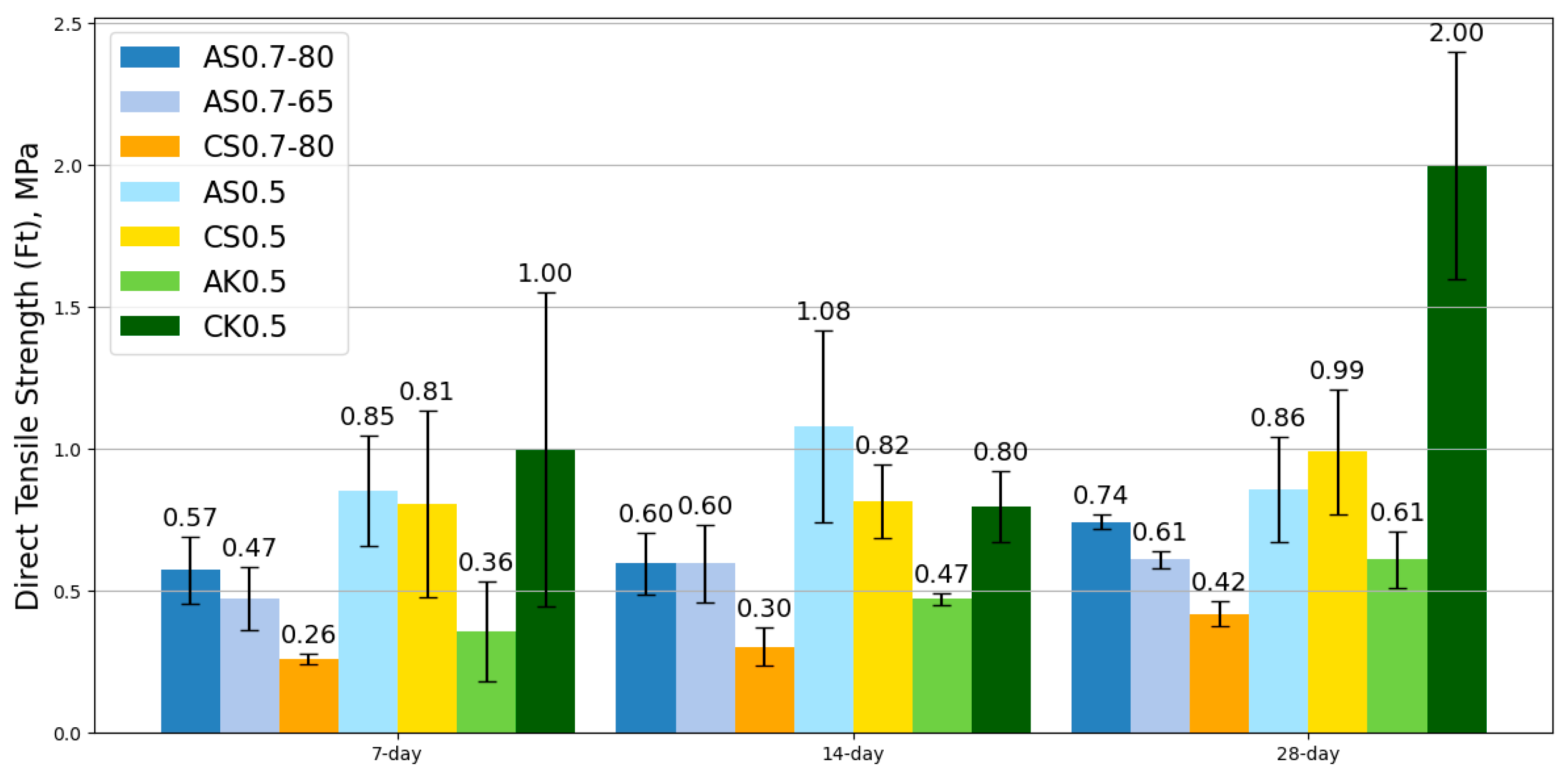

SSA-activated mortars exhibited similar workability to SSC-based mixes while offering extended setting times, providing a practical advantage in construction applications. The mechanical testing revealed that SSA-based geopolymers outperformed SSC-based counterparts in compressive, flexural, and tensile strengths. Notably, the AS0.7-65 mix achieved the highest compressive strength, outperforming its SSC counterpart cured at 80 °C, highlighting the potential to reduce energy consumption without sacrificing performance. Moreover, SSA-based mixes exhibited superior flexural and tensile properties; particularly AS0.7-80, which outperformed all other mixes in bending and tensile performance.

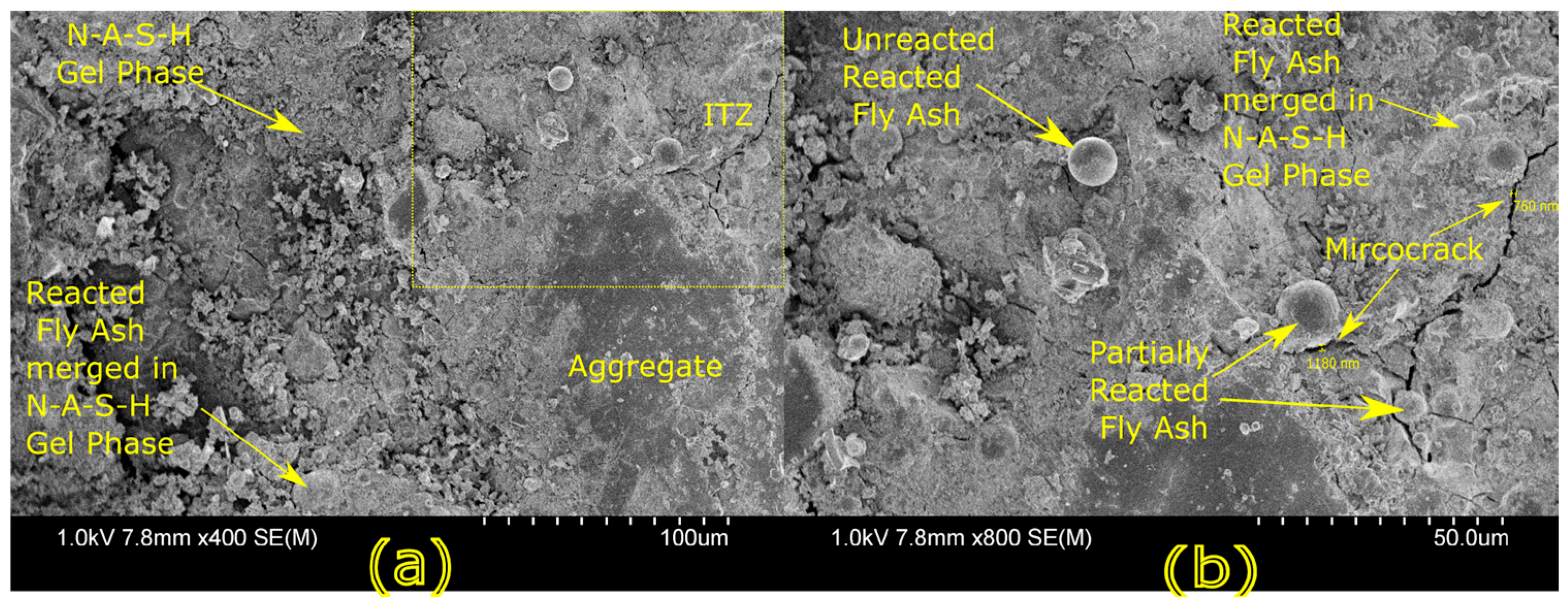

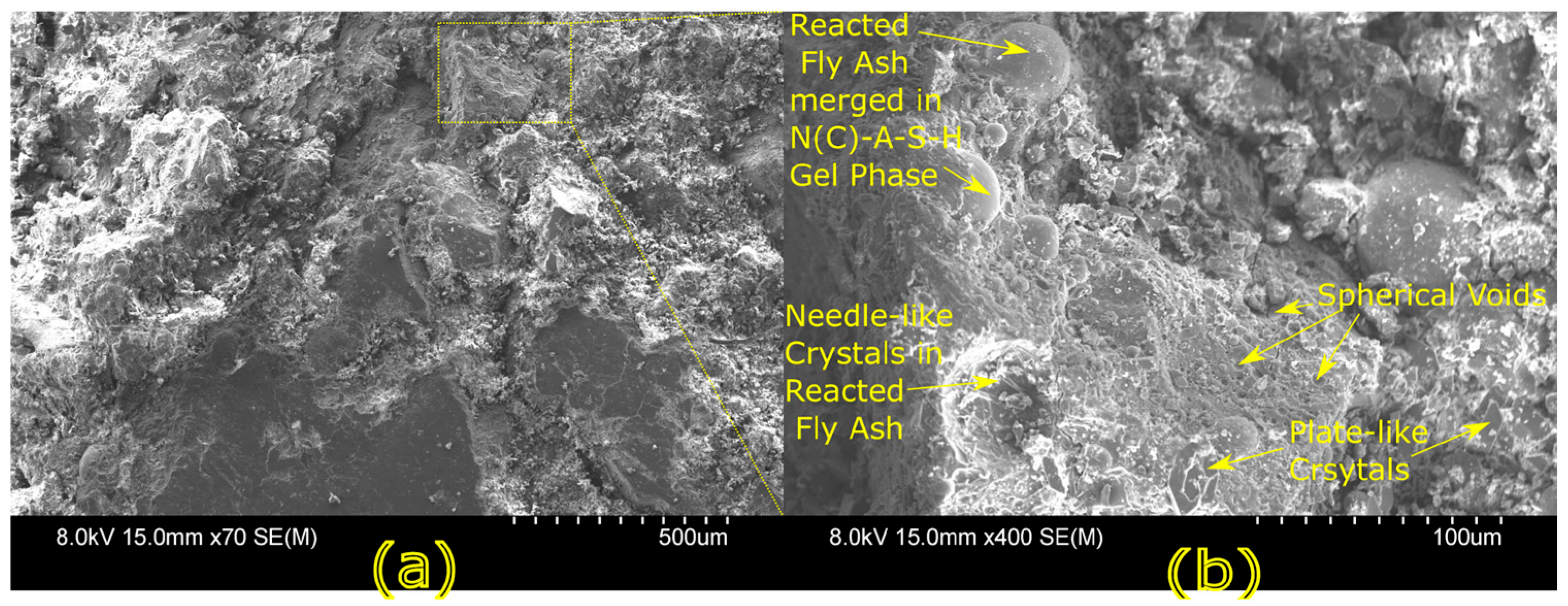

Microstructural analysis via SEM and EDX confirmed that SSA-based geopolymers formed a denser and more homogeneous geopolymer matrix with fewer unreacted fly ash particles. The incorporation of silica fume enhanced the development of the sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) gel network, resulting in a well-structured and cohesive matrix. The higher OH− content in SSA-based mixes facilitated the formation of calcium-rich crystalline phases, further improving strength and ductility. The co-existence of semi-crystalline and amorphous N(C)-A-S-H phases contributed to a more compact microstructure with lower porosity. ATR-FTIR spectra validated these chemical transformations, confirming effective geopolymerization and the development of a robust binder phase.

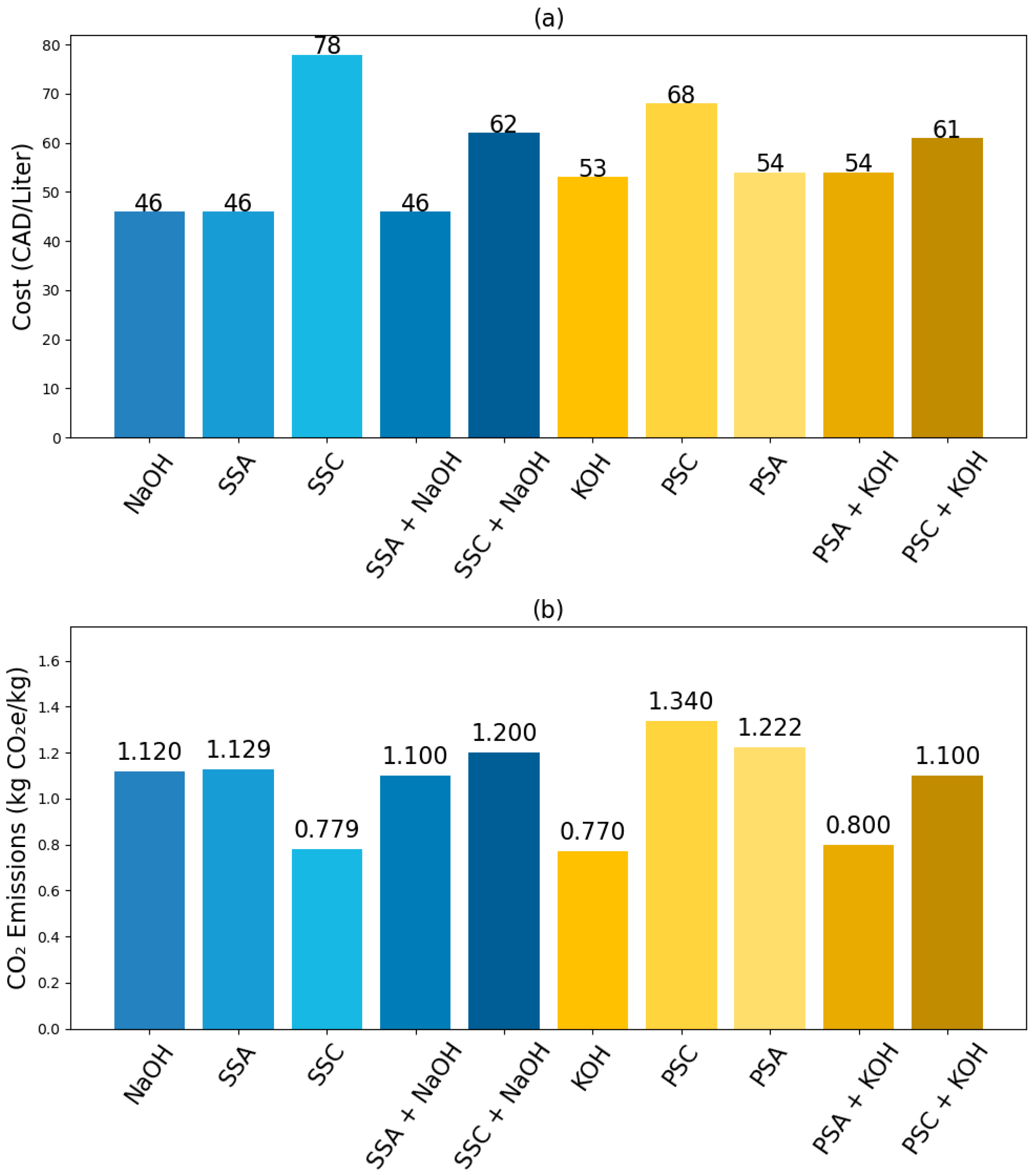

From an economic perspective, SSA-based geopolymer mortars were approximately 30% more cost-effective than SSC-based ones, primarily due to the lower production cost of SSA compared to commercially manufactured sodium silicate. The sustainability analysis revealed that SSA-based geopolymers reduced CO2 emissions by approximately 2% compared to SSC-based counterparts. Although this reduction is modest, the improved mechanical performance and cost-effectiveness of SSA significantly enhance its viability for sustainable construction applications. Furthermore, the findings indicate that curing at 65 °C is sufficient for optimal strength development, reducing the need for high-temperature curing and further minimizing the environmental impact.

Despite the advantages of SSA, further research is needed to explore ambient curing methods to enhance sustainability and reduce the energy footprint associated with geopolymer production. Additionally, long-term durability studies should be conducted to evaluate the resistance of SSA-based geopolymers to environmental factors such as sulfate attack, freeze–thaw cycles, and carbonation. Investigating the potential of SSA in large-scale applications, including 3D printing and precast elements, would further validate its implementation in the construction industry.

The scalability of SSA production is also an important consideration for industrial adoption. SSA can be synthesized in batch reactors or continuous dissolver systems, both capable of reliably dissolving silica fume in alkaline solutions. Effective temperature and mixing control are required to maintain a stable SiO2/M2O ratio and ensure consistent reactivity. The process can be integrated into existing chemical production lines, with manageable energy requirements and standard quality-control procedures. These factors indicate that SSA production can be feasibly scaled for commercial use.

In conclusion, SSA-activated geopolymers present a compelling alternative to traditional SSC-based systems, offering enhanced mechanical properties, improved microstructural integrity, and significant cost benefits. While the environmental impact reduction is modest, the overall performance gains position SSA as a viable and sustainable solution for next-generation geopolymer technology. The results of this study underscore the potential of SSA in advancing geopolymer applications, providing a practical pathway toward more sustainable and durable construction materials.