Abstract

Additive manufacturing has been adopted in several industries including the medical field to develop new personalised medical implants including tissue engineering scaffolds. Custom patient-specific scaffolds can be additively manufactured to speed up the wound healing process. The aim of this study was to design, fabricate, and evaluate a range of materials and scaffold architectures for 3D-printed wound dressings intended for soft tissue applications, such as skin repair. Multiple biocompatible polymers, including polylactic acid (PLA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), butenediol vinyl alcohol copolymer (BVOH), and polycaprolactone (PCL), were fabricated using a material extrusion additive manufacturing technique. Eight scaffolds, five with circular designs (knee meniscus angled (KMA), knee meniscus stacked (KMS), circle dense centre (CDC), circle dense edge (CDE), and circle no gradient (CNG)), and three square scaffolds (square dense centre (SDC), square dense edge (SDE), and square no gradient (SNG), with varying pore widths and gradient distributions) were designed using an open-source custom toolpath generator to enable precise control over scaffold architecture. An in vitro degradation study in phosphate-buffered saline demonstrated that PLA exhibited the greatest material stability, indicating minimal degradation under the tested conditions. In comparison, PVA showed improved performance relative to BVOH, as it was capable of absorbing a greater volume of exudate fluid and remained structurally intact for a longer duration, requiring up to 60 min to fully dissolve. Tensile testing of PLA scaffolds further revealed that designs with increased porosity towards the centre exhibited superior mechanical performance. The strongest scaffold design exhibited a Young’s modulus of 1060.67 ± 16.22 MPa and withstood a maximum tensile stress of 21.89 ± 0.81 MPa before fracture, while maintaining a porosity of approximately 52.37%. This demonstrates a favourable balance between mechanical strength and porosity that mimics key properties of engineered tissues such as the meniscus. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of 3D-printed, patient-specific scaffolds to enhance the effectiveness and customisation of tissue engineering treatments, such as meniscus repair, offering a promising approach for next-generation regenerative applications.

1. Introduction

The musculoskeletal system contains several load-bearing joint tissues, such as cartilage, ligaments, and the meniscus, that play a critical role in joint stability, shock absorption, and load distribution [1,2,3]. The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that experiences complex multiaxial loading during joint motion, including compressive, shear, and tensile stresses [4,5]. In particular, tensile stresses, generated as compressive loads, are converted into circumferential tension, enabling the meniscus to distribute loads across the knee joint effectively [6,7]. Damage to the meniscus disrupts this stress distribution mechanism, leading to increased contact stresses on the articular cartilage and an elevated risk of joint degeneration and osteoarthritis [8,9].

Due to its limited vascularisation, especially in the inner avascular region, the meniscus exhibits a poor intrinsic healing capacity, making effective repair challenging [10,11]. Current clinical treatments, including partial meniscectomy and grafting, are associated with limitations such as altered mechanical behaviour, incomplete tissue regeneration, and long-term deterioration of joint function. As a result, tissue engineering approaches that employ customised scaffolds have gained increasing interest for meniscus repair [12,13]. Such scaffolds must not only replicate the anatomical geometry of the native tissue but also provide sufficient tensile strength and controlled porosity to withstand physiological loading while supporting cell infiltration and tissue regeneration [14,15].

Material extrusion additive manufacturing (MEAM) has received substantial attention and investment in high-value sectors, including the medical industry, due to its versatility, accessibility, and compatibility with a wide range of thermoplastic polymers [16]. MEAM operates by sequentially depositing molten polymer layers onto a build platform; filament is fed into a heated chamber above the polymer’s melting temperature and extruded through a nozzle onto the build surface [17]. Scaffold geometry is defined by the controlled movement of the nozzle in the x–y plane, combined with incremental displacement along the z-axis to form three-dimensional structures. Recent advances in custom toolpath generation [17] and four-axis printing [18] have significantly expanded the design freedom of MEAM, enabling the fabrication of complex structures that were previously unattainable using conventional CAD–slicer–print workflows. These developments allow the creation of scaffolds that conform to irregular wound topographies and support non-planar printing strategies. Moreover, MEAM enables the deposition of multiple materials within a single construct, including antibacterial agents or bioactive components, making it particularly attractive for personalised and functional wound dressing applications [19,20,21]. Currently, several biocompatible and bioresorbable polymers, including polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), and polycaprolactone (PCL), are widely employed in MEAM owing to their controlled degradation behaviour and favourable printability.

A recent review by Uchida et al. [14] highlighted the advantages of MEAM-based scaffolds in promoting wound healing and tissue regeneration compared to conventional “one-size-fits-all” dressings. However, most existing studies [22,23,24] are limited to relatively simple scaffold architectures due to constraints imposed by traditional slicing software. In contrast, only a limited number of studies [17,25] have explored the use of custom toolpath generation to precisely control nozzle motion and scaffold architecture. Direct control of the printing toolpath enables the fabrication of intricate, highly porous, and open scaffold structures that do not completely seal the wound surface. These features allow healthcare professionals to visually inspect and clean the wound while enabling excess exudate produced during the inflammatory phase of healing to be absorbed through the scaffold structure. In this context, the scaffold can function as a semi-permeable membrane, facilitating fluid management while protecting the wound from mechanical damage during handling or dressing changes [26,27]. To the best of our knowledge, very few previous studies have systematically investigated the combined effects of scaffold architecture, porosity distribution, mechanical performance, and degradation behaviour of MEAM-fabricated tissue engineering meniscus scaffolds using a custom toolpath generation approach across multiple biocompatible polymers.

In this study, PLA, PVA, BVOH, and PCL were selected to evaluate their suitability for personalised meniscus tissue engineering applications. PLA and PCL were chosen as primary structural materials due to their established use in load-bearing biomedical scaffolds, where mechanical strength, controlled degradation, and biocompatibility are essential. PVA and BVOH were included as water-soluble, bioresorbable polymers to investigate their potential roles as temporary or sacrificial materials in meniscus repair strategies. Their dissolution behaviour enables controlled removal or porosity evolution without mechanical intervention, while allowing comparison of degradation behaviour for applications requiring transient structural support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Several polymeric materials were employed for the fabrication of three-dimensional (3D) printed scaffolds, selected based on their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and suitability for extrusion-based additive manufacturing. These included polylactic acid (PLA, Verbatim GmbH, Eschborn, Germany), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Bambu labs, Shenzhen, China), butenediol vinyl alcohol copolymer (BVOH, Verbatim GmbH, Eschborn, Germany), and polycaprolactone filament (PCL, 3D4Makers Ltd., Haarlem, The Netherlands). More details regarding filament-related processing and material parameters are shown in Table 1. For hygroscopic filaments such as BVOH and PVA, appropriate control of printing and handling conditions is essential. These filaments were dried prior to printing and processed using sealed containers. After printing, samples were cooled and stored immediately in airtight containers with desiccant to minimise exposure to ambient air. All materials were processed using extrusion-based 3D printing techniques under optimised printing parameters to ensure consistent filament deposition, pore uniformity, and structural integrity of the scaffolds.

Table 1.

Filament-related processing and material parameters *.

2.2. Scaffold Design and Additive Manufacturing

A Prusa i3 Mk3S material extrusion additive manufacturing (MEAM) system (Prusa Ltd., Prague, Czech Republic) was utilised to fabricate complex scaffold structures with square and circular geometries (Figure 1). The scaffolds were generated using FullControl GCode Designer excel version [35], which enables direct manipulation of the printer toolpath. This approach provides precise control over critical printing parameters, including extrusion rate, printing speed, nozzle temperature, and acceleration, offering greater flexibility and accuracy compared to conventional slicer-based software as described previously [36]. The printing parameters applied in this study are summarised in Table 2.

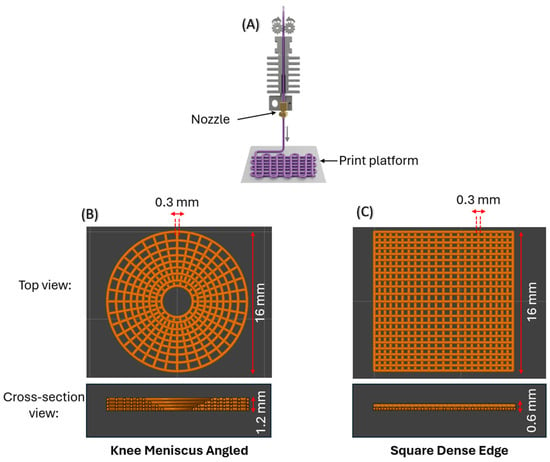

Figure 1.

(A) The MEAM setup used to print the various scaffold designs. (B) Top and cross-sectional views of an angled knee meniscus scaffold comprising four layers. (C) Top and cross-sectional views of a square dense-edge scaffold comprising two layers. All designs were fabricated with a constant line width of 0.3 mm.

Table 2.

Design parameters used to produce all scaffolds using Prusa MEAM system.

The scaffold designs were created (see Table 2) and continuously improved upon until the ideal print parameters were identified. Onshape (Onshape Ltd., Boston, MA, USA), a CAD (Computer-Aided Design) programme, and Repetier Host (Hot-World GmbH & Co. KG, Willich, Germany) were used to visualise the design so that design dimensions and constraints could be adjusted without the need for 3D printing. This was enacted to reduce unnecessary wastage of filament. Onshape was used to create a CAD model of the design so that crucial dimensions could be extracted as this was found to be quicker than solving large trigonometric equations. It also helped with calculating expected pore sizes and preventing overlapping of filament fibres. Repetier Host was used to visualise the generated G-code to verify how the design is expected to appear. This was a useful tool as it gives a reference point for the design’s appearance that can be used as a benchmark for the actual 3D prints. The design and print parameters for the final designs can be seen in Table 2. The designs were named based on their description, as follows: (1) KMA (knee meniscus angled): the knee meniscus scaffold design where each layer has a polar shift; (2) KMS (knee meniscus stacked): the knee meniscus scaffold design where each layer is perfectly stacked over each other (no polar shift); (3) SDC (square dense centre): square-shaped scaffold design where the porosity reduces towards the centre, i.e., the centre of the scaffold is denser; (4) SDE (square dense edge): square-shaped scaffold design where the porosity increases towards the centre, i.e., the edges of the scaffold are denser; (5) CDC (circle dense centre): circle-shaped scaffold design where the porosity reduces towards the centre, i.e., the centre of the scaffold is denser; (6) CDE (circle dense edge): circle-shaped scaffold design where the porosity increases towards the centre, i.e., the regions near the perimeter of the scaffold are denser; (7) CNG (circle no gradient): circle-shaped scaffold design where the porosity remains uniform, i.e., porosity remains constant towards the centre; (8) SNG (square no gradient): square-shaped scaffold design where the porosity remains uniform, i.e., porosity remains constant towards the centre.

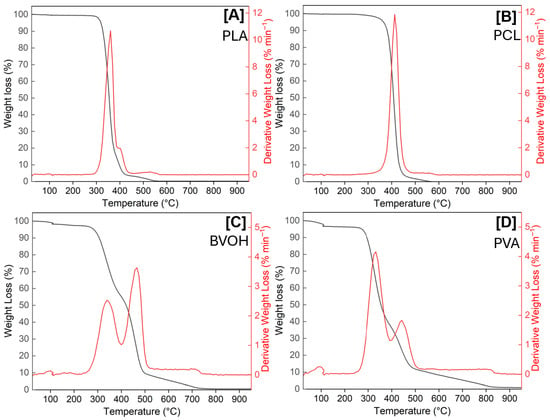

2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a LECO 701 TGA system (LECO, St. Joseph, MI, USA) to assess the thermal behaviour of the samples. The samples were heated from ambient temperature to 107 °C at 3 °C min−1 under nitrogen and held for 15 min to remove moisture. The temperature was then increased to 950 °C at 5 °C min−1 and held for 7 min under nitrogen to volatilize organic components. After cooling to 600 °C, the atmosphere was switched to air, and the samples were heated to 750 °C at 3 °C min−1 to oxidise residual material for the ashing phase. Due to the overlap of heating, the ashing phase is not illustrated on the analysed data.

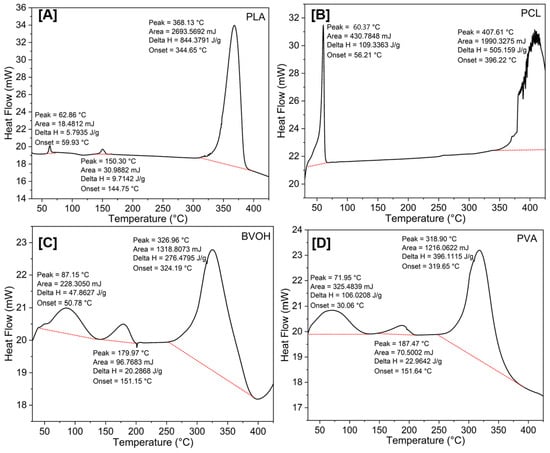

2.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed using a PerkinElmer DSC 4000 (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CI, USA) to evaluate the thermal transitions and thermal stability of the materials. The measurements were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere to prevent oxidative degradation. Samples were heated from 30 °C to 450 °C, corresponding to the temperature at which sample destruction occurs, at a constant heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The DSC instrument was operated in parallel with an indium standard for temperature and enthalpy calibration to ensure measurement accuracy and reproducibility. The resulting thermograms were used to identify characteristic thermal activities including glass transition and melting behaviour of the plastic materials.

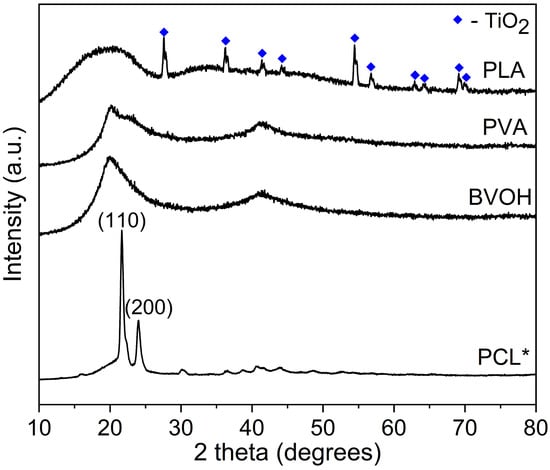

2.5. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD)

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) measurements were performed using a PANalytical Empyrean Series 2 diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK) with monochromated Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm). Diffraction patterns were analysed using HighScore Plus software (version 2013, PANalytical B.V., Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK), and phase identification was carried out by comparison with reference data from the ICDD PDF-2 database (2026 release) to assess the materials for crystallinity and/or elemental additions.

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The surface morphology of the 3D-printed samples was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with a Zeiss Gemini 300 system (Jeol IT200LV, JEOL, Peabody, MA, USA). Prior to imaging, the samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold (~10 nm) to enhance surface conductivity, increase contrast and minimise charging effects during observation. SEM images were acquired over a range of magnifications from ×25 to ×150, using an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. This analysis enabled detailed evaluation of surface features, filament deposition, pore structure, and overall scaffold morphology.

2.7. Mechanical Tensile Test

To investigate the influence of scaffold design on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed parts, PLA was chosen as the primary material for mechanical testing. Other materials, including PVA, BVOH, and PCL, were excluded from tensile testing due to their susceptibility to moisture absorption and subsequent degradation, which could affect the accuracy and reliability of the mechanical properties.

PLA scaffolds were subjected to tensile testing using a TA.XTplusC texture analyser (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) to assess their mechanical performance under stress. To ensure proper clamping of each scaffold during mechanical testing, all designs were scaled by a factor of two in the x- and y-directions. Despite this geometric scaling, the cross-sectional area perpendicular to the applied load was maintained at the same value as in the original designs by preserving key printing parameters, including line width and layer height. As a result, the effective load-bearing cross-section remained unchanged, ensuring that the measured mechanical properties were directly comparable to those of the unscaled designs.

The tensile tests were conducted by stretching each sample until reaching 20% strain, as described in the study by Ottenio et al. [37]. Initially, the texture analyser recorded the force (N) versus distance (mm) data. This data was subsequently transformed into stress versus strain curves, allowing for the calculation of mechanical properties, such as Young’s modulus, yield strength, and ultimate tensile strength. For each scaffold design, three samples (n = 3) were tested, and the mechanical properties were averaged to ensure statistical reliability.

The applied force was subsequently converted to engineering stress by dividing the measured force by the cross-sectional area of each scaffold, as shown in Equation (1). This normalisation accounts for differences in specimen geometry and enables direct comparison of the mechanical response between different scaffold designs.

Due to the shape of the printer’s nozzle and the print parameters, namely the line width and layer height, both being 0.3 mm, the print is created by depositing material along the path in the shape that can be approximated to that of a circle of diameter 0.3 mm. Thus, the cross-section can be seen in Figure 1B,C and the area was calculated in CAD by cutting cross-sections of each scaffold. The square scaffold comprises two layers, whereas the KMA and KMS designs incorporate two additional layers to form a hemispherical cavity that accommodates the femoral condyle, thereby mimicking the geometry of the knee meniscus, as shown in Figure 1B. The total cross-sectional area of the scaffold was then obtained by summing the calculated areas across all print layers. The resulting cross-sectional areas corresponding to each scaffold design are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cross-sectional area corresponding to each scaffold design, calculated perpendicular to the direction of the applied tensile load.

Strain was calculated by dividing the measured displacement by the original gauge length or diameter of each scaffold design, as shown in Equation (2). This approach provides a normalised measure of deformation, allowing direct comparison of the mechanical response across different scaffold geometries.

Young’s modulus was determined by plotting stress as a function of strain and calculating the slope of the elastic region, which corresponds to the initial linear portion of the stress–strain curve. The elastic region was identified using the 0.2% strain offset method, which allows for consistent determination of elastic behaviour in materials that do not exhibit a well-defined yield point. The intersection between the stress–strain curve and the 0.2% offset line was taken as the yield point of the scaffold structure. In addition to Young’s modulus and yield strength, other key mechanical properties, including the ultimate tensile strength (UTS), were obtained directly from the stress–strain curves.

2.8. Calculating Porosity

The porosity of the printed scaffold structures was determined by comparing their measured mass to that of a hypothetical solid structure with identical external geometry and dimensions. This mass-based approach enables estimation of the internal void fraction within each scaffold design.

To calculate the mass of the solid-equivalent structure, the density of the printing filament was first determined experimentally. Sections of filament were cut into three separate samples, and their mass and geometric dimensions were measured. The filament density (Equation (3)) was calculated using the average mass and volume of the three samples. The volume of each filament sample (Equation (4)) was determined by multiplying the cross-sectional area by its height, which in this case corresponds to the filament length. Using the calculated filament density, the mass of a fully solid structure with the same external dimensions as the scaffold was then estimated.

Porosity was subsequently calculated by comparing the measured mass of each printed scaffold with the estimated mass of its fully solid (0% porosity) equivalent. The difference between these two values represents the volume fraction of pores within the structure, allowing porosity to be expressed as a percentage. This mass-based approach provides a consistent and reproducible method for comparing porosity across different scaffold designs. Once the density of the filament had been determined, the mass of the solid (0% porosity) equivalent structure could be calculated by rearranging Equation (3) to get Equation (5), as shown below:

Equation (4) was used to calculate the volume of the cylindrical scaffold designs (KMA, KMS, CDC, CDE and CNG), while Equation (6) was applied to determine the volume of the cuboidal scaffold designs (SDC, SDE and SNG). These equations were selected based on the external geometry of each scaffold to ensure accurate volume estimation for subsequent porosity calculations. For each scaffold design, three samples were analysed, and the average volume and porosity values were calculated to improve measurement reliability and reproducibility.

Equation (7) was then used to calculate the volumetric porosity of the scaffold designs. In addition, an optical microscope (AmScope, Irvine, CA, USA) was employed during the initial stages of fabrication to examine the resulting pore sizes and verify printing accuracy. Based on these observations, printing parameters, including initial layer height and extrusion rate, were adjusted as necessary to ensure that the experimentally achieved pore sizes closely matched the intended design dimensions, within the tolerances of the 3D printer and the microscope.

2.9. In Vitro Degradation Test

To evaluate the in vitro degradation behaviour and stability of the scaffolds, degradation tests were conducted on PLA, BVOH, PCL and PVA samples. Three-dimensional printed specimens from each material were placed in individual containers containing 30 mL of 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated at 37 °C to simulate physiological conditions. The study was carried out for up to 60 min. Prior to immersion, samples were dried at room temperature at 21 °C and weighed to obtain their initial mass. At predetermined time intervals, the samples were removed, gently dried on paper tissue to remove surface moisture, and reweighed to monitor mass changes.

During testing, noticeable softening of the BVOH and PVA scaffolds made handling difficult. To address this, a customised perforated ladle was designed and 3D-printed to allow safe handling of partially degraded samples. After each measurement, the samples were returned to the oven to maintain a constant temperature of 37 °C.

Following completion of the degradation tests, the PBS solutions were maintained at 37 °C for an additional 48 h to ensure complete dissolution of soluble degradation products. The pH of each solution was then measured using a calibrated pH meter (Mettler Toledo Ltd., Columbus, OH, USA) and compared with fresh PBS to assess changes in solution acidity associated with scaffold degradation.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Numerical data was calculated and reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), with each experimental condition tested in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test to evaluate differences between groups. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant, whereas a p-value > 0.05 indicated no statistically significant difference between the groups.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Design Freedom Through Custom Toolpath Generation

By directly controlling the printer toolpath, rather than relying on a conventional CAD–slicer–print workflow, a range of architecturally complex scaffold structures were fabricated using PLA with a constant line width and layer height of 0.3 mm (Figure 2). This approach highlights the versatility of the custom toolpath generation software in enabling precise control over scaffold geometry and porosity distribution.

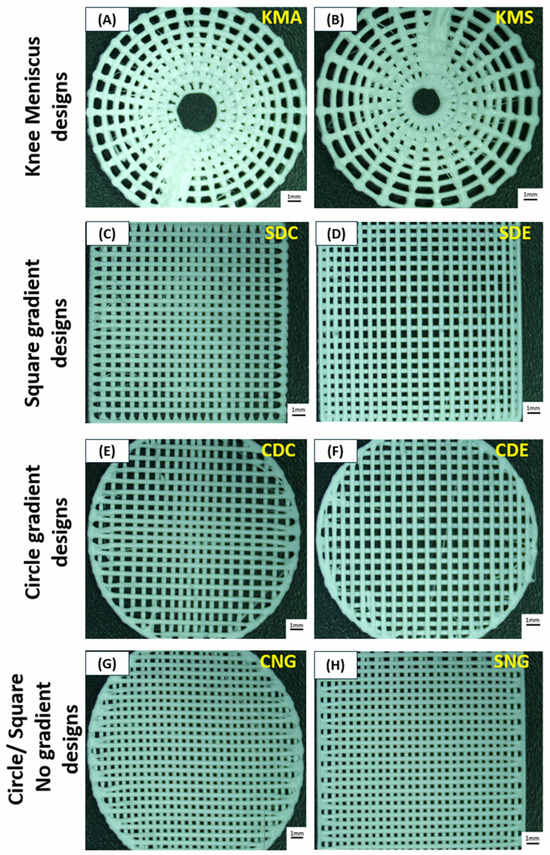

Figure 2.

Optical images of the different PLA scaffold designs: (A) knee meniscus angled (KMA), (B) knee meniscus stacked (KMS), (C) square dense centre (SDC), (D) square dense edge (SDE), (E) circle dense centre (CDC), (F) circle dense edge (CDE), (G) circle no gradient (CNG) and (H) square no gradient (SNG). Scale bars represent 1 mm.

The knee meniscus angled (KMA) and knee meniscus stacked (KMS) designs (Figure 2A,B) each consist of four layers in which the internal void progressively expands with height, creating a vertical porosity gradient. In the KMA design, successive layers are rotated by 20°, introducing a polar offset between layers, whereas in the KMS design no inter-layer rotation is applied, resulting in vertically stacked fibres. This vertical gradient was incorporated to better mimic the curved internal cavity and load-distribution characteristics of the native meniscus.

The circle dense centre (CDC) and circle dense edge (CDE) designs (Figure 2E,F) comprise two identical layers of unidirectional lines, with the second layer rotated by 90°. Both designs incorporate a controlled radial density gradient, with CDC exhibiting increased density at the centre and CDE at the periphery. Similarly, the square dense centre (SDC) and square dense edge (SDE) designs (Figure 2C,D) employ two orthogonally oriented layers with graded infill density, where material concentration is either central or edge-dominant. In contrast, the circle no gradient (CNG) and square no gradient (SNG) designs (Figure 2G,H) consist of two orthogonal layers without any spatial density variation.

The minimum pore size for all gradient designs was set to 0.3 mm, while the maximum pore size was 1.2 mm. These values were selected based on previous findings by Saijo-Rabina et al. [38], which demonstrated that pore sizes within this range promote effective fluid transport through capillary action. For non-gradient designs, pore sizes were maintained at 0.3 mm, as smaller pores (approximately 400 µm) have been shown to provide improved performance in applications where controlled fluid management is required. To ensure consistency across all designs, printing parameters including line width and layer height were kept constant at 0.3 mm. This allowed the influence of scaffold architecture, porosity gradients, and layer orientation on mechanical and degradation behaviour to be evaluated independently of printing resolution effects.

3.2. Material Effects on Complex Structure Printing

To further assess the transferability of the proposed scaffold designs to other biocompatible polymers suitable for tissue engineering, all eight scaffold architectures listed in Table 2 were fabricated using PLA, BVOH, PVA, and PCL under the printing conditions summarised in Table 4. Optical images of the resulting constructs are shown in Figure 3. A qualitative comparison of the printed samples revealed a clear trend in print quality, which decreased in the following order: PLA > PCL > BVOH > PVA. This observation was consistent across all scaffold designs and was further supported by the surface morphology analysis discussed below.

Table 4.

MEAM process parameters for the various materials used to fabricate the designed scaffold geometries.

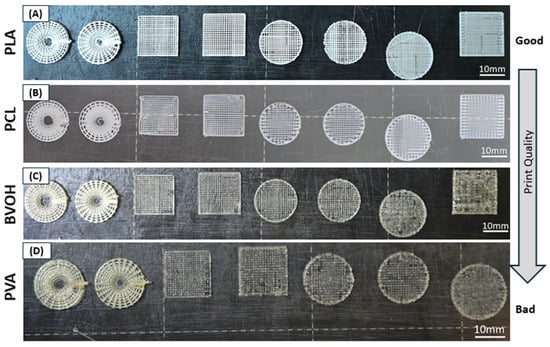

Figure 3.

Effect of material properties on the 3D printing of different scaffold designs. All primary scaffold architectures were fabricated using (A) PLA, (B) PCL, (C) BVOH and (D) PVA. PLA exhibited the highest print quality, while PVA showed multiple printing defects. Scale bars represent 10 mm.

Figure 4 presents SEM images of all four materials acquired at magnifications of ×25 and ×150, allowing direct comparison of surface morphology and roughness. PLA (Figure 4A,B) and PCL (Figure 4C,D) present relatively smooth and continuous surfaces with well-defined filament boundaries, indicating stable extrusion and consistent material flow during printing. In particular, PLA demonstrated the highest fidelity to the intended design geometry, with minimal surface defects. This superior printability can be attributed to its favourable melt viscosity, wide processing window, thermal stability, and low sensitivity to environmental moisture. Unlike the other materials, PLA did not require specialised storage conditions and remained relatively unaffected by ambient humidity. Optimal print quality for PLA was achieved at a nozzle temperature of 220 °C and a bed temperature of 60 °C, as summarised in Table 4.

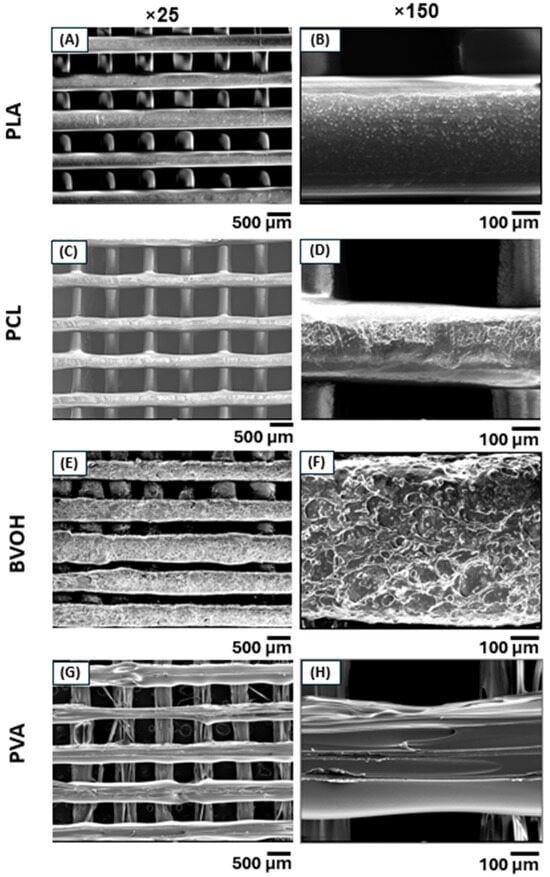

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of 3D-printed scaffolds acquired at two different magnifications. (A,B) PLA and (C,D) PCL exhibited superior print quality with smoother and more uniform surfaces compared to (E,F) BVOH and (G,H) PVA, which showed increased surface roughness and printing defects.

In contrast, BVOH (Figure 4E,F) and PVA (Figure 4G,H) displayed noticeably rougher surfaces with pits, voids and irregular filament deposition. These defects are largely attributed to the hygroscopic nature of both polymers, which readily absorb moisture from the environment, evidenced by a minor weight loss for each polymer when heating to 107 °C (Figure 5A–D). Despite storage in sealed containers with desiccant and using filament dryers, both materials remained prone to moisture-related printing issues. During extrusion, absorbed moisture can vaporise, leading to bubble formation, surface pitting, and inconsistent material flow. In addition, the relatively low mechanical strength of BVOH and PVA filaments resulted in frequent filament snapping within the extruder, often necessitating partial disassembly of the extruder and hotend to remove lodged filament. BVOH printed optimally at the same temperature settings as PLA, allowing the same G-code to be reused without modification, whereas PVA required a higher nozzle temperature of 230 °C and a lower bed temperature of 40 °C (Table 4).

Figure 5.

Comparison of thermogravimetric behaviour of PLA (A), PCL (B), BVOH (C), and PVA (D).

PCL exhibited intermediate surface quality. The filament was noticeably softer than the other polymers and frequently deformed or fractured within the extruder mechanism. Successful printing required nozzle and bed temperature settings outside those recommended by the filament manufacturer (3D4Makers, Haarlem, The Netherlands). Optimal extrusion was achieved at a nozzle temperature of 190 °C with the print bed unheated (Table 4), as PCL did not melt sufficiently at the manufacturer-specified temperatures. Reducing the tension on the extruder drive gears helped to mitigate filament breakage, although extrusion failures still remained relatively common. It is worthwhile to mention that the primary difference between the G-code used for each material was limited to the start code, which defines the temperature settings for the nozzle and print bed. As all filaments shared identical nominal diameters, the remainder of the toolpath including line width, layer height, and deposition geometry remained unchanged across materials. This highlights the advantage of the custom toolpath generation approach, which enables consistent geometric control while allowing material-specific thermal parameters to be adjusted independently.

3.3. Structural and Chemical Analysis of Scaffolds

3.3.1. TGA

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed to evaluate the thermal stability and degradation behaviour of PLA, PCL, BVOH, and PVA, as shown in Figure 5. The TGA curves revealed distinct mass loss profiles for each material, reflecting differences in moisture sensitivity, thermal stability, and decomposition mechanisms.

As previously mentioned, the ability to adsorb moisture (hygroscopic nature) is evident for both BVOH and PVA, which were recorded to hold 1.63 wt.% and 3.26 wt.%, respectively, whereas PLA and PCL both presented <0.3 wt.% of moisture, as reflected in the derivative weight loss plot (red) for all four polymers, with either a weight loss at ≈100 °C (Figure 5C,D) or negligible difference (Figure 5A,B). This early-stage mass is consistent with the printing challenges observed, such as produced surface roughness and filament instability.

PLA exhibited a single dominant degradation step at 360 °C, indicating good thermal stability. PCL showed a similarly well-defined degradation profile, with onset of thermal decomposition occurring at higher temperatures than PLA (412 °C). In contrast, both BVOH and PVA displayed an initial weight loss starting at lower temperatures (268 °C and 266 °C, respectively). This leads to both materials displaying two separate mass losses at increasing temperature due to depolymerisation; for BVOH these reached a maximum at 340 °C and 465 °C, with the latter being the major mass loss component. For PVA the two mass losses were at 331 °C and 443 °C; here the major thermal event was seen at the lower temperature, clearly demonstrating the poor thermal stability of PVA. Interestingly, PLA was the only polymer that generated an inorganic ash residue (0.8 wt.%), suggesting that the other polymers investigated were organic by nature.

Overall, the TGA results confirm that PLA and PCL possess superior thermal stability compared to BVOH and PVA, supporting their suitability as primary structural materials for 3D-printed tissue engineering scaffolds. Conversely, the lower thermal stability and moisture sensitivity of BVOH and PVA suggest they are more appropriate to use as sacrificial materials rather than load-bearing scaffold components.

3.3.2. DSC Analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry was carried out across all four polymers, the results of which are shown in Figure 6A–D; in each case the glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm) and material destruction temperatures (Td) can be elucidated, the latter in close relationship with the temperatures denoted via thermogravimetric analysis. These measurements are used to infer structural alterations as temperature increases, all of which are endothermic by nature and are represented by positive Delta H values. For the cases of PLA, BVOH and PVA, there are clearly defined Tg and Tm, the former onsets being 59.93 °C, 50.78 °C and 30.06 °C, respectively. The Tm onset values were found to be 144.75 °C, 151.15 °C and 151.64 °C, respectively. For the case of PCL, it was previously reported that the Tg is ~−60 °C, whereas the Tm has been found to be ~56 °C, which is identical to the value we show in Figure 6B [39]. With this data in mind, it confirms that the operational temperatures used for both the bed and nozzle in Table 4 were appropriate, where the bed temperatures align with the Tg onset values and the nozzle temperatures are above the Tm values. The printing nozzle temperature of PCL was approximately three times its Tm, likely due to the softness of the filament. Although PCL melts at approximately 56 °C, the viscosity of the molten polymer may have remained too high for extrusion until a significantly higher temperature was reached [40,41].

Figure 6.

Comparison of DSC behaviour of PLA (A), PCL (B), BVOH (C), and PVA (D).

3.3.3. PXRD Analysis

Figure 7 compares the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) diffractograms of PLA, PCL, BVOH, and PVA. PCL was the only polymer that clearly showed well-defined, crystalline properties with peaks at 21.57° (110) and 24.01° (220). The other polymers are generally amorphous by nature with possible semi-crystalline properties developing at ~41°. PLA did exhibit low-intensity crystalline features at 27.65°, 36.32°, 41.36°, 44.29°, 54.54°, 56.83°, 62.97°, 64.31°, 69.20° and 69.98°, which all match TiO2, specifically the rutile polymorph. It is believed that these were added to the PLA filament to act as a colouring agent, as shown in Figure 4A where white PLA samples are shown. The low intensity denotes a minor metal loading, which is consistent with the low ash found in the thermogravimetric analysis (<1%).

Figure 7.

Comparison of PXRD behaviourPLA, PCL, BVOH, and PVA. * Due to the crystallinity of PCL, the intensity of this data was reduced by 5×.

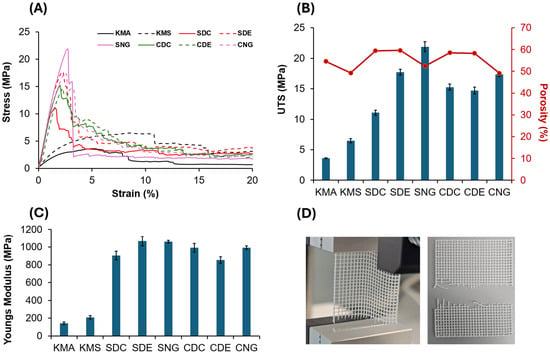

3.4. Tensile Strength and Porosity Analysis

The tensile test results for all scaffold designs are presented in Figure 8, with stress (MPa) plotted against strain (Figure 8A), along with the corresponding mechanical properties, including ultimate tensile force (UTF) (Figure 8B) and Young’s modulus (Figure 8C). Figure 8D illustrates scaffold clamping during tensile testing, showing improper clamping with slippage or misalignment (left) and proper clamping with secure alignment after testing (right).

Figure 8.

(A) Tensile test results for all scaffold designs: solid black line, knee meniscus angled (KMA); dashed black line, knee meniscus stacked (KMS); solid red line, square dense centre (SDC); dashed red line, square dense edge (SDE); solid pink line, square no gradient (SNG); solid green line, circle dense centre (CDC); dashed green line, circle dense edge (CDE); and dashed pink line, circle no gradient (CNG). (B) Influence of the various designs on ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and porosity. (C) Young’s modulus. (D) Images illustrating scaffold clamping during tensile testing: the left image shows an improperly clamped scaffold during testing, exhibiting slippage or misalignment, while the right image shows a properly clamped scaffold after testing, demonstrating correct alignment and secure fixation within the test rig for reliable measurements.

As all scaffolds were fabricated from PLA, their intrinsic material properties would be identical if tested using standardised specimens (ISO 527-1:2019 [42]). This study aimed to evaluate the influence of scaffold architecture and porosity on structural performance, and therefore tensile testing was conducted using cross-sectional areas corresponding to the original scaffold geometries to determine architecture-dependent Young’s modulus and ultimate tensile force (UTF). All designs were uniformly scaled by a factor of two in the x- and y-directions while maintaining identical print parameters. The number of layers and fibres was kept constant, with the increase in size achieved by enlarging pore dimensions. Consequently, the cross-sectional area perpendicular to the applied load remained unchanged. According to Griffith’s size effect [43], the reported mechanical values may therefore be conservative.

Non-gradient designs exhibited the highest UTF values due to their smaller average pore sizes and greater number of load-bearing fibres. For example, the square no-gradient (SNG) design withstood a maximum force of 110.34 ± 0.46 N, compared to 90.53 ± 0.18 N for the circle no-gradient (CNG) design. However, these designs also exhibited lower volumetric porosities, which may limit their applicability where permeability and tissue integration are required [44,45]. Figure 8B summarises the volumetric porosity of all designs. The square dense edge (SDE) design exhibited the highest volumetric porosity (59.63 ± 0.79%), while the circle no-gradient (CNG) design showed the lowest (49.12 ± 1.22%). This difference is primarily due to fibre distribution rather than the presence of a gradient. In the SDE design, material is concentrated at the periphery, resulting in fewer fibres and larger pore volumes in the central region. In contrast, the CNG design maintains a uniform fibre distribution with consistently small pores, leading to lower overall porosity.

Although the gradient designs did not exhibit the highest mechanical performance among the tested samples, their Young’s modulus and ultimate tensile force (UTF) remained within ranges reported as suitable for tissue scaffold applications in the literature [2,46,47]. The gradient designs achieved the highest volumetric porosities, which may be advantageous in applications where biological performance is prioritised over load-bearing capacity [48,49]. High porosity facilitates nutrient diffusion, oxygen transport, and cell migration, all of which are critical for tissue ingrowth [50,51,52]. In addition, graded porosity can promote region-specific biological responses, supporting both surface-level healing and deeper tissue regeneration [2,38]. Gradient architecture enables spatial customisation of pore size in regions of interest while reducing material usage in areas subjected to lower mechanical demands [47,53]. This design flexibility is particularly relevant for structurally heterogeneous tissues, such as the knee meniscus. By increasing pore size locally, scaffolds may enhance wound exudate absorption and maintain a favourable healing environment, while denser regions provide mechanical support and structural guidance [47,54,55]. Among the knee meniscus designs, the knee meniscus stacked (KMS) scaffold exhibited higher mechanical performance than the knee meniscus angled (KMA) design (81.13 ± 0.251 N vs. 46.06 ± 0.114 N), which can be attributed to improved fibre alignment under tensile loading. However, this increase in strength was accompanied by reduced porosity, illustrating the trade-off between mechanical reinforcement and permeability. Conversely, the higher porosity of the KMA design may be beneficial in applications where enhanced fluid transport and cell infiltration are required. These results demonstrate that scaffold architecture can be used to tune the balance between mechanical performance and porosity, enabling design optimisation tailored to specific tissue engineering applications.

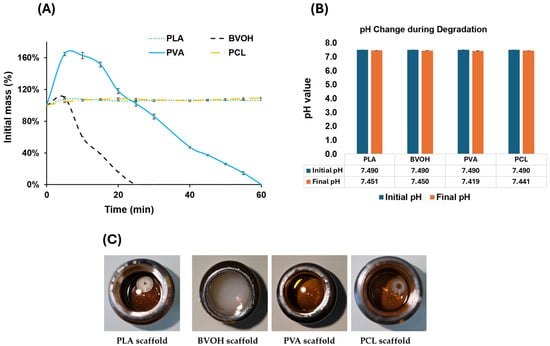

3.5. Degradation Analysis

Figure 9A shows the interpolated degradation profiles plotted as a function of time over a 60 min period. The degradation results confirm that only BVOH and PVA underwent complete dissolution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) under the tested conditions. BVOH exhibited the fastest degradation, with the entire scaffold dissolving within approximately 25 min. This rapid dissolution was accompanied by a visible change in the PBS solution from clear to a white, translucent appearance (Figure 9C). In contrast, the PVA scaffold dissolved more slowly, requiring approximately 60 min to fully dissolve; however, the PBS solution remained visually clear following dissolution.

Figure 9.

(A) Interpolated degradation rate of all materials plotted over a 60 min duration. (B) pH values of all four materials before and after 48 h degradation. (C) Photographs of PBS solutions after 48 h containing PLA, BVOH, PVA, and PCL scaffolds.

The degradation also shows that PLA and PCL did not dissolve during the test period. Instead, both materials exhibited a modest initial increase in mass due to PBS absorption, resulting in slight scaffold swelling. This mass increase stabilised within approximately 20 min, with PLA and PCL absorbing approximately 6–8% of their initial mass. A two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the mass change behaviour of PLA and PCL yielded a p-value of 0.14, indicating no statistically significant difference between the two materials and confirming that they behaved similarly under the tested conditions.

BVOH and PVA also exhibited rapid initial PBS absorption prior to degradation. BVOH reached approximately 110% of its initial mass, while PVA absorbed a substantially greater volume of PBS, reaching approximately 165% of its original mass. This absorption occurred rapidly, within the first 5 min of immersion. Following this initial uptake, both materials reached a saturation point beyond which further absorption was limited. At this stage, degradation became dominant, leading to a gradual reduction in mass. As illustrated in Figure 9A, both the absorption and degradation phases for BVOH and PVA exhibited near-linear behaviour, characterised by an initial linear increase in mass, followed by a brief plateau where absorption and degradation rates briefly achieved equilibrium, and finally a linear decrease corresponding to scaffold dissolution.

The pH was measured before and after 48 h at 37 °C, with no significant differences observed among all material types, as shown in Figure 9B. Measurement intervals were adapted to the degradation behaviour of each material; all scaffolds were initially immersed in separate PBS solutions and assessed after 30 min. As the BVOH scaffold fully dissolved within this period, subsequent measurements were taken at 5 min intervals to accurately capture the dissolution process. For PVA, which degraded more slowly, a combination of 5 min and 10 min intervals was used, with shorter intervals applied during the early and final stages of dissolution. In contrast, PLA and PCL did not dissolve, and measurements were initially taken at 5 min intervals, followed by longer intervals (10 min, 30 min, and finally 60 min) once mass stabilisation was observed. Figure 9C further illustrates the clarity of the PBS solutions following each material’s degradation test, with images captured 48 h after the start of the experiment to ensure complete dissolution of any soluble degradation products.

4. Conclusions

Eight scaffold architectures:KMA, KMS, SDC, SDE, SNG, CDC, CDE, and CNGwere designed with controlled porosity gradients in the x-, y-, and z-directions and fabricated using material extrusion additive manufacturing. Tensile testing of PLA scaffolds was performed to evaluate the influence of scaffold architecture on mechanical performance, while volumetric porosity was calculated to assess mass, permeability, and suitability for tissue engineering.

All designs exhibited mechanical properties adequate for biomedical applications. However, the dense-edge designs, SDE and CDE, demonstrated the most favourable balance between mechanical strength, porosity, and mass. The SDE design achieved the highest overall performance, withstanding a maximum force of 73.4 N before fracture while maintaining a porosity of 59.63%. The CDE design showed comparable performance, with an ultimate tensile force of 60.8 N and a porosity of 58.27%. These results highlight the effectiveness of graded porosity in optimising scaffold performance. The dense-edge architectures enabled larger central pore sizes while maintaining increased material density at the periphery, allowing controlled fluid transport and improved fixation using bioadhesives. This design strategy supports mechanical stability while accommodating the biological requirements of the healing process. An in vitro degradation study using the KMA design printed in PLA, PVA, BVOH, and PCL revealed that PLA and PCL exhibited comparable degradation stability (p > 0.05). While both are suitable for structural scaffolds, PLA offered advantages in printability and cost. Among the water-soluble materials, PVA outperformed BVOH by dissolving more slowly, absorbing more fluid, and avoiding solution discolouration.

Overall, this study demonstrates that custom toolpath-based additive manufacturing provides a powerful platform for precisely tailoring scaffold architecture, mechanical behaviour, porosity distribution, and degradation characteristics. These findings establish a strong foundation for the development of patient-specific meniscus scaffolds and highlight the potential of architecturally graded designs to advance personalised tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and B.Z.; methodology, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; validation, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; formal analysis A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; investigation, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; resources, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; data curation, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., and B.Z.;; writing—review and editing, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; visualization, A.P., A.M., M.J.T., F.E.L., H.G., J.H., and B.Z.; supervision, A.M., M.J.T., H.G., and B.Z.; project administration, A.P., A.M., and B.Z.; funding acquisition, A.M., M.J.T., H.G., and B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Royal Society Research Grant (RG\R1\241133) and the EPSRC Centres for Doctoral Training Grant (EP/S023763/1).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

B.Z. would like to thank The Royal Society Research Grant (RG\R1\241133) for supporting the research work and collaborations. M.J.T. and F.E.L. thank the EPSRC Centres for Doctoral Training in Offshore Wind Energy (EP/S023763/1) for F.E.L.’s studentship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ni, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yao, J. Introduction to musculoskeletal system. In Biomechanical Modelling and Simulation on Musculoskeletal System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, J.; Narayan, R.J. Gradient scaffolds for osteochondral tissue engineering and regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8149–8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paggi, C.A.; Teixeira, L.M.; Le Gac, S.; Karperien, M. Joint-on-chip platforms: Entering a new era of in vitro models for arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochehdehi, A.R.; Nemavhola, F.; Thomas, S. Structure, function, and biomechanics of meniscus cartilage. In Cartilage Tissue and Knee Joint Biomechanics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, A.L.; Guilak, F. Mechanobiology of the meniscus. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masouros, S.; McDermott, I.; Amis, A.; Bull, A. Biomechanics of the meniscus-meniscal ligament construct of the knee. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2008, 16, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logerstedt, D.S.; Ebert, J.R.; MacLeod, T.D.; Heiderscheit, B.C.; Gabbett, T.J.; Eckenrode, B.J. Effects of and response to mechanical loading on the knee. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 201–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco Grajales, G.A. Mechanobiological Modeling of Articular Cartilage: Predicting Post-Traumatic Knee Osteoarthritis; Itä-Suomen Yliopisto: Kuopio, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Chung, S.H.; Barker, S.; Craig, D.; Narayan, R.J.; Huang, J. Direct ink writing of polycaprolactone/polyethylene oxide based 3D constructs. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2021, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Dai, W.; Cheng, J.; Fan, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Ao, Y. Advances in the mechanisms affecting meniscal avascular zone repair and therapies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 758217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Campi, S.; Romeo, G.; Spiezia, F.; Maffulli, N.; Denaro, V. Biological strategies to enhance healing of the avascular area of the meniscus. Stem Cells Int. 2012, 2012, 528359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczyński, N.; Boś, J.; Białoskórska, K.; Aleksandrowicz, Z.; Turoń, B.; Zabrzyńska, M.; Bonowicz, K.; Gagat, M. The Meniscus: Basic Science and Therapeutic Approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.A.; Garg, A.K.; Silva-Correia, J.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M.; Collins, M.N. The meniscus in normal and osteoarthritic tissues: Facing the structure property challenges and current treatment trends. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 21, 495–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, D.T.; Bruschi, M.L. 3D printing as a technological strategy for the personalized treatment of wound healing. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ning, C.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Xie, Y.; Li, J.; Qiao, K.; Bahatibieke, A.; Lu, Q. Host–Guest Functionalized Hierarchical Porous Polyurethane Scaffold for Mechano-Biological Coupling in Meniscus Reconstruction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e23756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allum, J.; Moetazedian, A.; Gleadall, A.; Mitchell, N.; Marinopoulos, T.; McAdam, I.; Li, S.; Silberschmidt, V.V. Extra-wide deposition in extrusion additive manufacturing: A new convention for improved interlayer mechanical performance. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 61, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moetazedian, A.; Budisuharto, A.S.; Silberschmidt, V.V.; Gleadall, A. CONVEX (CONtinuously Varied EXtrusion): A new scale of design for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Park, H.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, P.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Seo, Y.B.; Kim, D.Y.; Ajiteru, O.; Lee, O.J. A 4-axis technique for three-dimensional printing of an artificial trachea. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 15, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cristescu, R.; Chrisey, D.B.; Narayan, R.J. Solvent-based extrusion 3D printing for the fabrication of tissue engineering scaffolds. Int. J. Bioprint. 2020, 6, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonawala, K.; Zhang, B. Influence of 3D printing process parameters and design on mechanical properties of tissue scaffolds. MATEC Web Conf. 2025, 413, 08003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarso, R.; Anggoro, P.; Ismail, R.; Jamari, J.; Bayuseno, A. Application of fused deposition modeling (FDM) on bone scaffold manufacturing process: A review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.; Olawuni, D.; Kimbell, G.; Badruddoza, A.Z.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Sultana, T. Polymers for extrusion-based 3D printing of pharmaceuticals: A holistic materials–process perspective. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Robles, J.; Martin, N.K.; Fong, M.L.; Stewart, S.A.; Irwin, N.J.; Rial-Hermida, M.I.; Donnelly, R.F.; Larrañeta, E. Antioxidant PLA composites containing lignin for 3D printing applications: A potential material for healthcare applications. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.; Sharma, A.; Tyagi, P.; Beniwal, C.S.; Mittal, G.; Jamini, A.; Singh, H.; Tyagi, A. Fabrication of three-dimensional bioactive composite scaffolds for hemostasis and wound healing. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moetazedian, A.; Candeo, A.; Liu, S.; Hughes, A.; Nasrollahi, V.; Saadat, M.; Bassi, A.; Grover, L.M.; Cox, L.R.; Poologasundarampillai, G. Versatile microfluidics for biofabrication platforms enabled by an agile and inexpensive fabrication pipeline. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2300636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.Q.; Shahriar, S.S.; Yan, Z.; Xie, J. Recent advances in functional wound dressings. Adv. Wound Care 2023, 12, 399–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badekila, A.K.; Kini, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Fabrication techniques of biomimetic scaffolds in three-dimensional cell culture: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 741–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynamism. Eco-PLA Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://asset.dynamism.com/media/catalog/product/pdf/Dynamism_PLA_TDS.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- RS Components Ltd. Verbatim 1.75 mm White PLA 3D Printer Filament. Available online: https://uk.rs-online.com/web/p/3d-printing-materials/8226459 (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- BigRep GmbH. BVOH 3D Printing Support Material. Available online: https://bigrep.com/filaments/bvoh (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Daemon3DPrint. Kexcelled THE K6™ BVOH Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.daemon3dprint.com/media/sparsh/product_attachment/THE_K6_BVOH_TDS.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2026).

- Verbatim. Verbatim 1.75 mm Transparent BVOH 3D Printer Filament. Available online: https://uk.rs-online.com/web/p/3d-printing-materials/2020419 (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Dynamism. Technical Data Sheet—PVA. Available online: https://asset.dynamism.com/media/catalog/product/pdf/Dynamism_PVA_TDS.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- 3D4Makers. Facilan™ PCL 100 Filament. Available online: https://www.3d4makers.com/products/facilan-pcl-100-filament?srsltid=AfmBOorVOmOn5hHBSLjRPp-9saRiYylpWr2f_FXgrVsJDu6c0h8oWBSc (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Gleadall, A. FullControl GCode Designer: Open-source software for unconstrained design in additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moetazedian, A.; Gleadall, A.; Han, X.; Ekinci, A.; Mele, E.; Silberschmidt, V.V. Mechanical performance of 3D printed polylactide during degradation. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottenio, M.; Tran, D.; Annaidh, A.N.; Gilchrist, M.D.; Bruyère, K. Strain rate and anisotropy effects on the tensile failure characteristics of human skin. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 41, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo-Rabina, A.; Paramés-Estevez, S.; Concheiro, A.; Pérez-Muñuzuri, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C. Effect of wound dressing porosity and exudate viscosity on the exudate absorption: In vitro and in silico tests with 3D printed hydrogels. Int. J. Pharm. X 2024, 8, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, C.; Azagury, A.; Shin, H.; Baker, C.M.; Ly, E.; Lee, R.; Mathiowitz, E. The effect of temperature and pressure on polycaprolactone morphology. Polymer 2020, 191, 122227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paetzold, R.; Coulter, F.B.; Singh, G.; Kelly, D.J.; O’Cearbhaill, E.D. Fused filament fabrication of polycaprolactone bioscaffolds: Influence of fabrication parameters and thermal environment on geometric fidelity and mechanical properties. Bioprinting 2022, 27, e00206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gleadall, A.; Belton, P.; Mcdonagh, T.; Bibb, R.; Qi, S. New insights into the effects of porosity, pore length, pore shape and pore alignment on drug release from extrusionbased additive manufactured pharmaceuticals. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 527-1:1996; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties: General Principles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Bažant, Z.P. Size effect on structural strength: A review. Arch. Appl. Mech. 1999, 69, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Q.L.; Choong, C. Three-dimensional scaffolds for tissue engineering applications: Role of porosity and pore size. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2013, 19, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, S.J. Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlsten, A.; Stracuzzi, A.; Lüchtefeld, I.; Restivo, G.; Lindenblatt, N.; Giampietro, C.; Ehret, A.E.; Mazza, E. Multiscale mechanical analysis of the elastic modulus of skin. Acta Biomater. 2023, 170, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, L.; Chen, H.; Ventikos, Y.; Narayan, R.J.; Huang, J. Finite element evaluations of the mechanical properties of polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite scaffolds by direct ink writing: Effects of pore geometry. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 104, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breish, F.; Hamm, C.; Andresen, S. Nature’s load-bearing design principles and their application in engineering: A review. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, H.; Du, J.; He, Y. Biomechanics and Mechanobiology of Additively Manufactured Porous Load-Bearing Bone Implants. Small 2025, 21, 2409955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademakers, T.; Horvath, J.M.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; LaPointe, V.L. Oxygen and nutrient delivery in tissue engineering: Approaches to graft vascularization. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 1815–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Computational fluid dynamics analysis of the fluid environment of 3D printed tissue scaffolds within a perfusion bioreactor: The effect of pore shape. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 49, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Yang, M.; Ruan, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wen, F.; Hong, X. Hierarchically Porous Microgels with Interior Spiral Canals for High-Efficiency Delivery of Stem Cells in Wound Healing. Small 2025, 21, 2405648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Yang, H.; Hong, C.; Wu, X.; Dai, H. Design and characterization of 3D printed gradient scaffolds with spatial distribution of pore sizes. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 12185–12196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, A.A.; Chakraborty, A.; Shamiya, Y.; Ravi, S.P.; Paul, A. Leveraging the advancements in functional biomaterials and scaffold fabrication technologies for chronic wound healing applications. Mater. Horiz. 2022, 9, 1850–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasheva, F.; Adilova, L.; Dyussenbinov, A.; Yernaimanova, B.; Abilev, M.; Akilbekova, D. Optimizing scaffold pore size for tissue engineering: Insights across various tissue types. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1444986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.