Abstract

In this paper, complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) circuit realization of a low-pass elliptic filter of order (1 + α) is realized using the inverse follow-the-leader feedback (IFLF) topology. The transfer functions to approximate the passband and stopband ripple characteristics of the second-order elliptic low-pass filter are synthesized using the nonlinear least squares (NLS) optimization routine. The elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are designed using a cross-coupled operational transconductance amplifier (OTA) in the United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) 180 nm CMOS process. The dynamic range of the filter was found to be 49.7 dB, 52.08 dB, and 54.02 dB for an order of 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, respectively. The circuit simulation results such as magnitude, phase, transient, and group delay plots, are validated with the MATLAB simulation plots. Monte Carlo and PVT analyses have demonstrated the accuracy and robustness of the design. The proposed approach supports quality education and industry, innovation, and infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Continuous time (CT) filters play a vital role in signal processing, serving to extract desired signal components while attenuating undesired or noise-related components from the input signal. Frequency-selective applications such as ECG, EEG, sensor systems, acoustic systems, control systems, robotics, automation, and military or submarine communications demand suitable filters. To enhance performance across these domains, the design of analog filters has increasingly incorporated fractional calculus [1,2], leading to the development of fractional order (FO) filters. Fractional calculus, which generalizes differentiation and integration to non-integer orders, has enabled significant advancements in the aforementioned applications. The distinctive features of fractional-order filters—such as constant phase response, tunable stopband notch frequency and gain [3], passband shaping [4], and stopband ripple control [5]—have made them an attractive area of research. The improvement in the accuracy of passband and stopband shaping has been achieved by incorporating asymmetrical frequency bands into the optimization routine [6]. Furthermore, critical parameters such as the half-power frequency and quality factor can be orthogonally controlled [7].

In general, filter circuits are designed using transfer functions rather than time-domain representations, and this approach remains valid when fractional-order concepts are incorporated in the design process. Fractional-order capacitors (FOCs) serve as essential components of fractional-order systems. Although FOCs are not yet commercially available, significant research efforts are underway to realize their practical implementation [8,9]. Since ideal fractional-order capacitors (FOCs) are not yet realizable, several approximation techniques have been developed to implement fractional-order filters effectively. At present, fractional-order elements are emulated using RC networks over a limited frequency range [10,11]. Various techniques, such as fractional-order capacitor (FOC) or fractional-order inductor (FOL) emulation [12,13], and integer-order approximations based on polynomial coefficient fitting, have been employed to obtain network-realizable transfer functions [14,15,16]. A detailed analysis of fractional-order analog filter realizations and implementation strategies can be found in [2].

CMOS-based realization of the elliptic fractional-order filter remains unexplored in the literature. In this study, a fractional-order elliptic filter of order (1 + α), representing a generalized second-order filter with a 3 dB passband ripple and a 50 dB stopband ripple, is designed. The proposed fractional-order elliptic filter is implemented using the inverse follow-the-leader feedback (IFLF) configuration. This study employs a cross-coupled CMOS operational transconductance amplifier (OTA) [15,17] for the realization of the fractional-order filter. The transconductance of the OTA can be controlled by varying either the biasing current or the external resistor, providing flexibility in filter tuning. In realizing the fractional-order filter (FOF), the term is approximated by a rational transfer function using methods such as Oustaloup, Matsuda, Valsa, or CFE [18]. The circuit complexity and the accuracy of both magnitude and phase responses are largely determined by the type and order of the approximation employed. Compared to the Oustaloup, Valsa, and Matsuda methods, the CFE approximation yielded results that more closely matched the expected response around the half-power and right phase frequencies [18]. To realize an approximated elliptic fractional order filter, the coefficients are computed using the fotf (fractional order transfer function) optimization routine [4,5,19].

The design methodology of the elliptic fractional-order filter, including numerical analysis, least-squares curve fitting, and transfer function approximations, is presented in Section 2. The CMOS circuit realization of the elliptic fractional-order filter using a cross-coupled OTA is discussed in Section 3. The simulation results and performance parameters, and concluding remarks are presented in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively.

2. Design of the Elliptic Fractional Order Filter

2.1. The Literature on the Elliptic Fractional Order Filter

Elliptic filters are extensively used in biopotential signal acquisition [20,21] due to their sharp frequency selectivity and high roll-off rate, enabling effective noise suppression within a limited bandwidth. The precise amplitude and phase control of elliptic FoFs make them ideal for applications such as ECG, EEG, and EMG signal processing. Elliptic fractional-order filters (FOFs) [6,19] are considered to be superior to other fractional filter types (Butterworth, Chebyshev-I/II, Bessel, etc.) because they simultaneously exploit elliptic optimality and fractional-order flexibility. Elliptic FOFs give the sharpest roll-off with the smallest order. The elliptic FOFs provide a superior stopband and precise control over notch depth (due to fractional zeros) in comparison to other FOFs like Butterworth and Bessel. The elliptic FOFs offer improved interference rejection and a higher stopband attenuation rate per decade, which are particularly beneficial in mixed-signal circuit design, biomedical and sensor interfaces, and noise-limited communication front ends.

The design and validation of a (1 + α) low-pass elliptic FO analog filter response [19] was studied using MATLAB ® R2024a. Further, responses of a (1 + α) low-pass elliptic FOF were validated using SPICE [6] using two op-amp topologies realized with approximated fractional-order capacitor (FOC) implementation using Foster 1 topology. Ashu Soni et al. [22] have discussed the effect of bandwidth on the FO elliptic filter and observed that the fractional and integer order elliptic filter gives a better response as compared to the Chebyshev filter in the terms of order reduction and stability. Further, the SPICE simulation of a (1 + α)-order low-pass elliptic filter using a fractional capacitor [23] has been considered. A CMOS-based realization of the elliptic fractional-order filter has not been addressed in existing studies.

The synthesis of elliptic FOFs can be carried out using optimization-based techniques, including least-squares curve fitting and the fitmagfrd frequency-response fitting function, which employs nonlinear least-squares optimization to match the desired magnitude response [6,19]. These elliptic FOF filters were realized using op-amp and passive RC ladder networks (approximating the FoC component). The integer-order approximation of the fractional-order transfer function is discussed next.

2.2. Overview

The specification set of a low-pass filter [24] is given by

where are the passband edge frequency (Hz) and the stopband edge frequency (Hz), respectively, and are normalized from 0 to 1. represent the maximum allowable ripple in the passband (dB) and minimum stopband attenuation (dB), respectively.

A second-order elliptic filter can be realized with a low-pass notch (LPN) circuit, which is characterized by

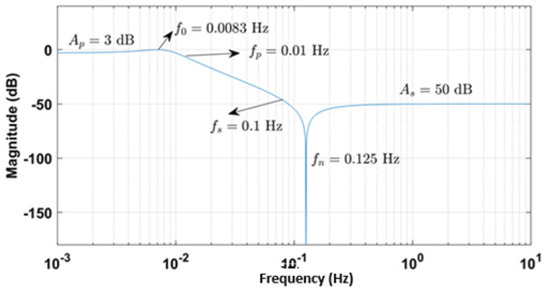

k is the gain factor. A second-order elliptic filter was designed to meet the specifications of a 0.01 Hz passband edge, 0.1 Hz stopband edge, 3 dB passband ripple, and 50 dB stopband attenuation. The specifications of the normalized elliptic biquad filter are presented in Table 1, while the corresponding magnitude response obtained from MATLAB simulations is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Specification details of a second-order normalized elliptic filter.

Figure 1.

Simulated magnitude response of second-order low-pass elliptic filter for specification details in Table 1.

The transfer function of the normalized second-order elliptic filter realized using the LPN circuit for the specifications in Table 1 is given by

The MATLAB Control System Toolbox supports the creation of transfer function models with specified frequency and attenuation parameters. The function ellipord determines the minimum filter order (N) and cut-off frequency required to meet the given design specifications, while ellip computes the numerator and denominator coefficients of the corresponding filter transfer function. A DC gain of −3 dB and a high-frequency gain (HFG) of −50 dB are anticipated for the desired response. To obtain such a magnitude characteristic, both poles and zeros are required to realize the specified ripples in the passband and stopband. In contrast, Butterworth and Chebyshev filters utilize only poles for their realization, thereby distinguishing them from the elliptic filter, which incorporates zeros in addition to poles. The fractional-order (1 + α) transfer function, when approximated using a second-order model, provides a close representation of the desired passband and stopband ripple characteristics and enables the realization of fractional-order poles and zeros.

The fractional-order filters can be synthesized using the lsqcurvefit function, a nonlinear optimization tool that approximates the desired filter characteristics by fitting a mathematical model to the given data points.

2.3. Least-Squares Fitting Function

The fractional-order filters are synthesized using the lsqcurvefit function, a nonlinear optimization algorithm that approximates the desired filter characteristics by fitting a mathematical model to the given data points. The optimal coefficients of the elliptic low-pass filter are determined through the following procedure:

- Defining the transfer function incorporating the fractional-order terms along with the corresponding coefficients.

- Specifying the target frequency response characteristics based on the design specifications provided in Equation (3) and illustrated in Figure 1.

The lscurvefit function in MATLAB is used to minimize the difference between the actual model and the desired response by adjusting the coefficients, as given in (5)

where is the elliptical fractional order filter given in (4) and is the second-order elliptic filter given in (3).

2.3.1. Stability

The mapping from the plane to the W plane [16,25] yields the following characteristic equation:

where and m, k > 0 are integers.

The roots of (6) were computed for to with , yielding in the range of 16.37° to 9.49°. These results satisfy the minimum root condition (i.e., 9°), confirming that each transfer function obtained using the coefficients of the derived fractional-order filter is stable [25]. However, when (i.e., 18°), the corresponding systems are not physically realizable [26]. Table 2 presents the coefficients of the fractional-order filter polynomials corresponding to orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, which form the basis for the subsequent filter circuit implementation.

Table 2.

Coefficient values for (1 + ) fractional-order elliptic filter.

2.3.2. Transfer Function Approximation

Fractional-order filters utilize the fractional Laplacian operator, expressed as , in contrast to integer-order filters that use the integer-order operator . The approximation is limited to the second order and substituting from [27] yields the Laplacian term given by

The design equation for coefficients [27] in (7) are given as

The integer-order approximation of the fractional-order elliptic filter with order (1 + α) is expressed as

where

2.3.3. Functional Block Diagram

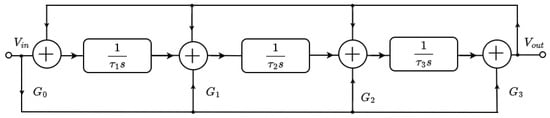

The integer-order approximated fractional-order transfer function of the elliptic filter in (9) was implemented using the functional block diagram shown in Figure 2, which is based on the inverse follow-the-leader feedback (IFLF) topology.

Figure 2.

Functional block diagram of IFLF topology.

The transfer function for the filter structure in Figure 2 is shown to be

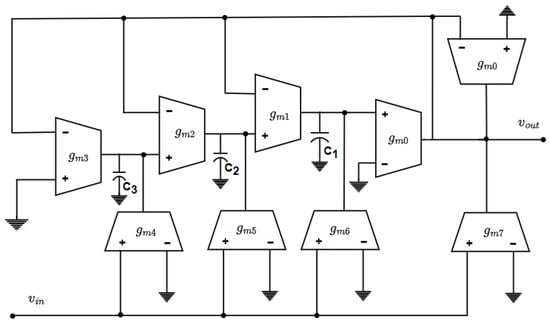

2.3.4. OTA-C Circuit Realization of Fractional-Order Low-Pass Elliptic Filter

The OTA and capacitance (OTA-C) circuit realization of the fractional-order low-pass elliptic filter of order (1 + α) is shown in Figure 3. The values of feedforward factors (i = 0, 1, 2, 3) and time constants (i = 0, 1, 2) in the functional block diagram of Figure 2, obtained by equating the polynomial coefficients in (12) and (9), are listed in Table 2.

Figure 3.

OTA-C realization of fractional order elliptic LPF of order (1 + α).

The expressions for the feedforward factors and the time constants in terms of transconductances and capacitances of the OTA- C circuit in Figure 3 are given as follows:

3. CMOS Circuit Realization of the Fractional-Order Elliptic Filter

The fractional-order elliptic filters with orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 were synthesized and realized in the UMC 180 nm CMOS process. The design employs a cross-coupled OTA architecture with an integrated common-mode feedback circuit to ensure stable operation.

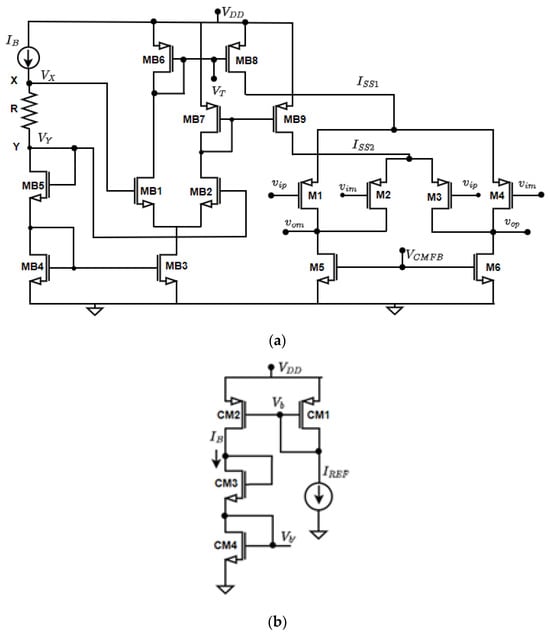

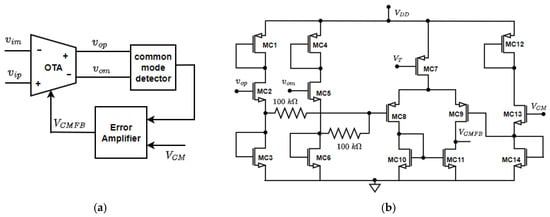

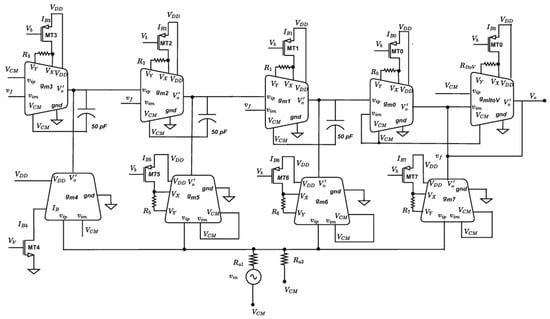

3.1. CMOS OTA Architecture

The schematic of the cross-coupled (CC) CMOS OTA [17] with its biasing network, used in the realization of the fractional-order elliptic low-pass filter (LPF), is shown in Figure 4a. The required bias currents ( are mirrored from the basic current mirror circuit shown in Figure 4b. The reference current can be generated using precision current reference circuits such as the Proportional to Absolute Temperature (PTAT) [28,29,30] and Complementary to Absolute Temperature (CTAT) [31,32].

Figure 4.

(a) CMOS circuit of CC-OTA with tail current generation [17], (b) current mirror circuit used to realize .

The effective transconductance of the OTA can be tuned by varying the resistor R connected between nodes X and Y, for a given bias current The overall transconductance of the CC-OTA is determined as the difference between the transconductances of the two source-coupled PMOS differential pairs (M1–M4 and M2–M3), and is expressed as

where and are transconductances of PMOS differential pairs M1–M4 and M2–M3, respectively, which are operated in the sub-threshold region.

The overall transconductance of the CC-OTA is obtained as the difference between the individual transconductances, which serves as an effective technique for achieving low transconductance values. The aspect ratio of MOS transistors (M1–M6 and MB1–MB9) used in CC-OTA for realization of different transconductances to (except ) in Figure 3 are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Transistor size of CC-OTA.

3.2. Common-Mode Feedback Circuit

The common-mode feedback (CMFB) concept and circuit [33,34] employed to regulate the DC operating point of the fully differential OTA of Figure 4 is shown in Figure 5. The CMFB circuit regulates the common-mode output level of the fully differential OTA by sensing the average of and through the resistive network and comparing it with the reference . The sensing and error-amplifying transistors (MC8–MC11) generate the control voltage , which adjusts the bias voltage of devices M5–M6 (in Figure 4) to restore the desired common-mode voltage. The transistor size details in CMFB circuit of Figure 5b are given in in Table 4. All of the transistors are working in the saturation region.

Figure 5.

Common-mode feedback scheme: (a) block diagram, (b) CMOS circuit diagram.

Table 4.

Transistor size for common-mode feedback circuit in Figure 5b.

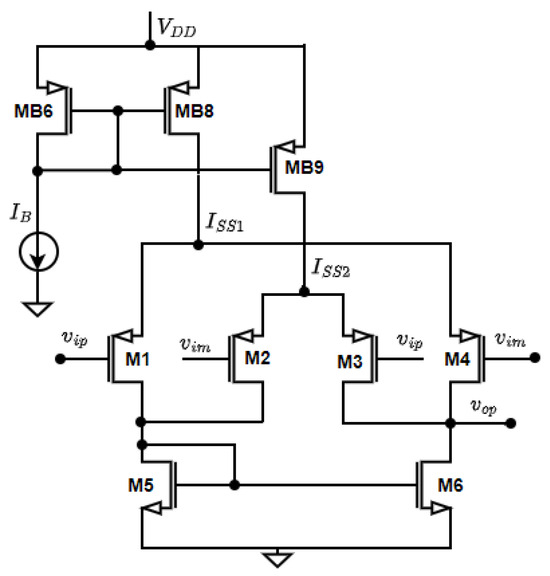

4. Simulation Results

The schematic entry and circuit simulations of the fractional-order (FO) elliptic filter of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 (Figure 2) were carried out using the Cadence Virtuoso ® 6.1.6 with Spectre ® circuit simulator (Cadence Design Systems, USA) with UMC 180 nm CMOS technology at a 1.8 V supply. The complete schematic of the FO elliptic filter implemented in Virtuoso is shown in Figure 6. In this design, and represent the common-mode control voltage and the OTA bias current, respectively, while the resistors are used to tune the transconductances of the OTAs employed in the filter architecture of Figure 2. The final design parameters for the FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 used in the simulations are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 6.

CC-OTA-based elliptic filter of order (1 + realised in Cadence Virtuoso.

Table 5.

Design values of circuit elements for FO elliptic filter of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8.

A large value of was realized using the OTA circuit in Figure 7 without tail current generation and with the different transistor dimensions listed in Table 6.

Figure 7.

The OTA circuit for without tail current generation circuit without CMFB.

Table 6.

The transistor size of the OTA for different fractional orders.

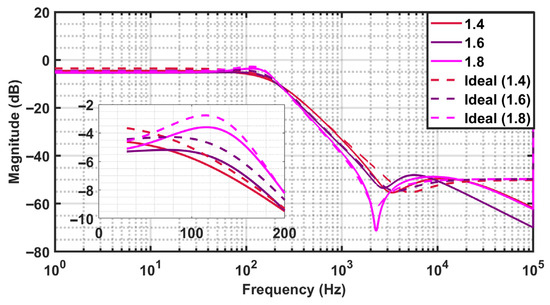

4.1. Amplitude Response

The amplitude (in dB) associated with the numerically evaluated ideal transfer functions and the Spectre-simulated implementations of the FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 in Table 7 confirm a high degree of consistency. Figure 8 presents the amplitude responses of FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, comparing the theoretically synthesized responses with the corresponding circuit-level simulation results. A focused view near the cut-off frequency reveals variation between the ideal and simulated responses of 5.82% {(−7.39 + 6.9)/6.9} for a fractional order 1.4. at 150 Hz frequency, 10.8% {(−8.2 + 7.4)/7.4} for a fractional order of 1.6 at 180 Hz, and 0.68% {(−8.2 + 8.256)/8.256} for a fractional order of 1.8 at 200 Hz. The ideal cut-off frequencies for the fractional orders of 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are 140 Hz, 179.4 Hz, and 194 Hz, respectively. The corresponding cut-off frequencies obtained from the Spectre-simulated amplitude responses are 152 Hz, 182 Hz, and 199 Hz, resulting in errors of 8.57%, 1.4%, and 2.57%, respectively. The small deviations observed in the Spectre-simulated responses relative to the ideal curves are primarily attributed to the finite output resistance of the OTA and other practical non-idealities, including component tolerances.

Table 7.

Magnitude, phase, and group delay of the output waveform of fractional order elliptic filter of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, across a range of frequencies.

Figure 8.

Ideal and simulated magnitude responses of fractional-order elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, obtained using MATLAB and Cadence Spectre.

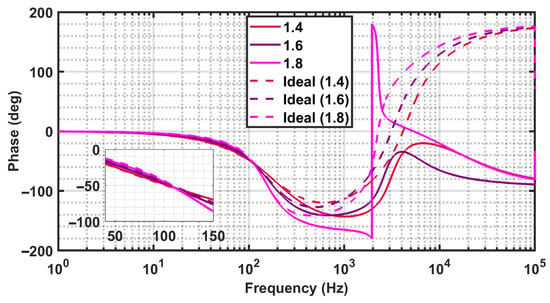

4.2. Phase Response

The numerically synthesized ideal phase responses (MATLAB) and the corresponding simulated phase responses (Cadence Spectre) are shown in Figure 9. The phase responses corresponding to the ideal transfer functions and the simulated implementations for the fractional-order elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are summarized in Table 7. As can be seen from the phase plot, the phase varies smoothly with an approximately linear trend across the passband, reflecting the controlled dynamic response of the synthesized filter. A pronounced phase transition (phase reversal) occurs at the notch frequency of 2.1 kHz, for the case of a 1.8 fractional order.

Figure 9.

Ideal and simulated phase responses of FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, obtained using MATLAB and Cadence Spectre.

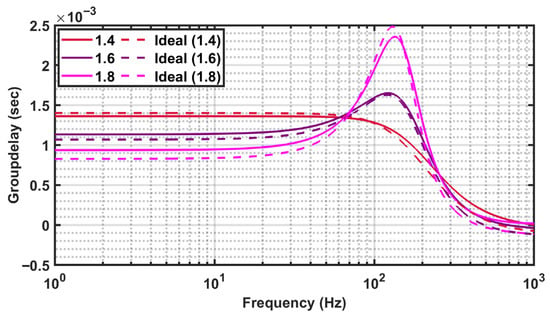

4.3. Group Delay

Group delay (GD) plots for FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 for numerically synthesized ideal responses and circuit-level Spectre simulations are presented in Figure 10. The GD values of the FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 for both the ideal transfer function and the simulated implementation are summarized in Table 7. The plots show preservation of the linear phase over the passband and deviations near the notch frequencies due to practical nonidealities. The nearly linear group delay observed in the passband minimizes waveform distortion, a requirement that is especially important in biomedical signal processing applications—such as ECG, EEG, and EMG—where accurate preservation of temporal features directly affects diagnostic reliability.

Figure 10.

Group delay of the FO elliptic filter of orders 1.4, 1.6, 1.8: numerical synthesis versus circuit-level Spectre simulation.

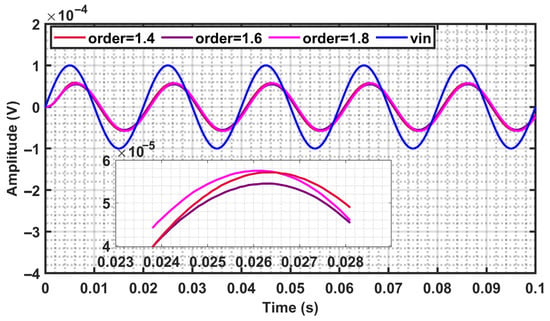

4.4. Transient Response

The transient simulation of the FO elliptic filter for fractional orders of 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 was performed using a 50 Hz sinusoidal input signal with a peak-to-peak amplitude of 200 µV, and the resulting time-domain waveforms are shown in Figure 11. The output signals closely follow the input waveform in both shape and frequency, while exhibiting the expected level of attenuation. These time-domain results complement the frequency-domain analysis, further validating the correctness of the filter implementation and confirming its suitability for real-time analog signal-processing applications.

Figure 11.

Transient response of the FO elliptic filters with orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, obtained for a 200-µV peak-to-peak sinusoidal input signal at 50 Hz.

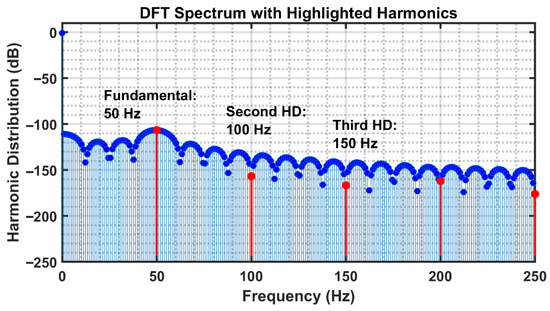

4.5. Harmonic Spectrum

The plot of the harmonic spectrum of the FO elliptic filter of order 1.8 is shown in Figure 12. The fundamental component appears at 50 Hz with the highest amplitude, while the subsequent harmonic occurs at an integer multiple of this frequency and exhibits a lower amplitude than the fundamental component. For a sinusoidal input voltage of 200 µV and frequency of 50 Hz, THD is found to be 0.5% (less than 1%).

Figure 12.

Simulated harmonic spectrum of the FO elliptic filter of order 1.8 with a 200 µV p-p input signal at 50 Hz.

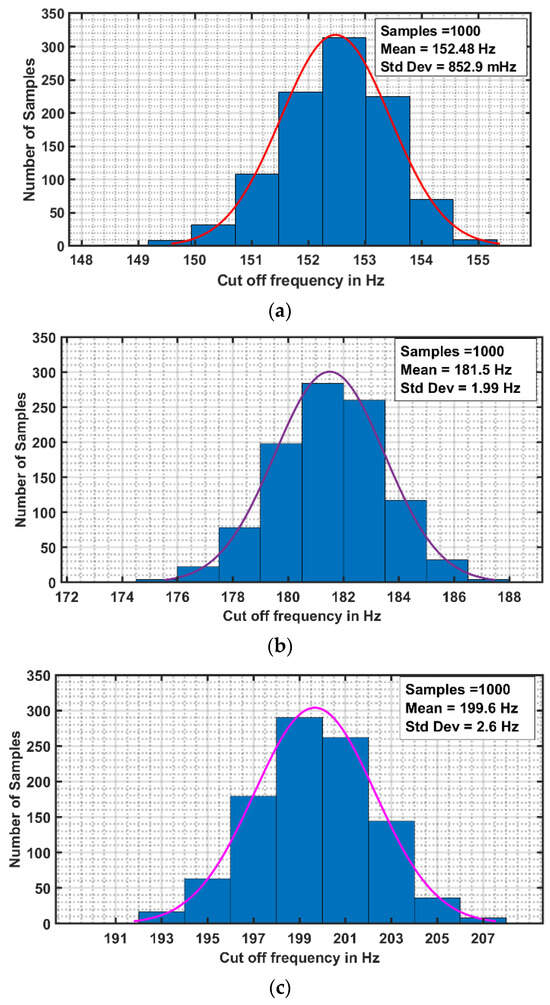

4.6. Monte Carlo Results

Monte Carlo simulations were performed for the FO elliptic filters shown in Figure 6, for orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, with 1000 iterations each, to evaluate the impact of process variations and device mismatch on the cut-off frequency. The resulting plots are presented in Figure 13a–c. From the Gaussian distribution curves for the different orders, shown in distinct colors, it is evident that the pole frequency exhibits minimal variation under process-induced deviations. The mean cut-off frequencies for the fractional orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are 152.48 Hz, 181.5 Hz, and 199.6 Hz, respectively, and the corresponding Gaussian distributions are well centered around their respective means. The standard deviation (SD) values of the cut-off frequency for fractional orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are 0.852 Hz, 1.9 Hz, and 2.6 Hz, respectively.

Figure 13.

Monte Carlo simulation plots of FO elliptic filter of orders (a) 1.4, (b) 1.6, and (c) 1.8 with respect to cut-off frequency .

.

4.7. Effect of PVT and

Variations

The implemented FO elliptic filter for fractional orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 were simulated under various PVT (process, voltage, temperature) variations to assess its robustness and performance consistency.

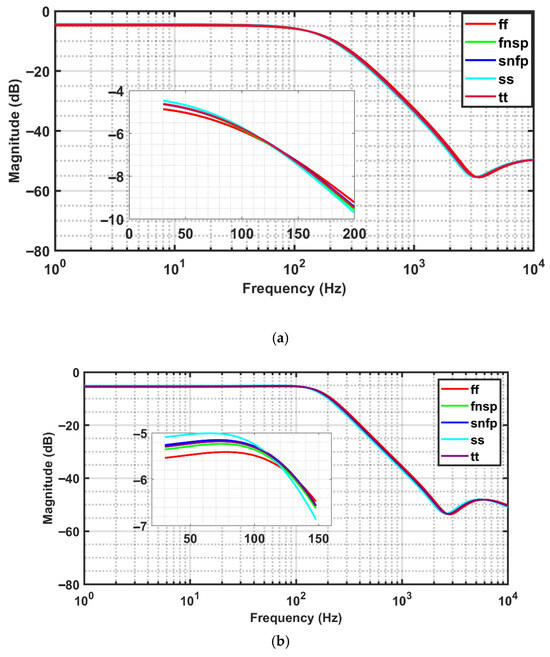

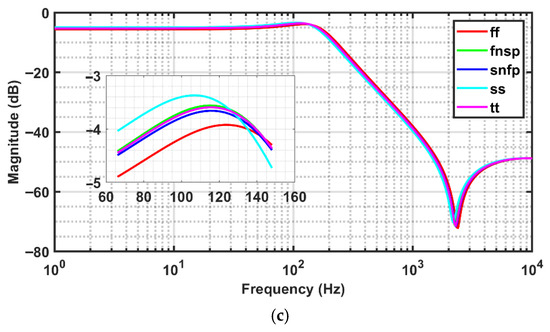

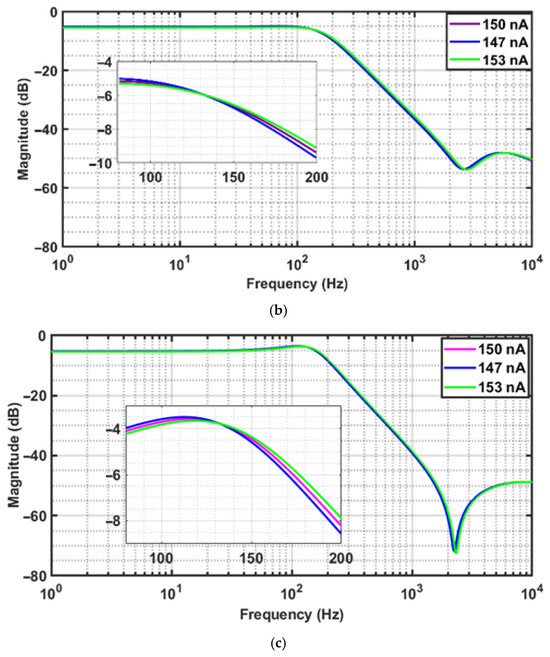

The FO elliptic filters of orders (a) 1.4, (b) 1.6, and (c) 1.8 shown in Figure 6 were simulated across five standard process corners (FF, SNFP, TT, FNSP, and SS) at a temperature of 27 °C and an operating voltage of 1.8 V. The resulting amplitude-response plots are presented in Figure 14a–c. The four standard process corners (FF, SNFP, FNSP, and SS) were compared with the Typical–Typical (TT) corner, which lies at the center of the variation range, and the overall deviation remains within 10%. As the filter order increases, the percentage error in gain also increases.

Figure 14.

(a–c). Magnitude response of the FO elliptic filter of orders (a) 1.4, (b) 1.6, and (c) 1.8 under different process (P) corners (FF, SNFP, TT, FNSP, and SS) at temperature of 27 °C and an operating voltage of 1.8 V.

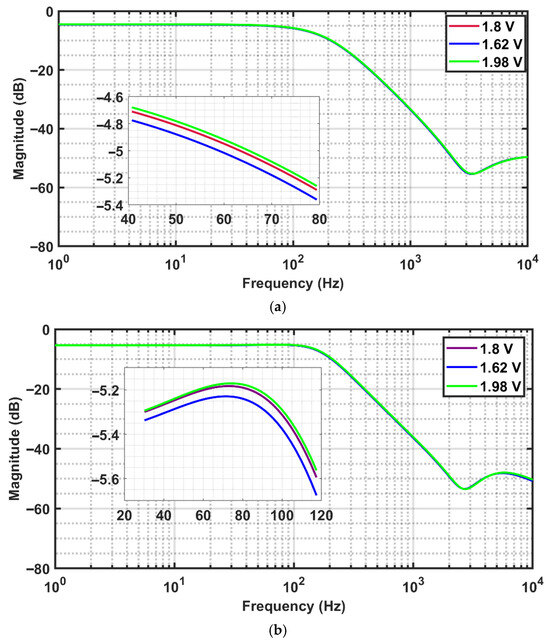

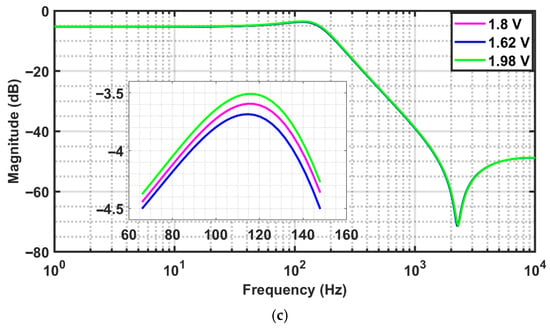

The implemented FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 were subjected to a 10% variation in the 1.8 V DC supply voltage (i.e., 1.62 V, 1.8 V, and 1.98 V) at room temperature under the TT process corner. The resulting magnitude-response plots are shown in Figure 15a–c, and the responses are observed to be consistent across the voltage variations. As is indicated in Table 8, the maximum percentage deviation due to voltage variations is 2.2%.

Figure 15.

(a–c). Magnitude response of the FO elliptic filter of orders (a) 1.4, (b) 1.6, and (c) 1.8, with respect to 10% voltage variations in 1.8 V DC voltage (1.62, 1.8, 1.98 V) at temperature of 27 °C and at Typical–Typical process corner.

Table 8.

Summary of effect of PVT and variations on amplitude response of FO elliptic filter of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8.

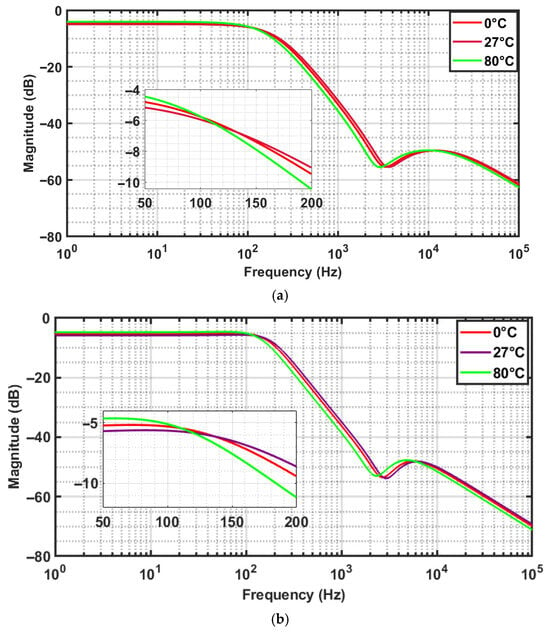

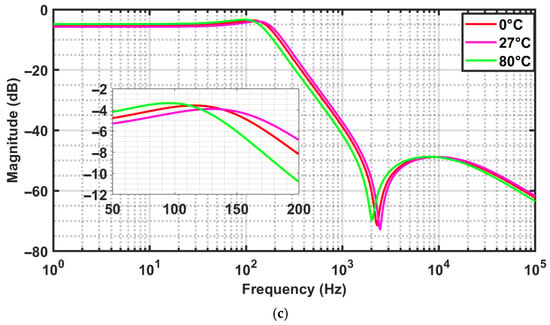

The simulations are carried out for implemented FO elliptic filters in Figure 6 with a variation in temperature of 0 °C, 27 °C, and 80 °C at the TT process corner, and 1.8 V DC voltage resulting amplitude-response plots of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are shown in Figure 16a–c. From these plots, the magnitude variation with respect to temperature variations is seen to increase with the increase in order.

Figure 16.

(a–c). Magnitude response of the FO elliptic filter of orders (a) 1.4, (b) 1.6, and (c) 1.8, with respect to temperature 0 °C, 27 °C, and 80 °C at DC voltage 1.8 V and Typical–Typical process corner.

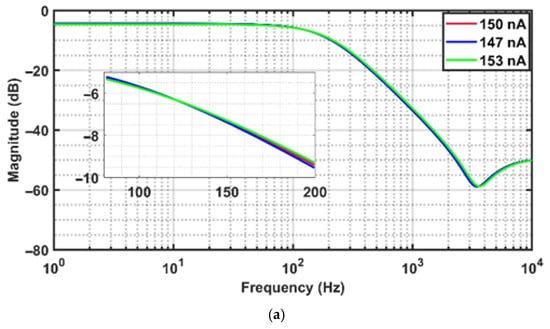

The implemented FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 were subjected to a 2% variation in at the TT process corner, 1.8 V DC supply voltage, and 27 °C room temperature. The resulting magnitude-response plots are shown in Figure 17a–c, and the responses are observed to be consistent across the variations. As is indicated in Table 8, the maximum percentage amplitude deviation due to ±2% variations are seen to be 5.8%.

Figure 17.

(a–c). Magnitude response of the FO elliptic filter of orders (a) 1.4, (b) 1.6, and (c) 1.8, with respect to 2% variations at Typical–Typical process corner, DC voltage 1.8 V, and a temperature of 27 °C.

A consolidated summary of the effect of PVT variations and variations on amplitude response for these three filter orders is presented in Table 8.

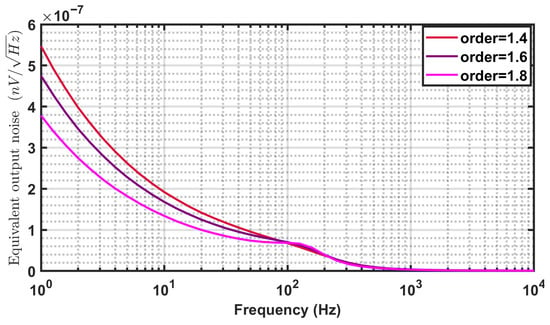

4.8. Output Noise

Figure 18 illustrates the simulated output noise voltage of the FO elliptic filter. The results indicate that flicker noise is the predominant contributor up to approximately 50 Hz, beyond which thermal noise becomes the major component. At 50 Hz, the equivalent output noise levels for the filter orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are 95.5 nV, 88 nV, and 73.9 nV, respectively.

Figure 18.

Output noise response of the FO elliptic filter shown in Figure 6 for filter orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8.

5. Evaluation of Performance Metrics

The key performance metrics of the FO elliptic filters shown in Figure 6, as obtained from Cadence Spectre simulations for orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Summary of performance metrics of FO elliptical filter of orders 1.4, 1.6 and 1.8.

Dynamic range: The dynamic range (DR) of the filter, evaluated using (15), is found to be approximately 49.7 dB, 52.08 dB, and 54.02 dB for the FO elliptic filter orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8, respectively, corresponding to 0.6% total harmonic distortion (THD).

Figure of merit (FOM): The figure of merit (FOM) [35] used is as given in (16).

where DR, P, and N are the dynamic range, power, cut-off frequency, and order of the filter, respectively. The FOM for the FO elliptic filter orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are found to be 2093, 1186 and 875 pJ, respectively.

From the simulation results in Figure 8, the stopband attenuation rate is observed to increase significantly with a higher α. A moderate variation in the stopband ripple and the attenuation at the notch frequency is also noted with changes in filter order. As the filter order increases, the required transconductance values decrease, except for (Table 5), resulting in lower bias currents and reduced power consumption. This trend is confirmed in Table 9, where the total power decreases with increasing α value. Furthermore, a higher filter order yields lower input-referred noise, thereby improving the dynamic range (DR). The figure of merit (FOM) also decreases with increasing α value due to the reduction in power consumption.

A few relevant previously reported research works on FoF are considered for benchmarking the performance metrics of the proposed elliptic FOF. The circuit realization of Butterworth and Chebyshev low-pass and high-pass filters of fractional order () using a single current feedback operational amplifier (CFOA) [36] is reported, with the cut-off frequency being independent of the filter order. The design of current-mode FoFs of various filter types using a multi-output second-generation current-controlled conveyor (MO-CCCII) has been reported by Fadile Sen et al. [37]. Sadaf Tasneem et al. have presented the implementation of a low-voltage, low-power fractional-order low-pass filter (FO-LPF) of order (1 + α) using a voltage differencing differential difference amplifier (VDDDA) [38]. Georgia Tsirimokou et al. have discussed the realization of a companding FoF for ultra-low-voltage applications [39]. Ola I. Ahmed et al. [40] have discussed a novel design technique for a tunable FO band-pass filter of order and its implementation using an OTA. Table 10 presents a summary of the performance parameters (P, THD, IRN, DR, and FOM) of the implemented elliptic FOF, together with comparative data from various fractional-order filter types previously reported in the literature. The THD of the proposed elliptic FOF is lower than that reported in [11,15,36,37,38]. The implemented filter provides an IRN value comparable to that reported in [36] and exhibits improved noise performance (lower IRN) relative to that in [15]. The proposed elliptic FOF provides a higher DR than the design presented in [39]. The power consumption of the implemented elliptic FOF is comparable to that reported in [15] and lower than that in [11,37,40].

Table 10.

Comparison with some FOFs in the literature.

6. Conclusions

An elliptic FO LPF of order (1 + α), for α = 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8, is synthesized using the continued-fraction expansion (CFE) method. The elliptic FOF structures are further optimized using a nonlinear least-squares (NLS) routine to accurately match the desired magnitude response. The FO elliptic filters of orders 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are designed for cut-off frequencies of 151 Hz, 181 Hz, and 200 Hz, respectively, using a 1.8 V supply and a CC-OTA architecture with a resistor-averaged CMFB circuit. The FO elliptic LPF circuits are implemented and simulated in the Cadence IC Design Suite 6.1.8 (Virtuoso/Spectre) using the 180 nm UMC CMOS process. The Spectre-simulated amplitude responses show good agreement with the MATLAB-generated results. Key performance metrics, including THD, DR, Input Referred Noise (IRN), power, and FoM, were evaluated and compared against previously reported designs. The circuit simulation outcomes confirm the robustness and accuracy of the proposed FO elliptic filter architecture. The Monte Carlo analysis shows that variations in the cut-off frequency due to process fluctuations and device mismatch are minimal and remain within acceptable limits. In addition, the THD remains below 1%, and the DR exceeds 49 dB. Although the CFE approximation method and NLS-based curve fitting were employed in this study, alternative approximation techniques, such as Oustaloup, Matsuda, and Valsa, along with optimization tools like fitmagfrd, can also be used. As part of future work, the design methodology can be extended to realize elliptic FOFs of generalized order (n + α).

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.N.; Conceptualization, S.K.; software, C.B.K.; supervision and validation, D.V.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elwakil, A.S. Fractional-Order Circuits and Systems: An Emerging Interdisciplinary Research Area. IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. 2010, 10, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokuş, Y.E.; Koton, J.; Sotner, R.; Kartci, A.; Ayten, U.E. A Review of the State-of-the-Art in Fractional-Order Analog Filters. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2025, 196, 155786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.M.; Kathjoo, M.Y.; Khanday, F.A.; Biswas, K.; Psychalinos, C. A Survey of Single and Multi-Component Fractional-Order Elements (FOEs) and Their Applications. Microelectron. J. 2019, 84, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeborn, T.; Maundy, B.; Elwakil, A.S. Approximated Fractional Order Chebyshev Lowpass Filters. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeborn, T.J.; Elwakil, A.S.; Maundy, B. Approximated Fractional-Order Inverse Chebyshev Lowpass Filters. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 35, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubanek, D.; Freeborn, T.J.; Koton, J.; Dvorak, J. Validation of Fractional-Order Lowpass Elliptic Responses of (1 + α)-Order Analog Filters. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoulea, S.; Yesil, A.; Psychalinos, C.; Minaei, S.; Elwakil, A.S.; Bertsias, P. Fractional-Order and Power-Law Shelving Filters: Analysis and Design Examples. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 145977–145987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, D.; Biswas, K. Packaging of Single-Component Fractional Order Element. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2012, 13, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, A.; Khanra, M.; Sen, S.; Biswas, K. Realization of a Carbon Nanotube Based Electrochemical Fractor. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Lisbon, Portugal, 24–27 May 2015; pp. 2329–2332. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, D.V.; Navya, S.; Soubhagyaseetha, N. Fractional Order OTA -C Current-Mode All-Pass Filter. In Proceedings of the 2018 Second International Conference on Inventive Communication and Computational Technologies (ICICCT), Coimbatore, India, 20–21 April 2018; pp. 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, F.; Kircay, A. Realization of Fractional-Order Current-Mode Multifunction Filter Based on MCFOA for Low-Frequency Applications. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirimokou, G.; Psychalinos, C.; Elwakil, A.S. Emulation of a Constant Phase Element Using Operational Transconductance Amplifiers. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 2015, 85, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirimokou, G.; Kartci, A.; Koton, J.; Herencsar, N.; Psychalinos, C. Comparative Study of Discrete Component Realizations of Fractional-Order Capacitor and Inductor Active Emulators. J. Circuits, Syst. Comput. 2018, 27, 1850170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubhagyaseetha, N.; Kamath, D. V Gm-C Fractional Bessel Filter of Order (1+α). In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Smart Systems and Inventive Technology (ICSSIT), Tirunelveli, India, 27–29 November 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 454–459. [Google Scholar]

- Nettar, S.; Kilingar, S.; Killuru, C.B.; Kamath, D. V Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor Circuit Realization of Inverse Chebyshev Low-Pass Filter of Order (1 + α). Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacu, I.E.; Alci, M. Low-Power OTA-C Based Tuneable Fractional Order Filters. Inf. MIDEM 2018, 48, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Machha Krishna, J.R.; Laxminidhi, T. Widely Tunable Low-Pass Gm−C Filter for Biomedical Applications. IET Circuits Devices Syst. 2019, 13, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, E.; Mabrouk, A.; Said, L.; Radwan, A. Effect of Different Approximation Techniques on Fractional-Order KHN Filter Design. Circuits, Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 37, 5222–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeborn, T.J.; Kubanek, D.; Koton, J.; Dvorak, J. Fractional-Order Lowpass Elliptic Responses of (1+α)-Order Transfer Functions. In Proceedings of the 2018 41st International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Athens, Greece, 4–6 July 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Diab, M.S.; Mahmoud, S.A. A 1.7nW 24 Hz Variable Gain Elliptic Low Pass Filter in 90-Nm CMOS for Biosignal Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Sapporo, Japan, 26–29 May 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Diab, M.S.; Mahmoud, S.A. Field Programmable Analog Arrays for Implementation of Generalized Nth-order Operational Transconductance Amplifier-C Elliptic Filters. ETRI J. 2020, 42, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Gupta, M. Analysis of fractional order low pass Elliptic filters. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), Noida, India, 22–23 February 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Gupta, M. Fractional order elliptic filter implemented using optimization technique. In Cognitive Informatics and Soft Computing: Proceeding of CISC 2020; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; pp. 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutovac, M.D.; Tosic, D.V.; Evans, B.L. Algorithm for Symbolic Design of Elliptic Filters. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference Symbolic Methods, Application, Circuit Design SMACD96, Heverlee, Belgium, 10–11 October 1996; pp. 248–251. [Google Scholar]

- Radwan, A.G.; Soliman, A.M.; Elwakil, A.S.; Sedeek, A. On the Stability of Linear Systems with Fractional-Order Elements. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2009, 40, 2317–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, K.; Kar, S.K.; Tripathy, M.C. Stability Analysis of Fractional-Order Filters Realized with PMMA Coated Elements. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference in Advances in Power, Signal, and Information Technology (APSIT), Bhubaneswar, India, 8–10 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirimokou, G.; Psychalinos, C.; Elwakil, A. Design of CMOS Analog Integrated Fractional-Order Circuits: Applications in Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammed Mansoor, C.B.; Hanumantha Rao, G.; Rekha, S. Low power fast settling switched capacitor PTAT current reference circuit for low frequency applications. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. 2020, 5, 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- Hanumantha, R.G.; Rekha, S. A 0.5 V, 1 nA switched capacitor PTAT current reference circuit. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Modeling of Systems Circuits and Devices (MOS-AK India), Hyderabad, India, 25–27 February 2019; pp. 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hanumantha Rao, G.; Rekha, S. A 0.8-V, 55.1-dB DR, 100 Hz low-pass filter with low-power PTAT for bio-medical applications. IETE J. Res. 2022, 68, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagulapalli, R. A CMOS Self-Bias CTAT Current Generator with Improved Supply Sensitivity. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2019, 28, 1950226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casañas, C.W.V.; de Castro, T.H.P.; de Souza, G.A.F.; Moreno, R.L.; Colombo, D.M. A Review of CMOS Currente References. J. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2022, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, M.; Khoury, J.M.; Tsividis, Y. Fully Differential Operational Amplifiers with Accurate Output Balancing. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2002, 23, 1410–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babanezhad, J.N. A Low-Output-Impedance Fully Differential Op Amp with Large Output Swing and Continuous-Time Common-Mode Feedback. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2002, 26, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, D.V.; George, M.A. New Gm-C All-Pass and Amplitude-Equalizer Biquad. IETE J. Res. 2023, 69, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nako, J.; Psychalinos, C.; Elwakil, A.S. One Active Element Implementation of Fractional-Order Butterworth and Chebyshev Filters. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2023, 168, 154724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, F.; Kircay, A.; Cobb, B.S.; Akgul, A. MO-CCCII-Based Single-Input Multi-Output (SIMO) Current-Mode Fractional-Order Universal and Shelving Filter. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasneem, S.; Ranjan, R.K.; Paul, S.K.; Herencsar, N. Power-Efficient Electronically Tunable Fractional-Order Filter. Fractal Fract. 2023, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirimokou, G.; Laoudias, C.; Psychalinos, C. 0.5-V Fractional-order Companding Filters. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2015, 43, 1105–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.I.; Yassin, H.M.; Said, L.A.; Psychalinos, C.; Radwan, A.G. Implementation and Analysis of Tunable Fractional-Order Band-Pass Filter of Order 2α. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2020, 124, 153343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.