Abstract

Estimation of remaining useful life (RUL) of roller bearings is a prevalent problem for predictive maintenance in manufacturing. However, roller bearings are subject to a variety of factors during their operation. As a result, we deal with a slow nonlinear degradation process, which is long-range dependent, self-similar and has non-Gaussian characteristics. Proper data pre-processing enables us to use Pareto’s probability density function (PDF), Generalized Pareto motion (GPm) and its fractional-order extension (fGPm) as the degradation predictive model. Estimation of the Hurst exponent shows that this model has a long-range correlation and self-similarity. Through the analysis of the uncertainty of the end point of the bearing’s RUL and the prediction process, not only did it verify the high adaptability of fGPm in simulating complex degradation processes but also the criteria for judging self-similarity, and LRD characteristics were established. The case study mainly proves the validity of the theory, providing an effective analytical tool for a deeper understanding of the degradation mechanism.

1. Introduction

Predictive models of the RUL of roller bearings can be divided into two categories: data-driven models and physics-of-failure models [1]. The data-driven prediction method uses the data from monitoring during the entire life cycle of the roller bearing as the training set. By learning these data, a prediction model is constructed, and then the RUL is predicted for new monitoring data. This method effectively avoids the limitations of the prediction, based on the physics-of-failure model. In terms of the bearing data statistical characteristic, RUL can be further divided into statistical data-driven methods and artificial intelligence-based methods [2,3]. The statistical data-driven method analyzes historical failure data through probabilistic and statistical methods to calculate the life distribution of the bearing. Its advantage lies in the relatively small dependence on specific failure models, but it is limited by the need for a large amount of historical data, making the prediction for small-sample data a challenge. The prediction models based on the physics of failure are determined by the theoretical framework of expert knowledge and failure mechanisms. Such methods are limited by the complexity of modeling and the applicability to specific scenarios.

For the RUL prediction, traditional machine learning methods such as regression analysis, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and decision trees [4] are widely adopted. reference [5,6] predicted the degradation trend of resistance through a feed-forward Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and explored the influence of noise and the number of hidden neurons; reference [7,8] used the statistical indicators of the Weibull distribution as the input of the ANN, which reduced the influence of noise; Reference [9] combined an ANN with the fatigue damage accumulation theory to effectively predict the RUL of cranes. However, they have drawbacks such as the problem of local optima, high model design and computational costs, and difficulty in directly expressing prediction uncertainty.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) along with the Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM) represent widely used methods for prediction of the RUL. Harbola et al. [10] developed a one-dimensional CNN model consisting of three convolutional layers and three fully connected layers. The convolutional layers were used to extract features, and fully connected layers were employed to predict the sequence changes. Another approach employs wavelet transformation for extraction of complex information in the time-frequency domain. Then a multi-modal CNN is applied to estimate the RUL [11]. Previous research studies [12,13] successfully predicted the degradation trend of roller bearings by removing the Softmax classification layer in the CNN and introducing three fully connected layers for training. However, a direct description of the temporal input dependence by deep learning models represents a difficulty. To address this issue, study [14] combined multi-scale permutation entropy with LSTM. Multi-scale permutation entropy algorithm was used to detect the abrupt change states of equipment degradation and various trends were input into the LSTM model. According to study [15], the LSTM prediction model for wind turbine roller bearings identifies and analyzes weak fault features in vibration and acoustic signals.

In this paper we develop a prognostic model, which is based on the fundamental notions: non-stationarity and LRD. With the consideration of these features, our approach effectively captures the uncertainties during the degradation process. A number of disadvantages of the existing methods are eliminated and verified by a case study.

The layout of this article is as follows: Section 2 provides the method for calculating long-range dependence and self-similarity. Section 3 deduces a fractional Pareto degradation prediction model and analyzes the model’s characteristics. Section 4 proves the reliability of this prediction model. Section 5 proposes the selection of fault characteristic parameters. Section 6 introduces parameter estimation. Section 7 examines an engineering case. Section 8 gives the conclusion.

2. Long-Range Dependence and Self-Similarity

Recall that if the sum of autocorrelation functions (ACFs) of a discrete-time series does not converge, i.e., , or for a continuous time sequence, then [16,17]. It means that the feature of the LRD in the random time sequence follows a power-law approximation, see Equation (1):

where H is the Hurst exponent, which is used to quantify the strength of self-similarity. The Hurst exponent is calculated by collecting historical data of the degradation process, and its value is (0.5, 1), which meets RLD characteristics.

Self-similarity is a statistical property at different scales or time periods. For a stochastic process, self-similarity is the statistical characteristic to remains unchanged under any scale transformation , shown in Equation (2).

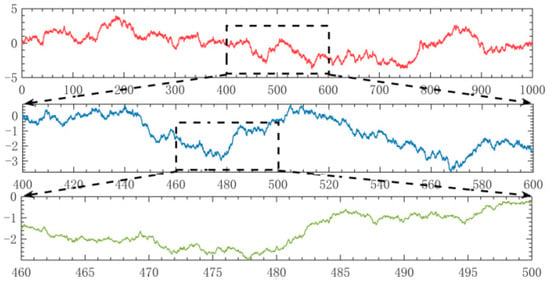

Figure 1 shows characteristics of self-similar time sequence from different observation windows. Local fluctuation patterns can be reflected in the global trend and quantified by the Hurst exponent in multi-scale analysis. It is clear that the Hurst exponent links self-similarity with LRD. This LRD is also known as long-term memory effect or persistence indicating that correlations of the asset degradation increments extend over extensive periods. Therefore, future degradation trends are not only influenced by the current condition of the asset but are also deeply linked to its entire degradation history.

Figure 1.

Typical self-similar raw data.

3. Fractional Pareto Degradation Prediction Model

The PDF of the generalized Pareto distribution is shown in Equation (3):

where is a parameter. Small values of correspond to slow decay rate. is the scale parameter, which represents the dispersion of the random sequence; represents the location parameter.

3.1. Fractional Pareto Motion Model

The fGPm is defined by Riemann–Liouville integral, as shown in Equation (4):

where represents a generalized Pareto stochastic process with the location parameter , and the scale parameter , is the gamma function. The correlation and self-similarity depend on the parameter and the tail parameter .

- When , the kernel function changes very slowly with the variable , then the fGPm model has long-range dependence;

- When , the fGPm model exhibits short-range dependence;

- When , the fGPm model degenerates into the GPm model, which means that the equivalence between the fGPm model and the GPm model holds under specific parameter configurations.

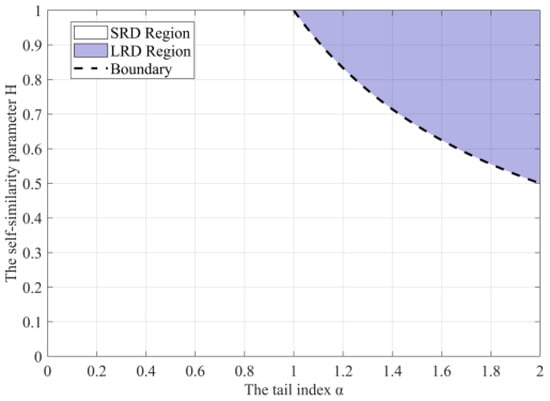

The larger the product of and is, the stronger the LRD of the stochastic sequence is, and the sequence shows a more complex changeable trend. When , the fGPm model does not have the LRD because the value of self-similarity is restricted to the interval . Figure 2 explains the relationship between and .

Figure 2.

Dependence of the fGPm model.

3.2. fGPm Predictive Model

According to the Itô formula, Black and Scholes introduced the fractional Brownian motion (fBm) model with the LRD characteristics [18], given as (5):

Substitution of Equation (4) into Equation (5) gives us the Itô process, driven by the fGPm model. Fluctuations of the random sequence in this process are not only affected by the drift coefficient and diffusion parameter but also depend on the fGPm model. The degenerate model is modeled, shown in Equation (6):

where is the initial value of the degenerate process sequence, usually set to 0, represents the nonlinear drift function, represents the drift coefficient, represents the diffusion coefficient, and represents the fractional Generalized Pareto motion model.

The fGPm of the incremental is expressed as shown in Equation (7):

where is the time increment.

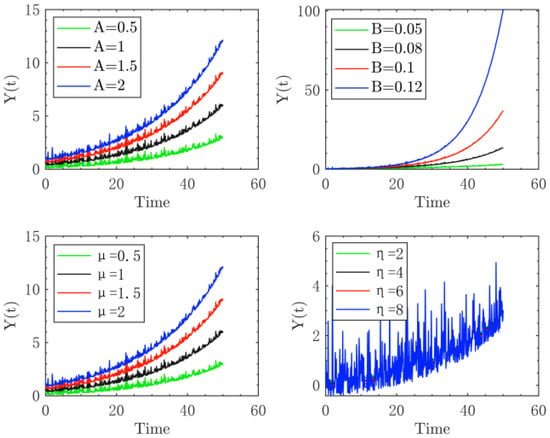

Set under different parameters, and are simulated as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Numerical simulation of the fGPm degradation model.

4. Reliability of the End Point of Remaining Life and Prediction Process

The ‘failure time’ is the bearing falling below a predetermined threshold and is considered to have failed. When the degradation process first exceeds the fault threshold, the point is called the ‘End of Life’ (EOL) of the bearing. The RUL is shown in Equation (8).

where is the time of the degradation process, is the process time of RUL, is the FPT, and is the set fault threshold.

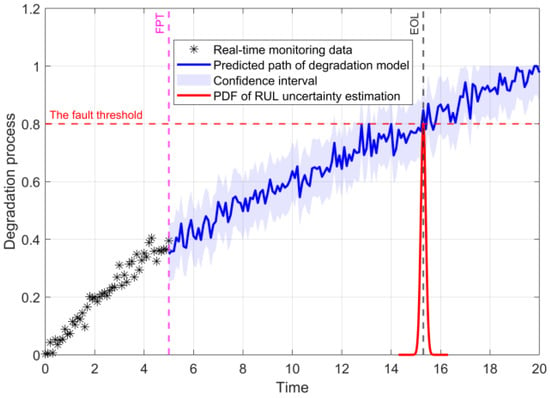

The fGPm prediction model is a non-stationary stochastic process. When the RUL prediction values are obtained directly from the model, the prediction values have an uncertainty. The degradation process of rolling bearings is characterized as a non-stationary. Therefore, Monte Carlo [19] can be used to simulate the degradation process. Through the statistical analysis of a large number of simulations, the probability distribution of RUL can be obtained, and the peak of probability density is considered as the RUL prediction value (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Typical prediction principle of the fGPm model based on Monte Carlo simulation.

5. Selection of Fault Characteristic Parameters

Next, it is required to evaluate how well the sensors correlate with the degradation pattern. Signals that do not properly correlate with a monotonic exponential trend should be removed. To that end, the three prognostic parameter choosing measures of monotonicity degradation, robustness and degradation trendiness are used to identify the meaningful characteristic parameters.

- (1)

- Monotonicity: Degradation process is a monotonically increasing process. The calculation is as follows:where is a pulse function, represents multi-domain features of multi-source sensors; represents the length of the bearing degradation sequence. A measure of Mon close to 1 indicates that the data from the sensor are monotonically increasing.

- (2)

- Robustness: Represents the anti-interference ability, calculated as follows:where , and the larger the Rob value, the stronger the robustness. is the characteristic value at moment, is the average value of the characteristic sequence.

- (3)

- Degradation trendiness: Represents the correlation between degenerative characteristic and time series, calculated as follows:where , and is the th value of the time series. A greater the value of the trendiness corresponds to a better fit.

The weak fault characteristic parameter CHI is obtained by assigning the corresponding weights to the evaluation indicators (9)–(11) as follows:

where .

6. Health Indicator Assessment

Then, the maximum likelihood method is applied to identify the parameter and . The sequence generated by the prediction model (7) has a high self-similarity with the future bearing degradation process sequence.

The Hurst exponent is independent of other degradation parameters. A generalized Hurst exponent method is adopted and calculated as follows:

where is the generalized Hurst exponent, which represents the scale dependence of the q order; ⟨∙⟩ represents the average value of a series, and is the time interval. When q = 1, the generalized Hurst exponent becomes the Hurst exponent.

In terms of Equation (7), we can obtain that

A degraded differential sequence is constructed, and . For the global mean , the mean of the degraded difference sequence is fitted, that is,

parameters α and can be estimated by the maximum likelihood estimation. The log-likelihood function for Equation (7) can be written as follows:

Then a MATLAB 10.0 function ‘fminserch’ was applied to solve the log-likelihood estimators of parameters α and .

7. Case Study

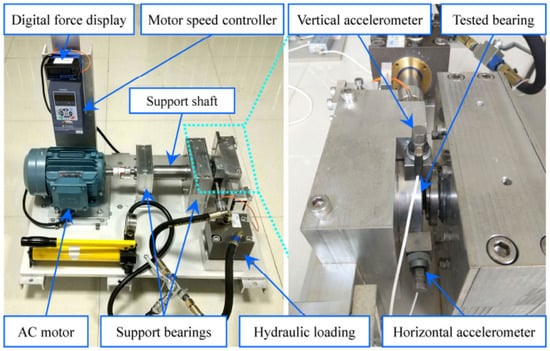

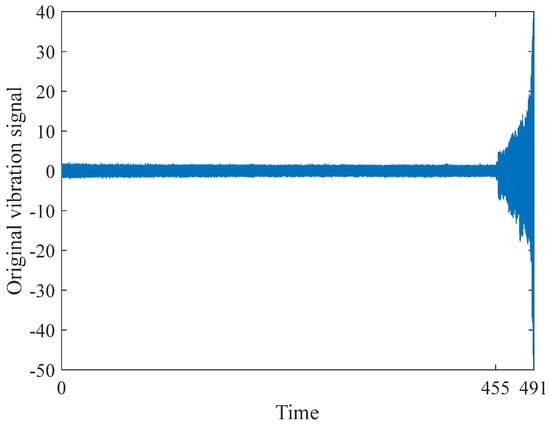

In order to demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach, consider the XJTU-SY bearing dataset [20] as the case study (see Figure 5). The experimental object is the roller bearing LDK UER204. The temporal dependence of the amplitude along the horizontal direction is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Test bench of the roller bearings.

Figure 6.

The original vibration sequence.

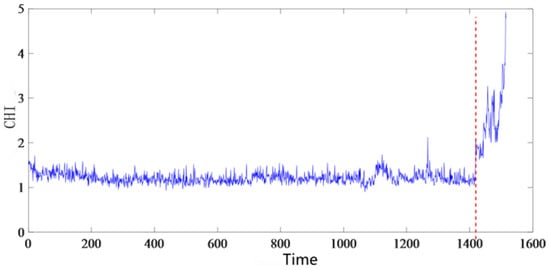

It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn. When the rolling bearing is operating normally, the degradation sequence exhibits the characteristics of a stationary random sequence. Once a weak fault occurs, the characteristics of the degradation sequence will change from a stationary random sequence to a non-stationary random sequence. Figure 7 shows that there is an obvious fluctuation at the 1418th point. After this point, the characteristic values of the degradation process suddenly change significantly and fluctuate violently. This stage is considered to be the slow failure stage of the rolling bearing; see Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Degradation characteristic series of bearings.

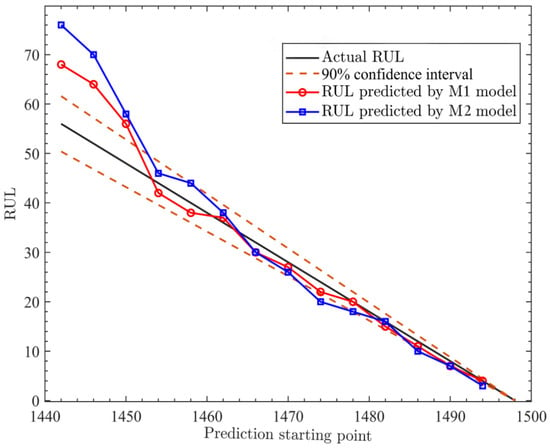

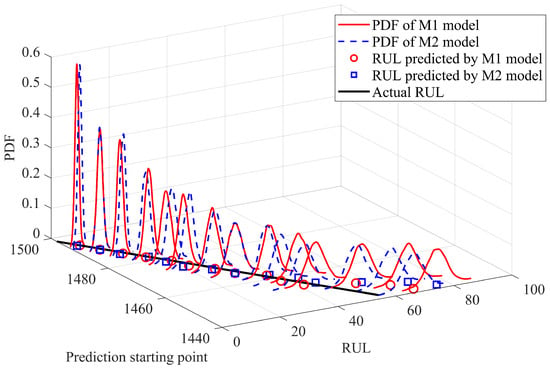

Let us refer to the exponential drift of the fGPm. Table 1 shows the maximum likelihood parameter identification of the fGPm degradation model at different prediction starting points. Figure 8 shows the RUL prediction results of the fGPm model (M1) with an adaptive drift function and the fGPm model (M2) without an adaptive drift function at multiple starting points. Figure 9 shows the uncertainty estimation results of M1 and M2 models at different prediction starting points. The analysis results indicate that an adaptive drift term can significantly improve the accuracy of prediction results.

Table 1.

Parameter estimating for different starting points.

Figure 8.

Predictions with and without drift parameters.

Figure 9.

Comparison of PDF with and without drift parameters.

The obtained results are compared with other models: the fLSm degradation model with adaptive drift ability (M3), the fBm degradation model (M4), the Brownian motion (Bm) degradation model (M5), and the LSTM (M6). Table 2 shows the prediction accuracy, result score, health assessment, and reliability. M1 not only has the lowest values on RMSE (5.7268) and MAE (3.8856) and the smallest error between its predicted and actual values but also obtained the highest scores on SOR (0.91935) and HD (0.99574).

Table 2.

Predicting error compared with other models.

8. Conclusions

This article does not discuss the setting of fault diagnosis parameters, fault thresholds, and parameter maximum likelihood identification for the degradation process.

- (1)

- The degradation process of bearings has a non-stationary stochastic process with long-range dependence and self-similarity.

- (2)

- The accuracy of RUL in this article is better than other methods.

- (3)

- Because the degradation process of all equipment and components is a gradual non-stationary process, this method can be extended to other fields.

Future research directions will focus on multimodal factors because the practice operating conditions are random multimodal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S. and S.C.; methodology, P.C.; software, H.Z. and Q.Z.; validation, S.C., P.C. and H.Z.; formal analysis, S.C.; resources, W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, P.C.; supervision, W.S.; project administration, W.S.; funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the innovation team projects of Minnan University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 24XTD158), Department of Science and Technology in Fujian Province (Grant No. 2023H6026) and Quanzhou Science and Technology Program Project (Grant No. 2022N041).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACFs | Autocorrelation Functions |

| Fractional Pareto Motion | |

| H | Hurst Exponent |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| LRD | Long-Range Dependence |

| fGPm | Fractional Generalized Pareto Motion |

| GPm | Generalized Pareto Motion |

| fBm | Fractional Brownian Motion |

| VMD | Variational Mode Decomposition |

| Probability Density Function | |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| HI | Health Indicator |

| EOL | End of Life |

| FPT | Forecasting Starting Point |

| CHI | Weak Fault Characteristic Parameter |

| BM | Brownian Motion |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| HD | Health Degree |

| SOR | Scoring of Results |

| PICP | Prediction Interval Coverage Probability |

| MPIW | Mean Prediction Interval Width |

References

- Pang, Z.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Du, D.; Pei, H. A Bayesian Inference for Remaining Useful Life Estimation by Fusing Accelerated Degradation Data and Condition Monitoring Data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 208, 107341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soualhi, A.; Medjaher, K.; Celrc, G.; Razik, H. Prediction of bearing failures by the analysis of the time series. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 139, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobon-Mejia, D.A.; Medjaher, K.; Zerhouni, N.; Tripot, G. A Data-Driven Failure Prognostics Method Based on Mixture of Gaussians Hidden Markov Models. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2012, 61, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.; Laha, S.; Kumaraswamidhas, L. Assessment of rolling element bearing degradation based on Dynamic Time Warping, kernel ridge regression and support vector regression. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 208, 109389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugalenthi, K.; Park, H.; Raghavan, N. Prognosis of power MOSFET resistance degradation trend using artificial neural network approach. Microelectron. Reliab. 2019, 100–101, 113467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Tao, T.; Zio, E.; Wang, W. A Novel Hybrid Method of Parameters Tuning in Support Vector Regression for Reliability Prediction: Particle Swarm Optimization Combined with Analytical Selection. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2016, 65, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamad, A.K.; Saon, S.; Hiyama, T. Predicting remaining useful life of rotating machinery based artificial neural network. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 60, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Wang, P.; Song, L. A novel prediction network for remaining useful life of rotating machinery. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 4009–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kong, X.; Deng, L.; Peng, H.; Zhang, J. Prediction and Uncertainty Quantification of the Fatigue Life of Corroded Cable Steel Wires Using a Bayesian Physics-Informed Neural Network. J. Bridg. Eng. 2025, 30, 4025018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbola, S.; Coors, V. One dimensional convolutional neural network architectures for wind prediction. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 195, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, N.; Peng, W. Estimation of Bearing Remaining Useful Life Based on Multiscale Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 3208–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.Q.; Vu, T.B.; Shafiabady, N.; Nguyen, P.T. Loss factor analysis in real-time structural health monitoring using a convolutional neural network. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2024, 95, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Mukhiddinov, M. Data Anomaly Detection for Structural Health Monitoring Based on a Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Wei, Y.; Peng, J.; Zheng, X.; Lu, K.; Li, Z. Spatio-temporal graph neural network based on time series periodic feature fusion for traffic flow prediction. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ren, M.; Xu, T.; Lu, C.; Zhao, Z. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Rolling Bearings Based on Multi-scale Permutation Entropy and ISSA-LSTM. Entropy 2023, 25, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Cattani, C.; Chi, C.-H. Fractional Brownian motion: Difference iterative forecasting models. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 123, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Li, M.; Liang, J.-K. Prediction of Bearing Fault Using Fractional Brownian Motion and Minimum Entropy Deconvolution. Entropy 2016, 18, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-H.; Kang, X.; Wang, C.; Ma, T.-B.; He, X.; Yang, K. A Hybrid Approach for Predicting the Remaining Useful Life of Bearings Based on the RReliefF Algorithm and Extreme Learning Machine. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 140, 1405–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhu, H.; Hu, K.; Wu, J.; Shao, X.; Wang, Y. Reliability prediction of machinery with multiple degradation characteristics using double-Wiener process and Monte Carlo algorithm. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 134, 106333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lei, Y.; Li, N.; Li, N. A Hybrid Prognostics Approach for Estimating Remaining Useful Life of Rolling Element Bearings. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2020, 69, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.