Abstract

Significant progress in autonomous vehicle (AV) development has been made over the years through advancements in artificial intelligence, sensor technology, and data processing; however, many challenges remain, particularly regarding road safety and the complexity of adapting these vehicles to certain traffic situations. As a result, many European countries are funding research projects and setting targets and strategic plans for autonomous mobility, while scientific research proposes establishing standards and design guidelines for adapting road infrastructure to new transportation trends. This review paper examines physical road infrastructure in the era of AVs and identifies potential modifications, considering the development of AVs during both the early and later stages of their introduction into mixed traffic flow. Accordingly, necessary road infrastructure adaptations and the main design parameters affecting road geometric design for AV operation are presented. The design parameters considered include stopping sight distance, vertical curve radii, straight sections, lanes, and others. Furthermore, potential changes in existing physical infrastructure are illustrated using the example of a deceleration lane. Whether it is new infrastructure or modifications to existing infrastructure, both are analyzed in terms of the proportion of AVs in the traffic flow.

1. Introduction

Road safety is becoming a growing issue in the world. In order to increase safety in the global transportation network, the causes and prevention methods of road accidents and reducing the number of fatalities in these accidents are being investigated. To reduce the number of road accidents, solutions such as improving drivers’ skills or using technologies with less human involvement are being developed [1,2,3].

In the European Union (EU), recent statistics show that the number of fatalities in road accidents has decreased by 15% compared to the average number of fatalities between 2017 and 2019, and by 13% compared to the number of fatalities in 2019 [4]. According to the European Commission (EC), around 19,800 people died in road accidents in Europe in 2024, a 3% decrease compared to 2023. The EU has set a target to halve the number of road deaths by 2030, but the current statistical results are not satisfactory. This effort is part of the “Vision Zero” strategy, which aims to eliminate all road deaths and serious injuries by 2050 while increasing safe mobility for all road users [5].

Furthermore, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), road accidents cause the deaths of 1.19 million people worldwide every year [6]. The WHO emphasizes the need to create a safe transportation system for all road users that ensures road accidents do not result in fatalities; the system should be designed to eliminate human error. According to [7], 80% of road accidents are caused by human error. Risk factors resulting from human error include speeding, driving under the influence of alcohol, distracted driving, not wearing a helmet, not wearing a seatbelt, etc. [6]. It should also be noted that excessive speed is the most common cause of road traffic accidents and can lead to serious collisions [8].

According to the WHO, other risk factors are unsafe vehicles and poorly designed road infrastructure [6]. A safe vehicle should at least meet the following minimum requirements: it should comply with frontal and side impact regulations, have electronic stability control (to prevent oversteer), and be equipped with airbags and seatbelts [6]. Safe road design primarily refers to properly selected road design elements, appropriate lane markings, suitable facilities for pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists, as well as footpaths and cycle paths, safe crossings, and the use of traffic calming measures [6]. Appropriate road design ensures safety, reduces road accidents, increases visibility, and improves traffic flow [9]. In addition, a current problem in the transportation system is the rapid increase in the number of cars, which puts pressure on the transportation infrastructure and leads to traffic jams. This results in economic losses, delays, driver discomfort, and traffic accidents [10].

Researchers, developers, and manufacturers see autonomous driving (AD) as the future of transportation. AD has become a popular topic that is increasingly becoming a reality as technology advances. Significant progress in AV development has been achieved over the years through advancements in artificial intelligence, sensor technology, and data processing [11]. However, it still poses challenges, especially regarding safety and the complexity of adapting to certain traffic situations [12,13]. As a result, many European countries are funding research projects and setting targets and strategic plans for autonomous mobility [14], while scientific research proposes establishing standards and design guidelines for adapting road infrastructure to new transportation trends [15].

This review paper examines physical road infrastructure in the era of AVs and identifies potential modifications, considering the development of AVs during both the early and later stages of their introduction into mixed traffic flow. The main objective is to review the current state of research on the development of AVs and their impact on traffic flow and capacity in mixed traffic scenarios, with the aim of identifying necessary road infrastructure adaptations and the main design parameters affecting road geometry for AV operation. Section 2 briefly outlines the main advantages of introducing AVs into the transport system, which in turn raises the question of whether the physical transport infrastructure needs to be adapted for the traffic of such vehicles in the near future. Section 3 presents the methodology and the research in question. Section 4 presents current milestones in AV development. Section 5 discusses the impact of AVs on traffic flow and capacity in mixed traffic scenarios. Section 6 analyzes the necessary road infrastructure adaptations and the main design parameters affecting road geometry for AV operation. Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing the current state of research and previous studies on this topic and highlights the study’s limitations and directions for future research.

2. Background

Considering the potential benefits that AVs bring to the transportation system, such as increased safety, increased capacity, enhanced mobility for immobile, underage, and elderly people, economic advantages, and reduced negative environmental impact, there is significant discussion in scientific circles about the possibilities of changing road infrastructure in the future (Figure 1) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the benefits that AVs bring to the transportation system.

From this perspective, it can be said that autonomous driving (AD) eliminates the human factor, since AVs make decisions based on data from in-vehicle sensors and decision-making algorithms. However, a lack of reliable sensor data or incorrect algorithm calculations can result in undesirable behavior and endanger passenger safety [7]. Nevertheless, most sources state that AVs will improve road safety by reducing human error and, consequently, decreasing road accident rates [25]. AVs are expected to have lower accident rates, shorter reaction times, and less variability in driver behavior compared to human drivers [26,27]. AVs are also expected to increase capacity, improve traffic flow, ease congestion, and make the transportation network more efficient [11].

Mobility will expand through ride-hailing, ride-sharing, and self-driving taxis [28]. Companies such as Waymo, Tesla, GM Cruise, Aptiv, Uber, and Lyft are leading AV development. Waymo offers ride-hailing services in selected areas, Tesla’s Autopilot system provides advanced driver assistance features, General Motors focuses on ride-sharing services, Aptiv uses advanced driver assistance systems and AV technology, and Uber and Lyft, as ride-hailing companies, are investing in AV technology to reduce labor costs and increase efficiency [28]. Some main benefits of ride-hailing services are the elimination of driver-related costs, nonstop operation, increased fleet efficiency, and lower ride prices [11].

Economic benefits of AVs include reduced operational expenses, increased productivity, lower accident-related costs, and decreased logistics costs [29]. The study [30] also predicts that the first autonomous vehicles will be trucks. Autonomous trucks would benefit the economy by reducing labor and fuel costs, and deliveries and pick-ups would be faster than they are now. These vehicles could drive in road trains (so-called “platooning”), where vehicles drive one after another at a small distance. Additionally, there would be no driving time restrictions as there are for human drivers today, and driving would be safer. As a result, supply chains would be managed more efficiently, and deliveries would be faster [31].

In terms of environmental sustainability, electric AVs offer a cleaner, quieter, and more energy-efficient transportation system. AVs will enhance fuel efficiency and reduce emissions due to their control and optimization capabilities. They also have the potential to reduce carbon footprints (the assessment of emissions released into the atmosphere) and ease traffic congestion [32]. The use of AVs will result in less fuel consumption through improved lane management, better acceleration and deceleration of vehicles, and the ability to maintain optimal speed [11]. There is also significant potential to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. California has set a target to achieve carbon neutrality (balancing carbon dioxide emissions) by 2045 [11], and China by 2060 [33], while the EU aims to achieve climate neutrality (balancing all GHGs, including methane and nitrous oxide) by 2050 [34]. As part of its sustainability goals, the EU has established the current R&I Framework Programme Horizon Europe for 2021–2027, which is intended to accelerate the achievement of climate and digital objectives. In July 2025, the European Commission proposed the Horizon Europe Programme 2028–2034. This program is expected to launch “moonshot” science-driven projects, including Automated Transport and Mobility, which focuses on enabling safe, inclusive, emission-reducing automated transport and mobility in Europe [35].

However, before introducing AVs, many challenges must be addressed, such as risks to passengers and other road users from insufficient sensor data and technological errors, the operation of algorithms, and antivirus systems that must protect against cyberattacks. Ensuring safety and security, resolving ethical dilemmas and impacts on the labor market, gaining public trust, and addressing legal issues must be priorities in further development. Addressing concerns about the safety and reliability of AVs by transparently presenting existing problems and possible solutions is important for public acceptance of these vehicles [11]. The actual impact of the new technologies mentioned above depends on their development and the speed of introduction of AVs into the transportation network (percentage of AVs in the traffic flow). It is expected that the first AVs will appear on roads between 2030 and 2050, initially on highways and later in urban areas [36]. The integration of AVs into urban areas is challenging due to numerous unpredictable variables, such as pedestrian and cyclist movements and unsignalized intersections [37]. In the early stages, mixed traffic is expected. Therefore, road safety in a mixed traffic environment of AVs and CVs has yet to be confirmed [12,13]. Researchers are already studying road accidents involving CVs and those caused by AV failures to better understand how road infrastructure should be designed to accommodate both CVs and AVs [9]. Furthermore, the advent of AD could impact physical road infrastructure through additional costs, such as introducing dedicated lanes or changing road geometry requirements [38]. As the number of AVs on the roads increases, it is necessary to review, update, and develop guidelines and policies for road infrastructure design.

3. Methodology

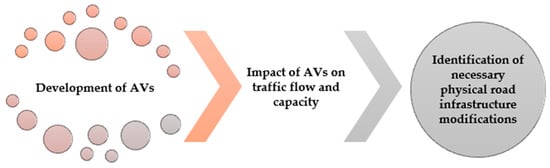

This state-of-the-art review examines the existing literature on the development of AVs and their impact on traffic flow and capacity in mixed traffic scenarios, aiming to identify necessary road infrastructure adaptations and the main design parameters affecting road geometry for AV operation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The process of analyzing existing literature on potential physical road infrastructure modifications for Avs.

Relevant information was gathered by searching various databases, including Google Scholar, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Web of Science. Additional papers were identified by cross-referencing selected studies and other sources. The keywords used in the search were autonomous vehicles, connected and automated vehicles, traffic flow, mixed traffic flow, road design, road safety, and physical infrastructure. Publications reviewed include scientific journals, conference proceedings, technical reports, and regulations. Only English-language publications published between 2017 and 2025 were considered, except for technical reports and regulations.

The literature review shows that most current works focus on digital infrastructure or the maintenance of existing roads in the context of digitization, while only a few address physical road infrastructure. A major part of this paper focuses on physical infrastructure, specifically the influence of AVs on its adaptation from a design perspective.

In summary, the key contribution of this study is a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of AVs on physical infrastructure, with a focus on mixed traffic scenarios.

4. General Information About AVs and the Development of AD Technology

An AV is a self-driving car, a vehicle that can recognize its environment and drive without human intervention, meaning a human passenger does not need to take control of the vehicle at any time or even be present in the vehicle [39].

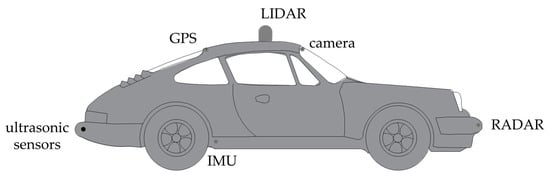

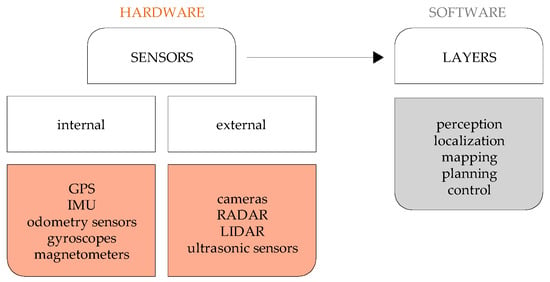

An AV makes decisions about its environment based on data obtained from sensors in the vehicle (hardware) and decision-making algorithms (software). Using various sensors on and in the vehicle, AVs register, collect, analyze, and share data about their environment (e.g., traffic system, pedestrians, time of day, weather) [39]. Figure 3 shows sensors on and inside the vehicle, while Figure 4 schematically represents how AVs collect and process environmental data. The sensors can be internal (proprioceptive sensors) or external (exteroceptive sensors). Internal sensors include GPS (Global Positioning System), IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit), odometry sensors, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. External sensors include cameras, RADAR (Radio Detection and Ranging), LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), and ultrasonic sensors [40].

Figure 3.

Various sensors on and inside the vehicle.

Figure 4.

A schematic representation of how hardware and software in AVs collect and process data.

Their characteristics are as follows: GPS—enables localization and navigation; IMU—provides data on vehicle acceleration, orientation, and angular velocity; odometry sensor—determines position changes over time; gyroscope—measures or maintains orientation and speed; magnetometer—for navigation and tracking; camera—records visual information about lane markings, signs, traffic lights, pedestrians, other vehicles, etc.; RADAR detects objects and their speed; LIDAR—creates 3D maps of the environment and measures the distance to nearby objects; ultrasonic sensors—for close-range detection when parking or maneuvering [7,41].

The above is part of the hardware of the AV. The software uses the data collected by the sensors and consists of five layers: perception, localization, mapping, planning, and control [40]. Once the raw data has been collected, it is processed to make it usable by artificial intelligence algorithms. The perception layer interprets the pre-processed sensor data to understand the environment (object and lane recognition, semantic segmentation, localization). The vehicle then creates a model of the environment (object tracking, map integration, sign recognition). Based on the model of the environment, decisions are made in real time (path and behavior planning, emergency maneuvers). The control layer then converts the decisions into commands (steering, acceleration, and braking) for the vehicle’s actuators, which follow the planned path and react to surrounding objects [28].

The development of AVs began a hundred years ago when the first automated vehicle was tested in the USA. The history of the development [12] of AD is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

History of AD by years.

In 2014, the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) [42] (SAE J3016, Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles, SAE 709 International, 2021) classified autonomous vehicles according to levels from L0 to L5, where L0 is a conventional vehicle without automation and L5 is a fully autonomous vehicle (SAE J3016 Standard) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of automation.

Current automation is progressing from L2 to L3, moving from advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) to automated driving systems (ADS) [43]. L2 functions (partial automation) are integrated into vehicles from Audi, Tesla, Lexus, Porsche, BMW, and Volvo. L3 functions include Audi’s traffic jam pilot system, which enables steering, braking, and acceleration [25]. L3 vehicles can intervene to prevent an accident, but the system may require human intervention [44]. In general, L3 to L5 vehicles are considered autonomous vehicles, where the vehicle has full control over its decisions [45].

5. AVs in Mixed Traffic Flow

As mentioned in the introduction, the first AVs will operate in mixed traffic. Their impact on traffic flow is briefly described below.

5.1. Technologies That Affect Traffic Flow

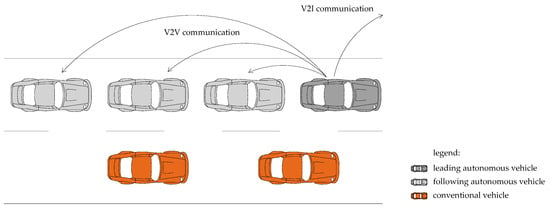

AD has significant potential to improve traffic flow, increase road capacity (the maximum sustainable flow rates a roadway can handle), and alleviate congestion by reducing the distance between vehicles and optimizing their speed through mutual communication (i.e., vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) connectivity) [46]. This communication enables vehicles to coordinate their speed and acceleration, resulting in a more stable and smoother traffic flow and ultimately better road utilization. Platooning refers to a group of vehicles that move and communicate with each other in a coordinated manner [47].

The leading vehicle transmits information about its speed, acceleration, and position to the following vehicle. By using Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control (CACC), the following vehicle can maintain a short distance and still avoid collisions (Figure 5) [48]. CACC is an advanced adaptive cruise control (ACC) technology that uses V2V and V2I communication, allowing closer following distances and improved traffic flow [49]. ACC and CACC technologies are widely analyzed by researchers through microscopic simulations and models based on real-world data [50].

Figure 5.

Leading vehicle and following vehicles in a platoon.

Another cooperative technology is Advanced Merging (A.M.), which enables vehicles to manage traffic flow at congestion points (e.g., when merging or leaving a lane). Using V2V and V2I communication, the vehicle signals its intention to merge into the main traffic and, in coordination with other vehicles, attempts to merge when it detects an acceptable gap. This coordination between the main traffic and the merging vehicle reduces interference during merging. According to [49], CACC and A.M. vehicle applications will have a major impact on capacity. Adebisi et al. [49] show that the maximum platoon size should be 10 vehicles in row per lane. Due to lane changes, the platoon size should not be too large, as this could make merging impossible and communication between the leading and following vehicles unreliable. On the other hand, a short platoon size reduces the effectiveness of CACC implementation. The use of these technologies could also reduce the risk of accidents and increase road safety [47].

Researchers [21] suggest that in mixed traffic flow, cooperation between vehicles can be achieved not only in platoons but also through uniform distribution in the lane. According to them, previous research focused more on variations in the percentage of AVs in the traffic flow and did not consider vehicle formation. Moreover, if there is a low deployment of AVs in the initial phase, CVs may interfere with vehicles in the platoon and make communication between AVs difficult [51].

5.2. Safety

Mixed traffic flow refers to the interaction between AVs and CVs when the percentage of AVs in the total traffic flow is less than 100%. In mixed traffic flow, different traffic operation principles (due to the differing driving behaviors of AVs and CVs) create potential safety risks. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the impact of AVs on road safety [18]. One study assessing the impact on safety by predicting possible road traffic accidents was conducted on a stretch of highway in Dubai [52]. The results show a reduction in accident frequency when the proportion of AVs in the traffic flow is between 40% and 100%, and a complete elimination of traffic accidents when the proportion of AVs reaches 100%.

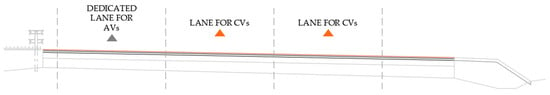

The safety risk in mixed traffic flow can be minimized by using dedicated lanes. In addition to reducing safety risk, dedicated lanes can help other road users more easily adopt AVs in the near future. These are usually the innermost lanes of multi-lane roads (Figure 6) [50].

Figure 6.

Example of a dedicated lane for AVs.

A real-world example is a dedicated lane constructed on the Beijing–Xiongan Expressway (China’s demonstration project for intelligent freeway systems) [50]. The impact of dedicated and isolated lanes on traffic flow with a consistent proportion of AVs was examined [50]. Differences in average speeds under four lane control policies were compared, and it was concluded that at higher proportions of AVs, higher average speeds are achievable, reducing traffic congestion. This is also confirmed by research [53] which evaluated the impact of using dedicated lanes for AVs on traffic flow and found that traffic capacity increases significantly when the proportion of AVs exceeds 30%. The study [54] showed that capacity increases when AVs are physically separated from CVs. However, using a dedicated lane for AVs can lead to inefficient roadway use and traffic congestion, since CVs are prohibited from entering dedicated lanes, especially when the percentage of AVs in traffic flow is low [18]. Additionally, constructing a new lane can be expensive [55].

5.3. Capacity

Many researchers are investigating the influence of the share of AVs in traffic flow on road capacity [46]. According to [40], capacity increased by 40% when the percentage of AVs in the traffic flow reached 100%. Some researchers [41] have shown that capacity increases only when the rate of AVs in the traffic flow exceeds 70%. Others [28] showed a greater increase in capacity when the percentage of AVs in mixed traffic flow was 20–40% than when it was less than 20%. However, the study [56] showed an increase in capacity with the gradual integration of AVs into the traffic flow, as did [57], confirming that as the percentage of AVs in the traffic flow increases, so does capacity. The increase in capacity according to various studies [28,40,41] is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Increase in capacity in relation to the share of AVs in the traffic flow.

Although the researchers expect an improvement in capacity, the study [25] indicates that these results are primarily based on microscopic traffic simulations, and real-world field tests have not yet been conducted.

There are also potential challenges associated with the deployment of AVs that could negatively impact traffic flow. For example, uneven deployment across regions could lead to congestion and delays as AVs communicate with CVs [58] In addition, integrating AVs into existing transportation infrastructure may require significant changes to road design and traffic management systems, potentially causing disruption and delays [59]. Furthermore, the deployment of AVs may lead to changes in passenger behavior, such as a shift to individual vehicle ownership and use, which could increase overall demand on roads and potentially negate some of the benefits of AVs [58].

Congestion pricing and tolls are important tools for managing demand and encouraging more socially and environmentally optimal travel choices [60]. The application of congestion pricing in AV scenarios remains relatively unexplored. Reduced driver workload, lower travel costs, and improved transport accessibility are likely to increase car use, leading to more congested traffic conditions well before AVs can address many capacity issues. Empty AVs traveling between trips may worsen this effect, and actual increases will vary by region, depending on transport modes, parking costs, and general travel patterns. The adoption of AVs and the emergence of mixed-flow scenarios present new theoretical and practical challenges for congestion pricing [60].

5.4. Testing and Modelling

Numerous tests are required to understand the impact of AVs on traffic flow. Testing in real-world scenarios requires securing a test site and the necessary equipment, as well as dealing with the variability of atmospheric conditions. Most importantly, such experiments are expensive and time-consuming [61]. Given this, simulators are a valuable tool for researching new technologies, as they offer significant savings in time, cost, and labor. According to [62], from 2022 to 2023, more than 50% of published methods in scientific papers were implemented and tested in simulators. Furthermore, leading companies (e.g., Waymo, Pony.ai, DiDi) [63,64,65] emphasize the importance of developing and using simulators.

Traffic flow simulators are used for road network adaptation, microscopic simulation, and visualization. Commonly used simulators include PTV Vissim, SUMO, Transmodeler, and AIMSUN [66]. Simulations help determine the conditions and measures under which AVs can be safely integrated into road traffic and show how these vehicles behave in their operating environment [25]. Moreover, simulations can help evaluate the characteristics of AVs and their impact on traffic flow, thereby improving traffic flow, increasing capacity, enhancing safety, and reducing environmental impact, among other benefits [47]. Various factors need to be considered in the simulation (e.g., the percentage of AVs in the traffic flow at different levels of autonomy, weather conditions, traffic density, road infrastructure condition, etc.) [25].

Traffic flow modeling is based on microscopic, macroscopic, or mesoscopic models. The microscopic model describes the behavior of a single vehicle, including its speed, position, and headway. The macroscopic model describes average traffic density and speed, while the mesoscopic model is a hybrid of the two [67]. These models are based on the principles of fluid dynamics. However, to better describe the behavior of CVs and AVs, researchers [67] proposed a spring-mass model, as vehicle acceleration and deceleration resemble a mechanical system. They concluded that the proposed spring-mass model provides more accurate and realistic traffic behavior.

The Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) provides procedures for calculating the capacity and quality of service of various highway facilities. The HCM [68] is used in practice for corridor planning assessments and serves as a credible source and benchmark for capacity assessment and as a guide for traffic analysis. Therefore, a study was conducted [49] to assess the impact of AVs on capacity according to HCM procedures. The study was performed in PTV Vissim [69], where the microsimulation model developed by Wiedemann (Wiedemann ’99 model, suitable for highway networks) [70] was calibrated and adjusted. The researchers developed capacity adjustment factors (CAFs) for AVs on different highway sections, considering various levels of traffic demand and different percentages of AVs in the traffic flow. They also created tables of CAFs and corresponding statistical capacity prediction models [49]. Consequently, in the seventh edition of the HCM, capacity adjustment factors were updated to evaluate the impact of AVs on highways, traffic-controlled intersections, and roundabouts.

6. Necessary Adaptation of Physical Infrastructure for AVs

The adaptation of road infrastructure will primarily depend on the development of AVs [71]. Three phases are foreseen [72] for the introduction of AVs into the road network, and the adaptation of road infrastructure will depend on the level of automation and the proportion of these vehicles in the traffic flow (AVs share). In the first phase of adaptation, which is the present, with an AVs share of less than 20%, roads and associated facilities will be intensively maintained. In the second phase, in the 2030s, with an AVs share of 20% to 50%, separate corridors will be established for AVs. Finally, in the third phase, starting in the 2050s, with an AVs share higher than 50%, the road infrastructure will be simplified or adapted for the traffic of these vehicles [71,72].

In the first phase, appropriate and well-maintained traffic signs and lane markings are essential for the safe operation of AVs and their sensors. Currently, there are issues such as vehicle-camera recognition of signs in rainy weather or at night [25], or vehicles failing to recognize lane markings, which prevents the system from positioning the vehicle in the center of the lane. Researchers [73,74] found that markings are less visible in sunlight, especially when the surface is wet. The perception of AVs in adverse weather conditions is reduced because detection algorithms focus on a single weather condition, such as fog, snow, or rain [75]. Different sensors operate in different ways and to varying degrees. For example, LiDAR cannot detect obstacles in foggy weather, while cameras cannot distinguish well enough at night. A comprehensive approach to maintenance should be agreed upon at the international level. This paper will further discuss the design aspects and changes to road infrastructure.

Considering the development of AD, it is expected that the first AVs will be operating on roads between 2030 and 2050, initially on highways and later in urban areas [36,76]. The integration of AVs into urban areas is challenging due to numerous unpredictable variables, such as pedestrian and cyclist movements and unsignalized intersections. Pedestrians often cross roads where zebra crossings are not marked or follow their own paths. At crossings without traffic lights, they communicate their intentions by making eye contact with drivers [77]. The development of new technologies raises the question of how AVs will affect pedestrian behavior and interaction in mixed traffic [78]. Integrating AVs into urban centers requires technological adaptation and infrastructural changes to accommodate both AVs and CVs without compromising pedestrian safety. The focus should be on creating environments where AVs and human road users, including pedestrians and cyclists, can safely coexist. At roundabouts, AVs must navigate complex, continuous traffic flows without traffic lights, making real-time decision-making and advanced perception crucial for pedestrian safety. While roundabouts can reduce vehicle speeds and potentially increase safety, AV integration introduces new challenges and opportunities for improving pedestrian–vehicle interactions. The integration of autonomous vehicles requires further research into how these vehicles interpret and respond to pedestrian behavior at intersections [79].

Therefore, the parameters of non-urban environments are described below. Research [73] focused on determining the characteristics of AVs, showing that large longitudinal gradients and sharp horizontal curves can cause system errors, and that driving such vehicles on highways is safest given their geometric characteristics. The authors of [80] state that AD systems face challenges in positioning vehicles in horizontal curves, especially as the curves become sharper. Their study refers to L2 level vehicles, where the driver may or may not use these systems. The study [9] showed that geometric features such as smaller road curvature and greater road width can cause AVs to fail. They also concluded that current road design is suitable for AVs on roads with smoother horizontal curves and for high speeds (i.e., highways), and emphasized that AVs should also be designed to operate effectively on lower-level roads. With the increasing number of AVs on the roads, it is necessary to review, update, and develop guidelines and policies for the design of road infrastructure.

6.1. Design of New Road Infrastructure

When designing road infrastructure, the design vehicle must be identified. In design practice, the term “design vehicle” refers to the vehicle that is least favorable in terms of swept path analysis when planning roads [81]. AVs are equipped with various types of sensors and Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS), while their dimensions do not differ from those of CVs [30]. Furthermore, researchers [82,83] have shown that, in the future, the parameters for road infrastructure design that are directly related to driver characteristics (e.g., reaction time, driver’s eye height, etc.) will change the most.

In a previous study [72] conducted by the authors of this paper, the influence of AVs on the selection of highway design elements was analyzed, considering design speeds from 80 km/h to 120 km/h. The design parameters for AVs proposed in the literature [67,82,83] were compared with the design parameters for CVs defined in the Croatian regulations [84].

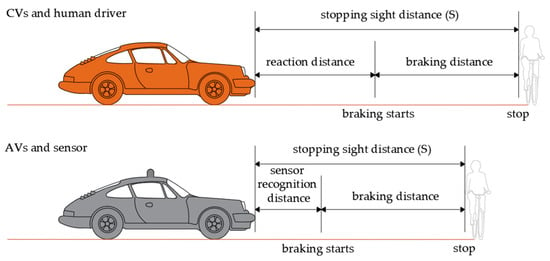

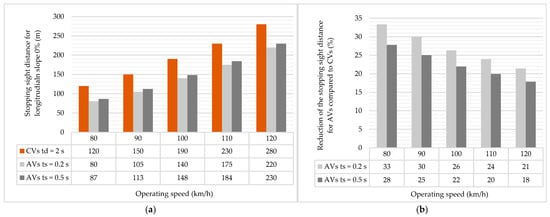

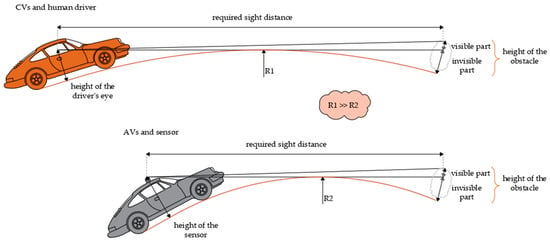

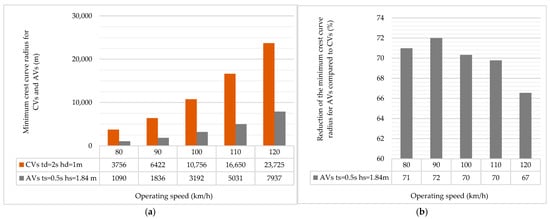

Stopping sight distance (S) is the sum of the distance traveled during reaction time and the distance traveled during braking [84]. The length of reaction time depends on the driver’s attention and response, while the length of braking depends on the mechanical characteristics of the vehicle. Reaction time is a parameter that affects stopping sight distance. Since AVs are equipped with sensors whose time to detect obstacles (ts) on the road (0.2 s–0.5 s) [67,82,83] is significantly shorter than the driver’s reaction time (td) (1.5 s–2.5 s) [82,83], it has been concluded that stopping sight distances on highways could be reduced by 21% to 33%, depending on the operating speed (Vo) (Figure 7 and Figure 8) [72].

Figure 7.

A schematic representation of stopping sight distance for CVs and AVs.

Figure 8.

Stopping sight distance: (a) for CVs (driver reaction time of 2 s) and AVs (sensor recognition times of 0.2 s and 0.5 s); (b) reduction for AVs with sensor recognition times of 0.2 s and 0.5 compared to CVs.

A minimal crest curve radius depends on the required sight distance between the vehicle (driver’s eye) and the invisible part of the obstacle on the other side of the curve [84]. The height of the driver’s eye is set at 1.0 m above the ground, and the height of the invisible part of the obstacle depends on the operating speed (0.25 m–0.20 m). The minimum sag curve radius must be at least half the radius of the adjacent crest curve. Due to the shorter stopping sight distance and the fact that the sensors on the roof of AVs are at a height (hs) of approximately 1.84 m above the ground (e.g., the height of the Waymo vehicle is 1.56 m and the height of the sensor is 0.28 m) [83], and the driver’s eye height (hd) in CVs is 1.0 m [84], the minimum radii of crest curves would decrease by 67% to 72%, also depending on the operating speed (Vo) (Figure 9 and Figure 10) [72].

Figure 9.

A schematic representation of the minimum crest curve radius for CVs and AVs.

Figure 10.

Crest curve radii: (a) for CVs (the driver’s eye is 1.0 m above the ground) and AVs (the sensors are 1.84 m above the ground); (b) reduction for AVs compared to CVs.

Horizontal alignment consists of straight segments and horizontal curves [84]. Since AVs are not operated by a human driver, it has been found that the traffic of these vehicles will also influence the conditions for the use of straight sections of horizontal geometry; factors such as driver fatigue and glare from the lights of vehicles coming from the opposite direction in such sections will be eliminated [72]. The minimum radius of horizontal curvature is determined by the conditions of transverse stability of the vehicle in the curve, i.e., the transverse slope of the road. Another factor is the friction between the wheels and the pavement, which opposes the centrifugal force component. In other words, the determination of the minimum radius of horizontal curves is influenced not by the human factor, but by the characteristics of the environment and the mechanical characteristics of the vehicle. If these characteristics are assumed to be the same for autonomous vehicles and conventional vehicles, the required minimum horizontal curve radius will remain the same [83].

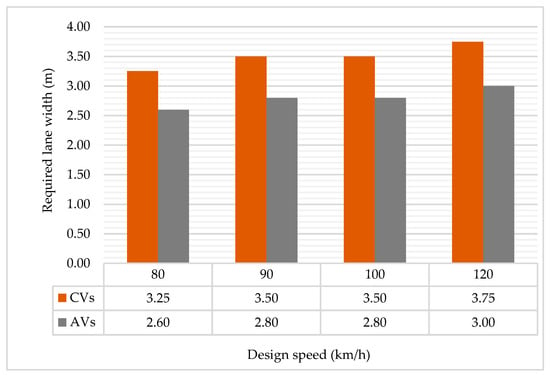

Lane width depends on design speed and, according to [84], ranges from 2.75 m to 3.75 m. Changes to the road cross-section are planned due to a possible reduction in lane width for AVs to up to 2.4 m [83]. The authors of [82] state that lanes not used by buses and heavy vehicles could be between 2.4 m and 2.7 m wide. Another study [72] has shown that lane width could be reduced by 0.65 to 0.75 m by using the Lane-Keeping System (LKS), which allows AVs to drive continuously in the center of the lane [16], and by reducing the lateral safety width used as safety buffers between vehicles. In a study conducted in Great Britain [85], the authors presented five new optimized highway cross-sections with non-standard dimensions. The outer lane next to the hard shoulder was always reserved exclusively for autonomous freight vehicles. They also varied the lane width from 2.5 m to 5.0 m and their number of lanes from 3 to 4. Figure 11 shows a comparison of lane widths for CVs according to Croatian regulations [84] and the reduced lane widths for AVs according to [72].

Figure 11.

Comparison of lane widths for CVs and reduced lane widths for AVs.

To summarize, the design rules described above will be less strict for AVs (shorter stopping sight distance, smaller vertical curve radii, longer straight sections, narrower lanes, etc.). Less strict rules can lead to higher safety risks in mixed traffic flows where both AVs and CVs are present. Therefore, new road infrastructure can only be designed according to new rules adapted for AVs if only AVs are traveling on the roads, i.e., if there are no CVs in the traffic flow [86].

6.2. Redesign of Existing Road Infrastructure

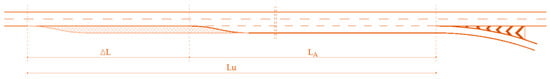

However, some parts of the road infrastructure can be adapted for mixed traffic of AVs and CVs. An example is provided below. To improve traffic safety, the optimal length of deceleration lanes for mixed traffic of CVs and AVs with different levels of automation needs to be determined. Shorter deceleration lanes cause speed changes on the main carriageway, while longer deceleration lanes allow a more even distribution of speeds on the main carriageway and give exiting vehicles enough time to slow down. At highway interchanges, incoming traffic enters the highway via an entrance ramp (on-ramp), while outgoing traffic leaves the highway via an exit ramp (off-ramp). Poorly designed off-ramps cause disruption on the main carriageway, while poorly designed on-ramps reduce the throughput capacity of the ramp and traffic safety [87]. The study [88] examines the length of deceleration lanes at highway exits adapted to AV traffic, as these are high-risk locations with a high number of traffic accidents.

A study [88] was conducted with drivers operating an SAE L3 vehicle in a driving simulator on a highway. L3 vehicles require the driver to take control when the environment is not detected or in unforeseen situations, such as the appearance of deceleration lanes on the highway and required lane change maneuvers. The study showed that the reaction time of drivers who begin braking in L3 vehicles immediately before reaching the deceleration lane increases because they must take control of the vehicle. It was found that the time required for the driver to take control of the vehicle, i.e., takeover time (tc), is 5 or 8 s, and that consequently, the length of the deceleration lanes should be increased.

The authors of this paper conducted a study [89] to analyze the effects of AVs on the length of deceleration lanes on highways. The additional deceleration lane length required for AVs, that is, the extension of the deceleration lane (∆L), was determined using Equation (1):

where ∆L is the extension of the deceleration lane (m), Vp is the design speed on the main carriageway (km/h), and tc is the takeover time (s).

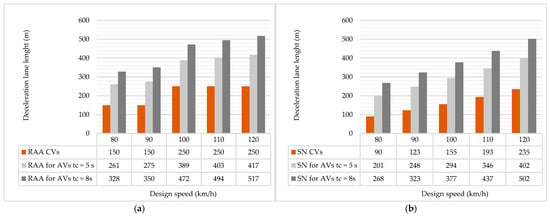

Equation (1) is derived from the equation for determining speed. The speed is given in kilometers per hour (km/h) and divided by 3.6 to obtain the length in meters (m). When calculating the extension of the deceleration lane ∆L, data from the above-mentioned literature [88] was used, which states that the takeover time (tc) is 5 s or 8 s. The calculated extensions (∆L) were then added to the existing lengths of deceleration lanes (LA) for design speeds of 80 km/h to 120 km/h prescribed in the German guidelines for the design of highways (RAA) [90] and the Swiss norm (SN) [91], resulting in the total length of deceleration lanes (Lu) adapted to the operation of AVs (Figure 12 and Figure 13) [89]. As shown in Figure 13, the total length of the deceleration lanes (Lu) adapted to the operation of AVs can be more than twice as long as the total length of the deceleration lanes (Lu) for CVs, depending on the takeover time (tc) [89].

Figure 12.

The total length of deceleration lanes (Lu) suitable for the operation of AVs. Adapted from [91], with permission from University of Zagreb Faculty of Civil Engineering, 2025.

Figure 13.

The total length of deceleration lanes (Lu): (a) according to RAA for CVs and potentially for AVs, considering takeover times of 5 and 8 s; (b) according to SN for CVs and potentially for AVs, considering takeover times of 5 and 8 s.

Such a design change can be implemented in the early stages of AV introduction into traffic flow, as it does not affect the safety of CVs. Research [88] has shown that the length of deceleration lanes is also influenced by the mean deceleration value, since AVs are assumed to brake continuously and deceleration takes longer. As a result, the acceleration value is lower, and therefore, the deceleration lane may need to be even longer. A similar approach can be applied to other road elements if redesign does not affect the safety of all road users.

A list of symbols used in the manuscript is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

List of symbols used in the manuscript.

7. Discussion

In summary, the optimal geometric design of a highway depends on whether new infrastructure is being built, or existing infrastructure is being reconstructed and is also influenced by the share of AVs in the overall transportation system [89]. Table 5 analyzes potential changes in highway design related to the share of AVs (0%, 50%, or 100%) through either constructing new infrastructure for AVs or reconstructing existing infrastructure. When reconstructing existing infrastructure, the financial impact should also be evaluated in terms of economic efficiency of space use, throughput capacity, and traffic safety.

Table 5.

Analysis of the design elements of highways concerning the share of autonomous vehicles. Adapted from [91], with permission from University of Zagreb Faculty of Civil Engineering, 2025.

The development of AVs will impact the design of physical road infrastructure. Below are brief conclusions on changes in geometry. Stopping distances required for AVs on highways could be reduced by 21% to 33%, depending on design speed, and minimum radii for crest curves could be reduced by 67% to 72%. AVs will also influence the conditions for using straight sections of horizontal geometry, which will be eliminated. In addition, lane width could be reduced by 0.65 to 0.75 m by using the LKS. Design rules will be less strict for AVs. This can lead to a high safety risk in mixed traffic flows where both AVs and CVs are present. Therefore, new transportation infrastructure can only be designed according to new rules adapted for AVs if only AVs are traveling on the roads, i.e., if there are no CVs in the traffic flow. However, some parts of road infrastructure could be redesigned without affecting the safety of CVs. An example is changing the length of the deceleration lane. The total length of deceleration lanes adapted for AVs can be more than twice as long as those for CVs. Such a design change can be introduced in the early stages of AV integration into the traffic flow, as it does not affect the safety of CVs.

Technologies such as platooning and communication strategies could improve traffic flow and capacity. However, vehicle interference in traffic flow is not possible if the platoon size is too large, and communication between vehicles can be unsatisfactory. The use of dedicated lanes for AVs only has proven to be a safe way to introduce AVs into mixed traffic, but it may lead to inadequate use of the roadway. In addition, constructing a new lane is expensive, and converting an existing lane can lead to traffic congestion. A negative impact on traffic flow can also result from ride-hailing, which may increase congestion due to higher demand. Furthermore, the benefits of AVs in traffic flow could be negated by changes in driver behavior, availability, and demand, leading to congestion and negating the advantages AVs could provide. There are numerous problems with traffic signs, especially regarding sensor recognition in AVs. These issues should be addressed systematically and internationally.

8. Conclusions

Many researchers, developers, and manufacturers see AD as the future of transportation. AD has become a popular topic and is increasingly becoming a reality as technology advances. It also presents challenges, particularly in safety and the complexity of adapting to certain traffic situations.

AVs hold great promise for improving road safety by reducing human error, one of the main causes of accidents. However, their full implementation also poses challenges, especially during the transition phase when AVs and CVs coexist. Some safety benefits of AVs include preventing accidents caused by distracted, fatigued, or drunk drivers, as well as those resulting from lack of experience or poor judgment; autonomous systems can react faster than humans, potentially preventing collisions or mitigating their severity; they can maintain consistent speeds and distances, reducing stop-and-go traffic and improving overall traffic flow; widespread adoption of these vehicles could significantly reduce the number of road accidents and casualties; and they have advanced sensors and safety systems to detect and avoid hazards, including pedestrians and other vehicles.

To support the implementation of AVs, many challenges must be considered. AD eliminates the human factor, which is beneficial for safety; however, missing information collected by sensors and technological errors can endanger passengers and other road users. Sensors must function accurately and consistently in all driving environments, algorithms must be flawless, and antivirus systems must protect against cyberattacks. Therefore, ensuring security and safety, gaining public trust, and addressing legal concerns must be priorities in further development. Addressing concerns about the safety and reliability of AVs by transparently presenting existing problems and possible solutions is important for public acceptance of these relatively new vehicles, which are expected to eventually replace CVs. To determine the degree of public acceptance, future research should conduct surveys or behavioral studies. Furthermore, the trolley problem in AD is worth mentioning—an ethical dilemma where the vehicle must choose between two unfavorable scenarios. AVs are also expected to impact the labor market, as many professional drivers, such as delivery drivers, taxi drivers, and public transportation drivers, may lose their jobs. Finally, it is necessary to establish operational regulations, safety standards, and guidelines for civil and transportation engineers.

This review paper briefly outlines the existing problems associated with introducing AVs into the transportation network. It discusses the current level of automation and technologies, describes the impact of AVs on traffic flow, and highlights the main design parameters that affect the geometric design of highways suitable for AV operation. It diverges from the predominant focus in the existing literature, which is on the development of digital infrastructure for AVs. The authors of this paper aimed to provide as much insight as possible into the impact of AVs on necessary road infrastructure adaptations and the main design parameters affecting road geometry for AV operation.

Further research on this topic should be updated and supplemented with new findings from the subject area, which will largely depend on the direction and extent of future development of AVs. This study provides only a brief overview of current research in this field, which will likely expand considerably in the coming years, given the relevance of the subject. This applies to the ongoing technological development of AVs, which will lead to improved understanding of traffic flow modeling when both AVs and CVs are present, and eventually to the development of new guidelines for planning and designing road infrastructure adapted to AVs.

Also, future research should include (1) empirical validation of AV behavior in complex geometric alignments using naturalistic driving data; (2) establishing a cost-effective infrastructure adaptation prioritization framework applicable to different stages of AV penetration; (3) analysis of urban road infrastructure; and (4) assessment of AV perception capabilities under extreme weather conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Č.I. and T.Dž.; methodology, A.Č.I. and T.Dž.; formal analysis, A.Č.I. and T.Dž.; investigation, A.Č.I.; resources, A.Č.I. and V.D.; data curation, T.Dž. and A.Č.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Č.I. and T.Dž.; writing—review and editing, V.D.; visualization, T.Dž.; supervision, V.D.; project administration, A.Č.I. and T.Dž. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data of this review paper have been collected from previously published research articles available in current scientific literature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AV | Autonomous Vehicle |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CV | Conventional Vehicle |

| EU | European Union |

| EC | European Commission |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| AD | Autonomous Driving |

| GPS | Global Positioning Systems |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Units |

| RADAR | Radio Detection and Ranging |

| LIDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| ADAS | Advanced Driver Assistance Systems |

| ADS | Automated Driving Systems |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle connectivity |

| V2I | Vehicle-to-Infrastructure connectivity |

| CACC | Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control |

| ACC | Adaptive Cruise Control |

| A.M. | Advanced Merging |

| HCM | Highway Capacity Manual |

| CAF | Capacity Adjustment Factor |

| LKS | Lane-Keeping System |

References

- Petrović, Đ.; Mijailović, R.; Pešić, D. Traffic Accidents with Autonomous Vehicles: Type of Collisions, Manoeuvres and Errors of Conventional Vehicles’ Drivers. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 45, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, A.; Shevtsova, A.; Vasilieva, V. Development of approach to reduce number of accidents caused by drivers. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 50, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džambas, T.; Čudina Ivančev, A.; Dragčević, V.; Vujević, I. Safety and environmental benefits of intelligent speed bumps. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 73, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Official Website: Mobility and Transport. Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/eu-road-fatalities-drop-3-2024-progress-remains-slow-2025-03-18_en#:~:text=Today%2C%20the%20European%20Commission%20has,to%20600%20fewer%20lives%20lost (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- European Commission. Official Website: Mobility and Transport–Road Safety. Available online: https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/eu-road-safety-policy/what-we-do_en (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- World Health Organisation, Official Website: Road Traffic Injuries. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Zhao, H.; Meng., M.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Li, L. A survey of autonomous driving frameworks and simulators. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatov, S.V. Analysis of factors affecting the likelihood of road accidents. Transp. Eng. 2022, 6, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Woo, B.; Chang, Y.; Tak, S. Road Design on Human Driver Accidents vs. Automated Vehicle Failures: Comparison with Real-World Field Data. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 159545–159560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahrig, S.K.; Stein, F.J. Dead Reckoning and Cartography Using Stereo Vision for an Autonomous Car. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEGRSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, in Intelligent Robots and Systems, Kyongju, Republic of Korea, 17–21 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzaman, A.; Muhammad, W. A Comprehensive Review of Environmental and Economic Impacts of Autonomous Vehicles. Control Syst. Optim. Lett. 2024, 2, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, B.; Xing, Y.; Tian, D.; Li, L.; Hu, Z.; Na, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Milestones in Autonomous Driving and Intelligent Vehicles: Survey of Surveys. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Mao, S.; Lee, J.J. A novel car-following model for adaptive cruise control vehicles using enhanced intelligent driver model. Transp. Lett. 2024, 17, 702–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavanas, N. Autonomous Road Vehicles: Challenges for Urban Planning in European Cities. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Hossain, K. Connected and Autonomous Vehicles and Infrastructures: A Literature Review. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 16, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivasakan, H.; Kalra, R.; O’Hern, S.; Fang, Y.; Xi, Y.; Zheng, N. Infrastructure requirement for autonomous vehicle integration for future urban and suburban roads—Current practice and a case study of Melbourne, Australia. Transp. Res. Part A 2021, 152, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengilimoglu, O.; Carsten, O.; Wadud, Z. Implications of automated vehicles for physical road environment: A comprehensive review. Transp. Res. Part E 2022, 169, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y. Enhancing Mixed Traffic Flow with Platoon Control and Lane Management for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2025, 25, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengilimoglu, O.; Carsten, O.; Wadud, Z. The effects of infrastructure quality on the usefulness of automated vehicles: A case study for Leeds, UK. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 121, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, P.; Ponti, M.; Studer, L. Analysis of the driver’s stress level while driving in Truck Platooning. Multimodal Transp. 2025, 4, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J. Cooperative Formation of Autonomous Vehicles in Mixed Traffic Flow: Beyond Platooning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 15951–15966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.P.; Ferreira, S.; Lobo, A.; Cunha, L. Representations of truck platooning acceptance of truck drivers, decision-makers, and general public: A systematic review. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 104, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Diaz, M.; Al-Haddad, C.; Soriguera, F.; Antoniou, C. Platooning of connected automated vehicles on freeways: A bird’s eye view. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 58, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, T.; Campos Ferreira, M.; Duarte, S.P.; Ferreira, S. Simulator and on-road testing of truck platooning: A systematic review. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2025, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Zhou, H. Exploring Potential Critical Content of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles for Transportation Engineering Courses: A National Survey. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2024, 2678, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijermars, W.; Hula, A.; Chaudhry, A.; Sha, S.; Zwart, R.; Mons, C.; Boghani, H. LEVITATE: Road safety impacts of Connected and Automated Vehicles. Loughborough 2021, 1–11. Available online: https://publications.ait.ac.at/en/publications/levitate-road-safety-impacts-of-connected-and-automated-vehicles/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Tafidis, P.; Farah, H.; Brijs, T.; Pirdavani, A. Safety implications of higher levels of automated vehicles: A scoping review. Transp. Rev. 2022, 42, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghulaxe, V. Driving The Future: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Autonomous Vehicles. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Thill, J.C. Impacts of connected and autonomous vehicles on urban transportation and environment: A comprehensive review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, B.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, W. Impacts of Different Driving Automation Levels on Highway Geometric Design from the Perspective of Trucks. Hindawi J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orieno, O.H.; Ndubuisi, N.L.; Ilojianya, V.I.; Biu, P.W.; Odonkor, B. The future of autonomous vehicles in the US urban landscape: A review: Analyzing implications for traffic, urban planning, and the environment. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xiu, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhang, K. The Effects of Autonomous Vehicles on Traffic Efficiency and Energy Consumption. Systems 2023, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, M.; Yang, L.; Cui, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, N.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, P.; et al. Mitigation policies interactions delay the achievement of carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/climate-change-mitigation-reducing-emissions (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- European Commission. Research and Innovation. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe_en (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fayyaz, M.; González- González, E.; Nogués, S. Autonomous Mobility: A Potential Opportunity to Reclaim Public Spaces for People. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezwana, S.; Lownes, N. Interactions and Behaviors of Pedestrians with Autonomous Vehicles: A Synthesis. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 722–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K. Highway life-cycle cost analysis under the autonomous vehicles scenario. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2024, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, M.; Shetty, T.G.N.; Kumar, P. Working of Autonomous Vehicles. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2019, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Islam, R.M.; Huang, P.; Ho, C. Overcoming Autoware-Ubuntu Incompatibility In Autonomous Driving Systems-Equipped Vehicles: Lessons Learned. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, S. Current Stage of Autonomous Driving Through a Quick Survey for Novice. Am. Sci. Res. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. (ASRJETS) 2020, 73, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- SAE J3016; Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021.

- Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Easa, S.M.; Zhou, H.; Lai, Y.; Chen, W. Sight Distance of Automated Vehicles Considering Highway Vertical Alignments and Its Implications for Speed Limits. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2023, 16, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, A.; Barari, A.; Adibi-Asl, H. Stability Control of an Autonomous Vehicle in Overtaking Manoeuvre Using Wheel Slip Control. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2020, 18, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Molina, F.E.; Valladolid, J.D.; Bautista, P.B.; Quinde, E.; Villa Uvidia, R.; Vazquez Salazar, J.S.; Miranda, G.J.A. Backcasting Analysis of Autonomous Vehicle Implementation: A Systematic Review. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, D.; Horváth, B. Steady-Speed Traffic Capacity Analysis for Autonomous and Human-Driven Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, W.; Pariota, L. Macroscopic evaluation of traffic flow in view of connected and autonomous vehicles: A simulation-based approach. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 79, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriesti, S.; Ponti, M.; Studer, L.; Maja, R.; Aleccia, O.; Lohmiller, J.; Gordillo, I.V. Definition of a Python script for the micro-simulation of the truck platooning system. Transport 2021, 36, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebisi, A.; Liu, Y.; Schroeder, B.; Ma, J.; Cesme, B.; Jia, A.; Morgan, A. Developing Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) Capacity Adjustment Factors (CAF) for Connected and Automated Traffic on Freeway Segments. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2021, 148, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Chen, H. Impacts of autonomous vehicles on freeway with conditional isolated and dedicated lanes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rad, S.R.; Farah, H.; Taale, H.; van Arem, B.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Design and Operation of Dedicated Lanes for Connected and Automated Vehicles on Motorways: A Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 117, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makahleh, H.Y.; Abdelfatah, A.; Badrawi, H.A. Assessing the Impacts of Autonomous Vehicles for Freeway Safety. In Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on New Technologies (NewTech’24), Barcelona, Spain, 25–27 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebpour, A.; Mahmassani, H.S.; Elfar, A. Investigating the effects of reserved lanes for autonomous vehicles on congestion and travel time reliability. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmud, J.; Williams, T.; Outwater, M.; Bradley, M.; Kalra, N.; Row, S. Updating Regional Transportation Planning and Modeling Tools to Address Impacts of Connected and Automated Vehicles, Volume 2: Guidance; National Cooperative Highway Research Program; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhrmoosavi, F.; Kamjoo, E.; Zockaie, A.; Mittal, A.; Fishelson, J. Assessing the Network-Wide Impacts of Dedicated Lanes for Connected Autonomous Vehicles. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Yamamoto, T. Modeling Connected and Autonomous Vehicles in Heterogeneous Traffic Flow. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 490, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Li, L. Effect of Connected Automated Driving on Traffic Capacity. In Proceedings of the 2017 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Jinan, China, 20–22 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, I.; Zheng, J.; Severino, A.; Jamal, A. Assessing the barriers and implications of autonomous vehicles: Implementation in sustainable cities. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, M.M.; Bardaka, E.; Samandar, M.S. Differential impacts of autonomous and connected-autonomous vehicles on household residential location. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 32, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, M.D.; Kockelman, K.M.; Gurumurthy, K.M.; Bischoff, J. Congestion pricing in a world of self-driving vehicles: An analysis of different strategies in alternative future scenarios. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 98, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Park, J.; Sung, Y.; Park, Y.W.; Cho, K. Virtual Scenario Simulation and Modeling Framework in Autonomous Driving Simulators. Electronics 2021, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, S.; Yan, W.; Shen, Q.; Wang, C.; Yang, M. Choose Your Simulator Wisely: A Review on Open-source Simulators for Autonomous Driving. Robotics 2023, 9, 4861–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Waymo Team. Simulation City: Introducing Waymo’s Most Advanced Simulation System Yet for Autonomous Driving. Available online: https://waymo.com/blog/2021/06/SimulationCity.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Pony.ai, Technology. Available online: https://pony.ai/tech?lang=en (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- DiDi, Didi’s Autonomous Driving. Available online: https://www.didiglobal.com/science/intelligent-driving (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Li, M.; Luo, Q.; Fan, J.; Ning, Q. Impact Analysis of Smart Road Stud on Driving Behavior and Traffic Flow in Two-Lane Two-Way Highway. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.H.; Ali, F.; Altamimi, A.B.; Gulliver, T.A. Effect of human-driven, autonomous, and connected autonomous vehicles on geometric highway design. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 127, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC); Transportation Research Board (TRB). Highway Capacity Manual; National Research Council (NRC); Transportation Research Board (TRB): Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- PTV Vissim. Available online: https://www.ptvgroup.com/en/products/ptv-vissim (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Laufer, J. Freeway Capacity, Saturation Flow and the Car Following Behavioural Algorithm of the VISSIM Microsimulation Software; Maunsell Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2007; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tight, M.; Sun, Q.; Kang, R. A Systematic review: Road infrastructure requirement for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1187, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čudina Ivančev, A.; Dragčević, V.; Džambas, T. Road infrastructure requirements to accommodate autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the CETRA 2022, 7th International Conference on Road and Rail Infrastructure, Pula, Croatia, 11–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, S.; Kim, S.; Yu, H.; Lee, D. Analysis of Relationship between Road Geometry and Automated Driving Safety for Automated Vehicle-Based Mobility Service. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.M.; Barrette, T.P.; Carlson, P.J. Evaluation of the Effects of Pavement Marking Characteristics on Detectability by ADAS Machine Vision; National Cooperative Highway Research Program; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Cai, X.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Ying, S. A review of research on vehicle detection in adverse weather environments. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 12, 1452–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboz, L.; Raileanu, I.C.; Krause, J.; Norman-López, A.; Weitzel, M.; Ciuffo, B. Scenarios for the deployment of automated vehicles in Europe. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 32, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéguen, N.; Meineri, S.; Eyssartier, C. A pedestrian’s stare and drivers’ stopping behavior: A field experiment at the pedestrian crossing. Saf. Sci. 2015, 75, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F. Studying Pedestrian’s Unmarked Midblock Crossing Behavior on a Multilane Road When Interacting with Autonomous Vehicles Using Virtual Reality. Ph.D. Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gkyrtis, K.; Kokkalis, A. An Overview of the Efficiency of Roundabouts: Design Aspects and Contribution toward Safer Vehicle Movement. Vehicles 2024, 6, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Cicchino, J.B.; Reagan, I.J.; Monfort, S.S.; Gershon, P.; Mehler, B.; Reimer, B. Use of Level 1 and 2 driving automation on horizontal curves on interstates and freeways. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 89, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, S.; Dai, Z.; Chen, Z.; Pan, C.; Xu, J. A Study of Vehicle Lateral Position Characteristics and Passenger Cars’ Special Lane Width on Expressways. Eng. Rep. 2023, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, P. Optimization of Geometric Road Design for Autonomous Vehicle; Degree project; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, K. Impact of Autonomous Vehicles on the Physical Infrastructure: Changes and Challenges. Designs 2021, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravilnik o Osnovnim Uvjetima Kojima Javne Ceste Izvan Naselja i Njihovi Elementi Moraju Udovoljavati sa Stajališta Sigurnosti Prometa (NN 110/01, 90/22), Zagreb, Croatia, 2001. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2001_12_110_1829.html (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Jehanfo, H.; Hu, S.; Kaparias, I.; Preston, J.; Zhou, F.; Stevens, A. Redesigning Highway Infrastructure Systems for Connected Autonomous Truck Lanes. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2022, 148, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, M.; Mauro, R.; Pompigna, A.; Isaenko, N. Road Design Criteria and Capacity Estimation Based on Autonomous Vehicle Performances. First Results from the European C-Roads Platform and A22 Motorway. Transp. Telecomun. 2021, 22, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemenčić, A. Oblikovanje Cestovnih Čvorišta Izvan Razine; Građevinski Institut Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, F.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L. The Compatibility between the Takeover Process in Conditional Automated Driving and the Current Geometric Design of the Deceleration Lane in Highway. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čudina Ivančev, A.; Dragčević, V. Utjecaj autonomnih vozila na odabir projektnih elemenata autocesta. In Proceedings of the 8. Simpozij Doktorskog Studija Građevinarstva, Zagreb, Croatia, 5–6 September 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FGSV. Richtlinen für die Anlage von Autobahnen (RAA); FGSV: Cologne, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- SN 640 261; Knoten, Kreuzungsfreie Knoten. Schweizer Norm: Winterthur, Switzerland, 1998.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).