1. Introduction

Efficient pavement distress assessment plays a vital role in modern road asset management, enabling informed infrastructure preservation, enhanced traffic safety, and cost-effective maintenance planning. Traditionally, pavement condition evaluation has relied on manual visual inspections, where trained personnel identify surface defects such as cracks, potholes, rut depths, and patches directly on site. While this method provides detailed observations, it suffers from several limitations: it is labor-intensive, time-consuming, subjective, and inconsistent, especially when applied to large-scale road networks [

1,

2]. Moreover, manual surveys expose inspectors to hazardous traffic conditions, making frequent, network-wide assessments impractical under limited resources [

3,

4].

To overcome these challenges, automated pavement condition survey systems have been introduced, integrating high-resolution imaging sensors, onboard computing, distance measurement tools, and Global Positioning System (GPS) modules to improve efficiency, accuracy, and consistency in pavement data collection [

5,

6]. Automated pavement inspection generally involves multiple stages, including pavement surface classification, distress detection and quantification, and condition rating based on the type and severity of detected distress [

2]. In Cambodia, for example, the Road Measurement Data Acquisition System (ROMDAS) is employed by the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT) for pavement monitoring, as shown in

Figure 1. ROMDAS utilizes downward-facing high-resolution cameras mounted on survey vehicles to continuously capture pavement images at driving speeds, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The collected imagery is synchronized with GPS and distance measurements, allowing accurate georeferencing of pavement distress such as cracks, potholes, and patches. This approach has significantly enhanced Cambodia’s capability to maintain comprehensive and up-to-date pavement condition records, facilitating data-driven maintenance planning.

Although data acquisition technologies have advanced, the automated interpretation of captured images into pavement condition assessment remains crucial for effective maintenance planning and optimal repair strategies. Instead of relying on labor-intensive measurements, image processing methods enable the automated quantification of pavement distress severity. These quantified features can then be systematically converted into standardized evaluation indices such as the Pavement Condition Index (PCI) or the Maintenance Control Index (MCI), thereby supporting data-driven maintenance intervention [

7,

8]. In Japan, the MCI is widely adopted by road administrators to guide maintenance interventions based on its severity. This index is primarily derived from distress density, such as crack ratios, which require careful measurement to ensure accuracy. The definition and calculation of the MCI can be found in relevant references [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In recent years, advances in image processing have further improved this process by reducing subjectivity and enhancing consistency. However, early approaches that depended on handcrafted features and heuristic algorithms (e.g., thresholding, region-based segmentation) often failed to generalize across diverse pavement surface conditions and struggled with detecting low-contrast features like fine cracks against complex backgrounds [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Latest advances in deep learning have revolutionized and overcome the limitations of conventional methods in pavement distress detection by enabling models to learn discriminative features automatically from large-annotated datasets [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Among deep learning-based detectors, two major approaches dominate the literature: region-based convolutional neural network (CNN) detectors and one-stage detectors such as You Only Look Once (YOLO). Convolutional architectures, such as Faster R-CNN, have been widely applied to pavement distress detection, often incorporating ResNet and Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) backbones to improve feature extraction and enhance detection accuracy [

22]. However, this approach still requires intensive feature computation when handling numerous proposals [

23]. On the other hand, the YOLO model has gained popularity for its high inference speed, real-time processing capability, and robust performance in complex environments [

3,

24,

25]. Additional improvements have been proposed by integrating sub-networks and advanced IoU-based loss functions to enhance detection precision [

19,

26]. Despite these advancements, such detection models typically yield bounding boxes rather than precise distress quantification, as they cannot provide pixel-level measurements of critical metrics such as crack width, length, or area, which are essential for severity assessment and maintenance decision-making [

27,

28].

To overcome this shortcoming, segmentation-based methods have been introduced to provide pixel-level contours of pavement distress. A key advantage over detection methods is their capability to obtain the actual area of distress, achieving a result with pixel-level precision [

29]. This is attributed to the higher model complexity and richer parameterization of segmentation networks [

30]. By distinguishing between distressed and non-distressed pixels, these methods enable a fine-grained analysis, allowing for a prediction label to be assigned to individual pixels.

Among the most widely used deep learning architectures for pavement distress segmentation are convolutional neural network (CNN) based models such as U-Net, DeepLabV3+, Mask R-CNN, SegNet, and domain-specific frameworks like CrackNet. U-Net, a classic U-shaped encoder–decoder architecture, efficiently localizes features using skip connections that fuse feature maps between the downsampling (encoder) and upsampling (decoder) paths, enabling faster processing and refined segmentation, as utilized by Li et al. [

31] and adapted by Lau et al. [

32] with a pre-trained ResNet-34 encoder to better distinguish distress regions from intact pavement. Another state-of-the-art approach is DeepLabV3+, an encoder–decoder model for pavement crack segmentation that commonly incorporates a pre-trained CNN encoder and an Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module to capture multi-scale context, often enhanced with an attention mechanism to handle diverse environmental conditions, as demonstrated by Li et al. [

33] and Sun et al. [

34]. For instance segmentation, Mask R-CNN, an improved R-CNN variant, integrates image data with pixel-segmented annotations to precisely identify and position cracks, a method applied by Wang et al. [

35] and modified by Dong et al. [

36] to extract detailed crack properties. Alternatively, SegNet provides an efficient encoder–decoder structure for scene understanding tasks and crack segmentation in concrete and asphalt pavement, with Chen et al. [

37] presenting a modified version capable of end-to-end, pixel-by-pixel training for arbitrary image sizes. Finally, models like CrackNet developed by Kyem et al. [

38] integrate specialized modules and refinement operations to address the challenge of accurately segmenting tiny and subtle cracks across varying scales in high-resolution images.

Despite their documented success, a critical limitation shared by these traditional supervised models is their reliance on large volumes of meticulously annotated ground-truth data. Their generalization to real-world conditions is directly dependent on the quality and diversity of the training datasets. The necessity for extensive labeling introduces a significant bottleneck in practical deep learning applications for remote sensing image segmentation [

13]. Xu et al. [

39] proposed an end-to-end framework for the automatic detection and segmentation of tunnel cracks, which balances annotation cost with performance by enhancing YOLOv8. Although the model effectively detects and segments thin cracks and ignores complex backgrounds, the annotation process remains labor-intensive. Specifically, the pixel-level labeling required for segmentation, which involves drawing precise polygons, can still take several minutes per image. Moreover, the inherent variability, resolution differences, and environmental complexity of remote sensing data make the labeling process even more demanding [

40]. Consequently, developing segmentation models that can operate effectively with minimal labeled data offers the potential for reductions in annotation costs and time.

Recent breakthroughs in foundation models introduce a paradigm shift that minimizes the need for extensive manual labeling while ensuring better generalization to unseen images. The Segment Anything Model (SAM), a foundational model from Meta AI Research, significantly advances image segmentation by leveraging generalized learning across diverse, massive datasets. This training allows SAM to establish a robust pre-training objective, covering a wide array of applications and often outperforming other models in complex or noisy environments [

41,

42]. SAM offers powerful zero-shot segmentation capabilities, generating high-fidelity masks from simple input prompts (e.g., points, bounding boxes) without task-specific training [

43]. Nonetheless, SAM is not a complete solution for pavement distress analysis; its performance is contingent on receiving accurate prompts, and it can underperform on slender, low-contrast features like cracks without further refinement [

44].

Furthermore, if the image includes relevant details, such as coordinates as shown in the ROMDAS image, it is crucial to extract this information in addition to any identified distress. Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology plays a crucial role in retrieving text from different types of documents, including handwritten content, and converting it into digital text [

45]. As an OCR engine, Tesseract, becomes an efficient and reliable tool for recognizing and extracting text from images [

46]. For instance, Tesseract OCR has found extensive use in applications such as reading letters and numbers on vehicle license plates when paired with deep learning detection systems [

47].

This study bridges this critical gap by proposing a lightweight framework that synergizes the strengths of object detection, foundation models, and metadata parsing to create an end-to-end solution for pavement distress analysis. Our methodology leverages a YOLOv8 model to automatically generate high-quality bounding box prompts for distress regions. These prompts are then fed into SAM to produce initial pixel-level segmentation masks. To address SAM’s limitations with thin cracks, we introduced a local refinement module to enhance mask accuracy. Finally, to enable geospatial localization, the Tesseract OCR engine is employed to extract embedded GPS coordinates directly from the survey imagery, linking each quantified distress to a precise geographical location. The proposed framework is validated using an open-source pavement image dataset from Yamanashi, Japan. The results demonstrate robust performance in automated detection, precise segmentation, accurate quantification of distress dimensions, and seamless geospatial mapping. By integrating advanced deep learning and foundation segmentation models, this work provides a scalable, efficient, and comprehensive tool for automated pavement condition assessment, contributing to data-driven infrastructure management practices.

2. Methods

2.1. Proposed Framework

The objective of this research is to develop and implement an end-to-end framework for automated pavement distress detection and quantification. In addition to quantitative assessment, this process also aims to localize the distress on a map for improved visualization and informed decision-making by road agencies.

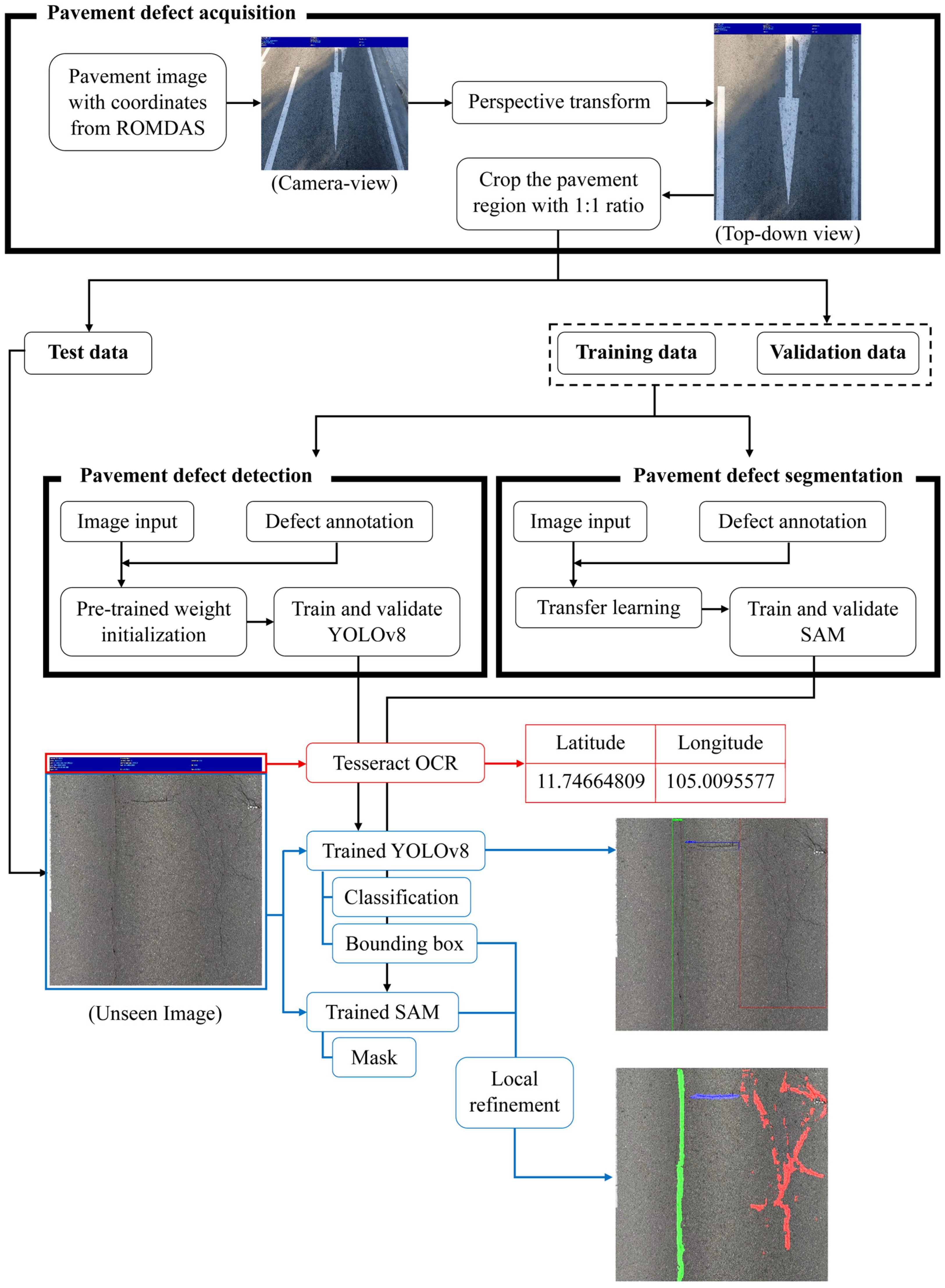

Figure 3 illustrates the process in this study, which begins with data preparation, where images from a vehicle-mounted camera are transformed from a horizontal perspective to a top-down view. This transformation, known as Inverse Perspective Mapping (IPM), uses a homography to map pixels from the camera’s perspective onto a different 2D coordinate frame, creating a bird’s-eye view of the scene [

48,

49]. After this transformation, the images are cropped to a 1:1 aspect ratio to prepare them for input to the subsequent detection and segmentation model.

A two-step process based on a modified YOLOv8 and the SAM was proposed to handle distress detection and segmentation. The dataset of pavement cracks was divided into training and validation sets, and each image was manually annotated to create ground truth data for both detection and segmentation. The first step involves using YOLOv8 for pavement crack detection, which classifies and localizes cracks by generating bounding boxes around them. These bounding boxes serve as prompts for the second step, which utilizes the SAM for crack segmentation. By using the bounding boxes from the first step as prompts and local refinement, the proposed method can segment the detected pavement cracks with greater purpose and accuracy, isolating the exact pixels that constitute the distress.

Simultaneously, a region containing pixel-based coordinate digits, typically in a blue header, is extracted using Tesseract OCR. This enables the system to save the latitude and longitude alongside the identified cracks. Since these coordinate digits are standardized and associated with the ROMDAS, the pre-trained Tesseract OCR model can be used directly without retraining, unlike scenarios involving distorted or irregular text (e.g., license plate or traffic signs). Once the entire process is complete, pavement cracks are automatically detected, their severity quantified, and their location mapped onto a geospatial platform. This integrated approach allows road agencies to efficiently manage and implement timely maintenance planning.

2.2. Top-Down Perspective Transformation Based on Homography

The transformation from a camera’s perspective view to a metrically accurate top-down (bird’s-eye) view is fundamentally governed by homography, a projective transformation matrix. This process corrects for perspective distortion and yields a rectified image with a uniform scale, making it suitable for subsequent metric analysis, such as measuring actual object sizes or distances. The core of this transformation is the homography matrix, which maps points from one plane to another.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, four reference points were manually selected on the pavement region. These points form a trapezoidal region due to perspective distortion caused by the oblique camera angle. Under an ideal bird’s-eye view, however, these same points would form a perfect rectangle, demonstrating the geometric deformation present in the raw images. The homography matrix mathematically maps the pixel coordinates from the original image plane to their corresponding positions on a rectified, top-down plane. The homography matrix

H encapsulates this transformation and is defined as:

where

H is the 3 × 3 homography matrix:

where

H is estimated using the four pairs of the corresponding points:

In this study:

= manually selected source points in the original pavement image (See

Figure 4 (

left)).

= destination points on the target rectangular plane (See

Figure 4 (

right)).

For implementation, the homography matrix

H was computed in a Python (3.12) script utilizing cv2.getPerspectiveTransform from the OpenCV library [

50]. The four corner points of the trapezoidal pavement region were manually defined. Their corresponding destination points were calculated based on a known physical scale (pixels per meter) to create a rectangular output image of specified real-world dimensions (e.g., 3.0 m × 3.8 m). The perspective warping was then performed using cv2.warpPerspective, generating a rectified pavement image with a uniform scale. This rectified view eliminates perspective distortion, providing a metrically accurate representation of the pavement for further analysis. All the images used in this study, including those for training, validation, and testing, underwent this transformation process prior to being input into the crack detection and segmentation framework.

2.3. YOLOv8 Model for Pavement Crack Detection

YOLOv8 represents a state-of-the-art advancement in single-stage object detection. While retaining the backbone-neck-head design paradigm established in earlier YOLO models, it introduces several architectural refinements that improve both accuracy and computational efficiency. The model processes an input image in a single forward pass, simultaneously predicting bounding boxes, object classes, and confidence scores.

The backbone is responsible for hierarchical feature extraction. It employs convolutional layers with cross-stage partial (CSP) connections and bottleneck structures, which progressively reduce spatial resolution while expanding channel depth. This design produces a multi-scale feature hierarchy that captures both fine-grained details and high-level semantic information. The neck aggregates these multi-scale features through an enhanced feature fusion strategy. Building upon the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), YOLOv8 incorporates a Path Aggregation Network (PAN), which adds a complementary bottom-up pathway to the FPN’s top-down flow [

51,

52]. This bi-directional information exchange enriches the feature maps with both semantic and localization cues, thereby improving detection robustness across objects of different sizes. The head executes the final detection tasks. Unlike earlier coupled designs, YOLOv8 adopts a decoupled head structure that separates classification (object categories) from regression (bounding box coordinates). This reduces inference between two objectives, stabilizes training, and yields more accurate predictions. The output includes the bounding boxes’ coordinates, class, and confidence scores.

Compared to two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN, which rely on a Region Proposal Network (RPN) followed by classification, YOLOv8 performs detection in a single stage [

53]. This streamlined design significantly reduces computational overhead and enables real-time inference without sacrificing detection quality. The complete architecture of YOLOv8 is depicted in

Figure 5.

2.4. Architecture of SAM for Pavement Crack Segmentation

Traditional segmentation models typically require training for specific tasks and are limited in their applicability across different domains. SAM by Meta AI has gained attention for its impressive zero-shot performance and capability to produce high-quality object masks from diverse input prompts. The primary advantage of SAM compared to other state-of-the-art segmentation models lies in its ability to generalize across a wide range of tasks without task-specific fine-tuning. This adaptability makes SAM a versatile tool, especially when high accuracy is needed across diverse datasets. However, the specific visual examples in the figure might not fully convey this strength, and we will consider adding more representative images to better illustrate SAM’s capabilities. SAM functions as a class-agnostic segmentation model, utilizing a Vision Transformer (ViT) for image encoding and a sophisticated two-layer mask decoder. SAM’s architecture features an image encoder with ViT to extract detailed embeddings, a prompt encoder to interpret various user inputs, and a lightweight mask decoder for precise pixel-level segmentation decisions. This design enables SAM to effectively adapt to new segmentation tasks with minimal additional training, ensuring high accuracy.

The architecture of SAM, as shown in

Figure 6, primarily consists of three components: the image encoder (Vision Transformer (ViT)), the prompt encoder, and the mask decoder. The SAM utilizes the ViT as the image encoder, serving as the backbone network for image feature extraction. The choice of ViT architecture stems from its ability to capture long-range dependencies and intricate visual information. The prompt encoder processes user inputs (e.g., boxes) to guide the segmentation process. Specifically, it is based on box encoding, where user-drawn bounding boxes were encoded to provide spatial constraints for segmentation. The mask decoder integrates features from both the ViT backbone and the prompt encoder to generate segmentation masks. The decoder comprises: feature fusion, upsampling layers, and mask generation.

The pre-training process of SAM occurs on a large-scale and diverse dataset (SA-1B dataset), which comprises over a billion finely annotated images and segmentation masks covering various image types and segmentation tasks. The pretraining process adopts a multitask learning strategy, combining Cross-Entropy loss and Dice loss to optimize segmentation accuracy. The objective of pretraining was to enable SAM to learn rich feature representations, allowing it to generalize to different segmentation tasks and application scenarios without the need for retraining. However, the conventional SAM does not perform well on pavement distress because pavement distress is thin and irregular, unlike the natural images that the SAM was trained on. Therefore, SAM is finetuned with the bounding box prompt to create a pavement distress-specific segmentation model, called modified SAM. To reduce the computational cost, the image encoder is frozen, while only the prompt encoder and the mask decoder are fine-tuned for pavement distress segmentation. Masks are generated for top-down pavement images using polygon-based annotations on LabelMe. The model was trained for 200 epochs. The loss was the summation of the dice loss and the cross-entropy loss, which together provide a robust loss for segmentation tasks. Adam optimizer was used with different learning rates.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Preparation

MPWT has recently introduced the ROMDAS for road network assessment. However, due to limited server capacity and the lack of dedicated software tools for image-based analysis, high-resolution pavement images captured by ROMDAS are generally retained only for a short period before being deleted. In contrast, conventional outputs such as the International Roughness Index (IRI), Rut Depth, and Mean Profile Depth (MPD), which require far less storage space, are systematically preserved. Moreover, the ROMDAS pavement image available from a small number of survey routes in Cambodia does not provide sufficient coverage of surface distress for comprehensive analysis.

To address these limitations, a synthetic dataset was created that emulates the characteristics of ROMDAS imagery. Specifically, pavement surface regions were cropped from Cambodian ROMDAS survey images while retaining the blue header that contains embedded coordinate information. These cropped regions were then replaced with pavement surface images captured in Yamanashi, Japan, using an action camera [

54]. This strategy ensured that the resulting dataset maintained the perspective and visual style of ROMDAS data while expanding the availability of distress cases required for training and validation. Nonetheless, as this synthesis primarily demonstrates the feasibility of the proposed framework, variations in pavement texture, illumination, and imaging conditions between two sources may influence the model’s generalization to purely local datasets. Therefore, retraining or fine-tuning with larger, fully local datasets is recommended for practical deployment.

In total, 1260 images were prepared for model development and randomly divided into two subsets: 80% for training and 20% for validation. Additionally, a separate set of 700 unseen images was used for independent testing to assess model generalization performance. The dataset was annotated into three primary categories of cracks (transverse, longitudinal, and pattern cracks), using the LabelMe tool. Polygonal annotations were subsequently converted into binary ground truth masks to facilitate segmentation tasks.

3.2. Model

The proposed framework integrates two models: YOLOv8 for crack detection and SAM for segmentation. YOLOv8 was chosen for its simplified training and deployment through the Ultralytics library and for its anchor-free detection mechanisms, which allow faster inference without compromising accuracy. The YOLOv8n variant, in particular, was selected due to its lightweight architecture, making it suitable for deployment on limited hardware. As reported by Li and Gu [

55], comparative experiments were conducted using multiple YOLOv8 versions (YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv8l, and YOLOv8x) for road crack detection. Their results showed that YOLOv8n achieved competitive accuracy with significantly lower inference time and reduced hardware requirements compared with the larger models; therefore, it was selected as the baseline in their study and further modified to improve accuracy and efficiency. Despite its compact design, YOLOv8n achieves higher accuracy than comparable lightweight models such as MobileNet-SSD, which rely on older CNN backbones. Furthermore, YOLOv8 supports deployment formats like TensorRT, enabling performance optimization on embedded NVIDIA Jetson platforms and ensuring stable operation in continuous field environments.

For segmentation, SAM was incorporated to generate fine-grained crack masks from bounding box prompts. SAM is a transformer-based vision model designed for general-purpose segmentation, and in this study, its ViT-H backbone was fine-tuned using a transfer learning strategy. The image encoder and prompt encoder were frozen to preserve SAM’s feature extraction capability, while the mask decoder was optimized for pavement crack imagery. To improve the accuracy of segmenting thin and irregular crack structures, a hybrid loss function combining Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss and Dice loss was employed. In addition, to refine segmentation quality when bounding box prompts were overly broad, a simpler local refinement, crop-and-refine, was adopted in the test dataset to work on image patches [

56,

57]. This refinement module crops local regions in the bounding boxes, performs localized corrections based on error maps, and then reinserts the refined patches into the global region.

3.3. Training Setup

All experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 operating system with PyCharm as the development environment. To ensure reproducibility, the code and experimental configurations used for both training and testing are publicly accessible on GitHub at

https://github.com/Nut-Sovanneth/YOLOv8-SAM-OCR.git (accessed on 11 November 2025). Model training and validation were performed on a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti GPU. The optimizer was set to automatic selection, enabling adaptive tuning of optimization parameters during training. Parameters quantify the learnable elements within a model, reflecting the complexity and capacity of the model. The detailed configurations pertaining to the hyperparameters for network training are outlined in

Table 1.

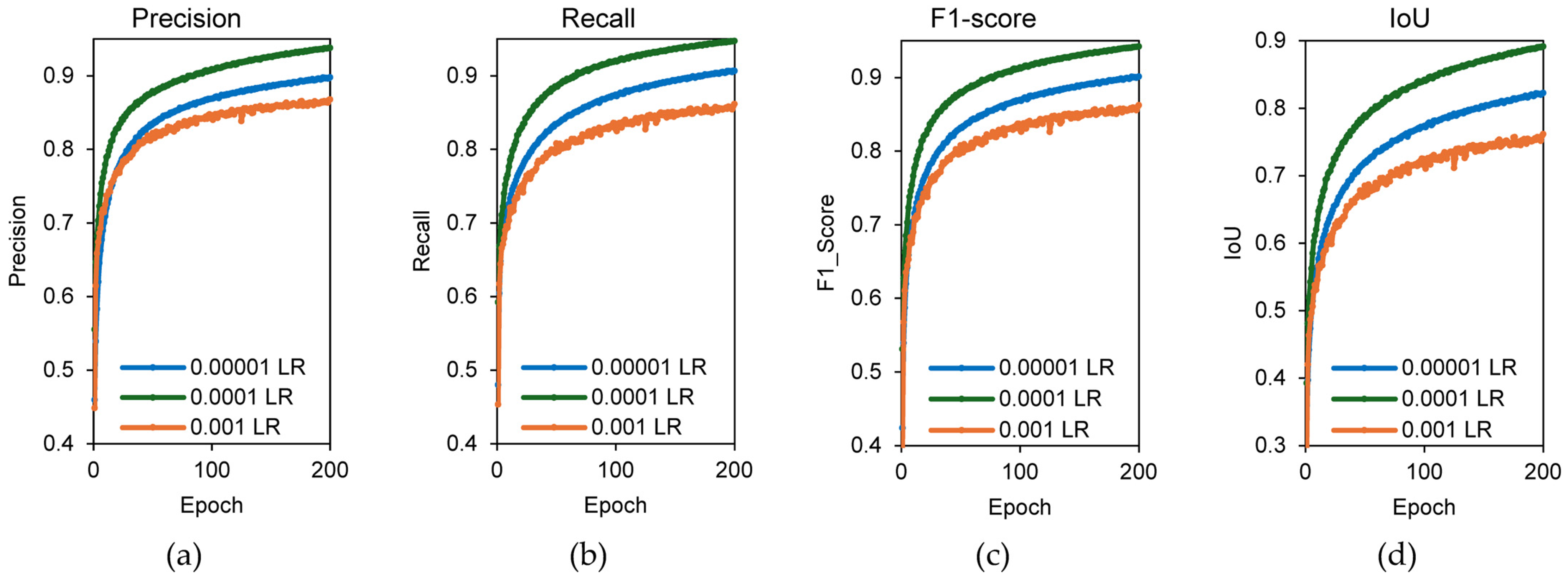

YOLOv8 was trained for 200 epochs with an input size of 640 × 640 pixels and a batch size of eight, using pretrained weights (YOLOv8n.pt). SAM was fine-tuned for 200 epochs with a batch size of one image, an input size of 1024 × 1024 pixels, and pretrained weights (sam_vit_h_4b8939.pth). For YOLOv8, the initial learning rate was set to 0.01 and gradually decreased to near zero following a cosine schedule, where an initial warm-up phase enables stable early training and the non-linear decay shows the reduction toward the end of the process. For SAM, learning rates of 0.001, 0.0001, and 0.00001 were evaluated based on sensitivity analyses to balance training stability, convergence speed, and computational efficiency, ensuring optimal mask segmentation performance while maintaining feasible resource usage. Both models were trained on the same three classes of cracks: transverse, longitudinal, and pattern cracks.

Hyperparameters such as image size, batch size, and learning rate were carefully selected based on sensitivity analyses to balance training stability, convergence speed, and computational efficiency.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of the YOLOv8 detection model was evaluated using precision, recall, and mean average precision (

mAP). Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified cracks among all positive predictions, while recall reflects the proportion of actual cracks successfully detected by the model. Average Precision (

AP) corresponds to the area under the precision-recall curve for each crack type. The

mAP at

IoU = 0.5 (

mAP50) quantifies performance when a 50% overlap is required between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, whereas

mAP50–95 average

AP across thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 in increments of 0.05, providing a more comprehensive measure of detection accuracy. YOLOv8 was optimized using a composite loss function consisting of box regression loss (box_loss), classification loss (cls_loss), and distribution focal loss (dfl_loss), which together improved bounding box localization, crack classification, and boundary refinement. These evaluation metrics can be calculated as follows:

Here, TP (true positives) refers to correctly detected cracks, FP (false positives) represents background regions incorrectly identified as cracks, and FN (false negatives) denotes missed cracks. N represents the number of crack classes (e.g., transverse, longitudinal, and pattern cracks).

During the YOLOv8 training, key evaluation metrics, including

Precision,

Recall,

mAP50, and

mAP50–95, were monitored at each epoch, as shown in

Figure 7. All metrics exhibited a gradual improvement with increasing iterations. By the end of training,

Precision,

Recall,

mAP50, and

mAP50–95 reached 0.704, 0.694, 0.733, and 0.468, respectively, indicating that YOLOv8 achieves strong performance in detecting pavement cracks.

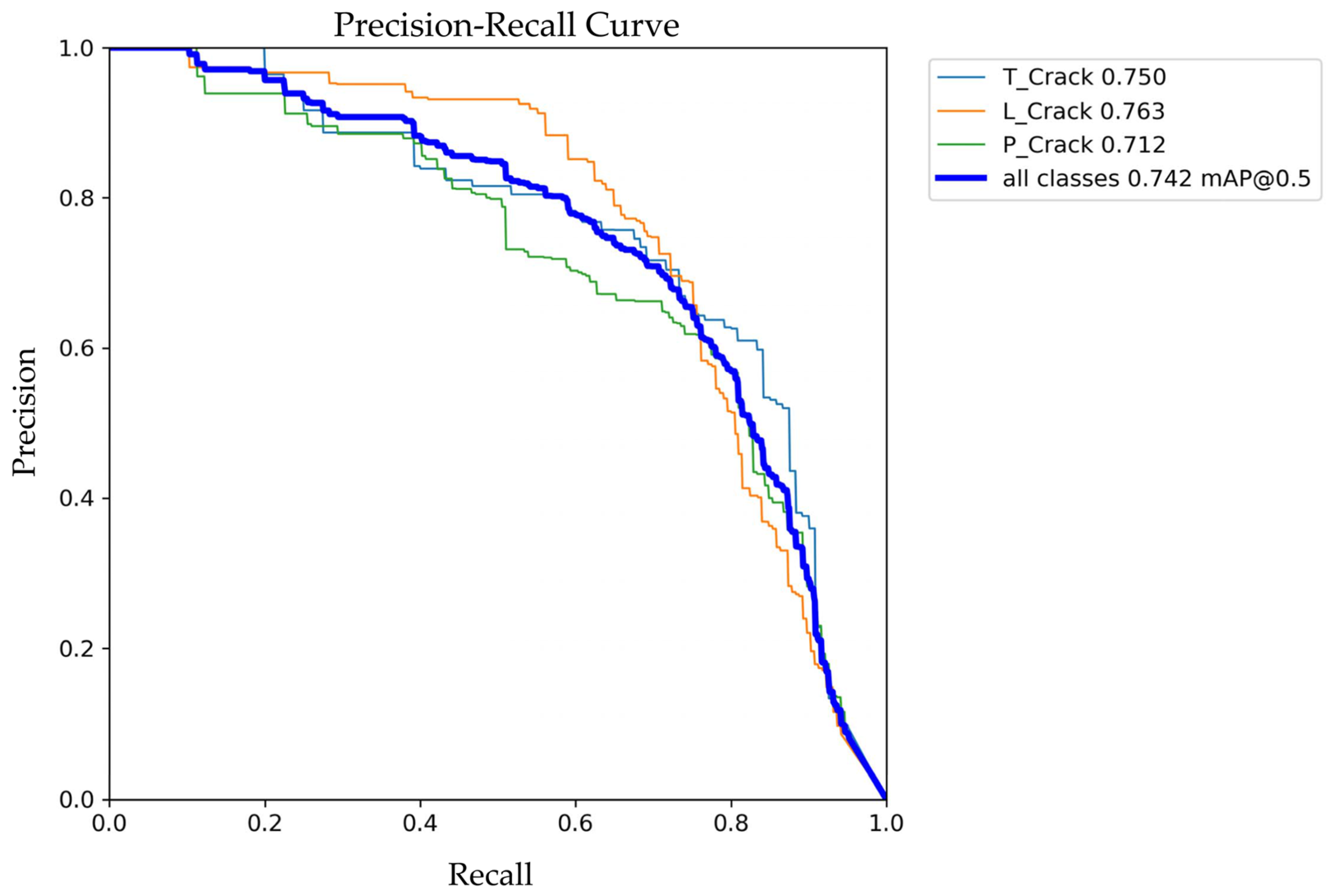

Figure 8 illustrates the Precision-Recall curves for YOLOv8. The horizontal axis represents

Recall, and the vertical axis corresponds to

Precision.

Figure 8 also reports the

AP values for each crack class as well as the

mAP across all classes. Specifically, the areas under the curves for transverse crack, longitudinal crack, and pattern crack are 0.75, 0.763, and 0.712, respectively, demonstrating that YOLOv8 effectively identifies different types of pavement cracks.

The performance of SAM was evaluated using

Precision,

Recall,

F1

-score, and Intersection over Union (

IoU). The

F1

-score, defined as the harmonic mean of

Precision and

Recall, offers a balanced indicator of segmentation accuracy and robustness, especially in the case of imbalanced datasets. IoU quantifies the geometric overlap between predicted (

) and ground truth labels (

), thereby evaluating the fidelity of predicted crack boundaries.

For the SAM training process, metrics such as

Precision,

Recall,

F1

-score, and

IoU were tracked over the same 200 epochs using three distinct learning rates: 0.001, 0.0001, and 0.00001. As depicted in

Figure 9, all metrics improved progressively as the number of iterations increased. Among the tested learning rates, 0.0001 yielded the best performance, with

Precision,

Recall,

F1

-score, and

IoU values of 0.938, 0.947, 0.942, and 0.891, respectively, suggesting that this configuration allowed the model to capture crack features more accurately than the other learning rates. Although full convergence was not reached within the 200 epochs, the attained

F1

-score of 0.942 demonstrates robust segmentation performance, as values above 0.9 are widely regarded as indicative of highly accurate prediction, whereas scores below 0.5 typically reflect substantial misclassification [

44]. The implication is that while marginal gains might be realized with extended training, the current performance is operationally sufficient and robust for the application domain.

To assess practical deployment feasibility, we measured model size, computational complexity, and inference performance. The YOLOv8-based detector contains 3.01 million parameters and requires 8.2 GSLOPs per 640 × 640 input image, achieving an average inference time of 3.65 ms per image, corresponding to 274 FPS. On the other hand, the fine-tuned SAM with ViT-H backbone contains 631.6 million parameters and requires 2733.6 GFLOPs for 1024 × 1024 inputs, with an inference time of 431.7 ms per image, corresponding to 2.32 FPS.

For each connected component within the coarse segmented mask, an expanded region of interest (ROI) was extracted from the original input image using direct array slicing. This hard-crop operation supplies the refinement process with a high-resolution contextual pixel centered on the target component, without any interpolation artifacts. The SAM is then applied to the isolated patch, using a translated bounding-box prompt, to produce a high-fidelity local segmentation. The refined-level masks are subsequently mapped back into global coordinates and composited into the final output mask. This local refinement procedure improves boundary precision and detail while maintaining consistency across the entire image domain. The inference results on unseen images from the combined YOLOv8 and SAM framework are visualized in

Figure 10, where transverse, longitudinal, and pattern cracks are indicated by blue, green, and red bounding boxes and masks, respectively.

Upon completion of the two-stage process, the segmented mask can be quantified by counting the pixels, allowing computation of distress density, as described in [

58]. Simultaneously, a region containing pixel-level coordinates is extracted using Tesseract OCR to enable geospatial mapping of the detected and segmented distress, as illustrated in

Figure 11. The OCR reliably recognizes the coordinate digits at the pixel level, producing digital values that accurately correspond to the road alignment when imported into a GIS.

4. Discussion

The cornerstone of the proposed framework lies in the integration of efficient pavement crack detection using YOLOv8n and high-fidelity segmentation using SAM. The choice of the lightweight YOLOv8n model as the baseline detector was deliberate, prioritizing an optimal balance between computational efficiency and detection efficacy. The results presented in the previous section demonstrate that YOLOv8n achieves satisfactory performance given its compact size and high inference speed. This efficiency is particularly critical for large-scale deployment by road agencies.

However, pavement distress datasets inherently pose challenges such as thin cracks or complex pavement textures, which can lead to false positives, missed detections, and reduced accuracy in the baseline YOLOv8n. To address these limitations, potential improvements could involve modifications to the backbone and neck structures to strengthen feature extraction and multi-scale representation. Such architectural refinements would enable the model to better capture fine-grained crack details more effectively, minimize redundant computation, and enhance localization accuracy across varying spatial scales.

For the segmentation task, the SAM component delivered exceptional results following fine-tuning. This high fidelity in mask generation is essential for accurate quantification of crack severity, which underpins efficient maintenance planning. Two complementary loss functions, including BCE and Dice loss, were employed during training. BCE promotes precise pixel-level classification, while Dice loss enhances overlap quality between predicted and ground-truth masks. This hybrid objective facilitates robust boundary delineation and improves the model’s ability to generalize across diverse crack morphologies. The fine-tuned SAM’s mask decoder, optimized under this combined loss, effectively captured both global structure and local boundary details.

As summarized in

Table 2, a comparative evaluation on the Crack500 dataset demonstrated that the proposed SAM notably outperformed several state-of-the-art segmentation frameworks. In particular, the SAM attains the highest

IoU of 76.69%, demonstrating its strong capability in accurately delineating crack regions. Although its

Precision (79.07%) and

F1

-score (79.62%) are marginally lower than those of W-segnet, which achieved 79.86% and 80.70%, respectively, the SAM maintains highly competitive results across these metrics. Furthermore, its

Recall (80.53%) is comparable to that of W-segnet (81.56%) and the modified DeepLabv3+ (80.00%) and remains close to the top-performing DeepCrack (89.82%). These findings confirm that fine-tuning SAM with appropriate loss functions and learning configurations significantly enhances segmentation accuracy for pavement crack analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a novel, integrated framework for end-to-end pavement crack detection and segmentation. The proposed methodology leverages the YOLOv8 model for efficient crack detection and a modified Segmentation Anything Model (SAM) for high-precision, pixel-level segmentation. This two-step approach addresses the significant challenge of high labeling costs by utilizing bounding box prompts from the detection phase to guide the segmentation process.

The framework’s effectiveness was validated using a real-world, open-source dataset from Yamanashi, Japan. The YOLOv8-based detection model demonstrated robust performance with a Precision of 0.704, a Recall of 0.694, and mean Average Precision (mAP) scores of 0.733 (at an IoU of 0.5) and 0.468 (averaged from 0.5 to 0.95). These metrics confirm the model’s capacity for crack detection on smart road-measuring devices with minimal computational requirements.

A key contribution of this research is the integration of SAM, which offers significant advantages in reducing annotation burdens. Unlike traditional segmentation models that are limited to pre-trained classes and require extensive annotated datasets, our modified SAM approach enables zero-shot segmentation. This allows the model to accurately delineate crack boundaries on new, unseen images without the need for additional training, a capability that no current segmentation model offers for this application. The segmentation results, with a Precision of 0.938, a Recall of 0.947, an F1-score of 0.942, and an IoU of 0.891, underscore the model’s precision in identifying the exact pixels that constitute a crack.

To further illustrate the performance of the proposed framework, a comparative evaluation was conducted on the Crack500 dataset. The SAM-based approach achieved the highest IoU of 76.69%, indicating superior ability in delineating crack regions. While its Precision (79.07%) and F1-score (79.62%) are slightly lower than W-segnet, the SAM remains highly competitive. Its Recall (80.53%) is comparable to other leading methods, such as W-segnet and DeepLabv3+, and approaches the performance of DeepCrack.

Furthermore, the framework integrates Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to automatically extract geospatial coordinates, enabling the automated mapping of detected distress onto real-world road networks. This end-to-end solution provides a quantitative assessment of distress, including its type, severity, and extent, which is essential for calculating the Maintenance Control Index (MCI) and facilitating efficient maintenance planning for road agencies.

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of the proposed framework, several challenges remain. For instance, some cracks obscured by shadows exhibit reduced identifiability, as illustrated in

Figure 10. Environmental factors, including uneven lighting and motion blur caused by vehicle movement, can adversely affect model accuracy. Moreover, the complexity of real-world road scenes, such as the presence of debris or irregular pavement textures, may result in missed detections or incomplete segmentations, even when detection is successful. Future work will aim to enhance the model’s robustness by refining the YOLO and SAM architecture with advanced attention mechanisms to better handle complex and noisy environments, as well as by improving the local refinement strategy, for example, through the incorporation of techniques such as RoIAlign.