Abstract

This review elucidates the foundational principles of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) homeostasis in humans, emphasizing its depletion during aging and in age-associated disorders. Subsequently, the discussion extends to NAD+ precursors and their potential therapeutic applications, with insights from research using zebrafish as a disease model. This information sheds light on the growing interest in NAD and its metabolism in the medical field and sparks curiosity among researchers focused on fish studies. The review further explores the role of nicotinamide in fish, encompassing core NAD+ metabolism, its participation in oxidative stress, environmental challenges, and the mitigation of pollutant-induced toxicity. Additionally, the implications of NAD+ in fish neurobiology, immune regulation, host–pathogen interactions, skin, eggs, and post mortem muscle were considered. Dietary modulation of NAD+ pathways to enhance growth, immunity, and product quality in aquaculture has also been highlighted. This review highlights the significance of NAD+ metabolism in fish biology, covering cellular energy production, physiological processes, and environmental adaptation, and proposes targeting NAD+-related pathways as a strategy for aquaculture and fish health management.

Key Contribution:

This review highlights the importance of nicotinamide in central NAD+ metabolism, which is essential for energy production and physiological function in fish. It emphasizes the role of NAD+ in nutrition, stress response, immune regulation, and neurobiology, and its potential to reduce the negative impacts of environmental pollutants and enhance fish quality. This study suggests that targeting NAD+ pathways may improve fish health and productivity in aquaculture.

1. Introduction

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) was initially identified as a cofactor in yeast fermentation in 1906, originally termed ‘cozymase’. Its structure, consisting of adenine, phosphate, and a reducing sugar, was elucidated in the 1930s, and its function as a hydride transfer agent was clarified in 1936. NAD+ research was conducted using the three Nobel Prizes. Interest in NAD+ significantly increased in the early 2000s following its identification as a co-substrate for sirtuins (SIRTs), which are essential for regulating longevity and metabolism. NAD+ and NADH are indispensable for electron exchange reactions, particularly those mediated by oxidoreductases, which involve hydride transfer. NAD+ functions as an electron acceptor, whereas NADH serves as an electron donor and plays a vital role in catabolic pathways, such as glycolysis, fatty acid β-oxidation, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Currently, there is renewed scientific interest in NAD+, owing to its recently discovered role in regulating metabolism and longevity in humans [1]. This article presents a narrative review delineating the fundamental concepts of NAD+ homeostasis in humans. It subsequently examines evidence implicating NAD+ depletion during the aging process and various age-related disorders. This body of knowledge has prompted investigations into NAD+ precursors, their potential therapeutic value, and the effects of NAD+ in disease models using zebrafish. Finally, this review discusses the current state of research concerning studies conducted on fish, elucidating the relationships between NAD+ and related molecules and their most significant functions in these animals. The primary aim was to elucidate the fundamental concepts, evaluate various NAD+ boosters in aquafeeds and their bioavailability, perform comparative analyses to determine potential requirements for each fish species, and investigate optimal outcomes for the aquaculture industry.

2. Overview of NAD+ Biology and Its Balance in Human Health and Disease

The subcellular distribution of NAD+ and its biosynthetic enzymes varies across the cellular compartments. The nucleo-cytosolic NAD+ pool is considered to be interchangeable between cytosolic and nuclear pools, with similar concentrations in both [2]. The mitochondrial NAD+ pool, traditionally thought to be separated from the nucleo-cytosolic pool, may involve an unidentified mammalian mitochondrial NAD+ transporter [3]. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferase (NMNAT) is a non-histone chromatin-associated protein with distinct properties. NMNAT is distributed in the nucleus with specific binding affinities different from those of histones, suggesting its role in chromatin structure and nuclear processes, such as DNA repair [4]. Different NMNAT isoforms have distinct locations: NMNAT1 in the nucleus, NMNAT2 in the cytosol and Golgi, and NMNAT3 in mitochondria [5]. Consequently, variations in the subcellular distribution of NAD+ across tissues with distinct metabolic functions and requirements may be substantial. The allocation of NAD+ and its biosynthetic components within cellular compartments facilitates the regulation of NAD+-dependent processes in various cellular regions and tissues [1].

NAD can be synthesized via de novo and salvage pathways. De novo NAD+ synthesis occurs in the cytosol, where all enzymes are localized [2]. De novo synthesis begins with dietary tryptophan (Trp), whereas salvage pathways use vitamin B3 compounds like nicotinic acid (NA), nicotinamide (NAM), and nicotinamide riboside (NR) from the diet for NAD production. Both pathways could benefit aquaculture because fish diets can be supplemented to enhance NAD synthesis; however, these studies are still in their infancy. A review showed that the NAMPT-driven NAD+ salvage pathway supports muscle health by maintaining mitochondrial function, reducing oxidative stress, and promoting autophagy, muscle stem cell function, and neuromuscular junction integrity in aging and diseases [6]. These factors demonstrate the importance of NAD+ metabolism regulation through salvage pathway activation in combating metabolic, mitochondrial, neurotoxic, and muscle aging dysfunctions [6].

The main signaling pathways that consume NAD+ include SIRTs, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), and cyclic ADP-ribose synthases (cADPRSs). SIRTs are conserved NAD+-dependent deacetylases; therefore, their functions are intrinsically linked to cellular metabolism [7]. Localization varies across cellular compartments, potentially enabling compartment-specific regulation of NAD+ pools [8]. PARPs consume NAD+ and are involved in DNA repair and other cellular functions, whereas cADPRSs, specifically, CD38, are examples of enzymes that cleave NAD+ to generate secondary messengers involved in calcium signaling. These enzymes share the common property of irreversibly cleaving NAD+ into NAM and ADP-ribose moieties. They act as metabolic sensors and significantly influence organ metabolism, function, and aging [9].

Energy status influences NAD+ homeostasis in cells and organisms. Limited energy availability through caloric restriction, fasting, and exercise elevates NAD+ levels, while excessive energy consumption via high-fat or high-fat/sucrose diets depletes NAD+ in metabolic organs [10]. Circadian rhythms affect NAD+ levels and exhibit diurnal fluctuations in the liver. The circadian clock regulates NAD+ biosynthetic enzymes (e.g., NAMPT), whereas NAD+ consumers such as PARP-1, SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT3 regulate the circadian clock [11]. NAD+ levels oscillate circadianly through rhythmic expression of biosynthetic enzymes like NAMPT, while sirtuins (SIRT1, SIRT6) regulate clock components and circadian metabolic genes. Therapeutic approaches using chronopharmacology, NAD+ boosters, and SIRT modulators can restore circadian synchronization and improve age-related pathologies via the NAD+–sirtuin–clock network [12].

Strategies to enhance NAD+ synthesis include supplementation with NAD+ precursors (e.g., NAM, NA, NR, and NMN), stimulation of NAD+ synthesis enzymes (such as NAMPT), and activation of NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [13,14]. To prevent NAD+ depletion, it is also possible to inhibit enzymes that consume NAD+ (e.g., SIRTs, PARP-1, and CD38) [15]. Additionally, the regulation of metabolic pathways is crucial, as it can divert metabolites from NAD+ production, and their inhibition may result in elevated NAD+ levels. Enzymes like nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT) facilitate NAM methylation using S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor, producing 1-methylnicotinamide (MNAM) and S-adenosylhomocysteine [16]. Understanding these factors is crucial for formulating strategies to sustain NAD+ levels, which may be beneficial in age-related and metabolic diseases.

2.1. Reduction in NAD+ Levels Is Associated with Aging and Numerous Age-Related Diseases

NAD+ depletion is associated with aging and age-related disorders. Research in mammals shows that DNA damage from aberrant nutrition increases cellular NAD+ consumption. Lower NAD+ levels lead to oxidative stress and contribute to metabolic diseases [17]. NAD+ depletion is linked to neurodegenerative disorders (including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and prion diseases), all of which are characterized by protein misfolding and proteotoxic stress [18]. In addition, alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases are also associated with decreased NAD+ levels, as well as different cardiovascular diseases (including cardiac ischemia, cardiomyopathies, and cardiac hypertrophy) [19] and muscular disorders (e.g., muscular dystrophies, mitochondrial myopathies, and age-related sarcopenia). Enhanced NAD+ levels show promise in preserving muscle function in animal models [20] and kidney disorders, characterized by impaired mitochondrial function and reduced SIRT signaling [21]. In addition, maintenance of hepatic NAD+ content has shown protective effects against hepatic lipid accumulation and liver damage in various animal models [10]. Metabolic disorders like obesity and type 2 diabetes are associated with altered NAD+ homeostasis in tissues. Restoring NAD+ levels enhances mitochondrial function and shows protection in animal models, offering a promising therapeutic approach [10].

2.2. Potential Therapeutic Value of NAD+ Precursors

Owing to their significant bioactivity, directly supplying animals with exogenous NAD+ is challenging [17,22]. Vitamin B3 (NA and NAM) and derivatives like NR and NMN are NAD+ precursor vitamins [23,24]. The administration of NAD+ donors can elevate NAD+ concentrations within cells, thereby ameliorating metabolic dysfunction. Research shows these NAD+ precursors have distinct effects due to their unique properties in enhancing NAD+ levels in mammalian cells [17,25]. For instance, oral administration of NR enhances hepatic NAD+ levels in mice more effectively than NA or NAM [26]. A review has evaluated NMN and NR as NAD+-boosting precursors. Both compounds increase NAD+ levels and benefit aging- and metabolism-related health. Studies suggest NR may increase NAD+ more efficiently, as NMN needs conversion to NR before cellular uptake. Animal studies also show NMN has superior effects in specific contexts [27]. These findings indicate NAD+ enhancement’s potential advantages for age-related and metabolic disorders in humans. Although preclinical research shows promise, clinical evidence remains early [27]. Most human studies conducted to date have been short-term, spanning weeks to months. There is a notable lack of data regarding long-term NAD+ supplementation in humans. Consequently, further research involving long-term clinical trials with larger cohorts is necessary to fully comprehend the therapeutic potential of NAD+ [1,28]. Studies have shown that NAD+ precursors such as NR are well tolerated by humans over short periods [29]. Research indicates that the effects of NAD+ supplementation vary, with individual differences influenced by factors such as age, health status, and metabolic conditions. Therefore, caution must be exercised in this context. Clinical trials are essential for assessing the effects and risks of NAD+ supplementation in humans. Further research is needed to identify adverse effects and confirm long-term supplementation safety. These considerations highlight the importance of trials in mitigating risks of unregulated NAD+ boosters [1].

Promising results from NAD+ supplementation suggest its potential application in oncology and anti-aging therapies. A hopeful treatment strategy demonstrates NR’s effectiveness alongside other components while maintaining radiotherapy efficacy in tumor xenograft models. Combined treatment with polyphenols, pterostilbene, silibinin, NR, and TLR2/6 ligand (FSL-1) provided radioprotection in mice exposed to lethal γ-radiation. While polyphenols alone enabled 30-day survival, the complete combination provided 90% survival at one year post-irradiation. Protection mechanisms involve Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses, DNA repair through PARP1, NF-κB inflammation suppression, mitochondrial stabilization via PGC-1α/SIRT1/SIRT3, and accelerated hematopoietic recovery [30]. However, the geroscience hypothesis posits that addressing the core elements of aging could prevent age-related diseases and prolong healthy life. Research has explored interventions including senolytics, NAD+ enhancers, and metformin. NAD+ enhancement using NMN and NR precursors increases the health span of model organisms, although human results vary [31]. Clinical trials in older adults and obese individuals show its safety and improvements in insulin sensitivity and aerobic capacity. While NMN and NR are promising NAD+ precursors, NR shows high bioavailability [32]. Current research has indicated that these agents have the potential to improve health. Nevertheless, further studies are required to conduct clinical comparisons and ascertain optimal dosages, benefits, and safety profiles.

3. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Models for Exploring NAD+-Related Pathways in Humans

Given the conservation of metabolic pathways across animal species, research on lower animals provides insights into human metabolic diseases [33]. Studies have shown similar pathophysiological pathways in metabolic diseases in mammalian and fish models [34,35,36]. In addition, fish are reliable and cost-effective experimental alternatives to mammals [37,38]. Therefore, the function of NAD+ in disease models has been extensively investigated using zebrafish as a model organism. This review chronologically presents available studies and their principal findings, showing the progress of research in this field.

Nrk2b, a nicotinamide riboside kinase in zebrafish muscle, is essential for muscle morphogenesis by regulating NAD+-dependent cell–matrix adhesion at the myotendinous junction (MTJ). Nrk2b-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis enables laminin polymerization. In Nrk2b-deficient embryos, muscle fibers extend beyond the somite boundaries. NAD+ rescues MTJ morphology in Nrk2b morphants but not in laminin mutants. Both Nrk2b and laminin control paxillin localization to adhesion complexes. Paxillin overexpression restores MTJ integrity in Nrk2b-deficient embryos, revealing an essential Nrk2b → NAD+ → laminin adhesion → paxillin localization pathway for muscle boundary formation [39]. Increasing NAD+ levels via supplementation or Nrk2b-mediated biosynthesis improves muscular dystrophy in zebrafish lacking laminin-binding complexes. Boosting NAD+ restores basement membrane organization through laminin polymerization, improving locomotor performance. Paxillin overexpression partially rescued muscle structure but not motility. An Nrk2b → NAD+ → laminin → integrin α6/paxillin pathway enhances muscle-ECM resilience, suggesting potential therapy for muscular dystrophy [40]. NAD+ supplementation improved muscular dystrophy pathology in zebrafish with Duchenne muscular dystrophy by restoring NAD+ homeostasis. The study linked muscle damage to NAD+ depletion, which impaired mitochondrial function and SIRT1-mediated responses. NAD+ administration enhanced SIRT1 activation and muscle membrane stability, identifying NAD+ biosynthesis as a therapeutic target for DMD through metabolic–epigenetic crosstalk [41].

Numerous studies have focused on mitigating the adverse effects associated with various diseases through the restoration of NAD+ levels using different methodologies. Resveratrol reduces hepatic lipid accumulation and improves lipid profiles by upregulating fatty acid oxidation genes. SIRT1 activation enhances mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity through the NAD+–sirtuin pathway. Resveratrol counteracts diet-induced dysregulation of lipid metabolism in zebrafish via NAD+-dependent SIRT1 signaling [42]. Chronic ethanol exposure induces hepatic steatosis and inflammation in zebrafish, similar to alcoholic liver disease in mammals. Ethanol treatment caused lipid accumulation and increased inflammatory markers, indicating liver injury. These effects correlate with ethanol-induced suppression of NAD+-dependent SIRT1 activity, which regulates metabolism and inflammation. Zebrafish thus serve as a model for studying alcoholic liver disease and NAD+-targeting therapies [43]. Adult zebrafish exposed to 0.5% ethanol showed elevated serum ALT levels at 48–72 h, with increased hepatic pro-inflammatory and lipogenic gene expression, indicating liver injury. Drug trials showed nicotinamide riboside TES1025 (an inhibitor of amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase in the tryptophan–kynurenine–NAD+ pathway) and riboflavin suppressed ethanol-induced ALT elevation. The model revealed mechanisms including oxidative stress via ROS, NF-κB-mediated inflammation, and steatosis, while ethanol metabolism impairs antioxidant defenses. N-acetylcysteine and silymarin attenuated injury by suppressing ROS/NF-κB and restoring AMPK-mediated lipid metabolism, validating adult zebrafish as a platform for testing hepatoprotective agents against ethanol toxicity [44].

NAMPT, the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD+ salvage, drives PARP1 hyperactivation and cell death, promoting inflammation in zebrafish and human skin models. Inhibition of NAMPT, PARP1, and NADPH oxidases reduced oxidative stress and cell death. NAD+ supplementation reversed these protective effects, confirming NAMPT-NAD+’s role in inflammatory pathology. Elevated NAMPT and PARP1 activities with AIM1 nuclear translocation in psoriatic skin highlight this pathway as a therapeutic target [45].

Propionate induces intestinal oxidative stress in zebrafish through NAD+-dependent SIRT3-regulated propionylation of mitochondrial SOD2. Propionate exposure causes metabolic dysregulation via impaired NAD+/SIRT3 signaling, leading to SOD2 hyperpropionylation and inactivation, revealing how propionate induces oxidative stress despite benefiting gut health [46]. A dietary formulation of NMN with astaxanthin and blood orange extract (NOA) was studied in aging zebrafish. NOA showed superior NAD+ bioavailability in vivo. Treated fish demonstrated reduced aging, enhanced activity, improved sleep, better skin health, and increased ATP synthesis, indicating NOA’s anti-aging benefits [47]. Further research is required to elucidate the established connections between microbial metabolites, post-translational modifications, and redox homeostasis in vertebrates.

Exposure of zebrafish larvae to decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE) induces insulin resistance, lipid accumulation, and neurotoxicity through acetylcholinesterase inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction, reducing oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production. NR reversed these effects [48]. Aspartame causes developmental defects in zebrafish embryos by disrupting NAD+-dependent SIRT1/FOXO3a signaling, reducing NAD+ levels, and causing neuronal apoptosis. These findings showed the NAD+/SIRT1/FOXO3a pathway’s role in neurodevelopment and demonstrated how artificial sweeteners affect development, suggesting NAD+ homeostasis may mitigate aspartame-induced neurotoxicity [49]. Recently, a zebrafish model was established for Congenital NAD+ deficiency disorders (CNDD), showing developmental anomalies similar to human CNDD and vertebral–anal–cardiac–tracheoesophageal fistula–renal–limb (VACTERL) association syndrome. 2-amino-1,3,4 thiadiazole (ATDA)-induced neural tube defects, craniofacial malformations, and cardiac abnormalities were rescued by NAM supplementation, confirming the role of NAD+ depletion. These results demonstrated that zebrafish are useful for studying NAD+-dependent malformations and investigating CNDD and VACTERL phenotypes in vivo [50].

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), used in Gore-Tex and Teflon manufacturing, causes premature ovarian insufficiency in female zebrafish, reducing spawning and increasing embryo mortality. PFOA suppresses NAD+ biosynthesis and impairs mitochondrial integrity in oocytes, with NMN supplementation alleviating reproductive defects by restoring NAD+ levels. These findings suggest NMN as a potential therapeutic for chemical disorders in zebrafish gonads [51]. Another work on the PRPS1 variant in X-linked hearing loss revealed its connection to NAD+ homeostasis. PRPS1 catalyzes purine nucleotide synthesis for the NAD+ salvage pathway, with its Ser115Gly variant impairing GTP/ATP production, potentially disrupting NAD+ levels and NAD+-dependent processes [52].

Other studies have also focused on emulating diseases affecting the nervous system. NR significantly prolonged survival and improved motor function in a zebrafish model of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced Parkinson’s disease. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses revealed that NR exerts neuroprotective effects by downregulating gluconeogenic enzymes and upregulating glycolytic enzymes, while attenuating endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, providing mechanistic insights into potential therapeutic approaches for Parkinson’s [53]. Zebrafish models of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1, a serine/threonine kinase that is constitutively expressed and involved in various cellular processes, including innate immunity and autophagy) deficiency showed that TBK1 loss causes motor neuron degeneration and impaired swimming. Metabolomics revealed that TBK1 disruption leads to NAM pathway dysregulation and NAD+ depletion, with NR supplementation rescuing the motor function. Proteomic analysis showed elevated inflammatory markers and necroptosis, the inhibition of which improved survival [54].

These studies highlight the efficacy of zebrafish as a model organism for investigating proposed diseases. Furthermore, they emphasize that a comprehensive understanding of NAD+ metabolism in vertebrates, both generally and in specific species of interest, can enhance our comprehension of prevalent pathologies affecting these organisms. Additionally, it is of interest to explore methods to augment NAD+ reserves, which appear to be consistently depleted or exhausted during these pathological processes.

4. Nicotinamide and Related Metabolites in Fish

This section provides an in-depth analysis of NAD+ metabolism and its complex roles in fish physiology, health, and adaptation to environmental change. These findings highlight the diverse functions of NAD+ and emphasize the crucial importance of its related pathways in various biological processes in fish (Figure 1). The results are systematically organized for clarity, following a chronological order where applicable and transitioning from molecular mechanisms to ecological and industrial applications.

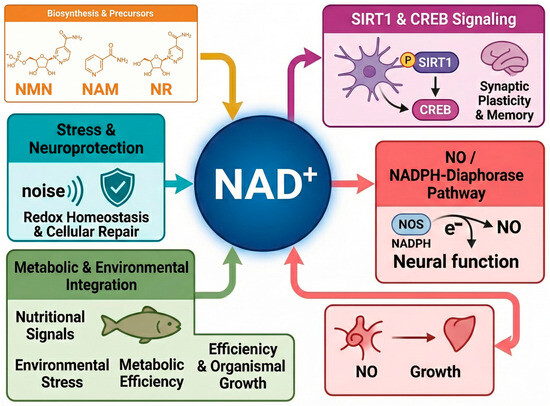

Figure 1.

Schematic representation illustrating the central role of NAD+ metabolism as a key component of a network that links metabolism, neuronal function, and environmental responsiveness in teleosts. NAD+ acts as a critical hub connecting 1. Dietary precursor availability. 2. Regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory through activation of sirtuins (SIRT1) and transcription factors such as CREB. 3. Nitric oxide (NO) synthesis, a key signaling molecule, via the NADPH-diaphorase (NOS) enzyme, relies on NAD+-derived cofactor (NADPH). NO mediates processes such as neurotransmission and vasoregulation. 4. Protective mechanisms against external stressors, such as acoustic stress, maintain redox homeostasis and promote cellular repair. 5. Integration of nutritional and environmental signals to regulate metabolic efficiency and organismal growth.

4.1. Core NAD+ Metabolism in Fish Nutrition

NAD+ is crucial as both a redox cofactor in metabolic processes and a substrate in stress-responsive signaling pathways. Under stress, NAD+ synthesis diminishes while consumption increases, reducing cellular levels. The administration of dietary precursors to enhance biosynthesis has been proposed to counteract physiological decline and prevent pathologies. Consequently, numerous fish studies have investigated these subjects, examining hepatic NAD- and NADP-isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP-ICD) activities in carp (Cyprinus carpio) and tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under various dietary conditions. Fish consuming carbohydrate-rich diets and exhibiting increased feeding rates showed elevated soluble NADP-ICD levels due to enhanced lipogenesis. In contrast, enzymatic activity decreased in fish under starvation or a lipid-rich diet. Notably, mitochondrial NADP-ICD activity remains constant regardless of diet [55].

Numerous studies have focused on NAD+ metabolism from a nutritional perspective, specifically by examining SIRTs and NAMPT. SIRTs are NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases that regulate metabolic pathways in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, involved in cell survival, senescence, proliferation, apoptosis, DNA repair, metabolism, and caloric restriction. The mammalian SIRT family of evolutionarily conserved proteins belonging to class III histone deacetylases (HDACs) comprises seven members [56]. These enzymes have been studied in fish species, including a spatiotemporal examination of SIRT expression patterns during aging in short-lived annual turquoise killifish (Nothobranchius furzeri), a model for aging studies. Results show tissue-specific and age-related regulation of sirtuin isoforms (SIRT1–7), with a reduction in NAD+-dependent sirtuins (SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6) in metabolically active tissues during aging. The link between SIRT downregulation and aging suggests an evolutionarily conserved function of the NAD+-sirtuin axis in vertebrate aging, indicating N. furzeri as an effective model for studying SIRT expression while emphasizing NAD+ bioavailability’s importance for healthy aging [57]. A reliable quantitative PCR (qPCR) reference gene framework has been established for microRNA analysis in Wucham bream (Megalobrama amblycephala), enabling exploration of the miR-34a/Sirt1 regulatory axis in energy metabolism. This study showed that miR-34a targets Sirt1 mRNA, inhibits the NAD+-dependent Sirt1 pathway, and disrupts lipid and glucose homeostasis. Using stable reference genes like 5S rRNA enabled precise quantification of miR-34a upregulation during metabolic stress, showing an inverse correlation with Sirt1 expression. These findings reveal that miR-34a-mediated inhibition of Sirt1 compromises mitochondrial function, highlighting the role of the NAD+/Sirt1 axis in energy regulation. This research enhances miRNA techniques in aquaculture species and the regulation of the SIRT pathway [58].

Epigenetic regulation of muscle Sirt1 expression was explored in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata), revealing how local DNA methylation dynamically influences SIRT1 transcription in response to seasonal changes and aging. Decreased promoter methylation was associated with increased Sirt1 expression during high metabolic demand, whereas age-related hypermethylation leads to transcriptional decline, linking epigenetics to NAD+-dependent metabolic adaptation. These results reveal how environmental cues epigenetically regulate Sirt1 expression for muscle homeostasis, demonstrating a conserved mechanism that integrates epigenetic and SIRT-mediated metabolic control in vertebrates [59]. In the same fish species, an expanded repertoire of SIRT genes includes three Sirt3 copies (sirt3.1a, sirt3.1b, sirt3.2) and two Sirt5 copies (sirt5a, sirt5b), in addition to seven canonical paralogs (SIRT1–7), shaped by vertebrate 2R and teleost-specific 3R duplications. While sirt3.1 and sirt5a are mainly expressed in skeletal muscle, sirt3.2 and sirt5b show higher expression in immune tissues and gills, suggesting tissue-specific adaptation [60]. Similarly, the first comprehensive genome-wide analysis of the Sirt gene family in Nile tilapia revealed the conserved and teleost-specific features of these NAD+-dependent proteins. Seven SIRT orthologs (SIRT1–7) showed distinct tissue expression patterns. Sirt1 and sirt3 are highly expressed in liver and muscle tissues. Fasting increased sirt1 and sirt5 expression in the liver for NAD+-mediated nutrient stress adaptation, while sirt2 responded to oxidative stress in the brain tissue. The study identified teleost-specific duplications (sirt3 and sirt5), suggesting aquatic adaptation. These findings reveal how NAD+-Sirt signaling networks regulate metabolism and stress responses [61].

Several studies have focused on NAMPT (also known as pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor or visfatin), a rate-limiting enzyme in the NAD+ salvage pathway. NAMPT plays a vital role in maintaining intestinal integrity and immune competence in hybrid crucian carp (originated from White crucian carp (Carassius cuvieri, WCC, female) × Red crucian carp (C. auratus red var., RCC, male)) [62]. NAMPT sustains intracellular NAD+ levels by transforming nicotinamide into NMN, supporting energy metabolism, redox balance, and NAD+-dependent enzymes such as SIRTs and PARPs. Increased Nampt expression improves barrier function and bacterial resistance, as observed in hybrid crucian carp specimens injected with Aeromonas hydrophila. These findings underscore the pivotal role of NAD+ metabolism in fish health and immune defense. Higher Nampt levels lead to a marked increase in the number of goblet cells in the distal intestine. Additionally, Nampt significantly increased the expression of antimicrobial molecules, such as interleukin 22 (IL-22), hepcidin-1 (an antimicrobial peptide), liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 (LEAP-2), and mucin 2 (MUC2), as well as tight junction proteins, such as zonule 1 and occludin. In line with these observations, fish treated with NAMPT showed a significant decrease in intestinal permeability and apoptosis, thereby strengthening host defense against bacterial infections [63]. The role of NAD+ in feeding regulation in goldfish (C. auratus) showed that NAMPT affected appetite-regulating neuropeptides, indicating NAD+ metabolism is central to energy production and integrated with neuroendocrine circuits controlling feeding in fish [64]. Studies have focused on appetite regulation and feeding behavior, which are important in aquaculture. However, little attention has been paid to their effects on NAD+ metabolism. Ceramides suppress food intake in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) by modulating appetite-regulating neuropeptides. While NAD+ has not been directly studied, evidence suggests ceramides impair mitochondrial function and increase oxidative stress, depleting NAD+ levels, which are SIRT1 cofactors regulating metabolism and feeding. NAD+ decline reduces SIRT1 activity, disrupting neuropeptide balance, while ceramide-driven inflammation activates NAD+-consuming enzymes, worsening NAD+ depletion [65]. Ceramide-NAD+ interactions may drive metabolic dysregulation in fish, similar to mammals. Studies should examine whether NAD+ restoration reduces ceramide’s anorexigenic effects. Research on SIRT1 in goldfish indicated links between NAD+-dependent sensing and feeding behavior. Fasting affects hypothalamic expression, with SIRT1 associating with orexigenic neuropeptides. SIRT1 activation during fasting suggests its role as a nutrient sensor connecting energy status and appetite regulation, consistent with its NAD+-dependent function in vertebrates [66]. These findings provide evolutionary insights into conserved feeding regulation mechanisms, suggesting that SIRT-mediated metabolic adaptation may connect the peripheral energy status with central appetite pathways in fish.

4.2. NAD+ and SIRTs as Molecular Hubs for Environmental Stress Adaptation in Fish

NAD+ is integral to the oxidative stress response and pathways related to environmental adaptation, which are crucial for fish to cope with various environmental stressors, including pollutants, pesticides, and nanoparticles. These pathways are essential for maintaining the redox balance, energy metabolism, and cellular homeostasis under adverse conditions.

4.2.1. NAD+ Role in Stress Responses

Evidence links thermal physiology and cellular stress responses, highlighting NAD+/SIRT pathways in environmental adaptation. Seasonal acclimatization induces muscle plasticity in carp through epigenetic regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis, involving NAD+-dependent sirtuin pathways as environmental sensors. Cold acclimation upregulated ribosomal biogenesis genes while altering DNA methylation at rDNA loci, suggesting temperature-sensitive epigenetic reprogramming. These findings show how fish optimize muscle function through epigenetic mechanisms, where sirtuin-mediated sensing translates thermal signals into adaptive expressions [67]. Cold acclimation in sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) triggers a stress response through the upregulation of heat shock proteins (HSP70 and HSP90) and NAD+-dependent SIRTs (SIRT1 and SIRT3), showing a conserved mechanism linking proteostasis and metabolic adaptation. These findings reveal tissue-specific responses and suggest that SIRT-mediated mitochondrial changes and HSP protein stability enhance cold tolerance through NAD+-sensitive pathways [68].

The function of SIRT2 was analyzed in the regulation of adipocyte maturation during hypoxic adaptation in fish, emphasizing its role as an NAD+-dependent regulatory mechanism. These findings indicate that hypoxia induces the differential expression of sirt2, which constrains adipocyte maturation by modulating lipid metabolism and cellular differentiation pathways. This adaptive response suggests that SIRT2 plays a pivotal role in metabolic reprogramming under low oxygen conditions, potentially preserving energy homeostasis. Novel insights into how hypoxia influences lipid storage and metabolic flexibility in aquatic species through NAD+-dependent sirtuin signaling were demonstrated, providing broader implications for understanding vertebrate stress adaptation mechanisms [69].

Stress disrupts the hypothalamic circadian system and appetite regulation in rainbow trout through the coordinated actions of cortisol and NAD+-dependent SIRT1, thereby linking endocrine stress responses with metabolic regulation. Stress-induced elevation of cortisol suppresses sirt1 expression in the hypothalamus, correlating with disruptions in circadian clock genes and altered orexigenic/anorexigenic peptide expression. Stress-mediated NAD+/SIRT1 suppression impairs circadian timing and energy homeostasis, with SIRT1 integrating metabolism. Environmental challenges disrupt fish feeding through SIRT pathways, affecting aquaculture welfare [70].

The physiological and molecular responses of roughskin sculpin (Trachidermus fasciatus) to osmotic stress were analyzed, revealing significant alterations in Na+/K+-ATPase activity, caspase 3/7 activity, and expression of stress-related genes (e.g., sirt1 and hsp70). Osmotic stress induces cellular stress and apoptosis while modulating Sirt1 expression, suggesting NAD+-dependent SIRT signaling’s role in adaptation. The upregulation of sirt1 and hsp70 activates stress response pathways, providing insights into osmoregulatory mechanisms in euryhaline fish through ion transport and NAD+-sensitive responses [71]. The molecular characterization and stress-responsive expression of sirt2, sirt3, and sirt5 in Wuchang bream were analyzed under temperature and ammonia nitrogen stress. Results demonstrated that SIRTs play crucial roles in metabolic regulation and stress adaptation. Under thermal and ammonia-induced stress, SIRT2, SIRT3, and SIRT5 showed tissue-specific expression patterns, suggesting their roles in cellular homeostasis and mitochondrial function. NAD+-dependent sirtuin activity reveals stress tolerance mechanisms in fish [72].

A novel dual regulatory mechanism has been identified in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), wherein SIRT1 modulates p53-mediated apoptosis through both KAT8-dependent and KAT8-independent pathways, underscoring the functional complexity of NAD+-dependent deacetylation in fish. SIRT1 suppresses apoptosis by deacetylating p53 at K382 (KAT8-dependent) and inhibiting p53 transcriptional activity through KAT8-independent interactions, revealing an evolutionary innovation in teleost stress response. These NAD+-sensitive mechanisms enhance cell survival under oxidative stress, providing the first evidence that fish sirtuins regulate apoptotic thresholds via multiple p53-targeting strategies. SIRT1 metabolic sensing via NAD+ integrates conserved and lineage-specific anti-apoptotic mechanisms [73].

In summary, these studies underscore SIRTs as molecular hubs in environmental adaptation, linking metabolic and stress response networks in fish. SIRTs act as metabolic stress sensors, connecting cellular energy status to adaptive responses, including mitochondrial modifications, HSP induction, and metabolic reprogramming (Table 1). While certain pathways are conserved, teleosts show unique adaptations. SIRTs integrate with cortisol, the circadian clock, apoptosis regulators, and metabolic enzymes to maintain homeostasis under stress. Understanding these mechanisms could enhance fish welfare and predict adaptive capacities.

Table 1.

Role of NAD+/SIRT pathways in fish stress and environmental adaptation.

4.2.2. Disruption of NAD+-Dependent Pathways in Aquatic Organisms Exposed to Environmental Contaminants

Numerous studies have focused on the role and modulation of metabolic pathways involving NAD+ in animals exposed to various contaminants (Table 2). A previous study investigated the biochemical responses of the wild chub (Leuciscus cephalus) to environmental pollutants, showing oxidative stress and metabolic enzyme changes. Alterations in the biochemical markers of aquatic pollution effects in chub liver tissues from various river sites were characterized by different pollution types and levels. These findings were compared to the concentrations of organochlorine compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and heavy metals. Enzymes associated with NAD+ metabolism and redox balance are affected, suggesting that NAD+-dependent pathways are critical for the response of fish to pollutant stress. The disruption of NAD+ metabolism highlights the importance of maintaining the cellular energy balance when exposed to environmental toxicants [74].

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a family of synthetic compounds that are widely used in various industrial applications (such as refrigerants and lubricants in electrical equipment) but are now banned because of their persistence in the environment and toxicity. The effects of PCB 153 exposure on the brain proteome of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) revealed significant alterations in proteins involved in energy metabolism, oxidative stress response, and disruptions in NAD+-dependent pathways. These findings suggest that PCB 153 exposure impairs NAD+-linked metabolic functions in the brain, which could contribute to neurotoxicity and compromise neuronal health in fish [75]. Similarly, bifenthrin is a pyrethroid insecticide that is widely used to treat ant infestations. Bifenthrin toxicity affects rainbow trout through endocrine disruption and oxidative stress, disrupting NAD+/NADH balance and energy production. NAD-dependent enzymes in DNA repair and hormone biosynthesis are impacted by pesticide exposure. Besides this, salinity acclimation affects metabolic demands and NAD metabolism, potentially altering fish sensitivity to bifenthrin [76].

Molybdo-flavoenzymes (MFEs) [such as aldehyde oxidase (AOX) and xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR)] are involved in the oxidation of N-heterocyclic compounds and aldehydes, including environmental pollutants, drugs, and vitamins. This biotransformation generates more polar compounds for easier excretion; thus, MFEs are classified as detoxification enzymes [77]. Studies on MFE properties in non-mammalian vertebrates are limited. XOR activity occurs in fish liver using xanthine as substrate and O2/NAD+ as electron acceptors, showing oxidase and dehydrogenase activities. In rainbow trout, which have AOXβ and XOR, trout XOR uses only NAD+ as an electron acceptor, unlike mammalian XOR, which uses both NAD+ and O2 [78].

17α-ethinylestradiol is a synthetic estrogen primarily utilized in oral contraceptives, although it is also present in other contraceptive forms such as patches. It is recognized for its estrogenic effects and occurrence in the environment, particularly in treated wastewater [79]. A metabolomic study showed that exposure to environmentally relevant levels of 17α-ethinylestradiol causes metabolic disruptions in crucian carp, including alterations in NAD+ metabolic pathways. Changes in energy metabolism and redox homeostasis were detected, indicating that NAD+-dependent processes were sensitive to endocrine disruptors. Such disturbances could impair the cellular energy balance and contribute to toxic effects on fish physiology [80]. Lufenuron and flonicamide affect the immune system and antioxidant gene expression in common carp gills. Since antioxidant defense and immune function are linked to cellular redox balance, NAD+ acts as a coenzyme in redox reactions and as a substrate for PARPs and SIRTs involved in oxidative stress responses. Altered NAD+ metabolism could affect antioxidant genes and immune responses under pesticide stress in this fish species [81]. Triclosan (TCS) is a chemical compound with antibacterial and antifungal properties, which is used in various consumer products such as soaps, toothpastes, and cosmetics [82]. TCS affects redox-sensitive microRNAs (RedoximiRs)/SIRT/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), revealing disruption of NAD+-dependent antioxidant defenses. TCS exposure alters redox imiRs, downregulates sirtuin activity, and impairs Nrf2/ARE-mediated antioxidant responses, leading to oxidative stress. TCS compromised the NAD+/SIRT axis, which is crucial for maintaining redox homeostasis through Nrf2 regulation. The results showed TCS’s ecotoxicological risks by disrupting aquatic organisms’ cellular defense mechanisms, highlighting NAD+-dependent SIRT signaling’s protective role. The interference of contaminants with wildlife antioxidant pathways is demonstrated [83]. Paracetamol is a medication widely used as an analgesic and antipyretic, and it is also present in the environment [84]. The SIRT/PXR signaling pathway response in yellowstripe goby (Mugilogobius chulae) exposed to paracetamol was investigated, highlighting NAD+-dependent mechanisms in detoxification and adaptation. Paracetamol exposure modulated SIRTs, particularly SIRT1 and SIRT3, which are involved in oxidative stress mitigation through NAD+-mediated pathways. Activation of the pregnane X receptor (PXR) suggests a defense mechanism for xenobiotic metabolism. The role of NAD+-linked SIRT activity in cellular resilience to pharmaceutical pollutants was demonstrated, providing insights into the molecular adaptations of aquatic organisms to environmental contaminants [85]. Atorvastatin is a type of medication used to lower cholesterol in humans [86]. The effects of atorvastatin on the SIRT/PXR signaling pathway were also studied in the same fish species (yellowstripe goby), revealing its role in NAD+-dependent cellular defense. Atorvastatin exposure altered sirt1 and sirt3 expression and activated PXR, suggesting an adaptive response to xenobiotic stress. Atorvastatin enhances antioxidant capacity through NAD+-mediated SIRT activity, thereby regulating oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways. The role of the SIRT/PXR axis in mediating pharmaceutical stress responses in aquatic organisms was demonstrated, providing insights into NAD+ metabolism and xenobiotic detoxification while showing the protective role of NAD+-linked pathways [87]. Triclocarban (TCC), a polychlorinated antimicrobial agent, has been used in toys, clothing, packaging, medical supplies, and personal care products, such as soaps and toothpaste. Although used for more than 50 years, concerns regarding its endocrine-disrupting properties have recently emerged [88]. TCC triggers neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation in common carp by disrupting SIRT3-mediated redox homeostasis, demonstrating a novel immunotoxic mechanism. TCC exposure suppressed NAD+-dependent SIRT3 activity, leading to mitochondrial ROS accumulation and ERK1/2/p38 MAPK signaling pathway activation, driving NETosis. These effects were mitigated by Sirt3 overexpression or antioxidant treatment, confirming the SIRT3-ROS crosstalk in TCC-induced NET formation. This was the first evidence that environmental pollutants can hijack NAD+-SIRT networks to dysregulate innate immunity in fish, thereby linking metabolic stress to excessive inflammatory response. Ecological risks were underlined while elucidating a conserved mechanism by which NAD+ depletion predisposes to immunopathology [89]. Neurotoxic effects of wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents were studied on juvenile Atlantic cod, showing transcriptomic disruptions in the brain tissue related to oxidative stress, neurotransmission, and NAD+-dependent pathways. The downregulation of genes in mitochondrial function and antioxidant defense indicates impaired NAD+-SIRT signaling, a key regulator of neuronal homeostasis. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products alter stress genes and neurotransmitter receptors, with effects persisting after depuration. These findings show marine fish vulnerability to these compounds, suggesting NAD+ metabolism disruption as a neurotoxic mechanism [90]. Fluorene-9-bisphenol (BHPF) is a substitute or alternative for bisphenol A (BPA), which is used in the manufacture of plastics, including materials that are in contact with food. Furthermore, BHPF is increasingly being used in plastic products. The protective mechanism of quercetin against BHPF-induced apoptosis in epithelioma papulosum cyprini (EPC) cells through SIRT3-mediated mitophagy has been elucidated. Quercetin upregulates NAD+-dependent Sirt3 expression, activates mitophagy to remove damaged mitochondria, and reduces oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Quercetin counteracts BHPF cytotoxicity by restoring mitochondrial homeostasis via NAD+/SIRT3/mitophagy. These results show the potential of flavonoids to reduce toxicant damage in aquatic organisms while demonstrating the role of sirtuins in stress responses. The research uncovered the processes that connect the protective effects of phytochemicals with the toxic impact of xenobiotics on fish cells [91].

Several studies have examined the adverse effects of ammonia and hydrogen peroxide. These basic chemical compounds are composed of small, lightweight elements that are commonly used as cleaning and disinfecting agents. Both substances function as oxidizing or reactive agents, making them effective in eliminating bacteria and stains. Because of these characteristics, ammonia and hydrogen peroxide are frequently used in industrial cleaning products. Sublethal ammonia exposure in delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus) has revealed physiological disruptions that affect its survival. The observed oxidative stress aligns with ammonia-induced disruption of NAD+-dependent pathways. These results indicated that ammonia triggers cellular stress through a redox imbalance associated with NAD+ homeostasis, suggesting population threats by impairing metabolic resilience linked to NAD+-sirtuin networks [92]. A transcriptomic study showed that hydrogen peroxide exposure disrupts brain function in common carp by inducing oxidative stress and altering neurotransmission pathways. Given that NAD+ is a central cofactor in redox reactions and DNA repair, oxidative damage increases NAD+ consumption while impairing regeneration. These findings suggest that maintenance of NAD+ homeostasis is critical for neuronal energy metabolism under oxidative stress in aquatic vertebrates [93].

Other studies have focused on the negative impacts of heavy metals on fish environments. Methylmercury, a neurotoxic pollutant, affects the brains of Atlantic cod. Focusing on proteomic changes, the affected proteins were found to be related to NAD-dependent pathways, including mitochondrial function and energy metabolism. Brain proteomic alterations in methylmercury-exposed cod likely disrupt NAD-associated processes, contributing to neurotoxicity [94]. Cadmium (Cd) exposure induces immunotoxicity in common carp by dysregulating the miR-217/SIRT1/NF-κB axis through NAD-dependent Sirt1 suppression. Cd upregulates miR-217, which inhibits sirt1 expression, leading to NF-κB hyperacetylation and overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Sirt1 reactivation or miR-217 inhibition restored immune homeostasis, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting the miR-217/SIRT1 axis to mitigate Cd-induced inflammation in aquatic organisms [95]. Environmentally relevant concentrations of zinc (Zn) induce hepatic lipophagy in fish through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of Beclin1 while alleviating copper (Cu)-induced lipotoxicity. Zn activates NAD+-dependent SIRT1, which deacetylates Beclin1 to promote autophagic flux and lipid clearance, whereas Cu disrupts this mechanism. Zn supplementation restored SIRT1/Beclin1 signaling and mitigated Cu-induced lipid accumulation, accentuating the role of metal homeostasis in regulating NAD+–sirtuin–autophagy pathways. These results provided the first evidence that trace metals modulate lipid metabolism through post-translational regulation of autophagy in aquatic species [96]. ZnO nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and immune toxicity in crucian carp, triggering NETs. Oxidative stress affects NAD+/NADH balance, impacting NAD+-dependent metabolic pathways for redox homeostasis and immune function. These disturbances in NAD+ metabolism contribute to immune dysregulation in fish exposed to pollutants [97]. In contrast, Cu and Zn deficiencies induced hepatic lipotoxicity in fish through mitochondrial oxidative stress-mediated inhibition of the Sirt3/Foxo3/PPARα pathway, revealing NAD+ homeostasis dependence. Cu and Zn are essential trace elements for terrestrial organisms. A single dietary Cu or Zn deficiency leads to liver lipid deposition and causes metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Fish and mammals share similarities in uptake, storage, utilization, excretion, and interaction of metal ions [98]. However, the metal-detoxifying protein metallothionein is expressed at lower levels in fish than in mammals [99]. Trace element co-deficiency suppresses NAD+-dependent Sirt3 activity, leading to Foxo3 hyperacetylation, impaired PPARα signaling, disruption of lipid oxidation, and exacerbation of hepatic steatosis in yellow catfish (Tachysurus sinensis). Mitochondrial ROS accumulation has been identified as both a cause and consequence of NAD+/Sirt3 axis dysfunction, leading to metabolic dysregulation. These results establish the role of Cu/Zn in maintaining the mitochondrial redox balance and sirtuin function, providing insights into how micronutrient deficiencies affect NAD+-sensitive pathways in vertebrates. Sirt3 activation was suggested as an intervention for trace element-related hepatotoxicity [100].

Table 2.

Disruption of NAD+-dependent pathways in fish exposed to contaminants.

Table 2.

Disruption of NAD+-dependent pathways in fish exposed to contaminants.

| Fish Species/Model | Contaminant/Stressor | Assay Conditions | Main Affected Pathway | Main Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chub (Leuciscus cephalus) | Environmental pollutants (organochlorines, PAHs, heavy metals) | Determined in river sediments | NAD+ metabolism/redox enzymes | Oxidative stress, metabolic enzyme disruption, pollutant-type dependent responses | [74] |

| Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) | PCB 153 (Polychlorinated biphenyl 153) | Intraperitoneal injection of 0, 0.5, 2, and 8 mg/kg | NAD+-linked energy metabolism | Brain proteome alterations, neurotoxicity risk | [75] |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Freshwater and salinity Bifenthrin (pesticide) | Salinity 8 g/L and 17 g/L Pesticide 0, 0.1, and 1.5 µg/L | NAD+/NADH balance | Oxidative stress, endocrine disruption, and salinity interaction | [76] |

| Rainbow trout (O. mykiss) | Molybdo-flavoenzymes (AOX, XOR) | Determination in liver fractions | NAD+-dependent oxidoreduction | XOR exclusively NAD+-dependent, detoxification role | [78] |

| Crucian carp (Carassius carassius) | 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2) | 17.1 μg/L | NAD+ metabolism | Disrupted energy/redox homeostasis, endocrine disruption | [80] |

| Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | Lufenuron (LUF) and Flonicamide (FL) (pesticides) | 10% of LUF 4.3 mg/L and 10% of FL 0.1 mg/L | NAD+-linked antioxidant/immune pathways | Altered antioxidant gene expression and immune response | [81] |

| Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) | Triclosan (antibacterial compound) | Environmentally relevant concentrations in water (ng-μg/L) | NAD+/SIRT/Nrf2 signaling | Downregulated SIRT, impaired antioxidant defenses | [83] |

| Yellowstripe goby (Mugilogobius chulae) | Paracetamol (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) | 0.5, 5, 50, and 500 μg/L | NAD+/SIRT/PXR pathway | SIRT1/3 activation, oxidative stress mitigation, xenobiotic defense | [85] |

| Yellowstripe goby | Atorvastatin (hypolipidemic drug) | 5, 50 and 500 μg/L 24, 72, and 168 h of exposure | NAD+/SIRT/PXR pathway | Altered sirt1/3 expression, antioxidant/inflammatory regulation | [87] |

| Common carp | Triclocarban (TCC) (antimicrobial compound) | 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 μM for 3 h | NAD+/SIRT3/redox balance | NET formation via SIRT3 inhibition, ROS accumulation | [89] |

| Atlantic cod | Wastewater treatment plant effluents | in a fjord North of Stavanger (the fourth-largest city in Norway) | NAD+-SIRT/neuronal-related genes | Transcriptomic disruption, impaired mitochondrial defense | [90] |

| EPC fish cells | Fluorene-9-bisphenol (Bisphenol A substitute) (used in plastic) | 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 160 μM, | NAD+/SIRT3/mitophagy | Quercetin protection restored mitochondrial homeostasis | [91] |

| Delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus) | Ammonia | median lethal concentration of 13 mg/L, and un-ionized ammonia of 147 μg/L | NAD+-redox pathways | Oxidative stress, metabolic resilience disruption | [92] |

| Common carp | Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | 0 and 1 mM of H2O2 for 1 h per day, lasting 14 days | NAD+ redox/DNA repair | Neuronal oxidative damage, impaired NAD+ regeneration | [93] |

| Atlantic cod | Methylmercury | 0, 0.5, and 2 mg/kg | NAD+-linked mitochondrial pathways | Brain proteome disruption, neurotoxicity | [94] |

| Common carp | Cadmium | 0.005, 0.05, and 0.5 mg/L for 30 days | miR-217/NAD+-SIRT1 axis | Immune dysregulation, NF-κB hyperacetylation | [95] |

| Fish (various species including Tachysurus sinensis) | Zinc (Zn) and Copper (Cu) | Industrial Zn and Cd water | NAD+-SIRT1/3-autophagy | Zn activates lipophagy, Cu disrupts it, and co-deficiency worsens steatosis | [96,97,98,99,100] |

| Crucian carp | ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) | 200 mg/kg intraperitoneally injected | NAD+ redox/immune NETs | Oxidative stress, immune toxicity, NAD+ disruption | [97] |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) and Gibel carp (Carassius gibelio) | Resveratrol (polyphenol) and cold conditions | Dietary 25 mg/kg and 27 °C or 15 °C (cold conditions) for three days | NAD+-SIRT1/stress response | Enhanced antioxidant capacity, cold/ammonia stress protection | [101,102] |

| Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB126) is used in electronic products, lubricants, and insecticides and astilbin (flavonoid) | 75 μM PCB126 and/or 0.5 mM Astilbin for 24 h in the cell culture media | NAD+-SIRT1/Nrf2 | Protection against PCB126-induced apoptosis | [103] |

To address and mitigate the adverse effects experienced by fish due to the presence of these environmental contaminants, various compounds have been evaluated. Resveratrol, a polyphenol that acts as a powerful antioxidant, is found in the skins of grapes, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, and peanuts. Resveratrol enhances cold stress tolerance in tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) by activating NAD+-dependent SIRT1 signaling, which upregulates metabolic and antioxidant machinery for cellular homeostasis. Resveratrol enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, antioxidant activity, and Hsp70 expression while reducing oxidative damage via Sirt1 activation, showing potential to improve fish resilience through NAD+-SIRT pathways in ectotherms [101]. Resveratrol mitigates ammonia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction in Gibel carp (Carassius gibelio) by activating NAD+-dependent SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling. Resveratrol enhanced antioxidant capacity, reduced inflammation, and improved mitochondrial function by upregulating SIRT1-mediated PGC-1α deacetylation. The protective role of NAD+/SIRT1 against ammonia toxicity suggests that resveratrol could have therapeutic potential through sirtuin pathways. This reveals how polyphenols counter xenobiotic damage via NAD+-sensitive networks in fish [102]. Astilbin alleviates PCB126-induced hepatocyte apoptosis in grass carp through SIRT1/Nrf2 acetylation to restore mitochondrial function. Astilbin activates Sirt1, which deacetylates Nrf2 to enhance antioxidant activity against PCB126-induced oxidative stress. Through SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling, astilbin reduced cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation, mitigating apoptosis. These findings demonstrate flavonoids’ potential in aquaculture by targeting NAD+-sirtuin pathways to protect against xenobiotic-induced hepatotoxicity [103]. Although these results are encouraging, further research is essential to achieve results that can be broadly applied to various types of pollutants and fish species.

4.2.3. NAD+-Sensitive Mechanisms in Fish Metabolic Adaptations: Insights for Managing Aquaculture-Associated Disorders

The involvement of NAD+ in metabolic homeostasis and its pathological disruption is a subject of extensive research in humans. However, its specific functions in fish metabolic adaptation remain unexplored. Nevertheless, the available results elucidate conserved yet distinct NAD+/SIRT1-mediated mechanisms that underpin dietary adaptability in teleosts, revealing a compelling therapeutic avenue for the management of metabolic syndromes in commercially relevant fish species (Table 3).

Studies have examined NAD+’s role in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and endocrine disruption. Research showed rainbow trout liver and Brockmann bodies use glucokinase-independent mechanisms for glucose sensing, involving NAD+-dependent SIRTs in metabolic regulation. Metabolic responses to glucose fluctuations align with NAD+-sensitive networks in mammals, suggesting SIRT-mediated adaptation plays a key role in teleost energy homeostasis. These findings establish a basis for studying NAD+-linked nutrient sensing in aquatic species, impacting vertebrate metabolic flexibility [104].

NAD+ has not been directly investigated in many metabolic studies in fish, but the results suggest that NAD+ is involved in many processes. Connections between adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), lipid metabolism, inflammation (TNF-α), and NAD+ biology can be established. ATGL is the rate-limiting enzyme in triglyceride breakdown and releases fatty acids (FFAs) and glycerol. FFAs oxidize mitochondria, generate NADH, and affect the NAD+/NADH ratios. Impaired lipolysis disrupts mitochondrial function and NAD+ homeostasis. LPS induces TNF-α expression associated with metabolic dysfunction. Chronic inflammation activates PARP-1 and CD38, thereby depleting NAD+. Low NAD+ levels impair SIRT1 activity, which regulates lipid metabolism. Metabolic stress can alter NAD+ levels in aquaculture. Boosting NAD+ improves metabolic resilience under stress [105]. Future research should explore whether LPS-induced TNF-α affects NAD+ levels and whether NAD+ supplementation modulates ATGL activity or inflammatory responses in fish.

Controlled feeding restriction mitigated high-carbohydrate diet-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in Wuchang bream by activating the NAD+-dependent AMPK-SIRT1 pathway. Feeding restriction enhances SIRT1 activity, suppressing NF-κB-mediated inflammation and upregulating antioxidant defenses while improving glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function through AMPK-dependent NAD+ elevation. These results show feeding restriction as an aquaculture strategy to counter diet-induced metabolic disorders by activating NAD+-sensitive pathways that optimize energy homeostasis in fish [106].

Dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) mitigate hepatic steatosis-induced inflammation in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) by activating the NAD+-dependent SIRT1 pathway, which also suppresses NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses. The results showed that n-3 PUFAs upregulated Sirt1 expression and activity, leading to deacetylation and cytoplasmic retention of the NF-κB p65 subunit, thereby reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production (e.g., interleukin 1β). These anti-inflammatory effects are associated with improved lipid metabolism and redox homeostasis, highlighting the dual role of n-3 PUFAs in alleviating both metabolic dysfunction and inflammation through the SIRT1-mediated NAD+-sensitive pathways. These findings provide insights into how dietary lipids modulate hepatocyte inflammation in marine fish, supporting n-3 PUFAs as functional nutrients to enhance metabolic health in aquaculture [107]. Dietary fenofibrate reduces high-fat diet-induced hepatic lipid accumulation and inflammation in juvenile black seabream by activating the PPARα/SIRT1 axis, demonstrating a conserved NAD+-dependent metabolic mechanism in fish. Fenofibrate, a lipid-lowering compound, enters fish through feed supplementation, simulating uptake from contaminated environments. It is commonly prescribed to regulate human lipid metabolism [108]. When introduced into aquatic systems via wastewater, fenofibrate may affect fish. The treatment upregulated PPARα and Sirt1 expression, enhanced fatty acid oxidation, and reduced lipogenic gene and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Activation of these pathways reduces ER stress and improves mitochondrial function through NAD+-sensitive SIRT signaling. PPARα activation can rescue diet-induced metabolic dysfunction in marine fish by synergizing with SIRT1, offering potential treatments for aquaculture metabolic disorders [109].

The role of SIRT1 has been studied in the largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), emphasizing its critical NAD+-dependent functions in regulating lipid metabolism and antioxidant responses. The activation of Sirt1 promotes lipid catabolism while inhibiting lipogenesis, and it significantly enhances resistance to oxidative stress through the NAD+/SIRT1/FOXO1 signaling pathway. Seven SIRT orthologs (SIRT1–7) showed distinct tissue expression patterns. Sirt1 and sirt3 are highly expressed in metabolically active tissues like the liver and muscle. Fasting increased sirt1 and sirt5 expression in the liver for NAD+-mediated nutrient stress adaptation, while sirt2 responded to oxidative stress in the brain. The study identified teleost-specific gene duplications (sirt3 and sirt5), suggesting aquatic adaptation. These findings help understand NAD+-sirtuin signaling networks in this aquaculture species [110]. These findings advance our understanding of the conserved functions of SIRT in vertebrates.

Betaine, also known as trimethylglycine (TMG), is a naturally occurring quaternary ammonium compound derived from glycine. As an osmolyte, betaine maintains cellular osmotic balance and protects against environmental stress. It acts as a methyl group donor in one-carbon metabolism, remethylating homocysteine to methionine. These properties make it significant for liver function, cardiovascular health, and metabolism [111]. A previous study showed that dietary betaine supplementation reduced high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis and inflammation in juvenile black seabream by activating the NAD+-dependent Sirt1/SREBP-1/PPARα pathway. Betaine increased hepatic NAD+ levels through Sirt1-mediated deacetylation of SREBP-1, suppressing lipogenesis while increasing PPARα-driven fatty acid oxidation. These effects reduced inflammatory markers and improved mitochondrial function, demonstrating betaine’s role in modulating NAD+/Sirt1 signaling to rebalance lipid metabolism. This reveals how betaine integrates one-carbon metabolism with sirtuin-mediated regulation, offering a strategy to combat diet-induced metabolic disorders in aquaculture [112]. Sirt1 also plays a crucial protective role against hepatic lipotoxicity in fish fed a high-fat diet through NAD+-dependent deacetylation of inositol-requiring enzyme 1 alpha (Ire1α). Ire1α is a transmembrane sensor protein located in the ER that plays a central role in the unfolded protein response, helping cells adapt to ER stress [113]. These findings demonstrated that Sirt1 activation alleviates high-fat diet-induced ER stress and lipid accumulation by deacetylating Ire1α, thereby restoring hepatic metabolic homeostasis in black sea bream. Notably, this study identified a conserved NAD+/Sirt1/Ire1α axis in fish that modulated lipid metabolism under nutritional stress, mirroring mammalian pathways. An evolutionary link between SIRT-mediated metabolic regulation and nutritional stress responses in vertebrates was established [114]. Fucoidan is a polysaccharide mainly consisting of l-fucose and sulfate groups. It is highly valued worldwide, especially in the food and pharmaceutical sectors, owing to its potential therapeutic benefits. The remarkable biological activity of fucoidan is attributed to its unique molecular structure. Fucoidan is known for its antioxidant, antitumor, anticoagulant, antithrombotic, immunoregulatory, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory properties [115]. Fucoidan alleviates hepatic lipid deposition in black seabream by activating SIRT1-mediated modulation of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 axis, revealing a novel NAD+-dependent mechanism linking ER stress to lipid metabolism. Fucoidan enhanced SIRT1 activity, attenuating ER stress by suppressing the PERK pathway, reducing lipogenic gene expression, and promoting fatty acid oxidation. These effects enhanced mitochondrial function and redox balance through NAD+-sensitive SIRT1 signaling, providing the first evidence that marine polysaccharides regulate hepatic lipid metabolism in fish via the SIRT1/PERK axis, offering potential dietary solutions for metabolic disorders in aquaculture [116].

Table 3.

Role of NAD+ in fish metabolic regulation and disruption.

Table 3.

Role of NAD+ in fish metabolic regulation and disruption.

| Fish Species | Metabolic Regulation | Main Findings Related to NAD+/SIRTUINS (SIRTs) Metabolism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Glucose | Glucokinase-independent glucose sensing in liver and Brockmann bodies; metabolic regulation linked to NAD+-dependent SIRTs; suggests alternative nutrient-sensing pathways | [104] |

| Several fish species | Lipids | Link between adipose triglyceride lipase, lipid metabolism, inflammation, and NAD+ depletion; low NAD+ impairs SIRT1 activity, affecting lipid metabolism and inflammation | [105] |

| Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) | Glucose | Feeding restriction activates NAD+-dependent AMPK-SIRT1 pathway, suppressing nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)-mediated inflammation and oxidative stress, improving glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function | [106] |

| Large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) | Lipids | n-3 PUFAs activate the NAD+–SIRT1 pathway, reducing NF-κB-mediated inflammation, improving lipid metabolism, and redox balance | [107] |

| Black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii), juvenile | Lipids | Fenofibrate activates the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα)/SIRT1 axis, enhancing fatty acid oxidation and reducing lipogenesis and inflammation, alleviating high-fat diet-induced hepatic dysfunction | [108] |

| Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) | Lipids | SIRT1 regulates lipid catabolism, inhibits lipogenesis, and enhances antioxidant defenses via NAD+/SIRT1/FOXO1 (Forkhead Box O3a) signaling; it is upregulated under nutrient deprivation. | [110] |

| Black seabream, juvenile | Lipids | Betaine supplementation restores NAD+, activates SIRT1/Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1 (SREBP-1)/PPARα pathway, reduces lipogenesis, enhances fatty acid oxidation, lowers inflammation, and improves mitochondrial function. | [112] |

| Black seabream | Lipids | SIRT1 protects against hepatic lipotoxicity through NAD+-dependent deacetylation of Ire1α, alleviating endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and lipid accumulation. | [113,114] |

| Black seabream | Lipids | Fucoidan activates SIRT1, modulating PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 axis, reducing ER stress, enhancing fatty acid oxidation, and improving redox homeostasis. | [116] |

5. NAD+ Metabolism and Neuromodulation in Fish: From Muscle Innervation to Cognitive Function

The main results of this topic are summarized in Table 4. The presence of different putative neuromodulators in the nerves innervating the skeletal muscles of teleosts has been previously investigated. Morphological investigation involved histochemical staining of cryostat sections from the epaxial, hypaxial, and adductor mandibulae muscles of the gilthead seabream and eel (Anguilla anguilla) to reduce NADPH-diaphorase activity. This study links NAD metabolism to neuromodulation, as NADPH-diaphorase enzymes produce nitric oxide (NO), with NADPH serving as a cofactor in fish muscle function modulation [117].

Table 4.

NAD metabolism and neuromodulation in fish.

Table 4.

NAD metabolism and neuromodulation in fish.

| Species/Model | Focus/Pathway | NAD+/NADPH Role | Main Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata), and eel (Anguilla anguilla) | Neuromodulators and NADPH-diaphorase | NADPH as a cofactor for nitric oxide (NO) production | Histochemical staining revealed NADPH-diaphorase activity in skeletal muscle nerves, linking NAD metabolism to NO-mediated neuromodulation of muscle function. | [117] |

| General vertebrate model | cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB) transcription factor | Indirect NAD+/SIRT1 (sirtuin 1) regulation | CREB integrates extracellular signals into gene expression changes, regulating survival, metabolism, and circadian rhythms. | [118] |

| Goldfish (Carassius auratus) | CREB in learning and memory | NAD+-SIRT1 regulation of CREB | Cognitive activity triggers CREB phosphorylation in memory-related brain areas; NAD+-SIRT1 likely modulates CREB-dependent plasticity. | [119] |

| Goldfish | miRNA-132/212 and fear memory | NAD+ in neuroplasticity and epigenetics | miRNAs regulate neuronal plasticity; altered NAD+ metabolism may affect memory formation and synaptic function. | [120] |

| Mediterranean farmed fish | Somatotropic axis and growth regulation | NAD+/SIRT1 metabolic regulation | Nutrition and environment modulate hepatic sirtuin activity; diet enhances NAD+-SIRT1 signaling, stress impairs growth via metabolic disruption. | [121] |

| Swordtail fish (Xiphophorus helleri) | NADPH-diaphorase atlas and escape reflex | NADPH as NOS cofactor | Mapped NADPH-d in Mauthner cells; linked NADPH-dependent NO signaling to escape reflex pathways. | [122] |

| Dogfish (Triakis scyllia) | Vagal afferent NADPH-d activity | NADPH in sensory NO signaling | NADPH-d in vagal afferents suggests NADPH-dependent NO production in sensory/autonomic pathways. | [123] |

| Cichlid (Tilapia mariae) | NADPH-d in the central nervous system | NADPH in neural development | Histochemistry showed NADPH-d activity essential for NO-mediated maturation of neuronal pathways. | [124] |

| African cichlid (Haplochromis burtoni) | Brain regional NADPH-d mapping | NADPH turnover from NAD+ | Enrichment in the entopeduncular nucleus suggests localized NAD+/NADP+ demand for NO signaling. | [125] |

| Goldfish (Carassius auratus) | Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and NADPH-d distribution | NADPH as a cofactor for NO | Broad distribution in brain regions for sensory, motor, and neuroendocrine regulation. | [126] |

| Grass puffer (Takifugu niphobles) | NOS in the branchial innervation | NADPH-dependent (NOS) activity | NOS activity in glossopharyngeal/vagal afferents links NAD+ metabolism to vascular regulation in gills. | [127] |

| Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) | NAD+ in acoustic stress response | NAD+/NADH redox in auditory stress | Genes linked to NAD+ metabolism and oxidative stress protect auditory tissues from loud sound damage. | [128] |

The cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB) functions as a transcription factor. It converts external signals into lasting gene expression changes within the cell nucleus, activating genes for learning, memory, survival, metabolism, and circadian rhythms [118]. CREB signaling in spatial learning and memory was explored in goldfish, showing that cognitive activities trigger CREB phosphorylation in brain areas linked to learning. Although it does not directly address NAD+ or SIRTs, CREB activation is associated with NAD+-dependent SIRT1 regulation in vertebrates. These results suggest that goldfish use conserved mechanisms of spatial cognition, including sirtuin-mediated regulation. These findings provide insights into fish neurobiology and metabolic effects on cognition across species [119]. In goldfish, spatial learning has been studied regarding CREB signaling activation. CREB is crucial for memory formation and synaptic plasticity. NAD acts as a cofactor for sirtuins (SIRT1), which modulate CREB activity in learning and memory. NAD-dependent pathways may influence CREB activation during spatial learning [119]. Changes in microRNA-132/212 expression affect fear memory. NAD+ metabolism, which supports neuronal homeostasis and sirtuin-mediated regulation, could intersect with miRNA processes influencing memory. Altered NAD+ levels may affect synaptic function and neuroprotective mechanisms [120].

The regulatory mechanisms of the somatotropic axis in Mediterranean marine farmed fish were investigated, demonstrating that nutritional and environmental factors modulate growth through NAD+-sensitive metabolic pathways. Dietary and environmental stressors alter hepatic SIRT activity and NAD+ bioavailability, thereby influencing growth hormone signaling and energy allocation. Optimal nutrition enhances NAD+/SIRT1 signaling and metabolic efficiency, but environmental challenges disrupt this pathway, causing growth retardation. These findings reveal the link between nutrient sensing and endocrine growth regulation in fish, informing aquaculture optimization through metabolic targeting [121].

NADPH-diaphorase (NADPH-d) activity, linked to nitric oxide (NO) signaling, has been mapped in fish species, showing NAD-related cofactors’ role in neural function and sensory processing. A detailed atlas of NADPH-d activity in swordtail fish (Xiphophorus helleri) brains was developed. This enzyme has been studied in Mauthner cells involved in fish escape reflexes. NADPH-d marks nitric oxide synthase (NOS), which produces NO from L-arginine, linking NADPH activity to brain escape responses and NO-mediated neurotransmission [122]. NADPH-d activity was studied in the vagal afferent pathway of dogfish (Triakis scyllia) and suggests that NADPH-dependent NO production plays a significant role in neural signaling within this sensory pathway. This highlights the importance of NADPH in modulating neural functions related to autonomic control via NO synthesis [123]. NADPH-d activity was investigated in the central nervous system of cichlid fish (Tilapia mariae). These results demonstrated the importance of NADPH in the maturation and functioning of neuronal pathways in fish, emphasizing its critical role in NO-mediated neurodevelopment and neural communication [124]. Another histochemical study mapped NADPH-d activity in the brains of African cichlid fish (Haplochromis burtoni), with notable enrichment in the entopeduncular nucleus. NADPH is generated from NADP+, which is ultimately derived from NAD+ via phosphorylation, indicating that these patterns reflect the localized metabolic demand for NAD+-derived cofactors. These results suggest that specific brain regions have elevated NAD+/NADP+ turnover to sustain NO signaling, highlighting the integration of redox cofactor metabolism with neuromodulatory functions in teleosts [125]. NADPH-diaphorase activity and NOS reactivity were analyzed in the goldfish central nervous system. NADPH-diaphorase, reflecting NOS activity, is distributed across brain regions controlling sensory processing, motor function, and neuroendocrine regulation, highlighting NADPH’s role as a cofactor in NO production, a key neuromodulator in teleost brain functions [126]. On the other hand, NOS was studied in the glossopharyngeal and vagal afferent pathways of the grass puffer (Takifugu niphobles), focusing on branchial vascular innervation. NAD metabolism was linked directly to NO signaling pathways in fish, stressing the role of NADPH-dependent NOS activity in regulating vascular function and neural signaling in teleost gills [127]. Another study underscored NAD’s critical role in cellular resilience and neuroprotection of fish exposed to acoustic stress. A specific gene set was identified in the ears of fish, using Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) as a model to assess the potential impact of loud sounds, such as those from seismic surveys. Research has focused on genes involved in auditory function, stress responses, and cellular repair mechanisms. Among these, genes related to NAD+/NADH-dependent processes and oxidative stress pathways have been identified, reflecting the importance of redox balance and energy metabolism in protecting auditory tissues from sound-induced damage [128]. Given the unique sensory characteristics of marine fish and the vast diversity of species, further research on the effects of NAD+ metabolism on these sensory systems and their relationship with the central nervous system is recommended.

6. Dietary Interventions and NAD+ Homeostasis: Implications for Fish Health and Product Quality