Abstract

Ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) is a key subunit of ferritin and serves as a core regulator of iron metabolism, playing an important role in alleviating cellular damage caused by oxidative stress or regulating programmed cell death. This study identified 7 FTH1 homologs (AgFTH1-1 to AgFTH1-7) across the entire genome of Anadara granosa and investigated their expression responses during Vibrio infection. The 7 AgFTH1 genes are arranged in tandem across 6 chromosomes, with AgFTH1-5 and AgFTH1-6 undergoing gene amplification via a local duplication event. Among these homologous genes, 5 genes contain a single conserved ferritin domain (PF00210) and retain key ferroxidase center residues (Glu23, His65). Following Vibrio infection, these 5 genes exhibit downregulated expression, which may increase intracellular free iron and be consistent with ferroptosis-like cell death contributing to pathogen clearance, as suggested by previous studies. AgFTH1-5 contains a signal peptide and exhibits increased expression, suggesting it may regulate extracellular local iron storage. AgFTH1-4 (synaptonemal N-terminal SNARE) and AgFTH1-7 (GTPase domain) lack signal peptides, exhibit atypical structures, and show no significant expression changes under bacterial stress, indicating they may be associated with vesicle trafficking rather than classical iron storage. This study systematically analyzed the genomic features and expression patterns of the FTH1 gene family in A. granosa, laying a foundation for further revealing its role in shellfish immune defense.

Key Contribution:

This study systematically identified the FTH1 gene family in Anadara granosa for the first time. It elucidates the evolutionary and functional characteristics of the mollusk FTH1 family, provides new insights into iron-dependent immune defense mechanisms in invertebrates, and offers potential targets for disease prevention and control in aquaculture.

1. Introduction

Iron is an essential trace element in organisms, participating in key physiological processes such as hemoglobin synthesis, respiratory chain electron transfer, and DNA repair. However, excessive free iron can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the Fenton reaction, leading to lipid peroxidation and cellular damage [1,2,3]. Maintaining iron homeostasis is a fundamental prerequisite for organism survival and health, and ferritin heavy chain (FTH1), as a core regulator in the iron metabolism and antioxidant defense network, plays an irreplaceable role in this process.

FTH1 is the functional subunit of the ferritin complex, which efficiently catalyzes the oxidation of ferrous ions (Fe2+) to ferric ions (Fe3+) and mediates the safe storage of iron in the ferritin nanocage, thereby limiting the accumulation of unstable iron pools in cells and inhibiting ROS production and oxidative stress [2,3,4]. Additionally, FTH1 has been confirmed as a core negative regulator of the ferroptosis pathway—its downregulation can lead to Fe2+ overload in cells, triggering lipid peroxidation reactions and ultimately inducing cell death [5,6,7]. In vertebrates, the function of FTH1 has been extensively studied, and FTH1 shows promising therapeutic potential in the treatment of tumors and oxidative stress-related diseases [8,9].

However, research on FTH1 in mollusks remains insufficient. Although some studies have preliminarily explored the expression characteristics of FTH1 in a few species such as Procambarus clarkii [10] and bivalves like Scapharca broughtonii [11], where ferritin suppresses pathogen growth by storing iron, little is known about the evolutionary patterns, structural and functional diversification of this gene family, and its mechanistic role in the immune defense systems of invertebrates. Similarly, in fish, ferritin and its related genes participate in oxidative stress defense mechanisms by regulating iron ion storage [12]. Given that invertebrates rely on innate immunity (such as phagocytosis and oxidative stress defense) to resist pathogen invasion. Iron, as an essential nutrient for pathogen proliferation, may serve as a key regulatory node in invertebrate antibacterial immunity through metabolic balance [13]. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by lipid peroxidation [5,6]. Furthermore, given the high iron content and sustained mitochondrial activity in the hemocytes of A. granosa, changes in ferritin expression may alter the level of free Fe2+. Thus, it is hypothesized that ferroptosis could be a mechanistically plausible response of A. granosa hemocytes when encountering Vibrio stress.

The blood clam (Anadara granosa), as an important intertidal economic shellfish and aquaculture species in China, is widely distributed along the southeastern coast [14,15], but it often faces pathogen stresses such as Vibrio during aquaculture, leading to large-scale mortality and constraining industry development. Compared to other mollusks, A. granosa has unique physiological features: its hemocytes are rich in hemoglobin, with extremely high iron content [16]. More crucially, these hemocytes retain functional mitochondria, a structural feature that provides important support for its active cellular metabolism and stress responses [17,18]. Because iron homeostasis is central to hemoglobin activity, it is indispensable for A. granosa’s physiological functions and for mounting immune responses to invading pathogens. This prompts two key questions: (1) Does FTH1 participate in invertebrate pathogen defense by regulating iron metabolism? (2) Does its gene family exhibit species-specific functional differentiation? Addressing these questions not only refines the evolutionary and functional understanding of the ferritin family but also provides new perspectives for elucidating iron-mediated disease resistance mechanisms in invertebrates. In view of this, this study uses A. granosa as the research object to systematically analyze the genomic features and expression patterns of the FTH1 gene family, aiming to reveal its role in shellfish immune defense and provide theoretical basis for disease prevention and control in aquaculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Bacterial Stimulation

Approximately 600 healthy adult specimens of Anadara granosa (average shell length: 24.04 ± 0.74 mm; wet mass: 11.06 ± 0.90 g), estimated to be around two years old, were procured from a mariculture site in Xiangshan, Ningbo, China (29°38′ N, 121°46′ E). Before conducting the infection trials, the clams were maintained for one week in 100 L aerated glass aquaria containing 80 L of filtered seawater. Environmental parameters were held constant (salinity 21.9 ± 0.5‰; temperature 26 ± 1 °C; pH 8.2 ± 0.1; dissolved oxygen 6.0 ± 1.0 mg/L) and monitored daily with a multiparameter water-quality meter (YSI ProPlus; YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA). During acclimation and subsequent experimentation, clams received a daily ration of Platymonas subcordiformis (20,000 cells/mL). To maintain stable water quality, 50% of the seawater in each aquarium was exchanged two hours after feeding.

Three Vibrio species—Vibrio parahaemolyticus (BYK00036), Vibrio harveyi (BB120), and Vibrio alginolyticus (ATCC17749)—were obtained from the National Pathogen Resource Center. Each strain was grown in 2216E (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China; catalog number: LA0341; dilution: N/A) broth at 37 °C with agitation (180 rpm) for 12 h until reaching the mid-exponential phase. Cultures were collected by centrifugation (5000× g, 10 min, 4 °C), washed twice with sterile seawater, and adjusted to the target density as confirmed via colony enumeration on 2216E agar.

Following the 7-day acclimatization period, 300 clams were transferred into 50 L tanks (three replicates of 100 clams each) containing a final concentration of 1.0 × 107 CFU/mL of a mixed vibrio bacteria (1:1:1 ratio). A control group of 300 clams, with 100 clams per tank across three replicates, was maintained under identical conditions. All clams were sourced from the same population and matched for weight and age.

2.2. Genome-Wide Identification

Anadara granosa (also referred to as Tegillarca granosa) is a bivalve mollusk classified within the phylum Mollusca, class Bivalvia, order Veneroida, and the family Arcidae, under the genus Anadara. It is widely recognized as the blood clam. The reference genome and corresponding gene annotation for Tegillarca granosa (GCA_013375625.1) were downloaded from NCBI Refseq [14]. Utilized HMMER3 v3.3.2 software (employing the hmmsearch command, the standard tool for querying a profile against a sequence database in HMMER) to screen the A. granosa proteome. We used the Pfam ferritin domain model file (PF00210) as the query, set an E-value threshold of 1 × 10−5 as the inclusion criterion, and defined additional filtering rules: (1) For sequences with truncated FTH1 domains (domain coverage < 50% relative to the full-length PF00210 model), we discarded them to ensure structural integrity of the target domain; (2) For multi-domain proteins containing multiple FTH1 domains, we retained only those with the highest domain coverage (≥80%) and the lowest E-value (≤1 × 10−10) to avoid redundant or low-confidence hits. Matching sequences were filtered through conserved domain (CDD) and InterProScan annotations to identify complete ferritin domains. The molecular mass and theoretical isoelectric point of the FTH1 proteins from A. granosa were computed using the ProtParam module available on the ExPASy platform (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/; accessed on 5 October 2025).

2.3. Chromosomal Locations and Phylogenetic Analysis

Chromosomal locations and positional information for the AgFTH1 gene family were retrieved from the A. granosa genome. Gene distribution was visualized using TBtools-II v2.224, with gene nomenclature assigned according to their chromosomal order [19]. Conserved domain sequences from all candidate proteins were aligned using ClustalX2 (http://www.clustal.org/clustal2/; accessed on 5 October 2025) under default settings. The resulting alignments were subsequently converted into Nexus and Phylip file formats and imported into MEGA11 (https://www.megasoftware.net/; accessed on 5 October 2025) for downstream phylogenetic analyses. A maximum likelihood (ML) tree was conducted on the program RAxML-NG v1.2.2 with the following parameters: the best-fit evolutionary model, VT + R4, which was predicted by Iq-Tree 3.0.1; bootstrap, 1000 replicates.

2.4. Structural and Functional Prediction

To assess the sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships of AgFTH1 homologues, the 7 amino acid sequences were aligned using the ClustalX2 program. The alignment results were manually refined by reference to conserved residues characteristic of the ferritin family—particularly the catalytic residues within the ferrooxygenase center, such as Glu23, His65, and Glu107—to ensure reliability. For domain and motif characterization, all homologous sequences were submitted to the SMART v10.0 database for annotation. MEME Suite v5.5.5 was employed for motif analysis, with the motif number set to 8. Other key parameters adopted the software’s default settings and with resulting motifs compared across sequences. Subsequently, TBtools-II integrated gene structure information with motif patterns [20]. The three-dimensional structure of the FTH1 protein was predicted using AlphaFold2 v2.3.1 [21], with model confidence assessed via test scores (pLDDT). PyMOL v2.5.3 was used for visualizing the protein tertiary structure [22].

2.5. Gene Expression Profile Analysis and Validation

RNA sequencing data from hemocytes (PRJNA823812) collected post-infection (0, 48 h) and 7 distinct tissues (adductor muscle, foot, hepatopancreas, gill, mantle, gonad and hemocytes) (PRJNA594182) were uploaded to NCBI [19,23]. Transcriptome sequencing data from hemocytes 48 h post-Vibrio infection yielded gene expression profiles for AgFTH1. RNASeq reads were cleaned with fastp v0.23.2. RNASeq reads were mapped to reference genome using RSEM v1.3.3 and STAR v2.4.0j to estimate gene expression FPKM. Differential expression analysis was carried out using the DESeq2 v1.48.0 package in R (version 1.20.0). p-values generated from the model were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini—Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Transcripts with an FDR-adjusted p-value below 0.05 were considered significantly differentially expressed.

An interactive heatmap of AgFTH1 gene expression was generated and visualized using the pheatmap [24] in R based on FPKM values. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed using the TRIzol reagent method [25,26]. The expression levels of 7 AgFTH1 genes following Vibrio infection were detected via qRT-PCR using primers listed in Table 1. Standardization was performed using the 18S RNA gene of A. granosa as an internal control (Table 1) [27]. Expression of AgFTH1 was detected by qRT-PCR [28]. In summary, using the QuantStudioTM 7 Flex System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). The thermal cycling protocol included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 30 s. Relative expression levels of AgFTH1 were quantified across three technical replicates employing the 2ΔΔCT method [29].

Table 1.

Primers for qRT-PCR analysis of AgFTH1 genes.

Protein extraction and Western blotting procedures are detailed in [30]. Samples were loaded onto a 15% precast protein gel (Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., located in Shanghai, China, catalog number: P8210082). For each lane, the sample protein concentration was 0.731 μg/μL and 8 μL was loaded. Band intensities were measured with ImageJ v1.54q14, normalized to GAPDH as an internal control, and statistically compared using a t-test. The target protein, Ferritin Heavy Chain (Wanlei Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China; catalog number: WL05360; dilution: 1:1000), was detected using a rabbit anti-ferritin heavy chain antibody. Internal controls comprised mouse anti-GAPDH (Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; catalog number: Ag0766; dilution: 1:50,000) and rabbit anti-xCT (Abmart Inc., Shanghai, China; catalog number: T57046; dilution: 1:500). Finally, the chemiluminescent substrate ECL (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA; catalog number: 34580; dilution: N/A) was mixed in a 1:1 ratio and applied to the PVDF membrane (Merck Millipore Ltd., Carrigtohill, Ireland; catalog number: IPVH00010; dilution: N/A). Signals were generated using a chemiluminescence imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA; catalog number: 1708280; dilution: N/A).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted with at least three biological replicates (each comprising ten pooled individuals), with three technical replicates performed for each assay. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Intergroup comparisons were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (two groups); p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyzes were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of AgFTH1 Genes

The ferritin heavy chain 1 gene family was identified in A. granosa via PFAM’s HMM (PF00210), comprising seven homologous genes designated AgFTH1-1 to AgFTH1-7. Analysis of their physicochemical properties revealed protein lengths ranging from 124 to 669 amino acids, MW between 14.346 and 78.466 kDa, and pI from 4.228 to 6.280. Hydrophilicity analysis, indicated by GRAVY scores ranging from −0.735 to −0.436, indicating hydrophilic characteristics. Notably, 5 homologues possess a single FTH1 domain, AgFTH1-4 and AgFTH1-7, however, lack complete domains. Signal peptide predictions indicate that AgFTH1-5 and AgFTH1-6 contain signal peptides, potentially suggesting secretion/distribution into plasma, exosomes, or extracellular spaces. The absence of signal peptides in the remaining genes may imply intracellular iron storage or intracellular functions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nomenclature and basic physicochemical properties of AgFTH1 from A. granosa.

3.2. Chromosomal Locations and Evolutionary Analysis of AgFTH1

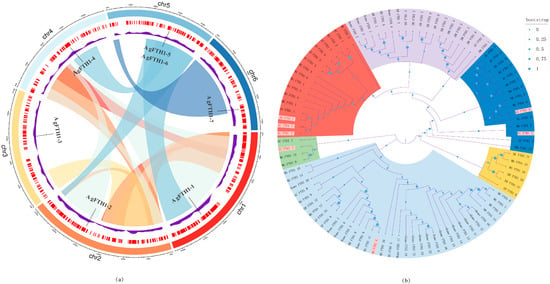

Chromosomal locations were determined from the genome GFF3 annotation file and visualized using Circos. Analysis revealed a relatively uniform distribution of the AgFTH1 gene across 6 chromosomes (Chr1–Chr6) (Figure 1a): Chromosome 5 contained 2 tandemly arranged genes (AgFTH1-5 and AgFTH1-6), while the remaining chromosomes each harbored a single gene. This pattern indicates that local duplication events drove the evolution of the AgFTH1 gene family and provides a foundation for exploring potential links between chromosomal architecture and gene regulatory mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal distribution of AgFTH1 genes and multi-species FTH1 phylogenetic tree in A. granosa (a) Chromosomal Distribution of AgFTH1 Genes: Chromosomal information for seven AgFTH1 genes is known, distributed across six chromosomes. Each chromosome is represented by an arc in a distinct color (Chr1: red, Chr2: orange, Chr3: yellow, Chr4: light blue, Chr5: blue, Chr6: dark blue). Connecting bands indicate gene duplication or linkage relationships, such as the tandem duplication between AgFTH1-5 and AgFTH1-6 on Chr5. Scale bar represents millions of base pairs. (b) Multispecies FTH1 protein phylogenetic tree: Sequences annotated with species abbreviations (AG: A. granosa; MG: Mytilus galloprovincialis; BG: Biomphalaria glabrata; AC: Aplysia californica, etc.). Multispecies phylogenetic tree of FTH1 proteins constructed via maximum likelihood analysis. Branches are color-coded to distinguish major evolutionary lineages: purple (vertebrates, e.g., Homo sapiens [Homo], Danio rerio [DR]); green (arthropods, e.g., Drosophila melanogaster [DM]); yellow (other invertebrate outgroups, e.g., Mytilus galloprovincialis [MG]); red (mollusks and related invertebrates, including the A. granosa [AG] cluster, e.g., Sepia pharaonis [SP]). Blue (Mollusca and related invertebrates, including members of the A. granosa [AG] cluster such as Mytilus galloprovincialis [MG], Aplysia californica [AC], etc.). Bootstrap support values are indicated by blue dots at nodes, with dot color intensity representing support probability according to the scale (0: low support, light blue; 1: high support, dark blue).

3.3. Structural Analysis and Functional Prediction

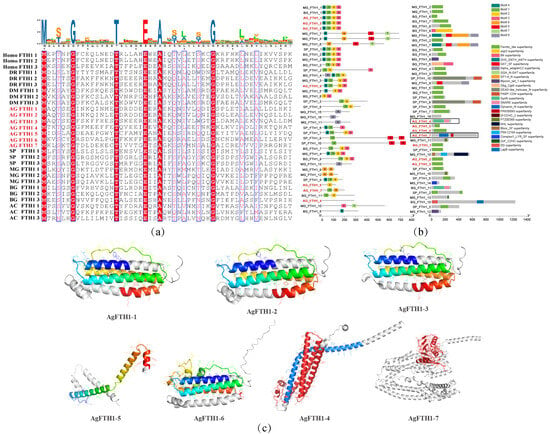

By analyzing the structural and functional characteristics of 7 AgFTH1 homologues, their role in iron homeostasis regulation is elucidated. Multiple sequence alignment reveals that the ferritin heavy chain domain within AgFTH1 proteins exhibits high conservation, particularly the ferroxidase center residues (Glu23, His65, Glu107), consistent with FTH1 homologues in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Figure 2a). MEME identified 8 conserved motifs, with Motif 1 (iron-binding site) and Motif 2 (ferroxidase center) are present in 5 core AgFTH1 sequences (AgFTH1-1, -2, -3, -5, and -6), supporting their role in iron metabolism (Figure 2b). SMART analysis confirmed the presence of the eukaryotic ferritin domain (PF00210) in 5 paralogues, whilst AgFTH1-7 exhibited truncated domains, suggesting functional diversification.

Figure 2.

Structural and functional characteristics of the FTH1 protein in A. granosa (a) Multiple sequence alignment of FTH1 proteins from A. granosa and representative vertebrate and invertebrate species. Highlighted are conserved residues within the ferritin heavy chain domain, including key hemochrome active site residues. (b) Distribution diagram of conserved motifs and domains in FTH1 proteins from A. granosa and other species, in which the domain-lacking AgFTH1-4 and AgFTH1-7 are marked with black boxes. (c) Three-dimensional structure visualization of the A. granosa FTH1 protein, with colored regions indicating ferritin domain segments. In AgFTH1-4, the red portion denotes the Syntaxin N-terminal/SNARE motif characterized by extended α-helices; whereas in AgFTH1-7, the Dynamin domain is highlighted in red.

AlphaFold2 modeling predicted high-confidence tertiary structures (pLDDT > 95) for all AgFTH1 subtypes, revealing 5 subtypes (AgFTH1-1, AgFTH1-2, AgFTH1-3, AgFTH1-5, AgFTH1-6) adopting a characteristic 24-mer nanocage architecture. These structures retain the quadruple helix bundle core and ferrooxygenase center essential for Fe2+ oxidation and iron storage (Figure 2c). In contrast, AgFTH1-7 contains a dynein GTPase domain, while AgFTH1-4 possesses a synaptinorhinase N-terminal SNARE motif, suggesting potential roles in membrane remodeling and vesicle fusion, respectively. These findings, corroborated by structural superposition with vertebrate FTH1, validate the conservation of catalytic residues and underscore the integrity of iron storage function in A. granosa.

3.4. Gene Expression Analysis

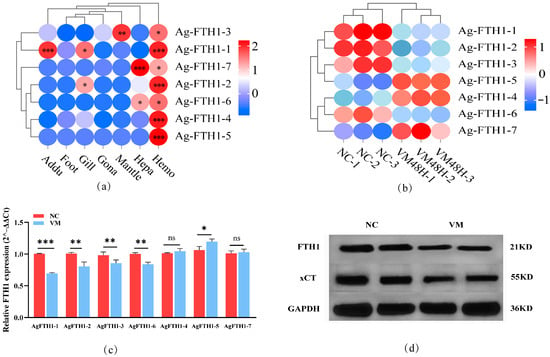

Tissue-specific analysis of A. granosa (Figure 3a) revealed markedly differentiated expression patterns among homologous genes: AgFTH1-7 exhibited elevated expression in the hepatopancreas, whilst AgFTH1-1 and AgFTH1-2 showed higher levels in gill tissue. All 7 AgFTH1 genes showed markedly higher expression levels in hemocytes than in other tissues-relative to the tissue with the lowest expression level (visualized as FPKM values; see Figure 3a), for example, AgFTH1-1 exhibited a fold-change in expression of 2.3 in the gill. Additionally, tissue-specific expression patterns were observed: AgFTH1-6 and AgFTH1-7 showed moderate expression in the hepatopancreas (1.5–2.1 -fold higher than the tissue with the lowest expression level), while AgFTH1-4 and AgFTH1-5 were nearly undetectable in non-hemocyte tissues, suggesting that different FTH1 genes may play crucial roles in the hemocytes of A. granosa.

Figure 3.

Expression analysis of FTH1 genes in A. granosa (a) Heatmap showing AgFTH1 transcript abundance across different tissues (adductor muscle, foot, hepatopancreas, gill, mantle, gonad, and hemocytes), with color gradients representing expression levels; * p > 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. (b) Transcriptome analysis showing the transcript levels of AgFTH1 paralogs in hemocytes following Vibrio exposure. (c) qRT-PCR validation of AgFTH1 expression. Bar plots depict the relative expression of 7 AgFTH1 genes in Vibrio-infected clams (VM 48 h) negative control (non-infected clams) (NC). ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. ns: no statistically significant changes (* p > 0.05). (d) Western blot analysis was performed on lysed blood cells using primary antibodies against FTH1, xCT, and GAPDH. Semi-quantitative analysis of the blotted bands was conducted, with relative band intensities normalized against GAPDH as a reference; n = 3 biological replicates. NC negative control (non-infected clams), while VM represents the vibrio-induced stress group.

Transcriptomic analysis of hemocytes following Vibrio-induced stress showed that AgFTH1-1, AgFTH1-2, AgFTH1-3, and AgFTH1-6 were significantly downregulated at 48 h post-stress in A. granosa hemocytes (DESeq2, adjusted p < 0.05), with AgFTH1-1 and AgFTH1-2 maintaining relatively high absolute expression levels (Figure 3b). Other family members, AgFTH1-4, AgFTH1-5, and AgFTH1-7, exhibited an upward trend in expression levels. These transcriptomic findings suggest that these expression changes likely underpin the antibacterial immune mechanisms of A. granosa, implying distinct regulatory mechanisms and functional roles.

qRT-PCR results revealed that, compared to the control group, AgFTH1-1, AgFTH1-2 transcription levels decreased by approximately 32% and 14%, respectively, and AgFTH1-3, AgFTH1-6 also decreased to varying degrees. AgFTH1-5 expression levels increased by 13%, while AgFTH1-4, AgFTH1-7 showed no significant changes (Figure 3c). Before conducting the analyses, the efficiency of each primer set was confirmed using a calibration curve derived from serially diluted pooled cDNA. All primers showed amplification efficiencies ranging from 95% to 105%, with correlation coefficients (R2) exceeding 0.99 (Supplementary Materials; Figure S1).

Western blot analysis revealed that FTH1 protein levels were reduced by approximately 45% overall compared to the control group, while xCT transporter expression exhibited a downregulation trend of around 30%, each represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three biological replicates. The grayscale intensity of the bands in the Western blots was quantified using ImageJ software and the differences were verified to be statistically significant via t-test (Figure 3d and Figure S2). Semi-quantitative analysis of Western blot bands was performed using ImageJ density analysis, normalized against GAPDH as an internal control. Immunoblotting results correlated with overall quantitative data, confirming that transcriptional downregulation led to a significant decrease in protein abundance.

4. Discussion

This study represents the first comprehensive characterization of the FTH1 gene family in A. granosa. A total of 7 homologous genes were identified, distributed across 6 chromosomes, significantly fewer than the 22 genes found in the human genome. This disparity in gene family size suggests that functional diversification within the FTH1 family may have occurred during the evolutionary history of A. granosa. Nevertheless, these members (AgFTH1-1, 2, 3, 5, 6) still retain the highly conserved ferritin domain (PF00210) and key active residues (Glu23, His65, and Glu107). Structural analysis reveals that the A. granosa FTH1 monomer exhibits a folding topology highly similar to that of the human FTH1 protein. Ferritin forms a classic 24-mer nanocage structure, with its internal cavity retains conserved iron-binding residues that support ferrioxygenase activity. This activity enables iron storage by oxidizing Fe2+ to Fe3+, thereby inhibiting the Fenton reaction [1,31,32,33].

Although the FTH1 family in A. granosa is highly conserved in terms of overall structure and core function in iron homeostasis regulation, functional differentiation has emerged among members within the family. Specifically, AgFTH1-1, AgFTH1-2, AgFTH1-3, and AgFTH1-6 are the core functional members of the family—they not only all contain complete ferritin domains (PF00210) and conserved core ferroxidase residues (Glu23, His65, Glu107). This structure is precisely the key basis for “achieving Fe2+ oxidation and iron storage”, indicating that they are the core executors of iron homeostasis regulation in A. granosa. Transcriptome and qRT-PCR results further confirmed that these four core members were significantly downregulated in hemocytes following 48 h of Vibrio infection: transcription levels of AgFTH1-1 and AgFTH1-2 decreased by approximately 32% and 14%, respectively, while total FTH1 protein levels declined by 45%. Similarly, xCT protein levels also decreased. Given the canonical role of FTH1 proteins in iron sequestration, we hypothesize that this downregulation may reduce intracellular iron-storage capacity and thereby alter the pool of labile Fe2+ available within hemocytes [34,35,36,37]; such changes in iron availability may also affect the iron nutrients accessible to invading Vibrio spp. We further hypothesize that hemocytes of A. granosa respond to pathogen invasion in part by triggering ferroptosis-like processes.

In contrast, AgFTH1-4, AgFTH1-5, and AgFTH1-7 exhibit distinct functional differentiation characteristics compared to the core members. AgFTH1-5 contains a signal peptide, and its transcriptional level is upregulated by 13% after Vibrio infection. It is speculated that AgFTH1-5 may be secreted extracellularly or localized in the extracellular space; by enhancing local iron storage capacity, it inhibits free Fe2+-mediated oxidative damage to protect healthy immune cells, thereby forming synergy with the core members [12,38]. Domain annotations indicate that AgFTH1-4 and AgFTH1-7 deviate from the canonical ferritin architecture: AgFTH1-4 harbors an N-terminal synaptotagmin/SNARE-like motif and AgFTH1-7 contains a dynein-like GTPase domain, and neither protein possesses a signal peptide. These in silico observations suggest that these paralogues may be associated with intracellular membrane dynamics (for example, vesicle trafficking or membrane remodeling) rather than classic iron sequestration. We emphasize that this interpretation is provisional and based solely on sequence-level predictions. Although they show no significant expression changes under Vibrio infection, and it cannot be confirmed yet whether they are directly involved in antibacterial immunity, they have already demonstrated a clear functional division of labor with the core members in terms of “iron homeostasis regulation”.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically characterized the FTH1 gene family in the blood clam A. granosa for the first time. A total of 7 homologous genes were identified, which exhibit structural conservation in the ferritin domain and key active residues, while showing obvious functional diversification among members. Specifically, following Vibrio infection, the core FTH1 members (AgFTH1-1, -2, -3, and -6) in the hemocytes of A. granosa are significantly downregulated; under Vibrio stress, AgFTH1-5 exhibits an upregulated trend, while AgFTH1-4 and AgFTH1-7 show no significant changes in expression. These results shed light on the evolutionary and functional characteristics of the FTH1 family in mollusks: for instance, AgFTH1-5 may protect healthy immune cells through its extracellular iron storage function, whereas AgFTH1-4 and AgFTH1-7 may play roles in non-traditional cellular processes such as vesicle fusion and membrane remodeling. Based on the above observations, we hypothesize that the downregulation of core FTH1 members may involve a potential regulatory mechanism. This mechanism may lead to the accumulation of free Fe2+ and the induction of ferroptosis, which in turn may contribute to the antibacterial immunity of invertebrates. These findings provide a novel perspective for understanding iron-dependent immune defense mechanisms in mollusks. Future studies should validate the aforementioned hypothesized pathway by directly measuring Fe2+ levels, lipid peroxidation levels, GPX4 activity, and pathogen loads. This will deepen the understanding of the relationship between iron metabolism and immunity in shellfish and identify potential targets for aquaculture disease control.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes10120646/s1, Figure S1. The standard curve was plotted using a tenfold dilution of cDNA, with the log value of the template dilution series on the X-axis and the corresponding Ct values on the Y-axis. Figure S2. Quantification of AgFTH1, xCT protein levels in hemolymph from the NC and VM groups (relative to GAPDH). The grayscale intensity of the bands in the western blots was quantified using ImageJ software. Asterisks indicate significant differences: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Author Contributions

Methodology and experiments, L.Z. and S.H.; software and visualization, L.Z. and Y.X.; data analyses, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.W. and Y.X.; project administration, S.W.; and funding acquisition, S.W. and Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32273123), Zhejiang Provincial Major Science and Technology Special Project (2021C02069-7), the Ningbo Municipal Public Welfare Science and Technology Special Project (2023S086), the Ningbo Municipal Natural Science Foundation Key Project (2023J042), and the Zhejiang Provincial Key Discipline Construction Project for Bioengineering (CX2024044).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research utilized Anadara granosa, an invertebrate species. In accordance with broadly recognized ethical frameworks and standard institutional regulations, studies involving invertebrates typically do not require formal ethical review or approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [NCBI] [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_013375625.1/; accessed on 5 October 2025] [GCA_013375625.1].

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to Wang Sufang and Bao Yongbo for their invaluable suggestions and constructive discussions regarding the experimental design. We also thank Xiangshan Aquaculture Farm (Ningbo, China) for their assistance in collecting Anadara granosa specimens.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in any of the following: the design of this study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A. granosa | Anadara granosa |

| VM | Vibrio-infected |

| NC | negative control (non-infected clams) |

| WB | Western blotting |

References

- Arosio, P.; Ingrassia, R.; Cavadini, P. Ferritins: A family of molecules for iron storage, antioxidation and more. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1790, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Lu, J.; Hao, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Kuang, W.; Chen, D.; et al. FTH1 Inhibits Ferroptosis Through Ferritinophagy in the 6-OHDA Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 1796–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, A.; Lu, J.; Wang, X.; Yi, C.; Yang, F. An Overview of Heavy Chain Ferritin in Cancer. Front. Biosci. 2023, 28, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, M.; Kagan, V.; Bayir, H.; Pagnussat, G.C.; Head, B.; Traber, M.G.; Stockwell, B.R. Regulation of lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in diverse species. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.; Lemberg, K.; Lamprecht, M.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.; Friedmann Angeli, J.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascón, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B.; Chen, X. Baicalin induces ferroptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma by suppressing the activity of FTH1. J. Gene Med. 2024, 26, e3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Monian, P.; Quadri, N.; Ramasamy, R.; Jiang, X. Glutaminolysis and Transferrin Regulate Ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Gu, W.; Wei, Y.; Mou, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Q. CGI1746 targets σ1R to modulate ferroptosis through mitochondria-associated membranes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.H.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, D.-Z.; Liu, Q.-N.; Tang, B.-P.; Dai, L.-S. Ferritin Heavy-like subunit is involved in the innate immune defense of the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1411936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, B.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, L.; Tian, J.; Sun, X.; Yang, A. Ferritin has an important immune function in the ark shell Scapharca broughtonii. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016, 59, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; Cheng, Z.; He, B.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Hu, J.; Lei, L.; Wang, L.; Bai, Y. Ferroptosis in aquaculture research. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wong, N.-K.; Yuan, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Genomic Insights into the Origin and Evolution of Molluscan Red-Bloodedness in the Blood Clam Tegillarca granosa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2351–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y. Hemoglobins from Scapharca subcrenata (Bivalvia: Arcidae) likely play an bactericidal role through their peroxidase activity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 253, 110545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, C. Oxidative burst without phagocytes: The role of respiratory proteins. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, F.; Tait, S. Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 21, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xin, W.; Anderson, G.; Li, R.; Gao, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S. Double-edge sword roles of iron in driving energy production versus instigating ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Tang, M.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Z.; Wang, S.; Bao, Y. Genome-wide identification and immune response analysis of serine protease inhibitor genes in the blood clam Tegillarca granosa. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 131, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive analyzes of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, A.; Evans, R.; Jumper, J.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Sifre, L.; Green, T.; Qin, C.; Žídek, A.; Nelson, A.W.R.; Bridgland, A.; et al. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 2020, 577, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeliger, D.; de Groot, B. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. J. Comput. Aid. Mol. Des. 2010, 24, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zha, S.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, W.; Lin, Z.; Bao, Y. Genome-wide identification and characteristic analysis of PGRP gene family in Tegillarca granosa reveals distinct immune response of the invasive pathogen. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 121, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps Version 1.0.12 from CRAN. 2019. Available online: https://rdrr.io/cran/pheatmap/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Ma, J.; He, Y.; Wu, C.; Liu, H.; Hu, Z.; Sun, G. Cloning and molecular characterization of a SERK gene transcriptionally induced during somatic embryogenesis in Ananas comosus cv. Shenwan. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 30, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Wang, S.; Bao, Y. Genome-wide identification and immune response analysis to Vibrio for heme peroxidase in the blood clam Anadara granosa. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D 2025, 54, 101430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; He, X.; Jin, H.; Su, D.; Lin, Z.; Liu, H.; Bao, Y. Hemocyte proliferation is associated with blood color shade variation in the blood clam, Tegillarca granosa. Aquaculture 2023, 571, 739447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Y. TAL1-mediated regulation of hemocyte proliferation influences red blood phenotype in the blood clam Tegillarca granosa. Aquaculture 2024, 586, 740801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) gene family in allotetraploid Brassica napus reveals changes in WOX genes during polyploidization. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jin, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, H.; Bao, Y. The critical role of transcription factor GATA1 in erythrocyte proliferation and morphology in blood clam Anadara granosa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 315, 144691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Parida, A.; Raut, R.K.; Behera, R.K. Ferritin: A Promising Nanoreactor and Nanocarrier for Bionanotechnology. ACS Bio Med Chem Au 2022, 2, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarmand Ebrahimi, K.; Hagedoorn, P.; Hagen, W. Unity in the biochemistry of the iron-storage proteins ferritin and bacterioferritin. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 295–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhoberac, B.; Vidal, R. Iron, Ferritin, Hereditary Ferritinopathy, and Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Han, K.; Li, N. Nicorandil Regulates Ferroptosis and Mitigates Septic Cardiomyopathy via TLR4/SLC7A11 Signaling Pathway. Inflammation 2024, 47, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, F.; Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, T.; Mao, S.; Yan, Y.; et al. PHGDH Inhibits Ferroptosis and Promotes Malignant Progression by Upregulating SLC7A11 in Bladder Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5459–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppula, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Amino acid transporter SLC7A11/xCT at the crossroads of regulating redox homeostasis and nutrient dependency of cancer. Cancer Commun. 2018, 38, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Lv, Z.; Zhou, N.; Bian, C.; Sun, S. Hypoxia induces ferroptotic cell death mediated by activation of the inner mitochondrial membrane fission protein MTP18/Drp1 in invertebrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, L.; Ma, R.; Wei, F.-Q.; Wen, Y.-H.; Zeng, X.-L.; Sun, W.; Wen, W.-P. Comprehensive analysis of ferritin subunits expression and positive correlations with tumor-associated macrophages and T regulatory cells infiltration in most solid tumors. Aging 2021, 13, 11491–11506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).