Abstract

Within the freshwater fish order Cypriniformes, loaches form a monophyletic lineage comprising nine families with more than 1400 species. Secondary sexual dimorphism is widespread among loach families, most notably in the form of enlarged pectoral fins and tubercles or other ossified structures on the pectoral fin in adult males. To date, the family Botiidae, phylogenetically sister to all other loach families, was reported to lack such sexually dimorphic structures, leading to the hypothesis that the common ancestor of loaches did not exhibit sexual dimorphism. Here, we report the presence of sexual dimorphism in eight species of Botiidae: Leptobotia bellacauda, L. guilinensis, L. microphthalma, L. taeniops, L. tchangi, Parabotia fasciatus, Sinibotia pulchra, and S. robusta. In all species, adult males possess longer pectoral fins than females. Additionally, males of L. guilinensis and L. tchangi exhibit larger pelvic fins, while males of L. microphthalma have larger anal fins. In L. bellacauda, L. microphthalma, and L. tchangi, portions of the dorsal surface of the pectoral fin bear rows of tubercles. The three genera displaying sexual dimorphism belong to two different subfamilies, demonstrating that sexual dimorphism is widespread across Botiidae and not restricted to a single genus or subfamily. Our results show that sexual dimorphism is present in the most basal family of loaches, suggesting that it represents a synapomorphy of loach fishes.

Key Contribution:

Our results indicate that Botiidae exhibit a form of sexual dimorphism similar to that observed in other loach families, characterised by enlarged pectoral fins and, in some species, tubercles on the fins. Because these traits are rare in non-loach Cypriniformes, we suggest that this type of sexual dimorphism was likely present in the common ancestor of loaches, representing a synapomorphy of the lineage.

1. Introduction

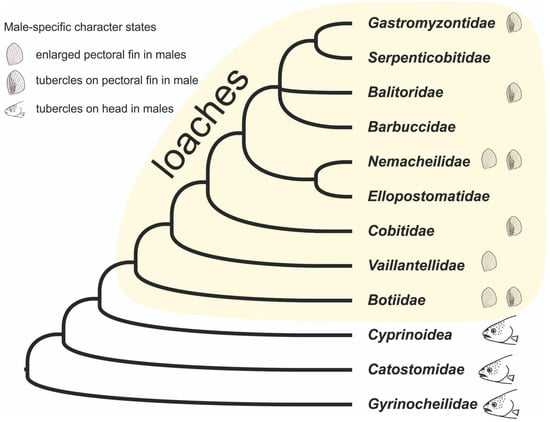

The order Cypriniformes, the largest order of freshwater fishes in the world, has long been divided into two superfamilies: Cyprinoidea and Cobitoidea [1,2,3]. According to this classical concept Cobitoidea comprise the families Catostomidae and Gyrinocheilidae, together with a large monophyletic lineage collectively referred to as the “loaches,” which includes nine families (Balitoridae, Barbuccidae, Botiidae, Cobitidae, Ellopostomatidae, Gastromyzonidae, Nemacheilidae, Serpenticobitidae, and Vaillantellidae) with more than 1400 species. However, recent studies [4,5,6] suggest that Catostomidae and Gyrinocheilidae are rather basal to Cyprinoidea and loaches (loaches thus remain as the only group within Cobitoidea). The monophyly of the loach lineage remains undisputed; it has been supported by both osteological evidence [7,8] and molecular data [2,9,10]. Furthermore, three of the nine loach families possess an erectable suborbital spine derived from the lateral ethmoid bone—an anatomical structure absent in all non-loach fishes. Since these three families (Botiidae, Cobitidae, and Serpenticobitidae) are not particularly closely related (see Figure 1), Šlechtová et al. [2] considered the suborbital spine to be a morphological synapomorphy of loaches that has been secondarily reduced in the six remaining families.

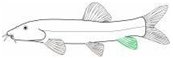

Figure 1.

Habitus of eight species of Botiidae with a sexual dimorphism, pictures not to scale. (a) Leptobotia bellacauda Bohlen & Šlechtová, 2016, 64.7 mm SL; (b) Leptobotia guilinensis Chen, 1980, about 69 mm SL; (c) Leptobotia microphthalma Fu & Ye, 1983, about 70 mm SL; (d) Leptobotia taeniops (Sauvage, 1878), 73.5 mm SL; (e) Leptobotia tchangi Fang, 1936, 65.1 mm SL; (f) Parabotia fasciatus Guichenot, 1872, about 120 mm SL; (g) Sinibotia pulchra (Wu, 1939), about 67 mm SL; (h) Sinibotia robusta (Wu, 1939), 59.1 mm SL.

Few other synapomorphic traits are known from the external morphology of loaches [11]. We consider the presence of one maxillary and two mandibular pairs of barbels one such synapomorphy, as this combination is not found in the closely related Catostomidae, Gyrinocheilidae, or Cyprinoidea [12]. The number of barbels is reduced only in the genus Ellopostoma [13] and in the cobitid genera Bibarba [14] and Neoeucirrhichthys [15] and increased only in the cobitid genus Quintabarbates [16], thus representing a nearly always existing diagnostic character for loaches.

Loaches are distributed throughout Asia and Europe, where they are abundant and represent a characteristic element of the ichthyofauna of this double-continent [17]. Many loach species exhibit sexual dimorphism, most commonly with males being smaller than females. Sexual size dimorphism occurs in many fish lineages for various ecological or behavioural reasons [18], but in some loach genera, such as Cobitis, this difference is functionally related to spawning behaviour: during mating, the male encircles the female’s body in a complete tight ring. The head of the male lays next to its caudal peduncle on the body side of the female. In this position, the anal openings of both partners are close to each other and gametes are released. Since spawning takes place mostly during the night inside dense vegetation, the formation of the ring is essential for successful spawning, but would be difficult to perform if males were of the same size as females [19,20,21,22]

The most conspicuous sexually dimorphic feature in loaches is the modified pectoral fin of males. Enlarged pectoral fins occur in Barbuccidae, Cobitidae and Nemacheilidae [23,24,25,26,27], often accompanied by thickening of certain fin rays, typically the first branched ray, occasionally the 2nd and 3rd (in Barbucca, Barbuccidae), the 4th to 7th branched rays (in Neoeucirrhichthys, Cobitidae) or by fusion of the seventh and eighth branched rays (in Lepidocephalichthys, Cobitidae) [7,25,26,28]. In Kottelatlimia (Cobitidae) the first branched pectoral-fin ray bears a dorsal serration [25]. Within one Cobitidae sublineage (the “Northern clade”), one or two pectoral-fin rays form ossified, plate-like extensions called ‘Canestrini-scale’ [27,29]. These character states most likely are directly related to the communication between spawning individuals. Tubercles on the pectoral fins are present in Balitoridae, Barbuccidae, Cobitidae, Gastromyzontidae, and Nemacheilidae [28,30,31], are sometimes present only in males, sometimes in both sexes (although sometimes more frequent in males than in females), and might serve two different functions, one related to spawning and one to hydrodynamics. Other sexually dimorphic traits in loaches include the presence of a suborbital flap or groove in males of many Nemacheilidae species [32], as well as sex-related differences in pigmentation (in some Cobitidae [25] and Nemacheilidae [33]) and the presence of head tubercles in certain Nemacheilidae [24] and Gastromyzontidae [34]. Nevertheless, modifications of the pectoral fins represent the most widespread form of sexual dimorphism across loach families.

Tubercles are also a component of sexual dimorphism in Cyprinoidea, Catostomidae, and Gyrinocheilidae, where they may occur on the head, body, or fins (pectoral, anal, and caudal) and are often referred to as “spawning tubercles” [30]. Although exceptions exist, in non-loach taxa these structures are usually restricted to (or most concentrated on) the head region, whereas in most loach genera that bear tubercles, they are most prominent on the fins [30]. Enlarged pectoral fins and ossified fin structures are rare and scattered among non-loach cypriniforms.

Despite the widespread occurrence of sexually dimorphic pectoral fins among loach families, Nalbant [35] argued that sexual dimorphism was absent in the common ancestor of loaches. His conclusion was based solely on the assumed lack of sexual dimorphism in Botiidae, which he considered the most basal loach family. Consequently, Nalbant [35] proposed that sexual dimorphism evolved within loaches only after the divergence of Botiidae. Indeed, molecular phylogenies later supported the assumption that Botiidae represent the most basal loach family [2,4,9,10,36].

Here, we demonstrate that sexual dimorphism is present and widespread within the family Botiidae, map our findings onto recently published phylogenetic reconstructions of Cypriniformes, and discuss the implications for interpreting sexual dimorphism as a potential synapomorphy of loaches.

2. Materials and Methods

An overview of the analysed species and specimens, their geographic origin, and the deposition of voucher specimens is provided in Table 1. Specimens were obtained either from scientific collections or the ornamental fish trade and were fixed in 10% formalin before transfer to 70% ethanol for long-term storage, or fixed and stored directly in 96% ethanol. Voucher specimens are deposited in the collections of the Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics, Liběchov, Czech Republic (IAPG), the Shanghai Museum of Natural History, Shanghai, PR China (SMNH), and the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore, Singapore (ZRC).

Table 1.

Overview about the analysed species, the number, sex and body size of specimens, their geographic origin and accession numbers.

In total, 19 species of Botiidae were examined for the presence of sexual dimorphism. The complete species list includes Ambastaia nigrolineata (Kottelat & Chu, 1987), A. sidthimunki (Klausewitz, 1959), Botia almorhae Gray, 1831, B. striata Narayan Rao, 1920, Leptobotia bellacauda Bohlen & Šlechtová, 2016, L. guilinensis Chen, 1980, L. microphthalma Fu & Ye, 1983, L. taeniops (Sauvage, 1878), L. tchangi Fang, 1936, Parabotia fasciatus Guichenot, 1872, Sinibotia longiventralis (Yang & Chen, 1992), S. pulchra (Wu, 1939), S. robusta (Wu, 1939), S. superciliaris (Guenther, 1892), S. zebra (Wu, 1939), Syncrossus berdmorei Blyth, 1860, Yasuhikotakia lecontei (Fowler, 1937), Y. modesta (Bleeker, 1864), and Y. morleti (Tirant, 1885); however, only species exhibiting sexual dimorphism are reported here. In some cases, the absence of observable dimorphic traits in other species was attributed to immature developmental stages, inadequate environmental conditions, or small sample sizes (unpublished data). The reduced dataset comprises 133 specimens representing eight species across three genera.

Sex was determined by gonadal inspection, and only specimens with developed or developing gonads were included in the analysis. Visual inspection and photographic documentation of morphological details were conducted using an Olympus SZX7 stereomicroscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a uEye camera. All measurements and counts follow Kottelat [32]. Standard length and 26 morphometric characters and five fin-ray counts (following Kottelat [32]) were measured point-to-point using digital callipers to the nearest 0.1 mm in a subsample of each species. From these measurements, characters indicative of sexual dimorphism were selected. Standard length and dimorphic characters were subsequently measured for all specimens. For each sexed adult specimen, relative fin measurements (pectoral-, anal-, and pelvic-fin length expressed as a percentage of standard length) were calculated. These values were visualized as scatterplots using the ggplot2 package [37] in R v. 4.2.3 [38].

Pigmentation patterns on the body, head, and fins, as well as the shape of genital papillae, were compared between males and females by visual inspection, using the above-mentioned stereomicroscope when necessary.

3. Results

For each species, morphometric measurements and visual observations were compiled into separate male and female datasets. Of the 26 morphometric characters measured, only pectoral fin length, ventral fin length, and anal fin depth differed consistently between sexes. Rather than applying any statistical tests to prove a significant difference between sexes we used the conservative approach of accepting only characters as sexually dimorph, when no overlap of the ranges existed between male and female values. In several gravid females, abdominal swelling caused shifts in some morphometric characters (e.g., body depth, body width, pre-anus and pre-anal distances). These shifts were not considered secondary sexual dimorphism, but rather as consequences of primary sexual organ development.

Across all analysed species there was a slight tendency that the largest specimen was a female, but the size of the largest male usually reached 90% of the largest female’s size. Therefore the species of Botiidae in our investigation do not display a sexual dimorphism in body size as in Cobitidae (maximum female length >140% of maximum male length in some species of Cobitis and Misgurnus). Detailed visual inspection revealed no sexual dimorphism in the number of fin rays, pigmentation patterns, mouth size or structure, shape of the genital papillae, or the presence of suborbital flaps or head/body tubercles. However, in certain species, tubercles were present on the pectoral fins of males only, but absent in females. Therefore, subsequent analyses focus on the two characters showing clear sexual dimorphism: fin length and the presence of pectoral-fin tubercles. Sexual dimorphism was observed in eight species across three genera: Leptobotia bellacauda, L. guilinensis, L. microphthalma, L. taeniops, L. tchangi, Parabotia fasciatus, Sinibotia pulchra, and S. robusta (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative fin sizes and presence of tubercles on the pectoral fin of males for the eight species of Botiidae with sexually dimorphic fin size and tubercle presence.

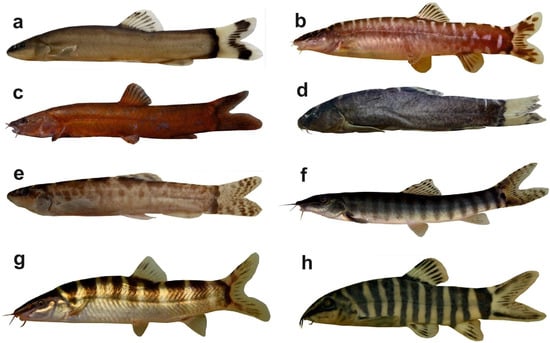

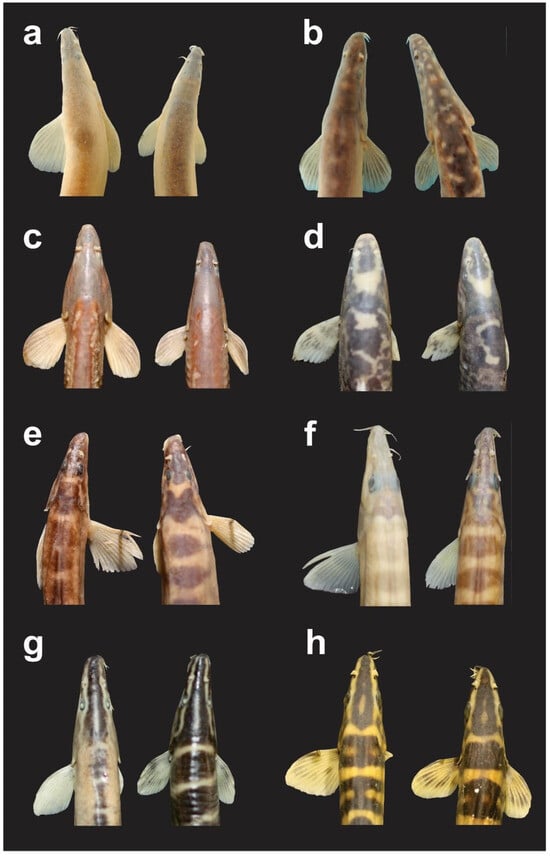

In all eight species, males exhibited longer pectoral fins than females, a pattern present in species with relatively small fins (e.g., L. bellacauda, 10.7–15.9% SL) as well as those with relatively large fins (e.g., S. robusta, 18.5–24.8% SL). Additionally, males of L. guilinensis and L. tchangi had larger pelvic fins than females, and males of L. microphthalma had larger anal fins (Table 2 and Table 3, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Results of ANOVA analyses comparing the length of fins between the sexes. All analyses showed that the difference between males and females are highly significant.

Figure 2.

Different size of pectoral fin as sexual dimorphism in eight species of Botiidae. (a) Leptobotia bellacauda, sexual dimorphism; SNHM 20160221-20160224, paratypes, left male 70.7 mm SL, right female 64.6 mm SL; (b) Leptobotia guilinensis, left male 69.8 mm SL, right female 69.2 mm SL; (c) Leptobotia microphthalma left male 73.7 mm SL, right female 70.7 mm SL; (d) Leptobotia taeniops, left male 80.3 mm SL, right female 77.1 mm SL; (e) Leptobotia tchangi, left male 66.1 mm SL, right female 70.2 mm SL; (f) Parabotia fasciatus, left male 96.8 mm SL, right female 90.8 mm SL; (g) Sinibotia pulchra, left male 76.8 mm SL, right female 71.7 mm SL; (h) S. robusta, left male 57.8 mm SL, right female 56.7 mm SL.

Figure 3.

Scatterplots illustrating sexual dimorphism based on morphometric measurements. (a) Relative pectoral-fin length across species with available data. (b) Relative anal-fin depth and (c) pelvic-fin length in the species where these characters are present. Each point represents a single sexed adult specimen (males in purple, females in orange). Green highlighting on the fish icons indicates the fin which is addressed in each graph.

Although pectoral fin length differed between sexes, fin shape remained consistent: male fins were morphologically similar to female fins, with no differences in fin-ray number, pigmentation, or ray modifications such as thickening or prolongation, as observed in some species of the families Cobitidae and Nemacheilidae. Most analysed Botiidae exhibited radial skin folds on the dorsal side of the pectoral fins in both sexes; we will refer to them as “dorsal fin ridges”. These ridges were composed from a skin fold filled by (most likely) fat cells, and appeared darker and thicker than the fin membrane. They were anchored along the dorso-posterior margin of most pectoral-fin rays (Figure 4). Dorsal fin ridges occurred along the last two unbranched and first 5–7 branched rays, decreasing in thickness toward posterior rays. Their size and prominence varied, increasing with specimen size regardless of sex. Well-developed ridges extended along most of the fin-ray length, broadest at mid-length, and sometimes covered the interspace between adjacent rays. In L. bellacauda, the ridges were broad, flat, and oriented dorso-posteriorly, similar as in the nemacheilid genus Pteronemacheilus [39] resembling automotive spoilers; it is likely that they have a hydrodynamic function.

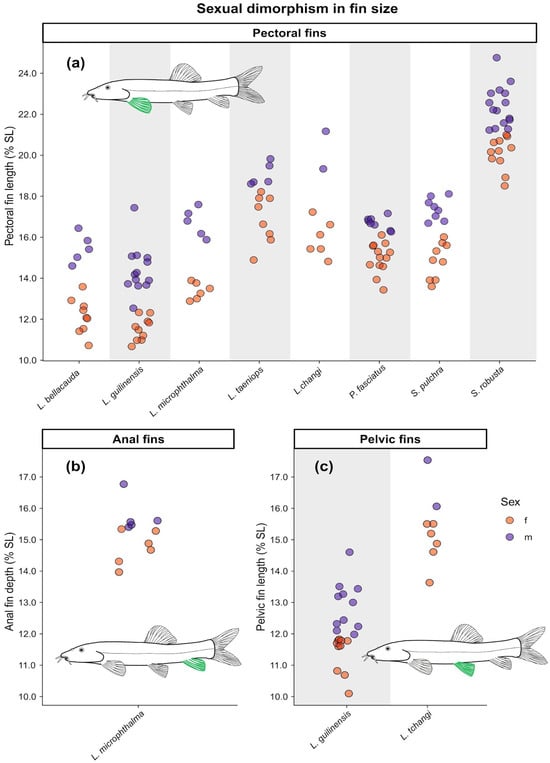

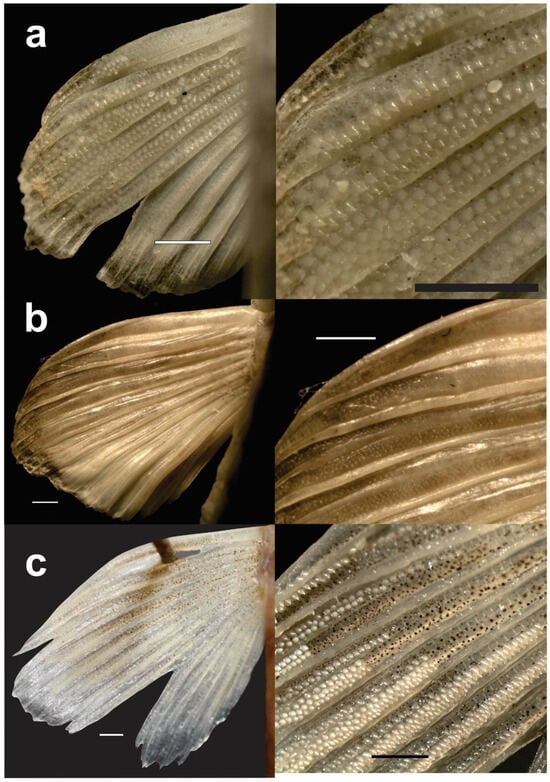

Figure 4.

Presence of tubercles on the pectoral fins of adult males as sexual dimorphism in three species of Leptobotia. Left: left pectoral fin in dorsal view, right: enlargement; scale bars 1 mm. (a) Leptobotia bellacauda; (b) Leptobotia microphthalma; (c) Leptobotia tchangi. Females without tubercles.

In males of L. bellacauda, L. microphthalma, and L. tchangi, tubercles were present on the dorsal surface of the pectoral fins but absent in females, constituting a sexually dimorphic character. Tubercles were associated with the last two unbranched rays and the first 4–7 branched rays. They had a round base, conical lateral profile, and pointed tip, sometimes sharp, sometimes blunt. In L. microphthalma, tubercles were fewer (up to ~500 per fin) and smaller (18–50 μm diameter at base), often confined to the midline of rays. In L. bellacauda and L. tchangi, tubercles were more numerous (up to several thousand per fin) and larger (50–120 μm diameter at base), with distinct distribution patterns: on the dorsal surface of the two unbranched and first branched rays, and on the dorsal surface of the dorsal fin ridges in subsequent rays. Their abundance, size, and distribution varied among specimens, generally increasing with male size and gonadal development. In L. tchangi, two small males with only slightly developed gonads lacked tubercles, whereas larger males with mature gonads displayed numerous tubercles.

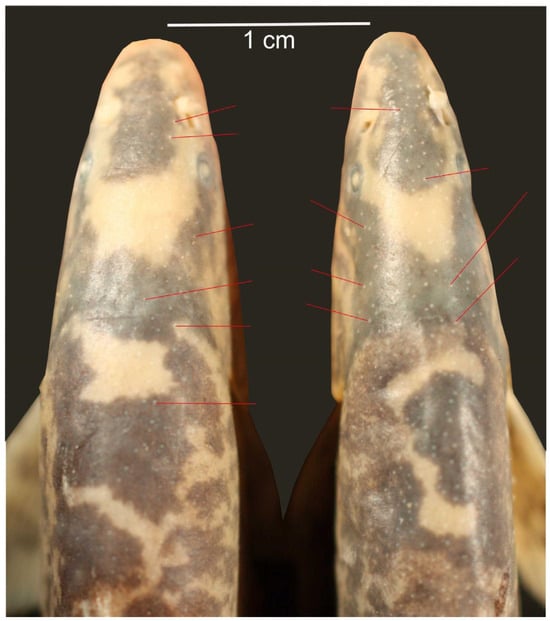

A different type of tuberculation was observed in some S. pulchra and L. taeniops specimens, consisting of numerous very small tubercles on the dorsal parts of head and body (Figure 5). However, these tubercles occurred equally in males, females, and juveniles and therefore do not represent a sexual dimorphism.

Figure 5.

Tubercles (some are indicated by red lines) on the dorsal side of head and body are present in both sexes in Leptobotia taeniops. Left male IAPG A8563, 80.0 mm SL, right female IAPG A8564, 75.1 mm SL. Since tubercles are present in both sexes, they do not represent a character of sexual dimorphism.

4. Discussion

Until now, no sexual dimorphism had been reported in Botiidae. The present study demonstrates that Botiidae exhibit morphometric and structural sexual dimorphism, manifested as enlarged pectoral, pelvic, and anal fins, as well as tubercles on the dorsal surface of the pectoral fins.

The eight genera of Botiidae belong to two well separated clades, classified as subfamilies: the diploid Leptobotiinae includes the genera Leptobotia and Parabotia and the tetraploid Botiinae with the genera Ambastaia, Botia, Chromobotia, Sinibotia, Syncrossus and Yasuhikotakia [2,3,35]. Despite the limited number of species for which enough mature specimens were available, our results already show that enlarged pectoral fins in males occur in at least three genera and, importantly, in both subfamilies. This finding demonstrates that this type of sexual dimorphism is widespread across Botiidae, rather than being restricted to a single genus or subfamily, and suggests that it represents an ancestral character of the family. The absence of this trait in some species likely reflects secondary loss. During the investigations for this study, enlarged pectoral fins in males were also noted in additional species (Botia striata, Sinibotia longiventralis, S. superciliaris, Ambastaia sidthimunki, and A. nigrolineata), but due to the low number of available ripe specimens these species were not included into the present dataset. Further investigations are likely to reveal additional instances of sexual dimorphism in other Botiidae species and genera.

In contrast, tubercles on the dorsal surface of the pectoral fins were observed exclusively in species of the genus Leptobotia. Further investigations of more species will show if it really is a specific trait of this genus or if it is an artefact of the limited material in the present study.

Nalbant [35] previously assumed that Botiidae lacked any sexual dimorphism, using this premise to postulate that the common ancestor of loaches did not exhibit sexual dimorphism. Our results demonstrate that this assumption was incorrect. Mapping the known instances of sexual dimorphism in loaches onto a cladogram derived from molecular phylogenetic studies (Figure 6) shows that pectoral-fin sexual dimorphism occurs across multiple loach families, including the basal Botiidae. We therefore postulate that the presence of a sexual dimorphism of the pectoral fins is a shared character of loaches, and that the common ancestor likely possessed enlarged pectoral fins in males, potentially accompanied by tubercles on the first branched fin rays.

Figure 6.

Phylogeny of Cypriniformes with focus on loaches (after Bohlen and Šlechtová, 2009; Chen et al., 2009; Stout et al., 2016 [4,9,36]) following the taxonomy proposed by Kottelat (2012) [3]. The presence of the two synapomorphic characters of loaches discussed in the present study (enlarged pectoral fins in males and tubercles on pectoral fins in males) are mapped.

Comparisons with non-loach Cypriniformes highlight distinct patterns. In most Catostomidae, tubercles occur on the head, dorsal body, or anal and lower caudal fins (e.g., Ictiobus, Catostomus, Moxostoma, Hypentelium, Minytrema) [30,40,41,42]. Pectoral-fin tubercles are rare, occurring in only a few species. For example, in Cycleptus elongatus (Lesueur, 1817), tubercles cover the head, body, and all fins, including ventral surfaces [43]. In Moxostoma rupiscartes Jordan & Jenkins, 1889, M. robustum (Cope, 1870), and Chasmistes brevirostris (Cope, 1879), a few tubercles occur on the pectoral fins, but most are located on the pelvic, anal, and caudal fins [40]. Overall, in Catostomidae, tubercles are concentrated on the head, body, and anal fin, rarely on the pectoral fin. In loaches, by contrast, tubercles are primarily located on the pectoral fins and occasionally on the head (e.g., Barbatula, Barbucca, Triplophysa). In some Catostomidae also the shape of the pelvic fin differs between sexes [44], but we are not aware about differences in pectoral fin.

In Gyrinocheilidae, breeding tubercles occur on the snout and head of adult males [12,30], but fin tubercles or sexually dimorphic fin sizes have not been reported.

In the extremely diverse Cyprinoidea, a huge number of characters have evolved into sexually dimorphic traits, including fin size and the presence of breeding tubercles. In the males of many Cyprinoids, both the paired and the unpaired fins are slightly to significantly larger than the fins of females [45]. The unpaired fins are especially richly ornamented and enlarged in species where males conduct lateral display to females or rivals [46,47,48]. An enlargement of all fins in one sex is evolutionarily simply reached by a small change in the developmental pathways of androgen-dependent fin ray growth control [49], as evidenced by the repeated parallel establishment in ornamental forms of fishes. The enlargement of the pectoral fin is in such cases only a by-product of the general fin enlargement, while in loaches the enlargement regards specifically the pectoral fin only. Species where only the pectoral fin is enlarged in male seem to be rare among Cyprinoidea, at least we did not find any such case in the scientific literature. Closest might come cases like Enteromius thespesios [50] and Dawkinsia singhala [51]. However, it does represent a rare case, not the general rule as in loaches. Breeding tubercles are also widespread in Cyprinoidea and a variety of tuberculation patterns have been described [23,47,52,53,54]). These studies reveal the tendency that breeding tubercles in Cyprinoidea are generally concentrated on the head, occasionally extending to the trunk or paired fins, with the largest and most robust tubercles consistently on the head, while the pectoral fins bear a comparably small amount of tubercles. We are not aware about any species exhibiting tubercles exclusively on the pectoral fins. It is likely that such cases exist in the vast diversity of Cyprinoidea, but it does not represent a major trend among them.

These comparisons indicate that, in Cyprinoidea, Catostomidae, and Gyrinocheilidae, enlargement of the pectoral fin alone is at least rare, not the common rule; and tubercles are concentrated on the head and trunk, with the pectoral fins minimally involved. In loaches, the enlargement of the pectoral fin alone is the most common trait in sexual dimorphism; and tubercles are concentrated on the pectoral fins, with the head and body rarely affected. Thus, the key synapomorphy of loaches is not the presence of enlarged fins and tubercles per se, but the restriction of enlargement to the pectoral fin and the concentration of tubercles on the pectoral fins. Together, these two character states distinguish loaches from all other Cypriniformes.

5. Conclusions

This study documents the first occurrence of secondary sexual dimorphism in Botiidae, showing that males of eight species across three genera have enlarged pectoral fins—and in some cases additional enlarged pelvic or anal fins or pectoral-fin tubercles. Because these features match the sexually dimorphic fin structures found in other loach families, and since Botiidae represent the most basal family of loaches, our results rise the hypothesis that sexual dimorphism might have been present in the common ancestor of loaches. Thus, enlarged male pectoral fins would represent a previously unrecognised synapomorphy of the loach lineage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B. and V.Š.; methodology, J.B.; software, V.Š.; validation, J.B., T.D. and V.Š.; formal analysis, J.B., T.D. and V.Š.; investigation J.B. and T.D.; resources, J.B.; data curation, J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.; writing—review and editing, J.B., T.D. and V.Š.; visualization, V.Š.; supervision, J.B.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, J.B. and V.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by grants 13-37277 S and 19-18453S of the Czech Science Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This work was approval by Ethical Committee for the Welfare of Experimental Animals (Approval Code: 403/2023; Approval Date: 3 February 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank M. Endruweit, Z. Hang, F. Li, S. Li, K. Lim, F. Schäfer, I. Seidel, H.-H. Tan and K. Udomritthiruji for help with the specimens.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Nelson, J.S. Fishes of the World, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; 752p. [Google Scholar]

- Šlechtová, V.; Bohlen, J.; Tan, H.H. Families of Cobitoidea (Teleostei; Cypriniformes) as revealed from nuclear genetic data and the position of the mysterious genera Barbucca, Psilorhynchus, Serpenticobitis and Vaillantella. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2007, 44, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottelat, M. Conspectus cobitidum: An inventory of the loaches of the world (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cobitoidei). Raffles Bull. Zool. 2012, 26, 1–199. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, C.C.; Tan, M.; Lemmon, A.R.; Lemmon, E.M.; Armbruster, J.W. Resolving Cypriniformes relationships using an anchored enrichment approach. BMC Evol. Biol. 2016, 16, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirt, M.V.; Arratia, G.; Chen, W.J.; Mayden, R.L. Effects of gene choice, base composition and rate heterogeneity on inference and estimates of divergence times in cypriniform fishes. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2017, 121, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Armbruster, J.W. Phylogenetic classification of extant genera of fishes of the order Cypriniformes (Teleostei: Ostariophysi). Zootaxa 2018, 4476, 6–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, Y. Phylogeny and zoogeography of the superfamily Cobitoidea (Cyprinoidei: Cypriniformes). Mem. Fac. Fish. Hokkaido Univ. 1982, 28, 65–223. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, K.W. Osteology of the South Asian Genus Psilorhynchus McClelland, 1839 (Teleostei: Ostariophysi: Psilorhynchidae), with investigation of its phylogenetic relationships within the order Cypriniformes. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 163, 50–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, J.; Šlechtová, V. Phylogenetic position of the fish genus Ellopostoma (Teleostei: Cypriniformes) using molecular genetic data. Ichthyol. Explor. Freshw. 2009, 20, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, K.; Sado, T.; Mayden, R.L.; Hanzawa, N.; Nakamura, K.; Nishida, M.; Miya, M. Mitogenomic Evolution and Interrelationships of the Cypriniformes (Actinopterygii: Ostariophysi): The first evidence toward resolution of higher-level relationships of the world’s largest freshwater fish clade based on 59 whole mitogenome sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 2006, 63, 826–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V.H. Fishes of the World, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; 707p. [Google Scholar]

- Rainboth, W.J. Fishes of the Cambodian Mekong. In FAO Species Identification Field Guide for Fishery Purposes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996; 265p. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.H.; Lim, K.K.P. A new species of Ellopostoma (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Balitoridae) from Peninsular Thailand. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2002, 50, 453–457. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen, J.; Li, F.; Šlechtová, V. Phylogenetic position of the genus Bibarba as revealed from molecular genetic data (Teleostei: Cobitidae). Ichthyol. Explor. Freshw. 2019, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, B.; Singh, Y.L. Redescription of Neoeucirrhichthys maydelli (Teleostei: Cobitidae) from Brahmaputra drainage, Assam, Northeastern India. Rec. Zool. Surv. India 2023, 123, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.R. Quintabarbates bicolor, a new genus and species of cobitid Fish from the Middle Chindwin Basin in Myanmar. Int. J. Ichthyol. 2020, 26, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bănărescu, P. Zoogeography of Fresh Waters, Vol. 2: Distribution and Dispersal of Freshwater Animals in North America and Eurasia; AULA: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1992; 511p. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton, R.J.; Smith, C. Reproductive Biology of Teleost Fishes; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015; 496p. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen, J. Similarities and differences in the reproductive biology of loaches (Cobitis and Sabanejewia) under laboratory conditions. Folia Zool. 2000, 49, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen, J. First report on the spawning behaviour of a golden spined loach, Sabanejewia vallachica (Teleostei: Cobitidae). Folia Zool. 2008, 57, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen, J. Spawning marks in spined loaches (Cobitis taenia, Cobitidae, Teleostei). Folia Zool. 2008, 57, 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Morii, K.; Takakura, K.I. Reproductive behavior of endangered spined loach Cobitis magnostriata in the field. J. Ethol. 2022, 40, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buj, I.; Šanda, R.; Marčić, Z.; Ćaleta, M.; Mrakovčić, M. Sexual dimorphism of five Cobitis species (Cypriniformes, Actinopterygii) in the Adriatic watershed. Folia Zool. 2015, 64, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šedivá, A. On the sexual dimorphism of stone loach Barbatula barbatula (Balitoridae). Folia Zool. 2001, 50, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelat, M.; Tan, H.H. Kottelatlimia hipporhynchos, a new species of loach from southern Borneo (Teleostei: Cobitidae). Zootaxa 2008, 1967, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottelat, M. Mustura celata, a new genus and species of loaches from northern Myanmar, and an overview of Physoschistura and related taxa (Teleostei: Nemacheilidae). Ichthyol. Explor. Freshw. 2018, 28, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbant, T. Studies on loaches (Pisces: Ostariophysi; Cobitoidea). I. An evaluation of the valid genera of Cobitinae. Trav. Mus. Hist. Nat. “Grigore Antipa” 1994, 34, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelat, M. Barbucca heokhuii, a new species of loach from central Borneo (Teleostei: Barbuccidae). Raffles Bull. Zool. 2025, 73, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlechtová, V.; Bohlen, J.; Perdices, A. Molecular phylogeny of the freshwater fish family Cobitidae (Cypriniformes: Teleostei): Delimitation of genera, mitochondrial introgression and evolution of sexual dimorphism. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2008, 47, 812–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, M.L.; Collette, B.B. 1970. Breeding tubercles and contact organs in fishes: Their occurrence, structure and significance. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1970, 143, 143–216. [Google Scholar]

- Freyhof, J.; Serov, D.V. Review of the genus Sewellia with description of two new species from Vietnam (Cypriniformes: Balitoridae). Ichthyol. Explor. Freshw. 2000, 11, 217–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelat, M. Indochinese nemacheilines. In A Revision of Nemacheiline Loaches (Pisces: Cypriniformes) of Thailand, Burma, Laos, Cambodia and Southern Viet Nam; Pfeil: München, Germany, 1990; 544p. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, K.W.; Kottelat, M. Physoschistura mango, a new miniature species of loach from Myanmar (Teleostei: Nemacheilidae). Raf. Bull. Zool. 2023, 71, 681–701. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, E. Bashimyzon cheni, a new genus and species of sucker loach (Teleostei, Gastromyzontidae) from South China. Zoosyst. Evol. 2024, 100, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbant, T.T. Sixty million years of evolution. Part one: Family Botiidae (Pisces: Ostariophysi:Cobitoidea). Trav. Mus. Hist. Nat. “Grigore Antipa” 2002, 44, 309–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-J.; Lheknim, V.; Mayden, R.L. Molecular phylogeny of the Cobitoidea (Teleostei: Cypriniformes) revisited: Position of enigmatic loach Ellopostoma resolved with six nuclear genes. J. Fish Biol. 2009, 75, 2197–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Bohlen, J.; Šlechtová, V. A new genus and two new species of loaches (Teleostei: Nemacheilidae) from Myanmar. Ichthyol. Explor. Freshw. 2011, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Branson, B.A. Observations on the Distribution of Nuptial Tubercles in Some Catostomid Fishes. Trans. Kans. Acad. Sci. 1961, 64, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, D.R.; Jenkins, R.E.; Armbruster, J.W. Description of the Apalachicola Redhorse (Catostomidae: Moxostoma). Zootaxa 2025, 5711, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.E.; Favrot, S.D.; Freeman, B.J.; Albanese, B.; Armbruster, J.W. Description of the Sicklefin Redhorse (Catostomidae: Moxostoma). Ichthyol. Herpetol. 2025, 113, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, R.J.; Jahn, L.A. Biological notes on blue suckers in the Mississippi River. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1980, 109, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.R. Sexual dimorphism of pelvic fin shape in four species of Catostomidae. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1988, 117, 600–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskar, B.A.; Sarma, D.; Das, D.N. Biometrics and Sexual dimorphism of Neolissochilus hexagonolepis (McClelland). Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2013, 1, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C.E.; Knight, C.L. Life-history traits of the bluenose shiner, Pteronotropis welaka (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae). Copeia 1999, 1999, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Reichard, M.; Jurajda, P.; Przybylski, M. The reproductive ecology of the Europeanan bitterling (Rhodeus sericeus). J. Zool. 2004, 262, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liao, T.Y.; Arai, R. Two new species of Rhodeus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae: Acheilognathinae) from the river Yangtze, China. J. Vertebr. Biol. 2020, 69, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, T.; Okamoto, K.; Ansai, S.; Nakao, M.; Kumar, A.; Iguchi, T.; Ogino, Y. Gene duplication of androgen receptor as an evolutionary driving force underlying the diversity of sexual characteristics in teleost fishes. Zool. Sci. 2024, 41, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katemo Manda, B.; Snoeks, J.; Decru, E.; Bills, R.; Vreven, E. Enteromius thespesios (Teleostei: Cyprinidae): A new minnow species with remarkable sexual dimorphism from the south-eastern part of the upper Congo River. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 96, 1160–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawickrama, K.B. Intraspecific variation in morphology and sexual dimorphism in Puntius singhala (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Ceylon J. Sci. Biol. Sci. 2009, 37, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahnelt, H.; Keckeis, H. Breeding tubercles and spawning behavior in Chondrostoma nasus (Telesotei: Cyprinidae): A correlation? Ichthyol. Explor. Freshw. 1994, 5, 321–330. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chen, X.Y.; Arratia, G. Breeding tubercles of Phoxinus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae): Morphology, distribution, and phylogenetic implications. J. Morphol. 1996, 228, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, J.J.; Sekharan, N.M. Sexual dimorphism in structures, size and shape of the cyprinid Nilgiri melon barb, Haludaria fasciata. Fish. Aquat. Life 2022, 30, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).