Abstract

Shellfish allergy is among the most common food allergies (FAs) worldwide and represents a severe immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated FA with tropomyosin functioning as the predominant pan-allergen. Current management of shellfish allergies is strictly palliative with allergen avoidance, underscoring the critical need for disease-modifying therapies. While conventional allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) approaches, namely oral and sublingual immunotherapies, demonstrate capacity for desensitization, more clinical applications are needed in the potential safety concerns and prolonged treatment durations. Innovative treatments, such as the design of modified shellfish allergens, DNA vaccine technologies, and nanoparticle-based delivery platforms such as virus-like particles (VLP), show efficacy and potential in inducing protective antibodies while promoting antigen-specific immune tolerance with reduced allergenic risks. These innovative approaches hint at a promising pathway in achieving safe, effective, and long-lasting clinical tolerance for shellfish allergy. This review describes the current perspectives on allergen immunotherapy regarding shellfish allergy and analyzes emerging therapeutic strategies poised to overcome these limitations.

1. Introduction

Food allergy is a chronic condition characterized by dysregulated Th2-mediated immune response to food proteins, triggering IgE-mediated mast cell and basophil activation leading to potentially life-threatening anaphylaxis [1]. Affecting ~10% of the population worldwide with a growing trend, food allergy represents a significant and escalating global health challenge [2]. Beyond acute reactions, food allergies impose a profound burden on the following: quality of life; nutrition; social activity; and heavy economic investments (USD 4.3 billion annually in the States as direct medical costs and EUR 4000 in Europe as indirect costs of food allergies [3]). Current management strategies focus on palliative care, such as allergen avoidance and epinephrine use, while food allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) has demonstrated efficacy in inducing desensitization to allergen proteins; it still faces significant hindrance, highlighting the crucial need for novel disease-modifying therapies. Furthermore, the rising research funding of food allergy, estimated at USD 22.8 billion annually in the U.S. alone [4], demands urgent investigation into scalable, cost-effective solutions.

2. Food Allergen-Specific Immunotherapies

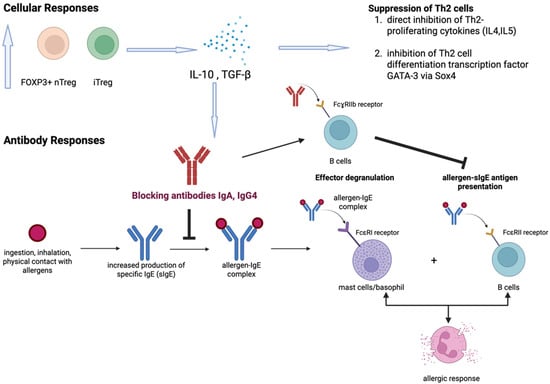

AIT aims to attain desensitization (a state of no clinical reactivity with continued allergen ingestion) and sustained unresponsiveness (the ability to tolerate after a period of avoidance) via a repeated and controlled exposure to the food allergen. While there is no standardized AIT protocol, comparing the efficacy of AIT based on the rates of desensitization and/or sustained unresponsiveness across studies has been difficult, as these outcome measures are dependent on the treatment duration, targeted threshold dose, and the duration of the avoidance period after AIT. For instance, 74.2% of children tolerated 300 mg of peanut protein after 16 months of oral immunotherapy (OIT), as reported by Blumchen et al. [5], but only 41.9% achieved desensitization when the threshold dose was defined as 4.5 g of peanut protein. Although the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated, current evidence suggests that AIT achieved its therapeutic effects via the action of both cellular and antibody responses [6] (Figure 1). Antibody response involves the upregulated production of protective blocking antibodies (mainly IgG4) by B cells [7]. These blocking antibodies compete with the allergen-specific IgE (sIgE) to inhibit downstream allergic reactions [8]. They also inhibit the sIgE-facilitated allergen presentation to T cells by blocking the FcɣRIIb receptors on B cells [9]. Besides antibody response, cellular responses also play a complementary but crucial role in exacerbating the therapeutic effects of AITs. The most significant cellular response involves the transition of the immune response from Th2 to Th1 [10] and also the increase in two subgroups of regulatory T (Treg) cells, namely transcription factor forkhead box P3 positive natural Treg (FOXP3+ nTreg) and inducible Treg (iTreg) cells [11]. Two major cytokines produced by Tregs are IL-10 and TGF-β, with the following core functions: (1) inducing B-cell isotype switching to IgG4 [12]; (2) suppressing the expression of FcεRI on mast cells to deactivate the mast cells [13,14]; and (3) suppressing Th2 cells by a series of mechanisms, including direct inhibition of Th2-proliferating cytokines (IL-4 and IL5) and CD28 co-stimulatory pathways in T cells [15], and induction of SOX4, which binds and inhibits the Th2 cell differentiation transcription factor GATA-3 [16].

Figure 1.

Overview of immune responses in allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT). The mechanism of AIT involves mainly cellular and antibody responses. The upregulated FOXP3+ nTreg and iTreg lead to increased production of two major cytokines, namely IL-10 and TGF-β, which facilitate the up-regulation of blocking antibodies and suppression of Th2 cells. Blocking antibodies (IgA, IgG4) then alleviate allergic response through (i) prevention of allergen-IgE complex formation and (ii) inhibition of allergen-sIgE antigen presentation through binding FcɣRIIb receptors on B cells.

Current AIT approaches vary by administration route, each with different mechanisms and clinical significance. OIT, being the most commonly practiced and the mainstream therapeutic option for food allergy treatment, involves a daily intake of escalating doses of the culprit allergen. OIT has shown the greatest efficacy in inducing desensitization of patients with FDA-approved options like Palforzia, producing a 60–80% desensitization rate towards peanut allergy [17]. Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) involves retaining the allergen at a low dose under the tongue for a period of time to induce a local immune response within the oral cavity to promote tolerogenic immune responses [3]. The sublingual mucosa has a rich population of CD103+ and langerin+ dendritic cells to promote tolerogenic responses and sometimes shares a similar modulatory mechanism as OIT, as young children can have difficulty spitting out the allergen. Epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) involves applying an epidermal patch that contains the allergen to the intact skin [18]. It takes advantage of activating the skin’s Langerhans cells and dendritic cells to induce potent and long-lasting Treg cell responses. Generally, SLIT and EPIT demonstrate more favorable safety profiles compared to OIT, as demonstrated in peanut allergy, mainly due to the lower administrating dose [3,19,20] and can minimize food aversion issues. Comparatively, OIT generates higher efficacy than SLIT and EPIT, but the sustained effects usually require continued OIT dosing.

With note of the significant safety risks of OIT, combination therapies integrating biologics such as omalizumab, dupilumab, and probiotics are being investigated. An FDA-approved anti-IgE monoclonal antibody, omalizumab, for example, has been shown to be a promising adjunct to OIT, with clinical trials suggesting a reduced anaphylactic risk, increasing threshold to allergen reactivity, decreasing duration of dose escalation, and facilitating multi-allergen OIT [21]. In peanut-allergic children, omalizumab pre-treatment increased desensitization rates to 67% vs. 7% with placebo-OIT [21,22]. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds IL-4 receptor-α, inhibiting both IL-4 and IL-13 production [22]. Similarly, it has been investigated as an adjuvant to OIT to suppress Th2 pathways, with decreased sIgE levels in peanut-allergic children of 40.7% in 16 weeks [22]. Trials combining probiotics Lactobacillus rhamnosus with peanut OIT (PPOIT) achieved sustained unresponsiveness in 82% of treated participants at 4 year follow-up, with participants more likely to continue consuming peanuts and showing fewer allergic reactions [23]. While pairing biologics as adjuvants to AIT can reduce the risks of adverse reactions and shift short-term desensitization into durable immune tolerance, it also poses significant limitations such as high cost, prolonged treatment duration, and paradoxical hypersensitivity reactions. More studies are necessary to ensure the safety of these adjuvants.

3. Shellfish Allergy

Shellfish allergy is among the most common food allergies worldwide and is part of the nine major food allergen sources responsible for over 90% of food allergy cases. Globally, shellfish allergy affects 0.5–3% of the general population with marked geographic variation [24,25]. In the United States, shellfish is the most prevalent food allergen, affecting 2.9% of the adult population, while in Europe the estimation ranges from 0.3% in Northern Europe to 10% in Southern Europe [26,27]. In Asia–Pacific regions, shellfish allergy is a major cause of severe allergic reactions, particularly in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Thailand [24]. Unlike milk or egg allergies, shellfish allergies often develop in late childhood to adolescence and tend to persist throughout life [28]. Shellfish allergy typically causes rapid-onset symptoms such as hives, swelling of the lips or throat, wheezing, and gastrointestinal distress, and in severe cases can lead to anaphylaxis—a life-threatening reaction [29].

Shellfish includes both crustaceans and mollusks, of which crustacean shellfish such as shrimp and crab are the most globally consumed and are the most extensively studied. Within this category, shrimp is identified as the most prevalent allergic shellfish, with crab ranking second in terms of allergenic prevalence [30]. To date, the major allergens of shrimp and crab have been officially curated by the WHO/IUIS Allergen Nomenclature Sub-Committee (Table 1). Tropomyosin serves as the major allergen in shrimp, unlike crab, where both tropomyosin and arginine kinase function as major allergens. Tropomyosin has been recognized as the major pan-allergen responsible for extensive cross-reactivity among crustaceans [31]. However, species-specific reactions occur due to subtle sequence and epitope variations in tropomyosin and other allergens, which can influence IgE binding and clinical cross-reactivity [32]. Beyond tropomyosin, additional allergens such as arginine kinase, myosin light chain, and sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein have been identified in shrimp and crab, contributing to the complexity of diagnostic interpretation and management strategies [33,34]. Moreover, while shellfish of the same taxonomic group share conserved allergenic components, interspecific variations in specific protein sequences and expression levels result in distinct species-specific allergen profiles. Recent proteomic and transcriptomic analyses of six widely consumed crab species revealed distinct allergen repertoires and interspecies differences. While tropomyosin and arginine kinase were conserved across species, novel allergens, such as malate dehydrogenase, were identified as king crab-specific [35]. Sequence similarity among crab allergens generally exceeded 68%, but species-specific epitopes were evident, underscoring the potential for selective clinical reactivity.

Table 1.

List of shrimp and crab allergens.

It is, however, noteworthy that the patterns of sensitization to shellfish allergens exhibit substantial differences between Asian and Western populations due to differences in dietary habits, environmental exposures, and allergen sources. Western populations show a higher prevalence of adult shellfish allergy with IgE responses mainly focused on tropomyosin, while Asian cohorts demonstrate broader sensitization profiles, including arginine kinase, myosin light chain, troponin C, and fatty acid-binding protein [36,37]. Additionally, cross-reactivity with house dust mites, cockroaches, and insect tropomyosin is another factor contributing to elevated shellfish sensitization in tropical Asian regions, whereas this is less pronounced in Western countries [38].

4. OIT and SLIT for Shellfish Allergy

Although the Global Allergy and Asthma Excellence Network (GA2LEN) recommends offering peanut OIT to children aged 4+ years with clinically diagnosed, severe, IgE-mediated peanut allergy and suggests OIT to children with hen’s egg or cow’s milk allergy to increase the threshold amount of allergen in the 2022 guidelines [39], publicly available clinical trials targeting shellfish OIT or SLIT are scarce.

With regard to OIT, only four published clinical trials [40,41,42,43] are available (Table 2). The general efficacy and safety of shellfish OIT are promising, with 87.5–100% of OIT subjects demonstrating tolerance after the treatment and only mild reactions and no anaphylaxis/systemic allergic reaction requiring beta-agonists and antihistamines being found. As compared to the conventional three-phase protocol in OIT, Marie et al. [42] explored the possibility of bypassing the up-dosing phase to increase the accessibility of OIT to hot zones of shrimp allergy and minimize healthcare costs from clinical staff and families. Supported by a previous study that shrimp has a higher threshold for reaction than other allergenic foods (eliciting a dose of mustard in 10% of the population is 1.3 mg compared to only 4% of the population reacting to 300 mg of shrimp protein) [44], the group proceeded directly to the maintenance dose phase by administering 300 mg of shrimp protein without the up-dosing phase and demonstrated that this low-dose OIT approach was safe. Andorf et al. [41], on the other hand, incorporated omalizumab in the first 16 weeks in a Phase 2 multi-centered multi-food-OIT trial (M-TAX study: NCT02626611). Out of 60 randomized multi-food-allergic patients, three of them were diagnosed with shrimp allergy with concurrent allergy to four other food allergens. These shrimp-allergic patients received shrimp OIT from week 8 to week 30, and all passed the 2 g shrimp protein food challenge at week 30. Upon successful desensitization, two patients were randomized to continue daily 300 mg shrimp protein OIT (active group) during week 30–36, while the remaining patient received blinded discontinuation (placebo). One patient from the active group and the patient from the placebo group passed the week 36 challenge and attained sustained unresponsiveness. However, the other patient from the active group did not proceed with the week 36 challenge. In another Phase 2 shrimp OIT trial (MOTIF study: NCT03504774) by Jiang et al. [43], 87.5% (7/8) of the per-protocol group tolerated the maximum cumulative dose (4043 mg of shrimp protein) at week 52. All patients who achieved desensitization also attained sustained unresponsiveness (4043 mg of shrimp protein) after 6 weeks of avoidance. It was reported that although adverse reactions were common during shrimp OIT, most were mild, and no epinephrine was required. Yet, the clinical outcome of shrimp OIT remained elusive with small sample sizes.

Table 2.

Summary of published OIT and SLIT studies for shellfish allergy.

In the context of SLIT for shellfish allergy, Refaat et al. [45] recruited 60 patients who were classified into three groups based on their clinical reactions (urticarial, rhinitis, and asthmatic) to shrimp. Crude shrimp extract from two shrimp species (Penaeus semisulcatus and Metapenaeus stebbingi) was administrated for up to 6 months. A significant reduction in allergic symptoms in daily life was found together with a declined sIgE response and heightened IgG4 blocking antibody level compared to placebo. While this study provides evidence on the induction of blocking antibodies, details regarding the randomization and dosing schemes and safety of the treatment were lacking, while no exit oral food challenge was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of SLIT. Another study by Theodoropoulou & Cullen [46] identified 66 patients who underwent shrimp SLIP by reviewing the charts of a Midwest Allergy-Immunology practice from January 2014 to June 2023. Commencing at 64 or 320 ng/dose based on their shrimp-IgE levels at screening (64 ng for >100 kU/L, 320 ng for <10 kU/L), dosage was gradually escalated weekly to quarterly until reaching 0.5 mg/dose three times per day over 6 to 48 months. Of the 18 patients who underwent the exit challenge, 61% (11/18) demonstrated desensitization when exposed to ≥42 g of shrimp. Seven patients developed localized reactions, and two patients continued SLIT while three patients were placed on SLIT and routine exposure to 12–20 g shrimp every other day. All these patients achieved desensitization on repeat challenge 6–9 months after the original challenge. Despite the seemingly positive clinical benefits, both studies did not detail the safety of the treatment.

5. Emerging Treatment Strategies for Shellfish Allergy

Nevertheless, existing AIT approaches still present significant clinical challenges. Firstly, OIT, SLIT, and EPIT require long-term dosing (at least one year), and continued daily dosing is necessary to sustain the clinical benefits. Secondly, studies have shown that patient age correlates with treatment efficacy, with suboptimal performance observed in older populations potentially due to lower adherence and immune system plasticity [47]. Thirdly, medical safety protocols and personnel are needed in case of adverse reactions for immediate on-site adjustments and individualized management. Lastly, these AIT regimens have strict logistical constraints, e.g., administration must occur in controlled clinical settings with continuous medical supervision due to the risk of anaphylaxis, limiting accessibility and increasing healthcare burdens. In the context of shellfish allergy, severe reactions such as anaphylaxis were found in murine models when native tropomyosin was administered, which highlights the potential safety problem from the high allergenic potency of native tropomyosin [48]. Given these concerns surrounding traditional AITs, they can significantly affect patient compliance negatively [49]. The EAACI guideline towards food allergy management suggests PPOIT and adjuvants require more research for a safer and broader application and underscores the need for an investigation into alternatives such as the integration of vaccination approaches in allergy treatments, which may open new doors to deliver more efficacious methods to combat allergies [3,47]. In the following sections, we will discuss alternative AIT approaches, including the use of modified shellfish allergens, DNA vaccines, and nanotechnologies, for shellfish allergy treatment.

6. Modified Shellfish Allergens for Treatment

The principle of hypoallergen builds upon the concept of an altered allergen that can be less allergenic than the native allergen and yet have the same immunogenicity. While multiple methods for hypoallergen synthesis are available, including gene editing [50,51,52,53,54], bacterial fermentation [55], irradiation [56], and enzymatic hydrolysis [55], the existing strategy for shellfish hypoallergen involves mainly gene editing of the IgE-binding epitope in tropomyosin (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hypoallergens of shrimp allergens.

The hypoallergenic construction of the shrimp allergen was first reported by Reese et al. [50] on Pen a 1 (tropomyosin) from Penaeus aztecus (brown shrimp) through mutating 12 positions spanning eight major epitopes that were deemed critical. One of the mutants, VR9-1, was found to have a 90–98% reduction in potency as indicated in the reduced release of allergen-specific mediator from humanized rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells, RBL30/25. But it is noted that the maximal release from RBL was similar between VR9-1 and native tropomyosin, suggesting critical epitopes and amino acid sites remain in this mutant. Extending the study to Metapenaeus ensis (shrimp), Wai et al. [51] generated two mutated forms of the shrimp tropomyosin Met e 1 through site-directed mutagenesis (MEM49) and epitope deletion (MED171) upon the identification of nine regions as the major IgE-binding epitopes. Both hypoallergens exhibit desirable features as indicated in the marked reduction in in vitro IgE reactivity and induction of mast cell degranulation, as well as the capacity to induce blocking IgG antibodies. Zhang et al. [52] proceeded to develop hypoallergen for oyster tropomyosin (Cra g 1) together with an in-depth investigation on related molecular mechanisms. Upon the generation of four hypoallergenic derivatives with significant reduction in IgE reactivity and effector responses (degranulation and secretion of allergic mediators including histamine, IL-4, Il-6, and TNF-α), it is discovered that they function by attenuating the FcεRI-mediated signaling cascades, suggesting potential candidates for epitope modifications/deletions.

While all the above studies focus on modifying/deleting the linear epitopes, Li et al. [53] attempted to explore the potential role of conformational epitopes in allergens where both types of epitope exist, namely Scy p 1 (tropomyosin) and Scy p 3 (myosin light chain). By eliminating the linear epitopes via reduction (red/alk derivative) and conformational epitopes through gene editing (mtALLERGEN), respectively, each derivative of the above two allergens was made. With a drastic conformational change, the red/alk form was only recognized by 13% of the 29 crab-sensitized patients compared to 62% recognition for mtALLERGEN with slight structural change by modifying the conformational epitopes. The fact that hypoallergen without the linear epitopes may be a more viable candidate for immunotherapy than the conformational epitopes mutant is further illustrated in the lower IgE-binding capacity and basophil activation in the red/alk form.

7. DNA Vaccine Technology for Shellfish Allergy Treatment

The idea of a DNA vaccine that emerges involves the injection of DNA sequence encoding the allergen and rely on receivers’ own replication. Current studies suggest two major immuno-modulatory mechanisms of DNA vaccines: (a) the triggering of Th1-dominant while suppressing Th2-dominant immune responses [57] is achieved by the expression of IL-12 (Th1 cytokine) and the increased frequency of Treg, respectively and (b) increasing the production of allergen-specific IgG antibodies [58] after vaccine injection to block allergen-IgE interactions and engage inhibitory receptors such as FcγRIIb [59] on effector cells. Published studies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

DNA vaccines targeting at shellfish allergy.

Pioneered by Wai et al. [60], the group introduced two DNA vaccines, pMEM49 and pMED171, intradermally to a murine model upon their success in developing the respective hypoallergens in the previous study. Through the induction of Treg cells, efficacy was demonstrated phenotypically (decreased anaphylactic symptoms and intestinal inflammation) and immunologically (down-modulated tropomyosin-specific IgE levels, intestinal Th2 cytokines, and inflammatory cell infiltration). Subsequently, similar studies using different routes of administration and molecular mechanisms were performed. Kubo et al. [61] introduced the multivalent Lit-LAMP-DNA vaccine epicutaneously into a murine model and successfully suppressed anaphylactic reactions and mast cell activation together with elevated antigen-specific IgG2a production. Smeekens et al. [58], on the other hand, explored transcutaneous gene-gun DNA vaccines with the major shellfish allergens, namely sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein, troponin, tropomyosin, arginine kinase, and myosin light chain. In this study, the necessity of IL-12 was further explored through the injection of vaccine with (IL-12+) or without (IL-12−) IL-12 co-expression. Surprisingly, despite an increase in shrimp-specific IgG found in all tested subjects injected with the IL12+ and IL-12− vaccines, the highest production of IgG was observed in the IL-12− vaccine, which questions the necessity of IL-12 co-expression.

While the above studies show promising results, safety problems regarding the route of administration remain. As seen from the above studies, three different injection approaches were adopted, namely intradermal, epicutaneous, and transcutaneous. Since this involves either localized or systemic reaction controlled by different subsets of immune cells, future studies should focus on the trade-off between safety and efficacy while using these three methods.

8. Nanoparticle Technology for Shellfish Allergy Treatment

Nanoparticles (NP) can be classified into the following three main groups: lipid-, polymeric-, and inorganic-based. Lipid-based NPs are the most common type to be utilized in current FDA-approved nanomedicines, since they provide a wide range of advantages, such as their high biocompatibility, bioavailability, and easy surface modification [62]. Regardless of this, different components of NPs, such as NP size, shape, surface charge, and surface coating, can all be customized in order to reach an optimal targeted effect [63]. Thus, the highly engineerable nature of NPs allows the possibilities for allergy treatments to be precise.

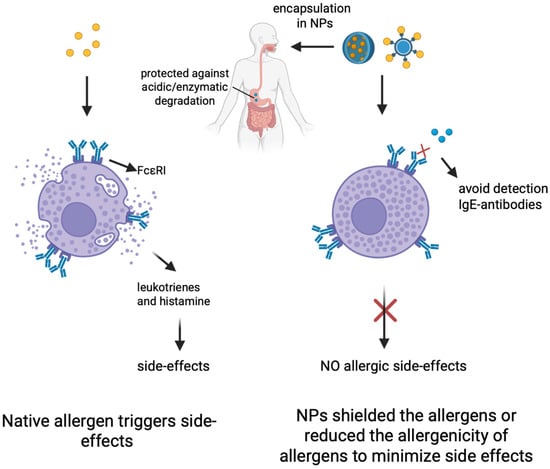

One possible mechanism of NPs aiding AIT is the encapsulation of allergens in NPs. Encapsulation can protect allergens from enzymatic or acidic degradation in the body, especially in oral immunotherapy, where allergens undergo highly acidic environments in the gastrointestinal tract [64] (Figure 2). Therefore, encapsulation can ensure high local concentrations of allergen for increased effect [65]. Another possible mechanism of transportation involves surface coating of the cargo. In other words, NPs may shield allergens from IgE detection on the surfaces of mast cells through IgE cross-linking. In such a manner, NPs are able to evade side effects of mast cell activation, which are typical of traditional AITs [66].

Figure 2.

Illustrations of the nanoparticle technology. Nanoparticles (NPs) can shield the allergens to protect against acid/enzymatic degradation for OIT and also reduce the allergenicity of allergens to minimize allergic side effects. Created in BioRender (https://BioRender.com/sgp9c1c).

The most studied NPs specifically for AIT are biodegradable, which includes synthetic and natural polymers and liposomes and virus-like particles. Inorganic NPs, which are non-biodegradable, are not as commonly used as they have insignificant influence on allergic inflammations; however, they may act as immunomodulatory agents [67]. Out of all the NPs available, Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)—a type of synthetic polymer—is the most studied NP [67] due to its highly biodegradable polymer backbone, which allows high bioavailability, controlled release, and a favorable safety profile [62].

Virus-like particles (VLPs), unlike traditional nanoparticles, are self-assembling and biologically produced protein-based nanoparticles that have become a powerful NP in medical applications such as vaccines and immunotherapies in food allergy treatments. VLPs mimic the morphology and structural organization of virus particles but are non-infectious due to the absence of viral genetic material. VLPs are typically composed of one or more layers of protein coats that are assembled into highly ordered and repetitive structures that range in different sizes from 20 to 200 nm and can be efficiently recognized by pattern recognition receptors to elicit potent immune responses [63]. VLPs also offer a safer utilization profile, as they do not possess the viral genomes, thus eliminating the potential for replication and genetic integration within the target cell. In terms of food allergy treatment, allergens can be conjugated on the surface of the VLP, allowing B cell activation to produce fast-acting inhibitory IgG antibody, therefore suppressing the degranulation process and preventing anaphylactic response. Their immunogenicity, safety profile, and ability to precisely display antigens make them great candidates for food allergy treatments.

Studies demonstrated that conjugating major peanut allergen Ara h 2 to engineered Cucumber mosaic virus VLP (forming CuMVTT-Ara h 2) was highly effective in both naive and peanut-sensitized murine models. Immunization with this construct allowed the induction of IgG response, suppression of IgE, and provided protection against anaphylaxis upon intravenous injection of Ara h 2, as measured by body temperature [64]. Building upon this strong preclinical efficacy and safety, VLP peanut has proceeded onto human clinical trials. Human trials of CuMVTT-Ara h 2 have confirmed the efficacy of VLP in peanut allergy immunization, presenting a shift in pro-allergenic Th2 response towards anti-inflammatory Th1 and Treg cells and inducing IL-10 B regulatory cells critical for long-term tolerance and generation of protective blocking IgG antibodies. Moreover, it was also 20 times less potent than natural Ara h 2 allergen at activating basophil and histamine release, thus making it a safer therapeutic option for treatment [64]. While the study remains early and small-scale, the consistent results underscore the immunogenicity and safety of VLP treatment in food allergy treatment, validating its potential for long-term treatment and studies.

VLPs were also tested on shrimp allergens despite being in their infancy. Recently, a study combined AP205-based VLP with Pen m 1 allergen under the SpyTag/SpyCatcher conjugation system, which has shown reduced allergenicity with an induction of Th1-mediated IgG2a production in murine models [65]. Another study assembled various VLPs by designing eight peptides (P1-P8) derived from shrimp tropomyosin and conjugating them with their corresponding carrier—hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBcAg) [66]. In comparison to native tropomyosin, the peptides, in general, showed at least a 3.5-fold decrease in IgE binding affinity, and two specific peptide-conjugated HBcAg-VLPs (VLP-P1 and VLP-P2) showed at least a 1.5-fold increase in tropomyosin-specific IgG2a level [62]. The results for IgE and IgG2a point towards decreased allergenicity and therefore provide promising indications for improved treatment that is more potent and safe. Results regarding VLP tests on shrimp allergens demonstrate a similar induction of IgG2a blocking antibodies and promotion of Th1-mediated immune response as VLP-peanut. While still early, VLP technology represents a highly promising next-generation therapeutic approach for shrimp allergy and other food allergies. By harnessing the immune system’s ability to generate protective blocking antibodies, it has the potential to provide a safe and effective disease-modifying treatment for individuals suffering from potentially life-threatening allergies.

9. Limitations and Future Directions

Currently there are no FDA-approved therapies for shellfish allergy. Despite continuous effort directed at developing shellfish-specific AIT, the efficacy and safety of shellfish AIT remain elusive due to the limited number of studies (mostly abstracts with limited details on study protocol and findings), small cohort sizes, and the lack of placebo control groups for comparison. Different threshold doses and treatment durations were adopted across studies that render direct comparison of the efficacy in achieving desensitization and sustained unresponsiveness. Shellfish AIT can also be complex due to the high molecular complexity of shellfish allergens. Shellfish allergies are known to be elicited by a diverse range of allergens, including tropomyosin, arginine kinase, myosin light chain, sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein, troponin C, and fatty acid-binding protein [68], as opposed to peanut/milk/egg allergies that are caused by a major allergen (e.g., Ara h 2 for peanut, casein for milk, and ovomucoid for egg) [69]. Furthermore, certain pan-allergens like tropomyosin and arginine kinase are highly conserved across edible shellfish [70], but shellfish-specific allergy is common partly due to the diversity of IgE-binding epitopes across different shellfish species. Moreover, the processing methods can also affect the composition of allergens, as some important allergens, such as arginine kinase, are susceptible to heat. These thus make the diagnosis and so treatment of shellfish allergy challenging. Given these, it can be difficult to standardize the sources, concentration, and composition of OIT/SLIT agents in shellfish AIT.

As mentioned earlier in this review, the EAACI guideline towards food allergy management recommends research on the integration of vaccination approaches in allergy treatments. Though making remarkable progress in the past decade, AIT vaccines for shellfish allergy advancement to clinical trials have been very limited compared to peanut allergy, although the prevalence of shellfish allergy has been surpassing that of peanut allergy in pre-school children and specifically in the adolescent and adult populations [71,72]. Positive results for shellfish allergy AIT vaccines are only retrieved from murine experiments that are yet to be translated to human clinical trials.

In this review, we discuss various potential shellfish AIT strategies that are in the pipeline, including hypoallergens, DNA vaccines, and nanoparticles. The advancement of these platforms from pre-clinical trials to clinical application requires a concerted effort to understand the precise immunotherapeutic mechanism of these next-generation AITs, as well as their long-term efficacy and safety. Future directions for immunotherapeutic approaches to shellfish allergy should also focus on personalized medicine approaches to tailor treatment plans. Unlike many other food allergies like peanut allergy, where Ara h 2 represents the major allergen accounting for >90% of allergic reactions, the allergen repertoire of shellfish-allergic patients is highly heterogenic. As mentioned earlier, troponin C and fatty acid-binding protein are also major shrimp allergens alongside tropomyosin, and shrimp-allergic patients can be sensitized to multiple allergens. Species-specific shellfish allergies, such as differential clinical responses to different marine and freshwater shrimps or different edible crabs, further complicated the appropriate choice of shellfish and specific component(s) towards customizing treatment to maximize patient outcome. Precision diagnosis pinpointing specific shellfish allergen(s) responsible for the manifestation of allergic reactions of individual patients and a flexible vaccine platform to easily decorate shellfish allergens or their derivatives are pivotal for the development of next-generation therapies with maximal efficacy and safety but minimal risk for shellfish allergy.

10. Conclusions

Pre-clinical AIT vaccines for shellfish allergy present promising findings of modified allergens and the intrinsic immunomodulation property of immuno-modulatory carries like DNA vaccines and nanoparticles. They demonstrate a revolutionary way of food allergy management by inducing a higher sustained tolerance and reduced anaphylactic risk while lowering the cost and mitigating the time and labor investments of traditional AIT and biologics. By addressing the major limitations of traditional approaches, these emerging approaches offer a viable, safe, and cost-effective option to shellfish allergy therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and funding acquisition: C.Y.Y.W. All authors wrote, reviewed, and approved the published version of the review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (12230466), CUHK Direct Grant for Research (2025.077) and CUHK IdeaBooster Fund (IDBF24MED11) by the The Chinese University of Hong Kong and the research grant from The Hong Kong Institute of Allergy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this review.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIT | Allergen-specific immunotherapy |

| EPIT | Epicutaneous immunotherapy |

| FA | Food allergy |

| Foxp3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| GA2LEN | Global Allergy and Asthma Excellence Network |

| GuMVTT | Cucumber mosaic virus VLP |

| HBcAg | Hepatitis B virus-core antigen |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| OIT | Oral immunotherapy |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PPOIT | Probiotics with peanut OIT |

| sIgE | Allergen-specific IgE |

| SLIT | Sublingual immunotherapy |

| VLP | Virus-like particle |

References

- Pouessel, G.; Lezmi, G. Oral immunotherapy for food allergy: Translation from studies to clinical practice? World Allergy Organ. J. 2023, 16, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.W. Food allergies around the world. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1373110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggioni, C.; Oton, T.; Carmona, L.; Du Toit, G.; Skypala, I.; Santos, A.F. Immunotherapy and biologics in the management of IgE-mediated food allergy: Systematic review and meta-analyses of efficacy and safety. Allergy 2024, 79, 2097–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, A.T.; Ahlstedt, S.; Golding, M.A.; Protudjer, J.L.P. The Economic Burden of Food Allergy: What We Know and What We Need to Learn. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2022, 9, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumchen, K.; Trendelenburg, V.; Ahrens, F.; Gruebl, A.; Hamelmann, E.; Hansen, G.; Heinzmann, A.; Nemat, K.; Holzhauser, T.; Roeder, M.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Quality of Life in a Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Low-Dose Peanut Oral Immunotherapy in Children with Peanut Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 479–491 e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahiner, U.M.; Giovannini, M.; Escribese, M.M.; Paoletti, G.; Heffler, E.; Alvaro Lozano, M.; Barber, D.; Canonica, G.W.; Pfaar, O. Mechanisms of Allergen Immunotherapy and Potential Biomarkers for Clinical Evaluation. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamji, M.H.; Layhadi, J.A.; Scadding, G.W.; Cheung, D.K.M.; Calderon, M.A.; Turka, L.A.; Phippard, D.; Durham, S.R. Basophil expression of diamine oxidase: A novel biomarker of allergen immunotherapy response. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 913–921.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupinek, C.; Wollmann, E.; Valenta, R. Monitoring Allergen Immunotherapy Effects by Microarray. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2016, 3, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, N.R.; Smith, K.G. B cell inhibitory receptors and autoimmunity. Immunology 2003, 108, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebi Sozener, Z.; Mungan, D.; Cevhertas, L.; Ogulur, I.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C. Tolerance mechanisms in allergen immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 20, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvaro-Lozano, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Alviani, C.; Angier, E.; Arasi, S.; Arzt-Gradwohl, L.; Barber, D.; Bazire, R.; Cavkaytar, O.; et al. EAACI Allergen Immunotherapy User’s Guide. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31 (Suppl. S25), 1–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.A.; Freeman, A.F.; Nutman, T.B. IL-10 Indirectly Downregulates IL-4-Induced IgE Production by Human B Cells. Immunohorizons 2018, 2, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, G.; Ramirez, C.D.; Rivera, J.; Patel, M.; Norozian, F.; Wright, H.V.; Kashyap, M.V.; Barnstein, B.O.; Fischer-Stenger, K.; Schwartz, L.B.; et al. TGF-beta 1 inhibits mast cell Fc epsilon RI expression. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 5987–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy Norton, S.; Barnstein, B.; Brenzovich, J.; Bailey, D.P.; Kashyap, M.; Speiran, K.; Ford, J.; Conrad, D.; Watowich, S.; Moralle, M.R.; et al. IL-10 suppresses mast cell IgE receptor expression and signaling in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 2848–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.; Verhagen, J.; Blaser, K.; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Mechanisms of immune suppression by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-beta: The role of T regulatory cells. Immunology 2006, 117, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorelik, L.; Fields, P.E.; Flavell, R.A. Cutting edge: TGF-beta inhibits Th type 2 development through inhibition of GATA-3 expression. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 4773–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boechat, J.L.; Sousa-Pinto, B.; Delgado, L.; Silva, D. Biologicals in severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: Translation to clinical practice while waiting for head-to-head studies. Rhinology 2023, 61, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, J.A.; Kim, E.H.; Chinthrajah, R.S.; Wood, R.A. Treatment for food allergy: Current status and unmet needs. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Weaver, B.T. Preclinical evaluation of alternatives to oral immunotherapy for food allergies. Front. Allergy 2023, 4, 1275373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Nagakura, K.I.; Yanagida, N.; Ebisawa, M. Current perspective on allergen immunotherapy for food allergies. Allergol. Int. 2024, 73, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, A.; Moore, L. Omalizumab for the Treatment of Multiple Food Allergies. Pediatrics 2024, 154 (Suppl. S4), S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Rijst, L.P.; Hilbrands, M.S.; Zuithoff, N.P.A.; de Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Knulst, A.C.; Le, T.M.; de Graaf, M. Dupilumab induces a significant decrease of food specific immunoglobulin E levels in pediatric atopic dermatitis patients. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2024, 14, e12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennini, M.; Piccirillo, M.; Furio, S.; Valitutti, F.; Ferretti, A.; Strisciuglio, C.; De Filippo, M.; Parisi, P.; Peroni, D.G.; Di Nardo, G.; et al. Probiotics and other adjuvants in allergen-specific immunotherapy for food allergy: A comprehensive review. Front. Allergy 2024, 5, 1473352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, C.Y.Y.; Leung, N.Y.H.; Leung, A.S.Y.; Wong, G.W.K.; Leung, T.F. Seafood Allergy in Asia: Geographical Specificity and Beyond. Front. Allergy 2021, 2, 676903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wan, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, X. Relationship between perioperative anaphylaxis and history of allergies or allergic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 94, 111408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Warren, C.M.; Smith, B.M.; Jiang, J.; Blumenstock, J.A.; Davis, M.M.; Schleimer, R.P.; Nadeau, K.C. Prevalence and Severity of Food Allergies Among US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e185630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spolidoro, G.C.I.; Ali, M.M.; Amera, Y.T.; Nyassi, S.; Lisik, D.; Ioannidou, A.; Rovner, G.; Khaleva, E.; Venter, C.; van Ree, R.; et al. Prevalence estimates of eight big food allergies in Europe: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2023, 78, 2361–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, B.B.; Blackmon, W.; Xu, C.; Holt, C.; Boateng, N.; Wang, D.; Szafron, V.; Anagnostou, A.; Anvari, S.; Davis, C.M. Diagnosis and management of shrimp allergy. Front. Allergy 2024, 5, 1456999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalayasingam, M.; Gerez, I.F.; Yap, G.C.; Llanora, G.V.; Chia, I.P.; Chua, L.; Lee, C.J.; Ta, L.D.; Cheng, Y.K.; Thong, B.Y.; et al. Clinical and immunochemical profiles of food challenge proven or anaphylactic shrimp allergy in tropical Singapore. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruethers, T.; Taki, A.C.; Johnston, E.B.; Nugraha, R.; Le, T.T.K.; Kalic, T.; McLean, T.R.; Kamath, S.D.; Lopata, A.L. Seafood allergy: A comprehensive review of fish and shellfish allergens. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 100, 28–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.S.; Yuen, A.W.; Wai, C.Y.; Leung, N.Y.; Chu, K.H.; Leung, P.S. Diagnosis of fish and shellfish allergies. J. Asthma Allergy 2018, 11, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; He, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, H. Research Progress on Shrimp Allergens and Allergenicity Reduction Methods. Foods 2025, 14, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelis, S.; Rueda, M.; Valero, A.; Fernandez, E.A.; Moran, M.; Fernandez-Caldas, E. Shellfish Allergy: Unmet Needs in Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 30, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, C.Y.Y.; Leung, P.S.C. Emerging approaches in the diagnosis and therapy in shellfish allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 22, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Bian, J.; Xiong, Q.; Wong, B.S.; Tsui, S.K.; Kwan, K.M.; Leung, N.Y.; Leung, T.F.; Leung, P.S.C.; Chu, K.H.; et al. Revealing the Diverse Allergenic Protein Repertoire of Six Widely Consumed Crab Species: A Species-Specific Allergen in King Crab. Allergy 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggioni, C.; Leung, A.S.; Wai, C.Y.; Davies, J.M.; Sompornrattanaphan, M.; Pacharn, P.; Chamani, S.; Brettig, T.; Peters, R.L. Exploring geographical variances in component-resolved diagnosis within the Asia-Pacific region. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 36, e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, C.Y.Y.; Leung, N.Y.H.; Leung, A.S.Y.; Ngai, S.M.; Pacharn, P.; Yau, Y.S.; Rosa Duque, J.S.D.; Kwan, M.Y.W.; Jirapongsananuruk, O.; Chan, W.H.; et al. Comprehending the allergen repertoire of shrimp for precision molecular diagnosis of shrimp allergy. Allergy 2022, 77, 3041–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A.L.; Eigenmann, P.A.; Sicherer, S.H. Clinical Relevance of Cross-Reactivity in Food Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraro, A.; de Silva, D.; Halken, S.; Worm, M.; Khaleva, E.; Arasi, S.; Dunn-Galvin, A.; Nwaru, B.I.; De Jong, N.W.; Rodriguez Del Rio, P.; et al. Managing food allergy: GA(2)LEN guideline 2022. World Allergy Organ J. 2022, 15, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, R.; Senthil, P.; Chew, W.; Patolia, J.; Tran, D. Clinical Outcome For Fish and Shellfish Oral Immunotherapy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 133, S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorf, S.; Purington, N.; Kumar, D.; Long, A.; O’Laughlin, K.L.; Sicherer, S.; Sampson, H.; Cianferoni, A.; Whitehorn, T.B.; Petroni, D.; et al. A Phase 2 Randomized Controlled Multisite Study Using Omalizumab-facilitated Rapid Desensitization to Test Continued vs. Discontinued Dosing in Multifood Allergic Individuals. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 7, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoos, A.M.; Chan, E.S.; Wong, T.; Erdle, S.C.; Chomyn, A.; Soller, L.; Mak, R. Bypassing the build-up phase for oral immunotherapy in shrimp-allergic children. World Allergy Organ. J. 2024, 17, 100865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.Y.; Cao, S.; Martinez, K.; Sharma, R.; Raeber, O.; Fernandes, A.; Bogetic, D.; Kaushik, A.; Gupta, S.; Manohar, M.; et al. Shrimp oral immunotherapy outcomes in the phase 2 clinical trial: MOTIF. Front. Allergy 2025, 6, 1458131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, G.F.; Baumert, J.L.; Blom, W.M.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Meima, M.Y.; Remington, B.C.; Wheeler, M.W.; Westerhout, J.; Taylor, S.L. Full range of population Eliciting Dose values for 14 priority allergenic foods and recommendations for use in risk characterization. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat, M.; El-Damhougy, K.; Sadiq, A.; Attia, M.; Mabrouk, M. Desensitization by Sublingual Immunotherapy for Crustacean Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, AB88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, L.M.; Cullen, N.A. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergy to shrimp: The nine-year clinical experience of a Midwest Allergy-Immunology practice. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, N.Y.H.; Wai, C.Y.Y.; Shu, S.A.; Chang, C.C.; Chu, K.H.; Leung, P.S.C. Low-Dose Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy Induces Tolerance in a Murine Model of Shrimp Allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 174, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Longo, V.; Colombo, P. Nanoparticles in allergen immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 21, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reese, G.; Viebranz, J.; Leong-Kee, S.M.; Plante, M.; Lauer, I.; Randow, S.; Moncin, M.S.; Ayuso, R.; Lehrer, S.B.; Vieths, S. Reduced allergenic potency of VR9-1, a mutant of the major shrimp allergen Pen a 1 (tropomyosin). J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 8354–8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, C.Y.; Leung, N.Y.; Ho, M.H.; Gershwin, L.J.; Shu, S.A.; Leung, P.S.; Chu, K.H. Immunization with Hypoallergens of shrimp allergen tropomyosin inhibits shrimp tropomyosin specific IgE reactivity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, X.; Fang, L.; Qin, X.; Gu, R.; Lu, J.; Li, G. Hypoallergenic mutants of the major oyster allergen Cra g 1 alleviate oyster tropomyosin allergenic potency. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1973–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xia, F.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Cao, M.; Liu, G. Two hypo-allergenic derivatives lacking the dominant linear epitope of Scy p 1 and Scy p 3. Food Chem. 2022, 373 Pt B, 131588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidmeer-Jongejan, L.; Huber, H.; Swoboda, I.; Rigby, N.; Versteeg, S.A.; Jensen, B.M.; Quaak, S.; Akkerdaas, J.H.; Blom, L.; Asturias, J.; et al. Development of a hypoallergenic recombinant parvalbumin for first-in-man subcutaneous immunotherapy of fish allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 166, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, W.; Simpson, B.K.; Rui, X. Construction of hypoallergenic microgel by soy major allergen beta-conglycinin through enzymatic hydrolysis and lactic acid bacteria fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2024, 175, 113733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Seo, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, K.S.; Byun, M.W. Changes of the antigenic and allergenic properties of a hen’s egg albumin in a cake with gamma-irradiated egg white. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2005, 72, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, Y.; Liu, L.J.; Shono, N.; Hinkula, J.; Kjerrstrom, A.; Aoki, I.; Okuda, K.; Wahren, B.; Fukushima, J. Th1-biased immune responses induced by DNA-based immunizations are mediated via action on professional antigen-presenting cells to up-regulate IL-12 production. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2000, 119, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeekens, J.M.; Kesselring, J.R.; Frizzell, H.; Bagley, K.C.; Kulis, M.D. Induction of food-specific IgG by Gene Gun-delivered DNA vaccines. Front. Allergy 2022, 3, 969337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, O.T.; Tamayo, J.M.; Stranks, A.J.; Koleoglou, K.J.; Oettgen, H.C. Allergen-specific IgG antibody signaling through FcgammaRIIb promotes food tolerance. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 189–201 e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, C.Y.Y.; Leung, N.Y.H.; Leung, P.S.C.; Chu, K.H. Modulating Shrimp Tropomyosin-Mediated Allergy: Hypoallergen DNA Vaccines Induce Regulatory T Cells to Reduce Hypersensitivity in Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K.; Takeda, S.; Uchida, M.; Maeda, M.; Endo, N.; Sugahara, S.; Suzuki, H.; Fukahori, H. Lit-LAMP-DNA-vaccine for shrimp allergy prevents anaphylactic symptoms in a murine model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113 Pt. A, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, D.; Basler, M. PLGA Particles in Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brune, K.D.; Howarth, M. New Routes and Opportunities for Modular Construction of Particulate Vaccines: Stick, Click, and Glue. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layhadi, J.A.; Starchenka, S.; De Kam, P.J.; Palmer, E.; Patel, N.; Keane, S.T.; Hikmawati, P.; Drazdauskaite, G.; Wu, L.Y.D.; Filipaviciute, P.; et al. Ara h 2-expressing cucumber mosaic virus-like particle (VLP Peanut) induces in vitro tolerogenic cellular responses in peanut-allergic individuals. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 155, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, S.; Ruethers, T.; Karnaneedi, S.; Yin, L.W.S.; Lopata, A.L. Advances in Shellfish Allergy Therapy: From Current Approaches to Future Strategies. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 68, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanasit, S.; Johnston, E.; Thanasarnthungcharoen, C.; Kamath, S.D.; Bohle, B.; Lopata, A.L.; Jacquet, A. Hypoallergenic chimeric virus-like particles for the development of shrimp tropomyosin allergen Pen m 1-specific blocking antibodies. Allergy 2024, 79, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlit, H.; Bellinghausen, I.; Frey, H.; Saloga, J. Recent Advances in the Use of Nanoparticles for Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy. Allergy 2017, 72, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopata, A.L.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; Kamath, S.D. Allergens and molecular diagnostics of shellfish allergy: Part 22 of the Series Molecular Allergology. Allergo J. Int. 2016, 25, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, A.; Kohli, A.; Nadeau, K.C. Food allergy diagnosis and therapy: Where are we now? Immunotherapy 2013, 5, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.d.C. Edible Insects and Allergy Risks: Implications for Children and the Elderly. Allergies 2025, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.S.Y.; Chan, O.M.; Ngai, N.A.; Sy, H.Y.; Au, A.W.S.; Leung, R.T.C.; Ngai, J.Y.M.; Yung, E.; Tang, M.F.; Wong, G.W.K.; et al. Trends in food allergy among Hong Kong preschoolers: Findings from 2006, 2013, and 2020 surveys. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2025, 36, e70188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark Messina, C.V. Recent Surveys on Food Allergy Prevalence. Nutr. Today 2020, 55, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).