Abstract

Valorizing fruit and vegetable residues as renewable sources of bioactive compounds (BCs) is critical for advancing sustainable biotechnology. This review (i) assesses the occurrence, diversity and functionality of BCs in 20 edible plant residues; (ii) compares and classify them by botanical family and residue type; (iii) reviews and evaluates the efficiency of conventional and green extraction and characterization techniques for recovering phytochemical and isolating phenolics (e.g., flavonoids and anthocyanins), carotenoids, alkaloids, saponins, and essential oils; and (iv) examines the BCs’ environmental, medical, and industrial applications. It synthesizes current knowledge on the phytochemical potential of these crops, highlighting their role in diagnostics, biomaterials, and therapeutic platforms. Plant-derived nanomaterials, enzymes, and structural matrices are employed in regenerative medicine and biosensing. Carrot- and pumpkin-based nanoparticles accelerate wound healing through antimicrobial and antioxidant protection. Spinach leaves serve as decellularized scaffolds that mimic vascular and tissue microenvironments. Banana fibers are used in biocompatible composites and sutures, and citrus- and berry-derived polyphenols improve biosensor stability and reduce signal interference. Agro-residue valorization reduces food waste and enables innovations in medical diagnostics, regenerative medicine, and circular bioeconomy, thereby positioning plant-derived BCs as a cornerstone for sustainable biotechnology. The BCs’ concentration in fruit and vegetable residues varies broadly (e.g., total phenolics (~50–300 mg GAE/g DW), anthocyanins (~100–600 mg C3G/g DW), and flavonoids (~20–150 mg QE/g DW)), depending on the crop and extraction method. By linking quantitative food waste hotspots with phytochemical potential, the review highlights priority streams for the circular-bioeconomy interventions and outlines research directions to close current valorization gaps.

1. Introduction

Food waste has become a significant global environmental, social, and economic challenge, driven by rapid population growth, urbanization, and inefficiencies within the agricultural and food supply chains. From primary production to household consumption, shortcomings in waste management persistently strain resources and limit opportunities for a circular economy.

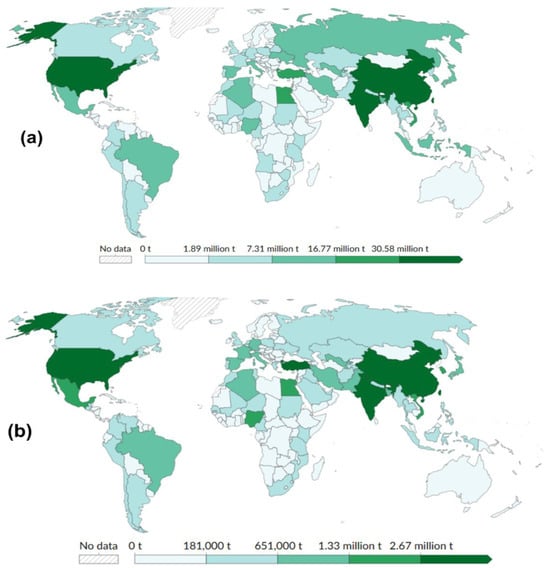

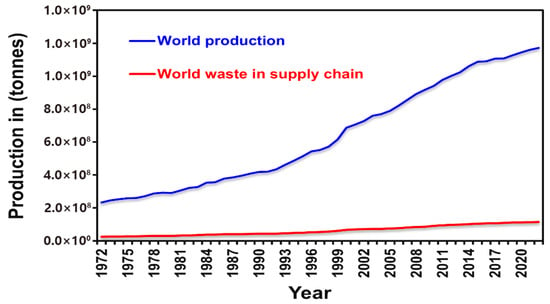

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), in 2022, final consumers discarded approximately 1.05 gigatons (Gt/y) of food, with 61% originating from households, 26% from food-service establishments, and 13% from retail outlets [1]. A substantial portion of this discarded biomass is plant-based; compositional analyses show that fruit and vegetable residues account for roughly 45% of household waste and pre-retail losses—nearly 890 Mt y−1 of underutilized material [2]. Over the past fifty years, global vegetable production has increased about fivefold (from 246 Mt/y to 1.17 Gt/y), while supply-chain losses rose in parallel (from 25 Mt/y to 114 Mt/y), with loss rates remaining around 9.9% [3].

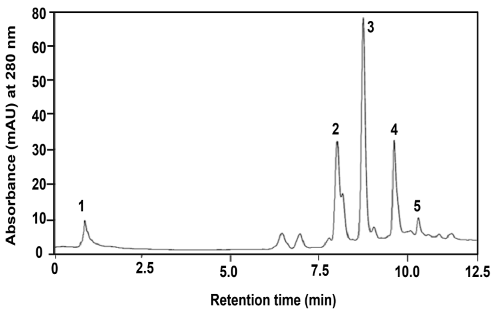

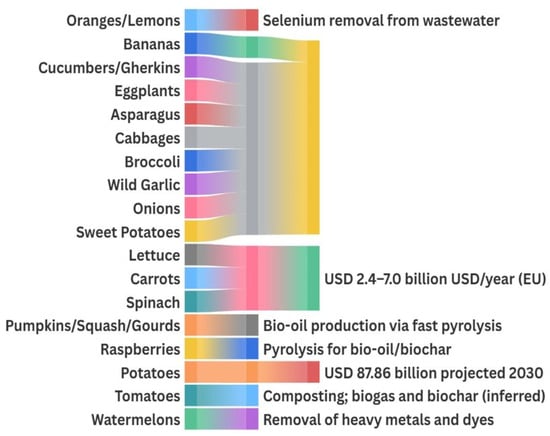

High-output countries such as China (619 Mt/y), India (145 Mt/y), and the United States of America (31.5 Mt/y) dominate global production and associated losses. Nations like Turkey and the USA exhibit particularly high loss-to-output ratios, suggesting challenges in storage, logistics, or market alignment [4]. It is important to note that Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) statistics (Figure 1 and Figure 2) capture pre-consumer losses, whereas the UNEP Food Waste Index reports post-retail discards [4]. These datasets therefore represent different stages and intervention points [1].

Figure 1.

Global distribution of (a) vegetable production, and (b) supply chain waste in 2023 [3].

Figure 2.

Global vegetable production and supply chain waste (1972–2022) [1,2,3,4].

Beyond their volume, plant-derived losses represent a valuable yet underexploited source of biomolecules such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenes, alkaloids, and tannins—compounds with antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties [5]. However, conventional disposal practices, such as landfilling and composting, often degrade these compounds and contribute to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [6].

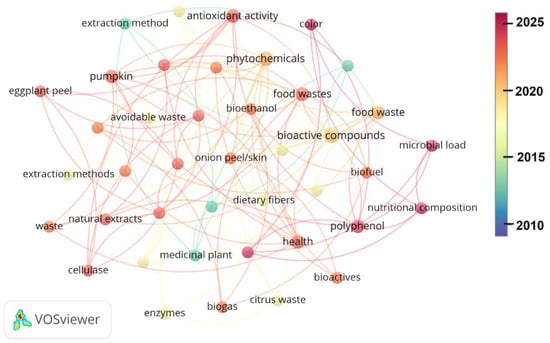

Interestingly, the research on waste-derived bioactives is contemporary and evolving. Figure 3 displays the results of the analysis of the reviewed bibliography using VOSviewer (version 1.6.20), revealing the evolution of research on the volatilization of food waste over the last 15 years. Most of the development on the bioactive compounds (BCs) from food waste has been in the last 10 years, with some aspects emerging after 2020.

Figure 3.

Evolution of research on volatilization of food waste between 2010 and 2025. The analysis was conducted using VOSviewer (version 1.6.20).

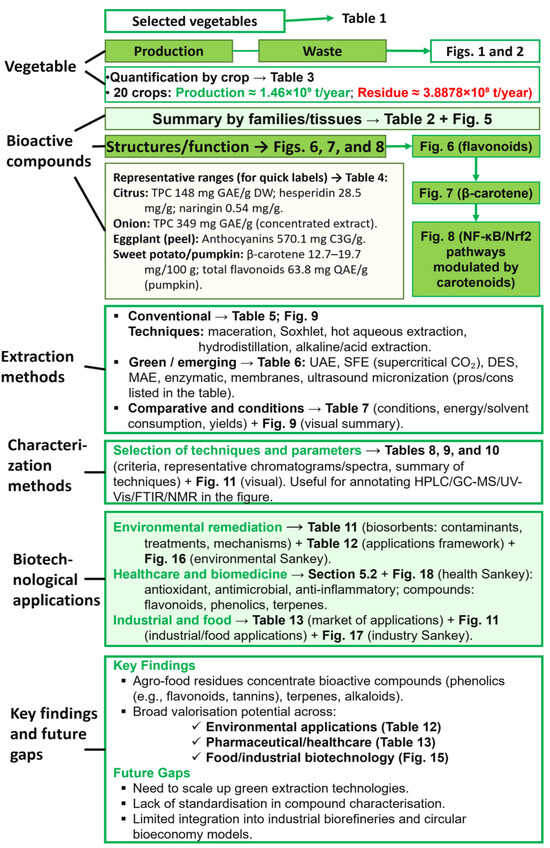

This review article aims to (i) assess the occurrence, diversity and functionality of BCs in edible plant residues; (ii) compare twenty widely produced crops, nine fruits, and eleven vegetables, classified by botanical family and residue type (Table 1); (iii) review green extraction and characterization technologies for phytochemical recovery; and (iv) examine biotechnological applications of these compounds in environmental, medical and industrial domains. By linking quantitative food waste hotspots (Figure 1 and Figure 2) with phytochemical potential, the review highlights priority streams for the circular-bioeconomy interventions and outlines research directions to close current valorization gaps. Figure 4 is a summarized roadmap for the content of this review article.

Table 1.

Selected vegetables for study.

Figure 4.

Conceptual roadmap of the review.

This review contributes to the valorization of plant-based waste through three core elements. First, it adopts a botanical and comparative perspective across twenty representative crops (nine fruits and eleven vegetables), detailing the qualitative and quantitative profiles of key BCs (phenolics, flavonoids, carotenoids, glucosinolates, sulfur compounds, alkaloids) and their anatomical distribution. Second, unlike most previous reviews that focus on single products or narrow residue types, such as citrus-processing wastes, fruit-juice by-products, cruciferous vegetables, potato or banana peels, watermelon rind, or extraction-method-centered analyses [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], this work integrates plant-by-plant and tissue-specific information. Finally, this level of resolution enables the identification of priority valorization streams (e.g., peels, seeds, stems, and pulp) for targeted applications in the food, biomedical, and environmental industries, providing an operational basis for bioprocess selection and scale-up, as discussed in later sections [16].

This review adopts the following terminology throughout the manuscript. Food waste refers to the broader category of discarded edible materials generated throughout the supply chain, covering both plant- and non-plant-derived products, as commonly defined by the UNEP and FAO. Plant-based residues refer specifically to the inedible or underutilized anatomical fractions of fruits and vegetables, including peels, seeds, stems, leaves, and pulp, generated during processing or consumption.

The manuscript then presents a critical comparison of extraction and characterization techniques, including both conventional and green technologies, for example, deep eutectic solvent extraction (DES), supercritical CO2 extraction (SFE-CO2), enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), and microwave-assisted extraction (MAE). Each method is linked to the physicochemical nature of the target compounds and to practical criteria such as yield, selectivity, sustainability, and scalability. This discussion, detailed in Section 4 and its accompanying tables, provides an operational guide for researchers and industry professionals seeking optimal recovery methods according to the waste matrix and compound class. The integration of method–compound–application relationships adds practical value that goes beyond purely bibliographic summaries.

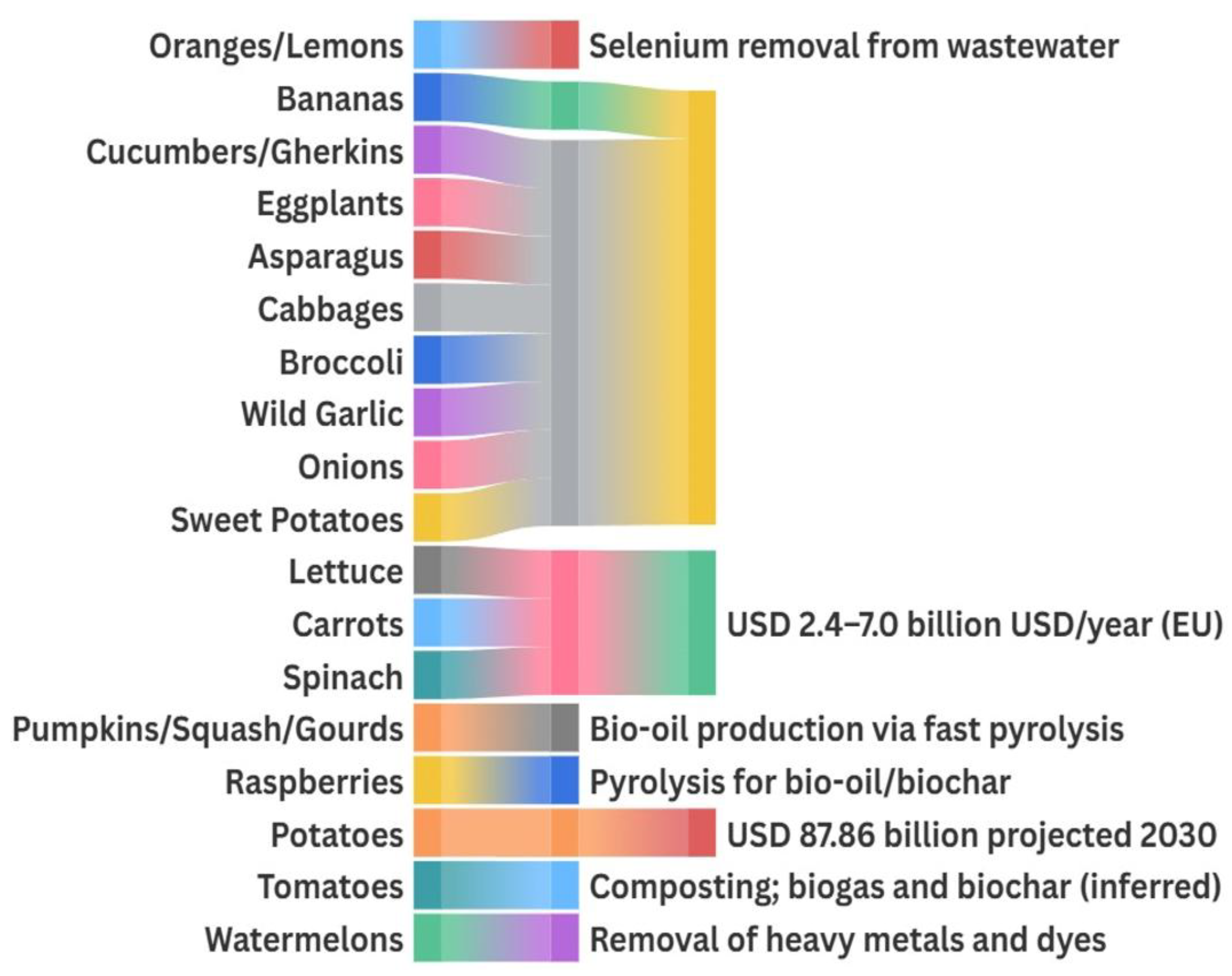

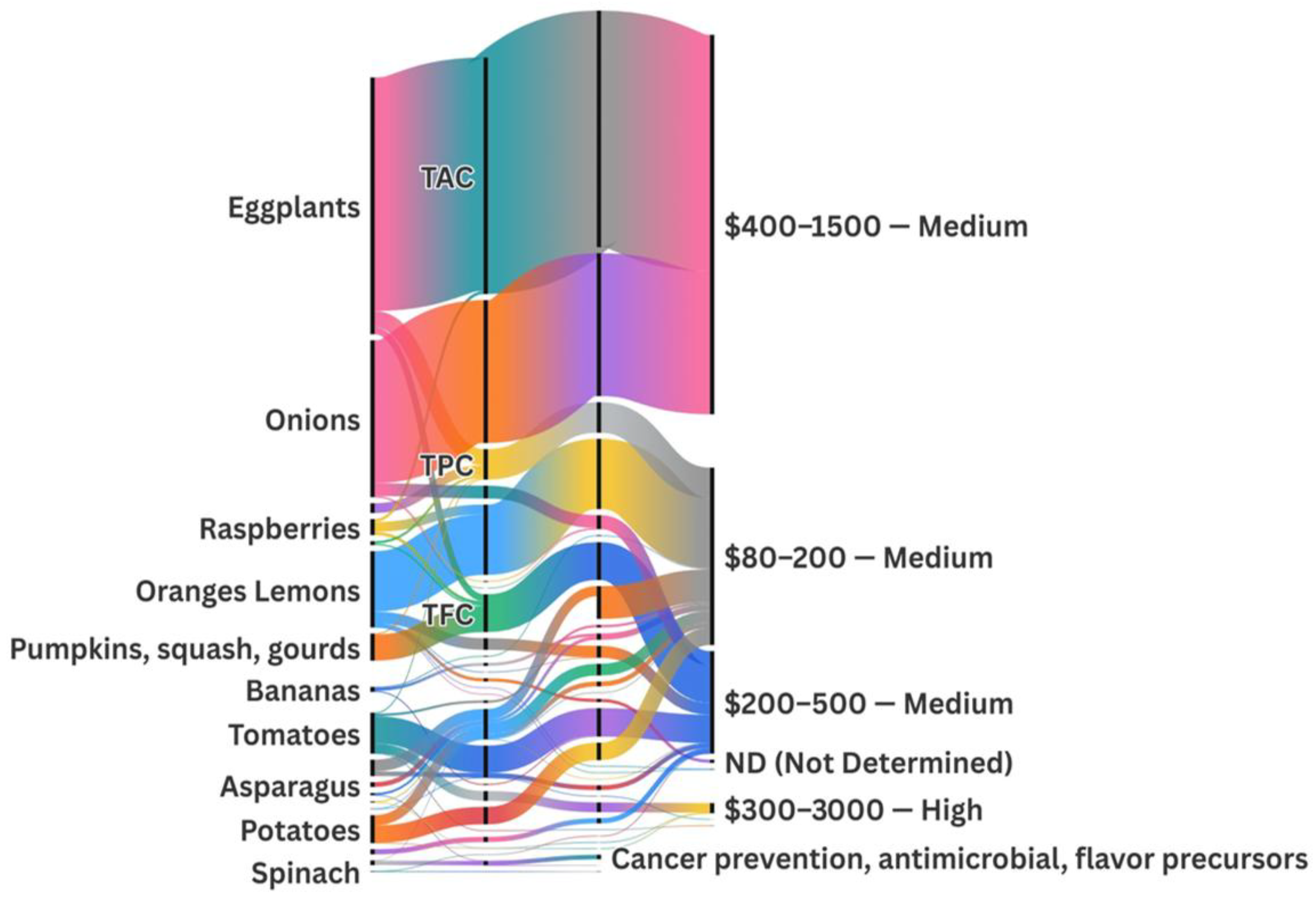

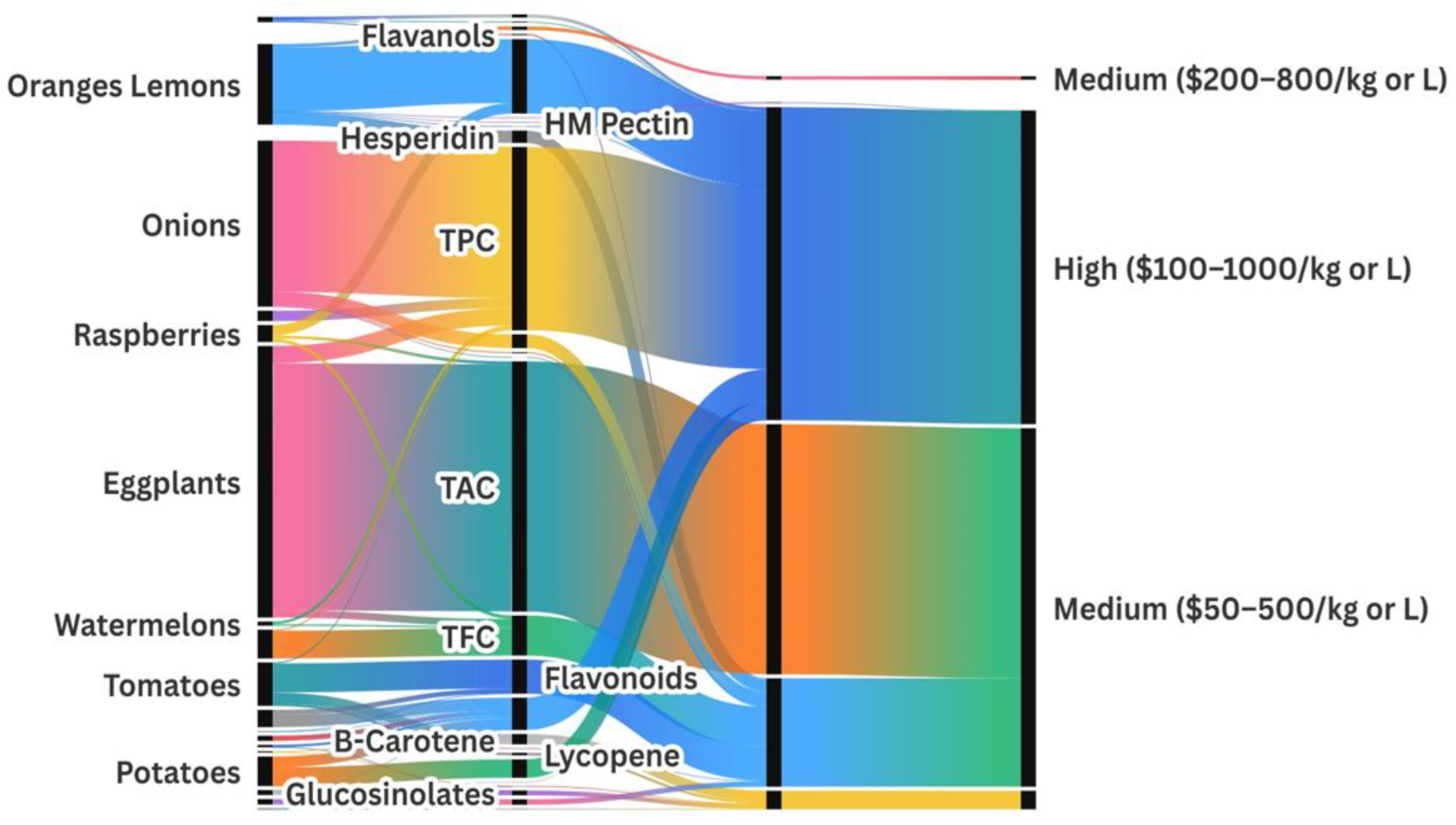

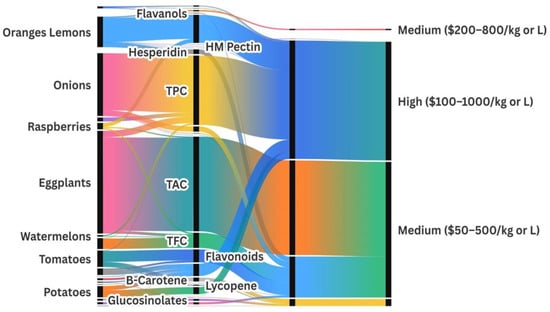

By combining compound characterization with recovery strategies, this review also highlights valorization routes (multi-product process chains) and connects them with biotechnological, industrial, and environmental applications. These routes are supported by market and technical potential indicators presented in Section 5 and Section 6, as well as the Sankey diagram. This integrative structure helps translate academic findings into scalable process designs, bridging the gap between research and industrial implementation.

Despite the growing number of local studies on extraction and isolated applications, there is still a lack of a comprehensive synthesis that correlates—plant by plant and fraction by fraction—the specific BCs with the most suitable recovery methods and industrial valorization routes. This review fills that gap by providing comparative criteria, identifying research priorities (Section 6.3), and offering practical recommendations for standardization, scale-up, and regulatory assessment, thus delivering actionable knowledge for researchers, industry, and policymakers.

2. Bioactive Materials in Food Waste

2.1. Overview of Bioactive Compounds

The first step towards narrowing current valorization gaps of the study is to understand the bioactive potential embedded in food waste. Plant-derived residues contain diverse compounds with distinct chemical structures and biological activities, many of which remain unexploited despite their abundance. Identifying and characterizing these molecules are essential to link waste streams with viable biotechnological applications and to design processes that preserve their functional integrity from recovery to end use.

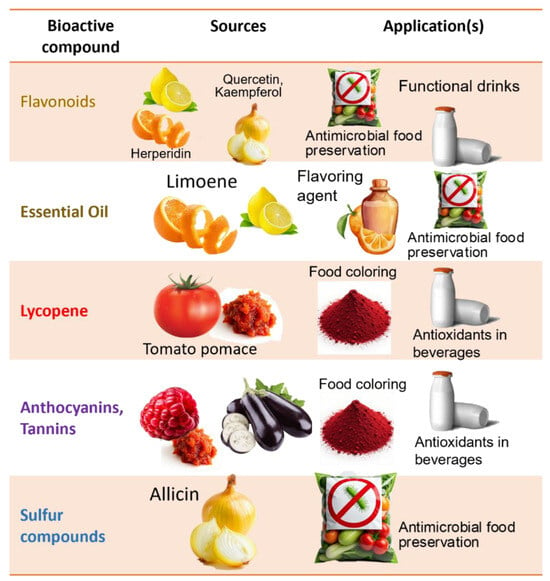

Bioactive compounds (BCs) are naturally occurring molecules present in plant matrices that exert beneficial physiological or functional effects in biological systems, including polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenes, glucosinolates, phenolic acids, alkaloids, and bioactive peptides, among others [5,12]. In the context of agro-food waste, these compounds are highly concentrated in by-products such as peels, seeds, leaves, stems, and residual pulps, making these materials strategic resources for obtaining functional ingredients and molecules of biotechnological interest [6,17]. Their relevance lies in their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, cytoprotective, and nutraceutical properties, which are widely documented in various waste streams such as citrus, solanaceae, cucurbits, alliums, and cruciferous crops [18,19,20].

Within agro-food residues, the most relevant bioactive fraction contains secondary metabolites, phenolic acids, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenes, carotenoids, and glucosinolates, each with distinct chemical features and roles in plant physiology [17]. These molecules, originally involved in the plant’s defense and adaptation systems, have evolved to help plants resist pests, pathogens, and environmental stress. For instance, Solanaceae plants accumulate glycoalkaloids (e.g., α-tomatine in green tomato peels) as natural pesticides and antifungal agents [21]. By virtue of these protective roles, such compounds have shown great promise for applications in various industries once recovered from agro-waste.

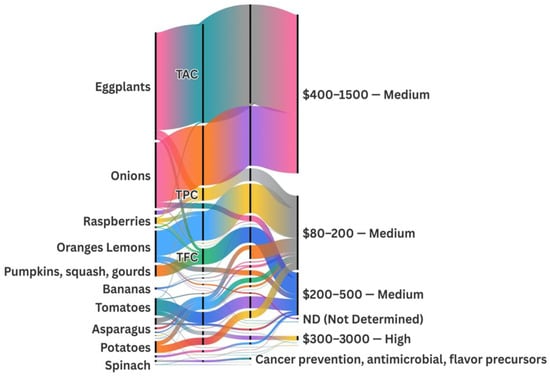

The quantification of total phenolic content (TPC) is commonly performed using the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric assay, which measures the reduction of the reagent by phenolic hydroxyl groups and reports results as gallic acid equivalents [5,12,13,22]. Total anthocyanin content (TAC) is typically determined using the pH differential method, which quantifies monomeric anthocyanins based on absorbance differences at pH 1.0 and 4.5, measured at wavelengths of 520 and 700 nm. TAC is calculated using the molar absorptivity of cyanidin-3-glucoside and expressed as cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalents, following the standardized procedure widely applied for anthocyanin analysis in plant-based matrices [17,23,24]. Total flavonoid content (TFC) is generally determined by aluminum-chloride colorimetry, in which flavonoids form measurable complexes and results are expressed as quercetin equivalents; this method is frequently used for residues enriched in flavonoid-type bioactives from agro-industrial plant by-products [19,25,26,27].

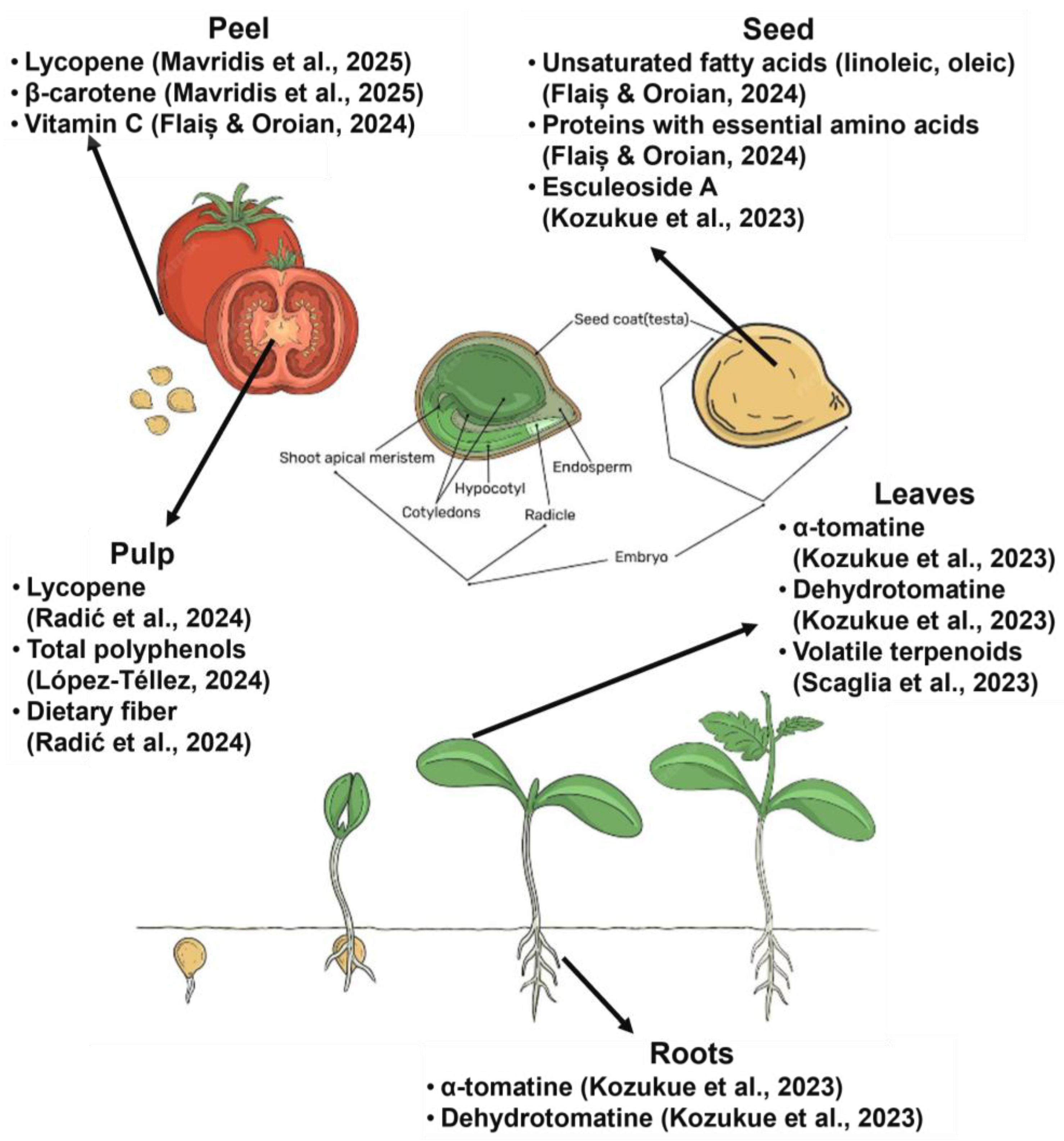

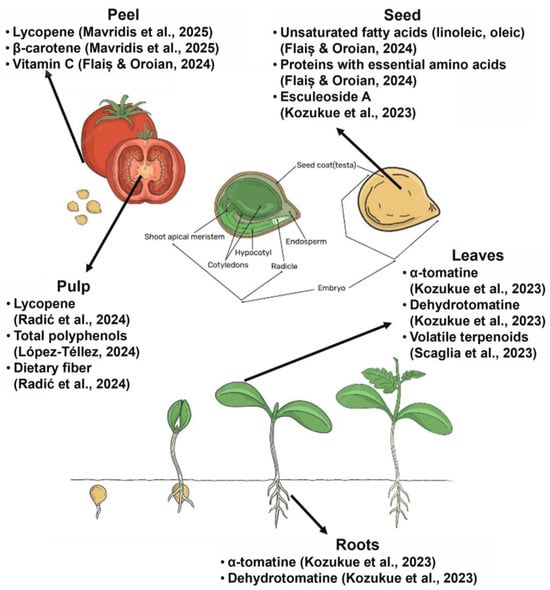

BCs are often concentrated in parts of the plant that are typically discarded during agricultural and food processing, such as peels, seeds, stalks, shells, and leaves. These “waste” tissues frequently contain significantly higher levels of phytochemicals than edible portions, making agro-food waste a rich and sustainable reservoir for functional molecules [18]. In addition to the fruit pulp, other tomato tissues, such as peel and seeds, are rich in BCs. While tomato peels can comprise three to four times more lycopene than the pulp, the seeds also contain phenolic acids and essential fatty acids, making both fractions valuable processing byproducts [28]. Citrus rinds, especially from oranges and lemons, are rich in essential oils (with d-limonene forming ~90% of orange peel oil) and flavanones such as hesperidin [18]. Potato skins, which represent only about 5% of the tuber by weight, may hold 50–100% of the tuber’s glycoalkaloid content; while the potato flesh may have less than 10 mg/kg, the peel can hold 90–400 mg/kg [29]. These examples (summarized in Table 2) highlight how common plant-based residues represent concentrated sources of bioactives with high valorization potential. The anatomical distribution of these bioactives in different tissues of Solanum lycopersicum is illustrated in Figure 5, highlighting key compounds found in the pulp, peel, seeds, leaves, and roots.

Table 2.

Summary of key bioactive compounds (BCs).

Figure 5.

Anatomical parts of Solanum lycopersicum highlight bioactive compounds in fruit, seeds, leaves, and roots [21,31,44,45,46,47].

Among these diverse compounds, phenolics (e.g., quercetin, resveratrol, and isoflavones), and carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene and lycopene) have attracted significant attention due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and nutraceutical potential. Capitalizing on such high-value molecules from waste streams aligns with circular economy principles while providing health-promoting ingredients for new products, which are discussed in the following sections.

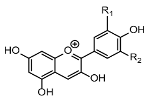

2.2. Functional Groups and Chemical Constituents

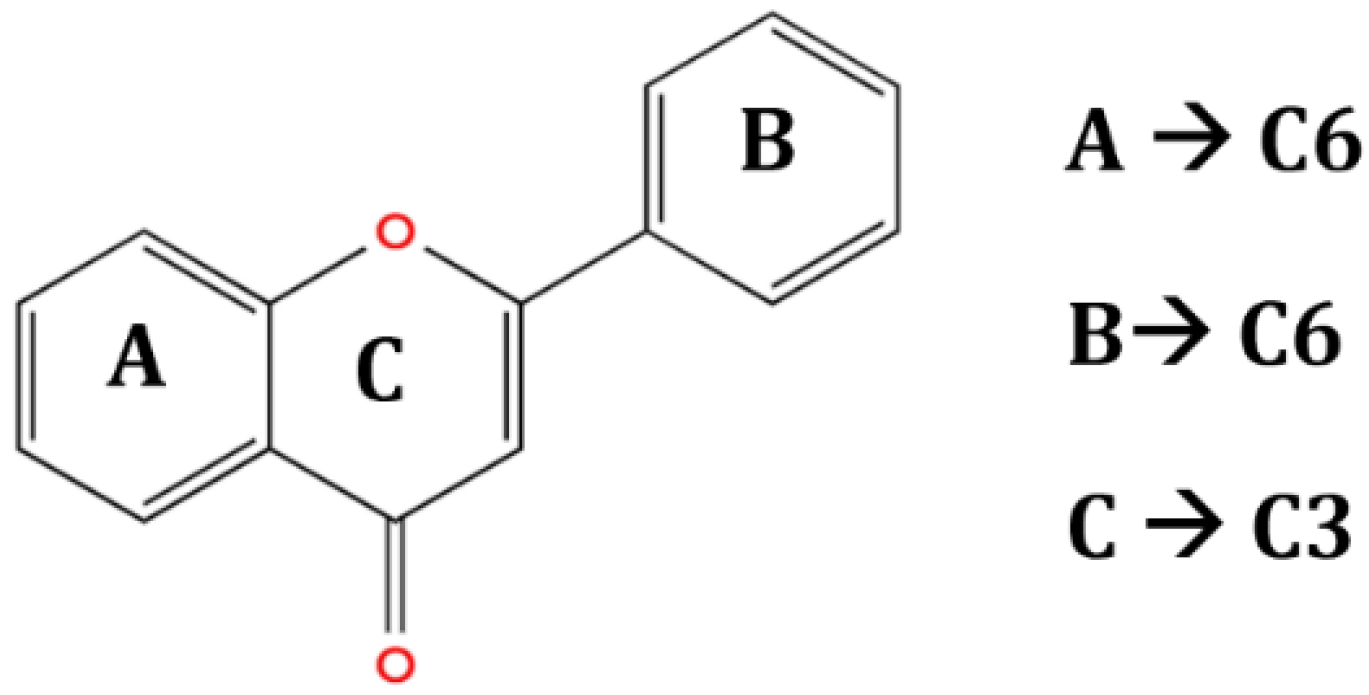

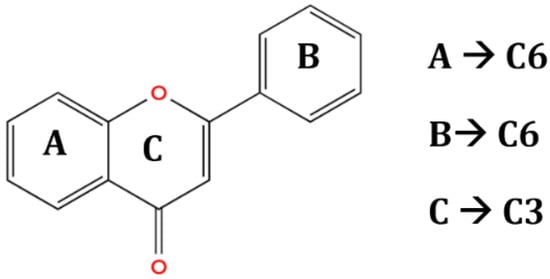

The chemical structure and functional groups directly influence the functionality of each class of BCs. Phenolic acids, for example, are characterized by one or more hydroxyl groups on an aromatic ring, which confer potent radical-scavenging ability by donating hydrogen atoms [48]. Flavonoids feature the standard C6–C3–C6 carbon skeleton (two benzene rings linked by a three-carbon bridge (Figure 6)), and their biological activity depends on the pattern of hydroxylation, methoxylation, and glycosylation on this backbone [49].

Figure 6.

General structure of flavonoids (C6–C3–C6 skeleton with several substituents) [49].

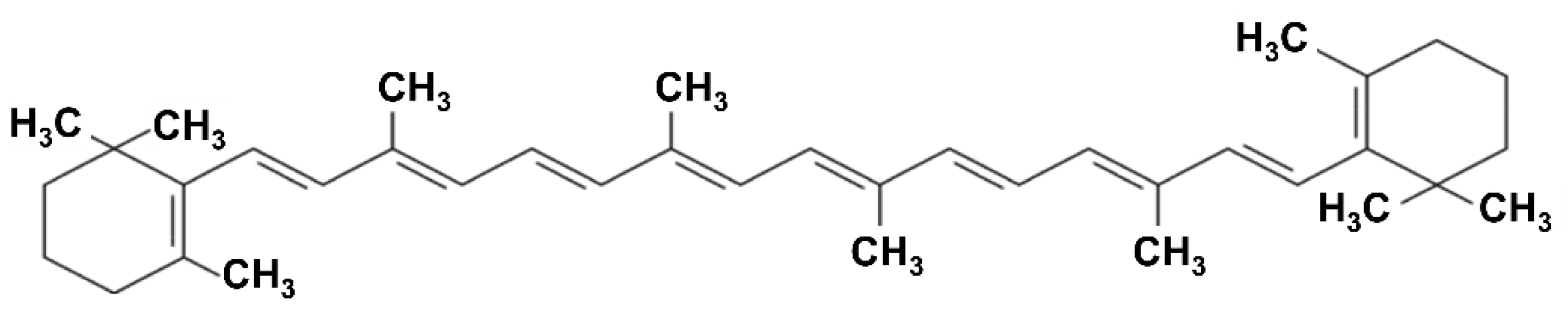

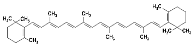

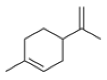

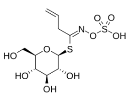

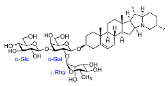

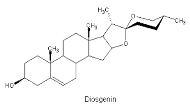

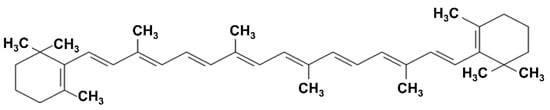

Alkaloids, for instance, are nitrogen-containing heterocycles, often with steroidal or bicyclic frameworks, that display a broad range of bioactivities. A notable example is α-solanine from potato peels, a glycoalkaloid whose polycyclic nitrogen-containing structure confers antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects against cancer cells [50]. Terpenoids, including monoterpenes such as limonene and menthol, which are abundant in citrus and mint residues, are composed of isoprene units and are strongly hydrophobic; this property enables them to insert into microbial membranes and disrupt their integrity [51]. In addition, they modulate host inflammation; for example, D-limonene reduces the production of nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated macrophages [52]. Carotenoids (e.g., lutein and zeaxanthin in green leafy vegetable by-products, or β-carotene in carrot pomace) are 40-carbon tetraterpenoids composed of eight isoprenoid units linked to position nonterminal methyl groups at 1,5- and 1,6-positions [53]. They are classified into carotenes (α- and β-carotene, lycopene, phytoene) and xanthophylls (lutein, zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin), with their conjugated double bonds determining absorption between 400–500 nm and contributing to their photoprotective and antioxidant activities (Figure 7) [53].

Figure 7.

Chemical structure of β-carotene.

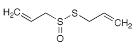

This extended conjugation handles their intense coloration (yellow, orange, red) and their ability to quench free radicals and singlet oxygen [54]. Finally, glucosinolates found in cruciferous vegetable residues (e.g., cabbage, broccoli) contain sulfur and nitrogen in their core structure, and upon hydrolysis by the enzyme myrosinase, release isothiocyanates, pungent bioactive molecules with well-documented anticancer and antimicrobial properties [55].

Given their structural diversity and multifunctionality, these BCs are increasingly investigated for use in healthcare (e.g., nutraceutical supplements, and pharmaceuticals) [50,56], food preservation and enhancement (natural additives and functional foods) [12,42,57], and environmental biotechnology (e.g., as bio-based adsorbents or pesticides) [14,58]. To conclude this section, Table 2 summarizes the most representative molecules found in selected fruit and vegetable wastes, detailing their chemical structures, key functional groups, associated bioactivities, and potential biotechnological uses.

2.3. Mechanisms of Action and Biotechnological Applications Used for Phenolic Compounds

The wide range of applications of BCs recovered from agro-food waste is linked to their mechanisms of action, which determine how they interact with biological systems and materials. Understanding these mechanisms is vital for developing applications across the environmental, medical, and food industries. This subsection highlights key examples that illustrate the chemical and biological relevance of some bioactives, focusing on their structure–function relationships.

Phenolic compounds, such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenes, and tannins, are powerful antioxidants that neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enhance the activity of endogenous enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase [59]; they also chelate redox-active metal ions [60]. A common antioxidant pathway is hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), in which a phenolic antioxidant (ArOH) donates a hydrogen atom to a free radical (e.g., a peroxyl radical, ROO·), forming a stable product (ROOH) and a resonance-stabilized phenoxyl radical (ArO·), as expressed below.

Here, the ArO· radical is delocalized over the aromatic ring, preventing radical chain reactions from occurring before cellular damage can happen [61]. Through such actions, polyphenols help protect against oxidative-stress-related conditions (e.g., aging and neurodegeneration) [56], and can even support pollutant degradation in environmental systems. For instance, soil microbiota under anoxic conditions have been shown to enzymatically depolymerize and metabolize polyphenols, demonstrating potential pollutant breakdown [62].

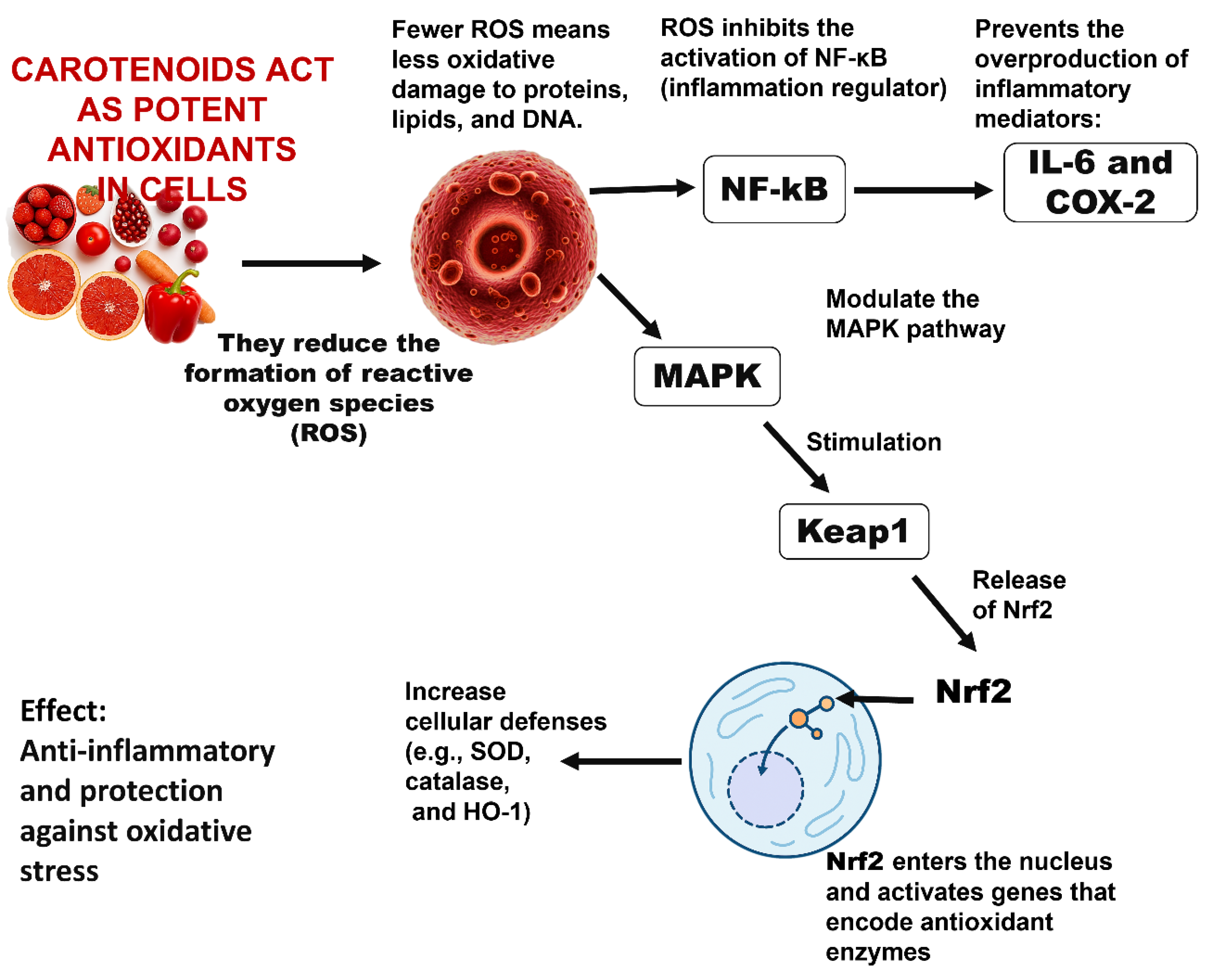

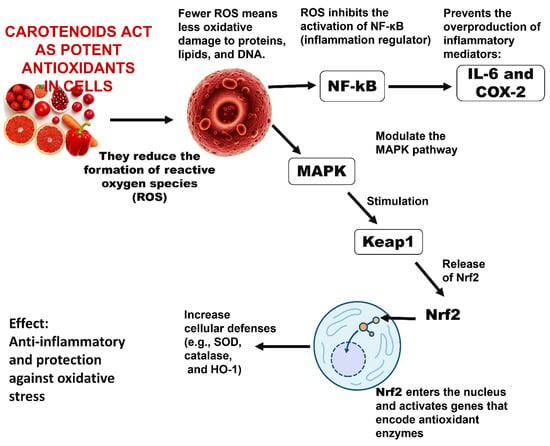

Carotenoids, including β-carotene and lycopene, have been reported to influence inflammatory and antioxidant pathways, particularly through modulation of NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling in cellular studies [54]. Several natural terpenoids also exhibit inhibitory effects on the NF-κB pathway (Figure 8), although the specific steps targeted, such as IκB regulation or p65 nuclear translocation, vary depending on the compound and experimental system [63,64]. Steroidal glycoalkaloids from the Solanaceae family, including α-solanine and α-chaconine, have been shown to alter epithelial barrier function and cellular permeability in vitro, suggesting an impact on membrane-associated processes [65]. Overall, these findings highlight the diverse biological activities of plant-derived metabolites, while emphasizing that their mechanisms are often context-dependent and require further investigation. In the food sector, carotenoids recovered from waste material such as tomato peels or carrot pomace are utilized as natural colorants and antioxidants. For example, β-carotene from carrot pomace has been employed in functional beverages and dairy products as a coloring and bioactive additive [66]. More recently, they have been incorporated into biodegradable packaging to block light and scavenge radicals, thus prolonging food quality [12].

Figure 8.

Inflammatory signaling pathways modulated by carotenoids, showing their inhibitory effect on NF-κB activation and their role in activating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses [54].

Terpenoids, such as limonene from citrus peel oil and menthol from mint residues, act by disrupting microbial membranes. These features are valuable for natural food preservation, medicinal formulations, and agro-ecological pest control. For instance, orange peel oil rich in limonene has shown insecticidal activity against fruit flies and mosquitoes by inducing paralysis on contact [54].

Alkaloids, such as tomatine in tomato waste, are nitrogen-containing heterocycles with potent antimicrobial and anticancer activities [21]. Their mechanisms often involve interaction with membrane sterols, leading to membrane disruption and interference with cellular processes such as ion transport, making them promising candidates for natural crop protection or therapeutic applications [67].

In summary, the diverse functions of these bioactives highlight the importance of recovering them as part of a sustainable circular bioeconomy, generating value-added products that benefit human health, enhance food quality, and reduce environmental impact.

3. Analysis of Agro-Food Wastes

3.1. Introduction to Edible Plant Waste Valorization

3.1.1. Selection of Plant Species and Botanical Classification

Agro-food waste poses escalating environmental and economic challenges globally. Edible plant waste, including fruit, vegetable, and root crop by-products, is an underutilized resource for valorization due to its abundance and rich content of BCs. The strategic repurposing of these residues aligns with circular economy principles, offering sustainable solutions for waste reduction while enabling the recovery of valuable biomolecules for various industrial applications.

This review systematically analyzes key plant-derived wastes, categorized by botanical criteria to ease comparative analysis. As shown in Table 1, these include: (1) nine botanical fruits (seed-bearing structures critical for plant reproduction), and (2) eleven non-fruit vegetables (encompassing roots, leaves, and other edible plant parts). This classification enables targeted evaluation of BCs based on shared morphological and phylogenetic characteristics (e.g., phenolic distribution in Solanaceae fruits vs. glucosinolates in Brassicaceae leaves).

3.1.2. Scientific and Cultural Justification for Crop Selection

The twenty crops are selected based on a combination of scientific, cultural, and economic rationale. Scientifically, they are among the world’s most widely cultivated and consumed species, generating substantial agro-industrial residues that account for a significant share of global production and waste streams. Table 3 provides the estimated global production, predominant waste types, and calculated waste generation for the selected crops, providing a quantitative basis for their selection in the present study. This selection provides a representative set of plant-derived residues for assessing the diversity, abundance, and potential uses of BCs described in this study.

Table 3.

Estimated global production and waste generation for selected fruits and vegetables; Mt stands for million tons [3].

These crop by-products, including peels, seeds, stems, and pulp, are consistently reported as rich sources of polyphenols, carotenoids, glucosinolates, terpenoids, alkaloids, and other high-value bioactives relevant to food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and environmental applications [3,4,30,68]. Their high global production ensures abundant, continuous, and scalable feedstocks for biotechnological valorization. Culturally and economically, these crops are staples in various diets, important export commodities, and key components of regional agricultural identity, making their residue streams both a waste-management challenge and a significant unrealized economic opportunity.

3.2. Bioactive Compounds in Fruit and Vegetable Residues

3.2.1. Botanical Definition and Agro-Industrial Relevance

For a clearer understanding of the agro-food residues analyzed, it is essential to provide botanical definitions: fruits are seed-bearing structures that develop from the ovary of flowering plants, while vegetables cover a broader range of edible plant parts, including roots, stems, leaves, and immature inflorescences [69]. This classification is taxonomically relevant and functionally significant, as different plant organs accumulate specific classes of phytochemicals. For instance, fruit peels, rinds, and seeds often concentrate pigments and compounds with aromatic rings (e.g., flavonoids and carotenoids) [70]. In contrast, vegetables, especially those in the Brassicaceae and Amaryllidaceae families such as broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower, are rich in glucosinolates and sulfur-containing metabolites [71]. The selected residues, derived from the crops listed in Table 2, have been studied due to their potential as sources of BCs. Their botanical diversity and waste generation profiles provide a strong framework for comparing the chemical composition and functional potential of their by-products. The following section offers a compound-specific analysis supported by recent literature.

3.2.2. Composition, Functional Groups, and Bioactive Compounds

Plant-based residues are a valuable source of biologically active compounds (Table 4). These by-products hold a variety of secondary metabolites, ranging from phenolic acids to carotenoids, that contribute to many potential biotechnology applications.

A remarkable variation in total phenolic content (TPC) is observed across taxa. Citrus fruits (oranges/lemons) show the highest phenolic content among the analyzed plant sources, with a TPC of 147.6 mg (gallic acid equivalent) GAE/g DW [72]. Onions follow closely with an exceptionally high TPC of 348.7 mg GAE/g, likely derived from a concentrated extract [73]. Sweet potato peels also stand out with 2.6 mg GAE/g DW [74], while carrots are one of the richest dietary sources of phenolics with 85.9 mg GAE/g DW [75].

Table 4.

Summary of concentrations of major bioactive compounds in vegetable residues.

Table 4.

Summary of concentrations of major bioactive compounds in vegetable residues.

| Residue/Waste | Family | Bioactive Compound | Quantity/Range | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bananas | Musaceae | phenolic acids | 21.7 mg/100 g DW | [30] |

| flavanols | 26.8 mg/100 g DW | [30] | ||

| Total Polyphenols | 73.4 mg/100 g DW | [30] | ||

| Oranges/lemons | Rutaceae | hesperidin naringin | 28.5 mg/g DW 0.5 mg/g DW | [72] [72] |

| phenolic acids | 147.6 mg GAE/g DW | [72] | ||

| essential oils | 7.8 mg/g DW | [76] | ||

| Cucumbers | Cucurbitaceae | phenolic acids | 23.8 mg GAE/g | [77] |

| Eggplants | Solanaceae | TAC | 570.1 mg C3G/g DW Extract | [78] |

| phenolic acids | 39.4 ± 4.7 mg GAE/g Peel Extract | [24,79] | ||

| flavanoids | 17.1 ± 2.9 mg CE/g Peel Extract | [76] | ||

| Pumpkins | Cucurbitaceae | phenolic acids | 2.5 mg GAE/g DW | [68] |

| flavanoids | 63.8 mg QAE/g DW | [68] | ||

| Raspberries | Rosaceae | phenolic acids | 23.9 mg GAE/g DW | [26,36] |

| TAC | 7.1 mg C3G/L DW | [36] | ||

| flavanoids | 8.0 mg QE/g DW | [36] | ||

| Tomatoes | Solanaceae | phenolic acids | 2.6 mg de GAE/g DW | [44] |

| quercetin | 1.0 mg GAE/g DW | [31] | ||

| β-Carotene | 23.8% Dry Extract | [34] | ||

| Lycopene | 0.05966 mg/g DW Extract | [34] | ||

| flavonoids | 66.8 mg/L Extract | [45] | ||

| Watermelons | Cucurbitaceae | phenolic acids | 6.1 mg GAE/g DW | [80] |

| flavanoids | 3.4 mg Rutin/g DW | [80] | ||

| Asparagus | Asparagaceae | phenolic acids | 11.6 mg GAE/g DW | [43,81] |

| Cabbages | Brassicaceae | phenolic acids | 43.1–66.0 mg/100 g FW | [82] |

| glucosinolates | 10.9 mmol/g | [71] | ||

| Lettuce | Asteraceae | phenolic acids | 1.8–55.1 (mg/g DW) | [83] |

| flavonoids | 0.9–22.1 (mg/g DW) | [83] | ||

| Broccoli | Brassicaceae | phenolic acids | 53.2 (mg/100 g FW) | [84,85] |

| glucosinolates | 162 (µmol/g DW) | [71] | ||

| Carrots | Apiaceae | phenolic acids | 8.6 (g GAE/100 g DW) | [75] |

| flavonoids | 39.6 mg/100 g fresh weight | [86] | ||

| Green garlic | Maryllidaceae | Flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol derivatives) | 12.5 (mg/mL) | [87] |

| Onions (raw) | Amaryllidaceae | phenolic acids | 348.7 mg GAE/g | [73] |

| quercetin (raw waste) | 14.5–5110 µg/g DW | [86] | ||

| quercetin (fermented) | 14.9–48.5 mg/g DW | [87] | ||

| kaempferol (raw waste) | 3.2–481 µg/g DW | [86] | ||

| Potatoes | Solanaceae | phenolic acids | 10–40 GAE mg/g DW | [38,88] |

| hydroxycinnamates | 25–60 mg/g (DW) | [38] | ||

| β-carotene | 0.6 μg/g (DW) | [89] | ||

| Sweet potatoes | Convolvulaceae | phenolic acids | 179.8 mg GAE/100 g tuber 262.3 mg GAE/100 g peel | [69] |

| total carotenoids (β-carotene) | 12.7 (mg/100 g) peel 19.6 (mg/100 g) tuber | [74] | ||

| Spinach | Amaranthaceae | total polyphenols | 0.4–0.7 mg GAE/g dry residue | [42] |

| chlorophylls | 112.8 mg/100 g | [57] |

DW: Dry Weight; FW: Fresh Weight; GAE: gallic acid equivalents; CE: catechin equivalents; QE: quercetin equivalents; QAE: quercetin acid equivalents; C3G: cyanidin-3-glucoside; TPC: total phenolic content; TFC: total flavonoid content; TAC: total anthocyanin content.

Eggplant peel extract ranks fifth with a TPC of 39.4 ± 4.6 mg GAE/g, showing its strong potential as a phenolic-rich food component [24,76]. Other vegetables, especially those from the Brassicaceae family, such as broccoli and cabbage, are also notable for their glucosinolate compounds content, with broccoli reaching 162 µmol/g DW and cabbage up to 10.9 mmol/g [71], which has chemopreventive potential.

Among fruits, citrus peels stand out with high levels of hesperidin (28.5 mg/g DW) and naringin (0.54 mg/g DW) [72], alongside significant amounts of essential oils (7.8 mg/g DW), making them multipurpose residues for food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic uses [37,77].

In tomato skins, moderate phenolic levels are complemented by high-value carotenoids such as lycopene and β-carotene, which are key in nutraceutical formulations [34,44]. Pumpkin and sweet potato peels also provide relevant carotenoid concentrations, including β-carotene levels of 12.7 mg/100 g in sweet potato peel and 19.6 mg/100 g in the tuber [74], supporting their potential as natural colorants and antioxidant additives. Pumpkin peels additionally contain 63.8 mg quercetin acid equivalents (QAE)/g DW of total flavonoids [68].

Anthocyanins, another valuable group of pigments, are particularly abundant in eggplant peels, with TAC reaching 570.1 mg Cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G)/g DW [78], and raspberries, which contain up to 7.1 mg C3G/L DW [36], highlighting the relevance of Solanaceae and Rosaceae fruits for natural pigment recovery.

Overall, these findings emphasize the diverse phytochemical profiles of plant-based residues and highlight species- and tissue-specific advantages for targeted valorization. The high yields observed in peels, seeds, and leaves, often discarded during processing, support their prioritization in circular economy strategies. Extraction techniques and bioapplications will be discussed in the following sections.

4. Extraction and Characterization Methods

The valorization of edible plant-based residue for bioactive compound (BC) recovery requires a critical stage of separation and analysis. This section outlines the most widely used extraction processes and characterization techniques to identify chemical structures and functional properties. Conventional and advanced methods are considered, along with a comparative analysis of their applications, advantages, and limitations.

4.1. Extraction Methods

The extraction of BCs in plant-based residues requires breaking down the plant matrix to release the valuable metabolites previously mentioned (flavonoids, carotenoids, and phenolic acids). An exact selection of an extraction method depends on the compound’s chemical nature, the type of plant-based residue, desired efficiency, and the overall sustainability of the process [16,88].

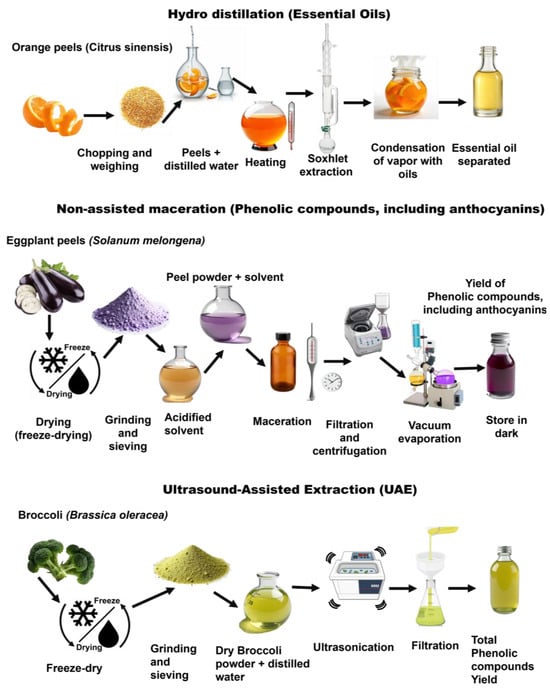

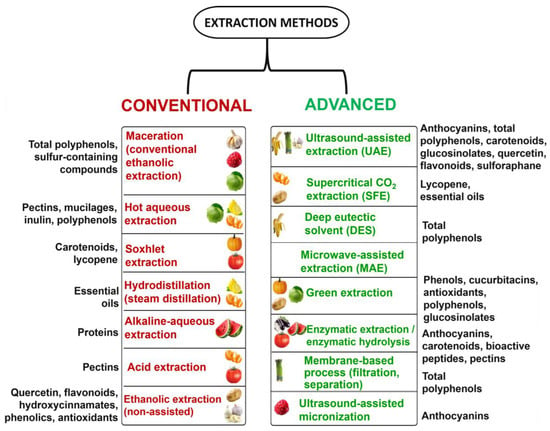

Some conventional extraction approaches typically use organic solvents and simple mechanical processes, while advanced methods aim to improve yield and reduce processing time and solvent use, standing for an innovative green approach for extraction (e.g., ultrasound, microwave, supercritical fluids, and ionic liquids), as depicted in Figure 9. For example, SFE-CO2 (an advanced strategy) cuts the need for hazardous organic solvents and protects heat-sensitive BCs, illustrating the performance gains of newer techniques [89].

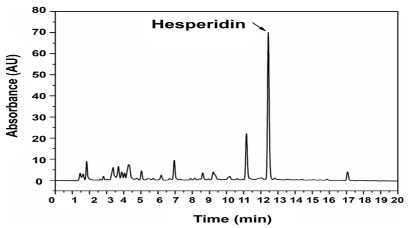

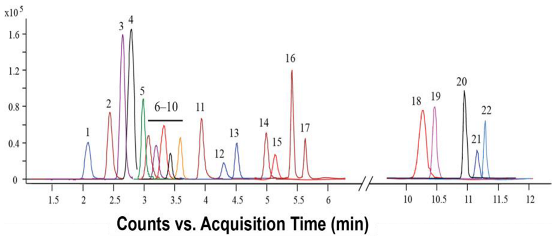

Figure 9.

Extraction workflows for bioactive compounds from plant residues (orange peels [77], eggplant [78], and broccoli [85]).

4.1.1. Conventional Methods

Conventional extraction methods primarily rely on organic or aqueous solvents under mild to elevated temperatures to isolate target compounds from plant-based residue matrices. Common techniques include maceration, commonly performed with ethanol, which has been used to extract phenolic compounds from passion fruit peels (Passiflora edulis) [80]; hot aqueous extraction, applied for flavonoid recovery from Phyllanti fructus [90]; and Soxhlet extraction, which has been effectively employed for phenolics in grape pomace [91]. Other methods, such as hydrodistillation, are typically employed to obtain essential oils from citrus peels, while alkaline and acid aqueous extractions are used to isolate biomolecules such as proteins from fruit and vegetable residues [91]. These approaches are favored for their simplicity, affordability, and accessibility, particularly in laboratories or small-scale industries that lack advanced technologies [5]. Table 5 summarizes the main applications, mechanisms, advantages, and drawbacks of these methods, and provides a comparative view of their performance in extracting BCs from edible plant-based residues.

Table 5.

Conventional extraction methods for bioactive compounds from edible plant-based residue.

For example, maceration and non-assisted ethanolic extraction are widely used for the recovery of polyphenols and flavonoids due to their simplicity and mild operating conditions [16,92]. However, they typically require extended extraction times—up to 12 h—and high solvent-to-solid ratios often exceeding 20:1 (mL solvent per g solid), which may limit their efficiency and sustainability in large-scale applications [13,91,93,94]. Hot aqueous extraction, often applied to hydrophilic compounds such as polysaccharides, is efficient but limited by the potential thermal degradation of sensitive compounds [16]. For instance, hot water extraction of β-glucans from oat bran at 90 °C has shown high yields, but partial depolymerization can occur due to heat exposure [95]. Soxhlet extraction, which continuously cycles hot solvent through the plant matrix, increases yield and recovery but is solvent- and energy-intensive; a Soxhlet run heating 300 mL of solvent over 20 h can consume around 36,000 kW of energy [13,96]. Hydrodistillation, primarily used to isolate volatile oils, eliminates the need for organic solvents but is restricted to thermostable compounds, such as limonene and linalool from citrus peels. For instance, hydrodistillation of Citrus sinensis (orange) peels involves chopping and weighing the peels, adding distilled water (5.5 mL/g peel), and heating at 100 °C under atmospheric pressure to release and transport volatile compounds; the vapors condense, separating the essential oil with a typical yield of 0.4–0.7%, containing around 20% d-limonene [77] (Figure 9). Furthermore, alkaline aqueous extraction is frequently used for protein recovery due to its ability to solubilize cell wall components, whereas acidic extraction can lead to the hydrolysis of other sensitive molecules, such as protocatechuic acid (a phenolic acid) and ascorbic acid, both of which are susceptible to degradation under acidic conditions [97].

To sum up, though these conventional methods have contributed significantly to the development of natural compound recovery processes, they often pose challenges related to sustainability. These include high energy consumption, such as in Soxhlet extraction or hydrodistillation, which may require continuous heating for 6–24 h and large volumes of solvent (e.g., up to 500 mL per 10 g of dry sample) [13,88]. Additionally, acidic and alkaline aqueous extractions often involve extreme pH conditions (pH < 2 or >10) and temperatures exceeding 80 °C, which can compromise thermolabile compounds [16]. These operational demands diminish the environmental and economic sustainability of such methods in large-scale applications.

4.1.2. Advanced Techniques

To overcome the limitations of conventional extraction, a wide array of advanced and green techniques has been developed in recent years. These methods aim to enhance extraction efficiency, reduce solvent and energy consumption, and improve the recovery of thermo- and photosensitive compounds from complex plant-based residue matrices. In the context of edible plant-based residues, integrating innovative technologies has allowed for more selective, scalable, and environmentally sustainable processes [5,16].

Among these, ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) facilitates the release of intracellular compounds, such as flavonoids and other phenolic compounds, through the mechanical disruption of plant cell walls, offering faster extraction with reduced solvent use [13]. The UAE enabled efficient extraction of polyphenol and flavonoid from passion fruit peels using a liquid-to-solid ratio of only 30 mL/g, while higher ratios did not improve the yield and even reduced flavonoid yield [98]. Similarly, in the extraction of phenolic compounds from Phyllanti fructus, UAE at 50 mL/g, 40 °C, and 200 W for 1 h resulted in higher yields compared to heating-reflux methods, while using less solvent and milder conditions [94]. Supercritical CO2 extraction (SFE) is especially efficient for lipophilic compounds, such as essential oils and carotenoids, using pressurized CO2 as a clean, non-toxic solvent [94]. Deep eutectic solvents (DES) are promising green alternatives for extracting phenolic compounds, though their high viscosity and limited reusability remain drawbacks [5,99]. Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) accelerates the extraction process by heating the matrix and solvent internally, improving yields of polar bioactives with minimal degradation [16]. Enzymatic extraction uses enzymes such as cellulases or pectinases to break down plant cell walls and release bound phenolics, showing high selectivity and mild operating conditions [13]. Membrane-based processes, such as ultrafiltration and nanofiltration, are commonly applied post-extraction to purify or concentrate compounds without the need for heat, thereby preserving bioactivity [88]. Ultrasound-assisted micronization, an emerging method, enhances the solubility and bioavailability of extracted bioactives by reducing particle size [5]. Although ionic liquids (ILs) were studied as alternative solvents due to their customizable properties, their toxicity, cost, and poor biodegradability limit their suitability for food or nutraceutical extractions [16,99].

Overall, these advanced techniques exhibit a significant improvement over conventional methods in terms of yield, selectivity, and environmental performance. Table 6 reviews the main advanced extraction techniques, highlighting their typical applications, operational conditions, and major advantages and limitations.

Table 6.

Emerging green extraction technologies for bioactive compounds from plant by-products.

4.1.3. Comparative Overview and Outlook of Extraction Methods

The advantages and limitations of conventional and advanced extraction methods were described in detail in the previous section, underscoring their respective suitability depending on the target compounds, processing conditions, and technological constraints. Figure 10 complements this analysis by summarizing the most relevant extraction approaches applied to edible plant-based residue, mapping each method to its commonly recovered bioactives.

Figure 10.

Comparative overview of conventional and advanced extraction methods for plant bioactive compounds.

Table 7 compiles detailed information on conventional and advanced extraction methods used to recover BCs from distinct types of plant-based residues. Only those cases for which the cited references explicitly reported operational parameters, including solvent type and concentration, temperature, pressure, pH, energy and solvent consumption, extraction time, and bioactive yields, are included. This comparative overview aims to highlight technological differences, demonstrate efficiency trends, and support the selection of the best extraction strategies for the sustainable valorization of plant residues.

Table 7.

Conventional and advanced extraction methods for bioactive compounds from plant-based residue, including detailed conditions.

This comparative overview highlights the growing potential of non-conventional technologies, particularly those aligned with green chemistry principles and process intensification strategies. However, selecting the best extraction route is still case-specific, as no single method offers a universal solution across diverse plant matrices and compound classes.

Optimizing existing techniques or developing hybrid or integrative approaches could enhance extraction efficiency while minimizing environmental impact. These strategies could include combining enzymatic hydrolysis with membrane separation or coupling ultrasound with green solvents. In addition, future studies should assess the scalability, cost-effectiveness, and regulatory compliance of the process to enable industrial adoption [16]. These perspectives are discussed in the following section.

4.2. Characterization Methods

For the precise recovery process of bioactives, once extracted, these compounds must be properly characterized to figure out their chemical composition, structural features, and potential biological activity. An exact characterization is crucial to assess purity, functionality, and application potential in fields such as food, pharmaceuticals, or cosmetics. This is primarily achieved through the use of spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques, which enable the identification, quantification, and structural elucidation of metabolites present in complex plant matrices. To select a proper analytical method, it is necessary to consider factors such as the nature of the target compound, matrix complexity, required sensitivity, and study objectives [13,45,88]. To better illustrate how these criteria influence method selection, Table 8 provides a brief overview of the main considerations and suggests which analytical techniques are best suited under each condition.

Table 8.

Key factors in the selection of analytical techniques for bioactive compound characterization.

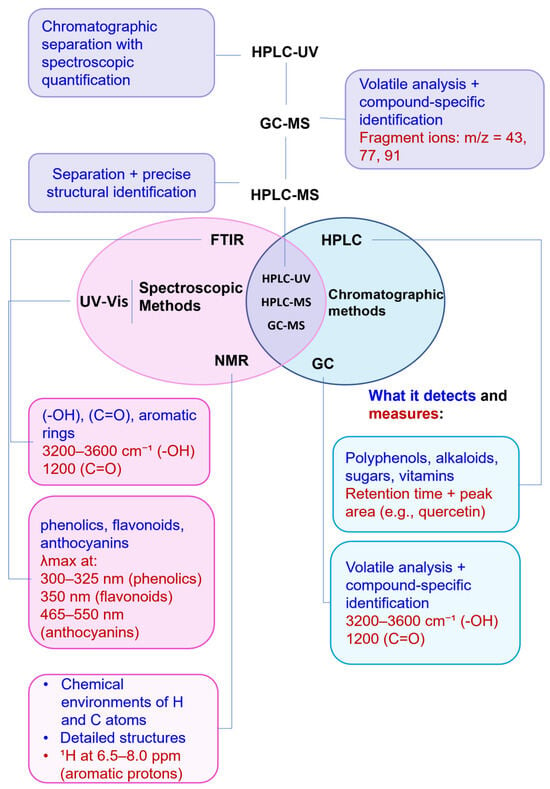

4.2.1. Spectroscopic Methods

Spectroscopic techniques are widely employed for the preliminary characterization of plant-derived bioactives, due to their speed, low sample consumption, and non-destructive nature. Methods, such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), provide insight into the functional groups present in a sample by analyzing vibrational transitions of molecular bonds [45]. Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis) is commonly employed to quantify phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and other chromophoric groups by measuring light absorbance at specific wavelengths. In comparison, more complex and resource-intensive, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can provide detailed structural elucidation of pure compounds and can confirm molecular formation [92]. These methods are particularly valuable for rapid screening or complementing more precise separation-based techniques.

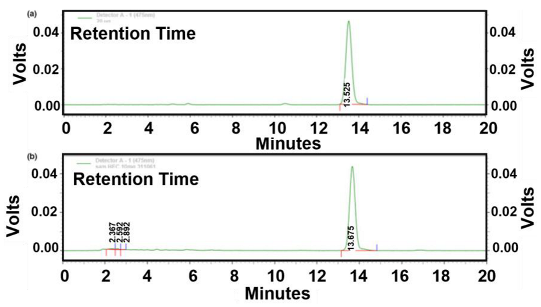

4.2.2. Chromatographic Methods

Chromatographic techniques are essential for separating and quantifying compounds from complex plant matrices, offering higher resolution and precision compared to spectroscopic methods [9,103,104]. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is widely used for the analysis of phenolic compounds and alkaloids due to its versatility and compatibility with various detectors, including UV, diode array detectors, and mass spectrometry (MS) [13]. The coupling of HPLC with MS (HPLC-MS) or tandem MS (MS/MS) provides detailed structural and molecular mass information, crucial for compound identification and metabolomic profiling [88]. Gas chromatography (GC), used for volatile and semi-volatile compounds such as essential oils or fatty acids, also benefits from MS coupling (GC-MS) for improved compound specificity [105]. These couplings enable high-precision analysis of target metabolites in plant-based residue extracts.

4.2.3. Highlight and Visual Summary of Characterization Methods

Spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques play essential and distinct roles in characterizing plant-derived BCs. Spectroscopic methods are valuable in early-stage analyses due to their non-destructive nature, rapid execution, and ability to reveal key functional groups and structural motifs [106]. They are widely utilized for preliminary screenings, qualitative fingerprinting, and confirmation of chemical structures, particularly when working with purified samples [45,92].

In contrast, chromatographic techniques like HPLC and GC, when coupled with MS, e.g., (HPLC-MS, GC-MS), provide high-resolution separation and precise quantification of individual compounds within complex plant extracts. They are indispensable for metabolite profiling, quantifying low-abundance molecules, and ensuring reproducibility [13,88].

In many cases, spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques are used together to complement each other, with spectroscopy providing rapid assessment and structural insights, and chromatography facilitating targeted quantification and confirmation (Figure 11). For example, vis absorption spectroscopy can be used to estimate TPC, while HPLC-MS can confirm and quantify specific flavonoids such as quercetin or catechin with high accuracy [107]. To illustrate the type of outputs typically obtained with these techniques, Table 9 provides selected chromatograms and spectral examples showing the characteristic peaks of representative BCs from various plant-derived matrices.

Figure 11.

Visual representation of characterization methods.

Table 9.

Representative chromatograms and spectra for selected bioactive compounds from various plant sources.

Complementarily, Table 10 summarizes the spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques, along with key analytical parameters, used for identifying and quantifying selected BCs. This compilation aims to provide a clear reference for the analytical conditions applied in the reviewed studies, ensuring methodological transparency and easing reproducibility in future research.

Table 10.

Summary of analytical techniques and key parameters for plant-based bioactive compounds.

To better illustrate these synergies, Figure 11 presents a comparative visual summary of the most relevant analytical techniques, highlighting their signal types, compound targets, and degree of specialization across the characterization pipeline.

5. Biotechnology Applications

Following the extraction and characterization of BCs from plant-based residues, it is important to explore their practical applications within the biotechnology field. These naturally derived molecules, previously explored, exhibit many biological activities. Their functionality has driven significant interest in using them across key biotechnological sectors. This section highlights how these bioactives are currently being integrated into environmental, medical, and food industry biotechnology, emphasizing their value in sustainable innovation and the development of novel therapeutic and ecological solutions.

5.1. Environmental Remediation

5.1.1. Wastewater Treatment and Soil Remediation

Among the BCs found in the analyzed agro-food plant residues, several exhibit strong potential for application in environmental remediation. Specifically, functional groups, such as flavonoids and other phenolics and carboxylic acids, in banana, citrus, and watermelon by-products have demonstrated effective binding abilities for heavy metals and toxic metalloids in wastewater and contaminated soils [11,14,58,111].

Naturally rich in pectin and polyphenolic compounds, banana peels have been widely studied as biosorbents.

Under optimized conditions, unmodified banana peel shows adsorption capacities of 3.2 mg/g for Cu(II) and 2.8 mg/g for Zn(II), mainly through ion exchange and surface complexation via –OH and –COOH groups, following pseudo-second-order kinetics and Langmuir isotherms [111]. The mechanisms have been studied from kinetic, isotherm, and thermodynamic perspectives, with demonstrated regeneration and reuse potential [14]. Chemical or structural modifications can substantially enhance performance: acid-treated banana peel reaches 161 mg/g for Cr(VI) [112], magnetic Fe3O4/banana peel/alginate composites achieve 370.4 mg/g for Cr(VI) (~94% removal) [113], and MgO–banana peel composite beads remove Cd(II) up to 455 mg/g [114]. Additional treatments improve uptake of Ni(II) to 29.2 mg/g [35], fluoride to 39.5 mg/g [115], methylene blue to ~33 mg/g, and atrazine to 14 mg/g [116], underscoring the adaptability of banana-based biosorbents to a broad spectrum of contaminants. A summary of these capacities is provided in Table 11, highlighting their versatility in water treatment applications.

Beyond banana-based adsorbents, several other agro-food residues also show high adsorption potential for diverse contaminants. Citrus peels, when entrapped in calcium alginate beads, remove Se(IV) at capacities of 116 mg/g with stable performance over multiple reuse cycles, benefiting from the combined effects of the phenolic matrix and alginate’s ion-exchange properties [58]. Watermelon rind, rich in lignocellulosic material and phenolics, exhibits high removal efficiency for Cr, Pb, and organic dyes in its pyrolyzed or chemically activated forms, achieving Pb(II) adsorption capacities of 95–143 mg/g [11,117]. Likewise, lychee and melon peels grafted with acrylic acid reach Pb(II) removal up to 143 mg/g, attributed to the increased density of surface carboxylic groups achieved through green grafting processes [117].

Collectively, these case studies illustrate the viability of plant-based residues as efficient and low-cost biosorbents for water treatment and soil remediation. Their transformation into functional materials requires minimal processing, aligns with green chemistry principles, and reinforces the circular valorization strategies promoted in this study.

Table 11.

Adsorption capacities of banana-based adsorbents for different contaminants.

Table 11.

Adsorption capacities of banana-based adsorbents for different contaminants.

| Contaminant | Banana-Based Adsorbent | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(II) | Banana peel (unmodified) | 3.2 | [111] |

| Zn(II) | Banana peel (unmodified) | 2.8 | [111] |

| Cr(VI) | Banana peel (acid-treated) | 161 | [112] |

| Cr(VI) | Fe3O4/banana peel/alginate composite (MAB) | 370.4 (≈94% removal) | [113] |

| Pb(II) | Banana peel activated carbon–Al2O3–chitosan composite | 57.1 | [118] |

| Cd(II) | Banana peel + MgO composite beads (BPMB) | 454.5 | [114] |

| Ni(II) | Banana peel (DTPA-modified) | 29.2 | [119] |

| Methylene blue (dye) | Banana peel powder (no chemical treatment) | ~33 | [116] |

| Fluoride (F−) | Banana peel dust (modified) | 39.5 | [115] |

| Atrazine (herbicide) | Banana peel (H3PO4-pretreated) | 14 | [116] |

5.1.2. Bioenergy Production and Air Pollution Control

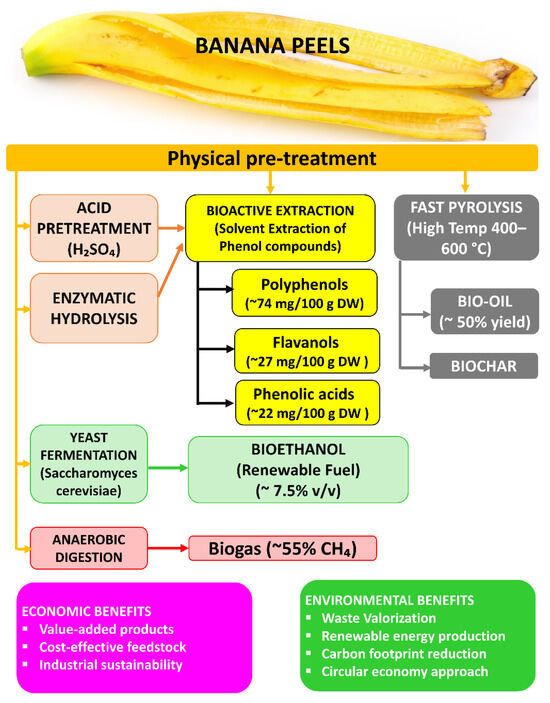

The valorization of plant-based residue as feedstock for bioenergy offers a dual advantage: the production of renewable fuels and the mitigation of pollution associated with fossil fuels and organic waste disposal. For example, residues rich in sugars (such as fruit juices and peels) or starch (like tubers) can be hydrolyzed and fermented into bioethanol (anhydrous ethanol). Recent studies show that by-products from banana, papaya, and other tropical fruits can be fermented by Saccharomyces cerevisiae to produce ethanol concentrations of around 7–8% (v/v) in the fermentation broth [15]. After distillation to fuel-grade (≥99% ethanol), this is suitable for high-ethanol blends such as E85. High conversion efficiencies (often exceeding 70–80% of the theoretical yield) have been reported for these residues under optimized conditions [120]. This type of bioethanol is considered essentially carbon-neutral, as the CO2 released during combustion was previously fixed by the plants. According to life-cycle analyses, waste-derived ethanol can reduce net GHG emissions by ~80% compared to gasoline [121]. Consequently, using bioethanol from fruit waste in fuel blends (e.g., E10, E85) helps displace petroleum usage and lowers overall CO2 emissions [121].

In addition, anaerobic digestion (AD) of plant-based residue (peels, pulps, and leafy residues) produces biogas, a renewable mixture of CH4 and CO2. Food waste typically has high moisture and volatile solids (~90% VS) [122] and thus is easily biodegradable, yielding significant biogas volumes. In fact, the biochemical methane potential of food waste ranges roughly between 200 and 670 m3 CH4 per tonne, making it highly suitable for biogas production [122]. Fruit and vegetable market waste streams are also optimal for AD; studies show they can be digested stably without inhibitory effects, given their favorable nutrient balance and lack of persistent toxins [123]. Co-digestion of mixed produced waste often proceeds with minimal risk of acidification or metal toxicity, resulting in steady biogas generation [123]. The produced biogas (typically ~50–60% CH4) can be used for heating and electricity or upgraded to biomethane for grid injection. The remaining digestate is a nutrient-rich biofertilizer, closing the nutrient loop in a circular economy. Overall, biogas from food waste captures methane that would otherwise escape from landfills and directly displaces fossil natural gas in industrial and thermal applications, thus curbing GHG emissions and air pollutants from fossil fuel combustion. For instance, AD of banana peels yields biogas with about 53–57% methane content [15], which can supplement or replace natural gas. In this approach, diverting food waste to AD reduces landfill methane emissions and provides renewable energy with lower NOx, SO2, and particulate emissions than coal or oil.

Fast pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., pumpkin shells, banana peels, and vegetable stalks) produces bio-oil as the main product and biochar as a minor by-product [124]. Bio-oil is a viscous liquid fuel that can be used for heating or upgraded to transportation fuel. Feedstocks with high volatile content (approximately 70–90% on a dry basis) are ideal for maximizing bio-oil yield [124]. For example, banana peels have ~85% volatile matter [15], and orange peels can yield ~50–55 wt% bio-oil under optimal fast pyrolysis conditions [7]. The biochar produced in fast pyrolysis is a smaller fraction (often <15–20 wt%), but it plays a critical environmental role. When applied to soils, biochar sequesters carbon and improves soil structure, contributing to long-term CO2 mitigation [125]. Biochar’s carbon is recalcitrant, implying it can remain in soil for decades to centuries without decomposing [125]. This carbon sequestration potential makes biochar a negative emissions strategy. Furthermore, biochar can enhance pollutant adsorption; for instance, biochars derived from food waste or citrus peels have been utilized as biosorbents to remove heavy metals and organic pollutants from water and soil [121]. Although this pollution control application is secondary within food waste stream valorization, it provides an additional environmental benefit by repurposing biochar for contaminant capture. Overall, the thermochemical conversion of food residues into bio-oil and biochar transforms otherwise problematic waste into valuable fuels and carbon-rich materials, supporting efforts in climate change mitigation and soil remediation [125].

In summary, the conversion of edible plant residues into bioethanol, biogas, and bio-oil supports circular economy models and helps reduce air pollution by substituting fossil fuels (e.g., gasoline, diesel, and natural gas) with cleaner, renewable alternatives. The combustion of these biogenic fuels generally results in lower emissions of NOx, SO2, and particulate matter, due to their lower sulfur and ash contents, as well as the use of modern emission control technologies in bioenergy systems [121]. At the same time, diverting organic waste from incineration or landfilling avoids the uncontrolled release of pollutants and GHG from those disposal methods. For instance, one fruit waste (banana peels) and one vegetable waste (potato peels) can together yield several products through different pathways. As shown in Figure 12, banana peels can be converted into bioethanol, bio-oil, biogas, biochar, and polyphenols, generating both economic and environmental benefits.

Figure 12.

Valorization pathways of banana peels into bioethanol, bio-oil, biogas, biochar, and polyphenols.

Likewise, potato peels (a starchy vegetable residue) can be saccharified and fermented to ethanol (up to ~0.38 kg ethanol per kg dry peel) [120], and the residual solids and peel fibers can produce biogas via AD and bio-oil/biochar via pyrolysis. Each of these waste-to-product streams is supported by studies reporting high yields and efficiencies [120,122].

Many of these residues also contain valuable BCs, such as antioxidants like polyphenols, carotenoids, and vitamins, which can be recovered either before or after the energy conversion processes and used in nutraceuticals, functional foods, or environmental remediation [15,126]. For instance, citrus peels are rich in hesperidin and limonene, while banana peels contain flavonoids and vitamin A precursors [15]. Recovering such bioactives adds economic value and can lead to sustainable health and environmental products [126,127]. These approaches (including biochemical, thermochemical, and extractive) demonstrate a relevant utilization of food waste that produces renewable energy, reduces pollution, and yields co-products for environmental and health applications.

5.1.3. Economical Snapshot

Several high-growth markets support the valorization of plant-derived residues into remediation agents and renewable energy carriers. The biochar market, driven by applications in soil amendment, carbon sequestration, and contaminant adsorption, was estimated at USD 541.8 million in 2023. It is expected to grow to USD 1.35 billion by 2030 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.9%, as sustainable agriculture and carbon credit programs accelerate adoption [128].

Meanwhile, the biogas market, which harnesses AD of plant wastes to produce methane-rich renewable gas and nutrient-rich digestate, reached USD 65.53 billion in 2023 [129]. It is projected to reach USD 87.86 billion by 2030, expanding at a CAGR of 4.3% from 2024 to 2030, driven by supportive renewable energy policies and the growing imperative for a circular economy [129]. These figures underscore the strong commercial momentum behind turning bioactive-rich plant residues into high-value remediation materials and renewable energy, reinforcing circular economy strategies and sustainability goals. Table 12 provides an overview of the diverse environmental applications of these compounds, including their roles in bioremediation, wastewater treatment, bioenergy production, and pollutant degradation, explaining how agro-industrial residues can be integrated into sustainable environmental solutions.

Table 12.

Environmental applications framework diagram.

5.2. Healthcare and Medical Biotechnology

5.2.1. Biotechnological Innovations in Diagnostics

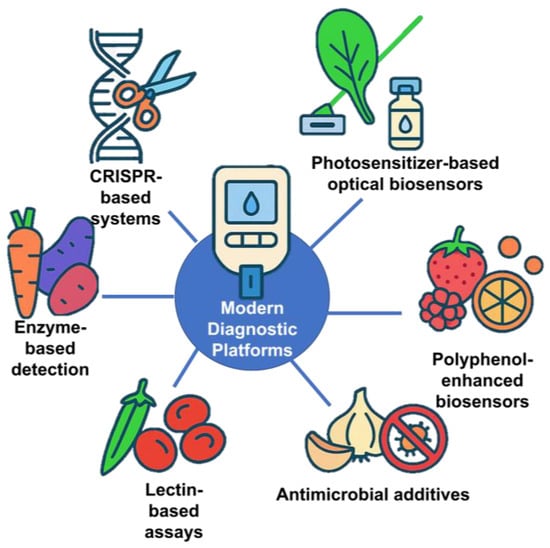

Medical diagnostics play a crucial role in early disease detection, patient stratification, and monitoring treatment outcomes. Recent advances in biotechnology have leveraged bioactive molecules, such as enzymes, antibodies, and nucleic acids, to create extremely sensitive, rapid, and portable diagnostic platforms.

A key breakthrough has been adapting the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/Cas system, originally a bacterial immune defense mechanism, for molecular diagnostics [132]. CRISPR is a genetic tool derived from bacteria that recognizes and cuts foreign viral DNA using a protein called Cas (CRISPR-associated) [132]. This natural system has been repurposed in biotechnology to target specific DNA or RNA sequences with high precision. CRISPR-based biosensors can specifically recognize nucleic acid sequences from pathogens, cancer markers, or genetic mutations, enabling ultrasensitive detection with minimal sample preparation [133,134,135]. These assays, often implemented in portable or even wearable formats, allow point-of-care testing that is faster and more accessible than conventional laboratory methods.

In addition to CRISPR-based systems and monoclonal antibody platforms, plant-derived biomolecules from fruit and non-fruit crops have been integrated into diagnostic technologies, offering cost-effective and sustainable alternatives for assay development. Peroxidase enzymes from vegetables such as carrot (Daucus carota) and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) exhibit high catalytic activity comparable to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) [136], enabling their use as low-cost enzyme labels in colorimetric immunoassays by catalyzing chromogenic reactions in the presence of hydrogen peroxide [136].

Polyphenol-rich fruits such as raspberry (Rubus idaeus), lemon (Citrus limon), and orange (Citrus sinensis) provide antioxidant compounds that, when incorporated into biosensor matrices, improve stability, reduce background interference, and extend shelf life; raspberry extracts, for instance, have been used as natural reducing and stabilizing agents in nanoparticle-based sensors [137]. Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) chlorophyll derivatives function as photosensitizers in optical biosensors, where immobilized pigments can drive light-activated signal amplification or serve as fluorescence quenchers in the presence of target analytes, enabling sensitive and low-power detection [138].

Additionally, organosulfur compounds from garlic (Allium sativum) and onion (Allium cepa), including allicin and thiosulfinates, possess broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity that can be integrated into diagnostic strips or sample collection devices to prevent contamination and preserve assay integrity [139].

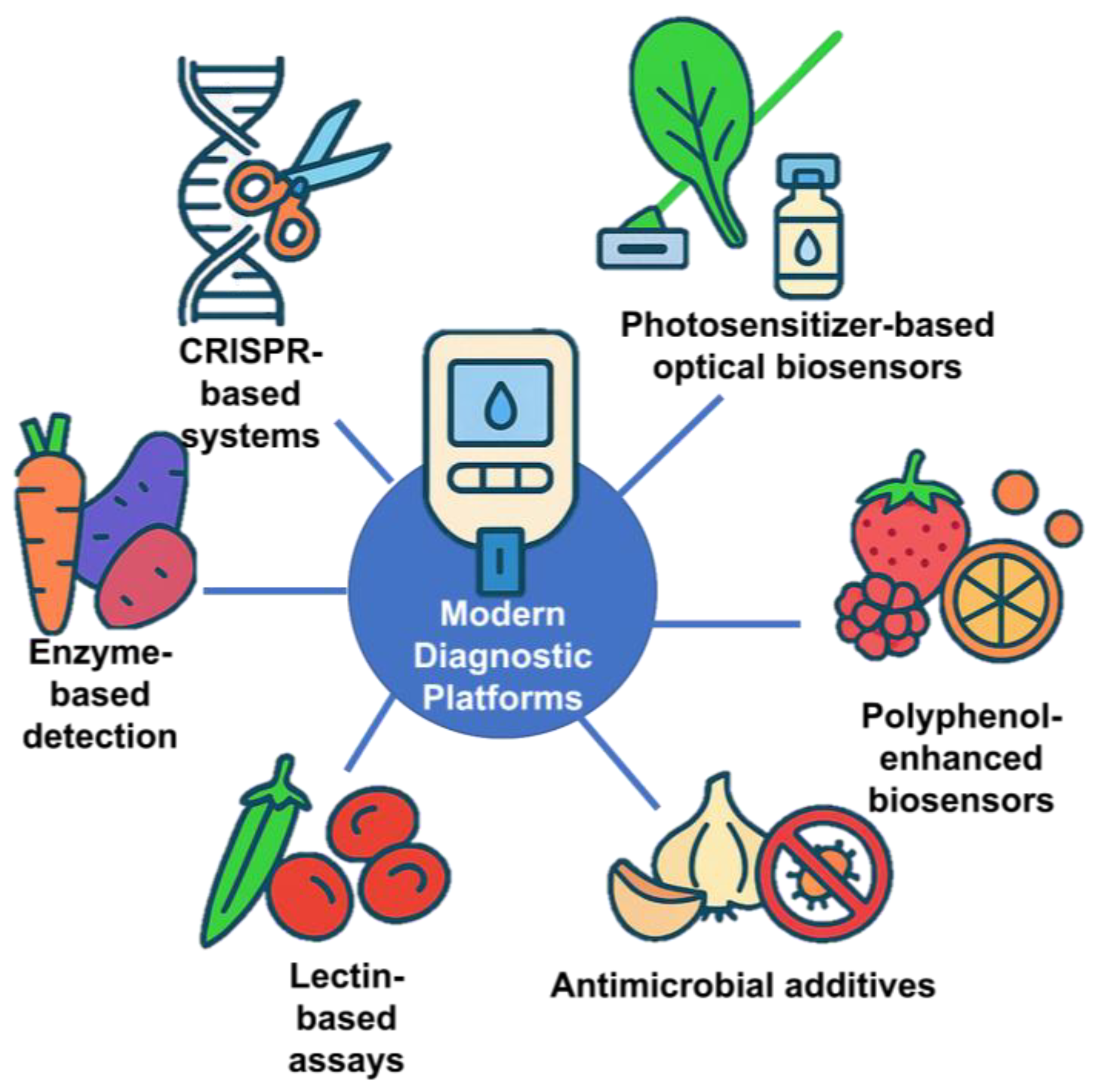

Collectively, these examples highlight the diverse functional roles of plant-sourced enzymes, antioxidants, pigments, and antimicrobial metabolites in enhancing the sensitivity, specificity, durability, and sustainability of modern diagnostic platforms. Figure 13 demonstrates a schematic representation of plant-derived biomolecules and CRISPR-based technologies applied in modern medical diagnostics. The growing demand for such technologies is driving significant expansion in the diagnostics market, highlighting their transformative potential in modern medicine [140].

Figure 13.

Integration of modern diagnostic platforms with food and biotechnology applications.

5.2.2. Biotechnology-Based Materials and Therapies

Recently, biotechnology has significantly expanded the therapeutic applications of BCs, particularly in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. A promising area is using plant extract–derived nanomaterials for wound healing. These nanoparticles, loaded with bioactive phytochemicals, exhibit antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties that enhance tissue regeneration, promote fibroblast proliferation, and accelerate epithelialization in chronic and acute wound models [141].

Simultaneously, three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting has emerged as a transformative platform for fabricating complex tissue constructs using bioinks composed of hydrogels, cells, and signaling molecules. This technology enables the creation of customized, vascularized grafts for applications such as bone, cartilage, and skin repair. Preclinical studies have demonstrated high cell viability and functional integration of bioprinted tissues in vivo, indicating strong translational potential [142].

Moreover, decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) biomaterials provide a native-like environment that supports cell adhesion, differentiation, and tissue remodeling. Their biochemical composition closely mimics the natural microenvironment of target tissues, making them ideal scaffolds for regenerative therapies and clinical implantation [143].

In parallel, organ-on-a-chip systems and engineered disease models enable more accurate in vitro simulations of human physiology. These microfluidic platforms use living cells and tissue-like architectures, facilitating drug testing, toxicity screening, and personalized treatment assessment while reducing dependence on animal models [144].

These innovations, when combined, reflect the convergence of natural bioactives, smart biomaterials, and engineering strategies in shaping the future of biomedical therapies. Table 13 presents representative examples of biotechnology-based materials and therapeutic strategies derived from fruit and non-fruit plant species evaluated in this study, highlighting their BCs, applications, and recent performance reports.

Table 13.

Biotechnology-based materials and therapeutic applications derived from selected fruit and non-fruit plant species.

5.2.3. Economical Snapshot

Given this wide opportunity of therapeutic and diagnostic applications enabled by BCs, it is vital to consider their commercial relevance across key biotechnology sectors. The economic impact of BC–based technologies is rapidly expanding across multiple healthcare sectors. Advanced wound care products, such as antimicrobial dressings and antioxidant hydrogels, reached a global value of USD 11.25 billion in 2024, projected to grow to USD 14.87 billion by 2030 [140]. Similarly, the regenerative medicine sector is expected to grow more than double, from USD 35.47 billion in 2024 to USD 90.01 billion by 2030, with 3D bioprinting and tissue scaffolds driving much of this growth [140].

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory therapies, often derived from natural sources, are also high-value markets. Antioxidant ingredients alone are forecasted to grow from USD 2.4 billion (2025) to USD 6.4 billion (2035), while anti-inflammatory drugs are expected to reach USD 233.6 billion by 2032 [140]. Meanwhile, the in vitro diagnostics (IVD) market, which strongly depends on bioactive reagents, is projected to grow from USD 108.3 billion in 2024 to USD 150.13 billion by 2030 [140].

These trends highlight the strategic and commercial importance of BCs in diagnostics, regenerative therapies, and biopharmaceutical development, establishing them as a central pillar in the future of personalized and precision medicine. A summary of key application areas and market projections is presented in Table 14.

Table 14.

Market outlook for selected biotechnology applications of bioactive compounds.

5.3. Industrial and Food Biotechnology

5.3.1. Bioprocessing for Sustainable Production

The valorization of agro-food plant residues analyzed in this study reveals a rich profile of BCs such as flavonoids, polyphenols, anthocyanins, and carotenoids. Various extraction and bioconversion techniques are implemented to maximize their recovery and enhance their bioavailability.

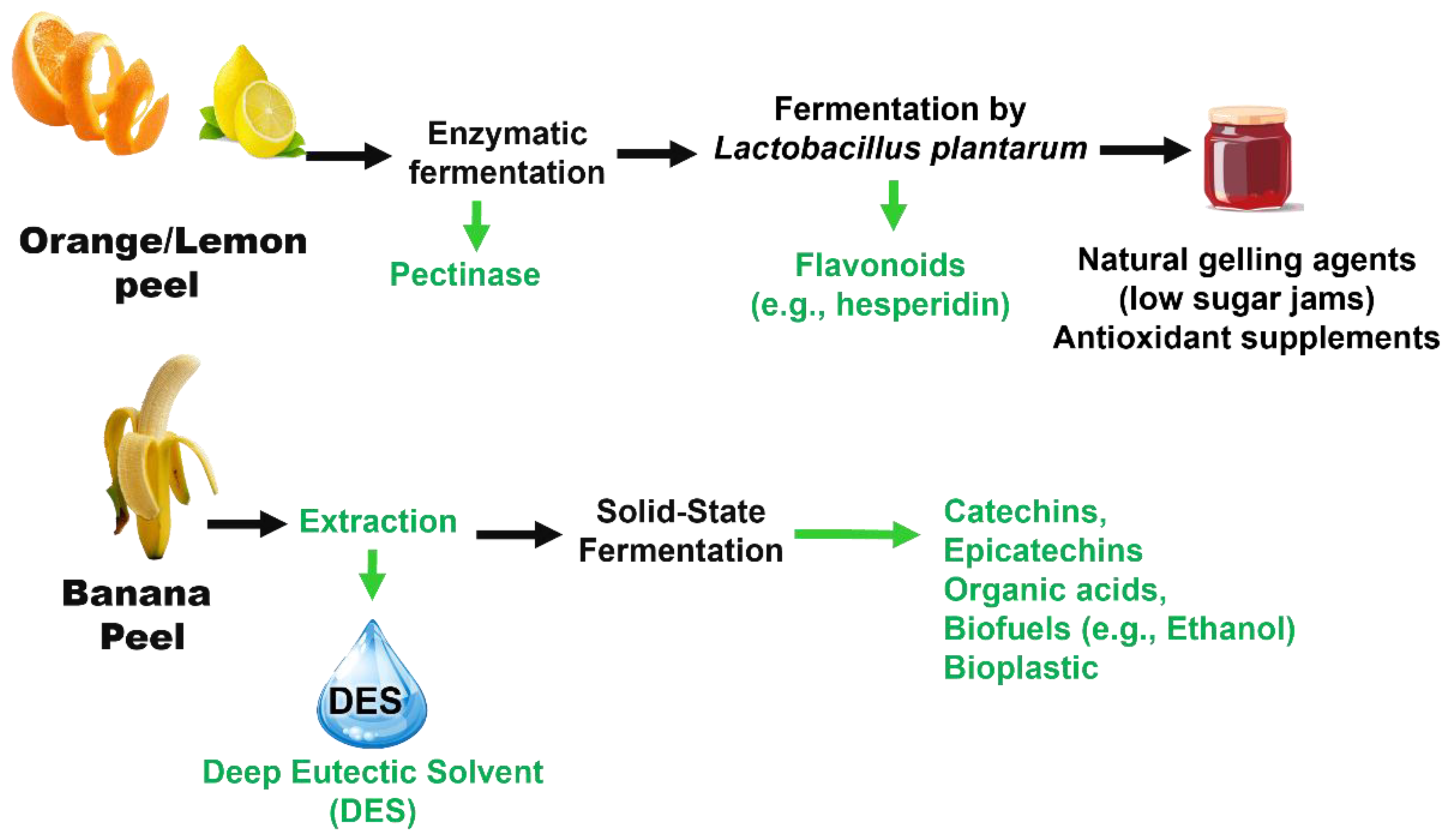

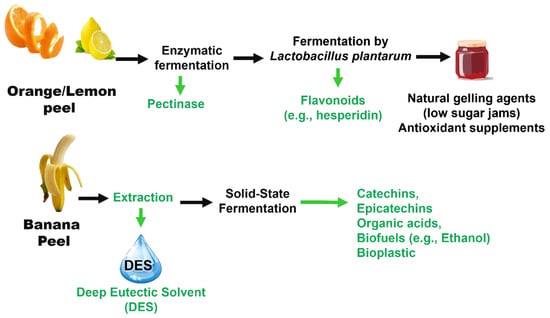

Citrus peels (e.g., oranges and lemons) contain significant levels of flavonoids, such as hesperidin. Enzymatic extraction using pectinase, coupled with Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation, can increase total flavonoids by 30%, which are widely used as functional antioxidant supplements [37,38,127].

Banana peel waste is rich in catechins and epicatechins. DES extraction methods achieved over 85% phenolic recovery [30]. In comparison, solid-state fermentation with Aspergillus niger enhanced the production of organic acids and ethanol by 20%, which is beneficial for the bioplastic and biofuel industries [32].

Tomato pomace is a notable source of lycopene and antioxidants [34]. Spouted bed drying prior to fermentation with Lactobacillus casei enabled lycopene recovery of up to 92% and a 30% increase in antioxidant activity [34,47]. Supercritical fluid extraction further enhanced polyphenol yields [150].

Raspberry pomace, eggplant peels, watermelon rind and seeds, and onion and garlic skins were also processed via enzymatic, ultrasonic, and microbial methods to recover flavonoids, anthocyanins, and antimicrobial compounds, demonstrating the versatility of bioprocessing strategies [26,78,98,151]. For instance, eggplant peel extracts yielded up to 570.1 mg/g DW of total anthocyanins and 17 mg CE/g of total flavonoids [76,78]; watermelon residues contained 6.1 mg GAE/g DW of polyphenols and 3.4 mg/g DW of total flavonoids [98]; raspberry pomace showed 24 mg GAE/g DW of TPC and 7.1 mg C3G/L of anthocyanins [36]; and onion skins reached 349 mg GAE/g of TPC and 259 mg/L of quercetin [73].

These integrative bioprocessing techniques, which combine enzymatic hydrolysis, green solvents, and microbial fermentation, optimize the extraction and transformation of BCs from diverse plant residues, thereby advancing sustainable production within a circular bioeconomy framework [12,37].

Figure 14 illustrates two representative examples of bioprocessing approaches applied to plant-based residues: citrus peels and banana peels. It outlines the extraction and microbial transformation steps that lead to the recovery of BCs with potential applications in the food, nutraceutical, and biofuel industries. Figure 14 is based on data and methodologies described in previous studies [30,32,37,38,127].

Figure 14.

Biotechnological processing of citrus and banana residues into high-value bioactives [30,32,37,38,127].

5.3.2. Fermentation Technology in Food Production

Fermentation is a pivotal tool for enhancing the availability and functionality of BCs in plant residues. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as Lactobacillus species, have demonstrated high efficiency in releasing bound phenolics from citrus peels and tomato pomace, thereby improving antioxidant capacity and bioaccessibility [47,127].

Fungal solid-state fermentation (SSF) using Aspergillus niger and Rhizopus oryzae has been effective in enriching the flavonoid content and reducing anti-nutritional factors in banana peels, thereby facilitating the bioconversion into ethanol and organic acids [30].

Fermentation also improves the sensory profiles and shelf life of leafy and allium vegetable residues. Onion and garlic skins, rich in quercetin 14.5–5110 µg/g DW in raw tissues; [101]; and 14.9–48.53 mg/g DW in fermented extracts [87]; and kaempferol 3.2–481 µg/g DW in raw tissues [101], produce antimicrobial and antioxidant fermented extracts suitable for nutraceutical and functional food formulations as natural preservatives due to their antimicrobial phenolic content [102,150].

Moreover, fermentation converts dietary fibers from sweet potato and carrot peels into oligosaccharides with prebiotic effects promoting gut microbiota health [35,66]. Thus, fermentation optimizes the functional and nutritional profiles of agro-food residues while offering eco-friendly processing alternatives.

5.3.3. Use of Genetically Modified Microorganisms in Manufacturing

Genetically modified microorganisms (GMMs), such as engineered Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, improve the production and purity of enzymes, flavonoids, and tocopherols derived from citrus and tomato residues [37,47]. Specifically, the overexpression of polyphenol-metabolizing enzymes in these strains has been shown to significantly enhance the yields and quality of BCs, facilitating the valorization of citrus peels and tomato pomace for the manufacture of vitamin-enriched supplements and antioxidant-rich beverages [37,47].

In citrus waste valorization, recombinant S. cerevisiae expressing heterologous naringenin chalcone synthase and chalcone isomerase has achieved naringenin production of ~180 mg/L from orange peel hydrolysates [121]. Likewise, Escherichia coli engineered with flavonoid biosynthetic pathways can convert hesperidin extracted from citrus residues into hesperetin with greater than 90% molar conversion efficiency [47].

For tomato waste streams, metabolic engineering of Lactobacillus plantarum has been applied to enhance the synthesis of vitamin E (tocopherols) from tomato seed oil, achieving titers of up to 55 mg/L [47]. In addition, engineered S. cerevisiae strains overexpressing carotenoid biosynthesis genes from Pantoea ananatis have been used to convert lycopene from tomato pomace into β-carotene at yields exceeding 30 mg/g dry biomass [47].

These GMM-based bioprocesses not only increase the extraction efficiency of target molecules but also reduce downstream purification costs by minimizing the formation of unwanted by-products. Overall, their integration into agro-industrial waste valorization enables the recovery of higher-value products from residues that would otherwise be discarded, aligning with the principles of the circular bioeconomy and sustainable manufacturing practices.

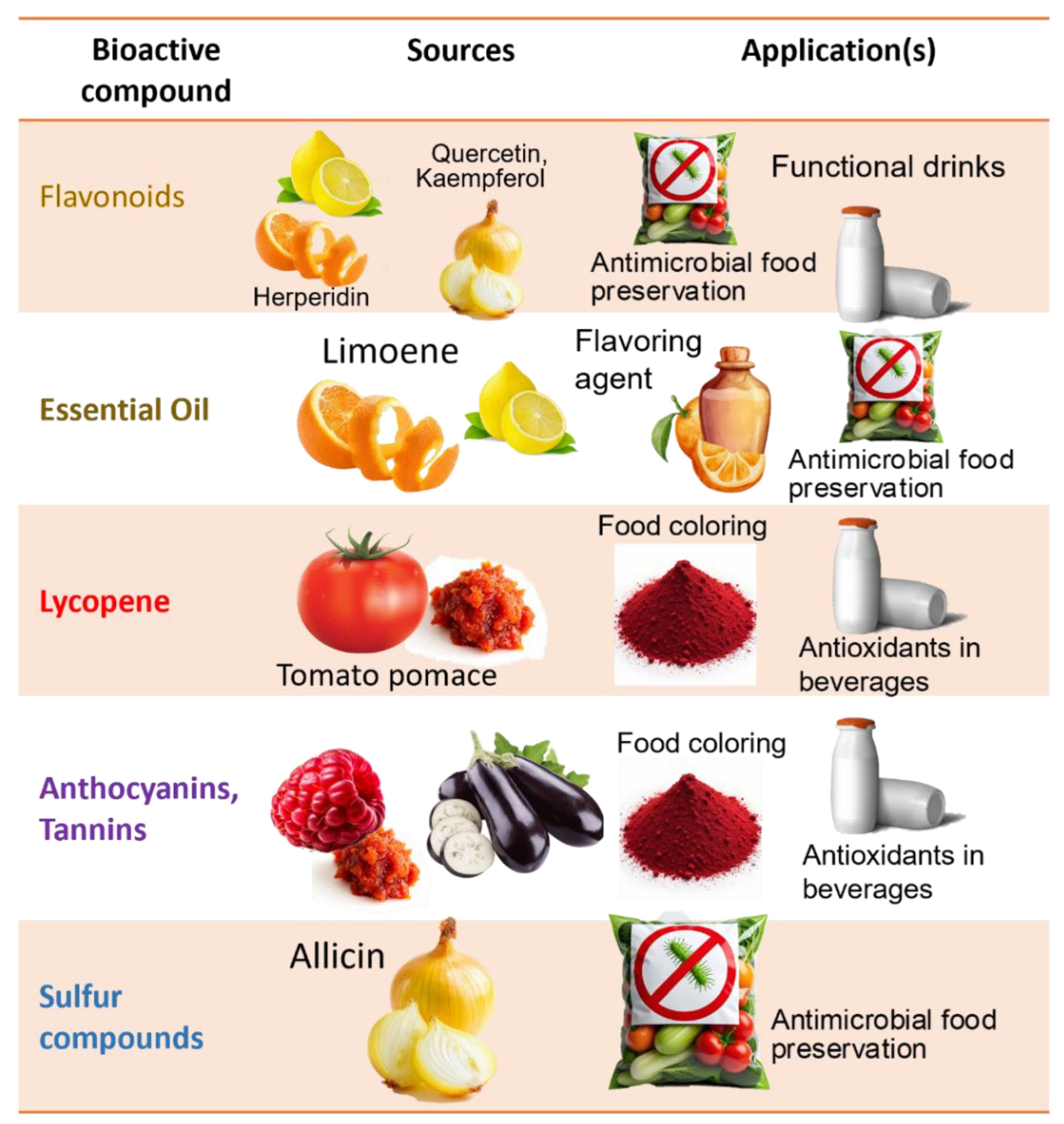

5.3.4. Industrial and Food Biotechnology Applications Framework

The practical application of bioprocessing and fermentation techniques on fruit and vegetable residues supports the production of functional food ingredients, natural preservatives, and biodegradable materials within a circular bioeconomy.

For instance, enzymatic and microbial treatments of citrus peels yield flavonoid-rich extracts, which are used as antioxidant additives in beverages and supplements [38,119]. In the case of banana peels, DES extraction followed by fungal fermentation facilitates the production of bioethanol and organic acids [30], as well as the isolation of catechins and epicatechins, compounds increasingly used in functional beverages and natural food colorant systems due to their pigment stability [30,32].

Tomato pomace processing through spouted bed drying and LAB fermentation enhances the recovery of lycopene—a potent antioxidant and natural red pigment used to improve shelf life and color in functional dairy and bakery products [34,47,150]. Supercritical fluid extraction from this residue also allows the concentration of polyphenols, supporting applications in natural food preservatives and emulsifiers.

Additionally, underutilized residues such as raspberry pomace and eggplant peels have shown potential for the recovery of anthocyanins and tannins (i.e., natural antioxidants and antimicrobials) used as colorants and preservative agents in yogurt, meat coatings, and nutraceutical gummies [26,36,78]. Watermelon rind and seeds processed through UAE and enzymatic hydrolysis provide amino acids, including citrulline (61.4 mg/100 g fresh weight) and arginine (53.8 mg/100 g fresh weight) [151], as well as polyphenols relevant for protein enrichment in sports nutrition and plant-based milk alternatives [152].

Onion and garlic skins, rich in quercetin, a potent antioxidant flavonoid and organosulfur compounds with antimicrobial activity, are emerging sources of natural extracts incorporated into packaging films for shelf-life extension as well as functional ingredients in salad dressings and probiotic formulations for gut health [39,151].

These examples demonstrate how tailored biotechnological strategies can transform specific agro-food wastes into functional ingredients with validated industrial applications, particularly in food technology, the formulation of health-promoting products, and the development of sustainable alternatives to synthetic additives. This reinforces the role of biowaste valorization in achieving nutritional and environmental goals.

5.3.5. Economical Snapshot

Fruit and vegetable by-products contain high-value compounds with established markets. For instance, citrus peels are rich in flavonoids such as hesperidin. Hesperidin, a flavonoid abundant in citrus waste, had a market value of approximately USD 101.3 million in 2021 and is expected to increase to around USD 161.4 million by 2028 [153]. These compounds are used as natural gelling agents and antioxidants in food and nutraceuticals (e.g., low-sugar jams and supplements), making citrus peels a source of premium-value products.

Banana peels: Global banana production (~121 Mt in 2021) generates tens of millions of tonnes of peel waste annually [154]. Banana peels are rich in catechins (epicatechin, gallocatechin, etc.) and other polyphenols with antioxidant activity. For example, the gallocatechin content in banana peel is approximately five times higher than in the pulp [154]. These catechins feed into the natural antioxidants market (functional beverages, supplements) worth several billion dollars. Although specific figures for banana peel catechins are scarce, they are chemically similar to compounds found in green tea and cocoa, and are valued in markets for sports supplements and phytonutrients.