Abstract

The valorization of food waste through bioconversion using black soldier fly larvae (BSFL, Hermetia illucens) represents a promising pathway for sustainable waste management. However, the efficiency and safety of this process when using low-quality food waste substrates remain insufficiently characterized. This study investigated the adaptive responses, nutrient conversion efficiency, and product safety of BSFL reared solely on food waste (moisture 78.4%, crude protein 42.98%, pH 3.62) under controlled conditions (28 °C, 55% RH). Larval growth followed a logistic model (R2 = 0.96), with an inflection point at 13.14 days and a maximum daily weight gain of 0.0153 g/larva. Crude protein content increased significantly to 64.21%, while crude fat peaked at 26.42% by day 6 before declining. Larvae accumulated essential amino acids and functional fatty acids effectively. Notably, BSFL demonstrated a strong ability to exclude arsenic and chromium, with over 90% of these heavy metals retained in the frass. The frass itself exhibited high organic matter content (up to 61.57%) and an alkaline pH, meeting general standards for organic fertilizers. These findings underscore the resilience of BSFL and its potential for safe, high-value biomass production from challenging food waste streams, contributing to advanced circular economy strategies.

1. Introduction

With accelerating global urbanization and shifting consumption patterns, food waste—a major component of urban organic refuse—has become a critical bottleneck for ecological sustainability [1]. According to United Nations Environment Programme statistics, approximately 931.1 million tons of food waste are generated globally each year, a staggering figure that underscores the dual challenges of resource loss and environmental degradation [2]. In China alone, municipal solid waste amounts to 117.141 million tons annually, of which food waste constitutes a substantial portion—between 23 and 45 million tons. This complex waste stream is composed of 38.2% fruit, 41.52% vegetables, 7.62% staple foods, 7.22% eggshells and bones, 2.52% shells and pits, and 2.32% meat by wet weight [3,4].

In many Asian countries, including Malaysia, food waste management continues to be constrained by multiple challenges such as limited funding, low public awareness, and technological gaps. Conventional methods like landfilling and incineration remain dominant, exacerbating serious environmental problems including soil and air pollution and posing long-term health risks due to the bioaccumulation of toxins in the food chain [5]. Although more sustainable pathways such as recycling and composting have been recognized for their potential, their widespread adoption remains limited due to these same constraints. Therefore, the development of efficient and safe bio-recovery technologies has become an urgent global issue.

In this context, the development of efficient and safe biological recovery technologies has become an urgent global priority. Black soldier fly larvae (BSFL, Hermetia illucens), a saprophagous insect recognized for its high resource conversion efficiency and environmental adaptability, have emerged in recent years as an innovative biorecycling technology for food waste valorization [6]. Unlike conventional disposal methods, BSFL-based bioconversion actively recovers nutrients from waste streams, transforming them into high-quality insect biomass rich in protein and lipids. What is particularly important is that this process also produces nutrient-rich insect manure. Insect manure is a mixture of larval excrement, molts, and leftover food; it can be used as high-quality organic fertilizer [7,8]. Research has shown that the manure of black soldier flies can improve soil health and fertility, providing a basis for their introduction into agricultural production [9]. For example, field experiments have shown that it can significantly increase the yield of ryegrass as well as various soil fertility indicators such as OM, P2O5, and K2O. Further research is needed to examine the effects of different conditions, application rates, and combinations with nitrogen fertilizers in order to verify its effectiveness as an organic fertilizer. It is also important to consider the residual effects of this substance within the context of a circular economy [10]. Therefore, the black soldier fly conversion system enables the dual conversion of “waste” into both “feed” and “fertilizer”, thus aligning with the principles of the circular economy [11].

Studies indicate that BSFL contain 40–48% crude protein and 25–40% crude fat, with a nutritional profile comparable to high-grade animal feed ingredients such as soybean meal and fish meal [12,13]. This robust nutritional profile underpins their unique potential for integrated waste management and resource circularity, as they can efficiently convert a wide variety of organic wastes, including agri-food by-products, into valuable biomass [14,15].

However, a comprehensive understanding of key BSFL adaptation mechanisms is still evolving. Specifically, how their growth dynamics, nutrient accumulation, and heavy metal distribution patterns respond to variable rearing substrates requires further elucidation. This knowledge gap persists because much current research is narrowly focused on isolated life stages or basic nutritional endpoints [16,17], leaving a significant gap in system-level, life-cycle analyses. This includes a lack of detailed information on developmental progression across all larval stages, shifts in specific amino acid and fatty acid profiles, mineral accumulation trends, and the transfer dynamics of heavy metals within the integrated “larva–frass” system [18]. Crucially, the ecological adaptation strategies and resource conversion efficiency of BSFL confronted with high-moisture, low-protein, and strongly acidic (pH ≈ 3.62) food waste—a common yet under-investigated scenario—remain largely unexplored.

The novelty of this study is primarily reflected in the following aspects: Firstly, it systematically investigates the adaptability and conversion efficiency of BSFL under the challenging conditions of high moisture, low protein, and strong acidity—a scenario characteristic of hard-to-treat food waste that has rarely been explored comprehensively in previous studies. Secondly, it provides a comprehensive life-cycle analysis covering growth kinetics, dynamic accumulation of conventional nutrients, amino acids, fatty acids, and minerals, as well as the physicochemical evolution of frass, thereby overcoming the limitations of earlier research that often focused on isolated stages or single parameters. Thirdly, for the first time, it systematically elucidates the element-specific migration and safety regulation mechanisms of multiple heavy metals (As, Pb, Hg, Cd, and Cr) within the “larvae–frass” system, clarifying the ability of BSFL to selectively exclude contaminants while producing safe biomass. This integrated research framework, which combines challenging substrate conditions with a holistic analysis of growth, nutrition, and safety, represents a significant advancement from fragmented descriptions toward a systematic mechanistic understanding in the field.

Therefore, this study systematically examines the adaptation and bioconversion characteristics of BSFL in such challenging, low-quality substrates, using food waste as the sole diet. Grounded in the hypothesis that BSFL can effectively restrict heavy metal uptake via selective absorption and growth dilution—without compromising larval growth—we aim to elucidate the underlying ecological adaptation mechanisms and product safety regulation strategies. Our findings are expected to provide a theoretical foundation and practical support for advancing insect-based bioconversion as an innovative and sustainable food waste recycling technology, contributing to safer and more efficient resource recovery systems.

2. Results

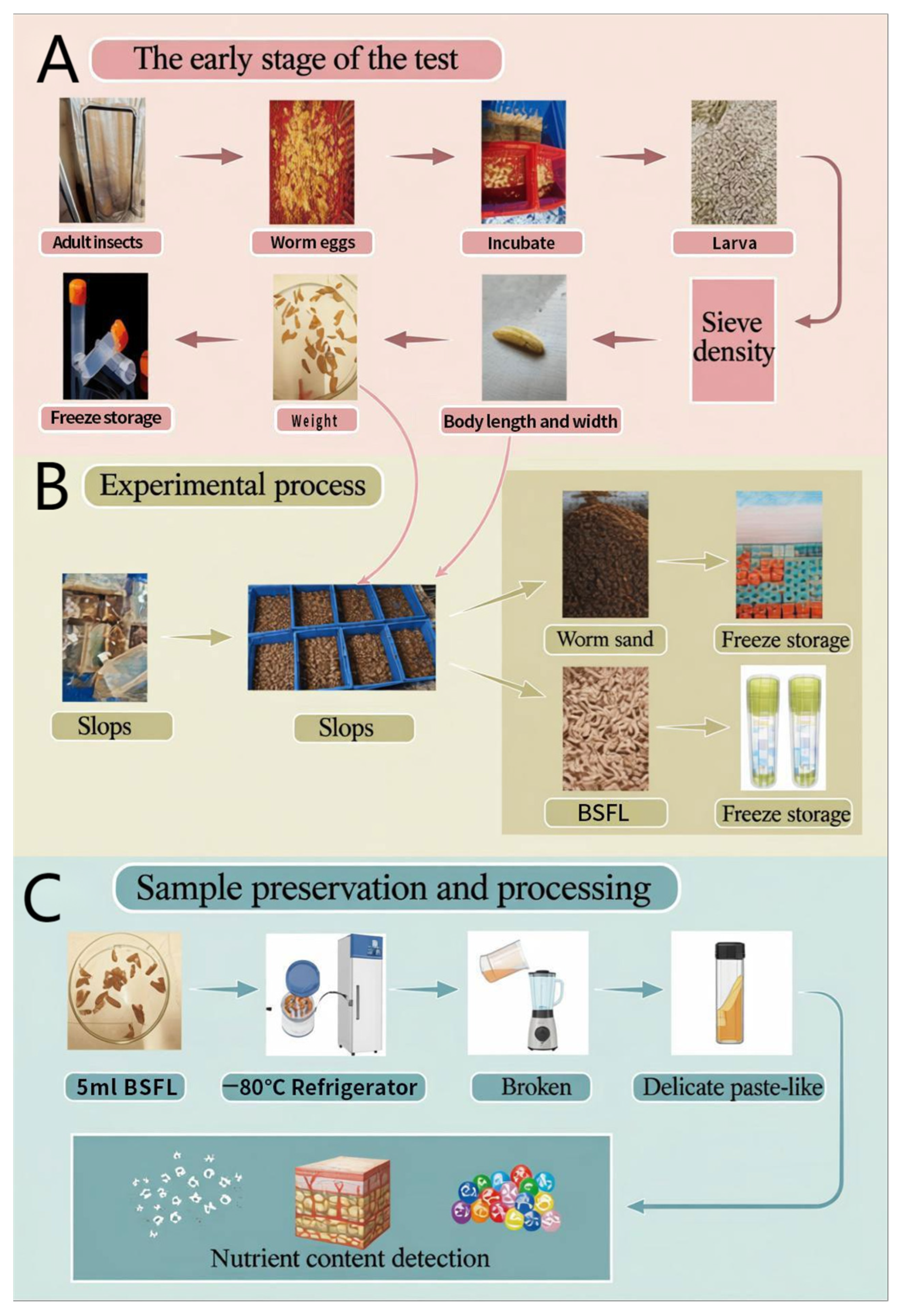

2.1. Adaptive Response of BSFL Growth Performance to Low-Quality Substrate

BSFL in all treatment groups demonstrated robust growth after consuming food waste slurry, with over 30% of individuals reaching the prepupal stage by day 15 (Figure 1). The weight dynamics of the larvae were fitted to a logistic growth model (Table 1), and the results indicated that weight gain followed a typical S-shaped curve (R2 = 0.96). The model parameters revealed that the maximum growth potential of the larvae was 0.215 g, the instantaneous relative growth rate was 0.285 d−1, and the growth inflection point occurred on the 13.14th day, corresponding to a weight of 0.108 g. The model further predicted that the maximum daily weight gain at this inflection point was 0.0153 g/larva (i.e., kA/4).

Figure 1.

Growth Status of BSFL. (A): 0 days old; (B): 3 days old; (C): 6 days old; (D): 9 days old; (E): 13 days old; (F): 15 days old.

Table 1.

Growth Curve Fitting Model Expressions and Parameters.

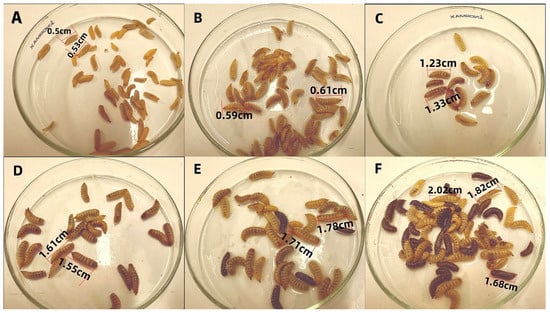

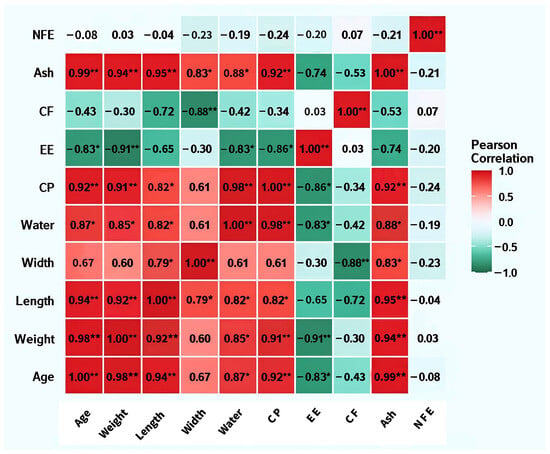

Correlation analysis (Figure 2) revealed significant correlations (p < 0.01) among all four variables: BSFL age, weight, body length, and body width. Age showed strong positive correlations with body weight (r = 0.979), body length (r = 0.938), and body width (r = 0.669). Body weight and body length exhibited a highly positive correlation (r = 0.918). A strong positive correlation also existed between body length and body width (r = 0.790). The detailed measurement data for body length, body width, and body weight are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Heatmap of correlations between body weight, body length, and body width in BSFL larvae at different ages.

2.2. Dynamic Accumulation of Conventional Nutrients in BSFL Fed Kitchen Waste Substrate

During growth on food waste substrate, BSFL demonstrated significant dynamic shifts in nutrient composition (Table 2). Body composition underwent transformations with increasing age (p < 0.05). Moisture content increased from 66.75% at hatch (0 days) to 75.90% by day 15. CP content accumulated progressively, rising from 52.59% initially to 64.21% at day 15. EE peaked at day 3 (26.03%) and day 6 (26.42%), then declined to 13.82% by day 15. CF was highest at hatch (13.25%) before declining and stabilizing. Ash content increased gradually from 5.42% to 8.44%. NFE fluctuated without a clear pattern.

Table 2.

Dynamic Regulation of Conventional Nutritional Components in BSFL Fed on Food Waste Substrate.

Correlation analysis (Figure 3) showed strong positive correlations (p < 0.01) between age and CP (r = 0.92), Ash (r = 0.99), and moisture (r = 0.87), and a significant negative correlation with EE (r = −0.83). Body weight and body length exhibited significant positive correlations with CP and Ash, and negative correlations with EE. CP and moisture showed a strong synergistic trend (r = 0.98), whereas CP and EE demonstrated a negative correlation (r = −0.86). Ash maintained significant positive correlations with nearly all nutritional parameters except NFE.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of correlation matrix between body length, body weight, body width, and nutritional status of BSFLs at different ages. Note: **: p < 0.01; *: p < 0.05; CP: Crude protein; EE: Crude fat; CF: Crude fiber; Ash: Crude ash; NFE: Nitrogen-free extract.

2.3. Amino Acid Composition and Content of BSFL at Different Ages on Swill Substrate

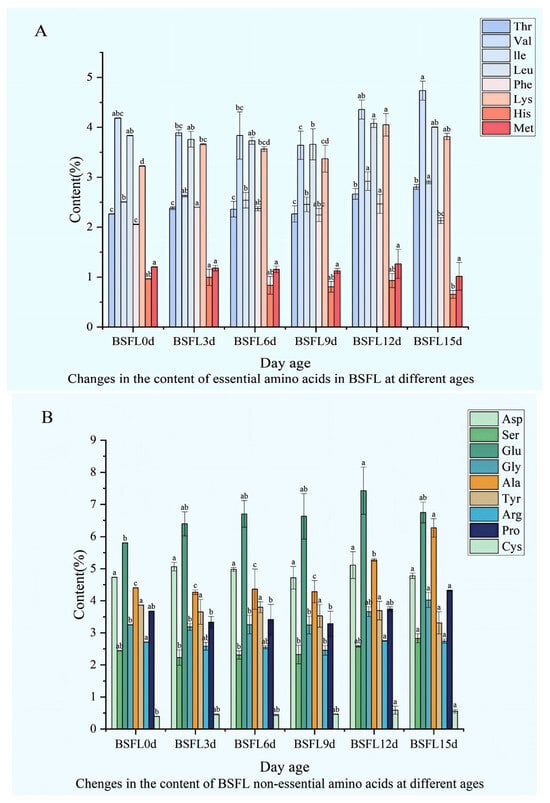

Significant differences emerge in the amino acid composition and content of BSFL raised on swill substrate across different developmental ages. Essential amino acid levels display distinct patterns (Figure 4A): Thr concentration varies throughout growth, peaking relatively high at 15 days post-incubation (DPI) before further shifts; Val undergoes overall fluctuations, with a particularly pronounced change at 15 DPI; Leu levels shift with age, showing a marked increase at 12 days; Phe exhibits significant age-related differences, reaching a high point at 12 days; Lys follows a complex trajectory, characterized by notable fluctuations at 9 and 12 DPI; Met varies across growth stages; His stands out significantly at 12 days compared to other ages, while consistently maintaining the lowest level among all essential amino acids.

Figure 4.

Dynamic changes in the amino acid composition of BSFL at different ages. (A) Essential amino acids; (B) Non-essential amino acids. Note: Thr: Threonine; Val: Valine; Leu: Leucine; Phe: Phenylalanine; Lys: Lysine; Met: Methionine; His: Histidine. Asp: Aspartic acid; Ser: Serine; Glu: Glutamic acid; Gly: Glycine; Ala: Alanine; Tyr: Tyrosine; Arg: Arginine; Pro: Proline; Cys: Cysteine. The lowercase letters (a, b, c) denote significant differences among groups; bars sharing the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05).

Among non-essential amino acids, distinct patterns also unfold (Figure 4B): Asp shows substantial variation across ages, with significant shifts occurring at 3 and 12 days old; Ser concentration fluctuates during development, differing markedly at various time points; Glu displays overall variation, achieving a higher concentration at 12 days old; Gly levels change with age; Ala reveals pronounced differences across developmental stages; Tyr fluctuates throughout BSFL growth; Arg exhibits both increases and decreases at different periods; Pro becomes especially prominent at 12 days old; Cys concentrations remain relatively low, fluctuating to some extent across the ages studied.

2.4. Changes in Fatty Acid Composition of BSFL at Different Stages Under Swill Substrate

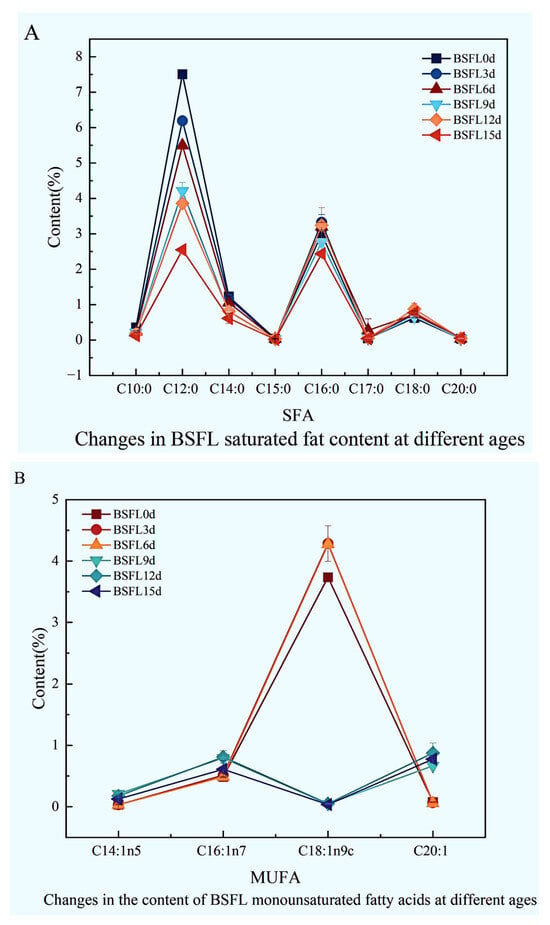

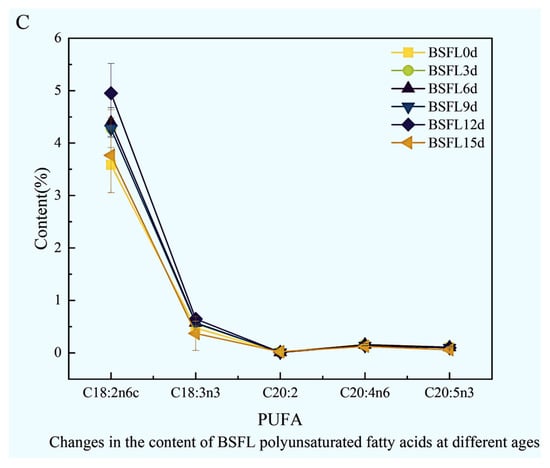

The fatty acid composition within BSFL undergoes striking dynamic shifts across different developmental ages (Figure 5). Results clearly demonstrate that saturated fatty acids (Figure 5A), monounsaturated fatty acids (Figure 5B), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (Figure 5C) all exhibit pronounced, significant fluctuations as the larvae mature, reflecting the intricate lipid metabolic characteristics inherent in larval morphogenesis and nutrient accumulation.

Figure 5.

Dynamic changes in the fatty acid composition of BSFL at different ages. (A): Saturated fatty acids (SFA); (B): Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA); (C): Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA).

Examining the saturated fatty acid profile (Figure 5A), key components included C10:0, C12:0, C14:0, C16:0, and C18:0. Notably, the medium-chain fatty acid C12:0 consistently dominated throughout all growth stages, its content substantially exceeding other saturated fatty acids. While most saturated fatty acids fluctuated with age, long-chain saturated fatty acids like C16:0 and C18:0 displayed relatively stable accumulation trends during later development.

Changes in monounsaturated fatty acids proved particularly dramatic (Figure 5B). C14:1n5 levels remained relatively stable and consistently low across developmental stages. C16:1n7 sharply peaked at BSFL12d. The predominant monounsaturated fatty acid, C18:1n9c, reached its highest concentration at BSFL3d before steadily declining to its nadir at BSFL15d. C20:1 levels generally remained low, showing only a slight elevation at BSFL12d followed by minor fluctuations without significant variation.

Within the polyunsaturated fatty acid spectrum (Figure 5C), C18:2n6 and C18:3n3 emerged as the dominant components. Overall, total PUFA content displayed relatively stable changes across different developmental stages. However, specific long-chain PUFAs, such as C20:4n6, manifested pronounced fluctuations during distinct growth phases, strongly suggesting their metabolism may be under precise developmental regulation.

2.5. Mineral Element Accumulation in BSFL at Different Ages

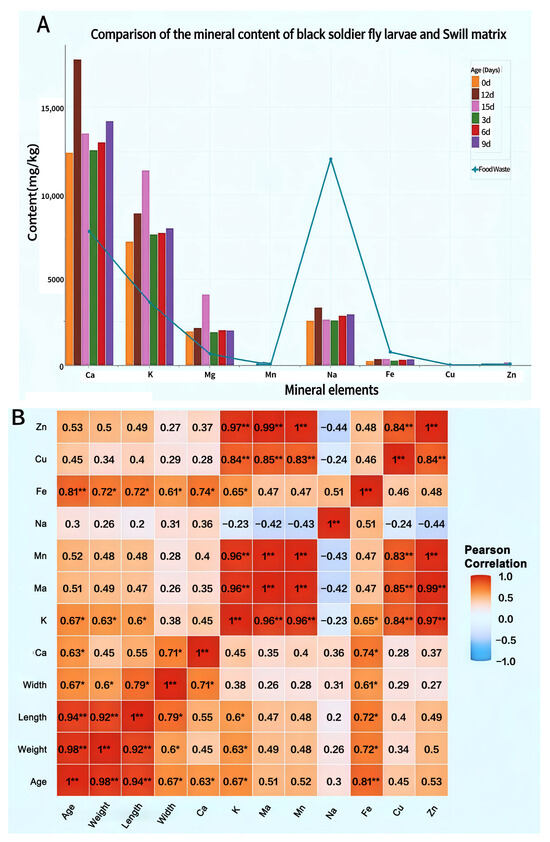

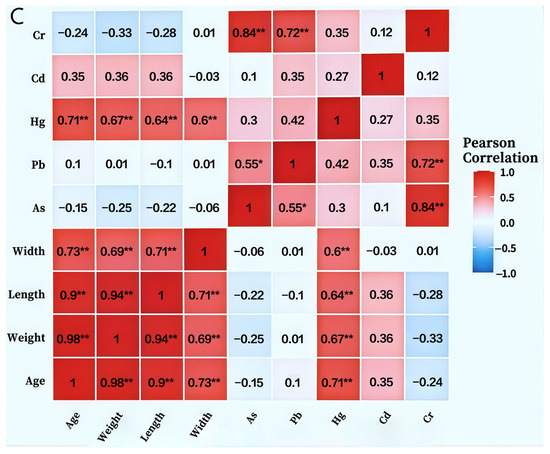

Stark differences emerge in mineral element content between BSFL and their food waste substrates. Research consistently demonstrates significantly higher concentrations of Fe, Cu, and Zn within the substrates compared to BSFL bodies (Figure 6A). Direct comparisons reveal that BSFL display pronounced bioaccumulation of multiple mineral elements from this waste. Crucially, larval calcium content maintained peak levels throughout development, substantially exceeding substrate concentrations and indicating a remarkable calcium enrichment capability. Concurrently, levels of K, Mg, Na, and Fe progressively increased as larvae matured. In contrast, Mn, Cu, and Zn exhibited the lowest accumulation rates.

Figure 6.

Mineral Element Accumulation in BSFL Insects at Different Ages. (A): Mineral Element Dynamics in BSFLs Developed on food waste Substrate; (B): Heatmap of correlation matrix between body length, body weight, body width of BSFL at different ages and mineral content in BSFL bodies. Note: Ca: Calcium; K: Potassium; Mg: Magnesium; Na: Sodium; Fe: Iron; Mn: Manganese; Cu: Copper; Zn: Zinc. Pearson correlation analysis among larval age, morphological traits (weight, length, width), and mineral element content. Significance levels are denoted by asterisks: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Correlation analysis between mineral content and growth indicators (Figure 6B) further revealed a close relationship between mineral accumulation and larval development. Larval age exhibited a strikingly robust positive correlation with iron content and a significant positive correlation with potassium and calcium content, indicating that the larvae’s ability to accumulate these essential minerals markedly increases as they mature. Additionally, larval body weight and body length demonstrated significant positive correlations with multiple minerals (e.g., K, Fe), highlighting synchronized processes of growth and mineral accumulation. Among mineral elements, K, Mn, and Zn demonstrated strong synergistic accumulation trends, with pairwise correlations reaching extremely significant levels.

2.6. Analysis of Fecal Matter Composition from BSFL at Different Ages in Swill Substrate

Analysis of BSFL frass composition across different growth stages in swill substrate revealed significant shifts in physicochemical properties with larval development (Table 3). Organic matter content remained consistently high, ranging from 58.55% to 62.51%, with no significant differences observed among age groups (p > 0.05). Total nutrient content also exhibited stability, varying between 9.55% and 11.89%, showing no significant variation between groups. Total nitrogen content maintained a stable range of 6.80% to 7.96%, again revealing no significant differences between groups. Total phosphorus content, however, exhibited a decreasing trend as larvae aged, declining significantly from 3.07% at 3 days old to 1.73% at 15 days old. Total potassium content fluctuated between 0.50% and 1.15%, without significant differences emerging among the groups. Fecal moisture content spanned a range from 55.55% to 70.08%, reaching its lowest point in the 6-day-old group. Fecal pH values ranged from 7.75 to 8.30, indicating an overall weak alkalinity; nonetheless, no significant differences were noted between the different age groups.

Table 3.

Composition of BSFL Castings at Different Ages on food waste Substrate.

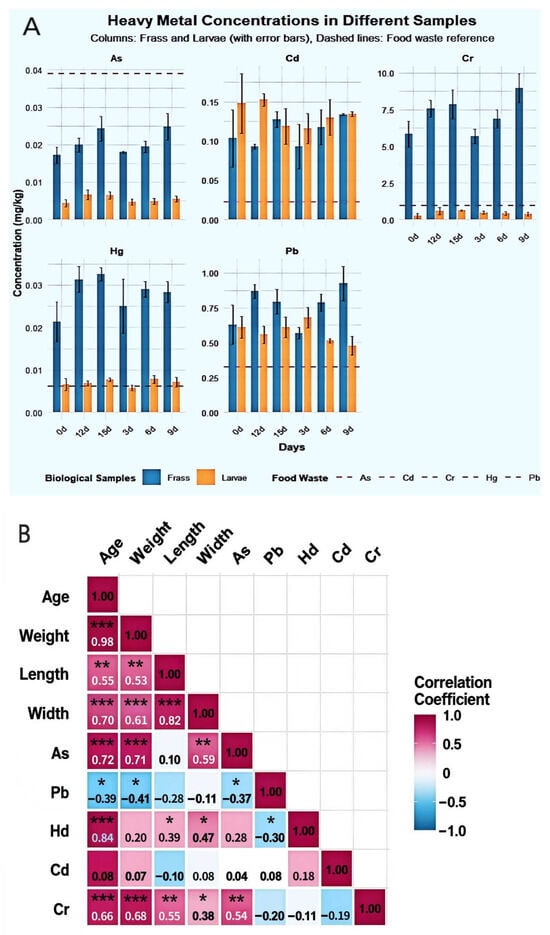

2.7. Heavy Metal Accumulation in Maggots and Maggot Sand

The migration and accumulation patterns of five heavy metals in the BSFL-maggot sand system across different samples are depicted in Figure 7A. Marked differences exist in the distribution of heavy metals between maggot bodies and maggot sand. As predominantly accumulated in the maggot sand (0.015–0.033 mg/kg), exhibiting extremely low concentrations within the maggot bodies (0.0015–0.0086 mg/kg). The bioconcentration factor (BCF) ranged from 0.04 to 0.22, indicating that BSFL vigorously excrete arsenic. Conversely, Pb accumulated significantly in the maggot bodies (0.38–0.87 mg/kg), with a BCF of 1.17–2.72. Feces revealed peak Pb content (1.17 mg/kg) at the BSFL6d stage. Mercury (Hg) peaked in the maggot body at BSFL6d (0.0105 mg/kg), representing a 150% increase from initial levels, while fecal matter consistently contained higher concentrations than the maggot body (0.012–0.035 mg/kg). Cd exhibited pronounced fluctuations within the larvae, reaching its highest accumulation at BSFL6d (BCF = 9.62). Cadmium levels in feces paralleled those in the larvae, suggesting an active absorption-excretion cycle. Cr was almost entirely retained in the feces (4.62–10.89 mg/kg), with extremely low or even negative concentrations in the larvae, demonstrating exceptionally low bioavailability. BSFL exhibit element-specific migration and distribution of heavy metals within the “larvae-fecal pellets” system, showing pronounced rejection of As and Cr while absorbing Cd and Pb to varying degrees.

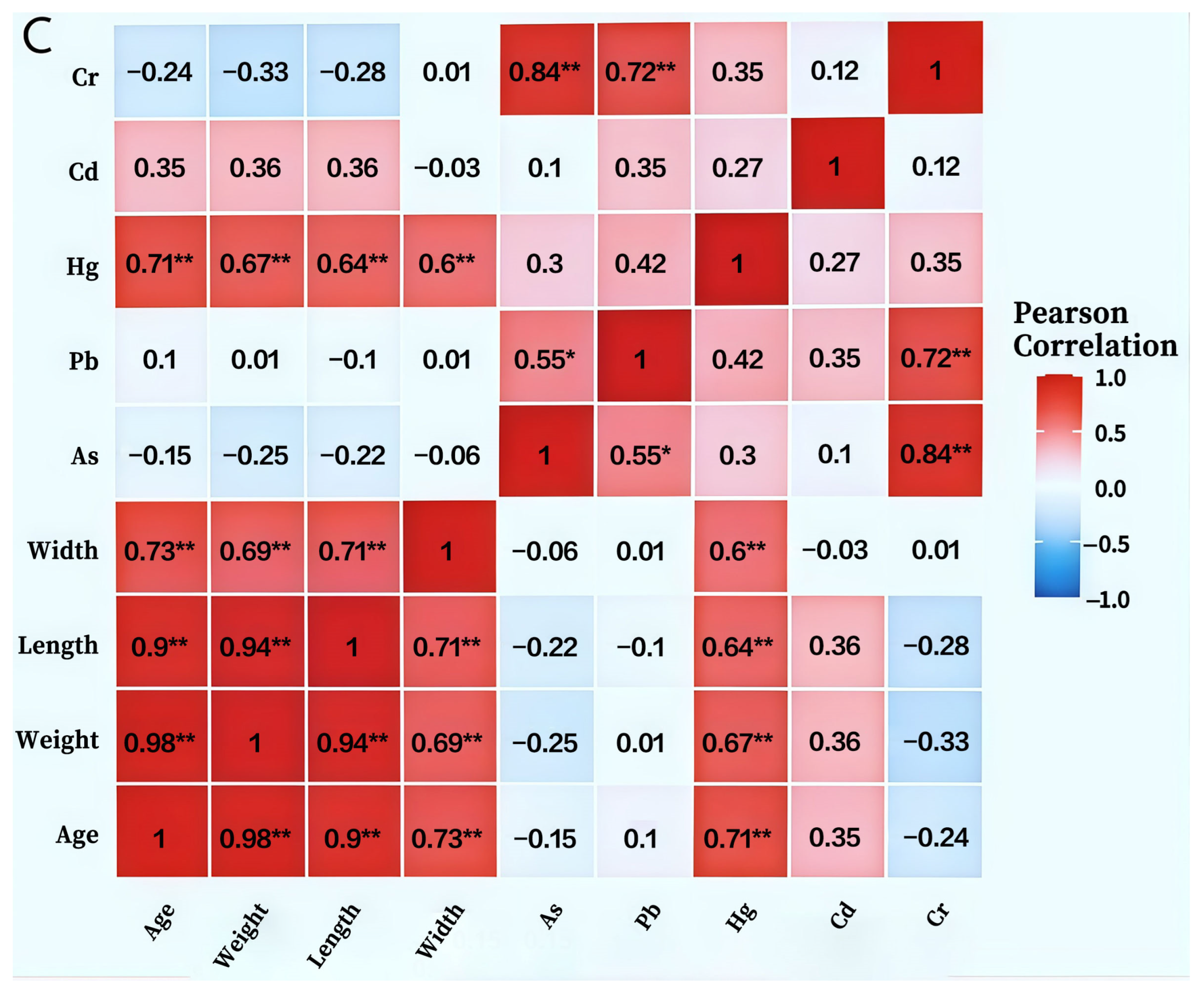

Figure 7.

Heavy Metal Accumulation in BSFL and Frass under Food Waste Substrate (A):Study on the Distribution Dynamics of Heavy Metals in BSFL Feces and Insect Bodies Under food waste Substrate Conditions; (B): Heatmap of correlation matrix between body length, body weight, body width of BSFL at different ages and heavy metal content in BSFL; (C): Heatmap of correlation matrix between body length, body weight, body width of BSFL at different ages and heavy metals in BSFL faeces). Note: As: Arsenic; Pb: Lead; Hg: Mercury; Cd: Cadmium; Cr: Chromium. Statistical significance levels are indicated as: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Correlation analysis unveiled a complex network of relationships between BSFL growth parameters and heavy metal accumulation characteristics (Figure 7B). Age and body weight displayed a highly positive correlation (r = 0.98, p < 0.001), while body weight and body length were also strongly correlated (r = 0.98), indicating stable growth traits and reliable morphological indicators. As, Pb, Hg, Cd, and Cr exhibited strong positive correlations among themselves (r = 0.70–0.76), suggesting potential synergistic accumulation and shared absorption or storage pathways. Age, body weight, and body length were negatively correlated with all heavy metals (r = −0.55 to −0.76), signifying that heavy metal accumulation capacity per unit body weight diminishes with developmental progression, potentially due to growth dilution or enhanced excretion. Cd demonstrated the strongest correlation with Cr (r = 0.76), hinting at a possible specific interaction mechanism between the two.

Pearson correlation analysis revealed (Figure 7C) significant positive correlations (p < 0.01) between BSFL body length, body width, body weight, and age. Body weight showed the highest correlation with age (r = 0.98), followed by body length with body weight (r = 0.94). Among heavy metals, As and Pb showed a significant positive correlation (r = 0.55, p < 0.05), while As and Cr exhibited extremely significant positive correlations (r = 0.84), as did Pb and Cr (r = 0.72, p < 0.01). Notably, Hg showed highly significant positive correlations with all larval growth indices (age, weight, body length, body width) (r = 0.60–0.71, p < 0.01). In contrast, Cd showed no significant correlations with any of these indices. Furthermore, As exhibited negative correlations with all growth indices, though these relationships did not reach statistical significance.

3. Discussion

This study comprehensively investigated the growth adaptation mechanisms, nutrient conversion efficiency, and product safety of BSFL cultivated on food waste-based substrates. The findings reveal that BSFL exhibit remarkable adaptability to high-moisture, low-protein, and acidic environments, primarily through a growth pattern characterized by significant elongation. They achieve highly efficient nutrient conversion and selective inhibition of heavy metal accumulation while maintaining stable biomass production. These insights provide essential theoretical foundations and practical support for insect-based bioconversion technologies targeting food waste.

3.1. Nutritionally Deficient Substrates Elicit a Compensatory Growth Response in BSFL

The robust growth of BSFL on highly acidic, high-moisture food waste, as evidenced by a strong fit to the logistic growth model (R2 = 0.96), underscores their notable metabolic plasticity. The observed growth inflection point at 13.14 days occurred later than that reported for larvae reared on more nutrient-dense substrates such as dairy manure (10–12 days) [16]. This delay aligns with the established principle that BSFL growth kinetics are profoundly influenced by substrate nutrient density and physical properties [19], suggesting a trade-off between adaptability and maximum growth rate in suboptimal environments. From the perspective of waste recycling efficiency, BSFL are capable of completing their entire life cycle even in strongly acidic and high-humidity conditions, demonstrating considerable substrate adaptability and stable waste processing capability. This provides a reliable technical approach for the efficient biological conversion of low-value organic waste. Growth curve parameters, such as a maximum daily weight gain of 0.22 g per larva, further highlight the potential of this technology for large-scale waste treatment coupled with resource recovery.

Our findings revealed strong positive correlations (p < 0.01) among larval age, weight, length, and width, indicating that BSFL maintain developmental synchrony and morphological integration even under nutritional and physicochemical stress. This coordinated growth pattern, likely a key adaptive trait, ensures functional somatic development and is consistent with previous observations of BSFL efficiently processing diverse untreated organic wastes [20]. The rigorous larval standardization and density control implemented in this study likely contributed to the high population uniformity and final body weights, which surpassed those reported in studies with less controlled conditions [21]. This supports the view that optimized rearing protocols are critical for maximizing BSFL performance in variable waste streams [22]. In terms of resource utilization value, the maintenance of high growth consistency and morphological uniformity on low-quality substrates facilitates subsequent large-scale harvesting and processing. This enhances the suitability of BSFL as a uniform protein source for feed, thereby improving its market acceptance.

The slightly lower maximum daily weight gain (0.22 g/larva) compared to studies using optimized feeds (e.g., 0.30 g/larva [23]) can be attributed to the inherent nutrient imbalances and high moisture content of the food waste substrate. The successful completion of the life cycle in a strongly acidic substrate (initial pH 3.62)—far outside the documented optimal range (pH 6–8) [24]—suggests the presence of sophisticated physiological buffering mechanisms. We posit that the BSFL gut microbiome plays a crucial role in this tolerance, potentially through the production of alkaline metabolites or the regulation of ion transport to maintain intestinal pH homeostasis [25,26]. Although Diener et al. [27] did not investigate such extreme pH conditions, their quantification of larval daily processing capacity for commercial garbage and human feces (3–5 kg/m2 and 6.5 kg/m2, respectively) demonstrated the broad adaptability of BSFL across diverse waste systems. This further corroborates the significant application potential of BSFL in the biological treatment of complex organic wastes, including those with strong acidity.

3.2. Dynamic Accumulation of Conventional Nutrients in BSFL Cultivated on Food Waste Substrate

The phased nutritional metabolism observed in BSFL reared on food waste highlights their capacity for dynamic resource allocation in response to substrate characteristics. The sustained increase in CP concurrent with a decline in EE after the initial growth phase suggests a metabolic shift toward protein conservation and structural growth as larvae approach pupation. The protein content of black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) observed on day 15 in this study—64.21% on a dry matter basis—was indeed higher than the ranges commonly reported in the literature (for example, 39.38% to 48.20%) [28]. This difference may stem from the larvae’s deep physiological adaptation to specific substrates, rather than merely from nutritional accumulation. Recent mechanistic studies have shown that inhibiting a specific amino acid transporter (HiNATt) in the BSFL excretion system can increase its total amino acid content by 77.3%, with some essential amino acids even doubling in amount [29]. This suggests that the high protein content observed in this experiment may be related to a similar internal nitrogen retention mechanism triggered by the feed, allowing for maximum protein synthesis under conditions of limited nutrition. This finding corroborates, at the mechanistic level, the research conducted by Liu and others, and supports the idea that BSFL generally adopts a conservative adaptive strategy of dynamically balancing protein and fat synthesis when facing different types of organic waste. This dynamic not only reflects the physiological adaptation of the larvae but also exemplifies the process of upgrading low-value food waste into high-value insect biomass. The increase in CP from an initial 52.59% to 64.21% demonstrates the ability of BSFL to effectively concentrate nitrogen, thereby facilitating efficient conversion and valorization of nitrogenous resources within the waste stream.

The notable rise in larval CP content (reaching 64.21%) despite the substrate’s moderate protein level (42.98%) points to efficient nitrogen retention and potential “selective assimilation,” a process likely mediated by gut microbiota [30]. In contrast to studies utilizing optimized feeds such as wheat bran or soybean meal—where CP levels typically plateau around 48–49% [28,31,32]—the higher CP observed here may reflect a “passive enrichment” effect. This phenomenon is likely driven by the relative scarcity of readily digestible carbohydrates and lipids in the food waste, supporting the view that BSFL prioritize protein synthesis under carbon-limited conditions [33]. This protein-enriching capability yields high-quality insect protein suitable for recycling applications, offering a potential substitute for conventional feed proteins like fishmeal and soybean meal, thereby enhancing the economic and environmental sustainability of the waste valorization process.

When reared on kitchen waste, the fat content of black soldier fly larvae exhibits a pattern of initial increase followed by a rapid decline. This is primarily due to the inherent metabolic changes that occur in the later stages of larval development in order to meet the energy demands required for metamorphosis, which lead to an accelerated breakdown of lipids [34]. In addition, the characteristics of the substrate (such as high moisture content and easy fermentability) may further affect the larvae’s ability to assimilate and metabolize lipids by altering the dynamics of the intestinal microbiota [35]. Therefore, the observed changes in lipid content are the result of the combined effects of the larval developmental process and the physiological adjustments mediated by the substrate [36]. The trend of fat accumulation observed in the larvae of this study differs from the findings reported by Zandi-Sohani et al. [37], and this is mainly attributed to the differences in substrate composition and harvesting timing. Although both studies utilized food waste, there were fundamental differences in their nutritional composition (such as the ratio of lipids to carbohydrates) [38]. Substrates rich in carbohydrates may promote fat accumulation more effectively through the “de novo synthesis” pathway, whereas the substrate used in this study may contain more indigestible fiber, which affected the energy storage mechanisms of the larvae [39]. Additionally, harvesting timing is crucial: in this study, the fat content peaked at 6 days of age, whereas the comparative study harvested the larvae on day 19, capturing different metabolic stages [40]. This highlights the high metabolic plasticity of black soldier fly larvae. Therefore, by precisely adjusting the substrate composition and harvesting timing, it is possible to selectively produce larvae with high fat content (suitable for biodiesel production or special feed applications) or optimize other outputs, thereby achieving the hierarchical and high-value utilization of resources.

Mašková et al. [17] observed a high fat content (34.02%) in BSFL reared on openly stored substrate at room temperature, suggesting that microbial degradation may convert complex organics into bioavailable lipid precursors. This highlights the critical influence of substrate pretreatment and storage on larval nutritional composition. Furthermore, Ribeiro et al. [41] reported that different plant-based substrates (e.g., pumpkin, red onion) significantly affect BSFL growth and nutrient accumulation, while substrates like apple and grape pomace may induce developmental delays due to anti-nutritional factors [42]. In the present study, the complex composition of food waste likely combines the promotive effects of microbial pre-degradation with the limiting effects of certain anti-nutritional factors [43], collectively shaping the final nutritional profile of the BSFL.

CF content increased synchronously with age and showed a highly significant positive correlation with CP. This reinforces the indispensable role of mineral elements as cofactors in numerous enzyme systems involved in protein synthesis and energy metabolism [44]. It also indicates that the continuous accumulation of minerals during larval growth may be linked to processes such as chitin synthesis, skeletal development, and enzymatic activation [22]. This accumulation pattern, characterized by “protein prioritization with dynamic fat allocation,” represents a core adaptive strategy [45,46]. Through precise stage-specific regulation of nutrient allocation priorities, BSFL achieve efficient conversion of low-quality substrates into high-quality insect biomass, fully demonstrating their considerable potential and metabolic plasticity as converters of organic waste [47].

NFE exhibited significant fluctuations across larval stages (2.24–8.29%) without a discernible trend. This variability may be attributed to the instability of carbohydrate fractions in the substrate and dynamic metabolic adjustments by the larvae. Previous studies indicate that substrates rich in non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) can result in higher larval crude fat content, suggesting BSFL possess the capacity to convert carbohydrates into lipids [48] The NFE variability observed here likely stems from the inherent compositional complexity and instability of food waste. Fermentable carbohydrates may undergo rapid microbial degradation during storage or rearing, causing dynamic shifts in availability and consequently affecting the stable metabolism and accumulation of NFE by the larvae [35].

A significant negative correlation between CP and EE further supports the existence of a nutrient allocation trade-off. This metabolic partitioning between protein and fat accumulation underscores the ability of BSFL to adapt their biosynthetic priorities in real time, a plasticity central to their efficiency in transforming heterogeneous, low-quality waste into nutrient-dense biomass.

While this study documents clear nutrient dynamics, the underlying molecular or enzymatic drivers—such as the activity of key lipases or proteases—remain uncharacterized. Further research integrating transcriptomic or metabolomic approaches is needed to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms governing these nutrient shifts. Additionally, the specific impact of substrate-derived microbiota on nutrient bioavailability warrants more detailed investigation.

3.3. Dynamic Accumulation Characteristics of Amino Acids and Fatty Acids

The sequential accumulation of amino acids and fatty acids in BSFL reared on low-quality substrates such as food waste elucidates the complex interplay between insect developmental physiology and the external nutritional environment. This process represents an active, metabolically regulated response to substrate properties rather than passive nutrient enrichment. From a resource valorization perspective, the stage-specific enrichment of amino acids and fatty acids demonstrates the capacity of BSFL to convert heterogeneous and labile organic components of food waste into stable, nutritionally balanced insect-derived oils and proteins. This significantly enhances the nutritional value and market competitiveness of BSFL products intended for feed or food applications.

BSFL amino acid metabolism follows a distinct “physiological demand-driven” pattern. EAAs, particularly lysine and leucine, exhibited marked accumulation near the growth inflection point (13 days post-hatching), aligning with the biological imperative to stockpile high-quality protein reserves for pupation [1]. This reproducible pattern across substrates with varying nutritional profiles underscores the robustness of intrinsic regulatory mechanisms governing nitrogen metabolism and EAA homeostasis in BSFL [49]. Even under the acidic, high-moisture stress conditions examined in this study, their EAA accumulation capacity remained stable, further validating BSFL’s robust nitrogen metabolism adaptability. Notably, arginine exhibited a peak accumulation during a specific developmental window (9–12 days post-laying) [50], likely linked to heightened demands for chitin synthesis and energy metabolism during the larval-to-prepupal transition [51,52,53]. Such dynamics inform the targeted application of BSFL based on developmental stage [54].

Metabolically, the initial phase (0–6 days) can be characterized as a “growth-priority phase,” during which approximately 80% of substrate nitrogen (as proteins and peptides) was directed toward de novo protein synthesis. This elevated larval crude protein content from 52.59% to 64.21%, with lysine and valine accumulating at rates of 0.08%/d and 0.06%/d (dry weight basis), respectively, meeting the demand for “structural amino acids” required for somatic tissue development [18]. The observed EAA pattern is consistent with findings from studies using high-fiber substrates like almond hulls [55] and Kenyan organic waste streams [15], indicating a conserved metabolic plasticity enabling phased EAA accumulation under diverse nutritional conditions. Compared to studies using putrefied sesbania leaves [56], the more pronounced arginine peak in this study may be attributable to differences in larval genetic background or substrate pretreatment. The consistent accumulation of EAAs suggests that BSFL can produce insect protein with a balanced amino acid profile even when reared on variable feedstocks, thereby ensuring product nutritional consistency and mitigating quality risks associated with raw material heterogeneity.

In contrast to the intrinsic robustness of amino acid metabolism, the fatty acid profile of BSFL acts as a responsive “metabolic mirror,” closely reflecting dietary fatty acid composition and larval carbon utilization strategy. The most prominent finding was the absolute dominance of C12:0, corroborating numerous global studies and reinforcing BSFL’s status as a premium natural source of this medium-chain fatty acid [57]. Compared to research using PUFA-rich substrates, the lower total and fluctuating long-chain PUFA content in this study directly reflects the inherently limited PUFA content of the food waste and indicates a constrained capacity for de novo long-chain PUFA synthesis in BSFL [58]. However, larvae demonstrated an ability to retain and convert dietary PUFA precursors [59].

From days 6 to 13, corresponding to an “energy reserve phase,” excess substrate carbon sources (24.64% nitrogen-free extract) were channeled into lipid synthesis, increasing EE content from 13.82% to a peak of 26.42%. This aligns with the metabolic model wherein “carbon sources are preferentially allocated to fat deposition during the mid-growth phase of BSFL” [27]. The fatty acid dynamics reflect refined carbon utilization. SFA, the medium-chain C12:0 consistently dominated across all stages. While most SFAs fluctuated with age, long-chain SFAs like C16:0 and C18:0 showed relative stabilization in later stages, consistent with late-larval energy reserve requirements [39]. We hypothesize that the high carbohydrate content in food waste may upregulate key lipogenic enzymes like acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthase (FAS), thereby driving SFA synthesis [7]. Among MUFAs, C18:1n9c tracked larval weight gain, fulfilling an energy storage role [60]. PUFAs, primarily C18:2n6c and C18:3n3, exhibited phased fluctuations, reflecting BSFL’s capacity to retain and convert dietary essential fatty acids [61,62], which are crucial for maintaining membrane integrity, regulating inflammation, and supporting neural development [34,63].

The high SFA accumulation trend aligns with findings that “BSFL lipid composition is significantly influenced by substrate type” [64]. However, the PUFA proportion in this study exceeded that reported for larvae reared on high-fat substrates [60], suggesting that carbohydrates in food waste may promote unsaturated fatty acid retention via lipid metabolic reprogramming [39]. The fatty acid composition, particularly the high accumulation of lauric acid, endows BSFL oil with unique functional properties, such as antibacterial and growth-promoting effects [65]. As a result, it can be used not only as a source of energy but also as a high-value feed additive or cosmetic ingredient, thereby expanding the range of products that can be derived from kitchen waste and increasing the economic benefits associated with this resource utilization [66].

In summary, BSFL employ a dual-track nutritional strategy during food waste bioconversion: they maintain strong metabolic autonomy and developmental programming in accumulating amino acids (especially EAAs) to meet core physiological needs, while their fatty acid profile exhibits greater plasticity, largely reflecting the dietary “carbon blueprint” to facilitate efficient energy assimilation and storage. A limitation of this study is the absence of substrate fatty acid characterization, which precludes a complete tracing of lipid conversion pathways. Future research should integrate detailed feed lipidomics to clarify the mechanisms of selective fatty acid retention and modification. Additionally, the contribution of the gut microbiota to amino acid metabolism warrants further investigation.

3.4. Mineral Element Accumulation Patterns and Bioaccumulation Effects

BSFL exhibit a mineral enrichment pattern characterized by the prioritized accumulation of macronutrients and the dynamic regulation of trace elements. This pattern is governed by the chemical speciation of elements in the substrate, the physicochemical conditions within the larval gut, and intrinsic homeostatic mechanisms.

Our findings align with those of Spranghers et al. [67], demonstrating efficient Ca accumulation, which supports structural functions such as chitin synthesis and cuticle formation. The higher Ca accumulation observed in the present study compared to the report by Oonincx et al. [48] may be attributed to the presence of highly bioavailable Ca sources (e.g., bone fragments and eggshells) in the food waste substrate. Similarly, the progressive uptake of K, Mg, and Na corroborates the work of Barragán-Fonseca et al. [68], underscoring their essential roles in osmoregulation and neuromuscular function. The efficient assimilation of these essential minerals enables BSFL to convert mineral fractions present in food waste (such as those from eggshells and bones) into bioavailable forms within their biomass. This process enhances the mineral nutritive value of BSFL as a feed ingredient, facilitating the effective recovery of mineral resources from waste streams.

In contrast, trace elements such as Cu and Zn were subject to selective restriction, exhibiting declining uptake in later developmental stages despite their high concentrations in the substrate. This pattern diverges from the sustained accumulation reported by Liu et al. [34]. under different conditions, suggesting the activation of active homeostatic mechanisms in BSFL. These may involve processes such as metallothionein chelation or enhanced excretory pathways [69,70,71]. The synergistic relationship among Mn, K, and Zn implies shared transport pathways, such as ZIP transporters, as also noted by Diener et al. [21]. The limited assimilation of specific trace elements like Cu and Zn indicates that BSFL possess a degree of self-purification capability during resource recovery. This helps prevent the excessive bioaccumulation of potentially harmful minerals, thereby contributing to the safety of BSFL-derived products for feed applications.

We attribute the differential dynamics of trace elements largely to the substrate’s acidity (initial pH 3.62), which significantly influences metal solubility and bioavailability. This observation is consistent with Nguyen et al. [72], who identified pH as a critical factor modulating mineral assimilation in BSFL. Under acidic conditions, BSFL appear to employ a strategy that balances the increased bioavailability of metals with stringent intracellular regulation [73], particularly during the metabolic shift toward prepupal development [74].

Fe accumulation remained limited (Bioconcentration Factor, BCF < 1), which is consistent with the findings of Diener et al. [75]. This limitation is likely due to Fe complexation with dietary fiber or its reduced solubility within the acidic intestinal environment. However, unlike the Fe plateau observed by Zhou et al. [76] in larvae reared on agricultural waste, the age-dependent increase in Fe content observed here may reflect the predominance of more bioavailable organic Fe species in food waste, as suggested by van der Fels-Klerx et al. [77].

In summary, this study reveals that BSFL employ element-specific and developmentally regulated strategies for mineral accumulation. These findings advance our understanding of insect-mediated resource conversion and support the optimized application of BSFL in the valorization of organic wastes.

3.5. Dynamic Evolution of Excrement Composition and Its Functional Coupling with Metabolic Activity in BSFL

The physicochemical properties of BSFL frass evolved dynamically throughout the growth cycle, reflecting continuous larval–substrate interactions and nutrient redistribution.

Our analysis revealed that organic matter content remained consistently high (58.55–62.51%) across all age groups, indicating stable organic conversion efficiency. This result aligns with the range reported by Lalander et al. [78], underscoring the capacity of BSFL to produce humic-stable outputs from diverse organic wastes. In contrast to the age-dependent decline observed by Zhou et al. [76] in agricultural waste, the stability in this study may be attributed to the balanced dynamics between continuous feeding and larval metabolic activity in a high-nutrient food waste system.

Notably, total phosphorus content decreased significantly with larval age, from 3.07% at 3 days to 1.73% at 15 days. This trend corresponds with the high phosphorus demand during rapid growth phases—particularly near the developmental inflection point (13–14 days)—supporting cuticle formation and energy metabolism, as also noted by Barragan-Fonseca et al. [68]. Unlike the downward trend in total phosphorus levels, the content of total nitrogen exhibited fluctuating changes during the growth period: it decreased from 7.66% at 3 days of age to 6.80% at 6 days of age, then rose to a peak of 7.96% at 9 days of age, and subsequently began to decline gradually. This fluctuation pattern of “decrease-increase-decrease” may reflect the dynamic adjustments in the nitrogen metabolism, assimilation efficiency, and excretion behavior of larvae at different stages of development. During the early stages of rapid growth (approximately 3–6 days), nitrogen is efficiently assimilated into larval tissue proteins; in fact, more than 50% of the substrate nitrogen is stored by the larvae [38], This may result in a temporary decrease in the nitrogen content of manure. The subsequent peak (after 9 days) may correspond to a period of intense feeding and excretion, accompanied by a temporary increase in the activity of the intestinal microbiota—as evidenced by a significant increase in the abundance of nitrogen-metabolizing genes [79]. This affects the transformation and retention of nitrogen. Studies have shown that such microbial activity can cause significant changes in the total nitrogen content within insect fecal residues. The decrease observed during the later stages of development (12–15 days) may be related to the larvae preparing for the pupal stage, as their feeding activity slows down and their metabolic processes shift, resulting in a reduction in the total amount of nitrogen obtained from and excreted by the larvae [80]. These fluctuations indicate that the cycling of nitrogen within the larva-substrate system is not linear, but is rather subject to complex regulatory mechanisms influenced by the physiological state of the larvae and the restructuring of the microbial community.

The frass maintained a weakly alkaline pH (7.75–8.30) throughout the experiment, contrasting sharply with the acidic initial substrate. This alkaline shift may inhibit pathogens, consistent with the findings of Khaoula et al. [81] on frass antibacterial properties, though it could also affect nutrient availability. The observed pH increase with larval age deviates from the typical acidification caused by metabolic organic acids, a divergence that warrants further mechanistic study, as hinted in Diener et al. [27].

Moisture content varied substantially (55.55–70.08%), with the lowest value coinciding at 6 days with peak larval crude fat accumulation (26.42%), implying a link between lipid synthesis and water metabolism. This extends the nutrient–water balance concept discussed by Spranghers et al. [67]. Moreover, the stable total nutrient content (9.55–11.89%) confirms the suitability of frass as organic fertilizer, corroborating Oonincx et al. [48].

Overall, the compositional dynamics of frass are functionally coupled with larval metabolism and developmental transitions. The decline in frass phosphorus inversely correlates with larval accumulation, illustrating nutrient reallocation within the larva–frass system. The stable carbon-to-nitrogen ratio further reflects larval regulatory capacity in organic matter transformation, resonating with van Huis et al. [82] on insect resource allocation. Additionally, succession in larval digestive physiology and gut microbiota—emphasized by Silvaraju et al. [83] as critical in frass formation—likely drives these temporal changes. Substrate properties such as high moisture (78.4%), protein content (42.98%), and initial acidity (pH 3.62) also fundamentally shape frass characteristics. Finally, the metabolic shift around the prepupal transition (day 12) may further modulate frass composition, as indicated in related life-history studies [84].

In summary, this study elucidates the metabolic and environmental drivers behind frass composition dynamics, enhancing the understanding of nutrient flows in insect-based bioconversion systems. These insights establish a basis for optimizing frass valorization in agriculture while highlighting the need for further research on gut microbiome roles and nutrient bioavailability in different fertilizer applications.

3.6. Migration Patterns of Heavy Metals and Safety Risk Assessment

BSFL demonstrated a dynamic heavy metal management strategy characterized by “selective exclusion–phased accumulation–growth dilution” across As, Pb, Hg, Cd, and Cr, revealing element-specific and time-dependent regulatory behaviors.

Our findings align with the trends summarized in Wang et al. [85], showing strong Cd enrichment (BCF up to 9.62) but limited As accumulation (BCF 0.04–0.22), potentially due to Cd’s high bioavailability and affinity for metallothioneins [62]. Pb was also significantly retained in larvae (BCF 1.17–2.72), consistent with Wu et al. [71], suggesting possible cuticular adsorption or active transport mechanisms. In contrast, Hg peaked in larval bodies at day 6 but was consistently higher in frass—a distribution pattern diverging from that reported by Deng et al. [86] under copper stress, possibly due to differences in Hg speciation and organic matter complexation in our food waste substrate. The migration patterns of heavy metals within the “larva-worm sand” system are crucial for assessing the environmental risks and product safety associated with the biological conversion of kitchen waste. Studies have revealed that over 90% of arsenic and chromium are retained within the worm sand, indicating that the BSFL system possesses significant biological exclusion and immobilization effects on these pollutants. This effectively reduces the risk of these substances entering the food chain.

A key observation was the negative correlation between larval age/weight and body heavy metal concentrations (r = –0.55 to –0.76), strongly supporting a growth dilution effect. This phenomenon, also noted by Gao et al. [87], highlights BSFL’s capacity to reduce metal burden per unit biomass as they develop. Moreover, the positive inter-element correlations (r = 0.70–0.76), particularly between Cd and As (r = 0.837), suggest shared physiological pathways for uptake, transport, or detoxification, possibly involving metallothioneins (MTs) and multidrug resistance proteins (MDRs) [75]. The growth dilution effect indicates that by optimizing the harvesting strategy—such as harvesting when the biomass is at its maximum but before pupation—the heavy metal content per unit mass of the insect can be further reduced. This represents an important technological aspect for actively controlling the safety risks associated with the product during the recovery process.

From an application standpoint, our results corroborate the findings of Van der Fels-Klerx et al. [77] that BSFL maintain high viability in metal-contaminated substrates while effectively minimizing metal accumulation via prioritized excretion and biomass dilution. This underscores the importance of harvest timing—collecting larvae when biomass is maximal but before pupation—to reduce metal risks in derived products. Conversely, the predominant frass retention of As and Cr necessitates careful safety evaluation before its use as fertilizer, possibly requiring further treatment such as composting or chemical passivation.

In summary, BSF technology not only achieves the efficient conversion of organic waste but also serves as a tool for the biological separation of pollutants and the regulation of related risks during this conversion process. Through its selective absorption, excretion, and growth-dilution mechanisms, it can effectively prevent the migration of heavy metals into the high-value proteins in the insects. At the same time, it allows certain pollutants to accumulate in the insect waste, facilitating their centralized treatment or safe disposal. This technology truly realizes the sustainable goal of ‘waste management—resource recovery—risk control’ in one integrated approach.

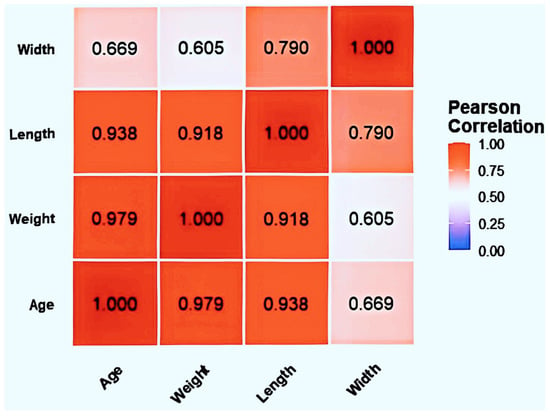

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Materials

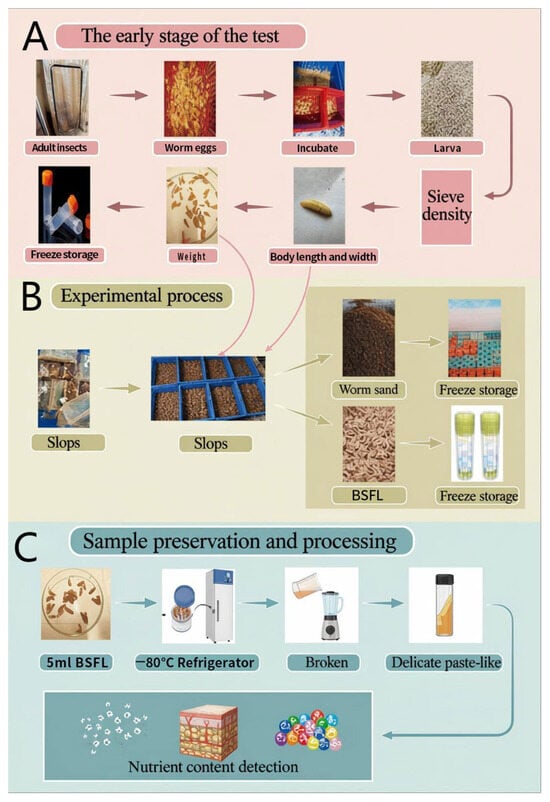

4.1.1. Preparation of BSFL

The experimental organisms were black soldier fly larvae (BSFL, Hermetia illucens). Eggs and newly hatched larvae were sourced from a colony maintained at the Institute of Livestock and Poultry Environmental Control, Yunnan Academy of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Sciences. This population had been reared to the eleventh generation using the same food waste substrate employed in this experiment (provided by Beijing Enterprises Group and pretreated via three-phase separation). Over three consecutive generations (8th–10th), the coefficient of variation for larval body weight and length at 5 days post-hatching remained below 5%, confirming a stable genetic background and consistent growth performance, and ensuring inherent larval adaptability to the experimental substrate [88].

BSFL preparation followed standardized rearing protocols to ensure uniformity and reliability of test organisms. On the morning of the experiment, fresh eggs were collected from the breeding facility. After precise weighing, the eggs were placed on mesh screens inside an incubation chamber set at 30 °C and 80% relative humidity—conditions optimized through preliminary tests and literature review to provide an ideal microenvironment for egg development [89].

After 24 h, feeding boxes containing 2 kg of a specialized starter diet for neonates (nutritional specifications: moisture ≤ 10%, crude protein ≥ 22.0%, crude fat ≥ 14.0%, crude fiber ≤ 6.0%, ash ≤ 8.0%, total phosphorus ≥ 0.35%) were introduced into the incubation chamber. Before actual feeding, we adjust the feed to an appropriate moisture content of 75–85% by adding an appropriate amount of water, and then provide it for the newly hatched larvae to consume. The mesh tray holding the eggs was suspended directly above the feeding tray to allow newly hatched larvae to migrate downward into the feed. This formulated diet met the nutritional requirements for early larval development and provided a stable initial nutrient supply.

After 48 h of complete hatching, boxes containing the neonates were transferred to a larval rearing room maintained at 28 °C and 60% relative humidity for the fattening phase.

Following 48 h of fattening, larvae were subjected to standardized size grading using a sieving protocol. First, a 12-mesh sieve was used to separate larvae from the residual substrate (frass), retaining larger individuals on the sieve. The remaining mixture was then passed through an 8-mesh sieve to remove smaller larvae that passed through. Larvae retained on the 8-mesh sieve constituted the final homogeneous experimental population. This rigorous screening procedure yielded physiologically consistent 5-day-old larvae (mean initial weight: 0.035 g; body length: 0.676 cm; body width: 0.182 cm).

After screening, the total biomass of the experimental larvae was recorded. A random sample of at least 300 individuals was selected for measurement of morphological parameters—body weight, length, and width. These data were used to standardize rearing density for subsequent group experiments, establishing a reproducible baseline for reliable and comparable intergroup results.

4.1.2. Preparation of Experimental Feed Substrate

The feed substrate utilized food waste collected from restaurants in Kunming City, supplied by Beijing Enterprises Group. Following three-phase separation to remove water and lipids, the residual solid fraction was homogenized into a slurry. Throughout the experimental period, the food waste was stored at −20 °C to preserve its chemical integrity and prevent spoilage, thereby ensuring consistency across all trials. We recognize that this storage condition may alter the original microbial composition of the substrate, which could, in turn, influence the bioconversion process. This factor is acknowledged as a limitation of the current study design, and future work will aim to characterize and account for such microbial dynamics. To determine the baseline nutritional composition of the food waste substrate and establish a reference for subsequent analysis of nutrient conversion between the substrate and larvae, samples were prepared from the pretreated material. These samples were evenly distributed in trays and dried in a forced-air circulation oven (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 60 °C for three days until a constant weight was achieved. The dried material was then ground using a Scott high-speed universal grinder (Scott Systems (Qingdao) Co., Ltd., Qingdao, Shandong, China) to ensure sample homogeneity and to facilitate accurate nutritional composition analysis. The nutritional profile of the food waste is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Nutrient Content (%) in Food Waste Matrix (on a dry matter basis).

4.2. Experimental Design

4.2.1. Rearing and Management

This study employed a completely randomized design with eight treatment groups to evaluate the conversion efficiency of BSFL on food waste substrates and characterize their growth responses. The larval density of 200,000 individuals per square meter was determined as optimal for this study and maintained across all replicates to ensure consistent experimental conditions and comparability of results.

The rearing containers consisted of plastic boxes (32 cm × 24.5 cm × 13.7 cm). Prior to use, all boxes were disinfected by spraying interior and exterior surfaces with 75% ethanol to eliminate potential microbial contamination. They were then placed in a climate-controlled rearing room set at 28 °C and 55% relative humidity for environmental equilibration. Each box was supplied with 1 kg of food waste substrate, which served as the sole nutrient source. The substrate had been pretreated and previously analyzed for basic physicochemical properties—including moisture content and total organic matter—to establish a standardized growth medium.

Based on an average initial larval weight of 0.0065 g, together with the floor area of the box and the target density, 15,680 five-day-old larvae (mean body length: 0.676 cm; mean body width: 0.182 cm) were introduced into each container. The total biomass introduced was controlled to within ±5% of the target value. Larvae were fed using a batch-feeding strategy. Before each replenishment, visual inspection and weight loss measurements were used to confirm near-complete consumption of the previous feed (residual substrate ≤ 5%), thereby avoiding anaerobic conditions and nutrient competition due to excess accumulation. The larvae are harvested when 30% of them have entered the pre-pupal stage, which is characterized by a reduction in body length and a darkening of color. This physiological stage is chosen because it marks a critical transition in the larvae’s development—from active feeding to preparation for metamorphosis. The aim of this approach is to obtain samples containing near-optimal biomass, and this standard is based on the developmental stage rather than the number of days since hatching. All experimental groups reached this threshold on the 15th day, indicating that the overall rate of development was comparable across groups; however, the exact timing at which this stage was reached may have varied slightly depending on the substrate used. The primary criterion for harvesting is always the physiological stage (30% pre-pupal stage), rather than the fixed date of the 15th day. This endpoint was selected to align with BSFL developmental cycles and minimize variability from asynchronous maturation.

Throughout the trial, daily observations were conducted to record substrate degradation rates and larval behavioral patterns, such as motility and aggregation. Simultaneously, microenvironmental parameters inside the containers, including temperature, were monitored to provide reliable data for subsequent analysis linking larval growth performance to substrate conversion efficiency.

4.2.2. Sample Collection

The experiment was conducted over a 16-day period. To systematically monitor the growth dynamics of BSFL and nutrient changes within the food waste substrate, while accounting for larval growth rates and physiological metabolism, sampling was performed at 3-day intervals. Key time points included days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15, with day 12 representing the transition from the late larval to the prepupal stage, and day 15 corresponding to the prepupal stage—thus covering critical phases of the larval development cycle.

During each sampling event, healthy larvae from each age group were selected and gently rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove adherent frass, thereby preventing potential interference with subsequent nutrient analysis. After rinsing, the larvae were placed on sterile filter paper and air-dried at room temperature until surface moisture had evaporated. The drying time was standardized to minimize variation in fresh weight due to residual moisture. Larvae were then rapidly transferred into 5 mL sterile cryogenic vials and immediately flash-frozen at −80 °C. This protocol effectively suppresses enzymatic activity and limits degradation of labile nutrients such as proteins and fatty acids, ensuring that the nutritional profile of the samples accurately reflects their in vivo state at the time of collection.

Simultaneously, age-matched frass samples were collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C to enable precise assessment of nutrient and heavy metal content. For pretreatment, fresh larvae and frass samples from each age group were homogenized using sterilized blenders under consistent operating parameters (e.g., speed and duration) to obtain a uniform fine slurry. This thorough homogenization eliminates sampling bias due to particle heterogeneity and ensures reproducibility and reliability in subsequent analyses. Food waste samples were spread on trays and dried in forced-air ovens at 60 °C for three days until complete desiccation was achieved. The dried material was then pulverized using a Scott high-speed universal grinder (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the experimental procedure for rearing BSFL, collecting samples, and analyzing nutritional components. (A): Initial stage of the experiment; (B): Experimental procedure; (C): Sample preservation and processing.

4.3. Determination Indicators and Methods

In this study, the conventional nutritional components (such as crude protein and crude fat), amino acids, fatty acids, mineral elements, and heavy metal contents of both the BSFL and their Frass were measured and reported on a dry matter basis in order to eliminate the influence of variations in moisture content and facilitate comparison. The basic composition of the feed (food waste) was also reported on a dry matter basis. The ‘Moisture’ content listed separately in the tables is based on the fresh weight and is hereby noted for clarification.

- (1)

- Develop a multifaceted assessment framework for the fundamental physicochemical properties of swill and BSFL, as detailed in Table 5:

Table 5. Fundamental Physicochemical Properties of Kitchen Wastewater and BSFL Insects.

Table 5. Fundamental Physicochemical Properties of Kitchen Wastewater and BSFL Insects.

- (2)

- Construct a comprehensive mineral testing system encompassing “macronutrients—micronutrients—heavy metal contaminants,” merging nutritional assessment with safety risk analysis (Table 6):

Table 6. Full Spectrum Mineral Testing for Constant Elements—Trace Elements—Heavy Metal Contaminants.

Table 6. Full Spectrum Mineral Testing for Constant Elements—Trace Elements—Heavy Metal Contaminants.

- (3)

- To unlock the application potential of insect feces (insect sand) as organic fertilizer, establish an integrated testing system covering “fertilizer quality—moisture characteristics—safety risks—ion content” (Table 7):

Table 7. Integrated Testing System for Fertilizer Quality—Moisture Characteristics—Safety Risks—Ion Content.

Table 7. Integrated Testing System for Fertilizer Quality—Moisture Characteristics—Safety Risks—Ion Content.

4.4. Data Analysis

All data are presented as means ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD) and subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) via SPSS 23.0 software. Where significant intergroup differences emerged, Duncan’s multiple range test was employed for post-hoc comparisons. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05, with p < 0.01 denoting high significance. Graphical and tabular representations were generated using Origin 8.5 software.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms the potential of BSFL to effectively convert high-moisture, acidic food waste into high-value biomass and organic fertilizer under controlled conditions. The larvae exhibited robust growth, efficient nutrient conversion (crude protein up to 64.21%), and a strong selective exclusion of heavy metals such as As and Cr into the frass. The resulting frass, rich in organic matter (58.55–62.51%) and alkaline in pH, demonstrates promising characteristics for use as an organic fertilizer. While the controlled experimental setup ensures scientific rigor and mechanistic clarity, further research is needed to adapt these findings to large-scale, real-world food waste systems with variable composition and operational conditions. Based on the observed nutrient and heavy metal dynamics, harvesting larvae between 6–9 days post-hatching is recommended to balance biomass yield and product safety. A systematic safety assessment framework for the frass is also advised before agricultural application. These findings support the integration of BSFL-based bioconversion into circular economy strategies for challenging organic waste streams.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/recycling11010008/s1: Table S1: Growth changes in the body weight, body length, and body width of black soldier fly larvae.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and B.Z.; methodology, J.S. and S.D.; software, Z.Z.; validation, H.S., J.S. and S.H.; formal analysis, H.S., J.S. and S.H.; investigation, S.D.; resources, B.Z. and R.Y.; data curation, B.Z., R.Y. and D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, B.Z. and D.W.; visualization, R.Y., S.H. and S.D.; supervision, D.W. and Z.Z.; project administration, Z.Z.; funding acquisition, D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Yunnan Science and Technology Talent and Platform Program, grant number 202505AT350004; the Major Science and Technology Special Plan Project of Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department, China, grant number 202302AE090009; the Scientific Research Fund Project of Yunnan Provincial Department of Education, grant number 2025Y0472; the Agricultural Basic Research Joint Project of Yunnan Province, grant number 202301BD070001-095; and the Scientific Research Foundation of Yunnan Agricultural University, grant number KY2022-53.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study have been included in the article and Supplementary Materials. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to all individuals who contributed to the sample collection process. We extend our special thanks to Jingyi Shi for her invaluable assistance and dedicated efforts throughout this study. We hereby confirm that all individuals mentioned in this section have provided their consent to be acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSFL | Black soldier fly larvae |

| CP | Crude protein |

| EE | Crude fat/Ether extract |

| CF | Crude fiber |

| Ash | Crude ash |

| NFE | Nitrogen-free extract |

| EAA | Essential amino acid |

| Thr | Threonine |

| Val | Valine |

| Leu | Leucine |

| Phe | Phenylalanine |

| Lys | Lysine |

| Met | Methionine |

| His | Histidine |

| NEAA | non-essential amino acids |

| Asp | Aspartic acid |

| Ser | Serine |

| Glu | Glutamic acid |

| Gly | Glycine |

| Ala | Alanine |

| Tyr | Tyrosine |

| Arg | Arginine |

| Pro | Proline |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acid |

| C10:0 | Decanoic acid |

| C12:0 | Lauric acid |

| C14:0 | Myristic acid |

| C16:0 | Palmitic acid |

| C18:0 | Stearic acid |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acid |

| C14:1n5 | Myristoleic acid |

| C16:1n7 | Palmitoleic acid |

| C18:1n9c | Oleic acid |

| C20:1 | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| C18:2n6 | Linoleic acid |

| C18:3n3 | α-Linolenic acid |

| C20:4n6 | Arachidonic acid |

| Ca | Calcium |

| K | Potassium |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| Na | Sodium |

| Fe | Iron |

| Mn | Manganese |

| Cu | Copper |

| Zn | Zinc |

| As | Arsenic |

| Pb | Lead |

| Hg | Mercury |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Cr | Chromium |

| AFS | Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy |

| GFAAS | Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| BCF | Bioconcentration factor |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| DPI | Days post-incubation |

| MTs | Metallothioneins |

| MDRs | Multidrug resistance proteins |

| NSC | Non-structural carbohydrates |

References

- Sahoo, A.; Dwivedi, A.; Madheshiya, P.; Kumar, U.; Sharma, R.K.; Tiwari, S. Insights into the Management of Food Waste in Developing Countries: With Special Reference to India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 31, 17887–17913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Waste Index Report 2024|UNEP—UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/food-waste-index-report-2024 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, F.; Li, X.; Zeng, G.; Yang, Q. Potential Impact of Salinity on Methane Production from Food Waste Anaerobic Digestion. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.K.; Peng, N.T.; Amrul, N.F.; Basri, N.E.A.; Jalil, N.A.A.; Azman, N.A. Potential Application of Black Soldier Fly Larva Bins in Treating Food Waste. Insects 2023, 14, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedalmoosavi, M.M.; Mielenz, M.; Veldkamp, T.; Daş, G.; Metges, C.C. Growth Efficiency, Intestinal Biology, and Nutrient Utilization and Requirements of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae Compared to Monogastric Livestock Species: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, R.; He, S.; Dai, S.; Hu, Q.; Li, X.; Su, H.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, D. Swill and Pig Manure Substrates Differentially Affected Transcriptome and Metabolome of the Black Soldier Fly Larvae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwaniki, Z.; Neijat, M.; Kiarie, E. Egg Production and Quality Responses of Adding up to 7.5% Defatted Black Soldier Fly Larvae Meal in a Corn-Soybean Meal Diet Fed to Shaver White Leghorns from Wk 19 to 27 of Age. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 2829–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hori, A.; Kawasaki, T.; Hirayasu, H.; Iwase, S.-I.; Hashizume, A.; Ido, A.; Miura, C.; Miura, T.; et al. Evaluation of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae and Pre-Pupae Raised on Household Organic Waste, as Potential Ingredients for Poultry Feed. Animals 2019, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menino, R.; Felizes, F.; Castelo-Branco, M.A.; Fareleira, P.; Moreira, O.; Nunes, R.; Murta, D. Agricultural Value of Black Soldier Fly Larvae Frass as Organic Fertilizer on Ryegrass. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonaco, G.; Franco, A.; De Smet, J.; Scieuzo, C.; Salvia, R.; Falabella, P. Larval Frass of Hermetia illucens as Organic Fertilizer: Composition and Beneficial Effects on Different Crops. Insects 2024, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuel, M.; Sandrock, C.; Leiber, F.; Mathys, A.; Gold, M.; Zurbrüegg, C.; Gangnat, I.D.M.; Kreuzer, M.; Terranova, M. Black Soldier Fly Larvae Meal and Fat as a Replacement for Soybeans in Organic Broiler Diets: Effects on Performance, Body N Retention, Carcase and Meat Quality. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/44286/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Pornsuwan, R.; Pootthachaya, P.; Bunchalee, P.; Hanboonsong, Y.; Cherdthong, A.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Boonkum, W.; Wongtangtintharn, S. Evaluation of the Physical Characteristics and Chemical Properties of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae as a Potential Protein Source for Poultry Feed. Animals 2023, 13, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, W.; Elahi, U.; Zhang, H.; Ahmad, S.; Usman, M.; Yaqoob, M.U. Clean and Green Bioconversion—A Comprehensive Review on Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae for Converting Organic Wastes to Quality Products. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2025, 25, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumo, M.; Osuga, I.M.; Khamis, F.M.; Tanga, C.M.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Subramanian, S.; Ekesi, S.; van Huis, A.; Borgemeister, C. The Nutritive Value of Black Soldier Fly Larvae Reared on Common Organic Waste Streams in Kenya. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, H.M.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Lambert, B.D.; Kattes, D. Development of Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) Larvae Fed Dairy Manure. Environ. Entomol. 2008, 37, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovera, F.; Loponte, R.; Marono, S.; Piccolo, G.; Parisi, G.; Iaconisi, V.; Gasco, L.; Nizza, A. Use of Larvae Meal as Protein Source in Broiler Diet: Effect on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, and Carcass and Meat Traits. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, T.; Bosch, G. Insects: A Protein-Rich Feed Ingredient in Pig and Poultry Diets. Anim. Front. 2015, 5, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammsteiner, T.; Walter, A.; Bogataj, T.; Heussler, C.D.; Stres, B.; Steiner, F.M.; Schlick-Steiner, B.C.; Insam, H. Impact of Processed Food (Canteen and Oil Wastes) on the Development of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae and Their Gut Microbiome Functions. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 619112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tariq, M.R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Zheng, C.; Li, K.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, L. Dietary Influence on Growth, Physicochemical Stability, and Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Peptides in Black Soldier Fly Larvae. Insects 2024, 15, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedalmoosavi, M.M.; Mielenz, M.; Görs, S.; Wolf, P.; Daş, G.; Metges, C.C. Effects of Increasing Levels of Whole Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae in Broiler Rations on Acceptance, Nutrient and Energy Intakes and Utilization, and Growth Performance of Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]