Abstract

The operating temperature of lithium batteries directly affects their charge–discharge performance. This study is based on the LF50K prismatic power battery. The battery’s thermal model and the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) control equation were established. After completing the model verification, a thermal management system with a bionic leaf vein flow channel was designed. The study focused on investigating the effects of varied flow passage configurations, inlet–outlet flow channel angles, flow channel widths, flow rates, leaf vein angles, and inlet–outlet positions on the cooling effect of the lithium battery module. The results show that, as the inlet–outlet angle and width of the bionic leaf vein fluid flow channel increase, the battery cooling effect deteriorates; the increase in the angle and flow channel width has an adverse impact on battery heat dissipation. The significant reduction in the battery’s maximum temperature observed with an elevated fluid flow rate underscores the positive contribution of flow rate to the cooling process. The effect of the leaf vein angle on the cooling of lithium batteries shows a fluctuating trend: when the angle rises from 30° to 45°, the battery’s peak temperature shows a slow upward tendency; conversely, with the angle further increasing from 45° to 80°, the maximum temperature shows a gradual downward tendency. Specifically, at an angle of 45°, Battery No. 5 hits a maximum temperature of 306.58 K (around 33.43 °C), with the maximum temperature difference also reaching 6.38 K. After optimizing the structural parameters, when operating under the maximum ambient temperature conditions in 2024, the maximum temperature of the battery module decreased by 7 K, and the temperature difference decreased by 5.47 K, enabling the battery to achieve optimal operating efficiency. This study lays a foundation for a further optimization of the thermal management system for lithium-ion batteries in subsequent research.

1. Introduction

New energy vehicles have the characteristics of energy conservation, zero emissions, and environmental protection. The automotive industry has pushed forward the development of new energy vehicles in recent years, with these models increasingly replacing fuel-powered alternatives. Lithium power batteries are widely used due to their low self-discharge rate, high specific energy, minimal self-discharge, and long cycle life [1]. However, lithium battery operating efficiency is greatly affected by the operating and environment temperature. Studies have shown that the optimal operating temperature range for lithium batteries is 20 °C~45 °C [2], and the temperature difference inside the battery module shall be constrained to a maximum of 5 °C [3,4]. When the lithium battery pack is operating under low-temperature conditions, its chemical reaction activity decreases, which slows down the charge transfer rate. This leads to a reduction in the battery capacity and charge–discharge rate, thereby causing a problem of decreased driving range for electric vehicles [5]. Under high-temperature operating conditions, the rate of chemical reactions within the battery is accelerated, which in turn leads to a rapid increase in the battery’s internal temperature. Under severe conditions, electric vehicles are susceptible to thermal runaway, potentially triggering severe consequences such as fires and explosions [6,7,8].

To enhance the efficiency and safety of lithium batteries, a large number of experts and scholars have conducted research on the thermal management problem of lithium power batteries in recent years. At present, the main heat dissipation methods include air cooling, liquid cooling, phase-change cooling, and combined heat dissipation [9,10]. Natural air cooling is inefficient, partly due to air’s low thermal conductivity. Forced air cooling, by contrast, has complex structures and high costs, restricting its broad use in heat dissipation. Phase-change cooling is currently under investigation. Due to the poor thermal conductivity and high cost of phase-change materials, there is currently no separate application of pure phase-change cooling solutions in lithium battery cooling systems on the market; liquid-cooled heat dissipation has a high research value owing to the excellent heat conductivity of the coolant, which produces a good heat dissipation effect on power batteries [11].

The common structures of liquid flow channels include serpentine channels and direct flow channels. Direct flow channels, with parallel or straight layouts, are widely used for low flow resistance. Luo et al. [12] integrated conventional parallel liquid flow channels with serpentine channels to construct a parallel–serpentine channel configuration. They then investigated how variations in channel structure and flow rate parameters influence the heat dissipation efficiency of batteries. Their findings indicated that, while the parallel–serpentine channel design enhances battery heat dissipation to a certain degree, it concurrently leads to higher pressure drop losses within the system. Li et al. [13] developed a parallel direct flow cooling plate for a 12-cell prismatic LiFePO4 module. Under the condition that the cooling surface was arranged between batteries (Face A) and the single-inlet mass flow rate was 1.2 g/s, the peak temperature reached 302.5 K, with a corresponding temperature difference of 1.7 K. Luo et al. [14] took 18650 lithium-ion batteries as the research object and designed a direct flow cooling battery thermal management system with rod baffles (DFC-BTMS) suitable for electric vehicles (EVs). They found that at a 3C discharge rate, the maximum average surface temperature of the battery pack reaches 24.789 °C, with a maximum temperature difference of 2.734 °C. For large pouch batteries, Fu et al. [15] proposed streamlined direct channels, cutting the pressure drop by 22.5% while keeping the module temperature difference within 2.3 K. Wu [16] found that increasing the direct channel numbers from 1 to 5 reduced the maximum temperature by 8.3% at 2C discharge but raised the pressure drop by 12.6%. Shen [17] studied direct flow microchannels, showing that a 0.8 mm channel width achieved an optimal heat transfer, with a pressure drop of 4.61 Pa.

Serpentine channels enhance heat transfer via extended paths and secondary flows. Venkateswarlu et al. [18] used serpentine microtubes with Cu-Al2O3/H2O hybrid nanofluids, lowering battery temperature by 4.12% and increasing the surface heat transfer rate by 5.86% compared to Al2O3/H2O nanofluids. Mubashir et al. [19] demonstrated that the adoption of dual-serpentine channels led to a 41% reduction in temperature difference, while this design simultaneously resulted in a 35% increase in pressure drop. Zhang et al. [20], on the other hand, integrated Y-shaped fins into serpentine channels; this modification not only restricted the maximum temperature to 44.2 °C but also achieved a 33.3% decrease in pressure drop. Jiang et al. [21] optimized serpentine parameters via a Bayesian algorithm, reducing the pumping power by 71%. Chen [22] studied secondary flow serpentine channels, where bend-generated secondary flow disrupted the thermal boundary layer, increasing the Nusselt number by 28.6%. Luo [23] carried out optimization on parallel serpentine channels for cylindrical modules, which led to a 5.2% reduction in maximum temperature and an 18.7% decrease in pressure drop.

The two types of traditional heat dissipation channels, namely straight channels and serpentine channels, are currently mainly used in electric vehicle batteries [9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,20,22,24], 3C devices [11], chemical energy storage devices [8,14,19], electric ships [18], and hybrid electric vehicles [22].

In addition to the above-mentioned traditional liquid cooling channels, many scholars have also designed other new structural types in current research. Qiao et al. [24] developed a bionic spider-web channel cold plate, improving temperature uniformity by 63.1% and reducing pressure drop by 33.7%. With a 1.896% Cu nanofluid (283 K, 0.05 m/s), the average temperature was 289.219 K. An [25] proposed honeycomb channels; orthogonal optimization showed that a 3 mm width and 6.8 mm hexagon side length achieved an optimal balance (302.5 K, 4.1 K difference at 0.1 m/s). Abdulqader et al. [26] added rhombus pin fins to convergent–divergent channels, increasing the Nusselt number by 95.5% and PEP to 1.68. Wang [27] designed tree-like fractal channels, controlling maximum temperature at 33.34 °C (3C discharge). Tang [28] studied sine function-based channels, where fluid oscillation enhanced heat transfer, reducing the temperature difference by 16%.

According to the current research situation, the new liquid flow channel can improve the heat dissipation effect of lithium battery modules to a certain extent and enhance battery charge–discharge efficiency. However, the mainstream new liquid cooling channels are mainly serpentine channels and direct flow channels. Studies have shown that plant leaf veins, as the most important transport system for water required for growth [29], can exchange heat under high-heat-flux-density conditions [30,31]. Inspired by natural leaf vein structures and based on the induction heating principle, Zhou [32] developed a non-contact open spray cooling experimental setup. Subsequent experiments led to the conclusion that leaf vein channels exhibit a significant heat transfer enhancement effect. Liu et al. designed a bionic leaf vein heat dissipation system for photovoltaic–thermal (PVT) collectors, and a numerical analysis showed that this system effectively enhances the heat dissipation of photovoltaic modules and improves their temperature uniformity [33]. To address the cooling requirement of lithium power batteries, this study focuses on prismatic lithium power battery modules and proposes a novel liquid-cooled heat dissipation scheme using a leaf vein channel cold plate. Therefore, this article takes a square lithium battery module as the research object and proposes a new liquid cooling heat dissipation scheme for the leaf vein channel cooling plate. The multiphysics coupling software COMSOL 6.2 Multiphysics is employed to conduct analytical investigations into the cooling behavior of lithium-ion batteries under varied liquid-cooled channel configurations and flow rate scenarios.

In the subsequent research of this paper, first, a mathematical model for lithium battery heat generation and a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model were established. A temperature test experiment was designed for the discharging characteristics of a prismatic lithium-ion single battery with the model LF50K. The COMSOL software was used to analyze this model, and the simulation results were contrasted against the experimental outcomes, thereby verifying the accuracy of the model. On the basis of the aforementioned model, three different liquid cooling channel structures—including a direct flow channel, a serpentine channel, and a leaf vein channel—were designed for the lithium battery module composed of five single batteries, and their heat dissipation behaviors were subjected to analysis, and the analytical findings indicated that, under the same other conditions, the leaf vein channel heat dissipation system exhibited a better heat dissipation effect. Therefore, in the following part, the influences of parameters related to the leaf vein channel on the cooling effect were analyzed, respectively, such as the inlet–outlet channel angles, the width of the liquid cooling channel, the included angle of the leaf vein flow channel, the liquid flow rate, and the inlet–outlet positions. Finally, the structure of the heat dissipation system was optimized for the battery working under high-temperature environmental conditions.

The research results of this paper provide certain ideas and references for the process of designing and optimizing the thermal management systems of power batteries in subsequent studies.

2. Mathematical Model

2.1. Control Equation

(1) Battery Thermal Model

Assuming that the single battery cell generates heat uniformly, according to the three-dimensional heat generation model of lithium batteries, the control equation of the battery thermal model can be established [34]:

Here, is the battery density, ; is the specific heat capacity of the battery, ; is the battery temperature, K; is the battery charge–discharge time, s; , , and are the thermal conductivity coefficients of the lithium battery in the , , and directions, ; is the volumetric heat generation rate of the lithium battery, .

In actual engineering applications, lithium-ion batteries’ heat production can be acquired through two approaches: experimental testing and theoretical calculation. The thermal generation of square lithium batteries during operating processes can be calculated using the following equation [3]:

where is the heat generation power per unit volume of lithium batteries, w/m3; is the discharge current of the battery, A; is the battery volume, m3; is the open-circuit voltage, V; is the battery potential, V; , where R represents the internal resistance of the battery; is the entropy coefficient; and is the reversible reaction heat component, where a value of 0.0514 V is generally adopted [35]. In this study, square lithium power batteries of model LF50K from a certain brand were selected as the research object. The battery has dimensions of 185 mm × 135 mm × 30 mm, with a nominal voltage of 3.2 V, a nominal capacity of 50 Ah, an internal resistance of 0.3 mΩ, a discharge cut-off voltage of 2.5 V, and a charge limiting voltage of 3.65 V.

(2) Computational Fluid Dynamics Model

The following assumptions are introduced to simplify the model and streamline the simulation analysis: the cooling plate is assumed to be uniform and isotropic, while the supporting structures at its connections are omitted; the coolant is an incompressible fluid; the external environmental temperature does not change with time; and the thermal characteristics of the battery, coolant, and cold plate materials are temperature-independent. The set of governing equations for the computational fluid dynamics simulation includes the continuity equation, momentum equation, and energy equation [12].

Coolant continuity equation:

Coolant momentum equation:

Coolant energy equation:

Energy conservation equation for liquid cooling plates [17]:

where is the density of the coolant, ; is the flow velocity of the coolant, ; is the static pressure of the coolant, pa; is the specific heat capacity of the coolant at constant pressure, ; is the temperature of the coolant, K; is the thermal conductivity of the coolant, ; is the density of the cooling plate, ; is the specific heat capacity of the cooling plate at constant pressure, ; is the temperature of the cooling plate, K; is the thermal conductivity of the cooling plate; and , , and are the thermal conduction coefficients of the cooling plate in the , , and directions, .

Coolant Reynolds number calculation:

where is the dynamic viscosity of the coolant. When the ambient temperature is 298.15 K, the dynamic viscosity of water is 0.839 × 10−3 pa·s; is the hydraulic diameter of the cooling channel, measured in meters.

2.2. Boundary Conditions and Material Thermal Property Parameters

In the above model, the battery material is lithium phosphate, the liquid cooling plate material is aluminum, and the coolant is water; the thermal properties of all material are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of materials.

This paper uses the multiphysics coupling software COMSOL MULTIPHYSICS to perform calculations and solve the above model. According to Equation (7), the coolant exhibits a Reynolds number that is less than 2300. During simulation calculations, the coolant is set to a laminar flow model, as referenced in [3,34], because natural convection takes place between the surface of the battery module, the cold plate, and the external environment (typically, the natural convection heat transfer coefficient ranges from 1 W/(m2·K)−1 to 10 W/(m2·K)−1). Therefore, the convective heat transfer coefficient employed in this simulation analysis is established at 5 W/(m2·K), with the external ambient temperature, initial coolant temperature, and initial cold plate temperature all assigned a value of 298.15 K; the inlet boundary of the coolant is set to velocity conditions, and the outlet is set to pressure conditions, with the default outlet pressure condition being zero [3,34].

2.3. Verification of Single-Cell Model

To ensure calculation accuracy, a grid independence test of the numerical prediction results is required. A free tetrahedral mesh is utilized to split the single battery model into grids. Generally, once the grid count in the model increases to a certain extent, the computational accuracy will not improve significantly. Therefore, six sets of grid models were generated according to different levels of fineness. The battery was set to discharge at a 3C rate, and a battery heat generation simulation analysis was conducted. The resulting data are shown in Table 2. It is observable that, as the number of grids rises from 289,034 to 10,531,096, the variation in the maximum battery temperature is confined to within 0.5%. For comprehensive considerations, the free tetrahedral mesh model of the third type is adopted for subsequent simulation and calculation.

Table 2.

Results of grid independence verification.

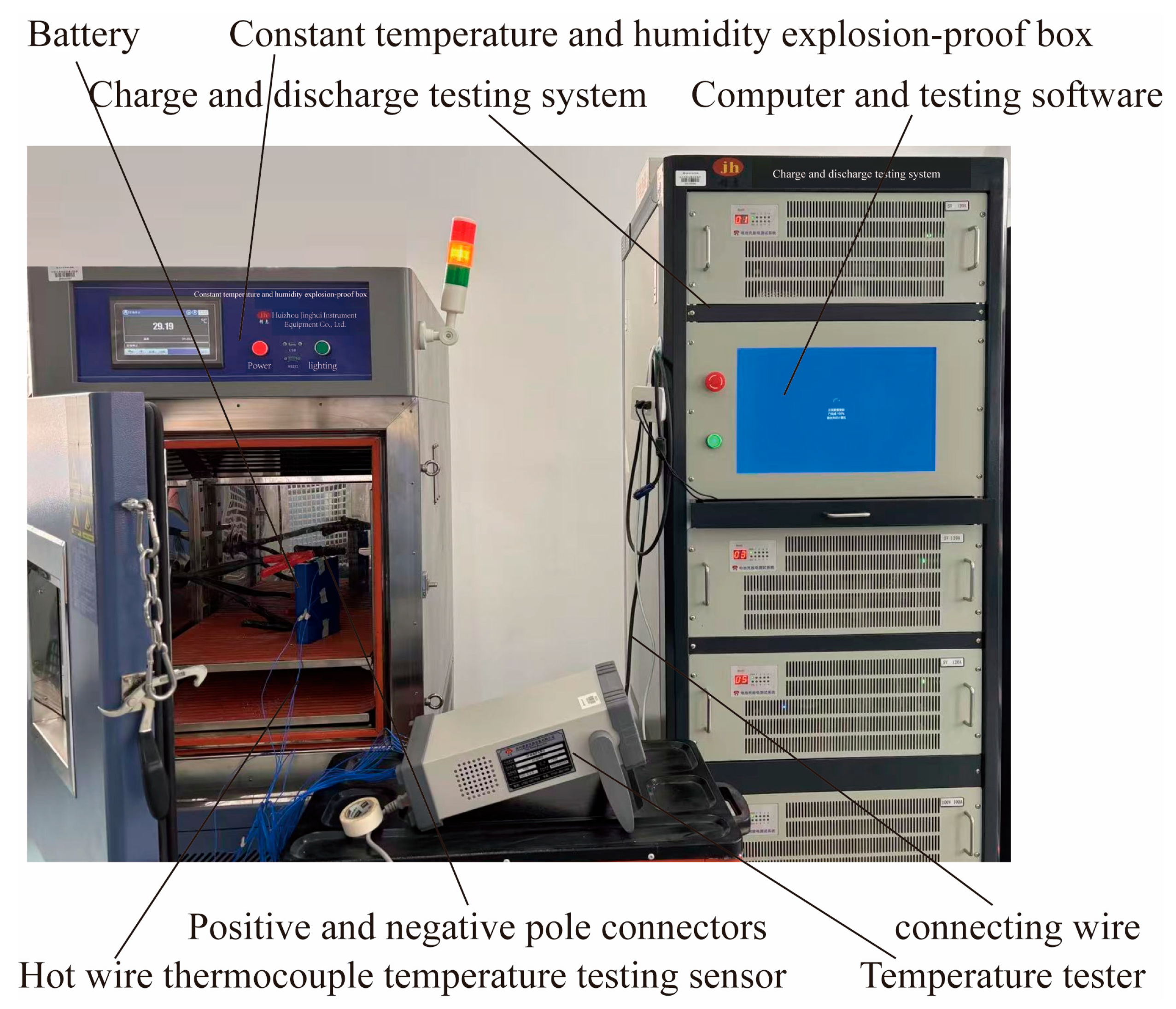

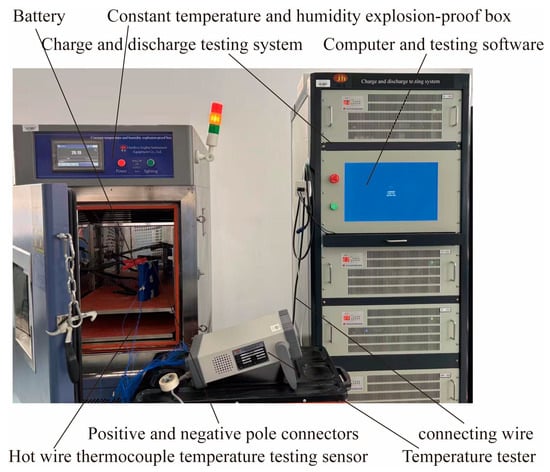

To validate the model accuracy, temperature measurement experiments were carried out on square single-cell lithium-ion batteries during charge–discharge processes. The single-cell batteries that were selected to use were LF50K square lithium-ion batteries produced by EVE Energy Co., Ltd. (Huizhou, China) The experimental plan and principle are shown in Figure 1 The experiment uses a battery charging and discharging testing system, a constant temperature and humidity explosion-proof box, a temperature tester, and other experimental equipment produced by Huizhou Jinghui Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd. (Huizhou, China). The battery charging and discharging testing system includes a testing computer and charging and discharging testing software; the test-ready battery shall be placed inside the explosion-proof constant temperature and humidity box located on the left, as shown in the figure. The outer and inner sides of the upper end of the battery are connected by positive and negative electrode connectors and their connecting wires, respectively; the end probe of the thermal-couple temperature measuring wire is contacted with the surface of the battery to be tested, and they are firmly stuck together with adhesive tape. The other end of the temperature measuring wire is connected to the temperature tester.

Figure 1.

Experimental scheme for charging and discharging lithium battery.

The power supplies of the battery charge–discharge testing system and the prismatic battery test rack are turned on, then the computer located in the middle of the testing equipment is switched on. Through the charge–discharge testing software, the battery can be set to perform charge–discharge operations under different working conditions, and real-time changes in parameters such as battery voltage, current, capacity, and temperature can be obtained. This experiment was conducted under the condition of 298.15 K; the initial temperature of the battery before operation was estimated to be 298.15 K. The battery was set to discharge at a constant current at a 3C rate, and the temperature data of this single-cell battery during the constant-current discharge at a 3C rate was obtained through the experiment.

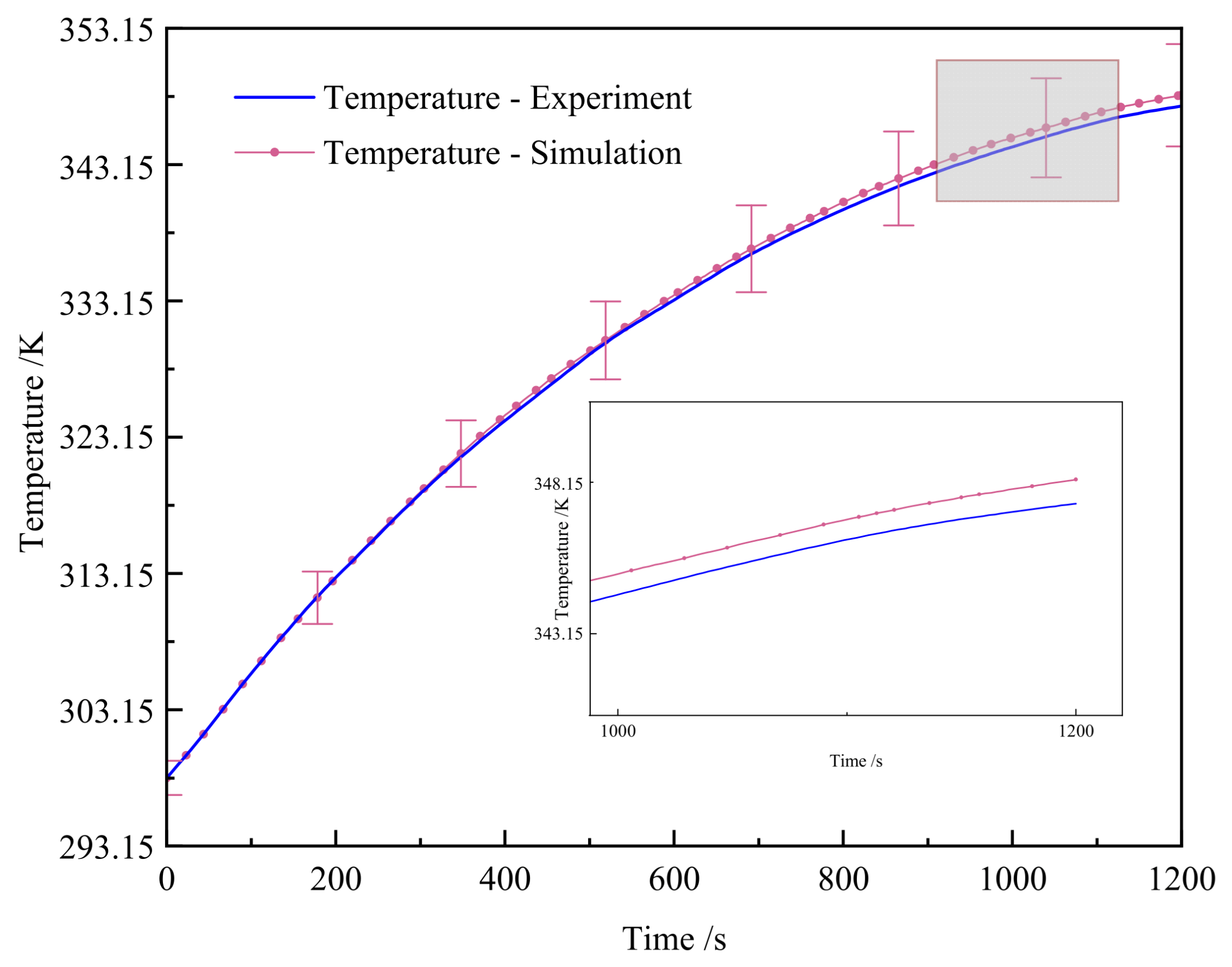

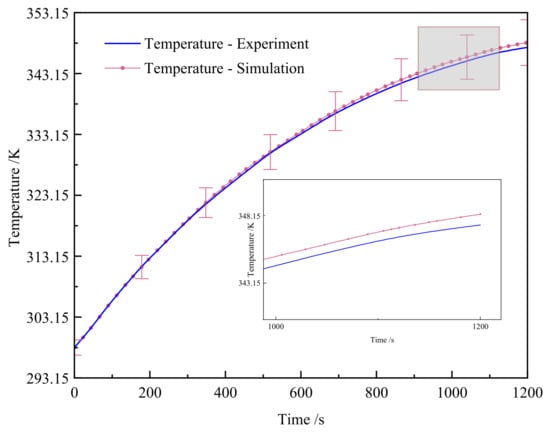

Figure 2 presents the experimental results of temperature variation over time alongside the simulation results. As observed in the figure, the maximum discrepancy between the experiment and simulation arises at 1200 s. At this time, the experimentally determined temperature is 348.19 K and the simulated temperature is 347.45 K, with a difference of 0.74 K and an error of 2.13%. The simulation model is reliable. Due to the optimal operating temperature range of batteries generally being 20 °C~45 °C, which is 293.15 K~318.15 K, reasonable heat dissipation should be carried out for the battery during 3C rate discharge to ensure that it functions within the optimal temperature range for operation. This article uses liquid cooling to dissipate heat from the battery.

Figure 2.

Simulation and experimental result curve of single battery surface temperature.

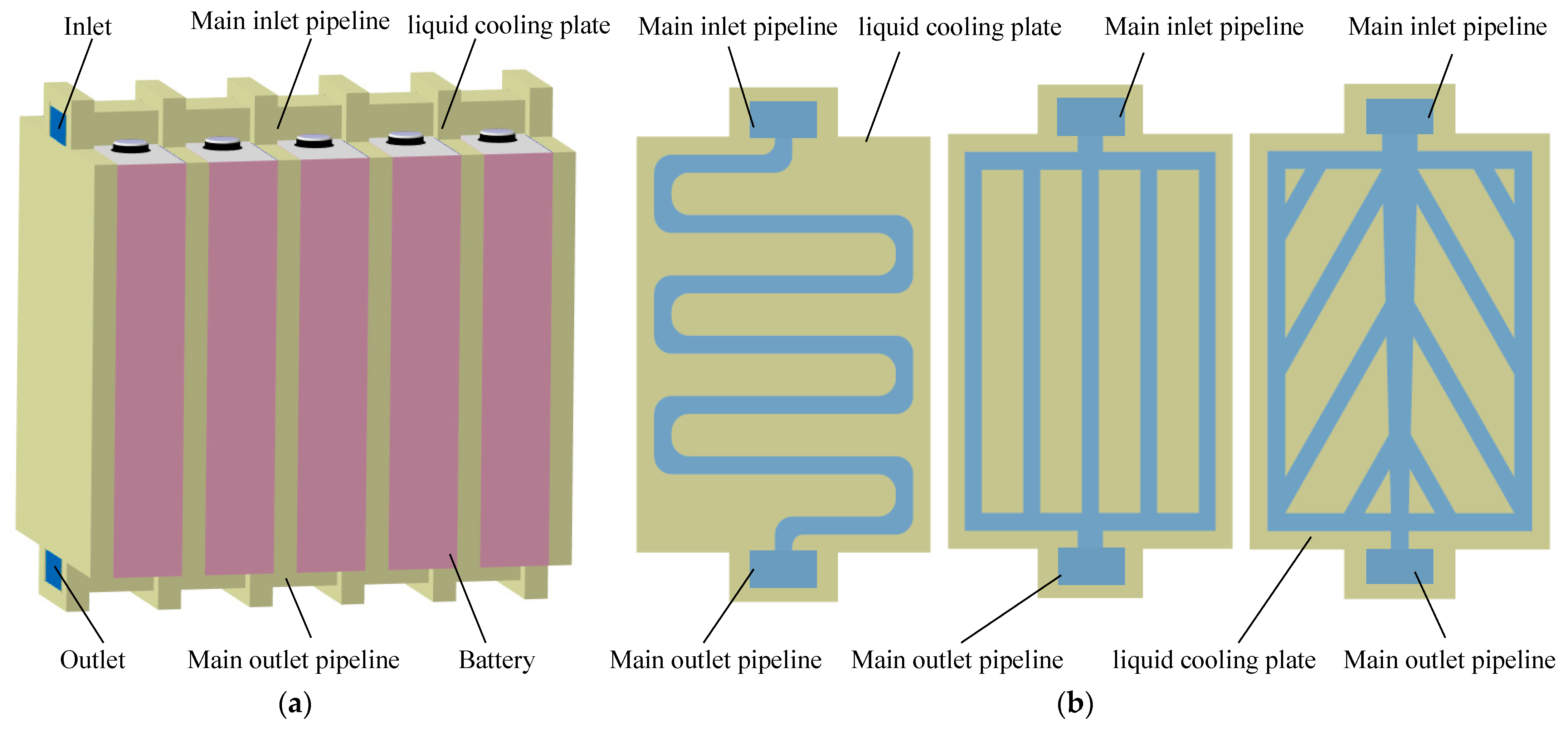

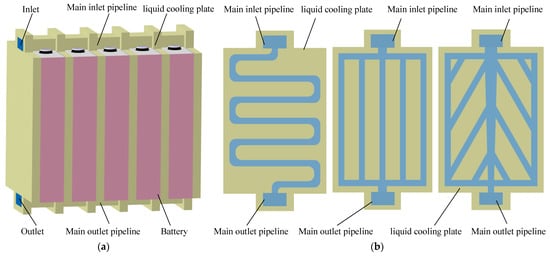

3. Design and Analysis of Different Heat Dissipation Systems

To study the liquid cooling effect of lithium batteries, the LF50K square battery mentioned above was taken as the studied object. Five individual batteries were connected in a series to form a battery module, and the five batteries were numbered from left to right: Battery 1, Battery 2, Battery 3, Battery 4, and Battery 5. As shown in Figure 3, in the initial plan, the inlet is set in the upper left corner, and the outlet is set in the lower right corner. To achieve a good heat dissipation, a cooling plate is installed between every two adjacent individual cells, for a total of six cooling plates. Three different types of liquid flow channels are designed inside the liquid cooling plate: a direct flow channel, a serpentine channel, and a leaf vein channel. The inlet width of the leaf vein liquid cooling channel is greater than the outlet width (as shown in the diagram on the right of the liquid cooling channel scheme in Figure 3b, with upper inlet and lower outlet), the middle channel’s angle β is 3°, each leaf vein channel’s width B is 8 mm, and the initial angle α between the leaf vein and the vertical direction is 30°. In order to ensure comparability among the three schemes, the width and height of different liquid cooling channels in the figure are all 8 mm.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional model of lithium battery module cooling system: (a) structure of liquid cooling system; (b) liquid cooling channel scheme.

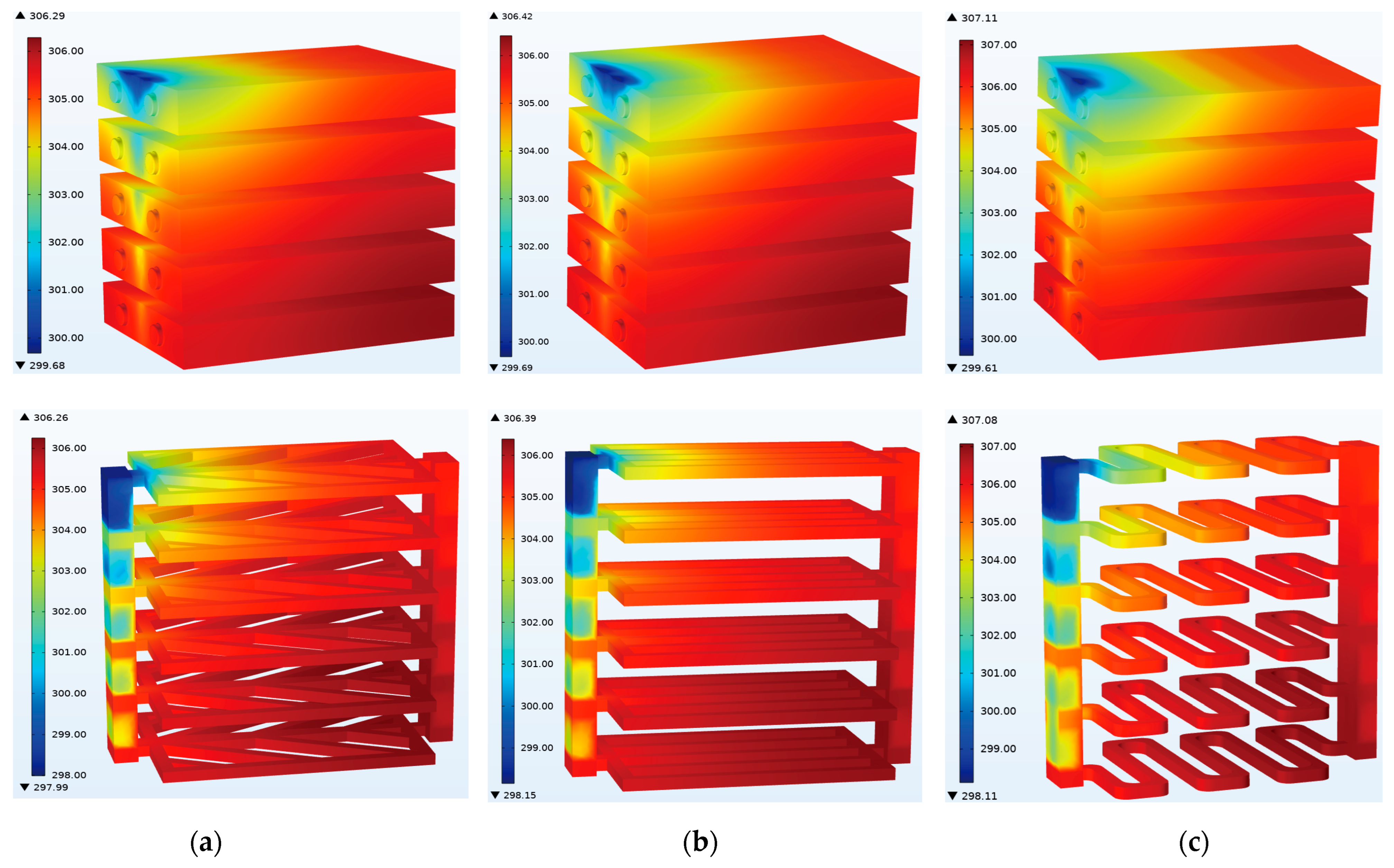

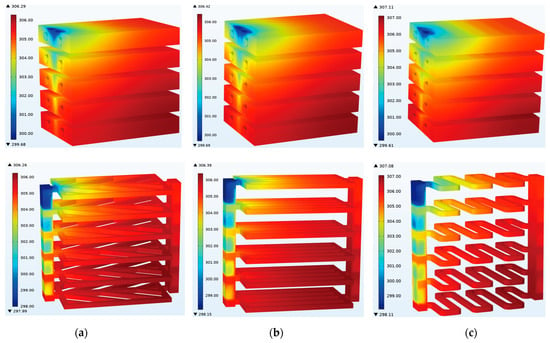

Three different schemes were set up to discharge the power battery at a 3C rate, with a 0.002 m/s flow velocity. The effects of different structures on the cooling of the lithium battery module were obtained, and the results are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Figure 4 shows the temperature cloud maps of the coolant and battery in different channel structures during 3C discharge. The top three are battery temperature cloud maps, and the bottom three are coolant temperature cloud maps. Overall, the temperature changes in the three different structures of batteries and coolant are relatively similar, with the coolant flowing in from the top left and flowing out from the bottom right. Consequently, regions near the left inlet are characterized by lower temperatures for both the coolant and the battery, while temperatures demonstrate an increasing trend in the direction of the bottom right. Furthermore, when conducting a longitudinal comparison, it is observed that the coolant maintains a temperature slightly lower than the battery.

Figure 4.

Temperature cloud maps of coolant and batteries with different channel structures: (a) vein channel; (b) direct flow channel; (c) serpentine channel.

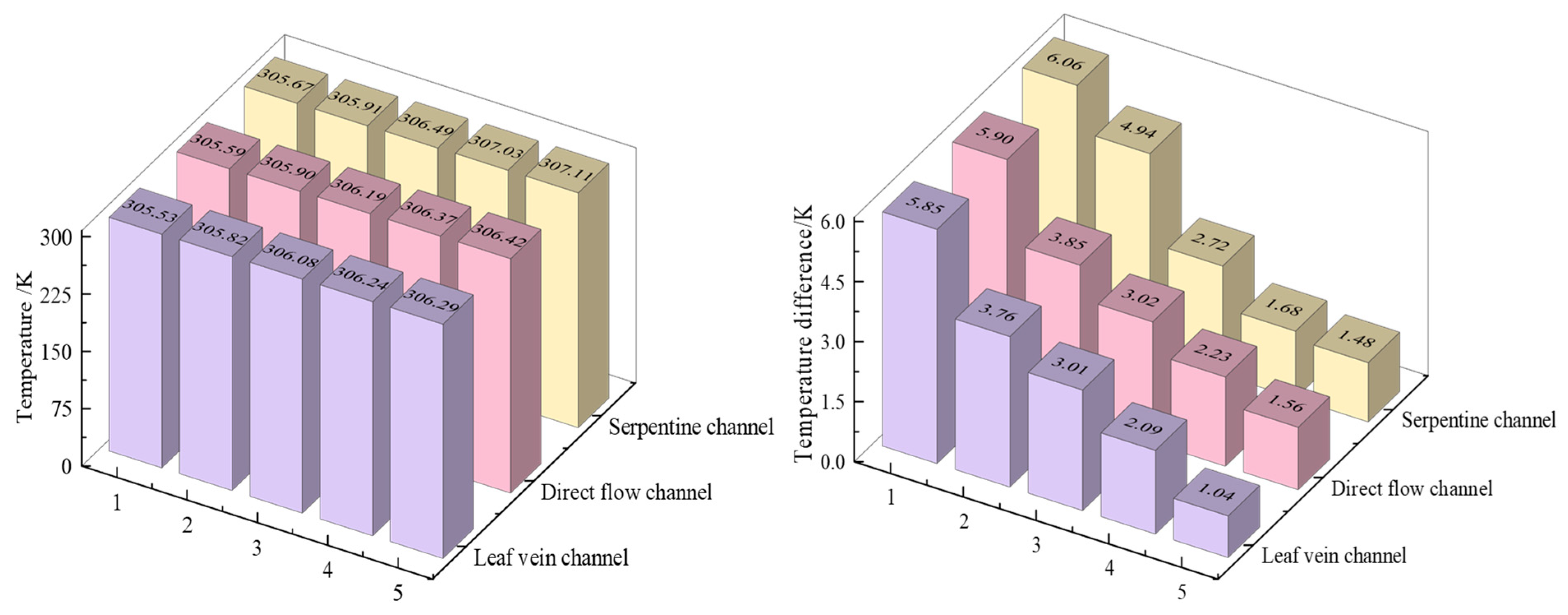

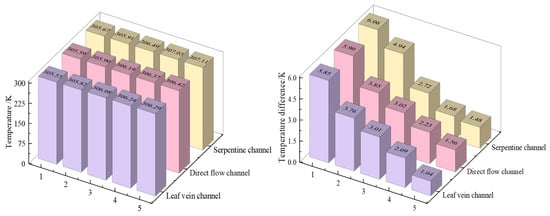

Figure 5.

Maximum temperature and temperature difference in different flow channels.

Figure 5 shows the maximum temperature and temperature difference of five batteries obtained through simulations under different channel structures. The numerical simulation analysis results of three different flow channels show that the serpentine flow channel scheme produces the maximum temperature with the highest numerical value, attaining 307.11 K, followed by the straight flow channel scheme, with a maximum temperature of 306.42 K, while the leaf vein flow channel scheme has the smallest maximum temperature, which is 306.29 K. From the perspective of temperature difference variation, all three different flow channels exhibit a consistent pattern: Battery 1 has the highest temperature difference, while Battery 5 has the lowest. Specifically, a gradual downward trend in the temperature difference in the batteries is observed as one moves from the top to the bottom. This phenomenon occurs due to the gradual decrease in the cooling efficiency of the coolant after it flows through the preceding channels, which in turn impairs its capacity to regulate the temperature of subsequent batteries. Notably, the decrease in cooling efficiency correlates with a diminished temperature difference. In terms of quantitative results, the serpentine channel demonstrates the maximum temperature difference, achieving 6.06 K. On the other hand, the minimum temperature difference is found in the biomimetic leaf vein channel for the No. 5 battery, which is 1.04 K. In summary, in terms of the maximum temperature, the relationship is Tmax (serpentine flow channel) (307.11 K) > Tmax (straight flow channel) (306.42 K) > Tmax (leaf- vein flow channel) (306.29 K); in terms of the temperature difference, the order is similarly ΔT (serpentine flow channel) > ΔT (straight flow channel) > ΔT (leaf vein flow channel). Therefore, the study in this paper tends to select the liquid cooling structure scheme with the leaf vein flow channel.

4. Results and Discussion of Heat Dissipation Performance

For the selection of appropriate parameters for the leaf vein channel structure and to facilitate follow-up optimization work, the subsequent analysis will assess the impact of different factors within the leaf vein channel heat dissipation system on its cooling effect. The following five factors are selected, and in the subsequent analysis, each parameter will be set in accordance with the table below:

4.1. Influence of Inlet–Outlet Channel Angle on Cooling Effect

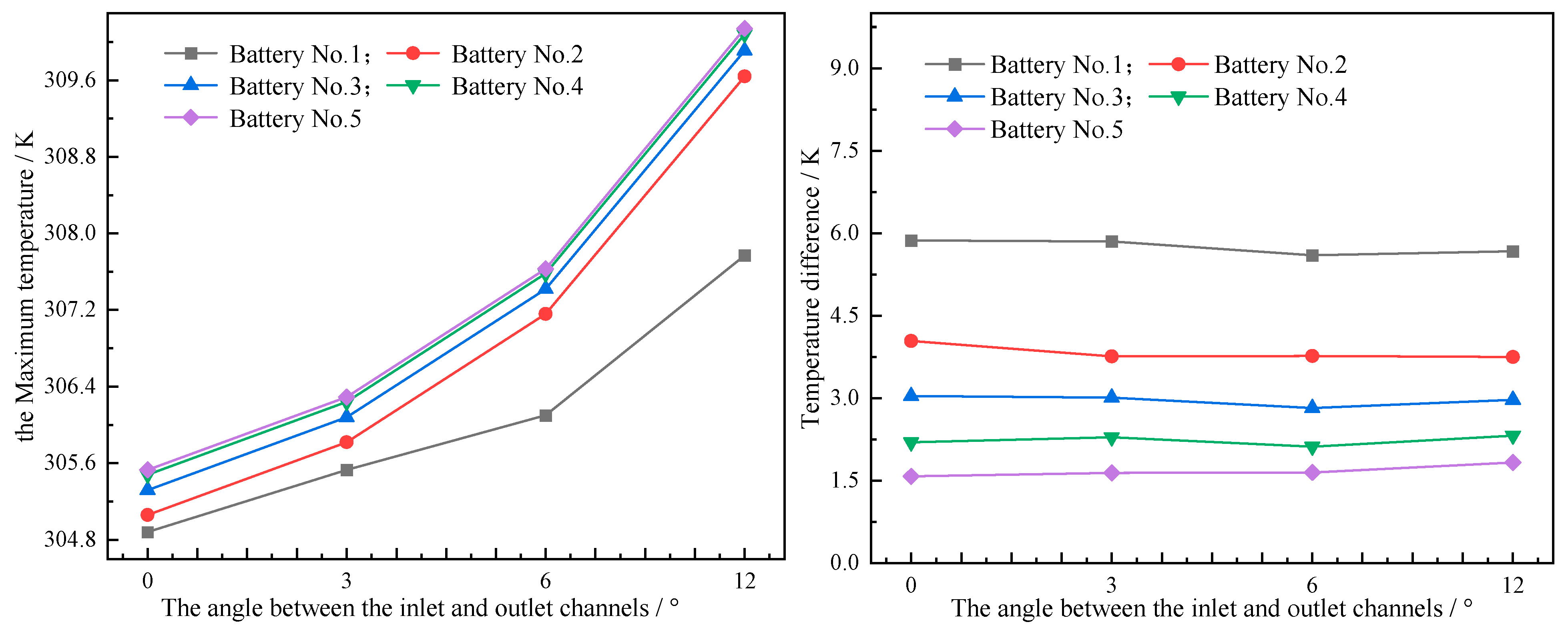

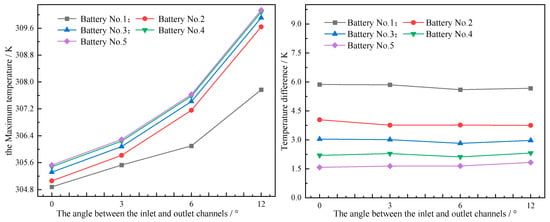

Based on the above-mentioned leaf vein fluid flow channel, the angle β between the outlet and inlet channels was changed, and the angles β were set to 0°, 3°, 6°, and 12°, respectively. The power battery was discharged at a 3C rate. Since specifying the coolant via the mass flow rate is more appropriate in studies examining how inlet and outlet flow channels affect cooling performance, the mass flow rate can be derived via the relationship between the mass flow rate and the flow velocity (qm = v × A × ρ). Specifically, when the inlet flow velocity is 0.002 m/s, the calculated mass flow rate is 0.128 g/s. Consequently, a mass flow rate of 0.128 g/s was adopted as the operating parameter. The effect of the angle between the inlet and outlet channels on battery cooling performance was then analyzed, and these analytical results are provided in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Curve of temperature at different inlet and outlet angles.

As illustrated in Figure 6, the batteries’ maximum temperature exhibits a positive correlation with the angle between the inlet and outlet channels. Specifically, it increases as the channel angle grows. As the angle increases, each battery’s maximum temperature rises progressively. At an inlet–outlet angle of 12°, the maximum temperature of Battery 5 measures 310.14 K. From the temperature difference curve, it can be noted that, under varying angles between the inlet and outlet, the temperature difference in the five batteries exhibits no obvious variation. This indicates that the inlet–outlet angle exerts only a minor effect on the temperature difference in each individual battery. Therefore, from the perspective of improving heat dissipation performance, a small angle between the inlet and outlet should be selected.

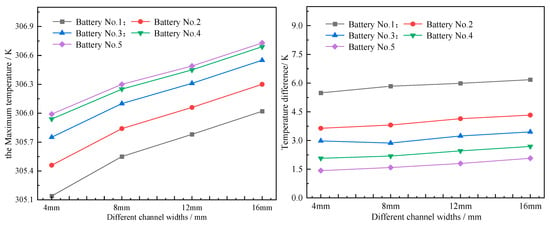

4.2. Influence of Channel Width on Cooling Effect

To evaluate the effect of the width of the flow channel on the cooling of power batteries, four structures were designed with flow channel widths B of 4 mm, 8 mm, 12 mm, and 16 mm. We set the liquid flow rate to 0.002 m/s, discharged the battery at a rate of 3C, and simulated the influence of channel width on cooling performance as shown in Figure 7. It displays the maximum temperature and temperature difference curves corresponding to various channel widths. As can be observed from these curves, both the maximum temperature and temperature difference exhibit a positive functional correlation with the channel width. Among them, the maximum temperature of Battery 5 is the highest, and, when the channel width is 4 mm, 8 mm, 12 mm, and 16 mm, the maximum temperatures are 305.99 K, 306.30 K, 306.49 K, and 306.73 K, respectively. Battery 1 has the maximum temperature difference, which is 5.49 K, 5.84 K, 5.99 K, and 6.18 K, respectively. Hence, from the perspective of achieving a reduction in the battery’s maximum temperature and temperature difference, an excessively large channel width is not recommended.

Figure 7.

Curve of temperature and for different channel widths.

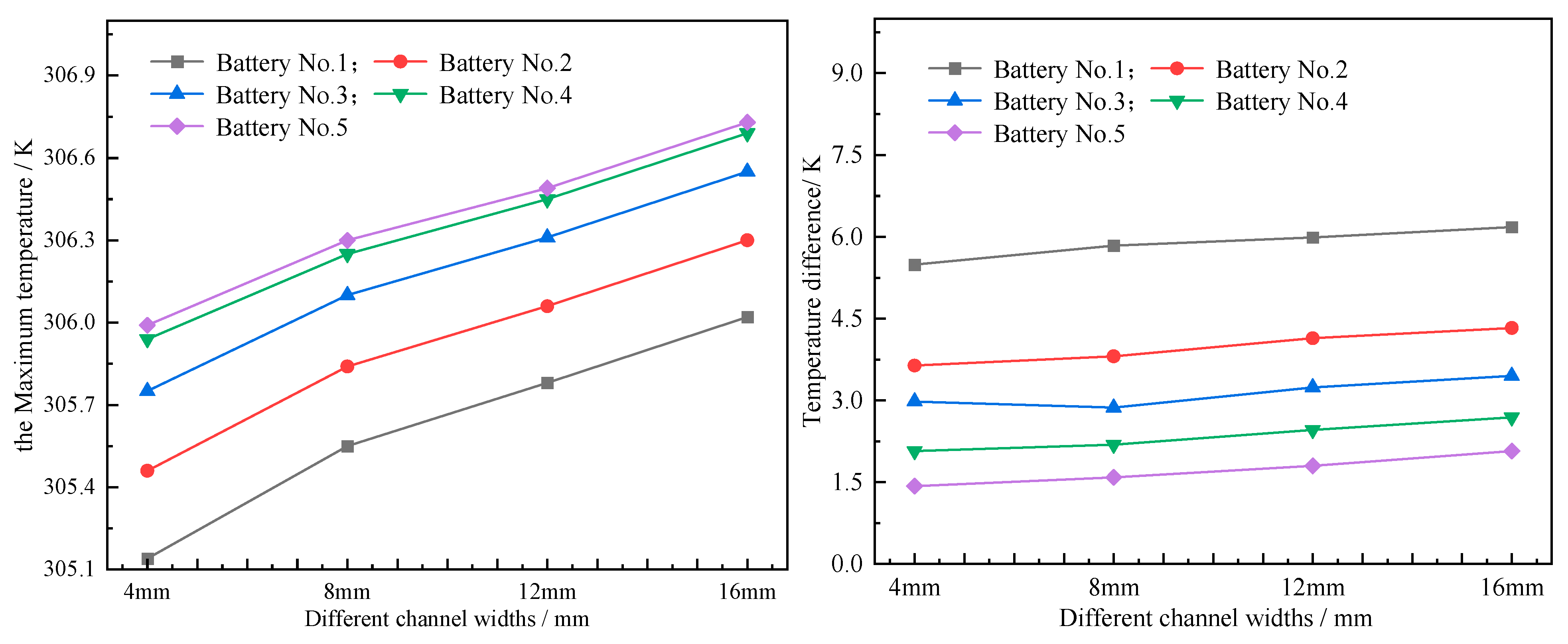

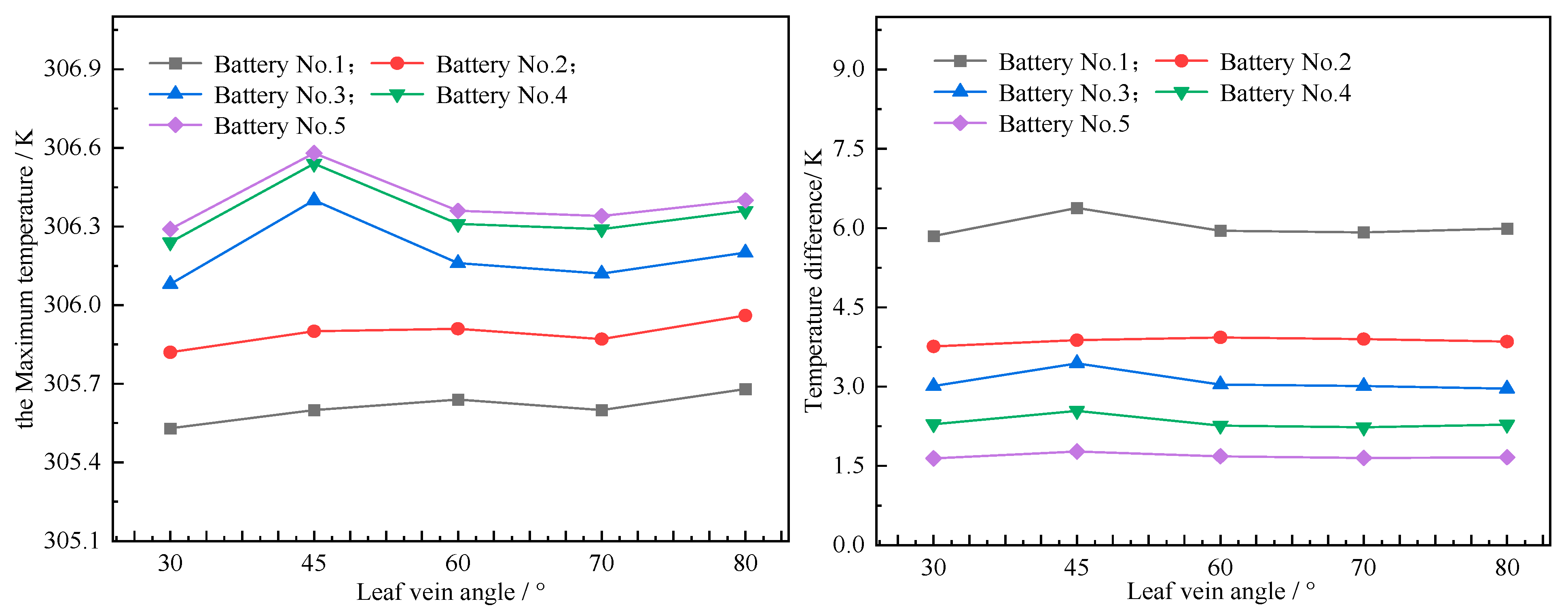

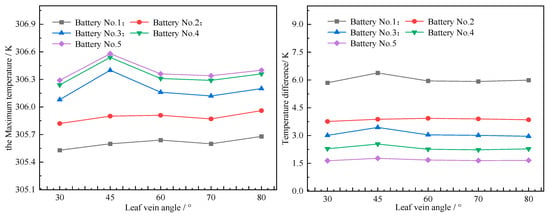

4.3. Influence of Leaf Vein Inclination Angle on Heat Dissipation Effect

To investigate the cooling effect of the leaf vein inclination angle α on power batteries, five schemes were designed with leaf vein inclination angles α of 30°, 45°, 60°, 70°, and 80°, respectively. The battery underwent discharge at a 3C rate, with the coolant flowing at a rate of 0.002 m/s. The simulation results of the five different schemes are shown in Figure 8. As shown in the figure, for Battery 1 and Battery 2, the maximum temperature exhibits a gradual upward trend with the increase in angle, but the increase is not significant; for Batteries 3, 4, and 5, as the angle increases, the maximum temperature initially rises, subsequently decreases, and finally tends to stabilize gradually. When the angle reaches 45°, the maximum temperature is 306.58 K. An analysis of the temperature difference curve reveals that the temperature difference in Batteries 2–5 shows negligible variation with changes in angle, remaining nearly constant throughout. In contrast, for the first battery, the maximum temperature difference reaches 6.38 K when the angle is set to 45°. Overall, when the angle is 70°, the maximum temperature and temperature difference generated are the smallest. At this time, the maximum temperature of the No. 1 battery is 305.60 K, and the temperature difference is 5.92 K.

Figure 8.

Curve of temperature at different leaf vein angles.

4.4. Influence of Liquid Flow Velocity on Cooling Effect

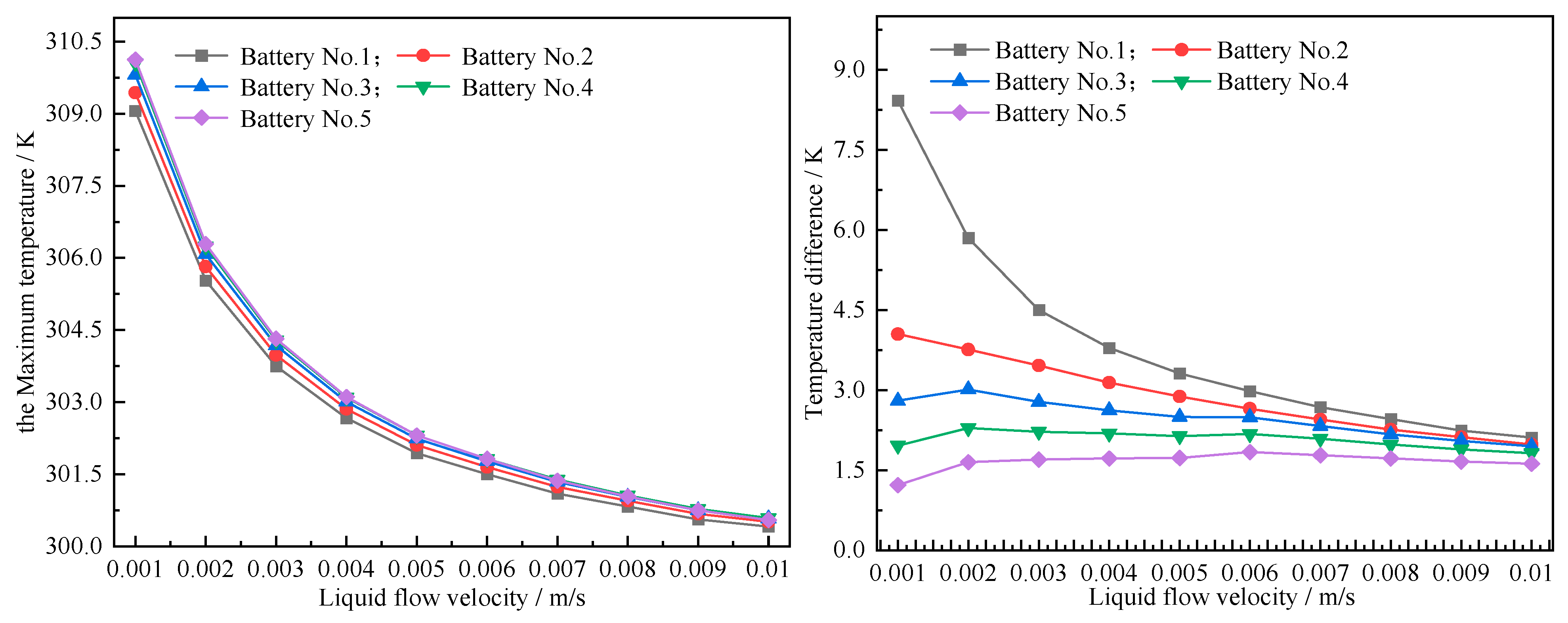

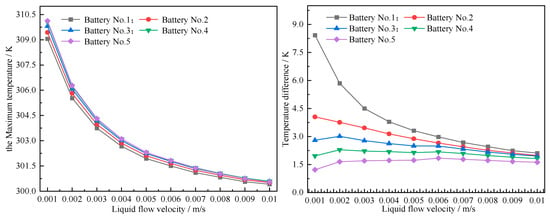

As the cooling medium circulates within the liquid coolant channel, the coolant absorbs and removes the heat that is transferred from the power battery to the liquid cooling plate during its flow. This process enables the coolant to exert an effective cooling effect on the power battery. Therefore, the influence of the flow rate of is also one of the factors that should be considered in the design. We set the liquid flow rate at 0.001 m/s with intervals of 0.001 m/s as a gradient, gradually increasing it to 0.01 m/s. The battery is discharged at a 3C rate, and the simulation results of the effect of the coolant flow rate on cooling performance are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Curve of temperature for different liquid flow velocities.

From these curves, clearly, the maximum temperature of each battery decreases as the liquid flow rate increases, with Battery 5 exhibiting the highest peak temperature. When the liquid flow rate starts from 0.001 m/s and gradually increases in a gradient of 0.001 m/s to 0.01 m/s, the highest temperatures of the 5th battery are 310.13 K, 306.29, 304.32, 303.11 K, 302.31 K, 301.5 K, 301.1 K, 300.83 K, 300.56 K, and 300.41 K, respectively, with a maximum difference of 9.72 K. The temperature difference in each battery varies at different flow rates, among which the temperature difference in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th batteries does not change much with the flow rate, while the temperature difference in the 1st and 2nd batteries decreases with the flow rate. The temperature difference in the 1st battery changes the most. An increase in the flow rate from 0.001 m/s to 0.01 m/s leads to a reduction in the temperature difference in the 1st battery, which decreases from 8.42 K to 2.11 K. Notably, during the initial stage of liquid flow rate adjustment, the temperature difference in Battery 5 tends to increase with the gradual rise in the liquid flow rate. This is because the liquid flows to Battery 5 after passing through Batteries 1, 2, 3, and 4 in the heat dissipation system. When the liquid flow reaches Battery 5, its temperature has obviously risen, resulting in a slightly poor heat dissipation effect on Battery 5. Especially when the liquid flow rate at the inlet is low (0.001 m/s), the liquid cooling effect on Battery 5 as a whole is relatively poor, making the temperature difference in Battery 5 itself low. Nevertheless, as the flow rate rises, the liquid cooling performance of Battery 5 improves gradually, with a slight increase in temperature difference. However, once the flow rate hits a certain threshold, any further increase will instead lead to a reduction in the temperature difference.

Therefore, to reduce the highest temperature of the battery, improve the heat dissipation performance of the power battery, and improve the temperature balance of the battery, the liquid flow rate should not be set too low. Under such circumstances, a flow velocity of 0.01 m/s is more beneficial for enhancing the cooling performance; however, raising the flow rate will lead to a higher energy consumption. Therefore, when designing the matching of power batteries in real vehicles, the setting of the flow rate of power batteries should be reasonably considered.

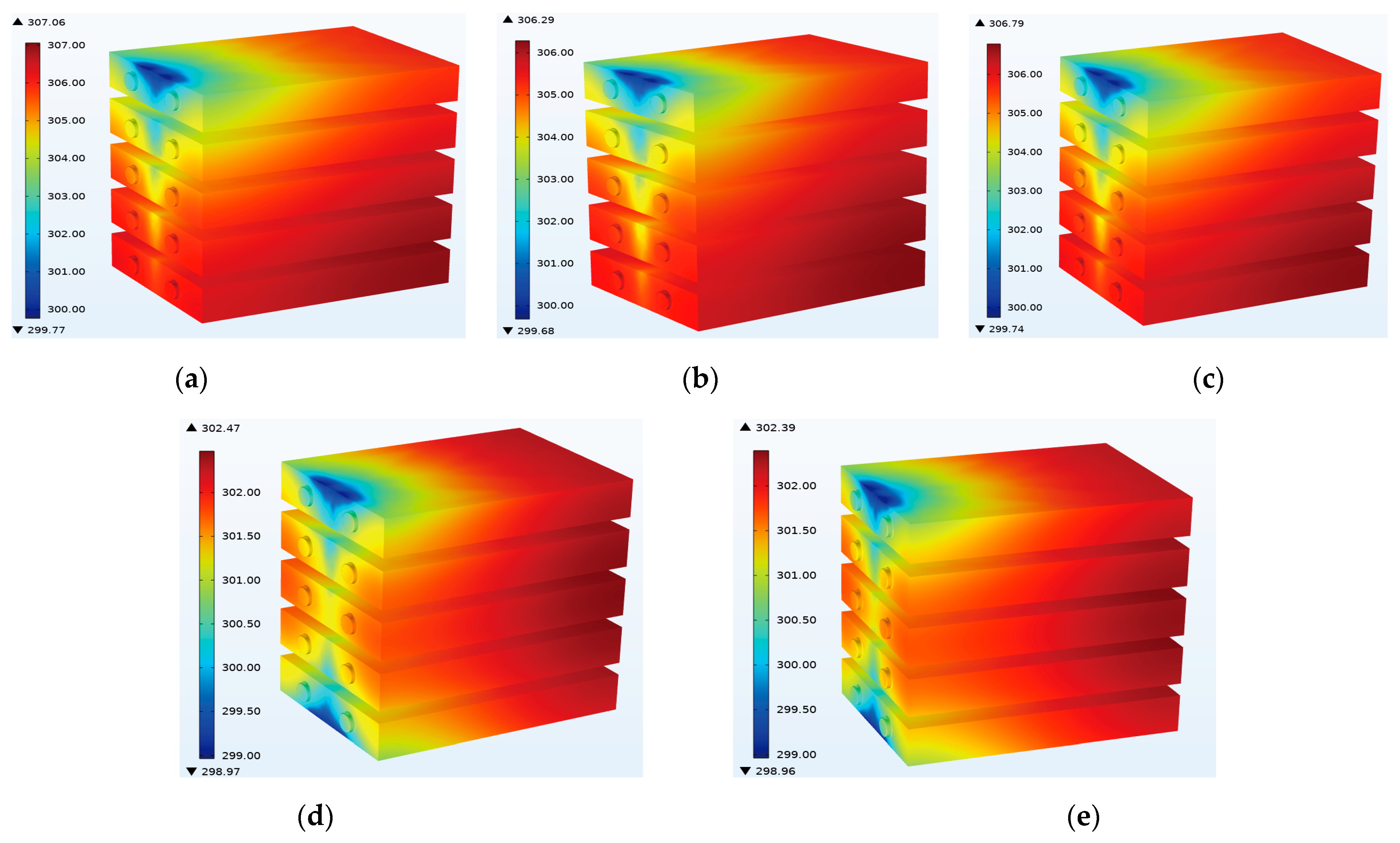

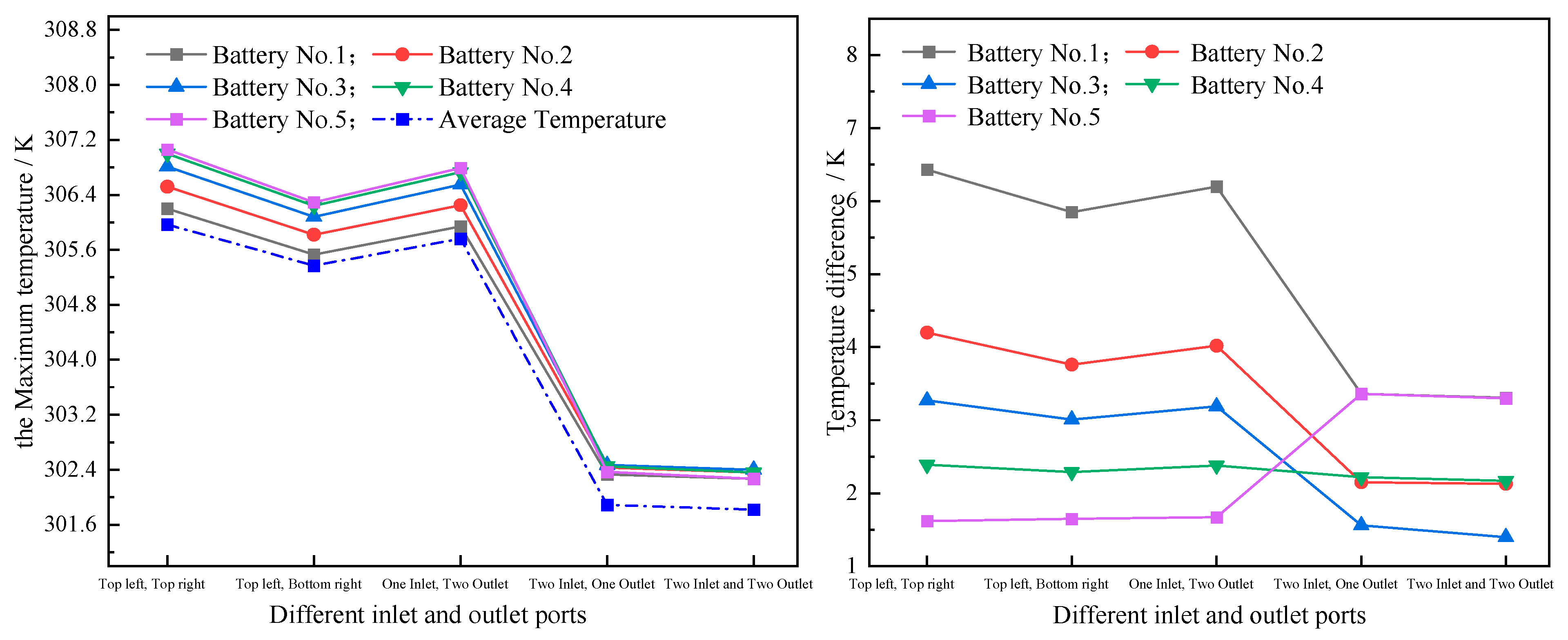

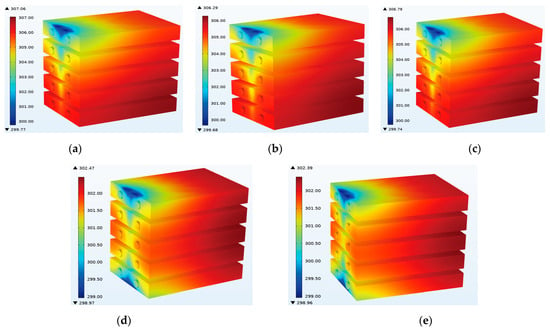

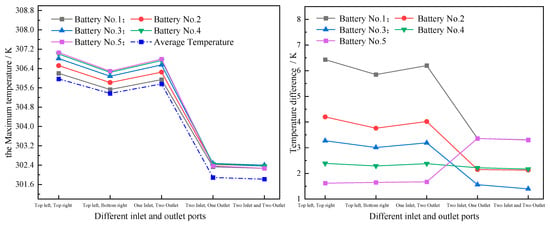

4.5. Effect of Different Inlet–Outlet Ports on Cooling Effect

To study the impact of various inlets–outlets on the cooling effect, in addition to the initial scheme of water inlet at the top left corner and water outlet at the bottom right corner (as shown in Figure 3a), four other schemes with different inlet and outlet configurations were designed. These five schemes are called top left and bottom right, top left and top right, one in two out, two in one out, and two in two out. The simulation conditions were set in accordance with Table 3, and the results are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Table 3.

Parameter configuration of various impact factors.

Figure 10.

Cloud map of battery temperature at different inlet and outlet ports: (a) top left, top right; (b) top left, bottom right; (c) one inlet, two outlet; (d) two inlet, one outlet; (e) two inlet and two outlet.

Figure 11.

Curve of temperature at different inlet and outlet ports.

According to the temperature cloud maps of the batteries at different inlet–outlet ports, the lowest temperature in the first three schemes (upper left, upper right, upper left, lower right, and one inlet and two outlets) is concentrated at the inlet port in the upper left position. The higher the position to the right and lower, the higher the battery temperature; the latter two schemes (two in one out and two in two out) have the lowest temperature in the middle part of the upper left and lower left of the battery module. The further to the left middle or right, the higher the temperature. As shown in Figure 11, it is evident that the maximum temperature of Battery 1 is the lowest across all schemes, and the maximum temperature increases with an increase in the battery serial number. Therefore, Battery 5 has the maximum temperature; horizontally comparing the five different schemes, the highest temperature generated by the upper left and upper right scheme was 307.06 K, while the lowest temperature generated by the two in and two out scheme was 302.39 K. Of course, although the highest temperature of the two in and one out scheme was higher than that of the two in and two out scheme, the ratio was relatively close, with a difference of 0.08 K. From the average temperature, it can also be clearly seen that the two in and two out scheme produced the lowest average temperature, which was 301.82 K. From the temperature difference changes, the temperature difference in the first three schemes (upper left and upper right, upper left and lower right, and one in and two out) decreased from Battery 1 to Battery 5, with Battery 1 having the largest temperature difference, reaching 6.4 K. At 3 K, the temperature difference between Battery 1 and Battery 5 and Battery 2 and Battery 4 in the two in one out and two in two out schemes is relatively close, with Battery 3 having the smallest temperature difference. Among them, the temperature difference in the two in two out scheme is the smallest, at 1.4 K.

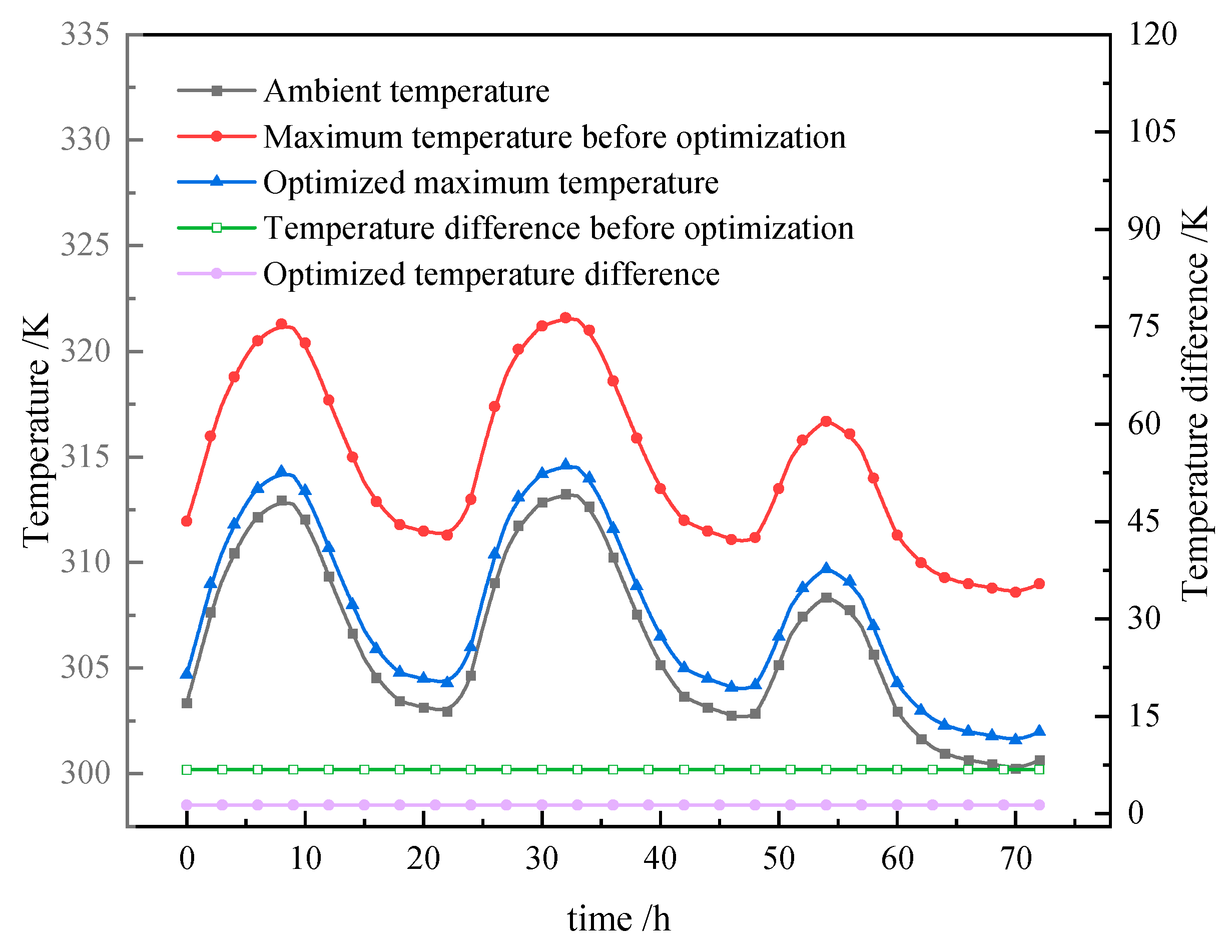

5. Structural Optimization and Result Analysis of Heat Dissipation System

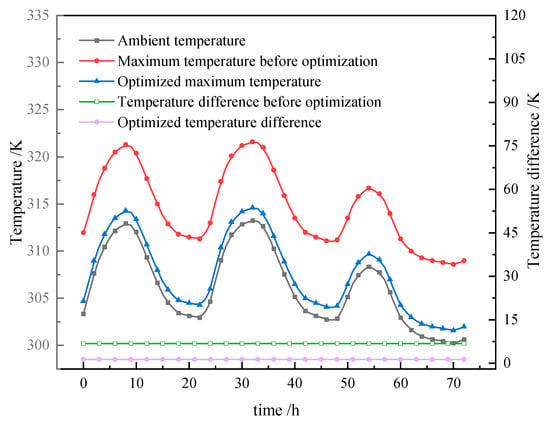

From the above analysis, it can be concluded that, during the 3C discharge operation of the battery module at an ambient temperature of 298.15 K, its temperature difference has exceeded the optimal temperature range for operation. Furthermore, if the ambient temperature increases, the maximum operating temperature of the battery module will also go beyond this optimal range. Therefore, the structure needs to be optimized. Based on the analysis results in 3.2, keeping the angle β of the angle between the inlet and outlet channels unchanged at 3°, the following optimizations are made for the structure and related parameters of the heat dissipation system:

(1) The leaf vein angle α increased from 30° to 70°;

(2) The leaf vein width B decreased from 8 mm to 4 mm;

(3) The air inlet and outlet have been changed from the original top left and bottom right mode to a two in two out mode;

(4) The liquid flow velocity increases to 0.06 m/s.

According to meteorological data, the highest temperature in Guangzhou city on 22 July and 3 August 2024 was the highest of the year, reaching 40.1 °C, or 313.25 K. Due to the highest average temperature in July of the year, the temperature for three consecutive days of 72 h from 6:00 am on 21 July to 6:00 am on 24 July 2024 was taken as the ambient temperature. The analysis and comparison showed the cooling effect of the battery module before and after optimization during a 3C discharge. As shown in Figure 12, the black curve in the middle represents the hourly ambient temperature for the hottest three consecutive days in July 2024. Variations in the ambient temperature led to changes in the highest temperature; its trend is consistent with the change in ambient temperature. The bottom two curves show the temperature difference before and after optimization. After 72 consecutive hours, the temperature difference remains almost unchanged, so the ambient temperature does not play a decisive role in the temperature difference change.

Figure 12.

Comparison of temperature under different environmental temperatures before and after optimization.

Under the same environmental temperature conditions, the optimized structure of the battery module produces a lower maximum temperature and temperature difference during operation compared to before optimization. The highest temperatures for three consecutive days were 312.95 K, 313.25 K, and 308.35 K, respectively. Before optimization, the highest temperatures generated during structural operation were 321.29 K, 321.59 K, and 316.69 K, respectively. The highest temperatures for the first two days exceeded the battery’s optimal working temperature range by 318.15 K. After optimizing the structure and related parameters, under the same operating conditions, the highest operating temperatures of the battery were 314.29 K, 314.60 K, and 309.69 K, respectively. Compared with before the optimization, the highest temperatures decreased by 7 K, 6.99 K, and 7 K, and the highest temperatures every day were controlled within the temperature range for optimal performance. The temperature difference generated by the structure before optimization during battery operation was 6.77 K, and, after optimization, the temperature difference decreased by 5.47 K to 1.30 K, which is also within the temperature range for optimal performance. Therefore, the optimized structure improves the cooling performance of the lithium battery, ensuring that the temperature generated during the high-rate operation of the battery is within the temperature range for optimal performance.

6. Conclusions

This study designed a novel biomimetic leaf vein-shaped liquid flow channel lithium-ion power battery. The COMSOL was used to simulate and analyze the effects of different liquid flow channel structures, inlet and outlet channel angles, channel widths, flow velocities, leaf vein inclination angles, and different inlet and outlet ports on the cooling effects of power batteries, and structural optimization was carried out. The conclusions are as follows:

(1) By combining the heat generation and computational fluid dynamics control equations of lithium-ion power batteries, a three-dimensional model of the lithium-ion battery module is established. The model is numerically simulated using multiphysics coupling software, and, compared with experimental results, the highest temperature difference is 0.74 K, indicating the high reliability of the model.

(2) Comparing the cooling effects of the serpentine liquid cooling channel, direct flow liquid cooling channel, and biomimetic leaf vein channel, it was found that the highest temperature of the leaf vein channel was the lowest, at 306.29 K, which has significant advantages in the liquid cooling performance of lithium battery modules.

(3) The inlet and outlet angles of the biomimetic leaf vein channel liquid cooling structure and the width of the liquid flow channel are both in an increasing function relationship with the highest temperature. As the angle increases, the highest temperature of each individual battery in the lithium battery module rises gradually, with Battery 5 exhibiting the maximum temperature in the entire module. As the angle between the inlet and outlet rises to 12°, the maximum temperature of Battery 5 within the lithium battery module attains 306.89 K. For Battery 1, its temperature difference is the largest (surpassing 6 K), with the largest temperature difference observed overall when the angle is set to 0°. However, overall, the increase in the angle has little influence on the temperature difference; when the liquid flow channel increases from 4 mm to 16 mm, the highest temperature of the lithium battery increases by 0.5 K. Although the temperature difference changes relatively little, it gradually increases with the increase in width. From the perspective of improving heat dissipation performance, a liquid flow channel with a smaller width should be selected; the influence of the leaf vein angle on heat dissipation performance fluctuates. With an increase in the leaf vein angle, the maximum temperature and temperature difference first increase and then decrease. It is also observed that the liquid flow rate has a decreasing relationship with temperature: when the flow rate is adjusted from 0.001 m/s to 0.01 m/s, the lithium battery’s maximum temperature drops by 9.72 K, and its temperature difference drops by 6.31 K. When the flow rate surpasses 0.006 m/s, however, the decrease in temperature difference is no longer notable. Among the five compared inlet–outlet schemes, the two inlet and two outlet scheme yields the lowest maximum temperature and temperature difference.

(4) The optimization of the liquid cooling heat dissipation system structure led to a maximum temperature reduction of 7 K and a temperature difference reduction of 5.47 K. This study offers references and guidance for the design and analysis of liquid cooling heat dissipation systems applied to lithium battery packs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, H.D.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, H.D.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, funding acquisition, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Special Innovation Fund for General Colleges and Universities in Guangdong Province, grant number K0724003.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, C.; Sun, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, L.; Tang, Y. A review on the liquid cooling thermal management system of lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Energy 2025, 375, 124173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; Hu, J.; Chen, M.; Weng, J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. Effects of abusive temperature environment and cycle rate on the homogeneity of lithium-ion battery. Thermochim. Acta 2019, 676, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.X.; E, J.Q.; Tian, S.C.; Huang, Y.X.; Song, X.Y. Effect of composite cooling strategy including phase change material and liquid cooling on the thermal safety performance of a lithium-ion battery module under thermal runaway propagation. Energy 2024, 295, 131093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Xiong, X.; Gao, Q.J.; Fan, Y.W. Performance Study of Cylindrical Lithium Battery Thermal Management System Based on the Design of Spider Web-like Flow Channel Structure. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 59, 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhu, Y. Surface urban heat island effect and its driving factors for all the cities in China: Based on a new batch processing method. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109818. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, L.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Experimental-numerical studies on thermal conductivity anisotropy of lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 103, 114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Zhang, C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. In-situ characterization approach for heat-generating performances of a pouch lithium-ion battery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 256, 124081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaderi, A.; Veysi, F. Investigation of a water-NEPCM cooling thermal management system for cylindrical 18650 Li-ion batteries. Energy 2022, 244 Pt A, 122570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Liu, J.; Venkateswarlu, B.S.K. Numerical simulation of lithium-ion battery thermal management systems: A comparison of fluid flow channels and cooling fluids. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.K.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, A.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Panchal, S. Computational study on hybrid air-PCM cooling inside lithium-ion battery modules with varying number of cells. J. Energy Storage 2023, 67, 107649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalesh, T.; Narasimhan, N. Introducing new designs of mini-channel cold plates for the cooling of Lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2020, 479, 228775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.Y.; Jin, Y. Design and Optimization of Liquid cooled Parallel Serpentine Flow Channel Structure for Lithium Battery Modules. Electr. Power Eng. Technol. 2024, 43, 160–169, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Ma, S.; Jin, H.; Wang, R.; Jiang, Y. Performance analysis of liquid cooling battery thermal management system in different cooling cases. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.H.; Qiu, X.H.; Wang, S.F.; Jia, Z. Optimizing a direct flow cooling battery thermal management with bod baffles for electric vehicles: An experimental and simulation study. J. Energy Storage 2023, 74, 109410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Sheng, L.; Kuang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Bi, Q. Pouch lithium-ion battery thermal management by using a new liquid-cooling plate with honeycomb-like fins. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 69, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.G. Structural Design of Lithium-Ion Battery module Cooling System Under Different Charging Rates. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 60, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.W. Design and Simulation Analysis of Liquid Cooling Structure for Vehicle-Mounted Lithium-Ion Power Battery module. Chin. J. Automot. Eng. 2024, 8, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswarlu, B.; Chavan, S.; Joo, S.W.; Kim, S.C.; Nisar, K.S. A numerical investigation of heat transfer performance in a prismatic battery cooling system using hybrid nanofluids. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 66, 105719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.; Xu, J.; Guo, Z.C.; Wang, X.Z.; Shi, C.W. Experimental and numerical investigation of single and double serpentine channel cold plates on the thermal performance of lithium ion pouch battery. J. Energy Storage 2024, 92, 112200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Huang, Z.; Lu, X.; Shi, Y. Symmetrical complex serpentine channel introduction of secondary openings with open Y fins integrated optimization design. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 195, 108620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J. Structural optimization of serpentine channel water-cooled plate for lithium-ion battery modules based on multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2024, 91, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Heat Dissipation Performance of Secondary Flow Serpentine Channel Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chin. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 33, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.Y. Structural Design and Optimization of Liquid-Cooled Parallel Serpentine Flow Channels for Lithium-Ion Battery Modules. J. Energy Storage 2025, 68, 108976. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Y. Multi-objective optimization of heat transfer performance of power battery cold plate based on bionic spider web flow channel. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 72, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.G. Heat Dissipation Performance of Honeycomb CPCM-Water Cooling Composite Cylindrical Lithium Batteries. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 242, 122444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulqader, A.A.; Jaffal, H.M. Comparative investigation on heat transfer augmentation in a liquid cooling plate for rectangular Li-ion battery thermal management. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. Performance Study of Lithium-Ion Battery Thermal Management System Based on Bionic Spider-Web Flow Channel Design. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 236, 126246. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.B. Effect of Fluid on Lithium-Ion Battery Heat Dissipation Performance on Liquid Cooling Plate Based on Sine Function. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 32, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Zong, K.; Xiong, C.W.; Weng, X.; Du, P. Design and heat transfer performance analysis of leaf vein-shaped microchannel heat sink. Chin. J. Eng. Des. 2019, 26, 477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, M.; Ding, X.H.; Ji, Y.D.; Meng, F. Hierarchical Growth Method for Optimal Design of Branching Heat Transfer Structures. China Mech. Eng. 2019, 30, 2668–2674. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F.Z.; Ding, X.H.; Li, H.; Xiong, M. Study on Optimal Design of Liquid Cooling Uniform Temperature Plate Embedded with Hierarchical Vein Structure. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 58, 426–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Pan, Y.H.; Zheng, L.; Fu, H.; Shen, Y.; Hao, M.; Yang, Y.; Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Cheng, W.L. Study on heat transfer enhancement of spray cooling with bionic vein channel structured surface. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 246, 122977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Feng, X.; Zhao, D.; Wang, T.Y.; Li, X.J. Numerical simulation and optimization of bionic leaf-vein structure collector performance in photovoltaic-thermal system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280 Pt 1, 127883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.B.; Nie, J.; Cheng, J.P. Optimizing the air flow pattern to improve the performance of the air-cooling lithium-ion battery module. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, J.Y. Study on thermal management performance of power battery based on new flow passage liquid cooling plate. Chin. J. Power Sources 2020, 44, 1438–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Liu, N.H.; Gao, Q.; Yang, G.F. Cooling Performance Analysis and Structural Optimization of Concentric Structure Liquid Cooling Plate for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Xi’an Jiao Tong Univ. 2025, 3, 172–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.D.; Wang, C. Study on the Characteristics of Intercooling Plate for Automotive Power Battery. J. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2023, 6, 234–243. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).