Abstract

The Wiegand effect is a nonlinear magnetic phenomenon observed in specially processed Wiegand wires, representing a macroscopic manifestation of the Barkhausen effect. It is characterized by a large, sharp Barkhausen jump in the wire’s magnetization curve under an external alternating magnetic field. However, the underlying magnetic structure of these wires and the precise mechanism responsible for the Wiegand effect remain inadequately understood. In this study, we propose a conceptual model for the magnetic structure of Wiegand wires. Experimental samples with varying diameters were prepared through FeCl3 solution etching. The magnetic properties of individual layers within the wire were systematically investigated using the surface magneto-optic Kerr effect, Wiegand pulse measurements, and minor hysteresis loop analysis. By correlating these experimental results with JMAG simulations based on the proposed magnetic structure model, we elucidate the layer-by-layer magnetization reversal processes under alternating magnetic fields and clarify the fundamental mechanism that triggers the large Barkhausen jump.

1. Introduction

The Wiegand sensor is a unique self-powered magnetic sensor that operates based on the Wiegand effect. Its core structure consists of two key components: a specially processed ferromagnetic wire (Wiegand wire) and a pick-up coil wound around it. This sensor generates distinctive bipolar voltage pulses across the coil terminals upon each reversal of the external magnetic field’s polarity. A defining feature of these pulses is that their characteristic parameters—specifically amplitude and duration—remain highly consistent and are largely independent of the switching frequency of the driving magnetic field [1]. This frequency independence stems from controlled large Barkhausen jumps within the bistable magnetic domains of the specially treated wire, which is the fundamental mechanism enabling its self-powered operation [2]. These sensors are particularly valuable for energy harvesting in low-power systems, where they convert ambient magnetic energy (e.g., from rotating machinery or linear actuators) into electrical pulses to power wireless devices or extend battery life [3,4,5]. Furthermore, their predictable pulse output facilitates applications such as battery-less position sensing [6], self-powered activation of Hall sensors [2], and digital pulse counting in rotary encoders. Recent research advances focus on optimizing energy extraction circuits and enhancing integration with IoT modules. These developments position Wiegand technology as a cornerstone for maintenance-free sensing and micro-energy harvesting in industrial and embedded systems.

The Wiegand effect is a nonlinear and bistable magnetic phenomenon observed in Wiegand wires [7]. These wires are typically made of a ferromagnetic alloy, primarily consisting of iron, cobalt, and vanadium, which is considered one of the optimal materials for exhibiting this effect [8]. A specialized processing sequence involving annealing, torsion, and aging is employed to induce its characteristic bistable magnetic structure [9]. The influences of the wire’s length, annealing parameters, and torsional stress on its magnetic properties have been extensively investigated in Refs. [10,11].

The Wiegand wire is widely described as possessing a two-layer magnetic structure, comprising a magnetically soft outer layer and a hard inner core, which exhibit lower and higher coercivity, respectively [9]. It is noteworthy that the magnetic structure of Wiegand wires can vary depending on the alloy composition and processing history. While early patents and some implementations describe a structure with a magnetically soft core and a hard shell, the FeCoV wires used in this study, fabricated by torsional deformation and annealing, consistently exhibit an inverse profile characterized by a soft outer layer and a hard core, as confirmed by our prior research [2]. The soft layer is responsible for the rapid magnetization reversal that generates the large Barkhausen jump. In our previous work, we employed first-order reversal curve (FORC) analysis to characterize the coercivity distribution within Wiegand wires and to establish its correlation with the wire’s diameter and length [12]. However, this methodology alone remains insufficient to fully elucidate the precise magnetic configuration or the underlying physical mechanism responsible for the large Barkhausen jump.

The primary objective of this study is to systematically investigate the influence of diameter on the magnetization properties of Wiegand wires and to elucidate their precise internal magnetic structure, the interactions between different magnetic phases, and the magnetization dynamics underlying the large Barkhausen jump. By developing and validating a multi-layer simulation model, this work aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the magnetic behavior and intra-wire interactions. Ultimately, these insights are intended to advance the rational design and optimization of Wiegand-based devices for enhanced performance in sensing, energy harvesting, and magnetic switching applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

To investigate the magnetic structure of Wiegand wires in greater depth, this study utilized a set of five samples of identical length (13 mm) but with varying diameters: 0.23 mm (standard), 0.18 mm, 0.14 mm, 0.10 mm, and 0.06 mm. The Wiegand wire was made of a single material composed of Fe0.4Co0.5V0.1 (SWFE Corp., Ltd., Meishan, Sichuan, China), and the multilayered magnetic structure was achieved by torsional stress, annealing, and cold treating the wire. The sample preparation procedure is detailed as follows. Prior to etching, five segments of standard Wiegand wire with identical length (13 mm) and diameter (0.23 mm) were prepared by cutting from a longer wire. One segment was retained as the standard reference sample (0.23 mm). The remaining four segments were subjected to chemical etching simultaneously to achieve the target reduced diameters (0.18 mm, 0.14 mm, 0.10 mm, and 0.06 mm). The etching process was performed by horizontally immersing the wire segments in a ferric chloride (FeCl3) aqueous solution (Leagene Biotechnology Corp., Ltd., Beijing, China) with a molarity of 0.5 mol/L at room temperature (approximately 25 °C). The etching proceeded radially inward from the outer surface. During the process, the diameters of the wires were monitored intermittently using a micrometer screw gauge. Etching was paused for measurement, and the wires were returned to the solution until the desired diameters were attained. This chemical etching method is considered a material removal process that primarily reduces the wire’s cross-section without introducing significant thermal or mechanical alterations to the remaining core material, thereby preserving the internal mechanical stress state and intrinsic magnetic properties established by the original manufacturing processes (torsion, annealing, and cold treatment) of the wire. This assumption is supported by our prior work [12] which utilized a similar methodology.

2.2. Experimental Methods

To produce experimental samples with varying diameters, standard Wiegand wires were first etched using an FeCl3 solution. The surface magneto-optic Kerr effect (MOKE) was then employed to measure the surface magnetization curves of these etched wires. Comparative analysis of these curves indicated that the outermost layer plays a critical role in enabling the large Barkhausen jump. Subsequently, magnetization curves were derived from Wiegand pulse measurements in coil excitation mode. A comprehensive investigation of the magnetization reversal process and magnetic properties was conducted by comparing these curves across different wire diameters and analyzing minor hysteresis loops obtained using a vibrating sample magnetometer (model 8600 series, Lake Shore Cryotronics, Westerville, OH, USA).

In the final phase of the study, a five-layer magnetic structure model of the Wiegand wire was developed using the JMAG-Designer (JSOL Corp., Tokyo, Japan, ver. 20.0). This model facilitated a detailed elucidation of the magnetic structure, the magnetization reversal process, the internal magnetic interactions, and the fundamental mechanism responsible for large Barkhausen jumps. Through this multi-faceted analytical approach, deeper insights were gained into the magnetic characteristics of Wiegand wires, particularly regarding the influence of dimensional variations on their magnetic behavior.

2.2.1. Surface Magnetization Measured by MOKE

The MOKE is an essential experimental tool in surface magnetism and has been extensively applied to studies of magnetic anisotropy, interlayer coupling in multilayer films, and phase transitions in magnetic ultrathin films.

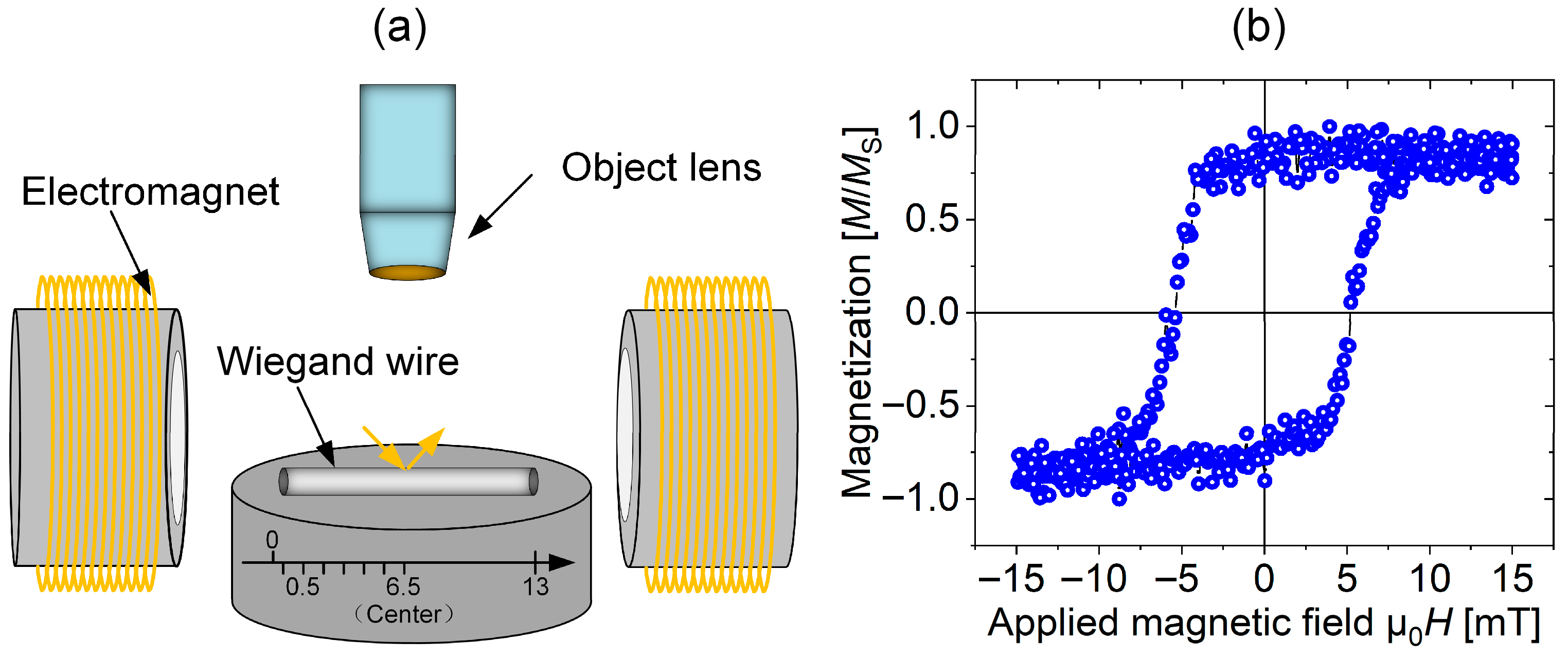

For the measurements, the Wiegand wire was aligned parallel to the applied magnetic field direction. This configuration ensures that the magnetization within the wire extends along its longitudinal axis, with the magnetization vector lying parallel to both the wire surface and the plane of incident light. A schematic of the measurement setup is shown in Figure 1a, and a representative magnetization curve obtained from a Wiegand wire is presented in Figure 1b. MOKE measurements on Wiegand wires of varying diameters were performed using a commercial instrument (Model BH-753, NEOARK CORPORATION, Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the MOKE measurement and typical magnetization curve of a Wiegand wire. (a) Experimental setup for MOKE measurements; (b) Representative magnetization curve of a standard Wiegand wire.

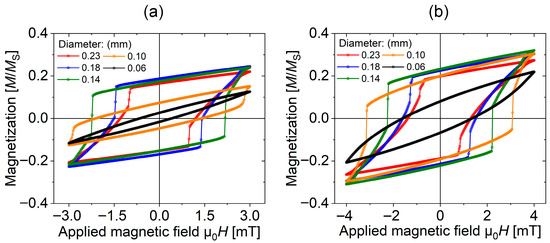

2.2.2. Minor Loops Measured by VSM

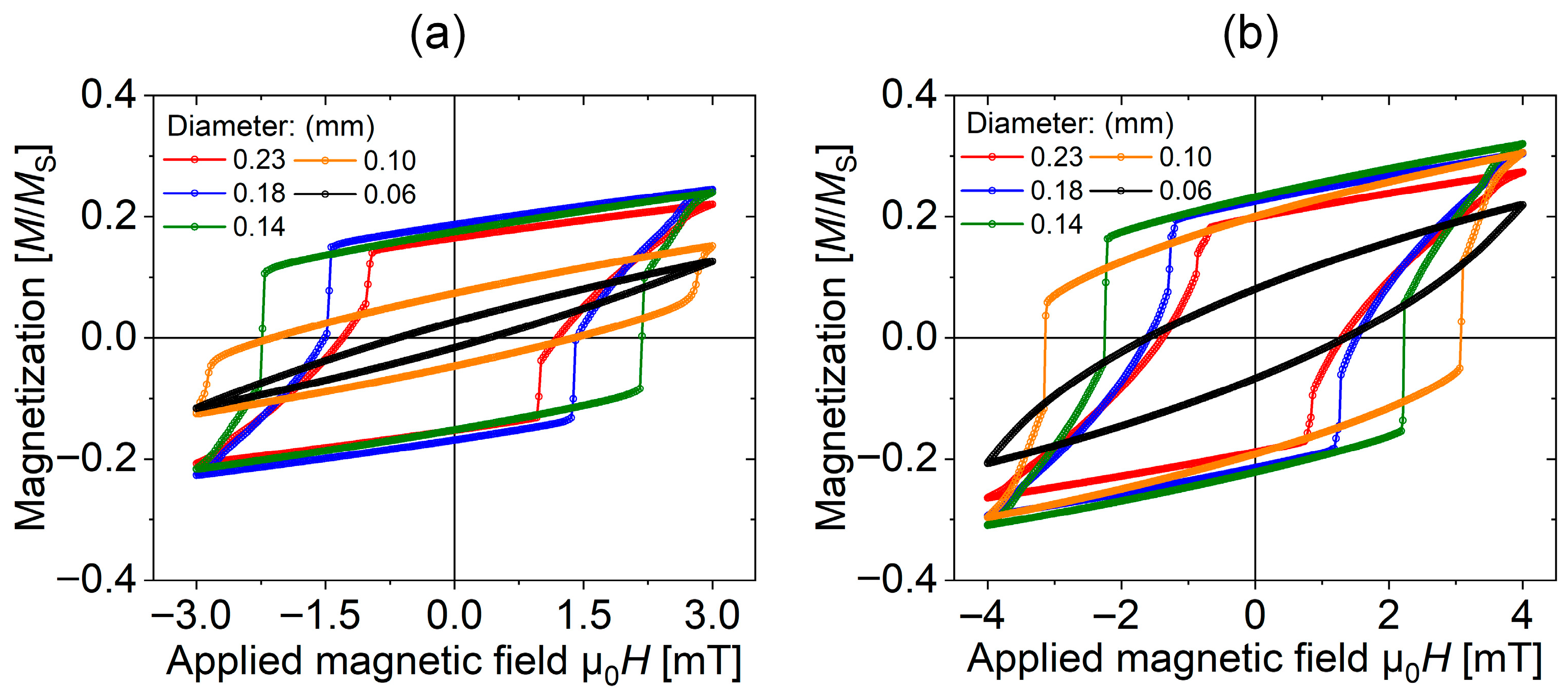

The VSM is widely employed for characterizing the magnetic properties of Wiegand wires. Using this technique, we measured minor hysteresis loops for five samples with identical lengths but varying diameters under alternating magnetic fields ranging from 3 to 15 mT. Representative measurement results obtained at 3 mT and 4 mT are presented in Figure 2. The partial hysteresis loops were measured starting from a demagnetized state. The presented data are background-corrected, and any high-field linear offsets were adjusted to ensure the saturated magnetization regions were symmetric, reflecting the intrinsic magnetic response of the wire without mathematical symmetrization of the loop shape.

Figure 2.

Minor hysteresis loops of Wiegand wires (length: 13 mm) with varying diameters measured at different applied magnetic field strengths: (a) μ0H = 3 mT; (b) μ0H = 4 mT.

Notable discrepancies were observed in the minor hysteresis loops of Wiegand wires with different diameters under identical applied magnetic fields. Some loops exhibited a significant Barkhausen jump, while others did not display this characteristic. Furthermore, wires of the same diameter showed substantial variations when subjected to different magnetic field strengths. The observed increase in the Barkhausen jump amplitude with reduced wire diameter is consistent with the magnetic locking model. As etching creates a harder effective core with higher average coercivity, a greater external field is required to trigger the unlocking event. This allows more magnetostatic energy to be stored in the interlayer coupling, resulting in a larger release of flux upon its collapse, as simulated in Section 3.3. These variations in magnetization states and the interlayer interactions within the magnetic structure of Wiegand wires will be further discussed in Section 3.

2.2.3. Minor Loops Calculated by Wiegand Pulses

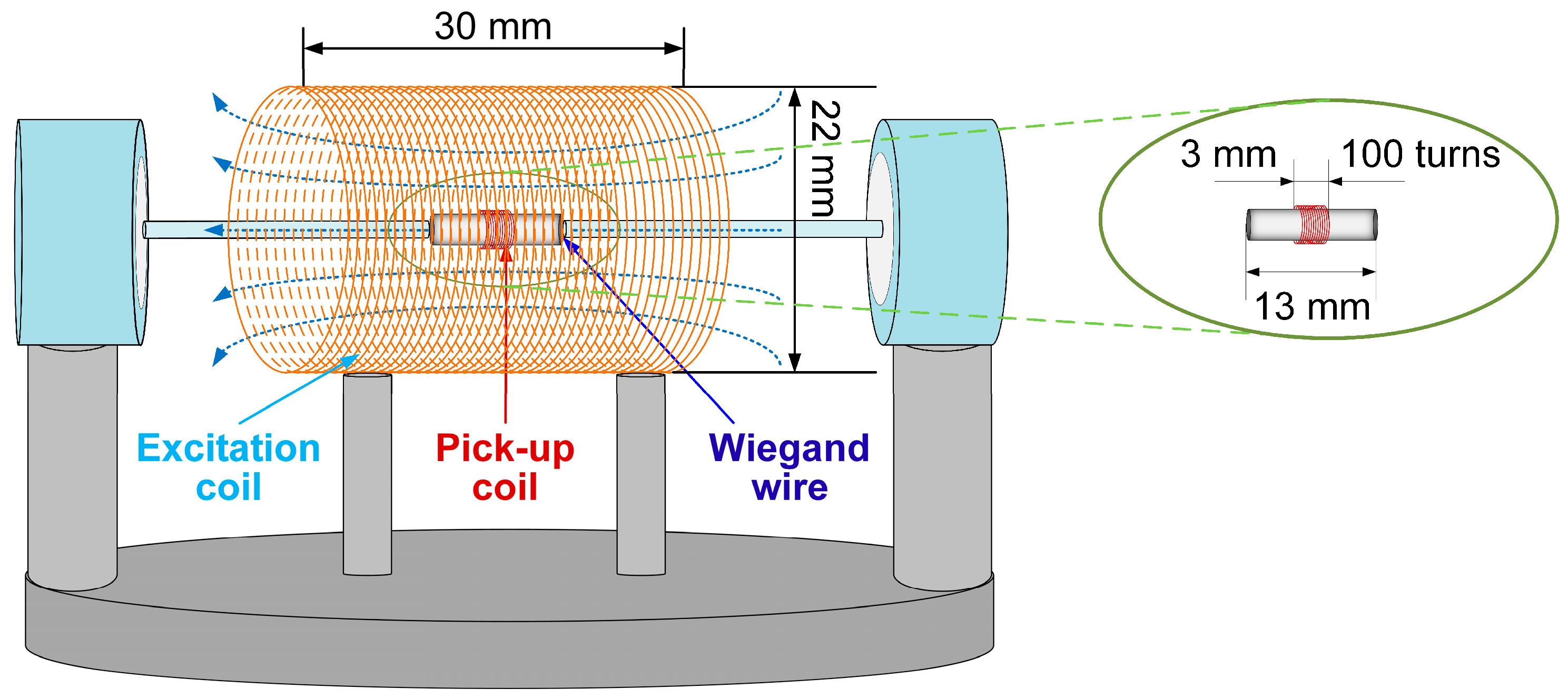

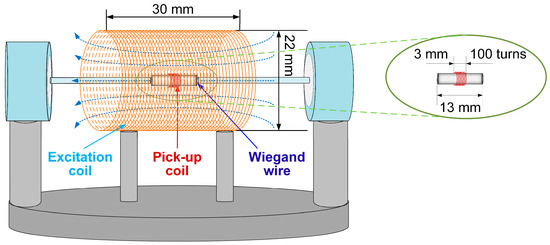

In the excitation coil experiment, a constant-frequency alternating current was applied to generate an alternating magnetic field along the excitation coil axis, as illustrated in Figure 3. The instantaneous magnetic field strength is directly proportional to the current supplied to the excitation coil, as described by Equation (1):

where H(t) is the instantaneous magnetic field strength within the excitation coil (A/m). k is the number of turns per unit length of the excitation coil (m−1). I(t) is the instantaneous current flowing through the excitation coil winding (A). By varying the input current to the excitation coil, the strength of the applied magnetic field could be precisely controlled.

Figure 3.

Schematic of excitation coil induces voltage pulses from Wiegand sensor.

The Wiegand wire, with the pick-up coil wound around it, was positioned at the center of the excitation coil’s axis. The Wiegand wire measured 13 mm in length, and the pick-up coil, consisting of 100 turns, was wound around its central section. The output voltage v(t) induced across the pick-up coil is determined by the number of turns N and the rate of change of magnetic flux dΦ/dt through the pick-up coil, as expressed in Equation (2):

The magnetic flux Φ(t) linking the pick-up coil is proportional to the magnetic flux density B(t) and the cross-sectional area S of the pick-up coil, as given by Equation (3):

According to (2) and (3), when a Wiegand pulse is generated, the magnetic flux density B(t) in the pick-up coil exhibits a proportional relationship with the time integral of the output voltage across the coil, as expressed in Equation (4):

It is established that the magnetization M(t) of a material is defined as the difference between the total magnetic flux density B(t) and the contribution of the external magnetic field H(t), with their relationship given by Equation (5). where μ0 is the permeability of free space.

During the experimental measurements, the frequency of the AC current supplied to the excitation coil was set to 20 Hz. The inner diameter of the pick-up coil matched that of the Wiegand wire at approximately 0.23 mm. Given the small cross-sectional area of the pick-up coil and the low frequency of the excitation field, the induced voltage due to mutual inductance between the excitation and pick-up coils was considered negligible compared to the Wiegand pulse voltage. The configuration of the experimental measurement system is illustrated in Figure 3.

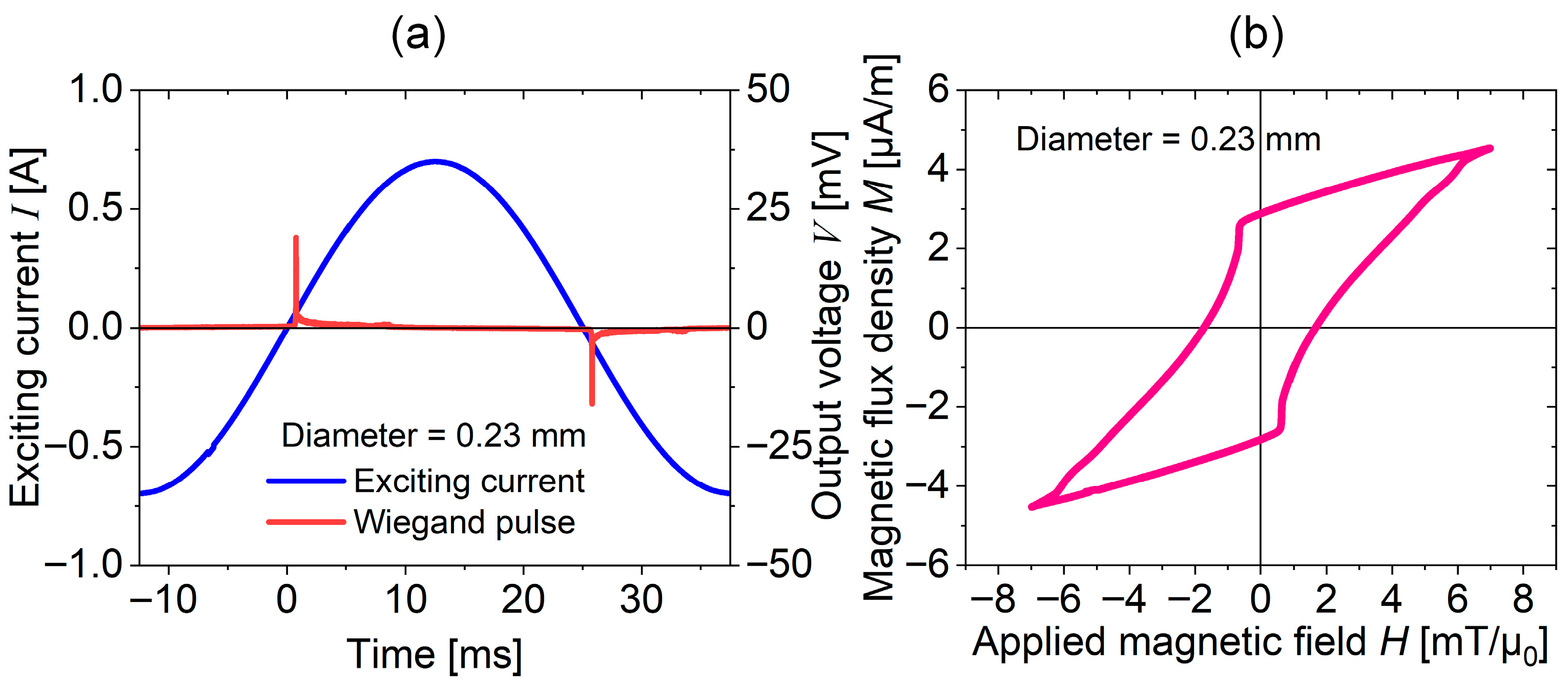

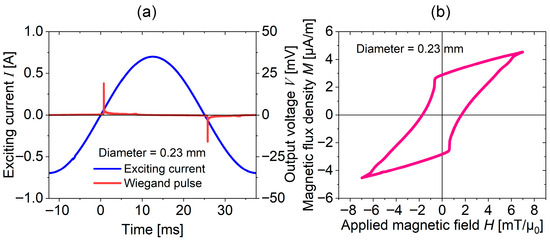

For instance, a sinusoidal AC current with a peak amplitude of 0.7 A was applied to the excitation coil. A dual-channel oscilloscope was employed to simultaneously monitor and record both the current waveform in the excitation coil and the output Wiegand pulse from the pick-up coil, as shown in Figure 4a. Using Equations (1) and (5), we were able to calculate the M-H curve representing the relationship between magnetization and applied magnetic field strength. The resulting magnetization curve of the Wiegand wires, obtained under excitation with a maximum magnetic field strength of 7 mT, is presented in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

Derivation of magnetization curve from Wiegand pulse measurements. (a) Waveforms of excitation coil current and corresponding output Wiegand pulse from the pick-up coil; (b) M-H magnetization curve calculated from Wiegand pulse data.

3. Results and Discussion

In this study, MOKE measurements were performed by applying an alternating magnetic field to the Wiegand wires. The applied magnetic field frequency was set to 0.1 Hz with a strength ranging from 3 to 15 mT. For each wire, the measurement point was carefully selected at the center along its axial direction. VSM measurements were conducted to characterize the minor hysteresis loops of Wiegand wires with different diameters under applied magnetic fields ranging from 3 to 15 mT. In the excitation coil experiments, the excitation coil was driven by an alternating current at 20 Hz. The strength of the applied magnetic field was adjusted by varying the current amplitude in the excitation coil. The Wiegand wire, wound with a pick-up coil, was positioned at the center of the excitation coil axis. The input current to the excitation coil and the output voltage from the pick-up coil were simultaneously measured using a dual-channel oscilloscope. Following the methodology described in Section 2.2.3, the magnetization curves of the Wiegand wire under different magnetic field strengths were subsequently calculated.

3.1. Magnetization Curves

The three aforementioned techniques for characterizing the magnetization properties of Wiegand wires differ fundamentally in their underlying operating principles:

The MOKE detects changes in the polarization state (Kerr rotation angle and ellipticity) of linearly polarized light reflected from the wire surface, enabling characterization of the near-surface magnetization state. This technique provides sensitive detection of surface domain structures and dynamic magnetic behavior in Wiegand wires [13].

The VSM measures voltage signals induced in detection coils as the sample undergoes mechanical vibration under an applied magnetic field. Utilizing lock-in amplification techniques, it precisely determines material hysteresis loops, making it particularly suitable for analyzing the stepped magnetization reversal behavior associated with the bistable magnetic structure of Wiegand wires. This method effectively characterizes the large Barkhausen jump phenomena arising from the hard/soft magnetic composite architecture.

The excitation coil method detects Wiegand pulses induced in a pick-up coil through rapid flux changes (dΦ/dt) generated by large Barkhausen jumps. This approach directly probes the microscopic dynamics of domain wall pinning–depinning processes. The underlying physical mechanism involves the nonlinear breakdown of pinning potentials at hard/soft magnetic interfaces, revealing the discrete nature of irreversible domain wall motion during magnetization reversal.

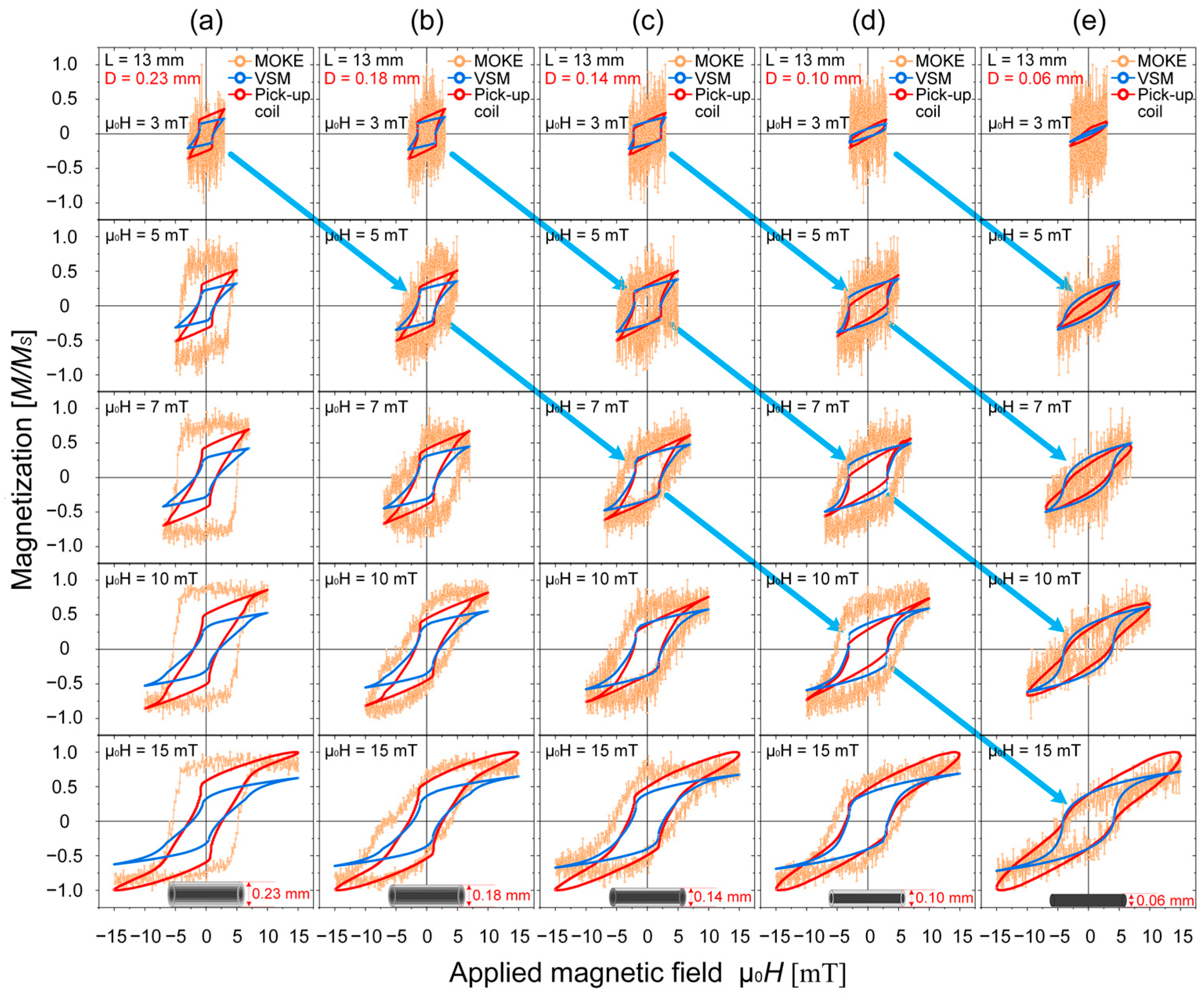

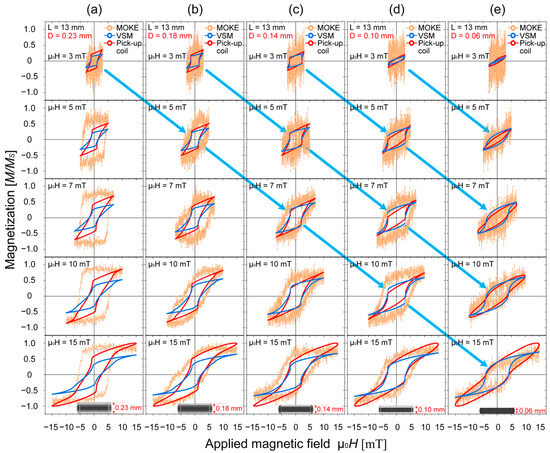

The fundamental differences in the measurement principles of the three aforementioned techniques result in distinctive magnetization curves for the Wiegand wire, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Comparison of magnetization curves for Wiegand wires with different diameters measured using three techniques: MOKE, VSM, and excitation coil methods. (a) Diameter is 0.23 mm; (b) Diameter is 0.18 mm; (c) Diameter is 0.14 mm; (d) Diameter is 0.10 mm; (e) Diameter is 0.06 mm.

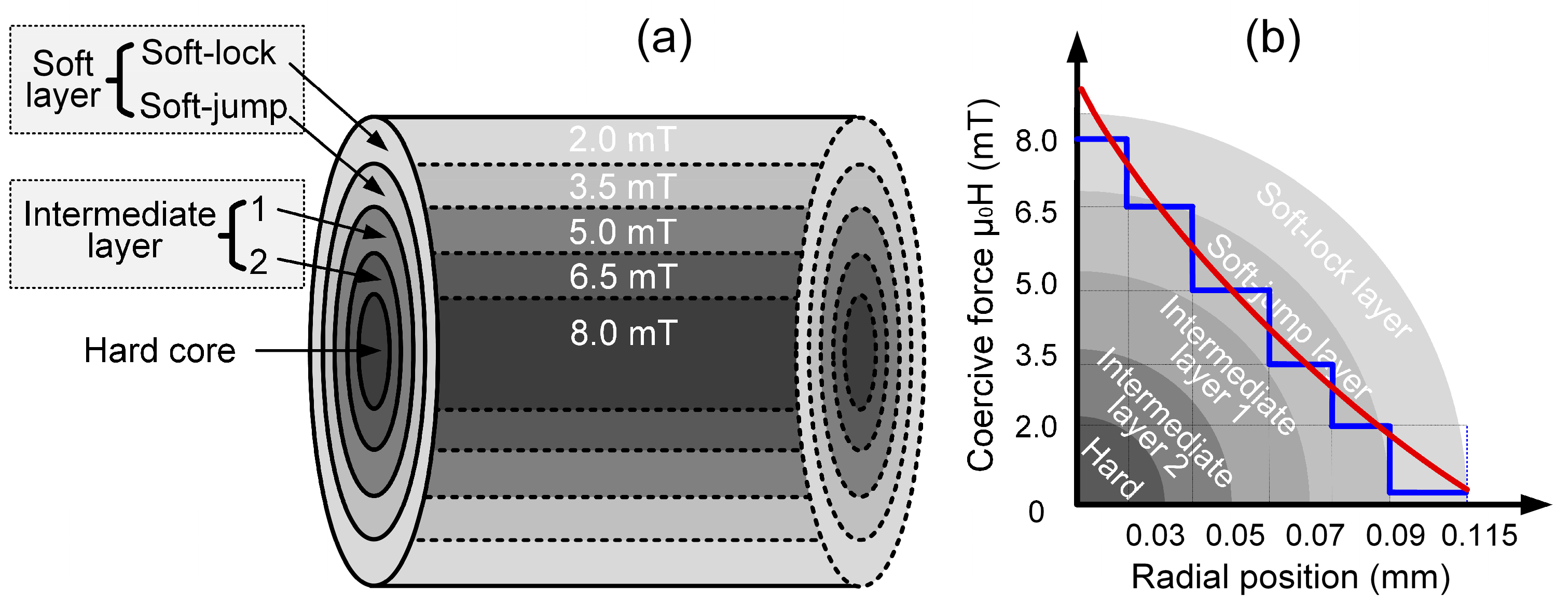

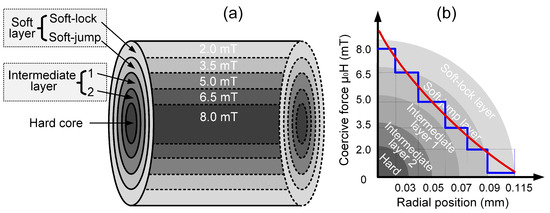

In our previous studies, we utilized First-Order Reversal Curves (FORCs) analysis and FORC diagrams to investigate the coercivity distribution and magnetic structure of Wiegand wires, establishing the absence of a distinct boundary between the soft and hard magnetic phases while demonstrating a radially graded, continuously increasing coercivity distribution from surface to core [12]. To further elucidate the mechanism responsible for large Barkhausen jumps in Wiegand wires, the present study utilizes samples with systematically varying diameters to propose a novel five-layer magnetic structure model with corresponding coercivity distribution. This model architecture, shown schematically in Figure 6, consists of the following layers arranged sequentially from the surface inward: soft-lock layer, soft-jump layer, intermediate-1 layer, intermediate-2 layer, and hard core.

Figure 6.

Proposed magnetic structure model and coercivity distribution of Wiegand wire. (a) Schematic of the five-layer magnetic structure; (b) Corresponding coercivity distribution profile.

The original Wiegand wire sample has a diameter of 0.23 mm. As successive etching removes the outer layers, the diameter decreases correspondingly: when the diameter is reduced to 0.18 mm, the Soft-jump layer becomes exposed; at 0.14 mm, the Intermediate-1 layer is revealed; at 0.10 mm, the Intermediate-2 layer is reached; and at 0.06 mm, only the Hard core remains present.

For the unetched 0.23 mm sample (possessing the complete five-layer structure), the three measurement methods reveal substantial differences, as shown in Figure 5a.

The magnetization curve obtained by MOKE measurements exhibits sharp, large Barkhausen jumps in applied magnetic fields of 5–15 mT. These jumps correspond to rapid magnetization reversal in the soft-lock layer at the Wiegand wire surface and abrupt transitions in the magnetic domain structure.

When a maximum applied field of 3 mT was used, the minor hysteresis loop measured by VSM shows distinct large Barkhausen jumps. The switching field for this jump was measured at approximately 0.8 mT. which are attributed to the outermost soft-lock layer of the Wiegand wire. This layer has a coercivity of approximately 2 mT, meaning that an external maximum applied field of 3 mT is sufficient to induce rapid magnetization reversal. This process leads to the formation of magnetic locking coupling with the underlying soft transition layer, followed by sudden collapse of this magnetic lock.

The magnetization curve derived from Wiegand pulse measurements also exhibits large Barkhausen jumps when external maximum applied field was 3 mT. These jumps result from abrupt magnetic flux changes caused by rapid magnetization reversal in the soft-lock layer, followed by the formation and subsequent sudden collapse of magnetic locking coupling with the soft-jump layer. This behavior corresponds well with the characteristic voltage pulses detected by the pick-up coils.

As the outer layers of the Wiegand wire are progressively etched away and the diameter decreases, the resulting evolution of the magnetic structure significantly influences the measurement outcomes, as demonstrated in Figure 5b–e. Figure 5b displays the magnetization curves of the 0.18 mm sample. In comparison with Figure 5a, these curves resemble those of the unetched 0.23 mm sample, except that no distinct large Barkhausen jumps are detected in the MOKE-measured magnetization curve. Notably, pronounced large Barkhausen jumps are observed at 3 mT and 5 mT in both the minor hysteresis loop measured by VSM and the magnetization curve derived from Wiegand pulse measurements.

This phenomenon occurs because the outermost layer—specifically, the soft-lock layer of the original Wiegand wire—has been etched away, which alters the magnetic structure. The newly exposed surface layer (formerly the soft-jump layer) exhibits a coercivity of approximately 3.5 mT, requiring stronger external magnetic fields to undergo rapid magnetization reversal. Following this reversal, it forms magnetic locking coupling with the adjacent Intermediate-1 layer.

This magnetic locking coupling builds up energy as it resists the external magnetic field until the applied field strength becomes sufficient to overcome the pinning potential. The subsequent sudden collapse of this coupling releases the stored magnetostatic energy and triggers two simultaneous phenomena:

- Rapid magnetization reversal within the Intermediate-1 layer, resulting in large Barkhausen jumps observable in VSM-measured minor hysteresis loops;

- Abrupt changes in magnetic flux around the wire, which induce characteristic Wiegand voltage pulses in the pick-up coils.

Figure 5c,d present the magnetization curves for the 0.14 mm and 0.10 mm samples, respectively. Distinct large Barkhausen jumps are observed at 3 mT, 5 mT, 7 mT, and 10 mT in both the minor hysteresis loops measured by VSM and the magnetization curves derived from Wiegand pulse measurements. This behavior follows a mechanism similar to that observed in the 0.18 mm sample, which exhibited jumps at 3 mT and 5 mT, but requires stronger external magnetic fields to induce these jumps due to the higher coercivity of the newly exposed surface layers in the progressively etched samples.

Figure 5e presents the magnetization curves of the 0.06 mm sample (hard core only). Based on our previous FORC analysis of these differentially etched samples [12], the 0.06 mm specimen is confirmed to have all outer layers removed, retaining only the hard magnetic core. The MOKE-measured magnetization curves show nearly complete overlap, demonstrating the homogenization of the surface magnetic structure after removal of the layered architecture.

Due to the absence of both the outer soft layers and intermediate transition layers, the formation of magnetic locking coupling under external fields is precluded, and interlayer magnetic interactions are eliminated. The monolithic hard magnetic core undergoes magnetization reversal solely in response to external field variations. Consequently, no large Barkhausen jumps are observed in either the minor hysteresis loops measured by VSM or the magnetization curves derived from Wiegand pulse measurements. However, the VSM minor loop still reveals small-scale jumps, suggesting possible nanoscale magnetic domain reorganization within the hard core.

The higher apparent switching field observed via MOKE for the 0.23 mm wire, compared to VSM and coil measurements, resolves the distinction between the initial onset of reversal and the large Barkhausen jump. VSM and coil detect the early, gradual onset of reversal in the soft-lock layer. In contrast, MOKE specifically captures the later, abrupt collapse of the magnetic lock between the soft-lock and soft-jump layers, which triggers the rapid, collective reversal of the soft-jump layer and constitutes the large jump itself, occurring at a higher critical field as predicted by the simulation.

Based on a comparative analysis of the experimental results, we conclude that the formation and subsequent abrupt collapse of magnetic locking coupling between the outermost layer and adjacent layers is the fundamental mechanism responsible for large Barkhausen jumps in Wiegand wires. Essentially, the multilayered magnetic architecture of Wiegand wires is crucial for generating these pronounced jumps. Experimental samples with monolithic magnetic structures lack this characteristic layered configuration and consequently fail to produce large Barkhausen jumps. This explanation accounts for why such jumps are observed in Figure 5c,d but are absent in Figure 5e.

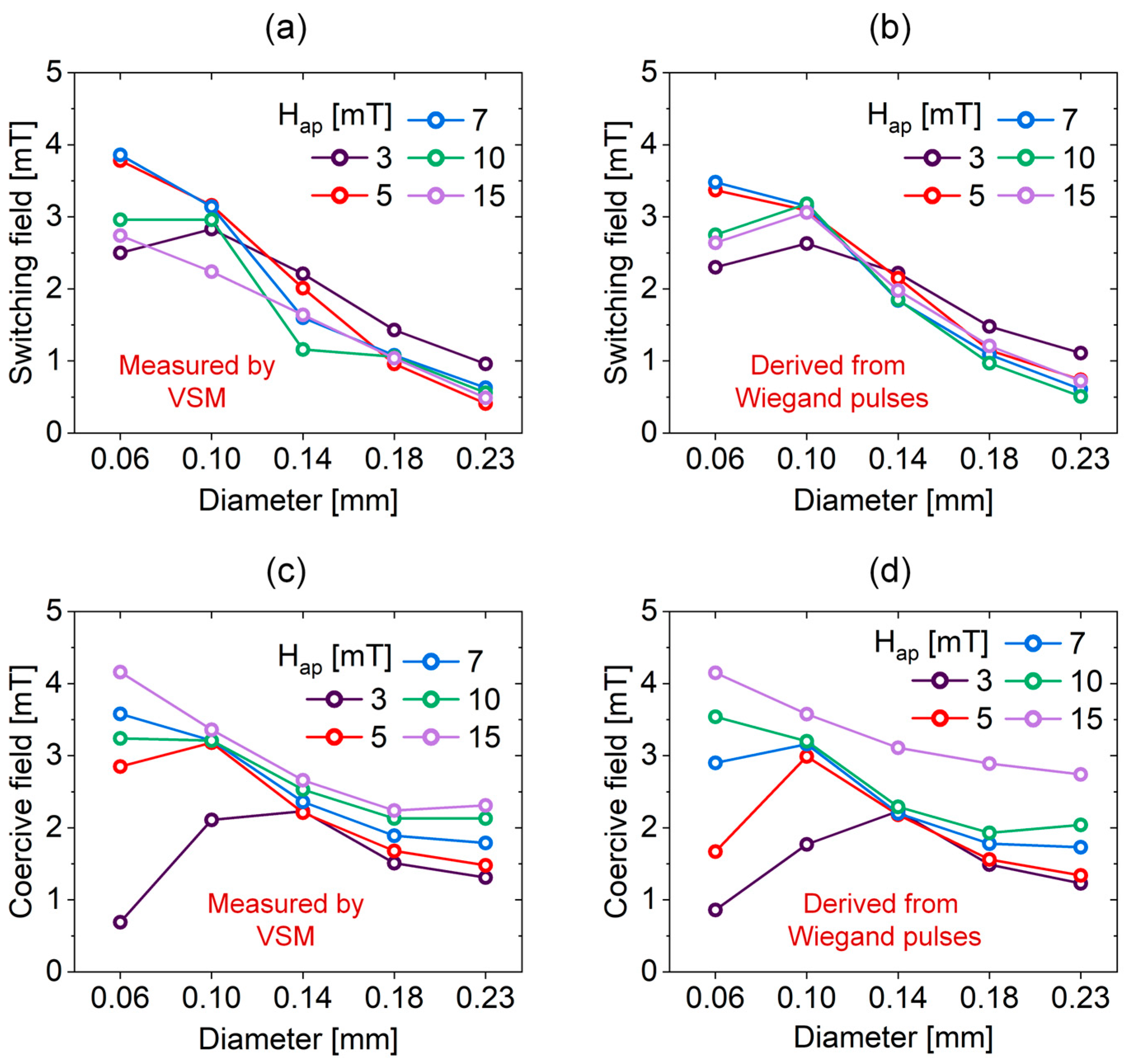

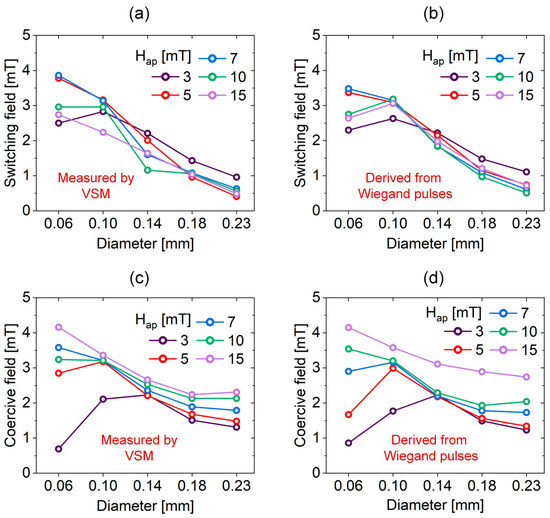

3.2. Switching Fields and Coercive Fields

We further performed statistical analysis of switching fields and coercive fields for differentially etched Wiegand wire samples using data obtained from both VSM-measured minor hysteresis loops and Wiegand pulse-derived magnetization curves, as summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Statistical analysis of switching fields and coercive fields for Wiegand wire samples with different diameters. (a) Switching fields obtained from VSM measurements; (b) Switching fields derived from Wiegand pulse measurements; (c) Coercive fields obtained from VSM measurements; (d) Coercive fields derived from Wiegand pulse measurements.

The switching field is defined as the magnetic field strength at which large Barkhausen jumps initiate during the magnetization reversal process after crossing the origin. The coercive field corresponds to the magnetic field strength at which the net magnetization of the sample reaches zero during the reverse field sweep after crossing the origin.

Our analysis reveals a significant inverse correlation between sample diameter and magnetic threshold parameters: reduced diameters correspond to systematically increased switching and coercive fields. These findings provide conclusive validation of the hypothesized radially graded coercivity distribution in Wiegand wires—demonstrating a progressive enhancement of coercivity from the surface layers toward the core region. This gradient-modulated coercivity profile represents both a fundamental magnetic characteristic unique to Wiegand wires and the essential mechanism enabling large Barkhausen jumps.

The divergent behavior observed via MOKE is not contradictory but highly instructive, as it underscores the radial inhomogeneity of the magnetic structure in our wires. As established, our Wiegand wires possess a soft magnetic outer layer. MOKE probes only the magnetization dynamics within the optical penetration depth (tens of nanometers) of this surface. For the standard 0.23 mm wire, the intact soft outer layer hosts the large Barkhausen jump, which dominates the MOKE signal and results in a high, sharp switching field. For the etched wires (0.18–0.06 mm), the chemical etching has progressively removed this specific soft outer layer responsible for the surface jump. Consequently, the MOKE signal from the etched surface originates from underlying magnetic layers with different reversal characteristics, leading to smaller, more gradual loops and an apparently lower coercive field.

3.3. Simulation Model and Simulation Results

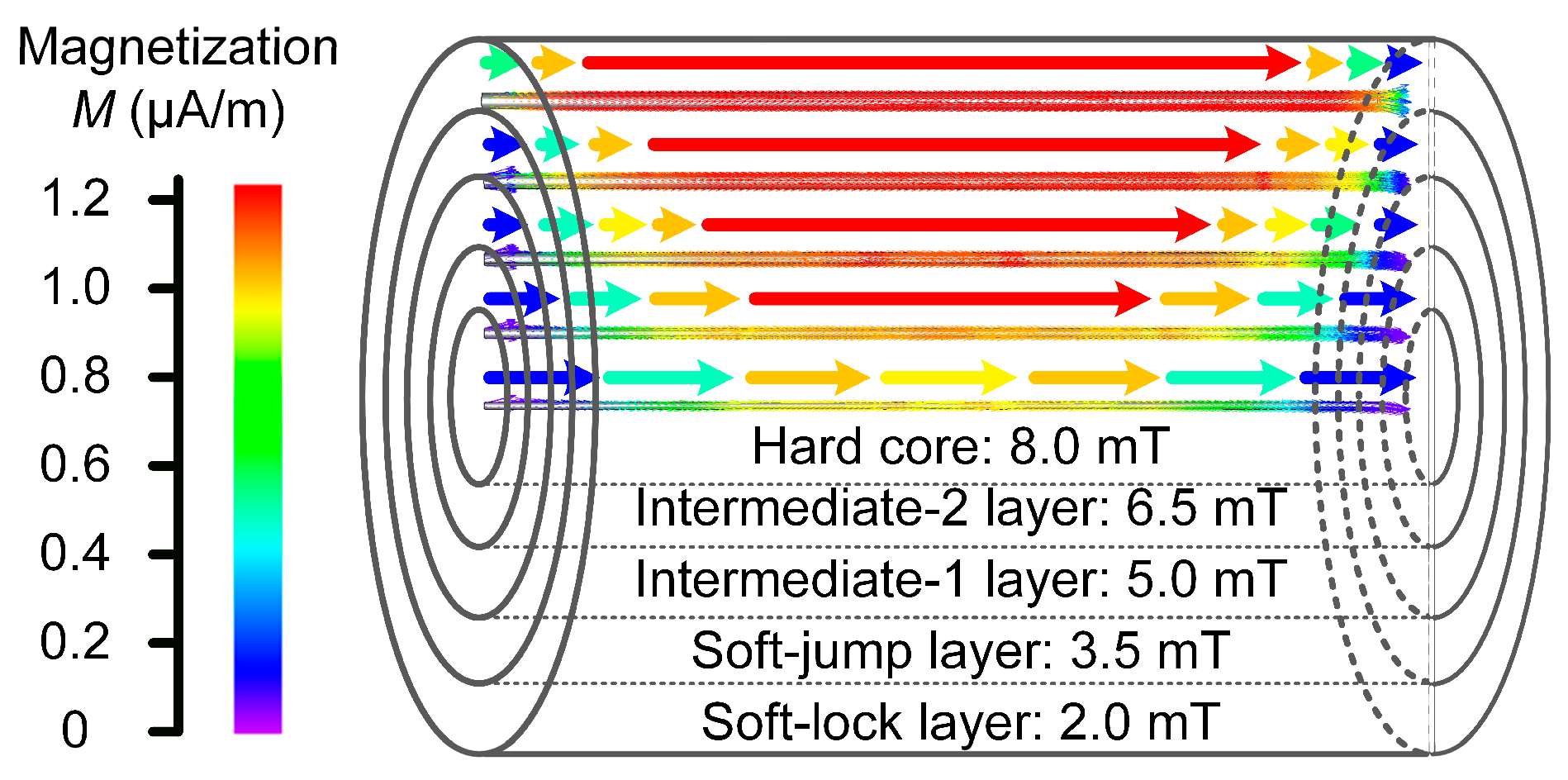

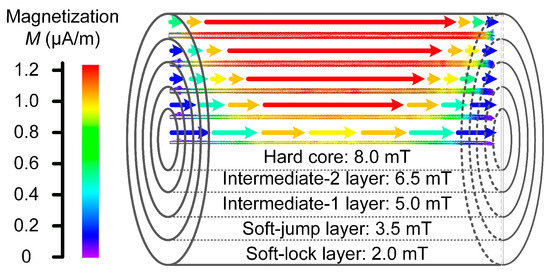

A simulation model was developed using JMAG-Designer (JSOL Corp., Tokyo, Japan, ver. 20.0). The simulation model was designed with five concentric layers of equal radial thickness, maintaining the actual external dimensions of a standard Wiegand wire (length: 13 mm; diameter: 0.23 mm). The coercivity values for the five layers, from outermost to innermost, were set to 2 mT/μ0, 3.5 mT/μ0, 5 mT/μ0, 6.5 mT/μ0, and 8 mT/μ0, respectively, to represent a continuous radially increasing coercivity profile. Note that due to the cylindrical geometry, the layers have different volumes. The subsequent analysis of simulated magnetization patterns and reversal sequences focuses on the interplay between the set coercivity gradient and interlayer magnetostatic coupling, which governs the observed phenomena (e.g., cascading unlock), rather than treating them as a simple consequence of volume-weighted magnetic moment dominance. Due to the axial symmetry of the Wiegand wire, the simulation displays the magnetization state of each layer using only the upper half of the cross-section, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Simulation model created by JMAG-Designer.

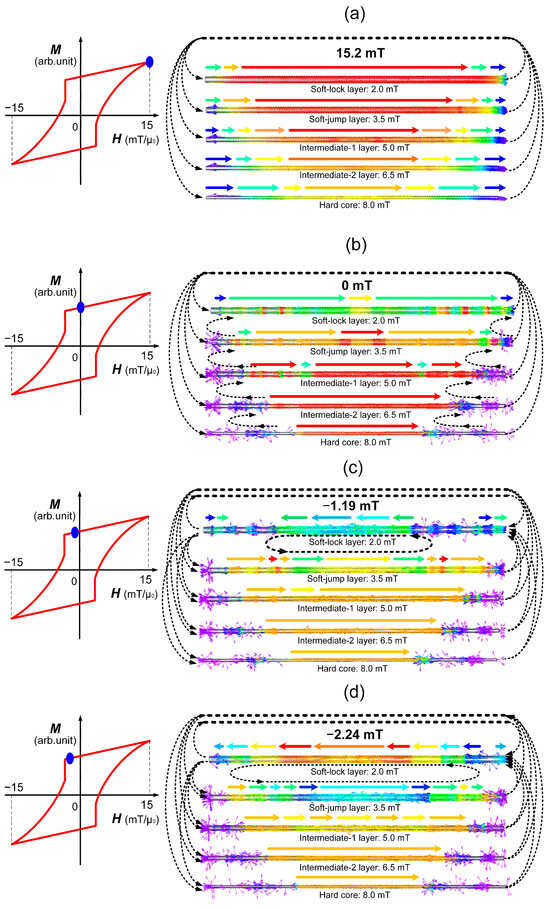

The simulation of the proposed five-layer magnetic structure model of the Wiegand wire, conducted at varying applied magnetic field strengths, begins by demagnetizing the model before applying an initial 15 mT magnetic field. After reaching stabilization, the magnetization state of each layer exhibits its simplest form, with uniform magnetization direction throughout. The outermost soft-lock layer, possessing the lowest coercivity, demonstrates the strongest magnetization intensity, which becomes progressively weaker in inner layers with higher coercivity values. Due to demagnetization field effects and static magnetic coupling interactions, weaker magnetization is observed at the ends of the model, particularly more pronounced near the core layer region, as shown in Figure 9a.

Figure 9.

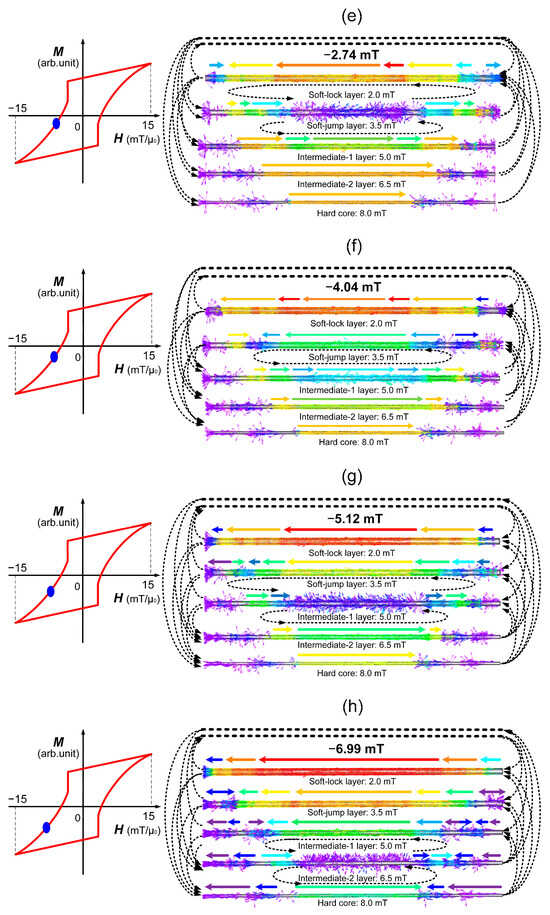

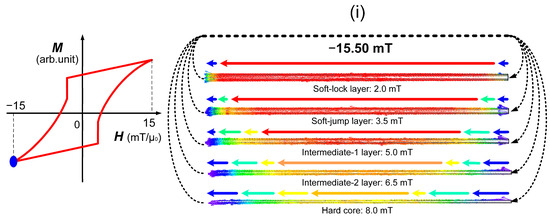

Simulated magnetization states of different layers in the five-layer model at various applied magnetic field strengths. (a) μ0H = 15.2 mT; (b) μ0H = 0 mT; (c) μ0H = −1.19 mT; (d) μ0H = −2.24 mT; (e) μ0H = −2.74 mT; (f) μ0H = −4.04 mT; (g) μ0H = −5.12 mT; (h) μ0H = −6.99 mT; (i) μ0H = −15.5 mT.

When the applied magnetic field is reduced to 0 mT, the magnetization direction of each layer remains unchanged. The soft-lock and soft-jump layers, characterized by lower coercivity, exhibit a significant reduction in magnetization intensity. In contrast, the intermediate layers and hard core show increased magnetization due to the influence of the soft-layer magnetization. As the simulation proceeds, the magnetization distribution begins to exhibit increasing disorder, particularly in regions adjacent to the higher-coercivity core layer. This phenomenon is attributed to the combined effects of the demagnetization field and static magnetic coupling between layers, as illustrated in Figure 9b. Note that the simulated continuous decrease in magnetization magnitude within a layer is a distributed relaxation process, which is typically not resolved as a discrete feature in spatially averaged surface measurements like MOKE.

When the applied magnetic field is reduced to 0 mT and then a reverse magnetic field is gradually increased, a decrease in magnetization is observed throughout the entire model at −1.19 mT. At this field strength, the outermost soft-lock layer begins to reverse its magnetization direction. Partial magnetization reversal is also observed at the ends of the other layers due to demagnetization field effects and magnetostatic coupling interactions. As a result, the soft-lock and soft-jump layers become magnetically anti-parallel, forming a stable magnetic lock through magnetostatic coupling, as demonstrated in Figure 9c.

In the simulation model, as the external magnetic field strength increases, the magnetization of the outermost soft-lock layer correspondingly rises. This leads to a progressive strengthening of the magnetic locking coupling between the soft-lock and soft-jump layers, as demonstrated in Figure 9d.

Simultaneously, the energy barrier for magnetization reversal in the soft-jump layer increases, creating a competitive interplay between these two opposing forces. When the reverse magnetic field strength reaches −2.74 mT, significant magnetization reversal occurs in the central region of the soft-jump layer, as shown in Figure 9e.

The collapse of magnetic locking coupling between the soft-lock and soft-jump layers triggers the rapid reversal of magnetization in the soft-jump layer, resulting in the large Barkhausen jump observed in the Wiegand wire. This simulation result corresponds closely with our experimental measurements of leakage magnetic flux density in a standard 0.23 mm diameter Wiegand wire, where complete magnetization reversal occurred at an external magnetic field of −3 mT under identical experimental conditions.

Furthermore, when the magnetic field strength reaches −4.04 mT, the soft-jump layer completes its magnetization reversal and establishes a new magnetic locking coupling with the intermediate-1 layer, as shown in Figure 9f. As the magnetic field strength continues to increase, this magnetic locking coupling progressively strengthens.

At a field strength of −5.12 mT, the magnetic locking coupling between the soft-jump and intermediate-1 layers collapses, leading to the establishment of a new magnetic locking coupling between the intermediate-1 and intermediate-2 layers, as shown in Figure 9g. With further increase in magnetic field strength to −6.99 mT, this newly formed magnetic lock between the intermediate-1 and intermediate-2 layers also collapses, simultaneously resulting in the formation of a new magnetic locking coupling between the intermediate-2 layer and the hard core, as demonstrated in Figure 9h.

Finally, when the applied magnetic field reaches the same magnitude but in the opposite direction to the initial applied magnetic field, the magnetization state of the simulated model closely resembles the initial configuration, though with the magnetization of each layer reversed in direction, as presented in Figure 9i.

The JMAG simulation of the Wiegand wire’s five-layer magnetic structure fundamentally reveals that large Barkhausen jumps originate from the synchronized collapse of interfacial magnetic locking coupling between layers, rather than from independent magnetization reversal within individual layers. Specifically, the abrupt rupture of magnetostatic coupling between the soft-lock and soft-jump layers at −2.74 mT triggers rapid magnetization reversal in the soft-jump layer, generating the characteristic jump—a finding consistent with experimental observations at −3 mT in 0.23 mm diameter wires. This process initiates a cascade of energy transfer: each coupling collapse (e.g., between soft-jump and intermediate-1 layers at −5.12 mT, and between intermediate-1 and intermediate-2 layers at −6.99 mT) releases stored magnetostatic energy, propagating the reversal process inward while simultaneously establishing new locking coupling with deeper layers. Crucially, the radially graded coercivity profile (2–8 mT/μ0) enables this sequential establishment and rupture of magnetic locking coupling, demonstrating that interlayer magnetostatic interactions—rather than isolated soft-layer dynamics—govern the Wiegand effect.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes that large Barkhausen jumps in Wiegand wires originate fundamentally from the synchronized collapse of interfacial magnetic locking couplings within their graded multilayer structure. Through controlled etching experiments and multi-method characterization (LMOKE/VSM/Wiegand pulse), we validated the following key findings:

- Layer-Dependent Dynamics: Etched samples (0.18–0.10 mm diameter) exhibited large Barkhausen jumps at elevated magnetic fields (3–10 mT), directly correlating with the coercivities of the newly exposed layers. The absence of these jumps in monolithic hard cores (0.06 mm diameter) confirms that multilayer magnetic interactions are essential for the phenomenon.

- Magnetic Locking Mechanism: JMAG simulations reveal that sequential magnetization reversal begins at −1.19 mT in the soft-lock layer, forming anti-parallel locking configurations with adjacent layers. Critical collapse of these magnetic locks triggers abrupt jumps (as demonstrated by soft-jump layer reversal at −2.74 mT), while cascading energy transfer propagates reversal inward through intermediate layer unlocking events at −5.12 mT and −6.99 mT.

- Experimental-Simulation Consistency: The simulated jump at −2.74 mT corresponds closely with experimental observations at −3 mT in 0.23 mm Wiegand wires (error < 8.7%), confirming that interfacial lock collapse constitutes the fundamental origin of the large Barkhausen jump.

In summary, the large Barkhausen jump is not an intrinsic property of any individual layer but emerges from the architecture of the system. It is specifically initiated by the sudden collapse of magnetostatic locking between the soft-lock and soft-jump layers. While a cascade of unlocking events propagates reversal inward, the initial jump is the most pronounced because it involves the coupled reversal of the largest volume of soft material against the steepest coercivity gradient. The absence of this jump in the monolithic 0.06 mm core (Figure 2) provides direct experimental proof that the phenomenon requires a coupled multilayer structure.

These findings demonstrate that the Wiegand effect stems from the synergistic interplay between the material’s layered architecture, gradient-distributed coercivity, and the abrupt collapse of magnetic locking coupling between the outermost layer and its adjacent layer. This mechanistic understanding provides a solid foundation for optimizing the design of magnetic sensors based on the Wiegand effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T. and G.S.; measurement, G.S., L.J., C.Y. and Z.S.; analysis, Y.T., G.S., L.J., C.Y. and Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.T., G.S. and C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Start-up Fund for New Talented Researchers of Nanjing University of Industry Technology (Grant No. YK24-04-07) and 2024 “Qing Lan Project” for Excellent Young Core Teachers of Jiangsu Province (2024-02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Part of the research content in this paper is derived from the author’s doctoral dissertation entitled “Magnetic structure and fast magnetization reversal of Wiegand wire elucidated by external magnetic field measurement” (Graduate School of Engineering Science, Yokohama National University, 2024). The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Yasushi Takemura, the supervisor during the doctoral period, for his careful guidance, generous support, and valuable suggestions throughout the research process, which laid a solid foundation for this research. Meanwhile, thanks are extended to Hiroki Shigeta of the Takemura Laboratory at Yokohama National University for his valuable assistance with the JMAG simulations conducted in this study. His expertise and support in generating and interpreting the simulation results were greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Products Wiegand Sensor, POSITAL. Available online: https://www.posital.com/en/products/wiegand-sensors/wiegand-integrated-sensing-harvesting.php (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Takemura, Y.; Fujiyama, N.; Takebuchi, A.; Yamada, T. Battery-less hall sensor operated by energy harvesting from a single Wiegand pulse. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2017, 53, 4002706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wilson, P.R.; Leite, R.B.; Chen, G.; Freitas, H.; Asadi, K.; Smits, E.C.; Katsouras, I.; Rocha, P.R. An Energy Harvester for Low-Frequency Electrical Signals. Energy Technol. 2020, 8, 2000114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Chang, J.-Y. Novel Wiegand-effect based energy harvesting device for linear magnetic positioning system. Microsyst. Technol. 2020, 26, 3421–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Lee, C.; Wang, Y.-J.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. Energy Harvester Based on an Eccentric Pendulum and Wiegand Wires. Micromachines 2022, 13, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, H.-L.; Chang, J.-Y. Magnetic Reference Mark in a Linear Positioning System Generated by a Single Wiegand Pulse. Sensors 2022, 22, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, J.R.; Velinsky, M. Bistable Magnetic Device. U.S. Patent 3,820,090, 25 June 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.; Matsushita, A. Induced Pulse Voltage in Twisted Vicalloy Wire with Compound Magnetic Effect. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1995, 31, 3152–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, J.R. Switchable Magnetic Device. U.S. Patent 4,247,601, 27 January 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.; Matsushita, A.; Naoe, M. Annealing and Torsion Stress Effect on Magnetic Anisotropy and Magnetostriction of Vicalloy Fine Wire. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1997, 33, 3916–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.; Matsushita, A.; Naoe, M. Dependence of Large Barkhausen Jump on Length of a Vicalloy Fine Wire with Torsion Stress. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1998, 34, 1318–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, C.; Song, Z.; Takemura, Y. Magnetic Structure of Wiegand Wire Analyzed by First-Order Reversal Curves. Materials 2022, 15, 6951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhorukov, Y.P.; Telegin, A.V.; Lobov, I.D.; Naumov, S.V.; Dubinin, S.S.; Merencova, K.A.; Artemyev, M.S.; Nosov, A.P. Magnetooptical Faraday and Kerr effects in nanosized BiYIG/GGG structures. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2024, 608, 172415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.