Abstract

P. peruviana is a species of agronomic and biotechnological interest; however, the relationship between in vitro regeneration and phenolic compound production remains poorly explored. This study evaluated the combined effects of thidiazuron (TDZ), explant type (cotyledon and hypocotyl), auxin type (naphthaleneacetic acid, NAA, or indole-3-butyric acid, IBA), and auxin concentration on shoot organogenesis, photosynthetic pigment content, and phenolic accumulation. An initial screening identified 4.54 µM TDZ as the optimal concentration for shoot induction. Subsequent experiments showed that morphogenic and physiological responses were strongly dependent on the interaction among explant type, auxin type, and auxin dose. Cotyledon explants consistently exhibited higher shoot regeneration, vigor, biomass accumulation, and photosynthetic pigment content than hypocotyl explants, which showed reduced physiological performance and a higher tendency for callus formation. NAA-based treatments primarily enhanced morphogenic traits, whereas IBA-based treatments were associated with increased photosynthetic pigment content and phenolic accumulation. Multivariate analysis integrating morphogenic, physiological, and biochemical variables identified cotyledon explants cultured with 0.5 µM IBA in the presence of 4.54 µM TDZ as the treatment achieving the most favorable balance between shoot regeneration, physiological stability, and controlled phenolic accumulation. These findings provide a robust basis for optimizing in vitro culture systems of P. peruviana that balance growth, physiological integrity, and secondary metabolism.

1. Introduction

Physalis peruviana L. (Solanaceae) is a crop of increasing agronomic and biotechnological interest due to its nutritional value and its capacity to accumulate secondary metabolites with antioxidant, antimicrobial, and pharmacological properties. Recent metabolomic studies have identified a wide diversity of withanolides, physalins, phenolic acids, and flavonoids in this species, which significantly contribute to its bioactive potential [1,2,3,4]. Among these compounds, phenolics are of particular interest because of their high antioxidant capacity and their role in plant defense mechanisms. Leaves have been reported to contain one of the tissues with the highest concentrations of phenols and flavonoids, making them an attractive source for biotechnological applications based on in vitro culture [2,5,6].

Plant tissue culture is an efficient platform for the controlled and continuous production of biomass and secondary metabolites of interest, such as phenolic compounds, through the use of standardized propagation protocols. These protocols include the selection of the explant type and the application of plant growth regulators (PGRs) that modulate cell growth and metabolism [7]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that auxins and cytokinins influence not only organogenesis but also the activation of biosynthetic pathways associated with phenolic metabolism [8,9,10]. In this context, the auxin–cytokinin interaction plays a central role in cellular reprogramming and in the balance between proliferation, differentiation, and secondary metabolite synthesis [11,12,13].

Thidiazuron (TDZ), a thiadiazole-substituted phenylurea, is distinguished by its vigorous cytokinin-like activity and its ability to alter endogenous hormonal balance, inducing dose-dependent morphogenic and metabolic responses [14,15,16]. Adenine-type cytokinins are typically used at higher concentrations than TDZ because they are susceptible to cytokinin-degrading enzymes (CYTOKININ OXIDASE/DEHYDROGENASES (CKXs)); whereas TDZ binds to the binding sites of these enzymes, inhibiting them and thus preventing irreversible cytokinin degradation [17]. Furthermore, TDZ regulates the biosynthesis and accumulation of endogenous auxins and cytokinins, primarily adenine-type cytokinins, improving in vitro plant tissue regeneration and callus induction [18,19]. TDZ is hydrolytically stable at pH 5.9 and room temperature and its phenyl and thiadiazole functional groups contribute significantly to its chemical activity [17,20].

In addition to promoting organogenesis, TDZ has been reported to act as an elicitor capable of activating physiological responses associated with controlled stress and phenolic compound accumulation, possibly through the modulation of redox status and hormonal signaling pathways [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The combination of TDZ with auxins such as naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) or indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) has been shown to enhance phenolic accumulation in different in vitro systems significantly; however, the outcomes depend on tissue type, hormone concentration, and the specific hormonal interaction established [8,21,27,28].

Explants with high plasticity for inducing de novo organogenesis and somatic em-bryogenesis, such as cotyledon and hypocotyl segments, cultured in the presence of TDZ, BAP (6-Benzylaminopurine), IBA, and/or NAA have been used for the in vitro regeneration of several species, such as Prunus armeniaca [29], Cannabis sativa [30], and Vitis vinifera [31]. The regenerative capacity of cotyledons and hypocotyls can surpass that of other explants, such as true leaves [30], and they have potential applications in plant breeding and in the development of polyploid varieties for the production of secondary metabolites [30,32]. However, the response of these explants depends on the species, variety, and the auxin/cytokinin ratio used [29,32].

Studies in other Solanaceae indicate that the regenerative response obtained under auxin–cytokinin-based in vitro systems is strongly conditioned by explant origin. In Lycium barbarum and several Solanum species, cotyledon explants generally show higher frequencies of direct shoot organogenesis and better shoot development than hypocotyl tissues, which more often display reduced morphogenic efficiency and increased callus formation when exposed to comparable hormonal conditions [14,33,34]. These differences have been mainly associated with the juvenile status of cotyledon tissues and with explant-specific endogenous hormonal and metabolic backgrounds that influence developmental competence [34,35]. Similar explant-dependent patterns have been reported across Solanaceae and other medicinal plants, supporting the notion that morphogenic outcomes are not solely driven by exogenous growth regulators, but by their interaction with intrinsic tissue properties, providing a relevant comparative framework for evaluating explant-specific responses in Physalis peruviana L.

In P. peruviana, in vitro regeneration studies have mainly focused on cotyledon explants and limited combinations of PGRs, with an emphasis on micropropagation and genetic improvement [36,37,38,39]. However, knowledge of how explant type and auxin × TDZ interactions simultaneously modulate organogenic competence and phenolic metabolism remains limited. This gap is particularly relevant given that explant origin strongly determines both regenerative capacity and metabolic profiles in Solanaceae species [33,34,35]. To date, comprehensive evaluations integrating the effects of explant type, auxin, and TDZ on morphogenesis, biomass production, and phenolic accumulation remain lacking.

In this study, the responses of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants of P. peruviana to combinations of TDZ with NAA or IBA were comparatively evaluated by analyzing organogenesis, biomass production, and phenolic compound accumulation. We hypothesized that specific interactions between explant type and auxin, in the presence of TDZ, differentially modulate morphogenesis and biosynthetic potential, allowing the simultaneous optimization of shoot regeneration and phenolic production in in vitro systems aimed at high-value biomass and metabolite production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Seed Pretreatment

Seeds of Physalis peruviana L., Colombian ecotype, were used in this study. Seeds were obtained from plants established from certified seeds purchased from Sierra Seeds (Lima, Peru) in 2024. Fruits at physiological maturity were harvested from mother plants exhibiting adequate phytosanitary status, with no visible symptoms of pest or disease damage, and optimal nutritional condition. The fruits were manually crushed, and the seeds were fermented for 96 h at 28 °C in complete darkness. Subsequently, the seeds were thoroughly washed with tap water to completely remove the mucilage, air-dried at room temperature, and stored at 4 °C until use.

2.2. Surface Disinfection, In Vitro Seed Germination, and Culture Conditions

Before surface disinfection, seeds were imbibed in distilled water for 48 h. Surface disinfection was performed under a laminar air flow (LAF) cabinet (BIOBASE BBS-H1300, BIOBASE, Jinan, China). It consisted of immersing the seeds in a 2% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl; Clorox, Lima, Peru) solution supplemented with 0.01% (v/v) Tween-80 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), followed by four rinses with sterile distilled water [39]. After disinfection, seeds were aseptically sown in Magenta™ GA-7 vessels (PhytoTech Labs, Lenexa, KS, USA) containing Murashige and Skoog (MS) [40] basal medium with vitamins (PhytoTech Labs, Lenexa, KS, USA), supplemented with 30 g L−1 sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 7 g L−1 agar (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The medium pH was adjusted to 5.8 before autoclaving at 121 °C and 2.05 bar for 15 min. Cultures were maintained in a growth room under controlled conditions: 25 ± 1 °C under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod, with a light intensity of approximately 70 µmol m−2 s−1 provided by cool white LED lamps (6500 K).

2.3. Determination of the Optimal TDZ Concentration for In Vitro Regeneration

Fourteen-day-old P. peruviana L. seedlings, vigorous and free of physical damage, morphological abnormalities, or chlorosis, were used as explant sources. Under sterile conditions, two types of explants were excised: (i) fully expanded cotyledons, without petioles, placed with the adaxial surface in contact with the culture medium, and (ii) hypocotyl segments approximately 5 mm in length, excluding basal and apical regions. These two explants were selected based on preliminary results, in which their shoot regeneration capacity was superior compared to true leaf segments and the level of hyperhydricity of the induced shoots was lower when compared to those from nodal segments on MS + TDZ (9 µM) media.

Explants were cultured in Petri dishes (120 × 20 mm) containing 20 mL of MS medium supplemented with 30 g L−1 sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 7 g L−1 agar (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and six concentrations of thidiazuron (TDZ; PhytoTech Labs, Lenexa, KS, USA) (0.045, 0.23, 0.45, 2.27, 4.54, and 6.81 µM). The medium pH was adjusted to 5.8 before sterilization. The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized design with a 2 × 6 factorial structure, corresponding to two explant types (cotyledon and hypocotyl) and six TDZ concentrations. Each treatment consisted of 6 replicates of 10 explants, for a total of 720 explants. After four weeks of culture, explants were transferred to Magenta™ GA-7 vessels (PhytoTech Labs, Lenexa, KS, USA) containing TDZ-free MS medium to promote shoot development and elongation for an additional six weeks. At the end of the experimental period, morphogenic responses were recorded, including the percentage of shoot regeneration and the number of shoots per regenerated explant.

2.4. Evaluation of In Vitro Morphogenesis Induced by TDZ, NAA, and IBA in Cotyledon and Hypocotyl Explants of P. peruviana

After identifying the optimal TDZ concentration (4.54 µM), the effects of the auxins naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA; PhytoTech Labs, Lenexa, KS, USA) and indole-3-butyric acid (IBA; PhytoTech Labs, Lenexa, KS, USA) on the morphogenic capacity of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants were evaluated. The experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design with a 2 × 2 × 5 factorial arrangement, corresponding to two explant types (cotyledon and hypocotyl), two auxins (NAA and IBA), and five auxin concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.25, and 2.5 µM), resulting in a total of 20 treatments. Each treatment included six replicates, each replicate consisting of five explants cultured in the same vessel, for a total of 600 explants (n = 600).

Culture conditions were identical to those described in Section 2.2. After four weeks of culture on media supplemented with TDZ and auxin, explants were transferred to TDZ- and auxin-free MS medium and maintained for an additional six weeks before assessment of morphogenic parameters, photosynthetic pigment content, and total phenolic compounds.

2.5. Morphogenic Parameters

Morphogenic parameters were evaluated at the end of the in vitro culture cycle. They included shoot regeneration ratio (%), number of shoots per regenerating explant, shoot-forming capacity (SFC) index, shoot vigor, main shoot length (mm), number of leaves per main shoot, shoot fresh mass (mg), shoot dry mass (mg), callus fresh mass (mg), callus dry mass (mg) and callus formation score.

The SFC index was calculated as (mean number of shoots per explant × percentage of shoot regeneration)/100, as described by [41]. Callus fresh mass (mg explant−1) was determined by dividing the total callus mass by the initial number of explants, whereas shoot fresh mass corresponded to the aerial biomass of regenerated shoots separated from callus tissue.

Shoot vigor was evaluated using a four-point ordinal scale, where

1 = shoots with more than 50% chlorosis and poorly developed or deformed leaves;

2 = green shoots with a barely differentiated apical bud or shoots with ≤50% chlorosis;

3 = green shoots with limited elongation (<5 mm) or chlorosis <25%;

4 = vigorous, well-developed shoots with expanded leaves and stems longer than 5 mm.

Callus formation was scored using a scale from 0 to 4, defined as follows:

0 = absence of callus or any visible swelling;

1 = slight swelling or callus present in up to 25% of the explant;

2 = callus covering 25–50% of the explant;

3 = abundant callus covering 50–75% of the explant;

4 = profuse callus covering more than 75% of the explant tissue.

Shoot vigor and callus formation were treated as ordinal variables and were therefore analyzed exclusively using non-parametric statistical tests.

2.6. Photosynthetic Pigments and Total Phenolic Content

2.6.1. Extract Preparation

It was performed according to Ríos-Ríos et al. [42], with minor modifications. Leaf material was harvested, oven-dried at 40 °C for 96 h, and ground to obtain a homogeneous powder, which was stored in 2 mL Eppendorf tubes at −20 °C until analysis. For extraction, 10 mg of dry powder were suspended in 1.5 mL of HPLC-grade methanol (MeOH; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The suspension was vortexed (1200 rpm, 30 s) and sonicated in an ultrasonic bath (Branson 1210, Marshall Scientific®, Hampton, NH, USA) for 15 min at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C). Samples were then vortexed again (2500 rpm, 30 s) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min using a refrigerated centrifuge (Eppendorf 5430 R, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). The supernatant was filtered through 0.22 µm hydrophilic polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) syringe filters (Ø 25 mm; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), and the final volume was adjusted to 1.5 mL with MeOH. All extracts were stored at 4 °C and analyzed within 48 h.

2.6.2. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments

An aliquot of 50 µL of extract was diluted with 150 µL of MeOH and transferred to 96-well microplates. Absorbance was measured at 470, 653, and 666 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer equipped with a microplate reader (Varioskan™ LUX, Thermo Scientific™, Life Technologies Holdings Pte Ltd., Singapore). Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total carotenoid concentrations were calculated using the equations proposed by [43], with optical pathlength correction for the microplate format. Results were expressed as micrograms of pigment per milligram of dry weight (µg mg−1 DM), according to the following equations:

- Chlorophyll a = [(15.65 × A666 − 7.34 × A653) × 200]/1000

- Chlorophyll b = [(27.05 × A653 − 11.21 × A666) × 200]/1000

- Total carotenoids = {[(1000 × A470 − 2.86 × Ca − 129.2 × Cb)/221] × 200}/1000

where Ca and Cb correspond to chlorophyll a and b concentrations, respectively.

2.6.3. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric method [44], following the microplate adaptation described by [45]. In 96-well microplates, 100 µL of distilled water, 25 µL of extract, and 25 µL of diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (1:10, v/v; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were mixed and incubated in darkness for 1 min. Subsequently, 50 µL of a 10% (w/v) sodium carbonate (Na2CO3; Spectrum Chemical, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) solution was added, thoroughly mixed, and incubated in complete darkness at room temperature for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a UV–Vis microplate reader (Varioskan™ LUX, Thermo Scientific™, Life Technologies Holdings Pte Ltd., Singapore).

Quantification was performed using a gallic acid standard curve (10–50 µg mL−1), with the regression equation A = 0.0058C − 0.0606 (R2 = 0.9975), where A represents absorbance and C the standard concentration. Results were expressed as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents per milligram of dry weight (µg GAE mg−1 DM).

2.7. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a completely randomized design (CRD). The two experiments were analyzed independently.

In the first experiment, morphogenic variables did not satisfy the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances (Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests), even after data transformation. Therefore, differences among TDZ concentrations within each explant type were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with p-values adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate [46].

The second experiment was conducted under a factorial design (2 × 2 × 5). Assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were assessed for all variables, and data were transformed when necessary. Shoot regeneration (%) was transformed using the arcsine square-root transformation after conversion to proportions. Main shoot length and callus fresh mass were square-root transformed. The number of leaves per shoot was transformed using the natural logarithm, and callus dry mass was transformed using a Box–Cox transformation (λ = 0.5). Morphogenic variables, as well as photosynthetic pigment contents and total phenolic content, were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Factorial ANOVA was applied to test main effects and interactions among explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration (E × A × D). Mean comparisons were performed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test at p < 0.05.

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed in R software (version 4.4.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [33], using the packages agricolae [47], dplyr [48], and ggplot2 [49]. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the FactoMineR package version 2.11 [50], and graphical representation of multivariate analyses was carried out with factoextra [51].

3. Results

3.1. Optimal TDZ Concentration for In Vitro Regeneration

The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a highly significant effect of TDZ concentration on shoot regeneration in both explant types (p < 0.001; Table 1). In cotyledon explants, intermediate TDZ concentrations resulted in the highest regenerative responses, with 4.54 µM producing the maximum shoot regeneration frequency and the highest number of shoots per regenerating explant. Lower TDZ concentrations (<0.45 µM) were largely ineffective, whereas the highest concentration tested (6.81 µM) did not further improve regeneration and resulted in reduced shoot quality.

Table 1.

Effect of thidiazuron (TDZ) concentration on in vitro shoot regeneration in cotyledon and hypocotyl explants of P. peruviana.

Hypocotyl explants exhibited a similar dose-dependent trend but with overall lower regenerative competence compared with cotyledon explants. TDZ concentrations of 4.54 and 6.81 µM induced the highest shoot regeneration and proliferation rates, whereas concentrations below 0.45 µM showed limited morphogenic response. Based on these results, 4.54 µM TDZ was selected as the optimal concentration for subsequent experiments, as it consistently promoted high shoot regeneration and proliferation while avoiding the reduced efficiency observed at lower concentrations and the lack of further improvement at higher doses.

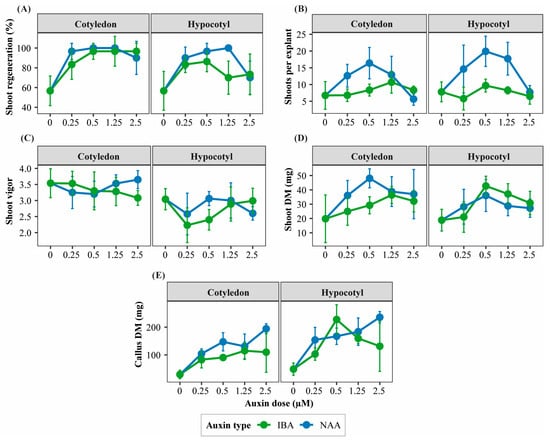

3.2. Effects of TDZ, NAA, and IBA on Morphogenic Responses

3.2.1. Interaction Effects Among Explant Type, Auxin Type, and Auxin Concentration (E × A × D)

Factorial ANOVA revealed that the interaction among explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration (E × A × D) significantly affected most morphogenic parameters evaluated in P. peruviana (Table S1), indicating that morphogenic responses were strongly conditioned by both explant origin and hormonal context.

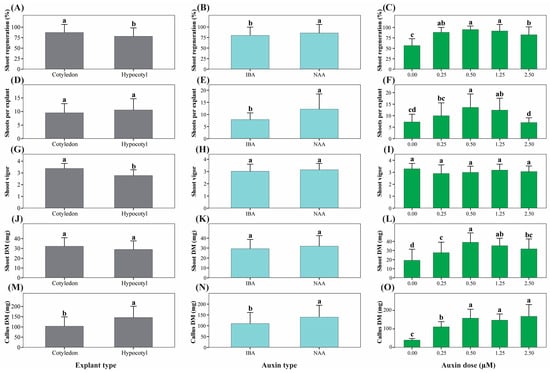

Morphogenic Response

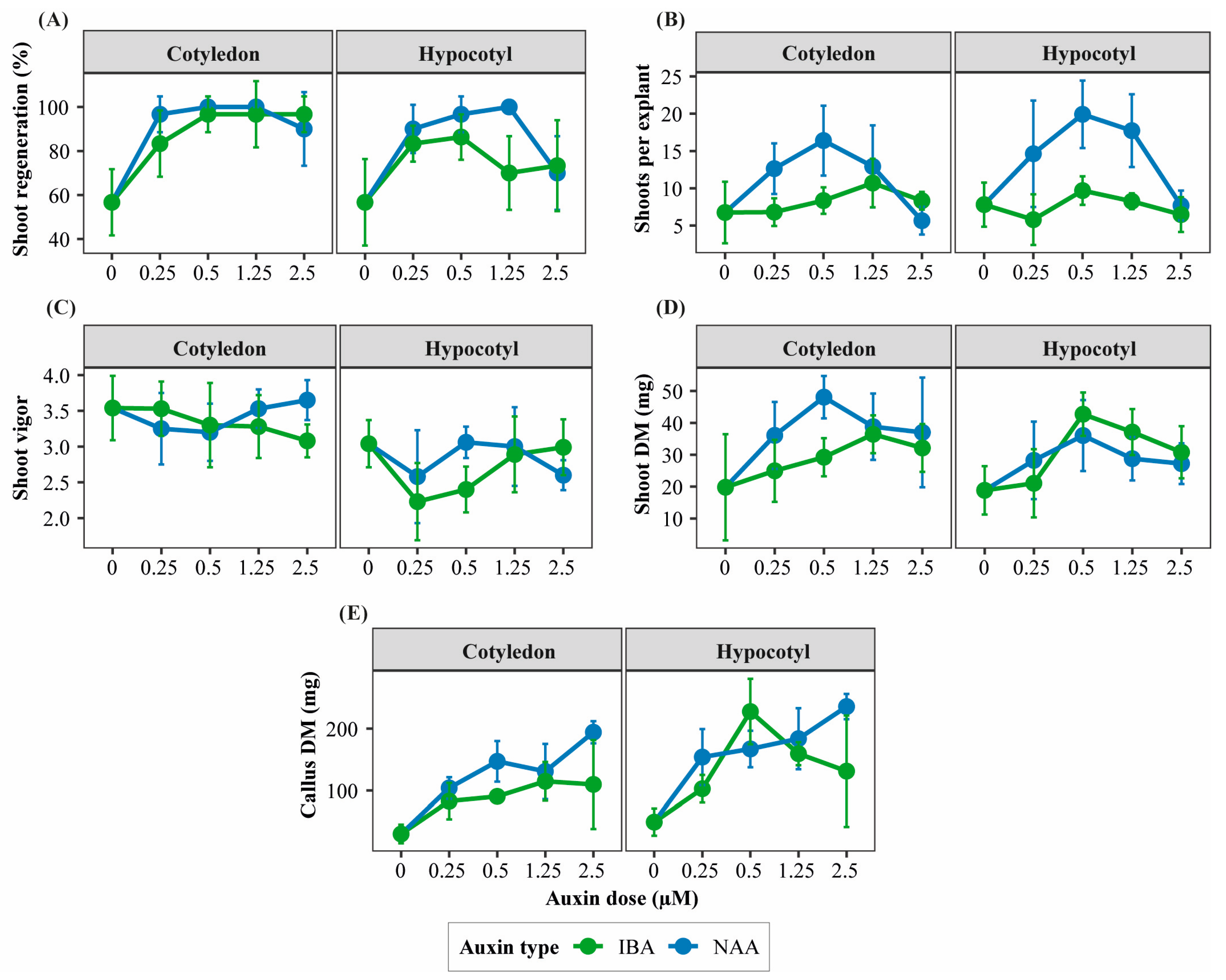

Cotyledon explants exhibited higher morphogenic competence than hypocotyl explants, particularly when cultured with NAA at intermediate concentrations. In contrast, hypocotyl explants showed more variable responses, characterized by a progressive shift toward callus formation as auxin concentration increased (Table S2; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction patterns among explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration affecting morphogenic responses of Physalis peruviana. Panels show treatment-dependent response patterns of key morphogenic traits in cotyledon and hypocotyl explants cultured under different auxin types and concentrations: (A) shoot regeneration ratio (%), (B) number of shoots per regenerating explant, (C) shoot vigor score, (D) shoot dry mass (mg), and (E) callus dry mass (mg). Responses are shown separately for explant type and auxin type (naphthaleneacetic acid, NAA; indole-3-butyric acid, IBA) across increasing auxin concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.50, 1.25, and 2.50 µM) in the presence of TDZ. Points represent mean values ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6 replicates per treatment, each replicate consisting of 5 explants). Lines are shown to visualize interaction patterns among factors.

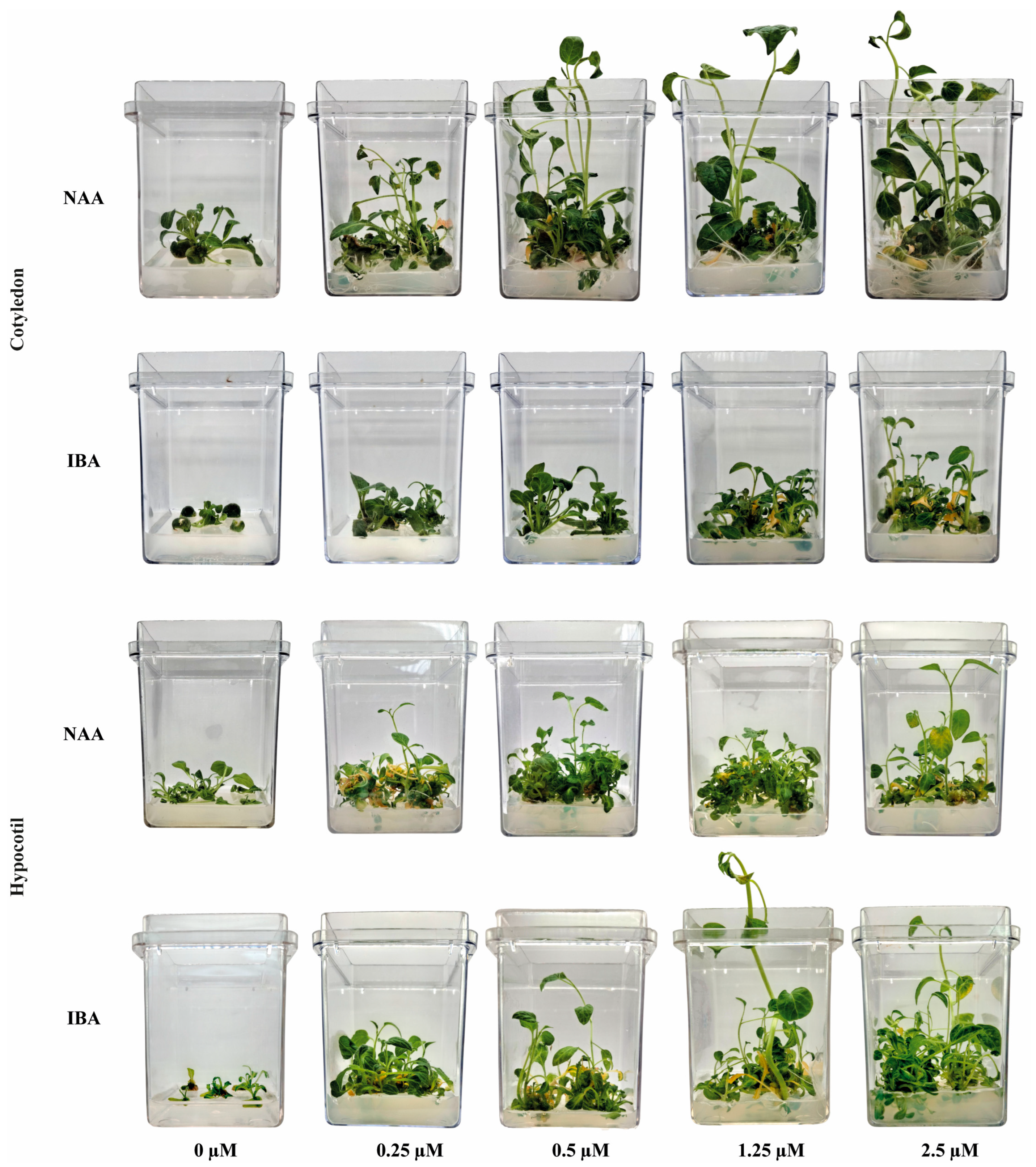

In cotyledon explants, NAA promoted higher shoot regeneration frequency, number of shoots per regenerating explant, and SFC index than IBA, with optimal responses observed at intermediate auxin concentrations (0.25–1.25 µM; Figure 1A,B and Figure 2). These treatments also maintained high shoot vigor, reflecting efficient shoot organogenesis (Table S2).

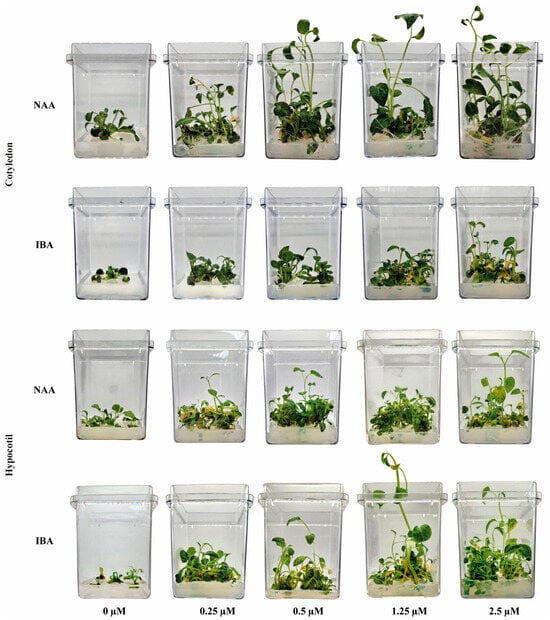

Figure 2.

Representative morphogenic outcomes of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants of Physalis peruviana cultured under different auxin types (NAA and IBA) and concentrations in the presence of TDZ. Representative images illustrate typical shoot regeneration, shoot development, and callus formation observed in cotyledon and hypocotyl explants cultured with naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) or indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) at increasing auxin concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.50, 1.25, and 2.50 µM). Images are shown to highlight qualitative differences in morphogenic outcomes among treatments.

In hypocotyl explants, NAA enhanced shoot regeneration and SFC at low to intermediate concentrations; however, increasing auxin levels progressively favored callogenesis over shoot formation. IBA generally resulted in lower shoot regeneration but promoted shoot elongation at specific concentrations (Table S2; Figure 1B,C and Figure 2).

Shoot biomass accumulation followed trends similar to regeneration efficiency. Cotyledon explants cultured with intermediate NAA concentrations produced the highest shoot fresh and dry biomass, whereas hypocotyl explants accumulated proportionally greater callus biomass across most auxin treatments (Table S2; Figure 1D,E and Figure 2).

3.2.2. Main Effects of Explant Type, Auxin Type, and Auxin Concentration on Morphogenic Responses

Analysis of main effects derived from factorial ANOVA showed that explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration significantly influenced most morphogenic variables (p < 0.05; Table S3).

Effect of Explant Type

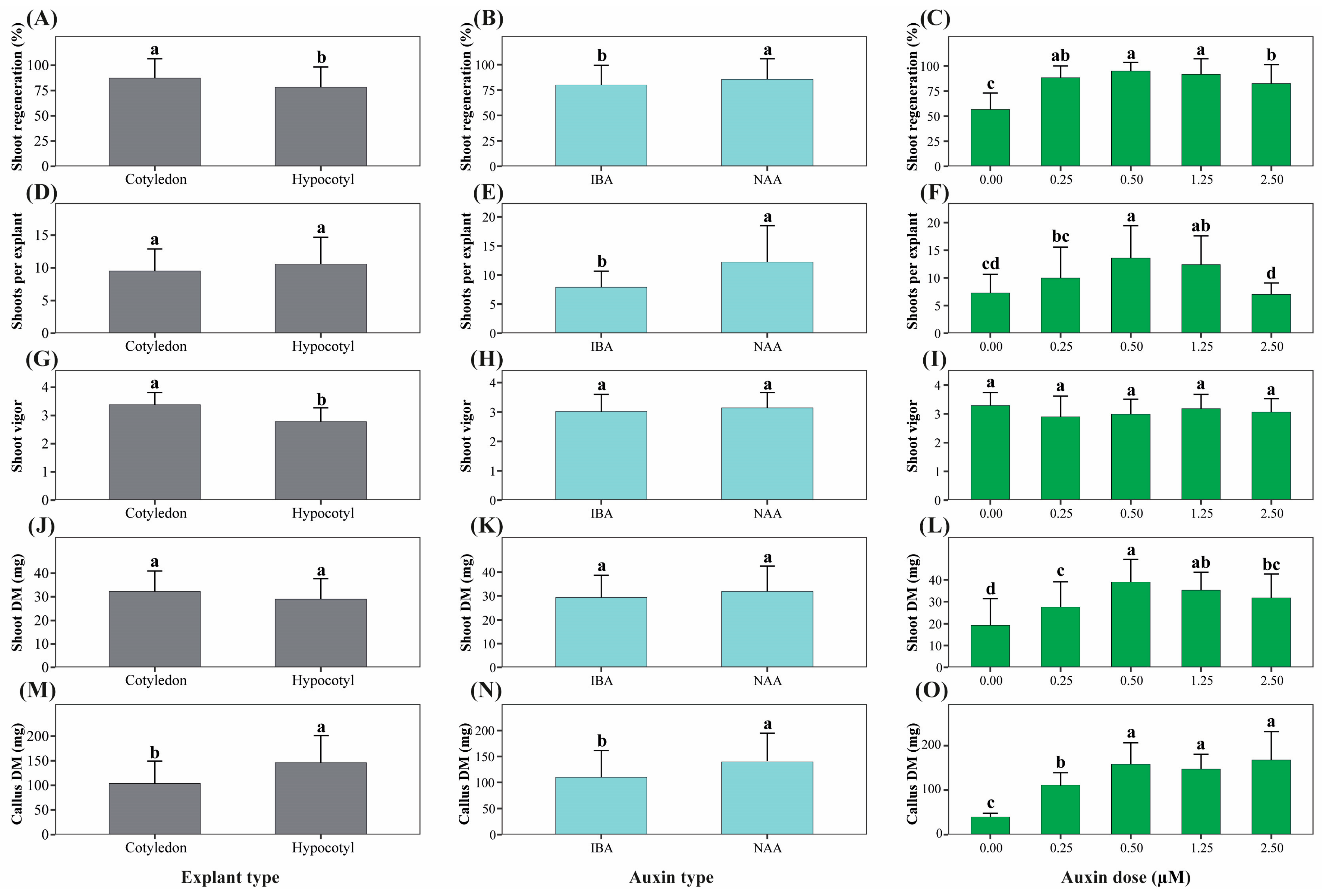

Cotyledon explants exhibited significantly higher shoot regeneration frequency, shoot vigor, number of leaves per shoot, and shoot fresh biomass compared with hypocotyl explants (Figure 2 and Figure 3A,D,G). In contrast, hypocotyl explants showed significantly higher callus fresh and dry biomass and higher callus formation scores, indicating a greater tendency toward callogenesis (Figure 3J,M).

Figure 3.

Main effects of explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration on morphogenic responses of Physalis peruviana. Panels show main effects derived from factorial ANOVA on key morphogenic traits: shoot regeneration ratio (%) (A–C), number of shoots per regenerating explant (D–F), shoot vigor score (G–I), shoot dry mass (mg) (J–L), and callus dry mass (mg) (M–O). Main effects of explant type (A,D,G,J,M), auxin type (B,E,H,K,N), and auxin concentration (C,F,I,L,O) are presented separately. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6 replicates per treatment, each replicate consisting of 5 explants). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among levels of each factor based on factorial ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

Effect of Auxin Type

NAA induced superior morphogenic responses relative to IBA, including higher shoot regeneration, number of shoots per regenerating explant, SFC index, shoot elongation, and callus biomass (Figure 2 and Figure 3B,E,N). Callus formation was also enhanced under NAA treatment, whereas shoot vigor (Figure 3H) and shoot dry biomass (Figure 3K) were not significantly affected by auxin type alone.

Effect of Auxin Concentration

Auxin concentration significantly affected most morphogenic parameters (Table S3). The absence of auxins resulted in the lowest regeneration frequency and biomass accumulation (Figure 3C,L,O). Intermediate auxin concentrations (0.50–1.25 µM) maximized shoot regeneration, number of shoots, SFC index, and shoot biomass, whereas higher concentrations progressively promoted callus formation at the expense of shoot quality (Figure 3F,I).

3.3. Effects of TDZ, NAA, and IBA on Physiological Responses

3.3.1. Effect of the Interaction Between Explant Type, Auxin Type, and Auxin Concentration (E × A × D) on Physiological Responses

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that physiological responses were mainly influenced by two-way interactions rather than by the three-way interaction (Table 2).

Table 2.

Significance of interaction effects among explant type (E), auxin type (A), and auxin concentration (D) on physiological responses of P. peruviana.

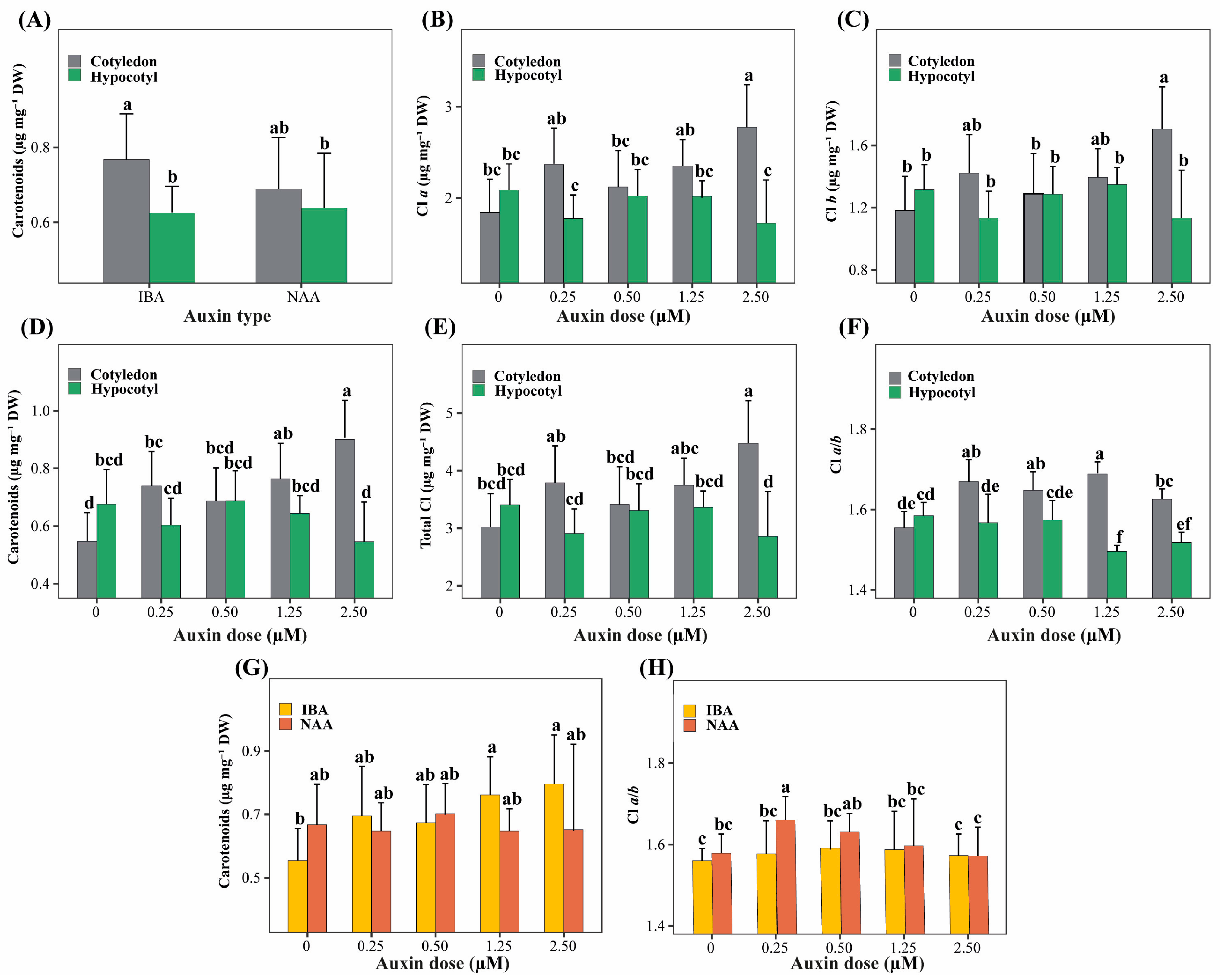

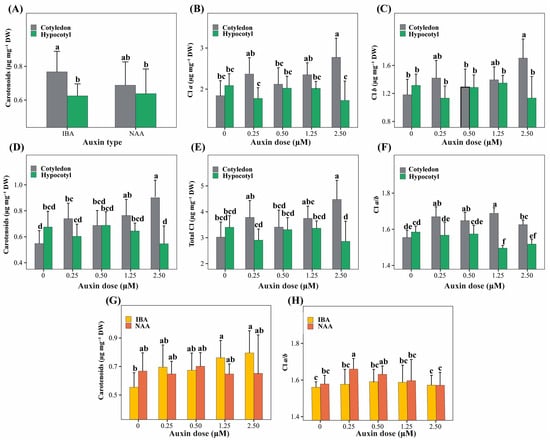

The interaction between explant type and auxin type (E × A) did not significantly affect chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll content, or the chlorophyll a/b ratio (p > 0.05). Still, it significantly influenced carotenoid content (Figure 4A). Within this interaction, shoots derived from cotyledon explants treated with IBA exhibited the highest carotenoid concentrations, whereas shoots derived from hypocotyl explants showed lower values regardless of auxin type.

Figure 4.

Significant two-way interaction effects among explant type (cotyledon, hypocotyl), auxin type (NAA, IBA), and auxin concentration (0–2.50 µM) on physiological traits related to photosynthetic pigment content in P. peruviana. Panels show the interaction terms that were statistically significant in the ANOVA model. (A) E × A for carotenoids; (B–F) E × D for chlorophyll a (B), chlorophyll b (C), carotenoids (D), total chlorophyll (E), and chlorophyll a/b ratio (F); (G,H) A × D for carotenoids (G) and chlorophyll a/b ratio (H). Bars represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6 replicates per treatment, each replicate consisting of 5 explants). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among interaction levels, as determined by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

The interaction between explant type and auxin concentration (E × D) was highly significant for all photosynthetic parameters evaluated (p < 0.001; Figure 4B–F). Cotyledon explants showed a dose-dependent increase in chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoid contents, reaching maximum values at the highest auxin concentration. In contrast, hypocotyl explants maintained consistently lower pigment levels across all auxin concentrations. The chlorophyll a/b ratio was also significantly affected by this interaction, with higher values observed in cotyledon explants at intermediate auxin concentrations and lower values in hypocotyl explants at medium to high auxin doses.

The interaction between auxin type and auxin concentration (A × D) significantly affected carotenoid content and the chlorophyll a/b ratio (Figure 4G,H). Intermediate to high concentrations of IBA promoted greater carotenoid accumulation, whereas treatments without auxins showed the lowest values. Conversely, higher chlorophyll a/b ratios were associated with low NAA concentrations, while treatments with IBA at extreme doses resulted in lower ratios.

The three-way interaction (E × A × D) was not significant for most physiological parameters (p > 0.05), except for the chlorophyll a/b ratio (p = 0.030); therefore, it was not considered further in the analysis.

3.3.2. Main Effects of Explant Type, Auxin Type, and Auxin Concentration on Physiological Responses

Analysis of main effects indicated that explant type had a highly significant influence on the accumulation of photosynthetic pigments (p < 0.001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Main effects of explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration on photosynthetic pigment profiles of P. peruviana.

Shoots derived from cotyledon explants exhibited significantly higher concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, carotenoids, and higher chlorophyll a/b ratios compared with shoots derived from hypocotyl explants.

Auxin type did not significantly affect chlorophyll a, carotenoid content, or total chlorophyll (p > 0.05; Table 3), but it significantly influenced chlorophyll b concentration and the chlorophyll a/b ratio, with higher values observed under IBA compared with NAA.

Auxin concentration significantly affected carotenoid content and the chlorophyll a/b ratio (p < 0.05), with higher values associated with the presence of auxin. In contrast, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were not significantly influenced by auxin concentration alone (p > 0.05).

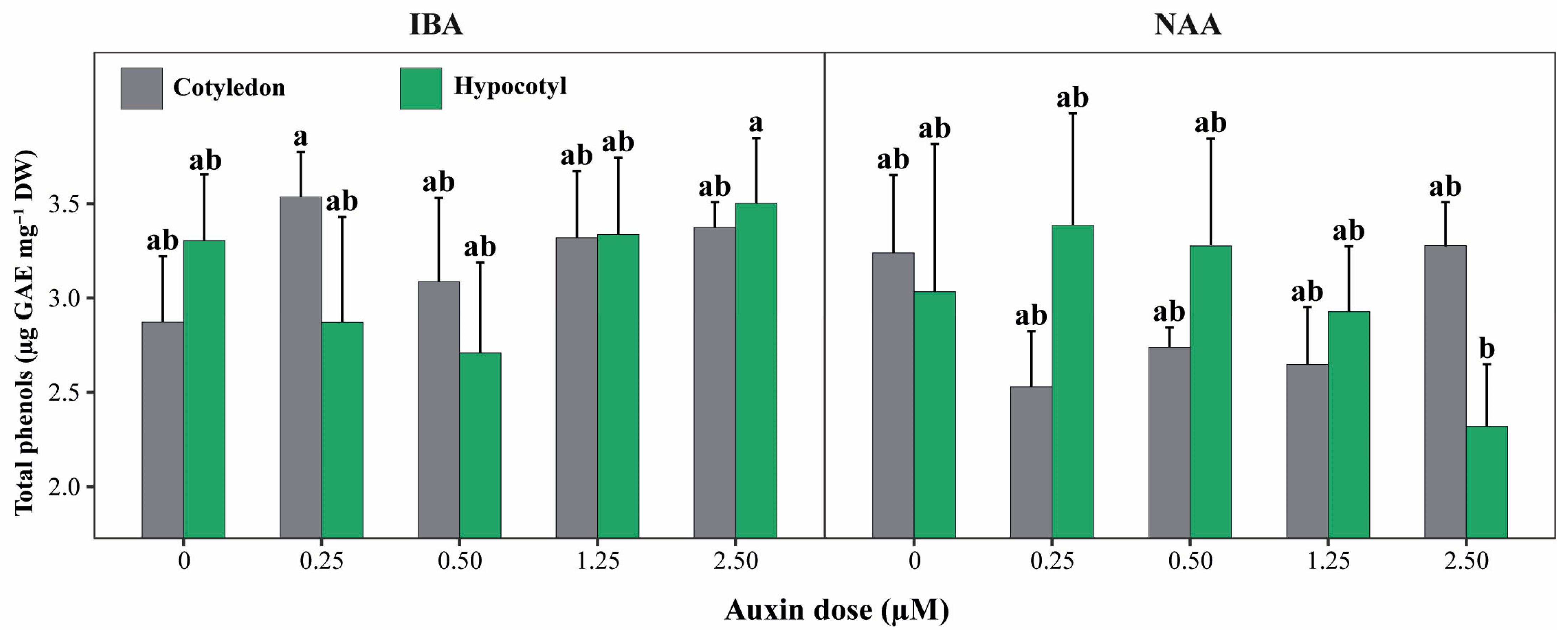

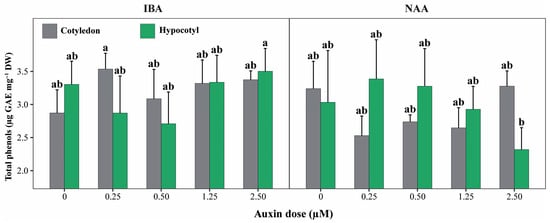

3.4. Effects of Explant Type, Auxin Type, and Auxin Concentration on Total Phenolic Compound Production

Analysis of main effects (Table S4) indicated that explant type did not significantly influence total phenolic content (p = 0.97). In contrast, auxin type has a significant impact (p = 0.01), with explants treated with IBA showing higher total phenolic accumulation than those treated with NAA. Auxin concentration, when evaluated as a primary factor, did not significantly affect total phenolic content (p = 0.81).

Beyond main effects, phenolic compound accumulation was primarily determined by the three-way interaction among explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration (E × A × D), which was highly significant (p < 0.001; Figure 5). In contrast, none of the two-way interactions (E × A, E × D, or A × D) showed significant effects on total phenolic content (p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Total phenolic content of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants of P. peruviana under different auxin types and concentrations. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of total phenolic content in shoots derived from cotyledon and hypocotyl explants cultured with IBA or NAA at concentrations ranging from 0 to 2.50 µM. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among explant × auxin × concentration (E × A × D) combinations, determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). Bars represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6 replicates per treatment, each replicate consisting of 5 explants). Treatments sharing the same letter are not significantly different, indicating that phenolic accumulation was statistically similar across most auxin concentrations and explant types, except for the highest and lowest responding combinations.

In absolute terms, total phenolic content across treatments ranged from 2.32 to 3.54 µg GAE mg−1 DM. The highest phenolic levels were observed in shoots derived from cotyledon explants treated with IBA at 0.25 µM (3.54 ± 0.24 µg GAE mg−1 DM) and in hypocotyl explants exposed to IBA at 2.50 µM (3.50 ± 0.35 µg GAE mg−1 DM), with statistically similar mean values (Figure 5). Several additional IBA-based treatments, including cotyledon explants at 1.25 and 2.50 µM and hypocotyl explants at intermediate IBA concentrations, showed comparably high phenolic contents (≈3.30–3.37 µg GAE mg−1 DM).

In contrast, the lowest phenolic accumulation was recorded in hypocotyl explants treated with NAA at 2.50 µM (2.32 ± 0.33 µg GAE mg−1 DM), which differed significantly from the highest-ranking treatments. Overall, these results demonstrate that phenolic compound production in P. peruviana is not driven by explant type or auxin concentration alone, but by specific combinations of explant origin and auxin regime, particularly under IBA treatments.

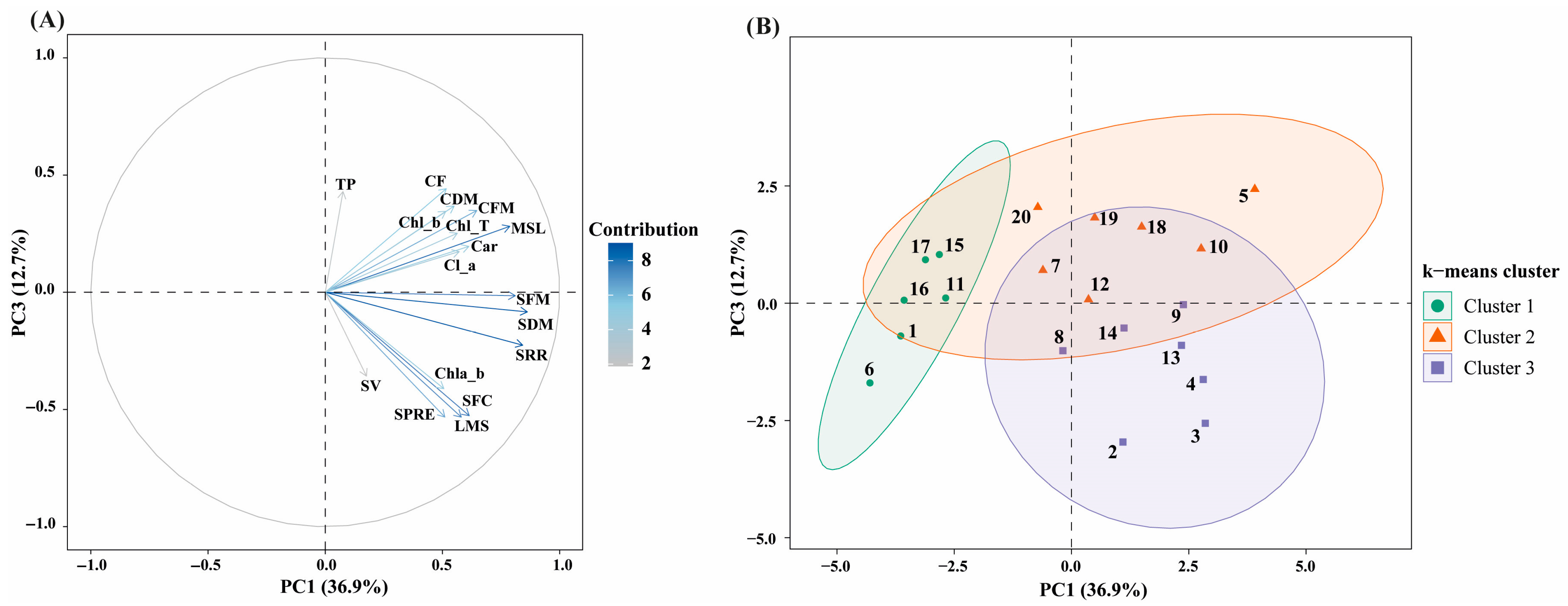

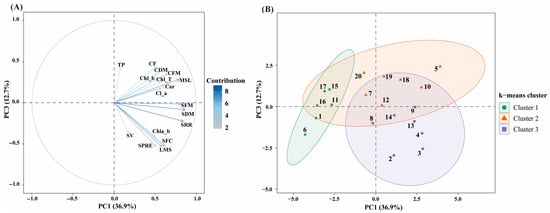

3.5. Principal Component Analysis and Clustering

Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to integrate morphogenic, physiological, pigment-related, and biochemical traits and to identify multivariate patterns among explant types and auxin + TDZ treatments in Physalis peruviana (Figure 6). The first three principal components explained 78.7% of the total variance, with PC1 accounting for 36.9%, PC2 for 29.1%, and PC3 for 12.7%, indicating a robust multivariate structure.

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis (PCA) integrating morphogenic, physiological, pigment-related, and biochemical traits in P. peruviana. (A) PCA biplot showing the projection of variables on the PC1–PC3 plane, which together explain 49.6% of the total variance. Vector length and color intensity indicate the relative contribution of each variable to the principal components. (B) core plot of treatments projected on the PC1–PC3 plane and grouped by k-means clustering (k = 3). Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals for each cluster. Variable abbreviations are as follows: Chl_a, chlorophyll a; Chl_b, chlorophyll b; Chl_T, total chlorophyll; Chl_a_b, chlorophyll a/b ratio; Car, carotenoids; TP, total phenolic content; SRR, shoot regeneration ratio; SPRE, shoots per regenerating explant; SFC, SFC index; SV, shoot vigor; MSL, main shoot length; LMS, leaves per main shoot; SFM, shoot fresh mass; SDM, shoot dry mass; CFM, callus fresh mass; CDM, callus dry mass; CF, callus formation.

PC1 was mainly associated with shoot regeneration and vegetative development, showing strong positive loadings for shoot regeneration ratio (SRR), shoots per regenerating explant (SPRE), SFC index, main shoot length (MSL), leaves per main shoot (LMS), and shoot fresh and dry biomass (SFM and SDM) (Figure 6A). Callus-related traits showed moderate positive associations along this axis, reflecting the close linkage between overall tissue growth and morphogenic competence.

PC2 was primarily associated with photosynthetic pigments and physiological quality, exhibiting strong positive loadings for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, the chlorophyll a/b ratio, carotenoids, and shoot vigor (SV). In contrast, callus fresh mass, callus dry mass, and callus formation index loaded negatively on PC2, revealing an inverse relationship between physiological quality and callogenic proliferation. This axis therefore represents a physiological quality gradient, discriminating treatments that promoted functional shoot development from those dominated by undifferentiated callus growth.

PC3 was mainly influenced by total phenolic content (TP), which showed its highest contribution along this axis. In the PC1–PC3 biplot (Figure 6A), TP was projected largely orthogonal to the main morphogenic axis (PC1), indicating a weak global association between phenolic accumulation and shoot regeneration performance.

K-means clustering (k = 3), performed on PCA scores, identified three well-defined treatment groups, consistent with the multivariate structure of the dataset (Figure 6B). Cluster 1 included treatments 1, 6, 11, 15, 16, and 17, which were characterized by low scores along PC1, reflecting reduced values for morphogenic variables such as shoot regeneration ratio, shoot number, shoot length, and shoot biomass (Figure 6B). In contrast, several treatments within this cluster exhibited moderate scores along PC2, associated with photosynthetic pigments and shoot vigor. Total phenolic content showed low contributions within this group, as reflected by near-zero or negative PC3 scores.

Cluster 2 comprised treatments 5, 7, 10, 12, 18, 19, and 20. This cluster was characterized by positive scores along PC1, indicating higher morphogenic performance and greater shoot biomass, combined with positive scores along PC3, reflecting increased total phenolic content (Figure 6B). Physiological variables associated with PC2 showed greater dispersion within this cluster, indicating variability in pigment content and shoot vigor among treatments.

Cluster 3 grouped treatments 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 13, and 14. These treatments exhibited positive PC1 scores, comparable to those observed in Cluster 2, indicating favorable morphogenic responses. However, they were distinguished by negative PC3 scores, corresponding to lower total phenolic content (Figure 6B). PC2 scores were generally intermediate, reflecting balanced values for photosynthetic pigments and shoot vigor. Overall, the clustering analysis revealed that treatments differed not only in their morphogenic and physiological profiles, but also in their association with phenolic accumulation, resulting in a structured multivariate separation among the three clusters (Figure 6B).

4. Discussion

Organogenesis in P. peruviana was strongly influenced by explant type and TDZ concentration, with intermediate levels (4.54 µM) defining a clear optimal response window. This behavior is consistent with the high cytokinin-like activity of TDZ and its well-documented capacity to induce rapid cell division, tissue reorganization, and meristematic reprogramming [52,53,54,55]. The two-step experimental design adopted in this study allowed a precise delimitation of this effective range, as maximum regeneration with morphologically regular shoots was achieved only at the optimal TDZ concentration. Lower TDZ levels were insufficient to trigger the organogenic pathway, whereas higher concentrations did not enhance regeneration and instead inhibited shoot elongation and promoted hyperhydricity. Similar inhibitory effects of excessive TDZ have been reported in other species, where compact and hyperhydric shoots develop under supra-optimal cytokinin signaling [56,57]. In the present study, the appearance of vitrified tissues at TDZ concentrations above 4.54 µM suggests a disruption of physiological homeostasis, likely associated with alterations in primary metabolism and stress-related pathways under excessive TDZ exposure [21]. TDZ typically induces morphogenic responses in plant tissues at moderate concentrations because this molecule is more stable and resistant to cytokinin-degrading enzymes, acting as an inhibitor by competing for the active site of these enzymes [17]. Exposure to TDZ concentrations above 10 µM or prolonged exposure (more than 4–6 weeks) can inhibit or reduce shoot development, inducing oxidation, necrosis, hyperhydricity, and the formation of abnormal tissues. This can be attributed, in part, to TDZ-stimulated ethylene production, which over time becomes toxic to shoots [15,17,18,20].

Marked differences in organogenic competence between cotyledon and hypocotyl explants indicate that regenerative capacity in P. peruviana is strongly conditioned by explant identity and its endogenous hormonal balance. Comparable explant-dependent responses have been reported in several Solanaceae species, in which cotyledons, hypocotyls, and leaves exhibit distinct regenerative behaviors depending on the applied growth regulator [58,59,60]. These observations underscore the high significance of the three-way interaction (Explant × Auxin × Auxin Concentration) detected in this study, reinforcing the notion that organogenesis in P. peruviana emerges from specific, non-linear hormonal interactions rather than from the isolated effects of individual factors. Such behavior is characteristic of species with highly sensitive organogenic pathways, in which fluctuations in the auxin/cytokinin balance govern the transition among shoot formation and callogenesis [61,62,63,64]. This pronounced hormonal sensitivity likely underlies the recalcitrant behavior previously described for P. peruviana under in vitro conditions [65].

Cotyledon explants consistently outperformed hypocotyls in terms of shoot regeneration frequency, number of shoots, shoot vigor and biomass accumulation, whereas hypocotyl explants exhibited a greater tendency toward callogenesis. This pattern is consistent with reports in other Solanaceae crops, in which cotyledons display higher organogenic competence while hypocotyls preferentially undergo callus formation [66,67]. The superior response of cotyledon explants can be attributed to their juvenile physiological status, lower degree of lignification, and a more favorable endogenous hormonal environment, in which cytokinins and abscisic acid contribute to early greening, enhanced photosynthetic capacity, and vegetative growth [68,69]. Nevertheless, the fact that hypocotyls function as highly competent explants in other plant species [30,70] highlights that explant performance is context-dependent and governed mainly by endogenous hormone levels and the expression of key morphogenic regulators such as CYCD3-1, STM, and WUS [60].

From a developmental perspective, the contrasting responses observed between cotyledon and hypocotyl explants in P. peruviana L. indicate the preferential induction of distinct organogenic pathways. Cotyledon explants predominantly followed a direct organogenesis route, as evidenced by the early formation of shoot buds with minimal callus development and the rapid establishment of morphologically normal shoots. This response is characteristic of juvenile tissues with high morphogenic competence, in which regeneration proceeds directly from the explant without an intervening callus phase, thereby minimizing extensive cellular dedifferentiation processes [71,72,73]. In contrast, the pronounced callogenesis observed in hypocotyl explants suggests a shift toward indirect organogenesis, in which shoot formation is preceded by callus proliferation and a dedifferentiation–redifferentiation sequence. This pathway is generally associated with greater cellular plasticity, but also with lower regenerative efficiency [71,74].

The differential behavior of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants observed in this study is consistent with reports in multiple plant species, where explant identity plays a decisive role in determining the favored organogenic route. In Brassica juncea, cotyledons were more effective in shoot regeneration, whereas hypocotyls exhibited a higher callogenic response but a slower induction of shoots [75]. Similarly, in Solanum melongena and species of the genus Capsicum, cotyledon explants showed significantly higher shoot regeneration frequencies than hypocotyls [76,77]. Conversely, studies in Vigna radiata and cucumber (Cucumis sativus) genotypes demonstrated that hypocotyls possess a high callogenic capacity but a reduced or delayed ability to regenerate shoots, depending on genotype and hormonal regime [78,79]. Nevertheless, exceptions have been reported in which hypocotyl explants also display substantial shoot regeneration, as observed in Bixa orellana, highlighting the strong influence of physiological and hormonal context on explant response [80].

The morphogenic behavior observed in the present study further reflects the well-documented dual action of thidiazuron (TDZ), which can promote either direct or indirect organogenesis depending on explant type, hormonal balance, and applied concentration [21,81]. In cotyledon explants, TDZ in combination with appropriate auxin concentrations promoted direct shoot organogenesis, suggesting that cytokinin-induced cell division remained spatially restricted and did not trigger widespread tissue dedifferentiation [82]. In contrast, the same hormonal conditions induced profuse callus formation in hypocotyl explants, revealing a higher sensitivity of this tissue to TDZ-induced hormonal imbalance and favoring an indirect organogenic pathway [71,74].

From a biotechnological standpoint, the distinction between direct and indirect organogenesis is particularly relevant. Direct organogenesis is generally preferred in micropropagation protocols due to its faster regeneration rates, higher efficiency, and reduced risk of somaclonal variation, as it avoids prolonged phases of callogenesis and cellular dedifferentiation [83,84]. In contrast, indirect organogenesis, although less efficient for shoot regeneration, allows greater cellular and metabolic reprogramming, increasing the likelihood of somaclonal variation and genetic alterations, but also enhancing physiological plasticity and the accumulation of secondary metabolites under specific culture conditions [74,85]. In this context, the results obtained in P. peruviana indicate that direct and indirect organogenesis represent alternative, explant-dependent developmental strategies regulated by hormonal interactions, and that their predominance reflects a trade-off between morphogenic efficiency and metabolic reprogramming.

Physiological responses further supported the strong dependence of morphogenesis on the explant. Cotyledon-derived shoots accumulated higher levels of chlorophylls and carotenoids, which were closely associated with superior regeneration performance, shoot vigor, and biomass production. Given the tight relationship between chlorophyll content, nitrogen status, and photosynthetic performance [86,87], photosynthetic pigments can be considered functional indicators of explant physiological competence. In contrast, hypocotyl explants exhibited lower pigment contents and reduced regenerative performance, accompanied by increased callogenesis. In several plant systems, reduced chlorophyll levels have been associated with metabolic reprogramming toward alternative pathways, including enhanced phenylpropanoid metabolism [88,89,90,91,92].

In this context, phenolic equivalents estimated by the Folin–Ciocalteu assay revealed a response axis that was partially independent of growth and morphogenesis. Although explant type alone did not significantly affect total phenolic content, auxin type was decisive, with IBA promoting higher phenolic levels than NAA. More importantly, phenolic accumulation was driven exclusively by the three-way interaction (Explant × Auxin × Auxin Concentration), indicating that secondary metabolite production responds to specific hormonal combinations rather than to linear effects of auxin alone, as reported in other in vitro plant systems [93,94,95]. The highest phenolic contents were achieved in cotyledon explants exposed to low IBA concentrations and in hypocotyl explants treated with high IBA doses.

It should be noted that the total phenolic content reported in this study was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu assay, a widely used method due to its lower cost, speed, and reproducibility, but which is not specific for polyphenols. This assay measures the reducing capacity of metabolites present in plant extracts; therefore, non-phenolic but oxidizable compounds, such as ascorbic acid, aromatic amines and amino acids, reducing sugars, and proteins, can react, overestimating the total phenolic content [96,97]. Thus, the values reported here should be interpreted as gallic acid equivalents reflecting relative differences between treatments, rather than absolute concentrations of individual phenolic compounds. It is important to note that all methanolic extracts of P. peruviana shoots were obtained and analyzed at the same time, using the same extraction protocol and analytical conditions, which allowed for comparison of the total phenol content between all treatments, with greater reproducibility, minimizing experimental errors. More selective chromatographic approaches, such as HPLC-based profiling, would be required to identify and quantify individual phenolic constituents and are proposed as a focus for future studies.

In the present study, total phenolic content ranged from 2.32 to 3.54 µg GAE mg−1 DM. Previous studies have reported that leaves represent the main site of phenolic accumulation in Physalis, often exceeding levels observed in fruits and calyces [98,99]. For Physalis peruviana, leaf phenolic contents of approximately 8.15 mg GAE g−1 DM have been reported [2], while optimized cultivation conditions and elicitor application can further increase these values [100]. Comparable foliar phenolic levels have also been reported for other Physalis species grown ex vitro, including P. chenopodifolia, 1.96 mg GAE g−1 DM [101]. Although substantially higher phenolic concentrations have been described in wild Physalis species [102], direct numerical comparison is constrained by differences in species and developmental stage. Nevertheless, these reports confirm that the phenolic levels observed in the present in vitro study fall within a biologically meaningful range for vegetative tissues undergoing active growth and morphogenesis.

However, not all treatments that promoted high phenolic accumulation simultaneously exhibited optimal morphogenic and physiological traits. Several treatments involving NAA and hypocotyl explants, although associated with elevated phenolic levels, were characterized by reduced shoot regeneration, lower vigor, decreased SFC index values, and enhanced callogenesis. In contrast, treatments combining IBA with cotyledon explants achieved a more favorable balance between phenolic production, regenerative capacity, and physiological quality. In this regard, the high phenolic levels observed in hypocotyl explants under certain hormonal combinations do not appear to reflect improved morphogenic or physiological performance, but rather a metabolically stressed state, as described for plant tissues exposed to abiotic stress [103,104,105].

Hypocotyl explants also exhibited lower regenerative competence, reduced photosynthetic pigment contents, and a greater tendency toward callogenesis, collectively indicating diminished growth and photosynthetic efficiency. Under such conditions, the diversion of metabolism toward phenolic compound synthesis may be interpreted as an antioxidant defense mechanism and a redox adjustment strategy, which is widely documented in plants subjected to abiotic stress [103,106,107].

The multivariate analyses revealed that morphogenic performance, physiological quality, and phenolic metabolism constitute partially decoupled yet interacting dimensions in the in vitro response of Physalis peruviana. Similar multidimensional responses have been reported in other in vitro systems, where growth, physiological status, and secondary metabolism respond differentially to in vitro culture conditions and plant growth regulators [108,109,110]. This integrative approach allowed the identification of treatment combinations that maximize regeneration while maintaining physiological quality and controlling phenolic accumulation.

PC1 was primarily associated with shoot regeneration and vegetative growth, whereas PC2 captured variation related to photosynthetic pigment composition and shoot vigor. This separation indicates that regenerative competence and physiological quality are not necessarily synchronized responses, as previously reported in several tissue culture studies [111,112]. In contrast, total phenolic content loaded predominantly on PC3, suggesting that phenolic metabolism represents a distinct biochemical dimension rather than a direct determinant of regenerative performance.

Phenolic accumulation in vitro has frequently been associated with stress-related metabolic responses, including oxidative stress and hormonal imbalance, particularly under auxin-rich culture conditions [113,114,115,116,117]. The orthogonal positioning of phenolic content relative to the main morphogenic axis supports the notion that increased phenolic production does not inherently enhance regeneration efficiency but may instead reflect treatment-dependent metabolic reprogramming.

The clustering analysis further supported this multivariate structure by grouping treatments according to their combined morphogenic, physiological, and biochemical profiles. Treatments grouped in Cluster 2 exhibited improved regenerative efficacy alongside heightened phenolic accumulation, a reaction typically linked to vigorous tissue proliferation in vitro conditions that impose greater metabolic demands on the explants [118,119]. In contrast, Cluster 3 comprised treatments combining high morphogenic competence with balanced physiological status and limited phenolic accumulation, reflecting a more stable in vitro response.

Within Cluster 3, the treatment using cotyledon explants cultured with 0.5 µM IBA and a constant concentration of 4.54 µM TDZ emerged as the optimal combination, displaying positive scores along the morphogenic axis (PC1), intermediate positioning along the physiological axis (PC2), and limited but detectable phenolic accumulation along PC3. Although several treatments within this cluster shared a similar multivariate pattern, this treatment showed the most balanced positioning across the three principal components, indicating that efficient shoot regeneration can be achieved without excessive metabolic stress, while maintaining physiological functionality and avoiding excessive phenolic accumulation.

These results demonstrate that optimal in vitro regeneration of Physalis peruviana is achieved under conditions that promote strong morphogenic responses while preserving physiological quality and maintaining phenolic metabolism within a controlled range. The integration of PCA and clustering analyses provides a robust framework to identify such optimal treatment combinations, highlighting the importance of balancing growth, physiology, and secondary metabolism during in vitro culture. In addition, the type of explant and the auxin–TDZ ratio used in this work to improve both in vitro propagation and the production of photosynthetic pigments and polyphenols can be used in subsequent studies to elucidate the abiotic factors that alter the metabolism of P. peruviana. The effect of abiotic elicitors on the concentration of specific phenolic compounds biosynthesized by this important medicinal species can be determined using more selective techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the in vitro response of Physalis peruviana L. explants cultured in TDZ-based systems is governed by specific interactions among explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration, which collectively shape morphogenic performance, physiological quality, and phenolic metabolism. Cotyledon and hypocotyl explants exhibited clearly differentiated multivariate responses, confirming that explant origin is a key determinant of regenerative competence and biomass accumulation under in vitro conditions.

Integration of morphogenic, physiological, and biochemical traits through PCA and clustering allowed the identification of treatment combinations that balance regeneration efficiency with physiological stability and controlled phenolic accumulation. Among all evaluated treatments, cotyledon explants cultured in a medium supplemented with 0.5 µM IBA and a constant concentration of 4.54 µM TDZ exhibited the most favorable multivariate profile, combining high shoot regeneration capacity, maintained photosynthetic pigment content, and moderate phenolic levels.

The multivariate approach applied here provides a robust framework for optimizing regeneration protocols while avoiding excessive metabolic stress, contributing to the development of efficient in vitro systems for both biomass production and secondary metabolite management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12020173/s1, Table S1: Significance of interaction effects among explant type (E), auxin type (A), and auxin dose (D) on morphogenic responses of Physalis peruviana L.; Table S2: Interaction effects of explant type, auxin type, and auxin dose on in vitro morphogenic responses of Physalis peruviana L.; Table S3: Main effects of explant type, auxin type, and auxin dose on morphogenic responses of P. peruviana; Table S4: Main effects of explant type, auxin type, and auxin concentration on total phenolic compound production of P. peruviana L.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.V. and M.O.-C.; methodology: S.M.-V. and C.N.V.; investigation: R.V. and E.H.; formal analysis: A.M.R.-R.; data curation: R.V. and S.M.-V.; writing—original draft: R.V., A.M.R.-R., S.M.-V. and C.N.V.; writing—review and editing, E.H. and M.O.-C.; Visualization: C.N.V.; supervision, A.M.R.-R.; project administration, E.H.; funding acquisition, M.O.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Vice-Rectorate for Research of the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas (UNTRM).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the project NativePlant-BioFung (Contract No. PE501092857-2024-PROCIENCIA), awarded to Anyela M. Ríos-Ríos, for supporting the processing and analysis of samples related to the quantification of photosynthetic pigments and phenolic compounds, including the provision of reagents and consumables required for these specific physiological and biochemical analyses. The authors also thank Jorge Alberto Condori Apfata, Head of the Molecular Biology Laboratory, for granting access to laboratory equipment, particularly the microplate reader, used exclusively for pigment and phenolic compound analyses. In addition, the authors acknowledge the Plant Tissue Culture Unit of the Laboratory of Plant Physiology and Biotechnology (FISIOBVLAB) for providing facilities and technical support for the in vitro culture experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coy-Barrera, E. Chapter 15—Chemistry and Biological Properties of Physalis Peruviana Leaf Extract; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 165–174. ISBN 978-0-443-15433-1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Teng, X.; Tian, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Chemical Composition Analysis and Antioxidant Activity Evaluation of Leaf, Calyx, and Fruit of Physalis peruviana L. Food Ferment. Ind. 2024, 50, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añibarro-Ortega, M.; Dias, M.I.; Petrović, J.; Mandim, F.; Núñez, S.; Soković, M.; López, V.; Barros, L.; Pinela, J. Nutrients, Phytochemicals, and In Vitro Biological Activities of Goldenberry (Physalis peruviana L.) Fruit and Calyx. Plants 2025, 14, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Y.; Chen, J. Effect of Different Agrobacterium Rhizogenes Strains on Hairy Root Induction and Analysis of Metabolites in Physalis peruviana L. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 305, 154431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, P.; Parra, F.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Chavera, G.F.S.; Parra, C. Chemical Characterization, Nutritional and Bioactive Properties of Physalis peruviana Fruit from High Areas of the Atacama Desert. Foods 2021, 10, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, P.; Alirezalu, A.; Khalili, S. A Comparative Study of Chemical Composition, Phenolic Compound Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Wild Grown, Field and Greenhouse Cultivated Physalis (P. alkekengi and P. peruviana). Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2025, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiancone, B.; Guarrasi, V.; Leto, L.; Del Vecchio, L.; Calani, L.; Ganino, T.; Galaverni, M.; Cirlini, M. Vitro-Derived Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Leaves and Roots as Source of Bioactive Compounds: Antioxidant Activity and Polyphenolic Profile. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 153, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Tariq, A.; Habib, S. Interactive Biology of Auxins and Phenolics in Plant Environment. In Plant Phenolics in Sustainable Agriculture; Lone, R., Shuab, R., Kamili, A.N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 117–133. ISBN 978-981-15-4890-1. [Google Scholar]

- Marchiosi, R.; dos Santos, W.D.; Constantin, R.P.; de Lima, R.B.; Soares, A.R.; Finger-Teixeira, A.; Mota, T.R.; de Oliveira, D.M.; Foletto-Felipe, M.d.P.; Abrahão, J.; et al. Biosynthesis and Metabolic Actions of Simple Phenolic Acids in Plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 865–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajguz, A.; Piotrowska-Niczyporuk, A. Biosynthetic Pathways of Hormones in Plants. Metabolites 2023, 13, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, J.; Truba, M.; Vasileva, V. The Impact of Auxin and Cytokinin on the Growth and Development of Selected Crops. Agriculture 2023, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, A.; Szewczyk, A.; Simlat, M.; Błażejczak, A.; Warchoł, M. Meta-Topolin-Induced Mass Shoot Multiplication and Biosynthesis of Valuable Secondary Metabolites in Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni Bioreactor Culture. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, S.P.; Bhawana, M. An Update on Biotechnological Intervention Mediated by Plant Tissue Culture to Boost Secondary Metabolite Production in Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakas, F.P. Efficient Plant Regeneration and Callus Induction from Nodal and Hypocotyl Explants of Goji Berry (Lycium barbarum L.) and Comparison of Phenolic Profiles in Calli Formed under Different Combinations of Plant Growth Regulators. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 146, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.M.; Khan, T.; Khan, M.A.; Ullah, N. The Multipotent Thidiazuron: A Mechanistic Overview of Its Roles in Callogenesis and Other Plant Cultures In Vitro. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 2624–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongmaneeroj, M.; Jamjumrus, S.; Agarum, R.; Sukkhaeng, S.; Promdang, S.; Homhual, R. Effects of Growth Regulators on Production of Bioactive Compounds from Clinacanthus nutans (Burm.f.) Lindau “Phaya Yo” Culture In Vitro. ScienceAsia 2023, 49, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, M.C.; Mok, D.W.S.; Turner, J.E.; Mujer, C.V. Biological and Biochemical Effects of Cytokinin-Active Phenylurea Derivatives in Tissue Culture Systems. HortScience 1987, 22, 1194–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.J.; Krishnaraj, S.; Saxena, P.K. Morphological and Physiological Changes during Thidiazuron-Induced Somatic Embryogenesis in Geranium (Pelargonium x Hortorum Bailey) Hypocotyl Cultures. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1996, 157, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Han, Y.; Wei, W.; Han, Y.; Yuan, J.; He, N. Transcriptome and Metabolome Analyses Reveal the Efficiency of In Vitro Regeneration by TDZ Pretreatment in Mulberry. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 310, 111678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.R.; Desai, N.S. Effect of TDZ on Various Plant Cultures. In Thidiazuron: From Urea Derivative to Plant Growth Regulator; Ahmad, N., Faisal, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 439–454. ISBN 978-981-10-8004-3. [Google Scholar]

- Erland, L.A.E.; Giebelhaus, R.T.; Victor, J.M.R.; Murch, S.J.; Saxena, P.K. The Morphoregulatory Role of Thidiazuron: Metabolomics-Guided Hypothesis Generation for Mechanisms of Activity. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, Q.; Liao, B.; Yu, K.; Huo, Y.; Meng, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Du, M.; Tian, X.; et al. Thidiazuron Promotes Leaf Abscission by Regulating the Crosstalk Complexities between Ethylene, Auxin, and Cytokinin in Cotton. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Debnath, P.; Singh, S.; Kumar, N. An Overview of Plant Phenolics and Their Involvement in Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Stresses 2023, 3, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Tak, Y.; Bhatia, S.; Kaur, H. Phenolics Biosynthesis, Targets, and Signaling Pathways in Ameliorating Oxidative Stress in Plants. In Plant Phenolics in Abiotic Stress Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zheleznichenko, T.; Veklich, T.; Kostikova, V. Effects of 6-Benzylaminopurine and Thidiazuron on In Vitro Regeneration and Antioxidant Content of Sorbaria pallasii (Rosaceae) Microshoots. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. e Nat. 2024, 35, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, O.A.; Okunlola, G.O.; Rufai, A.B.; Obisesan, I.A.; Adeyinka, A.; Wang, D.; Ogunkunle, C.O.; Jimoh, M.A. Foliar Application of Thidiazuron Alleviates Cd Toxicity by Modulating Stress Enzyme Activities and Stimulating Pigment Biosynthesis in Cajanus cajan (L.). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 2995–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigholizadeh, S.; Motafakkerazad, R.; Kosari-Nasab, M.; Movafeghi, A.; Mohammadi, S.; Sabzi, M.; Talebpour, A.-H. Influence of Plant Growth Regulators and Salicylic Acid on the Production of Some Secondary Metabolites in Callus and Cell Suspension Culture of Satureja sahendica Bornm. Acta Agric. Slov. 2021, 117, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhwan, A.; Acemi, A.; Özen, F. The Effects of Plant Growth Regulators on In Vitro Seedling Development in Verbascum bugulifolium and Thidiazuron-Induced Changes in Phenolic Substance Contents in Its Callus Tissues. Compr. Plant Biol. 2025, 49, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmoreigi, R.A.; El-Maaty, S.A.; Hassanen, S.A.; Aly Hussein, E.H. Effect of Explant Type and Growth Regulators on in Vitro Regeneration of Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Al-Amar Rootstock. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024, 160, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Ávila, A.; García-Fortea, E.; Prohens, J.; Herraiz, F.J. Development of a Direct In Vitro Plant Regeneration Protocol From Cannabis sativa L. Seedling Explants: Developmental Morphology of Shoot Regeneration and Ploidy Level of Regenerated Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, L.; Ricci, A.; Molesini, B.; Mezzetti, B.; Pandolfini, T.; Piunti, I.; Sabbadini, S. Efficient Protocol of de Novo Shoot Organogenesis from Somatic Embryos for Grapevine Genetic Transformation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1172758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Petri, C.; Burgos, L.; Alburquerque, N. Efficient In Vitro Shoot Regeneration from Mature Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Cotyledons. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 160, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, D.; Danielato, G.; Chastellier, A.; Saint Oyant, L.H.; Fanciullino, A.-L.; Lugan, R. Multi-Targeted Metabolic Profiling of Carotenoids, Phenolic Compounds and Primary Metabolites in Goji (Lycium spp.) Berry and Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Reveals Inter and Intra Genus Biomarkers. Metabolites 2020, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Gantait, S.; Mukherjee, E.; Gurel, E. Enhanced Somatic Embryogenesis, Plant Regeneration and Total Phenolic Content Estimation in Lycium barbarum L.: A Highly Nutritive and Medicinal Plant. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 25, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, A.; Chowdhury, K.; Boroujerdi, A.; El-Bakry, A. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Characterizes Metabolic Differences in Cymbopogon schoenanthus Subsp. Proximus Embryogenic and Organogenic Calli and Their Regenerated Shoots. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ Cult. 2022, 149, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaroshko, O.; Rakhmetov, D.; Kuchuk, M. V Effect of the Plant Growth Stimulant Zeatin on Regeneration Capacity of Some Physalis Species In Vitro Culture. J. VN Karazin Kharkiv Natl. Univ. 2020, 35, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Villalobos, K.; Chico-Ruíz, J. Inducción de Brotes y Raíces En Hipocotilos y Cotiledones de Physalis peruviana L. Utilizando 6-Bencilaminopurina y 2,4-Diclorofenoxiacético. Rev. Investig. Altoandinas 2020, 22, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.; Vigo, C.N.; Juarez-Contreras, L.; Oliva-Cruz, M. Development and Optimization of In Vitro Shoot Regeneration in Physalis peruviana Using Cotyledon Explants. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.; Vigo, C.N.; Guelac, M.; Huaman, E.; Oliva-cruz, M. Efficient and Cost-Effective Shoot Regeneration in Aguaymanto (Physalis peruviana L.) Using Meta-Topolin and 6-Benzylaminopurine Combinations. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Agsays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skała, E.; Wysokińska, H. In Vitro Regeneration of Salvia nemorosa L. from Shoot Tips and Leaf Explants. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2004, 40, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Ríos, A.M.; da Silva, J.V.S.; Fernandes, J.V.M.; Batista, D.S.; Silva, T.D.; Chagas, K.; Pinheiro, M.V.M.; Faria, D.V.; Otoni, W.C.; Fernandes, S.A. Micropropagation of Piper crassinervium: An Improved Protocol for Faster Growth and Augmented Production of Phenolic Compounds. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ Cult. 2019, 137, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The Spectral Determination of Chlorophylls a and b, as Well as Total Carotenoids, Using Various Solvents with Spectrophotometers of Different Resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, F.; Giménez, R.; Aubert, C.; Chalot, G.; Betrán, J.A.; Gogorcena, Y. Phenolic, Sugar and Acid Profiles and the Antioxidant Composition in the Peel and Pulp of Peach Fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 62, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, W.J. Practical Nonparametric Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 0471160687. [Google Scholar]

- de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulationtle; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastien, L.; Julie, J.; Francois, H. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, B.N.S.; Murch, S.J.; Saxena, P.K. Thidiazuron-Induced Somatic Embryogenesis in Intact Seedlings of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea): Endogenous Growth Regulator Levels and Significance of Cotyledons. Physiol. Plant. 1995, 94, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Abbasi, B.H.; Zeb, A.; Xu, L.L.; Wei, Y.H. Thidiazuron: A Multi-Dimensional Plant Growth Regulator. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 8984–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, S.L.; Joshi, A.; Kachhwaha, S.; Ochoa-Alejo, N. Chilli Peppers—A Review on Tissue Culture and Transgenesis. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, P.; Vaddadi, S.; Matam, P.; Shreelakshmi, S. V TDZ Induced Diverse in Vitro Responses in Some Economically Important Plants. In Thidiazuron: From Urea Derivative to Plant Growth Regulator; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sivanesan, I.; Song, J.Y.; Hwang, S.J.; Jeong, B.R. Micropropagation of Cotoneaster wilsonii Nakai—A Rare Endemic Ornamental Plant. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011, 105, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhnle, M.K.; Weber, G. Efficient Adventitious Shoot Formation of Leaf Segments of In Vitro Propagated Shoots of the Apple Rootstock M.9/T337. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 75, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, B.K.; Yu, C.Y.; Chung, I.-M. Direct Shoot Organogenesis and Assessment of Genetic Stability in Regenerants of Solanum aculeatissimum Jacq. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ Cult. 2012, 108, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.Z.; Bilal, M.; Hussain, J.; Shah, M.M.; Hassan, A.; Kwon, S.Y.; Ur-Rehman, S.; Ahmad, R. Robust Regeneration Protocol for the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Mediated Transformation of Solanum tuberosum. Pak. J. Bot 2016, 48, 707–712. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, J.; Jie, E.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Jiang, L.; Ahn, W.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Kim, S.W. Temporal and Spatial Expression Analysis of Shoot-Regeneration Regulatory Genes during the Adventitious Shoot Formation in Hypocotyl and Cotyledon Explants of Tomato (CV. Micro-Tom). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoog, F. Chemical Regulation of Growth and Organ Formation in Plant Tissue Cultured in Vitro. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1957, 11, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pernisová, M.; Klíma, P.; Horák, J.; Válková, M.; Malbeck, J.; Souček, P.; Reichman, P.; Hoyerová, K.; Dubová, J.; Friml, J.; et al. Cytokinins Modulate Auxin-Induced Organogenesis in Plants via Regulation of the Auxin Efflux. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3609–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclercq, J.; Sangwan-Norreel, B.; Catterou, M.; Sangwan, R.S. De Novo Shoot Organogenesis: From Art to Science. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.; Ljung, K. Auxin and Cytokinin Regulate Each Other’s Levels via a Metabolic Feedback Loop. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Barnwal, N.; Rai, G.K.; Bajpai, M.; Rai, P. In Vitro Propagation of Goldenberry (Physalis peruviana L.): A Review. Veg. Sci. 2019, 46, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, R.H.; Yesmin, S.; Hoque, M.I. Multiple Shoot Formation in Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plant Tissue Cult. Biotechnol. 2008, 16, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, B.D.; Jadhav, A.S.; Kale, A.A.; Chimote, V.P.; Pawar, S. V In Vitro Plant Regeneration in Brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) Using Cotyledon, Hypocotyl and Root Explants. Vegetos 2013, 26, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Hong, S.; Liang, Y.; Ren, B.; Zuo, J. Cytokinin Antagonizes Abscisic Acid-Mediated Inhibition of Cotyledon Greening by Promoting the Degradation of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 Protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, G.; Duque, P. Tailoring Photomorphogenic Markers to Organ Growth Dynamics. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Ismail, M.R.; Haque, M.S.; Shahidullah, S.M.; Uz-zaman, S. Regeneration Potential of Seedling Explants of Chilli (Capsicum annuum). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, O.J.; Beaty, R.M. Organogenesis. In Plant Tissue Culture Concepts and Laboratory Exercises; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasawa, K.; Takebe, T. Organogenesis In Vitro. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021, 73, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, P.; Desai, S.; Rafaliya, R.; Patil, G. Chapter 5—Plant Tissue Culture: Somatic Embryogenesis and Organogenesis; Chandra Rai, A., Kumar, A., Modi, A., Singh, M.B.T.-A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 109–130. ISBN 978-0-323-90795-8. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Kundu, S. Impact of Direct and Indirect Organogenesis in Agriculture. Agric. Re-Imagined Innov. Strateg. Sustain. Growth 2024, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Bano, R.; Khan, M.H.; Rashid, H.; Khan, R.S.; Munir, I.; Swati, Z.A.; Chaudhry, Z. Callogenesis and Organogenesis in Three Genotypes of Brassica Juncea Affected by Explant Source. Pak. J. Bot 2010, 42, 3925–3932. [Google Scholar]

- Sanatombi, K.; Sharma, G.J. In Vitro Plant Regeneration in Six Cultivars of Capsicum spp. Using Different Explants. Biol. Plant. 2008, 52, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayova, E.; Vassilevska-Ivanova, R.; Kraptchev, B.; Stoeva, D. Indirect Shoot Organogenesis of Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2012, 13, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutha, S.; Ganapathi, A.; Muruganantham, M. In Vitro Organogenesis and Plant Formation in Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ Cult. 2003, 72, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, S.; Velkov, N. In Vitro Plant Regeneration of Two Cucumber (Cucumis sativum L.) Genotypes: Effects of Explant Types and Culture Medium. Genetika 2014, 46, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimalan, R.; Giridhar, P.; Gururaj, H.B.; Ravishankar, G.A. Organogenesis from Cotyledon and Hypocotyl-Derived Explants of Japhara (Bixa orellana L.). Acta Bot. Croat. 2007, 66, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Faisal, M. Thidiazuron: From Urea Derivative to Plant Growth Regulator; Springer: Singapore, 2018; ISBN 9789811080043. [Google Scholar]

- Bhojwani, S.S.; Razdan, M.K. Cellular Totipotency. In Plant Tissue Culture: An Introductory Text; Springer: Delhi, India, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]