Abstract

Christmas tree growers are concerned with improving establishment of their plantations. Here, we report the results of a series of on-farm trials conducted with grower-cooperators in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) and Great Lakes (Michigan—MI) regions to determine the efficacy of treatments at planting on improving tree survival and growth in Christmas tree plantations. Cooperating growers planted species that were typical for each region (Fraser fir in the Great Lakes and Douglas-fir and noble fir in the PNW) and managed the plantings using standard cultural practices, aside from test treatments. Test treatments varied between locations and years but included wood chip mulch, shade blocks, an anti-transpirant, biochar, fertilizers, and various root dips including polymer gels, mycorrhizae, and bio-stimulants. Overall, treatments that directly modified the tree environment (i.e., mulch and shade blocks) provided the most consistent benefit to tree survival and growth. In Michigan, mulching increased survival by 5% on non-irrigated farms and increased second-year shoot growth by ~3 cm. In the PNW trials, mulching increased survival of noble fir seedlings more than Douglas-fir seedlings. Installing controlled release fertilizer packets at planting increased initial growth of Douglas-firs. Application of root dips prior to planting did not improve tree survival or growth relative to dipping tree roots in water (control). Based on our results, we conclude that treatments that conserve soil moisture (mulch) or reduce tree water loss (shade blocks) offer the most direct opportunity for growers to improve initial tree survival and growth.

Keywords:

mulch; shade blocks; root dips; mycorrhizae; hydrogel; transplant stress; Fraser fir; noble fir; Douglas-fir 1. Introduction

Christmas tree production is a major agricultural enterprise throughout several regions of North America. In the United States, 14.5 million Christmas trees are harvested annually from more than 10,000 farms [1]. U.S. Christmas tree production is largely concentrated in three regions, the Pacific Northwest, the Great Lakes region, and western North Carolina. Although species and specific production practices vary among regions, some concerns, particularly plantation establishment, apply to all growers. Nearly all conifers grown for Christmas trees in the U.S. are established by planting seedlings or transplants. Trees that do not survive are a direct loss to growers. In addition, when trees fail to survive, growers must either replant, resulting in additional costs for labor and planting stock, or face reduced returns due to fewer harvestable trees.

Plant moisture stress after planting (often referred to as transplant stress or transplant shock) can be a major limiting factor in the establishment of Christmas tree plantations [2]. Initial survival and growth of newly planted conifers is related to several factors, including weather immediately before and after planting, soil conditions, and planting stock quality [3,4,5]. Planting stock survival is an increasing concern to Christmas tree growers in light of events such as the 2021 heat dome in the Pacific Northwest [6] and predictions of increasing frequency of severe droughts associated with climate change [7,8]. A variety of techniques and products have been promoted by manufacturers and growers to mitigate transplant stress of conifer seedlings and improve transplant success. These include various root dips, shade blocks, and mulches [9,10].

Root dips used in conifer establishment include polymers, bio-stimulants, and mycorrhizae, applied alone or in various combinations. Polymer root dips are promoted to retain moisture in the root zone and prevent root desiccation before and after planting. Some studies have shown positive responses of transplants to root dips [11,12], although results vary, and some studies have shown negative effects [13]. Bio-stimulants include a range of products designed to enhance root growth after planting. These are often bio-based products that may include kelp extract, plant hormones, and/or nutrients [14,15]. Mycorrhizal root dips include inoculum of endo- and/or ectomycorrhizae. All genera that are commonly grown as Christmas trees in the U.S. (Abies, Picea, Pinus, Pseudotsuga) form ectomycorrhizal associations [16]. Off-the-shelf mycorrhizal inoculants are purported to improve root function of newly planted seedlings by augmenting mycorrhizal fungi that are native in the soil [17,18]. However, trials with artificial mycorrhizal inoculations in conifer plantations have yielded mixed results [19,20].

Interest in the use of organic mulches is increasing among growers and over one-third of Christmas tree growers responding to an interactive poll in a recent Michigan State University Extension webinar reported using mulch on their farms. Organic mulch can improve initial seedling survival and growth by reducing evaporation from the soil surface and reducing weed competition, resulting in increased soil moisture [9,10]. However, other studies of mulches for Christmas tree establishment have shown contrasting results. Surface application of compost as mulch had no net effect on the growth of blue spruce grown as Christmas trees [21]. Arthur and Young [22] compared effects of sawdust mulch and rubber tire mulch in Scots pine and eastern white pine Christmas tree plantations but found no difference in tree growth between mulched and non-mulched trees. Plastic mulching reduced growth of Scots pine Christmas trees [23].

In addition to approaches to improve below-ground conditions, artificial shading using shade blocks or shingles has been shown to reduce heat load and transpirational water loss of conifers in clear-cuts [24,25,26,27] and in regenerating the blast zone at Mount St. Helens [28]. Similarly, film-forming anti-transpirants can reduce seedling water loss and may potentially reduce tree stress [29]. More recently, forest regeneration specialists have investigated biochar as a means to improve soil water- and nutrient-holding capacity to improve tree performance [30], but to date the results with conifers have been mixed [31].

The cost of planting stock and labor for planting are among the largest operational expenses associated with producing Christmas trees [32], increasing the desire for growers to produce a salable tree from each transplant. Moreover, scarcity of fresh water and irrigation restrictions often limit the ability of growers to irrigate to improve crop survival and growth [33]. In order to evaluate the potential of various approaches to reduce transplant stress and improve tree survival and growth of Christmas trees in the Great Lakes region and the Pacific Northwest, we conducted a series of on-farm trials working with grower-cooperators in each region. The objectives of the trials were to identify treatments or combinations of treatments that would increase initial tree survival and growth and to provide recommendations to growers to improve plantation survival and growth.

2. Materials and Methods

We established trials in Michigan (2021, 2022, and 2023) and in the Pacific Northwest (2022 and 2023) (Table A1). In all cases, studies included 400–600 trees per location and were installed on operational Christmas tree farms using the growers’ planting stock and standard planting procedures and plantation culture, except as noted. For the Michigan studies, all trials were installed using bare-root 2 + 2 (2 years in seedling bed + 2 years in transplant bed; i.e., 4-year-old transplants) or plug + 2 (grown 1 year as plug + 2 years in transplant bed) transplants of Fraser fir (Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir.), which is typical for the Great Lakes region [34]. For the Oregon studies, all trials were installed using container-grown or bare-root noble fir (A. procera (Rehder)) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirbel) Franco) seedlings, which are commonly planted in the Pacific Northwest [35].

2.1. Michigan Studies

All trials were installed at each farm in a randomized split-plot design with root dips or related soil treatments as main plot effects and above-ground treatments as sub-plot treatments. The number of replications varied by study installation but included at least 20 replications of each treatment combination.

2.1.1. Michigan 2021 Trials

We established initial trials in spring 2021 at four locations: Sidney, MI (Korson’s Tree Farm), Gobles, MI (Wahmhoff Farms), Horton, MI (Gwinn’s Christmas Tree Farm), and Allegan, MI (Badger Evergreen Nursery). At each farm, we applied four root dip treatments (control, two polymer gels, and a polymer gel + bio-stimulant + mycorrhizae product) and five above-ground treatments (mulch, shade, mulch + shade, anti-transpirant, and control), resulting in twenty treatment combinations (Table A2). Fraser fir transplants (2 + 2 or plug + 2) were installed using the growers standard planting equipment and procedures. At all locations, trees were machine-planted. Immediately prior to planting, we dipped transplants in selected root dips, including an untreated control (water only) for at least 5 min to ensure roots were thoroughly coated. Excess product was gently shaken from the roots. We applied root dips by dipping seedling roots into each product mixed in 20 L plastic buckets per label-recommended rates (Figure 1). Care was taken to prevent cross-contamination between treatments when applying dips and during planting. Tree planters assessed trees immediately prior to planting and any damaged or excessively small trees were culled (typically less than 0.5% of trees). After the trees were planted, we applied mulch and shade treatments.

Figure 1.

Application of root dips prior to planting.

Trees were mulched to 8 cm depth in a 20 cm radius around each tree. Mulches consisted of ground wood chips or ground bark, depending on the farm. Mesh shade blocks (20 × 30 cm Mesh Envelopes, PacForest Supply Co., Springfield, OR, USA) were installed on the south side of trees (Figure 2). Each test consisted of 400–600 trees, depending on the location. Trees in the anti-transpirant treatment were sprayed to run-off with WiltPruf anti-transpirant immediately after planting using a 4 L hand-pump sprayer (Solo Model 211, Solo, Inc., Newport News, VA, USA). The treatment was re-applied in mid-July. Two of the farms (Sidney and Horton) provided supplemental irrigation via drip irrigation (approx. 2.5 cm of water per week in the absence of rainfall) while the other two farms (Gobles and Allegan) did not irrigate.

Figure 2.

Mulch and shade block treatment.

2.1.2. Michigan 2022 Trials

In 2022, we focused our investigations on farms that did not irrigate and also added smaller Christmas tree farms that market choose-and-cut Christmas trees. In addition to Gobles and Allegan, we added plots in Milford, MI, USA (Holiday Acres Tree Farm) and Grand Rapids, MI, USA (Ed Dunneback and Girls Farm Market). All planting procedures were the same as the 2021 trial except at Grand Rapids, where trees were planted by hand in furrows opened up with a tractor-mounted planting disk. Root dips included DieHardTM, MycoApply®, and SoilMoist®. After all trees were planted, we applied the post-planting treatments, which included mulch only, fertilizer only, mulch + fertilizer, and untreated control. Fertilized trees received 12 g of controlled release fertilizer as a top-dress (Osmocote Blend 18-5-12, 5-6 mo. release, ICL Specialty Fertilizers, Summerville, SC, USA). We standardized the mulch application using ground wood mulch (Best Natural Wood Mulch, Wood Ecology, Elk Mound, WI, USA) around each tree.

2.1.3. Michigan 2023 Trials

In 2023, we established plots on the same farms as 2022, and we continued to refine our treatments. For the fertilizer treatment, we used controlled release planting packets (BEST-PAKS® 20-10-5, J.R. Simplot Company, Boise, ID, USA). Trees were assigned at random to receive one of five root dip or subsurface treatments: control (water dip only), DieHardTM Ecto, MycoApply®, Best-Paks® fertilizer packet, or biochar application. The fertilizer packets were installed using a dibble bar to make a slit immediately next to the planting site for each tree (Figure 3). For biochar, we applied 0.5 L of commercially available medium grade biochar produced through slow pyrolysis (BiocharNow, Loveland, CO, USA). Biochar was surface applied in a 20 cm radius around each tree and was gently incorporated into the soil with a rake. All trees were subjected to surface treatments which included a 2 × 2 factorial (with or without wood chip mulch and with or without shade blocks).

Figure 3.

Using a dibble bar to install BestPak® fertilizer packets.

2.1.4. Assessments–Michigan Trials

For all three Michigan trials, we assessed tree survival and leader growth at the end of each season. Any trees that were killed or damaged by equipment or animal browsing were excluded from assessments. We collected current-year shoot samples at the end of each growing season for each of the Michigan trials for foliar nitrogen analysis. At each farm we collected a composite sample of shoots from at least 30 trees for each treatment combination.

In the 2021 study we measured shoot gas exchange (net photosynthesis (A) and transpiration (E)) on a subsample of trees using a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400XTLi-Cor Inc., Lincon, NE, USA). The photosynthesis system was equipped with a 0.25 L conifer chamber in which a portion of a current year’s shoot was included. The control systems on the unit were configured to 400 ppm of CO2 and a flow rate of 500 mL min−1.

Following establishment of the 2023 trials, southwestern Michigan experienced an extended drought period in May and June (Table A3) during which the MSU Enviroweather station in Allegan recorded a total of 13 mm of rainfall. Near the end of this drought period, we assessed volumetric soil moisture and predawn water potential (Ψw) at two of the farms in southwest Michigan (Gobles and Allegan). We assessed soil moisture at 0–15 cm depth using a portable Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) system (Trase System I, Soilmoisture Equipment Corp., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Predawn shoot Ψ was assessed using a portable pressure chamber (PMS Instrument Co., Albany, OR, USA). For both soil moisture and water potential, we measured a subsample of trees in the control and biochar plots.

2.2. Pacific Northwest Studies

2.2.1. Pacific Northwest 2022 Trials

We established trials at four locations: Cheshire, OR, USA (Stroda Brothers Christmas Trees), Mossyrock, WA, USA (Christmas Hill Tree Farm), Sublimity, OR, USA (McKenzie Tree Farms), and Mehama, OR, USA (BTN of Oregon). At Cheshire and Mossyrock, growers planted both noble fir and Douglas-fir. At Sublimity, the grower planted Douglas-fir, and at Mehama, the grower planted noble fir. At each farm, trials were installed as a 4 × 2 factorial of fertilizer/bio-stimulant (4 treatments) and mulch (2 levels, with or without). For the fertilizer/bio-stimulant treatments, trees were treated at planting with one of two combinations of liquid fertilizer and bio-stimulants (Table A4), fertilized with a controlled release fertilizer packet (BEST-PAKS® 20-10-5), or left unfertilized (control). The liquid products were sprayed onto the plant roots at a rate of 25 mL per tree as the trees were being hand planted (Figure 4). The liquid formulations were developed in cooperation with local representatives for the manufacturers and reflected products commonly used by growers in the region. The fertilizer packets were installed immediately after planting as described for the 2023 Michigan trials. Within each fertilizer/bio-stimulant plot, half of the trees were top-dressed with mulch as described previously.

Figure 4.

Application of treatment sprays to roots of seedlings at planting in Pacific Northwest trials.

2.2.2. Pacific Northwest Trials 2023

In spring 2023 noble fir seedlings were planted at three locations: Cheshire, OR (Stroda Bros. Christmas trees), Banks, OR (Schmidlin Farms), and Silverton, OR (Silver Bells Tree Farm). At Cheshire and Banks, the growers planted 1-0 plug seedlings and at Silverton the grower planted 3-0 bare-root seedlings. Following planting, we installed a 3 × 2 factorial design of surface treatments (biochar, fertilizer packet, or untreated control) and mulch (with or without). For the biochar treatment, 500 mL of medium grade biochar was surface applied in a 20 cm radius around each tree. Fertilizer packets and mulch were installed as described previously.

2.2.3. Assessments–PNW Trials

All trees were assessed in fall 2022. Trees were scored as 1 = alive or 0 = dead. Leader growth was measured on all living trees.

2.3. Analysis

All data were analyzed by analysis of variance using the PROC GLMMIX of SAS (SAS ver. 9.4, SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). ANOVA assumptions were checked by examining normal probability plots (normality) and Lavene’s test (heterogeneity of error variance). We analyzed data on leader growth and physiological parameters using the default (normal) distribution for PROC GLIMMIX. For survival data we specified a binomial distribution using the (dist = binomial link = logit) prompt in GLIMMIX. For the Michigan trials, data were analyzed as a split-plot design within sites with root dips as the main effects and above-ground treatments as sub-plot effects. Interactions of locations with main plot or sub-plot effects were not significant (p > 0.05); therefore, data for each year’s study were pooled across locations. The Pacific Northwest trials were installed in a factorial trial design within each site, with treatments crossed with mulch. Several interaction effects of the location and treatments were significant; therefore, all data were analyzed by location. For the PNW and Michigan analyses, Locations (i.e., farms) were analyzed as random effects. All other effects were considered fixed. For all trials, we used Tukey’s Studentized range test to separate means whenever significant treatment effects were indicated. In order to provide a summary of effects across trials, we constructed a table to indicate the factors that resulted in significant (p = 0.05) treatment effects and indicated whether the treatment effects were positive (+) or negative (−).

3. Results

3.1. Michigan Trials

3.1.1. 2021 Michigan Trials

First-year (2021) survival was excellent (99% or greater) on all farms. Survival declined over time with increased losses in the second year after planting (2022) (Table 1). None of the root dips tested increased (p > 0.05) survival compared to trees that were dipped in water only. Among the above-ground treatments, combining mulch application with shade blocks increased (p ≤ 0.05) cumulative leader growth when trees were not irrigated. On the non-irrigated farms, trees treated with anti-transpirant (WiltPruf) after planting had less total growth than trees in any other above-ground treatment except the control. Gas exchange measurements conducted in late summer in 2021 indicated that application of anti-transpirant reduced (p ≤ 0.05) transpiration relative to other above-ground treatments but also reduced (p ≤ 0.05) net photosynthesis (Table 2). Root treatments, in contrast, did not affect needle gas exchange.

Table 1.

Mean leader growth and survival of Fraser fir transplants planted at irrigated and non-irrigated farms in Michigan in 2021 with a combination of above-ground and root treatments at planting.

Table 2.

Mean Transpiration and net photosynthesis of Fraser fir transplants planted in Michigan in 2021 with a combination of above-ground and root treatments at planting.

3.1.2. 2022 Michigan Trials

As in 2021, none of the root treatments affected (p > 0.05) seedling growth or survival of trees planted in 2022 (Table 3). Mulch application increased tree survival averaged across all farms (Table 3). Application of controlled release fertilizer reduced overall tree survival (Table 3). Root dips did not affect (p > 0.05) cumulative leader growth, although trees treated with DieHard at planting had greater (p ≤ 0.05) leader growth than control trees in the second year after planting. Application of mulch increased (p ≤ 0.05) leader growth in the first and second year after planting, resulting in a 3 cm increase in total leader growth. Fertilization increased total leader growth by 2 cm, although it reduced overall survival.

Table 3.

Mean leader growth and survival of Fraser fir transplants planted at four farms in Michigan in 2022 with a combination of root dips, mulch, and fertilization at planting.

3.1.3. 2023 Michigan Trials

Mulch, either alone or in combination with shade, increased (p ≤ 0.05) tree survival compared to control plots that were not mulched (Table 4). The combination of mulching and shade increased leader growth relative to control trees. Soil and root treatments (biochar, DieHard, MycoApply, BestPaks) did not affect (p > 0.05) tree survival or leader growth compared to trees that were dipped in water before planting. There was no effect of soil/root treatment on predawn Ψw compared to trees that were dipped in water before planting. The combination of mulch and shade increased volumetric soil moisture compared to control (bare ground). Trees that received mulch had less moisture stress (higher predawn Ψw) than trees that were not mulched.

Table 4.

Mean leader growth, survival, soil moisture, and shoot water potential of Fraser fir transplants planted at four farms in Michigan in 2023 with a combination of soil or root treatment and mulch and shade at planting.

3.1.4. Foliar Nitrogen

Foliar nitrogen (N) concentrations were not affected (p > 0.05) by any treatment in any of the trials in Michigan. Foliar N differed (p ≤ 0.05) among farms; however, mean N concentrations were all above published sufficiency levels (foliar N = 1.5%) for fir Christmas trees as concentrations ranged from 1.6 to 2.2% across farms.

3.2. Pacific Northwest Trials

3.2.1. 2022 PNW Trials

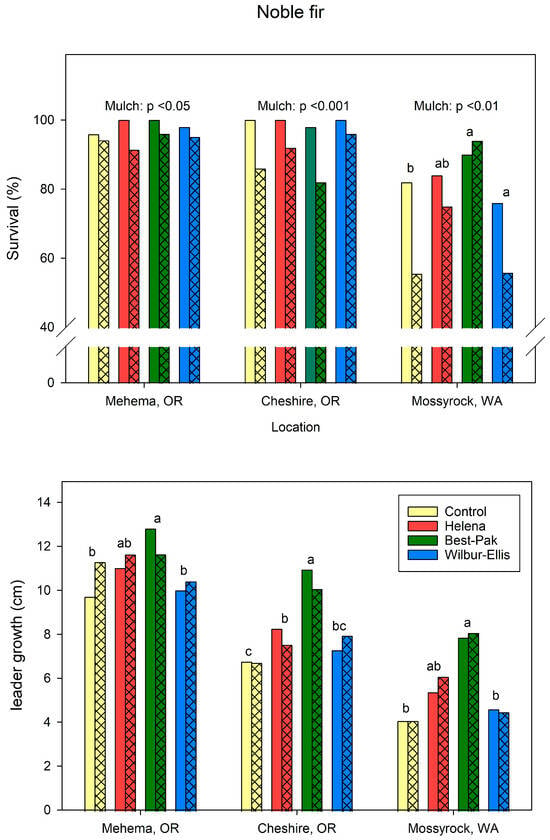

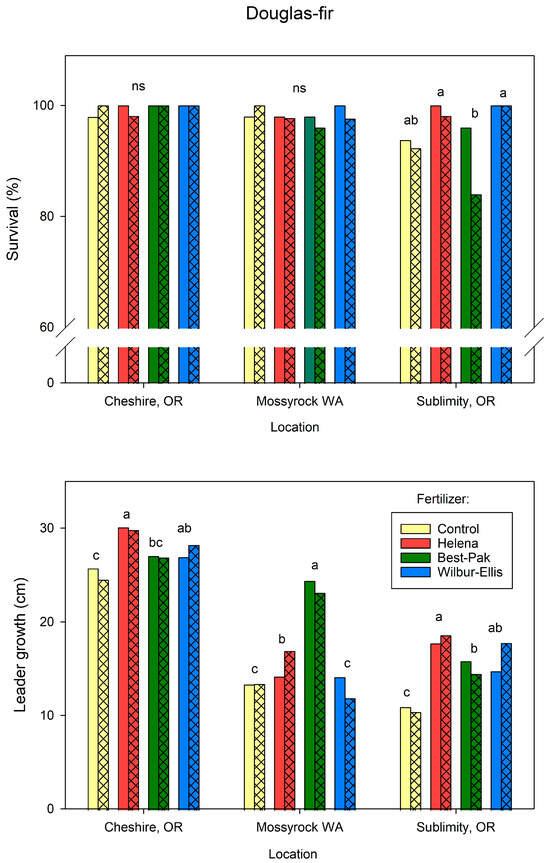

The response of seedling growth and survival to mulch and fertilizer treatments varied by species and by location (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Mean survival (top) and leader growth (bottom) of noble fir seedlings treated at planting with liquid fertilizer formulations (Helena and Wilbur-Ellis), controlled release fertilizer packets (BestPaks), or not fertilized (control). Open bars indicate means of mulched plots, cross-hatched bars indicate means of non-mulched plots. Means of fertilizer treatments within a location indicated by the same letter are not different at p = 0.05. n = 50 for each mulch × fertilizer combination at each location.

Figure 6.

Mean survival (top) and leader growth (bottom) of Douglas-fir seedlings treated at planting with liquid fertilizer formulations (Helena and Wilbur-Ellis), controlled release Fertilizer packets (BestPaks), or not fertilized (control). Open bars indicate means of mulched plots, cross-hatched bars indicate means of non-mulched plots. Means of fertilizer treatments within a location indicated by the same letter are not different at p = 0.05. ‘ns’ indicates no difference among any fertilizer treatment within a location. n = 50 for each mulch × fertilizer combination at each location.

For noble fir, addition of mulch increased (p ≤ 0.05) survival by 4.3 to 11.9%, depending on the location (Figure 5). Mulch did not affect (p > 0.05) leader growth of noble fir at any location. BestPaks fertilizer increased survival of noble firs at Mossyrock compared to unfertilized trees and trees that received the WE formulation. Fertilizer did not affect survival at other locations. BestPaks increased (p ≤ 0.05) leader growth relative to unfertilized trees and trees that received the WE formulation at all locations.

For Douglas-fir, mulch did not affect survival at any location (Figure 6). At Sublimity, Douglas-fir trees fertilized with the WE or H formulations had increased survival relative to trees that received the BestPaks. Otherwise, fertilization did not affect survival of Douglas-fir seedlings across the sites. The response of leader growth to fertilization varied across the sites. At Cheshire, H and WE had greater leader growth then the unfertilized control. At Mossyrock, trees fertilized with the Best-Paks had greater leader growth than all other treatments. At Sublimity, all fertilizer treatments had greater leader growth than non-fertilized trees.

3.2.2. 2023 PNW Trials

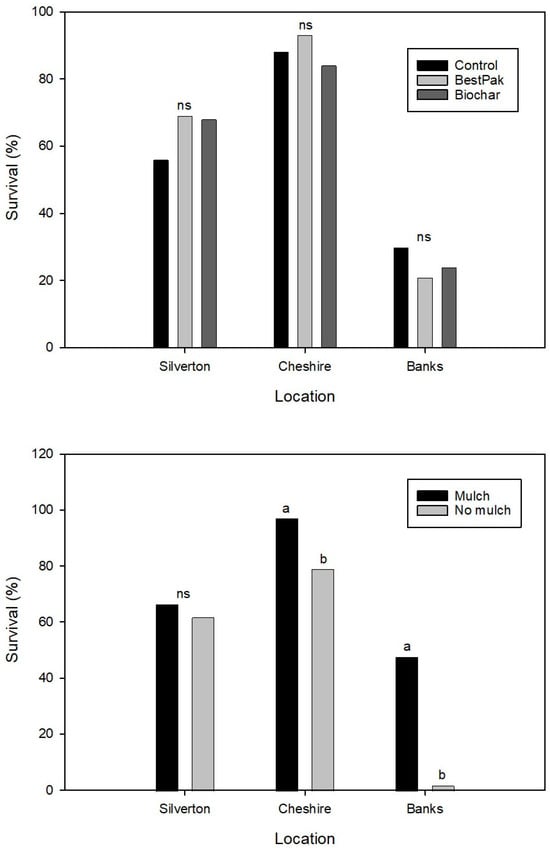

Survival varied among farms, with 88%, 64%, and 25% overall survival at Cheshire, Silverton, and Banks, respectively (Figure 7). Application of fertilizer packets (BestPaks) or biochar did not affect (p > 0.05) tree survival at any location. Mulch increased (p ≤ 0.05) survival at two of three farms (Cheshire and Banks). It is noteworthy that at Banks, nearly all the trees planted without mulch died (97% mortality), while survival increased to 45% when trees were mulched. Averaged across farms, average tree survival without mulch was 48%, whereas survival with mulch was 70%.

Figure 7.

Mean survival of noble fir trees planted in 2023 at three locations in the Pacific Northwest in response to application of controlled release fertilizer packet (BestPaks), biochar, or no treatment (control) at planting (n = 200 for each mean) (top) and in response to mulch application (bottom) (n = 300). Means within a location indicated by the same letter are not different at p = 0.05; ns indicates means within a location are not different.

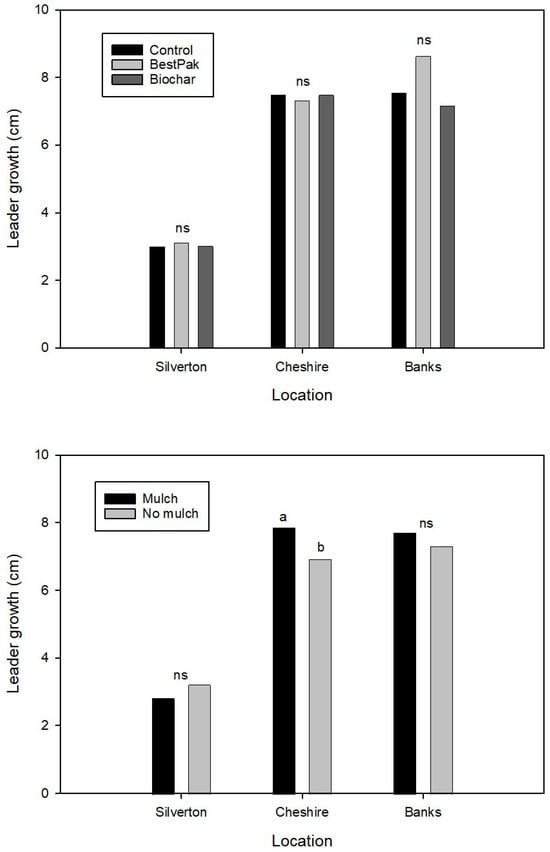

As with survival, application of fertilizer or biochar did not affect (p > 0.05) first-year leader growth (Figure 8). Mulch increased (p ≤ 0.05) leader growth at Cheshire. Averaged across farms, mulching increased (p ≤ 0.05) mean leader growth by 1 cm.

Figure 8.

Mean leader growth of noble fir trees planted in 2023 at three locations in the Pacific Northwest in response to application of controlled release fertilizer packet (BestPaks), biochar, or no treatment (control) at planting (top) and in response to mulch application (bottom). Means within a location indicated by the same letter are not different at p = 0.05; ns indicates means within a location are not different.

4. Discussion

Promoting transplant survival and rapid early plantation growth is a major concern for most Christmas tree producers. University extension personnel and consultants routinely field questions from growers on the best approaches to improve initial tree survival and growth. In this project we combined results from independent but related efforts in Michigan and the Pacific Northwest to determine the effects of various approaches to improve plantation establishment. Although differences in specific treatments and methods precluded a comprehensive statistical analysis, by pooling our efforts as a series of case studies, we were able to evaluate an array of techniques directed at increasing tree survival and early growth across a range of species in diverse environmental conditions (Table 5). Although specific results varied across trials, several trends were evident that can help guide growers as they consider methods to improve survival of their newly planted trees.

Table 5.

Summary of treatment effects for Christmas tree plantation establishment trials conducted in Michigan and in the Pacific Northwest. Treatment factors that resulted in a significant effect (p ≤ 0.05) on survival or growth are listed for each trial and whether the effect was positive (+) or negative (−).

4.1. Differences Between Regions

Differences in climate and production practices impacted overall results between the regions. In particular, tree survival was much more variable on the PNW sites than in Michigan. This likely reflects differences in stock types as Michigan grower-cooperators favored larger stock types (2 + 2 or plug + 2 transplants) with large root systems, whereas PNW cooperators planted plugs or bare-root seedlings. Moreover, weather at the Pacific Northwest sites reflected their Mediterranean climate, with summers that were much hotter and drier than those of the Michigan locations, which have a continental climate characterized by wetter summers and frequent summer thunderstorms (Table A3). Although differences in study designs across regions preclude a formal analysis, our results suggest the potential for larger impacts from treatments at planting in regions such as the Northwest, where prolonged summer droughts are common, or in particularly dry years in areas where drought is less frequent.

4.2. Modify the Physical Environment

Mulch and, to a lesser extent, shade provided the most consistent benefit to tree survival. At the Pacific Northwest sites, application of mulch at planting improved survival in five out of six individual trials with noble fir. In the 2023 trial at Banks, OR, application of mulch was the difference between almost certain seedling death (3% survival) and a 50/50 chance of survival. Although the survival response to mulch was less dramatic at the Michigan sites, overall survival was increased by mulch addition on non-irrigated farms. Mulch increased leader growth in several instances in the Michigan trials and at Chesire in the 2023 Oregon trials. Mulch provides multiple benefits that can aid tree survival and growth. Mulch can conserve soil moisture, moderate soil temperature, and suppress weeds. Cregg et al. [10] found that wood chip mulch increased diameter and shoot growth of newly planted Fraser firs compared to similar plots that were not mulched. The increase in growth was attributed to increased soil moisture associated with reduced surface evaporation and improved weed control. Mulch also modulated soil temperatures, with midday soil temperatures up to 10 degrees C cooler under mulch than under bare ground. In a landscape trial, wood- and bark-based mulches increased soil moisture at 0–15 cm depth compared to similar plots that were not mulched [36]. Shade blocks can also aid in reducing tree stress, presumably by moderating temperatures and reducing tree water loss via transpiration. Landgren et al. [9] found that shade blocks increased survival of newly planted noble fir seedlings by 15–20% when used in combination with other treatments. It should be noted, however, that increases in height growth associated with shade blocks could also be associated with shade avoidance responses [37,38]. We acknowledge that this effect cannot be separated from moisture stress impacts based on our current data.

4.3. Root Dips and Anti-Transpirant Were Ineffective

A consistent finding in the Michigan trials was that root dips did not improve growth or survival relative to trees that were dipped in water only before planting. Bates et al. [39] compared post-transplant survival and tree quality rating of transplants of four species (Fraser fir, blue spruce, concolor fir, and Douglas-fir) that were dipped in one of three root treatments (BioPlex, Roots, LiquaGel) before planting. None of the treatments increased growth or tree rating compared to trees dipped in water only. The root dips used in the current trials contained polymer gels, bio-stimulants, and mycorrhizal inoculum, either separately or in various combinations. Each of these additives has the potential to increase root establishment and improve plant performance. Polymer hydrogels can protect roots from desiccation during handling and planting and are also thought to promote root–soil contact [13]. However, a review found that planting trials with hydrogels yielded negative, positive, and neutral responses [13]. Hydrogels are sometimes viewed as insurance against root desiccation during tree planting [40]. Nonetheless, in the current trial, we observed no benefit although, in some cases, little or no rain fell in the weeks immediately after planting. Similarly, in the current project, products containing mycorrhizae and/or bio-stimulants did not improve transplant survival or tree growth. Bio-stimulants, which include a range of products containing humic or fulvic acids, beneficial bacteria or fungi, and plant extracts may improve plant survival and/or growth, but results are often variable [41].

In Christmas tree plantations and nurseries, artificial inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi may be ineffective due to various factors including poor spore condition, low spore counts, selection of unsuitable inoculum for the host species or extensive colonization of tree roots by native mycorrhizae [42]. In the current trials, we used fresh commercial inoculum and followed manufacturer’s recommended inoculation protocols. This suggests that conditions should have been suitable for successful inoculation. It is possible that trees were already mycorrhizal. For example, in a trial in conifer nurseries in Michigan, including nurseries that supplied some of the stock for the current trials, Renick [43] found that native mycorrhizae predominated after artificial inoculation, even when nursery beds had been fumigated with methyl bromide prior to sowing seeds. Thus, conifer transplants are likely to be mycorrhizal when they come from the nursery or may be quickly infected by spores of ubiquitous native mycorrhizae.

The film-forming anti-transpirant product used in the 2021 Michigan trial (WiltPruf) reduced transpiration but also interfered with photosynthetic gas exchange, resulting in reduced growth. Reductions in transpiration could also limit transpirational cooling of needles under hot, sunny conditions and could potentially contribute to direct high temperature injury to needles and shoots [44].

4.4. Fertilization at Planting May or May Not Help

University extension guidelines typically recommend that Christmas tree growers avoid nitrogen fertilization in the year of planting [45,46]. The rationale for avoiding fertilization after planting is two-fold. First, seedlings and transplants usually have high nutrient contents based on fertilization at the nursery and are unlikely to respond to additional N. Second, water stress is generally assumed to be the primary limiting factor as trees re-establish root–soil contact following transplanting. In the current project we found a range of responses to fertilization, which may be due to fertilizer application method and/or site conditions. In Michigan, top-dressing transplants with controlled release fertilizer increased first-year mortality but increased growth for the trees that survived. This suggests that the fertilizer may have initially induced an osmotic stress, but the additional nutrients were beneficial for trees that survived the stress. At the PNW sites, in contrast, fertilizer had little, or a slightly positive, effect on survival. At these sites, fertilization at planting increased first-year leader growth in several instances, particularly the application of controlled release fertilizer packets for noble fir. We speculate that the growth response of the trees to the fertilizer products in the PNW trials was due to nutrient enhancement and not the additional additives in the WE and H formulations, given that no single product was superior for Douglas-fir, and the product that yielded the greatest growth increase for noble fir (BestPaks) did not contain any bio-stimulants.

4.5. Biochar: Too Little or Too Early to Tell?

Biochar can improve an array of soil properties including cation exchange capacity, water holding capacity, and soil biological activity [47]. However, conifers are much less responsive to biochar addition than hardwood trees [48]. This may reflect increases in soil pH associated with biochar application on conifers that prefer acidic soils [49]. In our current trials we did not observe survival or growth responses to biochar in the year of planting. It is unclear if this reflects an offsetting of positive and negative effects on soil properties or if biochar effects will take longer to manifest. Moreover, the amount of biochar applied in this trial (0.5 L per tree over a 20 cm radius of soil surface) equates to an incorporation rate of approximately 2.5% (vol:vol), assuming a rooting depth of 15 cm for newly planted trees. This is well below the 5–10% incorporation rate recommended for newly planted landscape trees [50].

5. Conclusions

Initial tree survival and growth is critical to establishment of Christmas tree plantations. Producers in North America and Europe are continually searching for techniques to improve establishment and are frequently confronted with claims of manufacturers of a myriad of products purported to dramatically increase survival and growth. In this project, root dips and additives that contain polymer gels, bio-stimulants, or mycorrhizal inoculum did not improve initial tree growth or survival compared to dipping trees in water before planting. In contrast, techniques that directly modified the growing environment by improving moisture availability (mulch) or reduced water loss (shade) were the most effective in improving tree establishment. Although our trial conditions included an array of locations and environments, results could vary in other environments. Nonetheless, we encourage Christmas tree growers and others concerned with successfully establishing conifers (e.g., landscape nurseries, foresters) to approach root dips and soil amendments with healthy skepticism. Our results suggest that efforts directed toward improving the physical environment to conserve soil moisture and reduce tree water loss are more likely to pay positive dividends.

Given that these case studies included a wide array of potentially interacting factors, they also suggest several lines of investigation for continued research. In particular, the potential benefits and negative impacts of fertilization at planting need to be better understood. Extension guidelines typically discourage fertilization in the establishment year; however, we observed improved survival and growth in some cases. The negative impact of controlled-release fertilizer (CRF) applied as a top-dressing was unexpected and defies an obvious explanation as trees in container nurseries are routinely fertilized with greater amounts of CRF without ill effect. A comprehensive investigation of CRF would be useful to determine their utility for Christmas tree producers. Similarly, a systematic investigation of biochar including varying rates and types of biochar would be useful, including assessments of biochar impacts on soil chemical and physical properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C. and C.L.; methodology, B.C., C.L., J.K. and R.J., analysis, R.J. and B.C.; investigation, C.L., J.K., R.J. and B.C.; resources, C.L. and B.C.; data curation, R.J. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C.; writing—review and editing, C.L., J.K. and R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Michigan State University Project GREEEN, the Real Christmas Tree Board Research Fund, Michigan Christmas Tree Association Research Fund, and the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development Horticulture Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank our grower-cooperators, Mike Gwinn, Rex Korson, Kevin Mohrland, Dan Wahmhoff, Kyle Mattingly, Suanne Dunneback, Kirk Stroda, Tyler Stone, Juan Garcia, John Burton, Casey Grogan, and Mark Schmidlin for their assistance in plot installation and maintenance. We thank student research assistants Noah Dressander, Anna Dunnebacke, Claire Komarzec, Kenna Kline, Amy MacLaren, and Rebecca Myatt for their assistance with plot installation and data collection. We acknowledge ICL Specialty Fertilizers, Mycorrhizal Applications, Helena Agri-Enterprises, LLC, Wilbur-Ellis Company LLC, and J.R. Simplot Company for in-kind product contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of initial tree heights, treatments, and experimental designs for Michigan and Pacific Northwest Christmas tree establishment trials.

Table A1.

Summary of initial tree heights, treatments, and experimental designs for Michigan and Pacific Northwest Christmas tree establishment trials.

| Michigan 2021 | ||||

| Locations | Soil texture | Mean (SE) tree height (cm) | Root dip * (main plot) | Above-ground (sub-plot) |

| I Sidney I Horton Allegan Gobles | Sandy loam Sandy loam Sandy loam Loamy sand | 35.0 (0.31) 31.8 (0.34) 29.4 (0.21) 34.0 (0.24) | Control (water) DieHardTM SoilMoistTM Roots TerraSorbTM | Control (no treatment) Mulch Shade block WiltPruf anti-transpirant) Mulch + Shade |

| Michigan 2022 | ||||

| Locations | Mean (SE) tree height (cm) | Root dip * (main plot) | Above-ground (sub-plot) | |

| Milford Grand Rapids Allegan Gobles | Sandy loam Loamy sand Sandy loam Loamy sand | 40.4 (0.39) 39.4 (0.45) 27.2 (0.28) 34.7 (0.24) | Control (water) DieHardTM SoilMoistTM MycoApply® Ecto | Control Mulch Fertilizer Mulch + Fertilizer |

| Michigan 2023 | ||||

| Locations | Mean (SE) tree height (cm) | Below-ground (main plot) | Above-ground (sub-plot) | |

| Milford Grand Rapids Allegan Gobles | Sandy loam Loamy sand Loam Loamy sand | 29.0 (0.29) 30.7 (0.47) 32.5 (0.32) 34.7 (0.30) | Control (water) DieHardTM MycoApply® Ecto BEST PAKS® fertilizer packet Biochar | Control (no treatment) Mulch Shade block Mulch + Shade |

| Pacific Northwest 2022 | ||||

| Locations | Mean (SE) tree height (cm) Douglas-fir, noble fir | Fertilizer product ** | Mulch | |

| Cheshire, OR Sublimity, OR Mossyrock Mahema, OR | Loam Silty clay loam Silt loam Cobbly loam | 14.7 (0.18) 13.9 (0.20) 30.3 (0.34) 21.7 (0.17) 22.4 (0.17) 16.6 (0.24) | Control BEST PAKS® fertilizer packet Helena Wilbur-Ellis | With Without |

| Pacific Northwest 2023 | ||||

| Locations | Mean (SE) tree height (cm) | Soil treatment | Mulch | |

| Silverton, OR Cheshire, OR Banks, OR | Silty clay loam Loam Silt loam | 25.7 (0.46) 13.1 (0.22) 15.2 (0.37) | Control BEST PAKS® fertilizer packet Biochar | With Without |

Table A2.

Root dips and soil treatments applied in Christmas tree establishment trials installed in Michigan 2021–2023.

Table A2.

Root dips and soil treatments applied in Christmas tree establishment trials installed in Michigan 2021–2023.

| Study: Michigan 2021 | ||

| Product (Manufacturer) | Composition | Rate |

| DIEHARDTM Ecto Root Dip (Horticultural Alliance, Sarasota, FL, USA) | 88% Copolymer of Acrylamide/Potassium Acrylate; 2% Yucca Schidigera; 4% Humic Acids; 2% Kelp Extract; 0.33% Microbes Ectomycorrhizae, Scleroderma, Bacillus, Trichoderma, etc.); 0.2% K2O; 0.00061% Mo | 9.0 g/L H2O |

| SoilMoistTM Fines (JRM Chemical Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA) | 99.7% Crosslinked Polyacrylamide; 0.3% inert | 5.3 g/L H2O |

| Roots® Terra-Sorb® fine planting gel (LebanonTurf, Lebanon, PA, USA) | 93% Potassium Polyacrylate; 7% water | 6.0 g/L H2O |

| Control | Water | |

| Study: Michigan 2022 | ||

| DIEHARDTM Ecto Root Dip | Same as above | 9.0 g/L H2O |

| MycoApply® Injector Ecto (Mycorrhizal Applications Grants Pass, OR, USA) | 18.72% Ectomycorrhizal Fungi and Humic Acids; 81.28% inert | 0.25 g/L H2O |

| SoilMoistTM Fines | Same as above | 5.3 g/L H2O |

| Control | ||

| Study: Michigan 2023 | ||

| DIEHARDTM Ecto Root dip | Same as above | 9.0 g/L H2O |

| MycoApply® Injector Ecto | Same as above | 0.25 g/L H2O |

| BEST PAKS® 20-10-5 fertilizer packet (Simplot Professional Products, Lathrop, CA, USA) | 20% N, 10% P2O5, 5% K2O, 2% Ca, 2% Mg, 3% S, 0.25% Cu, 0.90% Fe, 0.25% Mn, 0.002% Mo, 0.15% Zn | One 10 g packet/tree |

| Biochar (Biochar Now, LLC, Loveland, CO, USA) | Medium-grade biochar | 500 mL/tree |

| Control | Water | |

Table A3.

Rainfall and temperatures for Michigan study sites 2021–2023.

Table A3.

Rainfall and temperatures for Michigan study sites 2021–2023.

| 2021 | |||||

| Location (Station) | Total Rainfall Season (1 April–30 September) | Summer Rainfall 1 June–31 Auguest | Average Summer Max Temp | Max Temp | Longest Period with No Rainfall (Days) |

| Allegan, MI, USA (Badger) | 425.4 | 328.2 | 28.0 | 33.4 | 11 |

| Horton, MI, USA (Gwinn) | 631.4 | 442.7 | 28.3 | 33.6 | 9 |

| Sidney, MI, USA (Korson) | 545.8 | 352.8 | 27.7 | 33.0 | 11 |

| Gobles, MI, USA (Wahmhoff) | 529.3 | 403.6 | 27.9 | 33.2 | 11 |

| 2022 | |||||

| Location (Station) | Total Rainfall | Summer Rainfall | Average Summer Max Temp | Max Temp | Longest Period with No Rainfall (Days) |

| Allegan, MI, USA (Badger) | 546.3 | 273.3 | 27.2 | 36.1 | 8 |

| Grand Rapids, MI, USA (Dunneback) | 518.9 | 276.1 | 26.5 | 33.2 | 8 |

| MI, USAlford, MI, USA (Holiday) | 409.7 | 257.1 | 27.1 | 34.4 | 8 |

| Gobles, MI, USA (Wahmhoff) | 469.1 | 213.4 | 27.4 | 35.0 | 9 |

| 2023 | |||||

| Location (Station) | Total Rainfall | Summer Rainfall | Average Summer Max Temp | Max Temp | Longest Period with No Rainfall (Days) |

| Allegan, MI, USA (Badger) | 332.0 | 205.2 | 26.8 | 34.2 | 23 |

| Grand Rapids, MI, USA (Dunneback) | 333.0 | 223.0 | 26.5 | 33.0 | 23 |

| MI, USAlford, MI, USA (Holiday) | 556.8 | 391.4 | 25.6 | 31.9 | 22 |

| Gobles, MI, USA (Wahmhoff) | 376.2 | 260.6 | 26.8 | 33.4 | 22 |

Table A4.

Rainfall and temperatures for PNW study sites 2022–2023.

Table A4.

Rainfall and temperatures for PNW study sites 2022–2023.

| 2022 | |||||

| Location (Station) | Total Rainfall Season (1 April–30 September) | Summer Rainfall 1 June–31 Auguest | Average Summer Max Temp | Max Temp | Longest Period with No Rainfall (Days) |

| Cheshire, OR, USA (Eugene) | 278.9 | 70.3 | 25.6 | 38.9 | 33 |

| Mossyrock, WA, USA (Olympia) | 329.9 | 80.8 | 25.5 | 37.2 | 34 |

| Sublimity, OR, USA (Salem) | 323.3 | 76.2 | 28.6 | 39.4 | 25 |

| Mehama, OR, USA (Salem) | 323.3 | 76.2 | 28.6 | 39.4 | 25 |

| 2023 | |||||

| Location (Station) | Total Rainfall | Summer Rainfall | Average Summer Max Temp | Max Temp | Longest Period with No Rainfall (Days) |

| Cheshire, OR, USA (Eugene) | 180.6 | 10.4 | 29.8 | 40.6 | 35 |

| Banks, OR, USA (Portland) | 230.4 | 46.5 | 28.8 | 42.2 | 47 |

| Silverton, OR, USA (Silverton) | 246.6 | 31.8 | 27.3 | 39.4 | 36 |

Source: NOAA via Climate Data Online Search (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/search; accessed on 14 December 2025).

Table A5.

Products/treatments for 2022 Pacifc Northwest trials.

Table A5.

Products/treatments for 2022 Pacifc Northwest trials.

| Company/ Treatment Code | Products | Product Rate (L/ha) | Application Rate (L/ha/3700 Trees) | Amount per Tree (mL) | Notes |

| Helena/H | Nucleus 0-0-21-13 Derived from potassium thiosulfate 20% product 1 | 18.7 | 94 | 25.2 (10.6 mL products + 14.6 mL water) | All Helena products combined and applied together as a solution |

| Nucleus Ortho-Phos 8-24-0 Derived from Ammonium phosphate and Iron EDTA 20% product 1 | 18.7 | ||||

| KickStand RTU 4-13-3 Derived from ammonium polyphosphate, potassium phosphate, phosphoric acid and seaweed extract (Ascophyllum nodosum) | 2.3 | Not used at Cheshire sites | |||

| Wilbur-Ellis/WE | Puric Prime 1-0-2 12% Derived from ammonium humate, potassium humate and Leonardite | 0.6 | 94 | 25.2 (1 mL products +24.2 mL water) | All Wilbur-Ellis products combined and applied together as a single solution |

| Nutrio Unlock: blend of soil-enhancing bateria Rhodopseudomonas palustris, Bacillus brevis, Bacillus licheniformis, Streptomyces griseus, Bacillus megaterium, Rhodococcus rhodochrous, Lactobacillus plantarum. | 1.2 | ||||

| Till-it Bluezone Max 6-24-6 | 1.8 | ||||

| Tricoderma-propriatary benifical fungi | 1.2 mL | ||||

| Simplot/S | Best Paks 20-10-5 CRF 12 m | 1 bag per seedling | |||

| Wood chip mulch (tree waste) | Approx. 8 L/tree |

1 These products came from company as a pre-mixed diluted solution.

References

- USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2022 Census of Agriculture; Publication AC-22-A-51; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Hanslin, H.M.; Fløistad, I.S.; Hovstad, K.A.; Sæbø, A. Field establishment of Abies stocktypes in Christmas tree plantations. Scan. J. For. Res. 2020, 35, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, S.C. Importance of root growth in overcoming planting stress. New For. 2005, 30, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, S.C. Seedling Establishment on a Forest Restoration Site. Reforesta 2018, 6, 110–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.R.; Marshall, J.D.; Dumroese, R.K.; Davis, A.S.; Cobos, D.R. Seedling establishmentand physiological responses to temporal and spatial soil moisture changes. New For. 2016, 47, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Northwest Climate Hub Northwest Heat Dome: Causes, Impacts and Future Outlook. 2021. Available online: https://www.climatehubs.usda.gov/hubs/northwest/topic/2021-northwest-heat-dome-causes-impacts-and-future-outlook (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Bendorf, J.; Lindberg, B.; Cregg, B.; McCullough, D.; Chastagner, G.; Nowatzke, L.; Todey, D.; Parker, S. Climate Change Impacts on Christmas Tree Production in the Midwestern Region; Bulletin E3489; Michigan State University Extension: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/climate-change-impacts-on-christmas-tree-production-in-the-midwestern-region (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Zhao, C.; Brissette, F.; Chen, J.; Martel, J.L. Frequency change of future extreme summer meteorological and hydrological droughts over North America. J. Hydrol. 2020, 584, 124316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgren, C.; Kowalski, J.; Cregg, B. Can treatments at planting improve noble fir seedling survival? USDA For. Serv. Tree Plant. Notes 2021, 64, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cregg, B.M.; Nzokou, P.; Goldy, R. Growth and physiology of newly planted Fraser fir (Abies fraseri) and Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens) Christmas trees in response to mulch and irrigation. Hortscience 2009, 44, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, A.; Stanton, J. Polymer root dip increases survival of stressed bareroot seedlings. North. J. Appl. For. 1993, 10, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, S. Effects of root-coating with the polymer Waterlock on survival and growth of drought-stressed bareroot seedlings of white spruce (Picea glauca (Moench) Voss) and red pine (Pinus resinosa Ait.). USDA For. Serv. Tree Plant. Notes 1986, 37, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, J.W. Use of hydrogels in the planting of industrial wood plantations. South. For. A J. For. Sci. 2017, 79, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Rayirath, U.P.; Subramanian, S.; Jithesh, M.N.; Rayorath, P.; Hodges, D.M.; Critchley, A.T.; Craigie, J.S.; Norrie, J.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants of plant growth and development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B. Five years of Irish trials on biostimulants: The conversion of a skeptic. In National Proceedings: Forest and Conservation Nursery Associations; RMRS-P-33; Riley, L.E., Dumroese, R.K., Landis, T.D., Eds.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2004; pp. 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, R.; Trappe, J.M. Patterns of ectomycorrhizal host specificity and potential among Pacific Northwest conifers and fungi. For. Sci. 1982, 28, 423–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.A. Outplanting performance of mycorrhizal inoculated seedlings. In Concepts in Mycorrhizal Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 223–301. [Google Scholar]

- Rudawska, M.; Leski, T.; Aučina, A.; Karliński, L.; Skridaila, A.; Ryliškis, D. Forest litter amendment during nursery stage influence field performance and ectomycorrhizal community of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) seedlings outplanted on four different sites. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 395, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffle, J.W.; Tinus, R.W. Ectomycorrhizal characteristics, growth, and survival of artificially inoculated ponderosa and Scots pine in a greenhouse and plantation. For. Sci. 1982, 28, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parladé, J.; Pera, J.; Alvarez, I.F. Inoculation of containerized Pseudotsuga menziesii and Pinus pinaster seedlings with spores of five species of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 1996, 6, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhart, E.; Hartl, W. Mulching with compost improves growth of blue spruce in Christmas tree plantations. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2003, 39, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.A.; Wang, Y. Soil nutrients and microbial biomass following weed-control treatments in a Christmas tree plantation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, W.J.; Hensley, D.L.; Wiest, S.; Gaussoin, R.E. Relay-intercropping muskmelons with Scotch pine Christmas trees using plastic mulch and drip irrigation. HortScience 1993, 28, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgerson, O.T. Effects of alternate types of microsite shade on survival of planted Douglas-fir in southwest Oregon. New For. 1989, 3, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgerson, O.T.; Bunker, J.D. Alternate types of artificial shade increase survival of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco) seedlings in clearcuts. USDA For. Serv. Tree Plant. Notes 1985, 36, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, G.J. The effects of artificial shade on seedling survival on Western Cascade harsh sites [USA]. USDA For. Serv. Tree Plant. Notes 1982, 33, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Oester, P.T. Ten-year response of western larch and Douglas-fir seedlings to mulch mats, sulfometuron, and shade in northeast Oregon. USDA For. Serv. Tree Plant. Notes 2008, 53, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, S.E. Post-Eruption Species Selection and Planting Trials for Reforestation of Sites Near Mount St. Helens. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 1985; 112p. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, D.G. Film forming antitranspirants: Their effects on root growth capacity, storability, moisture stress avoidance, and field performance of containerized conifer seedlings. For. Chron. 1984, 60, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumroese, R.K.; Page-Dumroese, D.S.; Pinto, J.R. Biochar potential to enhance forest resilience, seedling quality, and nursery efficiency. USDA For. Serv. Tree Plant. Notes 2020, 63, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Slesak, R.A.; Windmuller-Campione, M. Limited effects of biochar application and periodic irrigation on jack pine (Pinus banksiana) seedling growth in northern Minnesota, USA. Can. J. For. Res. 2023, 54, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzokou, P.; Leefers, L.A. Costs and Returns in Michigan Christmas Tree Production, 2006; Bulletin E2999; Michigan State Univeristy Extension: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, J.W.; Kay, M.G.; Weatherhead, E.K. Water regulation, crop production, and agricultural water management—Understanding farmer perspectives on irrigation efficiency. Agric. Water Manag. 2012, 108, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, B.; Linberg, H.; Cregg, B.; Johnson, R. Christmas Tree Species Guide, Michigan State Univeristy Extension. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/christmas_trees/uploads/files/Final%20Christmas%20Tree%20Species%20Guide.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Oregon Department of Agrciulture, Introducing Oregon Christmas Trees. Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/oda/agriculture/Documents/Product%20Sheets/OREGON%20CHRISTMAS%20TREES.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Cregg, B.M.; Schutzki, R. Weed control and organic mulches affect physiology and growth of landscape shrubs. HortScience 2009, 44, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aphalo, P.J.; Ballare, C.L.; Scopel, A.L. Plant-plant signaling, the shade-avoidance response and competition. J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 50, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, K.A. Shade avoidance. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 930–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.; Sellmer, J.C.; Despot, D.A. Assessing Christmas tree planting procedures. Proc. Int. Plant Prop. Soc. 1998, 54, 529–531. [Google Scholar]

- South, D.B.; Starkey, T.E.; Lyons, A. Why healthy pine seedlings die after they leave the nursery. Forests 2023, 14, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R.; Trappe, J.M. Mycorrhiza management in bareroot nurseries. In Forestry Nursery Manual: Production of Bareroot Seedlings; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Renick, B. Truffles in Michigan: Impacts of Herbicides on Their Growth, Effectiveness of in-Field Innoculations, and Discovery of a Local Truffle (Tuber rugosum). Master’s Thesis, Michigsan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 2023; 144p. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J.; Anoruo, A.; Jifon, J.; Simpson, C. Physiological effects of exogenously applied reflectants and anti-transpirants on leaf temperature and fruit sunburn in citrus. Plants 2019, 8, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Landgren, C.; Flecter, R.; Bondi, M.; Withrow-Robinson, B.; Chastagner, G. Christmas Tree Nutrient Management Guide for Western Oregon and Washington; Oregon State University Extension: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2009; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Michigan State University Extension. Nitrogen management in Christmas Trees. 2019. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/nitrogen-management-in-christmas-trees (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Antonangelo, J.A.; Sun, X.; Eufrade-Junior, H.D.J. Biochar impact on soil health and tree-based crops: A review. Biochar 2025, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.C.; Gale, N. Biochar and forest restoration: A review and meta-analysis of tree growth responses. New For. 2015, 46, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarauer, J.L.; Coleman, M.D. Biochar as a growing media component for containerized production of Douglas-fir. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abney, R.; Campbell, H.; Martin, A. Biochar Application—A Practical Guide for Improving and Constructing Soils for Urban Trees; Publication WSFNR-24-31A; University of Georgia Warnell School of Forest Resources: Athens, GA, USA, 2024; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.