Abstract

Olive leaves are a valuable source of natural bioactive compounds, particularly polyphenols and flavonoids, recognized for their potent antioxidant and health-promoting properties. The extraction of these high-value products has gained increasing attention due to their relevance in food sustainability and the circular economy. However, the concentrations and profiles of these compounds vary substantially depending on the olive variety and the extraction method applied. This study evaluated the influence of extraction method and olive variety on the phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of olive leaf extracts from nine cultivars cultivated in Morocco. Two conventional extraction techniques, maceration and Soxhlet extraction, were compared for their efficiency in recovering extraction yield, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and total condensed tannins, along with antioxidant activity measured by DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays. Analyses of variance indicated that varietal differences were the predominant source of variation in phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity, whereas the extraction method mainly influenced yield. Soxhlet extraction enhanced phenolic recovery and antioxidant potential, while maceration favored flavonoid extraction. These findings highlight the potential of olive leaf extracts derived from Manzanilla, Haouzia, Picual, and Moroccan Picholine varieties using Soxhlet as sustainable natural antioxidants for functional, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical uses.

1. Introduction

The rising interest in sustainable resource management has driven researchers and industries to reconsider the potential of agricultural by-products as reservoirs of bioactive compounds. One such underutilized resource is the olive leaf, a by-product of olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivation, which is particularly abundant in Mediterranean regions. Traditionally discarded during pruning and processing, olive leaves are now gaining recognition for their phytochemical richness and promising functional properties [1,2].

Chemically, olive leaves are characterized by a diverse and abundant profile of bioactive compounds, particularly phenolic acids, flavonoids, and condensed tannins, as well as photosynthetic pigments such as chlorophylls and carotenoids [3,4,5]. Due to their strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties, these compounds are considered promising natural alternatives to synthetic additives in the agri-food industry, meeting the increasing consumer demand for clean-label, naturally derived ingredients [4,6,7].

However, the efficiency of recovering these bioactive compounds from olive leaves strongly depends on the extraction method used. Factors such as temperature, solvent polarity, and extraction time can markedly influence both the yield and the biological activity of the resulting extracts [8,9]. Among various extraction parameters, solvent selection remains a decisive factor, as it governs extraction efficiency, selectivity, and environmental compatibility. In line with the principles of green chemistry, ethanol and hydroethanolic mixtures have emerged as preferred solvents for phenolic recovery owing to their low toxicity, renewability, and broad regulatory approval in food cosmetics, and pharmaceutical applications [10,11,12]. Ethanol exhibits an intermediate polarity and strong hydrogen-bonding capacity, enabling the efficient dissolution of a broad spectrum of phenolic molecules, from hydrophilic phenolic acids to moderately lipophilic flavonoids, resulting in a representative extraction of antioxidant constituents [13,14]. Furthermore, its biodegradability, recoverability, and compatibility with sustainable processing strengthen its role as a cornerstone solvent in circular bioeconomy approaches aimed at the valorization of olive by-products [15].

From an operational perspective, solvent selection must be coherently aligned with the extraction methodology employed. Maceration represents a straightforward, low-energy technique that effectively preserves thermolabile compounds by avoiding excessive thermal exposure, whereas Soxhlet extraction offers better solute recovery through continuous solvent percolation under controlled heating, thereby promoting more exhaustive mass transfer. Previous studies have shown that different extraction protocols can significantly influence both the yield and the phytochemical composition of olive leaf extracts, which in turn affects their bioactivity [16,17]. Building on this foundation, recent comparative investigations have further revealed that extraction parameters not only influence the overall yield but also modulate the relative distribution of major phenolic subclasses, particularly oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and luteolin derivatives, resulting in pronounced variations in both antioxidant and antimicrobial activities [18,19].

Intervarietal diversity plays also a decisive role in shaping the biochemical composition and functional potential of olive leaves. Recent comparative studies have consistently reported substantial variety-dependent differences in total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and total condensed tannins (TCT), the major determinants of the antioxidant potential of olive leaf extracts [1,20]. Varieties exhibiting higher concentrations of key phenolic compounds, such as oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, and luteolin derivatives, generally express enhanced radical-scavenging and reducing capacities, while those with comparatively lower phenolic and flavonoid levels display reduced antioxidant performance [21,22,23]. These compositional disparities arise from intrinsic metabolic and genetic specificities and show a strong positive correlation with antioxidant activity assessed by DPPH and ABTS assays [18,24]. Collectively, these findings highlight the critical importance of varietal selection when evaluating the phytochemical and functional potential of olive leaves, as genetic background alone can drive pronounced variability in extract composition and bioactivity, even under standardized extraction conditions.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies conducted in Morocco and neighboring North African countries have investigated the phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of olive leaves under regional pedoclimatic conditions. Olmo-García et al. [25], provided a comprehensive characterization of eleven Moroccan olive cultivars, revealing pronounced varietal differences in oleuropein concentration and other major phenolic compounds. El Adnany et al. [26] and Chaji et al. [27], demonstrated that extraction techniques and pre-treatment parameters markedly influence phenolic recovery and antioxidant activity, whereas Abbas et al. [28], reported significant seasonal and genotypic variability in leaf phytochemical profiles. Similar findings from Tunisia and Algeria further corroborate that both genetic background and environmental factors play a decisive role in shaping the biochemical composition of olive leaves across the Maghreb region [18,29]. Nevertheless, a comprehensive comparative assessment integrating multiple Moroccan cultivars and extraction methodologies remains limited.

The present study addresses this gap by providing a dual assessment of varietal and methodological effects on the phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of nine olive leaf varieties cultivated under Moroccan conditions. To explore their valorization potential, two conventional extraction techniques (cold maceration and Soxhlet extraction) were applied and comparatively evaluated for their efficiency in recovering key phytochemical constituents, including total phenols, flavonoids, and condensed tannins. In the second phase of this study, the antioxidant potential of the obtained extracts was evaluated using two complementary in vitro assays, namely the DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging methods. The distinctive contribution of this work lies in its dual comparative approach, simultaneously examining the effects of intervarietal diversity and extraction methodology on both phytochemical recovery and bioactivity.

This study should also be viewed as a preliminary screening effort aimed at identifying olive leaf varieties with the greatest phytochemical richness and antioxidant potential under Moroccan pedoclimatic conditions. By integrating varietal diversity with two conventional extraction methods, this comprehensive approach not only elucidates the interaction between genetic traits and extraction efficiency but also enhances the scientific understanding of olive biodiversity as a source of natural antioxidants. The resulting dataset provides a valuable foundation for future, more detailed investigations and supports circular economy strategies focused on the conversion of olive leaf biomass into value-added ingredients for functional food and nutraceutical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material Sampling

Olive leaf samples of Olea europaea L. were manually collected from nine varieties cultivated in Morocco, including four Moroccan (Moroccan Picholine, Haouzia, Menara, and Meslala), four Spanish (Arbequina, Arbosana, Manzanilla, and Picual), and one Greek variety (Koroneiki).

Sampling was conducted in Meknes (33°54′14″ N, 5°33′27″ W), located at an altitude of approximately 552 m a.s.l. The region is characterized by a semi-arid Mediterranean climate, with temperatures ranging from 4.5 °C to 36 °C and an average annual rainfall of about 463 mm. Meknes is recognized as one of the principal olive-growing regions of Morocco, known for its long-standing tradition of olive cultivation and favorable pedoclimatic conditions. These characteristics make it an ideal site for assessing varietal and methodological influences on olive leaf phytochemical composition. The collection was performed in mid-October 2021, during the post-harvest period, when secondary metabolite levels are typically stable. Olive leaf samples were randomly harvested from both inner and outer branches of healthy and mature trees to ensure representativeness, with a total of 1.5 kg per variety. For each variety, one composite sample was prepared, and all extractions and analytical measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure precision and reproducibility.

Freshly collected olive leaves were immediately transported to the laboratory and washed under running tap water to remove dust, insects, and other debris. The samples were then air-dried in the shade at ambient room temperature (22–25 °C) with natural ventilation and protected from direct sunlight to minimize degradation of phenolic compounds. Drying continued until a constant weight was achieved, ensuring the removal of residual moisture. Finally, the dried leaves were then finely ground using a mechanical grinder prior to the extraction experiments.

2.2. Extraction Process

Two extraction methods were employed to obtain organic extracts from olive leaves. The first method involved hot extraction using a Soxhlet apparatus, while the second method employed cold maceration.

2.2.1. Soxhlet Extraction

The Soxhlet extraction procedure was carried out following the method of Ben Harb et al. [30], with minor modifications. Concisely, 40 g of dry olive leaves were placed in a cellulose cartridge attached to the Soxhlet apparatus and covered with a condenser. Absolute ethanol (99.9%) was used as the extraction solvent; it was vaporized and then condensed repeatedly while in contact with the plant material. A solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 (w:v) was used to ensure proper solvent diffusion and extraction efficiency. Ethanol was selected for its low toxicity, environmental friendliness, and ease of removal, making it a widely used solvent for extracting bioactive compounds from agri-food waste. The extraction continued until the solvent became clear, which took approximately 5 h under our experimental conditions. The resulting extracts were then evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator (BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, CH-9230 Flawil, n.d., Switzerland) under vacuum at 40–50 °C and subsequently stored at 4 °C until further phytochemical analyses.

2.2.2. Maceration Extraction

The cold maceration procedure was performed following a modified version of the method described by Jiménez et al. [31]. In brief, 30 g of dried olive leaves were first pulverized using a rotary knife homogenizer. The powdered material was then extracted at 25 °C for 24 h using absolute ethanol (99.9%) as the solvent at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 (w:v). The resulting crude extracts were filtered through filter paper, and the solvent was subsequently removed to dryness under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator (BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, CH-9230 Flawil, n.d., Switzerland) at 40–50 °C. The concentrated extracts were stored at 4 °C, alongside the Soxhlet-derived extracts, until further phytochemical analyses.

2.3. Extraction Yield

Following each extraction procedure (maceration and Soxhlet), the extraction yield was calculated as the ratio between the dry mass of the recovered extract obtained after solvent removal to dryness and the initial dry mass of olive leaves. The extraction yield (Y) was expressed in grams of extract per kilogram of dry olive leaf. This calculation was performed in accordance with standard procedures previously reported for olive leaf extraction [1].

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

Total phenolic content (TPC) of the extracts was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method, following the procedure of Singleton et al. [32], with minor modifications. Briefly, 0.5 mL of each extract (1 mg/mL) was placed in a test tube, followed by the addition 2.5 mL of diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (1:10) and 4 mL of sodium carbonate solution (7.5% w/v). The mixture was thoroughly mixed and incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature.

Absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (SPECUVIS1, Wincom Company Ltd., Changsha, China). Previously, a calibration curve was generated using different gallic acid concentrations from 2 to 200 µg/mL, and the results were expressed as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents per milligram of dry weight (µg GAE/mg DW).

2.5. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content

Total flavonoid content (TFC) of each olive leaf extract was determined using the aluminum chloride (AlCl3) colorimetric method, according to Dewanto et al. [33], with slight modifications. Extracts were analyzed at a working concentration of 1 mg/mL, and a quercetin standard curve was prepared using concentrations from 0.5 to 200 µg/mL. In brief, 0.5 mL of each appropriately diluted extracts or quercetin standard solution was mixed with 0.15 mL of 5% (w/v) sodium nitrate (NaNO2) and allowed to stand for 5 min. Subsequently, 0.15 mL of 10% (v/v) aluminum chloride (AlCl3) was added, and the mixture was left to react for 6 min. Finally, 1 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added, and the solution was incubated for 30 min at room temperature.

Absorbance was measured at 510 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (SPECUVIS1, Wincom Company Ltd., Changsha, China), and the results were expressed as micrograms of quercetin equivalents per milligram of dry weight (μg QE/mg DW).

2.6. Determination of Total Condensed Tannins

Total condensed tannin content (TCT) was determined using the vanillin assay in an acidic medium, following the Julkunen-Tiitto method [34]. The extracts were tested at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, and catechin standards ranging from 50 to 600 µg/mL were used to generate the calibration curve. In this procedure, 50 µL of each extract was mixed with 1.5 mL of vanillin/methanol solution (4% w/v) and vortexed thoroughly. Subsequently; 750 µL of concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) was added, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 min.

The absorbance was measured at 500 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (SPECUVIS1, Wincom Company Ltd., Changsha, China). The tannin concentration was calculated from the catechin calibration curve and expressed as microgram of catechin equivalents per milligram of dry weight (µg CE/mg DW).

2.7. Antioxidant Activity Assays

The antioxidant activity of the 54 extracts obtained from the nine olive leaf varieties was evaluated using two complementary in vitro assays: the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging method and ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) or the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) assay. These assays are based on the ability of antioxidants present in the extracts to quench stable free radicals, leading to a measurable decrease in absorbance.

2.7.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

The DPPH free radical scavenging activity was determined following the method of Brand-Williams et al. [35]. A volume of 1.5 mL of each extract (5–100 µg/mL) was mixed with 1.5 mL of 0.2 mM DPPH solution prepared in absolute ethanol. The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark for 30 min at 30 °C, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (SPECUVIS1, Wincom Company Ltd., Changsha, China). Ascorbic acid (5–100 µg/mL) was used as a reference standard.

The percentage of DPPH inhibition was calculated using the following equation:

where A0 is the absorbance of the control and A1 is the absorbance of the sample.

The results were expressed as IC50 values (μg/mL), corresponding to the concentration of extract required to inhibit 50% of DPPH radicals, as determined from the inhibition percentage curve.

2.7.2. ABTS Radical Cation Scavenging Activity

The ABTS+ radical scavenging activity was determined according to the method of Re et al. [36]. This assay measures the ability of antioxidants in the extracts to quench the ABTS+ radical cation, resulting in a decrease in absorbance.

The ABTS+ radical cation was generated by reacting 10 mL of 7 mM ABTS solution with 5 mL of 2.45 mM potassium persulfate (K2S2O8) and allowing the mixture to stand in the dark at room temperature for 12–16 h. The resulting ABTS+ solution was then diluted with ethanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.02 at 734 nm.

For the assay, 3 mL of the prepared ABTS+ solution was mixed with 30 μL of each extract (1 mg/mL), and the reaction mixture was incubated for 1 min in the dark at room temperature. The absorbance was recorded at 734 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (SPECUVIS1, Wincom Company Ltd., Changsha, China).

A calibration curve constructed with Trolox (5–400 µg/mL) was used for quantification, and the results were expressed as micrograms of Trolox equivalents per milligram of dry weight (μg TE/mg DW).

2.8. Statistical Analyses

All determinations were performed in triplicate (three analytical replicates). Prior to statistical analyses, data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance using Levene’s test. Combined analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted using the general linear model (GLM) procedure to assess the main effects of extraction method and olive leaf variety, as well as their interaction. Least significant difference (LSD) tests were applied to compare mean values at a 5% probability level (p < 0.05).

Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA), cluster analysis and correlation matrix computations were performed on the mean values to explore relationships among the measured parameters and to identify grouping patterns among samples. Before performing the PCA, all variables (TPC, TFC, TCT, antioxidant activities, and extraction yield) were standardized to zero mean and unit variance (z-scores) to ensure comparability across different measurement scales. PCA was then carried out on the standardized correlation matrix to elucidate interrelationships among variables. Cluster analysis was subsequently performed using the nearest neighbor linkage method and squared Euclidean distance to confirm sample groupings identified by PCA.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATGRAPHICS Centurion XIX software package version 19.5.01 (Statpoint Technologies, Inc., Warrenton, VA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Combined Analyses of Variance (ANOVA)

Mean squares from the combined ANOVA for the studied parameters—extraction yield (Y), total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), total condensed tannins (TCT), DPPH, and ABTS radical scavenging activities—are presented in Table 1. These analyses revealed that the variety factor was the main source of variation across all phytochemical and antioxidant traits (TPC, TFC, TCT, DPPH, ABTS), highlighting the strong genetic influence on phenolic compound biosynthesis and antioxidant capacity. In contrast, the extraction method exerted the most significant effect (p < 0.001) on extraction yield, while the variety factor explained only a minor fraction of its variability. The interaction between variety and extraction method was also significant for most parameters, suggesting that the extraction efficiency and antioxidant response of each olive variety were strongly dependent on the applied extraction technique.

Table 1.

The mean squares of the combined analyses of variance of olive leaves extracts from nine varieties grown in Morocco obtained using two extraction methods (Maceration and Soxhlet).

3.2. Effects of Variety and Extraction Method on Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity

3.2.1. Phytochemical Composition of Olive Leaf Extracts

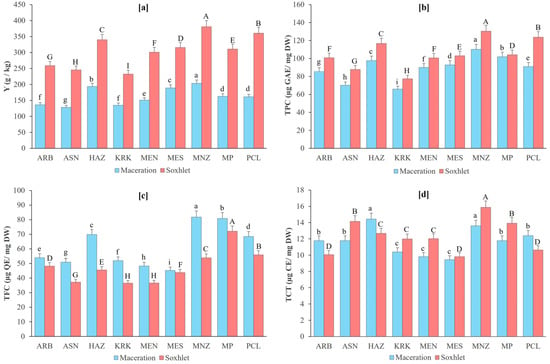

The evaluation of extraction yield (Y), total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and total condensed tannins (TCTs) revealed significant differences among the nine olive varieties and between the two extraction methods (Figure 1). Overall, Soxhlet extraction consistently produced higher values for Y and TPC across all varieties, whereas maceration tended to preserve higher levels of flavonoids.

Figure 1.

Mean comparison for extraction yield (Y) (a), total phenolic content (TPC) (b), total flavonoid content (TFC) (c), and total condensed tannins (TCTs) (d) among olive leaves extracts from nine varieties grown in Morocco obtained using two extraction methods (Maceration and Soxhlet). Y is expressed as g of extract per kilogram of dry olive leaves (g/kg), TPC is expressed as µg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per milligram dry weight (mg DW). TFC is expressed as µg of quercetin equivalent (QE) per milligram dry weight (mg DW). TCT is expressed as µg of catechin equivalent (CE) per milligram dry weight (mg DW). Different letters above the bars (lowercase for maceration and uppercase for Soxhlet) indicate statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 according to LSD test. ARB = Arbequina; ASN = Arbosana; HAZ = Haouzia; KRK = Koroneiki; MEN = Menara; MES = Meslala; MNZ = Manzanilla; MP = Moroccan Picholine; PCL = Picual.

Clear variability in extraction yield was observed among the nine olive varieties (Figure 1a), with Soxhlet consistently outperforming maceration across all varieties. Soxhlet extraction resulted in markedly higher yields, reflecting its superior solvent penetration and continuous heating, which enhance the recovery of extractable solids from olive leaves. The highest yields were obtained for Manzanilla, Picual, and Haouzia, which formed the group of top-performing varieties under both extraction techniques. Intermediate yields were recorded for Moroccan Picholine, Meslalla, and Menara, whereas Arbequina, Arbosana, and Koroneiki showed comparatively lower extraction efficiency. Although the magnitude of improvement varied, the varietal ranking remained generally consistent between methods, indicating inherent differences in the extractable phytochemical load of each variety. These results demonstrate that extraction yield is strongly influenced by both the genetic background of the variety and the extraction method applied, with Soxhlet offering a clear advantage for maximizing recovery.

A similar pattern was observed for total phenolic content (Figure 1b). Soxhlet extraction consistently yielded higher phenolic levels than maceration, confirming the efficiency of continuous hot solvent reflux in enhancing phenolic solubilization. Manzanilla, Haouzia, and Picual formed the group of varieties with the highest TPC values under both extraction methods, indicating their naturally richer phenolic profiles. Intermediate phenolic levels were observed in Moroccan Picholine, Meslalla, and Menara, while Arbequina, Arbosana, and Koroneiki exhibited comparatively lower TPC. Although maceration recovered considerably fewer phenolics across all varieties, the overall varietal ranking remained largely preserved between methods, suggesting that phenolic abundance is mainly genotype-dependent. These results reinforce the strong influence of both variety and extraction technique on phenolic recovery, with Soxhlet providing a substantial advantage for maximizing TPC.

In contrast, total flavonoid content displayed an opposite response to the extraction method (Figure 1c), with maceration unexpectedly yielding higher flavonoid levels than Soxhlet across all varieties. This pattern suggests that flavonoids, particularly heat-sensitive subclasses such as flavones and flavonols, may undergo partial thermal degradation or structural alteration during prolonged heating in Soxhlet extraction. The highest TFC values under both methods were recorded for Manzanilla, Moroccan Picholine, and Haouzia, confirming the strong flavonoid richness of these varieties. Intermediate concentrations were observed in Arbequina, Koroneiki, and Picual, whereas Arbosana, Menara, and Meslalla exhibited comparatively lower levels.

Significant differences in total condensed tannins were observed among the nine olive varieties, whereas extraction method had no meaningful effect. As shown in Figure 1d, Manzanilla consistently exhibited the highest TCT levels under both maceration and Soxhlet extraction, while Meslala and Menara presented the lowest concentrations. Arbosana, Moroccan Picholine, and Picual showed intermediate values, maintaining a similar varietal ranking across methods. For most varieties, TCT values did not differ statistically between maceration and Soxhlet, confirming that tannin recovery was largely independent of extraction conditions. This agrees with the ANOVA results, which indicated no significant method effect on tannin content. These findings suggest that condensed tannins are relatively stable compounds whose extraction is less influenced by heat or solvent cycling compared to other phenolic subclasses. Consequently, their variability across samples is driven primarily by genetic differences rather than by the extraction technique.

3.2.2. Antioxidant Activity of Maceration and Soxhlet Extracts

Antioxidant activity, assessed through both DPPH and ABTS assays, exhibited clear varietal and method-dependent trends (Table 2). Across all olive leaf samples, Soxhlet extracts consistently showed superior radical-scavenging performance, reflected by lower IC50 values in DPPH and higher Trolox-equivalent capacities in ABTS.

Table 2.

The mean values of antioxidant activity measured using the DPPH and ABTS tests for olive leaf extracts from nine varieties grown in Morocco obtained using two extraction methods (Maceration and Soxhlet).

For DPPH, the strongest activity (lowest IC50) was observed in Manzanilla, Haouzia, Picual, and Moroccan Picholine, with Soxhlet IC50 values ranging from 14.06 to 19.49 µg/mL, approaching that of the ascorbic acid reference. In contrast, Arbosana, Koroneiki, and Arbequina exhibited comparatively weaker activity (IC50 > 23 µg/mL), regardless of extraction method. Similar trends were confirmed by the ABTS assay, where Soxhlet extracts of Manzanilla, Picual, Moroccan Picholine, and Haouzia achieved the highest antioxidant capacities (102–122 µg TE/mg DW), substantially exceeding those of varieties such as Arbequina and Koroneiki (<80 µg TE/mg DW). Maceration extracts followed the same varietal ranking but consistently displayed reduced activity, indicating incomplete recovery of highly active phenolic constituents under mild extraction conditions. The agreement between the two assays highlights a method-driven intensification of antioxidant potential under Soxhlet extraction, attributable to enhanced solubilization of phenolics with strong electron- and hydrogen-donating capacities.

3.3. Multivariate Analyses

The correlation matrix among the investigated variables is depicted in Table 3. Overall, significant positive relationships were observed among most of the studied traits, reflecting the interconnected nature of phytochemical composition and antioxidant potential in olive leaf extracts. Total phenolic content (TPC) was strongly correlated with both antioxidant assays (DPPH, r = 0.872 ***; and ABTS, r = 0.810 ***) and moderately with total flavonoid content (r = 0.619 **). Extraction yield was also significantly correlated with TPC (r = 0.599 **) and DPPH (r = 0.496 *), indicating that higher extraction efficiency is generally associated with greater phenolic recovery and antioxidant capacity. In addition, total condensed tannins (TCT) exhibited moderate correlation with both antioxidant assays (DPPH, r = 0.602 **; and ABTS, r = 0.525 *), suggesting their partial contribution to the overall radical scavenging activity. Other correlations were weak or statistically insignificant, indicating limited interdependence among those parameters.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients (n = 18) among the studied traits in olive leaf extracts from nine varieties grown in Morocco obtained using two extraction methods (Maceration and Soxhlet).

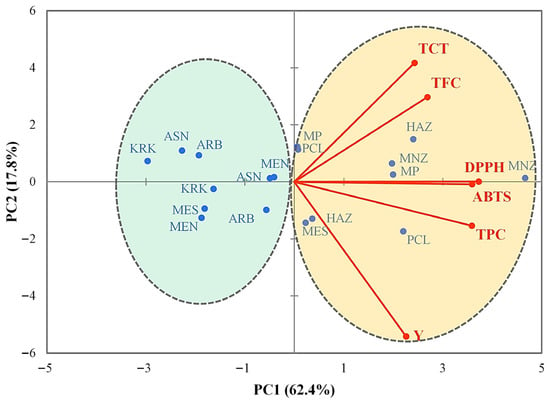

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the correlation matrix based on mean values to establish the combination of each factor (variety and extraction methods) with the studied variables. The obtained results (Figure 2) revealed that 80.2% of the total observed variability was explained by the first two principal components (PC); with PC1 explaining the largest proportion (62.4%) and PC2 contributing to an additional 17.8%. PC1 was strongly associated with extraction yield (Y), total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and antioxidant activities (DPPH, ABTS), all oriented toward the positive direction of this axis. Varieties located on the positive side of PC1 (Manzanilla, Haouzia, Moroccan Picholine, and Picual) were characterized by higher bioactive compound levels and stronger antioxidant potential. In contrast, Arbequina, Arbosana, Koroneiki, and Menara projected on the negative side of PC1, exhibited lower phenolic contents and weaker antioxidant performance. Meslala occupied an intermediate position, reflecting moderate overall phytochemical and antioxidant profile. PC2 was mainly associated with total condensed tannins (TCT), separating varieties with higher tannin accumulation toward the upper region of the plot. Extraction yield contributed negatively along PC2, suggesting that samples richer in tannins tended to exhibit slightly lower extraction efficiency. This spatial distribution along the two axes PC1 and PC2 confirms the existence of distinct varietal groupings driven primarily by genotypic differences in phenolic biosynthesis and extractability.

Figure 2.

PCA projections on axes 1 and 2, accounting for 80.2% of the total variance. Eigenvalues of the correlation matrix are symbolized as vectors representing traits that most influence each axis. The 18 points representing trait means for each olive leaf variety extract are plotted on the plane determined by axes 1 and 2. Y = Extraction yield, TPC = Total phenolic content, TFC = Total flavonoid content, TCT = Total condensed tannins, DPPH = 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, and ABTS = 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid). ARB = Arbequina; ASN = Arbosana; HAZ = Haouzia; KRK = Koroneiki; MEN = Menara; MES = Meslala; MNZ = Manzanilla; MP = Moroccan Picholine; PCL = Picual.

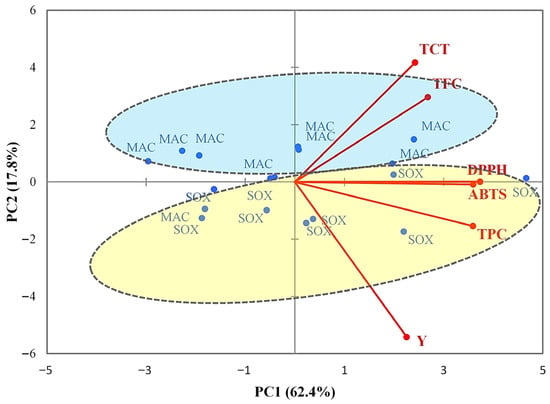

Concerning extraction methods (Figure 3), the samples formed two distinct groups according to the extraction technique. Maceration extracts (MACs), located mainly in the upper part of the plot, were associated with higher levels of total condensed tannins (TCTs) and total flavonoid content (TFC). In contrast, Soxhlet extracts (SOXs) were positioned predominantly in the lower part of the plot and showed stronger associations with total phenolic content (TPC), antioxidant activities (DPPH and ABTS), and extraction yield (Y).

Figure 3.

PCA projections on axes 1 and 2, accounting for 80.2% of the total variance. Eigenvalues of the correlation matrix are symbolized as vectors representing traits that most influence each axis. The 18 points representing trait means for each extraction method are plotted on the plane determined by axes 1 and 2. Y = Extraction yield, TPC = Total phenol content, TFC = Total flavonoid content, TCT = Total condensed tannins, DPPH = 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, and ABTS = 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid). MAC = Maceration; SOX = Soxhlet method.

These findings suggest that maceration favored the extraction of flavonoids, while Soxhlet extraction was more efficient in recovering phenolics and achieving higher yield, resulting in extracts with stronger antioxidant capacities.

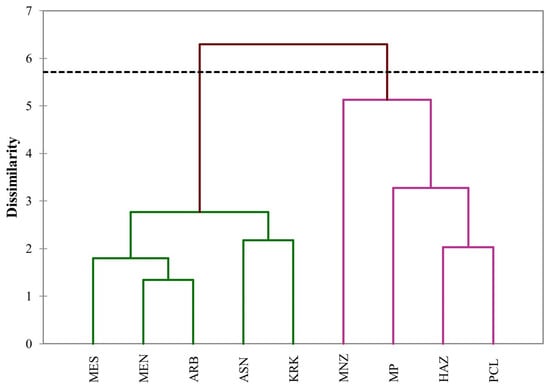

The hierarchical cluster analysis grouped the olive leaf extracts into two well-defined clusters (Figure 4), showing a structure consistent with the PCA outcome. The first cluster, comprising Moroccan Picholine, Haouzia, Picual, and Manzanilla, gathered varieties sharing close compositional profiles, reflecting higher extractive performance and stronger antioxidant activities. The second cluster brought together Menara, Arbequina, Meslala, Arbosana, and Koroneiki, which displayed comparable chemical patterns but overall lower values for most measured traits. This clustering pattern reinforces the multivariate structure observed previously, confirming that varietal proximity is mainly determined by shared phytochemical and functional characteristics (antioxidant potential) rather than extraction conditions alone.

Figure 4.

Hierarchical cluster analysis dendrogram constructed using the nearest neighbor linkage method and squared Euclidean distance for leaf extracts from the nine olive varieties (ARB = Arbequina; ASN = Arbosana; HAZ = Haouzia; KRK = Koroneiki; MEN = Menara; MES = Meslala; MNZ = Manzanilla; MP = Moroccan Picholine; PCL = Picual), based on all measured parameters (total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, total condensed tannins, DPPH, and ABTS).

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Variety and Extraction Method on Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity

The present study evaluated the influence of varietal diversity and extraction method on the phytochemical composition and antioxidant potential of leaf extracts from nine olive varieties cultivated under Moroccan conditions. The analyses of variance revealed that variety was the main factor explaining the variability observed across traits such as total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), DPPH, and ABTS activity. This finding underscores the dominant role of genetic background in determining the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds and, consequently, antioxidant capacity. Similar results were reported by Martínez-Navarro et al. [4], who demonstrated marked inter-cultivar differences in oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol concentrations among Spanish and Greek genotypes, directly influencing their antioxidant potential. Similarly, Šimat et al. [37], documented substantial variation in phenolic profiles among six Mediterranean varieties, highlighting oleuropein, luteolin, and hydroxytyrosol as major discriminant compounds contributing to these differences.

In the present study, distinct varietal patterns were evident, confirming that the intrinsic biochemical potential of each genotype largely determines the phytochemical composition of olive leaves and, consequently, the recovery of bioactive compounds. Manzanilla, Picual, Haouzia, and Moroccan Picholine consistently exhibited the highest levels of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity, regardless of the extraction method employed. These varieties not only displayed superior total phenolic content but also retained substantial amounts of flavonoids and condensed tannins, reflecting a broad spectrum of bioactive metabolites. These findings align with those of Talhaoui et al. [21], who showed that Picual leaves contained one of the highest oleuropein contents, directly correlating with strong radical scavenging activity. Similarly, Mir-Cerdà et al. [23], reported that Picual and Manzanilla leaves, across different growing regions, were particularly rich in hydroxytyrosol and verbascoside, confirming their potential as valuable raw materials for natural antioxidant production. In contrast, cultivars such as Arbequina, Arbosana, and Koroneiki consistently showed lower phenolic levels, highlighting the strong influence of genotype on the distribution and abundance of key phytochemicals, in agreement with Medina et al. [38], who reported comparatively reduced phenolic content in these widely cultivated but metabolically less rich varieties.

Although varietal differences were the predominant source of variation, the extraction method also exerted a notable influence on several parameters. Soxhlet extraction consistently outperformed maceration in terms of extraction yield, total phenolic content, and antioxidant activity. This enhancement is attributed to the combined effects of solvent recirculation and heating, which improve solute diffusion and mass transfer. This observation is consistent with Lama-Muñoz et al. [1], who found that Soxhlet extraction released higher amounts of oleuropein and mannitol from Spanish cultivars owing to continuous solvent reflux. Similarly, Guebebia et al. [39], reported that Soxhlet-derived extracts contained significantly higher concentrations of phenolic acids and flavonoids than those obtained via cold maceration. However, the superiority of Soxhlet was not universal. In the present study, maceration preserved higher levels of flavonoids in certain varieties, suggesting a greater sensitivity of these compounds to heat. This agrees with Martín-García et al. [22], who demonstrated that thermally intensive extraction can degrade heat-labile flavonoids, whereas maceration maintains their structural integrity. Likewise, da Rosa et al. [40], found that microwave- and ultrasonic-assisted methods outperformed Soxhlet for flavonoid preservation, reinforcing that mild extraction conditions are more suitable for recovering temperature-sensitive metabolites.

Interestingly, condensed tannins showed markedly less sensitivity to the extraction method, with comparable TCT values obtained under maceration and Soxhlet for most varieties. This finding aligns with the results reported by Okoduwa et al. [41], who observed relatively stable tannin yields across various extraction protocols in medicinal plants, regardless of solvent polarity or extraction temperature. Similarly, Zhang et al. [42] and Seabra et al. [43], noted that condensed tannin recovery remained largely constant between maceration and Soxhlet extraction, suggesting limited thermal sensitivity compared with other phenolic subclasses. The apparent stability of condensed tannins can be attributed to their high molecular weight and polymeric structure, which confer reduced solubility in most solvents and resistance to degradation during heating [44,45]. This physicochemical resilience explains why tannin concentrations in our study remained statistically unchanged between maceration and Soxhlet extracts, despite the latter’s higher thermal and solvent flux.

Extraction yield also followed a similar trend, with Soxhlet providing higher mass recovery than maceration. This can be attributed to the continuous solvent renewal and elevated temperature that enhance solute diffusion and solvent penetration into plant tissues, thereby improving extraction efficiency. Similar findings were reported by Dobrinčić et al. [46], who demonstrated that Soxhlet extraction yielded higher total solids compared with ultrasound- and maceration-based methods when applied to olive and other plant matrices. However, despite this improved mass recovery, Soxhlet extraction does not necessarily guarantee superior bioactivity, as excessive heating can lead to the degradation of thermolabile constituents such as certain flavonoids or volatile compounds [22,40]. Therefore, while Soxhlet maximizes extraction yield, maceration or assisted mild techniques may offer a better balance between yield and the preservation of antioxidant potency.

The significant interaction between variety and extraction method indicates that extraction efficiency is not uniform but strongly variety dependent. This suggests that the extractability of bioactive compounds is influenced by genotype-specific factors such as leaf microstructure, cell wall composition, and metabolite localization [47,48]. In practical terms, varieties enriched in thermostable phenolic compounds, such as Manzanilla, Picual, and Haouzia, benefited most from Soxhlet extraction, yielding higher total phenolics and enhanced antioxidant activity. In contrast, varieties with a higher content of heat-sensitive flavonoids, such as Manzanilla and Moroccan Picholine, retained more of these compounds under maceration. While maceration preserves these thermolabile metabolites, overall total phenolics and antioxidant activity remain higher under Soxhlet for most varieties. These findings highlight the importance of selecting extraction methods based on the specific phytochemical profile of each variety to optimize recovery of both stable and sensitive bioactive compounds. Such behavior aligns closely with the conclusions of Q. Xiang et al. [49], who demonstrated that optimization parameters such as solvent polarity, temperature, and extraction time, must be adjusted according to varietal characteristics to achieve maximal yield and bioactivity. Therefore, the development of optimized extraction protocols for each olive variety appears essential to enhance compound recovery and ensure optimal preservation of bioactive constituents, rather than relying on a single standardized method.

4.2. Multivariate Analyses

Correlation analyses revealed strong and significant positive associations between total phenolic content and both antioxidant assays, indicating that phenolic compounds are the primary contributors to the antioxidant potential of olive leaf extracts, while flavonoids and condensed tannins also contributed positively, although to a lesser extent. This finding is consistent with Zhang et al. [20], who demonstrated that phenolic concentrations across 32 Chinese olive cultivars accounted for most of the variability in antioxidant activity. Our results are also in line with previous reports highlighting a strong linear relationship between phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity across diverse plant matrices [50,51,52], reinforcing the central role of phenolics as key antioxidant constituents in olive leaves.

PCA clearly differentiated olive leaf extracts according to both varietal and extraction factors. Manzanilla, Haouzia, Picual, and Moroccan Picholine were positioned as high-performing varieties, characterized by higher phenolic content, strong antioxidant activity, and elevated extraction yield. This observation corroborates the results of Ghomari et al. [53], who found Moroccan Picholine extracts to be particularly rich in bioactive phenolics and exhibiting high radical-scavenging efficiency. Conversely, Arbequina, Koroneiki, Arbosana, and Menara grouped together as low-performing varieties, consistent with previous reports highlighting their relatively weak phenolic profiles and limited antioxidant potential [38]. Consistent with these varietal trends, extraction technique separation was also evident. Soxhlet extracts were aligned with superior yield, higher total phenolic content and stronger antioxidant activities, whereas maceration extracts were positioned closer to higher levels of total condensed tannins and flavonoids. These patterns align with the findings of Ağçam and Ozyılmaz [54], who reported that Soxhlet-methanol extracts yielded superior phenolic and antioxidant values, while maceration with aqueous ethanol favored flavonoid recovery. Collectively, these findings reinforce the dual influence of genetic background and extraction strategy on the phytochemical and functional quality of olive leaf extracts.

Cluster analysis based on similarity further confirmed these groupings, reinforcing the PCA-derived structure and supporting the differentiation between high- and low-performing varieties. The resulting clusters provide a practical framework for industrial valorization, enabling the identification of varieties best suited for antioxidant extraction or nutraceutical applications. Similar hierarchical classifications have been reported by López-Salas et al. [55], who proposed clustering as an effective decision-support tool for linking olive varieties with their optimal industrial uses based on compositional and functional traits.

4.3. Industrial and Valorization Implications

Overall, our findings delineate two varietal clusters with distinct industrial valorization of olive leaves within a circular economy framework. The first group of premium varieties composed of Manzanilla, Haouzia, Moroccan Picholine and Picual, displayed superior phenolic content, antioxidant activity, and extraction yield. These characteristics highlight their suitability for high-value applications such as nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetic formulations, where strong antioxidant potential and high extractive efficiency are desired [17,56]. In contrast, the second group of moderate/low-performing varieties of Arbequina, Arbosana, Koroneiki, and Meslala, showed lower overall phytochemical concentrations but still represent valuable raw materials for medium-value sectors, including food preservation, functional additives, and natural cosmetic ingredients. Their exploitation potential can be enhanced through the use of advanced green extraction technologies such as ultrasound-, microwave-, or pulsed-electric-field-assisted extraction, which have been reported to improve polyphenol recovery while maintaining compound stability [55,57]. Overall, these results suggest that the valorization of olive leaves should be guided by cultivar-specific strategies, matching each variety’s biochemical profile with the most appropriate extraction technology and target application. Such an approach enhances both the efficiency and sustainability of olive by-product utilization, consistent with circular bioeconomy principles. Moreover, the demonstrated performance of ethanol-based maceration and Soxhlet extraction highlights their potential for industrial implementation within a green chemistry framework, offering an optimal compromise between extraction yield, compound recovery, and environmental safety. However, these classical techniques remain time- and solvent-intensive. As this study constitutes an initial screening of varietal potential, future research will therefore explore green extraction methods, such as ultrasound- or microwave-assisted extraction, to improve efficiency and support the sustainable, scalable valorization of olive leaf biomass. In addition, forthcoming work will include a detailed phytochemical characterization of the extracts to provide a more comprehensive understanding of their composition and bioactive potential.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that olive leaf bioactivity is primarily governed by varietal identity, while the extraction method and its interaction with genotype modulate the recovery and stability of specific phytochemicals. Phenolic compounds emerged as the key determinants of antioxidant capacity, confirming the strong link between polyphenol richness and functional potential. Multivariate analyses revealed the existence of two distinct varietal groups with contrasting phytochemical and antioxidant profiles, revealing distinct opportunities for targeted valorization. Among them, Manzanilla, Haouzia, Picual, and Moroccan Picholine emerge as promising sources of natural antioxidants for high-value applications. The originality of this work lies in its integrated comparative framework, combining varietal diversity and extraction strategies under Moroccan conditions. These findings advance the concept of eco-extraction and waste valorization by demonstrating that olive leaves, often discarded as by-products of olive milling, represent renewable and high-value reservoirs of bioactive compounds. The use of ethanol, a biodegradable and low-toxicity solvent, aligns with green chemistry principles, minimizing environmental impact. By optimizing extraction parameters and identifying high-performing varieties, this study contributes to reducing biomass waste, improving resource efficiency, and supporting circular bioeconomy models within the olive oil sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.R., R.B. and M.E.Y.; methodology, Y.R. and R.B.; investigation, R.B. and M.E.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.; writing—review and editing, R.B., M.E.Y. and Y.R.; visualization, R.B. and M.E.; supervision, Y.R.; funding acquisition, Y.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by internal funding from Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University (Morocco).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the olive growers of Meknes for their valuable assistance and for generously supplying the olive leaf samples used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| TCT | Total condensed tannins |

| Y | Extraction yield |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| MAC | Maceration method |

| SOX | Soxhlet method |

| ARB | Arbequina |

| ASN | Arbosana |

| HAZ | Haouzia |

| KRK | Koroneiki |

| MEN | Menara |

| MES | Meslala |

| MNZ | Manzanilla |

| MP | Moroccan Picholine |

| PCL | Picual |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Lama-Muñoz, A.; Contreras, M.D.M.; Espínola, F.; Moya, M.; Romero, I.; Castro, E. Content of phenolic compounds and mannitol in olive leaves extracts from six Spanish cultivars: Extraction with the Soxhlet method and pressurized liquids. Food Chem. 2020, 320, 126626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xin, X.; Zhu, S.; Niu, E.; Wu, Q.; Li, T.; Liu, D. Changes in phytochemical profiles and biological activity of olive leaves treated by two drying methods. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 854680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yamani, M.; Sakar, E.H.; Boussakouran, A.; Rharrabti, Y. Leaf water status, physiological behavior and biochemical mechanism involved in young olive plants under water deficit. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 108906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Navarro, M.E.; Kaparakou, E.H.; Kanakis, C.D.; Cebrián-Tarancón, C.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R.; Tarantilis, P.A. Quantitative determination of the main phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and toxicity of aqueous extracts of olive leaves of Greek and Spanish genotypes. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhrech, H.; Aguerd, O.; El Kourchi, C.; Gallo, M.; Naviglio, D.; Chamkhi, I.; Bouyahya, A. Comprehensive review of Olea europaea: A holistic exploration into its botanical marvels, phytochemical riches, therapeutic potentials, and safety profile. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elnahas, R.A.; Elwakil, B.H.; Elshewemi, S.S.; Olama, Z.A. Egyptian Olea europaea leaves bioactive extract: Antibacterial and wound healing activity in normal and diabetic rats. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2021, 11, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, N.M.; Machado, J.; Chéu, M.H.; Lopes, L.; Criado, M.B. Therapeutic potential of olive leaf extracts: A comprehensive review. Appl. Biosci. 2024, 3, 392–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monedero, A.; Santiago, R.; Díaz, I.; Rodríguez, M.; González, E.J.; González-Miquel, M. Efficient recovery of antioxidants from olive leaves through green solvent extraction and enzymatic hydrolysis: Experimental evaluation and COSMO-RS analysis. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 408, 125368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Liang, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Qiu, L.; Zhao, X.; Hu, W. Comparative analysis of extraction technologies for plant extracts and absolutes. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1536590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guex, C.G.; Reginato, F.Z.; Figueredo, K.C.; Da Silva, A.R.H.D.; Pires, F.B.; Jesus, R.D.S.; Lhamas, C.L.; Lopes, G.H.H.; Bauermann, L.D.F. Safety assessment of ethanolic extract of Olea europaea L. leaves after acute and subacute administration to Wistar rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 95, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Nutrizio, M.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. A review of sustainable and intensified techniques for extraction of food and natural products. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 2325–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huamán-Castilla, N.L.; Díaz Huamaní, K.S.; Palomino Villegas, Y.C.; Allcca-Alca, E.E.; León-Calvo, N.C.; Colque Ayma, E.J.; Zirena Vilca, F.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S. Exploring a sustainable process for polyphenol extraction from olive leaves. Foods 2024, 13, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Jayakody, J.; Kim, J.I.; Jeong, J.W.; Choi, K.M.; Kim, T.S.; Seo, C.; Azimi, I.; Hyun, J.; Ryu, B. The Influence of solvent choice on the extraction of bioactive compounds from Asteraceae: A comparative review. Foods 2024, 13, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Liu, L.; Xu, Z.; Kong, Q.; Feng, S.; Chen, T.; Zhou, L.; Yang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Ding, C. Solvent effects on the phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity associated with Camellia polyodonta flower extracts. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 27192–27203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leonardis, A.; Macciola, V.; Iftikhar, A. Present and future perspectives on the use of olive-oil mill wastewater in food applications. In Wastewater from Olive Oil Production; Souabi, S., Anouzla, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Sit, N. Extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials using combination of various novel methods: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debs, E.; Abi-Khattar, A.-M.; Rajha, H.N.; Abdel-Massih, R.M.; Assaf, J.C.; Koubaa, M.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N. Valorization of olive leaves through polyphenol recovery using innovative pretreatments and extraction techniques: An updated review. Separations 2023, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechi, D.; Pérez-Nevado, F.; Montero-Fernández, I.; Baccouri, B.; Abaza, L.; Martín-Vertedor, D. Evaluation of Tunisian olive leaf extracts to reduce the bioavailability of acrylamide in Californian-Style black olives. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıralan, M.; Çengel, H.; Toptancı, İ.; Ramadan, M.F. Effect of olive leaf on physicochemical parameters, antioxidant potential and phenolics of Ayvalik olive oils at two maturity stages. OCL 2024, 31, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, S.; Niu, E.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, D. Comparative evaluation of the phytochemical profiles and antioxidant potentials of olive leaves from 32 cultivars grown in China. Molecules 2022, 27, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talhaoui, N.; Taamalli, A.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Phenolic compounds in olive leaves: Analytical determination, biotic and abiotic influence, and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-García, B.; De Montijo-Prieto, S.; Jiménez-Valera, M.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Ruiz-Bravo, A.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M. Comparative extraction of phenolic compounds from olive leaves using a sonotrode and an ultrasonic bath and the evaluation of both antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; García-García, R.; Granados, M.; Sentellas, S.; Saurina, J. Exploring polyphenol content in olive leaf waste: Effects of geographical, seasonal and varietal differences. Microchem. J. 2025, 215, 114347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghini, F.; Tamasi, G.; Loiselle, S.A.; Baglioni, M.; Ferrari, S.; Bisozzi, F.; Costantini, S.; Tozzi, C.; Riccaboni, A.; Rossi, C. Phenolic profiles in olive leaves from different cultivars in Tuscany and their use as a marker of varietal and geographical origin on a small scale. Molecules 2024, 29, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmo-García, L.; Bajoub, A.; Benlamaalam, S.; Hurtado-Fernández, E.; Bagur-González, M.G.; Chigr, M.; Mbarki, M.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A. Establishing the phenolic composition of Olea europaea L. leaves from cultivars grown in Morocco as a crucial step towards their subsequent exploitation. Molecules 2018, 23, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Adnany, E.M.; Elhadiri, N.; Mourjane, A.; Ouhammou, M.; Hidar, N.; Jaouad, A.; Bitar, K.; Mahrouz, M. Impact and optimization of the conditions of extraction of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of olive leaves (Moroccan picholine) using response surface methodology. Separations 2023, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaji, S.; Zenasni, W.; Ouaabou, R.; Ajal, E.A.; Lahlali, R.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Hanine, H.; Černe, M.; Pasković, I.; Merah, O.; et al. Nutrient and bioactive fraction content of Olea europaea L. leaves: Assessing the impact of drying methods in a comprehensive study of prominent cultivars in Morocco. Plants 2024, 13, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.; Idrissi, I.J.; Rouas, S.; Dehhaoui, M.; El Kamli, T.; Mokrini, F.; Bouchtaoui, E.M.; Ouazzani, N. Unveiling the seasonal and varietal effects on phenolic compounds of Moroccan olive leaves for effective valorization. Biomass 2025, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelouf, I.; Jabri Karoui, I.; Lakoud, A.; Hammami, M.; Abderrabba, M. Comparative chemical composition and antioxidant activity of olive leaves Olea europaea L. of Tunisian and Algerian varieties. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Harb, M.; Abubshait, S.; Etteyeb, N.; Kamoun, M.; Dhouib, A. Olive leaf extract as a green corrosion inhibitor of reinforced concrete contaminated with seawater. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 4846–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P.; Masson, L.; Barriga, A.; Chávez, J.; Robert, P. Oxidative stability of oils containing olive leaf extracts obtained by pressure, supercritical and solvent-extraction. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanto, V.; Wu, X.; Adom, K.K.; Liu, R.H. Thermal processing enhances the nutritional value of tomatoes by increasing total antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Phenolic constituents in the leaves of northern willows: Methods for the analysis of certain phenolics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1985, 33, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimat, V.; Skroza, D.; Tabanelli, G.; Čagalj, M.; Pasini, F.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Sterniša, M.; Smole Možina, S.; Ozogul, Y.; et al. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of hydroethanolic leaf extracts from six Mediterranean olive cultivars. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, E.; Romero, C.; García, P.; Brenes, M. Characterization of bioactive compounds in commercial olive leaf extracts, and olive leaves and their infusions. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4716–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guebebia, S.; Othman, K.B.; Yahia, Y.; Romdhane, M.; Elfalleh, W.; Hannachi, H. Effect of genotype and extraction method on polyphenols content, phenolic acids, and flavonoids of olive leaves (Olea europaea L. subsp. europaea). Int. J. Plant Based Pharm. 2021, 2, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa, G.S.; Vanga, S.K.; Gariepy, Y.; Raghavan, V. Comparison of microwave, ultrasonic and conventional techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from olive leaves (Olea europaea L.). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 58, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoduwa, S.I.R.; Umar, I.A.; James, D.B.; Inuwa, H.M.; Habila, J.D. Evaluation of extraction protocols for anti-diabetic phytochemical substances from medicinal plants. World J. Diabetes 2016, 7, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.W.; Lin, L.G.; Ye, W.C. Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: A comprehensive review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, I.J.; Chim, R.B.; Salgueiro, P.; Braga, M.E.; De Sousa, H.C. Influence of solvent additives on the aqueous extraction of tannins from pine bark: Potential extracts for leather tanning. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cork, S.J.; Krockenberger, A.K. Methods and pitfalls of extracting condensed tannins and other phenolics from plants: Insights from investigations on Eucalyptus leaves. J. Chem. Ecol. 1991, 17, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzella, L.; Napolitano, A. Condensed tannins, a viable solution to meet the need for sustainable and effective multifunctionality in food packaging: Structure, sources, and properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrinčić, A.; Repajić, M.; Garofulić, I.E.; Tuđen, L.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Levaj, B. Comparison of different extraction methods for the recovery of olive leaves polyphenols. Processes 2020, 8, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; Bascón-Villegas, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, F.; Fernández-Prior, Á.; Rosal, A.; Carrasco, E. Valorisation of Olea europaea L. olive leaves through the evaluation of their extracts: Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Foods 2021, 10, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.L.C.C.; Mazzinghy, A.C.D.C.; Correia, V.T.D.V.; Nunes, B.V.; Ribeiro, L.V.; Silva, V.D.M.; Weichert, R.F.; De Paula, A.C.C.F.F.; De Sousa, I.M.N.; Ferreira, R.M.D.S.B.; et al. An integrative approach to the flavonoid profile in some plants’ parts of the Annona Genus. Plants 2022, 11, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Wang, J.; Tao, K.; Huang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, J.; Tan, H.; Chang, H. Optimization of phenolic-enriched extracts from olive leaves via ball milling-assisted extraction using response surface methodology. Molecules 2024, 29, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, M.; Chamkha, M.; Sayadi, S. Comparative study on phenolic content and antioxidant activity during maturation of the olive cultivar Chemlali from Tunisia. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5476–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello-Andrade, J.M.; Fasolo, D. Polyphenol antioxidants from natural sources and contribution to health promotion. In Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease; Watson, R.R., Preedy, V.R., Zibadi, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbash, E.M.; Abdel-Shakour, Z.T.; El-Ahmady, S.H.; Wink, M.; Ayoub, I.M. Comparative metabolic profiling of olive leaf extracts from twelve different cultivars collected in both fruiting and flowering seasons. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghomari, O.; Sounni, F.; Massaoudi, Y.; Ghanam, J.; Drissi Kaitouni, L.B.; Merzouki, M.; Benlemlih, M. Phenolic profile (HPLC-UV) of olive leaves according to extraction procedure and assessment of antibacterial activity. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 23, e00347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağçam, S.; Ozyilmaz, G. Investigation of antioxidant properties of olive leave extracts from Hatay by different extraction methods. Eurasian J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2022, 5, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Salas, L.; Expósito-Almellón, X.; Valencia-Isaza, A.; Fernández-Arteaga, A.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Lozano-Sánchez, J. Eco-friendly extraction of olive leaf phenolics and terpenes: A comparative performance analysis against conventional methods. Foods 2025, 14, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sordini, B.; Urbani, S.; Esposto, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Daidone, L.; Veneziani, G.; Servili, M.; Taticchi, A. Evaluation of the effect of an olive phenolic extract on the secondary shelf life of a fresh pesto. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvano, C.D.; Tamborrino, A. Valorization of olive by-products: Innovative strategies for their production, treatment and characterization. Foods 2022, 11, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).