Abstract

To investigate the impact mechanism of different fertilization modes on the rhizosphere soil microecology of Camellia sinensis (C. sinensis), this study adopted 100% chemical fertilizer (HCF), 100% organic fertilizer (HOF), 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer (HTC), 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer (HHOC), and 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer (HTO) applied to C. sinensis. In May 2025, samples were collected for measurement and analysis. The results showed that the combination of organic–inorganic fertilizers (especially HTO) significantly increased the content of available nutrients in the soil while maintaining a high pH value, organic matter, and total nutrient content. Microbial community analysis showed that the key microbial groups sensitive to different fertilization responses were Thauera, Zoogloea, and Ceratobasidium. Functional prediction revealed that HCF significantly enriched nitrogen respiration and plant pathogenicity functions, while HOF treatment resulted in a decreased relative abundance of sequences related to pathogenesis. The results of structural equation modeling and path intensity analysis indicated that there was a significant synergistic effect among key microbial communities, which strongly drove their functional expression. The enhancement of these functions resulted in a decrease in soil pH, total soil nutrient content, and available nutrient content. The combination of organic and inorganic fertilizers could optimize the microbial community structure, balance its functional expression, and alleviate the effects caused by single fertilization. This study preliminarily explored the effects of different fertilization modes on the rhizosphere soil microbial community and nutrient transformation of C. sinensis, providing a reference for the subsequent application of organic–inorganic fertilizers in C. sinensis planting.

1. Introduction

Camellia sinensis (C. sinensis), as a major economic crop in China, exhibits physiological activities closely linked to soil fertility levels and microbial community dynamics [1]. Fertilization is a core component of C. sinensis plantation ecosystem management, directly regulating soil microenvironment stability, nutrient transformation efficiency, and plant nutrient uptake capacity [2,3]. While long-term single application of chemical fertilizers may temporarily boost yields, it triggers cascading effects, including accelerated soil acidification, diminished microbial diversity, and reduced ecosystem service functions [4]. Against the backdrop of agricultural ecological transformation, organic fertilizer substitution for chemical fertilizers has garnered widespread attention for its advantages in improving soil aggregate structure, activating microbial metabolic functions, and sustaining C. sinensis plantation productivity [5,6]. However, the effects of the combination of organic and chemical fertilizers on the microbial diversity and functions of C. sinensis rhizosphere soil are not yet clear. Therefore, deciphering the regulatory response of rhizosphere soil microorganisms under different fertilization patterns holds significant implications for refining C. sinensis plantation nutrient management strategies, ensuring healthy growth, and achieving high-quality, high-yield production.

Soil microorganisms serve as the core driving force behind nutrient biogeochemical cycles, with their community structure and functional characteristics directly determining soil fertility and plant nutrition levels [7,8]. Existing research indicates that long-term excessive application of chemical fertilizers significantly disrupts nitrogen cycling equilibrium in C. sinensis plantation soils [9]. This not only intensifies the nitrification pathway mediated by ammonium-oxidizing bacteria but also enhances denitrifying microbial activity, promoting nitrogen loss in forms such as N2O, thus exacerbating the greenhouse effect and nitrogen loss [10]. Li et al. [11] found that long-term application of chemical fertilizers reduces soil microbial diversity, enhances the expression of soil microbial denitrification genes, and accelerates nitrogen loss. Ying et al. [12] also found that long-term application of chemical fertilizers to rice can reduce the abundance of soil microbial nitrogen-related functional genes, thereby affecting rice nitrogen absorption. In contrast, organic fertilizer application optimizes soil conditions by increasing organic matter content, promoting beneficial microbial colonization and functional expression, thereby improving the rhizosphere microenvironment [13,14]. However, the slow release rate of nutrients from organic fertilizers is not conducive to the rapid acquisition of nutrients by C. sinensis [15]. Against this backdrop, the combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers has emerged as a research hotspot in C. sinensis plantation fertilization strategies due to its ability to coordinate nutrient supply intensity and microbial activity [16,17].

Extensive research has confirmed that fertilization practices are key drivers shaping the diversity and compositional patterns of bacterial and fungal communities in C. sinensis plantation soils [18,19]. Specifically, long-term single application of chemical fertilizers often leads to a decline in bacterial community diversity, whereas supplemental organic fertilizer application enhances microbial community structural stability and functional complexity [20]. More importantly, fertilization management directly regulates the efficiency of biogeochemical cycles of elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in soil by influencing the abundance and distribution of key functional groups like nitrogen-fixing bacteria and phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria [9]. However, the synergistic regulation of the C. sinensis rhizosphere microbial community and its interaction mechanism with C. sinensis by organic–inorganic application is still unclear, and the relationship between key microbial groups and their functions and soil nutrients is still unclear. Therefore, exploring the effects of fertilization patterns on the structure, function, and key groups of rhizosphere microbial communities in C. sinensis is crucial for revealing the microbial mechanisms underlying soil nutrient transformation.

Assuming that compared to single fertilization, the combination of organic–inorganic fertilizers can enhance microbial diversity, stabilize their functions, and synergistically improve the nutrient conversion efficiency of C. sinensis rhizosphere soil. Accordingly, this study employed C. sinensis as an experimental model and conducted field trials with five distinct fertilization patterns to investigate the effects of fertilization on nutrient transformation in the rhizosphere soil of C. sinensis. First, high-throughput sequencing technology was used to sequence the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and fungal ITS region in the C. sinensis rhizosphere soil. This approach aimed to elucidate the impact of fertilization patterns on microbial community structure and identify characteristic microbial groups that respond significantly to fertilization treatments. Functional prediction analysis was further conducted to decipher the potential ecological functions carried by these characteristic microorganisms. Finally, by integrating microbial data with physicochemical indicators of C. sinensis rhizosphere soil, a network linking microorganisms, functions, and soil nutrient transformation was constructed. This approach aims to model putative pathways through which fertilization patterns may influence nutrient transformation in C. sinensis rhizosphere soil by altering the rhizosphere microenvironment—particularly microbial community structure and function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

This study selected a C. sinensis plantation in Xibian Village, Xingcun Town, Wuyishan City, Nanping City, Fujian Province, China (27°39′43.37″ N, 117°53′33.57″ E) as the experimental site. The tea cultivar tested was Huangjingui (Camellia sinensis cv. Huangjingui), and it was 11 years old before the experiment. Chemical fertilizers (N:P2O5:K2O = 1:1:1) were used for fertilization in the C. sinensis plantation. The experimental area featured acidic red soil with a pH value of 4.05. Key physicochemical properties were as follows: total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and total potassium contents were 1.16 g/kg, 0.14 g/kg, and 4.32 g/kg, respectively; available nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium contents were 22.38 mg/kg, 34.16 mg/kg, and 11.65 mg/kg, respectively; and organic matter content was 9.17 g/kg. To investigate the effects of different fertilization patterns on the rhizosphere soil microbiome of C. sinensis, five fertilization treatments were randomly set up in the same C. sinensis plantation area (flat C. sinensis plantation) (Figure 1), i.e., 100% chemical fertilizer (HCF), 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer (HTC), 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer (HHOC), 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer (HTO), and 100% organic fertilizer (HOF). Each treatment was replicated three times, with each replicate covering an area of 100 m2. The chemical fertilizer used was the “Stanley” compound fertilizer (N:P2O5:K2O = 1:1:1) and was purchased from Stanley Agricultural Group Co., Ltd. (Linyi, China), with a recommended application dosage of 0.07 kg/m2. The organic fertilizer was purchased from Zhongnong Lvkang (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), and was a plant humus organic fertilizer, featuring a nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium ratio of 3.5:3:3 and an organic matter content of 45%, a C:N ratio of 8:1, with a recommended application dosage of 0.30 kg/m2. Fertilization treatments commenced in October 2024 using the trench burial method. Specific procedures were as follows: trenches (20 cm in width and 25 cm in depth) were excavated 30 cm from the main stem of each C. sinensis. Fertilizer for each treatment was uniformly applied in a single application into the trenches, followed by backfilling with soil. By May 2025, rhizosphere soil samples were collected from C. sinensis for physicochemical property analysis and high-throughput sequencing of bacteria and fungi. Rhizosphere soil sampling employed a five-point method. Five C. sinensis were randomly selected, the top 25 cm of soil was removed to expose roots, and soil adhering to root surfaces was collected. Samples were thoroughly mixed to form one biological replicate, with three independent replicates collected per fertilization treatment.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of different fertilization treatments.

2.2. Determination of Basic Physical and Chemical Properties of Soil

Soil samples collected from the rhizosphere of C. sinensis were used to determine basic physicochemical parameters, with three independent replicates per sample. The analysis primarily followed the method described by Wang et al. [21]. Briefly, soil pH was measured using the potentiometric method with a water-to-soil ratio of 2.5:1. Organic matter content was determined via high-temperature oxidation with potassium dichromate and concentrated sulfuric acid, followed by titration with ferrous sulfate. Total nitrogen was determined via high-temperature digestion with concentrated sulfuric acid followed by Kjeldahl titration. Total phosphorus and total potassium were determined by NaOH fusion, followed by molybdenum-antimony anti-colorimetry and flame photometry, respectively. Available nitrogen was extracted with NaOH and titrated with hydrochloric acid. Available phosphorus was extracted with NaHCO3 and determined by the molybdenum-antimony anti-colorimetric method. Available potassium was extracted with ammonium acetate and determined by flame photometry.

2.3. Microbial High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis

Total DNA from C. sinensis rhizosphere soil microorganisms was extracted using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA), with DNA purity and concentration assessed via Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Amplification of the V3–V4 region of the bacterial 16S rDNA was performed using universal primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Fungal ITS rDNA amplification employed primers ITS1 (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS2 (5′-TGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′). An 8 bp barcode sequence was added to the 5′ end of all primers to enable multiplex sample identification. PCR reactions were performed on an ABI 9700 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Both bacterial and fungal amplification reactions consisted of a 25 μL reaction volume containing 30 ng DNA template, 1 μL each of forward and reverse primers (5 μM), 3 μL BSA (2 ng/μL), 12.5 μL 2× Taq Plus Master Mix, and ddH2O to a final volume. The bacterial PCR program was as follows: 95 °C pre-denaturation for 5 min; 28 cycles of 95 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 50 s, 72 °C for 45 s; followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The fungal program was as follows: 94 °C pre-denaturation for 30 s; followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 5 s, 55 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Each sample had 3 independent replicates. Amplified products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and then sequenced libraries were constructed using the NEB Next Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Libraries were submitted to Beijing Allwegene Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for paired-end sequencing (PE250/PE300) on Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq 2000/Novaseq 6000 platforms (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). A total of 60 fastq files were obtained, and the Miseq raw reads were deposited in the China National Center for Bioinformation Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA031329, accessed on 16 October 2025). Bioinformatics analysis on the data obtained from sequencing was performed, as detailed in Supplementary Material Table S1. Functional analysis of bacterial and fungal communities was performed using FAPROTAX and FUNGuild tools, respectively, based on the obtained sequencing data.

2.4. Data Statistical Analysis

All measurement data and raw microbial sequencing data in this study were initially organized using Excel 2021. Subsequently, statistical analysis and visualization were performed in the RStudio (v4.4.2) platform using corresponding R packages [22]. ANOVA was used to test the significance of intergroup differences, and Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used for pairwise comparisons. All p-values were corrected for false discovery rate (FDR) using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Specific R packages included ggVennDiagram 1.5.4 (Venn diagrams), vegan 2.7.1 and ggplot2 3.5.2 (alpha diversity and PCoA analysis), Hmisc 5.2.3, and minpack.lm 1.2.4 (neutral community model), ComplexHeatmap 2.18.0 (trend heatmaps), microeco 1.15.0 (LEfSe analysis), ropls 1.38.0 (OPLS-DA modeling), plspm 0.5.1 (PLS-SEM path analysis), ggraph 2.2.1 (correlation networks), clusterProfiler 4.14.6 (functional enrichment), and vegan 2.7.1 (RDA ordination plots).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Physicochemical Indicators in the Rhizosphere Soil of C. sinensis

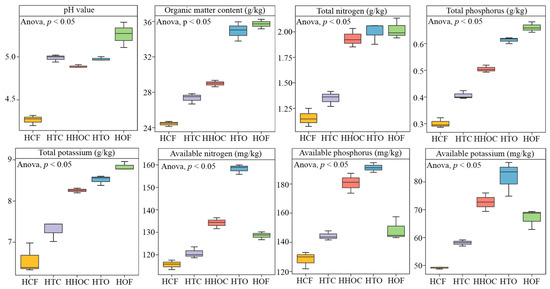

This study measured the physicochemical parameters of C. sinensis rhizosphere soil under different fertilization treatments. Results indicate (Figure 2) that significant differences exist among treatments in pH value, organic matter content, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and total potassium. Their respective ranges were 4.27–5.26, 24.45–35.72 g/kg, 1.16–2.02 g/kg, 0.30–0.66 g/kg, and 6.25–8.84 g/kg, respectively. Overall, these parameters followed the trend: HOF > HTO > HHOC > HTC > HCF (p < 0.05). Additionally, different fertilization treatments significantly influenced the available nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content in the C. sinensis rhizosphere soil. Their ranges were 115.62–158.24 mg/kg, 128.29–194.20 mg/kg, and 49.14–81.82 mg/kg, respectively, with the order of content being HTO > HHOC > HOF > HTC > HCF (p < 0.05). These results indicate that the combined application of organic and chemical fertilizers, with an increased organic fertilizer ratio, enhanced soil pH, organic matter, and total nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content in the rhizosphere soil of C. sinensis. Among all treatments, the 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment (HTO) demonstrated the most effective improvement in soil nutrient availability, indicating this application ratio holds the greatest potential for enhancing nutrient availability in tea rhizosphere soil.

Figure 2.

The effect of the combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers on the physicochemical properties of tea rhizosphere soil. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively.

3.2. Effects of Organic Fertilizer Application on the Structure and Diversity of Microbial Communities in the Rhizosphere Soil of C. sinensis

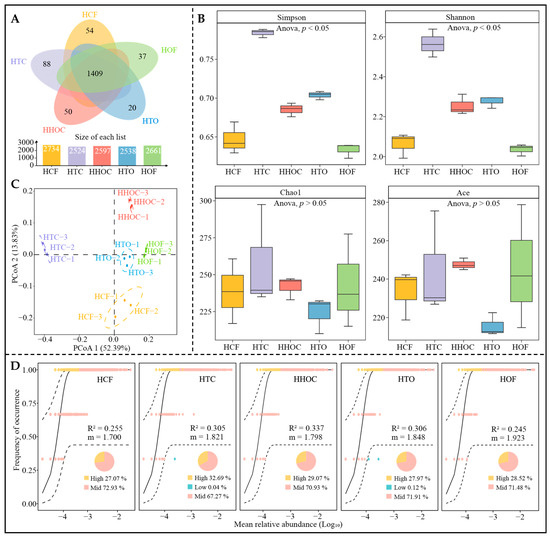

Fertilization is a core agronomic practice for ensuring the healthy growth and quality development of C. sinensis [23]. Simultaneously, fertilization alters the rhizosphere microenvironment of C. sinensis, driving the restructuring of soil microbial communities, diversity, and ecological functions [24]. Accordingly, this study employed high-throughput sequencing technology to systematically analyze the effects of different fertilization treatments on the microbial community structure of C. sinensis rhizosphere soil. Bacterial sequencing results revealed (Figure 3A) that 3581 bacterial OTUs were identified in the C. sinensis rhizosphere soil, with 1409 OTUs (39.35%) shared across all treatments. This indicates that fertilization treatments play a significant role in shaping bacterial community composition. The α-diversity analysis showed (Figure 3B) significant differences in Simpson and Shannon indices among soil bacteria under different fertilization treatments. Notably, the diversity indices of organic-chemical fertilizer combinations (HTC, HHOC, and HTO) were significantly higher than those of single organic fertilizer (HOF) or chemical fertilizer (HCF) treatments, suggesting that balanced nutrient supply might better maintain soil bacterial community diversity [25]. However, the Chao1 and Ace indices, reflecting species richness, showed no significant differences among treatments, suggesting that fertilization primarily affects community evenness rather than total species abundance. The PCoA analysis results from β-diversity analysis (Figure 3C) revealed distinct separation of samples from different fertilization treatments in the ordination space, indicating that fertilization differences are a key factor driving microbial community structural differentiation [9]. Further analysis using a neutral community model (Figure 3D) revealed higher R2 values for treatments combining organic and chemical fertilizers (HTC, HHOC, and HTO), indicating a greater proportion of stochastic processes in community assembly and relatively lower community stability under these treatments [26]. Conversely, the single application of organic fertilizer (HOF) had the highest migration rate (m value), suggesting this treatment is more conducive to bacterial migration and colonization. In contrast, the single application of chemical fertilizer (HCF) had the lowest m value, indicating it might suppress bacterial dispersal capacity. Thus, the rational combination of organic and chemical fertilizers not only enhances soil bacterial diversity but also strengthens bacterial migration and aggregation capabilities.

Figure 3.

Effects of combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers on bacterial community diversity in tea rhizosphere soil. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively. (A) Venn diagram analysis of bacterial communities. (B) α-diversity analysis. (C) PCoA analysis of β-diversity; (D) Neutral community model analysis.

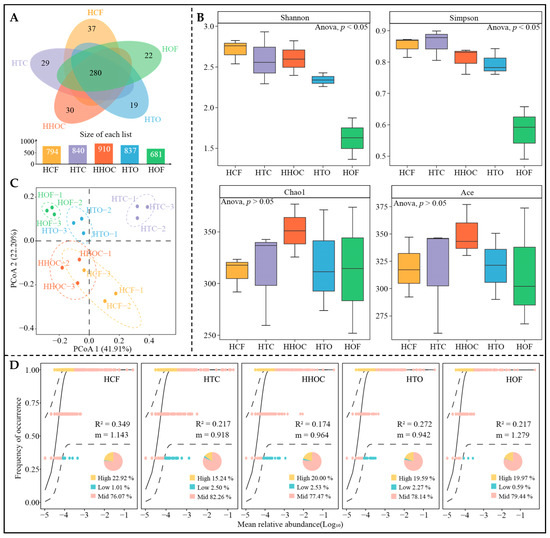

Additionally, this study further analyzed fungal communities. Sequencing results indicate (Figure 4A) that a total of 1340 fungal OTUs were identified across all treatments, with 280 shared OTUs (accounting for 20.90%). This indicates that fertilization treatments exert a greater influence on fungal community composition. Analysis of α-diversity (Figure 4B) revealed that Simpson and Shannon indices for soil fungi decreased with increasing organic fertilizer application dosage, while Chao1 and Ace indices showed no significant changes. PCoA analysis of β-diversity revealed (Figure 4C) that samples from different fertilization treatments were largely segregated in the ordination space. This finding indicates that fertilization differences drive differentiation in soil fungal community structure. Increased organic fertilizer application reduced fungal community evenness but had a minor effect on total species richness. Analysis of neutral community models revealed (Figure 4D) that HCF exhibited the highest R2 value, indicating that random processes dominated its community construction and resulted in lower community stability. Meanwhile, HOF demonstrated the largest m value, suggesting this treatment is more conducive to fungal migration and colonization. This result exhibited distinct differences from the response patterns of bacterial communities, indicating that fungi and bacteria employ markedly different ecological strategies and community construction mechanisms when responding to various fertilization treatments.

Figure 4.

Effects of combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers on fungal community diversity in tea rhizosphere soil. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively. (A) Venn diagram analysis of fungal communities. (B) α-diversity analysis. (C) PCoA analysis of β-diversity. (D) Neutral community model analysis.

3.3. Screening Key Microorganisms Responsible for Significant Changes in C. sinensis Rhizosphere Soil Under Different Fertilization Treatments

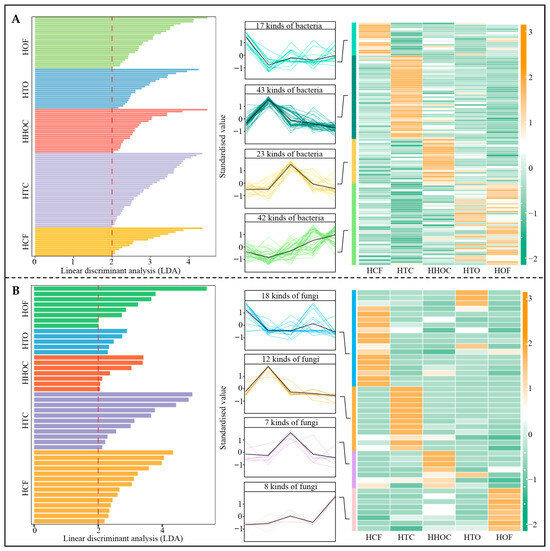

Based on the above analysis, this study further screened key microorganisms exhibiting significant changes in the C. sinensis rhizosphere soil following different fertilization treatments. First, the 3581 bacterial OTUs obtained were annotated, identifying a total of 445 bacterial genera. LEfSe analysis (Figure 5A) was performed with the screening criteria set at LDA > 2 and p < 0.05, which identified 125 bacterial genera with significant differences in abundance. Among these, 17 genera exhibited abundance patterns of HCF > HOF > HHOC > HTO > HTC, 43 genera showed HTC > HHOC > HCF > HTO > HOF, 23 genera showed HHOC > HTO > HOF > HCF > HTC, and 42 genera exhibited HOF > HTO > HHOC > HCF > HTC. Additionally, 1340 fungal OTUs were annotated to 319 fungal genera. LEfSe analysis (Figure 5B) revealed 45 fungal genera with significant differences in abundance using LDA > 2 and p < 0.05 as screening criteria. Among these, 18 genera showed abundance patterns of HCF > HTO > HTC > HHOC > HOF, 12 genera exhibited HTC > HCF > HHOC > HTO > HOF, 7 genera followed HHOC > HTO > HCF > HTC > HOF, and 8 genera showed HOF > HHOC > HTO > HTC > HCF. These results demonstrate that different fertilization treatments significantly alter the microbial community structure and abundance in the C. sinensis rhizosphere soil, indicating that fertilization measures exert a significant effect on soil microbial composition, with marked differences being observed among treatments.

Figure 5.

Screening and trend analysis of differential microorganisms in tea rhizosphere soil under the combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively. (A) LEfSe screening of differential bacteria and their quantitative changes in the rhizosphere soil of C. sinensis after the combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers. (B) LEfSe screening of differential fungi and their quantitative changes in tea rhizosphere soil after combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers.

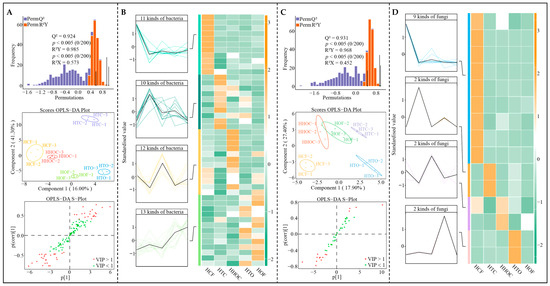

Further OPLS-DA models were constructed for different fertilization treatments using microorganisms exhibiting significant differences to screen for key differential microorganisms. The results of constructing OPLS-DA models for bacterial communities showing significant changes in C. sinensis rhizosphere soil under different fertilization treatments (Figure 6A) indicate that the model effectively distinguished between treatments, with both the goodness-of-fit (R2Y) and predictive capability (Q2) being at significant levels (p < 0.005). Key bacterial genera were selected based on a variable importance in projection (VIP) value > 1 and a significance level of p < 0.05. A total of 46 key bacterial genera were identified. Analysis of abundance trends (Figure 6B) revealed the following patterns: the abundance for 11 genera followed the pattern of HCF > HOF > HHOC > HTO > HTC; the abundance for 10 genera presented the pattern of HTC > HTO > HHOC > HCF > HOF; the abundance for 12 genera presented the pattern of HHOC > HCF > HOF > HTO > HTC; and the abundance for 13 genera exhibited the pattern of HOF > HTO > HTC > HHOC > HCF. Moreover, the OPLS-DA model for fungal communities that were significantly altered in C. sinensis rhizosphere soil under different fertilization treatments also effectively distinguished between treatments, with R2Y and Q2 reaching significant levels (p < 0.005). Fifteen key fungal genera were identified to distinguish fertilization treatments (Figure 6C). Analysis of abundance trends (Figure 6D) revealed that for 9 fungal genera, abundance followed HCF > HHOC > HTO > HOF > HTC; for 2 genera, HTC > HTO > HHOC > HCF > HOF; for 2 genera, HHOC > HCF > HOF > HTO > HTC; and for 2 genera, HTO > HTC > HCF > HHOC > HOF. These findings demonstrate that different fertilization treatments significantly alter the microbial community structure and abundance of rhizosphere soil in C. sinensis. Notably, the composition changes in key microbial groups identified through multivariate modeling might further influence the functional characteristics of the rhizosphere microbial ecosystem.

Figure 6.

Screening of key differential microorganisms in tea rhizosphere soil and analysis of their quantitative changes under the combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively. (A) Constructing OPLS-DA models of different fertilization treatments using differential bacteria to screen for key bacteria. (B) Trend changes in the number of key bacteria. (C) Constructing OPLS-DA models of different fertilization treatments using differential fungi to screen for key fungi. (D) Trend changes in the number of key fungi.

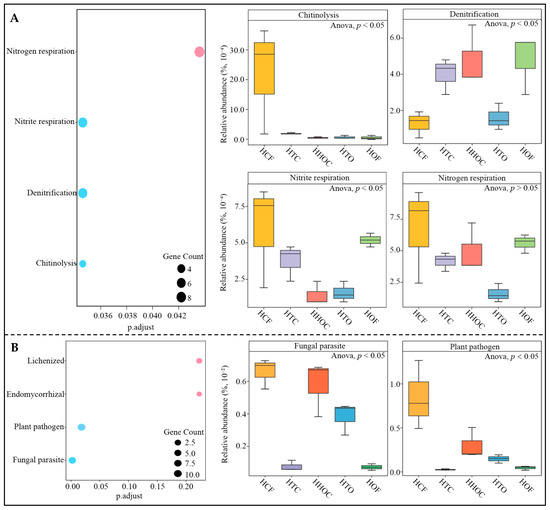

3.4. Prediction of Key Microbial Functions and Analysis of Major Contributing Microorganisms Under Different Fertilization Treatments

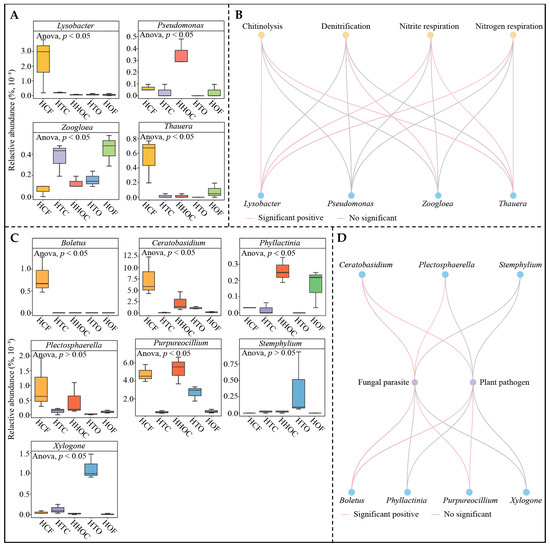

Based on the above analysis, this study predicted key microbial functions to investigate the effects of different fertilization treatments on key microbial functions in the rhizosphere soil of C. sinensis. The functional prediction results for key bacteria (Figure 7A) indicate significant enrichment in four functions. Among these, chitinolysis, nitrite respiration, and nitrogen respiration functions were highest under the HCF treatment, while denitrification was highest under the HOF treatment, and the four functions showed intermediate levels under the organic fertilizer and chemical fertilizer co-application treatments (HTC, HHOC, and HTO). The HCF treatment likely stimulates the metabolic activity of nitrogen-transforming microorganisms by providing high concentrations of inorganic nitrogen sources [27]. In contrast, the abundant organic matter in the HOF treatment may have provided denitrifying microorganisms with a more suitable anaerobic environment and electron donors, thereby promoting denitrification [28]. Notably, organic–inorganic co-application treatments (HTC, HHOC, and HTO) exhibited intermediate levels across all functional expressions, suggesting that rational nutrient management may partially balance soil microbial metabolic functions, mitigating the microbial functional imbalances caused by single fertilization methods [29]. Regarding key fungal functions (Figure 7B), the HCF treatment significantly enhanced the functional intensity of fungal parasites and plant pathogens. This result indicates that continuous chemical fertilizer application tends to simplify soil microbial community structure and enhance the relative competitive advantage of pathogenic fungi [30]. In contrast, the intensity of these two potentially harmful functions was lowest under the HOF treatment, suggesting that organic fertilizers may suppress pathogenic fungal proliferation to some extent by promoting soil microbial ecosystem stability [31]. Through microbial source tracing and correlation network analysis, this study further clarified the correspondence between key functions and specific microbial groups. The functions of key bacteria primarily originated from four genera, such as Lysobacter, Thauera, Pseudomonas, and Zoogloea (Figure 8A). Correlation network analysis revealed (Figure 8B) that, except for Pseudomonas, the other three bacterial genera were significantly associated with one of the four key functions. Thauera and Zoogloea are reported as core participants in soil denitrification processes, and Thauera possesses efficient denitrification genes enabling direct utilization of nitrate for denitrification [32]. Zoogloea primarily captures organic matter by secreting extracellular polymers, performing partial denitrification during organic matter decomposition [33]. Lysobacter serves as a “pioneer” in nutrient mineralization, rapidly converting organic nitrogen into inorganic nitrogen [34]. This study found that under HCF treatment, Thauera and Lysobacter exhibited the highest abundance, while Zoogloea dominated under HOF treatment. The combined application of organic and chemical fertilizers significantly reduced the abundance of Thauera and Lysobacter, maintaining Zoogloea abundance at an intermediate level between HCF and HOF treatments. This result indicates that under single chemical fertilizer application, Lysobacter rapidly converts soil nitrogen into available forms, which facilitates plant uptake but simultaneously provides ample substrate for Thauera, enhancing denitrification and accelerating soil nutrient loss. Conversely, under single organic fertilizer application, increased Zoogloea abundance boosted extracellular polymer secretion, enhancing organic matter decomposition, and although it exhibited some denitrification activity, it primarily accelerates organic matter breakdown and nutrient release. Thus, different fertilization treatments modulate soil fertility by altering physicochemical conditions and regulating the intensity of various links within the microbial network.

Figure 7.

Prediction model of functional and intensity analysis of key microorganisms in the rhizosphere soil of C. sinensis with the combined application of chemical and organic fertilizer. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively. (A) Functional enrichment and intensity analysis of key bacteria. (B) Functional enrichment and intensity analysis of key fungi.

Figure 8.

Microbial sources and correlation analysis of the prediction model of key functions under the combined application of chemical and organic fertilizers. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively. (A) Analysis of microbial sources and their quantitative trends for key bacterial functions. (B) Correlation network analysis between key bacterial functions and microbial quantity. (C) Analysis of microbial sources and their quantitative trends for key fungal functions. (D) Correlation network analysis between key fungal functions and microbial quantity.

Additionally, the two functions significantly enriched by the key fungi primarily originated from seven genera, i.e., Boletus, Purpureocillium, Ceratobasidium, Plectosphaerella, Phyllactinia, Stemphylium, and Xylogone (Figure 8C). Correlation network analysis revealed (Figure 8D) that, except for the genera Stemphylium, Xylogone, and Phyllactinia, the remaining four fungal genera showed significant associations with either fungal parasite or plant pathogen functions. Ceratobasidium and Plectosphaerella are reported as typical plant pathogens that invade plant roots and hinder nutrient uptake and utilization [35,36]. Boletus is an ectomycorrhizal fungus that survives saprophytically or parasitically under high nutrient concentrations [37]. Purpureocillium is a probiotic that reduces plant pest and disease infection rates while promoting plant growth [38]. This study found that Ceratobasidium, Plectosphaerella, and Boletus were most abundant under HCF treatment, least abundant under HOF treatment, and intermediate under organic fertilizer and chemical fertilizer co-application. Conversely, Purpureocillium was most abundant under HHOC treatment. These results indicate that sole chemical fertilizer application tends to cause substantial accumulation of soil-borne pathogenic fungi, increasing C. sinensis susceptibility to disease and hindering growth. Sole organic fertilizer application improves soil structure and reduces pathogenic fungal populations. Combined application of organic and chemical fertilizers ensures adequate nutrient supply while mitigating the negative effects of chemical fertilizers. Therefore, rational fertilizer combination represents a crucial technical pathway for achieving sustainable C. sinensis plantation development.

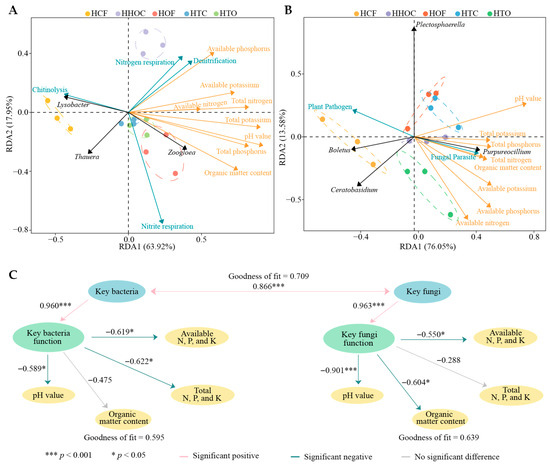

3.5. Analysis of Key Microorganisms, Their Functions, and Interactions with Different Indicators

To further elucidate the interaction networks among key microorganisms, functions, and soil environments, this study integrated Redundancy Analysis (RDA) with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). RDA results revealed (Figure 9A) that key bacteria and their functions were closely associated with soil physicochemical indicators. HCF treatment was strongly correlated with Lysobacter, Thauera, and chitinolysis, while HHOC treatment was strongly linked to nitrogen respiration, denitrification, available phosphorus, available potassium, available nitrogen, and total nitrogen. HOF, HTC, and HTO treatments were primarily associated with Zoogloea, total phosphorus, total potassium, pH value, and organic matter content. At the fungal level (Figure 9B), HCF treatment showed significant associations with Boletus, Ceratobasidium, and plant pathogens. HOF and HTC treatments corresponded to Plectosphaerella, total potassium, and pH value, while HHOC and HTO treatments were associated with Purpureocillium, fungal parasites, total phosphorus, total nitrogen, organic matter, available phosphorus, available potassium, and available nitrogen.

Figure 9.

Redundancy analysis of different indicators and construction of the PLS-SEM equation. Note: HCF, HTC, HHOC, HTO, and HOF represent chemical fertilizer treatment, 2/3 chemical fertilizer + 1/3 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/2 chemical fertilizer + 1/2 organic fertilizer treatment, 1/3 chemical fertilizer + 2/3 organic fertilizer treatment, and organic fertilizer treatment, respectively. (A) Redundancy analysis of key bacteria and their functions with soil physicochemical indicators. (B) Redundancy analysis of key fungi and their functions with soil physicochemical indicators. (C) Construction of PLS-SEM equations for key bacteria and fungi with different indicators.

Based on the aforementioned relationships, the further constructed PLS-SEM model quantified these interaction pathways. The model revealed (Figure 9C) a significant positive interaction between key bacterial and fungal communities (0.866***), indicating potential for synergy or symbiosis between them within the rhizosphere microecology. More importantly, both bacteria and fungi significantly positively regulated their respective functional expressions (bacterial path coefficient = 0.960*, fungal path coefficient = 0.963*); however, the functions mediated by both bacteria and fungi exhibited widespread negative effects on soil nutrient indicators. Thus, key microorganisms enhance soil nitrogen transformation (e.g., denitrification, respiration) and pathogen-associated metabolic activities, significantly depleting available nutrients while accelerating soil acidification and organic matter decomposition, and ultimately inhibiting soil fertility indicators [39,40]. This result indicates that while a single fertilizer application may temporarily boost certain available nutrients, it may ultimately stimulate denitrification processes represented by Thauera, leading to nitrogen loss and compromising soil health through enhanced pathogenic fungal activity [41]. Conversely, the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizer mitigated the intensity of these detrimental functional processes to some extent by regulating microbial community structure [42], thereby better supporting the long-term maintenance of C. sinensis plantation soil fertility and ecological stability.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically analyzed the comprehensive effects of different fertilization treatments on the physicochemical properties, microbial community structure, and ecological functions of C. sinensis rhizosphere soil. It was found that fertilization management directly and indirectly shaped the structure and function of rhizosphere microbial communities by altering the soil physicochemical environment. In turn, microbial responses influenced soil fertility quality and ecosystem stability through complex feedback mechanisms. Specifically, the single chemical fertilizer (HCF) treatment exacerbated soil acidification and reduced organic matter and nutrient content. Although it temporarily increased available nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contents, it significantly decreased bacterial and fungal community diversity. This treatment enriched nitrogen-transforming microorganisms (e.g., Lysobacter and Thauera) and, along with plant-pathogenic fungi (e.g., Ceratobasidium and Plectosphaerella), enhanced microbial functions such as nitrogen respiration, denitrification, and pathogenicity. This collectively formed a microecological pattern characterized by “high metabolic consumption and high pathogen pressure.” The single organic fertilizer (HOF) treatment demonstrated the best performance in elevating soil pH, organic matter, and total nutrient content. It effectively maintained high bacterial diversity and fungal migration/colonization capacity, promoted the proliferation of beneficial bacterial genera like Zoogloea, and significantly suppressed pathogenic fungal abundance and related functions, exhibiting a strong “ecological buffering” effect. The combined organic–inorganic fertilizer treatment excelled in maintaining balanced soil nutrient supply and improving available nutrient content, effectively balanced bacterial and fungal community structures, and optimized microbial diversity and stability. This approach mitigated pathogen accumulation and functional imbalances caused by sole chemical fertilizer application while compensating for the limited supply of available nutrients in sole organic fertilizer application, demonstrating advantages in “stabilizing structure, regulating function, and promoting balance” in microbial ecosystem regulation. In summary, long-term exclusive use of chemical fertilizers readily leads to soil microecological degradation and functional imbalance. In contrast, combined organic–inorganic fertilization—particularly patterns dominated by organic fertilizers—can mitigate negative feedback by optimizing microbial community structure and balancing functional expression. This study provides crucial insights for improving fertilization practices in C. sinensis plantations, advancing soil health management, and achieving sustainable agricultural development. However, this study only preliminarily explored the effects of different fertilization treatments on the rhizosphere soil microbial community and soil nutrient transformation of C. sinensis. The key microorganisms and their functions were based on software prediction. In subsequent research, it is necessary to isolate and purify key soil microorganisms and verify their functions to more effectively illustrate the actual impact of changes in key microorganisms on the growth of C. sinensis and soil nutrients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121497/s1, Table S1. Bioinformatics analysis workflow and methods for sequencing data.

Author Contributions

X.J. and Q.W.: Writing—original draft preparation, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation; T.W., Q.Z., J.G. and Y.L.: Writing—original draft preparation, conceptualization, formal analysis, validation; B.Z. and J.Y.: Writing—review and editing, data curation; H.W.: writing—review and editing, project administration, supervision, funding acquisition, resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32501404); Fujian Province University Industry–University Cooperation Project (2025N5013, 2025N0073); Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024N0009, 2024J01866, 2024J01861); Nanping City Science and Technology Plan Project (N2024Z010); Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (S202511312018; S202510397024); Wuyi University Horizontal Research Program (2023-WHFW-017); Open Fund Project of Fujian Key Laboratory of Big Data Application and Intellectualization for Tea Industry (Wuyi University) (FKLBDAITI202508, FKLBDAITI202504).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request. The Miseq raw reads were deposited in the China National Center for Bioinformation Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) database. The accession number is PRJCA048135 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA031329, 16 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shao, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Cai, P.; Jia, X.; Rensing, C.; Li, Q. Impact of tea tree cultivation on soil microbiota, soil organic matter, and nitrogen cycling in mountainous plantations. Agronomy 2024, 14, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, C.; Raza, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Fu, Y.; Hu, J.; Imoulan, A.; Hussain, M.; et al. Intercropping walnut and tea: Effects on soil nutrients, enzyme activity, and microbial communities. Front. Microbial. 2022, 13, 852342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chu, X.; Zhu, H.; Zou, D.; Li, L.; Du, L. The response of soil nutrients and microbial community structures in long-term tea plantations and diverse agroforestry intercropping systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yamashita, H.; Ikka, T. Exploring from soil acidification to neutralization in tea plantations: Changes in soil microbiome and their impacts on tea quality. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2025, 13, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xia, H.; Jiang, C.; Riaz, M.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Fan, X.; Xia, X. 14 year applications of chemical fertilizers and crop straw effects on soil labile organic carbon fractions, enzyme activities and microbial community in rice-wheat rotation of middle China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 841, 156608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Cui, S.; Wu, L.; Qi, W.; Chen, J.; Ye, Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, D. Effects of bio-organic fertilizer on soil fertility, yield, and quality of tea. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 5109–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Zahra, S.; Hussain, Q.; Waheed, U.; Rehman, M. Microbial diversity and its role in enhancing soil fertility: A comprehensive review. Res. Med. Sci. Rev. 2025, 3, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alori, E.T.; Osemwegie, O.O.; Ibaba, A.L.; Daramola, F.Y.; Olaniyan, F.T.; Lewu, F.B.; Babalola, O.O. The importance of soil microorganisms in regulating soil health. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2024, 55, 2636–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.C.; Grenni, P.; Onet, C.; Onet, A. Fertilization and soil microbial community: A review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, W.; Ye, Q.; Lv, W.; Liao, P.; Yu, J.; Mu, C.; Wu, L.; Muneer, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Effects of different nitrogen fertilizer rates on soil magnesium leaching in tea garden. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 6630–6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Gao, Y. The Effects of localized plant–soil–microbe interactions on soil nitrogen cycle in maize rhizosphere soil under long-term fertilizers. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, D.; Chen, X.; Hou, J.; Zhao, F.; Li, P. Soil properties and microbial functional attributes drive the response of soil multifunctionality to long-term fertilization management. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 192, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lan, X.; Hou, H.; Ji, J.; Liu, X.; Lv, Z. Multifaceted ability of organic fertilizers to improve crop productivity and abiotic stress tolerance: Review and perspectives. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Kang, J.; Chen, Y.; Hong, L.; Li, M.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; Wu, Z.; et al. Effects of long-term use of organic fertilizer with different dosages on soil improvement, nitrogen transformation, tea yield and quality in acidified tea plantations. Plants 2022, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, H.; Chandran, V.; Mathew, L. Organic fertilizers as a route to controlled release of nutrients. In Controlled Release Fertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, M. Influence on soil ecology, tea yield, and quality of tea plant organic cultivation: A mini-review. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1557723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Cui, Z.; Yao, S.; Li, G.; Yuan, J. Compost tea: Preparation, utilization mechanisms, and agricultural applications potential–A comprehensive review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Shen, C.; Zou, Z.; Fan, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, C.; Fu, J.; Han, W.; Shi, L. Increased soil fertility in tea gardens leads to declines in fungal diversity and complexity in subsoils. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Ding, D.; Duan, J.; Luo, Y.; Huang, F.; Kang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, S. Soil microbial community characteristics and their effect on tea quality under different fertilization treatments in two tea plantations. Genes 2024, 15, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, M. Chemical fertilizer reduction with organic fertilizer effectively improve soil fertility and microbial community from newly cultivated land in the Loess Plateau of China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 165, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Lin, S.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z. Study on the effect of pH on rhizosphere soil fertility and the aroma quality of tea trees and their interactions. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Advanced R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC The R Series; Taylor and Francis: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hong, L.; Jia, X.; Kang, J.; Lin, S.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H. Improvement of soil acidification in tea plantations by long-term use of organic fertilizers and its effect on tea yield and quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1055900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisseler, D.; Scow, K.M. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms–A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Sachan, K.; Baskar, P.; Saikanth, D.R.K.; Lytand, W.; Kumar, R.K.M.; Singh, B.V. Soil microbes expertly balancing nutrient demands and environmental preservation and ensuring the delicate stability of our ecosystems-a review. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2023, 35, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, I.; Fujita, H.; Toju, H. Deterministic and stochastic processes generating alternative states of microbiomes. ISME Commun. 2024, 4, ycae007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Zhou, X.; Yu, H.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, K.; Du, X.; Lu, G.; et al. Microbial and chemical fertilizers for restoring degraded alpine grassland. Biol. Fert. Soils 2023, 59, 911–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hu, Z.; Tan, G.; Fan, J.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhi, Q.; Liu, T.; Yin, H.; et al. Enhancing plant growth in biofertilizer-amended soil through nitrogen-transforming microbial communities. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1259853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahala, D.M.; Maheshwari, H.S.; Yadav, R.K.; Prabina, B.J.; Bharti, A.; Reddy, K.K.; Kumawat, C.; Ramesh, A. Microbial Transformation of Nutrients in Soil: An Overview; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.F.; Li, X.Y.; Chen, S.C.; Jin, B.J.; Wu, C.Y.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, X.Y. Nitrogen fertilization modulates rice phyllosphere functional genes and pathogens through fungal communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zheng, T.; Yan, W.; Rensing, C.; Wu, H.; Wu, W.; Wu, H. Substitution of chemical fertilizer by biogas slurry maintain wheat yields by regulating soil properties and microbiomes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhou, G.; Teng, X.; Hou, W.; Huang, X.; Yu, J.; Mei, Y. Deep insight into the effect of Ni (II) in biofilm-activated sludge system: Nitrogen removal, biofilm formation and microbial characteristics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Du, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Han, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Sun, Y. Impact of N loading on microbial community structure and nitrogen removal of an activated sludge process with long SRT for municipal wastewater treatment. Water Cycle 2025, 6, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, R.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Q.; Song, J.; Duan, J.; Li, H.; Gao, X.; Chen, M.; et al. Microplastics affect organic nitrogen in sediment: The response of organic nitrogen mineralization to microbes and benthic animals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 485, 136926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landicho, D.M.; Montañez, R.J.M.; Camagna, M.; Neang, S.; Bulasag, A.S.; Magdaraog, P.M.; Sato, I.; Takemoto, D.; Maejima, K.; Pinili, M.S.; et al. Status of cassava witches’ broom disease in the Philippines and identification of potential pathogens by metagenomic analysis. Biology 2024, 13, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ali, Q.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Yao, H.; Chong, J.; Gu, Q.; Wu, H.; et al. Role of iturin from Bacillus velezensis DMW1 in suppressing growth and pathogenicity of Plectosphaerella cucumerina in tomato by reshaping the rhizosphere microbial communities. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 296, 128150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ediriweera, A.N.; Lu, W.; Perez Moreno, J.; Kalamulla, R.; Mayadunna, N.; Pelewatta, A.; Dissanayake, G.; Maduwanthi, I.; Wijesooriya, M.; Dai, D.; et al. Ectomycorrhizal fungal symbiosis on plant nutrient acquisition in tropical ecosystems. N. Z. J. Bot. 2025, 63, 1871–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigobelo, E.C.; Nicodemo, D.; Babalola, O.O.; Desoignies, N. Purpureocillium lilacinum as an agent of nematode control and plant growth-promoting fungi. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, D.; Prakash, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, F. Mitigation strategies for soil acidification based on optimal nitrogen management. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, X.; Bai, S.H.; Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, B.; et al. Bacterial communities driving cabbage yield increases and pathogenic risks reduces following wastewater irrigation: Effects of nitrification inhibitors on different soil-vegetable systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 214, 106324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasilnikov, P.; Taboada, M.A.; Amanullah. Fertilizer use, soil health and agricultural sustainability. Agriculture 2022, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamdad, H.; Papari, S.; Lazarovits, G.; Berruti, F. Soil amendments for sustainable agriculture: Microbial organic fertilizers. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).