Micropropagation of Quillaja saponaria: A Biotechnological Solution for Conservation and Sustainable Commercial Use of This Endemic Chilean Woody Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Surface Sterilization of Plant Material

2.3. In Vitro Multiplication

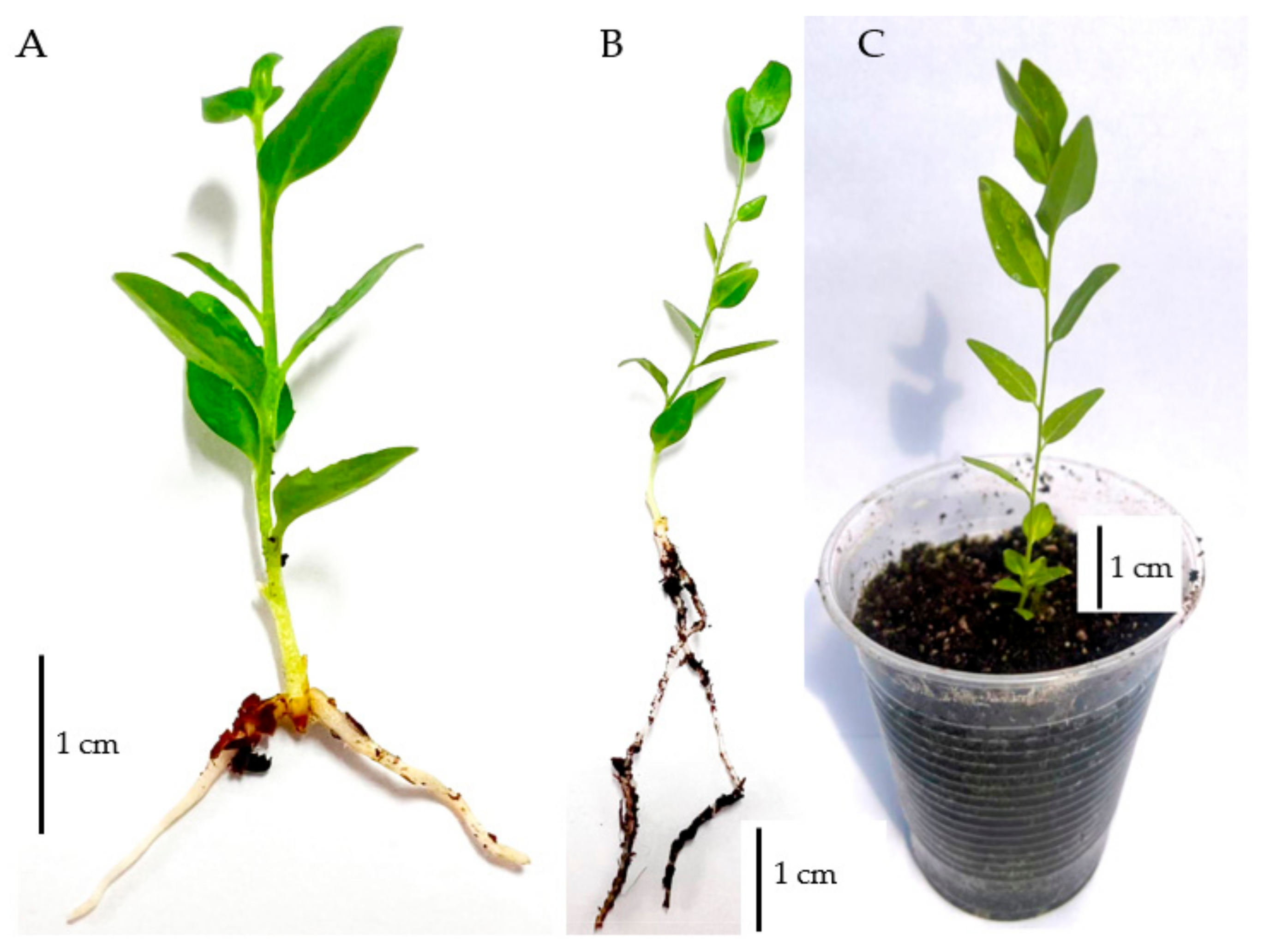

2.4. Ex Vitro Rooting and Acclimatization

3. Results

3.1. Surface Sterilization of Plant Material

3.2. In Vitro Multiplication

3.3. Ex Vitro Rooting and Acclimatization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guerra, F.; Sepúlveda, S. Saponin Production from Quillaja Genus Species. An Insight into Its Applications and Biology. Sci. Agric. 2021, 78, e20190305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, S.; Peña, K.; Pacheco, C.; Luna, G.; Aguirre, A. Respuesta Fisiológica y de Crecimiento en Plantas de Quillaja saponaria y Cryptocarya alba Sometidas a Restricción Hídrica. Bosque 2011, 32, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti-Ruiz, S.; Delard, R.; González-Ortega, M.; Roach-Barrios, F.A. Monografía de Quillay Quillaja Saponaria; INFOR: Santiago, Chile, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, R.; Matthei, O.; Quesada, M. Flora Arbórea de Chile; Editorial Universidad de Concepción: Concepción, Chile, 1983; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Lagos, J. Antecedentes Bibliográficos de Quillay (Quillaja saponaria Mol.) y Estudio de un Bosque Natural Ubicado en la Provincia del Bío Bío; Memoria para optar al título de Ingeniero Forestal, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad de Concepción: Concepción, Chile, 1998; p. 100. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.ciren.cl/bitstreams/9539cf57-1d6f-437e-b70c-25a754593b1c/download (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Espinoza, S.E.; Quiroz, I.A.; Magni, C.R.; Yáñez, M.A.; Martínez, E.E. Long-Term Effects of Copper Mine Tailings on Surrounding Soils and Sclerophyllous Vegetation in Central Chile. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milla-Moreno, E.; Guy, R.D. Growth Response, Uptake and Mobilization of Metals in Native Plant Species on Tailings at a Chilean Copper Mine. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2021, 23, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Martin, R.; Briones, R. Industrial Uses and Sustainable Supply of Quillaja saponaria Saponins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 70, 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Podolak, I.; Galanty, A.; Sobolewska, D. Saponins as Cytotoxic Agents: A Review. Phytochem. Rev. 2010, 9, 425–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, J.D.; Betti, A.H.; Da Silva, F.P.; Troian, E.A.; Olivaro, C.; Ferreira, F.; Verza, S.G. Saponins from Quillaja saponaria and Quillaja brasiliensis: Particular Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activities. Molecules 2019, 24, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keech, C.; Albert, G.; Reed, P.; Neal, S.; Plested, J.S.; Zhu, M.; Cloney-Clark, S.; Zhou, H.; Patel, N.; Frieman, M.B. First-in-Human Trial of a SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Spike Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine. Lancet 2020, 396, 467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Stertman, L.; Palm, A.E.; Zarnegar, B.; Carow, B.; Lunderius Andersson, C.; Magnusson, S.E.; Carnrot, C.; Shinde, V.; Smith, G.; Glenn, G.; et al. The Matrix-M™ Adjuvant: A Critical Component of Vaccines for the 21st Century. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2189885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF). Catastro y Evaluación de los Recursos Vegetacionales Nativos de Chile; CONAF: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, F. Factores limitantes y estrategias de establecimiento de plantas leñosas en ambientes semiáridos. Implicaciones para la restauración. Ecosistemas 2008, 17, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- George, E.F.; Hall, M.A.; De Klerk, G.J. Plant Propagation by Tissue Culture. Volume 1: The Background; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prehn, D.; Serrano, C.; Berríos, C.G.; Arce-Johnson, P. Micropropagation of Quillaja saponaria Mol. starting from seed. Bosque 2003, 24, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cob Uicab, J.V.; Ríos Leal, D.; Sabja, A.M.; Cartes Riquelme, P.; Sánchez Olate, M. Organogenesis for in vitro propagation of Quillaja saponaria Molina in southern South America. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2017, 7, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Prehn, D.; Vega, A. In vitro initiation and early maturation of embryogenic tissue of Quillaja saponaria. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. (IJANR) 2005, 32, 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Aronen, T.; Sota, V.; Cvjetković, B.; Christie, B.; Rupps, A.; Fischerová, L.; Rathore, D.S.; Werbrouck, S.P.O. From lab to forest: Overcoming barriers to in vitro propagation of forest trees. J. For. Res. 2025, 36, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.P.R.; Wawrzyniak, M.K.; Ley López, J.M.; Kalemba, E.M.; Mendes, M.M.; Chmielarz, P. 6-Benzylaminopurine and kinetin modulations during in vitro propagation of Quercus robur (L.): An assessment of anatomical, biochemical, and physiological profiling of shoots. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2022, 151, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.A.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wai, M.H.; Rizwan, H.M.; An, C.; Aslam, M.; Zhang, C.; Wang, G.; et al. A highly efficient organogenesis system based on 6-benzylaminopurine and indole-6-butyric acid in Suaeda glauca—A medicinal halophyte under varying photoperiods. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 216, 118672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelak, M.; Pacholczak, A.; Nowakowska, K. Challenges and insights in the acclimatization step of micropropagated woody plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024, 159, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, R.; Basile, G.N.; De Mastro, G.; Gargano, M.L.; Tagarelli, A.; Ruta, C. Efficient micropropagation by ex vitro rooting of Myrtus communis L. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Kataria, V.; Shekhawat, N.S. In vitro propagation, ex vitro rooting and leaf micromorphology of Bauhinia racemosa Lam.: A leguminous tree with medicinal values. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, R.C. In Vitro Propagation of Quillaja saponaria Using Nodal Segments. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 2010, 70, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M.; Roveraro, C. In vitro culture of Quillaja saponaria Mol. (Soap-Bark Tree), Rosaceae. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2004, 69, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez, F. Atlas Agroclimático de Chile. Estado Actual y Tendencias del Clima. Tomo III: Regiones de Valparaíso, Metropolitana, O’Higgins y Maule; Fundación para la Innovación Agraria: Santiago, Chile, 2017; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Winarto, B.; Dobránszki, J.; Zeng, S. Disinfection Procedures for In Vitro Propagation of Anthurium. Folia Hortic. 2015, 27, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monier, C.; Ochatt, S.J. Establishing Micropropagation Conditions for Five Cotoneaster Genotypes. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1995, 42, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathwell, R.; Shukla, M.R.; Jones, A.M.P.; Saxena, P.K. In Vitro Propagation of Cherry Birch (Betula lenta L.). Can. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 96, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Badilla, L.; Cautin, R.; Castro, M. Micropropagation of Citronella mucronata D. Don, a Vulnerable Chilean Endemic Tree Species. Plants 2022, 11, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Badilla, L.; Cautín, R.; Castro, M. In Vitro Propagation of Peumus boldus Mol., a Woody Medicinal Plant Endemic to the Sclerophyllous Forest of Central Chile. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, P.; Rana, J.S.; Sindhu, A.; Jamdagni, P. Effect of Additives on Enhanced In Vitro Shoot Multiplication and Their Functional Group Identification of Chlorophytum borivilianum Sant. Et Fernand. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, K.; Pacholczak, A.; Tepper, W. The Effect of Selected Growth Regulators and Culture Media on Regeneration of Daphne mezereum L. ‘Alba’. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. Nat. 2019, 30, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, V.; Pathak, A.; Stikhareva, T.; Ercisli, S.; Daulenova, M.; Kazangapova, N.; Rakhimzhanov, A. In Vitro Propagation and Ex Vitro Rooting of Euonymus verrucosus Scop. (Celastraceae)—A Rare Species of Kazakhstan Flora on the Southern Border of Its Areal. J. For. Res. 2022, 27, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.S.; Cordeiro-Silva, R.; Degenhardt-Goldbach, J.; Quoirin, M. Micropropagation of Calophyllum brasiliense (Cambess.) from Nodal Segments. Braz. J. Biol. 2016, 76, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotov, A.A.; Kotova, L.M. Auxin/cytokinin antagonism in shoot development: From moss to seed plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 6391–6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, M.E.; Awad, A.A.; Majrashi, A.; Abd Esadek, O.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Gendy, A.S. In vitro study on the effect of cytokines and auxins addition to growth medium on the micropropagation and rooting of Paulownia species (Paulownia hybrid and P. tomentosa). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 1598–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachou, G.; Papafotiou, M. Efficient Micropropagation Using Different Types of Explant and Addressing the Hyperhydricity of Ballota acetabulosa, a Mediterranean Plant with High Xeriscaping Potential. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, E.J.; Rodriguez, M.N.; Tommasino, E.; Ruolo, S.; Grunberg, K. Effect of different cytokinin concentrations on establishing an in vitro micropropagation system for hop (Humulus lupulus L.). N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2025, 53, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliem, M.K.; Abdalla, N.; El-Mahrouk, M.E. Cytokinin Potentials on In Vitro Shoot Proliferation and Subsequent Rooting of Agave sisalana Perr. Syn. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaičiukynė, M.; Žiauka, J.; Černiauskas, V.; Varnagirytė-Kabašinskienė, I. Role of Plant Growth Regulators in Adventitious Populus Tremula Root Development In Vitro. Plants 2025, 14, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seka, J.S.S.; Kouassi, M.K.; Yéo, E.F.; Saki, F.M.; Otron, D.H.; Tiendrébéogo, F.; Eni, A.; Kouassi, N.K.; Pita, J.S. Removing recalcitrance to the micropropagation of five farmer-preferred cassava varieties in Côte d’Ivoire by supplementing culture medium with kinetin or thidiazuron. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1538799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cai, S.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Huang, R.; Yu, Y.; Wen, M.; Xu, T. High auxin stimulates callus through SDG8-mediated histone H3K36 methylation in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruski, K.W.; Lewis, T.; Astatkie, T.; Nowak, J. Micropropagation of Chokecherry and Pincherry Cultivars. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2000, 63, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowska, B. Morphological and Physiological Characteristics of Micropropagated Strawberry Plants Rooted In Vitro or Ex Vitro. Sci. Hortic. 2001, 89, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, M.S.; Manokari, M.; Revathi, J. In Vitro Propagation and Ex Vitro Rooting of Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. Ex Schult.: A Rare Medicinal Plant. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 22, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erst, A.; Gorbunov, A.; Karakulov, A. Rooting and Acclimatization of In Vitro Propagated Microshoots of the Ericaceae. J. Appl. Hortic. 2018, 20, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suharyanto, S.; Forestry, S.; Rahayu, W.; Lopez, G.A. Ex Vitro Rooting in Acacia crassicarpa Micropropagation. Development and Application of Vegetative Propagation Technologies in Plantation Forestry to Cope with Changing Climate and Environment. In Proceedings of the IUFRO Conference, Beijing, China, 24–27 October 2016; Volume 100. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, P.; Sousa, A.; Costa, A.; Santos, C.A. Protocol for Ulmus minor Mill. Micropropagation and Acclimatization. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2007, 92, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robres-Torres, E.; López-Medina, J.; Rocha-Granados, M.C. Adventitious Shoot Elongation of Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) Is Influenced by Brassinosteroids. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc 2015, 6, 991–999. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, J.S.; Rathore, V.; Shekhawat, N.S.; Singh, R.P.; Liler, G.; Phulwaria, M.; Dagla, H.R. Micropropagation of Woody Plants. In Plant Biotechnology and Molecular Markers; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Xu, X.D.; Dai, H.; Chen, L.Q. Direct Regeneration of Plants Derived from In Vitro Cultured Shoot Tips and Leaves of Three Lysimachia Species. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 122, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Mohammadi, R. Establishment of an Efficient In Vitro Propagation Protocol for Sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) and Confirmation of the Genetic Homogeneity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Badilla, L.; Cautín, R.; Castro, M. In Vitro Propagation Protocol for Porlieria chilensis: Efficient Ex Vitro Rooting and Acclimatization. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Camba, R.; Proietti, S.; Sánchez, C. Reducing costs, improving profits: A low-cost culture media for woody plants micropropagation. J. For. Sci. 2023, 69, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Cytokinins Concentration |

|---|---|

| Control | 0 μM untreated |

| BAP1 | 1.11 μM |

| BAP2 | 2.22 μM |

| BAP3 | 4.44 μM |

| ZEA1 | 0.46 μM |

| ZEA2 | 1.37 μM |

| ZEA3 | 2.74 μM |

| 2-iP1 | 0.49 μM |

| 2-iP2 | 1.23 μM |

| 2-iP3 | 2.46 μM |

| Treatment | Fungal Contamination (%) | Bacterial Contamination (%) | Oxidation (%) | Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaClO: 0% | 50.84 ± 3.12 a,* | 22.50 ± 2.16 a,* | 9.16 ± 1.09 b | 17.50 ± 1.17 d |

| NaClO: 0.5% | 19.16 ± 2.05 b | 12.50 ± 1.33 ab | 13.34 ± 2.01 b | 55.55 ± 2.15 b |

| NaClO: 1.0% | 4.99 ± 1.17 c | 4.16 ± 1.01 b | 6.65 ± 1.95 b | 84.17 ± 3.03 a,* |

| NaClO: 1.5% | 12.50 ± 1.81 bc | 13.34 ± 1.77 ab | 37.50 ± 2.55 a,* | 36.66 ± 2.22 c |

| F treatment | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 |

| F ecotype | p = 0.984 | p = 0.938 | p = 0.433 | p = 0.913 |

| F treatment × ecotype | p = 0.964 | p = 0.987 | p = 0.563 | p = 0.880 |

| Treatment | Shoot Length (cm) | Proliferation Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.98 ± 0.12 e | 1.00 ± 0.10 e |

| 1.11 μM BAP | 3.90 ± 0.55 c | 1.95 ± 0.18 c |

| 2.22 μM BAP | 5.21 ± 0.77 b | 2.61 ± 0.20 b |

| 4.44 μM BAP | 8.01 ± 1.03 a,* | 4.04 ± 0.33 a,* |

| 0.46 μM ZEA | 2.24 ± 0.33 e | 1.15 ± 0.13 e |

| 1.37 μM ZEA | 2.78 ± 0.23 d | 1.39 ± 0.11 d |

| 2.74 μM ZEA | 3.85 ± 0.44 c | 1.93 ± 0.22 c |

| 0.49 μM 2-iP | 2.79 ± 0.20 d | 1.40 ± 0.10 d |

| 1.23 μM 2-iP | 2.82 ± 0.17 d | 1.41 ± 0.17 d |

| 2.46 μM 2-iP | 1.94 ± 0.18 e | 1.00 ± 0.11 e |

| F treatment | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 |

| F ecotype | p = 0.072 | p = 0.031 |

| F treatment × ecotype | p = 0.522 | p = 0.544 |

| Treatment | Rooting (%) | Acclimatization Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 e | 0 b |

| 492.03 μM IBA | 51.42 ± 3.17 c | 87.14 ± 5.78 a,* |

| 984.06 μM IBA | 92.85 ± 4.88 a,* | 85.71 ± 4.23 a |

| 1476 μM IBA | 77.14 ± 4.07 b | 84.30 ± 3.39 a |

| 537.04 μM NAA | 21.43 ± 2.23 d | 87.16 ± 4.76 a |

| 1074.08 μM NAA | 54.28 ± 3.08 c | 85.23 ± 3.97 a |

| 1611.11 μM NAA | 54.30 ± 3.29 c | 84.28 ± 3.84 a |

| F treatment | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 |

| F ecotype | p = 0.772 | p = 1.000 |

| F treatment × ecotype | p = 1.000 | p = 0.973 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerra, F.; Montecinos, M.; Salgado, I.; González, J.; Cautín, R.; Castro, M. Micropropagation of Quillaja saponaria: A Biotechnological Solution for Conservation and Sustainable Commercial Use of This Endemic Chilean Woody Species. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121498

Guerra F, Montecinos M, Salgado I, González J, Cautín R, Castro M. Micropropagation of Quillaja saponaria: A Biotechnological Solution for Conservation and Sustainable Commercial Use of This Endemic Chilean Woody Species. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121498

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerra, Francesca, Miriam Montecinos, Ingrid Salgado, Javier González, Ricardo Cautín, and Mónica Castro. 2025. "Micropropagation of Quillaja saponaria: A Biotechnological Solution for Conservation and Sustainable Commercial Use of This Endemic Chilean Woody Species" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121498

APA StyleGuerra, F., Montecinos, M., Salgado, I., González, J., Cautín, R., & Castro, M. (2025). Micropropagation of Quillaja saponaria: A Biotechnological Solution for Conservation and Sustainable Commercial Use of This Endemic Chilean Woody Species. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121498