Abstract

Bougainvillea spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ is a relatively cold-tolerant variety, but its low pollen viability and poor seed set have limited large-scale reproduction. To establish an efficient propagation protocol, cuttings from three types of Bougainvillea spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ were treated with varying concentrations of exogenous indole-3-butyric acid (IBA). Rooting parameters, growth indicators, and physiological metrics were measured, and the optimal treatment was identified through comprehensive membership function evaluation. The results showed that cutting types significantly influenced rooting, root development, plant growth, organic compound content (soluble sugars, starch, and protein), and abscisic acid (ABA) content. Conversely, IBA concentration significantly affected rooting, root architecture, polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity, and the levels of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and Brassinolide (BR). This comprehensive evaluation identified lignified shoots (LS) treated with 100 mg/L IBA (LS-100) as the optimal protocol, which achieved a rooting rate of 63% and significantly improved root formation, plant growth, root activity, organic compound content, PPO activity, and the levels of IAA and BR. This study provides valuable insights and technical guidance for the large-scale cutting propagation of Bougainvillea spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’.

1. Introduction

Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd., an evergreen woody climbing shrub of the Nyctaginaceae family, is commonly cultivated in warm, humid, and sunny environments [1]. It is widely used in landscaping due to its diverse cultivars, colorful bracts, and prolonged flowering period [2]. However, Bougainvillea species are generally sensitive to cold [3]. This limits their ability to overwinter outdoors in central and northern China [4]. In a previous study [5], Bougainvillea spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ was identified as the most cold-tolerant cultivar in Hubei Province.

However, Bougainvillea propagation is constrained by narrow floral tubes, low pollen viability, and poor seed set, which hampers the mass production of high-quality seedlings [6]. To address these challenges, cutting propagation has been employed as an effective asexual method that relies on plant cell totipotency [7], preserving genetic integrity while maintaining desirable parental traits and enhancing multiplication efficiency [8].

The adventitious rooting capacity of cuttings is influenced by both intrinsic factors (such as cutting diameter, cutting strength, nutrient content, and hormone levels of cuttings) and external factors (including humidity, temperature, and exogenous hormone application) [9,10]. In general, one-year-old cuttings exhibit better rooting capacity than two-year-old cuttings due to their advantageous physiological conditions, including higher levels of endogenous hormones, enzyme activity, and nutrient content [11]. During cutting propagation, endogenous hormones, particularly Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellin (GA), brassinolide (BR), and zeatin riboside (ZR), play essential regulatory roles in adventitious root initiation, root development, and plant growth [12]. Moreover, oxidase enzymes, including peroxidase (POD), polyphenol oxidase (PPO), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), also contribute to root development. PPO enzymes promote callus and adventitious root formation by catalyzing the complexation of IAA with phenolic compounds [13], while SOD enzymes protect plant cells from oxidative damage by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) during cutting propagation [14]. And POD enzymes stimulate the formation of root primordium cells and eliminate H2O2 content [15].

Furthermore, cuttings lose direct nutrient supply after being detached from the mother plant. Therefore, carbon and nitrogen compounds are essential for cuttings to serve as substantial energy and nutrient resources for callus formation and root development [16]. Some studies [17,18] have demonstrated that older cuttings exhibit higher survival rates than younger ones, attributed to their higher nutrient reserves.

Among external factors, hormonal regulation is the most effective approach to promote adventitious root formation [19]. IBA (indole-3-butyric acid), an exogenous hormone, is a natural precursor of IAA with high light stability, resulting in more stable and efficient adventitious root induction upon application [19]. The efficacy of IBA led to its widespread adoption in woody plant propagation, as optimal concentrations showed species-specific variation [11,20].

To identify optimal rooting treatments that integrate both intrinsic characteristics and external factors, researchers have increasingly employed the method combining principal component analysis with comprehensive membership function evaluation [21,22]. This approach enables the establishment of highly efficient cutting propagation systems. Therefore, the integrated approach was employed to assess the rooting capability of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings by comparing rooting capacity, growth traits, and physiological indicators across three cutting types under different IBA concentrations. The findings provide a scientific experimental methodology for rapid B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ propagation, with both theoretical relevance and practical value.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Site

This experiment was conducted from April to August 2021 in a greenhouse at the West Campus of Yangtze University in Jingzhou, Hubei, China (112°15′ E, 30°36′ N). The greenhouse was maintained under a natural photoperiod (12/12 h, day/night), with temperature ranging from 20 °C (night minimum) to 41 °C (day maximum) and relative humidity between 70% and 85%.

2.2. Preparation of Experimental Materials

Healthy cuttings of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ were collected from five-year-old mother plants, sourced from Yibin Sijin Landscape Co., Ltd. in Yibin City, Sichuan Province, China.

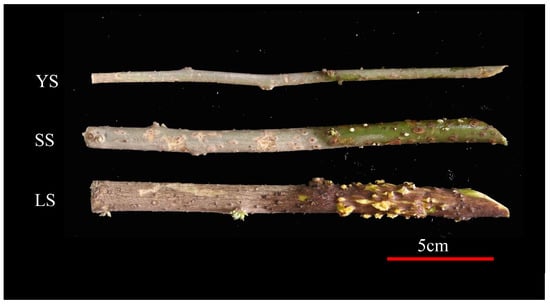

Three types of cuttings were prepared (Figure 1): lignified shoots (LS; 13.2 ± 0.5 mm Ø), semi-lignified shoots (SS; 11.2 ± 0.5 mm Ø), and young lignified shoots (YS; 7.3 ± 0.5 mm Ø). All cuttings were trimmed to 20 cm in length, with leaves removed and three latent buds retained. The base was cut at a 45° angle, and the top was trimmed flat. The growth substrate was an equal-volume mixture of river sand, perlite, vermiculite, and coco peat (Jiangsu Peilei Substrate Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). Sterilization was performed using 0.1% carbendazim for six hours (Shanghai Haohong Biomedicine Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). After that, cuttings were inserted into the substrate to one-third of their length, watered thoroughly by overhead sprinkling (the volume soil water content was approximately 37%), and the entire cutting bed was shaded with a shading net (50–70% nominal shade rate; Changzhou Green Netting Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China). Cuttings were watered via overhead sprinkling at 20 mL per plant every two days (after 48 h, the volume of soil water content was around 30%) under greenhouse conditions. All cuttings were maintained under greenhouse conditions for growth.

Figure 1.

Lignified shoots (LS), Semi-lignified shoots (SS), and Young lignified shoots (YS) of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’.

2.3. Treatments and Research Design

The experiment employed a two-factor completely randomized design, incorporating four concentrations of exogenous IBA (CAS: 133-32-4, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). IBA was initially dissolved in ethanol before being diluted with water. The design also included three types of cuttings, resulting in 12 treatment combinations (Table 1). Each treatment consisted of 40 potted cuttings. The experiment commenced on April 10, with each cutting receiving the basal drench of 20 mL of the corresponding IBA solution monthly, for a total of four applications over the experimental period. After 120 days, survival rate, rooting rate, and growth indicators were recorded. Additionally, leaf and root samples were immediately collected in liquid nitrogen for subsequent analysis of various physiological parameters.

Table 1.

B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings treatment.

2.4. Data Collection

The volume soil water content was monitored using a Spectrum TDR350 m (Spectrum Technologies Inc., New Orleans, LA, USA). Plants height and branch length of the cuttings were measured in centimeters using a straightedge. Rooting rate was evaluated at day 120, followed by root sample collection and root system analysis. Root morphological parameters, including total root length, total projected area, total surface area, average diameter, and total volume, were determined and analyzed using a WinRHIZO root analysis system (WinRHIZO version 2012b, Regent Instruments, Montreal, QC, Canada). Rooting percentage and rooting index were calculated as follows:

Rooting percentage = rooted cuttings/total cuttings × 100

Rooting Index = rooting rate × average root length × average root number

Additionally, the content of key organic compounds (Soluble sugar, soluble starch, and soluble protein content), along with superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, peroxidase (POD) activity, and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity of leaves and the root activity were measured according to the methods described in the Plant Physiology Experiment Tutorial by Tang Shaohu [23]. Adventitious root samples from each treatment were collected, rinsed clean, and preserved in dry ice and sent to China Agricultural University for the determination of endogenous hormone levels using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

The data were entered into Excel 2016 and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), Duncan’s multiple comparison test, and principal component analysis (PCA) with IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.1. Figures were prepared using Origin 2021.

3. Results

3.1. Rooting Analysis of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

3.1.1. Root System Morphology of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

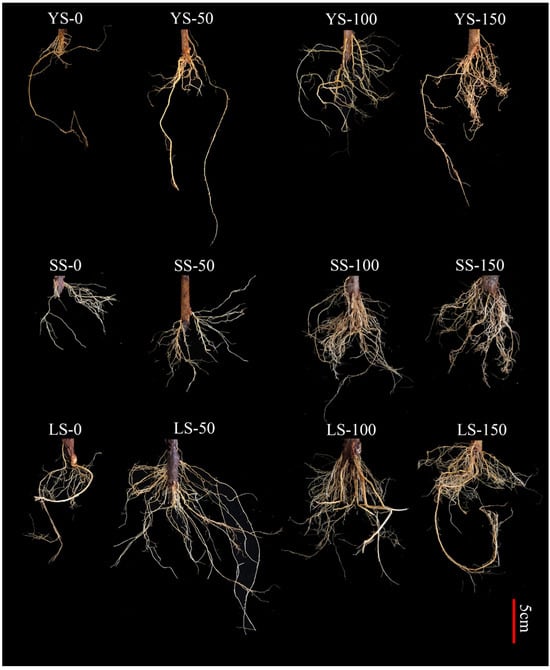

Root growth morphology of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings was significantly influenced by IBA concentration and cutting type (Figure 2). Sparse root systems were observed in YS-type cuttings, compared to SS and LS types. SS-type cuttings produced fine and densely branched roots, whereas the LS types developed harder, longer, and more extensive root systems. Moreover, IBA treatment significantly improved root development and exhibited an extensive root system, particularly at concentrations of 100 and 150 mg/L, compared to the untreated control.

Figure 2.

Root system morphology of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0 mg/L, 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) cuttings after 120 days.

3.1.2. Rooting Indicators of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

In this study, a survival rate of 81% and an overall rooting rate of 42% were recorded for B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings. Among the treatments, the maximum number of adventitious roots (30 and 27) was produced by SS-50 and SS-100, respectively, with no statistical differences among them; however, the minimum (10 and 13.33) was observed in YS-50 and YS-150, respectively, showing no significant difference (Table 2). The longest adventitious root length was observed with no statistical differences with all the results, including the letter ‘a’ in the same column (Table 2). The highest survival rate (98%) was achieved by LS-100, while no significant difference was shown among LS (0, 50,100, and 150) and SS-100 (Table 2). The maximum rooting rate (63%) was shared by LS-50 and LS-100, while the minimum (20%) was recorded in SS-0 and YS-0 (Table 2). The rooting index ranged from 18.44 (YS-0) to 126.47 (LS-100), the maximum rooting index was LS-100 (126.47) and SS-100 (111.93) (Table 2). Root fresh weight reached its maximum in LS-100 (3.57 g) and its minimum in YS-0 (0.68 g) and YS-50 (0.7 g) (Table 2). The maximum root length did not differ significantly among most treatments. Additionally, SS-0 differed significantly from both SS-50 and YS-100. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rooting indexes of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0 mg/L, 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) cuttings after 120 days.

3.1.3. Root Morphology Indexes of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

Significant differences were observed among different treatment groups of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ in terms of total root length, root projected area, total root surface area, total root volume, and average root diameter (Table 3). The combination of lignified shoots and 100 mg/L IBA (LS-100) was identified as the optimal condition for root system development. This treatment combination resulted in the maximum values for root projected area (40.83 cm2), total root surface area (123.06 cm2), and total root volume (5.35 cm3). Total root length was maximized under SS-100 (532.33 mm) and LS-100 (497.28 mm), while the poorest performance was consistently observed across all parameters in the YS-0 control group.

Table 3.

Root morphology indexes of cuttings of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0 mg/L, 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) cuttings after 120 days.

3.2. Growth Analysis of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

3.2.1. Growth Morphology of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

The growth morphology of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings was significantly influenced by both exogenous IBA concentration and cutting type (Figure 3). Across all cutting types, IBA-treated cuttings exhibited superior growth, with more and longer branches compared to the untreated controls. Furthermore, cuttings derived from LS and SS types demonstrated significantly better growth performance than those from YS branches. These YS cuttings produced fewer and shorter branches.

Figure 3.

Growth morphology of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L) after 120 days. (a) Young lignified (YS), (b) semi-lignified (SS), and (c) lignified (LS) Cuttings.

3.2.2. Growth Indicators of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

The maximum plant height was recorded in LS-150 and SS-100, significantly differing from the minimum observed in YS-0 and in others as well. The highest plant in YS, SS, and LS cuttings was YS-100, SS-100, and LS-150, respectively (Table 4). Branch numbers varied significantly with cutting type. Specifically, LS cuttings consistently produced more branches than SS or YS types. Furthermore, no significant differences in branch numbers were associated with IBA concentration. The maximum branch numbers were recorded in LS-0, LS-100, and LS-150, with no significant differences among these treatments (Table 4). Branch length, however, was affected by both cutting type and IBA concentration. The longest branches were observed in SS-100 and LS-50, which were significantly longer than those in YS-150, recording the shortest branches (Table 4).

Table 4.

Growth indicators of Cuttings of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) Cuttings after 120 days.

3.3. Physiological and Biochemical Analysis in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings

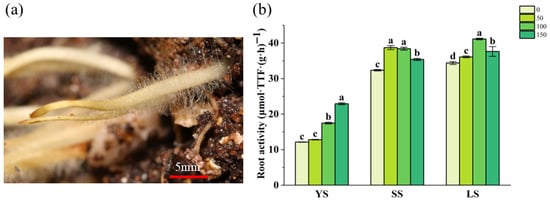

3.3.1. Root Activity in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’

The apical 1 cm segment of the root tips (Figure 4a) from B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings was used for the measurement of root activity. It was observed (Figure 4b) that root activity was higher in LS and SS than in YS cuttings. Compared to the control groups without IBA, root activity significantly increased in most IBA-treated cuttings (YS, SS, and LS), except for the YS-50. The optimal IBA concentration for root activity was 150 mg/L in YS, 50 and 100 mg/L in SS, and 100 mg/L in LS.

Figure 4.

Observations of root tip morphology (a) and analysis of root system activity (b) in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) Cuttings after 120 days. Note: The above statistical data are the average of three replicates. Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.3.2. Oxidase Activity in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’

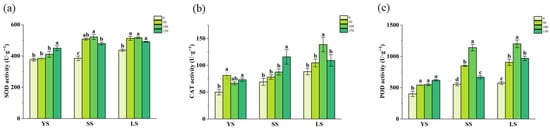

The oxidase activities in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ were measured (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

SOD (a), CAT (b), and POD (c) activities in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) Cuttings after 120 days. Note: The above statistical data are the average of three replicates. Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

The highest SOD activity (Figure 5a) was observed in YS at 150 mg/L IBA and in SS at 50 and 100 mg/L IBA, respectively. However, in LS cuttings, SOD activity showed no significant response to IBA treatments, while it was markedly higher than in the no-hormone treatment.

For the CAT activity, the optimal IBA concentrations were 150 mg/L for SS and 100 mg/L for LS. Nevertheless, no significant difference was observed among the 50, 100, and 150 mg/L IBA treatments for YS.

In YS cuttings, POD activity did not differ among the 50, 100, and 150 mg/L IBA treatments. However, all IBA-treated groups exhibited significantly higher activity than the control. In contrast, both SS and LS cuttings reached their maximum POD activity at 100 mg/L IBA.

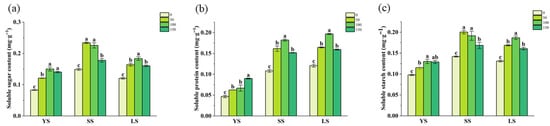

3.3.3. Organic Compound Content in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’

Organic compound content analysis of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings indicated that SS and LS exhibited elevated levels of soluble proteins (Figure 6b) and starch (Figure 6c) compared to YS, with the untreated groups showing the lowest values. The highest soluble sugar (Figure 6a) content was observed in YS with 100 and 150 mg/L IBA, in SS with 50 and 100 mg/L IBA, and in LS with 100 mg/L IBA. The optimal IBA concentrations for soluble protein (Figure 6b) content peaked at 150 mg/L in YS and at 100 mg/L in both SS and LS. Similarly, the soluble starch (Figure 6c) content reached its highest level at 100 and 150 mg/L IBA in YS, 50 and 100 mg/L IBA in SS, and at 100 mg/L in LS.

Figure 6.

Soluble sugar (a), soluble protein (b), and soluble starch (c) content in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) Cuttings after 120 days. Note: The above statistical data are the average of three replicates. Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

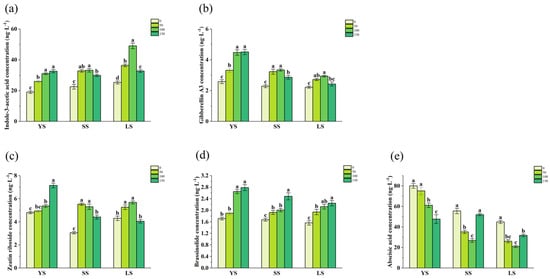

3.3.4. Endogenous Hormone Content in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’

Relative to the control, the application of IBA significantly increased the contents of Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA, Figure 7a) and Gibberellin A3 (GA3, Figure 7b) in YS, SS, and LS cuttings. Specifically, the IAA content peaked at 100 mg/L IBA in LS cuttings, showing a significant advantage over other treatments. The GA3 content reached its maximum at 100 and 150 mg/L IBA in YS cuttings, and at 50 and 100 mg/L IBA in both SS and LS cuttings. Similarly, the Zeatin riboside (ZR) content (Figure 7c) peaked at 150 mg/L IBA in YS cuttings, and at 50 and 100 mg/L IBA in SS and LS cuttings. The Brassinolide (BR) content (Figure 7d) exhibited peaks at 100 and 150 mg/L IBA in YS and LS cuttings, while in SS cuttings, the peak was observed specifically at 150 mg/L IBA. In contrast, abscisic acid (ABA) content (Figure 7e) presented a distinct pattern. Its relatively highest levels were found at 0 and 50 mg/L IBA in YS cuttings, and at 0 and 150 mg/L IBA in both SS and LS cuttings.

Figure 7.

Indole-3-acetic acid (a), Gibberellin A3 (b), Zeatin riboside (c), Brassinolide (d), and Abscisic acid (e) concentration in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) Cuttings after 120 days. Note: The above statistical data are the average of three replicates. Different lowercase letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.4. Analysis of Variance and Comprehensive Membership Function Evaluation

3.4.1. Variance Analysis of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’

Variance analysis was conducted on 26 indices. The results (Table S1) revealed that the number of adventitious roots, survival rate, rooting percentage, rooting index, total root length, root projected area, total root surface area, total root volume, and root fresh weight were all significantly positively affected by both the cutting type and exogenous hormone concentration. In contrast, adventitious root length, PPO activity, IAA concentration, and BR concentration showed significant positive correlation with exogenous hormone levels. Meanwhile, average root diameter, plant height, branch length, soluble sugar content, soluble starch content, and soluble protein content were significantly positively associated with cutting types. Conversely, ABA concentration exhibited a significantly negative association.

3.4.2. Principal Component Analysis and Comprehensive Evaluation of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on 26 indices related to rooting, growth, and physiological characteristics of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ cuttings (Table 5). The first five principal components, which together accounted for 94.51% of the total variance, were selected for comprehensive membership function evaluation. The results indicated that the LS-100 treatment scored the highest, followed by SS-100. In contrast, the YS-0 and YS-50 showed the lowest scores.

Table 5.

Comprehensive evaluation of rooting using membership function for B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) Cuttings under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L).

4. Discussion

4.1. Cutting Type as a Key Intrinsic Factor Affecting the Rooting and Growth of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’

The regenerative and rooting potential of cuttings is positively influenced by the accumulation of organic compounds and endogenous hormones [24]. Generally, in highly lignified cuttings, metabolic processes are commonly weakened, and rooting capacity is significantly reduced by the combined effects of accumulating inhibitory compounds (such as tannins and phenolics) and declining auxin levels [25].

In our study, lignified (LS) and semi-lignified (SS) shoot cuttings exhibited superior rooting performance, showing higher rooting rates, increased root activity, and more developed root systems than young semi-lignified shoot cuttings (YS). Variance analysis confirmed that cutting type significantly influenced the rooting rate and root growth, consistent with previous reports of a positive correlation between cutting diameter and rooting rate [26]. Meanwhile, plant height and branch length were significantly correlated with cutting type. Specifically, LS cuttings yielded the tallest plants with the most branches, outperforming both SS and YS. Branch length was also greater in both LS and SS cuttings compared to YS. These findings demonstrate that cutting age and diameter collectively enhance plant growth, as older and thicker cuttings provide more nutrient reserves that support superior branch development [27,28].

Furthermore, adventitious root formation in plant cuttings is an energy-intensive process that demands substantial material resources. Carbon and nitrogen compounds are essential substrates during rooting, providing critical nutritional support for callus formation and subsequent root development [29,30]. In this study, soluble sugars, proteins, and starch showed significant correlations with cutting type, with SS and LS cuttings containing higher levels of these nutrients than YS cuttings. Soluble starch serves as a hydrolyzable source of soluble sugars [31], while the sugars themselves provide both energy and signaling functions that stimulate adventitious rooting and growth [32]. Soluble proteins act as structural components of protoplasm while also functioning as enzymatic regulators involved in morphogenesis, cell growth, and differentiation [33]. Meanwhile, some studies suggest that carbohydrate content may not directly control rooting rate but rather regulates root growth and development [34,35].

4.2. Exogenous IBA Significantly Enhances the Rooting and Growth of Cuttings by Regulating Enzymatic Activity and Endogenous Hormone Homeostasis

Exogenous IBA plays a key regulator of adventitious rooting by converting to IAA, thereby enhancing auxin biosynthesis and transport [36]. This regulation involves synergistic actions of peroxisome-derived metabolites and jasmonates, along with downstream auxin signaling components [36].

Our study demonstrated that most IBA-treated cuttings exhibited markedly higher rooting rates, enhanced root activity, and superior root development compared to the control group. These findings align with practical observations that IBA application significantly shortens the rooting period, increases root number, improves root architecture, and enhances root vitality relative to untreated controls [37,38].

Studies on tea cuttings have confirmed that optimal IBA concentrations promote basal cell division, stimulate root primordium differentiation, and enhance vascular development [19]. In our experiments, superior rooting was achieved with 100 mg/L IBA compared to 150 mg/L in both SS and LS cuttings, confirming the importance of precise concentration optimization to avoid both deficiency and supra-optimal inhibition.

Meanwhile, cuttings undergo post-excision stress from interrupted nutrient supply, making it vital to enhance their stress tolerance and accelerate root emergence. Antioxidant enzymes such as POD, SOD, and PPO play crucial roles in oxidative defense and root development.

The root formation phase was characterized by enhanced POD activity, improving stress resistance and adventitious rooting, along with markedly increased IAA content [29]. Moreover, SOD scavenges reactive oxygen species to alleviate oxidative stress, delay senescence, and promote rooting [39]. Furthermore, upregulated PPO activity promotes rooting by protecting cuttings and facilitating root formation [12].

Our studies demonstrated that exogenous IBA significantly enhanced the activity of antioxidant enzymes. However, only PPO activity was significantly correlated with IBA concentration, suggesting that rooting promotion by IBA occurred primarily through PPO upregulation. These findings were consistent with reports in tea tree propagation that IBA treatment also significantly increased PPO activity, which improved rooting efficiency [40,41]. These results confirm the crucial role of antioxidant enzymes in cuttings’ survival and root development.

Endogenous hormone balance also plays a central role in adventitious root formation. Although no significant correlation was observed between rooting-promoting hormone content and cutting type, significant correlations were found between IBA concentration and both IAA and BR levels. Both IAA and BR levels were increased by exogenous IBA application, indicating that rooting was primarily facilitated through IBA-mediated modulation of endogenous IAA and BR levels.

Adventitious root formation was primarily induced by IAA [42]. IAA initiates root formation by binding to cell surface receptors, triggering signaling pathways that activate genes responsible for cell division and differentiation [37]. This process leads to callus formation and establishes the cellular foundation for root primordium development [43]. Meanwhile, BR regulated the differentiation and division of root tip meristem cells. Low BR concentrations promoted rooting, while high concentrations produced inhibitory effects. A significant synergistic effect is observed between BRs and auxin during root development, potentially mediated through overlapping activities, shared target genes, or enhanced auxin transport [44].

4.3. LS-100 Treatment Showed Optimal Rooting in B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ Cuttings by Membership Function Analysis

The principal component analysis (PCA) was used to reduce a large number of variables to a smaller group of variables that explained performance; the performance cues were used for further comprehensive evaluation [45]. The weight of each indicator was objectively determined through this method, effectively minimizing the influence of overlapping information [46]. The method has been widely used for rooting evaluation in various plant species [45,47]. In this study, the first five principal components accounted for 94.06% were selected for comprehensive membership function evaluation. The LS-100 treatment group (lignified cuttings treated with 100 mg/L IBA) exhibited the highest membership function value, indicating its optimal overall rooting performance.

Most Bougainvillea cultivars are inherently hard-to-root, limiting the effectiveness of cutting propagation despite its wide use in ornamental species [48]. Studies observed that IBA concentrations of 6000, 100, and 2000 ppm significantly increased the rooting performance of stem cuttings of Bougainvillea ‘Mahara’, ‘Akola,’ and ‘Thimma’, respectively [48,49]. Interestingly, the hardwood cuttings of Bougainvillea produced the highest number and the longest roots compared to semi-hardwood and softwood cuttings [48,50]. Those conclusions are consistent with our findings. However, the relatively low rooting rate in this study was likely derived from high temperatures in the greenhouse, which could have adversely affected root formation [51,52].

In summary, our findings provide technical guidance for B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ propagation with substantial practical applications. A promising direction for future research would be the investigation of temperature effects on rooting efficiency.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the cutting propagation of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ from April to August is co-determined by cutting type and exogenous IBA concentration. The key parameters showed that adventitious root number, rooting rate, root system architecture (total length, projected area, volume), and root fresh weight differed significantly among cutting types and were further enhanced by IBA application relative to their respective controls. Plant growth (plant height, branch length) and the contents of soluble sugars, starch, and protein were predominantly determined by cutting type. In contrast, the activity of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) was significantly influenced only by IBA application. At the hormonal level, IBA treatment increased the endogenous levels of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and Brassinolide (BR), with cutting type concurrently influencing abscisic acid (ABA) content. According to the comprehensive membership function evaluation, the treatment of lignified shoots (LS) with 100 mg/L IBA (LS-100) resulted in optimal protocol, achieving a rooting rate of 63% and significantly improved root formation, plant growth, root activity, organic compound content (soluble sugars, starch, and protein), PPO activity, and the levels of IAA and BR. These findings provide theoretical support and technical guidance for the large-scale propagation of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121496/s1, Table S1: Variance analysis on rooting of B. spectabilis ‘Yunnan Purple’ under IBA treatment (0, 50, 100, 150 mg/L) in Young lignified (YS), semi-lignified (SS), and lignified (LS) Cuttings after 120 days.

Author Contributions

L.H.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition; D.H.: supervision and writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Development Program of Jingzhou, Hubei Province, A Key Technology for the Rapid Propagation of Cold-Tolerant Bougainvillea Cultivars, via grant numbers (2021CC28-24).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are greatly indebted to the Science and Technology Development Program of Jingzhou, Hubei Province, for their financial support and the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture college, University of Yangtze, for their technical support and help with experiment preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LS | Lignified shoots |

| SS | Semi-lignified shoots |

| YS | Young lignified shoots |

| ZR | Zeatin riboside |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| BR | Brassinolide |

| GA3 | Gibberellic acid |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| ROS | Scavenging reactive oxygen species |

| PPO | Polyphenol oxidase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Bortolotti, M.; Bolognesi, A.; Polito, L. Bouganin, an Attractive Weapon for Immunotoxins. Toxins 2018, 10, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xu, J.; Wu, K.; Gong, C.; Jie, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, J. An Efficient Method for the Propagation of Bougainvillea glabra ‘New River’ (Nyctaginaceae) from in Vitro Stem Segments. Forests 2024, 15, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Sheng, Q.; Zhu, Z. Complete Chloroplast Genomes and Phylogenetic Relationships of Bougainvillea spectabilis and Bougainvillea glabra (Nyctaginaceae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Zamir, R.; Shah, S.T.; Wali, S. In Vitro Surface Sterilization of the Shoot Tips of Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd. Pure Appl. Biol. 2016, 5, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.L.; Hu, D. Effect of Spraying Cold Resistance Agents on Cold Resistance of Bougainvillea glabra. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2020, 32, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, L.R.; Hua, Z.Z.; Qin, Z.X.; Xian, L.L.; Hua, S.M.; Nan, X.Z. Effects of Remaining Leaf Combining with IBA on Rooting, Physiological and Biochemical Indicators of Leaves from Bougainvillea spectabilis Cuttings. Sci. Technol. 2010, 23, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Guo, W.; Xiao, W.; Liu, J.; Jia, Z.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, Z.; Chang, E. Effects of Different Donor Ages on the Growth of Cutting Seedlings Propagated from Ancient Platycladus orientalis. Plants 2023, 12, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eed, A.M.; Albana’a, B.; Almaqtari, S. The Effect of Growing Media and Stem Cutting Type on Rooting and Growth of Bougainvillea Spectabilis Plants. Univ. Aden J. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2015, 19, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dob, A.; Lakehal, A.; Novak, O.; Bellini, C. Jasmonate Inhibits Adventitious Root Initiation through Repression of CKX1 and Activation of RAP2.6L Transcription Factor in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 7107–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, W.; Zhao, C.; Guo, X. Overcoming Challenges in Plant Biomechanics: Methodological Innovations and Technological Integration. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2415606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannasaksri, W.; Temviriyanukul, P.; Aursalung, A.; Sahasakul, Y.; Thangsiri, S.; Inthachat, W.; On-Nom, N.; Chupeerach, C.; Pruesapan, K.; Charoenkiatkul, S.; et al. Influence of Plant Origins and Seasonal Variations on Nutritive Values, Phenolics and Antioxidant Activities of Adenia Viridiflora Craib., an Endangered Species from Thailand. Foods 2021, 10, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, R.; Shen, H.; Yang, L. Effect of Exogenous Plant Growth Regulators and Rejuvenation Measures on the Endogenous Hormone and Enzyme Activity Responses of Acer Mono Maxim in Cuttage Rooting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somkuwar, R.G.; Bondage, D.D.; Surange, M.S.; Ramteke, S.D. Rooting Behaviour, Polyphenol Oxidase Activity, and Biochemical Changes in Grape Rootstocks at Different Growth Stages. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2011, 35, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alscher, R.G.; Erturk, N.; Heath, L.S. Role of Superoxide Dismutases (SODs) in Controlling Oxidative Stress in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, R.; You, L.; Zhong, G. Characterization of Cu-Tolerant Bacteria and Definition of Their Role in Promotion of Growth, Cu Accumulation and Reduction of Cu Toxicity in Triticum aestivum L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 94, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Yu, J.; Liao, W.; Xie, J.; Yu, J.; Lv, J.; Xiao, X.; Hu, L.; Wu, Y. Proteomic Investigation of S-Nitrosylated Proteins During NO-Induced Adventitious Rooting of Cucumber. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, M.; Reuveni, O.; Goldschmidt, E.E. The Physiological Basis for Loss of Root ability with Age in Avocado Seedlings. Tree Physiol. 1987, 3, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, N.; Zhang, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, L.; Li, J. Formulation of Substrates with Agricultural and Forestry Wastes for Camellia Oleifera Abel Seedling Cultivation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damodaran, S.; Strader, L.C. Protocol for Determining Regulators of Competence in Regeneration of Adventitious Roots Using Hypocotyl Wounding Approach in Arabidopsis. STAR Protoc. 2025, 6, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.K.; Rawat, J.M.S.; Tomar, Y.K. Influence of IBA on Rooting Potential of Torch Glory Bougainvillea. J. Hortic. Sci. Ornam. Plants 2011, 3, 162–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Xu, C.; Lu, B.; Zhu, X.; Luo, X.; He, B.; Elidio, C.; Liu, Z.; Ding, Y.; Yang, J.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of Rice Qualities under Different Nitrogen Levels in South China. Foods 2023, 12, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xuan, Y.; He, N. Evaluation of Cutting Growth and Rooting Potentials of Different Mulberry Varieties. J. Southwest Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 47, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Luo, C. Plant Physiology Experiment Tutorial; Southwest China Normal University Press: Chongqing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yin, B.; Zhou, S.; Xu, J. Crop Load Influences Growth and Hormone Changes in the Roots of “Red Fuji” Apple. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Battista, F.; Maccario, D.; Beruto, M.; Grauso, L.; Lanzotti, V.; Curir, P.; Monroy, F. Metabolic Changes Associated to the Unblocking of Adventitious Root Formation in Aged, Rooting-Recalcitrant Cuttings of Eucalyptus gunnii Hook. f. (Myrtaceae). Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 89, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ye, X.; Shui, J. Some Soybean Cultivars Have Ability to Induce Germination of Sunflower Broomrape. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannoud, F.; Bellini, C. Adventitious Rooting in Populus Species: Update and Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 668837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otiende, M.A.; Nyabundi, J.O.; Ngamau, K.; Opala, P. Effects of Cutting Position of Rose Rootstock Cultivars on Rooting and Its Relationship with Mineral Nutrient Content and Endogenous Carbohydrates. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zeng, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, S. Cutting propagation of Periploca forrestii and Dynamic Analyses of Physiological and Biochemical Characteristitics Related to Adventitious Roots Formation. Zhong Yao Cai 2011, 34, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Opdahl, L.J.; Lewis, R.W.; Kalcsits, L.A.; Sullivan, T.S.; Sanguinet, K.A. Plant Uptake of Lactate-Bound Metals: A Sustainable Alternative to Metal Chlorides. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Qin, L.; Li, F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, R.; Yu, X.; Niu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Physiological and Transcriptomic Analysis Provides Insights into Low Nitrogen Stress in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monder, M.J.; Pacholczak, A. Rhizogenesis and Concentration of Carbohydrates in Cuttings Harvested at Different Phenological Stages of Once-Blooming Rose Shrubs and Treated with Rooting Stimulants. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2020, 36, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jones, C.S.; Parsons, A.J.; Xue, H.; Rasmussen, S. Does Gibberellin Biosynthesis Play a Critical Role in the Growth of Lolium perenne? Evidence from a Transcriptional Analysis of Gibberellin and Carbohydrate Metabolic Genes after Defoliation. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, M.; Muhammad, S.; Jin, W.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Munir, R.; et al. Modulating Root System Architecture: Cross-Talk between Auxin and Phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1343928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Chen, X.-L.; Hao, Y.-P.; Jiang, C.-W.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.-S.; Wei, Q.; Chen, S.-J.; Yu, X.-S.; Cheng, F.; et al. Optimization of Factors Affecting the Rooting of Pine Wilt Disease Resistant Masson Pine (Pinus massoniana) Stem Cuttings. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, T.A.; Strader, L.C. Auxin Activity: Past, Present, and Future. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnussat, G.C.; Lanteri, M.L.; Lombardo, M.C.; Lamattina, L. Nitric Oxide Mediates the Indole Acetic Acid Induction Activation of a Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascade Involved in Adventitious Root Development. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, L.; Wyse, D. Optimizing IBA Concentration and Stem and Segment Size for Rooting of Hybrid Hazelnuts from Hardwood Stem Cuttings. J. Environ. Hortic. 2019, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.; García, G.; Parola, R.; Maddela, N.R.; Pérez-Almeida, I.; Garcés-Fiallos, F.R. Root-Shoot Ratio and SOD Activity Are Associated with the Sensitivity of Common Bean Seedlings to NaCl Salinization. Rhizosphere 2024, 29, 100848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, G.R. Effect of Auxins on Adventitious Root Development from Single Node Cuttings of Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze and Associated Biochemical Changes. Plant Growth Regul. 2006, 48, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.Y. Advances on Internal Influence Factors of Adventitious Rooting of Forest Trees. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2017, 18, 1168–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, J.; Ni, R.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Ma, M.; Bi, H. Effects of Different Growth Regulators on the Rooting of Catalpa Bignonioides Softwood Cuttings. Life 2022, 12, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, T.; Dong, Z.; Zheng, X.; Song, S.; Jiao, J.; Wang, M.; Song, C. Auxin and Its Interaction with Ethylene Control Adventitious Root Formation and Development in Apple Rootstock. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 574881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praet, S.; Rizza, A.; Tang, B.; Xie, C.; Jones, A.; Inzé, D.; Vanholme, B.; Depuydt, S. Coumarin Promotes Hypocotyl Elongation in Light-Grown Arabidopsis thaliana Seedlings by Enhancing Brassinosteroid Signalling in an Auxin-Dependent Manner. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 3290–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, N.; Richter, C.; Franklyn-Miller, A.; Moran, K. Principal Component Analysis of the Biomechanical Factors Associated with Performance During Cutting. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Su, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Guan, Z.; Fang, W.; Chen, F.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, F. Evaluation of Volatile Compounds in Tea Chrysanthemum Cultivars and Elite Hybrids. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 320, 112218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsoleimani, A.; Zinati, Z.; Abbasi, S. New Insights into the Identification of Biochemical Traits Linked to Rooting Percentage in Fig (Ficus carica L.) Cuttings. J. Berry Res. 2024, 14, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K. A Review: Multiplication of Bougainvillea species through Cutting. ResearchGate 2018, 6, 1961–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, L.M. Effect of Certain Plant Growth Regulating Substances on the Rooting of Bougainvillea spectabilis L. Stem Cuttings. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1967, 36, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Zangeneh, M. Root Dynamics in Bougainvillea glabra Choisy Cuttings: Analyzing the Influence of Auxin Type, Concentration, and Cutting Type Over Time in Two Varieties. J. Ornam. Plants 2025, 15, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, M.P.; Conesa, C.M.; Lozano-Enguita, A.; Baca-González, V.; Simancas, B.; Navarro-Neila, S.; Sánchez-Bermúdez, M.; Salas-González, I.; Caro, E.; Castrillo, G.; et al. Temperature Changes in the Root Ecosystem Affect Plant Functionality. Plant Comm. 2023, 4, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taduri, S.; Bheemanahalli, R.; Wijewardana, C.; Lone, A.A.; Meyers, S.L.; Shankle, M.; Gao, W.; Reddy, K.R. Sweetpotato Cultivars Responses to Interactive Effects of Warming, Drought, and Elevated Carbon Dioxide. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1080125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).