Abstract

This review explores the synergistic integration of edible coatings and non-thermal preservation technologies as a multifaceted approach to maintaining food quality, safety, and sustainability. Edible coatings—composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, or composite biopolymers—serve as biodegradable barriers that control moisture, gas, and solute transfer while acting as carriers for bioactive compounds such as antimicrobials and antioxidants. Meanwhile, non-thermal techniques, including high-pressure processing, cold plasma, ultrasound, photodynamic inactivation, modified atmosphere packaging, and irradiation, offer microbial inactivation and enzymatic control without compromising nutritional and sensory attributes. When combined, these technologies exhibit complementary effects: coatings enhance the stability of bioactives and protect surface quality, while non-thermal treatments boost antimicrobial efficacy and promote active compound penetration. The review highlights their comparative advantages over individual treatments—improved microbial inhibition, nutrient retention, and sensory quality. It further discusses the possible mechanisms through which edible coatings and selected hurdles induced microbial decontamination. Finally, the study identified major drawbacks and provided strategic recommendations to overcome these limitations, including optimizing coating formulations for specific food matrices, tailoring process parameters to minimize adverse physicochemical changes, and conducting pilot-scale validations to bridge the gap between laboratory success and industrial application.

1. Introduction

The growing demand for fresh, nutritious, and minimally processed foods has intensified the search for preservation methods that ensure safety and quality while minimizing nutrient degradation. Traditional thermal preservation techniques, though effective in microbial inactivation and shelf-life extension, often compromise the sensory and nutritional attributes of fruits and vegetables. Heat treatments can induce undesirable changes such as texture softening, color loss, and the degradation of thermolabile compounds like vitamins, polyphenols, and carotenoids [1,2]. This limitation is especially problematic for fruits and vegetables, where even moderate heat exposure accelerates texture breakdown, color loss, and depletion of bioactive compounds. These drawbacks underscore a critical need for preservation strategies capable of achieving microbial stability without undermining the very quality attributes that define consumer acceptance and market value.

Edible coatings have been proposed as one such strategy, offering a biodegradable, multifunctional barrier that can delay moisture loss, oxidation, and microbial contamination [3,4]. However, their standalone effectiveness remains inconsistent. Coating performance is highly sensitive to environmental factors such as humidity, temperature fluctuations, and mechanical stress, particularly across complex postharvest supply chains [5,6]. This vulnerability limits their ability to deliver sustained protection under real storage and distribution conditions.

In parallel, non-thermal preservation methods offer targeted microbial and enzymatic inactivation with minimal nutritional or sensory degradation [7]. Yet individually, these technologies seldom provide comprehensive control of deterioration pathways in highly perishable produce. This points to a broader unresolved problem: no single mild preservation method consistently meets the combined requirements of microbial safety, sensory quality retention, and shelf-life extension across diverse commodities.

Integrating edible coatings with non-thermal technologies has therefore gained attention as a promising hurdle-based strategy. Such combinations may enhance coating functionality, create synergistic antimicrobial effects, and improve the resilience of preservation systems to environmental variability. However, existing research remains fragmented. Studies exploring pulsed light [8], ultrasound [9], modified atmosphere packaging [10], photodynamic inactivation [11], ultraviolet [12], and gamma irradiation [13] suggest potential, but lack comprehensive, mechanistic synthesis. Current reviews address edible coatings alone [14,15,16,17] or in broad combination with various preservation strategies [18,19,20] without explicitly examining how specific non-thermal treatments influence combined preservation outcomes. Even the most closely related review by Beikzadeh et al. [21] focused on thermal and non-thermal treatments as modifiers of coatings but did not evaluate how these combined strategies directly impact microbial safety, sensory quality, and postharvest loss reduction in fresh produce.

To address this gap, the present review critically synthesizes current evidence on the combined application of edible coatings and non-thermal preservation technologies for fresh produce. Specifically, it accomplished the following:

- Examines how non-thermal treatments affect the adhesion, integrity, and functional performance of edible coatings when applied to fresh produce;

- Evaluates the synergistic (or antagonistic) effects of combined approaches on microbial stability, quality retention, and shelf-life extension;

- Identifies technological, mechanistic, and practical limitations that hinder their broader commercial adoption.

By consolidating this dispersed body of research, the review aims to clarify the mechanistic underpinnings, preservation outcomes, and implementation challenges of this integrated strategy, ultimately guiding future research and supporting the development of more robust, sustainable postharvest preservation systems.

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

This review followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [22] to ensure a systematic, transparent, and reproducible approach to study selection. A comprehensive search was conducted in the electronic databases PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed, accessed on 15 June 2025), Google Scholar (scholar.google.cn, accessed on 15 June 2025), Springer (https://link.springer.com, accessed on 17 September 2025), and ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com, accessed on 21 September 2025) for studies published up to September 2025.

The following combination of keywords and Boolean operators were used for precision—(“edible coating” OR “biopolymer coating”) AND (“non-thermal technology” OR “cold plasma” OR “ultrasound” OR “high hydrostatic pressure”) AND (“fruits” OR “vegetables”), (“edible coating” OR “chitosan coating”) AND (“UV-C” OR “pulsed electric field”) AND (“postharvest quality” OR “shelf life”), (“combined preservation” OR “synergistic effect”) AND (“non-thermal processing”) AND (“horticultural produce” OR “fresh-cut fruits”), (“edible coating” OR “edible films”) AND (“MAP) AND (“fruits” OR “vegetables”). All related articles were extracted, categorized, and summarized.

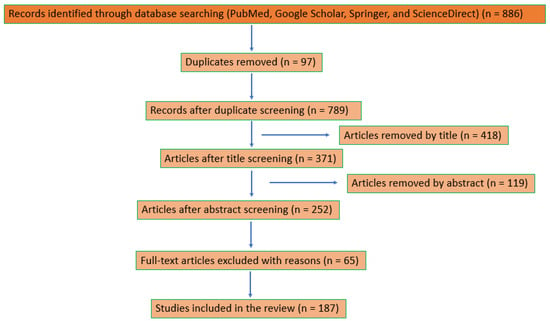

The search and selection processes are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). A total of 886 articles were initially identified across all databases. After removing duplicates (97), 789 articles were screened by title and abstract, of which 699 were excluded for irrelevance. Finally, 187 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into this review.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram (adapted from PRISMA (2020) from Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, and Brennan [22]).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

- Focused on the application or synergistic use of edible coatings and non-thermal technologies in food preservation.

- Reported quantitative or qualitative outcomes related to food quality, shelf-life, microbial stability, or physicochemical properties.

- Were peer-reviewed journal articles or book chapters written in English.

Studies were excluded if they fulfilled the following:

- Investigated only thermal preservation methods without a non-thermal counterpart.

- Were conference abstracts, patents, or non-peer-reviewed materials.

- Lacked sufficient methodological or experimental detail for evaluation.

- Focused on non-horticultural products.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

All retrieved records were imported into ENDNOTE X8 to identify and remove duplicates. Screening was performed in two stages: Title and abstract screening to exclude irrelevant studies; full-text assessment to confirm eligibility based on inclusion criteria. For each included study, the following data were extracted and tabulated:

- Type of edible coating or biopolymer material used.

- Non-thermal technology applied (e.g., ultrasound, plasma, irradiation).

- Horticultural product type, hurdle approach, and target foodborne threat.

2.4. Data Analysis and Synthesis

The extracted data were analyzed using a qualitative synthesis approach. First, all eligible articles were categorized based on the type of edible coating, non-thermal technology, and food matrix investigated. A thematic grouping strategy was then applied to categorize the findings into emerging themes such as (i) quality preservation mechanisms, (ii) microbial inhibition, (iii) physicochemical stability, and (iv) synergistic effects between coating materials and non-thermal techniques.

A qualitative content analysis was performed to evaluate consistencies and differences in experimental outcomes. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs, food products, and response variables, no statistical pooling was performed. Instead, evidence was synthesized narratively to provide a coherent and integrative understanding of how edible coatings and non-thermal technologies interact to improve food quality and preservation sustainability.

3. Functionality of Edible Coatings

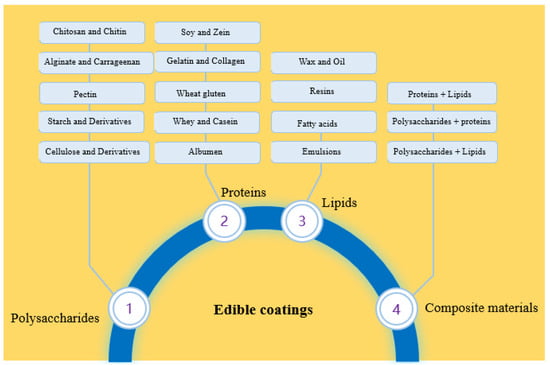

Figure 2 summarizes the major classes of edible coatings that have been applied in the food packaging industry. These coatings serve multiple roles that contribute to preservation; they are multifunctional systems rather than simple coatings.

Figure 2.

Major groups of edible coatings.

Barrier function: Edible coatings serve as multifunctional barriers that regulate the exchange of moisture, gases, solutes, and light between food and the surrounding environment, thereby slowing deterioration and extending shelf life [23]. Their moisture barrier function minimizes dehydration and weight loss, especially when hydrophobic lipids or composite structures are used, while gas barrier properties limit oxygen access and modulate carbon dioxide efflux, creating a localized modified atmosphere that delays respiration and enzymatic browning in fresh produce [24].

Carrier and controlled-release systems: Edible coatings function as effective carrier and controlled-release systems for bioactive compounds such as antimicrobials, antioxidants, enzymes, and nutraceuticals, enabling sustained protection and quality enhancement of foods [25]. By incorporating these bioactives into polymer matrices, coatings allow gradual diffusion or triggered release in response to environmental factors like humidity, temperature, or pH. Hydrophilic polymers often facilitate diffusion-controlled release, while lipid-rich or crosslinked matrices slow migration and prolong activity. This controlled delivery maintains effective concentrations of bioactives at the food surface, enhancing microbial inhibition, oxidative stability, and overall shelf life without altering sensory attributes.

Mechanical and surface protection properties: Edible coatings contribute to mechanical and surface protection properties by forming protective layers that maintain the structural integrity, texture, and appearance of food products during storage and handling [26]. Their mechanical strength and flexibility depend on polymer composition, plasticizer content, and crosslinking, which together prevent cracking, peeling, or brittleness. By reducing moisture loss and oxidative damage, coatings help preserve firmness and elasticity in fruits, vegetables, and meat products, while also minimizing surface roughness or shrinkage. Additionally, coatings can enhance visual appeal by imparting gloss and smoothness, improve adhesion of added bioactive layers, and maintain desirable mouthfeel in ready-to-eat foods [27].

Together, these functionalities position edible coatings as highly compatible with non-thermal preservation technologies. By providing barrier protection, controlled delivery of bioactives, and mechanical stability, coatings create a supportive microenvironment that enhances the efficacy of non-thermal treatments, allowing milder processing conditions, improving microbial and oxidative control, and ultimately enabling a synergistic approach to extending food quality and shelf life in a sustainable manner.

4. Non-Thermal Technologies in Food Preservation and Their Potential Combinations with Edible Coatings

4.1. High-Pressure Processing (HPP)

4.1.1. Theory

High-pressure processing (HPP), utilized as a non-thermal method, is being increasingly adopted as an alternative to thermal techniques to preserve the natural qualities of fresh food products [28]. HPP has garnered increased recognition as a commercially viable non-thermal processing technique within the industry, owing to its manifold advantages including microbial inactivation, extended shelf life of treated products, preservation of sensory attributes, and retention of nutritional value. The process involves vacuum-sealing foods and then loading into a pressure vessel holding pressure-transmitting fluid [29]. Both the pressure vessel and its contents are sealed off by end caps. A pump and intensifier work together to compress the pressure-transmitting fluid, bringing the process pressure up to the required level. The principal advantage of treating food items to high-pressure processing is in its ability to impede the growth of predominant spoilage bacteria and/or the activity of enzymes. When pressure levels reach a certain threshold, it is possible to see phase transitions and alterations in the fluidity of microbial cell membranes. These changes can cause the membranes to rupture and lead to the denaturation of membrane proteins, ultimately ending in the death of the cells [30]. That said, HPP also entails notable drawbacks. One of the primary limitations associated with high-pressure processing (HPP) is the inadequate inactivation of pressure-resistant strains of foodborne pathogens, including Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria spp., Salmonella spp., or Staphylococcus spp. [31,32,33,34]. These pathogens exhibit a certain level of resistance to pressure, rendering them unaffected by elevated pressure levels or extended holding durations. In a study on cheeses by Evert-Arriagada et al. (2018) [32], the authors observed a reduction in L. monocytogenes count by approximately 5–6 log CFU/g following treatment at 500 MPa; however, at a lower treatment (300 MPa), the resulting reduction amounted to only 0.7 log CFU/g. In one study, L. monocytogenes survived even after treatments at 300, 400, and 500 MPa, with reductions ranging from very little (0 log) up to several log cycles depending on strain [35]. There are also reports of regeneration of damaged cells during storage: e.g., cells treated at 600 MPa for 3 min recovered and grew by ~1 log CFU/g after 42 days [36]. It has also been observed that high-pressure treatment can cause moisture to be expelled from certain foods, potentially leading to undesirable alterations in sensory and physicochemical attributes as a consequence of protein denaturation [37]. It is therefore beneficial to use HPP with a complementary processing technology to cope with the limiting factors and enhance food quality and safety.

4.1.2. Combination with Edible Coating

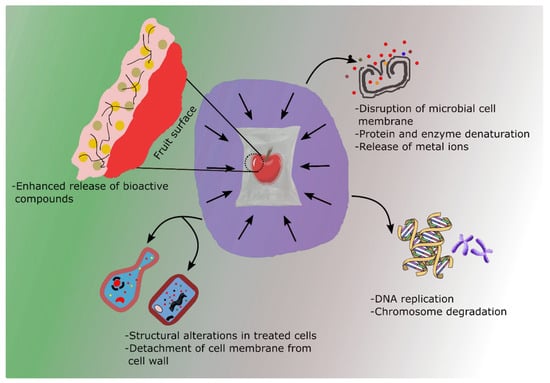

The utilization of edible coatings has been shown to augment the efficacy of HPP by introducing an extra protective layer that acts as a barrier against microbial contamination and mitigates moisture loss throughout the procedure. When HPP is combined with edible coatings, the benefits of both techniques can be synergistically enhanced. The pressure applied during HPP can help improve the penetration and adhesion of the edible coatings into the food surface, making the protective layer more effective. The existing literature on the topic suggests positive outcomes in terms of decontaminating foods and extending shelf life. Figure 3 depicts some of the advantages resulting from the synergistic application of edible coatings and HPP for decontaminating food spoilage microbial organisms. However, to the best of our knowledge, little research has been undertaken in this area.

Figure 3.

Synergistic application of food-grade coatings and HPP for deactivating food spoiling microbes.

A recent study by Bambace et al. [38] demonstrates a synergistic effect between HPP and an edible coating, resulting in enhanced microbial safety while preserving the structural and visual quality of apple cubes. In their study, the authors found that using HPP in conjunction with an edible coating resulted in a significant drop in several microbial populations, including Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) and E. coli. Importantly, this treatment did not have any adverse effects on the firmness and color of apple (Malus domestica) cubes. The mechanisms underlying these results can be understood from both microbial and tissue physiology perspectives. HPP exerts its antimicrobial effects primarily through the disruption of microbial cellular structures and functions under isostatic pressure (typically 400–600 MPa). This leads to leakage of intracellular contents, loss of osmotic balance, and ultimately cell death [36]. HPP can also disrupt ribosomal subunits and cause DNA conformational changes, further inhibiting microbial replication and repair [39]. The coating on the other hand acts as a semi-permeable barrier that limits oxygen diffusion and moisture loss, creating conditions unfavorable for microbial regrowth post-HPP. This decrease in firmness can be attributed to HPP bringing about tissue structure collapse by releasing gas from pores under higher pressure, resulting in tissue weakening [40]. Extrapolating from this, applying edible films to samples before HPP can result in the coating filling some pores, keeping the original textural integrity [38]. The result contradicts the findings of a previous study conducted by Donsì et al. [41], which showed that the application of high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) treatment in isolation led to a significant 50% increase in the firmness of green beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) compared to control samples. Again, the addition of a bioactive coating to the HHP treatment did not alter the observed impact that was attributed only to the HHP treatment. In contrast, neither the firmness nor coating integrity of samples treated with pulsed light treatment and bioactive coating were compromised. However, it is understood that the discrepancies in texture could be attributable to the makeup of the individual samples. But on the flip side, the combined treatment of HHP and coating formulation was characterized by a strong antimicrobial synergistic effect against Listeria innocua (L. innocua) in the early days of storage. This was evident from a substantial reduction of 4 Log CFU/g in the initial microbial load. On the other hand, samples treated with PL treatment and bioactive coating did not demonstrate any synergistic or additive antimicrobial effect against L. innocua throughout the storage period.

4.2. Ultrasound

4.2.1. Theory

Power ultrasound utilizes high-intensity, low-frequency sound waves, typically in the range of 20–100 kHz, to induce potent physical effects in liquid and solid media. The primary mechanism underpinning its efficacy is acoustic cavitation [42].

When ultrasound waves propagate through a liquid medium (such as a coating solution), they create alternating cycles of high pressure (compression) and low pressure (rarefaction). During the low-pressure rarefaction phase, the local pressure can drop below the liquid’s vapor pressure, causing the formation of millions of microscopic vapor-filled bubbles or “cavities” [43]. These bubbles oscillate and grow over several acoustic cycles until they reach a critical, unstable size. During a subsequent high-pressure compression phase, these bubbles collapse violently. At the point of collapse, transient “hot spots” are created with temperatures reaching up to 5500 K and pressures as high as 50 MPa. The violent collapse of the bubbles generates powerful shockwaves that propagate through the liquid and creates intense hydrodynamic shear forces in the immediate vicinity [42]. When cavitation occurs near a solid surface, such as a fruit peel, the bubble collapse becomes asymmetric. This asymmetry focuses the energy of the implosion into a high-velocity (up to 100 m/s) micro-jet of liquid that is propelled directly at the surface [44]. This phenomenon also induces intense, localized stirring and fluid circulation known as microstreaming, which dramatically enhances mass transfer at the solid–liquid interface [45].

4.2.2. Combination with Edible Coatings

Recent research provides compelling evidence of the synergistic benefits of combining ultrasound with edible coatings for a variety of fruits and vegetables. These studies demonstrate tangible improvements in quality preservation and shelf-life extension. In a study on Kinnow citrus, a corn starch-based edible coating was enriched with orange peel essential oil and prepared using ultrasonication. The application of ultrasound during the formulation stage dramatically reduced the average particle size of the coating solution from 2495 nm in the control to 298.8 nm. This resulted in a more stable and homogenous solution with enhanced antimicrobial activity. When applied to the fruit, the ultrasonicated coating was significantly more effective at retarding weight loss, maintaining firmness and titratable acidity, and preserving higher levels of phenolic and flavonoid content over the storage period compared to the non-sonicated coating [46]. The preservation of delicate fruits like strawberries has also benefited from this integrated approach. One study utilized power ultrasound to modify the rheological properties of citrus pectin gels. These sonicated gels, when used as an edible coating on fresh strawberries, demonstrated improved performance in maintaining quality attributes such as moisture retention, acidity, and color over a 5-day storage period [47]. Another innovative study developed a composite film of sodium alginate, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), and apple polyphenols. Ultrasound was used to assist in the deposition and ensure uniform dispersion of the AgNPs within the film matrix. This advanced coating successfully extended the shelf life of strawberries to approximately 8 days at 4 °C, effectively maintaining their storage quality [48]. There are, however, some studies which have raised issues with the incorporation of AgNPs in edible coatings. They contend that AgNP-containing films raise real migration and safety concerns (mainly because silver can be released as ions and, under some conditions, nanoparticles can (re)form and/or migrate into food). Regulators treat these uses on a case-by-case basis: EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes and Processing Aids et al. [49] found no consumer safety concern for a specific use scenario (AgNP additive ≤ 0.025% w/w in certain non-swelling polymers) because migration was low (mostly ionic silver, ≤~6 µg/kg food) and exposure would be below the acceptable daily intake. The US FDA requires case-by-case premarket assessment and has published guidance and research showing food components can change silver speciation and increase exposure [50]. Within this broader context of ensuring safe antimicrobial interventions, recent work on fresh-cut kiwifruit demonstrates that a two-step process, an initial decontamination with ultrasound and sodium hypochlorite followed by application of a chitosan (CHS) coating, can provide highly effective microbial control. The combination of the ultrasound pre-treatment and the subsequent coating significantly reduced mass loss, lowered the respiration rate, inhibited microbial growth, and maintained superior sensory quality for up to 10 days under refrigerated storage [51]. While fewer studies have focused on the direct ultrasound-assisted application of coatings to whole apples, related research provides valuable insights. It has been demonstrated that ultrasound treatment creates microchannels in apple tissue, which can enhance coating adhesion [52]. In a practical application for fresh-cut apples, an ultrasonic bath was used to prepare and degas a sodium alginate coating solution enriched with Stevia extract. The resulting coating was more effective at inhibiting polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity and reducing enzymatic browning during storage [53].

4.3. Irradiation (Non-Ionizing and Ionizing Radiation) Techniques

4.3.1. Theory

Irradiation sterilization is a method of cold sterilization utilizing gamma rays, X-rays, and electron beams generated from radiation sources. These forms of radiation exert direct and indirect effects on biomolecules, deactivate enzymes, eliminate microorganisms, and extend the shelf life of food [54]. The primary objective of employing this technique is to eradicate microorganisms, such as spoilage bacteria, yeasts, molds, and viruses, thereby impeding their ability to reproduce. Additionally, it serves to hinder the functionality of degradative enzymes responsible for inducing food spoilage [55,56]. Non-ionizing radiation lack sufficient energy to induce ionization and are therefore regarded as safe for food processing and preservation when used in accordance with established rules and regulations. By contrast, ionizing radiation possesses enough energy to loosen firmly bonded electrons in atoms or molecules, resulting in the creation of charged particles known as ions. This form of radiation can have both positive and negative effects [57]. There are three distinct categories of ionizing radiation that have the potential to be utilized in the process of food irradiation. These include gamma rays emitted by cesium 137 (137Cs) or cobalt 60 (60Co), X-rays that originate from processes outside the nucleus, functioning at or below an energy level of 5 MeV; and electron beams produced by machine sources operating at or below an energy level of 10 MeV [58]. Park et al. [59] reported that the utilization of these types of radiation has the tendency to eliminate harmful microorganisms like E. coli, Listeria monocytogenes (L. Monocytogenes), and Salmonella Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium). Although ionization radiation has many positive effects, the doses needed to inactivate pathogenic bacteria in meat products result in changes to the meat’s sensory characteristics that consumers may find unappealing. Therefore, low-dose radiation in combination with other decontamination techniques would be necessary to aid in eliminating microbes without affecting sensorial quality [60]. Excellent reviews on the implementation of the various types of radiation on preservation of fruits and vegetables [55] and eliminating food allergens [61] have been documented. The following authors have conducted comprehensive evaluations covering a range of food products [62]. To keep our discussion focused on the goal of this study, we shall confine it to the utilization of diverse radiation modalities in combination with edible coatings for the purpose of safeguarding the overall quality and safety of fresh produce.

4.3.2. Combination with Edible Coating

Non-ionizing radiation encompasses a range of forms, including ultraviolet (UV), visible light, infrared, and radio waves. UV light is subdivided into three separate categories: UVA (315–400 nm), UVB (280–315 nm), and UVC (100–280 nm). Of these, UVC radiation is the most harmful to microorganisms [63]. The deleterious impact of UV radiation on microorganisms stems from its ability to induce the formation of pyrimidine dimers in DNA or RNA molecules, hence impeding metabolic processes and leading to cellular mortality [64,65]. A number of studies have demonstrated that combining UV irradiation with other preservation procedures is particularly successful in protecting the quality of food products. Edible coatings can be used in conjunction with UV irradiation to delay enzymatic deterioration and maintaining the quality of the food during storage. Although the interaction between UV radiation and edible coatings is not well understood, some authors have conducted a series of studies to evaluate the synergistic effects of the two processes in ensuring adequate preservation of perishable goods. For example, Lin et al. [66] investigated the efficacy of regulating enzymatic activities and delaying senescence in longan fruits through the combined application of chitosan or carrageenan coatings and UVC radiation. The authors demonstrated that applying UVC treatment prior to chitosan coating yielded superior preservation effects, characterized by significantly lower PPO activity, reduced respiration rate, and improved maintenance of cellular integrity with minimal structural damage. Mechanistically, UVC pre-treatment inactivates a portion of surface microflora, including bacteria and fungi, thereby suppressing microbial-induced decay and ethylene biosynthesis—both of which are closely associated with accelerated senescence. Subsequent chitosan application reinforces these benefits by forming a semipermeable, antimicrobial barrier that limits oxygen permeability, reduces moisture loss, and promotes wound healing of the fruit epidermis [67]. The combined effects of microbial suppression, moderated oxidative metabolism, and enhanced membrane stability collectively contribute to delayed senescence and extended postharvest shelf life of longan fruits. The concept of integrating other protective measures along with irradiation hurdles, including the use of edible coatings, to enhance the overall quality of food products has also been tested. Abdipour, Sadat Malekhossini, Hosseinifarahi, and Radi [12] treated sweet cherry fruits with chitosan edible coating and UVB + UVC lights. In spite of the fact that both UV lamps were effective in maintaining fruit quality, the total anthocyanin content and antioxidant capacity of sweet cherries treated with UVC were higher than those treated with UVB. The incorporation of chitosan, on the other hand, provided an additional layer of protection by strongly inhibiting and retarding weight loss, maintained fruit firmness, and delayed changes in quality attributes. In another study conducted by [68], it was observed that the utilization of UVC treatment in conjunction with alginate-pectin nanoparticles encapsulated with lemon essential oil nanocapsules yielded the best result in terms of prolonging the storage duration of fresh-cut cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Specifically, this treatment exhibited a substantial extension of up to 15 days in the shelf life of the cucumber samples.

Light-mediated inactivation of microbes based on PL systems is another non-thermal technology that has garnered considerable interest and is recognized for its potential to be extensively implemented in food processing. The wavelength distribution range for PL spans between 100 and 1100 Nm: UV (100–400 nm), visible light (400–700 nm), and infrared (700–1100 nm). Different studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of PL technology in inactivating microorganisms including bacteria, mold spores, and viruses [69,70,71]. The deleterious impact of the PL technology in leading to microbial cell death is related to its strong broad-spectrum UV radiation, which induces the formation of potentially fatal thymine dimers in bacterial DNA. These dimers can hinder DNA transcription and replication, ultimately resulting in cell death [72,73]. Additionally, they can cause a localized increase in temperature by absorbing UV and IR radiations, which in turn intensify the effects of UV radiation and disturb bacterial activity [74]. Others are the inherent features of microbial cells, such as the type of microbe, its growth phase, and inoculum size [19]. In food processing applications, the pulses of light employed often exhibit a frequency of 1 to 20 flashes per second, while maintaining an energy density within the approximate range of 0.01 to 50 J cm−2 at the surface [75]. Different studies have proposed the use of PL treatments for the decontamination of perishable produce [76,77,78]. However, the efficacy of PL treatment may be compromised if the appropriate treatment parameters are not achieved or if samples are exposed to abusive treatment conditions [8]. Furthermore, when there are excessively high cell densities or bacterial clustering, a shadowing effect can occur, obstructing light penetration and hindering bacterial inactivation [79]. Researchers have also observed lower reductions in the native microflora growing on spinach leaves subjected to pulsed light decontamination due to internalization of the microorganisms. These findings raise safety concerns about superficial decontamination by pulsed light. As a result, some researchers have proposed alternate approaches, including combining the technique with edible coatings as a reinforced hurdle to provide an extra layer of protection, preventing recontamination and maintaining the quality of the food during storage.

One such study was conducted by [80] who evaluated the effects of combining chlorophyllin (Chl)-CHS conjugate with illumination with visible light on L. monocytogenes, E. coli, and B. cinerea. The findings of the study indicate that photo-activated Chl-CHS conjugate suppressed the survival rate of L. monocytogenes by 7 log, E. coli and by 4.5 log in vitro. However, when the treatment was administered to strawberry fruits (Fragaria ananassa), it resulted in a considerable reduction in yeasts and micro-fungi on the surface of strawberries by 1.4 log compared to a 0.6 log reduction when sodium hypochlorite was applied. This reduction in microbial presence contributed to an extension of the shelf life of strawberries by 3 days. Importantly, this treatment did not have any adverse effects on the overall antioxidant activity, visual appearance, or color of the strawberries. The significant 1.4-log reduction in surface yeasts and molds—surpassing the 0.6-log reduction achieved by sodium hypochlorite—reduces metabolic spoilage activity, respiration rate, and ethylene accumulation during storage. This microbiological control contributes directly to the 3-day shelf-life extension observed in treated strawberries. Additionally, the residual chitosan film continues to suppress microbial re-colonization, maintaining a low contamination level throughout storage. Koh et al. [81] also combined alginate coating with repetitive pulsed light as a means to maintain the overall cell wall fractions of fresh-cut cantaloupes. The treatment gave rise to fresh-cut cantaloupes with enhanced cell turgidity and shape and with well-defined cell walls, thereby avoiding fluid loss and loss of firmness.

Another exciting technology that has the potential to alter the way we preserve food is the combination of edible coatings and ionizing radiation. Food irradiation includes exposing food to various radiation energy sources, such as electron beams and X-rays, in order to remove harmful microbes, insects, fungi, and pests [82]. The dose of 1 kGy has been approved for the treatment of fruits and vegetables to control insects and delay ripening. Nevertheless, this level is generally insufficient for the complete control of fungal pathogens, and higher doses—while more effective against microorganisms—can sometimes adversely affect the sensory and nutritional quality of fresh produce [83]. To address this quality issue, it is often advised to employ combination treatments. This is because such treatments have the ability to effectively reduce the required dosage of radiation and concentration of antimicrobial agents needed to eliminate pathogens by working together in a way that is greater than the sum of their individual effects [84]. The synergy between edible coatings and ionizing radiation can be tailored to the specific needs of the food product. Severino et al. [85] observed that, in green bean samples inoculated with E. coli and S. Typhimurium to a final load of 103 CFU/g, the combined treatment of 0.25 kGy irradiation and an enhanced chitosan coating incorporating a carvacrol nanoemulsion produced a greater antimicrobial effect than either treatment alone. Specifically, under storage at 4 °C for 13 days, the combined treatment resulted in a 1.68-log reduction in E. coli, whereas the coated-only samples showed a decrease of 0.53 log units, and the irradiated-only samples exhibited a 1.27-log reduction at the same 0.25 kGy dose. In the study, samples were packaged in 3 mil nylon/EVA copolymer bags and sealed either under air (78.1% N2, 20.9% O2, and 0.036% CO2) or under a modified atmosphere (60% O2, 30% CO2, and 10% N2), with microbial counts monitored on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 of refrigerated storage. Further studies have discovered additional synergistic effects resulting from the interaction of irradiation and active coating using a variety of formulations. For instance, Tawema et al. [86] provided evidence that the utilization of gamma irradiation at a dosage of 1 kGy, in conjunction with natural antimicrobial formulations comprising oregano or lemongrass essential oil, citrus extract, and lactic acid, resulted in a significant reduction in the population levels of L. monocytogenes and E. coli O157:H7 on cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L., Botrytis group). These reductions were observed to be below the limits of detection throughout the storage duration. Ben-Fadhel, Saltaji, Khlifi, Salmieri, Dang Vu, and Lacroix [84] observed that the application of active coatings in combination with irradiation at a dose of 0.4 kGy resulted in the E. coli count remaining below the limit of detection for the full duration of the storage period for broccoli florets.

4.4. Photodynamic Inactivation (PDI)

4.4.1. Theory

Photodynamic treatment is a therapeutic technique that does not generate any toxic chemicals, making it a safer alternative compared to other disinfection methods. Unlike UV or PL treatments, which rely on direct photochemical (DNA-damaging) and photophysical effects, photodynamic inactivation (PDI) operates through a fundamentally different mechanism: a photosensitizer (PS) absorbs visible light and transfers energy to oxygen, generating reactive oxygen species that oxidatively inactivate microorganisms [87]. This oxygen-dependent, indirect pathway provides greater selectivity and uses mild visible light, offering a novel, less destructive alternative for microbial control in foods. The application of different PSs in different food substrates has been reviewed, and factors influencing PDI and the mechanisms have been studied extensively [88,89,90,91]. Beyond the medical field, PDI has been used to improve food safety because it has shown potential in eliminating microorganisms such as bacteria, yeasts, molds, viruses, and parasites [92].

Similarly to other antimicrobial methods employed in the food industry, it is important to note that, in the majority of instances, the PDI alone is unable to completely eradicate pathogenic or spoilage microorganisms present in food. One notable reason is the hindrance posed by bacterial-generated biofilm matrices in PDI, as the extracellular matrix restricts the penetration of photosensitizers and the transfer of oxygen into deeper layers. Biofilm cells have been found to exhibit significantly higher resistance, ranging from 10 to 1000 times, compared to their planktonic counterparts. This increased resistance poses a significant challenge to hygienic treatments, as it enables spoilage bacteria and pathogens to withstand these treatments more effectively, threatening the food industry [93]. Chen et al. [94] noted that methicillin resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus are among a host of microorganisms that can survive PDI process. The microorganisms that survive the PDI process elicit a variety of adaptive responses that can potentially impact their innate antimicrobial susceptibility [95]. There are additional significant aspects that have the potential to restrict the effectiveness of PDI. These include the intricate composition of the food matrix, which can influence the capacity of the photosensitizer and light to penetrate, as well as engineering limitations such as the availability of light sources and the design of the PDI system [89].

Combining edible coatings formulated with antimicrobial agents could work in tandem with PDI to enhance the overall antimicrobial effect and minimize the reliance on synthetic chemicals.

4.4.2. Combination with Edible Coatings

Not many studies have been dedicated to harnessing the possible advantages that may arise from the implementation of edible coatings in conjunction with PDI on fresh produce. Nevertheless, the few studies on the subject appears extremely promising. Buchovec et al. [96], for instance, found that the application of photoactivated chlorophyllin–chitosan (Chl–CHS) complexes effectively reduced the population of Salmonella on the surface of strawberries by 2.2 log units and 1.4 log units for naturally occurring yeasts and molds. The findings demonstrated that the photoactivated Chl–CHS complex exerts its antimicrobial efficacy through a synergistic photodynamic mechanism. Upon illumination with visible light, chlorophyllin acts as a photosensitizer, transferring excitation energy to molecular oxygen and generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals [97]. These ROS induce oxidative damage to microbial cellular components, including membrane lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, ultimately leading to cell lysis and death. The chitosan component enhances this activity by promoting electrostatic interactions with negatively charged microbial cell surfaces, thereby localizing ROS action, and by contributing its intrinsic antimicrobial and film-forming properties that sustain microbial suppression post-treatment. The short diffusion radius and transient nature of ROS ensure that oxidative reactions remain confined to microbial targets on the fruit surface, preventing damage to underlying strawberry tissues and preserving their quality attributes [98]. Collectively, these mechanisms account for the substantial reductions in Salmonella populations and native yeasts and molds observed, and they highlight the potential of the photoactivated Chl–CHS system as a non-thermal, residue-free preservation strategy for fresh produce. Another investigation examined the postharvest interventions applied to fresh dates. These interventions involved the dissolution of curcumin in a propylene glycol solution, which was subsequently sprayed onto the surface of the fresh dates. Following this application, the treated dates were exposed to visible light with a wavelength of 420 nm. The findings demonstrated that the group subjected to curcumin-mediated photosensitization treatment had a shelf life exceeding three times that of the control group. Furthermore, no obvious signs of fungal infection were observed in the curcumin-treated group, in contrast to the control group which did not receive any treatment [99]. Researchers performed a preservation test and safety evaluation on cherry tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.) coated with nanocomposite films developed by incorporating graphite carbon nitride nanosheets/MoS2 nanodots into konjac glucomannan matrix. Results showed that film has a broad-spectrum antibacterial activity especially towards E. coli and S. aureus and could prolong the shelf life of cherry tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Moreover, hemolysis and cells experiment confirm that this film is safe for application on food. A recent study on the preservation of fresh-cut apples (Malus domestica) combined PDI with an edible coating made from FDA-approved chemicals (Pectin/Quercetin) and results demonstrated the coatings showed excellent antibacterial activity towards S. aureus and L. monocytogenes. Specifically, apples (Malus domestica) treated with the antibacterial coatings and with light showed no obvious microbe infestation on the surface even after 10 days in storage, while different degrees of microbial infection appeared on the apple (Malus domestica) surface in control. Aside from that, the treatment had no negative effects on the firmness or total soluble solids of the fruits, with both attributes increasing from their initial state [100]. Another recent study by [101] explored the postharvest treatments of fresh produce, including the preparation of curcumin-chitosan composite film with high antioxidant and antibacterial capacity, and highlighted the potential of this approach for microbial control on the surfaces of apples (Malus domestica) and strawberries (Fragaria ananassa). The inhibition zone of the composite film against E. coli and S. aureus was 21.4 mm and 19.9 mm, and the cell survival rate treated with film solution was 113.16%. The weight loss rate and decay rate of fruit soaked in film solution were 60% and 10% compared with untreated fruits, respectively.

4.5. Cold Plasma Treatment (CPT)

4.5.1. Theory

Plasma treatment, also known as plasma processing or plasma technology, is a versatile and interdisciplinary technology that involves the use of plasma—a unique state of matter—as a tool to modify surfaces, clean, and sterilize, as well as decontaminate, food products. The term “plasma” is widely used to describe the fourth state of matter that exist in the universe alongside solids, liquids, and gases, and depending on the mode of production, plasma can be categorized as either thermal or non-thermal based on the relative energy levels of electrons and component species [102]. Thermal or hot plasmas exhibit notable attributes such as exceedingly high energy density and elevated temperature. The sun, with its extremely high temperature, is an excellent example of thermal (hot) plasma. The sun and the aurora borealis are examples of natural plasma, whereas fluorescent lamps, plasma televisions, and commercial ozonizers are examples of man-made plasma [103]. Non-thermal or low temperature plasma treatment, also referred to as cold plasma treatment (CPT), is characterized by a non-equilibrium state. This means that while the gas temperature in a plasma can be similar to room temperature, the electrons possess high energy levels, typically ranging from 1 to 10 eV. Non-thermal plasma has the ability to efficiently break down chemical bonds, including C–O bonds, and facilitate thermodynamically unfavorable chemical processes, such as CO2 decomposition, even at normal temperatures [104]. The primary focus of practical applications and research in the subject lies in CPT, mostly due to its straightforward equipment requirements, minimal energy consumption, lack of harmful residue, and capacity to function at ambient temperature settings [105]. In this context, “cold” refers to the fact that the plasma temperature remains relatively low compared to traditional thermal plasma processes. The CPT procedure encompasses the ionization of a carrier gas consisting of unbound electrons, ions, as well as atoms and molecules existing in either their lowest energy state or a higher energy state. The ionization of the gas can be achieved through the utilization of several energy sources, such as electricity, heat, radio waves, or microwaves. There is a wide range of choices available for selecting the carrier gas. These include oxygen (O2), nitrogen (N2), helium (He), argon (Ar), and air, which can be utilized either independently or as a composite. Irrespective of which gas is used, it is essentially neutral since there are as many positive as there are negative charges carried by the many species present [106].

CPT is employed in various industries, including healthcare, food processing, and water treatment, to achieve microbial inactivation and ensure the safety and quality of products. Its versatility, effectiveness, and non-thermal nature make it a valuable tool for microbial control and surface decontamination. The following are a list of some authors that have conducted comprehensive evaluations encompassing various food products [102,107,108,109,110], rendering them valuable references. The efficacy of the CPT in terms of decontamination is dependent on a number of different parameters. These elements include the mode of the exposure, frequency range, voltage, nature of the electrode, gas composition, relative humidity, the density, temperature, length of treatment, and bacterial strain that is being treated [111]. Specifically, the potential mechanisms driving bacterial decontamination by CPT technology are the (1) etching of the outer layers of cells caused by high atomic oxygen densities and possibly ROS along with the deterioration of biological materials caused by ultraviolet photons, (2) volatilization of decomposition chemicals including excited O2, CO2, N2, etc., and (3) direct damage to plasmid DNA [112]. ROS play a vital role during bacteria cell inactivation when air or other gases containing oxygen are utilized, and furthering our understanding of their role in not only the inactivation of foodborne threats but also the modification of food matrixes is essential. Han et al. [113] studied the impact of ROS in the killing effect of CPT on bacteria. The authors observed that E. coli was inactivated mainly by microleakage in the cells as well as low-level DNA damage. Conversely, S. aureus was mainly inactivated by intracellular damage, with significantly higher levels of intracellular ROS observed and little envelope damage. They further noted that, for both bacteria studied, increasing treatment time had a positive effect on the intracellular ROS levels generated. Several other studies have also explored the inactivation efficacy of CPT on diverse food items [114,115,116,117].

Although CPT has shown promise as a method for microbiological decontamination in the food industry, incomplete sterilization caused by the limited extent of penetration of plasma species has hindered its widespread acceptance and applicability. CPT is primarily effective on the surface of food products. It may not penetrate deep into porous or dense materials, limiting its efficacy for decontaminating the interior of certain foods. The process induces ROS that are known for their ability to initiate oxidation. It is also recognized to induce oxidation of volatile constituents, resulting in unfavorable alterations [118]. Furthermore, the efficacy of CPT can also be affected by several other factors, including the type of food, its moisture content, and the specific plasma parameters used, treatment chamber configuration, electrode characteristics (materials, shape, and wear), and elucidation on the toxicity of CP-treated foods [119,120]. Optimizing these parameters for different foods can be challenging. One effective approach to overcome these limitations involves integrating CPT with other techniques for food processing and preservation. Among these options, the utilization of edible coatings shows significant potential. CPT has been utilized to increase the adhesion properties and performance of carnauba wax films in order to increase their barrier properties against microorganisms [121]. Jeon et al. [122] noted that the combined application of CPT and a coating treatment using malic acid (MA)-incorporated whey protein isolate (MA-WPI + CPT) showed superior efficacy in the inactivation of Salmonella and L. monocytogenes compared to the individual treatments in steamed fish paste. A further investigation conducted by Jeon et al. [123] yielded comparable results, indicating that the application of CPT enhanced the diffusion of MA within the coating. Consequently, this led to an enhancement in the effectiveness of the coating in inhibiting Salmonella. MA–WPI coating followed by CPT (MA–WPI + CPT) resulted in a reduction in Salmonella population (5.6 log CFU/g) in chicken breast meat by 1.8 log CFU/g. The application of MA–WPI + CPT did not provide any significant impact on the color and lipid oxidation of chicken breast meat. These findings indicate that CPT along with edible coating could be a new approach for improving its lethality against foodborne threats.

4.5.2. Combination with Edible Coatings

Edible coatings have intrinsic constraints such as poor mechanical and barrier properties, limited surface functioning, poor printability, and adhesiveness. Because of these limitations, their adoption and technical use are limited, and numerous efforts including the use of crosslinkers [124,125]; the addition of additives like plasticizers, essential oils, and antimicrobial compounds such as nisin and lysozymes [125,126] nanoparticles, and ultraviolet irradiation have been undertaken to improve their features [127,128]. CPT is a novel solution with significant implications in the field of film packaging, as it facilitates the modification of film surfaces [129]. Several studies have recently been undertaken on the effects of CPT on edible coating and film qualities in terms of modifying their properties for food packaging applications [127,129,130,131,132,133,134]. The authors of each of these investigations claimed that the CPT-modified films and coatings have the potential to be used in food antibacterial packaging. To our knowledge, however, the use of CPT-modified coatings and films to enhance the nutritional quality and microbiological safety of food products has not been thoroughly explored. Despite this, the findings of the few studies that have been undertaken on this topic show great potential. For example, the results of a recent study by Belay et al. [135] demonstrated that coating strawberries with sodium alginate followed by CPT at 80 kV for 5 min reduced yeast and mold counts by approximately 2 logs but decreased their visual appeal, whereas coated strawberries without CPT had a better appearance than the other treatments and the control. In another investigation, a chitosan-based nanocomposite film was developed and subjected to a CPT. The maximum transmission power, voltage, current, and frequency of the system were 50 W, 15 kV, 10 mA, and 50 kHz, respectively. The experiment results revealed that the mechanical properties including water vapor permeability, oxygen transmission rate, moisture content, and water contact angle characteristics were improved by cold plasma treatment. When the film was subsequently applied on strawberries (Fragaria ananassa) under modified atmosphere packaging, it improved firmness, appearance and reduced weight loss. It also led to a decrease in microbial activities (bacteria yeast and mold) on the fruits by inducing oxidative stress in spite of initial increase in aerobic bacteria yeast and mold [136]. According to the findings of [137], the implementation of a chitosan coating, along with a 120 s CPT, effectively maintained the firmness and color of pistachio. During the storage period, the treated fruits exhibited minimal levels of aflatoxin, mold, and yeast, and did not exhibit any undesirable odor or flavor. In a related study, the effect of cold plasma modification on Gelatin-carboxymethyl cellulose coatings for the preservation of blueberry, apple, and green walnut was explored. Air was used as the working gas. The flow rate, operating current, voltage, and frequency were 22.5 L/min, 0.024 mA, 19 kV, and 80 kHz, respectively. The position of the nozzle of the plasma jet generator was fixed at 15 mm below the liquid level. The treatment volume and time were 300 mL and 120 s, respectively. The results showed that combining CPT with the edible coating enhanced the preservation function of the films, reducing decay, weight loss, respiration rate, and browning [138]. It is important to note that the application of cold plasma treatment on edible coatings is still an emerging research field. Further studies are needed to investigate the effectiveness of cold plasma-modified coatings in real-life food systems, such as coatings or packaging films. Additionally, the safety of consuming food products with cold plasma-modified coatings requires toxicological validation.

5. Passive Packaging Strategy

5.1. Theory

Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) is a passive system that operates by achieving equilibrium between the respiration rate of produce and the transmission rate of gas through the packaging. This equilibrium ensures that the desired amounts of CO2 and O2 are established and maintained within the package under stable conditions. Modifying the gaseous environment around the produce often with low O2 and high CO2 levels is a crucial part of MAP system. In a MAP system, the constantly changing relationship between the metabolic and biochemical functions of the packaged food causes a shift in the concentration of gases in the packaging headspace. Headspace O2 is used up, giving rise to CO2, ethylene (a byproduct), and water vapor. Consequently, O2 from the external atmosphere will enter the packaging to replace that which the product consumes, while the other gases will leave the packaging system as excess

5.2. Combination of MAP with Edible Coatings

Fresh fruits and vegetables and their unprocessed derivatives may foster the proliferation of harmful microorganisms due to their nutrient-rich composition, elevated relative humidity, and optimal pH levels. Hence, ensuring their quality and safety remains of paramount importance within the food industry. To prevent a decline in quality, minimal contact with oxygen should occur [139]. This is achieved by employing edible films and coatings, the efficacy of which could be enhanced through the utilization of MAP. Food products that have undergone minimal or no processing may be coated prior to being sealed in a modified atmosphere bag. By employing this combination approach, the drawbacks that are inherent to relying solely on the MAP method or coating implementation are effectively mitigated. Various types of edible coatings (polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids) have been investigated for this purpose [140]. The combination of CHS and MAP, for example, has been found to increase the postharvest life of pomegranate fruit (Punica granatum) under cold storage [141]. According to the authors, the integration of chitosan coating with MAP achieved superior preservation outcomes through a multi-mechanistic synergy. Chitosan forms a semipermeable, antimicrobial barrier that limits gas and moisture exchange while inhibiting fungal growth, whereas MAP establishes a controlled external environment that suppresses respiration, delays senescence, and enhances microbial inhibition through elevated CO2 and reduced O2 levels. Together, these treatments create a harmonized microenvironment that minimizes oxidative stress, maintains structural integrity, and sustains bioactive compound stability during extended cold storage. This integrated approach successfully prolonged the postharvest life of pomegranates to six months, surpassing the storage performance reported for MAP alone [142], and exemplifying the potential of combined biopolymer coating and atmosphere modification strategies for long-term preservation of high-value horticultural commodities. Another study by Olawuyi et al. [143] suggested a similar conclusion following a study in which CHS coatings were used in combination with argon-based MAP to improve the shelf life of fresh-cut cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) The authors contend that using CHS together with MAP synergistically improved quality traits such as firmness, color, and microbial count after a 12-day storage period. The observed results were attributed to CHS polymers being able to form a barrier, which decreased the amount of gas exchange and water loss from the freshly sliced samples. Karagöz and Demirdöven [144] studied the effects of MAP on polyphenoloxidase (PPO) activity, antioxidant characteristics, and microbiological quality of fresh-cut apple (Malus domestica) slices coated with CHS with and without Stevia rebaudiana combinations. The results demonstrated that, in comparison to the control (without coating), PPO, respiration rate, and pH value of film-coated samples were reduced, while antioxidant capacity and phenolic substance values were increased. However, for a more robust coating effect to be felt, researchers have suggested the addition of calcium chloride (CaCl2), which not only functions as an anti-browning agent but also as a “firming” agent in the complex polysaccharides and proteins that make up the cell wall, preventing cell and membrane breakdown in the coated food product as well as modulate PPO activity [145]. Fan et al. [146] noted that the combined treatment of carbon dots (CDs) with chitosan (CDs/CHS) coating had a positive bacteriostasis effect on fresh-cut cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) with MAP as it effectively inhibited microbial spoilage and improved the sensory quality of the produce during the storage period. Inhibition zone diameters of CDs/CHS coating against S. aureus and E. coli were enhanced with an increase in CHS concentrations. Fan et al. [147] followed suit with a similar experiment on the preservation of fresh-cut cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) with CDs/CHS coating combined with MAP and found that the synergy between the treatments provided a favorable environment that aided in the inhibition of flavor deterioration as well as the maintenance of water distribution behavior up to the 15th day of storage. Few things can be gleaned from these two investigations: the fusion of CHS with CDs into a protective layer, which is then applied to the surface of fresh-cut produce prior to modified atmosphere packaging, formed a semipermeable barrier to decrease water vapor permeability and delayed the softening process due to reduced O2 availability and decreased metabolic rate as well as delayed microbial deterioration. The barrier properties of the CHS with CD coating altered the rate of senescence, resulting in a change in the rate of firmness increase during storage, which slowed the degrading process. Di Millo et al. [148] assayed selected antifungal lipid-based edible coatings and MAP films as stand-alone treatments or in combination to control natural decay and preserve fruit quality in pomegranates (Punica granatum). The findings of their study demonstrated the involvement of sodium benzoate, an antifungal additive, in prolonging the storage duration of fruits. This was achieved by the suppression of latent infections produced by Botrytis cinerea (B. cinerea) and wound diseases caused by Penicillium spp. The authors asserted that the utilization of a mixture consisting of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, beeswax, sodium benzoate, and MAP showed considerable potential as a treatment method. This particular combination demonstrated the ability to effectively decrease weight loss and decay, while simultaneously preserving the physicochemical and sensory attributes of the fruit. Similarly, Nasrin, Arfin, Rahman, Molla, Sabuz, and Matin [10] conducted an assessment of the effectiveness of coconut oil and beeswax edible coating, as well as MAP, in preserving green lemons (Citrus limon) during low-temperature storage. Based on an analysis of various sensory, physical, and chemical parameters, it was observed that lemons (Citrus limon) coated with a combination of coconut oil and beeswax, and subsequently packaged in a MAP, maintained their acceptability for a duration of 8 weeks. The coated lemons (Citrus limon) exhibited good quality and retained a visually appealing shiny green color. In comparison, uncoated lemons that were left open remained acceptable for only 1 week, while lemons (Citrus limon) which were coated solely with coconut oil and beeswax but left open remained acceptable for 6 weeks. Although the combination of edible coating and MAP has the potential maintain sensory traits and to restrict the proliferation of a large number of spoilage microorganisms, Severino, Ferrari, Vu, Donsì, Salmieri, and Lacroix [85] observed that the antimicrobial effectiveness of the bioactive coating with packaging under MAP was not significantly enhanced against S. Typhimurium and E. coli. These studies highlight the potential of edible coatings enriched with essential oils coupled with MAP to reduce the deterioration of nutrients and to improve the microbial safety of various food products (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of combined application of edible coatings with selected novel non-thermal techniques in various fresh produce.

6. Possible Mechanisms Through Which Edible Coatings and Selected Hurdles Induce Microbial Decontamination

Edible coatings can sustain microbiological safety of foods by using different mechanisms, including moisture control and water activity, limiting O2 availability, inducing stress, and compromising cell integrity. These mechanisms are further enhanced when used in tandem with the selected hurdles discussed in the preceding sections. The specific approach will vary depending on the product and the desired safety and quality outcomes.

6.1. Moisture Control and Reduced Water Activity

Moisture content and water activity (aw) of foods are two important factors that greatly affect microbial inactivation [167]. When the moisture content of a food product is reduced such that water activity is sufficiently low, microbial metabolism and proliferation are inhibited because the available water is no longer adequate to support enzymatic and physiological processes. Most pathogenic bacteria are unable to grow below a water activity of approximately 0.90–0.92, while Staphylococcus aureus can tolerate levels as low as 0.86 [168]. Many yeasts and molds can grow at even lower water activities, but typically not below about 0.60. Therefore, maintaining low water activity is an effective means of suppressing microbial growth and extending the shelf life of foods. Edible coatings can act as a moisture barrier, reducing the rate at which moisture evaporates from the food. This helps maintain the moisture content of the food at a desirable level, making it less susceptible to drying out and becoming a less favorable environment for microbial growth. This is particularly important for products like fresh fruits and vegetables. Some edible coatings may also incorporate antimicrobial agents, such as natural extracts or essential oils, that further inhibit microbial growth. These agents can act in tandem with moisture control and O2 barrier properties to enhance preservation.

Aw is a measure used to assess the water availability in a substance for chemical and microbiological interactions. It plays a crucial role in food preservation and ensuring product stability. Reduced aw in food restricts the proliferation of vegetative microbial cells, the germination of spores, and the production of toxins by molds and bacteria [169]. Edible coatings possess the ability to lower the water activity of food products by serving as a partial barrier to the passage of water [170]. This characteristic effectively mitigates moisture loss and alters the surrounding atmosphere of the food by impeding gas exchange, preventing biochemical reactions during storage and thereby increasing the product’s shelf life by delaying microbial spoilage [171,172]. The utilization of inert gases, such as argon, in the treatment of fresh and fresh-cut produce also has the potential to significantly decrease water activity. This reduction in water activity can effectively minimize the leaching of organic material from fresh-cut produce and the infiltration of microbes into deeper tissues. This makes inert gas treatment a promising alternative to existing pretreatment methods. In this context, combining edible coatings with MAP is crucial to achieving decreased water activity in fresh-cut produce. The main components used for edible coatings and films are lipids, polysaccharides, and proteins. Plasticizers are also added to improve the flexibility and tensile strength of the coatings, whereas moisture control and water vapor permeability prevention are obtained through the addition of resins [173].

6.2. Limited Oxygen Availability

Oxygen is essential for the growth of aerobic microorganisms (those that require O2 to grow), while others can grow in the absence of O2 (aerobic microorganisms). By reducing the O2 availability in the food environment, the growth of aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria can be limited. In some instances, edible coatings (especially those composed of lipids and most resins) may create an anaerobic environment beneath the coating, which is unfavorable for aerobic microorganisms. Using edible coatings in conjunction with MAP can be a highly successful method for lowering O2 availability and preventing microbial development in food products. This combination provides a synergistic approach to food preservation, extending the shelf life and increasing the safety of perishable foods [174]. By limiting both moisture loss (through the edible coating) and O2 availability (by MAP), a less favorable environment for microbial development and spoiling reactions is generated.

6.3. Stress and Loss of Cell Integrity

Edible coatings and high-pressure processing induce stress on microorganisms in food through different mechanisms, with the goal of eliminating or inhibiting their growth and improving the safety and shelf life of food products. Most edible coatings are formulated with antimicrobial agents, such as natural extracts, essential oils, or preservatives. These agents exert stress on microorganisms by disrupting their cellular processes and inhibiting their growth. This is particularly effective against a wide range of microorganisms, including bacteria, yeast, and molds [175,176,177]. Likewise, HPP affects the integrity of the cell, leading to leakage of cellular contents and, ultimately, cell death [178]. In this respect, HPP induces conformational changes in cell membranes and cell morphology, perturbing biochemical reactions and altering the genetic and proteomic response of microorganisms, and causes species- and environment-specific variations in the sensitivity of microorganisms. Similarly, proteins in microorganisms can undergo denaturation under high pressure. This can lead to the inactivation of essential enzymes and cellular structures, disrupting microbial metabolism and growth [179].

6.4. Homeostasis

Homeostasis refers to the inherent inclination of organisms to maintain uniformity and stability in their internal states [180]. The maintenance of physiological variables including body temperature, fluid balance, and pH within specific predetermined boundaries (known as the homeostatic range) is crucial. Any disruption in the equilibrium of these variables might result in mortality. When preserving agents, also known as hurdles, disrupt the homeostasis of foodborne microorganisms, the microbes can either stop proliferating, become inactivated, or even die [181]. Antimicrobial edible coatings can disrupt the homeostasis of microorganisms through various mechanisms, including the alteration of the internal environment [182], inhibition of microbial growth [183], and induction of oxidative stress inside the microbes through reactive oxygen species production [184].

Overall, the specific effects of edible coatings used in tandem with the selected preservation solutions on microbial growth and reproduction depend on factors such as the composition of the coating, the type of antimicrobial agents used (if any), and the characteristics of the microorganisms present. Edible coatings are a versatile tool in food preservation, and their ability to inhibit microbial growth and reproduction contributes to their effectiveness in extending the shelf life and improving the safety of food products.

7. Practical Challenges and Implications for Future Development

The compatibility of edible coatings and films with various foods is an important consideration in ensuring coatings’ effectiveness in preserving quality, extending shelf life, and maintaining the desired food product characteristics. Foods vary in their composition, including their moisture content, acidity, fat levels, and surface characteristics. These differences present a daunting task for film and coating development [185].

Furthermore, the additives in a particular edible film and coating may not be effective in eliminating all types of harmful microbes. From the literature, no single coating or film is universally suitable for all types of foods and this not only poses a problem for the advancement of coatings and films for food, as mentioned by [186], but also for their combination with other non-thermal food preservation technologies. This is because, while non-thermal technologies have been extensively explored, the majority of studies on their integration with coatings were still performed in a laboratory, with only a few substantial trials in an industrial context.

Furthermore, the combined application of edible coatings and non-thermal techniques can induce unfavorable changes in food products. These modifications could emerge as changes in taste, changes in how food feels in the mouth or on the tongue, or even noticeable changes in how food looks overall. Some edible coatings, for example, may become excessively brittle or hard at low temperatures, as mentioned by [187].

Similarly, in addition to their antimicrobial properties, HPP, irradiation, PDI, and CP have the potential to induce alterations in protein structure or interfere with cell membranes, which may ultimately impact the texture of food. For instance, prolonged exposure of raspberries (with softer surface texture) to pulsed light resulted in structural damage, which benefited microbial growth [188]. HPP treatment between 200 and 300 MPa induced some modifications which can influence protein structure, lipid oxidation, and product appearance. Nevertheless, there is a lack of uniformity in the data regarding the impact of these alterations on consumers’ perceptions [189]. Due to the aforementioned challenges, the texture of the coated food product may be adversely affected by the additive effects of edible coatings and the various non-thermal processing techniques; this may result in a less appetizing product, particularly one that becomes difficult to bite or chew.

Food producers may have to take note of the following important considerations to ensure the microbiological safety, quality, and regulatory compliance of their products: (1) Ensure that the ingredients used in edible coatings are compatible with selected hurdle techniques because some materials may react adversely or lose their effectiveness under certain conditions. (2) Validate the combined preservation process to ensure it effectively extends shelf life, maintains product quality, and meets safety standards. This includes determining appropriate process parameters for each technique. (3) Be vigilant about cross-contamination and allergen management when incorporating additional ingredients into edible coatings. Ensure that allergen information is clearly labeled on the packaging. (4) Perform shelf-life studies to determine the expected duration of product quality and safety under different storage conditions, considering the combined effects of all preservation methods. By addressing these considerations and conducting thorough research and testing, food producers can successfully combine edible coatings with the selected preservation techniques to create safer, higher-quality, and longer-lasting food products that meet consumer demands and regulatory requirements.

8. Conclusions

The combined use of edible coatings and non-thermal preservation technologies offers a promising direction for advancing postharvest quality management through complementary mechanistic actions. Edible coatings provide controlled mass-transfer regulation and serve as carriers for functional bioactives, while non-thermal interventions apply targeted physical or chemical effects that enhance microbial stability, preserve quality attributes, and in some cases improve coating functionality. Together, these approaches form an integrated preservation system that aligns with low-energy and sustainability goals.

To facilitate wider application, future work should focus on scalable processing strategies, ensuring compatibility between coating formulations and specific non-thermal treatments across varied horticultural products. Rigorous safety evaluations and clearer regulatory frameworks will be essential for commercial adoption, alongside systematic assessment of consumer acceptance. Furthermore, environmental impact analyses, including life-cycle assessments, are needed to quantify the sustainability benefits of these integrated methods. Addressing these considerations will be key to translating laboratory innovations into practical, sustainable solutions for reducing postharvest losses.

Going forward, future research will need to bridge formulation compatibility gaps, improve control over sensory changes introduced by combined treatments, and accelerate the transition from laboratory studies to industrial-scale validation. These advances will ultimately enable more consistent, consumer-acceptable, and sustainable preservation systems across horticultural supply chains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.T. and J.H.A.; methodology, X.Z., Q.F. and C.D.; formal analysis, C.D.; investigation, H.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.D.; visualization, J.H.A.; funding acquisition, X.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20230523).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chandra, R.D.; Prihastyanti, M.N.U.; Lukitasari, D.M. Effects of pH, High Pressure Processing, and Ultraviolet Light on Carotenoids, Chlorophylls, and Anthocyanins of Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Juices. eFood 2021, 2, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepiórka-Stepuk, J.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Sterczyńska, M.; Mierzejewska, S.; Stachnik, M.; Jakubowski, M. The effect of heat treatment on bioactive compounds and color of selected pumpkin cultivars. LWT 2023, 175, 114469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]