Abstract

This study investigated the phylogenetic relationships in the pear calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK) pan-gene family and elucidated its role in the resistance to scab disease caused by Venturia nashicola. By integrating data from eight genomic sets from five cultivated pear species, Pyrus bretschneideri, P. ussuriensis, P. sinkiangensis, P pyrifolia, and P. communis, along with P. betulifolia and interspecific hybrids, 63 PyCDPK family members were identified. Among these, P. communis possessed the highest number of CDPK genes, whereas P. bretschneiderilia had the fewest. These genes encode proteins ranging from 459 to 810 amino acids in length, and are predominantly localized to the cell membrane. Six genes, PyCDPK9, PyCDPK11, PyCDPK12, PyCDPK14, PyCDPK16, and PyCDPK19, were classified as core members of the pan-genome, and PyCDPK19 showed evidence of positive selection pressure. Clustering analysis and transcriptomic expression profiling of disease-resistance-related CDPKs identified PyCDPK19 as a key candidate associated with scab resistance. Promoter analysis revealed that the regulatory region of PyCDPK19 contains multiple cis-acting elements involved in defense responses and methyl jasmonate signaling. Transient overexpression of PyCDPK19 in tobacco leaves induced hypersensitive cell necrosis, accompanied by significant increases in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation and malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Similarly, overexpression in pear fruit callus tissue followed by pathogen inoculation resulted in elevated levels of both H2O2 and MDA. Collectively, these findings indicate that PyCDPK19 mediates defense responses through the activation of the reactive oxygen species pathway in both tobacco and pear plants, providing a promising genetic target for enhancing scab resistance in pears.

1. Introduction

Throughout their life cycle, plants are exposed to various abiotic and biotic stresses, including drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and pathogenic infections [1]. A substantial body of research has demonstrated the pivotal role of calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) in plant response to environmental stress. For example, AtCPK3 confers drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana [2], LpCDPK27 positively regulates salt tolerance in Lolium perenne [3], and ShCDPK6 and ShCDPK26 enhance cold tolerance in Solanum habrochaites [4]. In Fragaria vesca, FvCDPKs are upregulated upon infection with pathogenic fungi [5], whereas AcoCPK1, AcoCPK3, and AcoCPK6 negatively regulate pathogen resistance in Ananas comosus [6]. As key Ca2+ sensors, CDPKs directly transmit upstream Ca2+ signals to downstream target proteins via phosphorylation, thereby activating signaling pathways and playing crucial roles in various plant stress responses [7]. Several CDPKs have been reported to positively or negatively regulate pathogen resistance via different mechanisms. Further research is necessary to elucidate the specific roles of CDPKs in horticultural crops.

Pear (Pyrus spp.), a member of the Rosaceae family, is an important economic crop in various regions of China, including arid, semi-arid, semi-humid areas and the rainfall-rich regions of southern China [8]. It is widely cultivated in different environments such as dry, low-rainfall mountainous regions, along riverbanks, in saline-alkali soils as well as in areas with abundant rainfall, where it may encounter diverse biotic and abiotic stresses [9]. However, the effects of pear disease on the yield, quality, and economic returns cannot be overlooked. Pear scab, caused by the fungus Venturia nashicola, is one of the most destructive diseases affecting pear-producing regions in China. This fungal disease causes spots and rot on fruits during both growth and storage, significantly reducing their commercial value [10,11,12]. Conventional disease control measures for pear trees require substantial investment in labor, materials, and financial resources [13]. Therefore, it is essential to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the genetic networks that confer resistance to pear scab.

The pear genome exhibits significant heterozygosity, primarily driven by self-incompatibility mechanisms that promote cross-pollination along with long-term accumulation of genetic variation over millennia of clonal propagation [14]. The reference genomes have been published for several economically and horticulturally important pear species and cultivars. These include the Chinese white pear (P. bretschneideri), a major commercial species widely cultivated in northern China; the European pear (P. communis), which is grown globally in temperate regions and valued for its soft, juicy fruits; the Japanese pear (P. pyrifolia), known for its crisp texture and russeted skin, and predominantly cultivated in East Asia; and the Chinese cultivar ‘Cuiguan’ known for its early maturation and high yield [15,16]. In addition, genomic resources are available for the dwarf rootstock ‘Zhongai 1,’ a hybrid of P. ussuriensis—a cold-tolerant species native to Northeast Asia—and P. communis [17], and P. betulifolia, a rootstock originating from northern China, valued for its resistance to abiotic stresses and adaptability to poor soils and can be utilized globally, including in southern China and Japan [18]. Nevertheless, existing studies have predominantly focused on analyzing individual genomes. For example, only 30 members of the CDPK gene family have been identified in P. bretschneideri [19], and no related studies have been reported in other pear species. Conventional single-reference genomes face challenges in comprehensively capturing intraspecific genetic diversity, particularly within the genus Pyrus, where recurrent interspecific hybridization events create complex genetic backgrounds and reduce representativeness [20]. Consequently, the pan-genome concept, originally proposed for bacterial genetics, has been adapted for applications in plant genomics. This approach has emerged as a pivotal strategy for assessing species-level genetic diversity [21]. As the number of pear species with published genomes continues to increase, there is an urgent need to systematically integrate the existing genomic resources. This integration is essential for optimizing the genetic information system of the pear genus, enabling a more accurate assessment of the intraspecific genetic diversity and its underlying evolutionary mechanisms.

This study aimed to comprehensively identify and characterize the CDPK gene family across multiple pear genomes and investigate its functional role in the response to scab disease. The specific objectives included the following: (1) constructing a pan-genomic resource integrating eight pear genomes, encompassing five cultivated pear species (P. bretschneideri, P. ussuriensis, P. sinkiangensis, P. pyrifolia, and P. communis), the wild species P. betulifolia, and interspecific hybrids; (2) systematically identifying all CDPK family members and analyzing their phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, and evolutionary histories; (3) analyzing the expression profiles of pear CDPK candidate genes during pear fruit scab infection based on transcriptomic data; (4) validating the in vivo functions of key candidate genes using a pear callus transient overexpression system; (5) confirming the disease-resistance function of core candidate genes through heterologous expression in tobacco. This multi-tiered approach integrated bioinformatics and transcriptome analyses with in vitro and in vivo functional assays, providing novel insights into CDPK-mediated resistance mechanisms in pear and supporting future molecular breeding efforts. This integration established a foundational resource repository for the pan-genomic analysis of pear.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

This study used plant materials from both resistant and susceptible pear cultivars for various experiments. Two-year-old potted plants of the scab-resistant cultivar ‘Huangguan’ and the scab-susceptible cultivar ‘Xuehua’ [22] were maintained under standard greenhouse conditions (25 °C, 16/8 h light/dark cycle) and used for pathogen inoculation and transcriptome analysis. For the transient expression assays, leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana plants (grown in a growth chamber at 25 °C for 4–5 weeks) and fruit-derived callus of the ‘Xuehua’ pear were used.

Healthy disease-free leaves at similar developmental stages were selected from both ‘Xuehua’ and ‘Huangguan’ plants. The abaxial surfaces of the leaves were gently wounded using a sterile needle. A conidial suspension of V. nashicola at a concentration of 1.0 × 105 spores/mL was evenly applied to wounded areas. The inoculated leaves were then covered with transparent plastic bags to maintain a high humidity. The control leaves were treated similarly, but with sterile water instead of the spore suspension. Three independent biological replicates were performed for each treatment and time point with each replicate consisting of a pool of leaves from three different plants per treatment. Leaf samples were collected at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h post-inoculation (hpi), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction.

2.2. Identification of the Pear PyCDPK Gene Family

The plant materials used in this study comprised accessions of several major pear species. The cultivars included ‘Dangshan Suli’ (Py-DS) and ‘Xuehua’ (Py-XH), both belonging to the species P. bretschneideri [16,23]; ‘Nanguoli’ (Py-NG) from P. ussuriensis [24]; ‘Kuerle Xiangli’ (Py-KE) from P. sinkiangensis [25]; and ‘Shinseiki’ (Py-XS) from P. pyrifolia [26]. The cultivar ‘Clapp’s Favorite’ (Py-QL), which is derived from the European species P. communis [27], was also included. In addition, the selection encompassed interspecific hybrids and grafted materials, particularly the hybrid cultivar ‘Zhongai 1’ (Py-ZH) [17], which possesses a genetic background of both P. ussuriensis and P. communis, and an individual of P. betulifolia (Py-DL) [18], which was grafted onto the rootstock of wild pear species.

Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles of the protein kinase domain (PF00069) and the EF-hand domain (PF13499) were retrieved from the Pfam database. (http://pfam.xfam.org/ (accessed on 5 May 2025)). CDPK domains were identified using HMMER v3.3.2, with an e-value threshold of <1 × 10−5. The SMART database (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ (accessed on 5 May 2025)) was used to confirm the presence of conserved CDPK domains in candidate genes from the eight pear accessions [28]. Furthermore, to complement the domain-based approach and minimize omissions, a synteny-based analysis was used to identify additional family members that were not detected by the initial HMM searches. Genes within the collinear regions that exhibited homology to the confirmed CDPKs were included in the final set of CDPK family members.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Presence/Absence of PyCDPKs

For phylogenetic analysis, the protein sequences of CDPKs from the eight pear accessions, along with their homologous sequences from other plant species relevant to disease resistance, were aligned using MAFFT v7.490 [29]. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using MAFFT v7.490 and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using FastTree v2.1.11. The final graphics were generated using iTOL v6 (https://itol.embl.de/ (accessed on 10 May 2025)) [30]. To visualize the distribution of the identified CDPK genes across the eight accessions, a heatmap illustrating the presence or absence of each gene was generated using R v4.0.3 and the ComplexHeatmap package [31].

2.4. Cis-Acting Element Analysis of PyCDPKs and Ka/Ks Calculation

The TBtools-II software v2.0125 was used to obtain the 2000 bp sequence upstream of the start codon of the CDPK gene, and the obtained sequence was subnitted to the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/ (accessed on 6 May 2025)) to predict the cis-acting elements present [32].

The protein and coding sequence (CDS) sequences of the CDPK genes in the eight pear genomes were obtained from the Pear Genome Database (http://pyrusgdb.sdau.edu.cn (accessed on 8 May 2025)). PyCDPK sequences were compared and Ka/Ks values were calculated using the KaKs Calculator [33]. The R packages ggridges and ggplot2 v4.0.3 were used to create the Ridgeline plot of the Ka/Ks value [34,35].

2.5. RNA-Seq Data Analysis

For the disease-resistant cultivar ‘Huangguan’ and the disease-susceptible cultivar ‘Xuehua,’ the changes in their expression levels were analyzed after pear scab infection. The transcriptomic data used in this study were generated de novo by BGI Cloud Platform (Beijing, China) using RNA sequencing technology. Low-quality sequences were removed using Fastp [36]. Clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using Hisat 2 [37]. HTSeq was used to obtain read counts for each gene [38]. Differentially expressed genes were identified using a threshold of |log2 fold-change| > 1 and FDR ≤ 0.05. Heatmaps were generated using log2(RPKM + 1) values with R v4.0.3, and the Complex Heatmap package version 2.6.2 [31].

2.6. Induction of Callus Formation and Transient Overexpression in Pear Callus

Mature disease-free fruits of the ‘Xuehua’ cultivar were selected and superficially disinfected with 75% ethanol for 40 s, followed by 0.1% HgCl2 for 20 min. Sterile fruits were peeled, cut into small pieces (10 × 10 mm) with a thickness of 1 mm, and inoculated into a medium containing a combination of MS medium, 0.5 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA), and 2 mg/L 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), supplemented with 6% (w/v) agar and 3% (w/v) sucrose (All chemicals mentioned above were purchased from Solarbio, Beijing, China). The pH was maintained at approximately 5.8, and incubations were conducted in the dark at 25–28 °C for 30 days. The induced callus cultures were transferred to medium containing MS, 1 mg/L 6-BA, and 1.5 mg/L 2,4-D. After 25 days, uniform and vigorous callus cultures were selected for further analysis.

To investigate the function of PyCDPK19 in response to V. nashicola infection, a transient overexpression assay was performed in pear calli using an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated system [39]. The overexpression construct pEGOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19 and the empty vector control pEGOEP35S-H were introduced into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101. The bacterial cultures were resuspended in infection buffer to an OD600 of 0.8. For agroinfiltration, calli were vacuum-infiltrated with the bacterial suspension, transferred to MS medium, and incubated in the dark for 48 h. Subsequently, the calli were inoculated with V. nashicola mycelial plugs and cultured in the dark for another 48 h in a tissue culture room before further analysis.

2.7. Measurement of Physiological Indicators

DAB staining was performed on tobacco leaves at 72 h after infiltration with Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying either the empty vector (pEGOEP35S-H) or the overexpression construct (pEGOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19). A 1 mg/mL DAB solution was prepared in a beaker. Subsequently, the treated leaves were harvested and immersed in DAB solution. The samples were incubated in the dark at 25 °C for approximately 8 h. Thereafter, the staining solution was discarded. The stained leaves were transferred to a beaker containing 95% ethanol and boiled for 10 min in a fume hood. After decolorization, the leaves were transferred to fresh 95% ethanol and incubated until the background color was completely removed. Finally, the phenotype was observed and documented through photography.

To determine the H2O2 content, 0.1 g of plant tissue was placed in a mortar, 0.9 mL of 0.1 mol/L phosphate-buffer solution was added, and the mixture was ground thoroughly on ice until a homogeneous slurry was formed. The slurry was transferred to a 2 mL centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at low temperature. The supernatant was pipetted for testing, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

To determine malondialdehyde (MDA) content, 0.5 g of plant tissue was weighed and placed in a clean mortar, a small amount of quartz sand and 2 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added, and the mixture was ground into a paste. The homogenate was transferred to a 10 mL centrifuge tube. The mortar was rinsed with 3 mL of 5% TCA, and the extraction solutions were then combined. Then, 5 mL of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) solution was added to the extraction solution, mixed thoroughly, and boiled at 100 °C in a water bath for 10 min. The mixture was rapidly cooled on ice, centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. Using a 0.5% TBA solution as a control, the absorbance values were mesured at 450, 532, and 600 nm, and the MDA concentration was calculated using the following formula: MDA concentration (mmol/g FW) = 6.452 × (A532 − A600) − 0.559 × A450.

2.8. Data Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The normality of the data distribution was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. After this validation, the significance of differences between mean values (p < 0.05) was analyzed by Student’s t-test using SAS v9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Identification of PyCDPK Pan-Gene Family Members

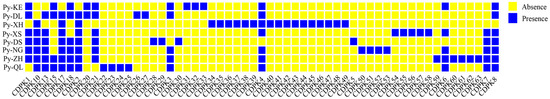

In this study, the members of the CDPK gene family were identified in eight different pear species, including wild species and interspecific hybrids. Specifically, 23 members were identified in Py-XH, 30 in Py-KE, 34 in Py-QL, 33 in Py-DS, 25 in Py-DL, 25 in Py-ZH, 27 in Py-NG, and 30 in Py-XS. After grouping homologous genes, 63 PyCDPK family members were identified. In addition to non-core and private genes, the core genes PyCDPK9, PyCDPK11, PyCDPK12, PyCDPK14, PyCDPK16, and PyCDPK19, which are present in all genomes, may play important regulatory roles in pear growth and development. Analysis of the presence and absence of CDPK genes in their pan-genome revealed that some CDPK genes outside the core gene set were variably present (Figure 1). For example, PyCDPK1 was absent in the Py-XH and Py-QL cultivars but was present in all other cultivars; PyCDPK5 was found only in Py-DS and Py-ZH, and PyCDPK34 was exclusive to Py-DL. These results indicate significant differences in specific gene loci among pear species, with certain genes present in some species but absent in others. This variation may be related to the adaptability of the species, their stress resilience, and agronomic traits.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the presence and absence of CDPKs in pear genotypes. Py-KE: Kuerle Xiangli; Py-DL: an individual of P. betulifolia; Py-XH: Xuehua; Py-XS: Shinseiki; Py-DS: Dangshan Suli; Py-NG: Nanguoli; Py-ZH: Zhongai 1; Py-QL: Clapp’s Favorite; yellow indicates gene absence; blue indicates gene presence.

3.2. Physicochemical Properties of PyCDPKs

To investigate potential differences among the 63 CDPK genes across various pear genomes, we analyzed their physicochemical properties, including amino acid composition, relative molecular weight, isoelectric point, and hydrophilicity. As shown in Table 1, the predicted lengths of the CDPK proteins ranged from 459 to 810 amino acids (aa), with seven CDPKs having a predicted length of 572 aa. However, other CDPKs exhibited considerable variations in protein length across the eight pear species. Compared with other pear CDPKs, PyCDPK5 was notably longer, which may have resulted from a delayed stop codon or segment insertion. Conversely, PyCDPK46 had the shortest sequence, possibly due to an early stop codon or a segment deletion. The molecular weights of the 63 CDPK family members ranged from 21.81 kDa (PyCDPK55) to 62.19 kDa (PyCDPK30). The theoretical isoelectric points (pI) varied from 5.12 (PyCDPK63) to 9.08 (PyCDPK63), with 8 members exhibiting a pI > 7 and 56 members having a pI < 7, indicating that CDPK proteins in pears are predominantly acidic. The instability coefficients ranged around 38, with most CDPK family members having an instability index > 40, suggesting that these proteins are generally unstable and may have a relatively short lifespan. The average hydrophilicity values ranged from −0.56 (PyCDPK51) to −0.564 (PyCDPK48), indicating that the CDPK proteins are hydrophilic. Subcellular localization predictions revealed that 33 CDPKs were localized to the cell membrane, 10 to the cytoplasm, 10 to both the cytoplasm and nucleus, 8 to both the cytoplasm and cell membrane, and only 2 exclusively within the nucleus.

Table 1.

Sequence characteristics of CDPK gene family in pear.

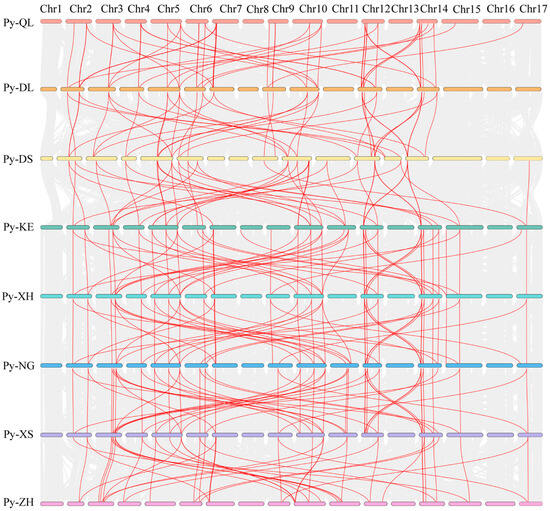

3.3. Colinearity Analysis of PyCDPKs

Analysis of the gene distribution of CDPK gene across 17 chromosomes in the eight pear genomes revealed extensive collinearity among the chromosomes of the different cultivars (Figure 2). Numerous red collinearity lines connect the chromosomes across diverse cultivars. This finding indicates a significant degree of genomic collinearity among the pear cultivars. The chromosomes of each cultivar exhibited varying degrees of collinearity with those of the other cultivars. Furthermore, these blocks were not uniformly distributed across the chromosomes. Notable differences were observed between wild and cultivated accessions. The wild species P. betulifolia (Py-DL, used as a rootstock) and European pear species P. communis (Py-QL) exhibited more extensive collinear networks than the cultivated accessions. In particular, dense collinearity was observed between these two species, indicating strong conservation of CDPK gene organization. Among cultivated accessions, the Chinese white pear (P. bretschneideri) cultivars ‘Dangshan Suli’ (Py-DS) and ‘Xuehua’ (Py-XH), and the Xinjiang pear (P. sinkiangensis) cultivar ‘Kuerle Xiangli’ (Py-KE) showed relatively conserved collinearity patterns, though with some unique rearrangements. The interspecific hybrid rootstock ‘Zhongai 1’ (Py-ZH, derived from P. ussuriensis and P. communis) exhibited intermediate patterns, sharing collinear relationships with both wild and cultivated accessions.

Figure 2.

Collinearity analysis of PyCDPKs in pear genotypes. Py-QL: Clapp’s Favorite; Py-DL: an individual of P. betulifolia; Py-DS: Dangshan Suli; Py-KE: Kuerle Xiangli; Py-XH: Xuehua; Py-NG: Nanguoli; Py-XS: Shinseiki; Py-ZH: Zhongai 1; Chr1-17 represents the 17 chromosomes.

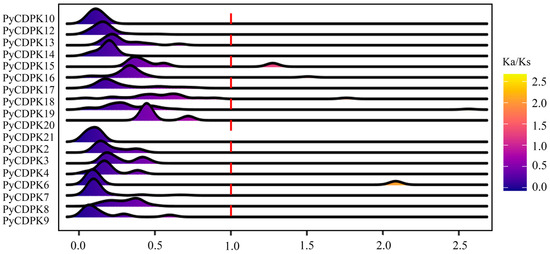

3.4. Selection Pressure Analysis of PyCDPKs

A detailed analysis of selective pressure across members of the pear PyCDPK pan-gene family revealed that different members have been subjected to varying selective pressures throughout evolution. The results revealed a wide spectrum of selective pressures among different PyCDPK genes (Figure 3). Most PyCDPK genes exhibited Ka/Ks ratios less than or close to 1, indicating that they evolved under strong purifying selection. In contrast, a subset of genes, including PyCDPK6, PyCDPK15, PyCDPK16, PyCDPK18, and PyCDPK19, showed Ka/Ks ratios significantly >1, suggesting positive selection on these genes. The distribution of Ka/Ks values across the gene family highlights the diversity of evolutionary pressures that have shaped the different CDPK members in the pear.

Figure 3.

Ka/Ks values for PyCDPKs in pear genotypes. The Ka/Ks ratio represents the non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitution rates, indicating evolutionary selection pressure on genes. The red dashed line represents Ka/Ks = 1.

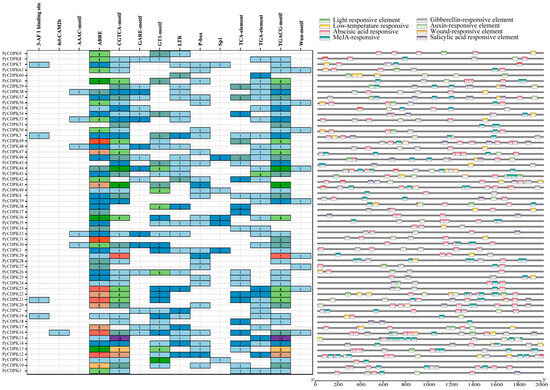

3.5. Cis-Acting Element Analysis of PyCDPKs

Gene expression in living organisms is regulated by cis-acting promoter elements. In the present study, we analyzed the cis-acting elements of the PyCDPKs, a member of the pear pan-gene family (Figure 4). PyCDPKs contain a variety of cis-acting elements, which have been demonstrated to play a crucial role in transcriptional regulation. The presence of light-responsive elements in PyCDPK suggests the potential for these genes to participate in plant light signal transduction pathways, thereby responding to environmental signals such as photoperiod, and regulating plant growth and development. Furthermore, a significant proportion of genes have been found to contain plant hormone response elements, including gibberellin and brassinosteroid, suggesting that PyCDPKs play a pivotal role in plant hormone signaling pathways. This suggests that PyCDPKs may influence plant growth, development, and stress responses by regulating plant hormone metabolism or signaling pathways. Certain PyCDPKs are characterized by high-density hormone response elements, including methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and salicylic acid (SA). This finding suggests a potential role for these genes in plant defense responses and in the management of biotic stresses, such as pathogen invasion. The cis-acting elements exhibited a high degree of conservation in both wild and cultivated species, suggesting their potential as core regulatory elements retained during pear evolution. These elements are believed to be critical for maintaining fundamental growth and development processes. Conversely, elements that have undergone changes or that exhibit specificity in cultivated species may be associated with human domestication and selection. Such alterations may potentially confer unique growth habits, fruit quality, or stress tolerance to cultivated species.

Figure 4.

Cis-acting element analysis of PyCDPKs in pear genotypes. The colors and numbers in the graphic represent the count of cis-acting elements present in each gene.

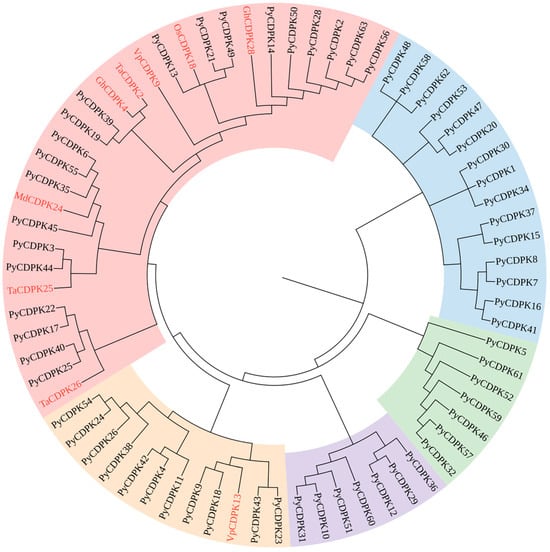

3.6. Phylogenetic Analysis of PyCDPKs

In this study, a comprehensive analysis of eight pear genomes was conducted to identify 63 members of the PyCDPK family. These members were further classified into six core genes, 13 near-core genes, three non-core genes, and 41 private genes. To gain deeper insight into the evolutionary relationships within the PyCDPK family and to determine their potential roles in disease resistance, a comparison was made between these 63 PyCDPK genes and previously identified disease-related CDPK genes (Figure 5). This comparsion included the rice OsCDPK18 gene, which is associated with wilt disease resistance. A phylogenetic tree was constructed to explore the relationships among wheat genes TaCDPK2, TaCDPK25, and TaCDPK26 (linked to resistance to stripe rust), grape powdery mildew-related genes VpCDPK9 and VpCDPK13, apple anthracnose-related MdCDPK24, and upland cotton yellow wilt-related GhCDPK4. The results demonstrated that CDPK genes associated with disease resistance clustered significantly within a specific subfamily, suggesting that these genes may play a pivotal role in the disease resistance mechanisms of pears. This finding offers a new perspective on the evolutionary history of the PyCDPK family and provides a crucial molecular basis for future studies on disease resistance gene function and pear disease resistance breeding.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of PyCDPKs in pear genotypes and disease-related CDPKs from other plant species. It contains 63 identified PyCDPKs and previously reported disease-resistance CDPK homologs from other species, with those highlighted in red representing rice (OsCDPK18), wheat (TaCDPK2, TaCDPK25, TaCDPK26), grape (VpCDPK9, VpCDPK13), apple (MdCDPK24), and cotton (GhCDPK4). The different-colored arcs represent distinct phylogenetic subfamilies.

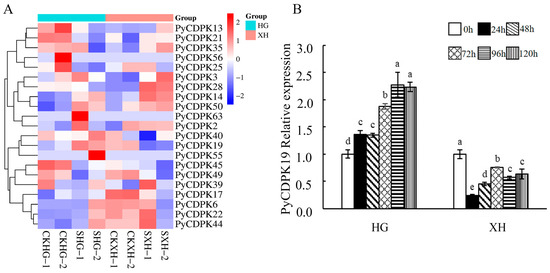

3.7. Response of PyCDPKs to V. nashicola

To analyze the response of PyCDPKs to V. nashicola infection, the transcriptomic data of PyCDPKs from the first subfamily were compared between the disease-resistant cultivar ‘Huangguan’ and the susceptible cultivar ‘Xuehua’ after infection (Figure 6). In this study, we systematically elucidated the expression patterns of CDPKs. The results demonstrated that PyCDPK19 was significantly expressed after scab fungus infection, showing upregulation in the resistant cultivar and downregulation in the susceptible cultivar. To further investigate the role of PyCDPK19 in pear response to scab fungus infection, infected leaves were collected at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h post-infection. In the ‘Huangguang’ pear, PyCDPK19 expression was upregulated 24 h post-infection, peaking at 96 h with an approximate 2.28-fold increase compared with pre-infection levels. In contrast, PyCDPK19 expression was consistently downregulated throughout the infection process in the ‘Xuehua’ pear. These findings indicate that PyCDPK19 exhibits significantly different responses to V. nashicola infection across pear cultivars, suggesting a potential functional role in pear disease resistance mechanisms.

Figure 6.

Response of PyCDPKs to V. nashicola. (A): Expression levels of subfamily I PyCDPKs after V. nashicola inoculation. (B): Relative expression of PyCDPK19. CKHG: mock-inoculated ‘Huangguan’ pear (resistant); CKXH: mock-inoculated ‘Xuehua’ pear (susceptible); SHG: V. nashicola-inoculated ‘Huangguan’ pear; SXH: V. nashicola-inoculated ‘Xuehua’ pear. Each treatment included two biological replicates. Leaf tissues were collected at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h post-inoculation (hpi). Each treatment included three biological replicates. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among groups (p < 0.05).

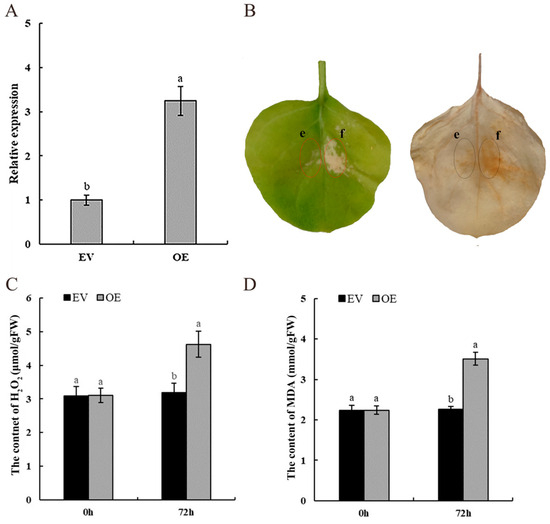

3.8. Transient Expression of PyCDPK19 in Tobacco

To conduct a preliminary investigation of the function of PyCDPK19, the gene was transiently overexpressed in tobacco leaves (Figure 7A). Injection of tobacco leaves with pEGOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19 resulted in cellular necrosis, whereas no significant changes were observed in the control group. DAB staining revealed that the necrotic areas were yellowish-brown, indicating that the transient expression of PyCDPK19 induced cellular necrosis in the tobacco leaves (Figure 7B). Furthermore, H2O2 and MDA levels were measured in tobacco leaves at 72 h after transient infiltration. The results demonstrated that the levels of H2O2 and MDA in tobacco leaves injected with pEGOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19 were significantly higher than those in the control group (Figure 7C,D). These findings suggest that the transient expression of PyCDPK19 in tobacco leaves induces hypersensitive necrosis and H2O2 accumulation. This finding implies that PyCDPK19 expression may inhibit the spread of pathogens, thereby enhancing disease resistance.

Figure 7.

Transient expression of PyCDPK19 in tobacco. (A): Relative expression of PyCDPK19 in tobacco leaves overexpressed for 72 h. (B): Transient overexpression of PyCDPK19 induces a hypersensitive response, displayed as a phenotype, and DAB staining at 72 h. e: pEGOEP35S-H; f: pEGOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19. (C): Determination of H2O2 content after transient overexpression of PyCDPK19 in tobacco leaves for 72 h. (D): Determination of MDA content after transient overexpression of PyCDPK19 in tobacco leaves for 72 h. EV: pEGOEP35S-H treatment; OE: pEGOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19 treatment. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

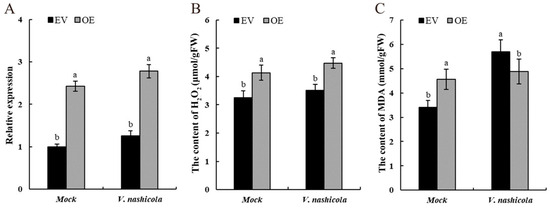

3.9. Transient Expression of PyCDPK19 in Pear Calli

To validate the role of PyCDPK19 in the response of pear callus tissue to V. nashicola infection. PyCDPK19 was transiently overexpressed in the tissue (Figure 8A). The H2O2 content in calli overexpressing PyCDPK19 significantly increased (Figure 8B), suggesting that PyCDPK19 may promote ROS accumulation in response to pathogen infection. Furthermore, a significant increase in MDA content was observed in the overexpressing calli (Figure 8C), indicating enhanced lipid peroxidation of the cell membranes and elevated ROS levels. Collectively, these results indicate that PyCDPK19 plays a role in the defense response against scab fungus infection in pear callus tissue by regulating ROS levels and lipid peroxidation.

Figure 8.

Transient PyCDPK19 expression in pear calli. (A): Relative expression of PyCDPK19 in pEGOEP35S-H and pEGOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19 calli after V. nashicola infection. (B): Determination of H2O2 content in calli transiently overexpressing PyCDPK19 after inoculation with V. nashicola. (C): Determination of MDA content in calli transiently overexpressing PyCDPK19 after inoculation with V. nashicola. Different lowercase letters show significant differences (p < 0.05). EV: pEGOEP35S-H treatment; OE: pE-GOEP35S-H-PyCDPK19 treatment.

4. Discussion

Conventional gene family analysis is typically performed using a single reference genome. In contrast, pan-genome analysis enables more comprehensive and in-depth examination of gene families [40,41]. A comparison of the CDPK family members identified in P. bretschneideri [19] with those found in the pan-genome across different species revealed significant discrepancies. Specifically, the Py-XH and Py-DS cultivars, both of which belong to P. bretschneideri, contained 23 and 33 CDPK family members, respectively. We consider that this discrepancy is unlikely to be attributed to adaptation to distinct cultivation environments, given the relatively recent domestication history of pear (approximately 3000 years) and the significant role of human activity in cultivar distribution and evolution. Instead, the most plausible explanation lies in technical variations, such as differences in genome sequencing depth, assembly continuity, and annotation quality between the two cultivars. Throughout evolution, organisms experience gene duplication and loss events. While the observed difference in gene number may not directly reflect environmental adaptation in this case, it highlights the dynamic nature of gene families. Similarly to the expansion and functional diversification observed in the PEBP gene family of cannabis plants, the variation in CDPK member count between pear cultivars underscores the genomic diversity that can exist within a species [42]. CDPK proteins are primarily localized in the plasma membrane, which aligns with their roles in sensing and responding to calcium signals, activating downstream signaling pathways, and mediating plant responses to environmental stress. The influx of calcium ions (Ca2+) into the cell is facilitated by calcium ion channels located on the cell membrane, leading to an increase in the intracellular calcium ion concentration. At this stage, the calcium-binding domain (EF-hand) of CDPK recognizes and binds to free calcium ions, including a conformational change that activates kinase activity and transmits a calcium signal downstream [43]. Similarly, citrus CNGC proteins are localized in the plasma membrane and function as ion channels involved in calcium transmembrane uptake [44]. The genus Pyrus exhibits a complex phylogenetic structure, with a fundamental split between Oriental (Asian) and Western (European) pears estimated to have occurred 5–7 million years ago [15]. Within this evolutionary framework, early-diverging wild species such as P. betulifolia are considered to retain ancestral genetic signatures [45]. Following this divergence, domestication proceeded independently in different regions: P. pyrifolia, P. bretschneideri, and P. ussuriensis were domesticated in China, while the European pear (P. communis) was domesticated in West Asia and Europe [46]. A more recent development is the emergence of hybrid cultivars such as Kuerle Xiangli, which originated from natural crossing between Chinese sand pears and European pears, representing genetic admixture between the two major lineages [47]. Our collinearity analysis aligns with this phylogenetic history, indicating that wild accessions Py-DL and Py-QL are phylogenetically closer to the ancestral state and harbor more ancestral genomic content. In cultivated species, we observed evidence of selection, with genes related to agronomic traits such as disease resistance and fruit quality being retained through positive selection.

Most PyCDPK genes exhibited Ka/Ks values close to or below 1, indicating that PyCDPK genes underwent purifying selection after duplication. A similar phenomenon was observed in grapes, in which duplicated genes primarily underwent purifying selection, thereby maintaining high levels of functional conservation [48,49]. The Ka/Ks value of PyCDPK19 was >1, indicating that it underwent positive selection pressure during evolution. This pattern closely resembles that of the sorghum anthracnose resistance gene AGR4, which also exhibits a Ka/Ks ratio > 1 and has undergone positive selection. This may be associated with the adaptability of pears to various stresses, such as pathogens and environmental challenges [50].

Most members of the pear CDPK gene family have promoter regions containing cis-regulatory elements that respond to MeJA and SA signals as well as stress tolerance. This finding aligns with that reported by Chen [3] regarding the promoter regions of the CDPK gene family in perennial ryegrass. Given the established role of CDPK-mediated SA signal transduction in immune regulation during plant-pathogen interactions [43], CDPK genes may contribute to resistance by modulating hormone signaling pathways.

In the context of plant disease resistance responses, disparities in gene expression represent a significant molecular basis for variation in resistance among different cultivars. In this study, PyCDPK19 exhibited opposite expression trends in the scab disease-resistant cultivar ‘Huangguang’ and susceptible cultivar ‘Xuehua.’ This suggests that it may play a key role in pear scab disease resistance response. After stress exposure, there is a significant increase in the production of ROS, which disrupts cellular homeostasis and triggers antioxidant defenses to mitigate the harmful effects of oxidative stress [51]. As demonstrated in the literature, transient expression of CaCDPK15 in pepper leaves induces a hypersensitive response, enhances electrical conductivity, and promotes H2O2 accumulation. Concurrently, the expression levels of defense-related genes also increase [52]. This phenomenon has also been observed in potatoes [53]. In grape leaves, transient VaMAPKKK15 expression has been observed to increase MDA and H2O2 levels, resulting in severe cellular structural damage and reduced cold tolerance [48]. This study found that transient overexpression of PyCDPK19 induced hypersensitivity in tobacco leaves, accompanied by cell necrosis, with significant increases in H2O2 and MDA levels in the necrotic areas. This finding is consistent with the results obtained by Pan in their study of BnaCPK6L in rapeseed [54]. They observed that the transient expression of BnaCPK6L in tobacco leaves resulted in the accumulation of ROS and hypersensitive cell death. It has been hypothesized that PyCDPK19 may enhance resistance to pathogens by triggering plant hypersensitivity reactions.

5. Conclusions

This study integrated the genomes of five cultivated pear species (P.bretschneideri, P. ussuriensis, P. sinkiangensis, P. pyrifolia, and P. communis), along with the wild species P. betulifolia and two interspecific hybrids, totaling eight pear genomes. This established a foundational resource repository for pan-genomic analysis of pear. Through systematic investigation, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the pear CDPK gene family and examined its member counts, physicochemical properties, collinearity relationships, selective pressures, and cis-acting elements. By integrating the transcriptome data, we identified PyCDPK19 as a key gene closely associated with scab resistance in pear. Functional validation showed that PyCDPK19 activates defense responses via the ROS pathway in both tobacco and pear, revealing a key response mechanism by which the pear CDPK gene family responds to scab and provides a novel target for pear scab research. To our knowledge, this study represents the first systematic pan-genomic identification and functional characterization of the CDPK gene family, providing novel targets and theoretical support for molecular breeding of pear scab resistance.

Author Contributions

X.H.: writing—original draft, data analysis, formal analysis. Y.L.: data analysis, investigation. Z.Y.: writing—review and editing. T.L.: data analysis, investigation. Y.S.: writing—review and editing. X.H. and L.L.: conceived and designed the experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Biotech Breeding Engineering Project (grant number YZGC109) and the Shanxi Province Science and Technology Major Special Project (grant number 202201140601027-2).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. The RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under BioProject accession number PRJNA1328202.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, F.; Xi, M.; Liu, T.; Wu, X.; Ju, L.; Wang, D. The Central Role of Transcription Factors in Bridging Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses for Plants’ Resilience. New Crops 2024, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmonte-Cortes, G.R.; Higgins, C.M.; MacDiarmid, R.M. Arabidopsis Calcium Dependent Protein Kinase 3, and Its Orthologues Oscpk1, Oscpk15, and Accpk16, Are Involved in Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2025, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xie, Y.; Pan, S.; Yu, S.; Zhang, L. Identification of Perennial Ryegrass Cdpk Gene Family and Function Exploration of Lpcdpk27 Upon Salt Stress. Grass Res. 2025, 5, e009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liang, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, A. Identification of Cdpk Gene Family in Solanum Habrochaites and Its Function Analysis under Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Lin, D.; Ma, S.; Wang, C.; Lin, S. Genome-Wide Identification of the Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase Gene Family in Fragaria Vesca and Expression Analysis under Different Biotic Stresses. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 164, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Chai, M.; Huang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cai, H.; Qin, Y. Genome-Wide Investigation of Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase Gene Family in Pineapple: Evolution and Expression Profiles During Development and Stress. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, K.V.; Dubrovina, A.S. The Role of Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase (Cdpk) Genes in Plant Stress Resistance and Secondary Metabolism Regulation. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Khan, A.; Kumar, S.; Allan, A.C.; Lin-Wang, K.; Espley, R.V.; Wang, C.; Wang, R. Pear Genetics: Recent Advances, New Prospects, and a Roadmap for the Future. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, B.; Barandan, A.; Tymoszuk, A.; Kulus, D. Optimization of in Vitro Propagation of Pear (Pyrus communis L.)‘Pyrodwarf®(S)’Rootstock. Agronomy 2023, 13, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Duan, S.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, L.; Han, Z.; Wu, T. Pan-Genome Analysis of 13 Malus Accessions Reveals Structural and Sequence Variations Associated with Fruit Traits. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Jones, D.; Thrimawithana, A.H.; Deng, C.H.; Bowen, J.K.; Mesarich, C.H.; Ishii, H.; Won, K.; Bus, V.G.; Plummer, K.M. Whole Genome Sequence Resource of the Asian Pear Scab Pathogen Venturia Nashicola. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2019, 32, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, P.; Song, Y.; Li, L. Reactive Oxygen Species and Salicylic Acid Mediate the Responses of Pear to Venturia Nashicola Infection. Agronomy 2024, 14, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, K.; Choi, E.D.; Kim, K.; Jung, H.W.; Shin, I.S.; Hong, S.; Segonzac, C.; Kim, Y.J. An Alternative Method to Evaluate Resistance to Pear Scab (Venturia Nashicola). Plant Pathol. J. 2023, 39, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, M.; Kumar, S.; Qin, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Qi, K.; Zhang, S.; Chang, W.; Li, J. Genomic Selection of Eight Fruit Traits in Pear. Hortic. Plant J. 2024, 10, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Korban, S.S.; Fei, Z.; Tao, S.; Ming, R.; Tai, S.; Khan, A.M.; Postman, J.D. Diversification and Independent Domestication of Asian and European Pears. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ming, R.; Zhu, S.; Khan, M.A.; Tao, S.; Korban, S.S.; Wang, H. The Genome of the Pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). Genome Res. 2013, 23, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, M.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, S. A De Novo Genome Assembly of the Dwarfing Pear Rootstock Zhongai 1. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, D.; Huo, H.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Liao, R.; Shi, M. De Novo Assembly of a Wild Pear (Pyrus betuleafolia) Genome. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, J.; Li, N.; Zhou, P.; Li, L. Genome-Wide Identification of Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinases (Cdpks) in Pear (Pyrus Bretschneideri Rehd) and Characterization of Their Responses to Venturia Nashicola Infection. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2022, 63, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Luo, H.; Xu, J.; Cruickshank, A.; Zhao, X.; Teng, F.; Hathorn, A.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Shatte, T. Extensive Variation within the Pan-Genome of Cultivated and Wild Sorghum. Nature Plants. 2021, 7, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qian, Y.-Q.; Zhao, R.-P.; Chen, L.-L.; Song, J.-M. Graph-Based Pan-Genomes: Increased Opportunities in Plant Genomics. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, L. Responses of Intracellular Ca2+ and Its Sensors to Venturia Nashicola Infection in Pear (Pyrus bretschneideri) with Differing Resistance. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 243, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Yu, O.; Dai, W.; Fang, C. Transcriptome Profiling of Fruit Development and Maturation in Chinese White Pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd). BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Huang, X.-S. Deep Sequencing-Based Characterization of Transcriptome of Pyrus Ussuriensis in Response to Cold Stress. Gene 2018, 661, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, C.; Liu, R.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, J. Chromosome-Level Genome Provides New Insight into the Overwintering Process of Korla Pear (Pyrus sinkiangensis Yu). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; Shi, H. Genome-Wide Identification and Molecular Characterization of the Mapk Family Members in Sand Pear (Pyrus pyrifolia). BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsmith, G.; Rombauts, S.; Montanari, S.; Deng, C.H.; Celton, J.-M.; Guérif, P.; Liu, C.; Lohaus, R.; Zurn, J.D.; Cestaro, A. Pseudo-Chromosome–Length Genome Assembly of a Double Haploid “Bartlett” Pear (Pyrus communis L.). Gigascience. 2019, 8, giz138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. Smart: Recent Updates, New Developments and Status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. Fasttree 2–Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (Itol) V5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex Heatmaps Reveal Patterns and Correlations in Multidimensional Genomic Data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y. Tbtools-Ii: A “One for All, All for One” Bioinformatics Platform for Biological Big-Data Mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. Kaks_Calculator 2.0: A Toolkit Incorporating Gamma-Series Methods and Sliding Window Strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C.O.; Wilke, M.C.O. Package “Ggridges”. Ridgeline Plots in “ggplot2. 2022. Available online: https://wilkelab.org/ggridges/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Wickham, M.H. Package ‘Ggplot2’. Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. 2016. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/reference/ggplot2-package.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One Fastq Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, I884–I890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-Based Genome Alignment and Genotyping with Hisat2 and Hisat-Genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, G.H.; Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Pimanda, J.E.; Zanini, F. Analysing High-Throughput Sequencing Data in Python with Htseq 2.0. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2943–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletich, G.; Gavrilenko, I.; Pushin, A.; Chelombit, S.; Khmelnitskaya, T.; Plugatar, Y.; Dolgov, S.; Khvatkov, P. Somatic Embryogenesis and Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation in a Number of Grape Cultivars. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2025, 160, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Q.-c.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Gao, S.-J.; Gao, Z.-C.; Peng, Z.-P.; Cui, J.-H. Pan-Genome Analysis and Expression Verification of the Maize Arf Gene Family. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1506853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Hui, D.B.; Li, Y.X.; Ren, Q.R.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, J.L.; Hu, H.F. Research Progress and Prospects on Crop Pan-Genomics. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2025, 58, 2045–2061. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, C.A.; Michael, T.P.; McCabe, P.F.; Schilling, S.; Melzer, R. Ft-Like Genes in Cannabis and Hops: Sex Specific Expression and Copy-Number Variation May Explain Flowering Time Variation. bioRxiv 2024, 10.04.616617. [Google Scholar]

- Goher, F.; Khan, F.S.; Sun, S.; Wang, Q. Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase (Cdpk/Cpk)-Mediated Salicylic Acid Cascade: The Key Arsenal of Plants under Pathogens Attack. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2025, online ahead of print, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, K.; Rao, M.J.; Sadaqat, M.; Azeem, F.; Fatima, K.; Qamar, M.T.U.; Alshammari, A.; Alharbi, M. Pangenome-Wide Analysis of Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Channel (Cngc) Gene Family in Citrus Spp. Revealed Their Intraspecies Diversity and Potential Roles in Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1034921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Cai, D.; Potter, D.; Postman, J.; Liu, J.; Teng, Y. Phylogeny and Evolutionary Histories of Pyrus L. Revealed by Phylogenetic Trees and Networks Based on Data from Multiple DNA Sequences. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2014, 80, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zheng, X.; Yu, P.; Yue, X.; Ahmed, M.; Cai, D.; Teng, Y. Primitive Genepools of Asian Pears and Their Complex Hybrid Origins Inferred from Fluorescent Sequence-Specific Amplification Polymorphism (Ssap) Markers Based on Ltr Retrotransposons. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149192. [Google Scholar]

- Yuanwen Teng, Y.; Tanabe, K.; Tamura, F.; Itai, A. Genetic Relationships of Pear Cultivars in Xinjiang, China, as Measured by Rapd Markers. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2001, 76, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, M.; Lu, S.; Shao, M.; Liang, G.; Mao, J. Identification of the Grape Mapkkk Gene Family and Functional Analysis of the Vamapkkk15 Gene under Low Temperature Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 220, 109533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Ji, X.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Meng, L.; Wei, P.; Xu, H.; Niu, T.; Liu, A. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the Dof Gene Family Reveals Their Involvement in Hormone Response and Abiotic Stresses in Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Gene 2024, 910, 148336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Li, J.-Y.; Yu, Z.-F.; Chang, X.-Y.; Han, J.-R.; Xia, J.-Y.; Kami, Y.B.; Sun, Y.-T.; Li, L.; Wang, S.-T. Comparative Genomic Analysis Reveals the Difference of Nlr Immune Receptors between Anthracnose-Resistant and Susceptible Sorghum Cultivars. Phytopathol. Res. 2025, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Xiong, L.; Shi, H.; Yang, S.; Herrera-Estrella, L.R.; Xu, G.; Chao, D.-Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.-Y.; Qin, F. Plant Abiotic Stress Response and Nutrient Use Efficiency. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Yang, S.; Yang, T.; Liang, J.; Cheng, W.; Wen, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, L.; Tang, Q. Cacdpk15 Positively Regulates Pepper Responses to Ralstonia Solanacearum Inoculation and Forms a Positive-Feedback Loop with Cawrky40 to Amplify Defense Signaling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Yoshioka, M.; Asai, S.; Nomura, H.; Kuchimura, K.; Mori, H.; Doke, N.; Yoshioka, H. Stcdpk5 Confers Resistance to Late Blight Pathogen but Increases Susceptibility to Early Blight Pathogen in Potato Via Reactive Oxygen Species Burst. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Gao, S.; Yang, B.; Jiang, Y.-Q. Rapeseed Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase Cpk6l Modulates Reactive Oxygen Species and Cell Death through Interacting and Phosphorylating Rbohd. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 518, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).