Abstract

The Mediterranean Basin’s diverse climates and ecosystems have shaped a rich botanical heritage through centuries of selective cultivation, resulting in a wide array of horticultural plants with valuable therapeutic properties. The use of horticultural food plants as herbal remedies has become an integral part of traditional medicine in this geographical context. The present review aims to highlight the use of horticultural food plants (HFPs) in the context of traditional herbal medicine in the countries of the Mediterranean Basin and explore their traditional uses and therapeutic properties. A comprehensive ethnobotanical literature search was conducted on the food plants used as herbal medicine in the Mediterranean region using existing online scientific databases. Based on the literature review, 64 taxa used as medicinal plants by traditional users in the Mediterranean Basin were documented. Overall, horticultural plants are used in Mediterranean countries to treat a total of 573 ailments. Italy has the highest number of use reports (998), followed by Morocco (281) and Spain (193). Apiaceae (11 taxa), Cucurbitaceae (9 taxa), and Brassicaceae (8 taxa) are the most frequently cited families. The genus Allium is the most abundant in species (5).

1. Introduction

Throughout human history, plants have played a fundamental role in various aspects of human existence [1]. Numerous studies have shown that plants can play a dual role, acting simultaneously as medicine and food, as demonstrated by their specific pharmacological effects, which have been emphasized in research on traditional foods [2,3]. As humans evolved from hunter–gatherers to breeders and farmers, they began to cultivate plants for their various needs, and, through the process of domestication, these plants were genetically improved, leading to a gradual but remarkable improvement in their properties [4]. The choice to use traditional medicine and herbal therapies is often driven by geographical and socio-economic factors, especially when access to modern treatments is inadequate and the cost of most conventional medicines is high [5]. In this context, hundreds of wild and cultivated plant species, which constitute an important natural resource in indigenous medicine, are mainly used in herbal preparations. These preparations include effective medicines that have withstood the test of time and often cannot be replaced by modern medicinal alternatives [6,7]. In recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in medicinal plants, with numerous species being studied for their pharmacological activities and contributing to advances in drug discovery [8].

Throughout the millennia, the Mediterranean region has witnessed the convergence of diverse cultures, each leaving a significant imprint on the study and utilization of plants. Today, this rich botanical heritage faces threats from globalization, making the preservation of traditional knowledge paramount. Despite these challenges, many Mediterranean communities, particularly in remote areas, continue to rely on wild plants for various purposes, highlighting the enduring significance of ethnobotanical practices in the region [9,10,11,12]. The Mediterranean Basin, with its diverse climates and ecosystems, is home to a rich botanical heritage that has been shaped by centuries of selective cultivation and breeding. This unique environment has led to the cultivation of a wide variety of horticultural plants, many of which have valuable therapeutic properties. The cultural diversity within the Mediterranean Basin, resulting from a complex history of regional and local traditions, enriches herbal knowledge, with each country contributing its own practices and sometimes unique remedies [13,14]. The typical daily Mediterranean diet, known for its emphasis on vegetables, fruits, and spices, often includes both cultivated and wild food species, as their medicinal properties enrich the health qualities of the diet [15,16,17].

Horticultural plants are grown and cultivated for decorative purposes, landscaping, and gardening, as well as for the production of edible parts which are an important part of the human diet (HFPs).The use of horticultural food plants as herbal remedies has become, over time, an integral part of traditional medicine in various cultures around the world (e.g., [18,19,20]). However, the extensive European ethnobotanical literature has mainly focused on the therapeutic use of wild plants, giving little space to cultivated species (e.g., [21,22,23]).

In this context, we reviewed the available literature to thoroughly investigate the role of horticultural food plants in the context of traditional herbal medicine in the Mediterranean region and explore their traditional uses and therapeutic properties. Finally, a comparison was made between the use of different species for the treatment of health disorders in Mediterranean countries.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive ethnobotanical literature search was conducted on the food plants used as herbal medicine in the Mediterranean region using existing online scientific databases, such as Web of Science, Scopus, and Science Direct, as well as Google Scholar. The following keywords and connectors were used: “country” AND “ethnobotanical” OR “ethnobotany”, OR “ethnopharmacological” OR “ethnopharmacology”. Publications were filtered by document type (peer-reviewed articles only), duplicates, and full-text availability; our search strategy was not bound by chronological limits. The abstracts of the articles selected in the previous step were thoroughly screened to determine the actual relevance of the review articles and exclude inapplicable studies. Only articles that contained specific references to the use of horticultural food plants as herbal remedies were considered. The selected articles were read and evaluated in their entirety. Finally, through an extensive evaluation of the documents cited in the “References” of the selected articles, we were able to collect additional articles on the ethnobotany of horticultural plants.

A total of 394 articles from 17 countries were found in the databases, of which 150 contained reports on the use of plants (Table 1). No data on the therapeutic use of horticultural species were available for France, Malta, Syria, and Montenegro. Only herbaceous horticultural plants used as vegetables, greens, or herbs were considered. Species that are used both wild and cultivated (e.g., Foeniculum vulgare) were only included if their cultivated status was indicated. The nomenclature followed the World Flora Online [24]. Families were arranged according to APG IV for angiosperms [25]. The authors’ abbreviations were standardized according to Brummitt and Powell [26], as recommended by Rivera et al. [27]. Based on the results obtained, we created a database with the following data: taxon (when helpful due to recent changes in nomenclature, synonyms are given in square brackets), family, parts used, preparation, administration, recorded use, and references. We used a symptom-based nosological approach commonly used in ethnobotanical research to classify plant-treated diseases, as described in the consulted literature [28,29,30].

Table 1.

References researched in the Mediterranean region.

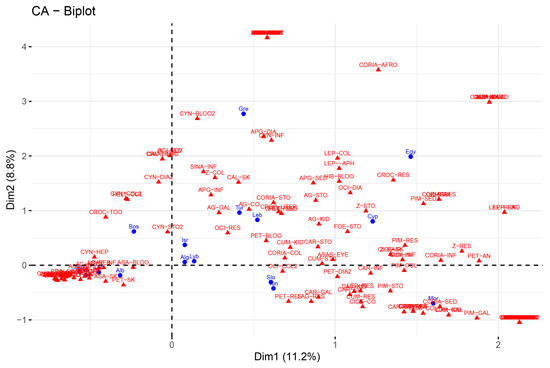

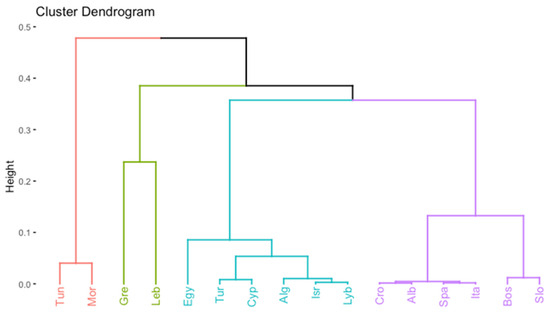

In order to analyze and understand the relationship between the types of plants used for certain medicinal purposes and the different nations under consideration, we performed a simple correspondence analysis (CA). A correspondence analysis is a statistical technique for examining the relationships between the rows and columns of a table of categorical data. We created a frequency table in which the rows represented the types of use of plants in the medical field and the columns the countries considered. This correspondence analysis made it possible to identify significant associations between specific plants and specific countries, as well as common patterns of use or significant differences in traditional medical practice between different countries. The results of the correspondence analysis were then used for a hierarchical cluster analysis to identify groups of countries with similar patterns of medicinal plant use. Hierarchical clustering builds a hierarchy of clusters, where each object first represents a single cluster and is then combined with other clusters based on its similarity. During the clustering process, the internal variability in each cluster is minimized, and the external variability between clusters is maximized. Minimizing the internal variance helps to ensure that the clusters are homogeneous and that the objects within each cluster have common characteristics, as is the case with the usage patterns of medicinal plants. In hierarchical clustering, different distance measures can be used to evaluate the similarity between objects during the clustering process; in this context, we used Euclidean distance. The statistical analysis was performed with the freely available software R, a software for statistical calculations and graphics (https://www.r-project.org/ accessed on 18 March 2024). In this study, various R packages were used for data import, manipulation, and analysis. The ‘readxl’ package imported Excel files efficiently, while ‘readr’ enabled the fast reading of large CSV files. For the data analysis, ‘FactoMineR’ was employed for multivariate analyses, such as correspondence analysis (CA), with ‘factoextra’ used to visualize and interpret the results. Data manipulation was primarily handled by ‘dplyr’, part of the ‘tidyverse’ suite, which also includes ‘ggplot2’ for data visualization, ensuring a consistent and reproducible workflow.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Data

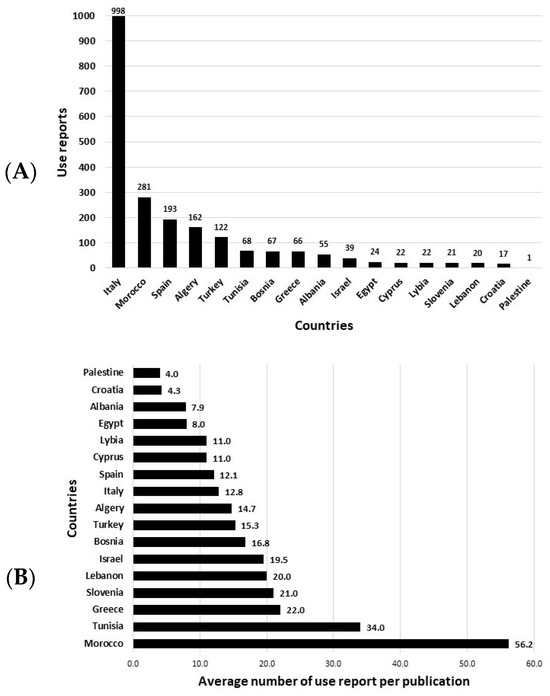

Based on the literature search, 64 taxa were documented as being used as medicinal plants by traditional users in the Mediterranean Basin (Table 1). In addition, horticultural plants were shown to be used in Mediterranean countries to treat a total of 573 ailments, as shown in the literature reviewed. Considering the number of reports on the use of each species to treat different ailments in all the countries studied, the total number was 2177. Italy had the highest number of use reports (998), followed by Morocco (281) and Spain (193) (Figure 1A), while Morocco had the highest average number of use reports per publication (56.2), followed by Tunisia (34.0) and Greece (22.0) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Use reports per country (A) and average number of use reports per publication per country (B).

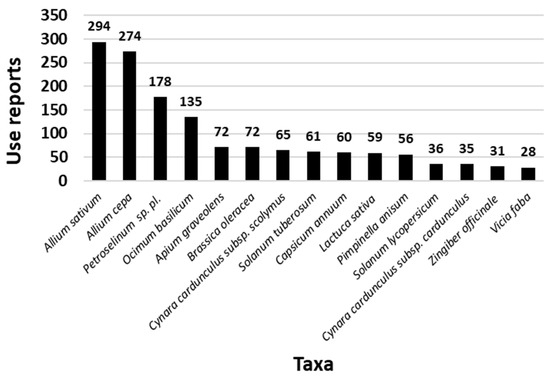

The cited taxa belonged to 15 families and 45 genera. Apiaceae (11 taxa), Cucurbitaceae (9 taxa), Brassicaceae (8 taxa), Asteraceae (7 taxa), and Fabaceae (6 taxa) were the most frequently cited families. The genus Allium was the most abundant in terms of number of species (five), followed by Brassica, Cucurbita, and Solanum (three each). Allium sativum and A. cepa were the most cited species, followed by the Petroselinum spp. and Ocimum basilicum (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of use reports for each taxa (the top 15 most cited taxa are reported here).

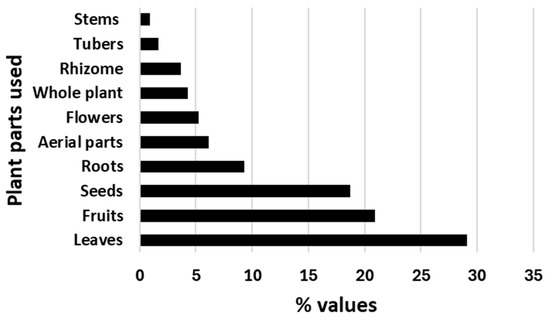

Leaves (29.1%) were the most frequently used plant parts, followed by fruits (20.9%) and seeds (18.7%). The remaining parts accounted for a total of 31.2% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of use of plant parts in the studied countries.

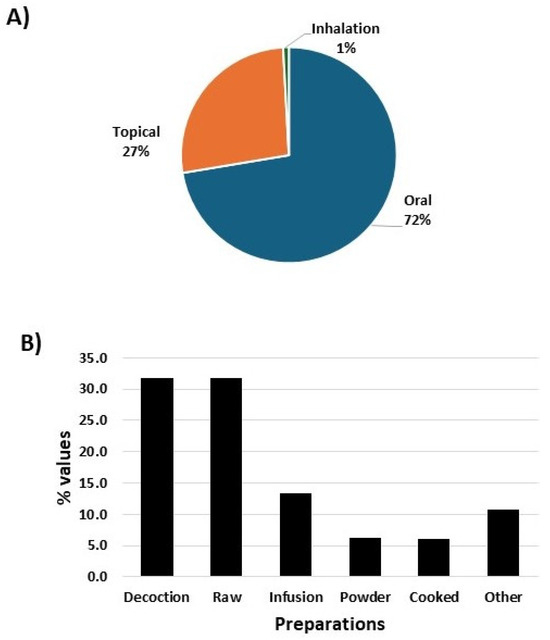

The most important routes of administration were oral (72%) and topical (27%), while inhalation was rarely reported (Figure 4A). Decoction (31.8%) and raw/fresh (31.7%) were the most important preparation methods, followed by infusion (13.3%), powder (6.2%), and cooking (6.1%) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Administration (A) and preparation (B) methods of horticultural plants for ailment treatment in countries of the Mediterranean Basin.

3.2. Phytotherapeutic Applications

Table 2 and Table 3 show the extensive use of horticultural food plants for medicinal purposes in Mediterranean Basin countries, covering a wide range of health issues.

Table 2.

Percentage of use reports for the nosological categories (in brackets is the total number of citations).

Table 3.

Number of citations of the specific uses for each of the most representative plant species. Plant species (in columns) with more than 30 citations have been selected and reported in descending order (from left to right). The categories of use at the level of the system (rows) are also reported in descending order in relation to the number of occurrences (from top to bottom).

The species most commonly used for various health conditions are described below. The references are shown in Table S1.

- Gastrointestinal System

The large number of reports on the use of gastrointestinal remedies suggests that horticultural plants play an important role in traditional folk medicine in the treatment of digestive problems and the maintenance of intestinal health, with anthelmintics and liver diseases also accounting for a significant proportion. The diversity of herbal remedies for gastrointestinal complaints indicates a rich knowledge base within the community for the treatment of such problems. Thirteen plant species are commonly used for their digestive properties and are administered in different ways. For example, the seeds of Cucumis melo, Cucurbita pepo, and Daucus carota can be eaten raw or used to prepare decoctions. The leaves of Beta vulgaris, the roots of Raphanus sativus, and the fruits of Capsicum annuum can be eaten either raw or after cooking due to their digestive effect. Digestive decoctions can also be made from the pistils of Crocus sativus, the leaves of Lactuca sativa, and the bracts of Cynara cardunculus subsp. cardunculus. Stomach pains and hyperacidity are usually treated with a decoction of the leaves of Ocimum basilicum, the fruits of Petroselinum spp., or a decoction of the bulbs of Allium cepa and A. sativum. Carrots, radishes, and broad beans are eaten to treat diarrhea. Both cholagogue and choleretic plants are used in traditional and alternative medicine to support the health of the digestive system and treat ailments related to the production and flow of bile. The most commonly reported plants for this purpose are Cynara cardunculus (bracts and leaves for infusions), Petroselinum spp. (aerial parts for raw consumption), and Solanum melongena (fruits for decoctions). The most commonly reported anthelmintic is garlic (Allium sativum), which is taken orally, raw, or as a decoction and, sometimes, even inhaled. The seeds of some species of the cucurbit family (Cucurbitaceae) are also consumed as anthelmintics (Cucumis sativus, Cucurbita maxima, C. moschata, and C. pepo). For some species (e.g., Cicer arietinum, Petroselinum spp., and Allium schoenoprasum), regional use as an anthelmintic has been identified.

- Integumentary System

As far as the integumentary system is concerned, horticultural species are mainly used to treat skin diseases but also contribute to the treatment of hair diseases. This emphasizes the importance of these plants in the treatment of dermatological problems, wound care, and the improvement of skin and hair health in traditional medical practice. Many of the species mentioned are used to locally soothe and heal burns, including the raw leaves of Apium graveolens, the cooked leaves of Beta vulgaris, the raw fruits of Cucumis sativus and Cucurbita pepo, and the raw roots of Daucus carota. For minor skin inflammations such as pimples or larger inflammations with pus, boiled leaves of Brassica oleracea are applied to the affected area, while, for mastitis and rhagades, roasted leaves of the same species are applied topically. Raw bulbs of Allium sativum, raw leaves of Petroselinum spp., or, as a decoction, raw fruits of Solanum lycopersicum or slices of raw tubers of Solanum tuberosum are used to relieve the itching of insect bites. A poultice made from the raw roots of Raphanus sativus subsp. sativus is not used to improve the condition of facial skin but to remove spots on the face, fade freckles, and reduce the effects of oily skin. The most commonly cited species is Allium cepa, which is also used for digestive complaints. Raw onion bulbs without the outer bracts are used for burns, wound healing, insect bites, and also hair loss. Alternatively, the scales of the onion fried in oil are applied to blisters, pimples, etc., to speed up healing and heal purulent skin abscesses caused by thorns.

- Cardiovascular System

The presence of horticultural herbal remedies for cardiovascular health is noteworthy, as it reflects the potential of these plants to play a role in traditional medicine in supporting heart health and treating related problems. Horticultural species used to treat hypertension include various plants and herbs that have potential medicinal properties. Decoctions or macerates from the bulbs of Allium sativum and A. cepa are widely known as a means of lowering blood pressure. In addition, the fruits of Capsicum annuum and the juice from the leaves of Lactuca sativa are used to treat high blood pressure. Allium and Petroselinum species are also eaten raw to lower cholesterol levels.

- Respiratory System

The use of garden plants for the respiratory system is another interesting finding. From the use reports, it appears that certain plants are considered effective for treating respiratory ailments, which could be helpful in traditional herbal medicine for treating ailments such as coughs, colds, and other respiratory ailments. Among these plants, the species Allium cepa and A. sativum are often mentioned for the treatment of respiratory diseases. The bulbs are used raw or to make decoctions or tinctures. A decoction made from the leaves of Lactuca sativa appears to be effective in treating some respiratory symptoms.

- Urinary System

Plants used for problems with the urinary tract are mainly used as diuretics or to treat and prevent kidney stones. The most commonly cited remedies for the treatment of urinary tract disorders include the raw consumption of Apium graveolens stems and the decoction of Asparagus officinalis roots and Petroselinum spp. outer parts.

- Musculoskeletal System

The use of HFPs in folk phytotherapy for the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders is mainly due to the therapeutic potential of these plants, which often have anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and muscle-relaxing properties. The species most frequently mentioned in this context is Brassica oleracea, whose leaves, roasted or boiled, are used externally to treat rheumatism, bruises, joint pain, and tendonitis. Tinctures or macerates made from the fruits of Capsicum annuum, the leaves of Petroselinum spp., or the bulbs of Allium sativum are used externally to treat rheumatisms.

- Endocrine System

Reports on the use of HFPs for hormonal and metabolic imbalances in traditional folk medicine indicate their use for the endocrine system. In this regard, lactation and diabetes are the main categories for which these plants are used. The bulbs of Allium cepa, whether raw or cooked, are the main parts of the plant used as a galactagogue. The leaves and fruits of Ocimum basilicum, Anethum graveolens, Beta vulgaris, and Petroselinum spp. are also used for the same purpose. The fruits of Lupinus albus are used as a remedy for type 2 diabetes. Raw bulbs of Allium cepa and a decoction of the bracts and leaves of Cynara cardunculus subsp. cardunculus are used for the same metabolic disorder.

- Nervous System

The medicinal properties of these plants, which have a calming effect and relieve headaches, are also used to treat disorders of the nervous system. A decoction of the leaves of Ocimum basilicum is often used as a sedative, while slices of the tubers of Solanum tuberosum are placed on the forehead to relieve headaches.

Other uses include fighting fevers, treating alcoholism, and treating sensory system problems such as eye and ear conditions. Garden plants also have antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, contribute to dental health, and serve as a remedy for various ailments that do not fall into other categories.

3.3. Geographical and Botanical Distribution Data

The results of the correspondence analysis (Figure 5) and clustering (Figure 6) show four different clusters of nations, each characterized by specific patterns of plant use. For each cluster, the plants and the type of use that most strongly characterize the cluster are indicated.

Figure 5.

Representation of the factorial map of the two variables under study: use of plants and nations.

Figure 6.

Dendrogram: cluster analysis to determine the characterizations of different uses of plants in various countries.

In the purple cluster represented by six countries from the north-western to the eastern Mediterranean (Spain, Italy, Croatia, Albania, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina), we observe the use of different medicinal plants with specific applications:

Allium cepa, Solanum lycopersicum, and S. tuberosum are used to treat skin diseases;

Allium sativum is used as an anthelmintic and for the treatment of diabetes and skin diseases;

Anethum graveolens is used for the treatment of kidney diseases;

Brassica oleracea is used for the treatment of skin diseases;

Coriandrum sativum is used to treat intestinal complaints;

Ocimum basilicum is used as a galactagogue;

Petroselinum spp. is used to induce miscarriages.

This characterization indicates a wide range of medicinal plant uses within the group, with particular emphasis on the treatment of skin diseases and intestinal disorders, as well as specific uses as an anthelmintic or abortifacient substance and for the treatment of diabetes and kidney disease.

In green group 2, represented by Greece and Lebanon, a specific use of some medicinal plants can be observed:

Cynara cardunculus subsp. scolymus is used to regulate blood pressure, lower cholesterol, and treat diabetes;

Sinapis alba is used for respiratory diseases.

This characterization underlines the specific use of these medicinal plants within the group, with a focus on the treatment of respiratory diseases and the regulation of blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes.

In red group 3, represented by Tunisia and Morocco, we observe an interesting concentration in the use of various medicinal plants for the treatment of musculoskeletal inflammation:

Sesamum indicum, Raphanus sativus subsp. sativus, Pimpinella anisum, Lupinus albus, Ocimum basilicum, Cucumis sativus, and Capsicum annuum are used for skeletal muscle inflammation.

This characterization shows a tendency in the group towards the use of medicinal plants for the specific treatment of inflammation of the musculoskeletal system.

In group 4, in a blue color, which is represented by six countries in the south-eastern Mediterranean (Egypt, Turkey, Cyprus, Algeria, Israel, and Libya), a broad use of various medicinal plants for the treatment of a range of diseases can be observed:

Sesamum indicum is used for skin and respiratory diseases;

Brassica rapa is used for respiratory diseases;

Foeniculum vulgare is used to treat cholesterol;

Petroselinum spp. is used as a galactagogue;

Lepidium sativum is used for stomach and intestinal complaints;

Anethum graveolens and Cucumis sativus are used for stomach complaints;

Asparagus officinalis is used as an anti-inflammatory for muscles, diabetes, and gut health;

Apium graveolens is used as a sedative;

Beta vulgaris is used to treat anemia;

Coriandrum sativum is used for intestinal complaints.

This cluster shows a wide range of medicinal plants used to treat a variety of conditions, with a focus on gut health, stomach and respiratory problems, and the treatment of cholesterol and anemia.

The identified clusters indicate different regional preferences and traditions in the use of medicinal plants and reflect differences in the health practices and cultural influences between nations. In summary, our analysis clarifies the relationship between types of medicinal plants and nations and reveals different patterns of plant use in different geographical regions.

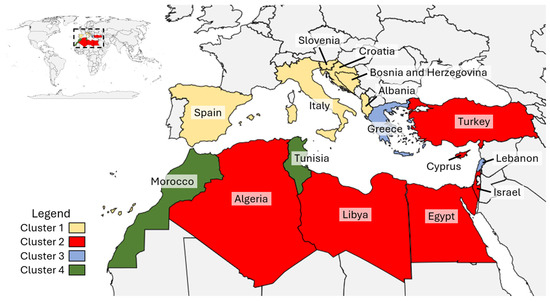

This clustering approach also provides an overview of the geographical and possible cultural relationships between the countries and enables meaningful grouping based on geographical proximity and cultural similarities (Figure 7). In particular, cluster 1 groups together countries that share a common geographical location in Southern Europe and cultural similarities based on their Mediterranean heritage and historical interactions. Clusters 3 and 4 group northeastern and North African countries that share some cultural similarities beyond their geographic location, including aspects of Arab (except Israel) and Mediterranean influences. Cluster 2 is clearly characterized by the use of certain plants against certain diseases.

Figure 7.

Geographical distribution of clusters.

3.4. Economic Botanical Value and Effective Possibilities of Use

The studies we included in this review show that horticultural food plants (HFPs) are used in all Mediterranean countries not only for human consumption but also for therapeutic purposes. Their use is often closely linked to local climatic conditions and traditional knowledge. Edible plants are referred to as functional foods due to their nutraceutical and therapeutic properties that go beyond their simple nutritional function [31,32]. Moreover, thanks to their vitamin and antioxidant content, these plants can play an important role in promoting health and preventing various diseases [33,34,35]. The use of HFPs in traditional medicine offers several advantages. For example, cultivated plants are often more readily available and more consistent in quality and quantity than wild-harvested plants. This reliability is important for traditional healers or individual consumers who need a constant supply of plant materials. In addition, HFPs are often accessible to larger populations, making traditional remedies based on these plants more available to those in need. The cultivation of HFPs enables the transmission of knowledge and practices related to their use from one generation to the next. This intergenerational transmission of knowledge is crucial for the preservation of traditional medicine. From an economic perspective, cultivated plants can be better suited for pharmacological research and the standardization of active ingredients, making them more attractive to modern health systems and research. In addition, HFPs can be subjected to quality control to ensure that no impurities are present and that their medicinal properties are maintained, which is often more difficult with wild, harvested plants. In this context, HFPs can either serve as a beneficial economic alternative to traditional horticulture or an integral part of it. In addition, the cultivation of horticultural food crops as herbal remedies can provide a sustainable socio-economic opportunity, especially for farmers in regions with less-than-optimal growing conditions or in areas where traditional horticulture does not provide sufficient income. Overall, the economic benefits of growing HFPs as herbal remedies could make it an attractive option for individuals and companies looking to diversify their agricultural activities and benefit from emerging markets for herbal medicines, which could also help stabilize populations in rural areas. The present research highlights the diverse strengths of utilizing horticultural food plants (HFPs) in traditional medicine, including their role in preserving cultural knowledge, accessibility, and economic viability. However, potential weaknesses such as the risk of biodiversity loss, dependency on specific plant species, and environmental impact need to be carefully addressed to ensure the sustainability of these practices and their benefits for both health and society.

4. Conclusions

In summary, these results demonstrate the diverse use of garden plants in folk phytotherapy and illustrate their role in the treatment of a wide range of health problems in different body systems in Mediterranean countries. The role of ethnobotanical studies is to avoid the loss of traditional knowledge about the use of food plants and, at the same time, provide the basis for the discovery of new medicines through phytochemical and biochemical research. By integrating traditional knowledge with modern scientific approaches, there is significant potential to discover novel therapies and enhance the understanding of the therapeutic uses of garden plants, thereby contributing to both cultural preservation and medical advancements. In this respect, new field studies in the Mediterranean region targeting specific knowledge of horticultural food plants are desirable.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae10070684/s1: Table S1: Horticultural food plants used in the Mediterranean Basin as traditional herbal medicine are listed in a complete table with detailed information from the reviewed articles. References [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M., A.C. and I.V.-K.; methodology, R.M. and M.G.; validation, R.M., A.C. and I.V.-K.; formal analysis, A.D.M. and F.C.; data curation, R.M. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, R.M., A.C. and I.V.-K.; supervision, I.V.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All the relevant data used for this paper can be found in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gerique, A. An Introduction to Ethnoecology and Ethnobotany—Theory and Methods. Design 2006, 102, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Nebel, S.; Quave, C.; Münz, H.; Heinrich, M. Ethnopharmacology of Liakra: Traditional Weedy Vegetables of the Arbëreshë of the Vulture Area in Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor, M.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.; Gillani, S.W.; Shaheen, H.; Pieroni, A.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Elshikh, M.S.; Saqib, S.; Makhkamov, T.; et al. The Local Medicinal Plant Knowledge in Kashmir Western Himalaya: A Way to Foster Ecological Transition via Community-Centred Health Seeking Strategies. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.K. Human Aspects of Plant Diversity. Econ. Bot. 2000, 54, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurib-Fakim, A. Medicinal Plants: Traditions of Yesterday and Drugs of Tomorrow. Mol. Asp. Med. 2006, 27, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šarić-Kundalić, B.; Dobeš, C.; Klatte-Asselmeyer, V.; Saukel, J. Ethnobotanical Study on Medicinal Use of Wild and Cultivated Plants in Middle, South and West Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 131, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motti, R.; Paura, B.; Cozzolino, A.; de Falco, B. Edible Flowers Used in Some Countries of the Mediterranean Basin: An Ethnobotanical Overview. Plants 2022, 11, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baydoun, S.; Chalak, L.; Dalleh, H.; Arnold, N. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in Traditional Medicine by the Communities of Mount Hermon, Lebanon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebel, S.; Heinrich, M. Ta Chòrta: A Comparative Ethnobotanical-Linguistic Study of Wild Food Plants in a Graecanic Area in Calabria, Southern Italy. Econ. Bot. 2009, 63, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savo, V.; Salomone, F.; Bartoli, F.; Caneva, G. When the Local Cuisine Still Incorporates Wild Food Plants: The Unknown Traditions of the Monti Picentini Regional Park (Southern Italy). Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.T.; El Gohary, F.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Angelakis, A.N. Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Kaligarič, M.; Juračak, J. Divergence of Ethnobotanical Knowledge of Slovenians on the Edge of the Mediterranean as a Result of Historical, Geographical and Cultural Drivers. Plants 2021, 10, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonti, M.; Verpoorte, R. Traditional Mediterranean and European Herbal Medicines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 199, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, S.; Heinrich, M.; Leonti, M.; Nebel, S.; Peschel, W.; Pieroni, A.; Smith, F.; Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Inocencio, C.; et al. Understanding Local Mediterranean Diets: A Multidisciplinary Pharmacological and Ethnobotanical Approach. Pharmacol. Res. 2005, 52, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrelli, M.; Statti, G.; Conforti, F. A Review of Biologically Active Natural Products from Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants: Benefits in the Treatment of Obesity and Its Related Disorders. Molecules 2020, 25, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Bonanomi, G.; Lanzotti, V.; Sacchi, R. The Contribution of Wild Edible Plants to the Mediterranean Diet: An Ethnobotanical Case Study Along the Coast of Campania (Southern Italy). Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Heinrich, M.; Inocencio, C.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J. Gathered Mediterranean Food Plants—Ethnobotanical Investigations and Historical Development. Forum Nutr. 2006, 59, 18–74. [Google Scholar]

- Afolayan, A.J.; Grierson, D.S.; Mbeng, W.O. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in the Management of Skin Disorders among the Xhosa Communities of the Amathole District, Eastern Cape, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Cero, M.; Saller, R.; Weckerle, C.S. The Use of the Local Flora in Switzerland: A Comparison of Past and Recent Medicinal Plant Knowledge. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Hodak, A.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Marić, M.; Juračak, J. Traditional Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the Central Lika Region (Continental Croatia)—First Record of Edible Use of Fungus Taphrina Pruni. Plants 2022, 11, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouZid, S.F.; Mohamed, A.A. Survey on Medicinal Plants and Spices Used in Beni-Sueif, Upper Egypt. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. The Ethnobotany and Biogeography of Wild Vegetables in the Adriatic Islands. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motti, R.; Marotta, M.; Bonanomi, G.; Cozzolino, S.; Di Palma, A. Ethnobotanical Documentation of the Uses of Wild and Cultivated Plants in the Ansanto Valley (Avellino Province, Southern Italy). Plants 2023, 12, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WFO World Flora Online. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Chase, M.W.; Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Fay, M.F.; Byng, J.W.; Judd, W.S.; Soltis, D.E.; Mabberley, D.J.; Sennikov, A.N.; Soltis, P.S.; Stevens, P.F.; et al. An Update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group Classification for the Orders and Families of Flowering Plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummitt, P.K.; Powell, C.E. Authors of Plant Names; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.; Allkin, R.; Obon, C.; Alcaraz, F.; Verpoorte, R.; Heinrich, M. What Is in a Name? The Need for Accurate Scientific Nomenclature for Plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 152, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.A.; García-Barriuso, M.; Amich, F. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used in the Arribes Del Duero, Western Spain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 131, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal Plants in Mexico: Healers’ Consensus and Cultural Importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabesh, J.M.; Prabhu, S.; Vijayakumar, S. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Traditional Healers in Silent Valley of Kerala, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, D.M.; Singh, J. A New Definition of Functional Food by FFC: What Makes a New Definition Unique? Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R. Wild Plants Used as Herbs and Spices in Italy: An Ethnobotanical Review. Plants 2021, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Medicinal Plants and Food Medicines in the Folk Traditions of the Upper Lucca Province, Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 70, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sdona, E.; Ekström, S.; Andersson, N.; Hallberg, J.; Rautiainen, S.; Håkansson, N.; Wolk, A.; Kull, I.; Melén, E.; Bergström, A. Fruit, Vegetable and Dietary Antioxidant Intake in School Age, Respiratory Health up to Young Adulthood. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2022, 52, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaglione, P.; Morisco, F.; Caporaso, N.; Fogliano, V. Dietary Antioxidant Compounds and Liver Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarrera, P.; Lucchese, F.; Medori, S. Ethnophytotherapeutical Research in the High Molise Region (Central-Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benarba, B.; Belabid, L.; Righi, K.; Bekkar, A.A.; Elouissi, M.; Khaldi, A.; Hamimed, A. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by Traditional Healers in Mascara (North West of Algeria). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 175, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Pieroni, A. Renegotiating Situativity: Transformations of Local Herbal Knowledge in a Western Alpine Valley during the Past 40 Years. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmese, T.M.; Uncini Manganelli, R.E.; Tomei, P.E. An Ethno-Pharmacobotanical Survey in the Sarrabus District (South-East Sardinia). Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 619–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlidou, E.; Karousou, R.; Kleftoyanni, V.; Kokkini, S. The Herbal Market of Thessaloniki (N Greece) and Its Relation to the Ethnobotanical Tradition. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miara, M.D.; Bendif, H.; Rebbas, K.; Rabah, B.; Hammou, M.A.; Maggi, F. Medicinal Plants and Their Traditional Uses in the Highland Region of Bordj Bou Arreridj (Northeast Algeria). J. Herb. Med. 2019, 16, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, S.; Theilade, I. Local Knowledge of Past and Present Uses of Medicinal Plants in Prespa National Park, Albania. Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menale, B.; De Castro, O.; Cascone, C.; Muoio, R. Ethnobotanical Investigation on Medicinal Plants in the Vesuvio National Park (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 192, 320–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, M.À.; Parada, M.; Selga, A.; Vallès, J. Studies on Pharmaceutical Ethnobotany in the Regions of L’Alt Emporda and Les Guilleries (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 68, 45–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigat, M.; Vallès, J.; Dambrosio, U.; Gras, A.; Iglésias, J.; Garnatje, T. Plants with Topical Uses in the Ripollès District (Pyrenees, Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula): Ethnobotanical Survey and Pharmacological Validation in the Literature. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 164, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Pajazita, Q.; Syla, B.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. An Ethnobotanical Survey of the Gollak Region, Kosovo. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Puricelli, C.; Mikerezi, I.; Iriti, M. Plants, People and Traditions: Ethnobotanical Survey in the Lombard Stelvio National Park and Neighbouring Areas (Central Alps, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, G.; González-Tejero, M.R.; Molero-Mesa, J. Pharmaceutical Ethnobotany in the Western Part of Granada Province (Southern Spain): Ethnopharmacological Synthesis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 129, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballero, M.; Bruni, A.; Sacchetti, G.; Mossa, L.; Poli, F. Indagine Etnofarmacobotanica Del Territorio Di Arzana (Sardegna Orientale). Ann. Bot. 1994, 52, 489–500. [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Molina, M.; Reyes-García, V.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M. Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used in the Northwest of the Basque Country (Biscay and Alava), Iberian Peninsula. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 152, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, E.; Amar, Z. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Traditional Drugs Sold in Israel at the End of the 20th Century. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 72, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, V.; Aquino, R.; Menghini, A.; Ramundo, E.; Senatore, F. Traditional Phytotherapy in the Peninsula Sorrentina, Campania, Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1992, 36, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Motti, P. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Useful Plants in the Agro Nocerino Sarnese (Campania, Southern Italy). Hum. Ecol. 2017, 45, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić-Kundalić, B.; Dobeš, C.; Klatte-Asselmeyer, V.; Saukel, J. Ethnobotanical Survey of Traditionally Used Plants in Human Therapy of East, North and North-East Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 1051–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Forti, G.; Marignoli, S. Ethnobotanical and Ethnomedicinal Uses of Plants in the District of Acquapendente (Latium, Central Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camangi, F.; Stefani, A.; Tomei, P.E. Il Casentino: Tradizioni Etnofarmacobotaniche Nei Comuni Di Poppi e Bibbiena (Arezzo-Toscana). Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat. Mem. 2003, 110, 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Ghedira, K. Comparative Analysis of Medicinal Plants Used in Traditional Medicine in Italy and Tunisia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, G.; Guarrera, P.M. Ricerche Etnobotaniche Nel Parco Nazionale Del Cilento e Vallo Di Diano: Il Territorio Di Castel San Lorenzo (Campania, Salerno). Inf. Bot. Ital. 2008, 40, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Maccioni, S.G.; Flamini, S.G.; Cioni, P.L.; Bedini, G.; Guazzi, E. Ricerche Etnobotaniche in Liguria. La Riviera Spezzina (Liguria Orientale). Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat. Mem. 2008, 115, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mokasabi, F.M.; Al-Sanousi, M.F.; El-Mabrouk, R.M. Taxonomy and Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants in Eastern Region of Libya. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 12, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Said, O.; Khalil, K.; Fulder, S.; Azaizeh, H. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Herbs in Israel, the Golan Heights and the West Bank Region. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellomaria, B. Le Piante Di Uso Popolare Nel Territorio Di Camerino (Marche). Arch. Bot. Biogeogr. Ital. 1982, 58, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J.; Obón, C.; Consuegra, V.; García-Botía, J.; Ríos, S.; Alcaraz, F.; Valdés, A.; del Moral, A.; et al. Ethnopharmacology in the Upper Guadiana River Area (Castile-La Mancha, Spain). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 241, 111968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendif, H.; Souilah, N.; Miara, M.D.; Daoud, N. Medicinal Plants Popularly Used in the Rural Communities of Ben Srour (Southeast of M’sila, Algeria) Presaharan Vegetation: Mapping and Dynamic View Project Presaharan Vegetation (South of Algeria): Mapping and Dynamic View Project. Agrolife Sci. J. 2020, 2, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Passalacqua, N.G.; Guarrera, P.M.; De Fine, G. Contribution to the Knowledge of the Folk Plant Medicine in Calabria Region (Southern Italy). Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, M.C.; Maxia, L.; Maxia, A. Ethnobotanical Comparison between the Villages of Escolca and Lotzorai (Sardinia, Italy). J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2005, 11, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, F.; Šolić, I.; Dujaković, M.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Grdiša, M. The First Contribution to the Ethnobotany of Inland Dalmatia: Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of the Knin Area, Croatia. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2019, 88, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouasla, A.; Bouasla, I. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Northeastern of Algeria. Phytomedicine 2017, 36, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrió, E.; Vallès, J. Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used in Eastern Mallorca (Balearic Islands, Mediterranean Sea). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarrera, P.M. Traditional Phytotherapy in Central Italy (Marche, Abruzzo, and Latium). Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, F.; de Simone, P.; Senatore, F. Traditional Phytotherapy in the Agri Valley, Lucania, Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1982, 6, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laid, B.; Khellaf, R.; Mouloud, G.; Rabah, B.; Faiçal, B.; Hamenna, B. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Djebel Messaad Region (M’sila, Algeria). Glob. J. Res. Med. Plants Indig. Med. 2014, 3, 445–459. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Bonsangue, G.; Letizia Gargano, M.; Venturella, G.; La Bella, S. Popular Uses of Wild Plant Species for Medicinal Purposes in the Nebrodi Regional Park (North-Eastern Sicily, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonone, R.; De Simone, F.; Morrica, P.; Ramundo, E. Traditional Phytotherapy in the Roccamonfina Volcanic Group, Campania, Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1988, 22, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savo, V.; Caneva, G.; Maria, G.P.; David, R. Folk Phytotherapy of the Amalfi Coast (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L.; Santoro, R.F. Folk Pharmaceutical Knowledge in the Territory of the Dolomiti Lucane, Inland Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 95, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleo, M.; Cambria, S.; Bazan, G. Tradizioni Etnofarmacobotaniche in Alcune Comunità Rurali Dei Monti Di Trapani (Sicilia Occidentale). Quad. Bot. Ambient. Appl. 2013, 24, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpert, M.; Kreft, S. Folk Use of Medicinal Plants in Karst and Gorjanci, Slovenia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miara, M.D.; Bendif, H.; Ait Hammou, M.; Teixidor-Toneu, I. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used by Nomadic Peoples in the Algerian Steppe. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 219, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E.; Quave, C.L. Cross-Cultural Ethnobiology in the Western Balkans: Medical Ethnobotany and Ethnozoology Among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia. Hum. Ecol. 2011, 39, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Cianfaglione, K.; Nedelcheva, A.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Quave, C.L. Resilience at the Border: Traditional Botanical Knowledge among Macedonians and Albanians Living in Gollobordo, Eastern Albania. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Nedelcheva, A.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Scaltriti, B.; Cianfaglione, K.; Quave, C.L. Local Knowledge on Plants and Domestic Remedies in the Mountain Villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania). J. Mt. Sci. 2014, 11, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerreta, S.; Cavero, R.Y.; Calvo, M.I. First Comprehensive Contribution to Medical Ethnobotany of Western Pyrenees. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Traditional Uses of Wild Food Plants, Medicinal Plants, and Domestic Remedies in Albanian, Aromanian and Macedonian Villages in South-Eastern Albania. J. Herb. Med. 2017, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.I.; Akerreta, S.; Cavero, R.Y. Pharmaceutical Ethnobotany in the Riverside of Navarra (Iberian Peninsula). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero, R.Y.; Akerreta, S.; Calvo, M.I. Pharmaceutical Ethnobotany in Northern Navarra (Iberian Peninsula). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, R.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Priestley, C.; Morales, R.; Heinrich, M. Medicinal and Local Food Plants in the South of Alava (Basque Country, Spain). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 176, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballero, M.; Poli, F.; Sacchetti, G.; Loi, M.C. Ethnobotanical Research in the Territory of Fluminimaggiore (South-Western Sardinia). Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 788801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L.; Villanelli, M.L.; Mangino, P.; Sabbatini, G.; Santini, L.; Boccetti, T.; Profili, M.; Ciccioli, T.; Rampa, L.G.; et al. Ethnopharmacognostic Survey on the Natural Ingredients Used in Folk Cosmetics, Cosmeceuticals and Remedies for Healing Skin Diseases in the Inland Marches, Central-Eastern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna, C.; Poggio, L.; Smeriglio, A.; Mariotti, M.; Cornara, L. Ethnomedicinal and Ethnobotanical Survey in the Aosta Valley Side of the Gran Paradiso National Park (Western Alps, Italy). Plants 2022, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menale, B.; Muoio, R. Use of Medicinal Plants in the South-Eastern Area of the Partenio Regional Park (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, V.; Negro, D.; Sarli, G.; De Lisi, A.; Laghetti, G.; Hammer, K. Notes about the Uses of Plants by One of the Last Healers in the Basilicata Region (South Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L. Traditional Pharmacopoeias and Medicines among Albanians and Italians in Southern Italy: A Comparison. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 101, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarella, C.M.; Paglianiti, I.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Spampinato, G. Indagine Etnobotanica Nel Territorio Del Poro e Delle Preserre Calabresi (Vibo Valentia, S-Italia). Atti Soc. Toscana Sci. Nat. Mem. Ser. B 2019, 126, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruca, G.; Spampinato, G.; Turiano, D.; Laghetti, G.; Musarella, C.M. Ethnobotanical Notes about Medicinal and Useful Plants of the Reventino Massif Tradition (Calabria Region, Southern Italy). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2019, 66, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzei, A.D.; Orioni, S.; Sotgiu, R. Contributo Alla Conoscenza Degli Usi Etnobotanici Nella Gallura (Sardegna). Boll. Soc. Sarda Sci. Nat. 1991, 28, 137–177. [Google Scholar]

- Menale, B.; De Castro, O.; Di Iorio, E.; Ranaldi, M.; Muoio, R. Discovering the Ethnobotanical Traditions of the Island of Procida (Campania, Southern Italy). Plant Biosyst. 2022, 156, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Antignani, V.; Idolo, M. Traditional Plant Use in the Phlegraean Fields Regional Park (Campania, Southern Italy). Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, L.; Zitti, S.; Taffetani, F. Ethnobotanical Uses in the Ancona District (Marche Region, Central Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortini, P.; Di Marzio, P.; Guarrera, P.M.; Iorizzi, M. Ethnobotanical Study on the Medicinal Plants in the Mainarde Mountains (Central-Southern Apennine, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 184, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendif, H.; Miara, M.D.; Harir, M.; Merabti, K.; Souilah, N.; Guerrouj, S.; Lebza, R. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in El Mansourah (West of Bordj Bou Arreridj, Algeria). J. Soil Plant Biol. 2018, 1, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, E.B.; Nelly, A.; Annick, D.D.; Frederic, D. Plants Used as Remedies Antirheumatic and Antineuralgic in the Traditional Medicine of Lebanon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 120, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Pavesi, A. Usi Nuovi, Rari o Interessanti Di Piante Officinali Di Alcune Zone Della Calabria. Webbia 1989, 43, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, V.; Senatore, F. Medicinal Plants and Phytotherapy in the Amalfitan Coast, Salerno Province, Campania, Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993, 39, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Krasniqi, F.; Hoxha, E.; Ademi, H.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Medical Ethnobotany of the Albanian Alps in Kosovo. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigat, M.; Vallès, J.; Iglésias, J.; Garnatje, T. Traditional and Alternative Natural Therapeutic Products Used in the Treatment of Respiratory Tract Infectious Diseases in the Eastern Catalan Pyrenees (Iberian Peninsula). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, M.; Carrió, E.; Vallès, J. Ethnobotany of Food Plants in the Alt Empordà Region (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2011, 84, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer, A.M.; Motti, R.; Weckerle, C.S. Traditional Plant Use in the Areas of Monte Vesole and Ascea, Cilento National Park (Campania, Southern Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idolo, M.; Motti, R.; Mazzoleni, S. Ethnobotanical and Phytomedicinal Knowledge in a Long-History Protected Area, the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park (Italian Apennines). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güler, B.; Manav, E.; Uʇurlu, E. Medicinal Plants Used by Traditional Healers in Bozüyük (Bilecik-Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dei Cas, L.; Pugni, F.; Fico, G. Tradition of Use on Medicinal Species in Valfurva (Sondrio, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 163, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Letizia Gargano, M.; Venturella, G.; La Bella, S. Plant Genetic Resources and Traditional Knowledge on Medicinal Use of Wild Shrub and Herbaceous Plant Species in the Etna Regional Park (Eastern Sicily, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 1362–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Savo, V.; Bonsangue, G.; Letizia Gargano, M.; Venturella, G.; La Bella, S. Ethnobotanical Investigation on Wild Medicinal Plants in the Monti Sicani Regional Park (Sicily, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustapha, A.; Abdelhamid, E.M.; Fouad, M.; Hassan, B.; Baha, S.; Khalil, C. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in the Tata Province, Morocco. Int. J. Med. Plant Res. 2012, 1, 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hilaly, J.; Hmammouchi, M.; Lyoussi, B. Ethnobotanical Studies and Economic Evaluation of Medicinal Plants in Taounate Province (Northern Morocco). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 86, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Yaniv, Z.; Mahajna, J. Ethnobotanical Survey in the Palestinian Area: A Classification of the Healing Potential of Medicinal Plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 73, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, Y.; Güzelşemme, M.; Miski, M. Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used in Antakya: A Multicultural District in Hatay Province of Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 174, 118–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargin, S.A.; Akçicek, E.; Selvi, S. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by the Local People of Alaşehir (Manisa) in Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 860–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugulu, I.; Aydin, H. Research on Students’ Traditional Knowledge about Medicinal Plants: Case Study of High Schools in Izmir, Turkey. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Axiotis, E.; Halabalaki, M.; Skaltsounis, L.A. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in the Greek Islands of North Aegean Region. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigat, M.; Bonet, M.À.; Garcia, S.; Garnatje, T.; Vallès, J. Studies on Pharmaceutical Ethnobotany in the High River Ter Valley (Pyrenees, Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 113, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, M.B.; Barhoumi, T.; Abderraba, M. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plant in Djerba Island, Tunisia. Arab. J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2019, 5, 67–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, M.; Boudjelal, A.; Hendel, N.; Sarri, D.; Benkhaled, A. Flora and Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants in the Southeast of the Capital of Hodna (Algeria). Arab. J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2015, 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Maxia, A.; Lancioni, M.C.; Balia, A.N.; Alborghetti, R.; Pieroni, A.; Loi, M.C. Medical Ethnobotany of the Tabarkins, a Northern Italian (Ligurian) Minority in South-Western Sardinia. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2008, 55, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. Insular Pharmacopoeias: Ethnobotanical Characteristics of Medicinal Plants Used on the Adriatic Islands. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 623070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, J.; Mačukanović-Jocić, M.; Jarić, S. Medical Ethnobotany on the Javor Mountain (Bosnia and Herzegovina). Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 27, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menale, B.; Amato, G.; Di Prisco, C.; Muoio, R. Traditional Uses of Plants in North-Western Molise (Central Italy). Delpinoa 2006, 48, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Guarrera, P.M. Ethnobotanical Remarks in Capitanata and Salento Areas (Puglia, Southern Italy). Etnobiología 2005, 5, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Martelli, I.; Braca, A.; Camangi, F. Tradizioni Etnofarmacobotaniche Nel Territorio Del Gabbro (Livorno-Toscana). Quad. Mus. Stor. Nat. Livorno 2015, 26, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Eddouks, M.; Ajebli, M.; Hebi, M. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants Used in Daraa-Tafilalet Region (Province of Errachidia), Morocco. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 198, 516–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polat, R.; Satil, F. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Edremit Gulf (Balikesir–Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, M.; Carrió, E.; Bonet, M.À.; Vallès, J. Ethnobotany of the Alt Empordà Region (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). Plants Used in Human Traditional Medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 124, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Lucia, L.M. Ethnobotanical Remarks on Central and Southern Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mautone, M.; De Martino, L.; De Feo, V. Ethnobotanical Research in Cava de’ Tirreni Area, Southern Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E. The Remedies of the Folk Medicine of the Croatians Living in Ćićarija, Northern Istria. Coll. Antropol. 2008, 32, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cappelletti, E.M.; Trevisan, R.; Foletto, A.; Cattolica, P.M. Le Piante Utilizzate in Medicina Popolare in Due Vallate Trentine: Val Di Ledro e Val Dei Mocheni. Studi Trentini Di Sci. Nat.-Acta Biol. 1981, 58, 119–140. [Google Scholar]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Corradi, L. Ethnopharmacobotanical Remarks on the Province of Chieti Town (Abruzzo, Central Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 74, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camangi, F.; Tomei, P.E. Tradizioni Etno-Farmacobotaniche Nella Provincia Di Livorno: Il Territorio Della Valle Benedetta. Inf. Bot. Ital. 2003, 1, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Petrakou, K.; Iatrou, G.; Lamari, F.N. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants Traded in Herbal Markets in the Peloponnisos, Greece. J. Herb. Med. 2020, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjelal, A.; Henchiri, C.; Sari, M.; Sarri, D.; Hendel, N.; Benkhaled, A.; Ruberto, G. Herbalists and Wild Medicinal Plants in M’Sila (North Algeria): An Ethnopharmacology Survey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karousou, R.; Deirmentzoglou, S. The Herbal Market of Cyprus: Traditional Links and Cultural Exchanges. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmet Sargin, S. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Bozyazi District of Mersin, Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amico, F.P.; Sorce, E.G. Medicinal Plants and Phytotherapy in Mussomeli Area (Caltanisetta, Sicily, Italy). Fitoterapia 1997, 68, 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Madani, S.; Amel, B.; Noui, H.; Djamel, S.; Hadjer, H. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Galactogenic Plants of the Berhoum District (M’sila, Algeria). J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 6, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Blended Divergences: Local Food and Medicinal Plant Uses among Arbëreshë, Occitans, and Autochthonous Calabrians Living in Calabria, Southern Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2020, 154, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lirola, M.J.; González-Tejero, M.R.; Molero-Mesa, J. Ethnobotanical Resources in the Province of Almería, Spain: Campos de Nijar. Econ. Bot. 1996, 50, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Posocco, E.; Pavesi, A. Some New Therapeutic Uses of Several Medicinal Plants in the Province of Terni (Umbria, Central Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 1985, 14, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, M.C.; Poli, F.; Sacchetti, G.; Selenu, M.B.; Ballero, M. Ethnopharmacology of Ogliastra (Villagrande Strisaili, Sardinia, Italy). Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissa, T.A.F.; Palomino, O.M.; Carretero, M.E.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Ethnopharmacological Study of Medicinal Plants Used in the Treatment of CNS Disorders in Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coassini Lokar, L.; Poldini, L.; Angeloni Rossi, G. Appunti Di Etnobotanica Del Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Gortania-Atti Mus. Friul. Stor. Nat. 1983, 4, 101–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, T.; Zaafour, M.; Boumendjel, M. Ethnomedical Knowledge and Traditional Uses of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants of the Wetlands Complex of the Guerbes-Sanhadja Plain (Wilaya of Skikda in Northeastern Algeria). Herb. Med. Open Access 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Novella, R.; Di Novella, N.; De Martino, L.; Mancini, E.; De Feo, V. Traditional Plant Use in the National Park of Cilento and Vallo Di Diano, Campania, Southern, Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leto, C.; Tuttolomondo, T.; La Bella, S.; Licata, M. Ethnobotanical Study in the Madonie Regional Park (Central Sicily, Italy)—Medicinal Use of Wild Shrub and Herbaceous Plant Species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, G.; Pieroni, A. Isolated, but Transnational: The Glocal Nature of Waldensian Ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornara, L.; La Rocca, A.; Terrizzano, L.; Dente, F.; Mariotti, M.G. Ethnobotanical and Phytomedical Knowledge in the North-Western Ligurian Alps. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Savo, V.; Caneva, G. Traditonal Uses of Plants in the Tolfa-Cerite-Manziate Area (Central Italy). Ethnobiol. Lett. 2015, 6, 119–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoni, M.; Milani, F.; Colombo, L.; Nallio, K.; Colombo, P.S.; Giuliani, C.; Bruschi, P.; Fico, G. Using Medicinal Plants in Valmalenco (Italian Alps): From Tradition to Scientific Approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Local Plant Resources in the Ethnobotany of Theth, a Village in the Northern Albanian Alps. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2008, 55, 1197–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomaria, B.; Lattanzi, E. Le Piante Del Territorio Di Cupra Marittima (Marche) Attualmente Usate Nella Medicina Popolare. Arch. Bot. Biogeogr. Ital. 1982, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sarri, M.; Mouyeta, F.M.; Benzianea, M.; Cherieta, A. Traditional Use of Medicinal Plants in a City at Steppic Character(M’sila, Algeria). J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2014, 2, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahri, N. Etude Ethnobotanique Des Plantes Medicinales Dans La Province De Settat (Maroc). J. For. Fac. 2012, 12, 192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, G.; Haznedaroğlu, M.Z.; Doğan, A.; Koyu, H.; Tuzlacı, E. An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Acipayam (Denizli-Turkey). J. Herb. Med. 2017, 10, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidor-Toneu, I.; Martin, G.J.; Ouhammou, A.; Puri, R.K.; Hawkins, J.A. An Ethnomedicinal Survey of a Tashelhit-Speaking Community in the High Atlas, Morocco. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 188, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballero, M.; Fresu, I. Piante Officinali Impiegate in Fitoterapia Nel Territorio Del Marganai (Sardegna Sud Occidentale). Fitoterapia 1991, 62, 524–531. [Google Scholar]

- Lokar, L.C.; Poldini, L. Herbal Remedies in the Traditional Medicine of the Venezia Giulia Region (North East Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 1988, 22, 231–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, A. Le Piante Della Medicina Tradizionale Nell’alta Valle Di Vara (Liguria Orientale). Webbia 1961, 16, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M.; Puricelli, C.; Ciuchi, D.; Segale, A.; Fico, G. Traditional Knowledge on Medicinal and Food Plants Used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—An Alpine Ethnobotanical Study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sanzo, P.; De Martino, L.; Mancini, E.; Feo, V. De Medicinal and Useful Plants in the Tradition of Rotonda, Pollino National Park, Southern Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, V.; Ambrosio, C.; Senatore, F. Traditional Phytotherapy in Caserta Province, Campania, Southern Italy. Fitoterapia 1992, 63, 337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, G.; Doğan, A.; Şenkardeş, İ.; Avci, R.; Tuzlaci, E. The Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of Batman City and Kozluk District (Batman-Turkey). Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2019, 84, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bellomaria, B.; Della Mora, L. Novità Nell’uso Delle Piante Officinali per La Zona Di Matelica (Macerata) Anche in Confronto Con Altre Zone Delle Marche. Arch. Bot. Biogeogr. Ital. 1985, 61, 51–81. [Google Scholar]

- Maccioni, S.; Guazzi, E.; Tomei, P.E. Le Piante Nella Medicina Popolare Del Grossetano. I. Le Colline Fra l’Ombrone e l’Albegna. Atti Mus. Stor. Nat. Maremma 1997, 16, 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, A.; Ballero, M.; Poli, F. Quantitative Ethnopharmacological Study of the Campidano Valley and Urzulei District, Sardinia, Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1997, 57, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Impieri, M. Ethnobotanical Notes about Some Uses of Medicinal Plants in Alto Tirreno Cosentino Area (Calabria, Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanna, C.; Ballero, M.; Maxia, A. Le Piante Medicinali Utilizzate Contro Le Patologie Epidermiche in Ogliastra (Sardegna Centro-Orientale). Atti Mus. Stor. Nat. Maremma 2006, 113, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Maccioni, S.; Guazzi, E.; Ansaldi, M.; Tomei, P.E. L’uso Medicinale Delle Piante Nella Tradizione Popolare Delle Murge Sud-Orientali (Taranto, Puglia). Atti Mus. Stor. Nat. Maremma 2001, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Özkum, D.; Akı, Ö.; Toklu, H.Z. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research Herbal Medicine Use among Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Northern Cyprus. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 1652–1664. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).