Abstract

Pecan (Carya illinoinensis), a globally economically significant dried fruit and woody oil tree, faces significant challenges in production and nut quality due to the rampant outbreak of severe fungal diseases. From 2020 to 2021, an extensive occurrence of a disease resembling gray mold was observed on the leaves and fruits of pecan trees in Jiangsu Province, China. Upon isolation from symptomatic samples, Botrytis cinerea was identified through morphological analysis and phylogenetic studies of the G3PDH, HSP60, and RPB2 gene sequences. Furthermore, pathogenicity tests conclusively attributed the gray mold disease observed on pecan leaves and fruits to B. cinerea. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that B. cinerea has been reported on pecans. These findings thus provide a basis for further research on the management of pecan gray mold.

1. Introduction

Carya illinoinensis, better known as pecan, is a significant species among dried fruit and woody oil trees [1]. Its kernels constitute a superb source of healthful and nutritious food [2]. In recent years, there has been a substantial expansion in pecan cultivation in China, fueled by the escalating demand for nut production. However, this rapid growth may lead to an increased prevalence of diseases within these newly established plantations.

The Sclerotiniaceae genus Botrytis includes significant plant pathogens that inflict gray mold on a broad spectrum of economically vital fruits, crops, and ornamentals [3]. Gray mold often occurs as leaf blight [4], flower blight [5], or fruit rot [6], posing significant challenges to agriculture. However, reliance solely on morphological characteristics like conidial spore size and shape is inadequate for the definitive identification of Botrytis species, necessitating the integration of molecular methodologies [7]. Multigene phylogenetic analyses leveraging housekeeping genes, such as RNA polymerase II (RPB2), heat shock protein 60 (HSP60), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH), have emerged as informative tools in accurately distinguishing Botrytis species [8].

In June 2020, a widespread occurrence of a disease exhibiting symptoms akin to gray mold was observed on the leaves and fruits of pecan trees in Jurong, Jiangsu Province, China. Approximately 45% of pecan trees suffered from this disease (200 trees were surveyed), significantly hindering the growth of young trees and compromising nut production. Notably, to our current understanding, there is no research regarding the pathogenicity of Botrytis species causing gray mold disease on pecan in China. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to isolate, identify, and characterize the pathogenic fungi causing gray mold disease on pecan by means of virulence tests, multi-locus phylogenetic analysis, and morphological studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Survey and Fungal Isolation

A field survey was carried out from September to December 2021 in five pecan orchards in Nanjing and Jurong, Jiangsu Province. In each orchard, 25 plants in each of four corners (southwest, southeast, northwest, and northeast) were arbitrarily selected, and the economic loss was estimated for each orchard. In total, 21 diseased samples bearing gray mold were collected. Each sample was composed of five leaves/fruits from the most severely infected trees within one hectare of the orchard, and sampling was performed on approximately 40 hectares. All the samples were transported in an ice box to a laboratory for further analysis.

Leaf tissues (3 × 3 mm2) at the border of lesions were surface sterilized (5% NaClO for 45 s, 75% ethanol for 45 s), then placed on a potato dextrose agar (PDA) plate supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/mL) and incubated at 25 °C in the dark. Emerging fungal hyphae were transferred to fresh PDA and pure culture was obtained by single-spore isolation [9]. All fungal isolates were primarily identified by colony morphology and the ITS sequences.

2.2. Molecular Characterization

Total genomic DNA was isolated from approximately 7-day-old PDA cultures by gently scraping the mycelium with a sterile scalpel and following the manufacturer’s protocol for the Fungi Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). The ITS, RPB2, HSP60, and GAPDH were amplified and sequenced using the primer pairs ITS1/ITS4 [10], RPB2-F/RPB2-R, HSP60-F/HSP60-R, and G3PDH-F/G3PDH-R [11], respectively. PCR was performed in an Eppendorf Nexus Thermal Cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with a total volume of 50 μL, containing 2 μL of each primer (10 pmol/mL), 4 μL of DNA template (100 ng), 25 µL of 2xEasyTaq PCR SuperMix (Transgen, Beijing, China), and 17 μL of double-distilled H2O. PCR amplification settings were conducted following previous studies [12]. The PCR products were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.3%), and the positive amplicons were purified and sequenced in both directions by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. The quality of the obtained DNA sequences and the contig assembly were performed using Bioedit software v. 7.0.9. All sequences derived in this study have been deposited in GenBank. Sequences with high similarities were downloaded from NCBI and selected for phylogenetic analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Strains of the Botrytis spp. studied in this study and GenBank accessions of the sequences generated.

The phylogenetic relationships among the specimens were thoroughly analyzed utilizing two distinct optimality search methodologies: maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI). For ML analysis, the GTR+G+I evolutionary model was employed within MEGA v. 7 [13], and the stability of the inferred clades was rigorously assessed through 1000 bootstrap replications, with gaps treated as missing data. In contrast, for BI analysis, MrBayes v. 3.2.6 [14] was utilized, preceded by determining the optimal model for each locus using MrModeltest 2.3 based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc). Specifically, TN93+G+I was selected for G3PDH, K2+G for HSP60, and GTR+G+I for RPB2. The BI analysis involved simultaneously running four Markov chains over 1 × 107 generations, with samples collected every 1000 generations. To ensure robustness, the initial 25% of generations were discarded as burn-in, and posterior probabilities (PP) were subsequently calculated for the majority rule consensus tree. Additionally, Monilinia fructigena (strain 9201) was designated as the outgroup to provide a comparative framework for the phylogenetic analysis.

2.3. Morphological Identification

For macroscopic and microscopic characterization, fungal isolates were cultured on PDA at 25 °C. Colony appearance (color, texture, and pigment production), radial growth rate, conidiomata presence, and the formation pattern as well as abundance were assessed 5, 10, and 20 days post-inoculation (dpi). The morphological characteristics of conidiophores, conidia, sclerotia, and conidiogenous cells were observed under a Zeiss Axio Imager A2m microscope (Carl Zeiss Ltd.; Baden-Württemberg; Germany). At least 50 measurements were made for each fungal structure, using an ocular micrometer. The colony growth rate was estimated by measuring two perpendicular directions on three replicates per isolate and calculating the average value for each isolate. Fungal isolates and specimens used in the present study were deposited in Jiangsu Vocational College Agriculture and Forestry (JSAFC).

2.4. Pathogenicity Studies

Two representative isolates (JSAFC 2180 and JSAFC 2213) from leaf spots and two (JSAFC 2188 and JSAFC 2296) from fruit rot of pecan were selected to test for pathogenicity. Spore suspensions of each isolate were prepared by flooding 15-day-old PDA cultures with sterile water and adjusting the collected suspension to 106 spores/mL using a hemacytometer. Prior to inoculation, leaves and fruits were harvested from symptomless pecan trees and surface sterilized as described above. One wound was made on each leaf and fruit (0.2 cm in depth) by stabbing with a sterilized insect pin (0.71 mm in diameter). A conidial suspension (20 µL of 106 spores/mL) was placed on each wound site, with each isolate applied to ≥5 leaves or fruits. Control leaves and fruits were mock-inoculated with sterile water. The experiment was carried out three times.

The inoculated leaves and fruits were carefully placed in transparent plastic boxes lined with sterile filter papers and incubated at 25 °C under a controlled 12-hour photoperiod. To fulfill Koch’s postulates, fungal isolates were reisolated from symptomatic leaves and fruits, and their identities were validated through both phylogenetic and phenotypic comparisons. Disease incidence was meticulously recorded as the percentage of inoculated leaves or fruits that exhibited leaf spot symptoms out of the total inoculated samples. Furthermore, disease severity was assessed one week post-inoculation by precisely measuring lesion length in two perpendicular directions. To identify statistically significant differences in severity among species, Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was employed at a significance level of p < 0.05 using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Field Symptoms, Loss Survey, and Fungal Isolation

The disease occurs on leaves and fruits of many pecan varieties, including Bigenyuan No. 1, Bigenyuan No. 3, and Mahan, in Nanjing and Jurong, Jiangsu Province, China. The initial symptoms were water-soaked and brown to dark brown spots scattered on infected leaves, and part of them were surrounded by yellowish halos (Figure 1A). Gradually, several lesions expanded and fused to form large necrosis as symptoms progressed (Figure 1B). When the fruits were infected, symptoms initially appeared as sunken, sub-circular or irregular, tan to black rot, which gradually enlarged and coalesced to form a large necrotic area (Figure 1C). In the later stage, the lesion reached the immature nut shell, resulting in premature drop (Figure 1D,E). Finally, the kernels became inedible. A survey in Jurong, Jiangsu Province, revealed that the disease breaks out annually and the affected area is often over 10 hectares, causing approximately 40% economic loss. In total, eleven single-spored isolates were recovered from diseased samples, and all the isolates showed consistent morphology in culture on PDA.

Figure 1.

Photographs showing disease symptoms of pecan gray mold in the field. (A,B) The symptoms of leaves. (C–E) The symptoms of fruits.

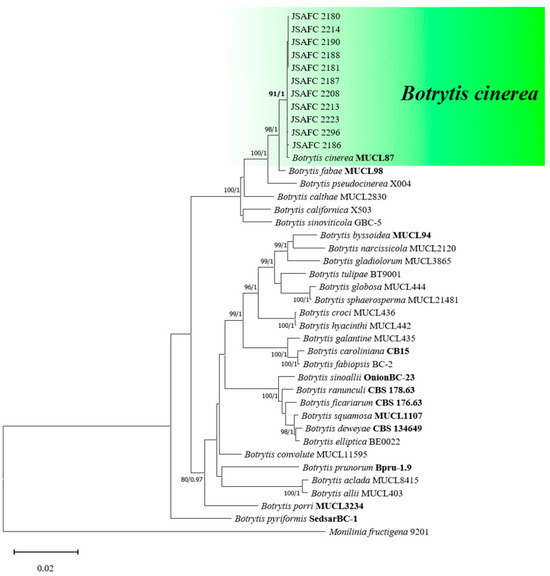

3.2. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis

For the purpose of molecular identification, fragments from three loci—G3PDH, HSP60, and RPB2—were successfully amplified from all eleven isolates under investigation (Table 1). The PCR products exhibited varying lengths, with G3PDH ranging from 913 to 959 bp, HSP60 from 1028 to 1082 bp, and RPB2 from 1181 to 1217 bp. Upon alignment, the concatenated dataset comprising these three loci (G3PDH + HSP60 + RPB2) totaled 2958 nucleotides, of which 2289 were constant sites, 295 were parsimony uninformative sites, and 374 were parsimony informative sites. Both Bayesian Inference (BI) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analyses revealed a compelling result: the eleven isolates studied, including the type specimen of B. cinerea, formed a strongly supported monophyletic group (with a bootstrap value of 94 and posterior probabilities of 1.00) and were clearly distinguished from the other Botrytis species (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood (ML) tree of Botrytis spp. based on combined G3PDH, HSP60, and RPB2 loci. The tree generated by Bayesian inference had a similar topology. Bootstrap values (≥85%) and posterior probabilities (≥0.95) are shown at the nodes. Ex-type or other authoritative cultures are emphasized in bold font. Monilinia fructigena (9201) was used as an outgroup. The scale bar indicates the average number of substitutions per site.

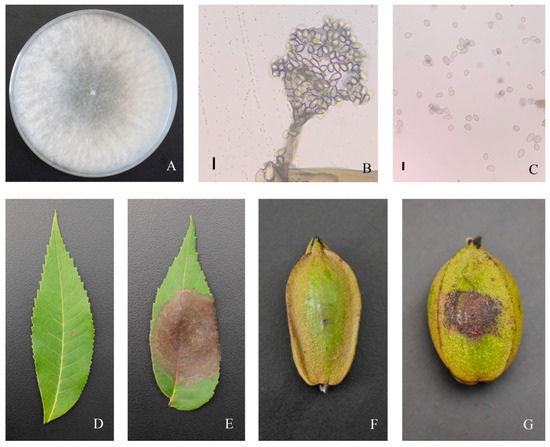

3.3. Morphology

All eleven isolates examined produced rapidly growing colonies with an average growth rate of 2.55 cm/day at 25 °C. No obvious differences in morphology were observed among these isolates. The colonies initially formed fluffy white hyphae on PDA and then turned gray with scarce to abundant sporulation after 2 weeks of incubation. The conidiophores were erect, pale brown, septate, and branched, with sizes ranging from 483.5 to 1982.6 μm in length by 5.3 to 19.6 μm in width (average = 954.2 × 11.1 μm) (Figure 3). The conidia were unicellular, hyaline to light brown, and ellipsoid to ovoid, with the length and width ranging from 7.2 to 14.1 × 4.0 to 6.2 μm (average = 9.6 μm × 5.8 μm) (Figure 3). No sclerotia was observed among those isolates. On the base of the molecular and morphological characteristics, the fungal isolates recovered from the symptomatic samples of pecan were identified as B. cinerea Pers.

Figure 3.

Morphological characteristics and pathogenicity (wounded inoculation) of Botrytis cinerea (isolate JSAFC 2188) from pecan. (A) Photograph showing colony morphology. (B) Photograph showing conidiophores with conidia. (C) Photograph showing conidia. (E) Photograph showing symptom on leaf and (G) fruit 7 days after inoculation. (D,F) Mock control. Scale bars (B,C) = 10 μm.

3.4. Pathogenicity Tests

All representative isolates were pathogenic to leaves and fruits of pecan, regardless of whether the wounded inoculation or non-wounded inoculation method was used. However, wound inoculation resulted in larger lesion sizes compared to non-wound inoculation, suggesting that wounds may be an important pathway for the invasion of B. cinerea. The pathogens were successfully re-isolated from symptomatic tissues but not from healthy (controls). Inoculation of pecan leaves with a spore suspension of B. cinerea isolates resulted in water-soaked lesions followed by necrotic rot (Figure 3). All representative isolates are pathogenic to the leaves of pecan (Table 2). Differences in the diameter of the necrotic lesion were obtained, being JSAFC 2188 the most virulent isolate on both wounded and non-wounded leaves. Pecan fruit inoculations resulted in dark brown, soft, watery decay around the inoculation point at 7 dpi; consistently, JSAFC 2188 was the most virulent isolate (p < 0.05). In contrast, mock-inoculated controls remained asymptomatic, exhibiting only faint discoloration around the wound site. The successful re-isolation of the pathogen from all inoculated tissues and its absence from mock-inoculated controls underscores the fulfillment of Koch’s postulates.

Table 2.

Pathogenicity of Botrytis cinerea isolates on Carya illinoinensis 7 days after inoculation.

4. Discussion

In the present study, a collection of eleven isolates of B. cinerea was systematically acquired from instances of gray mold disease affecting pecan trees in Jurong, Jiangsu Province, China. Remarkably, all of these isolates consistently exhibited a morphological phenotype that is characteristic of B. cinerea, as described by Mirzaei et al. [15]. While phenotypic and genotypic diversity among B. cinerea isolates has been extensively explored in diverse geographical locations worldwide, a comprehensive analysis specifically focusing on B. cinerea isolates causing gray mold disease in pecan trees remains elusive in the published literature to date.

Despite the widespread perception of Botrytis species as aggressive plant pathogens, the Botrytis population displays remarkable diversity, encompassing isolates with various morphotypes and virulence levels that coexist within the same host. Notably, this population includes mycelial-type isolates that lack the ability to initiate infections [16]. This phenotypic variability is potentially further influenced by the presence of transposable elements and/or mycoviruses within the fungal genome, which may modulate fitness attributes, particularly virulence, among Botrytis isolates [17]. In our study, all isolated strains of B. cinerea proved to be pathogenic, causing necrotic lesions on pecan leaves and manifesting as rot symptoms on the fruits. Among these, JSAFC 2188 emerged as the most virulent isolate. Interestingly, despite no apparent morphological differences among representative isolates, their pathogenicity varies significantly, particularly in the case of JSAFC 2296, which exhibits relatively low pathogenicity when inoculated onto leaves or fruits. This may be related to the mycoviruses it carries. More profoundly, given the importance of B. cinerea in agricultural and forestry production, subsequent research could aim to isolate the mycoviruses from hypovirulent strains and attempt to apply them in the control of gray mold disease.

Botrytis cinerea boasts an exceptionally broad host range, encompassing 616 genera and exceeding 1600 plant species, solidifying its position as the second most significant phytopathogen globally, both scientifically and economically [3,18]. This fungus is notorious for causing gray mold, a pervasive and devastating disease that jeopardizes the yields of numerous fruits, vegetables, and medicinal plants [19,20,21]. Given its potential as a source of inoculum for gray mold in grapes, pears, and cherries in China [22,23,24], the threat posed by B. cinerea is particularly acute. In Jiangsu Province, where cherry orchards, pear orchards, and grape vineyards are often situated in close proximity to commercial pecan orchards, the risk of cross-infection between these hosts escalates significantly. This proximity facilitates the spread of the pathogen, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring and management strategies to mitigate the devastating impacts of B. cinerea on agricultural productivity.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our comprehensive analysis, incorporating symptom observation, cultural and microscopic characterization, molecular data analysis, and pathogenicity testing, definitively identified B. cinerea as the fungal pathogen responsible for gray mold disease on pecan. Notably, this represents the first documented case of B. cinerea causing gray mold in C. illinoinensis in China. These findings contribute valuable insights to the knowledge base on gray mold on pecan and highlight the need for targeted control measures to mitigate its impact on agricultural productivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-J.C.; methodology, X.-R.Z.; software, X.-R.Z.; validation, X.-X.H.; formal analysis, X.-X.H.; investigation, X.-X.H.; resources, X.-R.Z.; data curation, J.-F.P.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-R.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.-R.Z. and X.-X.H.; visualization, X.-R.Z. and J.-F.P.; supervision, J.-J.C. and Y.G.; project administration, J.-J.C.; funding acquisition, X.-R.Z. and X.-X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Fund of the Jiangsu Vocational College of Agriculture and Forestry (2023kj25, 2024rc55), Zhenjiang Innovation Capacity Building Project (SS2024010), and the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (20KJB220003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, R.; Peng, F.R.; Li, Y.R. Pecan production in China. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 197, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.C.; Ren, H.D.; Yao, X.H.; Wang, K.L.; Chang, J.; Shao, W.Z. Metabolomics and transcriptomics analyses reveal regulatory networks associated with fatty acid accumulation in Pecan kernels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 16010–16020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Caseys, C.; Kliebenstein, D.J. Genetic and molecular landscapes of the generalist phytopathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Yao, J.W.; Wang, B.B.; Zheng, J.L.; Cao, C.X.; Huang, D.Y. First report of Botrytis cinerea causing gray mold on tea (Camellia sinensis) in China. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.L.; Zhang, Q.H.; Zeng, X.G.; Chen, X.Y.; Liu, S.J.; Han, Y.C. Deciphering the molecular signatures associated with resistance to Botrytis cinerea in strawberry flower by comparative and dynamic transcriptome analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 888939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, M.; Singh, P.; Pandey, A.K. Botrytis fruit rot management: What have we achieved so far? Food Microbiol. 2024, 122, 104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrada, E.E.; Latorre, B.A.; Zoffoli, J.P.; Castillo, A. Identification and characterization of Botrytis Blossom Blight of Japanese Plums caused by Botrytis cinerea and B. prunorum sp. nov in Chile. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moparthi, S.; Parikh, L.P.; Troth, E.G.; Burrows, M.E. Identification and prevalence of seedborne Botrytis spp. in Dry Pea, Lentil, and Chickpea in Montana. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Li, D.W.; Si, Y.Z.; Li, M.; Huang, L.; Zhu, L.H. Three new species of Diaporthe causing leaf blight on Acer palmatum in China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.; Innis, M.; Gelfand, D.; Sninsky, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Staats, M.; van Baarlen, P.; van Kan, J.A.L. Molecular phylogeny of the plant pathogenic genus Botrytis and the evolution of the specificity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.Z. Botrytis polyphyllae: A new Botrytis species causing gray mold on Paris polyphylla. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Goltapeh, E.M.; Shams-Bakhsh, M.; Safaie, N. Identification of Botrytis spp. on plants grown in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2008, 156, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, W.A.; Marques-Costa, T.M.; Santander-Gordón, D.; Fernández, F.A.; Zabalgogeazcoa, I.; de Aldana, B.R.V.; Sukno, S.A.; Díaz-Mínguez, J.M.; Benito, E.P. Physiological and population genetic analysis of Botrytis field isolates from vineyards in Castilla y León, Spain. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, C.A.; Castillo, A.; Castro, M.; Cottet, L.; Morales, A. A wild-type Botrytis cinerea strain co-infected by double-stranded RNA mycoviruses presents hypovirulence-associated traits. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.L.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Liang, Y.; Mengiste, T.; Sharon, A. Killing softly: A roadmap of Botrytis cinerea pathogenicity. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Smilanick, J.L.; Feliziani, E.; Droby, S. Integrated management of postharvest gray mold on fruit crops. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 113, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, B.A.; Elfar, K.; Ferrada, E.E. Gray mold caused by Botrytis cinerea limits grape production in Chile. Cienc. Investig. Agrar. 2015, 42, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.X.; Adnan, M.; Shang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Luo, C.X. Sensitivity of Botrytis cinerea from Nectarine/Cherry in China to six fungicides and characterization of resistant isolates. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Shen, F.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, D. Characterization of Botrytis cinerea isolates from grape vineyards in China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, X.J.; Sun, B. First report of Botrytis cinerea causing fruit rot of Pyrus sinkiangensis in China. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).