Abstract

Several organic acids have been indicated among the top value chemicals from biomass. Lignocellulose is among the most attractive feedstocks for biorefining processes owing to its high abundance and low cost. However, its highly complex nature and recalcitrance to biodegradation hinder development of cost-competitive fermentation processes. Here, current progress in development of single-pot fermentation (i.e., consolidated bioprocessing, CBP) of lignocellulosic biomass to high value organic acids will be examined, based on the potential of this approach to dramatically reduce process costs. Different strategies for CBP development will be considered such as: (i) design of microbial consortia consisting of (hemi)cellulolytic and valuable-compound producing strains; (ii) engineering of microorganisms that combine biomass-degrading and high-value compound-producing properties in a single strain. The present review will mainly focus on production of organic acids with application as building block chemicals (e.g., adipic, cis,cis-muconic, fumaric, itaconic, lactic, malic, and succinic acid) since polymer synthesis constitutes the largest sector in the chemical industry. Current research advances will be illustrated together with challenges and perspectives for future investigations. In addition, attention will be dedicated to development of acid tolerant microorganisms, an essential feature for improving titer and productivity of fermentative production of acids.

1. Introduction

Lignocellulose is the largest biomass on Earth and includes many wastes produced by human activities (e.g., agriculture by-products, municipal solid wastes, paper mill sludge) [1]. Lignocellulose constitutes the structural backbone of all plant cell walls and is mainly composed by cellulose (40–50%), hemicellulose (25–30%), and lignin (15–20%) [2]. Because of its low cost (for comparison, the current price of pulp grade wood is about 35 US$/ton, while sugar costs about 460 US$/ton) [3,4], lignocellulose is among the most attractive substrates for biorefining strategies to produce high-value compounds (e.g., biofuels, bioplastics) through microbial fermentation [5]. So far, most studies on lignocellulose (namely, second generation) biorefining have been addressed to production of fuels (e.g., ethanol, butanol) owing to larger economic interest in these chemicals [6]. However, there is increasing interest in using lignocellulose feedstocks for production of other commodity chemicals such as organic acids [7,8,9]. In fact, a 2004 report of the US Department of Energy included a number of carboxylic acids (e.g., succinic, fumaric, malic, glucaric, 3-hydroxypropionic, and itaconic acid) among the top value platform chemicals derived from biomass based on their chemical properties, previous and potential market, and technical complexity of their synthesis pathway(s) [10]. Using similar criteria and taking into account the technological advances that had occurred in the meantime, additional chemicals were included in this list six years later, such as lactic acid [11]. Industrial interest in organic acids mainly refers to their use as building-block chemicals [12], although other applications (e.g., food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and textile industry) may be relevant, depending on the specific compound (Table 1). Application potential of microbial-derived organic acids strongly depends on their price, which in most cases currently limits their competitiveness with oil-derived compounds. Nowadays, the market size of these chemicals is far smaller than that of biofuels (Table 1). For comparison, in 2020, the market size of ethanol was estimated at about 95 billion US$ [13], while that of adipic acid (the most commercially important organic acid) was about 5 billion US$ [14]. Establishing cost-competitive microbial production processes (e.g., by using cheaper fermentation feedstock) is therefore the key for fully expanding the market of these compounds [10], which is among the priority areas of economic development designated by the European Commission [15].

Table 1.

Most recent estimation of economic parameters, production feedstocks, and applications of some top value organic acids. 3-HP, 3-hydroxypropionic acid; AA, adipic acid; CAGR, compound annual growth rate; CCM, cis,cis-muconic acid; FA, fumaric acid; GA, glucaric acid; IA, itaconic acid; LA, lactic acid; MA, malic acid; n.a., not available; SA, succinic acid.

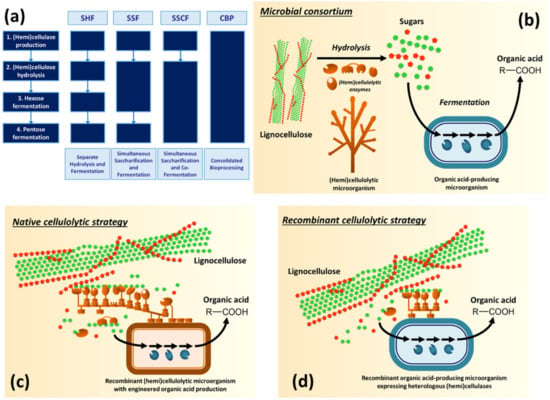

Despite the low cost of lignocellulose, the current processes for its fermentation remain expensive because of biomass complexity and recalcitrance to biodegradation. Since no natural microorganism isolated so far can catalyze single-step fermentation of lignocellulose to high-value chemicals, inefficient multistep processes are required that feature biomass pre-treatment and/or dedicated cellulase production and/or separated biomass saccharification and/or hexose and/or pentose fermentation [7,38] (Figure 1a). Substantial research effort has been dedicated to develop single-step fermentation (namely, consolidated bioprocessing, CBP) of lignocellulosic biomass based on potential dramatic reduction of capital and operating cost of the process, which has been estimated between 40–77% with respect to less consolidated configurations (i.e., simultaneous saccharification and fermentation, SSF, or simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation, SSCF) [39,40]. To this aim, two main paradigms have been pursued, namely the development of: (i) synthetic microbial consortia based on co-cultures of (hemi)cellulolytic and high-value compound producing microorganisms (Figure 1b) [41,42,43,44]; (ii) recombinant microorganisms that combine (hemi)cellulolytic and compound-producing properties in a single strain by metabolic engineering [5,45,46,47,48] (Figure 1c,d). Each strategy has specific potentials and issues. Microbial consortia can benefit from synergism between microbial specialists, thus simulating decay of plant material in natural environments. However, designing and maintaining stable artificial microbial communities may be challenging [49,50]. Metabolic engineering aims to develop single strain with efficient lignocellulose degradation and product formation, yet substantial effort is needed for major genetic and metabolic redesign of a microorganism. As regards construction of recombinant microorganisms for CBP, two main alternative approaches have been used [40,51,52]. Native cellulolytic strategies (NCSs) aim at introducing and/or improving high-value product biosynthetic pathways into natural (hemi)cellulolytic strains (e.g., Clostridium cellulovorans, Clostridium thermocellum, Figure 1c) [5]. The purpose of recombinant cellulolytic strategies (RCSs) is to confer (hemi)cellulolytic ability to microorganisms with valuable product formation properties (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Yarrowia lipolytica, lactic acid bacteria) and include heterologous cellulase expression [47,53,54] (Figure 1d). Current progress of NCSs benefits from recent development of efficient gene tools for manipulating a number of (hemi)cellulolytic bacteria (e.g., Caldicellulosiruptor bescii, C. cellulovorans, C. thermocellum, C. cellulovorans, Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum) [55,56,57,58,59], and fungi (e.g., Myceliophthora thermophila) [60]. RCSs are based on mimicking natural cellulase systems, especially the non-complexed enzyme model of aerobic microorganisms (e.g., Trichoderma reesei), and the cellulosome complexes of anaerobic microbes (e.g., C. thermocellum) [61]. The complexity of the native cellulase systems and issues related to their expression in heterologous hosts have severely hampered RCSs [38,62,63]. However, substantial advances have been achieved also in this direction, such as the expression of highly sophisticated cellulosome (up to 63 enzymatic subunits) in Kluyveromyces marxianus [64]. In addition, research interest has been growing on exploiting natural lignocellulose-decomposing microbial communities (e.g., from soil, compost, marine sediments) for biorefining purposes, with special attention on the microbiota of herbivore rumen or wood-eating insect (e.g., termites) gut [65,66]. Advantages of this approach include the established synergistic activity among the microbial symbionts (leading to improved lignocellulose degradation) and the possibility to perform fermentations under non-sterile conditions [65,66]. However, harnessing the complexity of these microbial communities towards reliable and efficient lignocellulose bioconversion to high-value compounds still requires significant research efforts [65,66,67].

Figure 1.

Paths towards consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) of lignocellulosic feedstocks to organic acids. (a) Fermentation of lignocellulosic biomass involves four biological events (production of hemi/cellulolytic enzymes, biomass saccharification, hexose and pentose fermentation). In SHF (separate hydrolysis and fermentation) configuration, each event occurs in a dedicated bioreactor, while CBP features a single fermenter in which all biological events are performed. CBP can be developed through consortia of (hemi)cellulolytic (brown) and organic acid-producing (blue) microorganisms (b), by metabolic engineering of a native (hemi)cellulolytic microorganism with organic acid-producing pathway (native cellulolytic strategy) (c), or by an efficient organic acid-producing microorganism engineered with a heterologous (hemi)cellulase system (recombinant cellulolytic strategy) (d).

The present review aims to summarize the current progress of research towards production of top value organic acids through CBP of lignocellulosic feedstocks. Here, interest was targeted to organic acids with application in polymer synthesis (i.e., 3-hydropropionic, adipic, fumaric, itaconic, lactic, malic, and succinic acid), the largest segment in the chemical industry [11]. Two additional building block organic acids that can be obtained from lignocellulose, namely levulinic and furan dicarboxylic acid, were excluded from this review since their production relies exclusively or mainly on chemical treatment of C6 monosaccharides derived from biomass: (i) levulinic acid is currently produced through acid treatment of sugars [68]; (ii) fermentative production of furan dicarboxylic acid has been reported through bioconversion of 5-hydroxymethyl furfuraldehyde, which is obtained by acid treatment of sugars [69]. The development of a new industrial process for production of a chemical must fulfill several requirements, such as high titer, productivity, and yield. For carboxylic acid production, 50–100 g/L titer, 1–3 g/L/h productivity, and >0.5 g/g yield are generally required for economic sustainability of the process [70,71]. Among the microbial host characteristics enabling obtention of these parameters by fermentation, there is tolerance to strong acidic pH conditions (ideally, around the pKa(s) of the acid) [23]. High acid tolerance of microbial strains is preferable for process cost, since it avoids utilization of neutralizing agents or more complex and expensive systems for continuous acid removal [70,72,73]. Acid tolerance of microorganisms and metabolic engineering strategies for improving it will be discussed in Section 3. Final product recovery and purification is another critical step for the commercialization of bio-based compounds. For organic acids, these downstream operations may account for 20 to 60% of the entire production process cost [19,74]. Downstream processing of fermentative carboxylic acids generally combines multiple methodologies for removing major impurities (e.g., adsorption, extraction, precipitation, electrodialysis), water, and minor contaminants (e.g., reverse osmosis, evaporation, distillation, chromatography) [75]. Methods of choice depend on a number of factors such as the characteristics of the carboxylic acid (e.g., 3-hydroxypropionic acid cannot be purified by distillation since it decomposes at high temperatures) [19] and the fermentation process [75]. Since these aspects are not specifically related to utilization of lignocellulosic feedstocks, please refer to extensive reviews on this topic [75,76].

2. Production of Organic Acids through Consolidated Bioprocessing (CBP) of Lignocellulosic Biomass

2.1. C3 Organic Acids

2.1.1. Lactic Acid (LA)

LA has broad application that encompasses the food (e.g., acidifier, emulsifier, preservative, and flavor-enhancer), cosmetic (emulsifying and moisturizing agent), pharmaceutical (intermediate), and chemical industry (e.g., production of solvents and bioplastics) [77]. LA use as building block for polylactide (PLA, a biodegradable and biocompatible plastic with applications in the medical, agriculture, and packaging areas) synthesis has probably been among the main drivers of the global market expansion of LA [77,78,79]. The worldwide demand of LA was 1,220.0 kt in 2016 and is expected to reach 1,960.1 kt in 2025 [77]. About 90% of global LA production is obtained by microbial fermentation of food crops (mainly corn and sugarcane), which raises ethical and economical concerns [77,79]. Microbial fermentation is required for producing pure L- or D-LA enantiomer, since chemical synthesis generates a racemic mixture. This is essential especially for PLA synthesis (which uses pure LA enantiomer(s)) [73], and food and pharmaceutical applications (D-LA can cause metabolic problems in humans) [80]. Industrial processes for LA production mainly rely on lactic acid bacteria (LAB) [12], but bacteria and fungi belonging to the Bacillus and Rhizopus genus, respectively, include other efficient LA producers [38,81]. However, the current cost of LA is relatively high (US$ 1.30–4.0/kg) and can fluctuate significantly depending on the price of starch/sugar fermentation feedstock [17]. It has been estimated that the cost of LA should be ≤US$ 0.8/kg for PLA to be economically competitive with fossil fuel–based polymers [82]. Therefore, a significant number of studies have been aimed at LA generation through fermentation of alternative non-food feedstocks such as lignocellulose [7,83]. With reference to development of CBP, both design of microbial consortia and development of recombinant cellulolytic strains by metabolic engineering have been explored.

Most RCSs aimed to produce LA have been targeted to LAB (mainly Lactococcus lactis and Lactobacillus plantarum) [7,38,83], with first attempts that date back to the end of the 1980s [84,85]. This has led to recombinant strains expressing complex (hemi)cellulase systems and/or with the ability to depolymerize (hemi)cellulosic substrates and/or with improved metabolism of pentose sugars [7,38,83]. However, direct lignocellulose fermentation to LA through this approach remains highly challenging. So far, the most complex cellulosic substrate that could be efficiently converted to LA by recombinant cellulolytic LAB was cellooctaose by a L. lactis secreting heterologous β-glucosidase and endoglucanase [45] (Table 2). In general, RCSs are hindered by the metabolic burden caused by secretion of multiple heterologous (hemi)cellulases. Of note, the design of engineered LAB consortia, in which each strain expresses a single heterologous enzyme or protein, led to display of mini-cellulosomes consisting of up to six enzymatic components (of four different types, i.e., two cellulases and two xylanases from Clostridium papyrosolvens) on the surface of L. plantarum [46]. This engineered L. plantarum consortium showed improved hydrolysis of wheat straw, yet the amount and/or type of sugars released was insufficient/unsuitable to support L. plantarum growth [46,86]. As regards expression of heterologous (hemi)cellulases, Bacillus sp. hosts may benefit from efficient protein secretion properties [87,88]. Engineering of a single B. subtilis strain that displays large (8 subunits) designer cellulosomes at its surface has recently been reported [89]. Hopefully, a similar approach could be used in the near future to enable growth of LA-accumulating Bacillus strains on raw cellulosic materials.

Table 2.

Most successful examples of CBP of lignocellulosic biomass to organic acids. Maximum theoretical yields were calculated as follows: lactic acid, 2 mol/mol glucose (i.e., Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway followed by pyruvate reduction by lactate dehydrogenase); fumaric, malic, succinic acid, 2 mol/mol glucose (i.e., reductive TCA pathway); itaconic acid, 1 mol/mol glucose (i.e., TCA cycle); adipic acid, 0.92 mol/mol glucose (reverse adipate degradation pathway); cis,cis-muconic acid, 1 mol/mol monoaromatic hydrocarbon (i.e., β-ketoadipate pathway); glucaric acid, 1 mol/mol glucose (i.e., synthetic pathway, see text). Maximum theoretical yields from pentose sugars were calculated based on phosphoketolase pathway and correspond to 1 mole of organic (fumaric, itaconic, lactic, malic, or succinic) acid per mole of sugar. The symbol “≈” was used for approximate values that were calculated from data in the corresponding studies. %M, % of theoretical maximum yield; AA, adipic acid; CBP, consolidated bioprocessing; CCM, cis,cis-muconic acid; FA, fumaric acid; GA, glucaric acid; IA, itaconic acid; LA, lactic acid; MA, malic acid; MC, microbial consortium; n.a., data not available; NCS, native cellulolytic strategy; P, volumetric productivity; RCS, recombinant cellulolytic strategy; SA, succinic acid; T, titer; Y, yield.

Improvement of LA production in natural (hemi)cellulolytic microorganisms is at its infancy. Metabolic engineering studies on a number of (hemi)cellulolytic bacteria such as C. thermocellum [90,91], C. bescii [92], Thermoanaerobacter mathranii [93], T. saccharolyticum [94], and Thermoanaerobacterium thermosaccharolyticum [95] have suggested promising strategies to enhance LA accumulation in these strains. In most cases they consisted in disruption of fermentative pathways that compete with LA biosynthesis for reducing equivalents (e.g., production of H2), carbon substrates (e.g., production of acetate), or both (production of ethanol and formate) (reviewed by [7]). Alternative strategies focused on increasing expression of lactate dehydrogenase (Ldh) [91,92] or engineering the redox state of the cell [96,97,98]. So far, the highest LA titer (7.9 g/L) was obtained through cellobiose fermentation by a C. thermocellum strain in which ethanol production had been disrupted (by deletion of its main alcohol/aldehyde dehydrogenase AdhE), and featuring a mutant Ldh, which is independent from allosteric activation by fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) (Table 2) [90,91,99]. About 85% of the maximum theoretical yield was obtained, but at low volumetric productivity (0.2 g/L/h). Furthermore, initial cellobiose concentrations higher than 10 g/L were not fermented in batch conditions [99]. This observation is most likely related to low C. thermocellum tolerance to pH ≤ 6, which is generated by LA accumulation into the growth medium. Unfortunately, low acid tolerance seems a characteristic common to other cellulolytic bacteria such as Clostridium cellulovorans and Fibrobacter succinogenes, as described in Section 3. In addition, the activity of microbial Ldh enzymes may be regulated by a number of compounds such as nicotinamide cofactors [100,101], ATP, and PPi [101], in addition to FBP, which should be taken into account in metabolic engineering strategies.

Recently, two attempts of CBP based on consortia of the cellulolytic fungus Trichoderma reesei and LA-producing bacteria [41] or fungi [43] have been reported. T. reesei-Rhizopus oryzae co-culture on 40 g/L microcrystalline cellulose led to rather limited LA titer (4.4 g/L, that corresponds to 11% of the maximum theoretical yield) and volumetric productivity (16.7 mg/L/h) [43]. Possible LA consumption by T. reesei has been hypothesized as among the factors limiting LA production by this approach. Higher efficiency was reported by using a T. reesei-Lactobacillus pentosus consortium [41]. Batch fermentation of about 50 g/L microcrystalline cellulose resulted in up to 34.7 g/L LA (corresponding to 62.4% of the maximum theoretical yield), at a productivity of 0.16 g/L/h (Table 2). Similar or higher LA yields were obtained on steam pre-treated beech wood, although a number of factors led to lower titer and productivity: (i) stirring issues in the bioreactor limited amounts of beech wood solids to about 38.6 g/L; (ii) pentose sugars present in biomass are fermented to LA with a maximal yield of 1 mol/mol instead of 2 LA mol/mol obtained from hexoses; (iii) biomass pretreatment generates a number of compounds that inhibit microbial growth (e.g., acetic acid, formic acid, phenolics, furfural, and hydroxymethylfurfural); metabolism of pentose sugars is inhibited by carbon catabolite repression [41]. However, through optimized two-stage biomass pretreatment and using prehydrolyzate (namely the liquid phase derived from biomass steam pretreatment) as fermentation feeding, 19.8 g/L LA was generated (85.2% of the maximum theoretical yield) at a productivity of about 0.1 g/L/h (Table 2) [41].

2.1.2. 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid (3-HP)

Applications of 3-HP include: (i) direct use (e.g., as additive or preservative in food and feed); (ii) polymerization (to poly 3-HP or other 3-HP containing plastic polymers) and; (iii) conversion to other high-value compounds (such as acrylic acid) [19,20]. This potential has fostered a significant expansion in the number of studies and patents related to 3-HP production over the last decade [19]. A number of heterotrophic metabolic pathways have been exploited/engineered for 3-HP production, which are mostly based on fermentation of monosaccharides (mainly glucose) and/or glycerol [19,113]. However, the highest 3-HP titer reported so far (154 g/L) was obtained through bioconversion of 1,3-propanediol by means of Halomonas bluephagenesis [114]. As regards sugar fermentation, remarkable 3-HP titers (i.e., 30–60 g/L, corresponding to about 50% of the maximum theoretical yield) were obtained by using engineered malonyl-CoA or β-alanine or CoA-independent glycerol oxidation pathway [19,113]. Some studies aimed for 3-HP generation from xylose by using Escherichia coli, and Corynebacterium glutamicum or S. cerevisiae can be intended as attempts to develop a process for using lignocellulosic feedstocks [115,116,117]. However, no direct evidence of 3-HP production from lignocellulosic biomass by either traditional or CBP has been reported, as far as I know.

2.2. C4 Organic Acids: Fumaric Acid (FA), Malic Acid (MA), and Succinic Acid (SA)

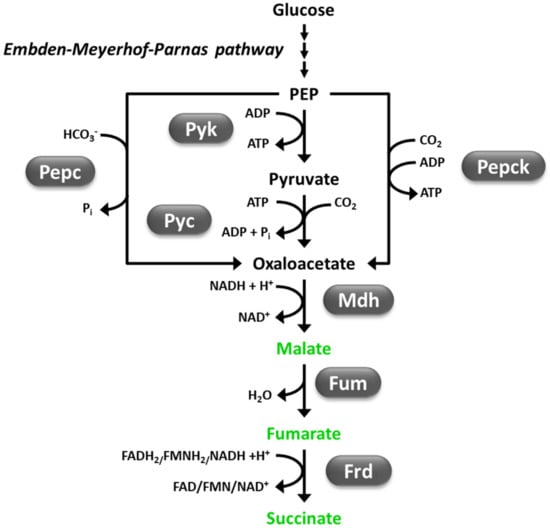

FA [(E)-2-butenedioic acid or trans-1,2-ethylenedicarboxylic acid], MA (hydroxybutanedioic acid), and SA (butanedioic acid) are intermediate compounds of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, hence, they are almost ubiquitous in living organisms [118]. However, only a number of microorganisms naturally accumulate significant amounts of one or more of these compounds. Filamentous fungi of the Rhizopus genus are known as strong FA producers, while those belonging to Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Ustilago genera include efficient MA producers [119]. Native accumulation of relevant SA amounts is mainly associated with rumen-isolated bacteria [120]. Native production of SA has been more rarely described in fungi, possibly because in eukaryotes, SA is produced in mitochondria and its secretion requires transport across mitochondrial and cytoplasmic membranes, while FA and MA can be produced in the cytoplasm [120,121]. Apart from the TCA cycle, generation of these C4-dicarboxylic acids may occur through different metabolic pathways, such as the reductive TCA (rTCA) pathway and the glyoxylate route [119,122]. Strong native producers of these compounds generally employ cytosolic rTCA pathway, which leads to the highest theoretical yield (i.e., 2 mol C4-dicarboxylic acid/mol glucose) (Figure 2). This route consists in carboxylation of pyruvate to oxalacetate (by pyruvate carboxylase, Pyc), which is reduced to MA by NADH-dependent malate dehydrogenase (Mdh). MA can then be dehydrated to FA by fumarase, which may be reduced to SA by flavin o pyridine-dependent fumarate reductase (Figure 2) [123,124]. This metabolic pathway is ATP neutral (2 ATP molecules produced during glycolysis are consumed through pyruvate carboxylation) and involves the net fixation of 1 CO2 mole per each C4-dicarboxylic acid mole. The latter feature represents an additional advantage of fermentative generation of C4 dicarboxylic acids towards reduction of greenhouse gas production [123].

Figure 2.

The reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) pathway for production of C4 dicarboxylic acids (fumaric, malic, and succinic acid, indicated in green) [119,122]. Fum, fumarase; Frd, fumarate reductase; Mdh, malate dehydrogenase; Pepc, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; Pepck, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; Pyc, pyruvate carboxylase; Pyk, pyruvate kinase.

2.2.1. Fumaric Acid (FA)

Many microorganisms accumulate small FA amounts [123]. Fermentative production of FA was used during the 1940s [125], but was long replaced by chemical synthesis from petrochemical feedstocks [123]. Chemical synthesis of FA is obtained from maleic anhydride, which in turn is produced from butane. However, the search for more environmental friendly processes with lower dependence on fossil fuels has renewed interest in biotechnological production of FA [123]. FA structure (that includes carbon–carbon double bond and two carboxylic acid groups) is suitable for many industrial applications, such as starting material for polymerization and esterification reactions [123]. For polymer synthesis, such as production of polyester resins, maleic anhydride has generally been preferred to FA because maleic anhydride is cheaper. However, FA is not toxic and can lead to polymers with improved structural properties [123]. With respect to other bio-based building block chemicals such as MA and SA, FA has lower aqueous solubility and pKa values, which improves FA recovery from fermentation broths [123]. Additional applications of FA are in the pharmaceutical industry (e.g., to treat psoriasis, a skin condition characterized by insufficient production of FA) [126,127] and as supplement for cattle feed owing to its ability to dramatically reduce (up to 70%) cattle emissions of greenhouse gas methane [128].

Most FA producers belong to different fungi genera, with members of the Rhizopus genus as among the most efficient producers [123]. Under balanced growth and aerobic conditions, C4 dicarboxylic acids are used for biosynthetic reactions. However, when nitrogen amounts limit growth, reductive pyruvate carboxylation continues and leads to accumulation of these compounds via the rTCA pathway at a maximum theoretical yield of 1.29 g FA/g glucose [129]. However, no ATP is produced through rTCA pathway, so it is likely that a part of pyruvate flux is diverted towards the TCA cycle even during FA accumulation for providing energy for maintenance, thus reducing FA yield with respect to maximum theoretical value [130,131].

Recently, a fungal consortium composed by T. reesei (cellulolytic) and Rhizopus delemar (FA producer) has been developed for CBP of lignocellulosic biomass to FA [43]. This consortium was designed based on T. reesei ability to hydrolyze both cellulose and hemicellulose and R. delemar ability to ferment both glucose and xylose. A defined minimal medium was formulated for this purpose, which contains a limiting amount of nitrogen [42,132]. In fact, nitrogen starvation stops growth of both fungi and triggers FA accumulation by R. delemar. To find the best tradeoff enabling sufficient microbial growth and high FA titer, three nitrogen concentrations were tested, which resulted in different culture dynamics and FA production titer, yield, and productivity [43]. Intermediate nitrogen concentration led to the most efficient FA generation on both microcrystalline cellulose and alkaline pretreated corn stover. For cultures on microcrystalline cellulose, 11.76 mM nitrogen was supplemented, which resulted in 0.17 g/g FA yield, 31.8 mg/L/h FA volumetric productivity, and 6.87 g/L FA titer. Corn stover mainly consists of glucan (48%) and xylan (21%), but also contains some nitrogen amounts (e.g., plant proteins), therefore, nitrogen supplementation in the growth medium was reduced (2.9 mM). Nonetheless, consortium performance on this feedstock was far lower since only 0.69 g/L FA was accumulated at a yield of 0.05 g/g total initial fermentable carbohydrates. The most likely reason for this reduction in performance was R. delemar sensitivity to inhibitory compounds present in pretreated lignocellulosic biomass [43]. However, future optimization of this microbial consortium appears feasible. In particular, more fine differential tuning of the growth of the two fungal partners could enable more efficient conversion of soluble sugars derived from biomass hydrolysis to FA without sugar accumulation.

Interestingly, a recent study reported improvement of FA production by metabolic engineering of the thermophilic cellulolytic fungus Myceliophthora thermophila [133]. This was obtained by complex metabolic modification including: (i) overexpression of heterologous cytosolic fumarase (MA → FA + H2O) and cytoplasmic membrane FA exporter; (ii) elimination of FA consuming reactions (i.e., cytosolic fumarate reductases, FA + FADH2/FMNH2/NADH + H+ → SA + FAD/FMN/NAD+, and mitochondrial fumarase, FA + H2O → MA); (iii) improvement of cytosolic concentration of MA by disrupting the mitochondrial MA carrier and; iv) overexpression of the mitochondrial FA exporter. The engineered M. thermophila was able to generate 17 g/L FA by fed-batch fermentation of glucose. Hence, this strain shows promising characteristics for FA production through direct fermentation of lignocellulosic feedstocks, although this requires experimental confirmation.

2.2.2. Malic Acid (MA)

MA is mainly used as an additive in food, beverages, and confectionaries, while non-food applications include metal cleaning and finishing, textile finishing, electroless plating, production of pharmaceuticals [125], and biodegradable plastic polymers (e.g., poli β-L-malic acid) [134,135,136]. In 2016, the annual worldwide production of MA was estimated at 60,000 metric tons [102]; however, the global MA market has been predicted to being able to exceed 200,000 metric tons per year [119]. Various online bulk retailers of MA reported costs of around US$ 2.0–4.4 per kg [27,28]. It has been estimated that the cost of fermentative production of MA should be ≤US$ 0.55/kg for MA to be competitive with its petrochemical-based counterpart [27].

MA can exist as D or L-isomer. In the past, MA was extracted from apple juice, which contains 0.4–0.7% of the acid [137]. Currently, MA is commercially obtained by catalytic hydration of oil-derived maleic or fumaric acid, which produces a racemic mixture of D- and L-isomers. Optically pure L-MA can be obtained through enzymatic conversion of FA by using fumarase [137]. However, economic sustainability of both strategies is limited since chemical synthesis requires harsh temperature and pressure, while an enzymatic process cannot operate at large scale. This has increased interest in fermentative production of MA, especially from sustainable and eco-friendly feedstocks such as lignocellulose [119].

Fermentative production of MA has been reported by using a number of native and recombinant hosts [119]. The most effective native MA producers comprise fungi belonging to Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Ustilago genera, which were able to generate up to 196 g/L MA, with yields up to 0.96 g/g. However, these organisms were mainly used to ferment glucose or glycerol feedstocks [119]. Successful examples of recombinant MA producers have been reported by using different microbial hosts, both eukaryotic (e.g., S. cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris, Torulopsis glabrata) and prokaryotic (e.g., E. coli, B. subtilis, Thermobifida fusca) [119]. So far, the highest MA yield was obtained through glucose fermentation by engineered Aspergillus niger that reached 201.13 g/L MA titer corresponding to 82% of the maximum theoretical yield (i.e., 1.49 g/g glucose) [138].

Significant MA production through direct fermentation of lignocellulose has been reported by metabolic engineering of the cellulolytic bacterium T. fusca [102] and fungus M. thermophila [60]. A T. fusca mutant obtained through adaptive evolution and showing slightly increased MA-accumulation [139] was used as host for this purpose. In this strain, MA biosynthesis mainly occurs by PEP conversion to oxalacetic acid through PEP carboxykinase (Pepck) instead of Pyc reaction (Figure 2) [102]. However, enhancement of MA accumulation was obtained by expressing a heterologous Pyc [102]. The engineered T. fusca strain produced the highest MA titer (62.76 g/L corresponding to 42% of the maximum theoretical yield) after 124 h of batch fermentation culture on 100 g/L of cellulose. Lower efficiency was reported by fermentation of 50 g/L milled corn stover (containing 36.9% of glucan and 19.3% of xylan), which generated 21.47 g/L of MA after five days. It is worth noting that low oxygen tension conditions were necessary for high MA production since this reduces NADH consumption through the respiration chain and NADH is instead available for malate dehydrogenase (Mdh) reaction [102].

Impressive enhancement (about 40-fold) of MA production was obtained by extensive engineering of the metabolism of M. thermophila [60], which included: (i) overexpression of a heterologous reductive pathway for MA biosynthesis and export (namely, Pyc, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, Pepc, Mdh, and a MA transporter); (ii) improvement of glucose uptake (by overexpressing a heterologous glucose transporter); iii) enhancement of cytosolic availability of CO2 (by overexpressing heterologous HCO3- transporter and carbonic anidrase) and; iv) elimination of parasitic pyruvate-consuming pathways (i.e., genes encoding Ldh, Pepck, and pyruvate decarboxylase) [60]. It is worth noting that Pepck reaction in M. thermophila is mainly directed towards formation of PEP instead of oxalacetate [60]. Engineered M. thermophila strains accumulated substantial amounts of MA, but also lower levels of SA. Batch fermentation of 75 g/L avicel generated 83.3 g/L MA (and 15.4 g/L SA), which corresponds to MA yield of 1.11 g/g (i.e., 75% of the theoretical maximum). Higher C4-diacid titers were obtained by fed-batch fermentation, namely, 181 g/L MA (and 19.7 g/L SA) from avicel (total C4-diacid yield = 1.1 g/g) and 105 g/L MA (and 5.4 g/L SA) from untreated corncob (containing 46.3% cellulose and 33.8% xylan, total C4-diacid yield = 0.4 g/g) [60]. It is worth noting that fed-batch fermentations were not performed with the final engineered M. thermophila, but with a strain that only expresses heterologous Pyc and MA transporter. It is therefore likely that further optimized strain could lead to higher MA (and SA) titers. However, this was the first study reporting production of bulk chemicals through CBP of plant biomass with a titer higher than 100 g/L.

2.2.3. Succinic Acid (SA)

Industrial application of SA encompasses the food, medicine, surfactant, and biodegradable plastic areas [12,140]. For instance, SA is the precursor of polyethylene succinate, a biodegradable polyester that is used as basic material in the plastic industry, and a general platform chemical for the synthesis of many commodity and specialty chemicals [12,140,141]. Traditional production of SA has been performed through chemical synthesis, but this is hampered by high production costs and serious environmental pollution issues [140]. This has stimulated research on biotechnological approaches to produce SA through environmentally-friendly process, namely on microbial fermentation of low cost biomass such as lignocellulose.

Most efficient natural producers of SA (up to 67 g/L) have been especially found among bacteria isolated from the rumen of ruminants (e.g., Actinobacillus succinogenes, Basfia succiniciproducens, Mannheimia succiniciproducens) [118,120]. Furthermore, SA overproduction has been engineered in several yeast/fungal (e.g., S. cerevisiae, Pichia kudriavzevii) and bacterial (e.g., E. coli, C. glutamicum) hosts by metabolic engineering [9,118].

So far, most studies addressed to SA generation by fermentation of lignocellulosic biomass have used traditional process configuration (namely SHF, SSF, and SSCF, Figure 1), while very few examples of CBP have been reported, as recently reviewed by Lu and coworkers [140]. Although it cannot exactly be considered a CBP, it is worth remembering the study by Alcantara et al. [142] that developed a fungal consortium (consisting of A. niger, T. reesei, and Phanerochaete chrysosporium) for fermentation of lignocellulosic feedstocks (soybean hulls and birch wood chips) to SA. Their approach consisted in separate solid-state fermentation of A. niger and T. reesei co-culture on soybean hulls and P. chrysosporium on wood chips followed by combination of these pre-cultures in a submerged system. In this fungal consortium, T. reesei and A. niger provided cellulase and hemicellulase activity, while P. chrysosporium was responsible for ligninolytic activity. Gaps of this study include that SA biosynthesizing strain(s) was not determined, and that a significant amount of SA (23 g/L) was accumulated at the pre-culture stage [142]. Batch-submerged fermentation generated a further 10 g/L SA, corresponding to a yield of 0.13 g/g substrate, in 72 h. Fedbatch fermentation (through addition of untreated birch wood chips) generated higher SA production (26 g/L), yield (0.24 g/g), and productivity (1.70 g/L/h) [142]. Recently, the development of the first bacterial consortium able to directly produce SA from hemicellulose-enriched lignocellulose has been reported, which consisted in hemicellulolytic Thermoanaerobacterium thermosaccharolyticum and SA-producing A. succinogenes [103]. After process optimization (which mainly concerned feedstock concentration, time of A. succinogenes inoculation, and amount of MgCO3 added serving for both pH regulation and release of CO2) use of this microbial consortium led to generation of 32.5 g/L SA from xylan (with a yield of 0.39 g/g, corresponding to about 49.6% of the theoretical maximum) and 12.5 g/L SA from 80 g/L untreated corn cob (with a yield corresponding to about 19.7% of theoretical maximum) (Table 2). Accumulation of significant amount of a number of by-products (such as acetic, butyric, formic and lactic acid) by these co-cultures is the reason for limited SA yield and need to be addressed, e.g., by metabolic engineering of these strains. In addition, SA productivity of this system was reduced by the limited efficiency of hemicellulose hydrolysis by T. thermosaccharolyticum M5 [103]. So far, the only example of CBP of lignocellulose components to SA by means of a single microorganism concerned fermentation of 3% xylan (and 1 % xylose, which is likely necessary to better support growth) by a E. coli strain secreting three heterologous hemicellulases and with improved SA production (through elimination of LA and formate production) [104]. This strain was able to generate 14.4 g/L SA without any external xylanase supplementation at a yield of 0.37 g/g, which is a value corresponding to 76% of the yield obtained through fermentation of xylan hydrolyzate (Table 2).

2.3. C5 Organic Acids

Itaconic Acid (IA)

IA (methylenesuccinic acid) is a bio-based platform chemical with multiple applications that range from polymer synthesis to biofuel production [34]. In addition, immunomodulatory and antimicrobial activity of IA has been reported [143]. Global IA production has been recently estimated at about 40,000 ton per year [144]. The current price (1.5–2.0 US$/kg) of IA makes it competitive with fossil-derived polyacrylic acid in the production of superabsorbent polymers [32,33]. However, a further reduction of IA price is necessary to access other bulk markets such as methyl methacrylate, which is currently produced from acetone cyanohydrin (about 1.0 US$/kg) [34].

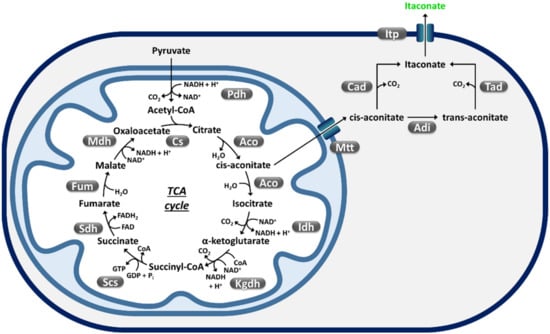

Two natural IA biosynthetic pathways are known, which slightly differ (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Native pathways for itaconic acid (indicated in green) biosynthesis [34,144]. The TCA cycle intermediate cis-aconitate is transported from the mitochondrion to the cytoplasm through the Mtt TCA carrier. In Aspergillus terreus, cytoplasmic cis-aconitate is directly decarboxylated to itaconate by cis-aconitate decarboxylase (Cad) and then secreted by Itp transporter. In Ustilago maydis, cis-aconitate is isomerized to trans-aconitate by aconitate-Δ-isomerase (Adi) and then decarboxylated by trans-aconitate decarboxylase (Tad) before been secreted. Aco, aconitase; Cs, citrate synthase; Fum, fumarase; Ich, isocitrate dehydrogenase; Kgdh, α-ketoglutatate dehydrogenase; Mdh, malate dehydrogenase; Pdh, pyruvate dehydrogenase; Scs, Succinyl-CoA synthetase; Sdh, Succinate dehydrogenase.

The filamentous fungus Aspergillus terreus biosynthesizes IA from decarboxylation of the Krebs cycle intermediate cis-aconitate by cis-aconitate decarboxylase (Cad) [145]. The yeast Ustilago maydis isomerizes cis-aconitate to trans-aconitate The yeast Ustilago maydis isomerizes cis-aconitate to trans-aconitate before decarboxylation by trans-aconitate decarboxylase (Tad) [146]. Currently, industrial production of IA is exclusively obtained through fermentation of glucose or simple sugars by A. terreus [147]. At the laboratory fermentation scale, this fungus can achieve 160 g/L IA titer and 1.9 g/L/h volumetric productivity [148]. Lower efficiencies (maximum IA titer = 80–100 g/L) are typically obtained at the industrial scale [149], likely because of A. terreus high sensitivity to impurities (e.g., trace amounts of Mn2+) [150], which are frequently present in industrial media [145,151]. Both A. terreus and U. maydis naturally produce biomass-hydrolyzing enzymes [152,153,154]; however, their cellulase activity is far too low for efficient IA production from cellulose [34]. Production of IA through traditional fermentation (namely SHF, SSF) of lignocellulosic feedstocks using A. terreus has been reported by a number of studies, as recently reviewed by Schlembach et al. [34]. However, these investigations have highlighted a number of issues related to the use of A. terreus for producing IA from lignocellulose such as the need for high initial sugar concentration and A. terreus low tolerance to manganese, which can be found among impurities of cellulosic feedstocks [150,155,156]. Attempts to improve the biomass hydrolyzing activity of U. maydis through deregulation of expression of its hydrolase enzyme repertoire [105] or by expressing heterologous enzymes [157] have been reported. These studies led to enhancement of hydrolysis of polygalacturonic acid (a major component of pectin) [157], xylan, cellobiose, carboxymethyl cellulose and regenerated amorphous cellulose [105], although increased IA generation (5 g/L) was reported only on cellobiose (Table 2).

As regards engineering IA biosynthesis in non-native hosts, the most successful studies have been focused on the citric acid producer and A. terreus-closely related A. niger [158,159,160]. It is worth noting that, although strong (about 200 g/L) production of citrate (a metabolic precursor of cis-aconitic acid and IA) of A. niger, expression of A. terreus cis-aconitate decarboxylase resulted in accumulation of only 0.05 g/L of IA [158]. Multiple metabolic engineering modifications (including overexpression of cytosolic citrate synthase and citrate liase, mitochondrial transporter for cis-aconitic acid, and cytoplasmic membrane transporter for IA) and optimization of the growth medium were necessary to increase A. niger titer of IA up to 42.7 g/L [159]. As regards engineering IA production in a native cellulolytic microorganism, a recent study has been addressed to the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa [106]. Codon optimized gene encoding A. terreus Cad was expressed in N. crassa under the control of a strong promoter. Nonetheless, very low IA concentration (0.02 g/L) was generated from 20 g/L avicel (Table 2) and even lower IA amounts were accumulated by fermentation of more complex lignocellulosic feedstocks (i.e., corn stover and switchgrass). Further substantial engineering of the N. crassa metabolism as well as culture process optimization is therefore necessary to improve IA production of this strain to significant levels. This investigation confirmed that efficient cellulase activity able to provide high glucose flux to the central metabolism is a key factor for high IA accumulation. In this perspective, engineering IA production in more robust cellulolytic microorganism such as T. reesei could have higher potential [106]. IA production in bacteria is challenging because IA disrupts bacterial growth via inhibition of enzymes in the glyoxylate shunt [161] and citramalate cycle [162]. However, examples of IA production engineering in prokaryotic models such as E. coli [163] and C. glutamicum [164] have been reported. This suggests that it would be worth including efficient cellulolytic bacteria such as Clostridium thermocellum [5] among the suitable microbial hosts for IA generation from plant biomass. In addition, a very recent study has demonstrated feasibility of bioconversion of depolymerized lignin into IA [107]. Lignin monomers are small aromatic molecules (e.g., p-coumarate, coniferyl alcohol), which can be metabolized by a number of microorganisms through different metabolic pathways that generate common central metabolism intermediates (e.g., pyruvate, acetyl-CoA) [165]. For IA production, Pseudomonas putida KT2440 was chosen, which expresses the β-ketoadipate route, i.e., converts aromatic compounds to acetyl-CoA and succinate [107,165] (Figure 4). This study provided a number of metabolic engineering hints for enhancing IA biosynthesis that could be suitable also for other microbial models: (i) utilization of the U. maydis trans-pathway instead of the A. terreus cis-pathway for IA biosynthesis (Figure 3) as a more thermodynamically favorable route to divert TCA cycle carbon intermediates; (ii) utilization of regulatable expression system for IA pathway genes able to uncouple microbial growth and IA production; (iii) down-regulation of the expression of TCA cycle genes such as isocitrate dehydrogenase leading to accumulation of cis-aconitic acid [107]. This study led to impressive IA yield (0.79 g/g, which may be overestimated since it was calculated only based on detectable aromatic monomers) from alkali pretreated corn stover lignin (Table 2). As low substrate amounts were used, low IA titer (1.43 g/L) was obtained, which could possibly be enhanced by optimized feeding strategy.

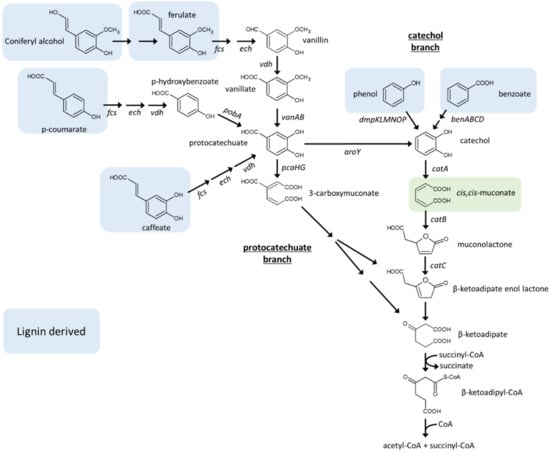

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the protocatechuate (left) and catechol (right) branches of the β-ketoadipate pathway, which funnels different lignin-derived aromatic compounds (highlighted in blue) to β-ketoadipate and, eventually, to the TCA cycle intermediates acetyl-CoA and succinate [165,167]. cis,cis-muconate (highlighted in green) is an intermediate of the catechol branch, which is obtained through catechol oxidation catalyzed by catechol 1,2-dioxygenase. aroY, protocatechuate decarboxylase; benABC, benzoate dioxygenase; benD, dihydroxybenzoate dehydrogenase; catA, catechol 1,2-dioxygenase; catB, muconate cycloisomerase; catC, muconolactone D-isomerase; dmpKLMNOP, phenol hydroxylase; ech, enoyl–CoA hydratase/aldolase; fcs, feruloyl–CoA synthetase; pcaHG, protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase; pobA, p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase; vanAB, vanillate O-demethylase; vdh, vanillin dehydrogenase.

Recently, a microbial consortium for CBP of α-cellulose to IA has been established by co-culturing the cellulolytic fungus T. reesei RUT-C30 with engineered IA-hyperproducing U. maydis [34]. A recombinant U. maydis strain was used that lacks the gene encoding itaconate oxidase (cyp3) and the gene fuz7, which is involved in regulating morphology and pathogenicity (thus improving strain handling), and overexpresses the genes encoding the transcriptional regulator Ria1 and the mitochondrial transporter MttA [166]. This study indicated that substrate availability was a key factor for inducing IA production. Actually, U. maydis was able to grow and generate IA only at high cellulose concentration, hence at high sugar supply rate. The most efficient system for IA production from cellulose by means of this microbial consortium was by fed-batch fermentation, which resulted in a IA titer of 34 g/L, with a total productivity of up to 0.07 g/L/h and a yield of 0.16 g/g (i.e., 22% of the theoretical maximum) (Table 2).

2.4. C6 Organic Acids

Adipic Acid (AA), cis,cis-Muconic Acid (CCM), Glucaric Acid (GA)

Adipic acid (AA) is considered the most commercially important dicarboxylic acid [168]. Global annual production of AA is about three million tons, corresponding to market value of almost US$ six billion, which is growing at 3–5% per year (Table 1). AA is mainly used for the production of nylon. Other AA applications include plasticizers, polyurethanes, food, and pharmaceutical industries [23]. Current production of AA is based on petrochemical precursors, generally benzene [169]. During this chemical process, nitrous oxide (N2O) is formed, which has a 300 times stronger greenhouse effect than CO2. Replacement of such a process with a bio-based one would therefore have substantial benefits on reduction of oil consumption, manipulation of hazardous compounds, and release of greenhouse gas emissions [170,171].

Fermentative production of AA may occur through a direct or indirect process. Unfortunately, no natural strong producer of AA has been isolated so far [23]. Hence, a number of recombinant metabolic pathways have been designed that generally led to low yields and titers, except for processes based on palm oil or glycerol (reviewed by Skoog et al. [23]). Interestingly, the cellulolytic bacterium T. fusca has been reported to possess a pathway for AA biosynthesis based on reverse AA degradation pathway [108]. However, very low AA amounts are accumulated by this microorganism. More in detail, 0.06 and 0.22 g/L AA were generated by fermentation of avicel and milled corn cob, respectively (Table 2). These titers correspond to a yield of about 1.5 % of the theoretical maximum that can be obtained from glucose through reverse AA degradation pathway (i.e., 0.75 g/g) [23]. Based on existing metabolic engineering tools for T. fusca [102], it would be worth trying to enhance AA production in this bacterium. Some research in this direction has recently been reported since site-directed mutagenesis of adipyl-CoA synthetase (catalyzing the last reaction of the reverse AA degradation pathway, i.e., adipyl-CoA + ADP + Pi → AA + CoA + ATP) had beneficial effect on both enzyme activity and AA production [172].

In indirect biotechnological processes for AA production, cis,cis-muconic acid (CCM) or glucaric acid (GA) are generated by fermentation. These acids are then chemically hydrogenated to AA [173]. As regards production of CCM from lignocellulose, although several studies have reported fermentation of glucose or xylose to CCM through engineered shikimate pathway (reviewed in [167]), the strategies involving the least extensive metabolic engineering and the highest theoretical yield are those targeting lignin hydrolyzates. Microorganisms harboring the β-ketoadipate pathway can funnel a number of lignin-derived aromatic monomers (e.g., benzoate, caffeic acid, p-coumarate, coniferyl alcohol, phenol) to either protocatechuate or catechol, which are further oxidized to acetyl-CoA and succinate (Figure 4). CCM is generated in the catechol branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway through oxidation of catechol catalyzed by catechol 1,2-dioxygenase [174].

A number of examples of fermentation of lignin hydrolizates or lignin monomers to CCM have been reported that employ different microbial strains such as Amycolatopsis sp., Arthrobacter sp., E. coli, C. glutamicum, P. putida, S. cerevisiae, and Sphingobium sp. (reviewed in [167]). Most of these studies were based on engineering microorganisms that naturally harbor a β-ketoadipate pathway such as P. putida and C. glutamicum. The key metabolic modification for enhancing CCM accumulation in these strains was eliminating muconate cycloisomerase (CatB), which catalyzes conversion of CCM to muconolactone (Figure 4) [110,111,175]. However, this modification implies that aromatic compounds can no longer support growth of these recombinant strains, hence, additional carbon source (e.g., glucose, acetate) is needed. Furthermore, catechol may accumulate in these strains, which is intrinsically toxic because of its involvement in the production of reactive oxygen species and direct protein damage [176,177]. For avoiding catechol accumulation, overexpression of the catA gene(s) encoding catechol 1,2-dioxygenase (Figure 4) has been generally performed by replacing the original promoter with stronger one [110,111,175]. Given the complexity of the aromatic compound mixtures generated by lignin depolymerization, expanding the substrate panel of microbial hosts can be considered as another general strategy for enabling efficient bioconversion of lignin streams to CCM. For instance, P. putida KT2440 was equipped with the genes encoding phenol hydroxylase [110,175]. In addition, replacement of protocatechuate 3,4 dioxygenase (PcaHG, protocatechuate + O2 → 3-carboxymuconate) with heterologous protocatechuate decarboxylase (AroY, protocatechuate → catechol + CO2) provided channeling of all the substrates recognized by this strain to catechol and, eventually, CCM (Figure 4) [175,178]. The latter modification is valuable especially in the perspective to valorize compounds such as p-hydroxybenzoate and vanillate, which are generated under milder lignin depolymerization conditions (Figure 4) [179,180]. Strain and process engineering resulted in efficient accumulation of CCM from lignin model monomers such as catechol, benzoate, and phenol with about 100% theoretical molar yield (calculated only based on aromatic substrates and not additional carbon sources for growth) [110,111,181]. So far, the highest CCM titer was obtained by using a recombinant C. glutamicum (lacking muconate cycloisomerase, CatB, and constitutively overexpressing catechol 1,2-dioxygenase, CatA), which generated 85 g/L CCM in a 60 h fermentation process fed with catechol pulses, at a maximum volumetric productivity of 2.4 g/L/h [111]. However, fermentation of lignin hydrolyzates (with this and other recombinant microorganisms) proved to be more challenging and CCM titers from these feedstocks were far lower (i.e., 2–13 g/L, Table 2) [109]. So far, the highest CCM titer (13 g/L, at a productivity of 0.24 g/L/h) produced through fermentation of depolymerized lignin was obtained by using an engineered P. putida KT2440 strain [110]. This strain was obtained by disruption of genes encoding muconate cycloisomerase (catB), muconolactone D-isomerase (catC), strong expression of both native catechol 1,2-dioxygenase under the native cat promoter, and overexpression of P. putida CF600 phenol hydroxylase (dmpKLMNOP) [110].

Improving the efficiency of these processes towards industrially relevant yield, titer, and productivity will certainly require further optimization at several levels, namely lignin pre-treatment processes, microbial strains, and fermentation strategies. In fact, different lignin pretreatment technologies lead to significantly different degrees of lignin deconstruction and aromatic monomer spectrum [178,182]. Furthermore, lignin-rich streams such as alkaline pretreated liquor also contain high concentration of acetate and other carboxylic acids [180,183], which may serve as additional carbon sources (thus supporting CCM production) or carbon catabolite repressors depending on the microbial strain [184]. Bioconversion of certain lignin-derived aromatic monomer(s) may specifically be affected by toxicity, carbon catabolite repression, or product inhibition of pathway enzyme(s) [109,110]. In addition, high amounts of CCM (≥50 g/L) may be toxic for microorganisms [109]. A combination of further strain and fermentation process improvement appears necessary to overcome these issues.

Interestingly, recent reports of enzymatic conversion of CCM to AA by a number of bacterial enoate reductases open the prospect to produce AA through direct fermentation of lignin [185]. Introduction of heterologous enoate reductases in S. cerevisiae and E. coli enabled direct fermentation of glucose to AA (through engineered shikimate pathway), although, so far, with very low titers (≤ 0.03 g/L) [186,187].

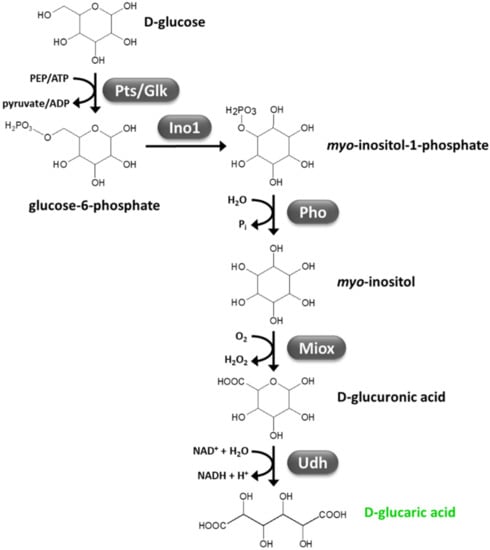

A synthetic pathway was engineered in E. coli and S. cerevisiae, which enabled GA biosynthesis from glucose [23,188]. This pathway is based on expression of heterologous myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase (Ino1, glucose-6-phosphate → myo-inositol-1-phosphate), myo-inositol oxygenase (Miox, myo-inositol + O2 → glucuronic acid + H2O), and uronate dehydrogenase (Udh, glucuronic acid + NAD+ + H2O → GA + NADH + H+) (Figure 5). Despite a number of improvements of culture conditions and stability and efficiency of Miox (that was found to be among the rate-limiting step of the GA synthetic pathway), GA titers above 5 g/L could not be obtained by means of E. coli, so far, likely because of GA inhibitory effects on E. coli growth [112]. Higher GA titers (up to 11.21 g/L) have been obtained through engineered S. cerevisiae, which is known to be more acid tolerant [112]. However, since myo-inositol availability is another limiting step of GA synthetic pathway, myo-inositol supplementation in the growth medium (in addition to glucose) is necessary for efficient generation of GA [112]. Very recently, a proof-of-concept of CBP of lignocellulosic feedstocks to GA has been reported, which is based on an artificial consortium consisting of the cellulolytic fungus T. reesei and GA-overproducing S. cerevisiae [112]. Since S. cerevisiae expresses its own Ino1, only heterologous Miox and Udh were introduced to complete GA biosynthetic pathway in this microorganism. Nonetheless, deletion of opi1 gene was necessary to relieve its negative regulation on myo-inositol biosynthesis. Co-culture of this strain with T. reesei led to generation of 0.54 and 0.45 g/L GA through direct fermentation of avicel and steam-exploded corn stover, respectively [112]. Although the low titer, yield, and productivity obtained, this study was the first reporting GA generation from lignocellulose.

Figure 5.

Synthetic pathway for D-glucaric acid production from glucose (adapted from [23,112]). Glk, glucokinase; Ino1, myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase; Miox, myo-inositol oxygenase; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Pho, phosphatase; Pts, phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase; Udh, uronate dehydrogenase.

3. Improvement of Acid Tolerance

Fermentative production of organic acids is inherently affected by acidic pH stress on cells, which causes growth inhibition and decreases organic acid productivity and titer [73,77]. Acidic pH in the growth medium causes dissipation of the proton gradient (∆pH) across the cytoplasmic membrane and protonation of weak acids, which enhances their passive diffusion into the cell. Since cytosol is more alkaline, weak acids can then dissociate and further collapse the ∆pH [189]. Acidification of intracellular pH may generate several types of cell damage such as enzyme denaturation, alteration of nutrient uptake, cytoplasmic membrane damage, depurination and depyrimidination of DNA, and dissipation of amino acid pools [190]. Traditionally, acidification during fermentative processes has been neutralized by base addition. However, this increases downstream purification costs that may account for >50% of the total product cost [70]. Systems for continuous removal of organic acids (e.g., electrodialysis, solvent extraction, adsorption, and membrane bioreactors) raise the complexity and cost of the whole process [72,73,191]. Utilization of acid tolerant hosts is therefore crucial for improving fermentative production of organic acids, especially for obtaining high titers. Ideally, a microbial host should tolerate pH conditions around the pKa(s) (typically in the range 3–5 for organic acids) of the produced acid [23].

As regards to acid tolerance, S. cerevisiae and other yeasts (e.g., Candida lignohabitans) show significant advantage with respect to other microbes since they can grow at pH 1.5–2.5 [192,193,194]. Native LA producers (such as LAB and R. oryzae) generally tolerate milder acidic conditions (pH 4.0–4.5), although some LAB strains able to grow at pH 3.2 have been reported [195,196]. Typically, native cellulolytic anaerobic bacteria such as C. thermocellum, C. cellulovorans, and F. succinogenes cannot grow at pH values ≤ 6.0 [189,197,198], although much broader pH range for growth (4–10) has been reported for the aerobic cellulolytic bacterium T. fusca [102]. Acid tolerance relies on several cellular mechanisms that contribute to pH homeostasis such as: (i) proton-extruding transporters; (ii) proton-consuming cytosolic reactions; (iii) modification of membrane fluidity/permeability [199]. Proton extrusion from cells is catalyzed by multiple membrane transporters such as primary proton pumps (e.g., F1F0-ATPase, PPi-ase) and cation exchangers (e.g., Na+/H+, K+/H+ antiporters) [189,200,201]. Cytosolic proton-consuming reactions have been identified in several microorganisms such as LAB, E. coli, and Helicobacter pylori and include urease reaction (urea + 2 H+ + H2O → 2 NH4+ + CO2) [202], arginine deiminase pathway (arginine + H+ +ADP + Pi → ornithine + 2 NH4+ + CO2 + ATP), amino acid decarboxylation (amino acid + H+ → amine + CO2), and malolactic fermentation (MA + H+ → LA + CO2) [203]. Mechanisms for modulating cytoplasmic membrane fluidity/permeability include modification of lipid composition such as length and degree of unsaturation of fatty acids, ratio of cis/trans unsaturated fatty acids, presence of branched chain, and/or cyclopropane fatty acids [199,204]. In addition, protein chaperones (e.g., HdeAB, DnaKJ, GrpE, GroELS) and DNA repair systems (e.g., RecA, RecO, UvrABCD) are used by acid-challenged microorganisms to alleviate toxic effects such as protein denaturation and DNA damages (e.g., abasic sites), respectively [190,199,205].

It is worth noting that microorganisms can show varying degrees of tolerance to different organic acids [99,194]. In fact, the decrease in intracellular pH likely does not totally explain carboxylic acid inhibitory effects on microorganisms, which depend on multiple chemical properties of these compounds, such as their pKa, hydrophobicity, and volatility [206,207]. For instance, acetic acid inhibited S. cerevisiae growth at lower concentration (6 g/L) than LA (25 g/L) [208]. This observation was attributed to the fact that at a fixed pH, a larger fraction of acetic acid (pKa = 4.756) in undissociated with respect to LA (pKa = 3.86) and can passively diffuse into cells. However, C. thermocellum growth is completely inhibited by 20–25 g/L LA, while with 20 g/L acetic acid only 25% reduction of biomass production was observed [54]. This exemplifies the fact that tolerance to organic acids is also dependent on microbial strains and culture conditions [207]. However, systematic studies have generally observed an increase of toxicity for more hydrophobic carboxylic acids, similar to what was observed on solvents [207,209].

Enhancement of acid tolerance of a number of microorganisms has been obtained through different approaches, such as chemical mutagenesis [198], genome shuffling [210,211], adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) [190,212], multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) [213], rational metabolic engineering [214,215], or combination of these strategies [198,216] (Table 3). Improved acid tolerance has been differently evaluated and quantified, for instance through survival at extreme pH (e.g., pH 2.5–3.0), or ability to grow/survive at more acidic pH than the wild-type strain, or increased growth rate and/or biomass production at moderately acidic pH or in presence of challenging concentration of organic acid. This makes it difficult to compare the effectiveness of these different strategies. As regards their ability to lower pH limit allowing growth of a microorganism, no study reported so far was able to go beyond 0.5 pH unit, irrespective from the strategy (strain evolution/engineering) used [198,210,216,217,218]. Results seem somehow more promising as regards to the ability of these studies to improve tolerance towards an organic acid. From this perspective, development of S. cerevisiae [219], L. mesenteroides [190], and C. thermocellum [98] strains able to tolerate high (35–70 g/L) LA concentration and A. pasteurianus [220] strain with increased resistance to 60 g/L acetic acid seems noteworthy. Interestingly, enhancement of organic acid production (mainly LA) following improvement of acid tolerance has been reported by a number of studies [190,205,210,219,221], although this does not apply to all the paradigms [99].

Table 3.

Some metabolic engineering strategies used for improving acid tolerance in microorganisms. ALE, adaptive laboratory evolution; CM, chemical mutagenesis; MAGE, multiplex automated genome engineering; GS, genome shuffling; RAISE, Random insertional-deletional strand exchange mutagenesis; RME, rational metabolic engineering.

Currently, a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying acid tolerance in microorganisms seems essential to design effective metabolic engineering strategies able to develop microbial strains with superior acid tolerance for industrial production of organic acids. As acid tolerance is a complex polygenic trait, it appears unlikely that significant improvement may be obtained by one/few gene modification. Apart from genome-wide evolution/engineering, strategies targeting general gene regulators such as RNA polymerase sigma factors seem to have high potential [222]. Among the multiple sigma factors generally present in microorganisms [223], with regards to acid stress, attention has mainly been focused on σS (encoded by rpoS gene) and σ70 (encoded by rpoD gene). The sigma factor σS is commonly associated with stationary phase physiology; however, it has also been shown to be essential for response to acid stress during exponential growth phase [224,225]. In this condition, σS levels are enhanced, which in turn promotes transcription of a number of genes involved in acid tolerance mechanisms such as gadC (encoding glutamate decarboxylase), hdeAB (encoding pH-regulated periplasmic chaperones), and cfa (involved in cyclopropane fatty acid synthesis, hence in modulation of membrane fluidity) [225,226]. The main vegetative sigma factor σ70 controls the expression of most genes required during exponential growth [223], but may partially replace σS under many stress conditions [222]. In addition, the role of small non-coding RNAs (sRNAs) and RNA chaperones in microbial response to a number of stresses has been receiving increasing attention [227].

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Production of organic acids through second generation biorefining represents a significant opportunity to reduce the global economy’s dependence on oil reserves and greenhouse gas emissions and increase production of eco-friendly materials such as biodegradable plastics (e.g., PLA, PMA). Proof-of-concept of CBP converting lignocellulose feedstocks to most of the top value organic acids indicated by a 2004 report of the US Department of Energy [10,11] was reported. Still, most of these studies are far from meeting industrial requirements for economically sustainable production, that is 50–100 g/L titer, 1–3 g/L/h productivity, and >0.5 g/g yield [70,71]. Currently, the most mature technology refers to MA production, since about 180 g/L (yield ≈1.1 g/g) and 105 g/L (yield ≈0.4 g/g) was obtained by direct fed-batch fermentation of crystalline cellulose and corn cob, respectively, by engineered fungus M. thermophila (Table 2) [60]. Remarkable MA accumulation was also obtained through metabolic engineering of the cellulolytic bacterium T. fusca (Table 2) [102]. Based on much more limited modification that was performed so far on T. fusca metabolism (with respect to M. thermophila), further improvement of T. fusca performances as MA producer seems achievable. Concerning MA production from lignocellulosic feedstocks in general, further improvement of MA yields on more complex feedstocks (e.g., by eliminating additional fermentation product such as SA) and productivity is required.

Advances in LA, SA, and IA production from lignocellulose are far behind, with maximum titers that range around 30–35 g/L for fermentation of laboratory substrates (cellulose or xylan) and are dramatically diminished (12–20 g/L) on more complex feedstocks such as corn cob or beech wood [34,41,103] (Table 2). The greatest progress obtained so far refers to use of artificial bacterial, fungal, or mixed bacterial-fungal consortia [34,41,103]. This encourages further studies in this direction. Within this framework, it would be advantageous to include cellulolytic (instead of or in addition to hemicellulolytic) partners in future design of synthetic microbial consortia for SA production. However, it should also be remembered that in consortia consisting of lignocellulose depolymerizing specialist(s) and valuable compound-producing microorganism(s), sugars required for the growth of the (hemi)cellulolytic strain(s) reduce high-value chemical production. As regards RCS strategy, despite the significant effort produced, engineering native LA producers with recombinant cellulase systems yet seems extremely challenging (Table 2). Although native IA producers include some cellulase-producing strains (e.g., U. maydis), enhancing the cellulolytic efficiency of these strains was not much more successful (Table 2). Improving organic acid biosynthesis in native (hemi)cellulolytic microorganisms (e.g., T. reesei, C. thermocellum) is a largely unexplored area that deserves great interest owing to the growing number of strains for which gene manipulation tools are available. A major drawback of this approach is that a number of cellulolytic microorganisms (mainly anaerobic bacteria) show low acid tolerance.

Also, as regards direct generation of FA from lignocellulose fermentation, the main progress obtained so far refers to use of artificial microbial consortia [43]. However, based on current FA titer, yield, and productivity, this can be considered simply as a proof-of-concept and significant process optimization is required. Engineering FA production in the cellulolytic fungus M. thermophila seems a promising alternative [133] on the basis of availability of efficient gene tools for this microorganism and results obtained on production of other C4 dicarboxylic acids [60].

Because of its high recalcitrance, lignin is typically removed through biomass pretreatment. However, valorizing also this fraction (that is the second most abundant biopolymer after cellulose) is critical for the economic viability of lignocellulosic biorefineries [107]. Evidence of production of AA, the most commercially important organic acid, and IA (which could serve as paradigm for engineering production of other dicarboxylic acids) from lignin hydrolyzates has been reported [107,110]. Owing to the high complexity of lignin, extensive research will be necessary to optimize lignin depolymerization treatments, microbial strains, and fermentation process towards efficient production of high-value organic acids and other chemicals. As regards strain engineering, this should address improvement of both organic acid production from heterogeneous mixtures generated by lignin pre-treatment and tolerance to aromatic compounds and fermentation products (e.g., CCM). In addition, the native cellulolytic bacterium (T. fusca) has been reported to naturally accumulate AA, although in low amounts [108]. Based on available gene manipulation tools for T. fusca, it would be worth making full use of metabolic engineering to improve AA biosynthesis from cellulose in this organism. Very recently, the first demonstration of direct fermentation of lignocellulosic feedstocks to AA-precursor GA (through synthetic microbial consortium of T. reesei and GA-accumulating S. cerevisiae) has been reported [112]. This study contributes to expanding biotechnological strategies towards AA production from renewable biomass.

Currently available reports indicate that improving acid tolerance of a microorganism is challenging. This appears consistent with the multi-genetic trait and multiple molecular mechanisms underlying this phenotype. No study reported so far was able to lower the pH limit for growth over 0.5 pH unit regardless of the experimental approach used (Table 3). Results obtained on enhancement of tolerance towards organic acids (e.g., strains able to tolerate up to 70 g/L LA, Table 3) seem to have higher potential for improving fermentation processes. Based on importance of acid tolerance for fermentative production of organic acids, research efforts in this direction should be strongly encouraged. First of all, more detailed information on the mechanisms enabling microorganisms to tolerate and adapt to acidic pH conditions is necessary. Improved understanding will strongly contribute to more rational engineering of acid tolerant microorganisms.

In a larger perspective, additional strategies for developing CBP of lignocellulose to organic acids should be remembered. Studies aimed at endowing cellulolytic ability in E. coli [235,236] and yeasts such as K. marxianus [64,237], S. cerevisiae [47,238], and Y. lipolytica [53,239] are among the most cutting edge paradigms of RCS. Furthermore, owing to their high genetic tractability (E. coli) and/or acid tolerance (yeasts), production of organic acids (e.g., LA, MA, SA, FA) has been enhanced in a number of these microorganisms [240,241,242]. So far, these two research areas have had little overlap, since most research on recombinant cellulolytic yeasts/E. coli have been targeted to production of ethanol or other fuels, while feedstocks for organic acid production by engineered yeasts/E. coli generally were simple sugars or glycerol. However, combining cellulolytic and organic acid overproducing characteristics in a single yeast/E. coli strain seems feasible as demonstrated by the xylan-depolymerizing SA-accumulating E. coli strain engineered by Zheng and coworkers [104]. Alternatively, artificial consortia comprising lignocellulose depolymerizing microorganism(s) and recombinant organic acid-overproducing yeast/E. coli could be designed, as recently demonstrated by Li and coworkers [112]. Furthermore, it is worth remembering the potential of lignocellulosic feedstock fermentation strategies based on natural lignocellulose-degrading microbial communities such as the microbiota of herbivore rumen or termite gut [65,66,67]. Managing the complexity of these microbial consortia in terms of consortium composition and interactions among symbionts currently seems challenging, although proof-of-concept of lignocellulose fermentation to mixtures of short chain organic acids (e.g., LA, SA) has been reported [65,66,67]. In general, taking advantage of these natural microbial communities as a reservoir of enzymes and microorganisms with improved characteristics seems desirable also in relation to safety issues and limitations associated with the use of genetically modified organisms [243].

Funding

This research was funded by Ricerca Locale (ex 60%) 2021 funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sims, R.E.H.; Mabee, W.; Saddler, J.N.; Taylor, M. An overview of second generation biofuel technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1570–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.A.; Zhao, L.; Emptage, M. Bioethanol. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss, P.; Gardner, K.H. Attributional life cycle assessment (ALCA) of polyitaconic acid production from northeast US softwood biomass. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Sugar Organization. International Sugar Organization Daily Sugar Prices. Available online: https://www.isosugar.org/prices.php (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Mazzoli, R.; Olson, D.G. Clostridium thermocellum: A microbial platform for high-value chemical production from lignocellulose. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 113, 111–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lynd, L.R. The grand challenge of cellulosic biofuels. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazzoli, R. Metabolic engineering strategies for consolidated production of lactic acid from lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2020, 67, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, J.M.; Alkim, C.; Morin, N. Engineering microbial pathways for production of bio-based chemicals from lignocellulosic sugars: Current status and perspectives. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Gong, M.; Lv, X.; Huang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Current advance in biological production of short-chain organic acid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 9109–9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werpy, T.; Petersen, G. Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass, Volume I: Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozell, J.J.; Petersen, G.R. Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates—the US Department of Energy’s “top 10” revisited. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, M.; Porro, D.; Mattanovich, D.; Branduardi, P. Microbial production of organic acids: Expanding the markets. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Precedence Research Biofuels Market Size Worth Around US$307.01 billion by 2030. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2021/01/22/2162581/0/en/Biofuels-Market-Size-Worth-Around-US-307-01-Billion-by-2030.html (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- MarketStudy Global Adipic Acid Market Research Report 2020—Market Study Report. Available online: https://www.marketstudyreport.com/reports/global-adipic-acid-market-research-report-2020?gclid=Cj0KCQjw6s2IBhCnARIsAP8RfAgKz8fqb3GzGMqUAeSsabN9dUFoteDvrE6hHowwfb6McXQ2nvLwEYsaAhRrEALw_wcB (accessed on 11 August 2021).