Abstract

Agave bagasse is a lignocellulosic residue generated after the extraction of fermentable sugars from agave hearts during tequila production. More than 0.5 million tons are generated annually, accumulating on a massive scale and posing a serious environmental challenge. In this regard, the objective of this study was to evaluate the degradative capacity of Trametes versicolor (Tv), Trametes hirsuta (Th), Irpex lacteus (Il), and Schizophyllum commune (Sc) on Agave tequilana Weber variety azul bagasse through the analysis of total sugars, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin reduction in a solid-static treatment. Under sterile conditions, Tv reduced total sugars by 95.0%, Th by 89.5%, Il by 91.8%, and Sc by 74.6%; whereas under non-sterile conditions, reductions were 81.6%, 71.4%, 84.9%, and 64.7%, respectively. Regarding structural fractions under sterile conditions, Tv showed reductions of 67.8% in cellulose, 61.9% in hemicellulose, and 68.8% in lignin. Th achieved 62.8%, 58.8%, and 66.1%, respectively; Il exhibited the highest values, with 72.9%, 66.9%, and 74.6%; while Sc recorded 55.9%, 44.2%, and 61.0%. In contrast, reductions were lower under non-sterile conditions: Tv recorded 57.8%, 34.2%, and 62.2%; Th, 53.9%, 32.1%, and 59.6%; Il, 58.8%, 47.1%, and 64.7%; and Sc, 49.9%, 30.0%, and 56.5%. Overall, sterile substrate conditions maximized lignocellulosic degradation; however, the sustained activity observed under non-sterile conditions demonstrates that effective biological pretreatment can be achieved without sterilization, which is more relevant for large-scale solid-state fermentation. The results demonstrate that T. versicolor and I. lacteus possess high potential as biological pretreatment agents by accelerating the depolymerization of the lignocellulosic matrix. This effect could reduce composting times and enable applications that favor its inclusion in circular economy frameworks.

1. Introduction

Agave bagasse is a lignocellulosic fibrous byproduct resulting from the crushing, cooking, milling, and extraction of fermentable sugars from the hearts of Agave tequilana Weber var. azul during tequila production [1]. This residue accounts for approximately 40% of the total wet weight of the processed agave [2]. Given that tequila production reached 598.7 million liters in 2023, the industry generated an estimated 0.9 to 1.67 million tons of bagasse [3].

The accumulation and inadequate management of this waste pose severe environmental threats. Open-air burning remains a persistent practice; the combustion of a single ton of bagasse is estimated to release 0.5 to 0.6 tons of CO2-eq, considering both direct CO2 and associated CH4 and N2O emissions [3,4,5]. Additionally, logistics for disposal or composting contribute a further 0.15 to 0.25 tons of CO2-eq per ton due to transportation [6]. Furthermore, landfilling results in the generation of leachates high in phenolic compounds, organic matter, and residual sugars, which can lead to the eutrophication of surface water bodies or the contamination of aquifers through infiltration [7].

From a social perspective, communities in the vicinity of distilleries and disposal sites have reported malodors, insect proliferation, water contamination, and landscape degradation [8]. Regarding the regulatory framework in Mexico, the General Law for the Prevention and Integral Management of Waste (LGPGIR) classify bagasse as a special management waste, delegating its oversight to state authorities. This results in fragmented enforcement and low levels of inspection [9]. Its management is governed by non-specific standards—NOM-052-SEMARNAT-2005 [10] and NOM-004-SEMARNAT-2002 [11]—applied according to its intended use or final destination. However, their efficacy remains low due to limited supervision and the persistence of informal dumping practices. Furthermore, subsidies for bioproducts or valorization technologies have yet to be consolidated, despite certain state-level composting initiatives [3,6,12].

While bagasse has been utilized as livestock feed, boiler fuel, or in biofuel production [2], these applications remain marginal relative to the total production volumes. Consequently, composting emerges as the most viable valorization option, though the process requires between 180 and 300 days [13] and can generate between two and six kg of CH4 per ton of wet material [14]. Anaerobic digestion has also been explored as a potential valorization pathway for agave bagasse, particularly for biogas production. However, its application remains limited due to the high lignin content, the presence of phenolic compounds, and the low biodegradability of the lignocellulosic matrix, which often result in low methane yields unless effective pretreatment strategies are applied [2].

The recalcitrance (slow degradation) of agave bagasse is attributed to its high content of cellulose (44%), hemicellulose (25%), and lignin (20%) [7], as well as the dense association between lignin and structural carbohydrates. This forms a lignocellulosic matrix that restricts enzymatic access and subsequent depolymerization [15].

Lignocellulosic materials can be hydrolyzed through physical and chemical methods; however, these approaches are often costly, energy-intensive, and unfeasible for large-scale applications [16]. Given these limitations, biological pretreatments based on lignocellulolytic fungi have gained increasing attention as low-energy and environmentally sustainable alternatives for lignocellulosic biomass valorization. Studies on agro-industrial residues such as sugarcane bagasse, corn stover, wheat straw, and rice straw have reported lignin reductions ranging from 20% to over 50%, accompanied by significant improvements in enzymatic accessibility and downstream bioconversion efficiency following fungal pretreatment [17]. For example, Adedayo-Fasiku et al. [18] reported a 38.99% reduction in lignin in corn stover using L. squarrosulus, while Pamidipati and Ahmed [19] observed a 42% reduction in sugarcane bagasse with N. discreta.

In contrast to controlled biological pretreatments, under natural or unmanaged conditions, lignocellulosic residues are colonized by complex native microbial communities composed of bacteria, yeasts, and filamentous fungi [20]. These microorganisms are generally capable of metabolizing soluble sugars and low-molecular-weight compounds released during early stages of degradation; however, their capacity to depolymerize the lignocellulosic matrix remains limited due to the recalcitrant nature of lignin and lignin–carbohydrate complexes [8]. Consequently, natural degradation processes are typically slow and inefficient, highlighting the need for targeted inoculation with specialized lignocellulolytic fungi capable of producing oxidative enzyme systems.

Within the group of lignocellulolytic fungi, white-rot fungi are the most efficient degraders due to their capacity to produce oxidative enzymatic consortia [21]. Nevertheless, their targeted and systematic application as biological pretreatment agents for agave bagasse remains scarce. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the degradative capacity of Trametes versicolor, Trametes hirsuta, Irpex lacteus, and Schizophyllum commune on Agave tequilana Weber var. azul bagasse through the analysis of the reduction in total sugars, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin during a solid-state static treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lignocellulolytic Fungi

The fungi T. versicolor, T. hirsuta, and I. lacteus were collected from Bosque Cuauhtémoc (19°59′28″ N, 102°43′05″ W) in the municipality of Jiquilpan, Michoacán, Mexico. S. commune was collected from Barranca del Convento (20°03′31″ N, 102°42′57″ W) in the municipality of Sahuayo, Michoacán, Mexico. Basidiomata (fruiting bodies) were found growing on decaying oak wood (Quercus spp.).

Fungal identification was conducted based on macroscopic characters (basidioma morphology, coloration, consistency, and hymenophore arrangement) and microscopic characters (hyphal, basidial, and spore morphology), utilizing specialized taxonomic keys [22,23,24]. As reference material, select collected basidiomata were lyophilized and deposited in the mycological collection of CIIDIR-IPN, Michoacán Unit, as voucher specimens.

2.2. Fungal Cultivation and Propagation

Lignocellulolytic fungi were cultivated on a solid medium of Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA; 39 g L−1; Bioxon, Cuatitlán Izcalli, Mexico), adjusted to pH 5.5 ± 0.2 with 1 N HCl. The medium was sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C and 15 psi for 25 min (FE-120, Felisa, Guadalajara, Mexico) [25]. After sterilization, the medium was cooled to approximately 40–45 °C. Under aseptic conditions, chloramphenicol was added (25 mg L−1) to maintain selectivity for fungal growth [26]. The medium was then poured into sterile Petri dishes (≈20 mL per plate), allowed to solidify at room temperature, and stored inverted at 4 °C until further use [25].

Fungal isolation was performed using the collected fruiting bodies, which were disinfected by immersion in 5% (v/v) NaOCl for 5 min, followed by rinsing with sterile distilled water [27]. Internal fragments of sterile tissue were extracted from the basidiomata under aseptic conditions and placed individually in the center of PDA-chloramphenicol plates. The plates were sealed with Parafilm and incubated inverted at 25 ± 1 °C for 7–10 days (I1207, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) until active mycelial margins appeared. These margins were subcultured onto new PDA-chloramphenicol plates [28]. This subculturing process was repeated for two consecutive cycles until homogeneous, contaminant-free cultures were obtained.

2.3. Inoculum Preparation

Inoculum for T. versicolor, T. hirsuta, I. lacteus, and S. commune were prepared using the grain spawn technique [29]. Wheat grains (Triticum aestivum) were boiled for 15 min at a 1:1.2 (w/v) grain-to-water ratio until they reached a hydrated state without grain rupture. The cooked grain was drained on sterile absorbent paper and packed into 100 mL glass jars (25 g per jar). The jars were sterilized at 121 °C and 15 psi for 45 min (FE-120,Felisa, Guadalajara, Mexico). Once cooled, each jar was independently inoculated under aseptic conditions with two agar plugs (≈1 cm2) taken from the active margin of each pure culture.

A total of 18 jars were prepared per fungal species, each serving as a biological replicate with no inter-species mixing. Jars were incubated at 25 ± 1 °C for 12–14 days (SPX-150 Luzeren, Shangai, China), with manual shaking on the seventh day to ensure uniform growth. Full colonization was defined as 100% visual coverage of the grain by white, compact mycelium. The fresh grain spawn (used within ≤48 h post-colonization) served as the inoculum for the agave bagasse assays.

2.4. A. tequilana Bagasse

The agave bagasse used in this research was collected from the disposal area (19°57′55″ N, 102°48′00″ W) of Productos Selectos de Agave company, located in Jiquilpan, Michoacán. Following collection, it was spread in layers approximately 5 cm thick over an anti-aphid mesh suspended 1 m above the ground in a naturally ventilated area equipped with a retractable roof.

Drying occurred under average conditions of 25 ± 2/10 ± 1 °C (day/night) and a relative humidity (RH) of 60% ± 5%. The bagasse was manually turned every two days for 21 days until reaching a moisture content of 5%, as determined by the gravimetric method [30]. Once dry, the bagasse was processed using a blade mill (Landworks™ Chipper-GUO067, Salt LAke City, UT, USA) and sieved through a 1 cm mesh (ASTM). The material was subsequently stored in polypropylene bags at 22 ± 2 °C and 55–60% RH, monitored using a thermohygrometer (ThermoPro-TP49, Shenzhen, China) until experimental use. It is noteworthy that no washing or additional physical/chemical pretreatments were applied to the material.

2.5. Substrate Rehydration

Prior to fungal inoculation, the dry bagasse was rehydrated with distilled water to achieve a moisture content of 65% on a wet basis. To this end, the gravimetric method for agricultural products was employed [31]:

where Wt is the moisture content on a wet basis at time t, mt is the sample mass at time t, m is the initial dry mass of the material, and Wi is the initial moisture content on a wet basis. Based on Equation (1) and considering an initial moisture content of 5%, 1.7 L of water per kilogram of dry bagasse was required.

2.6. Biological Treatment of A. tequilana Bagasse (Solid-State Fermentation)

Solid-state (static) biological treatment was carried out using A. tequilana bagasse as substrate and lignocellulolytic fungi as inoculum. Rehydrated bagasse was distributed into autoclavable polypropylene bags (model ZWXT: 250 g per bag) equipped with 0.2 μm gas-exchange filters.

For sterile treatments (S), bags were autoclaved at 121 °C and 15 psi for 90 min (FE-120, Felisa, Guadalajara, Mexico), while non-sterile (NS) treatments remained unsterilized. Each bag was inoculated with 25 g of freshly colonized wheat grain spawn, corresponding to a substrate-to-inoculum ratio of 10:1 (w/w). Inoculation was performed under a laminar flow hood, and inoculum was evenly mixed by external manual agitation. Control treatments received sterile grain only.

Bags were incubated under static solid-state conditions at 24 ± 1 °C and 60–65% RH in complete darkness (SPX-150 Luzeren, Shanjai, China). The bags were arranged randomly to avoid temperature or humidity biases. Gas exchange was ensured by the 0.2 μm integrated filters. Samples were destructively collected at 20, 30, and 40 days of incubation, with three independent biological replicates per treatment and sampling time. Each experimental unit was assigned to a single sampling point to prevent cross-contamination.

2.7. Physicochemical Properties of A. tequilana Bagasse

To determine the initial physicochemical properties of the bagasse, the material was prepared by drying at 105 °C for 24 h (TE-FH70DM, Terlab, Guadalajara, Mexico). Subsequently, it was ground at 1500 rpm for 5 min (FPSTFP4255-000, Oster, Boca Raton, FL, USA) and sieved through a 0.5 mm mesh (ASTM) to ensure homogeneity. Analytical-grade reagents were used for all analyses, measurements followed the manufacturer’s recommended calibration protocols and, unless otherwise stated, results were expressed on a dry-weight basis (Table 1). Moisture content was experimentally adjusted prior to incubation and therefore not included as an analytical variable.

Table 1.

Physicochemical characterization of A. tequilana bagasse on a dry basis (values expressed as mean ± standard deviation, n = 3).

Electrical conductivity (EC) and pH were determined in 1:5 (w/v) distilled water extracts (HI-5521 Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) [32]. Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) was determined using the Kjeldahl method [33]. Ash content was obtained by muffle furnace combustion at 550 °C for 3 h (Thermolyne 1500 Furnace, Dubuque, IA, USA) [34]. From these data, Organic Matter (OM) was determined by weight difference [35], Total Organic Carbon (TOC) was calculated as OM/1.724 [36], and the C/N ratio was established based on the carbon and TKN results [32].

Macro and micronutrients (K, Ca, Mg, Na, Fe, Cu, Zn, and B) were determined via atomic absorption spectrophotometry (SensAA GBC, Dandenong, Australia) using the ash residue. Phosphorus (P) was determined colorimetrically (Perkin Elmer Lambda 2, Waltham, MA, USA) using the molybdenum blue method [37].

The methodology employed for the quantification of total sugars, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin was identical to that detailed in the following section. Based on the experimental design described below, bagasse degradation was determined by analyzing changes in the content of total sugars, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin at each sampling point. To this end, the corresponding bags were opened under aseptic conditions, and approximately 40 g of the bagasse + mycelium complex was extracted from the center of the block. Samples were dried at 105 °C for 24 h (Terlab TE-FH70DM, Mexico), ground at 1500 rpm for 2 min (Oster FPSTFP4255-000, USA), sieved through a 0.5 mm mesh (ASTM), and stored in a desiccator until use.

2.8. Total Sugars

Total sugars were determined using the phenol–sulfuric acid method [38]. Briefly, 2 g of the bagasse + mycelium fibers underwent deproteinization with 20 mL of CO2-free deionized water, 1 mL of ZnSO4, and 1 mL of 0.5 N NaOH. After 15 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 min (PrO-Analytical Centurion Scientific Ltd., Chichester, UK). For the determination, 1 mL of the supernatant was placed in a test tube, followed by the addition of 0.6 mL of 5% C6H6O and 3.6 mL of concentrated H2SO4. After cooling to room temperature (≈30 min), absorbance was measured at 490 nm against a blank (Perkin Elmer Lambda 2, USA). Concentration was determined using a standard curve prepared with glucose (C6H12O6) (10–100 μg mL−1), and the final content was expressed as follows:

where C = concentration obtained, V = total extract volume, and m = dry mass of the sample.

2.9. Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin

Cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin were determined using Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), and a modified Klason method [39,40,41].

For NDF, 0.5 g of the bagasse + mycelium complex was mixed with 50 mL of neutral detergent solution (C12H25SO4Na, EDTA, Na2B4O7⋅10H2O, and Na2HPO4) and 1 mL of α-amylase. The mixture was refluxed for 60 min in a fiber digester (FC-600, CRAFT® Monterrey, Mexico). Samples were filtered through Type C Gooch crucibles (50 mL), washed with hot distilled water (≈80 °C) and acetone, and dried at 105 °C for 24 h (Terlab TE-FH70DM, Mexico). The NDF percentage was calculated as:

where P0 = weight of the dry crucible, P1 = weight of the crucible + residue, and m = sample dry mass.

For ADF, 0.5 g of the fibers was mixed with 50 mL of acid detergent solution (concentrated H2SO4 and C19H42BrN) and 1 mL of anti-foaming agent (C10H18), then refluxed for 2 h (CRAFT® FC-600, Mexico). Filtration and drying followed the same procedure as NDF. Hemicellulose was determined by the difference between these fractions:

Lignin was determined via a modified Klason method, and 0.5 g of the sample underwent acid hydrolysis with 7 mL of 72% (w/w) H2SO4 at 20 ± 1 °C for 1 h under constant stirring. The solution was diluted to 3% (w/w) H2SO4 by adding 280 mL of deionized water and boiled for 2 h (CRAFT® FC-600, Mexico). After filtration and drying, the residue was incinerated at 550 °C for 3 h. Lignin content was calculated as:

where P0 = weight of the dry crucible, P1 = weight of the crucible + residue, m = sample dry mass, and C = residual ash weight. Finally, cellulose was calculated as:

2.10. Fiber Length of Fungi-Treated Agave Bagasse

As a complementary variable to the chemical analysis, the structural modification of the bagasse was evaluated by measuring fiber length from samples obtained at each experimental unit and incubation time defined in the experimental design.

Fiber length was determined using samples from each treatment at specific incubation intervals (20, 30, and 40 days). Approximately 10 g of each sample were dried at 70 °C for 48 h (TE-FH70DM; Terlab, Guadalajara, Mexico) and manually homogenized. A fraction of the dry material was then mounted on glass slides without staining [42]. The fibers were observed using a DV4 stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an AxioCam ICc 1 digital camera (Carl Zeiss, Germany), maintaining constant magnification and illumination settings.

For each technical replicate, five fields of view were randomly selected, and complete, clearly distinguishable fibers were measured until a total of 20 fibers per replicate was reached. This procedure was repeated three times per sample (n = 3 independent technical replicates), resulting in 60 individual fiber length measurements per treatment and incubation time. From each technical replicate (n = 20 fibers), two derived metrics were calculated using ZEN 3.4 analysis software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany): (i) minimum length and (ii) maximum length. Final values were reported as the mean ± standard deviation of the three minimum and three maximum values per treatment (n = 3).

2.11. Experimental Design

The experimental design was established to generate samples for the lignocellulosic and morphological analyses described in the previous sections.

A factorial design was employed, consisting of five treatments (four fungal species and one control), two conditions (sterile [S] and non-sterile [NS]), and three sampling intervals (20, 30, and 40 days). The experiment was conducted in triplicate, totaling 90 bags. Each bag represented an experimental unit assigned to a single sampling point to prevent cross-contamination. Treatments and inoculum composition are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental design and composition of sterile (S) and non-sterile (NS) treatments for agave bagasse degradation.

The positive control (CS) consisted of sterile agave bagasse supplemented with sterile wheat grain and incubated without fungal inoculation, serving as a reference for abiotic changes and baseline substrate stability under sterile conditions. The negative control (CNS) consisted of non-sterile agave bagasse supplemented with sterile wheat grain and incubated without fungal inoculation, representing the effect of the native microbiota on substrate degradation in the absence of targeted lignocellulolytic fungi.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

The data were initially assessed to verify the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance using the Shapiro–Wilk test (p ≤ 0.05) and Levene’s test, respectively. For variables associated with the structural fraction of the agave bagasse (total sugars, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin), a Linear Mixed Model (LMM) was employed to account for the experimental structure and the dependency between measurements. The model included inoculum type, sterility condition, incubation time, and their interactions as fixed effects, while the experimental unit was incorporated as a random effect.

The models were fitted using Maximum Likelihood (ML), and the significance of the fixed effects was evaluated via Type III ANOVA (α = 0.05). Multiple comparisons were performed using Estimated Marginal Means (EMM) with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test. Model assumptions were further verified through residual analysis.

Data for minimum and maximum fiber length were analyzed independently for each incubation interval using a one-way ANOVA, with treatment as a fixed factor. When necessary, data were log-transformed (ln) to satisfy normality and homoscedasticity assumptions. Differences between treatments were determined using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test. All statistical analyses were conducted in R software, version 4.5.2. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 26 December 2025) [43], utilizing the lme4 (version 1.1-38) package for linear mixed-effects modeling [44].

3. Results

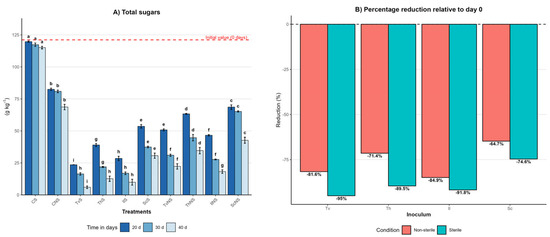

3.1. Total Sugars in A. tequilana Bagasse following Fungal Treatment

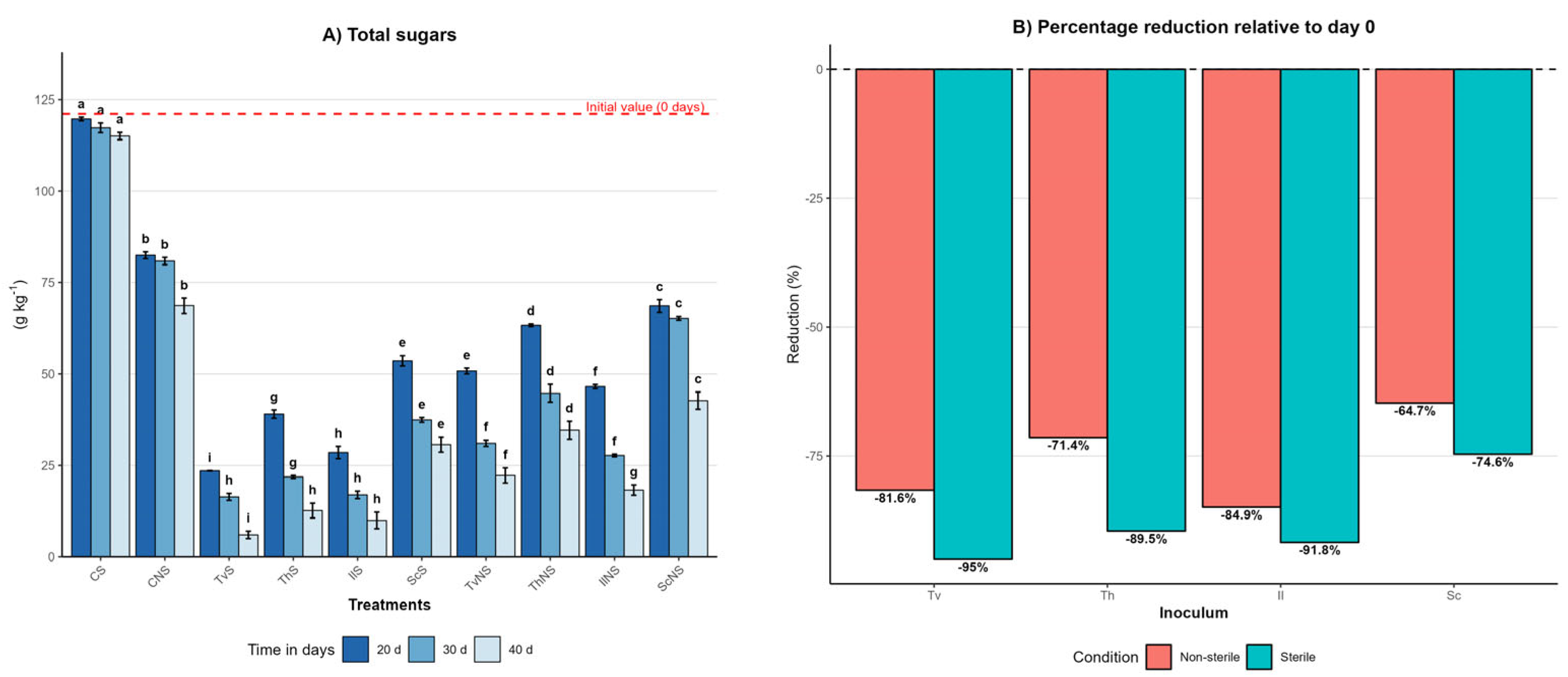

The total sugars content in A. tequilana bagasse decreased progressively across all treatments during the incubation period, with sterility being the most influential factor in determining degradation patterns (Figure 1A). In general, sterile treatments (S) exhibited significantly greater reductions than their non-sterile (NS) counterparts (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effect of inoculum type, sterility condition, and incubation time on the total sugars dynamics in A. tequilana bagasse. (A) Total sugars content (g kg−1, mean ± SD (n = 3)) measured at 20, 30, and 40 days of incubation for each treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments within the same incubation time, based on Tukey’s comparisons (p = 0.05). (B) Percentage reduction in total sugars content at day 40 relative to the initial value (day 0) under sterile and non-sterile conditions.

At day zero, the bagasse had an initial sugars content of 121 ± 1 g kg−1. The sterile control (CS) remained stable throughout the 40-day incubation, decreasing slightly from 121 ± 1 to 115 ± 1 g kg−1, whereas the non-sterile control (CNS) was reduced to 68 ± 2 g kg−1. The 39% difference between controls highlights the degradative capacity of the native microbiota of the bagasse and provides a baseline to interpret the effect of fungal inoculation under scenarios of microbial competition.

Under sterile conditions, all fungi induced pronounced reductions by the end of the incubation (day 40). TvS reached 6 ± 1 g kg−1, IlS 9 ± 2 g kg−1, ThS 12 ± 2 g kg−1, and ScS 30 ± 2 g kg−1. These treatments were categorized into the statistical groups with the lowest total sugars values (p ≤ 0.05), reflecting high degradative efficiency when fungal activity is not constrained by competition. Conversely, under non-sterile conditions, the contents at day 40 were consistently higher: TvNS reached 22 ± 2 g kg−1, IlNS 28 ± 1 g kg−1, ThNS 34 ± 2 g kg−1, and ScNS 42 ± 2 g kg−1. These results demonstrate a significant reduction in fungal efficiency in the presence of the native bagasse microbiota.

The efficiency of sugars degradation is summarized in Figure 1B, which illustrates the percentage reduction at day 40 relative to the initial value. This representation confirms that sterile systems consistently outperformed non-sterile ones, with reductions ranging from 75% to 95% under sterile conditions and from 65% to 85% under non-sterile conditions, depending on the fungal species. Despite the differences in absolute values and sterility conditions, the relative hierarchy of fungal performance remained constant across all treatments, following the general order: T. versicolor > I. lacteus > T. hirsuta > S. commune.

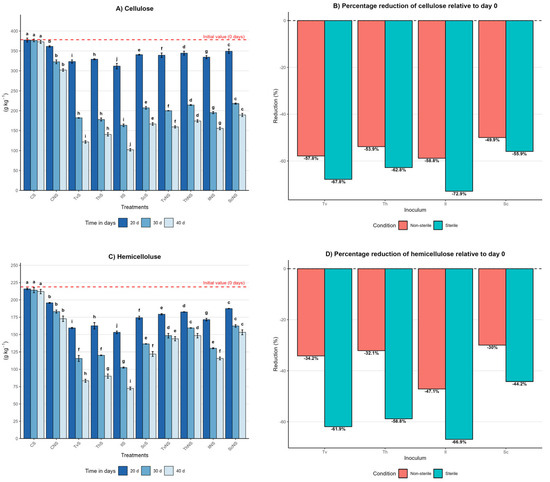

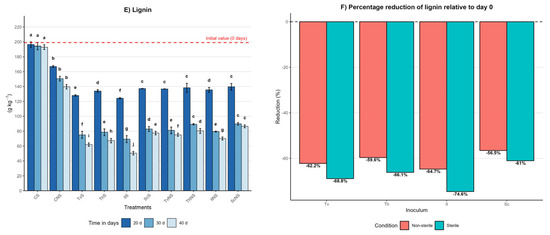

3.2. Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin in A. tequilana Bagasse Following Fungal Treatment

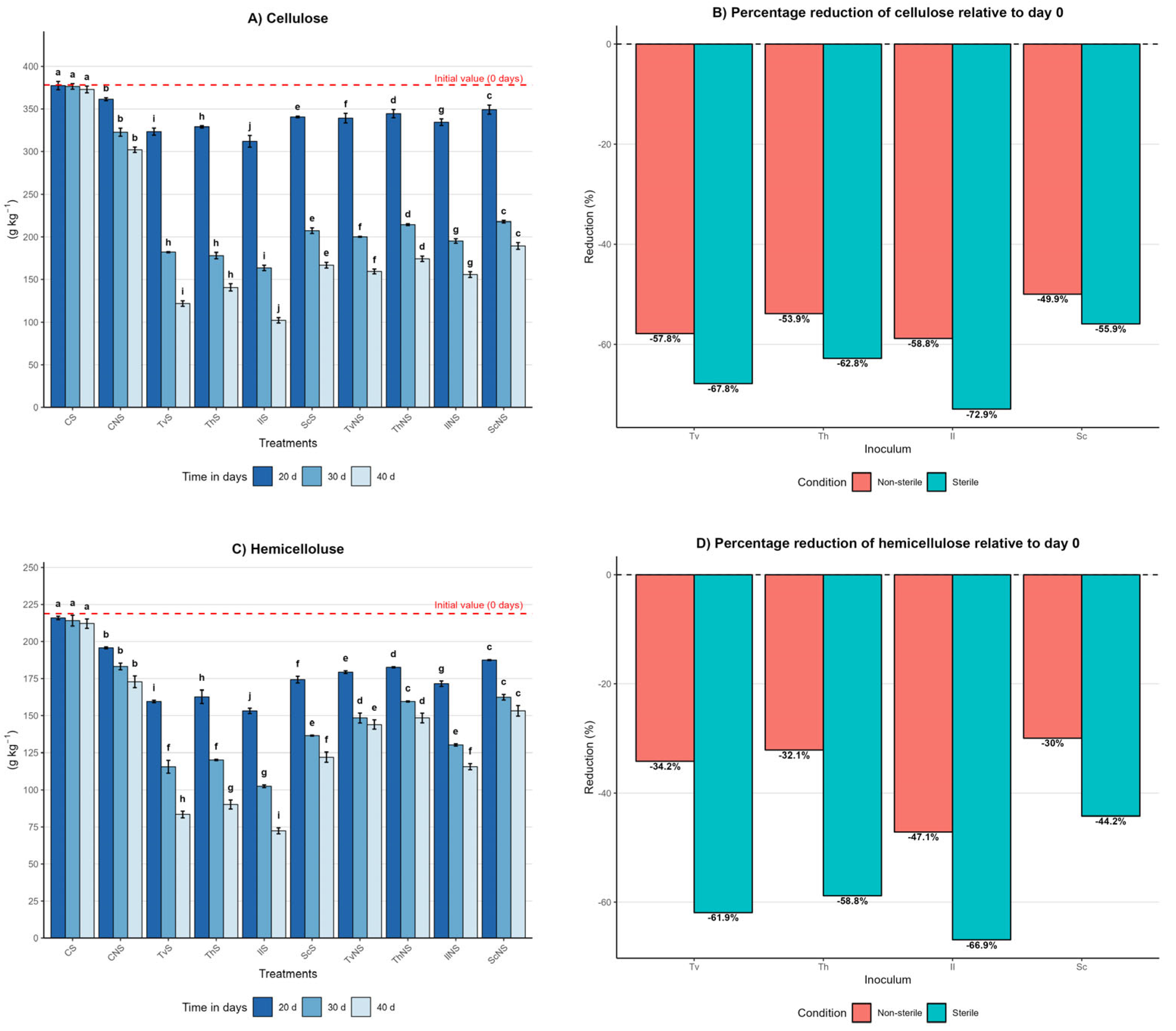

The content of the three structural components showed a progressive reduction across all treatments (Figure 2A,C,E). At day zero, the bagasse contained 378 ± 7 g kg−1 of cellulose, 218 ± 4 g kg−1 of hemicellulose, and 199 ± 1 g kg−1 of lignin. These values were established as the baseline to evaluate changes in both controls and treatments.

Figure 2.

Effect of inoculum type, sterility condition, and incubation time on the dynamics of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in A. tequilana bagasse. (A) Cellulose content (g kg−1, mean ± SD (n = 3)) measured at 20, 30, and 40 days of incubation for each treatment. (B) Percentage reduction in cellulose at day 40 relative to day 0 under sterile (S) and non-sterile (NS) conditions. (C) Hemicellulose content (g kg−1, mean ± SD (n = 3)) measured at 20, 30, and 40 days of incubation for each treatment. (D) Percentage reduction in hemicellulose at day 40 relative to day 0 under S and NS conditions. (E) Lignin content (g kg−1, mean ± SD (n = 3)) measured at 20, 30, and 40 days of incubation for each treatment. (F) Percentage reduction in lignin at day 40 relative to day 0 under S and NS conditions. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments within the same incubation time, based on Tukey’s comparisons (α = 0.05).

In the sterile control (CS), contents remained constant, with day 40 values of 372 ± 4 g kg−1 for cellulose, 212 ± 3 g kg−1 for hemicellulose, and 193 ± 3 g kg−1 for lignin, representing negligible reductions of 1%, 3%, and 3%, respectively. In contrast, the non-sterile control (CNS) showed significant reductions: 20% in cellulose, 21% in hemicellulose, and 30% in lignin, with final values of 302 ± 3 g kg−1, 172 ± 4 g kg−1, and 139 ± 3 g kg−1, respectively. Differences between controls were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05), indicating that the native microbiota of the bagasse contributes to a partial degradation of the lignocellulosic matrix.

Under sterile conditions at day 40, IlS exhibited the highest degradation, with final values of 102 ± 3 g kg−1 for cellulose, 72 ± 2 g kg−1 for hemicellulose, and 50 ± 2 g kg−1 for lignin. TvS reached 121 ± 3 g kg−1, 83 ± 2 g kg−1, and 62 ± 2 g kg−1; ThS reached 140 ± 4 g kg−1, 90 ± 3 g kg−1, and 67 ± 3 g kg−1; and ScS reached 166 ± 3 g kg−1, 122 ± 3 g kg−1, and 77 ± 2 g kg−1. In non-sterile conditions, the same effectiveness hierarchy was maintained, albeit with lower reductions. By day 40, IlNS final values were 155 ± 3 g kg−1, 115 ± 2 g kg−1, and 70 ± 2 g kg−1; TvNS reached 159 ± 3 g kg−1, 144 ± 3 g kg−1, and 75 ± 2 g kg−1; ThNS reached 174 ± 3 g kg−1, 148 ± 3 g kg−1, and 80 ± 3 g kg−1; and ScNS reached 189 ± 4 g kg−1, 153 ± 3 g kg−1, and 86 ± 2 g kg−1.

A pivotal finding was that, in most fungal treatments, the degradation order of the structural components was lignin > cellulose > hemicellulose. This behavior suggests that the evaluated species prioritize lignin removal as a strategy to disrupt the lignocellulosic matrix, thereby facilitating enzymatic access to the structural polysaccharides. This pattern challenges the notion of lignin as the most recalcitrant component and highlights the high efficiency of the ligninolytic systems of the fungi studied.

The efficiency of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin degradation is summarized in Figure 2B,D,F, expressing the percentage reduction at day 40 relative to the initial value. This representation confirms that sterile systems consistently outperform non-sterile ones. Reductions ranged from 55% to 73% for cellulose, 44% to 67% for hemicellulose, and 61% to 75% for lignin under sterile conditions. Under non-sterile conditions, reductions were between 50% and 59% for cellulose, 30% and 47% for hemicellulose, and 57% and 65% for lignin, depending on the fungal species. The lower degradation in non-sterile conditions suggests that competition with the native microbiota limits lignocellulolytic enzymatic activity. Nevertheless, the consistent degradation order between components and species indicates that the fungal metabolic strategy is preserved even within a more complex microbial context.

Temporal analysis showed that the highest degradation occurred between days 20 and 30, followed by a more moderate reduction toward day 40. The order of effectiveness in degrading the lignocellulosic matrix was I. lacteus ≥ T. versicolor > T. hirsuta > S. commune.

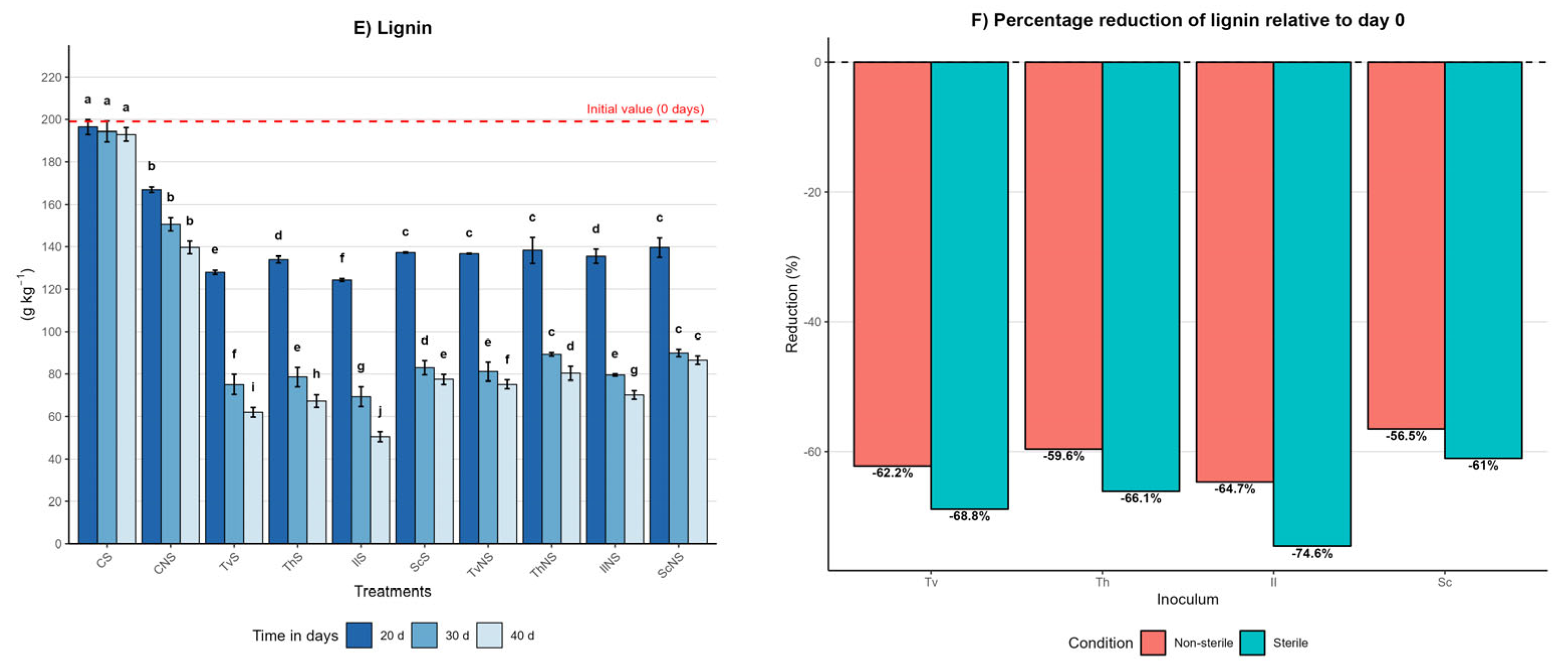

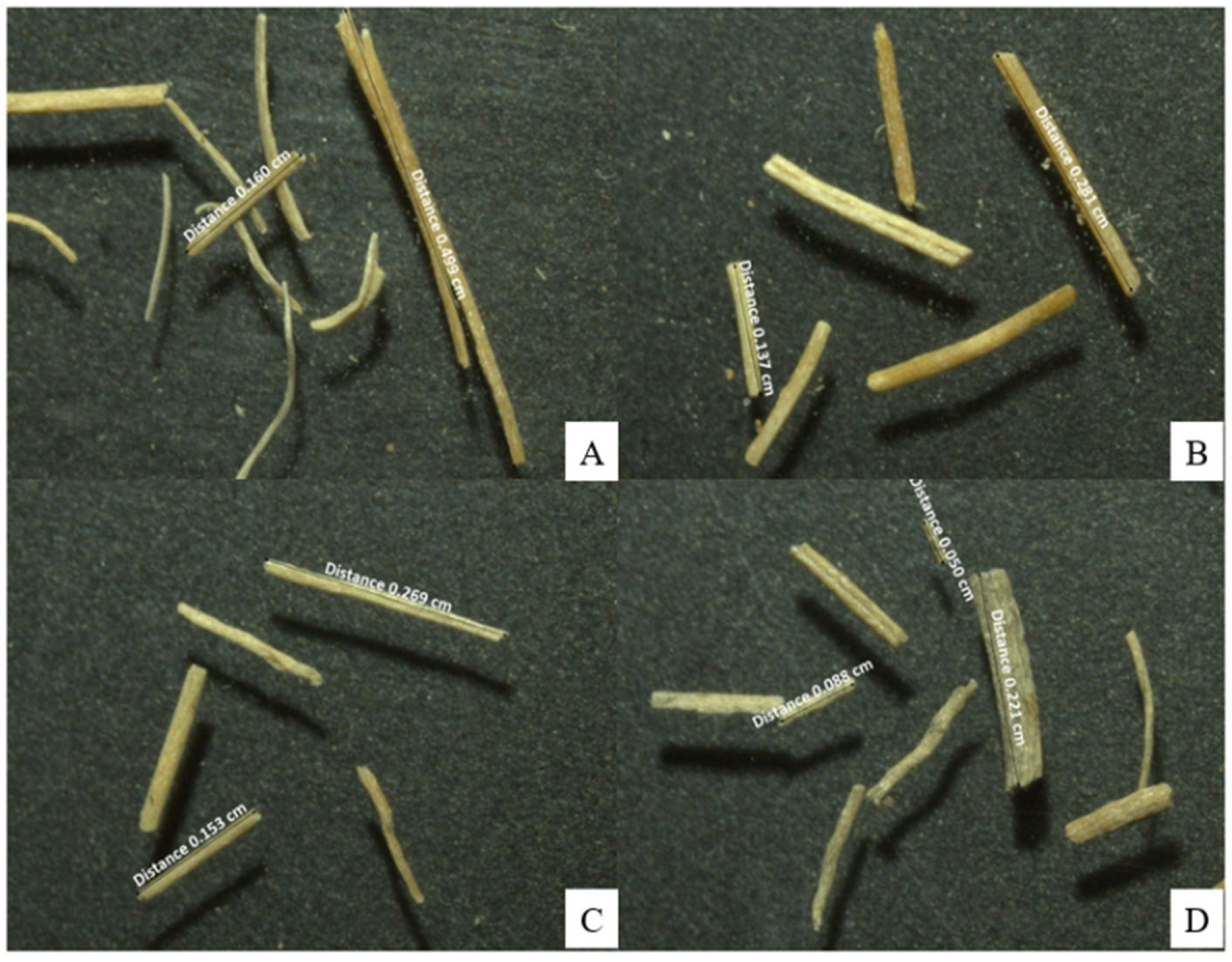

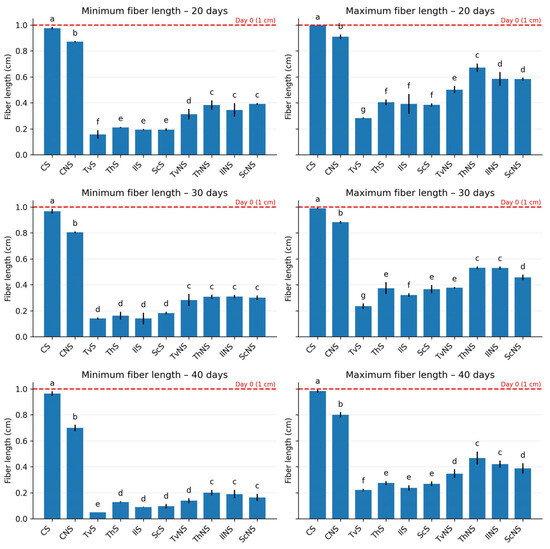

3.3. Fiber Length of Fungi-Treated A. tequilana Bagasse

At the beginning of the experiment, all experimental units contained fibers measuring ≈1.0 cm (Figure 3). In the sterile control (CS), fiber lengths remained virtually constant throughout the 40 days, with minimum values shifting from 0.976 to 0.965 cm and maximum values from 0.998 to 0.984 cm, confirming the stability of the bagasse in the absence of biological activity. In contrast, a progressive shortening was observed in the non-sterile control (CNS), reaching a minimum of 0.699 cm and a maximum of 0.800 cm by day 40.

Figure 3.

Minimum and maximum fiber lengths of agave bagasse after 20, 30, and 40 days of incubation. Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments within each incubation time (Tukey’s HSD, α = 0.05).

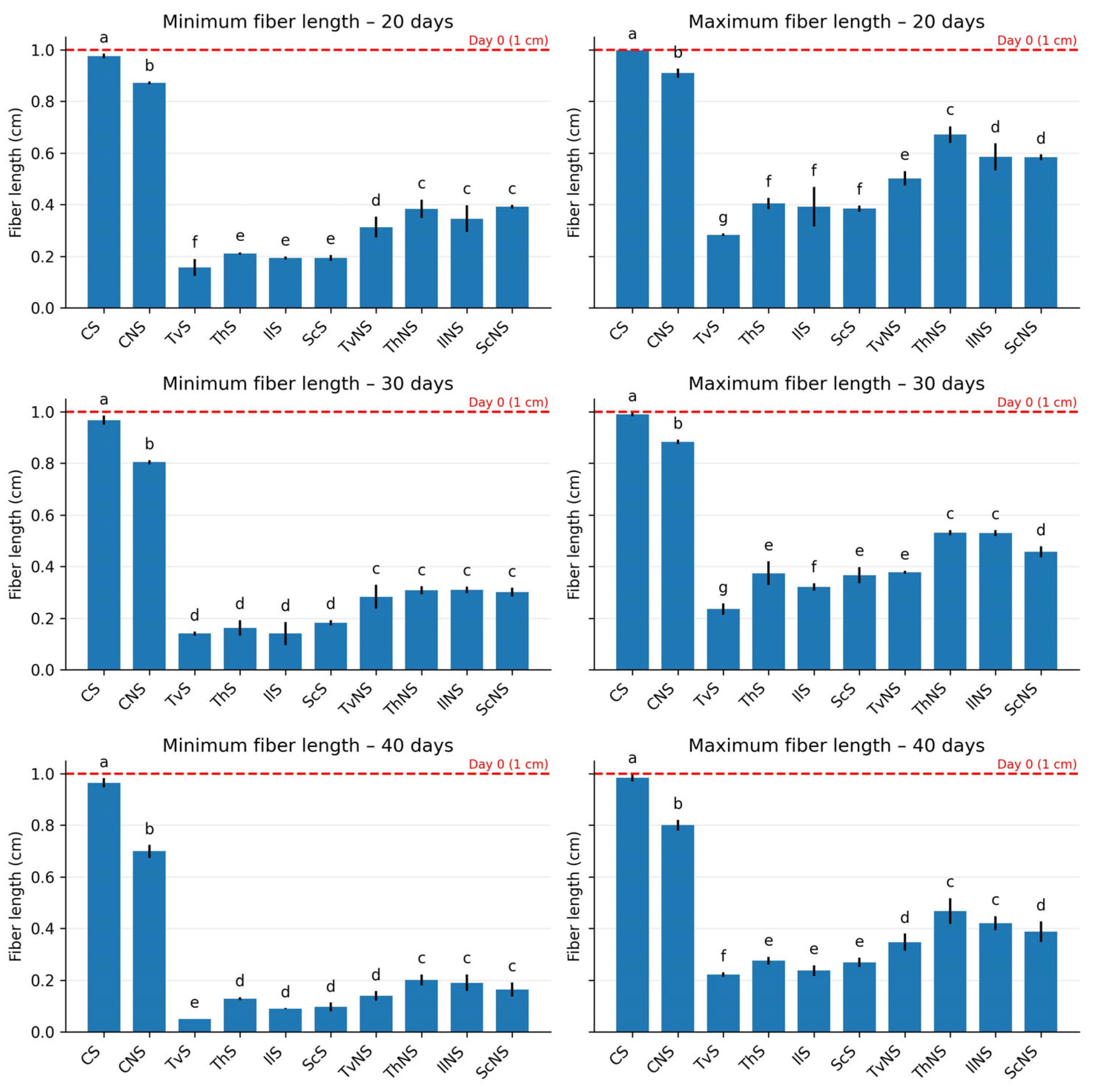

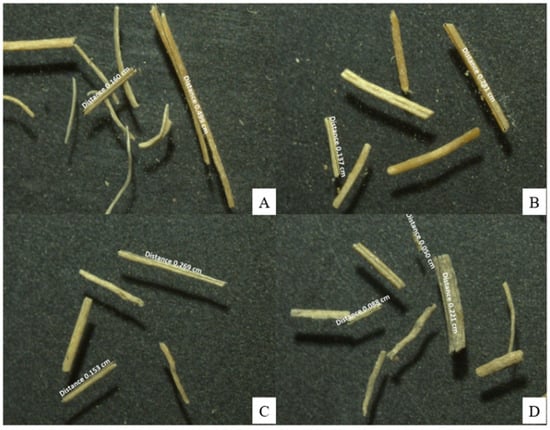

In the fungal treatments, statistically significant reductions (p ≤ 0.05) were recorded relative to the initial value and the controls. TvS exhibited the shortest fibers, with a minimum of 0.050 cm and a maximum of 0.221 cm (Figure 4); followed by IlS with a minimum of 0.090 cm and a maximum of 0.236 cm; ScS with a minimum of 0.096 cm and a maximum of 0.268 cm; and ThS with a minimum of 0.128 cm and a maximum of 0.274 cm.

Figure 4.

Representative stereomicroscopic photographs of fiber length in the T. versicolor treatment and its corresponding control: (A) CNS (40 days); (B) TvS (20 days); (C) TvS (30 days); (D) TvS (40 days).

In contrast, a progressive shortening was observed in the CNS, reaching a minimum of 0.699 cm and a maximum of 0.800 cm by day 40. In the fungal treatments, statistically significant reductions (p ≤ 0.05) were recorded relative to the initial value and the controls. TvS exhibited the shortest fibers, with a minimum of 0.050 cm and a maximum of 0.221 cm; followed by IlS with a minimum of 0.090 cm and a maximum of 0.236 cm; ScS with a minimum of 0.096 cm and a maximum of 0.268 cm; and ThS with a minimum of 0.128 cm and a maximum of 0.274 cm.

Under non-sterile conditions, the fiber-maintained lengths between 45% and 60% greater than those observed in sterile treatments. The ranges were as follows: TvNS, minimum 0.139 cm and maximum 0.346 cm; IlNS, minimum 0.189 cm and maximum 0.420 cm; ThNS, minimum 0.200 cm and maximum 0.467 cm; and ScNS, minimum 0.163 cm and maximum 0.388 cm. Taken together, these results show that fungal treatments not only reduced average length but also promoted fragmentation, generating a wide distribution of sizes and evidencing the destructuring of the fibrous matrix.

4. Discussion

This research evaluated the degradative capacity of T. versicolor, T. hirsuta, I. lacteus, and S. commune on A. tequilana bagasse under sterile and non-sterile conditions, aiming to identify the most efficient species for the depolymerization of the lignocellulosic matrix. Importantly, the inclusion of non-sterile treatments was intended to simulate open and operationally realistic conditions, as substrate sterilization is not economically or technically feasible in large-scale solid-state fermentation systems.

However, the results indicate that the evaluated species exhibit differentiated degradative strategies, associated with specific enzymatic profiles and contrasting modes of attack on the lignocellulosic matrix. T. versicolor is associated with a more balanced and structurally disruptive degradation pattern, whereas I. lacteus presents a predominantly oxidative strategy oriented toward selective lignin removal. This functional differentiation constitutes the central finding of this study and suggests the coexistence of complementary degradative profiles rather than the existence of a single superior species.

Furthermore, sterility was identified as a quantifiable factor modulating degradative efficiency. Rather than representing a practical operational condition, sterile treatments served as a mechanistic reference to isolate fungal activity from microbial interference, allowing the intrinsic lignocellulolytic potential of each species to be assessed. This suggests that microbial competition affects ligninolytic processes—which are highly dependent on the chemical microenvironment and the availability of cofactors—more markedly than polysaccharide hydrolysis.

It should be noted that the sterilization process applied in this study may have contributed, to a limited extent, to physical modifications of the agave bagasse. Thermal exposure under autoclave conditions can promote fiber swelling and partial relaxation of lignin–carbohydrate complexes, potentially increasing surface accessibility to fungal enzymes. However, this treatment does not constitute a severe thermochemical pretreatment, as no acidic or alkaline agents were applied and no extensive solubilization of lignin or structural carbohydrates is expected under these conditions. Therefore, while a minor contribution of thermal effects cannot be excluded, the higher degradation observed under sterile conditions is primarily attributed to the absence of microbial competition, which allows the inoculated fungi to establish more effectively and express their lignocellulolytic enzymatic systems without interference from the native microbiota.

4.1. Degradation Dynamics of A. tequilana Bagasse by Lignocellulolytic Fungi

The temporal degradation pattern for total sugars, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin exhibited a rapid phase (20–30 days) followed by a deceleration toward day 40. This behavior is characteristic of a biphasic process: an initial phase dominated by the oxidative attack of lignin, driven by enzymes such as laccases (Lac), manganese peroxidase (MnP), and versatile peroxidases (VP), which increase the accessibility of structural polysaccharides, followed by a second phase of cellulose and hemicellulose hydrolysis mediated by cellulases and xylanases [45,46]. Notably, this biphasic behavior was preserved under non-sterile conditions, indicating that fungal-driven lignocellulosic deconstruction can proceed despite the presence of native microbiota.

4.2. Total Sugars Degradation

The comparison between controls (sterile and non-sterile) highlights the modulating role of the native microbiota in total sugars degradation. This suggests that the native microbiota preferentially metabolizes soluble sugars and exposed oligomers but lacks efficient access to the structural matrix. This phenomenon has also been reported for sugarcane bagasse, where the native microbiota reduced total sugars by 15–20% over 30–40 day periods [47].

Compared to previous studies, the performance of T. versicolor and I. lacteus under sterile conditions falls within the upper range of efficiency reported for lignocellulolytic fungi degrading agave bagasse, surpassing the values reported for B. adusta [8]. This higher efficiency can be attributed to an enhanced oxidative capacity and the synergistic action of ligninolytic oxidoreductases, which facilitate the opening of the lignocellulosic matrix and the subsequent release of structural carbohydrates [48,49,50]. However, from an applied perspective, the sustained activity observed under non-sterile conditions is of greater relevance, as it reflects the capacity of these fungi to compete for substrates and maintain metabolic activity in open systems.

Under non-sterile conditions, fungal efficiency decreased by 15% to 30%, depending on the species. Despite this reduction, all fungi retained substantial degradative capacity, demonstrating resilience to microbial competition. This reduction is attributable to competition with the native microbiota for readily assimilable soluble substrates and the partial inhibition of laccases and peroxidases by phenolic compounds and saponins. These compounds limit the expression and activity of oxidative systems, primarily affecting the initial stages of the degradative process [8].

4.3. Degradation of the Lignocellulosic Matrix

The results demonstrate a hierarchical order in the degradative efficiency of the evaluated fungal species, following the sequence: I. lacteus ≥ T. versicolor > T. hirsuta > S. commune. This hierarchy was maintained under non-sterile conditions, reinforcing the robustness of species-specific enzymatic strategies in realistic fermentation environments.

The superiority of I. lacteus in the degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin is consistent with its enzymatic profile reported in the literature, which includes laccase (Lac), manganese peroxidase (MnP), versatile peroxidase (VP), and dye-decolorizing peroxidases (DyPs), in addition to numerous glycoside hydrolases (GHs) that promote the synergistic degradation of the lignocellulosic matrix [51,52,53]. The observed patterns—high selective delignification while maintaining accessible cellulosic fractions—reflect a sequential oxidative-hydrolytic strategy: lignin is first oxidized via oxidative enzymes, which increases the accessibility of cellulose and hemicellulose for GHs, generating a progressive and highly efficient depolymerization process [51,52].

T. versicolor, while slightly less efficient in chemical degradation, showed the greatest capacity for physical disintegration. This degradation behavior—rapid loss of total sugars, simultaneous reduction in all structural components, and intense fiber fragmentation—is consistent with the balanced mechanism reported for T. versicolor. In this mechanism, oxidative enzymes (Lac, MnP, and VP) generate phenoxyl radicals and reactive intermediates capable of breaking the β-O-4 linkages of lignin and releasing the cellulosic and hemicellulosic fractions, thereby favoring rapid substrate disintegration [16,53,54]. This apparent paradox—lower chemical efficiency but greater physical disintegration—suggests that the balanced attack of T. versicolor is more homogeneous and structurally disruptive, whereas I. lacteus exerts a more localized attack. Future studies measuring specific enzymatic activity and the spatial distribution of degradation could confirm this hypothesis.

T. hirsuta showed intermediate efficiency, attributable to its primary reliance on MnP and a lower diversity of auxiliary enzymes [54]. S. commune exhibited the lowest degradative efficiency, which is coherent with its predominantly hydrolytic profile and limited action on the aromatic compounds of lignin [55]. Taken together, the chemical and physical data reveal that each fungus induces distinct degradative processes determined by the combination and regulation of their oxidative and hydrolytic systems.

4.4. Limitations and Competition Under Non-Sterile Conditions

The decrease in fungal efficiency observed under non-sterile conditions is the result of the synergistic interaction of three mechanisms—biological and physicochemical—that limit lignocellulolytic activity. First, competition with the native microbiota for soluble sugars released during initial hydrolysis reduces the carbon flux available for mycelial growth and enzymatic expression. This effect is evident in the CNS, where the reduction in total sugars suggests a preferential consumption of readily accessible fractions without substantial degradation of the structural matrix. Additionally, the native microbiota can produce secondary metabolites, modify pH, and alter redox gradients, negatively affecting the activity of oxidative enzymes [56].

Second, phenolic compounds in A. tequilana bagasse (e.g., ferulic and p-coumaric acids), as well as steroidal saponins, can inhibit the activity of Lac and VP. This effect is selective and depends on the enzymatic profile of each species: fungi with a higher diversity of oxidative isoenzymes show greater tolerance, while species more dependent on specific systems, such as MnP, exhibit a greater loss of efficiency [8,57,58]. This explains why T. versicolor maintained ~80% efficiency under non-sterile conditions, in contrast to T. hirsuta and S. commune, which showed reductions slightly exceeding 35%. Third, the combined metabolic activity alters the chemical microenvironment of the substrate (pH, redox potential, metal cofactors (Mn2+, Fe2+)), shifting enzymatic systems toward suboptimal catalytic pathways and affecting vital catalytic cycles [52].

The industrial thermal pretreatment of A. tequilana bagasse (95–105 °C; 8–12 h) partially mitigates these three mechanisms by increasing enzymatic accessibility through the partial hydrolysis of hemicellulose, the loosening of lignin-carbohydrate complexes (LCCs), and the exposure of amorphous cellulose regions. This allows the inoculated fungi to establish rapid colonization and express lignocellulolytic enzymes before the native microbiota reaches inhibitory densities. However, thermal pretreatment does not eliminate interference mechanisms but merely reduces their temporal impact. This explains the high degradation efficiencies observed under non-sterile conditions, which are superior to those reported for other non-pretreated lignocellulosic substrates [59].

In this integrated context, the relative superiority of T. versicolor and I. lacteus under non-sterile conditions can be explained by their complementary enzymatic strategies. The tolerance of T. versicolor to phenolic compounds is consistent with the reported breadth and efficiency of its laccase system, which is capable of oxidizing and detoxifying a wide variety of aromatic molecules [53]. Meanwhile, the resilience of I. lacteus is consistent with enzymatic profiles that include DyPs and lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs), which are reported to be less sensitive to phenolic inhibitors [52]. In contrast, T. hirsuta (dependent on MnP) and S. commune (possessing a more limited ligninolytic system) appear to be more vulnerable to phenolic inhibition and microbial competition, accounting for their lower efficiency.

4.5. Structural Modifications: Fiber Length

The reduction in fiber length serves as a direct physical indicator of the enzymatic attack pattern on the lignocellulosic matrix. Despite showing a slightly lower lignin reduction than IlS, TvS was the fungus that produced the shortest fibers. The discrepancy observed between chemical delignification and physical fragmentation indicates that structural disintegration does not follow a linear relationship; rather, it depends on the spatial and temporal patterns of the oxidative attack. This is consistent with a balanced attack mechanism that generates distributed disruptions with multiple fracture points [15,60].

IlS exhibited the second-highest efficiency but with a differential pattern: despite achieving the greatest lignin reduction, it produced significantly longer fibers than TvS. This suggests that I. lacteus exerts a more localized or chemo-selective attack, where deep delignification does not translate proportionally into physical fragmentation. This is in agreement with previous studies demonstrating its high production of oxidative ligninolytic enzymes and H2O2-dependent LPMOs, which favor access to crystalline cellulose regions and enhance synergy with endoglucanases [61,62]. The progressive shortening recorded coincides with mechanisms described by Zhu et al. [63], where Fenton-type reactions and early LPMO action expand nano porosity, facilitating the rupture of microfibers.

Under non-sterile conditions, fibers-maintained lengths 45–60% greater than those in sterile treatments, indicating that microbial competition limits not only chemical degradation but also the physical disintegration of the material. This finding further supports the interpretation that open conditions impose realistic constraints on fungal performance, which must be considered when designing scalable biological pretreatment strategies. The reduction in physical fragmentation is quantitatively greater than the reduction in chemical degradation, suggesting that microbial interference mechanisms disproportionately affect the processes of macroscopic structural rupture. This behavior aligns with findings by Niu et al. [64], who observed that sterility enhances fungal colonization and selective lignin degradation.

4.6. Biotechnological Implications

The results of this study demonstrate a marked functional specialization among the evaluated fungal species, allowing for the strategic utilization of A. tequilana bagasse based on specific biotechnological objectives. Crucially, the ability of T. versicolor and I. lacteus to maintain high degradative efficiency under non-sterile conditions underscores their suitability for large-scale solid-state fermentation, where strict sterilization is impractical. The integration of chemical and physical analyses indicates that each fungus induces distinct degradative processes, reflected in both the depth of the lignocellulosic matrix modification and the degree of structural disintegration.

In this context, T. versicolor is associated with a rapid and global transformation of the substrate, characterized by intense physical fragmentation derived from a synchronized attack on the various structural components. This behavior is particularly relevant for applications requiring a significant reduction in particle size and increased exposure of fermentable carbohydrates, such as saccharification and biorefinery processes. In contrast, I. lacteus exhibits a more selective strategy, primarily oriented toward the efficient removal of lignin with a more controlled degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose, thereby preserving the macroscopic integrity of the fiber to a greater extent. This functional differentiation constitutes a key criterion for selecting the appropriate fungus based on the final intended use of the treated material.

The high levels of fragmentation achieved by T. versicolor and I. lacteus—comparable to those reported for other lignocellulosic residues such as rice straw [65]—support the potential of biological pretreatment as an effective strategy to enhance enzymatic accessibility and the release of fermentable sugars compared to untreated materials. Additionally, the ability of both species to maintain high efficiencies under non-sterile conditions suggests that low-energy strategies, such as pasteurization and the use of dominant inoculate, can be implemented as substitutes for strict sterilization without substantially compromising degradative performance. This positions biological pretreatment as a technically feasible and energetically sustainable alternative for the valorization of agave bagasse under industrially relevant conditions.

Although these compositional and structural modifications are widely recognized as key determinants of biomass digestibility, saccharification efficiency was not directly evaluated in the present study and should be addressed in future research to quantitatively confirm the impact of fungal pretreatment on fermentable sugar release.

From a circular economy perspective, these results highlight the potential of biological pretreatment to accelerate the utilization and valorization of A. tequilana bagasse within biorefinery frameworks. However, the absence of direct enzymatic measurements, the specificity of agave bagasse (which undergoes an inherent industrial thermal pretreatment), and effects associated with mass transfer and bed heterogeneity—known to substantially modify the behavior of small-scale systems [66]—limit the immediate extrapolation of these results. Consequently, it is necessary to validate these strategies on other lignocellulosic residues and in pilot-scale reactors to evaluate the physicochemical gradients typical of larger scales, thereby consolidating the potential of biological pretreatment as a sustainable industrial alternative.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained confirm that T. versicolor, T. hirsuta, I. lacteus, and S. commune exhibit lignocellulolytic activity on A. tequilana bagasse, albeit with differentiated performances. T. versicolor demonstrated the highest capacity for overall degradation, evidenced by pronounced reductions in total sugars and fiber length. In contrast, I. lacteus stood out for its high efficiency in lignin removal, coupled with a more controlled degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose. Meanwhile, T. hirsuta and S. commune showed intermediate degradative performance. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the analysis of structural carbohydrate and lignin reduction allows for the discrimination of the specific degradative potential of each fungus on A. tequilana bagasse.

Future research should focus on enzymatic saccharification and biomass digestibility assays to confirm the downstream bioconversion potential of agave bagasse following fungal biological pretreatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Á.A.-L. and M.A.L.-H.; methodology, L.Á.A.-L.; validation, D.Á.-B., M.A.L.-H. and E.C.-B.; formal analysis, L.Á.A.-L.; investigation, L.Á.A.-L. and M.A.L.-H.; resources, D.Á.-B.; data curation, M.d.l.L.X.N.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Á.A.-L. and M.A.L.-H.; writing—review and editing, D.Á.-B. and M.A.L.-H.; supervision, M.A.L.-H.; project administration, D.Á.-B.; funding acquisition, D.Á.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SIP-IPN, grant number 20250173 and the first author receives a doctoral scholarship from SECIHTI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Gemini (Google) to polish the English text for clarity. Additionally, the graphical abstract was generated using the same tool. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Herrera-Pérez, L.; Valtierra-Pacheco, E.; Ocampo-Fletes, I.; Tornero-Campante, M.A.; Hernández-Plascencia, J.A.; Rodríguez-Macías, R. Evaluation of the Sustainability of Two Types of Agave tequilana Weber Var. Blue Agroecosystems in Tequila, Jalisco. Agrociencia 2023, 57, 1773–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Maya, A.; Weber, B. Biogás y Bioetanol a Partir de Bagazo de Agave Sometido a Explosión de Vapor e Hidrólisis Enzimática. Ing. Investig. Tecnol. 2022, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRT Información Estadística Guadalajara, Jalisco: Consejo Regulador Del Tequila (CRT). Available online: https://www.crt.org.mx/EstadisticasCRTweb/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Crespo-González, M.R.; Rodríguez-Macías, R.; González-Eguiarte, D.R.; Canale-Guerrero, A. Características Físico-Químicas y Microbiológicas Del Compostaje de Bagazo de Agave Tequilero a Escala Industrial. Rev. Energ. Quím. Fís 2019, 6, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, M.N.; Shinde, S.; Nimbalkar, N.J.; Jadhav, P.S.; Zambare, D.N.; Wategaonkar, S.B. Air Pollutants from Sugar Industry Chimneys: Evaluating Environmental Hazards and Global Mitigation Strategies. ChemSci Adv. 2024, 1, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Vázquez, D.; Carrillo-Nieves, D.; Orozco-Nunnelly, D.A.; Senés-Guerrero, C.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. An Integrated Approach for the Assessment of Environmental Sustainability in Agro-Industrial Waste Management Practices: The Case of the Tequila Industry. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 682093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Hinestroza, H.; Hernández-Diaz, J.A.; Esquivel-Alfaro, M.; Toriz, G.; Rojas, O.J.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B.C. Isolation and Characterization of Nanofibrillar Cellulose from Agave tequilana Weber Bagasse. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1342547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Salazar, R.G.; Marino-Marmolejo, E.N.; Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Davila-Vazquez, G.; Contreras-Ramos, S.M. Use of Agave Bagasse for Production of an Organic Fertilizer by Pretreatment with Bjerkandera adusta and Vermicomposting with Eisenia fetida. Environ. Technol. 2016, 37, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Ley General Para La Prevención y Gestión Integral de Los Residuos; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- NOM-052-SEMARNAT-2005; Que establece las características, el procedimiento de identificación, clasificación y los listados de los residuos peligrosos. DOF: Ciudad de México, México, 2005.

- NOM-004-SEMARNAT-2002; Protección ambiental.—Lodos y biosólidos.—Especificaciones y límites máximos permisibles de contaminantes para su aprovechamiento y disposición final. DOF: Ciudad de México, México, 2002.

- Commission for Enviromental Cooperation Petición SEM-23-003: Producción de Agave En Jalisco. Respuesta de Los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Comisión Para la Cooperación Ambiental; Commission for Enviromental Cooperation: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023; pp. 1–53.

- Méndez-Matías, A.; Robles, C.; Ruiz-Vega, J.; Castañeda-Hidalgo, E. Compostaje de Residuos Agroindustriales Inoculados Con Hongos Lignocelulósicos y Modificación de La Relación C/N. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2018, 9, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essonanawe-Edjabou, M.; Scheutz, C. Quantification of—And Determining Factors Affecting—Methane Emissions from Composting Plants. Waste Manag. 2023, 170, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Soares, J.K.; Valle-Vitali, V.M.; Afonso-Vallim, M. Lignin Degradation by Co-Cultured Fungi: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Lilloa 2022, 59, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giap, V.D.; Nghi, D.H.; Cuong, L.H.; Quynh, D.T. Lignin Peroxidase from the White-Rot Fungus Lentinus squarrosulus MPN12 and Its Application in the Biodegradation of Synthetic Dyes and Lignin. Bioresources 2022, 17, 4480–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabed, H.M.; Akter, S.; Yun, J.; Zhang, G.; Awad, F.N.; Qi, X.; Sahu, J.N. Recent Advances in Biological Pretreatment of Microalgae and Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuel Production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedayo-Fasiku, S.; Monilola-Wakil, S.; Monilola-Alao, O. Degradation of Lignocellulosic Substrates by Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinus squarrosulus. Asia J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 10, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidipati, S.; Ahmed, A. Degradation of Lignin in Agricultural Residues by Locally Isolated Fungus Neurospora Discreta. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 181, 1561–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-Santacruz, G.A.; Aguado-Rodríguez, D.L.; Moreno-Gómez, B.; Arroyo-González, D.; Centeno-Jamaica, D.; Aguirre-Mancilla, C.; García-Moya, E. Endomicrobiota Bacteriana de Agave Pulquero (Agave salmiana). I. Aislamiento, Frecuencia e Identificación Molecular. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2022, 45, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgas, D.; Rukavina, M.; Bešlo, D.; Štefanac, T.; Crnek, V.; Šikić, T.; Habuda-Stanić, M.; Landeka-Dragičević, T. The Bacterial Degradation of Lignin—A Review. Water 2023, 15, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño-Ruiz, S.D.; Lázaro, A.A.Á.; García, S.C.; Hernández, R.G.; Chen, J.; Navarro, G.K.G.; Fajardo, L.V.G.; Jimenez-Pérez, N.C.; Torres-de-la-Cruz, M.; Cifuentes-Blanco, J.; et al. New Record of Schizophyllum (Schizophyllaceae) from Mexico and the Confirmation of Its Edibility in the Humid Tropics. Phytotaxa 2019, 413, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Kwon, S.L.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.J. Notes of Five Wood-Decaying Fungi from Juwangsan National Park in Korea. Mycobiology 2024, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, R.L.; Ryvarden, L. North American Polypores, Vol. 1: Abortiporus–Lindtneria; Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway, 1986; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Coello-Loor, C.D.; Avellaneda-Cevallos, J.H.; Barrera-Alvarez, A.; Peña-Galeas, M.M.; Yépez-Macías, P.F.; Racines-Macías, E.R. Evaluación Del Crecimiento y Producción de Biomasa de Dos Cepas Del Género Pleurotus Spp. Cultivadas En Un Medio AGAR Con Diferentes Sustratos. Cienc. Tecnol. 2017, 10, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cao, G.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yang, W.; Zheng, B.; Tan, J.; et al. Isolation, Identification and Pollution Prevention of Bacteria and Fungi during the Tissue Culture of Dwarf Hygro (Hygrophila polysperma) Explants. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, O.E.; Akanya, H.O.; Ogbandu, G.H.; Egwim, E.C.; Etim, V.A.; Akande, S.A. Development and Optimization of a Surface Sterilization Protocol for the Tissue Culture of Pleurotus Tuber-Regium (Fr) Sing. and Auricularia Auricula-Judae. Int. J. Biochem. Bioinform. Biotechnol. Stud. 2016, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, G.; Salmones, D. Ciclo de Vida y Tipo de Aislamiento. In Técnicas de Aislamiento, Cultivo y Conservación de Cepas de Hongos en el Laboratorio; Mata, G., Salmones, D., Eds.; Instituto de Ecología, A.C: Xalapa, Mexico, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 23–35. ISBN 9786078833009. [Google Scholar]

- Jaikishun, M.; Da-Silva, P.N.B. Production of White Oyster Mushroom Spawn Using Different Grain-Based Substrates. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 27, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.M.P.Q.; Azevedo, A.C.; Guimarães, A.S. Moisture Content Determination. In Interface Influence on Moisture Transport in Building Components; Delgado, J.M.P.Q., Azevedo, A.C., Guimarães, A.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, H.; Shan, C.; Zhang, J. Moisture Content Online Detection System Based on Multi-Sensor Fusion and Convolutional Neural Network. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1289783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo-González, M.R.; González-Eguiarte, D.R.; Rodríguez-Macías, R.; Ruiz-Corral, J.A.; Durán-Puga, N. Caracterización Química y Física Del Bagazo de Agave Tequilero Compostado Con Biosólidos de Vinaza Como Componente de Sustratos Para Cultivos En Contenedor. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2018, 34, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K.; Singh, N.; Jindal, S.; Kaur, R.; Goyal, A.; Awasthi, R. Kjeldahl Method. In Advanced Techniques of Analytical Chemistry: Volume 1; Goyal, A., Kumar, H., Eds.; Bentham Science Publisher: Singapore, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Quirino, D.F.; Palma, M.N.N.; Franco, M.O.; Detmann, E. Variations in Methods for Quantification of Crude Ash in Animal Feeds. J. AOAC Int. 2022, 106, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabadie, M.; Pérez, C.A.; Arturi, M.F.; Goya, J.F.; Sandoval, M. Calibración Del Método de Pérdida de Peso Por Ignición Para La Estimación Del Carbono Orgánico En Inceptisoles Del NE de Entre Ríos. Rev. Fac. Agron. 2018, 117, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Ravelo, F.; Ugas-Pérez, M.; Calderón-Castellanos, R.; Rivas-Meriño, F. Cuantificación Del Carbono Orgánico y Materia Orgánica En Suelos No Rizosféricos o Cubiertos Por Avicennia germinans (L.) y Conocarpus erectus (L.) Emplazados En Boca de Uchire, Laguna de Unare, Estado de Anzoátegui, Venezuela. Rev. Geogr. Am. Cent. 2021, 1, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Loon, J.C. Analytical Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy: Select Methods; Van-Loon, J.C., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780127140506. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S.S. Total Carbohydrate by Phenol-Sulfuric Acid Method. In Nielsen’s Food Analysis Laboratory Manual; Ismail, B.P., Nielsen, S.S., Eds.; Food Science Text Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Raffrenato, E.; Van-Amburgh, M.E. Technical Note: Improved Methodology for Analyses of Acid Detergent Fiber and Acid Detergent Lignin. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 3613–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiwango, E.; Abdel-Rahman, N.S.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; Abu-Omar, M.M.; Khaleel, A.A. Klason Method: An Effective Method for Isolation of Lignin Fractions from Date Palm Biomass Waste. Chem. Process Eng. Res. 2018, 57, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.S.; Lim, L.-T.; Manickavasagan, A. Imaging and Spectroscopic Techniques for Microstructural and Compositional Analysis of Lignocellulosic Materials: A Review. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Mandal, A.; Nandabalan, Y.K. Synergistic Effect on Lignolytic Enzyme Production through Co-Culturing of White Rot Fungi during Solid State Fermentation of Agricultural Residues. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2025, 49, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tu, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Huang, H.; Yao, B.; Luo, H.; et al. Sequential Pretreatment with Hydroxyl Radical and Manganese Peroxidase for the Efficient Enzymatic Saccharification of Corn Stover. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.; Ngo, T.; Ball, A.S. Valorisation of Sugarcane Bagasse for the Sustainable Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damián-Robles, R.M.; Castro-Montoya, A.J.; Saucedo-Luna, J.; Vázquez-Garcidueñas, M.S.; Arredondo-Santoyo, M.; Vázquez-Marrufo, G. Characterization of Ligninolytic Enzyme Production in White-Rot Wild Fungal Strains Suitable for Kraft Pulp Bleaching. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.S.; Gupta, R.K.; Karuppanan, K.K.; Padhi, D.K.; Ranganathan, S.; Paramanantham, P.; Lee, J.K. Trametes versicolor Laccase-Based Magnetic Inorganic-Protein Hybrid Nanobiocatalyst for Efficient Decolorization of Dyes in the Presence of Inhibitors. Materials 2024, 17, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Luo, H.; Zhang, X.; Yao, B.; Ma, F.; Su, X. Dye-Decolorizing Peroxidases in Irpex lacteus Combining the Catalytic Properties of Heme Peroxidases and Laccase Play Important Roles in Ligninolytic System. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Chelike, D.K. Utilizing Fungal Biodegradation for Valorisation of Lignocellulosic Waste Biomass and Its Diverse Applications. Appl. Res. 2024, 3, e202300119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Su, X.; Luo, H.; Ma, R.; Yao, B.; Ma, F. Deciphering Lignocellulose Deconstruction by the White Rot Fungus Irpex lacteus Based on Genomic and Transcriptomic Analyses. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Yuan, B.; Guo, H.; Tian, H.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Li, C.; Fei, Q. Enhanced Lignin Biodegradation by Consortium of White Rot Fungi: Microbial Synergistic Effects and Product Mapping. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savinova, O.S.; Fedorova, T.V. Peroxidase of Trametes hirsuta LE-BIN 072: Purification, Characteristics, and Application for Dye Decolorization. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2024, 60, 1209–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Herrera, O.E.; Martha-Paz, A.M.; Pérez-LLano, Y.; Aranda, E.; Tacoronte-Morales, J.E.; Pedroso-Cabrera, M.T.; Arévalo-Niño, K.; Folch-Mallol, J.L.; Batista-García, R.A. Schizophyllum commune: An Unexploited Source for Lignocellulose Degrading Enzymes. Microbiologyopen 2018, 7, e00637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduzco-Oliva, R.; Gutierrez-Uribe, J.A. Beyond Enzyme Production: Solid State Fermentation (SSF) as an Alternative Approach to Produce Antioxidant Polysaccharides. Sustainability 2020, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Navarro, C.S.; Warren-Vega, W.M.; Serna-Carrizales, J.C.; Zárate-Guzmán, A.I.; Ocampo-Pérez, R.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Collins-Martínez, V.H.; Niembro-García, J.; Romero-Cano, L.A. Evaluation of the Environmental Performance of Adsorbent Materials Prepared from Agave Bagasse for Water Remediation: Solid Waste Management Proposal of the Tequila Industry. Materials 2022, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.S. Enhancement the Feeding Value of Rice Straw as Animal Fodder through Microbial Inoculants and Physical Treatments. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2018, 7, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Ojeda, C.; Montoya-Rosales, J.J.; Palomo-Briones, R.; Montiel-Corona, V.; Celis, L.B.; Razo-Flores, E. Saccharification of Agave Bagasse with Cellulase 50 XL Is an Effective Alternative to Highly Specialized Lignocellulosic Enzymes for Continuous Hydrogen Production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Li, F.; Jia, L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, S.; Luo, B.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, M.; Xia, Y. Fungal Selectivity and Biodegradation Effects by White and Brown Rot Fungi for Wood Biomass Pretreatment. Polymers 2023, 15, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civzele, A.; Stipniece-Jekimova, A.A.; Mezule, L. Fungal Ligninolytic Enzymes and Their Application in Biomass Lignin Pretreatment. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezule, L.; Civzele, A. Bioprospecting White-Rot Basidiomycete Irpex lacteus for Improved Extraction of Lignocellulose-Degrading Enzymes and Their Further Application. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Plaza, N.; Kojima, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Zhang, J.; Jellison, J.; Pingali, S.V.; O’Neill, H.; Goodell, B. Nanostructural Analysis of Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Brown Rot Fungal Deconstruction of the Lignocellulose Cell Wall. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Zuo, S.; Ren, J.; Huhetaoli; Zheng, M.; Jiang, D.; Xu, C. Novel Strategy to Improve the Colonizing Ability of Irpex lacteus in Non-Sterile Wheat Straw for Enhanced Rumen and Enzymatic Digestibility. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambatkar, N.; Jadhav, D.D.; Deshmukh, A.; Sattikar, P.; Wakade, G.; Nandi, S.; Kumbhar, P.; Kommoju, P.-R. Functional Screening and Adaptation of Fungal Cultures to Industrial Media for Improved Delignification of Rice Straw. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 155, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, H.; Kristensen, J.B.; Felby, C. Enzymatic Conversion of Lignocellulose into Fermentable Sugars: Challenges and Opportunities. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2007, 1, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.